#Tikanga

Text

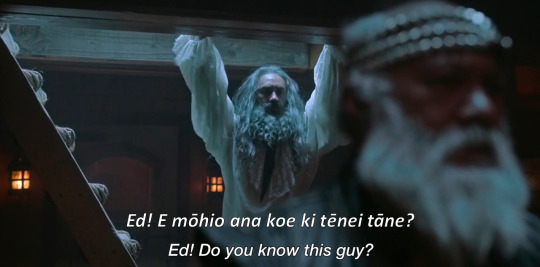

"Pōkokohua" (literally 'boiled head') is the worst thing you can call someone in te reo Māori.

To understand why, you need to understand a bit about Māori culture, specifically the concept of tapu. Tapu usually gets translated as 'sacred' but it's a bit more complicated than that. Tapu things are in the realm of the gods, and traditionally if you violated tapu then you would be at risk of illness or death, depending on the strength of the tapu. Humans inherently have some degree of tapu, with some people being more tapu than others - for example chiefs and priests are more tapu than ordinary people, as are women during childbirth. A person's head is more tapu than the rest of their body, and there is a lot of tapu around the dead, especially human remains. To violate a person's tapu is deeply insulting and dehumanising.

The opposite of tapu is noa. Cooked food is noa, and can be used to remove or reduce tapu and enable people to move from the realm of the gods back into the everyday world. For example one of the important elements of tangi (traditional Māori funerals) is a meal which allows the mourners to remove the tapu associated with the dead and go back into the world of the living.

So by suggesting that someone's head should be boiled, you're saying the most sacred part of their body should be treated like cooked food. The implication is that the person is not worthy of any kind of respect.

Like many swear words, pōkokohua has lost a lot of force over time, but it's still considered a really serious insult.

#te reo maori#tikanga#māoritanga#māori culture#translation#swearing#ofmd#our flag means death#i'm not an expert in this btw

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Phoenix" my ass, get this the fuck outta here

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

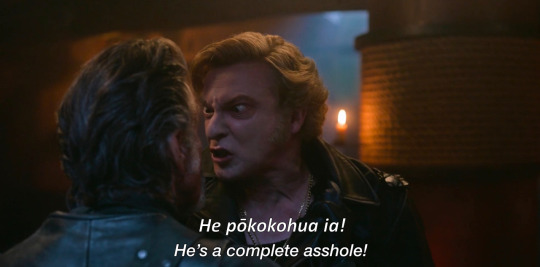

Introducing Te'Ariki O'Donnel, one of the side characters from my newest fic 'It Almost Worked.' I'll be uploading the first chapter later or tomorrow, but I just finished drawing this and I wanted people to see it.

Te'Ariki is Māori, so I included some aspects of this beautiful culture into her design and in the book altogether.

#fruity#Māori#Tikanga#Kia Ora#Avatar#ATWOW#Avatar (2009)#Ariki O'Donnel#OC#Original Character#gay asf#drawing#art#tattoos#huia feathers#military#marines#moko kauae#waiata#New Zealand#Aotearoa

1 note

·

View note

Text

The simping comment 😭 no no no c’mon now

#made me both laugh and cringe#what a thing to say 😂 smh#literally shaking my head#personal#the maori mafia comments too like yess#so important#I’m not even ngāti whātua but I’m glad they stood their ground instead of accepting their koha#no hate to tainui either it’s just a healthy practice tbh#communicating through our culture and our tikanga is better suited for us

0 notes

Text

MAOR202 Essay on Tikaka/Tikanga Māori practice within a chosen workplace.

MAOR202 Māori and Tikanga

Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua:

I walk backwards into the future, my eyes fixed firmly on my past (Rameka, 2016)

Walking Forwards, Eyes Down: Tikaka Māori in practice within Early Childhood.

Early Childhood Education (ECE) within Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) is, on paper, rooted in te ao Māori (the Māori world.), their curriculum (Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga-Ministry of Education., 2017) a bi-cultural document co-created with Kōhanga Reo (Te reo Māori language nest based education system) and governed by the Education Council’s Our Code Our Standards (OCOS) (2017) with lauded Three Treaty Principals enshrined with obligations to uphold them. Prospective kaiako (teachers) are trained in basic tikaka procedures and guidelines (University of Otago, 2022). centres work with whānau, communities and sometimes even Marae or local Iwi consultants to craft tikaka policies reflective of the sector’s location based and Te Tiriti approaches. If tikaka flourishes in any Pākehā system within NZ, it should be within ECE.

Through the example case of REDACTED this essay looks at the current state of tikaka Māori implementation through their policy documents and reflections on my personal experiences through practicum. As well as how implement should be implemented as guided by national standards and academic papers on the subject and identifying the benefits to Māori learners and all centre community members from current and desired implementations of tikaka Māori.

Tikaka Māori can be defined as practices, customs and ways of being and doing that derive from Māori pūrākau (narratives), tipuna (ancestors), traditions, cultural grounding or the Atua.

To counter the damage done to Māori learners and the perception of Māori knowledge and practices by decades of assimilationist colonial policies in education and society (Walker, 2016), Te Whāriki (Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga-Ministry of Education., 2017) was co-designed as a bi-cultural curriculum with Kōhanga Reo and Māori academics and kaiako (Gunn & Nuttall, 2019). As such Te Whāriki (2017) enshrines te ao Māori concepts, theories, and practices as foundational underpinnings to ECE within NZ, stating that all children in NZ must have access and exposure to te reo Māori and tikaka Māori (D’Cunha, 2017) as well as emphasising the Māoritaka holistic ontology that values the mana of children as well as their holistic wellbeing, including spiritual wellbeing. These are understood via the strands of Te Whariki (2017) and increasingly through a simplified and depoliticised model of Mason Durie’s Te Whare Tapa Whā (Higgins & Goodall, 2021). Focus is placed on the importance of affirming Māori as Māori in curriculum documents and OCOS (Education Council | Matatū Aotearoa, 2017) as a means of overcoming the shame created around Māoridom by the assimilationist policies (Milne, 2017) and perceptions of Māori actions and beliefs as lower status (Metge, 1986) that perpetuate self-assimilation (Cormack & Orwin, 1997). Incorporation of tikaka Māori is valued in this context for its utility in affirming Māori learners in their Māori identities, conforming to curriculum and OCOS (2017) standards and uphold Te Tiriti obligations (D’Cunha, 2017) rather than valued as important in itself or as correct or natural practices, a tool to correct the symptoms of colonialism more than a right way of being or doing.

Tikaka practice in activities and routines within ECE is exceptional. While not explicitly present in policy documents, tikaka groundings are present throughout, -REDACTED- which contains many te ao Māori concepts and includes Tikanga Māori: living by Māori values (Mead, 2003) among it’s sources, promoting a deeper understanding of tikaka Māori and it’s purposes.

-REDACTED -once had a tikaka policy but has moved away from this approach to instead have all policies written to cover tikaka rules. For example, having food storage cover the appropriate tikaka as a separate tikaka policy to see they are followed, seeing an integrated policy that doesn’t make staff away of the tikaka in the policy more effective at communicating expectations (Hurst, 2022). This seems consistent with current trends based on experience in another centre with has taken the same tact.

From my placements within two -REDACTED- centres, tikaka Māori actions and procedures are present within the life of the centre. Tables, floors, kitchens, faces, hands and art messes are wiped with separate cloths, karakia sung before kai times and food is prepared on spaces restricted to that purpose. Newly introduced to the centre was the practice of respecting hats and headwear as role modelling to the children and respect of the heads of children respected through no longer putting hats on them directly but giving them hats to put on themselves, with some degree of success. The garden areas were in the process of being realigned to make tikaka practices easier within them however limitations both environmental and social restricted the kaiako leading these changes in implementation. For instance, leaves fallen off the trees or used over natural resources from activities and food waste are thrown out because of REDACTED’s largely artificial environment and lack of space to return leaves to their trees. In the interest of secularism and neutrality any tikaka that would ‘require explaining to the children’ is barred on the principal that is crosses the line into religion/spiritualism and the centre must remain neutral. However, through activities based in cultural narrative stories and resources kaiako have found ways of integrating practices around tapu/noa balance into the centre. For example building on a picture book about a takihaka (funeral) to justify incorporating karakia in the burial of the wētā or incorporating respective karakia practices towards to harvesting of harakeke through the telling of a Māui pūrākau. These incorporations connect tikaka Māori through to their cultural reasons and origins and can be categorised as excellent practice within ECE though are the exceptions, a consequence of a driven kaiako and had to be justified to the more established ‘old-school’ kaiako.

This level of tikaka appears the norm throughout ECE in NZ, D’Cunha (2017) outlines raising awareness of tikaka Māori through a poi activity in their article, again a passionate kaiako incorporating tikaka through a te ao Māori based activity.

The vast majority of tikaka exists outside of specific activities created specifically to teach it, as should be the case, however in these instances unlike the specific activities, they come not from understanding of tikaka Māori but legislation or policy. The Policies REDACTED provide for tikaka practices with explained with utility to resolving conflicts or health and safety, rooting in regulations and standards not in pūrākau or understanding of tikaka Māori.

The most often given example of tikaka practiced in centres throughout initial teaching education (ITE) and discussions with kaiako is the separation of cloths used for different surfaces and purposes washed separately. However, in the literature this stems from the licencing criteria where it is explained with the reasoning of “different types of laundry washed separately to prevent cross infection” (Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga-Ministry of Education, 2022), so while this practice aligns with tikaka Māori and can be pointed to as fulfilling a well-known tikaka requirement in the policies and documents it neither stems from tikaka nor even acknowledges it. Where tikaka is acknowledge, or example in Te Whāriki (Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga-Ministry of Education., 2017), it is framed as important in building the sense of belonging for Māori learners and their whānau. We do this because they do it this way, no investigation or incentive for kaiako to investigate why or understand the history or underpinning beliefs, rooted in western sociocultural views of recognising home cultures (Rogoff, 2003). The purpose of tikaka in curriculum and policies are to create welcoming spaces for Māori whānau to uphold the belonging and relationship sides of their wellbeing, not to create in centres spaces where tikaka Māori lives for all learners but spaces where Māori learners with home cultures that follow tikaka Māori are affirmed in bringing their tikaka funds of knowledge.

There are benefits to these utilitarian implementations to Māori learners, but also challenges. Through treating Māori beliefs and practices as true for Māori learners, they are affirmed their home cultures upheld, Nimmo, Abo-Zena and LeeKeenan (2019) write how denying or correcting the beliefs and views of the world of home cultures that disagree with western perspectives can leave, especially Indigenous, children feeling shame and like from home is welcome or valued within ECE centres or the world outside their door. This aligns with Te Whāriki strands looking at belonging and ability to build relationships and contribute from a position of affirmed mana (Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga-Ministry of Education., 2017) against the background of a society built on the denouncement of Māori culture (Walker, 2016) and forced assimilation (Milne, 2017). Including tikaka Māori in set activities, recognising local pūrākau and incorporating lessons from them into specific activities and events within the centre can succeed in providing the benefit of confirming the home culture and belonging of Māori learners. However, the benefit of this for non-Māori or Māori who do not have access to te ao Māori in their home lives, is lessened as tikaka recognised as tikaka is contained within it’s assigned places within activities and the routine, contained with ‘Māori stuff’ separate from normal or real ‘stuff’ leaving those learners unable to learn tikaka Māori as normal to provide a foundation for future resistance against the othering of Māoridom by Pākehā society and later education. They are also denied the benefits of tikaka as tikaka. Without the reasons, pūrākau and history to tikaka being taught and lived as it is practiced, a karakia can never connect those singing to the Atua, tipuna and Māori past and future (Rameka, 2016) but remains as the song sung as a routine activity required before you can eat or go home as tikaka is contained.

This contained or incorporated and unsaid approach to ensure higher fulfilment of policy expectations by staff (Hurst, 2022), if effective outlines a larger problem. If tikaka hidden within secular, clinical, western framing of health and safety is followed but tikaka when stated separately as tikaka Māori is not, even in the good examples of inclusive three P’s centres this shows the entrenchment of viewing tikaka as below a ‘real’ required practice even when regulated with the same policies from the same bodies by kaiako.

Mason Durie wrote that was is good for Māori is good for the institution as a whole (Durie, 2011), Mead (n.d.) in an undated interview available through He Kākano programme’s website distils this down to related specifically to students. All students must be comfortable with tikaka Māori, with the customs and social ways of being and doing within te ao Māori so all can achieve and contribute to Māori society. If only Māori students from tikaka Māori breathing homes are strengthened in the practice of tikaka, if tikaka is seen as providing a function only of affirming learners from those homes, then all of society will miss out on the benefits of the guidance of centuries, millennia of Māori tradition and ancestors and culture and worse, tikaka Māori will remain othered, for those who already have it, affirmed, not made to feel shamed in it as under previous education models, but still left as different, second and lesser to mainstream society that does not understand or practice tikaka, but graciously acknowledge it’s important for the othered Māori.

Kaiako see the importance of tikaka Māori practices through the lens Pākehā systems, through the 1989 Education Act (Chan & Ritchie, 2020) and OCOS commitments to te Tiriti’s three P’s (D’Cunha, 2017), Māori families and affirming Māori learners as Māori (Education Council | Matatū Aotearoa, 2017). Tikaka is functional. Practiced in a Pākehā liberal system not as a correct way of doing things, but a diverse and inclusive act to uphold minimum standards of inclusive diversity. Within this framework ECE see’s tikaka not as a connection to the Atua, the very notion is at odds with the secularism of western liberalism. Tikaka does not live as a manifestation of the values and worlds of pūrākau or as an outwards expression of an understanding of te ao Māori. Tikaka is functional, a check list of actions to be carried out in accordance with centre policy with the aim of meeting three P treaty obligations and committee to Māori as takata whenua as required under OCOS (2017).

Kaiako and centres walk forward to a future of greater commitment to Māori learners and more inclusive practices, eyes fixed on lists checked and boxes ticked and while the sector strives ever forward to ever increasing inclusivity of tikaka functions, behaviours, and practices it does not turn around.

There is a whakatauki that started this essay. It is used throughout ECE and ITE to mean, learning the history and context of colonialism on education, learn the importance of affirming Māori learners as Māori through understanding the assimilation and discriminatory practices of ‘the past’. Rameka (2016), uses it in her explanation of the intertwined Māori view of time as a continuous process, tikaka in this view are practices and customs laid down by the ancestors for future generations. The importance of karakia sung before kai time, is not to normalise te reo or fulfil a commitment to takata whenua, but to balance the tapu and noa and make safe a space for the consumption of food through a ritual that connects past, present and future, connects to the ancestors and the Atua. Kai, art and washroom cloths aren’t only separated out of respect for diverse learners but as a consequence of centuries of Māori experience and understandings of the world that are entirely ignored by a system that see’s tikaka functionally as flowing from lists, not underpinnings. This neglects the teaching of the reasons why or stories behind tikaka or even outright excludes them as crossing the line from inclusive to spiritual. Just as the three P’s are a reductionist distillation of Tiriti obligations to accommodate Pākehā (New Zealand. Waitangi Tribunal, 2019), fitting tikaka Māori into the frameworks of OCOS and utilitarian benefits to diverse inclusive practices and supporting the identities of Māori learners removed from their context converts them into functions within the Pākehā world not connections to te ao Māori past and future. Even tikaka policies that are explicitly tikaka and unashamedly Māori such as Ako’s Resource Kit for Graduate Teachers (Williams & Broadley, 2012) while providing greater connections to Māoridom and a holistic view of tikaka than modern examples, being a practical handbook does not contain links to pūrākau or provide the reasons why something is tika or not, just lists them. What hope then is that a health and safety policy that expects Pākehā kaiako to fulfil the tikaka expectations of a policy will give those connections or even admit what is tikaka and what is licencing criteria?

Speaking to the manawhenua representative to the REDACTED about what tikaka practices are needed in ECE, I was told it’s not the practices but the stories behind them that are needed. It is around this that all this revolves, looking to the past to see the links to the Atua and tipuna through pūrākau is what makes tikaka separate from, as I was given as a definition of tikaka by a Pākehā lecture, a Māori word centre policy. Through this lens what is important in these centres and all ECE is this utilitarian implementation without connection to the past.

If tikaka Māori comes from walking backwards into the future through understanding and connecting to the past, ‘tikaka ECE’ walks boldly forward eyes unflinchingly focused on checklists of functional practices pulled from ERO and community expectations rationalised through legal requirements and the well-meaning narrow gaze of including the diverse other.

For as far as ECE has come and how rich it’s grounding in te ao Māori underpinnings and perspectives, even among centres that work in partnership with rūnaka and have a mana whenua representative and many kaiako who fight passionately for te ao Māori. Tikaka is trapped in a functional role separated from the past, from it’s reasons and motivations and from the Atua from who it should stem by the structural entrenchment of Pākehā systems, regulations and views of equality. Tikaka Māori that connects to the past, to the ancestors and to the living cultures of Māori lives in exceptional individuals while purely functional tikaka removed from time, without culture or spirituality is thriving in ECE but without eyes fixed on the past, tikaka cannot live with ECE and the benefits for learners, kaiako and communities limited.

Bibliography

Chan, A. & Ritchie, J., 2020. Exploring a Tiriti-based superdiversity paradigm within early childhood care and education in Aotearoa New Zealand. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 00(0), pp. 1-15 (15 pages).

Cormack, S. & Orwin, J., 1997. Four generations from Maoridom : the memoirs of a South Island kaumatua and fisherman. Dunedin: Otago University Press.

D’Cunha, O., 2017. Living The Treaty of Waitangi through a bicultural pedagogy in Early Childhood. Practitioner Research, 5(2), pp. 9-14 (5 pages).

Durie, M., 2011. Ngā Tini Whetū: Navigating Māori Futures. Wellington: Huia.

Education Council | Matatū Aotearoa, 2017. Our Code Our Standards: Code of Professional Responsibility and Standards for the Teaching Profession. Ngā Tikanga Matatika Ngā Paerewa: Ngā Tikanga Matatika mā te Haepapa Ngaiotanga me ngā Paerewa mō te Umanga Whakaakoranga.. Wellington: Education Council | Matatū Aotearoa.

Gunn, A. C. & Nuttall, J., 2019. Weaving Te Whāriki; Aotearoa New Zealand's Early Childhood Cirriculum Document in Theory and Practice. s.l.:NZCER Press.

Higgins, J. & Goodall, S., 2021. Transforming the wellbeing focus in education: A document analysis of policy in Aotearoa New Zealand. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 16(1), p. N/A.

Mead, H. M., n.d. What's good for Māori students is good for all students / Sir Sidney and Lady June Mead / Videos / Toolkit / Homepage - He Kakano. [Online]

Available at: https://hekakano.tki.org.nz/Toolkit2/Videos/Sir-Sidney-and-Lady-June-Mead/What-s-good-for-Maori-students-is-good-for-all-students

[Accessed 6 May 2022].

Mead, M., 2003. Tikanga Māori: living by Māori values. Wellington: Huia.

Metge, J., 1986. In and Out of Touch: Whakamaa in Cross Cultural Context. Wellington: Victoria University Print.

Milne, A., 2017. Coloring in the White Spaces: Reclaiming Cultural Identity in Whitestream Schools: Chapter 6: Coloring in the School-Learning Space.. Counterpoints, Volume 513, pp. 95-127.

New Zealand. Waitangi Tribunal, 2019. Hauora : report on stage one of the Health Services and Outcomes Kaupapa Inquiry. WA I 2 5 7 5 ed. Lower Hutt: Legislation Direct.

Nimmo, J., Abo-Zena, M. M. & LeeKeenan, D., 2019. Finding a Place for the Religious and Spiritual Lives of Young Children and Their Families: An Anti-Bias Approach.. YC Young Children, November, 74(5), pp. 37-45.

REDACTED.

Rameka, L., 2016. Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua: ‘I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past’. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, December, 17(387-398), p. 4.

Rau, C. & Ritchie, J., 2011. Ahakoa he iti: Early Childhood Pedagogies Affirming of Māori Children's Rights to Their Culture. Early Education and Development, October, 22(5), pp. 795-817.

Rogoff, B., 2003. The cultural nature of human development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga-Ministry of Education., 2017. Te Whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa early childhood curriculum. Wellington: Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga-Ministry of Education..

Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga-Ministry of Education, 2022. Licensing Criteria for Early Childhood Education & Care Services 2008: and Early Childhood Education Curriculum Framework. 1 January 2022 ed. Wellington: Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga-Ministry of Education.

University of Otago, 2022. Bachelor of Teaching (BTchg). [Online]

Available at: https://www.otago.ac.nz/courses/qualifications/btchg.html

[Accessed `5 May 2022].

Walker, R., 2016. Reclaiming Māori education. In: J. Hutchings & J. Lee-Morgan, eds. Decolonisation in Aotearoa: Education, research and practice. Wellington: NZCER Press, pp. 19-38.

#MAOR202 Māori and Tikanga#Essay#Māori & Indigenous Studies#Indigenous Studies#2nd year#University Essay#My first A+

0 notes

Text

@angitukapa ANGITU x @harrystyles! SWIPE RIGHT TO SEE HARRY’S FIERCE PŪKANA! Ka mau kē te wehi, e te rangatira 👏👏 Such a humble, genuine person, thank you for sharing memories, e hoa! ✨ Ka nui ngā whakamānawatanga ki a @livenation - kua ora ngā tikanga i a koutou, e tai mā

569 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Māori climate activist breaking legal barriers to bring corporate giants to court

In a landmark case, Mike Smith has won the right to sue seven of the country’s biggest companies over their alleged contributions to climate change

In a landmark decision in February, New Zealand’s supreme court unanimously ruled Smith has the right to sue seven New Zealand-based corporate entities, including fuel companies Z Energy and Channel Infrastructure, power and gas company Genesis Energy, NZ Steel, coal company BT Mining, Dairy Holdings and the country’s largest, and biggest emitting company dairy exporter Fonterra, claiming they contributed to climate change.

[...]

For Māori, a love of the environment “is built into us” Smith says, and when it comes to the disastrous effects of climate change the “future of our children and our grandchildren is on the line”.

“That means when we see these things happening, we can’t just sit there and be silent – we must be responsible, and that sets us on a collision course with some of those economic and political systems that would destroy that relationship.”

[...]

A distinctive element to Smith’s case is his argument that principles of tikanga Māori – broadly, a traditional system of obligations and recognitions of wrongs – could inform his action and moreover, should inform New Zealand common law generally.

The companies applied to strike out Smith’s proceedings in the lower courts, arguing, in part, that Smith’s claim was “incoherent” and would damage the integrity of tort law. In 2021, the court of appeal agreed, believing the case doomed to fail and struck it out.

But in a major reversal, the supreme court said a judicial pathway should be open and common law should be able to evolve. It acknowledged climate change was an “all-embracing” existential crisis and said the law should take into account the 21st-century context.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

angitukapa: ANGITU × @harrystyles

SWIPE RIGHT TO SEE HARRY'S FIERCE PÜKANA! Ka mau kê te wehi, e te rangatira is Such a humble, genuine person, thank you for sharing memories, hoa! I

Ka nui ngã whakamanawatanga ki a @livenation - kua ora nga tikanga i a koutou, e tai ma

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

māori solidarity with palestine in aotearoa. the caption of the post reads:

“Gonna need everyone on board this one, share, like, comment. Let’s set the record straight. Māori stand unequivocally with the Palestinians not like Destiny Church who supports the colonisers and genocide. Not the tahi i say.

This is dedicated to the mothers and fathers who have lost their precious children and to the children who lost all their hopes and dreams for themselves. We love you.

The haka was done at the inception of Te Whare Tū Tauā at Rākautātahi marae in Rangitōtohu land, under the shelter of the Ruahine ranges and outlooking towards Te Hinaki Nui a Whata. It was done with the blessing of our tohunga tū tauā Johnny Nepe Apatu and the other rangatira of Rākautātahi marae. Te Whare Tū Tauā is home to the greatest weapons artists in all of Aotearoa and is a keeper of tikanga, kawa and mātauranga Māori.

We stand with the innocent civilians of Palestine. Ka whawhai tonu mātau ake ake ake!”

25/09/23

#💞💞💞💞#this came up on my instagram and i thought it would b good to share here too#as thats what hes asked for#palestine#aotearoa#free palestine#from the river to the sea#sj#people

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I realised now lo’ak feeling like he’s a demon and that he’s not na’vi because he has human features is another representation of how indigenous people now a days are often mixed with other cultures as well and how that’s seen, for example I’m māori and Samoan our ancestors were brown skinned, with my Māori side I’m more accepted although I am fair skinned and look different from the rest of my family, I know the language, the culture and the tikanga (rules in our world) but I often got questioned about whether or not I was a real māori bc of my skin colour, I was often brought down because of it despite how I raised in the culture. But with my Samoan side I’m less accepted, I’m an afakasi to them which means a half cast. Half cast are looked down upon in Samoan culture most times all because my father was fair skinned and my mother wasn’t. Lo’ak represents all indigenous children who grew up different from the rest, the ones who looked different and never felt like they had a right to belong because of how they looked. I think that’s totally valid.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

tagged by @fullmetalscullyy, @firewoodfigs and @littlewitchbee for the greatest hits of 2023. ty all for the tag!!! i admit, it did take me a little bit to think of 10 diff things that i found good, so a new addendum to my usual 5 new years resolutions is to make a point of noting down these good things, lest they be lost to the ether like the others haha

my beloved eri came to visit me and it was such a joy to welcome her into my home and just talk and gossip. we got to feed penguins!!! i got to show her the milky way!!!! we got drunk and watched hunger games with emma. i'm so blessed to have friends that are so dear i want them to come crash at mine and i want more of these sorts of things to happen (as best we all can in a cost of living crisis lmaooo).

speaking of friends, i'm pleased to say that i was able to grow my small group of friends -- online and off -- to slightly-less-small! y'all know who you are, and i'm grateful to each and every one of you <333

i got a lot of tattoos. they're dope. my artist is like my tumblr feed personified. she just Gets It.

i built my own pc!!! it was a very scary and intimidating process, but she runs baldurs gate 3 like a CHAMP. (anything for my astarion).

i successfully finished nano, and now this month i'm basically doing another nano as i try to finish up this new fic. i cannot believe that i've broken 100k words and i'm STILL not done. maybe with a 150k draft i'll have a story in a coherent plotline (doubtful. i waffle a lot. rip moobeam who promised she'd edit it for me).

i've also gotten back into reading fiction a little more seriously -- entirely because of emma, but i am very grateful for her reccomendations. there's a few of us doing a bookclub and i cannot wait to have a discussion this month when we're all at the halfway mark!!! it's gonna be lit.

in other real life stuff, i worked really hard to build up my savings. hopefully 2024 will bring more money to me, or at least i'll get a better handle on my spending. (she says, despite booking flights and holidays HAHAH).

part of that ethos was investing in pieces of clothing/accessories that would stand the test of time, and i want to continue these kinds of purchases into the new year. i think the next big purchase for me will be a replacement pair of leather boots -- my current ones are getting towards the end of their life with the inner sole.

despite working full time, i also completed two seperate courses for study! one was directly related to work, but the other was for purely personal pleasure: an introductory course for tikanga māori. the next step of the tikanga course wasn't avail for me this year, so instead i've signed up for night classes for te reo māori instead. i want to incoporate more reo into my work and feel more confident in conversations, so this was a natural step. i've also got another work-related course on my plate too, so i will be a very busy bee for 2k24 hehe.

in 2023 my health had to take a bit of a backseat but in the last few months i was able to get back on top of it! this year is already off to a great start for me: i'm getting back down to a more comfortable weight, my strength is still improving, and my mental health and sleep hygiene are feeling more... within my control??? i've sorted out my priorities a bit there. turns out living on 4 hours of sleep on the regular isn't healthy lmfao

tagging @beesbeesdragons, @mountainhaunt, @liquorisce, @soufflegirl, and @dairogo -- only if y'all want to!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archbishop Justin apparently! He has inarguably changed the culture of the Wellington diocese, excited to see what this looks like for the whole Tikanga Pākehā!

#i love what's happening in wellington it has been amazing#i have been sad to move away and so excited to move back to the diocese soon#tau kē bishop justin!#faith musings

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

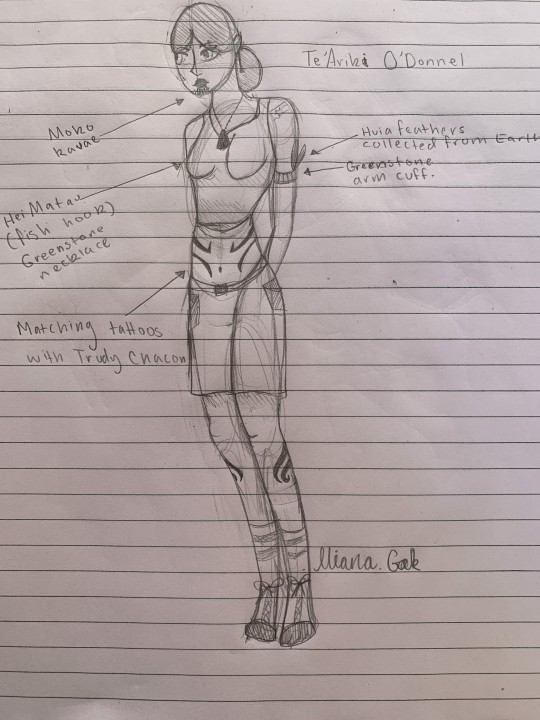

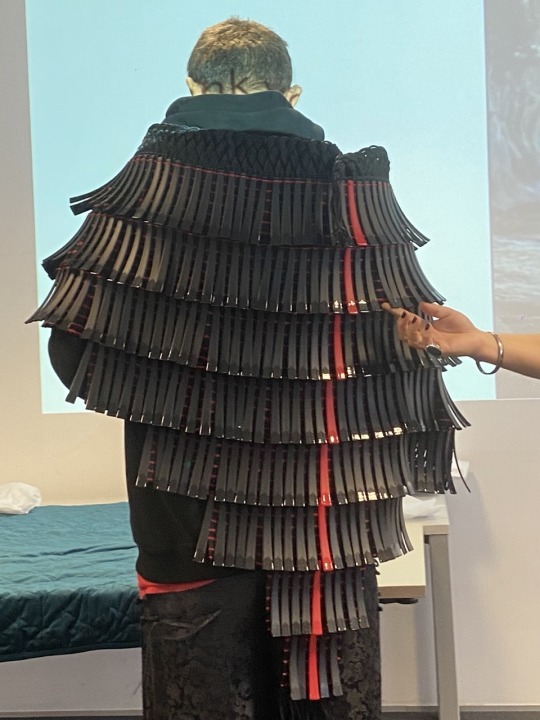

Workshop Week (pt. 1): Te Rongo Kirkwood

My first official blog post - how exciting!!!! ^__^

Our first week of the Sustainable Fashion Design degree kicked off with a 'workshop week', featuring a diverse array of activities and guest speakers. In this blog post, I'll focus on our first guest speaker: Te Rongo Kirkwood.

Te Rongo Kirkwood, an Auckland-based multi-medium artist, specialises in kiln-formed glass and the integration of art glass with various other materials. Her work is characterized by meticulous craftsmanship and a holistic/spiritual approach. What struck me most about her work was not just its aesthetic beauty, but also the depth of meaning and connection she infuses into each piece.

I found myself captivated not only by Te Rongo's artistry but also by the challenges she has overcome to reach her current position. Her passion for her craft and the personal significance it holds for her were truly inspiring. Having the opportunity to learn from such an incredible artist and individual was an honour, and I couldn't have asked for a better introduction to our course.

Te Rongo is of Māori (Wai o Hua, Ngai Tai ki Tamaki, Te Kauwerau a Maki, Ngapuhi, Taranaki), English and Scottish heritage [1] and this is heavily reflected through her works, both physically and spiritually. Kirkwood incorporates a Tikanga Māori worldview into her work by grounding her work in Māori principles such as Whakapapa “(or genealogy), a line of descent from ancestors down to the present day. Whakapapa links people to all other living things, and to the earth and the sky, and it traces the universe back to its origins. Through Whakapapa, Māori trace their ancestry all the way back to the beginnings of the universe. Whakapapa orders both a seen and unseen world, and shapes the Māori world view.” [2]

This interconnectedness of all things serves as the foundation of Kirkwood’s work, inspiring me to explore similar themes in my own designs, despite coming from a different cultural background. Although I am of Pakistani and Afghani descent (and not of Maori descent) there are many shared ideas regarding community, culture and spirituality between our respective cultures that are of great significance to me that I would love to explore in my own work as a designer.

Fashion design, as Te Rongo emphasised, is about storytelling. It's not just about creating beautiful garments, but about conveying deeper meanings and messages through them, and this resonated deeply with me. While I want my work to be aesthetically beautiful, I want its meaning to be what takes precedence.

Te Rongo urged us to use our art as a means of communicating something larger than ourselves, prompting us to consider, "What is my service to the world?" Her words left a profound impact on me, shaping my understanding of the role of art and design in society.

I had originally planned for this 1st blog post to be a summary of both of our Guest Speakers from the first day, but as I reflected on my notes for the day and worked on this write-up, it became apparent to me that the richness of the knowledge departed to us by Kirkwood required a post of its own. I genuinely can not think of a better introduction to this course and to my blog than Kirkwood’s guest lecture. Kirkwood instilled in us the importance of being clear, unapologetic and uncompromising when it comes to our values in art, and this is something I plan to carry with me for my entire life and in everything that I do.

Thank you to Te Rongo for taking the time to share her wisdom with us, and to Whitecliffe for facilitating.

Signing off for now,

Adam <3

References

[1]

[2]

Photos (in order of shown):

1:

https://coastalartstrail.nz/event/artist-talk-te-rongo-kirkwood/

2:

3 & 4:

5 & 6:

7 & 8:

9 & 10: Own

1 note

·

View note

Text

How will ChatGPT impact te reo Māori? Data sovereignty experts weigh in | RNZ News

Na ez a másik fele, ha nem használok te reo nyelvi elemeket akkor ignorant vagyok, ha használok akkor rosszul csinálom és\vagy elveszem mások kultúráját, ha a chatgpt akkor nem ér hogy hozzáfér a kulturális elemeimhez, amit viszont a közösség finanszírozzon h promótálva legyen de maradjon az enyém, és amire én azt mondom tikanga ahhoz ne férhessen hozzá, de mindenki férjen hozzá hogy legyen felette kontrollom

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Māori unity is one of the best and strongest feelings ever. A beautiful farewell to kiingi tuheitia and celebrating being Māori no matter your beliefs, your tikanga, iwi….

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Tikanga - - - Fulu Miziki Kinshasa Music Warriors

Fulu Miziki is a collective of artists who comes straight from a future where humans have reconciled with mother earth and with themselves. This multidisciplinary collective of artists is based in the heart of the Congolese capital city Kinshasa and was founded by Pisko Crane. For several years now, it’s founder Pisko has spent an amount of time conceptualizing an orchestra made from objects found in the trash, constantly changing instruments, always in search of new sounds. Couples of years ago, Pisko Crane joined efforts with performing artist Aicha Mena Kanieba who, with Le Meilleur, DeBoul, La Roche, Padou, Sekelembele, and Tche Tche formed the Eco-Afro-Futuristic punk ensemble Fulu Miziki. Making our own performance costumes, masks and instruments is essential to their approach of Fulu Miziki’s musical ideology. Their unique sound supports a pan-African message of artistic liberation, peace and a severe look at the ecological situation of the Democratic Republic of Congo and the whole world. For Fulu everything can be recovered and re-enchanted.

#Fulu Miziki Kinshasa Music Warriors#Kinshasa#Congo#Eco-Afro-Futuristic punk#afro punk#Democratic Republic of Congo#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes