#The Combahee River Collective

Text

"Above all else, Our politics initially sprang from the shared belief that Black women are inherently valuable, that our liberation is a necessity not as an adjunct to somebody else’s may because of our need as human persons for autonomy. This may seem so obvious as to sound simplistic, but it is apparent that no other ostensibly progressive movement has ever consIdered our specific oppression as a priority or worked seriously for the ending of that oppression. Merely naming the pejorative stereotypes attributed to Black women (e.g. mammy, matriarch, Sapphire, whore, bulldagger), let alone cataloguing the cruel, often murderous, treatment we receive, Indicates how little value has been placed upon our lives during four centuries of bondage in the Western hemisphere. We realize that the only people who care enough about us to work consistently for our liberation are us. Our politics evolve from a healthy love for ourselves, our sisters and our community which allows us to continue our struggle and work. "

The Combahee River Collective statement

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time to learn about more people and things that influenced my politics~

The Combahee River Collective.

They were a Black feminist lesbian socialist organization active in Boston, Massachusetts from 1974 to 1980.

"The Collective argued that both the white feminist movement and the Civil Rights Movement were not addressing their particular needs as Black women and more specifically as Black lesbians.

Racism was present in the mainstream feminist movement, while Delaney and Manditch-Prottas argue that much of the Civil Rights Movement had a sexist and homophobic reputation."

The Collective is perhaps best known for developing the Combahee River Collective Statement, a key document in the history of contemporary Black feminism and the development of the concepts of identity politics as used among political organizers and social theorists, and for introducing the concept of interlocking systems of oppression, including but not limited to gender, race, and homophobia, a fundamental concept of intersectionality. Gerald Izenberg credits the 1977 Combahee statement with the first usage of the phrase "identity politics".

Source

Demita Frazier, Beverly Smith, and Barbara Smith were the primary authors of the Combahee River Collective Statement in 1977. [...]They sought to destroy what they felt were the related evils of capitalism, imperialism, and patriarchy while rejecting the belief in lesbian separatism. Finally their statement acknowledged the difficulties black women faced in their grassroots organizing efforts due to their multiple oppressions.

In “A Black Feminist’s Search for Sisterhood,” Michele Wallace arrives at this conclusion:

We exists as women who are Black who are feminists, each stranded for the moment, working independently because there is not yet an environment in this society remotely congenial to our struggle—because, being on the bottom, we would have to do what no one else has done: we would have to fight the world. [2]

Wallace is pessimistic but realistic in her assessment of Black feminists’ position, particularly in her allusion to the nearly classic isolation most of us face. We might use our position at the bottom, however, to make a clear leap into revolutionary action. If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.

#i think of that line at least twice a month#and this is why you will NEVER catch me not having solidarity with black women#combahee river collective#black feminism#black feminists#demita Frasier#Beverly smith#Barbara smith#black lesbians#queer history#lgbt History#black history#queer rights#lesbian rights#solidarity#identity politics#lgbt#capitalism#i should start recommending this as a starter too tbfh#queer#lesbian history#black women#black revolutionaries#lesbian revolutionaries#intersectionality#feminism#lesbian#patriarchy#white feminism#feminists

211 notes

·

View notes

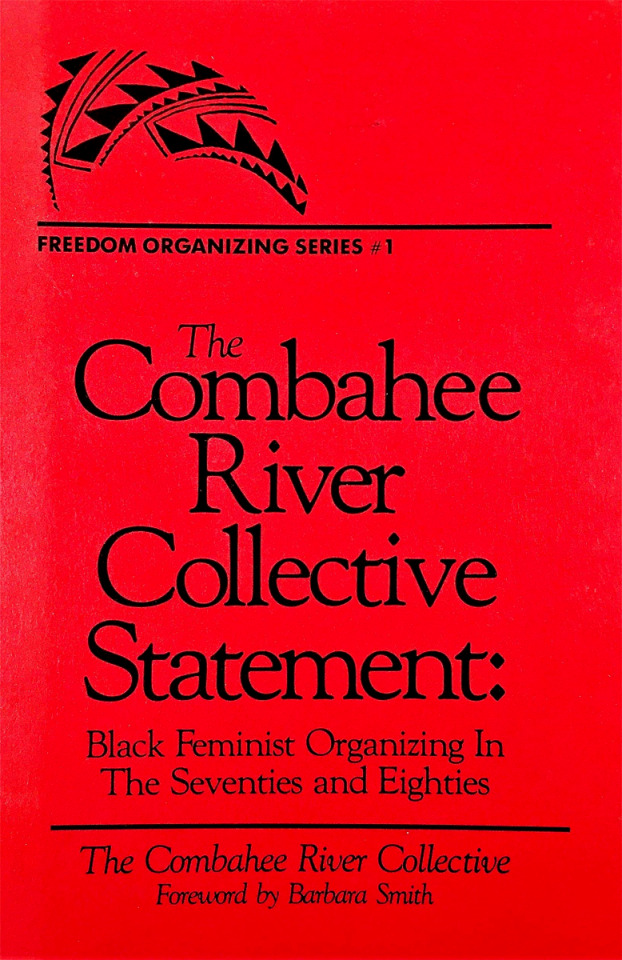

Photo

The Combahee River Collective Statement: Black Feminist Organizing In The Seventies and Eighties, Foreword by Barbara Smith, «Freedom Organizing» 1, Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, Latham, NY, 1986

#graphic design#pamphlet#manifesto#cover#combahee river collective#barbara smith#beverly smith#audre lorde#demita frazier#cheryl clarke#margo okazawa rey#gloria akasha hull#kitchen table women of color press#1980s

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We cannot live without our lives" || Combahee River Collective members march in a memorial to 11 women of color murdered in the Boston area (1979). Photograph by Tia Cross via Verso

#International Women's Day#Combahee River Collective#Black feminism#misogyny#misogynoir#violence against black women

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wow… what an amazingly revolutionary ideology that is totally challenging and deconstructing the patriarchy (/sarcasm) by *checks notes* blaming victims of patriarchal violence…

I’m sure you have other totally normal, totally non-racist, totally non-homophobic things to—

Hmm. Wow. Yeah. Fascinating how “hate all men” leads people to specifically single out marginalized men and discourage people from forming class consciousness on issues of race and queerness. Would have never expected that (/sarcasm). I’m sure this is super duper helpful for combating white supremacy 👍

#Clowns#it’s one thing to be like: ‘men are part of an oppressor class’#and another to suggest the only class dynamic is the M > F class dynamic#yes. all men perpetuate misogyny#and all men benefit in some way and in varying different degrees from the patriarchy#their marginalization affects how they benefit from the patriarchy and the limits of the patriarchy’s benefits#but you don’t need to blame victims of patriarchal violence for the violence committed against them as a gotcha#the violence committed against men at the hands of men is a feature of the patriarchy#it isn’t a fluke#and NO ONE deserves to be brutalized because of their membership to a class#also really weird that they constantly single out marginalized men specifically#and try to discourage political alliances#and thus discourage the creation of other class movements that include women and their struggle#women’s struggles as poor women. queer women. black women. disabled women etc…#they learned nothing from THE COMBAHEE RIVER COLLECTIVE

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

the original content of this post is important, but the addition tells me that a lot of you still use the phrase "identity politics" as a boogeyman and have no idea what it means. i understand that a lot of people online use the phrase, so you might THINK that you know what it means. but i guarantee none of you have read any works by the combahee river collective, the black feminist organization that coined the term.

to quote directly,

"What We Believe

Above all else, Our politics initially sprang from the shared belief that

Black women are inherently valuable, that our liberation is a necessity not as an adjunct to somebody else's may because of our need as human persons for autonomy. This may seem so obvious as to sound simplistic, but it is apparent that no other ostensibly progressive movement has ever consIdered our specific oppression as a priority or worked seriously for the ending of that oppression. Merely naming the pejorative stereotypes attributed to Black women (e.g. mammy, matriarch, Sapphire, whore, bulldagger), let alone cataloguing the cruel, often murderous, treatment we receive, Indicates how little value has been placed upon our lives during four centuries of bondage in the Western hemisphere. We realize that the only people who care enough about us to work consistently for our liberation are us. Our politics evolve from a healthy love for ourselves, our sisters and our community which allows us to continue our struggle and work.

This focusing upon our own oppression is embodied in the concept of identity politics. We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else's oppression. In the case of Black women this is a particularly repugnant, dangerous, threatening, and therefore revolutionary concept because it is obvious from looking at all the political movements that have preceded us that anyone is more worthy of liberation than ourselves. We reject pedestals, queenhood, and walking ten paces behind. To be recognized as human, levelly human, is enough."

i encourage you to read the whole statement here. please keep the phrase "identity politics" out of your mouth until you understand that the criticism of "IDPOL" is the leftist equivalent of conservatives criticising critical race theory.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Combahee River Collective Statement

...

Above all else, our politics initially sprang from the shared belief that Black women are inherently valuable, that our liberation is a necessity not as an adjunct to somebody else's may because of our need as human persons for autonomy. This may seem so obvious as to sound simplistic, but it is apparent that no other ostensibly progressive movement has ever consIdered our specific oppression as a priority or worked seriously for the ending of that oppression. Merely naming the pejorative stereotypes attributed to Black women (e.g. mammy, matriarch, Sapphire, whore, bulldagger), let alone cataloguing the cruel, often murderous, treatment we receive, Indicates how little value has been placed upon our lives during four centuries of bondage in the Western hemisphere. We realize that the only people who care enough about us to work consistently for our liberation are us. Our politics evolve from a healthy love for ourselves, our sisters and our community which allows us to continue our struggle and work.

This focusing upon our own oppression is embodied in the concept of identity politics. We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else's oppression. In the case of Black women this is a particularly repugnant, dangerous, threatening, and therefore revolutionary concept because it is obvious from looking at all the political movements that have preceded us that anyone is more worthy of liberation than ourselves. We reject pedestals, queenhood, and walking ten paces behind. To be recognized as human, levelly human, is enough.

We believe that sexual politics under patriarchy is as pervasive in Black women's lives as are the politics of class and race. We also often find it difficult to separate race from class from sex oppression because in our lives they are most often experienced simultaneously. We know that there is such a thing as racial-sexual oppression which is neither solely racial nor solely sexual, e.g., the history of rape of Black women by white men as a weapon of political repression.

Although we are feminists and Lesbians, we feel solidarity with progressive Black men and do not advocate the fractionalization that white women who are separatists demand. Our situation as Black people necessitates that we have solidarity around the fact of race, which white women of course do not need to have with white men, unless it is their negative solidarity as racial oppressors. We struggle together with Black men against racism, while we also struggle with Black men about sexism.

We realize that the liberation of all oppressed peoples necessitates the destruction of the political-economic systems of capitalism and imperialism as well as patriarchy. We are socialists because we believe that work must be organized for the collective benefit of those who do the work and create the products, and not for the profit of the bosses. Material resources must be equally distributed among those who create these resources. We are not convinced, however, that a socialist revolution that is not also a feminist and anti-racist revolution will guarantee our liberation. We have arrived at the necessity for developing an understanding of class relationships that takes into account the specific class position of Black women who are generally marginal in the labor force, while at this particular time some of us are temporarily viewed as doubly desirable tokens at white-collar and professional levels. We need to articulate the real class situation of persons who are not merely raceless, sexless workers, but for whom racial and sexual oppression are significant determinants in their working/economic lives. Although we are in essential agreement with Marx's theory as it applied to the very specific economic relationships he analyzed, we know that his analysis must be extended further in order for us to understand our specific economic situation as Black women.

A political contribution which we feel we have already made is the expansion of the feminist principle that the personal is political. In our consciousness-raising sessions, for example, we have in many ways gone beyond white women's revelations because we are dealing with the implications of race and class as well as sex. Even our Black women's style of talking/testifying in Black language about what we have experienced has a resonance that is both cultural and political. We have spent a great deal of energy delving into the cultural and experiential nature of our oppression out of necessity because none of these matters has ever been looked at before. No one before has ever examined the multilayered texture of Black women's lives. An example of this kind of revelation/conceptualization occurred at a meeting as we discussed the ways in which our early intellectual interests had been attacked by our peers, particularly Black males. We discovered that all of us, because we were "smart" had also been considered "ugly," i.e., "smart-ugly." "Smart-ugly" crystallized the way in which most of us had been forced to develop our intellects at great cost to our "social" lives. The sanctions In the Black and white communities against Black women thinkers is comparatively much higher than for white women, particularly ones from the educated middle and upper classes.

As we have already stated, we reject the stance of Lesbian separatism because it is not a viable political analysis or strategy for us. It leaves out far too much and far too many people, particularly Black men, women, and children. We have a great deal of criticism and loathing for what men have been socialized to be in this society: what they support, how they act, and how they oppress. But we do not have the misguided notion that it is their maleness, per se—i.e., their biological maleness—that makes them what they are. As BIack women we find any type of biological determinism a particularly dangerous and reactionary basis upon which to build a politic. We must also question whether Lesbian separatism is an adequate and progressive political analysis and strategy, even for those who practice it, since it so completely denies any but the sexual sources of women's oppression, negating the facts of class and race.

...

One issue that is of major concern to us and that we have begun to publicly address is racism in the white women's movement. As Black feminists we are made constantly and painfully aware of how little effort white women have made to understand and combat their racism, which requires among other things that they have a more than superficial comprehension of race, color, and Black history and culture. Eliminating racism in the white women's movement is by definition work for white women to do, but we will continue to speak to and demand accountability on this issue.

In the practice of our politics we do not believe that the end always justifies the means. Many reactionary and destructive acts have been done in the name of achieving "correct" political goals. As feminists we do not want to mess over people in the name of politics. We believe in collective process and a nonhierarchical distribution of power within our own group and in our vision of a revolutionary society. We are committed to a continual examination of our politics as they develop through criticism and self-criticism as an essential aspect of our practice. In her introduction to Sisterhood is Powerful Robin Morgan writes:

I haven't the faintest notion what possible revolutionary role white heterosexual men could fulfill, since they are the very embodiment of reactionary-vested-interest-power.

As Black feminists and Lesbians we know that we have a very definite revolutionary task to perform and we are ready for the lifetime of work and struggle before us.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

i hate doing the readings for this class they make me so upset

#emyrs.txt#‘above all else our politics initially sprang from the shared belief that Black women are inherently valuable—that our liberation is a#necessity not as an adjunct to somebody else’s but because of our need as human persons for autonomy.’#LIKE!#THIS WAS THE 70S‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️#also the fact that the combahee river collective + NBFO had to be formed explicity bc of the racism of the feminist movement AND the sexism#of the civil rights movement is so deeply upsetting it turns right back around to being funny. like. yeah. ofc what else did we expect.#i also read a paper earlier this week about how feminists weren’t really fighting for equality in the way we think of it. like. some were#obviously. but the mainstream movement wanted. like. to have access to ‘masculine’ things (like management jobs and sports and being allowed#to wear pants) but they wanted to do those things and not be labeled masculine.#here let me pull up the quote: the argument was not that women had the right to masculinity—but rather that such activities were not#intrinsically masculine—and i. any case women could do them and still be feminine#so i think the same thing applies to. why the CRC and NBFO had to formed.#ANYWAYS.#whenever i use an em dash. it’s bc i can’t use commas. btw.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

While many people (such as myself) had not heard of such as things as intersectional identities until introduced to Kimberle Crenshaw, the Combahee River Collective, a group of radical Black feminists considered this notion much decades prior and touched on the unique experience and existence of Black women and expanded outside of exising Feminist and Black nationalists movements. This group consisted of Barbara Smith, Beverly Smith, Demita Frazier, Cheryl Clarke, Akasha Hull, Margo Okazawa-Rey, Chirlane McCray, and Audre Lorde.

#black feminism#black feminist thought#black liberation#combahee river collective#keeanga-yamahtta taylor#intersectionality#black girl magic#Youtube

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"This focusing upon our own oppression is embodied in the concept of identity politics. We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression. In the case of Black women this is a particularly repugnant, dangerous, threatening, and therefore revolutionary concept because it is obvious from looking at all the political movements that have preceded us that anyone is more worthy of liberation than ourselves. We reject pedestals, queenhood, and walking ten paces behind. To be recognized as human, levelly human, is enough."

The Combahee River Collective statement

1 note

·

View note

Text

“kinda wild when you think about it that members of the combahee river collective are still alive and have repeatedly clarified the actual meaning of identity politics (including here on twitter) and people still just openly misuse it lol”

“And write wholeass books and thinkpieces on the shyt and suggest it’s some new age neoliberal concept.”

4 notes

·

View notes

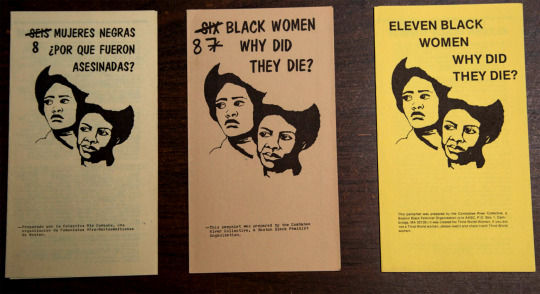

Photo

Pamphlets by the Combahee River Collective as a campaign to bring awareness to the murders of Black women in Boston, MA, around 1979 [Black Women Radicals]

#graphic design#pamphlet#cover#combahee river collective#barbara smith#beverly smith#audre lorde#demita frazier#cheryl clarke#margo okazawa rey#gloria akasha hull#black women radicals#1970s#1980s

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Never really occurred to me to think that the Combahee River Collective has a group chat but honestly Barbara Smith IS on twitter so I’m sure there is one and I too think Jazmine should pay money to see any and all screenshots

#you guys ever see the pictures from their retreats in Western MA in the 70s#the energy is insane#once in the lesbian herstory archives I found some letters from Audre Lorde to Barbara Smith complaining about the ice cream selection#anyway what I’m saying is the ones who are still living for sure have thoughts on the deblasio situation#pls leak for the good of the rest of us#combahee River collective

1 note

·

View note

Text

Interview with Stephanie Byrd: by Terri Jewell

(Originally published in Does Your Mama Know? An Anthology of Black Lesbian Coming Out Stories, ed. Lisa C. Moore, published by RedBone press 1997. Transcribed by @laciere (typos my own).)

[Stephanie Byrd is a Black lesbian feminist poet, writer, critic, community activist. Her works include two books of poetry; critical essays in Greenwood Press’ Bibliography of Contemporary Lesbian Literature (1993) and Lesbian Review of Books (1995); listing in Black Lesbians: An annotated Bibliography by J. R. Roberts (1981); mentioned in Ann Allen Shockley’s essay, “The Black Lesbian in American Literature: An Overview” (1979) and Black Women and the Sexual Mountain by Calvin Hernton (1988). Her poetry has appeared in The American Voice, Kenyon Review, Conditions and Sinister Wisdom. Her books have been reviewed by many publications.]

STEPHANIE BYRD: I was born in 1950 on July 10th in Richmond, Indiana. My family has lived in or around Richmond since the War of 1812, perhaps before then. Part of them came from Boston, Massachusetts, because the Northwest Territory was free territory and they did not wish to become enslaved again. Other members of my family escaped from slavery in the South and came to Indiana, where small Black settlements had sprung up. These are the people that I came from.

I was a Latin major at Ball State University from 1968-69 and was an anti-war activist from 1968-73. I met some civil rights activists during that period who were doing work in Cairo, Illinois. The Black community in Cairo was boycotting the white businesses because of their refusal to hire Blacks. The white community was responding by driving through the Black community at night and shooting through people’s windows, so after dark people would turn out the lights and sit on the floor. I met a man who was doing some fund-raising at Indiana University in Bloomington and became involved with gathering canned goods and clothing to offset “The Wolf” in Cairo until the problem could be resolved.

TERRI JEWELL: Were you a lesbian then?

BYRD: Yes. When I was about 6 or 7, one of the neighbors called me a lesbian. I went to my grandmother and asked her about it and she told me that being a lesbian was about loving women, women loving women.

JEWELL: Your grandmother told you that?!!

Byrd: Yes. My grandmother Byrd. And that it was all right to be a lesbian if I really loved someone. And since I was in love with my little next door neighbor, I went out and told everyone that we were lesbians. My mother was furious and I think that was the first time I heard about lesbians. The second time, I was 12 and I was asked to put down on a sheet of paper what my goals in life were. I was in seventh grade at Hibbard Elementary/Junior High School. I had put down that my goals were to be a brain surgeon, a lawyer, and a lesbian. I was sent to the office. I realized when I was sent down to the office that something was terribly wrong even though I was only 12, and they said, “Well, do you know what a lesbian?” And I said, “It’s a person who lives on the isle of lesbos,” because I had looked it up in the dictionary. They me go, feeling secure that i really didn’t know what I was talking about. It’s funny that about a year later I was sent to the office again for being a Communist.

JEWELL: A Communist?

BYRD: Yes, because I asked for the Communist Manifesto at the school library so we could compare it to the Declaration of Independence.

When I was about 17, I realized that there was something wrong with being a lesbian socially.I tried to become straight and hooked up with this guy who turned out to be gay. By the time I was 19, I realized that none of this was working, so I just went back to being a lesbian again. It was very hard, though, because at 19 you’re kind of a sexual libertine. You’re not straight, you’re not gay. You’re just in heat. Being a lesbian was just the best and easiest way for me to be.

JEWELL: When did you start writing?

BYRD: When I was 17, in the summer. I had actually started writing before then during that school year and had written some short stories and some poetry. When I graduated from high school, I started writing poetry seriously and actually had a contest with my little gay boyfriend. We would write a book of poetry a month and that summer I produced three books of poetry, all of which I burned.

JEWELL: Why?

BYRD: I have destroyed my work in the past. I’d say, all together, four books of poetry. I have a tendency to lose control of my temper and as a result, my reason. I would burn my work as a cleansing act. A ritual.

JEWELL: You don’t consider the act of writing a cleansing? A ritual?

BYRD: Writing can be cleansing, but there have been times in my life when even the writing is not enough to cleanse.

JEWELL: So, writing is not always enough to cleanse what?

BYRD: Oh, I call them “the Terrors.” They are anxieties and fears that somehow combine into a feeling so large they seem to consume me from the inside out. I think some actress in a Neil Simon play once called the “Read Meanies.”

JEWELL: What has survived of your writing?

BYRD: There is a book of poetry called 25 Years of Malcontent which is now out of print. When I finished 25 Years of Malcontent, it was the result of serious years of serious writing, the last three of which I wrote every day for at least two hours a day, sometimes eight, depending on whether or not I was employed. I t was released in 1976 and published by Good Gay Poets in Boston. As with most first works by a writer, it’s somewhat autobiographical, describing things and events that I observed or was involved in. There is one poem there about a man who died in a house. He wasn’t found until much later and his cats had tried to chew through the door to get to him to eat him because they hadn’t been fed. And there is a poem about a white suffragette I had met in Texas. She was a wonderful, wonderful woman well into her 60s. This was in 1972. She told me to be true to my roots. The advice that she gave me was very good advice. The whole time I was in Boston, I don’t think I ever really convinced myself that I was anything but a Black woman from Indiana.

JEWELL: When did you first go to Boston?

BYRD: It was 1973.

JEWELL: Were you aware of the Combahee River Collective?

BYRD: In 1974, the women who eventually evolved into the Combahee River Collective were the National Black Feminist Organization of which I was a member. We used to meet as a support group at the Women’s Center in Cambridge. We would talk about a number of things. Barbara Smith was there and she developed guidelines on how we were to support each other. It was very like consciousness-raising. I remember the group being an open group and a lot of women coming who were straight and battered. They were Black women. Some of them were successful, some of them were very poor, some of them were working-class women. There were incidents where outsiders would come and discover that there were Black lesbians there and they would flip out with a great deal of hysteria and arguing and name-calling. And those were the early meetings. But the thing i remember is these women coming who had been so battered in their lives that there was something disturbing about them and a support group wasn’t going to do it for them. I heard someone say recently that one of the best cures for mental illness for Black people is Black culture and I wanted the group to be more committed to the creation and preservation of Black women’s culture. But that was really difficult to do with the Combahee River Collective because the group soon was not all Black. And the support group was very committed to combating racism and sexism and antisemitism and class oppression, so many minority women had to be included. At that time, I had a great deal of difficulty synthesizing the presence and the issues of the minority women who were not Black into the issues that involved me. I was something of a Black separatist, I suppose.

JEWELL: In reading their statement, the group was against separatism and wanted to work with Black men.

BYRD: Well, I never heard them say anything about working with any men when I was in the group. They talked about working with white women. [In attempting to address] all the other concerns [of Koreans, Hispanics, Jews, Chinese, Vietnamese, etc.] just turned into a wave that seemed to obliterate what I was hoping would become a Black feminist support group. And as Black feminists, in retrospect, I realize now that I was hoping that we could do something to address the needs of some of these women who were coming to us who had been stabbed or shot or beaten and threatened and didn’t know how to leave their husbands or didn’t know how to address life without a man. These women needed a separatist environment in which to heal. Maybe later on, this whole multi-ethnic feminist vanguard could include them, but for then and for now, too, it doesn’t. It does not address the needs of these Black women.

JEWELL: I agree. So, why do you think that is, even though we are well-versed in the problems that we have? And I’m not living on either the East or the West coasts, but in the Midwest. You know the gaps HERE. In your opinion, why are we Black women so afraid of having our own groups and projects exclusively? We always talk about how nice it is to be among ourselves with our own language and our own ways of doing and seeing things but we just don’t do it. Even the Combahee River Statement says, “We realize that the only people who care enough about us to work consistently for our liberation are us.” Yet, we are constantly getting away from that.

BYRD: Oh, it’s much easier to address everyone else’s needs rather than your own. You know that from dealing with your own problems. It is much easier to go out and find someone else who has a bigger problem or a different problem and work on their problem for them than to deal with your own mess. And essentially, that’s what we have been doing all along historically. We think we CAN’T do it by ourselves. And the reason why we can’t do it by ourselves is because “they” will annihilate us. We have to get away from this paranoia.

JEWELL: How long were you with this group?

BYRD: Oh, until about 1976.

JEWELL: So, it did not start out being a Black lesbian group?

BYRD: Oh, no, no, no.

JEWELL: Or did it start out being a Black lesbian group but no one was saying this so just more women would want to be involved without stigma?

BYRD: When the group started, there were only three of us, including myself, who said they were lesbians. Only three of us announced that we were lesbians during the first night of the group. The other women introduced themselves by talking about where they went to graduate school and what their interests were, etc., but no one else said they were lesbians. After several months, though, some of the other women came out.

JEWELL: What made you leave the group?

BYRD: I Was heavily into my poetry, doing a lot of writing and readings. And I wanted to do more cultural things. I read all over Boston: University of Massachusetts, Boston; Faneuil Hall, which is the Town Hall in Boston. In 1976 I decided I couldn’t maintain the separatist pose any longer, that I would have to become involved in the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement.

JEWELL: Why couldn’t you maintain a separatist stance?

BYRD: Actually, I found that despite what the Combahee River Collective said about separatism, they were very anti-male. Most of the women I knew there did not like men and made no pretense of acting like they liked me or wanted to do anything to help men. I had met a lot of Black gay men who had been decent to me and had been brotherly. I felt the least I could do was return in kind. So I became more involved in the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement but always, ALWAYS my focus was on US as Black people. Not just as Black women but as Black people. And in writing my poetry, because I am a Black woman, I was creating Black women’s culture. And those things were becoming clearer and clearer to me as i grew older. And I didn’t need a large support group to give me an identity. My identity was growing out of MY growing as a Black woman artist and creating Black women’s art. And as a Black person who has a Black father and Black male cousins and Black uncles and a Black grandfather, I had a duty to protect their rights as Black people. The only way I could do that, because I couldn’t do it within the homophobic Black community, was to do it with the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement.

JEWELL: You were on television and the radio?

BYRD: In 1977, I was a guest on a Black cultural TV program called Mzizi Roots. This was an Emmy award-winning program in Boston. I appeared on the segment called “Gay Rights–Whose Rights?” and the host was Sarah Ann shaw. The other two guests were a Black psychologist and a Black gay male activist.We discussed the presence of Black lesbians and gays in the Black community and the legitimacy of claims made by gay and lesbian activist groups for human rights. I also did radio programs. I did one called Coming Out and that was in 1974. I was asked a whole bunch of questions about Black lesbianism. This was on PBS. Then I did another radio program, Out of the Closet, in 1978. By then, I was reading poetry on the air. I had a small group starting with two women and ending up as a five-piece band, called Hermanas. They used to accompany my poetry with music. They were with me until 1982. Then, in 1984 I did a whole one-hour show on MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] radio called Musically Speaking, which was nothing but poetry and music. I also read for Rock Against Sexism, which was the name of a group of punk rockers in 1984. That was at the Massachusetts College of Art. I read in New York for the Open Line Poetry Series at Washington Square Church in 1983; in Newburyport, MA; all over Cambridge. I was very, very active.

JEWELL: Tell me about your second book.

BYRD: My second book is self-published, A Distant Footstep On The PLain. It was the late 1970s. I had been asked to read some poetry at International Women’s Day at Cambridge’s YWCA. I read a poem called “On Black Women Dying.” It deals with Black women I have known who have died and the Black women who were murdered in Boston whose murders were never solved. It was a kind of a serial killing. I read this poem with the accompaniment of music. That’s where Hermanas made their first appearance. It was a conga and a guitar. After that, I got telephone calls to do it again, so we got together and we performed more.

…in the fall of 1978

the Klan began

its “open recruitment”

in Boston City schools

and it was 1955

that a team of white professionals

interviewed colored children

from the Wayne County school system

as to whether their mammas and daddies

was for integration

or segregation

well, what i’m trying to get at

is that in the last 30 odd years

of my life span

there has occurred

a series of events

which have culminated

in the death and near dying

of Black women

across the continent of Amerika…

In 1979 I became unemployed, so I had more time to write. I was moving furniture and doing odd jobs around the city. It was a tough period in my life. I was hungry a lot.

JEWELL: So, how did you self-publish your second book, A Distant Foostep On The Plain?

BYRD: I was working on the Boston and Maine Railroad at the time I finished my second book and i couldn’t find a publisher for it. I self-published my book in 1983. I went to the printers and did a cost comparison. I had a friend who was a typographer and she worked on my manuscript. She gave me the negative for my book so I could get it published. She did this work for free. We took it to a local, small neighborhood newspaper that donated their space and we laid out the book in 24 hours. And then we drove it to the printer’s, it went to press, and a week later I went back and picked up three creates of it. It cost me $600 for 600 copies.

JEWELL: Why the title A Distant Footstep On The Plain?

BYRD: I am from Indiana. In a sense, it is my being true to my roots. It is a reaffirmation of who I am and where I’m from. A distant footstep on the plain. That’s what i was at one time.

I have a manuscript in the works now. It’s tentatively entitled In The house of Coppers. I feel good about this work. It feels better than the second book. It’s a different kind of work, probably closer to the first work. Maybe it’s a new threshold for me.

JEWELL: Which writers do you enjoy?

BYRD: Bessie Head, a South African, and hers Serowe: Village of the Rainwind and Collector of Treasures. I’m very fond of Samuel Delaney, the Black science fiction writer, and Octavia Butler, another Black science fiction writer. I dream of Toni Morrison and I like Gloria Naylor a lot. They are superior writers. There are a lot of African writers that I like: Ferdinand Oyono, who wrote The Old Man And The Medal; Yambo Ologuem, who wrote Bound To Violence; Mariama Ba, who was a very fine writer. I also enjoy Simone Schwarz-Bart, a Caribbean writer who wrote The Bridge of Beyond and the poetry of Marilyn Hacker and William Carlos William and Nicolas Guillén. I also have to give a nod to Sexton and Plath, though their work doesn’t interest me as much as it did when I was in my 20s.

0 notes