#Worldbuilding ∵ ( vistas and landscapes. )

Text

dreaming and IRL worldbuilding

I’ve been doing some talking about getting into radicalism and how to organize. You can do that first—you have a feeling that things need to change and you just act. At some point though, I think it’s important to start thinking from a longer-term perspective. That's where visioning comes in.

To know how to change the world, we should know what we want it to look like. Solarpunk is a great example of this—giving us aspirational visuals and vistas for how the world could look if we got our shit together. This is what a vision is in a nutshell.

Once we have have an understanding of what we want the world to look like, we have to figure out how to get there. This is where things start to become interesting. To me, values are like guiding principles that we ground our actions in. To come up with values, think about the ethics and principles that are embedded in your vision. If we think about solarpunk, some values that I see are ecological harmony, intersectional feminism, and economic democracy.

When we have our vision and values in place, we can think about the specific things that we want to accomplish. Our goals should be relatively concrete things that we can build strategies around. What are the material changes that you want to happen? What are the specific, tangible things that you can work towards? If it’s too broad (ex: “I want to abolish the commodity form”), then that might be one of the descriptors of your vision.

So, you create a vision → which informs your values → and dictates your goals.

To develop a vision, put on your dreaming goggles. Imagine what the world can look like. Try to engage your senses. What do you see? What do you hear? What does it smell like?

To develop your values, look at that vision, analyze the implied material and social contexts and use those as guiding lights.

To develop your goals, think about the specific things you can work towards, acting within your values, to create fertile ground for your vision to flourish.

To wrap up, I want to walk through a vision of a better world. If you want some homework, you can derive some values and goals from that.

---

As I leave my house for the day, I step out onto a quiet city street. The air is crisp and filled with the scent of freshly bloomed flowers and the subtle aroma of earthy, homegrown herbs. The street is lined with majestic, towering trees, their leaves dancing in the gentle breeze, casting shattered shadows on mosaic sidewalks below.

As I walk along the street, I hear the melodies of birds chirping, flitting from mossy building to wild rooftop. The sound of laughter and lively conversations fills the air, as people gather in community spaces and reclaimed streets.

The buildings themselves are architectural wonders, adorned with solar panels and living walls that burst with vibrant vegetation. They harmoniously blend into the surrounding natural landscape, their design inspired by historical ecological buildings. These buildings are not just structures; they are living organisms, integrated with the ecosystem, providing shade, shelter, and sustenance for both humans and wildlife.

Streets are bustling with activity, but they are not dominated by cars. Instead, it is a pedestrian-friendly space where people of all ages and abilities move freely and safely. Electric trams silently glide by, their sleek design reflecting the beauty of their surroundings.

Local artisans and worker-owners have set up vibrant market stalls, showcasing their handmade creations and locally sourced goods. Vibrant textiles, handcrafted jewelry, and organic produce catch the eye. Neighbors stop to chat, share stories, and exchange ideas.

In the distance, I see a community forest garden, a lush oasis of greenery where residents gather to cultivate their own food. The garden is a testament to space reclaimed by the people, fostering a sense of ownership and connection to the land.

As I continue my walk, I feel a sense of hope and possibility. This city is a testament to the power of collective action and the transformative potential of dreaming and envisioning a better world.

#economics#economy#econ#anti capitalists be like#neoliberal capitalism#late stage capitalism#anti capitalism#capitalism#activism#activist#direct action#solarpunks#solarpunk#praxis#socialism#sociology#social revolution#social justice#social relations#social ecology#organizing#complexity#resist#fight back#organizing 101#radicalization#radicalism#prefigurative politics#politics#storytelling

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#sketch#worldbuilding#Mars#landtrain#vehicle#horse#hat#staff#vista#landscape#notes#Imago#imagohominis#ordidItagit#imago hominis#idkman#mask#vest#demihuman#gengineering#gasmask#stuff

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

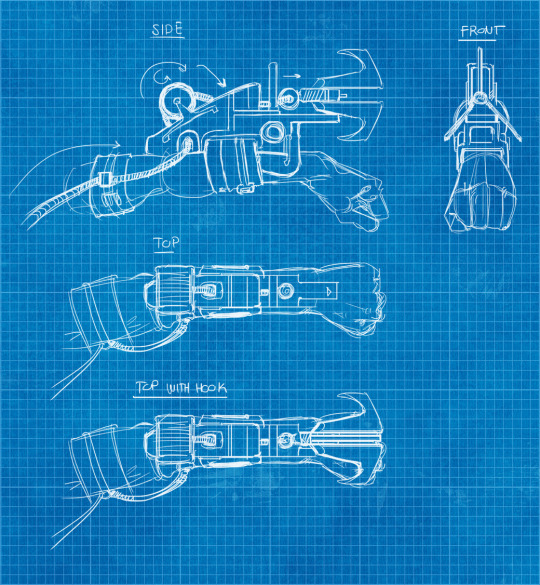

Supplemental Casenotes for Case #35-TH032

Compiled by Constable A.J. Perkins

Summary:

Supplemental notes for Case #35-TH032, which pertains to a theft from Piltech Innovations. A hextech “grappling gun” and associated equipment were reported stolen the morning of 11th Rain. (Design schematics of the device are attached to this document.) Preliminary investigation reveals few leads, as the laboratory’s security system appears to have been damaged and wasn’t fully operational at the time of the theft.

Scene:

All hextech inventions, whether fully completed or partially built, were kept in Piltech Innovations’ storeroom, which was thaumaturgically secured. The storeroom was locked according to Marcus Hill, who discovered the theft. Individual inventions were stored in separate secured lockboxes to prevent potential reactions due to long-term cross-exposure.

The lockbox containing the “grappling gun” was closed but unlocked, according to Mr. Hill. All other lockboxes were secured, and an inventory conducted by our investigative team and the laboratory’s inventors concluded that nothing else was taken.

The storeroom had one security camera. See processing section for more details.

Processing:

Piltech Innovations’ security footage was examined. Unfortunately, no recordings were made on 10th Rain. It appears that the security system was damaged in some way six days prior, according to the laboratory’s security team, and that the damage resulted in the system being unable to store recorded footage. Repairs weren’t considered a priority due to the laboratory having day- and night-shift security.

Our investigative team dusted for fingerprints, focusing on areas the thief most likely touched. (The door, opened lockbox, nearby lockboxes, etc.) No fingerprints, including partial prints, were found.

Evidence Collected:

“Grappling gun” schematics, attached. Given over by their creator Iva Kovac.

Security footage from the seven days prior to the security system being damaged on 4th Rain.

Photographs of the storeroom as it appeared when our investigative team arrived.

Pending:

Some witness interviews need to be completed.

—

Witness Information for Case #35-TH032

Compiled by Constable A.J. Perkins

Marcus Hill, Engineer

Discovered the theft. Has worked at Piltech Innovations for two years. Describes himself to be the first to show up in the morning and the last to leave at night, discounting security. Miss Lu attests that he left the building at around 6pm. Has an alibi for the night of the 10th - attended a social gathering with friends and family, who vouch for him. Arrived at the laboratory at around 8am, and claims to have discovered that the “grappling gun” was stolen due to wanting to check its functioning.

Iva Kovac, Engineer

Creator of the stolen invention. Has worked at Piltech Innovations for one year. Currently in possession of an employment-based visa due to her Zaunite nationality. Miss Lu attests that she left the building at around 5pm. Arrived at the laboratory when informed about the theft. Claims to have spent the night of the 10th at home.

Miss Kovac informed investigators that the stolen “grappling gun” was commission work for a client, Lucas Phelps. Mr. Phelps has not been able to be contacted at this time.

Andrea Snyder, Engineer

Engineer at Piltech Innovations. Has worked at Piltech Innovations for five years. Had been out sick since 8th Rain, and claims to have been home recovering at the time of the theft.

Kaleb Bullard, Head Engineer

The engineering lead at and founder of Piltech Innovations, which opened five years ago. Miss Lu attests that he left the building at around 5pm. Arrived at the laboratory when informed about the theft. Spent the night of the 10th out to dinner with his husband - the two claim to have returned home at around 10pm.

Benjamin Woods, Day-Shift Security

Member of the day shift security team, primary shift. Has worked at Piltech Innovations for two months. His shift lasts from 6am until 2pm. Helped Mr. Hill report the theft. Claims to have been at home, studying, for the night of the 10th.

Holly Lu, Day-Shift Security

Member of the day shift security team, secondary shift. Has worked at Piltech Innovations for one year. Her shift lasts from 2pm until 10pm. Claims to have seen nothing out-of-the-ordinary on the security cameras during her shift. Mr. Dale attests that she went home after shift change on the night of the 10th, and she claims to have spent the night at home.

Edward Dale, Night-Shift Security

Sole night shift security guard. Has worked at Piltech Innovations for seven months. His shift begins at 10pm and lasts until 6am. Claims to have seen nothing out-of-the-ordinary on the security cameras during his shift.

Mr. Bullard told investigators that Mr. Dale has previously shown negligence to his security duties, but that he hasn’t been replaced due to a lack of interest in the job offer.

—

Addendum: Due to lack of evidence and the amount of time elapsed since the theft, Case #35-TH032 is considered unsolved. Lucas Phelps was never able to be contacted by investigators, and did not contact Piltech Innovations.

#Writing ∵ ( woven with words. )#Worldbuilding ∵ ( vistas and landscapes. )#ever wonder how jules got that grappling gun of his? now you know! featuring ikleyvey's art and a character reference to her

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Outer Worlds

Played for about a week and a half, finished today.

So... it’s not Fallout in space. At least, it didn’t have any Fallout mechanics. I don’t think I would have even related it to fallout except I knew that Obsidian was the original developer of the Fallout franchise. It reminded me a bit of Dishonored, if I’m honest.

No story spoilers below the cut.

Overall, is it worth playing? Definitely. If you’ve been wandering in the desert, thirsting for a single-player RPG, this will quench ya. There are companions, loads of dialogue choices, lots of choices period. I believe you can actually kill anyone in the game (except for one person maybe?) And there’s a rich, unique world to explore.

The Good

- Beautiful settings and vistas. The color palette was liberally used in this game and nearly everywhere I stopped was a good place just to look at the landscape or up into the sky at the swirling gas of a planet above.

- Sprats! They’re so cute. If you’re out at night , you can find them curled up and when they wake up their ears wiggle and they yawn.

- The worldbuilding of having corporations be in charge of everything was very well done, down to employees identifying strongly with their brand and their very selves as Employee. I like that the writers took the time to take the premise to such an extent.

The Bad

- Companions are... okay. With the exception of Parvati and Ellie, I felt like their personalities weren’t very memorable to me, and SAM had no point at all. I didn’t feel like there was any new Kaidan or Deacon, characters that will stick with me for years to come. However, there was plenty of banter and also companion quests, which I always enjoy.

- Repetitive enemies. This is a comparatively small game (which isn’t a criticism), so it feels like the enemy encounters were scaled down to only two main factions, with robots as a smaller third. Marauders are all the same on each planet and so are the animals, with the big bads the only difference.

- Quest objectives sometimes unclear. I was sometimes confused as to why I was doing something or going somewhere in some of the side quests.

- Upgrading armor and weapons wasn’t as fun as it is in other games. Not sure why this wasn’t hitting that tinkering itch for me, but it wasn’t. It felt like a chore instead of hitting that right balance of fun upgrades.

The Ugly

- There is literally no point in the character creator. None. You never see your character except when managing inventory. Their face or body never appears while playing the game because there is no third-person POV.

- Text is soooo small on this game. I stopped reading description text pretty soon after starting the game because it was so small, which is a shame because the writing on them was clever. I have a big TV and I don’t sit on the other side of the room. I should be able to read any text.

- Map issues. No waypoints; the cursor is incredibly slow, and you can’t access the map via a quick button tap, if you want to view the map, it’s at least three or four button taps every time.

- Consumables are basically useless but they take up about 90% of the space in your inventory. Note: I played on Normal, so if they have a better use in higher difficulties, I don’t know.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Short Reflection: Tales from Earthsea

Tales from Earthsea has earned a bit of an unfortunate reputation for itself as the Ghibli Film that it’s okay to dislike. Directed by Hayao Miyazaki’s son Goro, the finished product was apparently so underwhelming to Hayao that he would joke in the future that while he was happy Goro had made a film, he would dissuade his son from making another one ever again. But honestly, after actually seeing the movie, I’m gonna have to disagree with the maestro, because I think Tales from Earthsea is a genuinely powerful film. It’s certainly not the best of the Ghibli canon, and it definitely bears the marks of a first-time director, but it’s an admirable effort coming from a place of genuine passion and empathy, a stirring experience that touched me in profound artistic ways I wasn’t expecting going in. In fact, it feels very much like a purposeful reconstruction of the kinds of ideas and themes that Daddy Miyazaki himself has been exploring since the beginning of his career. A fantasy world in some state of decay, caught between man and nature as humanity struggles with the responsibility to live side by side with the natural world, a combined guy/girl protagonist team tasked with keeping that peace... it’s like a love letter to Castle in the Sky, Naussicaa, and Princess Mononoke, the tripytch of Ghibli films that cemented their director as the biggest champion of radical environmentalism since The Lorax. And with just a little more polish, I would absolutely consider Tales from Earthsea worthy to stand among that pantheon. Give your son another shot, Hayao; he’s got the potential to make something really special.

At any rate, where Earthsea differs from the kind of Miyazaki film it apes is that while Laupta, Naussicaa et all are set in world building themselves back up after some long-ago disaster, the world in Earthsea feels like it’s still in the process of falling apart. It’s set in a land with castles and dragons and pastoral landscapes and big bazaars and magic and wizards and all manor of trapping of Tolkien-inspired fantasy worldbuilding. But this is not a bustling world full of life and vigor; from the very first scenes, the air is filled with an atmosphere of impending doom. The regal dragons that populate the skies have started fighting each other, an event that spells ill omens for the future. There is plague and famine sweeping the land, and it’s all the kingdom can do to keep afloat. Over the course of the movie, we visit no shortage of crumbling ruins and grime-flecked streets, remnants of lives and histories in the process of falling apart, being swallowed by pettiness and cruelty and despair and emptiness. We learn that wizards have mostly lost their magic, and the few spells we see cast feel more like ancient druidic rituals born from long-forgotten eldritch power. This atmosphere is the film’s strongest aspect, leeching into your bones over time and filling you with a kind of quiet ache that only grows stronger with every new vista of haunting stillness and gloomy dread. There’s a very Dark Souls feel to the world of Earthsea, like our heroes are traveling around the remnants of a once great civilization now fading into the sands of time. And it’s all supercharged by the color palette and soundtrack, casting the landscape in deep, ponderous shades of hue and groaning, ancient dirges that seem to wail for the majesty of times long since past. It feels like a world you could get lost in, a world that could swallow you whole without leaving a trace that you ever existed.

That despair-tinged atmosphere extends to the film’s themes as well, which center on a young man caught at the crossroads of life and death and finding himself unable to move forward. Aaron is the prince of the kingdom, son of a good king, who nevertheless finds himself afflicted by a mysterious rage that drives him to kill his father and run away to the wastes. There, he finds solace with a wandering mage named Sparrowhawk, and lacking any greater purpose or goal, he finds himself listlessly tagging along with the wizard, hoping to escape from his shame and sorrow in the presence of unfamiliar people and locales. But it quickly becomes clear that he’s become embroiled with someone with much bigger plans than simply wandering the wider world, and in time, Sparrowhawk’s ultimate goal forces Aaron to come to terms with his fears and regrets, standing up to a danger that reflects his worst terrors back at him. It’s in his story that Tales from Earthsea finds its meaning, reflecting the protagonist’s own faults and fears in the decrepit state of the world at large as he grows strong enough to change himself- and symbolically, the world as well- for the better. It’s a story about a young boy more afraid of life than death, who would gladly throw himself on the wrong end of a sword if it meant ending the thick fog of misery that hangs over his head. But it’s also a story about the beauty of life he comes to discover, the beauty of the awe and majesty he comes to see in the world around him, of the simple grace of the people he encounters. There’s a particular moment about halfway through the film where Aaron comes across the Ghibli-branded spiritually important leading lady, here a reckless recluse who has never shown Aaron an ounce of trust before, as she’s singing a haunting, yet riveting melody to herself in the middle of a field, her voice echoing across the soft, sweeping plains like a plaintive cry for hope in the face of despair, and by the time it’s over, well, I was almost tearing up right alongside Aaron. It’s the kind of moment that makes me feel like the bag-filming kid from American Beauty, so struck by the beauty of the world that I feel like I can’t take it.

It’s unfortunate, then, that the actual plot facilitated by this incredible story isn’t as strong as it could have been, though the extent to which it rises or falls it a bit more of an open question. Another note this movie takes from Dark Souls is that it doesn’t tend to answer a lot of worldbuilding and lore questions for you, telling most of its greater story through implication. As such, it relies on the emotional and thematic resonance of its ideas to make up for the lack of clear explanations. It’s purposefully mythic storytelling prioritizing emotional resonance over strict logical coherence. We’re never given explicit answers for how dragons and humans once started as the same species, but we’re made to understand the thematic importance they serve in the story as the symbolic representation of the kind of pure, honest freedom and hope this world longs for. We’re never told how exactly the wizards’ magic is fading with the rest of the world, but we understand it as a metaphor for the land’s inner life being swallowed by fatalism and despair. We never know the mechanics of how the film’s ultimate villain plans to open to door between life and death, but we understand that his desire serves as a dark reflection of Aaron’s own desire to be free of the uncertainty and pain of life as he knows it. And there are a handful of spoiler-y moments that raise huge questions about how the lore of this world actually works without ever answering them, because the function they serve in the overall thematic narrative is more important that tying together all the specific details of the mechanics of this fictional universe. It’s a movie that relies on your ability to be okay not having your questions answered, to accept the flow of information as it comes and tackle every step forward on its own emotional terms.

Thankfully, I happen to be exactly the kind of person who prioritizes emotion over logic in storytelling, so the faults in Earthsea’s overall construction didn’t bother me that much. I was perfectly able to get sucked up in the storytelling, in the majesty of the world and Aaron’s journey, without worrying about not knowing the specifics of how it functioned. In a way, I love that it allows you to ask your own questions, wondering how some of the more out-there lore details would be fully realized with the power of your own imagination. That said, there’s definitely an unevenness in the film’s handling of that open-ended nature that isn’t present in, say, Spirited Away. In a way, I almost with it left things more open to interpretation; there’s a handful of moments where it feels like the movie goes too far in trying to explain what it’s all about when I was having a perfectly fine time following it already. In a way, it’s both too obvious at times and too obscure at times, over-explaining its thematic narrative at certain key moments while leaving the actual mechanics of that narrative’s realization fairly obscure. It’s clear that this was Goro’s first film, as there’s a sense that the storyteller isn’t fully confident in the audience’s ability to grasp such an abstract narrative, so he over-corrects in some areas and under-corrects in others. It ends up jarring your expectations at times, when you’re not certain whether or not the movie has more to reveal about a certain plot point or idea of if it expects you to take what it’s already given you as the full picture. The story is still incredibly strong, it just needed an editor to push all of its pieces more firmly into place, someone with the confidence to leave unanswered what could be left unanswered and explain only as much as needed to be explained at any given time. With that kind of finesse, I would have no qualms calling this film an outright masterpiece.

Still, not living up to the work of one of the greatest directors on the face of the earth, especially on your first attempt, is far from the worst criticism to see leveled against you. Tales from Earthsea isn’t a perfect film, and it’s definitely uneven at spots, but it’s got a stunningly powerful core that honors the legacy of the works it draws from while still feeling like its own creation. It’s a stirring fantasy tale of epic adventure and lost worlds coming to life, realized in spectacular fashion with timeless themes and stirring storytelling that more than makes up for the occasionally awkward construction. Don’t be fooled by its reputation, this one’s a real winner. And I award Tales from Earthsea a score of:

7/10

And that’s another Miyazaki Monday complete! This is the last one I’ll be able to get to before my massive Japan trip coming up, so I’ll see you all on the other side of that! And next time, we tackle another classic of the Ghibli cannon I’ve been excited to get to for a while. See you then!

#anime#the anime binge-watcher#tabw#tales from earthsea#gedo senki#hayao miyazaki#ghibli#studio ghibli#ghibli sr

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

All I want is to make something that emulates the unassuming grandeur of Brothers a Tale of Two Sons.

But then, the best part of the game is that it only works so well as a game. The story isn’t amazing or unique but the way it uses the medium just makes it work. It tells this story in a way only a video game can and that makes it, for me, so powerful.

I just love this game. The world builds through things you see and interact with, but without any explanation because there isn’t dialogue. Things like a valley full of giants’ bodies and a village full of frozen people are just there. They just exist, and that kind of worldbuilding is so interesting to me because the world feels lived-in, it feels strange, it feels bigger than these two brothers and their village. And none of it needs an explanation because in the end, it’s not important to their journey.

And the game is just beautiful too, the art style is a little cartoony and so colorful and the scenery is gorgeous. That’s what I mean by the unassuming grandeur, the level design is very vertical and the landscapes are gorgeous, so you get these vistas of where you’ve gone and where you’re going. And the music!! The music is slightly less unassuming, but it’s beautiful.

Anyway I love this game, you should play it, and you should play it with a controller.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andrew Todd’s review of Playdead’s Inside (x)

Playing the final act of Inside, I gasped in awe, recoiled in horror, cackled with laughter, and danced with excitement at the sheer audacity of the thing. Without spoilers or hyperbole: it’s probably the finest final act of a video game I have ever played.

Not that the rest of the game is some kind of disappointment. Playdead’s followup to Limbo is packed with haunting visual and aural design, clever puzzles, and elegant storytelling. At four or so hours, it’s an incredibly concentrated burst of imagination that outdoes its predecessor in just about every way - then almost mandates you jump in and play it again. It’s also a challenge to review: all I want to say is “do not read spoilers; do not pass Go; just play this goddamn game as soon as you can.”

Inside’s basic design echoes the simple, monochromatic puzzle-platforming of Limbo, but adds a number of literal and metaphorical dimensions. The graphics and environment are rendered in beautiful 2.5D, with Playdead putting all those Limbo dollars to good use. Vegetation sways, water ripples, and dust billows in a desaturated world that leaps off the screen like a series of digital paintings. The unnamed, exceptionally well-animated young protagonist starts out in spooky woods, but soon finds himself up against an industrialised machine-state. Piles of slaughtered pigs are just the beginning of the horror he'll find: as he descends into a nightmarish city, the vistas and goings-on get far stranger than anyone could reasonably expect.

I really can’t stress enough how weird and disturbing Inside gets, and I’m straining against powerful urges to avoid spoiling its surprises. Suffice it to say that the horror of Inside is not limited to scary environments or beastly creatures. It's far deeper than that.

In part, the story is told with visual and audio clues both overt and subtle, creating a growing sense of unease as its mysteries deepen and unfold. Not a single word is uttered in the entire runtime, and the only visible text are numbers guiding you (or are they?) towards your ultimate destination. Through your actions, but also through scripted animations taking place off in the distance, Inside paints a series of uncomfortable tableaus: armies of people marching into cages, strange shockwaves booming across the landscape, twisted forests growing inside great steel structures. And the sound design is just as lonely and unsettling.

But the real devious brilliance of Inside lies in its combination of gameplay and storytelling.

If you’ve played Limbo, the basics of Inside will come as second nature - pull this block along the ground, jump over this gap, hold down this button to move a bit of scenery, and so on. But Inside adds a number of mechanics - deftly taught through guided discovery - that generate fiendish puzzles and pique narrative curiosity in equal measure. Paced in peaks and troughs to avoid repetition and constantly confront the player with new ideas, the puzzles challenge the player’s understanding of how the world works, both physically and psychologically. Many puzzles are the sort of head-scratchers that make you laugh out loud when you work them out. One mechanic - which turns a mid-game episode into a primal exercise in terror - gets brought to a horrifying peak before being neatly inverted in the game’s latter episodes. It’s goddamned smart design.

Inside is a rare game that demands active thought well after the credits roll. It doesn't reward multiple playthroughs mechanically, apart from a handful of hidden secrets and a fourth-wall-breaking alternate ending, but I’d challenge anyone with an ounce of innate curiosity to finish it without immediately wanting to play it again. There’s so much going on in the margins - seriously, so much unthinkably bizarre shit - that fan theories will no doubt proliferate as to the meaning of the game’s story and worldbuilding.

Speculation as to the literal events and phenomena of Inside would miss the point. Its abstract, at times Ghibliesque design defies logic, using dystopian sci-fi and horror ideas to reflect themes and ideas rather than spin a finite tale. Exploring notions of industrial slavery, scientific hubris, institutional control, and the nature of body and self, it invites multiple interpretations and complex emotional responses. Mindless masses, hulking machinery, seemingly endless stygian abysses - it’s all potent imagery of oppression and despair. There’s resistance to authority in the game’s spirit, starting from the protagonist’s opening run from taser-equipped figures and continuing into its desperate, triumphant final moments. But there’s also a sense that nearly everything in your little revolt is pre-ordained. Maybe it’s about the dangers of non-conformity! Whichever way you see it, it’ll make you want to watch other people play, just so you can discuss and argue over its meaning.

And then there’s that final act. At once hilarious, thrilling, sickening, and sad, it made me happier than any game has in recent memory, capping off a brilliant few hours of gameplay. Playdead has built another all-timer with Inside, somehow improving upon perfection through imaginative, stunning, functional design. Though shot through with horror, Inside brings out the kind of joy that reminds me why I play video games. Its particular pleasures could not exist in any other medium. Get inside it as soon as you can.

#inside#inside review#really like how he described certain things#inside is the best game#play it guysss#playdead

9 notes

·

View notes