#anglo saxon art

Text

Replica and Actual Benty-Grange Anglo-Saxon Boar Crested Helmet, 7th Century CE, Weston Park Museum, Sheffield

#anglo saxon#anglo saxon art#archaeology#helmet#armour#burial#grave goods#warrior#ancient cultures#ancient design#ancient crafts#metalwork#metalworking#relic#artefact#Sheffield

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ulfrun saying goodbye to Cenhelm

#ocs#oc art#my ocs#original character#original art#history#historical ocs#anglo saxon#fantasy#fantasy oc#historical art#anglo saxon art

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the Scriptorium of Lindisfarne Priory, The Lindisfarne Gospels, c. 700, pigment/vellum (British Library [Cotton MS Nero DIV], London)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aldhelm's Brooch

Handmade by me, from Super Sculpey polymer clay, and painted with acrylic paints to resemble antique bronze. It measures 3 inches (10cm) in diameter. I sculpted onto a watchglass so I could get a curvature. The watchglass was removed after baking. It took me approximately 25 hours from start to finish.

A lot of fans talk about wanting a replica of Uhtred's sword. However, I wanted something more personal and meaningful to me. I had been planning to make this brooch for over a year now, and finally had the time and motivation to do so.

Progress photos and reference screenshots below the Keep Reading.

Progress photos. I rolled out the clay and molded it onto a watchglass. Then I printed out my sketch and used a pin to pinpoint the locations of the main features (the little spheres). Afterwards, it was just a lot of fiddly sculpting work to create the details. This was 100% done by hand; I did not use any molds or pre-created forms for this.

Painted version in indoor lighting.

Screencaps of the brooch. And you can see what I had to work with here, lol. Weird fact: his brooch changed color over the seasons! It was shiny gold colored in season 3, silver in season 4, and antique bronze in season 5. Don't know why it changed so much. Aldhelm's brooch is very unique and particular to him. He had a standard large bronze Mercian boar brooch in season 2, just like Aethelred, but for some reason that was changed to this one in season 3. It seemed to coincide with the change in his apparent personality, so I wonder if it was intentional or not?

#aldhelm#the last kingdom#fanart#brooch#handmade#hand crafted#art#sculpture#carving#pottery#polymer clay#clay art#tlk fanart#aldhelm fanart#the last kingdom fanart#anglo saxon#cosplay

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

-A bogan tradie in the court of King Arthur-

inspired by this post by @derinthescarletpescatarian

Guy goes through a portal to a fantasy land and gets magic but the magical ability he gets is to summon power tools. As in he can summon very specific, DIY-grade construction and yard tools from one specific hardware brand

^ that's just your average tradie tbh. op didn't specify how the magic summoning worked so i like to think a wormhole just opens up in a random bunnings somewhere. (the various alcohols spawn in randomly. bogans can just Do That.)

in our universe King Arthur almost certainly did not exist/was an amalgamation of different historical figures from the 5-6th century, so this is probably an alternative universe.

merlin is reimagined as an islamic scholar, it's based on this cool artwork i saw somewhere but can't find DX. (please let me know if you guys can find it). the wise philosopher and advisor with "magical" powers seems fitting for a guy from the islamic golden age (8th-13th century) where great leaps in science, art and philosophy were being made. and they were the guys who preserved and translated the ancient greek texts that were rediscovered by europeans in the renaissance, kicking off the european golden age.

notes and references under the cut:

^ last but not least. this is commonly called a medieval cat in memes. but it was actually drawn by 20th century artist Fernando Botero

300 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey Everyone! Look at this Gold and Rock Crystal Bottle from the Galloway Hoard!

In September of 2014 an avid metal detectorist named Derek Mclennan discovered one of the grandest historical finds in Scottish archaeological history. While searching on church lands near Balmaghie, Mclennan uncovered the Galloway Hoard, a viking age treasure hoard consisting of over 100 objects dating to around 900 AD. While the hoard has some gold objects, most are silver including pieces of jewelry, hack silver, and silver ingots.

Among the objects, the most incredible is a rock crystal bottle that is decorated with gold. The bottle was found inside of a silk pouch, the silk coming from either Byzantium or Asia. The crystal jar itself is not from the middle ages but is Roman and dates to the 4th century. Later in the early middle ages the jar was decorated in gold filigree, at the behest of Bishop Hyguald according to an inscription on the gold work. While the identity of "Bishop Hyguald" is unknown, it is thought that he mostly likely came from Northumbria, an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in northern England. Northumbria would be conquered and occupied by Danish Vikings in the 9th century, which explains how the bottle became a part of the Galloway Hoard.

Today, the bottle along with the rest of the Galloway Hoard is housed at the National Museum of Scotland

#history#antiquities#art#middle ages#medieval art#vikings#anglo saxon england#scotland#scottish history

716 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eric Fraser (1902-1983) ''Anglo-Saxon Poetry'', Selected and Translated by Robert Kay Gordon, 1976

Source

#Eric Fraser#british artists#anglo-saxon poetry#book covers#cover art#book design#dragon slayers#Robert Kay Gordon#poetry

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Boyhood of Alfred the Great by Edmund Blair Leighton

#alfred the great#osburh#osburga#mother#boyhood#art#edmund blair leighton#edmund leighton#wessex#anglo saxon#anglo saxons#history#english#england#middle ages#medieval#osburga oslacsdotter#education#christian#christianity#mediaeval#royal#royalty#royals#house of wessex

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

Painting of an Anglo Saxon warrior (female) that I made for myself a few years back! Got inspired by Germanic and Celtic regalia, an almost endless source of inspiration for these type of characters..

#dungeons and dragons#board games#concept art#fantasy art#tabletop games#digital painting#magic the gathering#ancient history#character design#armor#anglo saxon#vikings#celtic#germanic

658 notes

·

View notes

Text

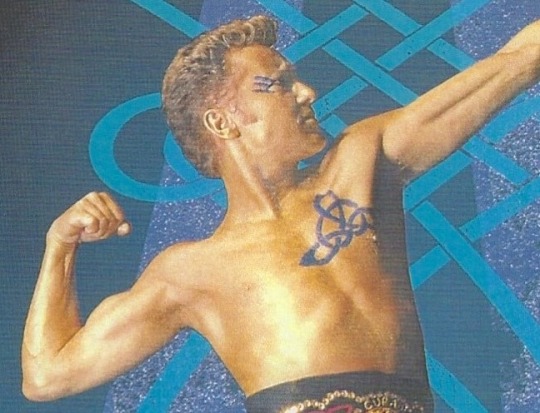

Did the ancient Celts really paint themselves blue?

Part 2: Irish tattoos

Clockwise from top left: Deirdre and Naoise from the Ulster Cycle by amylouioc, detail from The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife by Daniel Maclise, a modern Celtic revival tattoo, Michael Flatley in a promotional image for the Irish step dance show 'Lord of the Dance'

This is my second post exploring the historical evidence for our modern belief that the ancient and medieval Insular Celts painted or tattooed themselves with blue pigment. In the first post, I discussed the fact that body paint seems to have been used by residents of Great Britain between approximately 50 BCE to 100 CE. In this post, I will examine the evidence for tattooing.

Once again, I am looking at sources pertaining to any ethnic group who lived in the British Isles, this time from the Roman Era to the early Middle Ages. The relevant text sources range from approximately 200 CE to 900 CE. I am including all British Isles cultures, because a) determining exactly which Insular culture various writers mean by terms like ‘Briton’, ‘Scot’, and ‘Pict’ is sometimes impossible and b) I don’t want to risk excluding any relevant evidence.

Continental Written Sources:

The earliest written source to mention tattoos in the British Isles is Herodian of Antioch’s History of the Roman Empire written circa 208 CE. In it, Herodian says of the Britons, "They tattoo their bodies with colored designs and drawings of all kinds of animals; for this reason they do not wear clothes, which would conceal the decorations on their bodies" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). Herodian is probably reporting second-hand information given to him by soldiers who fought under Septimius Severus in Britain (MacQuarrie 1997) and shouldn't be considered a true primary source.

Also in the early 3rd century, Gaius Julius Solinus says in Collectanea Rerum Memorabilium 22.12, "regionem [Brittaniae] partim tenent barbari, quibus per artifices plagarum figuras iam inde a pueris variae animalium effigies incorporantur, inscriptisque visceribus hominis incremento pigmenti notae crescunt: nec quicquam mage patientiae loco nationes ferae ducunt, quam ut per memores cicatrices plurimum fuci artus bibant."

Translation: "The area [of Britain] is partly occupied by barbarians on whose bodies, from their childhood upwards, various forms of living creatures are represented by means of cunningly wrought marks: and when the flesh of the person has been deeply branded, then the marks of the pigment get larger as the man grows, and the barbaric nations regard it as the highest pitch of endurance to allow their limbs to drink in as much of the dye as possible through the scars which record this" (from MacQuarrie 1997).

This passage, like Herodian's, is clearly a description of tattooing, not body staining or painting. That said, I have no idea of tattoos actually work like this. I would think this would result in the adult having a faded, indistinct tattoo, but if anyone knows otherwise, please tell me.

The poet Claudian, writing in the early 5th c., is the first to specifically mention the Picts having tattoos (MacQuarrie 1997). In De Bello Gothico he says, "Venit & extremis legio praetenta Britannis,/ Quæ Scoto dat frena truci, ferroque notatas/ Perlegit exanimes Picto moriente figuras."

Translation: "The legion comes to make a trial of the most remote parts of Britain where it subdues the wild Scot and gazes on the iron-wrought figures on the face of the dying Pict" (from MacQuarrie 1997).

Last, and possibly least, of our Mediterranean sources is Isidore of Seville. In the early 7th c. he writes, "the Pictish race, their name derived from their body, which the efficient needle, with minute punctures, rubs in the juices squeezed from native plants so that it may bring these scars to its own fashion [. . .] The Scotti have their name from their own language by reason of [their] painted body, because they are marked by iron needles with dark coloring in the form of a marking of varying shapes." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997)

Isidore is the earliest writer to explicitly link the name 'Pict' to their 'painted' (Latin: pictus) i.e. tattooed bodies. Isidore probably borrowed information for his description from earlier writers like Claudian (MacQuarrie 1997).

In the 8th century, we have a source that definitely isn't Romans recycling old hearsay. In 786, a pair of papal legates visited the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria (Story 1995). In their report to Pope Hadrian, the legates condemn pagans who have "superimposed most hideous cicatrices" (i.e gotten tattoos), likening the pagan practice to coloring oneself "with dirty spots". The location of the visit indicates that these are Anglo-Saxon tattoos rather than Celtic, but some scholars have suggested that the Anglo-Saxons might have adopted the practice from the Brittonic Celts (MacQuarrie 1997).

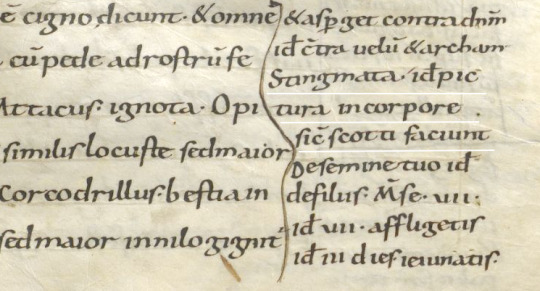

A gloss in the margin of the late 9th c. German manuscript Fulda Aa 2 defines Stingmata [sic] as "put pictures on the bodies as the Irish (Scotti) do." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997).

Fulda Aa 2 folio 43r The gloss is on the left underlined in white.

Irish Written Sources:

Irish texts that mention tattoos date to approximately 700-900 CE, although some of them have glosses that may be slightly later, and some of them cannot be precisely dated.

The first text source is a poem known in English as "The Caldron of Poesy," written in the early 8th c. (Breatnach 1981). The poem is purportedly the work of Amairgen, ollamh of the legendary Milesian kings. In the first stanza of the poem, he introduces himself saying, "I being white-kneed, blue-shanked, grey-bearded Amairgen." (translation from Breatnach 1981)

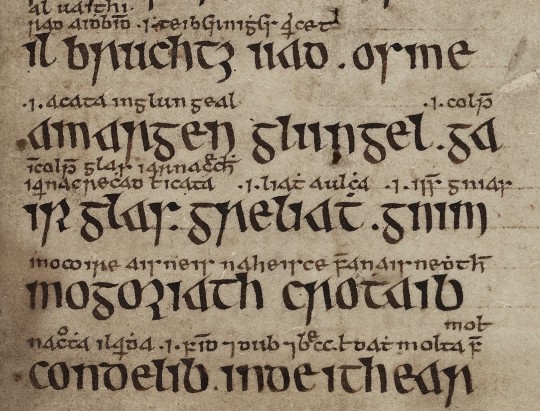

The text of the poem with interline glosses from Trinity College Dublin MS 1337/1

The word garrglas (blue-shanked) has a Middle Irish (c. 900-1200) gloss added by a later scribe, defining garrglas as: "a tattooed shank, or who has the blue tattooed shank" (Breatnach 1981).

Although Amairgen was a mythical figure, the position ollamh was not. An ollamh was the highest rank of poet in medieval Ireland, considered worthy of the same honor-price as a king (Carey 1997, Breatnach 1981). The fact that a man of such esteemed status introduces himself with the descriptor 'blue-shanked' suggests that tattoos were a respectable thing to have in early medieval Ireland.

The leg tattoos are also mentioned c. 900 CE in Cormac’s Glossary. It defines feirenn as "a thong which is about the calf of a man whence ‘a tattooed thong is tattooed about [the] calf’" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997)

The Irish legal text Uraicecht Becc, dated to the 9th or early 10th c., includes the word creccoire on a list of low-status occupations (Szacillo 2012, MacNeill 1924). A gloss defines it as: crechad glass ar na roscaib, a phrase which Szacillo interprets as meaning "making grey-blue sore (tattooing) on the eyes" (2012). This sounds rather strange, but another early Irish text clarifies it.

The Vita sancti Colmani abbatis de Land Elo written around the 8th-9th centuries (Szacillo 2012) contains the following episode:

On another time, St Colmán, looking upon his brother, who was the son of Beugne, saw that the lids of his eyes had been secretly painted with the hyacinth colour, as it was in the custom; and it was a great offence at St Colmán’s. He said to his brother: ‘May your eyes not see the light in your life (any more). And from that hour he was blind, seeing nothing until (his) death. (translation from Szacillo 2012).

The original Latin phrase describing what so offended St Colmán "palpebre oculorum illius latenter iacinto colore" does not contain the verb paint (pingo). It just says his eyelids were hyacinth (blue) colored. This passage together with the gloss from the Uraicecht Becc implies that there was a custom of tattooing people's eyelids blue in early medieval Ireland. A creccoire* was therefore a professional eyelid tattooer or a tattoo artist.

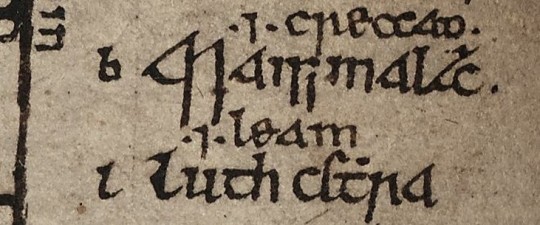

A possible third reference to tattooing the area around the eye is found in a list of Old Irish kennings. The kenning for the letter 'B' translates as 'Beauty of the eyebrow.' This kenning is glossed with the word crecad/creccad (McManus 1988). Crecad could be translated as cauterizing, branding, or tattooing (eDIL). McManus suggests "adornment (by tattooing) of the eyebrow" as a plausible interpretation of how crecad relates to the beauty of the eyebrow (1988). The precise date of this text is not known (McManus 1988), but Old Irish was used c. 600-900 CE, meaning this text is of a similar date to the other Irish references to tattoos.

Kenning of the letter 'b' with gloss from TCD MS 1337/1

There is a sharp contrast between the association of tattoos with a venerated figure in 'The Caldron of Poesy', and their association with low-status work and divine punishment in the Uraicecht Becc and the Vita. This indicates that there was a shift in the cultural attitude towards tattoos in Ireland during the 7th-9th centuries. The fact that a Christian saint considered getting tattoos a big enough offense to punish his own brother with blindness suggests that tattooing might have been a pagan practice which gradually got pushed out by the Catholic Church. This timeline is consistent with the 786 CE report of the papal legates condemning the pagan practice of tattooing in Great Britain (MacQuarrie 1997).

There are some mentions of tattooing in Lebor Gabála Érenn, but the information largely appears to be borrowed from Isidore of Seville (MacQuarrie 1997). The fact that the writers of LGE just regurgitated Isidore's meager descriptions of Pictish and Scottish (ie Irish) tattooing without adding any details, such as the designs used or which parts of the body were tattooed, makes me think that Insular tattooing practices had passed out of living memory by the time the book was written in the 11th century.

*There is some etymological controversy over this term. Some have suggested that the Old Irish word for eyelid-tattooer should actually be crechaire. more info Even if this hypothesis is correct, and the scribe who wrote the gloss on creccoire mistook it for crechaire, this doesn't contradict my argument. The scribe clearly believed that eyelid-tattooer belonged on a list of low-status occupations.

Discussion:

Like Julius Cesar in the last post, Herodian of Antioch c. 208 CE makes some dubious claims of Celtic barbarism, stating that the Britons were: "Strangers to clothing, the Britons wear ornaments of iron at their waists and throats; considering iron a symbol of wealth, they value this metal as other barbarians value gold" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). If the Britons wore nothing but iron jewelry, then why did they have brass torcs and 5,000 objects that look like they're meant to attach to fabric, Herodian?

Brass torc from Lochar Moss, Scotland c. 50-200 CE. Romano-British trumpet brooch from Cumbria c. 75-175 CE. image from the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

Trumpet brooches are a Roman Era artifact invented in Britain, that were probably pinned to people's clothing. more info

Although Herodian and Solinus both make dubious claims, there are enough differences between them to indicate that they had 2 separate sources of information, and one was not just parroting the other. This combined with the fact that we have more-reliable sources from later centuries confirming the existence of tattoos in the British Isles makes it probable that there was at least a grain of truth to their claims of tattooing.

There is a common belief that the name Pict originated from the Latin pictus (painted), because the Picts had 'painted' or tattooed bodies. The Romans first used the name Pict to refer to inhabitants of Britain in 297 CE (Ware 2021), but the first mention of Pictish tattoos came in 402 CE (Carr 2005), and the first explicit statement that the name Pict was derived from the Picts' tattooed bodies came from Isidore of Seville c. 600 CE (MacQuarrie 1997). Unless someone can find an earlier source for this alleged etymology than Isidore, I am extremely skeptical of it.

Summary of the written evidence:

Some time between c. 79 CE (Pliny the Elder) and c. 208 CE (Herodian of Antioch) the practice of body art in Great Britain changed from staining or painting the skin to tattooing. Third century Celtic Briton tattoo designs depicted animals. Pictish tattoos are first mentioned in the 5th century.

The earliest mention of Irish tattoos comes from Isidore of Seville in the early 6th c., but since it seems to have been a pre-Christian practice, it likely started earlier. Irish tattoos of the 8-9th centuries were placed on the area around the eye and on the legs. They were a bluish color. The 8th c. Anglo-Saxons also had tattoos.

Tattooing in Ireland probably ended by the early 10th c., possibly because of Christian condemnation. Exactly when tattooing ended in Great Britain is unclear, but in the 12th c., William of Malmesbury describes it as a thing of the past (MacQuarrie 1997). None of these sources give much detail as to what the tattoos looked like.

The Archaeology of Insular Ink:

In spite of the fact that tattooing was a longer-lasting, more wide-spread practice in the British Isles than body painting, there is less archaeological evidence for it. This may be because the common tools used for tattooing, needles or blades for puncturing the skin, pigments to make the ink, and dishes to hold the ink, all had other common uses in the Middle Ages that could make an archaeologist overlook their use in tattooing. The same needle that was used to sew a tunic could also have been used to tattoo a leg (Carr 2005). A group of small, toothed bronze plates from a Romano-British site at Chalton, Hampshire might have been tattoo chisels (Carr 2005) or they might have been used to make stitching holes in leather (Cunliffe 1977).

Although the pigment used to make tattoos may be difficult to identify at archaeological sites, other lines of evidence might give us an idea of what it was. Although the written sources tell us that Irish tattoos were blue, the popular modern belief that woad was the source of the tattoo pigment is, in my opinion, extremely unlikely for a couple of reasons:

1) Blue pigment from woad doesn't seem to work as tattoo ink. The modern tattoo artists who have tried to use it have found that it burns out of the person's skin, leaving a scar with no trace of blue in it (Lambert 2004).

2) None of the historical sources actually mention tattooing with woad. Julius Cesar and Pliny the Elder mention something that might have been woad, but they were talking about body paint, not tattoos. (see previous post) Isidore of Seville claimed that the Picts were tattooing themselves with "juices squeezed from native plants", but even assuming that Isidore is a reliable source, you can't get blue from woad by just squeezing the juice out of it. In order to get blue out of woad, you have to first steep the leaves, then discard the leaves and add a base like ammonia to the vat (Carr 2005). The resulting dye vat is not something any knowledgeable person would describe as plant juice, so either Isidore had no idea what he was talking about, or he is talking about something other than blue pigment from woad.

In my opinion, the most likely pigment for early Irish and British tattoos is charcoal. Early tattoos found on mummies from Europe and Siberia all contain charcoal and no other colored pigment. These tattoos range in date from c. 3300 BCE (Ötzi the Iceman) to c. 300 CE (Oglakhty grave 4) (Samadelli et al 2015, Pankova 2013).

Despite the fact that charcoal is black, it tends to look blueish when used in tattoos (Pankova 2013). Even modern black ink tattoos that use carbon black pigment (which is effectively a purer form of charcoal) tend to look increasingly blue as they age.

A 17-year-old tattoo in carbon black ink photographed with a swatch of black Sharpie on white printer paper.

The fact that charcoal-based tattoo inks continue to be used today, more than 5,000 years after the first charcoal tattoo was given, shows that charcoal is an effective, relatively safe tattoo pigment, unlike woad. Additionally, charcoal can be easily produced with wood fires, meaning it would have been a readily available material for tattoo artists in the early medieval British Isles. We would need more direct evidence, like a tattooed body from the British Isles, to confirm its use though.

As of June 2024, there have been at least 279 bog bodies* found in the British Isles (Ó Floinn 1995, Turner 1995, Cowie, Picken, Wallace 2011, Giles 2020, BBC 2024), a handful of which have made it into modern museum collections. Unfortunately, tattoos have not been found on any of them. (We don't have a full scientific analysis for the 2023 Bellaghy find yet though.)

*This number includes some finds from fens. It does not include the Cladh Hallan composite mummies.

Tattoos in period art?

It has been suggested that the man fight a beast on Book of Kells f. 130r may be naked and covered in tattoos (MacQuarrie 1997). However, Dress in Ireland author Mairead Dunlevy interprets this illustration as a man wearing a jacket and trews (Dunlevy 1989). Looking at some of the other figures in the Book of Kells, I agree with Dunlevy. F. 97v shows the same long, fitted sleeves and round neckline. F. 292r has long, fitted leg coverings, presumably trews, and also long sleeves. The interlace and dot motifs on f. 130r's legs may be embroidery. Embroidered garments were a status symbol in early medieval Ireland (Dunlevy 1989).

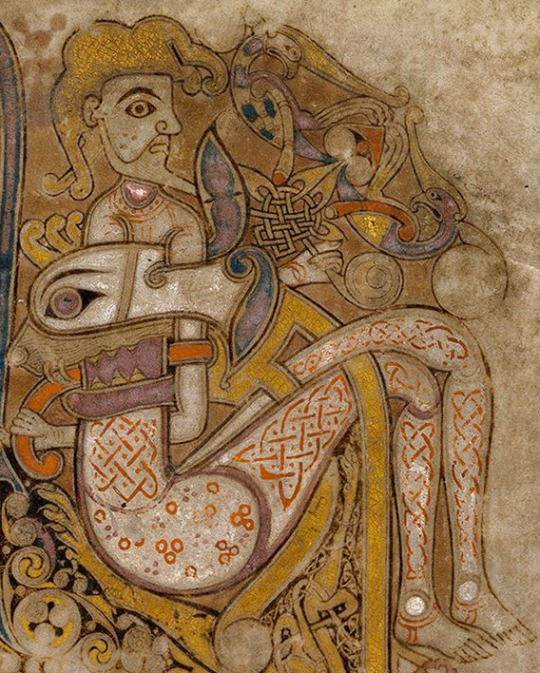

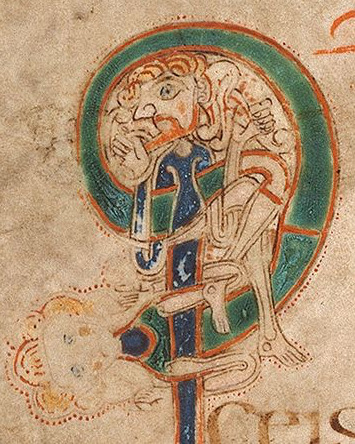

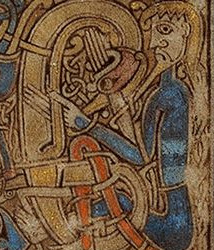

Left to right: Book of Kells folios 130r, 97v, 292r

A couple of sculptures in County Fermanagh might sport depictions of Irish tattoos. The first, known as the Bishop stone, is in the Killadeas cemetery. It features a carved head with 2 marks on the left side of the face, a double line beside the mouth and a single line below the eye. These lines may represent tattoos.

The second sculpture is the Janus figure on Boa Island. (So named because it has 2 faces; it's not Roman.) It has marks under the right eye and extending from the corner of the left eye that may be tattoos.

I cannot find a definitive date for the Bishop stone head, but it bears a strong resemblance to the nearby White Island church figures. The White Island figures are stylistically dated to the 9th-10th centuries and may come from a church that was destroyed by Vikings in 837 CE (Halpin and Newman 2006, Lowry-Corry 1959). The Janus figure is believed to be Iron Age or early medieval (Halpin and Newman 2006).

Conclusions:

Despite the fact that tattooing as a custom in the British Isles lasted for more than 500 years and was practiced by at least 3 different cultures, written sources remain our only solid evidence for it. With only a dozen sources, some of which probably copied each other, to cover this time span, there are huge gaps in our knowledge. The 4th century Picts may not have had the same tattoo designs, placements or reasons for getting tattooed as the 8th c. Irish or Anglo-Saxons. These sources only give us fragments of information on who got tattooed, where the tattoos were placed, what they looked like, how the tattoos were done, and why people got tattooed. Further complicating our limited information is the fact that most of the text sources come from foreigners and/or people who were prejudiced against tattooing, which calls their accuracy into question.

'The Cauldron of Posey' is one source that provides some detail while not showing prejudice against tattoos. The author of the poem was probably Christian, but the poem appears to have been written at a time when Pagan practices were still tolerated in Ireland. I have a complete translation of the poem along with a longer discussion of religious elements here.

Leave me a tip?

Bibliography:

BBC (2024). Bellaghy bog body: Human remains are 2,000 years old https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-68092307

Breatnach, L. (1981). The Cauldron of Poesy. Ériu, 32(1981), 45-93. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007454

Carey, J. (1997). The Three Things Required of a Poet. Ériu, 48(1997), 41-58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007956

Carr, Gillian. (2005). Woad, Tattooing and Identity in Later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 24(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00236.x

Cowie, T., Pickin, J. and Wallace, T. (2011). Bog bodies from Scotland: old finds, new records. Journal of Wetland Archaeology 10(1): 1–45.

Cunliffe, B. (1977) The Romano-British Village at Chalton, Hants. Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society, 33(1977), 45-67.

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

eDIL s.v. crechad https://dil.ie/12794

Giles, Melanie. (2020). Bog Bodies Face to face with the past. Manchester University Press, Manchester. https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/46717/9781526150196_fullhl.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Halpin, A., Newman, C. (2006). Ireland: An Oxford Archaeological Guide to Sites from Earliest Times to AD 1600. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://archive.org/details/irelandoxfordarc0000halp/page/n3/mode/2up

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Lambert, S. K. (2004). The Problem of the Woad. Dunsgathan.net. https://dunsgathan.net/essays/woad.htm

Lowry-Corry, D. (1959). A Newly Discovered Statue at the Church on White Island, County Fermanagh. Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 22(1959), 59-66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20567530

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

McManus, D. (1988). Irish Letter-Names and Their Kennings. Ériu, 39(1988), 127-168. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30024135

Ó Floinn, R. (1995). Recent research into Irish bog bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 137–45). British Museum Press, London. ISBN: 9780714123059

Pankova, S. (2013). One More Culture with Ancient Tattoo Tradition in Southern Siberia: Tattoos on a Mummy from the Oglakhty Burial Ground, 3rd-4th century AD. Zurich Studies in Archaeology, 9(2013), 75-86.

Samadelli, M., Melisc, M., Miccolic, M., Vigld, E.E., Zinka, A.R. (2015). Complete mapping of the tattoos of the 5300-year-old Tyrolean Iceman. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 16(2015), 753–758.

Story, Joanna (1995). Charlemagne and Northumbria : the in

fluence of Francia on Northumbrian politics in the later eighth and early ninth centuries. [Doctoral Thesis]. Durham University. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1460/

Szacillo, J. (2012). Irish hagiography and its dating: a study of the O'Donohue group of Irish saints' lives. [Doctoral Thesis]. Queen's University Belfast.

Turner, R.C. (1995). Resent Research into British Bog Bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 221–34). British Museum Press, London. ISBN: 9780714123059

Ware, C. (2021). A Literary Commentary on Panegyrici Latini VI(7) An Oration Delivered Before the Emperor Constantine in Trier, ca. AD 310. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Literary_Commentary_on_Panegyrici_Lati/oEwMEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

#early medieval#roman era#pict#tattoos#ancient celts#apologies to people who wanted a shorter post#archaeology#art#anecdotes and observations#statutes and laws#irish history#gaelic ireland#medieval ireland#anglo saxon#insular celts#romano british

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

In terms of looking for horses in art history depictions of the Anglo-Saxon noblewoman Lady Godiva are a good place to start. The legend that she is known for tells of her riding naked - only covered by her long hair - through the streets of Coventry in a stand against the oppressive taxation her husband Leofric had imposed on his tenants.

Lady Godiva statue by John Thomas (1813 – 1862), Maidstone Museum, Kent, England.

(Picture source for Lady Godiva statue)

#john Thomas#art#horses#art history#horse#horse art#horse sculptures#lady godiva#statue#Statues#history#anglo saxon#horses in art history

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

Middle Anglo-Saxon Gilt Pin Head, 8th Century CE, North Lincolnshire Museum, Scunthorpe

#anglo saxon#Anglo saxon art#ancient cultures#ancient living#ancient crafts#archaeology#metalwork#metalworking#gilt#knotwork#design work#anglo saxon design#Scunthorpe#Lincolnshire

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

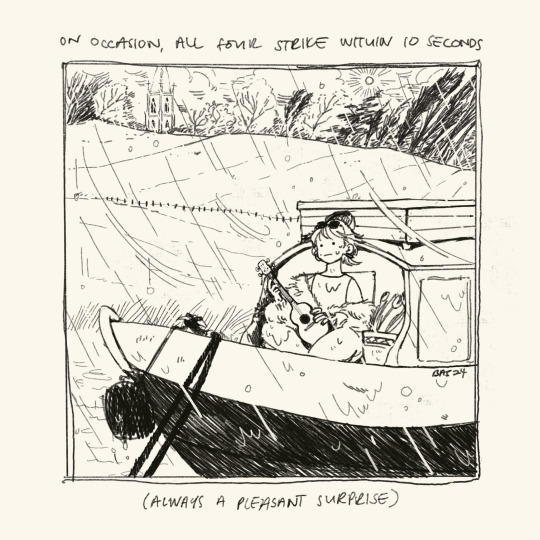

lessons from lide

#lide: Anglo-Saxon for March#journal comic#visual journal#artists on tumblr#comic#comic artist#digital illustration#basil draws#original art#narrowboat

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

🏰Breath of the Æsir

{Loki X Fem.Reader}

Chapter 3: Stories Cannot Burn or Disappear

I am so sorry these chapters are taking me so long. I haven't been the same since Covid! I hope the quality is still good...Thank you for joining my crazy medieval AU Loki fever dream era.

There is a bit of Easter and eclipse magic wound up in this chapter!

Summary: Loki isn't the only one who thinks you are more than a human woman, which buys you time while you figure out how to keep your manor and tenants safe. However, the challenge of nursing a debilitated, power-stripped god adds a layer of complexity to your already daunting task, clouding your judgment when clarity is most needed.

Note to Reader: Yes, Hozier is now a character, your eyes aren't playing tricks on you 😭 But which character will he be? Guess and comment!

Passion and Romance Meter: Nothing explicit yet but hopefully you feel it boiling.

I hope these people don't mind being tagged! I thought you might want to be tagged! Please let me know if you don't want the tag or if you want to be tagged. Also comments and reblogs are healing and joyous for me!

@arcielee @ijuststareatstuffhereok89 @thomase1 @mcufan72 @caffiend-queen @fictive-sl0th @muddyorbsblr @anukulee

@mischief2sarawr @mochie85 @sailorholly @lokisgoodgirl @shambelle97 @lokischambermaid @eleniblue @smolvenger @wheredafandomat @hiroyukinasukawa @meowmeow-motherfucker @latent-thoughts @buttercupcookies-blog @lcolumbia1988 @soulpiercing @wolfsmom1 @mysticmarvelfan

@holdmytesseract @superficialdomina @scrumptious-finicky-illusion @mjsthrillernp @arcielee @poetic-fiasco @gruftiela @thegodofnotknowing @thedistractedagglomeration @tallseaweed

@dangertoozmanykids101 @jennyggggrrr

The clay soil in your husband’s land hadn’t fully absorbed the blood of the Christian god. Not yet at least. The claustrophobic land was hemmed by bogs and marshes, lowlands with the familiar wooden gods made from branches poking out of the muddy banks. The tides to the east would fill the saturated earth till she could take no more before becoming a lake. This system of pooling respiration created a natural barrier for the people. The stillness of the water meant you didn’t stop for long, just enough time to plant your wooden god or light a beeswax candle, burn some leaves as an offering, and then find fast footing across the rickety log bridges built by people no one could remember.

In spring, a carpet of blue wood betony would appear. The town's folk's talk led you to forage it, keeping the blossoms and stems in dark Roman glass, tucked on the kitchen shelf next to the salt. Your husband never noticed your collection, or if he did, he never mentioned it as anything particular or strange. It was a relief to find plants that grew elsewhere, unlike the state of the manor land — high on a hill, flanked by rocky, sandy soil. Collecting plants often made you wonder if Christ might rise from the bogs. You'd just have to wait and see, you supposed, imagining Christ emerging naked from the thick peaty waters, stray herbs clinging to his torso.

Perhaps when Loki showed up, bleeding from his stomach, you'd envisioned something like that before. That desert man had a different name, Jesus of Nazareth. You blushed at the thought of any man, holy or common.

Yet, you didn't blush much while sewing Loki back up. Stitches plunged down his torso into places you'd only seen hinted at on the marble body of Jupiter in Eboracum. Your confident needlework proved itself. If your cheeks reddened, it wasn't from embarrassment but from lack of oxygen, struggling to breathe. Saving a life required haste, much different from the crafts of passing time.

The day the Northmen came you had been already struggling to breathe, you’d lost your air completely and found Loki’s form in front of you when your eyes finally opened again. His hair like ash from the hearth, his eyes the most peculiar color of blue, much like the betony in your waiting Roman jars. Just where had you gone when you’d lost your air? Loki had refused to confront the Danes, refused to fight them. He had handed you back his weapon, leaving you to confront the invaders yourself.

After all, you became a manor wife because your origins had burned in your village's fire, but not in the stories that followed. Stories cannot burn or disappear, especially when people fleeing tell them to the right people in the countryside. Your husband's family had heard your father's tales and believed him. Your hand in marriage was worth more than any dowry. It was all the more disappointing when you couldn't produce an heir or embroidery, and the manor lands remained sandy, rocky, and haunted. You hadn't known a husband should stay close or lie with his wife until Elinor finally told you. Your confidence to heal a stranger, to meet the Northmen at their boat, came from your father. He told you who you were, and like the manor people, you believed him — even if you didn't understand what you were.

The sky had darkened as you came to the mahogany longship anchored next to the wind-ravaged cliffs. You knew to avert your eyes from the mast, the Northern dragon guardian was designed to kill folk such as you. A provocation to your ancestors. There was confusion at their camp, what seemed like hundreds of men were pointing above and shaking their heads. A seer had cast the runes, and the chieftain seemed to not like what the seer had spoken. The rugged man looked up at the sky once more and sent what looked like an envoy to you. He blamed the Norns and you in yet another language you didn’t understand. He could not kill you because it would only curse them more.

Stunned, your trembling hands clutched Loki's blade in disbelief. You ran beneath the still darkening sky, which seemed poised for rain, though no clouds were visible. Looking up, you saw something unimaginable. A planet had fully eclipsed the sun. Your people knew of these events, but you had not witnessed one yourself. As you ran you wondered if the land's spirits had cast a powerful enough curse to scare the Northmen.

Returning home, you found only Loki in the makeshift courtyard, fever-ridden, slumped over the fence. Your heart sank, fearing he was actually dead this time. But the breath of the Æsir still moved through him, you could see his chest moving as you approached.

The village was silent, its people hiding. The only sound was the wind stirring the grain fields and the oak leaves in a dry, papery rhythm. Loki beckoned you inside but he was barely able to move to the porch, he was already worried you’d absorbed too much of the darkness. You fell into his arms, wincing from the feel of his fevered skin through your shift. Significantly taller, Loki's limbs resembled a freshly felled hawthorn. You dragged him closer to the front door, you both were exhausted in the strange day of night.

Your efforts paused for a moment, you readjusted your grip on the stranger. "Saturn is passing over the sun, an eclipse," Loki murmured, breaths faint and labored. How did he know this? Such knowledge was native only to your people. Still reeling from scaring off the Danes, you now faced an eclipse. Loki speculated on the Northmen's possible interpretation of the event. Since much of their knowledge came from his world, he felt he knew exactly what they must have felt seeing the sky darken as you approached.

"They saw the eclipse as a sign of your power. They recognize planetary transits. As you approached them, Saturn crossed the sun's path, a coincidence perhaps in your favor," Loki continued. "But they'll return, and we need to be ready," he cautioned, aware of your mutual defenselessness. He felt responsible for the deaths across these isles, seeking balance, an unfamiliar concept.

You had wanted him to stay long enough to know who he was but now it appeared like he wasn't well enough to be able to leave, even if that is what you both wanted. The truth was, part of you didn't want him to go at all. There was something about him. He knew some of the old ways and where ever he had come from, you suspected again, he had once held a high status.

Loki also continued to contemplate your shared fates. Did the Norns truly allow for this meeting between you as part of the path of the raven’s wingspan, his destiny as a god with no power. He dared to speak to you some of his true thoughts. He felt he owed you some kind of explanation for his resistance to fighting on your behalf.

“Lady, I wish I could help you but as you see I am unwell from my wounds. When I heal, I would like to help you defend your home as part of my thanks, I will find a way to do that does not involve fighting. We have the cosmos on our side it seems, so perhaps there is more luck for our coming together. This is of course if you will continue to have me.”

His pale face seemed even more ghastly, and he laid his body on the porch in a heap, looking very similar to how you first found him. You felt a tenderness stir. You’d felt it for him when you were saving him but now it was tinged with worry for both of your lives and everyone who depended on you.

“Loki I don't want to heal you twice, but it seems this is my fate. Let’s see what you have within you still and if your Gods are listening. I expect you will tell me why you refuse to fight or why you cannot. You owe me the truth. There is much you are not saying.”

He knew he would not be able to hide himself from you as you seemed unable to hide yourself from him. The circumstances unfolding seemed like the actions of reverse spells, instead of concealing they were revealing who you both were. This was vexing to you both.

Despite his sincere words to you, Loki was not sure this troubled land was his final destination. He wondered if he should try and leave as soon as he was able. He was speaking with two tongues. Perhaps he should venture south, go to the Midgard places where panther Gods and pyramids covered in gold existed. Those people were said to do the bidding of the gods with even more ferocity than the Northmen.

Instead, he was sick with fever and stuck with a mysterious, beautiful, and angry woman, whose husband could return at any moment and kill him for what it looked like was happening, even in the middle of a possible invasion. Suddenly his reverie broke as you lifted his shirt to inspect his wound. Your worry for his fever could wait no longer.

"Lady," he said as he batted your hand away.

You protested back, “I have seen you already, why would you be shy now stranger? I need to check your wound, you are feverish,” you continued to pull up his shirt. His gash had indeed become weeping and likely the source of his fever. Whether you liked it or not, you were healing him once again it seemed.

“Wood betony, that is what you need, you are lucky I have some. I’ll see to it Elinor makes you a poultice, and then I am putting you in one of the downstairs bedrooms.” Your eyes were worried even if your words were not. Loki placed his weakened hand on your shoulder, and spoke solemnly, “You know, we need to find your husband.”

You turned your face from him, you didn’t want Loki to notice even the smallest bit of feeling.

“Of course, that is a good idea, this is his manor and his people after all,” you replied. “We can leave when the fever breaks and you can walk without me carrying half your weight,” there was the slightest tinge of playfulness in your words to your surprise. You hoped he did not notice.

As the day was moving into evening, the villagers whispered their suspicions about the stranger you aided. The darkened sky had unsettled them as much as the Northmen. Loki was right, without your husband the manor would devolve into chaos and this would leave the village even more vulnerable.

You watched Loki slowly drag his body to the downstairs bedroom and close the thick doors behind him before you had the chance to redirect him or wish him a good night. You thought better to tell him that he had gone into your husband’s bedroom not the servant’s quarters you had intended for him to rest.

You felt your stomach twist in knots. If your husband came home tonight the wrong impression you worried you would make, would surely be inevitable. You would have to go and move Loki once you were done with your chores. A prospect that left you even more anxious.

Finally, when everyone had gone to sleep and Elinor had gone to her quarters, you stood alone in the empty house contemplating what you should do next. Sleep seemed an impossibility. The eclipse had only been five minutes, but it disturbed the entire day. Now it was nearly midnight and it felt like morning. All time had shifted somehow. Loki sleeping in your husband's bedroom loomed in your head.

To quiet your thoughts you found yourself in the kitchen, sometimes cooking felt relaxing even if you were not good at it. Instead tonight you eyed the row of bottles on your shelf. There was something else calling to you. You grabbed a jar of mistletoe berries, and held them in your hands. Their color was startling.

Suddenly you busying yourself muddling them with the mortar and pestle. If there was a recipe to follow you did not know it, you pulled a few more bottles off the shelf and added the ingredients. Mullein leaves and blackberry.

Pausing for a moment you felt that Loki’s knife was still around your body, you had placed it in a leather holder diagonally across your chest, and forgotten it was there. The knife passed over your breasts and you couldn’t help but touch the length of it.

You hadn't the time to have paid much attention to it before. You noticed the unusual, rich craftsmanship. The inlay was extraordinary. Garnets and chrysoprase. You then gently pulled it out of the holder and carefully pricked your finger with the impossibly sharp tip. This action surprised you.

You inhaled deeply. Crimson blood rolled down your finger and into the stone mixing bowl. You placed your still bleeding fingertip into your mouth hoping to quickly stem the bleeding, but the knife had been too sharp, or you cut yourself too deep.

Quickly, you sucked the wound, blood filling your mouth. You spat the excess into the bowl and placed it on the windowsill, intuitively sensing it needed the moonlight. Just then you heard a deep voice behind you. You were frozen in place, unable to turn around. It was Loki.

"I had no idea you were a seer, you could have told me that sooner and it would have cleared things up," his words rich with sleep and something else.

When you finally turned around you saw he was only wearing his leather trousers and the poultice. Your heart produced a wild, unfamiliar beat, and you steadied yourself against the kitchen table. You weren't a seer, but you could not explain what you were just doing or what you were now feeling.

Before you could stop him, Loki took your mixture from the sill and drank it. "My gods what have you done?" the startled words fell out of your mouth as he placed the now empty bowl back into your hands.

#loki fanfic#loki fanfiction#loki fandom#loki fluff#mcu#loki laufeyson#tom hiddleston#loki#loki smut#loki x reader#loki art#loki fan art#medieval 🏰 loki#medieval fanfic#norse paganism#norse mythology#norse pantheon#norse gods#anglo saxon#druids#loki x you#loki fanart

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wōdan

Source: INSTAGRAM

Background mounting by @gifts-of-heimdall-runes

25th August 2024

#Wodan#wodan#anglo-saxon gods#anglo-saxon pagan gods#anglo-saxon gods art#anglo-saxon gods designs#Lord of Runes#gifts_of_heimdall_runes#Gifts of Heimdall Runes#gifts of heimdall runes#gifts of heimdall#heimdall gifts runes#Heimdall Gifts Runes#Woden pagan gods#anglo-saxon paganism#Anglo-Saxon Pagan#Anglo-Saxon Paganism

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Getting everything ready for launch next week! Check out the preview page, give it a follow, pass it around!

#medieval#illumination#calligraphy#leatherbound#celtic art#celtic#tolkien#norse#middle earth#knotwork#vikings#norse mythology#anglo saxon#english literature#books & libraries#books#book art#illustration

65 notes

·

View notes