#afong us

Text

This is the introduction to the wikipedia page about Afong Moy.

The entire page goes about this way, describing her as remarkably in control, as famous, as not at all abused, as completely autonomous. The tone is also neutral to positive. I think I'm just a little bothered because, correct me if I'm wrong because I haven't done too much in depth research, none of the other sources I've read have any suggestion that the situation was so totally consensual. I just find it doubtful she would be so willing to do a display where she constantly had to bare her bound feet to a crowd and then to invasive physical checks. And even if it was consensual, the ghoulishness of the way she was presented and used and spoken of is completely glossed over, the way she was at once fetishized and seen as just another one of the exotic objects in the room, wholly dehumanized as a spectacle. Like, the announcements didn't announce her so innocently as having strange languages and customs, they called her an object, her very skin and body was on display. The page might as well have called her the first asian american #girlboss with how they choose to describe it, it just seems weird to me.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Epic Stories: 2022 picks to check out

The Many Daughters of Afong Moy by Jamie Ford

Dorothy Moy breaks her own heart for a living.

As Washington’s former poet laureate, that’s how she describes channeling her dissociative episodes and mental health struggles into her art. But when her five-year-old daughter exhibits similar behavior and begins remembering things from the lives of their ancestors, Dorothy believes the past has truly come to haunt her. Fearing that her child is predestined to endure the same debilitating depression that has marked her own life, Dorothy seeks radical help.

Through an experimental treatment designed to mitigate inherited trauma, Dorothy intimately connects with past generations of women in her family: Faye Moy, a nurse in China serving with the Flying Tigers; Zoe Moy, a student in England at a famous school with no rules; Lai King Moy, a girl quarantined in San Francisco during a plague epidemic; Greta Moy, a tech executive with a unique dating app; and Afong Moy, the first Chinese woman to set foot in America.

As painful recollections affect her present life, Dorothy discovers that trauma isn’t the only thing she’s inherited. A stranger is searching for her in each time period. A stranger who’s loved her through all of her genetic memories. Dorothy endeavors to break the cycle of pain and abandonment, to finally find peace for her daughter, and gain the love that has long been waiting, knowing she may pay the ultimate price.

Small World by Jonathan Evison

Set against such iconic backdrops as the California gold rush, the development of the transcontinental railroad, and a speeding train of modern-day strangers forced together by fate, it is a grand entertainment that asks big questions.

The characters of Small World connect in the most intriguing and meaningful ways, winning, breaking, and winning our hearts again. In exploring the passengers' lives and those of their ancestors more than a century before, Small World chronicles 170 years of American nation-building from numerous points of view across place and time. And it does it with a fullhearted, full-throttle pace that asks on the most human, intimate scale whether it is truly possible to meet, and survive, the choices posed--and forced--by the age.

The result is a historical epic with a Dickensian flair, a grand entertainment that asks whether our nation has made good on its promises. It dazzles as its characters come to connect with one another through time. And it hits home as it probes at our country's injustices, big and small, straight through to its deeply satisfying final words.

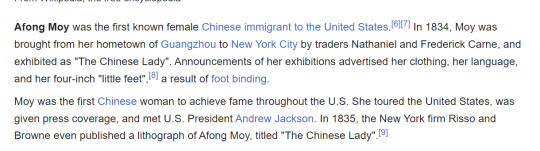

Scorpica by G.R. Macallister

Five hundred years of peace between queendoms shatters when girls inexplicably stop being born. As the Drought of Girls stretches across a generation, it sets off a cascade of political and personal consequences across all five queendoms of the known world, throwing long-standing alliances into disarray as each queendom begins to turn on each other—and new threats to each nation rise from within.

Uniting the stories of women from across the queendoms, this propulsive, gripping epic fantasy follows a warrior queen who must rise from childbirth bed to fight for her life and her throne, a healer in hiding desperate to protect the secret of her daughter’s explosive power, a queen whose desperation to retain control leads her to risk using the darkest magic, a near-immortal sorcerer demigod powerful enough to remake the world for her own ends—and the generation of lastborn girls, the ones born just before the Drought, who must bear the hopes and traditions of their nations if the queendoms are to survive.

Woman of Light by Kali Fajardo-Anstine

"There is one every generation--a seer who keeps the stories."

Luz "Little Light" Lopez, a tea leaf reader and laundress, is left to fend for herself after her older brother, Diego, a snake charmer and factory worker, is run out of town by a violent white mob. As Luz navigates 1930's Denver on her own, she begins to have visions that transport her to her Indigenous homeland in the nearby Lost Territory. Luz recollects her ancestors' origins, how her family flourished and how they were threatened. She bears witness to the sinister forces that have devastated her people and their homelands for generations. In the end, it is up to Luz to save her family stories from disappearing into oblivion.

#Fantasy#historical fiction#Fiction#Magical Realism#to read#tbr#Book Recommendations#reading recommendations#epic#epic stories#epic fiction#new books#new releases#booklr#booktok#book blog#library books#highly recommend

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

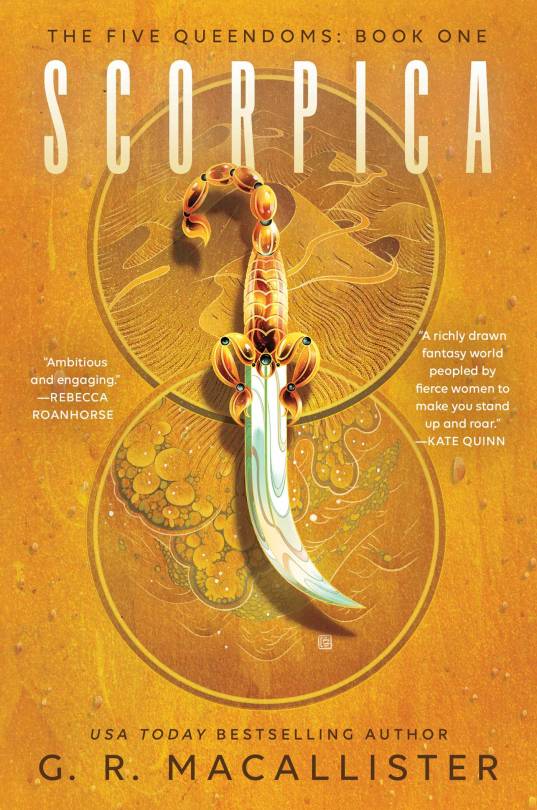

The Many Daughters of Afong Moy

by Jamie Ford

⭐⭐⭐⭐

Synopsis:

"Dorothy Moy breaks her own heart for a living.

As Washington's former poet laureate, that's how she describes channeling her dissociative episodes and mental health struggles into her art. But when her five-year-old daughter exhibits similar behavior and begins remembering things from the lives of their ancestors, Dorothy believes the past has truly come to haunt her. Fearing that her child is predestined to endure the same debilitating depression that has marked her own life, Dorothy seeks radical help.

Through an experimental treatment designed to mitigate inherited trauma, Dorothy intimately connects with past generations of women in her family: Faye Moy, a nurse in China serving with the Flying Tigers; Zoe Moy, a student in England at a famous school with no rules; Lai King Moy, a girl quarantined in San Francisco during a plague epidemic; Greta Moy, a tech executive with a unique dating app; and Afong Moy, the first Chinese woman to set foot in America.

As painful recollections affect her present life, Dorothy discovers that trauma isn't the only thing she's inherited. A stranger is searching for her in each time period. A stranger who's loved her through all of her genetic memories. Dorothy endeavors to break the cycle of pain and abandonment, to finally find peace for her daughter, and to gain the love that has long been waiting, knowing she may pay the ultimate price."

Review:

Jamie Ford brings into perspective the impacts of generational trauma and how it can shape us into the people we are in the present time. Did you know that our history can be traced back through matrilineal genetics because everything we are from our looks to our organelles is accomplished through our mothers? Yes, our fathers contribute to our creation by providing a piece of DNA, but it is the women's contribution that brings us to life.

Dorothy was a highly relatable character to me to an extent. I had experienced a similar situation to the one she was in.

Stuck in a toxic relationship, but doing her best for her daughter. She deserves more, better than what she was given. As all the Moy women deserve.

The generational trauma that she had inherited from the women before her had consumed her entire being. She couldn't see the light at the end of the tunnel. It was heartbreaking.

I will warn you guys, there are some heavy topics within this book so be aware of this. There were times I was begging for a break, a light in the darkness of the pages. None of these women deserved what happened to them and I wanted nothing more than to hug every single one of them.

I loved that Jamie Ford also dove into the Buddhist religion. I was always fascinated with Buddhist teachings and how those within the religion approach life. I plan to purchase a book or two to expand my knowledge of it. I never want to stop learning. Religion has always been a difficult topic for me, but we won't dive into that.

I will not lie to you all, I am finding myself hoping and believing in the invisible string of fate. Where the person who was destined for us is waiting for the right turn of events to bring us together. I can be both a cynic and a hopeless romantic. Just a warning!

I enjoyed this emotional read, but it did take me a while to finish due to how heavy it is. If you are up for an emotional read...pick this book up. Cuddle up with a blanket, some tea, and some Kleenex. Be prepared for the heartache and the longing for a long-lost love.

Favorite Parts/Quotes:

"He gently put the ear tips in her ears, then slipped the metal chest piece between the buttons of his shirt, directly above his heart.

'What are you doing?'

He smiled again and leaned closer.

'I wanted you to hear my heartbeat when I kiss you for the first time.'"

The amount of girly squealing I made at this part was ridiculous. Ridiculous! Anyway, there you have it!

#book blog#bookblr#books#reading#bookish#books and reading#bookworm#book review#The Many Daughters of Afong Moy#Jamie Ford#booktok#booklr#romance books#book journal#book journey#book quote#fiction#romance#emotional

0 notes

Text

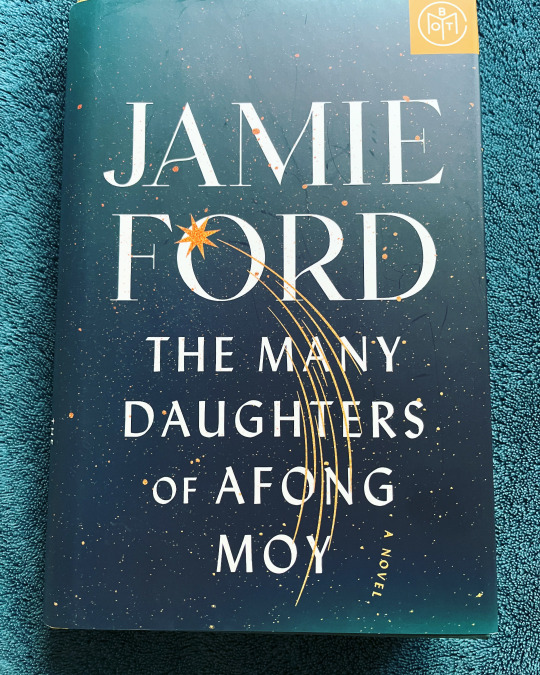

Review: The Many Daughters of Afong Moy by Jamie Ford

Author: Jamie FordPublisher: Atria BooksReleased: August 2nd, 2022Received: Own (BOTM)Warnings: Generational trauma

Wow. There was no way I could read the description of The Many Daughters of Afong Moy and successfully walk away. This is one of those books that demands to be read, you know?

Dorothy Moy is an artist who uses her personal trauma and mental health condition to fuel her art. It’s…

View On WordPress

#Book#Book of the Month#Book Review#Books#BOTM#Fiction#Fiction Review#Historical Fiction#Jamie Ford#Literary#Literature#Review#The Many Daughters of Afong Moy#The Many Daughters of Afong Moy by Jamie Ford

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Many Daughters of Afong Moy

I've been waiting for this one. I also realized when looking up the cover of this book that I did not read his last book! So I just got the ebook and am going to set aside what I started yesterday for that one.

But I digress.

Afong Moy was the first Chinese woman in the US. Her "daughters" in this book are the generations that have come after her. The book pushes ahead past the current time and focuses mianly on Dorothy. Dorothy has dealt with depression and disocciative episodes her whole life. Now, her five-year-old daughter is experiencing the same. She does not want her daughter to live the heartache she has, so she finds a treatment center for those with inherited trauma (for herself). These episodes she has are experiences from her ancesters dating back to Afong Moy.

Pretty interesting concept, right?

Ford is a fabulous writer which is shown again from the beginning to the end of this book. His characterization is top notch which is quite impressive considering he introduced so many spanning from Afong to Dorothy and her daughter.

I rated this four stars on Goodreads. I'd give it four and a half if I could. I just had a hard time keeping straight the storylines of the different women as the plot got going. But that's my only beef. Everything else about it is five stars, and the last sentence... it's one of those last sentences that makes you clutch the book to your chest upon conclusion.

Side note - if you've not yet read Ford's Songs of Willow Frost, read it. It's amazing.

0 notes

Text

Afong Moy (Born 1815-1820, Unknown year of death)

In 1834 Afong Moy was the first recognized Chinese woman to arrive in America. Through the course of her travels across the country, she became the first Chinese person to receive wide public acclaim and national recognition. While her fame was short-lived, she introduced Americans to China through her person and the goods she promoted.

During the 17 years of Afong Moy’s visible presence in America, her treatment as a Chinese woman varied over time. When she first arrived, the public generally responded to China in a positive way. On the edge of patrician orientalism, the perceived “Orient” was one of exoticism, beauty, dignity, and revered history. The Carnes merchants, Francis and Nathaniel G., and the ship captain Benjamin Obear, who brought Afong Moy to America, took advantage of this perception, using the sensual stimulus that came from marketing China trade goods with an exotic. They played on, controlled, and mediated the public’s consciousness of her visual difference—her bound feet, Chinese clothing, and accessories—all to promote their goods.

In the second phase of her experience in the later 1830s, Afong Moy made a transition from a promoter of goods to that of spectacle. During this time, she experienced the conjoining of two worlds—that of the market and the theater. Afong Moy operated simultaneously as entertainment, edification, and billboard. Her new manager occasionally set her against a panoramic backdrop of an illusionistic oriental scene, thus highlighting her cultural exceptionality through her clothing, objects, and images.

Afong Moy’s arrival in a period of great upheaval in American cultural and economic life placed her in the crosshairs of slavery, Native American removal, the moral reform movement, and ambivalent attitudes toward women. On her three-year journey from 1834 to 1837 throughout the mid-Atlantic, New England, the South, Cuba, and up the Mississippi River, her race provided an occasion for ridicule, jingoism, religious proselytizing, and paternalistic control.

Source: https://lithub.com/the-life-of-afong-moy-the-first-chinese-woman-in-america/.

#women in history#19th century history#1800s#immigration history#asian american history#asian women in history

0 notes

Photo

Afong Moy is believed to be the 1st Chinese woman to ever set foot in the US. Sadly, she experienced poor treatment and was displayed as an attraction known as "The Chinese Lady." Her story highlights the long history of exoticism of Asian women.

In 1834, American merchants Nathaniel and Frederick Carne made an arrangement with Moy's father and she was brought from Guangzhou to NYC. The Carnes planned to use her as a marketing ploy to sell imported Chinese products.

Through tours and exhibits, Moy was influential in shaping US perceptions and countering stereotypes of Chinese women. On stage, she was surrounded by luxury goods and "performed" by using chopsticks, singing songs, and answering (and rejecting) audience questions.

Promotions and press coverage spread orientalist depictions of Moy that highlighted her clothing and bound feet. Hordes of white people paid to gawk at her. The challenges she survived are unimaginable.

By the late 30s, evidence shows that Moy experienced financial difficulties, likely due to mistreatment by her "agents." A decade later, Moy was back to performing. Her last known exhibition was in the NYC Hotel in April 1850. After this, records of Moy cannot be found.

#apahm#chinese american#immigration#asian american#chinese history#asian american history#us history#afong moy#orientalism#exoticism

99 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Washington Post Opinion by Lucy Liu: My success has helped move the needle. But it’ll take more to end 200 years of Asian stereotypes.

Lucy Liu is an award-winning actress, director and visual artist.

When I was growing up, no one on television, in movies, or on magazine covers looked like me or my family. The closest I got was Jack Soo from “Barney Miller,” George Takei of “Star Trek” fame, and most especially the actress Anne Miyamoto from the Calgon fabric softener commercial. Here was a woman who had a sense of humor, seemed strong and real, and had no discernible accent. She was my kid hero, even if she only popped up on TV for 30 seconds at random times.

As a child, my playground consisted of an alleyway and a demolition site, but even still, my friends and I jumped rope, played handball and, of course, reenacted our own version of “Charlie’s Angels”; never dreaming that some day I would actually become one of those Angels.

I feel fortunate to have “moved the needle” a little with some mainstream success, but it is circumscribed, and there is still much further to go. Progress in advancing perceptions on race in this country is not linear; it’s not easy to shake off nearly 200 years of reductive images and condescension.

In 1834, Afong Moy, the first Chinese woman known to have immigrated to the United States, became a one-person traveling sideshow. She was put on display in traditional dress, with tiny bound feet “the size of an infant’s,” and asked to sing traditional Chinese songs in a box-like display. In Europe, the popularity of chinoiserie and toile fabrics depicting scenes of Asian domesticity, literally turned Chinese people into decorative objects. As far back as I can see in the Western canon, Chinese women have been depicted as either the submissive lotus blossom or the aggressive dragon lady.

Today, the cultural box Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders find themselves in is more figurative than the box Afong Moy performed in, but it is every bit as real and confining.

Recently, a Teen Vogue op-ed examining how Hollywood cinema perpetuates Asian stereotypes highlighted O-Ren Ishii, a character I portrayed in “Kill Bill,” as an example of a dragon lady: an Asian woman who is “cunning and deceitful ... [who] uses her sexuality as a powerful tool of manipulation, but often is emotionally and sexually cold and threatens masculinity.”

“Kill Bill” features three other female professional killers in addition to Ishii. Why not call Uma Thurman, Vivica A. Fox or Daryl Hannah a dragon lady? I can only conclude that it’s because they are not Asian. I could have been wearing a tuxedo and a blond wig, but I still would have been labeled a dragon lady because of my ethnicity. If I can’t play certain roles because mainstream Americans still see me as Other, and I don’t want to be cast only in “typically Asian” roles because they reinforce stereotypes, I start to feel the walls of the metaphorical box we AAPI women stand in.

Anna May Wong, my predecessor and neighbor on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, lost important roles to White stars in “yellowface,” or was not allowed to perform with White stars due to restrictive anti-miscegenation laws. When Wong died in 1961, her early demise spared her from seeing Mickey Rooney in yellowface and wearing a bucktooth prosthetic as Mr. Yunioshi in the wildly popular “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

Hollywood frequently imagines a more progressive world than our reality; it’s one of the reasons “Charlie’s Angels” was so important to me. As part of something so iconic, my character Alex Munday normalized Asian identity for a mainstream audience and made a piece of Americana a little more inclusive.

Asians in America have made incredible contributions, yet we’re still thought of as Other. We are still categorized and viewed as dragon ladies or new iterations of delicate, domestic geishas — modern toile. These stereotypes can be not only constricting but also deadly.

The man who killed eight spa workers in Atlanta, six of them Asian, claimed he is not racist. Yet he targeted venues staffed predominantly by Asian workers and said he wanted to eliminate a source of sexual temptation he felt he could not control. This warped justification both relies on and perpetuates tropes of Asian women as sexual objects.

This doesn’t speak well for AAPIs’ chances to break through the filters of preconceived stereotypes, much less the possibility of overcoming the insidious and systemic racism we face daily. How can we grow as a society unless we take a brutal and honest look at our collective history of discrimination in America? It’s time to Exit the Dragon.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Opinion by Lucy Liu

April 29, 2021 at 7:00 a.m. EDT

Add to list

Lucy Liu is an award-winning actress, director and visual artist.

When I was growing up, no one on television, in movies, or on magazine covers looked like me or my family. The closest I got was Jack Soo from “Barney Miller,” George Takei of “Star Trek” fame, and most especially the actress Anne Miyamoto from the Calgon fabric softener commercial. Here was a woman who had a sense of humor, seemed strong and real, and had no discernible accent. She was my kid hero, even if she only popped up on TV for 30 seconds at random times.

As a child, my playground consisted of an alleyway and a demolition site, but even still, my friends and I jumped rope, played handball and, of course, reenacted our own version of “Charlie’s Angels”; never dreaming that some day I would actually become one of those Angels.

I feel fortunate to have “moved the needle” a little with some mainstream success, but it is circumscribed, and there is still much further to go. Progress in advancing perceptions on race in this country is not linear; it’s not easy to shake off nearly 200 years of reductive images and condescension.

In 1834, Afong Moy, the first Chinese woman known to have immigrated to the United States, became a one-person traveling sideshow. She was put on display in traditional dress, with tiny bound feet “the size of an infant’s,” and asked to sing traditional Chinese songs in a box-like display. In Europe, the popularity of chinoiserie and toile fabrics depicting scenes of Asian domesticity, literally turned Chinese people into decorative objects. As far back as I can see in the Western canon, Chinese women have been depicted as either the submissive lotus blossom or the aggressive dragon lady.

Today, the cultural box Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders find themselves in is more figurative than the box Afong Moy performed in, but it is every bit as real and confining.

Recently, a Teen Vogue op-ed examining how Hollywood cinema perpetuates Asian stereotypes highlighted O-Ren Ishii, a character I portrayed in “Kill Bill,” as an example of a dragon lady: an Asian woman who is “cunning and deceitful ... [who] uses her sexuality as a powerful tool of manipulation, but often is emotionally and sexually cold and threatens masculinity.”

“Kill Bill” features three other female professional killers in addition to Ishii. Why not call Uma Thurman, Vivica A. Fox or Daryl Hannah a dragon lady? I can only conclude that it’s because they are not Asian. I could have been wearing a tuxedo and a blond wig, but I still would have been labeled a dragon lady because of my ethnicity. If I can’t play certain roles because mainstream Americans still see me as Other, and I don’t want to be cast only in “typically Asian” roles because they reinforce stereotypes, I start to feel the walls of the metaphorical box we AAPI women stand in.

Anna May Wong, my predecessor and neighbor on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, lost important roles to White stars in “yellowface,” or was not allowed to perform with White stars due to restrictive anti-miscegenation laws. When Wong died in 1961, her early demise spared her from seeing Mickey Rooney in yellowface and wearing a bucktooth prosthetic as Mr. Yunioshi in the wildly popular “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

Hollywood frequently imagines a more progressive world than our reality; it’s one of the reasons “Charlie’s Angels” was so important to me. As part of something so iconic, my character Alex Munday normalized Asian identity for a mainstream audience and made a piece of Americana a little more inclusive.

Asians in America have made incredible contributions, yet we’re still thought of as Other. We are still categorized and viewed as dragon ladies or new iterations of delicate, domestic geishas — modern toile. These stereotypes can be not only constricting but also deadly.

The man who killed eight spa workers in Atlanta, six of them Asian, claimed he is not racist. Yet he targeted venues staffed predominantly by Asian workers and said he wanted to eliminate a source of sexual temptation he felt he could not control. This warped justification both relies on and perpetuates tropes of Asian women as sexual objects.

This doesn’t speak well for AAPIs’ chances to break through the filters of preconceived stereotypes, much less the possibility of overcoming the insidious and systemic racism we face daily. How can we grow as a society unless we take a brutal and honest look at our collective history of discrimination in America? It’s time to Exit the Dragon.

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I’m the type of actor who won’t take up the most space in the room,” Daniel K. Isaac said.

This was on a weekday morning, at the Public Theater, an hour or so before Isaac would begin rehearsal for “The Chinese Lady,” a play by Lloyd Suh that runs through March 27. Isaac perched at the edge of his chair — arms crossed, legs crossed, chest concave, occupying the bare minimum of leather upholstery.

“It’s a big chair,” he said.

Isaac, 33, a theater actor and an ensemble player on the Showtime drama “Billions,” combines that reticence with intelligence and warmth, qualities that enlarge every character he plays. (On this day, he was dressed as a New Yorker, all in navy and black, but his socks were printed with black-and-white happy faces.) With his sad eyes and resonant voice, he is an actor you remember, no matter how much or little screen time or stage time he receives.

“The Chinese Lady,” is inspired by the life of Afong Moy, a Chinese woman who came to America as a teenager in 1834 and was exhibited as a curiosity before disappearing from the popular imagination. Isaac plays Atung, her translator, who made even less of a dent in the historical record. “He exists as a side note,” Isaac said.

Isaac created the role, in 2018, in a production from Barrington Stage and the Ma-Yi Theater Company. Even in a two-hander, he rarely takes center stage, ceding that space to Shannon Tyo’s Afong Moy.

“I am irrelevant,” Atung says in the play’s opening scene.

Isaac relates. In the first decade of his career, he felt ancillary, in part because of the roles available to Asian American men. He still feels that way. But now, in his 30s — and with his debut as a playwright coming later this year — he is trying to be the main character in his own life.

“I don’t think I’ve ever had the big break or the large, hugely visible or recognizable thing,” he said. “My life has been a slow burn, a marathon rather than immediate sprint.” Isaac ought to know: He recently trained for his first marathon, and then posted cheerful selfies — of him in his NipGuards — to Twitter.

—————

Seven years, some Off Broadway plays and a few episodes of television later, he landed a small part in the “Billions” pilot. He didn’t think much of it. He knew that plenty of pilots didn’t take. And he’d been killed or written off in ones that did. But “Billions” took, and his character, Ben Kim, an analyst who became a portfolio manager, remains alive. Isaac has appeared in every episode. (Still he didn’t quit his restaurant job until midway through Season 2. And technically, the restaurant told him to go.)

The showrunners of “Billions,” Brian Koppelman and David Levien, hadn’t had huge plans for the Ben character. Once they understood Isaac’s intelligence and versatility, they expanded the role. “Daniel is a fearless actor, and that gives us huge freedom,” they wrote in a joint email.

There’s a sweetness to his “Billions” character, which contrasts with the macho posturing of his colleagues at an asset management company. And that sweetness, as his co-star Kelly AuCoin said during a recent phone conversation, is all Isaac. “He could not be a more lovely or positive person,” he said. “He emanates love.” AuCoin broke off, worrying that his praise sounded fake. Which it wasn’t, he assured me. Then he broke off again. Isaac had just texted to wish him a happy birthday.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

To Pick a Flower

2021, 17 min, color/B&W, HD

Exhibited as part of the group exhibition “Hold the Mirror up to His Gaze: the Early History of Photography in Taiwan (1869-1949)”

2021.03.25 - 08.01

Taipei National Center of Photography and Images

Curated by Hongjohn Lin

Organized by National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, National Center of Photography and Images

Exhibiting Artist(s):

Photographer (Photo Studio):

St. Julian Hugh Edwards

John Thomosn

Lai Afong

George Uvedale Price

Endō Photo Studios

Zhudong Photo Studio

Shih Chiang (Erwo Photo Studio)

Lin Cao (Lin Photo Studio)

Chang Chao-Mu (Chang Photo Studio)

Wu Jin-Miao (Jin-Miao Photo Studio)

Lin Shou-Yi (Lin Photo Studio)

Wu Chi-Jhang (Mingliang Photo Studio)

Huang Yu-Jhu (Guanghua Photo Studio)

Long Chin-San

Peng Ruei-Lin (Apollo Photo Studio)

Deng Nan-Guang

Chang Tsai

Lee Ming-Tiao

Artistic Research:

Shireen SENO

Gao Jun-Honn

Chang Chien-Chi

Tsao Liang-Pin

Liang Ting-Yu

ZHUANG Wu-Bin

Chen Fei-hao

Chen Chin-pao

Nowhere Island Journal

To Pick a Flower

My mother used to tell me that our dining table was as old as I am. I wonder how old the tree was when it was cut down and turned into our table. I am fascinated by such processes of transmutation from the natural world to the human realm, and how a tree takes on new lives long after it has been cut down.

I would like to propose a video essay incorporating archival photographs from the American Colonial Era in the Philippines (1898–1946), exploring the sticky relationship between humans and nature and its entanglements with empire.

During my research, I came across a photograph of a young bride posing for an outdoor portrait, but in place of a groom there was a potted plant. An air of uncertainty abounds. Could it be that her groom is running late or has failed to show up? Is she hesitant to enter into marriage with him, or at all? Or perhaps she is just so uncomfortable and just can’t wait for this photograph to be taken? I imagine it was very hot at the time, and here she is under the sun in a heavy, tight-waisted wedding dress.

Later on, I found a similar photograph of another woman posing outdoors next to a potted plant. I’m not sure if she is a bride, but she is wearing formal attire. This time, the woman is not looking at the camera. She is slightly turned to the side, and her gaze is downward to the dirt road at her feet. Her face is not very clear, but she appears to be in some discomfort. Her left-hand rests on the leaves of the small potted plant at her side, which is almost like a pet or a companion, definitely an object of comfort to her.

There’s a tension to image-making that makes it so interesting—to keep moments of life with you, but in doing so, perhaps you also take something away from them. As a friend once said to me, it’s kind of like picking a flower: it’s beautiful and you want to take it, but you’re killing it at the same time. The camera enables us to straddle that fine line between life and death.

Taking plants and trees as a starting point, this work aims to explore the roots and growth of photography and capitalism in the Philippines.

Exhibition overview

“Hold the Mirror up to His Gaze: the Early History of Photography in Taiwan (1869-1949)” examines the power relations of photographic techniques, colonial experience, and modernity. It explores the context of photography prior to the middle of the 20th century in Taiwan. The exhibition features 600 precious images from the National Center of Photography and Images, also combining nine different artistic research projects, to act as a supplement or something like a footnote to the content. This acts serve as supplements to the exhibited photographs. In terms of display, it is presented in the form of Aby Warburg's Atlas Mnemosyne. Through the juxtaposition of montages, the state of high-density compression of a century’s Taiwanese photography is presented. The highly compressed diachronic structure attempts to emerge the possibility of the "hauntology" of the image. This allows us to reevaluate artistic techniques in terms of their politics, culture, and social history in the global scale. Both on implicit and explicit, a glimpse for the image of Taiwan appears in form of writings of light.

“Hold the Mirror Up to His Gaze” has commissioned 9 artistic research projects to intervene in the exhibition, where they act as supplements. These supplements function like footnotes, branching out as addenda to the exhibition. The nature of art research is its non-replicability. It must emphasize the integration of exhibition, research, and heuristic processes, in addition to the epistemology that is born within. Each invited artist has proposed a specific theme by which to intervene into the exhibition and form open-ended discourses.

More:

https://ncpiexhibition.ntmofa.gov.tw/en/Exhibition/SubtopicDetail/21040211465485203?expoId=21011911215622632

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Instead of inventing answers, Suh leaves us with questions. And by putting the “Chinese Lady” back in front of an audience, he raises further questions about the harms done by watching, even the harms done by continuing to beg a white audience for its attention. Afong Moy believes that she has a mission — she, like other artists we could mention, keeps trying to defeat callousness and hatred with performance.”

0 notes

Photo

Afong Moy (1800s?) The first known Chinese woman to immigrate to the US in 1834. She was brought to the US and put on display as "The Chinese Lady." Afong Moy had endured the extremely painful foot binding process and had 4inch feet. People paid to get a glimpse of Afong Moy, even just to watch her walk, pour tea, and eat. For over 10 years, Afong Moy would travel the US and would be the first interaction many people had with someone of Asian descent. She even met a US President. We lose track of Afong Moy in 1850. Lloyd Suh wrote a poignant, intimate, and visceral play entitled "The Chinese Lady." I was privileged to see this play with @m3lf4c3 when it was put on by our favorite theater company @artistsatplayla in 2019. This play, Afong Moy, the forgotten histories and narratives of millions, and the struggles that the diverse Asian American populations have had to endure are part of the very fabric of our nation. The Asian communities have been vital and vibrant in the growth of this nation. #StopAsianHate #SayHerName #WomenHistoryMonth #AFongMoy #TheChineseLady #AAPI #rememberhername #rememberher #TheMoreYouKnow #herstory #ArtistsAtPlay #aap #AsianAmerican https://www.instagram.com/p/CM5nu8Ig0p1UNs_-YVgjn2wh-YXIokhHVs3r4U0/?igshid=l7j03su2pdqh

#stopasianhate#sayhername#womenhistorymonth#afongmoy#thechineselady#aapi#rememberhername#rememberher#themoreyouknow#herstory#artistsatplay#aap#asianamerican

0 notes

Photo

#QualityTIME always ☑️ #Senin 01 #MARET 2021 #FamilyHappy 🌿 GOD BLess aLL of us 😇 edisi #koLeksi #Wisata #Liburan #HoLidays #originaL #noEditEditan ✍️ #AsLiTuLen ✅ at #Bangka #ExpLore #mie #pangsit #kuetiau #sop #Cukut #TahuKok #Lunch 🍴🍽️🍲 at Mie Bangka Afong - #Pangkalpinang - #BangkaBelitung #Island 🤩 #PraiseTheLORD 😇 keren terbaik mantap hebat luarbiasa ☑️ #enjoy #kuLiner my #trip my #adventure iYes 👍 (at RM AFONG) https://www.instagram.com/p/CL4QLHHJegQ/?igshid=1eeqx3pjapsnr

#qualitytime#senin#maret#familyhappy#koleksi#wisata#liburan#holidays#original#noediteditan#aslitulen#bangka#explore#mie#pangsit#kuetiau#sop#cukut#tahukok#lunch#pangkalpinang#bangkabelitung#island#praisethelord#enjoy#kuliner#trip#adventure

0 notes

Text

2020 RIBA President’s Awards for Research

2020 RIBA President’s Awards for Research News, Richard Beckett Bartlett Design, England

RIBA President’s Awards for Research 2020 News

19 Jan 2021

2020 RIBA President’s Awards for Research, UK

Winners of 2020 RIBA President’s Medal for Research and Research Awards announced

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) has today (Tuesday 19 January) announced the recipient of the RIBA President’s Medal for Research and the winners of the President’s Awards for Research, which celebrate the best research in the fields of architecture and the built environment.

The winner of the 2020 RIBA President’s Medal for Research is Richard Beckett from the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, for ‘Probiotic Design.’ Through exploring the integral role of bacteria in human health, Richard proposes a design approach that reintroduces beneficial bacteria to create healthy buildings.

Probiotic Design was selected from winners of the 2020 RIBA President’s Awards for Research, which were given in four categories: Climate Change, Cities and Community, Design and Technical and History and Theory.

Climate Change:

Louisa Bowles, Jake Attwood-Harris, Raheela Khan-Fitzgerald and Ben Robinson of Hawkins\Brown

Climate Change Winner – The Hawkins-Brown Emission Reduction Tool:

image courtesy of architects practice

The Hawkins\Brown Emission Reduction Tool: providing a data visualisation tool to enable architects to make informed decisions on their projects’ carbon emissions

Cities and Community:

Eli Hatleskog, University of Bristol and University of the Arts London; Flora Samuel, University of Reading

Mapping social values

Design and Technical:

Richard Beckett, Bartlett School of Architecture

image courtesy of researcher / RIBA

Probiotic Design

History and Theory:

Lukasz Stanek, The University of Manchester

Architecture in global socialism: Eastern Europe, West Africa, and the Middle East in the Cold War

RIBA President, Alan Jones, said:

“Research is an important aspect of the architects’ profession, informing how we address the major issues facing the industry, government, society and the world at large. I congratulate the 2020 RIBA President’s Research Award winners for rising to the top and being recognised for the high quality and potential impact of their work. The RIBA President’s Research Medal winner, Probiotic Design, is an impressive, unique and innovative approach to creating healthy buildings. Research can be found across many areas of practice and business, academia, institutes and disciplines, and it’s crucial that we continue to celebrate and support the important role research has in our futures.”

Commendations were also given to the following projects:

Climate Change:

Cole Roskam, University of Hong Kong (Hong Kong)

Constructing climate: The Hong Kong Observatory and meteorological networks within the British imperial sphere, 1842-1912

Constructing Climate – Typhoon of 1874:

photograph by Lai Afong, Hong Kong

Cities and Community:

Alex Young Il Seo, University of Cambridge (UK)

Constructing frontier villages: human habitation in the South Korean borderlands after the Korean War

History and Theory:

Jingru (Cyan) Cheng, Royal College of Art (UK)

Alternative modernism: the architecture of China’s people’s commune

Previously on e-architect:

4 Dec 2018

RIBA President’s Awards for Research 2018

Research project which reconnects homeless people with local support services wins RIBA Research Medal

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) awarded the 2018 RIBA President’s Medal for Research to Chris Hildrey of Hildrey Studio for ProxyAddress: Using Location Data to Reconnect Those Facing Homelessness with Support Services.

One of many interviews carried out in homeless shelters across the UK:

photo © Hildrey Studio

RIBA President’s Awards for Research 2018

RIBA 2017 President’s Awards for Research

RIBA President’s Awards for Research 2017

RIBA President’s Awards for Research 2016

Location: 66 Portland Place, London W1B 1AD, UK

Architecture Awards

Stirling Prize

RIBA Gold Medal 2010

RIBA President’s Medals Student Awards Winners

RIBA President’s Medals Student Awards Past Winners

RIBA President’s Medals Student Awards 2010 Winners

RIBA President’s Medals Student Awards 2009 Winners

World Architecture Festival Awards

RIBA Awards

RIBA Awards

RIBA Gold Medal

RIBA International Awards

RIBA Manser Medal

Comments / photos for the RIBA President’s Awards for Research 2018 page welcome

RIBA President’s Awards for Research 2018

The post 2020 RIBA President’s Awards for Research appeared first on e-architect.

0 notes