#anapestic trimeter

Text

"Unwell" - a poem in rimas dissolutas written 5/23/2024

#2024#rimas dissolutas#i have been writing about cells. and how hot it is. i haven't posted any of it so u wouldnt know#but i have. my words are true here. i lie a lot in my poetry but this is not that#anapestic meter#anapestic tetrameter#anapestic trimeter#anapestic dimeter#rhyme scheme#cinquains#poem#form poetry#poets on tumblr

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

been working on a translation of seneca’s medea for no real reason other than procrastination (adapting what i did in class into a proper translation) and i love what i’ve done with the place but i don’t know what to do with this

#it isnt in verse because i am not translating iambic trimeter or anapestic dimeter into english. g-d bless#ribbits

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hymn for Pyriscent Seeds 1:1-6

From the teeth of the rats I will flee no more,

to converse at some length with the stones—

to discern when to burn and renew, renew—

for my song it is long overdue!

While fore'er they may gnaw on the bones, my bones,

they have lost what my flesh may restore.

-transmitted by the lingering swarm-mind of an ancient thinkwright to the crew of the independent starship Queen of Argyll before the mind's destruction by wildfire.

#i sure decided on anapestic trimeter and odd lines have an extra iamb#pray that i don't decide the middle rhymes in the middle lines are required#if i ever even write more stanzas of this. i only really need the one for the story#the name may change also#i mean it's probably a name chosen by the crew later with more perspective on what is happening

0 notes

Text

I'm supposed to be asleep right now, why am I analyzing the lyrical structure of Rasputin according to what I know about poetry so I can create lyrics that follow the same beat and pattern for a nonsensical LL parody

#ernest talks#for anyone interested the pattern i found so far is an quatrain consisting of two lines in iambic trimeter#followed by two lines that i cannot define the meter of but they have an anapestic beat followed by something i cannot determine#either iambic or spondaic beats#and that's just the opening quatrain of the lyrics#I'm too awake for this i need to sleep

0 notes

Text

using "iambic pentameter" to describe solas' speaking style is not completely accurate. iambic pentameter is a specific type of poetic meter that's extremely common in english-language poetry, but it's not a catch-all for any poetic meter.

the "iambic" part of iambic pentameter means it uses iambs as its metrical foot, which is the basic rhythm unit in poetry. iambs are structured as one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllable. the "pentameter" part means it uses five feet in its meter -- pent meaning five. so a line of iambic pentameter is five iambs, and reads like this:

and-ONE and-TWO and-THREE and-FOUR and-FIVE

or:

shall-I com-PARE thee-TO a-SUM mer's-DAY

pentameter is great for speaking, which is why shakespeare used it so much, but not terribly musical. music is often written in tetrameter (four iambs), or an alternating tetrameter-trimeter (three iambs) combo which is called "ballad meter." (ballad meter is why you can sing most emily dickinson poems to the tune of the pokémon theme song, which is extremely funny but not relevant here.)

"solas meter" isn't in iambic pentameter, and even though it's based on a song it's not in ballad meter either. it does largely use iambs, so folks are on the right track. the structure is usually two lines of iambic tetrameter (four iambs) followed by a third line of iambic pentameter (five iambs) with an extra unstressed syllable tacked on the end:

i-JOUR neyed-DEEP in-TO the-FADE in-AN cient-RUINS and-BAT tle-FIELDS to-SEE the-DREAMS of-LOST ci-VIL i-ZA tions

the tetrameter gives it a nice musical rhythm. "hallelujah" is written in 6/8 and the iambs give you that eighth note-quarter note rhythm here. but what about that third line? the extra unstressed syllable is a "feminine ending," which you can see in the famous soliloquy from hamlet:

to-BE or-NOT to-BE that-IS the-QUES tion

in my opinion, the feminine ending is part of what gives "solas meter" that wistful, soft feeling that weekes is going for. ending on an unstressed syllable takes the wind out of the line's sails a bit. when it's alongside regular iambic meters, it can feel unresolved. ending in a stressed syllable every line can get sing-songy (see previous point about ballad meter, i want to be the very best, etc. etc.), so a feminine ending can make a line more conversational.

"hallelujah" uses this four-four-five meter for verses, although not always perfectly:

now-i-HEARD there-WAS a-SE cret-CHORD that-DA vid-PLAYED and-it-PLEASED the-LORD but-YOU don't-RE ally-CARE for-MU sic-DO ya

there's a couple sneaky anapests in there where iambs should be (and-it-PLEASED and now-i-HEARD are both U-U-S), but i'm not here to tell leonard cohen how to write songs. songwriting is not beholden to the same rigid meter that poetry is because it's intended to be paired with music, and the music is what's driving the rhythm, not the lyrics.

weekes has said they specifically used the k.d. lang version, and lang omits the "now" in the first line so it scans a little better with tetrameter. jeff buckley and brandi carlile did the same in their covers, so it seems there's an impulse when singing to make this line fit the meter more neatly.

now the refrain, which is just "hallelujah, hallelujah, hallelujah, hallelujah," is not iambic at all. it uses "ionics," which are four-syllable metric feet (iambs are two) that are U-U-S-S. minor ionics are unstressed syllables first, major ionics are stressed syllables first. so we've got minor ionic meter here:

hal-le-LU-JAH, hal-le-LU-JAH hal-le-LU-JAH, hal-le-LU-JAH

"solas meter" uses this ionic meter too:

ev-ery-GREAT-WAR has-its-HER-OES i'm-just-CUR-I-OUS what-kind-YOU'LL-BE

"curious" doesn't quite scan here because it's a dactyl word getting shoehorned into an ionic foot. dactyls are S-U-U -- e.g. "benedict cumberbatch" is a double dactyl. you could try the old-school poetry strategy of just dropping a syllable and going for "cur'ous," but that's a bit much. i'm not gonna tell weekes how to write dialogue any more than i'm going to tell leonard cohen how to write songs!

so in conclusion: "solas meter" is a combination of iambic tetrameter, iambic pentameter with feminine endings, and ionic meter. themoreyouknow.gif

for more on this, check out james frankie thomas' great explanation of poetic meter at the paris review, which specifically goes into the nitty-gritty of "hallelujah."

[this was original posted as a reblog of felassan's great post on the same topic, but i thought it merited its own post]

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

here is a list of different poetic forms that might help you get started if you’re feeling a bit stumped, unsure, or it might give you a challenge if you want to try something new! <3

Blank verse: Blank verse is poetry written with regular metrical but unrhymed lines, almost always in iambic pentameter.

Examples:

Villanelle: The villanelle is a nineteen-line poetic form consisting of five tercets (3 lines) followed by a quatrain (4 lines). There are two refrains and two repeating rhymes, with the first and third line of the first tercet repeated alternately at the end of each subsequent stanza until the last stanza, which includes both repeated lines.

Examples:

do not go gentle into that good night by dylan thomas

10 villanelle poem examples to study

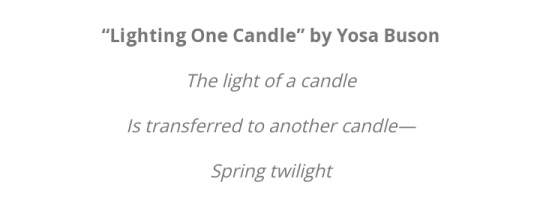

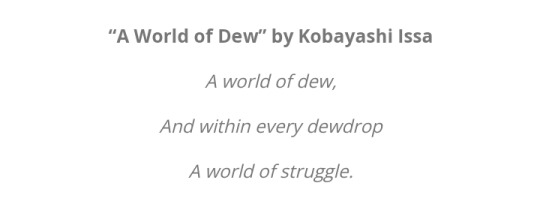

Haiku: The haiku is of ancient Japanese origin. It usually contains 17 syllables in 3 lines of five, seven, five (though modern examples do not systematically follow that pattern). Haiku poems typically contain references to nature.

Examples:

Sonnet: Traditionally, the sonnet is a fourteen-line poem written in iambic pentameter, employing one of several rhyme schemes, and adhering to a tightly structured thematic organization. The two main types of sonnets are the following:

• Shakespearean (or English) sonnet: three quatrains (4 lines) and a couplet (2 lines). Rhymes are ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG

• Petrarchan (or Italian) sonnet: divided into two stanzas, an octave (8 lines) followed by a sestet (6 lines). Rhymes are ABBAABBA + CDECDE or CDCDCD

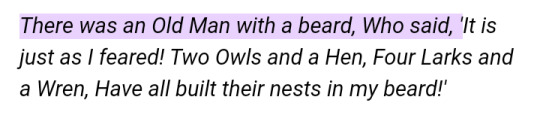

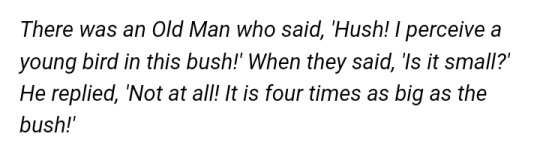

Limerick: A limerick is a form of verse, usually humorous and frequently rude, in five-line, predominantly anapestic trimeter with a strict rhyme scheme of AABBA, in which the third and fourth lines are typically shorter.

Examples:

Elegy: A melancholy poem that serves the purpose of a lament for or a celebration of a deceased person.

Examples:

Elegies, Book One, 5 BY CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE

Lycidas, BY JOHN MILTON

Because I could not stop for Death, BY EMILY DICKINSON

Ode: An ode is a lyrical poem that expresses praise, glorification, or tribute, with the subject matter being a person, event, or idea. Classic odes contain three sections: a strophe, an antistrophe, and an epode—effectively a beginning, middle, and end.

Example:

Ode on a Grecian Urn, by JOHN KEATS

Concrete poem: Also known as visual poetry, it is essentially poetry which is shaped in a certain way which adds to its meaning.

Found poem: Found poetry is a form of poetry in which you create a poem by cutting up, remixing, or otherwise transforming an existing piece of text. (you can use dialogue from the show/scripts?)

Blackout poetry: Blackout poetry is the process out taking an already existing piece of text and blacking out the words save for a few select ones that take on new meaning.

#writing#writing poetry#poetry resources#poetry#poetic forms#how to write a poem#writing resources#resources#insp#buddie poetry event#poemsbybuddie

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

i cannot figure out exactly what meter is going on here but i know it's something! sounds almost like a limerick but it's not quite anapestic trimeter. might post more analysis later, i swear I've seen Brennan bust out full iambic pentameter but I can't remember where

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poetry and music are the same thing but with different names.

Like 3/4 is just the music therm for iambic trimeter: -! -! -!

And 6/8 is an anapestic dimeter: --! --!

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

really good limericks

a limerick is a humorous five-line poem that follows an AABBA rhyme scheme in anapestic trimeter. this blog is collecting some Really Good Limericks :)

submission guidelines:

no bigotry or harassment of any kind

if you did not write the limerick you are submitting, please properly credit the author!

your poem must follow the rules of a limerick!

submit your masterpiece here

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lime Ranch

If I’d had to guess, I would have thought “limerence” meant a tendency to speak in anapestic trimeter. My phone’s autocorrect would like to argue that it isn’t even a real word, and the “Lime Ranch” that it assumes I must have meant actually doesn’t even sound like a bad flavor. I’d like to try that, I think. Like a zesty, creamy guac…

#here’s where I admit the things I didn’t know#Virginia Woolf wasn’t Amurican?#Does i go before e after ch? Or is that still after c?#embarrassing secrets

1 note

·

View note

Text

i don’t care about quatrains and tetrameter and ottava rima and assonance and metonymy and monorhyme and villanelle and ballads and trimeter and dactyl and enjambment and anapest. i just want to read a poem and cry.

#i love my silly lil romantic poets that i’m studying at the moment#but i talk more about how they don’t follow certain forms and structures than if they actually do follow them#wordsworth and keats and coleridge are currently my besties#poetry#han struggles

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An untitled quatrain written 10/29/2019

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Long Is a Limerick?

Limericks are a distinctive and playful form of poetry known for their specific structure and humorous tone. Understanding the length and structure of a limerick is essential for both writing and appreciating this unique poetic form. This article explores the length of a limerick, detailing its structure, rhythm, and variations, while providing insights into its historical context and contemporary usage.

Understanding the Limerick Structure

The Basic Structure

A limerick is a five-line poem characterized by its specific rhythmic and rhyming pattern. The structure of a limerick is crucial to its form and contributes to its playful and often whimsical nature. Here’s a detailed breakdown:

Lines and Rhymes:

Line 1: Introduces the subject or setting. It typically ends with a word that rhymes with the last word of Line 2.

Line 2: Continues the narrative or description, ending with a word that rhymes with the last word of Line 1.

Line 3: Introduces a new idea or twist. This line often has a different rhyme scheme, rhyming with Line 4.

Line 4: Completes the idea introduced in Line 3, ending with a word that rhymes with the last word of Line 3.

Line 5: Provides a conclusion or punchline, rhyming with Lines 1 and 2.

Rhyme Scheme:

The rhyme scheme of a limerick is AABBA. This means that the first, second, and fifth lines share one rhyme, while the third and fourth lines share a different rhyme.

The Meter of a Limerick

Limericks typically follow a specific meter known as anapestic meter. Here’s how it works:

Lines 1, 2, and 5: These lines generally have three metrical feet, often following anapestic trimeter. This means each line usually has three pairs of short-long syllables (da-da-DUM), with the final foot sometimes containing a single stressed syllable.

Lines 3 and 4: These lines often have two metrical feet, following anapestic dimeter. This means each line has two pairs of short-long syllables (da-da-DUM).

For example, in a traditional limerick:

There once was a man from Peru

Who dreamt he was eating his shoe

He awoke with a fright

In the middle of the night

To find that his dream had come true

The meter and rhyme contribute to the limerick’s musical quality and humor.

Historical Context of Limericks

Origins and Evolution

The limerick form, as it is known today, originated in the early 19th century. The term “limerick” is believed to be derived from a type of singing game or dance associated with the Irish city of Limerick, although the exact connection remains unclear. The form was popularized by Edward Lear, an English poet and artist, in his “A Book of Nonsense” (1846).

Lear’s limericks were characterized by their playful tone and whimsical subject matter, setting a precedent for the genre. Over time, limericks have evolved and been adapted by various poets and writers, maintaining their popularity due to their simplicity and humor.

Cultural Significance

Limericks have become a staple in English-language humor and are often used in various social contexts, including parties, educational settings, and literary circles. Their brevity and rhythmic nature make them accessible and enjoyable for audiences of all ages.

Writing a Limerick: Tips and Techniques

Crafting the Lines

When writing a limerick, focus on the following aspects to ensure that it adheres to the traditional structure and rhythm:

Rhyming Words:

Identify rhyming words for Lines 1, 2, and 5 that fit well with the chosen theme or subject.

Find different rhyming words for Lines 3 and 4 that complement the narrative or twist.

Meter:

Ensure that Lines 1, 2, and 5 follow the anapestic trimeter, with three metrical feet.

Ensure that Lines 3 and 4 follow the anapestic dimeter, with two metrical feet.

Humor and Whimsy:

Incorporate humor, wit, or an unexpected twist to align with the traditional playful tone of limericks.

Example Limerick

Here’s an example of a limerick that demonstrates the structure and rhythm:

A young girl who lived in a shoe

Had so many children, she knew

She had to have a rest

So she sent them to West

And now she’s got nothing to do

This limerick follows the AABBA rhyme scheme and demonstrates the playful and humorous nature of the form.

Variations and Modern Adaptations

Contemporary Limericks

Modern limericks often experiment with the traditional form, incorporating contemporary themes and styles. While the core structure and rhyme scheme remain the same, poets may adjust the meter or content to reflect modern sensibilities or social commentary.

Extended Forms

Some poets and writers have extended the limerick form into longer compositions or series. These extended limericks often maintain the AABBA rhyme scheme but may include additional lines or stanzas to develop a more complex narrative or theme.

Cross-Genre Limericks

Limericks have been adapted into various genres and contexts, including:

Educational Limericks: Used to teach concepts or facts in a memorable and engaging way.

Political Limericks: Addressing current events or political issues with satire and humor.

Children’s Limericks: Simplified versions designed to entertain and educate young readers.

Teaching and Sharing Limericks

Educational Settings

Limericks can be a valuable tool in educational settings. Teachers can use limericks to:

Teach Rhyming and Rhythm:

Limericks offer a clear example of rhyme schemes and meter, making them useful for teaching these concepts in poetry.

Encourage Creativity:

Writing limericks can help students develop their creativity and writing skills. The structure provides a framework for experimentation while still allowing for personal expression.

Promote Language Skills:

The playful nature of limericks can engage students in exploring language, vocabulary, and syntax in an enjoyable way.

Sharing Limericks

Public Readings:

Sharing limericks at public readings or literary events can showcase the form’s humor and versatility. These events provide an opportunity for poets to connect with audiences and engage in discussions about the form.

Online Platforms:

Social media and online forums offer platforms for sharing limericks with a wider audience. Poets can use these platforms to connect with other writers, participate in challenges, and receive feedback.

Limerick Contests:

Participating in or organizing limerick contests can be a fun way to engage with the form and showcase creative work. Contests often encourage poets to explore new themes and styles within the traditional structure.

Conclusion

A limerick is a concise and structured form of poetry characterized by its five lines, AABBA rhyme scheme, and playful tone. Understanding the length and structure of a limerick is essential for both writing and appreciating this unique poetic form. By adhering to the traditional structure, experimenting with contemporary themes, and engaging in teaching and sharing, poets can continue to celebrate and explore the limerick’s rich and enduring legacy.

0 notes

Text

Poetic Forms: Cinquains

Cinquains - Five-line stanzas

Limerick: an anapestic trimeter triplet surrounding an anapestic dimeter couplet---i.e. the number of feet per line is 3, 3, 2, 2, 3, rhyming aabba. Limericks often use feminine rhyme, adding to the rollicking comedic effect.

How awkward when playing with glue

To suddenly find out that you

Have stuck nice and tight

Your left hand to your right

In a permanent how-do-you-do!

Constance Levy, “How awkward when playing with glue”

Sapphics: English poets have adapted this quantitative form in many different ways, although the shortened final line is a reliable indicator. The traditional English Sapphic consists of lines of 11, 11, 11, and 5 syllables in falling meters (dactyls and troches), and need not rhyme.

Saw the white implacable Aphrodite,

Saw the hair unbound and the feet unsandalled

Shine as fire of sunset on western waters;

Saw the reluctant….

Algernon Charles Swinburne, an excerpt from Sapphics

Sources: 1 2 3

#poetry#literature#writers on tumblr#writeblr#spilled ink#writing prompt#constance levy#algernon charles swinburne#poem#lit#words#limerick#sapphics#cinquain#writing reference

1 note

·

View note

Text

Writing Process

Rough Draft Ballards with Poetic Devices Proofreading

Ballads

Ballads derive from the French “chanson ballade,” which were poems set to music and intended for dancing. Because of its strong musical background, ballads are associated with a specific meter: Ballads are typically written with alternating lines of iambic tetrameter (dah-DUM dah-DUM dah-DUM dah-DUM) and iambic trimeter (da DUM da DUM da DUM), with every second and fourth line rhyming. They were most popular in Ireland and Britain starting in the Middle Ages, but also gained popularity around Europe and on other continents. Ballads may be relatively short narrative poems, compared to other types of narrative poetry.

Rhyme Scheme

The core structure for a ballad is a quatrain, written in either abcb or abab rhyme schemes. The first and third lines are iambic tetrameter, with four beats per line; the second and fourth lines are in trimeter, with three beats per line.

Theme

The theme of a poem is the message an author wants to communicate through the piece. The theme differs from the main idea because the main idea describes what the text is mostly about. Supporting details in a text can help lead a reader to the main idea.

City Lifestyle

Promiscuity/Rotational Dating/Girlfriend

Clothes

Misogyny

Drug Using/Dealing

Food

Athletes

Crime

Guns

How to Write a Ballad

Choose your topic

Decide on the mood of your ballad

Beat

Use the traditional structure as a guide

ABCB

Write your story in groups of four lines

Edit the lines you've written

Consult a rhyming dictionary or rhyming website

Use lots of imagery

Poetic Devices

Poetic Meter

In poetry, metre or meter is the basic rhythmic structure of a verse or lines in verse. Many traditional verse forms prescribe a specific verse metre, or a certain set of metres alternating in a particular order. The study and the actual use of metres and forms of versification are both known as prosody

Iambic

First an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed

Trochaic

First, a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable.

Spondaic

Spondaic is two stressed syllables back to back.

Anapestic

Anapestic is three-syllable. First, an unstressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable and a stressed syllable.

Dactylic

Stressed syllable then followed by two unstressed syllables.

Rap Flow

Step 1: Count To 4 – Seriously

Step 2: Identify The Kick And Snare

Step 3: 1-2-3-4 = Kick-Snare-Kick-Snare

Step 4: Words Over Beats For Rap Flow

Match Stressed syllables on kick

Imagery

Imagery is a literary device used in poetry, novels, and other writing that uses vivid description that appeals to a readers' senses to create an image or idea in their head. Through language, imagery does not only paint a picture, but aims to portray the sensational and emotional experience within text.

Poets create imagery by using figures of speech like simile (a direct comparison between two things); metaphor (comparison between two unrelated things that share common characteristics); personification (giving human attributes to nonhuman things); and onomatopoeia (a word that mimics the natural sound of a thing).

Oxymoron

A combination of two words that appear to contradict each other

Smilie and Metaphors

A simile is a figure of speech that compares two otherwise dissimilar things, often introduced by the words like or as ('you are like a summer's day'). A metaphor is when a word is used in place of another to suggest a likeness ('you are a summer's day'). This pup is a master of both simile and metaphor.

Rhyme

Rhyme is the repetition of syllables, typically at the end of a verse line. Rhymed words conventionally share all sounds following the word's last stressed syllable. Rhyme is one of the first poetic devices that we become familiar with but it can be a tricky poetic device to work with.

Refrain in Poetry

A poem is an artistic literary work composed of verses that combine rhythm, syntax, and particular language to create an imaginative subject matter.

Syntax

4 Sentence Types in the English Language

The English language is extraordinarily flexible when it comes to building sentences. At the same time, all sentences in English fall into four distinct types:

1. Simple sentences. Simple sentences consist of a single, independent clause. For example: “The girl hit the ball.”

2. Compound sentences. Compound sentences consist of two or more independent clauses joined by a coordinating conjunction. The coordinating conjunctions are “but,” “or,” and “so.” For example: “The girl hit the ball, and the ball flew out of the park.”

3. Complex sentences. Complex sentences consist of an independent clause and one or more dependent clauses joined by a subordinating conjunction. Some subordinating conjunctions are “although,” “because,” “so,” “that,” and “until.” For example: “When the girl hit the ball, the fans cheered.”

4. Compound-complex sentences. Compound-complex sentences consist of multiple independent clauses as well as at least one dependent clause. For example: “When the girl hit the ball, the fans cheered, and the ball flew out of the park.”

3 Ways to Use Syntax in Literature

Besides being critical to conveying literal sense, syntax is also one of the key tools writers use to express meaning in a variety of different ways. Syntax can help writers:

1. Produce rhetorical and aesthetic effects. By varying the syntax of their sentences, writers are able to produce different rhetorical and aesthetic effects. How a writer manipulates the syntax of their sentences is an important element of writing style.

2. Control pace and mood. Manipulating syntax is one of the ways writers control the pace and mood of their prose. For example, the writer Ernest Hemingway is known for his short, declarative sentences, which were well-suited to his terse, clear style of writing. These give his prose a forceful, direct quality.

3. Create atmosphere. By contrast, Hemingway’s fellow story writer and novelist William Faulkner is famous (or infamous) for his meandering, paragraph-long sentences, which often mimic the ruminative thinking of his characters. These sentences, which often ignore the standard rules of punctuation and grammar, help create an atmosphere as much as they convey information.

Instrumental

Layered Pedal Scales

Psychédélique Dance Punch Bass EQ

Custom Sounds (Manipulate Highs, Lows, and Mids)

Arpeggio

Syncopated Percussion

Mélodies et Counter Mélodies

Trumpet Main Instrument

Bonnie & Clyde (Rambo Effect)

A

Machine Pistols with Drums no Social Media;

Shakespeare Impure Aesthetics we are to chic in Vienna;

Passionflower is what we blow;

Dutch Braids, Sports Bra, and Sweats drop that ass Low;

Bonobo ancestry I am from DRC;

Excited for Doha and Skylines in Eco-fleece;

A

Machine Pistols with Drums call me Nick Cannon join my Drumline;

Shakespeare Impure Aesthetics we are to chic in Vienna although I have not met you I call you mine;

Passionflower is what we blow and seeing you G'd up Oh My Oh My;

Dutch Braids, Sports Bra, and Sweats drop that ass Low I am seeing Lugia Fly;

Bonobo ancestry I am from DRC although I beat my Chest for Jane;

Excited for Doha and Skylines in Eco-fleece people are driving to slow in my lane;

Nigö Adam 22 OhGeesy

0 notes

Text

Scansion definition

Scansion is also frequently referred to as ‘scanning’. Scansion in poetry simply means to separate the poem (or a poetic form) into feet by segmenting the different syllables based on length. The Usage And Effects of Scansion in Poetry The Usage And Effects of Scansion in Poetry.It’s helpful for students of all ages to break down the lines and try to work out which beats are stressed and which are unstressed. Scansion is important when one is seeking to gain a better understanding of what a poem’s about and why the writer has used a certain meter. In these lines, readers can also find examples of trochees and iambs. Plus, considering his use of refrains, he ends up using dactyls quite often. Tennyson does not use dactyls throughout this piece, but there are a number of them. Its likely readers will find themselves surprised by Tennyson’s use of meter, considering how uncommonly dactyls play a prominent role in poetry. This makes scanning the poem more interesting as well as more necessary. ‘ The Charge of the Light Brigade’ is a famous Tennyson poem that uses dactyls, one of the least common types of metrical feet. The Charge of the Light Brigadeby Alfred Lord Tennyson Although there are some moments in which Dickinson breaks the pattern, it is fairly consistent throughout. This pattern is often found in ballads and used in church hymns. We passed / the Fields / of Gaz– / ing Grain – We passed / the School, / where Chil / dren strove For example, when scanning, one stanza can be written as The poem is written in alternating iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter. It helps convey the same sense of peace that the speaker feels standing outside at night, looking at the woods, and contemplating death.īecause I could not stop for death by Emily Dickinsonĭickinson’s best-loved poem is a great example of what’s known as common meter. The poem reads smoothly and peacefully throughout without any major interruptions. The pattern of iambs works to give this poem a sing-song-like pattern. To watch / his woods / fill up / with snow. His house / is in / the vil / lage though Whose woods / these are / I think / I know. Consider this line from the beginning of the poem: Those who are familiar with poetry will likely easily recognize his use of iambic pentameter in this piece. This is in part due to the content, but it has a lot to do with his use of rhyme and rhythm. ‘ Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening’ is one of Frost’s best-loved poems. Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening by Robert Frost In the second line, the poet uses one anapest, followed by two iambs. For example, the first two lines which read: Earlier on in the poem, readers can find examples of how Poe combined anapests and iambs. Often, poets find it challenging to use anapests or dactyls regularly. In these lines, the first line of the excerpt uses four anapests, something that’s quite unusual in poetry. In each line, the pauses between metrical feet have been indicated with a /, and the stressed beats are in bold.įor the moon / never beams, / without bring / ing me dreamsĪnd the stars / never rise, / but I feel / the bright eyes The following lines start the final stanza of the poem. If you have never read a poem before, using scansion to figure out which beats are stressed and which are unstressed, and then how many there are per line, is a great way to get a handle on what metrical pattern the poet chose to use (or if they chose to use one at all).Įxamples of Scansion Annabel Lee by Edgar Allan PoeĬonsider these lines from Poe’s famous poem, ‘Annabel Lee.’ In this piece, he uses a combination of iambs and anapests. Sometimes, scansion is known as “scanning.” When scanning, a reader notes where the stressed and unstressed syllables are divides them into their metrical feet, and takes note of where any important pauses are. Specifically, so that the reader can analyze the meter, but, it can also be used to take a closer look at the rhyme scheme and the structure of the stanzas. Scansion refers to how a poem can be broken down into its parts.

1 note

·

View note