#adapting a factual book for a novel

Text

How to make a true-life account into a compelling story, or how to make Masters of Sex from Masters of Sex

I thoroughly enjoyed the Channel 4 series Masters of Sex, about Dr William Masters and Virginia Johnson, the pioneers of sexual research in the 1950s and 1960s. I then read the factual book it’s based on by Thomas Maier and was surprised by how different it is. While the drama feels very faithful to the facts, the scriptwriter, Michelle Ashford, has extensively reshaped the material to create a…

View On WordPress

#adapting a factual book for a novel#characters from issues#characters from theme#creating characters#finding your themes#historical fiction#how to write a great story#Masters of Sex#Michelle Ashford#period drama#social issues in fiction#storytelling#Theme#Thomas Maier#Virginia Johnson#William Masters

0 notes

Text

ON GHOSTS AND DEMONS: Wei Wuxian's "demonic" cultivation?

There are a few big misconceptions I have repeatedly seen in English-speaking fandom about things that are fundamental to the story of MDZS. One of them is this—

Wei Wuxian is not a demonic cultivator.

To prove this, let's take a deep dive into the original Chinese text of MDZS.

(Adapted from my original gdoc posted on Twitter on May 27, 2022. All translations my own unless otherwise stated.)

Demon vs. ghost

Let's start from the very basics. In addition to orthodox cultivation using spiritual energy and a golden core, there are two other forms of cultivation that are mentioned in the novel:

魔道 (mó dào), or “demon cultivation/path.”

鬼道 (guǐ dào), or “ghost cultivation/path.”

To be clear, 魔 mo "demons" and 鬼 gui "ghosts" (and thus their respective cultivation/paths) are not interchangeable because of the in-universe worldbuilding within MDZS. Using the characters in the term 妖魔鬼怪 "monsters," MXTX created four distinct categories of beings, each of which has a strict definition in the novel. From chapter 4 (jjwxc ch 13):

妖者非人之活物所化; 魔者生人所化; 鬼者死者所化; 怪者非人之死物所化。

Yāo (妖) are transformed from non-human living beings; mó (魔) are transformed from living people; guǐ (鬼) are transformed from the deceased; guài (怪) are transformed from non-human dead beings.

And of course, WWX hoards all the ghost-type pokemon monsters at the Phoenix Mountain tournament, and he only exerts control over corpses, spirits, and the like (aka people who have already died). (As opposed to Xue Yang, who appears to have been actively trying to make 魔 "demons" out of living people with those "living corpses" of his, perhaps.) (And, ironically, in order to avoid showing necromancy / zombies on screen, CQL technically does show WWX practicing demon cultivation because everyone is "supposedly alive" even when they're corpses? Which is, funnily enough, far worse morally in the MDZS universe, lol.)

So, intuitively at least, we know that WWX must be practicing ghost cultivation—now let's look at some concrete examples from the book.

Running the numbers

1) 魔道 (mó dào) means “demon cultivation.” As such, it must use living humans.

魔道 appears one (1) time in the novel.

Yes, once. The only time it appears is in the term 魔道祖师 modao zushi, or the namesake of the novel, in chapter 2. This is a title the general public has given him through rumors:

魏无羡好歹也被人叫了这么多年无上邪尊啦、魔道祖师啦之类的称号,这种一看就知道不是什么好东西的阵法,他自然了如指掌。

Wei Wuxian wasn’t called titles like “The Evil Overlord,” “The Founder of Demon Cultivation,” and so on over the years by others for nothing—he knew these sorts of obviously shady formations like the back of his hand.

2) 鬼道 (guǐ dào) means “ghost cultivation.” As such, it must use dead humans.

鬼道 appears 12 times in the novel.

Here is the first instance that 鬼道 appears, which I believe is the first time Wei Wuxian's method of cultivation is properly introduced. From chapter 3 (jjwxc ch 8):

蓝忘机 […] 对魏无羡修鬼道一事极不认可。

Lan Wangji […] had never approved of the fact that Wei Wuxian practiced ghost cultivation.

Here's another quote from chapter 15 (jjwxc ch 71) for funsies:

蓝忘机看着他,似乎一眼就看出他只是随口敷衍,吸了一口气,道:“魏婴。”

Lan Wangji looked at him as if he saw through his half-hearted bluff. He took in a breath, then said, “Wei Ying.”

他执拗地道:“鬼道损身,损心性。”

He stubbornly continued, “Ghost cultivation harms one’s body, and harms one’s nature.”

3) 邪魔歪道 (xiemowaidao) means heretical path/immoral methods/evil practices/underhanded means/etc—e.g., lying, cheating, stealing, bribery, and so on.

It appears ~24 times in the novel.

I mention this last term because it is often used to refer to Wei Wuxian's cultivation, but as a pejorative. Every instance of 邪魔歪道 is said by or to quote someone looking down upon Wei Wuxian’s cultivation (Jin Zixun, Jin Ling, etc.) and referring to it derogatorily, whereas every instance of 鬼道 guidao/ghost dao is said by someone discussing it neutrally and/or factually (Lan Jingyi, Lan Wangji, Wei Wuxian himself, random cultivators at discussion conferences, the narration, etc.). Here is a pertinent example with Jin Ling (derogatory) and Lan Jingyi (neutral) in chapter 9 (jjwxc ch 43):

金凌怒道:“是在谈论薛洋,我说的不对吗?薛洋干了什么?他是个禽兽不如的人渣,魏婴比他更让人恶心!什么叫‘不能一概而论’?这种邪魔歪道留在世上就是祸害,就是该统统都杀光,死光,灭绝!”

“We are discussing Xue Yang,” Jin Ling said angrily. “Am I wrong? What did Xue Yang do? He’s scum that’s lower than a beast, and Wei Ying is even more disgusting than him! What do you mean ‘don’t make sweeping generalizations?’ As long as those practicing this kind of demoniac, heretical path are alive, they’ll continue to bring disaster. We should slaughter all of them, kill all of them, annihilate them once and for all!”

温宁动了动,魏无羡摆手示意他静止。只听蓝景仪也加入了,嚷道:“你发这么大火干什么?思追又没说魏无羡不该杀,他只是说修鬼道的也不一定全都是薛洋这种人,你有必要乱摔东西吗?那个我还没吃呢……”

Wen Ning shuffled around. Wei Wuxian gestured at him to stay still, only to hear Lan Jingyi also cut in loudly, “Why are you getting so riled up? It’s not like Sizhui said Wei Wuxian shouldn’t have been killed. All he said was that people who practice ghost cultivation aren’t necessarily all like Xue Yang. Do you have to go around breaking things? I didn’t even get to eat any of that yet…”

Tl;dr—Wei Wuxian does not 修魔道 practice demon cultivation. When Wei Wuxian’s craft is discussed in a neutral and factual manner, it is referred to as 鬼道 ghost dao.

In fact, Wei Wuxian’s imitators are also referred to explicitly as 鬼道修士 ghost cultivators.

魏无羡早就听说过,这些年来江澄到处抓疑似夺舍重生的鬼道修士,把这些人通通押回莲花坞严刑拷打。

Wei Wuxian had heard a while back that over the past few years, Jiang Cheng had gone around snatching any ghost cultivator suspected of being possessed or reborn, detaining them in Lotus Pier to interrogate them using torture.

So why the confusion?

Of course, there is the matter of the novel's title, which I will get into in a second. But the real issue is a matter of translation.

The idea that WWX uses "demonic cultivation" is a misconception in English-speaking fandom due to issues with the translation of terminology. Of note, EXR actually did translate 鬼道 guidao as "ghostly path" most of the time, though there were at least 3 instances of "demonic" and 1 instance of "dark," especially regarding the first few.

However, this misconception was perpetuated (and arguably worsened) by 7S's official translation, which not only mistranslated additional terms as "demonic cultivation/path" (at least in book 1), but also consistently mistranslated every instance of 鬼道 as "demonic cultivation/path."

So why is this book called 魔道祖师, commonly translated as "Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation?"

One possibility is one posed in Chinese-language meta online, which often cites that WWX himself is a sort of 魔 demon. While this may be true—after all, he can hear the voices of the dead—it doesn't quite explain the fact that the title sets him up to be the 祖师 or "founder."

My take is that this novel is very much concerned with hearsay vs. truth. This is one of the many monikers WWX is given by the public, who collectively view him as evil. (Also of note is that the non-cultivator public is not aware of all the nuances that cultivators learn re: distinctions between the 妖魔鬼怪 monsters.) In the quote from earlier, note that the first title we're given is actually 无上邪尊 “The Evil Overlord,” then 魔道祖师 "The Founder of Demon Cultivation." Like, what can that be other than MXTX telling us, "please take both of these with a HUGE grain of salt, lol."

(And not only the title, but the very first line—"魏无羡死了。" / "Wei Wuxian is dead."—is a lie.)

I think the title is genius, honestly. It intentionally makes readers come into the novel with preconceived notions that Wei Wuxian practices 魔道 demon cultivation and evil techniques—just like the public in the novel. What better way to tell a story warning about the dangers of how easy it is to fall for misinformation and jump to incorrect conclusions?

(Though, in our case, perhaps it worked a little too well.)

#魔道祖师#mdzs#mdzs meta#mdzs translation#wei wuxian#wwx#demonic cultivation#ghost cultivation#mine#doufudanshi translation#crossposted from twitter#(sort of)

977 notes

·

View notes

Note

How to write genius level characters? :(

One of the most reliable measures of intelligence today is the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale—currently in its 5th edition, with an upcoming edition in the works.

Using the tool/scale, scores are converted into nominal categories designated by certain cutoff boundaries for quick reference:

Measured IQ Range — Category

145-160: Very gifted or highly advanced

130–144: Gifted or very advanced

120–129: Superior

110–119: High average

90–109: Average

80–89: Low average

70–79: Borderline impaired or delayed

55–69: Mildly impaired or delayed

40–54: Moderately impaired or delayed

To write your "genius" character, you may want them within the Gifted to Very Gifted categories.

Note: With reference to this list, Roid (2003) cautioned that “the important concern is to describe the examinee’s skills and abilities in detail, going beyond the label itself”. The primary value of such labels is as a shorthand reference in some psychological reports.

These are the factors measured by the scale, and you ideally should aim for your "genius" character/s to exhibit high levels of:

Fluid Reasoning: Novel problem solving; understanding of relationships that are not culturally bound

Knowledge: Skills and knowledge acquired by formal and

informal education

Quantitative Reasoning: Knowledge of mathematical thinking including number concepts, estimation, problem solving, and measurement

Visual-Spatial Processing: Ability to see patterns and relationships and spatial orientation as well as the gestalt among diverse visual stimuli

Working Memory: Cognitive process of temporarily storing and then transforming or sorting information in memory

Or maybe your character doesn't excel in all of these areas but in a specific one, or just a few of these. Maybe they perform within the average or high average in some, but are highly gifted in other areas.

The following may also guide you in writing your genius character, based on research compiled by Dr. J. Renzulli, which can be found in the Mensa Gifted Youth Handbook:

Characteristics of Giftedness

LEARNING CHARACTERISTICS

Has unusually advanced vocabulary for age or grade level

Has quick mastery and recall of factual information

Wants to know what makes things or people tick

Usually sees more or gets more out of a story, film, etc., than others

Reads a great deal on his or her own; usually prefers adult-level books; does not avoid difficult materials

Reasons things out for him- or herself

MOTIVATIONAL CHARACTERISTICS

Becomes easily absorbed with and truly involved in certain topics or problems

Is easily bored with routine tasks

Needs little external motivation to follow through in work that initially excited him or her

Strives toward perfection; is self-critical; is not easily satisfied with his or her own speed and products

Prefers to work independently; requires little direction from teachers

Is interested in many "adult" problems such as religion, politics, sex and race

Stubborn in his or her beliefs

Concerned with right and wrong, good and bad

CREATIVITY CHARACTERISTICS

Constantly asking questions about anything and everything

Often offers unusual, unique or clever responses

Is uninhibited in expressions of opinion

Is a high-risk taker; is adventurous and speculative

Is often concerned with adapting, improving and modifying institutions, objects and systems

Displays a keen sense of humor

Shows emotional sensitivity

Is sensitive to beauty

Is nonconforming; accepts disorder; is not interested in details; is individualistic; does not fear being different

Is unwilling to accept authoritarian pronouncements without critical examination

LEADERSHIP CHARACTERISTICS

Carries responsibility well

Is self-confident with children his or her own age as well as adults

Can express him- or herself well

Adapts readily to new situations

Is sociable and prefers not to be alone

Generally directs the activity in which he or she is involved

Sources: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Hope this helps with your writing. Do tag me, or send me a link. I'd love to read your work!

#anonymous#intelligence#psychology#writeblr#character development#writers on tumblr#dark academia#spilled ink#studyblr#literature#writing prompt#poets on tumblr#poetry#character building#character inspiration#original character#creative writing#fiction#writing inspo#writing ideas#writing inspiration#writing reference#writing resources

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Is Tom Ripley gay? For nearly 70 years, the answer has bedeviled readers of Patricia Highsmith’s 1955 thriller The Talented Mr. Ripley, the story of a diffident but ambitious young man who slides into and then brutally ends the life of a wealthy American expatriate, as well as the four sequels she produced fitfully over the following 36 years. It has challenged the directors — French, British, German, Italian, Canadian, American — who have tried to bring Ripley to the screen, including in the latest adaptation by Steven Zaillian, now on Netflix. And it appears even to have flummoxed Ripley’s creator, a lesbian with a complicated relationship to queer sexuality. In a 1988 interview, shortly before she undertook writing the final installment of the series, Ripley Under Water, Highsmith seemed determined to dismiss the possibility. “I don’t think Ripley is gay,” she said — “adamantly,” in the characterization of her interviewer. “He appreciates good looks in other men, that’s true. But he’s married in later books. I’m not saying he’s very strong in the sex department. But he makes it in bed with his wife.”

The question isn’t a minor one. Ripley’s killing of Dickie Greenleaf — the most complicated, and because it’s so murkily motivated, the most deeply rattling of the many murders the character eventually commits — has always felt intertwined with his sexuality. Does Tom kill Dickie because he wants to be Dickie, because he wants what Dickie has, because he loves Dickie, because he knows what Dickie thinks of him, or because he can’t bear the fact that Dickie doesn’t love him? Ordinarily, I’m not a big fan of completely ignoring authorial intent, and I’m inclined to let novelists have the last word on factual information about their own creations. But Highsmith, a cantankerous alcoholic misanthrope who was long past her best days when she made that statement, may have forgotten, or wanted to disown, her own initial portrait of Tom Ripley, which is — especially considering the time in which it was written — perfumed with unmistakable implication.

Consider the case that Highsmith puts forward in The Talented Mr. Ripley. Tom, a single man, lives a hand-to-mouth existence in New York with a male roommate who is, ahem, a window dresser. Before that, he lived with an older man with some money and a controlling streak, a sugar daddy he contemptuously describes as “an old maid”; Tom still has the key to his apartment. Most of his social circle — the names he tosses around when introducing himself to Dickie — are gay men. The aunt who raised him, he bitterly recalls, once said of him, “Sissy! He’s a sissy from the ground up. Just like his father!” Tom, who compulsively rehearses his public interactions and just as compulsively relives his public humiliations, recalls a particularly stinging moment when he was shamed by a friend for a practiced line he liked to use repeatedly at parties: “I can’t make up my mind whether I like men or women, so I’m thinking of giving them both up.” It has “always been good for a laugh, the way he delivered it,” he thinks, while admitting to himself that “there was a lot of truth in it.” Fortunately, Tom has another go-to party trick. Still nurturing vague fantasies of becoming an actor, he knows how to delight a small room with a set of monologues he’s contrived. All of his signature characters are, by the way, women.

This was an extremely specific set of ornamentations for a male character in 1955, a time when homosexuality was beginning to show up with some frequency in novels but almost always as a central problem, menace, or tragedy rather than an incidental characteristic. And it culminates in a gruesome scene that Zaillian’s Ripley replicates to the last detail in the second of its eight episodes: The moment when Dickie, the louche playboy whose luxe permanent-vacation life in the Italian coastal town of Atrani with his girlfriend, Marge, has been infiltrated by Tom, discovers Tom alone in his bedroom, imitating him while dressed in his clothes. It is, in both Highsmith’s and Zaillian’s tellings, as mortifying for Tom as being caught in drag, because essentially it is drag but drag without exaggeration or wit, drag that is simply suffused with a desire either to become or to possess the object of one’s envy and adoration. It repulses Dickie, who takes it as a sexual threat and warns Tom, “I’m not queer,” then adds, lashingly, “Marge thinks you are.” In the novel, Tom reacts by going pale. He hotly denies it but not before feeling faint. “Nobody had ever said it outright to him,” Highsmith writes, “not in this way.” Not a single gay reader in the mid-1950s would have failed to recognize this as the dread of being found out, quickly disguised as the indignity of being misunderstood.

And it seemed to frighten Highsmith herself. In the second novel, Ripley Under Ground, published 15 years later, she backed away from her conception of Tom, leaping several years forward and turning him into a soigné country gentleman living a placid, idyllic life in France with an oblivious wife. None of the sequels approach the cold, challenging terror of the first novel — a challenge that has been met in different ways, each appropriate to their era, by the three filmmakers who have taken on The Talented Mr. Ripley. Zaillian’s ice-cold, diamond-hard Ripley just happens to be the first to deliver a full and uncompromising depiction of one of the most unnerving characters in American crime fiction.

The first Ripley adaptation, René Clément’s French-language drama Purple Noon, is much beloved for its sun-saturated atmosphere of endless indolence and for the tone of alienated ennui that anticipated much of the decade to come; the movie was also a showcase for its Ripley, the preposterously sexy, maddeningly aloof Alain Delon. And therein lies the problem: A Ripley who is preposterously sexy is not a Ripley who has ever had to deal with soul-deep humiliation, and a Ripley who is maddeningly aloof is not going to be able to worm his way into anyone’s life. Purple Noon is not especially willing (or able — it was released in 1960) to explore Ripley’s possible homosexuality. Though the movie itself suggests that no man or woman could fail to find him alluring, what we get with Delon is, in a way, a less complex character type, a gorgeous and magnetic smooth criminal who, as if even France had to succumb to the hoariest dictates of the Hollywood Production Code, gets the punishment due to him by the closing credits. It’s delectable daylit noir, but nothing unsettling lingers.

Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley, released in 1999, is far better; it couldn’t be more different from the current Ripley, but it’s a legitimate reading that proves that Highsmith’s novel is complex and elastic enough to accommodate wildly varying interpretations. A committed Matt Damon makes a startlingly fine Tom Ripley, ingratiating and appealing but always just slightly inept or needy or wrong; Jude Law — peak Jude Law — is such an effortless golden boy that he manages the necessary task of making Damon’s Tom seem a bit dim and dull; and acting-era Gwyneth Paltrow is a spirited and touchingly vulnerable Marge.

Minghella grapples with Tom’s sexual orientation in an intelligently progressive-circa-1999 way; he assumes that Highsmith would have made Tom overtly gay if the culture of 1955 had allowed it, and he runs all the way with the idea. He gives us a Tom Ripley who is clearly, if not in love with Dickie, wildly destabilized by his attraction to him. And in a giant departure from the novel, he elevates a character Highsmith had barely developed, Peter Smith-Kingsley (played by Jack Davenport) into a major one, a man with whom we’re given to understand that Ripley, with two murders behind him and now embarking on a comfortable and well-funded European life, has fallen in love. It doesn’t end well for either of them. A heartsick Tom eventually kills Peter, too, rather than risk discovery — it’s his third murder, one more than in the novel — and we’re meant to take this as the tragedy of his life: That, having come into the one identity that could have made him truly happy (gay man), he will always have to subsume it to the identity he chose in order to get there (murderer). This is nowhere that Highsmith ever would have gone — and that’s fine, since all of these movies are not transcriptions but interpretations. It’s as if Minghella, wandering around inside the palace of the novel, decided to open doors Highsmith had left closed to see what might be behind them. The result is the most touching and sympathetic of Ripleys — and, as a result, far from the most frightening.

Zaillian is not especially interested in courting our sympathy. Working with the magnificent cinematographer Robert Elswit, who makes every black-and-white shot a stunning, tense, precise duel between light and shadow, he turns coastal Italy not into an azure utopia but into a daunting vertical maze, alternately paradise, purgatory, and inferno, in which Tom Ripley is forever struggling; no matter where he turns, he always seems to be at the bottom of yet another flight of stairs.

It’s part of the genius of this Ripley — and a measure of how deeply Zaillian has absorbed the book — that the biggest departures he makes from Highsmith somehow manage to bring his work closer to her scariest implications. There are a number of minor changes, but I want to talk about the big ones, the most striking of which is the aging of both Tom and Dickie. In the novel, they’re both clearly in their 20s — Tom is a young striver patching together an existence as a minor scam artist who steals mail and impersonates a collection agent, bilking guileless suckers out of just enough odd sums for him to get by, and Dickie is a rich man’s son whose father worries that he has extended his post-college jaunt to Europe well past its sowing-wild-oats expiration date. Those plot points all remain in place in the miniseries, but Andrew Scott, who plays Ripley, is 47, and Johnny Flynn, who plays Dickie, is 41; onscreen, they register, respectively, as about 40 and 35.

This changes everything we think we know about the characters from the first moments of episode one. As we watch Ripley in New York, dourly plying his miserable, penny-ante con from a tiny, barren shoe-box apartment that barely has room for a bed as wide as a prison cot (this is not a place to which Ripley has ever brought guests), we learn a lot: This Ripley is not a struggler but a loser. He’s been at this a very long time, and this is as far as he’s gotten. We can see, in an early scene set in a bank, that he’s wearily familiar with almost getting caught. If he ever had dreams, he probably buried them years earlier. And Dickie, as a golden boy, is pretty tarnished himself — he isn’t a wild young man but an already-past-his-prime disappointment, a dilettante living off of Daddy’s money while dabbling in painting (he’s not good at it) and stringing along a girlfriend who’s stuck on him but probably, in her heart, knows he isn’t likely to amount to much.

Making Tom older also allows Zaillian to mount a persuasive argument about his sexuality that hews closely to Highsmith’s vision (if not to her subsequent denial). If the Ripley of 1999 was gay, the Ripley of 2024 is something else: queer, in both the newest and the oldest senses of the word. Scott’s impeccable performance finds a thousand shades of moon-faced blankness in Ripley’s sociopathy, and Elswit’s endlessly inventive lighting of his minimal expressions, his small, ambivalent mouth and high, smooth forehead, often makes him look slightly uncanny, like a Daniel Clowes or Charles Burns drawing. Scott’s Ripley is a man who has to practice every vocal intonation, every smile or quizzical look, every interaction. If he ever had any sexual desire, he seems to have doused it long ago. “Is he queer? I don’t know,” Marge writes in a letter to Dickie (actually to Tom, now impersonating his murder victim). “I don’t think he’s normal enough to have any kind of sex life.” This, too, is from the novel, almost word for word, and Zaillian uses it as a north star. The Ripley he and Scott give us is indeed queer — he’s off, amiss, not quite right, and Marge knows it. (In the novel, she adds, “All right, he may not be queer [meaning gay]. He’s just a nothing, which is worse.”) Ripley’s possible asexuality — or more accurately, his revulsion at any kind of expressed sexuality — makes his killing of Dickie even more horrific because it robs us of lust as a possible explanation. This is the first adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley I’ve seen in which even Ripley may not know why he murders Dickie.

When I heard that Zaillian (who both wrote and directed all of the episodes) was working on a Ripley adaptation, I wondered if he might replace sexual identity, the great unequalizer of 1999, with economic inequity, a more of-the-moment choice. Minghella’s version played with the idea; every person and object and room and vista Damon’s Ripley encountered was so lush and beautiful and gleaming that it became, in some scenes, the story of a man driven mad by having his nose pressed up against the glass that separated him from a world of privilege (and from the people in that world who were openly contemptuous of his gaucheries). Zaillian doesn’t do that — a lucky thing, since the heavily Ripley-influenced film Saltburn played with those very tropes recently and effectively. Whether intentional or not, one side effect of his decision to shoot Ripley in black and white is that it slightly tamps down any temptation to turn Italy into an occasion for wealth porn and in turn to make Tom an eat-the-rich surrogate. This Italy looks gorgeous in its own way, but it’s also a world in which even the most beautiful treasures appear threatened by encroaching dampness or decay or rot. Zaillian gives us a Ripley who wants Dickie’s life of money and nice things and art (though what he’s thinking when he stares at all those Caravaggios is anybody’s guess). But he resists the temptation to make Dickie and Marge disdainful about Tom’s poverty, or mean to the servants, or anything that might make his killing more palatable. This Tom is not a class warrior any more than he’s a victim of the closet or anything else that would make him more explicable in contemporary terms. He’s his own thing — a universe of one.

Anyway, sexuality gives any Ripley adapter more to toy with than money does, and the way Zaillian uses it also plays effectively into another of his intuitive leaps — his decision to present Dickie’s friend and Tom’s instant nemesis Freddie Miles not as an obnoxious loudmouth pest (in Minghella’s movie, he was played superbly by a loutish Philip Seymour Hoffman) but as a frosty, sexually ambiguous, gender-fluid-before-it-was-a-term threat to Tom’s stability, excellently portrayed by Eliot Sumner (Sting’s kid), a nonbinary actor who brings perceptive to-the-manor-born disdain to Freddie’s interactions with Tom. They loathe each other on sight: Freddie instantly clocks Tom as a pathetic poser and possible closet case, and Tom, seeing in Freddie a man who seems to wear androgyny with entitlement and no self-consciousness, registers him as a danger, someone who can see too much, too clearly. This leads, of course, to murder and to a grisly flourish in the scene in which Tom, attempting to get rid of Freddie’s body, walks his upright corpse, his bloodied head hidden under a hat, along a street at night, pretending he’s holding up a drunken friend. When someone approaches, Tom, needing to make his possible alibi work, turns away, slamming his own body into Freddie’s up against a wall and kissing him passionately on the lips. That’s not in Highsmith’s novel, but I imagine it would have gotten at least a dry smile out of her; in Ripley’s eight hours, this necrophiliac interlude is Tom’s sole sexual interaction.

No adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley would work without a couple of macabre jokes like that, and Zaillian serves up some zesty ones, including an appearance by John Malkovich, the reigning king/queen of sexual ambiguity (and himself a past Ripley, in 2002’s Ripley’s Game), nodding to Tom’s future by playing a character who doesn’t show up until book two. He also gives us a witty final twist that suggests that Ripley may not even make it to that sequel, one that reminds us how fragile and easily upended his whole scheme has been. Because Ripley, in this conception, is no mastermind; Zaillian’s most daring and thoughtful move may have been the excision of the word “talented” from the title. In the course of the show, we see him toy with being an editor, a writer (all those letters!), a painter, an art appreciator, and a wealthy man, often convincingly — but always as an impersonation. He gives us a Tom who is fiercely determined but so drained of human affect when he’s not being watched that we come to realize that his only real skill is a knack for concentrating on one thing to the exclusion of everything else. What we watch him get away with may be the first thing in his life he’s really good at (and the last moment of the show suggests that really good may not be good enough). This is not a Tom with a brilliant plan but a Tom who just barely gets away with it, a Tom who can never relax.

Tom’s sexuality is ultimately an enigma that Zaillian chooses to leave unsolved — as it remains at the end of the novel. Highsmith’s decision to turn Tom into a roguish heterosexual with a taste for art fraud before the start of the second novel has never felt entirely persuasive, and it’s clearly a resolution in which Zaillian couldn’t be less interested. Toward the end of Ripley, Tom is asked by a detective to describe the kind of man Dickie was. He transforms Dickie’s suspicion about his queerness into a new narrative, telling the private investigator that Dickie was in love with him: “I told him I found him pathetic and that I wanted nothing more to do with him.” But it’s the crushing verdict he delivers just before that line that will stay with me, a moment in which Tom, almost in a reverie, might well be describing himself: “Everything about him was an act. He knew he was supremely untalented.” In the end, Scott and Zaillian give us a Ripley for an era in which evil is so often meted out by human automatons with even tempers and bland self-justification: He is methodical, ordinary, mild, and terrifying.'

#Andrew Scott#Ripley#Matt Damon#The Talented Mr Ripley#Anthony Minghella#Steven Zaillian#Purple Noon#Alain Delon#Johnny Flynn#Dickie Greenleaf#Peter Smith-Kingsley#Jude Law#Gwyneth Paltrow#Robert Elswit#Caravaggio#Marge Sherwood#Freddie Miles#Philip Seymour Hoffman#Eliot Sumner

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

(Please tell me if I am bothering you with my anons, I promise I'll stop, I just really need to rant to someone who understands T^T)

They came onto my post and started being wrong, at this point it's a matter of pride! (Tho I am this close to just doing that, if they keep saying things so factually wrong T^T)

Thanks for the answer, it really helped! We have since then moved on to debate whether WWX's cultivation harmed and impacted him and how he couldn't control it because of it.

(I disagree, personally, as that is what the public is trying to claim without even understanding how WWX's ghost path works, or how any form of cultivation works. I am of the mind that nobody can use any kind of cultivation safely and in a controlled manner while being pushed to the brink as often as WWX was during that period of his life.)

Frankly, it is pretty entertaining, tho I can't say it's a riveting conversation either. Their answer to me saying that the title of the novel was a dig to WWX's cultivation path that actually subvert the trope of demonic cultivation in xianxia novels was : "No, it is because of how he had good intentions and tried to protect everyone by using bad means to achieve goodness,tho in the end, he did more bad things than good ones." And I am just sitting there, losing braincells, wondering what the heck they are talking about.

Still better than the "Both LWJ and JC spent years looking for WWX's soul after his death, LWJ literally played music everyday to call his soul to him 🙄" thing. Why do I see this so often? Like, did it happen in the book? Am I losing my mind? Genuine question here, I feel like I am losing my mind T^T.

I think that particular fanon originated from a popular fandom blogger—and is usually paired with the headcanon that Lan Wangji only went where the chaos was to “chase Wei Wuxian’s spirit”—but I think I also heard it might have been written into some of the adaptations? (Idk about that second one because I’ve only ever completed the book.) Lan Wangji is said to have “gone where the chaos is” during the war, hence his title being given then, and the Lotus Pod Seeds extra seems to imply that this behavior was inspired by his first solo journey out of The Cloud Recesses to pursue lotus pod seeds upon Wei Wuxian’s suggestion during The Cloud Recesses arc. Nowhere in the book does it say that Lan Wangji played music to calm or call Wei Wuxian’s soul. The only place in the novel where it is ever mentioned that music was played in an attempt to call forth his soul is when the sects gathered together after the first siege of the Burial Mounds and were unsuccessful in their attempt. Lan Wangji was not present for this.

As for whether Wei Wuxian’s cultivation physically harms him or not: if the ghost path was harmful to the body, then 1) Lan Wangji would reject its use and 2) Wei Wuxian would limit his use of it and refuse to showcase it to others. For the first part: while Lan Wangji had many objections to the use of the ghost path during the war, he curbs those objections at the end of Wei Wuxian’s first life and actively supports his usage of it through actions in Wei Wuxian’s second life. For the second part: Wei Wuxian uses the ghost path in his second life throughout the entire main story and continuing into the extras. He completely forgoes using a sword as his main weapon of choice. He even displays his techniques to the juniors and explains how they work, but he begins to curb some of his usage with them to give them a chance to solve nighthunts on their own instead of relying on him to solve issues for them.

#mdzs asks#anon#ah so they jumped onto your post#as they do#looks like you have some spring cleaning to do mayhaps

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cannibalism is considered the most inhumane of activities. In the last year, however, films and TV shows like Bones And All, Fresh, Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, House of Hammer, and Yellowjackets have forced viewers to grapple with the trope by digging into the metaphorical, social and political themes it may represent beyond all that body horror. What they’ve discovered is just how delicious cannibalistic themes can be when digging into capitalism, patriarchy, human connection and autonomy for those at the bottom of the food chain.

In Luca Guadagnino’s Bones and All, based on Camille DeAngelis’s 2015 novel, two cannibal lovers face tragedy. In the final scene, Lee (Timothée Chalamet) is dying from a punctured lung and he’s not willing to let his partner Maren (Taylor Russell) do anything to help save him. Their lives thus far have been defined by marginalisation, abandonment, shame, violence and trauma with only romantic love between the two of them offering any sort of true solace. With his final breaths, Lee urges Maren to eat him, "bones and all." We’re told in an earlier speech it is the ultimate, cathartic cannibalistic feeding experience. And so, through tears and after initial reluctance, she does. Two disenfranchised people finding connection in the most tragic of circumstances.

Now if your takeaway from this ending is that it condones literal cannibalistic love, then screenwriter David Kajganich would like to interject. "If I felt we had somehow pointed an impressionable audience in the direction of ‘this is a beautiful vision of how love should work’ I would have not gotten my laptop out," he tells Mashable. "I think what's important isn't why Maren finally eats Lee, it's why Lee gives up." The teen maneater’s fatal injuries were incurred while killing Sully (Mark Rylance) an elder cannibal. It’s not the first time Lee’s killed; it started with his father’s death and ever since it's been the predominant means by which he secured human flesh to eat. "In his case, the specific trauma of murdering his father is a repeat cycle that even love can't break," says Kajganich. "The ending is less about cannibalism and more about Lee's character deciding, 'I don't want to be here anymore. I don't want to live even for this relationship.'" Living on the outskirts with his trauma, the guilt and the shame of his murderous cannibalistic secret is ultimately too much for Lee to bear.

A nuanced understanding is required when regarding the cannibalism trope employed in the novel and its 2022 screen adaptation, as several other social and cultural themes, such as class and gender, overlap and are presented through this taboo prism. But neither book nor film are alone in this resurgence of cannibalistic narrative exploration. Sebastian Stan raised red flags in Mimi Cave’s 2022 poppy rom-com horror Fresh as a hunky human flesh connoisseur using meat-cutes (spelling intended) to source female bodies to the highest bidder. Factual television series like House of Hammer and true crime drama Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story have been readily consumed by audiences with a taste for sordid exploitation. But, as audiences, are we missing the memo that directors are trying to send us through this series and movies?

Eat the rich

There’s something of the American Psycho about House of Hammer, which details not just actor Armie Hammer’s public downfall – following allegations of sexual abuse. The documentary examines Hammer's expression of cannibalistic fantasies in DMs and shows a backdrop of context by also looking at the alleged criminal legacy left by the powerful men in his super wealthy family. Patrick Bateman, the eponymous psycho in Bret Easton Ellis’ 1991 book and Mary Harron’s 2000 film adaptation, like Hammer, has the power, the wealth, the looks, and the cis white male privilege to have whatever he wants – so why not human flesh too? He’s the ultimate consumer but the bodies of his victims tell a bigger story about his immorality. "When Bateman’s seeking the service of sex workers they think it’s for sex that they're going to provide but he ends up cannibalising them," says Mary Wild, Freudian psychoanalyst, cinephile, and co-host of The Projections Podcast. "What he's lacking is humanity. He sees it in people just trying to make a living and he needs to take that away from them." In these contexts, cannibalism runs parallel to extreme wealth and privilege within a capitalist system, in which wealth often comes at the expense and exploitation of other less privileged humans.

"But it is important to differentiate those who have cannibalistic sexual fantasies and those who literally act on. Although these two sometimes intersect, this seems to be the exception and not the rule," says Victoria Hartmann, Ph.D., an extreme pornography and paraphilia researcher and executive director at Erotic Heritage Museum Las Vegas. "I strongly believe it remains vital to carefully consider the chasm between those who are disordered in such a way they would cause harm to another human being in real life without a shred of empathy, and those who have unusual (which can also be considered extreme) sexual interests."

Texts attributed to Hammer suggest he has been "kink-shamed" for his sexual fetish which is commonly known as vorarephilia (vore). Vore is characterised as "the erotic desire to consume or be consumed by another person or creature," specifically being swallowed or swallowing someone whole which is a tad different to the allegations against Hammer. Many of the women claim they were coerced and manipulated into his so-called vore situations which left them feeling physically and emotionally damaged. In the vast majority of cases – because eating people is a horrific crime, of course – vorarephiles, whether they imagine themselves as predator or prey, mostly enjoy this kink in a fantasy realm reinforced through images, texts or video games shared online through websites like Eka’s Portal. "Research continues to indicate, and this has been reproduced in study after study (including my own studies from 2012-2014), that paraphilias (also known as fetishes) are not usually indicators of abusive tendencies," adds Hartmann.

For some, however, the focus on cannibalism in this conversation says a lot about our social acceptance of certain heinous acts compared to others. "Sexuality scares us; it is a place where we as human beings are deeply vulnerable, both physically and emotionally," Hartmann tells Mashable. "Now add to that something of an ‘extreme’ nature (such as a cannibalism kink) and this creates even more fear — both existential and real….we are forced to ask ourselves why some people would be drawn to the idea of sexualising death, it’s process and its aftermath."

Death has never been an easy discussion topic let alone when overlapped with desire – unless vampires are thrown into the mix. "Most people cannot fathom even for a moment how those two could ever come together," says Hartmann. It’s disturbing and disgusting and yet, no less harrowing than assault, abuse and sexual violence, which is far more commonplace and continues to be. "We only have to look at the low incidence of convictions for these very real crimes to understand how little value we give to survivors of these forms of violence," she adds. And certainly in the case of Armie Hammer, those accusations were deemed less shocking than the claims relating to cannibalism.

What’s important to remember, says Hartmann, is that a person's cannibalistic desires may not be the root cause for their "impetus to harm others in a non-consensual manner." "Generally, it stems from a co-morbid set of personality disorders; it’s just that some happen to have a co-existing paraphilia(s)."

Consumptive love and desire

The serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer is a prime example of this sort of overlap. In the opening episode of Ryan Murphy’s Dahmer series, starring Evan Peters as the titular serial killer, he rests his head on the bare chest of Tracy Edwards (Shaun J. Brown), the man he has lured to his apartment in order to murder. "I wanna hear your heart," Jeff tells the scared Tracy as he pushes him back on a bloodstained bed, strokes his chest and breathes heavily. "'Cause I’m gonna eat it."

After Tracy’s escape and the serial killer’s arrest, we learn that he had been murdering, carving up and eating his victims while keeping some bones as keepsakes – a habit psychologically influenced by the perceived abandonment by his mother. This could be seen as a way of preventing his victims of "love" from ever truly leaving.

"Cannibalism is the consumption of someone else so, as a Freudian psychoanalyst, I see that as a longing for intimacy, a longing for psychological or emotional closeness, that is actually taking the form of a physical reunion or keeping that person as close to you as possible," says Wild. "Physical intimacy in terms of intercourse, that's not going to do it. You actually need to ingest them, you need to metabolise that person."

In fictional works the cannibal trope can provide fertile metaphorical ground to explore consumptive behaviours involving romance, intimacy and desire, especially for female writers and/or female characters, as with Fresh and Bones and All. "The mere concept of pleasure, especially tied to feminine pleasure, has been considered taboo or worthy of derision, not just in art but society in general," says Kayleigh Donaldson, critic and pop culture writer for Pajiba. "In its most basic form, romantic fiction can be a great way to bust those taboos and dig deeper into our desires. It's a safe space, so to speak, and genre fiction can be a great way to dissect those trickier areas, if it's done well."

Cannibalism in this context can be seen as an expression of female desire and autonomy in a patriarchal world that suppresses and oppresses. "We're taught to walk this literal and figurative thin line of femininity," Chelsea G. Summer, author of cannibalistic body horror novel A Certain Hunger, tells Mashable. "You have to be desirable, but not too desiring. It’s a test that female humans are set up to fail."

Unrealistic feminine standards continue to cause body image issues and eating disorders for women and girls. While not solely female conditions, female cannibal characters like Bones and All’s Maren can provide a "diagnostic criteria," says Wild. "It’s a type of eating that is done in secret, that is shunned by the rest of society and that's seen as abnormal, or, taboo, or sinister. It's representing on a screen this total, emotional spiralling and falling into an eating habit that is shameful. And cannibals themselves will express shame."

Outsiders in a discriminatory world

The desire for self-expression in a still discriminatory world has meant cannibal stories — like Raw, Yellowjackets, and Hannibal — have also been embraced by members of the queer and LGBTQ community. Not in the Dahmer sense of a gay man who racially fetishized many of his gay victims. But in the keen sense of disenfranchisement and societal shame where cannibalism is a substitute for a marginalised queer identity. "It isn't hard to imagine anyone in the LGBTQ community who has ever felt targeted intuitively understanding this metaphor," Kajganich adds. "Cannibalism is such a taboo of the civilized world, such an emblem of what is considered immoral and contemptible outside of holy communion, of course."

"Horror is often such an amplification of everyday anxieties. Why shouldn't those two things combine for those of us in the LGBTQ community as a great language for expressing how it feels when your completely natural way of being intimate is judged as morally violent and socially destructive?"

And yet, when writers, artists or filmmakers employ such cannibalistic themes, characterisations or narratives, an angry online mob is sure to follow. From right-wing groups to QAnon conspiracy theorists, pro-cannibalism accusations have been levied at varied marginalised creators and groups to justify discrimination and fascist politics. And it’s nothing new. "Cannibalism is a charge deployed by colonising people throughout the globe throughout history," Summers points out. "When [Christopher] Columbus hit the Americas he said [the indigenous people were] cannibals therefore we need to change that."

"Now there's this whole network of far right fascist media saying things like, ‘The New York Times is promoting cannibalism, this author is saying everybody should be cannibals and that is why we need to assume control of the West.' It is a fascistic way of implementing control. Cannibalism is the thing we hold up for being inhuman; not murder, not rape, and certainly not colonising. It's cannibalism."

Cannibalism in film and TV is proving to be a nourishing narrative tool to embrace and exemplify the disenfranchised. As well as forcing readers and viewers to negotiate their own awareness and sensitives to morally-challenging stories that don’t serve up clear answers on a platter. "If the element of cannibalism in the film isn't testing your empathy with the characters," adds Kajganich. "If it isn't forcing you to continue to re-up your contract with them in terms of just being open to their lives, then we failed, right?"

And that’s the power of this storytelling tool. By using cannibalism to ask questions of societal power structures, the patriarchy as well as the shame and fear associated with marginalised identity, it forces the audience to seek answers inside themselves. Is cannibalism the problem – or are we? Food for thought.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

This particular evening I find myself deeply immersed in a book series I have discovered called The Magic Treehouse. It chronicles a pair of siblings exploring fictional and historical settings through the literal magic of reading; these settings are all sourced from Earth events and media, and while I have learned much of factual basis regarding these from my patron and grimoire, the colorful descriptions and wide-eyed but safely fictional character perspectives of this firsthand experience are very appealing to mentally picture. I have discovered it is a very long series, continued after the author’s death by close family, and while I am uncertain of these alternatively penned later volumes, I intend to read the entirety of the collection. There are 38 volumes, and graphic novel adaptations. I am quite excited for the opportunity to enact this “binge reading session”. :)

#Though I suppose I will have to interrupt it with sleep rather soon.#How unfortunate.#Perhaps I should amend that soon.#Endless Watcher (ic)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m so sorry I don’t mean to contribute to discourse when it’s already so toxic--people are allowed to be upset with what happened in ep 5 and even to drop the series entirely if they don’t like where it’s going--but I keep seeing even the most well-informed people saying Louis and Lestat have never had more than a minor/brief physical altercation and that’s factually untrue. In fact, I think I can pinpoint the exact scene from the book that this was supposed to be an adaptation of (bear with me):

I cannot tell you all that happened then. I cannot possibly recount it as it was. I remember heaving the lamp at Lestat; it smashed at his feet and the flames rose at once from the carpet. I had a torch then in my hands, a great tangle of sheet I’d pulled from the couch and ignited in the flames. But I was struggling with him before that, kicking and driving savagely at his great strength. And somewhere in the background were Claudia’s panicked screams. And the drapes of the windows blazed. I remember that his clothes reeked of kerosene and that he was at one point smacking wildly at the flames. He was clumsy, sick, unable to keep his balance; but when he had me in his grip, I even tore at his fingers with my teeth to get him off. [...] I remember rolling over and over with Lestat in the flames, feeling the suffocating heat in my face, seeing the flames above his back when I rolled under him. [Claudia attacks Lestat with a poker to help Louis escape his grip.]

What happened next then is not clear to me. I think I grabbed the poker from her and gave him one fine blow with it to the side of the head. I remember that he seemed unstoppable, invulnerable to the blows.

Now, GRANTED, this scene is supposed to take place AFTER the attempted murder, and maybe someone could argue that swamp!Lestat is not in his right mind here, but the fact remains that they do have a brutal fight that involves some pretty extreme violence. We don’t get any description of how injured Louis is afterward besides “scorched and aching” before it skips ahead, but as Lestat himself says one whole novel later: “Read between the lines.”

Is it more fucked up for Lestat to attack Louis the way he does in the show, without the prior provocation of an attempt on his life? UNDOUBTEDLY. OBVIOUSLY. YES. But him returning to the house and ambushing Louis and Claudia as he does in the book (it’s true Lestat doesn’t touch Claudia himself, but he doesn’t stop Antoine from attacking her) doesn’t exactly make him innocent, either.

Maybe I’m wrong and there’ll be an even BIGGER, even MORE VIOLENT scene after they try to kill him and he comes back in the show, but right now I’m assuming they just rearranged things so that this scene happened earlier. Whether that decision was a good one remains to be seen, and I’ll leave it at that for this post.

But yeah. TL;DR - saying Lestat and Louis have NO extremely violent fights in the book is untrue, though the one time it does happen is supposed to be later in the story. It’s still fucked up. Please be kind to people who don’t want to engage with the subject matter, regardless.

#IwtV#domestic violence/#this might have been pointed out by someone else by now but so far I've only seen the Lestat-breaking-through-the-window scene mentioned#which is a lot less harrowing from Louis' description#whereas with this one he outright says ''I don't even know exactly what happened'' because it was so traumatizing for him#EDIT: and yes I know the power imbalance is way higher in the show version and that's its own issue that makes it worse as well#my point isn't that the scene in the show isn't FAR worse; my point was just that I haven't seen this book scene acknowledged

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

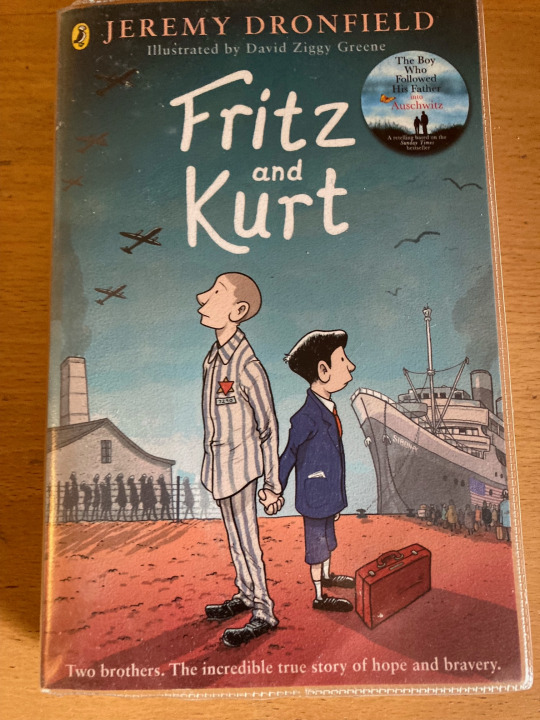

82. Fritz and Kurt, by Jeremy Dronfield

Owned: No, library

Page count: 363

My summary: The true story of Fritz and Kurt Kleinmann, two Jewish children living in Vienna on the eve of World War Two. While Kurt is sent to relatives in America, Fritz and his father are sent through a series of concentration camps and made to suffer the most extreme inhumanity of the Nazi regime.

My rating: 4/5

My commentary:

I picked this book up while I was tidying in the junior non-fiction section at work. It intrigued me when I had a quick leaf through - the story was factual, but presented almost as a novel, and the writing style seemed interesting. Obviously, when you're writing about the Holocaust for younger readers, you are going to want to...not dumb it down, but make the language and concepts accessible and appropriate for that age group. Which I think this author did very well! He explains concepts that kids might not be familiar with, puts the whole thing in language that children can understand, and doesn't compromise on showing just how horrific the Holocaust was for those who had to live through it. I'd totally show this to a kid to teach them about the Holocaust, it explained its story very well.

This book is the children's version of his retelling of the same story for adults, The Boy Who Followed His Father Into Auschwitz - he actually speaks for a moment in the afterword about some of the stylistic changes made. Specifically, in the adults version, he only includes dialogue where he has primary sources on what was said, such as Fritz and Kurt's recollections of events. For this one, he includes some speculative dialogue based on scenes that happened, but that there isn't evidence of what might have been said at the time. He's also invented pseudonyms for people when their names are not known, and shown incidents that it can be reasonably assumed actually occurred, even if there isn't a primary source for it. What's interesting is that he tells us this in the afterword, so he's also introducing kids to the idea of how exactly history is told, and the ways that real events can be adapted into prose.

The story, of course, is heartbreaking, as any tale of the Holocaust would be. Fritz and Kurt, two Jewish boys from Vienna, are torn apart from their families by the Nazi invasion. Fritz and his father are imprisoned in a set of concentration camps, Kurt is sent to America to save his life, their older sister goes to England to work, and their mother and younger sister remain in Vienna. Incredibly, Fritz and his father survive the war, though they're in an absolutely terrible state. Their mother and sister are sent away and murdered. Kurt forgot how to speak German and remained in America, but was reunited with his family. The things that Fritz and his father went through were absolutely horrible - they were beaten, abused, humiliated, degraded, lost friends and family, and had to survive no matter what. Fritz actually managed to escape the death march, only to be arrested and re-enter the system as an Aryan political prisoner. And all of this is told in a pretty stark, matter-of-fact manner that is both understandable to its target audience and does not erase the inhumanity of the Nazi regime. It's a really interesting book, and now I want to read the adult version, just to contrast the two.

Next, another tale of horrible things happening to children, albeit thankfully fictional.

#Fritz and Kurt#Jeremy Dronfield#bookblr#bookblogger#book blog#4#nazism /#antisemitism /#holocaust /

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t write a lot of articles, however, I am in the process of writing a novel about 2 young boys, a ships boy who serves on HMS Victory and a cadet at a Naval Academy in Portsmouth, due to both of them going through a traumatic event and being connected through time by an old naval dirk, their consciousness’s pass to one another leading to them both ending up out of their time. The story revolves around how they as individuals adapt too their surroundings, how their friends, teachers, officers and family cope with the sudden changes in these two characters, who remain unchanged physically. The knowledge that both of them carry and how it directly affects the people they know or interact with over the coming months and the peril it places them both in.

Now I’m in a bit of a dilemma at the moment, I have stuck to the physical characteristics and personality traits of the people I know and upon whom i’ve based my characters on, however, with the exception of the crew of the Victory, which was multi cultural and consisted of men and boys of many different nationalities, i haven’t included any people of a different skin tone then me. It wasn’t a conscious decision, it was just based around the people i have met over time and I thought might bring colour of a different kind because of their character.

Here’s my concern, I have had to really focus on events of the Victory’s Log’s, News Paper reports from the time, Relevant historical records and research, to ensure the book isn’t criticised for being factual incorrect by the people who love historic naval novels which are based on actual events, hence in many ways my characters choose themselves. In saying that, in the modern character’s path as a cadet in Portsmouth, I have not defined many of the physical characteristic’s of the adults he interacts with, with the exception of their gender (Male/Female) they are not defined, so if this gets published, there is room for people to assign there own thoughts to them. They are by no means bland, but it is their actions that define them, not the colour of their skin, hence to me this is the focal point. His friends are described in detail, however, one of whom I’ve based on Squirrel from Cursed and all his nuances, he just fits.

I’m concerned I may be criticised, because i have not been inclusive enough, not addressed gender issues..etc, however, this is my story, my novel, should I be governed by the need to conform, or should I just keep the characters as they are? Historically relevant to the period and the location and let their personal attributes, traits, character and how they speak and treat others lead you to your own conclusions about them?

I’d really like to know your thoughts.. stick to my guns.. or not?

#hms victory#battle of Trafalgar#Horatio Nelson#Novel#Ships Boys#Royal Navy#Book#Master and Commander#Jack Aubrey#Horatio Hornblower#Napoleonic#Inclusiveness#author#woke

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Memory

The topic of memory has always intrigued me the most. I am very curious to know how our brain is able to store events, dating many years back. And in other times, why do we tend to recollect some incident which had occurred to us in a special way or at a specific event. Furthermore, Why don't we remember just everything from our past are some of the questions I have regarding our memory.

The following discussion is regarding the various aspects of a human memory. What exactly is a memory? How much do we know about the processes that a human brain executes to store and retrieve a memory?

Daniel Schacter is a cognitive psychologist and is professor of psychology at Harvard University. His research explores the relation between conscious and unconscious forms of memory, the nature of memory distortions, how we use memory to imagine possible future events, and the effects of aging on memory.

He emphasis about the two types of memories which are , conscious memory or explicit memory which is recollection of factual information, previous experiences and true concepts. Other one is implicit memory which does not require the conscious or explicit recollection of past events or information and the individual is unaware that remembering has occurred.

He has published books like, Searching for memory and 7 deadly sins of memory.

The 7 deadly sins of memory according to him are as follows:

1. Transience

Transience means the influence from one memory on another one. And that memories are subject of forgetting over a period of time.

2. Absentmindedness

Absentmindedness means here that the person's attention is focussed on something different

3. Blocking

Blocking is where memory is available, when we try to remember but can't caught up with the memory with time. And we usually tend to remember it all of a sudden.

4. Misattribution

Remembering some action but misinterpreting the context.

5. Suggestibility

Where memory is corrupted by misunderstandings.

6. Bias

Occurs when current feelings and worldview distort remembrance of past events.

7. Persistence

Cases when we are traumatized by bad memories which we can't get rid off.

Memory plays an important role in everyday life but does not provide an exact and unchanging record of experience: research has documented that memory is a constructive process that is subject to a variety of errors and distortions. Yet these memory “sins” also reflect the operation of adaptive aspects of memory. Memory can thus be characterized as an adaptive constructive process, which plays a functional role in cognition but produces distortions, errors, or illusions as a consequence of doing so. The key aspect of memory is that it's not just for recollecting the past, but also to look ahead at the future.

“We as humans inherently use past scenarios to imagine possible future scenarios by taking flexible pieces of the past and combining them to create novel ideas for the future.” Dr. Daniel Schacter

Memory is fragile because we are subject to forgetting and memory is not always as accurate as we would like to believe. Memory is powerful because most of the time it serves us well, forming the foundation of our knowledge of the world and of ourselves. In the case of emotionally experiences, memory is a source of tremendous power in our lives.'

https://www.psichi.org/page/191EyeFall14cCannon#.YzY44cYo8zY

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard Ellef Ayoade (born June 12, 1977) in Whipp’s Cross, London. He will become

an actor, comedian, writer, director, and television presenter. He is known for his role as the socially awkward IT technician Maurice Moss in the sitcom The IT Crowd, for which he won the BAFTA for Best Male Comedy Performance. He will serve as the president of Footlights at St Catharine’s College. He and Matthew Holness will debut their respective characters Dean Learner and Garth Marenghi at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, bringing the characters to television with Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace and Man to Man with Dean Learner. He will appear in the comedy shows, The Mighty Boosh and Nathan Barley, before gaining exposure and recognition for his role in The IT Crowd. After directing music videos for Arctic Monkeys, Vampire Weekend, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and Kasabian, he will write and direct the comedy-drama film Submarine, an adaptation of the novel by Joe Dunthorne. He will co-star in The Watch and his second film, the Black comedy The Double, premiered, drawing inspiration from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novella of the same title. He will appear on panel shows, most prominently on The Big Fat Quiz of the Year, and serve as a team captain on Was It Something I Said? He will present the factual shows Gadget Man, its spin-off Travel Man and the revival of The Crystal Maze. He will provide his voice to several animated projects, including the films, The Boxtrolls, and Early Man, and the television shows Strange Hill High and Apple & Onion. He will write two comedic books centering on film, “Ayoade on Ayoade: A Cinematic Odyssey” and “The Grip of Film”. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

Text-Talk Novels: A Genre for the Social Media Generation.

What are Text-Talk Novels?

Text-talk novels are novels where the story is told through dialogues on social networks, such as blogs, emails, instant messages, or text messages. Text-talk novels use short sentences and colloquial language, and often include emoticons, abbreviations, and slang. Text-talk novels are also known as blog novels, email novels, IM novels, or SMS novels.

How did Text-Talk Novels emerge and evolve?

Text-talk novels emerged and evolved in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, influenced by various factors, such as the development of the internet, which enabled global and collaborative creation and dissemination of content; the rise of social media, which increased the popularity and accessibility of online communication and networking; and the emergence of new literary movements, such as digital fiction, which used literary styles and techniques to create factually accurate narratives. Text-talk novels also adapted and incorporated elements from other forms of art and entertainment, such as literature, cinema, photography, and podcasts.

What are the characteristics and themes of Text-Talk Novels?

Text-talk novels are characterized by their use of dialogues and social networks, which create a sense of realism, intimacy, and immediacy. Text-talk novels often break the conventional boundaries of literature, such as linearity, structure, and form. Text-talk novels allow the reader to explore multiple paths and meanings, and to participate in the creation and interpretation of the story. Text-talk novels also challenge the notions of authorship, authority, and authenticity, as the story can be influenced by the perspective, voice, and style of the writer or narrator.

Some of the common themes of text-talk novels are:

The relationship between language and reality.

The impact of digital culture on identity and society.

The exploration of new forms of expression and communication.

The critique of the limitations and possibilities of the medium.

The celebration of creativity and innovation.

What are some notable examples of Text-Talk Novels?

There are many examples of text-talk novels that have been acclaimed, awarded, or exhibited in various platforms and venues. Here are some of them:

e (2000) by Matt Beaumont: A comedy novel that tells the story of a dysfunctional advertising agency through a series of emails. It is a satire of the corporate culture and the advertising industry.

ttyl (2004) by Lauren Myracle: A young adult novel that tells the story of three teenage girls and their friendship through a series of instant messages. It is the first book in the Internet Girls series.

The Breakup Diaries (2007) by Maya O. Calica: A romance novel that tells the story of a woman who tries to cope with her breakup through a blog. It is a humorous and relatable story of love and life.

The Boy Next Door (2002) by Meg Cabot: A mystery novel that tells the story of a woman who falls in love with her neighbor who is suspected of murder through a series of emails. It is the first book in the Boy series.

The Princess Diaries (2000) by Meg Cabot: A diary novel that tells the story of Mia Thermopolis, a teenage girl who discovers that she is the heir to the throne of a fictional European country. It is the first book in the Princess Diaries series.

Conclusion.

Text-talk novels are a genre that reflects the realities and potentials of the social media age. They offer new ways of experiencing and creating stories, as well as new perspectives on the role and function of literature in the contemporary world. Text-talk novels are not a trivial or superficial genre, but a valid and valuable form of literature that deserves attention and appreciation.

0 notes

Text

The enduring influence of "Watchmen".

Stories set in an alternate history or reality are built from a "point of divergence," a moment at which the fictional reality veers off from our own. Germany wins World War II, Kennedy survives the assassination attempt, etc. In Watchmen that point comes in 1938. Shortly after the publication of Action Comics #1, costumed heroes begin appearing in the real world, the "factual black and white of the headlines," as Hollis Mason puts it, and history changes course.

In our reality, comics books experienced their own point of divergence on June 5, 1986, with the debut of the first issue of Watchmen by Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and John Higgins. Ever since then, the entire medium has been permanently altered by its startling vision and precise execution.

Watchmen has been referred to as "the Citizen Kane of comics," the greatest comic book or graphic novel of all time, one of the 100 best novels of the 20th century, and so on, with everyone from lowly teenage comics nerds to serious literary critics and academics bestowing more imaginary titles upon it year after year. Reading it is practically a coming-of-age experience for discerning superhero comic readers. It's beyond required reading; it's a ubiquity. The Beatles. Oxygen.

Originally planning to use Charlton characters, Moore and Dave Gibbons created their own analogues, and over the course of twelve issues the pair applied the gravity of the real world to the soaring personifications of ideals, and completely dismantled the concept of the superhero with appalling violence.

And that was the ultimate impression that Watchmen left on most readers. Not the remarkable level of craft and invention exhibited by both Gibbons and Moore; not structure or allegory, or the use of symbolism and motif. It was the dark, cynical treatment of superheroes that truly embedded Watchmen in the consciousness. With Watchmen's incredible success and mainstream media presence, the comics industry naturally had to adapt to take advantage of a new public awareness, and the best way to do that --- or the easiest way, at least --- was with more darkness and cynicism.

In a short time, most superhero comics looked more like Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns. The real world edged its way further into four-color universes, and superheroes became more psychologically complex, violent, and morally relative. Spider-Man villain Kraven the Hunter committed suicide; Superman killed General Zod and his fellow Kryptonians. Even the fans got in on the act, phoning-in to demand the murder of Jason Todd.

Superhero comics became progressively darker and the overall quality of the genre suffered, as one title after another offered more of the same: a poor impression of the most superficial elements of Watchmen. The book had a nuclear impact, immediately sending shockwaves throughout the medium and leaving us with years of fallout. The "grim and gritty" movement dominated the marketplace, and darkness and mediocrity reigned.

Right?

Well, half-right. Moore has repeatedly expressed the opinion that he spawned a wave of imitators, and he's not incorrect, but it's objectively much more nuanced than that. Comics as a whole were undergoing a period of creative growth before Watchmen came along: the boom in independent publishing brought scores of daring new options to readers; both DC and Marvel were experimenting with unconventional projects like Frank Miller's Ronin and the Epic line; and before Moore even made his American debut, the writing in superhero comics was maturing at a rapid pace.

Comics were already headed in bold new directions; Watchmen just came along and set a more precise course. The popularity of the title provided publishers and editors with the motivation to take more risks, open up the talent pools, and release more daring material, and in the years immediately following its success, the creative growth that the medium was already experiencing went into overdrive.

Before the industry went full grim and gritty, the late '80s/early '90s was the most exciting period in comics since the 1960s. And Alan Moore is right: there are plenty of bad impressions of Watchmen. What he forgets are all the great comics that are nothing like it that still might have been published because of it

Just as each generation of readers discovers it, every generation of creators since Watchmen have been influenced by it, and Watchmen continues to have a palpable impact on comics. Is it the greatest comic of all time? Ah, no. It's not even the best Alan Moore comic of all time. But despite its flaws, despite being so misunderstood by so many for so long, it is so apparently brilliant that it will likely never go away.

It has inspired greatness and mediocrity alike, and probably will for as long as comics are published. As we all know, nothing ever ends.

0 notes

Text

Shackleton Graphic Novels

When people – especially Americans, for some reason – find out I'm devoting my career to retelling the Terra Nova Expedition in graphic novel form, often their first response is "Are you going to do Shackleton next?" I am not, for a variety of reasons including the human lifespan being finite, but another reason is that there is already a selection of Shackleton graphic novels on the market. I presume these people don't know about them, so for their benefit, and perhaps yours, here are the ones I'm aware of:

Nick Bertozzi's Shackleton: Antarctic Odyssey - A solid and accessible YA adaptation of the Endurance story, all in one slim quick read.

Sur les bords du monde: l'Odyssée de Sir Ernest Shackleton (Malaterre/Henry/Richez/Frasier) - Tout en français (ou espagnol), mais bien sûr il suit que les dessins sont très beaux. Deux livres: 1 - jusq'à l'entrappement de l'Endurance dans la glace, 2 - à sûreté.

Endurance (Bertho/Boidin) – aussi en français, mais seulement un livre, donc l'histoire passe plus vite que Sur les bords du monde. Aussi des dessins excellents.

Shackleton: The Journey of the James Caird (McCumiskey/ Butler) - 96pp, middle grades, from a pair of Irish comics makers. TBH I just discovered this one, can't tell you more about it!

William Grill's Shackleton's Journey - Falls somewhere between picture book and graphic novel, but it's both factually accurate and artistically beautiful, and can be appreciated by small children and serious adults alike, if perhaps in different ways.

And for a different perspective on the story:

La Isla Elefante is the story of the Uruguayans who tried to rescue Shackleton and his men off Elephant Island. In Spanish (because Uruguay) but a great reminder that there were more people involved in the story!

You may have noticed that all of these are retellings of the Endurance story, specifically the Shackleton/James Caird thread. If you have a hankering to make a Shackleton graphic novel, and are dismayed by the competition, the good news is, there's a lot still open to you. The whole Nimrod expedition, for example! Tell the Discovery story from his point of view! What about the men who stayed on Elephant Island while the South Georgia party was away? Or – heaven forbid – tell us about the Ross Sea Party, the other half of the Endurance story, who suffered such wretchedness as to put the Worst Journey in the World in the shade, but actually achieved what they set out to do?

#graphic novels#comics#history comics#polar exploration#heroic age of polar exploration#antarctica#shackleton#endurance#shackleton 100#graphic storytelling

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blood and Blue Diamonds: Foreword

I started writing an Arcane film noir AU because I wanted to have fun after an angsty Jayvik divorce story by imagining Jayce and Viktor in nice suits, and now I’m writing meta on historically accurate prejudice in fanfiction. Nice going on that one. But here we are.