#as a collaborator/artist/technician

Text

arts institutions are filled to the fuckin brim with secretive/ambiguous rules of engagement. it is totally uncouth in 2023 to push someone aside when they ask for clarity around processes and protocols. if it isn't written down, shut the fuck up and say you made it up.

#working on some committee thingsssss#and like one of my colleagues and i have agreed we both have some info processing Stuff#which makes it tough to decode these ambiguous practices#like in the rehearsal room the director says#everyone is welcome to participate in table work for this play#do they mean everyone or just actors? do stage managers get to engage full throatedly or are we supposed to just KNOW we're not included#as a collaborator/artist/technician#it is vital that I participate in the art making#i understand some people wanna stay techs and not have a hand in the creative process but#if i'm on a creative team#shouldn't i be part of the creativity? and if not#why does language around this in the rehearsal room assume I know when my participation is wanted or not?#it's so simple to fix this#and i won't stand for lack of clarity just because it serves The Man

1 note

·

View note

Text

BBC: How have you found it collaborating with David and Michael?

Jack Whitehall (Newton Pulsifer): They’re both incredible. They’re such good actors, you could see them in either role. But this is perfect casting. Even at the read through, they were both already singing. The heart of what will make this work is their dynamic. That is the core of this piece.

(https://www.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/mediapacks/good-omens/whitehall)

I totally agree. GO is the result of incredible teamwork: exceptional cast, incredible crew, tailors, designers, make-up artists, graphic designers, producers, authors, musicians, directors, technicians... the list would be endless. Everyone contributed to making it a masterpiece.

BUT without Michael and David and their chemistry, Good Omens wouldn't have been perfect

#chemistry#michael and david#david and michael#michael sheen#david tennant#good omens bts#aziraphale#crowley#good omens#gomens#ineffable husbands#aziracrow

772 notes

·

View notes

Text

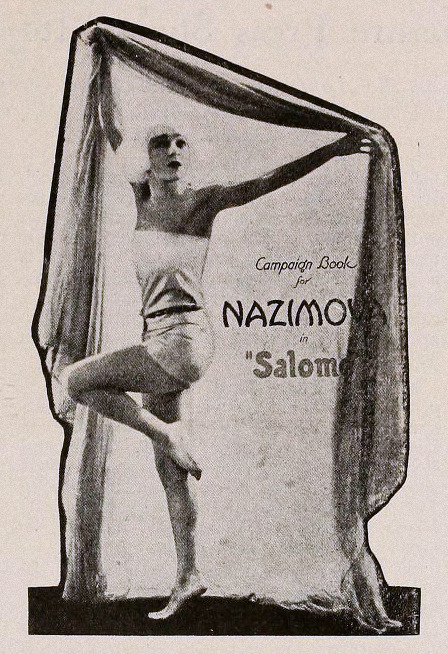

Cosplay the Classics: Nazimova in Salomé (1922)—Part 2

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

As the studio system emerged in the American film industry at the start of the 1920s, many of the biggest stars in Hollywood chose independence. Alla Nazimova, an import from the stage, was one of them. In 1922, she made a series of professional and creative decisions that would completely change the trajectory of her career.

In part one of CtC: Nazimova in Salomé, I described how Nazimova’s independent productions were shaped in response to trends and ideas surrounding young/independent womanhood in America after World War I and the influenza pandemic. Here in part two, I’ll fit these productions, A Doll’s House and Salomé, into the broader context of the big-money business of film becoming legitimate in America.

While the full essay and photo set are available below the jump, you may find it easier to read (formatting-wise) on the wordpress site. Either way, I hope you enjoy the read! Oh and Happy Bi Visibility Day to all those who celebrate!

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

Artists United? Allied Artists and the Release of Salomé

When Nazimova made her screen debut in War Brides (1916), the American film industry was undergoing a series of formative changes. Southern California became the center of professional filmmaking in the US—fleeing New Jersey (where War Brides was filmed) largely because of Thomas Edison’s attempts to monopolize the business. Preferences of audiences and exhibitors shifted away from one and two-reel films and towards feature-length films. The Star System emerged in full force. Nazimova soon relocated to Hollywood, signed a contract with Metro, and reaped the benefits of this boom period for American film artists.

The focus on feature-film production and the marketing of films based on the reputations of specific filmmakers or stars required a greater initial outlay of resources—time, money, and labor. But, it also paid dividends—the industry quickly grew into a big-money business. The underlying implication of that is that a larger share of the profits were shifted from the people doing the creating (artists and technicians) and towards other figures (capitalists). In practice, this also meant film companies would become eligible for listing on the stock exchange and could secure funding from banks and financial institutions, both of which were rare or impossible before the mid-1920s. The major players on the business end of production, distribution, and exhibition, therefore, wanted to consolidate their power and reduce the power and influence of the filmmakers.

To illustrate how momentous this handful of years was in the history of the US film industry, allow me to highlight a few key events. Will Hayes’ office was set up in 1922 to make official Hollywood’s commitment to self-censorship. Eastman Kodak introduced 16 mm film in 1923, a move which, while making filmmaking more accessible and affordable, also widened and formalized the division between the professional industry and amateur filmmaking. Dudley Murphy’s “visual symphony” Danse Macabre[1] was released in 1922—considered America’s first avant-garde film. Nazimova’s Salomé was considered America’s first art film from its initial release in 1923. That these labels were deemed relevant in this period illustrates the line being drawn between those films and film as a conventional, commercial product. The concept of art cinemas in the US was first proposed in 1922 spurring on the Little Cinema movement later in the decade.

from Danse Macabre

from Salomé

As any industry matures, both the roles within it and its output become more starkly delineated. That is to say that, as the US industry began differentiating between art/avant-garde/experimental film and commercial film, the jobs within professional filmmaking also became more firmly defined. Filmmaking has always been a collaborative art, but in the period prior to the 1920s, it was common for people in film to do a little of everything. As a result, what sparse credits made it onto the final film didn’t necessarily reflect all of the work that was done. To illustrate this using Nazimova,[2] at Metro, she had her own production unit under the Metro umbrella. While her films were “Nazimova Productions,” she didn’t have full creative control of her films. However, Nazimova did choose her own projects, develop said projects, and contribute to their writing, directing, and editing. When those films were released, aside from the “Nazimova Productions” banner, her only credit would usually be for her acting. Despite that impressive level of creative power, the studio still had the ultimate say on whether a film got made, and how it would be released. As studios grew and tightened control of their productions, this looser filmmaking style became much less common.

The structure of the industry at this time was roughly tripartite—production, distribution, and exhibition. Generally speaking, the way studio-made films traveled from studio to theatre—before full vertical integration—was that the production company would make available a slate of films of different scales. (Bigger productions with bigger names attached would have a special designation and come with higher rental fees.) Famous Players-Lasky was the biggest production house at the time, though other studios, like Metro, were quickly catching up. Distribution companies would then place this slate of films on regional exchanges, centered in the biggest cities in a given region. Exhibitors (this could be owners of chains like Loew’s in the Midwest and Northeast, the Saengers around the gulf coast, or individual theatre owners) could then rent films through their local exchanges. (This was an ever-shifting industry, so this process was not true for every single film. This is only meant as a quick overview of the system.) As the 1920s wore on, exhibitors began entering the production arena and producers further merged with distribution companies and exhibition chains. Merger-mania was the rule of the day.

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

As merger upon merger took place and a handful of businessmen tried to monopolize the industry, American filmmakers responded by championing the artistic legitimacy of filmmaking in the US. Leading this charge were the very filmmakers on whose backs the big business of film had been built. As noted in Tino T. Balio’s expansive history of United Artists, The Company Built by the Stars:

…Richard A. Rowland, president of Metro Pictures, proclaimed that ‘motion pictures must cease to be a game and become a business.’ What he wanted was to supplant the star system, which forced companies to compete for big names and pay out-of-this-world salaries for their services. Metro, he said, would thenceforth decline from ‘competitive bidding for billion-dollar stars’ and devote its energies to making big pictures based on ‘play value and excellence of production.’”

It’s notable for us that these ideas were espoused by Rowland, head of the studio where Nazimova was currently one of those “billion-dollar stars.” (“Billion-dollar” is obviously a massive overstatement.) It was a precarious time for any filmmaker who cared about the quality and artistry of their work. It was this environment that birthed United Artists, a new production company built around the prestige and reputation of its filmmakers, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, and D.W. Griffith. As the statement announcing the formation of UA detailed:

“We also think that this step is positively and absolutely necessary to protect the great motion picture public from threatening combinations and trusts that would force upon them mediocre productions and machine-made entertainment.”

It’s an accurate assessment of industry trends at the time. If the desired product is a high-quality feature-length film, production is necessarily more expensive. As the UA statement intimates, monopolizing the entire industry and sacrificing quality for quantity to fill the exchanges and theatrical bills was the studio heads’ solution to rising costs. Not a great signal for filmmaking as art in America.

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

So, Nazimova was in good company when she chose to go independent, believing in film as art and that American moviegoers deserved better than derivative, studio-conceived films. Some of the other artists who went independent included George Fitzmaurice (one of the most revered directors of the silent era, though most of his films are now sadly lost), Charles Ray, Max Linder, Norma Talmadge (in alliance with Sam Goldwyn), and Ferdinand Pinney Earle (whose massive mostly-lost artistic experiment Omar Khayyam, I profiled in LBnF). If these filmmakers shared the motivation of UA to create higher-calibre productions, where would the money come from? For Nazimova, the answer was her own bank account.

In 1922, Nazimova’s final film for Metro, Camille (1921), was still circulating widely due to the rising popularity of her co-star, Rudolph Valentino, after the release of Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) and The Sheik (1921). While Nazimova had the funds to complete A Doll’s House and Salomé, there was no sure bet for the films’ releases. Nazimova’s initial concept for her independent productions was the “repertoire” film. This scheme would have seen A Doll’s House released as a shorter film with Salomé as a feature and the two could be rented as a package by exhibitors. It was a creative response to growing tensions between producers and exhibitors over a practice called block booking. Block booking was a strategy studios employed to leverage the Star System to its fullest. They would take the most in-demand films associated with the biggest drawing stars and only make them available in a package deal with productions that were perceived as less marketable. Nazimova was aware that her films at Metro had been rented this way (as the special feature). It’s not completely clear from my research if the decision to release Salomé and A Doll’s House as two features was creative, practical, or a combination of the two. The “repertoire” concept may not have gone according to plan, but it was an early indication that Nazimova was well-informed of the nuances of distribution and exhibition.

Nazimova’s need for proper distribution was met by United Artists’ distribution subsidiary, Allied Artists. United Artists’ first few years were a struggle. Fairbanks, Pickford, and Griffith[3] needed significant time and money to finish the high-quality productions that they promised and Allied was their solution. This distribution arm would release the work of other independent talent using the same exchanges as UA, but under a different banner. Though Allied used UA’s exchanges for distribution, the subsidiary had its own staff. Allied having different branding would also protect the prestige of the UA name. (An unkind, but not entirely inaccurate summary: the money your work brings in is good enough for us, but your work is not.) Allied would have a full release slate to generate the revenue that UA needed to remain in operation.

Nazimova was one of the filmmakers who signed a distribution deal with Allied and had reason to regret it—though she and Charles Bryant didn’t openly rag on UA/Allied.[4] Notably, Mack Sennett had arranged the release of Suzanna (1923) through Allied and was vocal about the company bungling its release. Differences over distribution and exhibition would also lead to Griffith’s exit from the company and a major rift between Chaplin and Pickford-Fairbanks. After 1923, Allied reduced its operation, at least in part because of the bad reputation they were garnering with other filmmakers. Despite numerous independents losing money on productions released through Allied, by 1923, Allied had netted UA 51 million dollars in revenue!

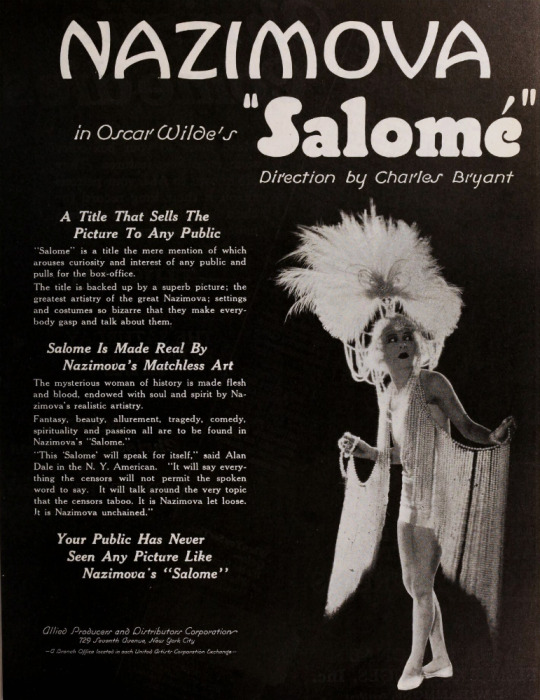

Trade ad for Salomé from Motion Picture News, 10 March 1923

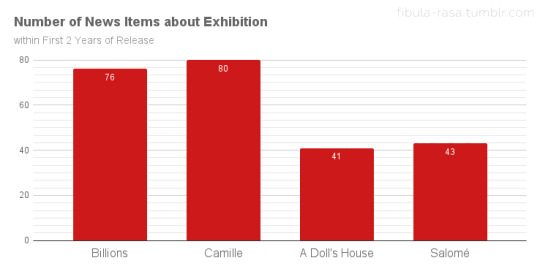

The questionable deals that these independent filmmakers received with Allied are often mentioned in discourse about the period, but very, very rarely does anyone offer details of what Allied’s inadequate distribution looked like. Using the information available to me via Lantern, I collected and analyzed data regarding the release and exhibition of Nazimova’s final two Metro films and both of her Allied films.[5] Looking at the trade publications Exhibitor’s Trade Review, Moving Picture World, Motion Picture News, and Exhibitors Herald, I categorized every item I found about the release or exhibition of Billions (1920),[6] Camille, A Doll’s House, and Salomé. The “release” items are primarily advertisements, reviews, and news items about release dates or pre-release screenings. The number of these items for all four films were comparable.

The items in the “exhibition” category, however, reveal a marked difference between the Metro and Allied releases. This category includes items like first-run theatre listings, exhibitor feedback, and advertising advice for theatre owners. Only counting exhibition items from the first two years (24 months) from the initial release of each film, Billions and Camille had twice as many items as A Doll’s House and Salomé!

While this isn’t necessarily hard data on how many theatres ran each film, it is a rough indicator of how well the films circulated. This data suggests that neither A Doll’s House or Salomé had distribution comparable to the Metro films. In order to compensate for the Rudy factor—Valentino’s major rise to stardom in 1921—which could have affected Camille’s numbers in a big way, I included Billions as well. Billions was sold as a special (a bigger production with premium rental fees) on Nazimova’s name alone. It was not especially well received. Exhibitors/theatre owners had mixed feelings on the film because Nazimova’s previous film, Madame Peacock (1920), had underperformed. Many exhibitors viewed Billions as an improvement, though it still did not meet their perception of Nazimova’s standard of quality. Despite that, Billions had 76 exhibition-related items across its first 24 months of availability to Camille’s 80.

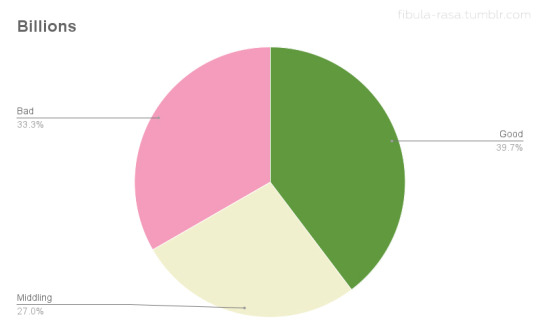

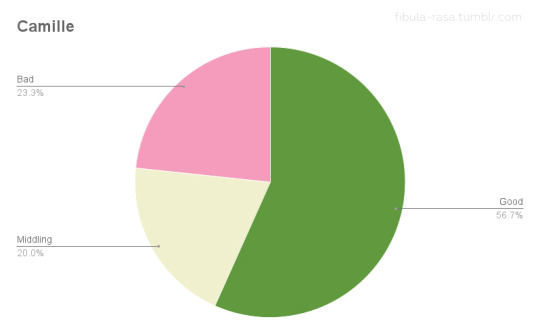

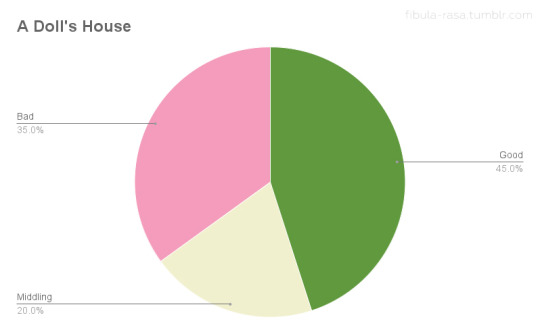

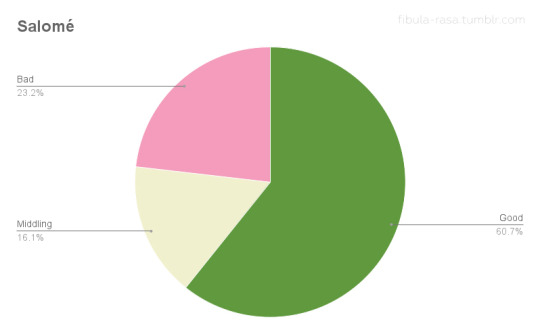

To get a little deeper into this data, I wanted to see how the feedback from exhibitors and theatre owners compared. I broke down the exhibitor feedback for each film as positive, middling, or negative based on how the exhibitors assessed audience response and/or box office receipts. (I discounted feedback that only reflected theatre owners’ own personal assessment of the films without mention of their patrons or receipts.) Positive feedback could be good reception and/or good receipts, middling suggests only average business and no noteworthy reception, and negative indicates poor response and/or poor ticket sales. Since there are so many more items about Camille and Billions than A Doll’s House and Salomé, I compared ratios as an indicator of exhibitor satisfaction. The results were truly surprising.

Theatre owners who rented Salomé may have been in significantly smaller numbers than those who ran Camille, but their satisfaction with ticket sales and audience feedback was roughly equivalent. (Though slightly more positive for Salomé!) The numbers for Billions line up with the qualitative assessment I summarized above, displaying a roughly equal 3-way split. A Doll’s House was the most divisive with the highest proportion of negative feedback of the four films, yet with a higher proportion of positive feedback than Billions.

Taking all of this into account, it’s clear that Salomé did not flop because it was too artsy or esoteric for the American moviegoing public. Such assumptions are obviously not very thoughtful or informed by reliable data.[7] A more historically sound reading is that, as professional filmmaking matured into a “legitimate” industry in the US, the various arms of the business were rigidly formed to fit conventional output. The conservatism that this engendered made the American industry ill-equipped at marketing anything too unconventional or experimental. While Hollywood insiders were lamenting European filmmakers artistically outdoing Americans—especially following the US release of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)—very few people with the power to shape the industry did anything to support experimentation. Given this environment, Salomé could only have been produced independently, but the quickly ossifying distribution and promotional systems didn’t have the range to give it a proper release. Two films contemporary to Salomé, Beggar on Horseback (1925) and The Old Swimmin’ Hole (1921) offer further evidence of the industry’s limitations.

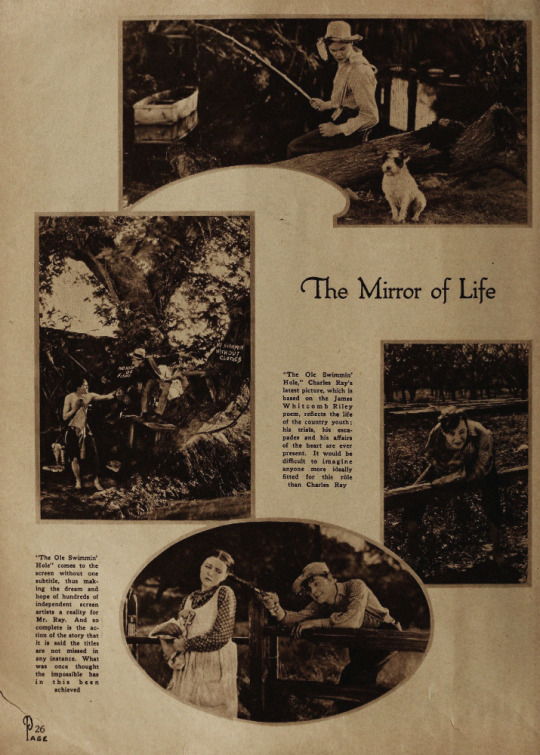

The Old Swimmin’ Hole is a feature-length production by Charles Ray, experimental in that it uses no intertitles. The story is simple and familiar with Ray playing the Huck-Finn-type character he was well known for. Ray’s experiment was not an expensive one and the film was successful. However, decision makers at First National, the film’s distributors, felt that The Old Swimmin’ Hole was simply too complex for small-town Americans to comprehend and it wasn’t released outside of cities. To put it plainly, the distributor’s unfounded concept of ignorant yokels meant that a film about country living was largely inaccessible to anyone actually living in the country. Though the film was well received and turned a profit, this distribution decision likely limited its audience as well as possible revenue from small-town exhibition.

Stills from The Old Swimmin’ Hole from Motion Picture Magazine, April 1921

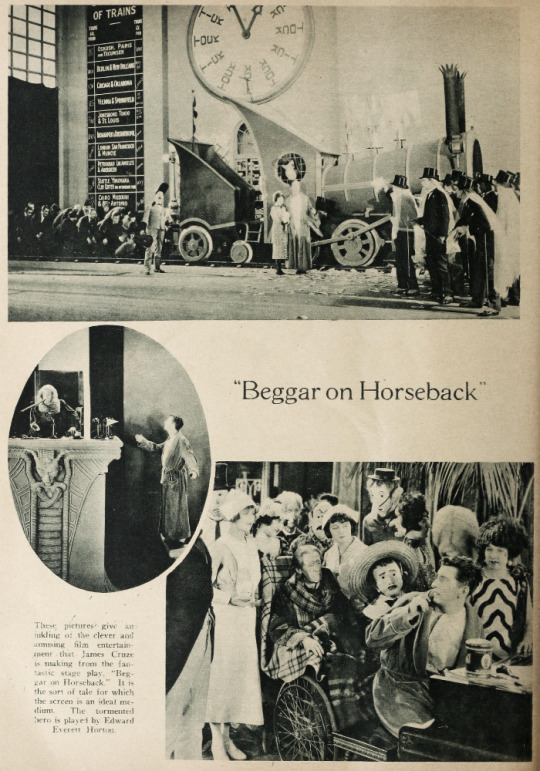

Beggar on Horseback was produced by one of the biggest studios in Hollywood, Famous Players-Lasky, and distributed by Paramount. Starring comedian Edward Everett Horton, Beggar was an expressionist comedy based on a popular play. The film had a popular star, popular source material, and was made and released by a major company, but Beggar was apparently too unconventional for that major company to adequately market it. (Unfortunately, only a few minutes of the film survive, so we can’t fully reassess it unless more is found/identified!)

Stills from Beggar on Horseback from Picture-Play Magazine, August 1925

With all these complicating factors at play, how might have Salomé found its audience in 1922-3? Nazimova and Charles Bryant had innovative ideas for the film’s release that might have done the trick, if they had been able to act on them. Nazimova and Sam Zimbalist had finished cutting Salomé in late-spring 1922. Having spent practically all of her money to finish the film, and following A Doll’s House’s disappointing results, Nazimova was eager for Salomé to hit theatres. Though the film was in the can and private preview screenings had been held by Bryant by summer ‘22, Salomé wouldn’t be released until February of 1923. In studio filmmaking, holding a film in extended abeyance wasn’t ideal but it was not disastrous. Studios had significantly more resources and revenue streams than independent producers. If, for example, the release of Billions had been delayed for seven months, Nazimova still had two films on the Metro exchanges (and therefore in theatres) and Camille would have entered production in the meantime. But for Nazimova as an independent producer, this situation was wholly untenable. (In fact, Pickford, Fairbanks, and Griffith were in a similar untenable situation when they founded Allied.)

Initially, Bryant proposed roadshowing Salomé. Roadshowing is a release strategy for notable film productions where a film is toured around major cities, often with in-person engagements by stars, writers, and/or directors. Nazimova expanded the idea of touring with Salomé not simply as a roadshow, but paired with a short play in which she would star. Double the Alla, double the fun. As far as I can tell, there isn’t publicly available information about why Salomé wasn’t roadshowed. However, we do know that Griffith, as the only non-performer in UA, wanted to utilize different approaches for the release of his films—like roadshowing—and it became one of the major points of disagreement with his fellow UA decision makers. That could be taken as an indication that something similar might have occurred with Nazimova and Allied.

As time dragged on without a release date for Salomé and Nazimova returned to theatrical work—openly admitting to audiences that she was broke—Bryant took matters into his own hands. At the end of December 1922, Bryant negotiated with the owner of the Criterion Theatre in New York City for Salomé to run on New Year’s as a special presentation. In two days, Salomé grossed $2,630, setting records for the theatre. Adjusted for inflation, that’s $48,988.96. It was successful enough that the owner of the Criterion opted to hold the film over. This bold move must have lit a fire under Allied’s tuckuses, as Salomé finally had its first-run release a little over a month later.

In the 1920s, the first-run booking of a film was a crucial part of its further success. Concurrent nationwide release of films wasn’t the norm yet, and if a film was a big production, getting booked at high-capacity motion picture houses in major cities was a necessity. These big city releases would, in theory, generate interest in the film with exhibitors across the country and internationally. Basically, if you spent a lot on a movie but couldn’t land a first-run release, you weren’t likely to turn a profit or even break even. Salomé had a handful of first-run bookings and local reviewers from those cities believed the film would succeed. A reviewer from the Boston Transcript in February 1923 wrote:

“…this newest Salome is something far better than a photographed play. Considered both as picture acting, and as an interesting experiment in design, “Salome” is a notable production. It will have a far and wide reaching influence on future films in this country.”

But, as I mentioned, only a handful of first-run theatres played Salomé, and, taken collectively, the notices I analyzed from contemporary trades imply that it didn’t gain traction once it was made available beyond its initial run.

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

During this regrettably short theatrical run, exhibitors and reviewers from trade publications advised that Salomé was a unique film that called for unique promotion. The overall assumption was that theatre owners knew their patrons and recognised whether out-of-the-ordinary movies were popular with them. Rather than purely judging a film’s quality, exhibitors and trade reviewers had concerns specific to exhibition when providing feedback. These concerns cannot be overlooked if you want to understand their assessments. For example, exhibitor feedback was very often informed by how high the rental fees were for a film, even if exhibitors don’t directly mention said fees. That is to say, a mediocre film might be rated highly if the rental fees were modest (and if block booking wasn’t an issue). Reviewers in the early 1920s, both for popular magazines and trade publications, were already accustomed to the formulaic nature of most studio output. Their reviews commonly expressed fatigue with studio films’ lack of originality. And, perhaps surprisingly, this sentiment was shared among theatre owners as well—particularly when a run-of-the-mill film was sold to them as anything other than a “programmer” (a precursor to B-movies).

What I have learned, not just by analyzing feedback for Salomé, but also for all of the films in my LBnF series, is that when a 1920s reviewer calls out bizarreness in a film, it’s not always a negative quality, even when the review isn’t positive. In the case of reviews written for exhibitors/theatre owners, focussing on what makes a movie different is purely pragmatic. It guides how exhibitors might market films to patrons and helps exhibitors judge if a film would be suitable for their audiences. And, from that same research, I’ve found significant indications there were numerous markets throughout the US that were hungry for novelty—contrary to what studio apparatchiks wanted to admit. So, pointing out Salomé’s bizarreness was a recommendation for those markets to consider renting it as much as it was a warning against renting for theatre owners who only had success with more conventional films.

Cover of the Campaign Book for Salomé reproduced in Exhibitors Herald, 9 February 1924

In the case of Salomé, reviews and feedback upon its release focused on two major points:

The film isn’t “adult” in nature. Well-known productions of Strauss’ opera and the 1918 Theda Bara film of the same name led to a presumption of salaciousness. (I talked a bit about that in Part One!)

The film deserves/requires a build up as an artistic event film.

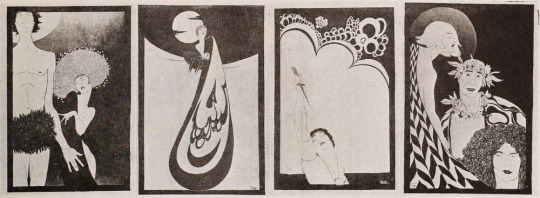

Nazimova’s company helped exhibitors with the latter point in a few ways. The company provided Aubrey Beardsley inspired art posters conceived by Natacha Rambova and executed by Eugene Gise. They printed a book to guide promotion of an artistic spectacle. (So far, I haven’t been able to find a physical or digital copy, so I can’t assess how good the advice was!) Salomé was also distributed with an official musical score, apparently written for a full orchestra.

Art Posters designed by Rambova and painted by Gise as reproduced in Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 10 February 1923

The exhibitors who ran Salomé—and put at least some of this advice into practice—were satisfied with the business it did. By these accounts, the American moviegoing public was attracted by the novelty of Salomé, but what chance were they given to see it?

While this evidence of Allied’s poor distribution work may be circumstantial, it certainly complicates the narratives that Salomé was an unqualified flop or that average Americans weren’t (or aren’t) receptive to artistic experimentation. Given that Nazimova was not the only independent filmmaker who suffered from Allied’s inept distribution, it does seem like the underwhelming business Salomé did was due more to a poor choice of business partners than to any quality of the film or of American moviegoers. That said, with the increasing monopolization of the industry, Nazimova did not have a wealth of options.

Though Salomé was made and released at an tumultuous period for the US film industry, it did eventually find its audience through circulation in art cinemas. As the gap between experimental/avant-garde film widened in the US and the professional industry became less and less tolerant of departures from convention, Americans concerned with film as an art form rallied around amateur filmmaking clubs and art cinemas began popping up in cities by the middle of the decade. Salomé played in these theatres even after the advent of sound—occasionally even today. This is likely the key reason that Salomé survives and we’ve been able to continue to enjoy and reevaluate it one hundred years later.

Salomé is a significant film made at a significant moment in American film history. Nazimova took a major risk in going independent and personally funding two artistic projects. These films were founded on the beliefs that American moviegoers wanted art made by human beings with unique imaginations, feelings, sensibilities and that there was an audience for more than derivative, “machine-made” film. In my opinion, through close analysis of the circumstances of Salomé‘s release, we can see that Nazimova was likely correct, but didn’t get a genuine chance to prove it in her lifetime. Additionally, it’s important to note that Nazimova’s risks did not “ruin” her as is occasionally said. The state of her finances were more greatly affected in the 1920s by her fake husband’s habit of spending her money and by getting swindled by a pair of con artists over her estate, The Garden of Alla. Soldiering on, Nazimova continued to work in both theatre and film for the rest of her life and found more stability with the partner she would meet at the end of the 1920s, Glesca Marshall.

——— ——— ———

Once I finished this “Cosplay the Classics” entry, I realized that it would way too much for me to include a section on another relevant topic to Salomé: Orientalism in Hollywood. But, I feel that the topic is too important to just edit that writing out. Look out for a shorter “postscript” entry soon!

——— ——— ———

☕Appreciate my work? Buy me a coffee! ☕

——— ——— ———

Footnotes:

[1] Danse Macabre is also thought to be a major influence on Walt Disney animating to music, as seen in “Silly Symphonies” and later Fantasia (1940) and Disney’s other musical anthology features. It was also in this period that Disney fled from his debtors in the Midwest to California with his first “Alice” movie. However, the wide-ranging effects of Disney’s business practices were not felt until much later, so that’s another story for another time!

[2] Nazimova was one of a handful of women in Hollywood at the time who held significant creative power. June Mathis and Natacha Rambova, both of whom Nazimova regularly worked with, Mary Pickford and her regular tag-team partner Frances Marion are among some of the others.

[3] Chaplin wouldn’t produce a film for UA until 1923’s A Woman of Paris, as he was fulfilling a pre-existing contract with another studio.

[4] According to Gavin Lambert’s biography of Nazimova (which I discussed as a largely unreliable source in Part One), Robert Florey supposedly advised Nazimova against signing with them, citing Max Linder and Charles Ray as artists who had been “ruined” by their deals. However, the timeline does not quite match up. Though Florey did visit the set of Salomé, Nazimova had already signed the Allied deal by then and Ray had not finished The Courtship of Miles Standish (1923) when Salomé was in production. In fact, there was almost a year and a half between the completion of Salomé and the release of Standish. Whether this was a lapse of memory by Florey or misreporting by Lambert, I can’t be sure.

[5] Originally, I wanted to include Madonna of the Streets (1924) in my comparisons but, at the moment, Lantern has gaps in their Moving Picture World archive for 1924-5. I didn’t want to draw conclusions from incomplete data.

[6] Billions was also a Rambova-Nazimova collaboration. Rambova designed a fantasy sequence for the film.

[7] A mindset that’s still common among commercial media outlets today unfortunately. I could rant and rant about “content” and “content creation” all day but that’s another story for another time.

——— ——— ———

Bibliography/Further Reading

(This isn’t an exhaustive list, but covers what’s most relevant to the essay above!)

Lost, but Not Forgotten: A Doll’s House (1922)

“Nazimova in Repertoire” in Motion Picture News, 29 October 1921

“Alla Nazimova Plans for Her New Pictures” in Moving Picture World, 29 October 1921

“Nazimova Abandons Dual Program for Latest Film” in Exhibitors Herald, 24 December 1921

“Plays and Players”in Photoplay, February 1922

“PICTORIAL SECTION” in Exhibitors Herald, 4 February 1922

“New Nazimova Film May Be Roadshowed“ in Exhibitors Herald, 15 April 1922

“Newspaper Opinions” in The Film Daily, 3 January 1923

“Splendid Production Values But No Kick in Nazimova’s ‘Salome’” in The Film Daily, 7 January 1923

“Claims “Salome” Hit New Mark at N. Y. Criterion” in Exhibitors Herald, 27 January 1923

“Salome” in Exhibitors Trade Review, 20 January 1923

“Nazimova in SALOME” in Exhibitors Herald, 27 January 1923

“Nazimova Appeals To Exhibitors In Behalf of ‘Salome’” in Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 27 January 1923

“Novelty Features Paper and Ads for ‘Salome’” in Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 10 February 1923

“SALOME’ —Class AA” from Screen Opinions, 15 February 1923

Nazimova: A Biography by Gavin Lambert (Note: I do not recommend this without caveat even though it’s the only monograph biography of Nazimova. Lambert did a commendable amount of research but his presentation of that research is ruined by misrepresentations, factual errors, and a general tendency to make unfounded assumptions about Nazimova’s motivations and personal feelings.)

Lovers of Cinema: The First American Avant-Garde 1919-1945 ed. Jan-Christopher Horak (most notably, “The First American Avant-Garde 1919-1945” by Horak, “The Limits of Experimentation in Hollywood” by Kristin Thompson, and “Startling Angles: Amateur Film and the Early Avant-Garde” by Patricia R. Zimmermann)

United Artists: The Company Built by the Stars, Vol. 1 1919-1950 by Tino Balio

#1920s#1922#Salomé#salome#nazimova#alla nazimova#film history#cosplay#queer film#silent era#classic movies#film#avant garde#experimental film#cinema#queer film history#silent cinema#1923#classic cinema#american film#women filmmakers#women in film#silent film#classic film#silent movies#bisexual visibility#cosplayers#natacha rambova#united artists#Metro

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Author Interview

https://www.choiceofgames.com/2024/07/new-author-interview-drew-morrison-bootlegger-moonshine-empire/

I think this is your first time writing interactive fiction, but you’re rather an accomplished playwright, I gather. Tell me a little about your background and what brought you to Choice of Games.

I started writing for theater in middle school, and got my Masters in Playwriting at the University of New Mexico. Dialogue has always been my favorite part of writing, and theater offers such a great way to get together with friends and tell a story. I worked for a devised theater company in Albuquerque for about five years, and I really got attached to the camaraderie that develops around putting up a play, especially when it’s done without a lot of financial resources. It means everybody learns different tasks, and shifts around with each show: sometimes you’re a writer, sometimes an actor, director, technician, or shadow-puppeteer. The whole thing ends up being this wonderful process of collaborative problem solving: How do we make what we want to make with what we have? Those limitations spark more interesting ideas than the ones you’d have if you could just pay problems away.

I was introduced to Choice of Games by a friend who had worked for the company as a cover artist. I’d never written anything like this before, and it was a steep learning curve, but the Choice of Games forum and community is such a vibrant scene of supportive people that it’s been really exciting to work on. As a writer, it’s so easy to get sucked into the lonely process of submitting to distant strangers and contests, rarely getting any feedback on your work. The opportunity to have people engaged and willing to respond to your drafts is an invaluable resource, which was my favorite part of working in theater.

What did you find most challenging about the game design and using ChoiceScript to craft a narrative?

Pretty much everything? I was so proud the day I finally submitted a full draft that you could play through from beginning to end that it’s fueled me through the whole editing process since. Having finished a CoG game now, it’s amazing how many tips and tricks you pick up along the way that would change how you approach writing another game.

There were a lot of really fun challenges purely at the level of the prose. For one, second-person/present tense is such a fun, propulsive voice to write in. As someone who didn’t grow up with tabletop roleplaying games, it’s a relatively new voice for me.

Also, as a playwright, my plays are often structured around reveals and buried secrets. When lights come up on a play, we don’t know the people on stage, and revelations about their pasts, motives, relationships, and shared histories are part of what fuels the drama.

In an interactive fiction novel, the reveal isn’t as useful, because it will only work for the first playthrough. This completely changes the notion of suspense as a storytelling technique–a returning player has already seen behind the curtain. Plus, in the main character’s case, the player needs to know (and decide) all major backstory decisions from the outset, so that they can make informed decisions. This was really fun for me; as a writer I couldn’t rely on old tricks. It feels like I usually write as someone watching from the audience, and this was like going on stage and whispering in the main character’s ear.

Bootlegger is set during such an interesting period in American history. What about the period, and about Prohibition in general do you think modern readers may not know about?

The intersection of coffee and alcohol is really interesting to me. Part of the reason people drank so much pre-Prohibition was because alcohol was one of the only reliably safe ways to drink water. It would be much lower alcohol content than we associate with booze today, but people would drink the entire day. Coffee and tea were new forms of safe ways to drink water, so people went from being mildly drunk all the time to sober and caffeinated. The intellectual and political ramifications of that are massive.

The period is great for anecdotes, and I love all the methods people came up with to get away with drinking. Speakeasies would install levers that, when pulled in the case of a raid, would dump their entire liquor display down a hidden chute, shattering the bottles and draining the booze. Alcohol had been determined to have no health benefits, but during Prohibition that suddenly changed: whiskey could be gotten legally with a prescription for all sorts of maladies.

For me, it’s also a really interesting time of how people respond to a ban. For many, Prohibition was an attempt to stop some truly devastating habits, such as poor workers and farmers blowing their full paychecks on the way home, before even getting to their families. You can see how the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League could see alcohol and the people who sold it as criminal enterprises. At the same time, the complete ban on it meant that many people saw a market, and exploited it ruthlessly. With Bootlegger, I wanted to explore the sudden emergence of a new market that’s illegal, lucrative, and slightly absurd; something that was legal a few short years ago is now a violent, thriving industry.

Do you have a favorite NPC, one you enjoyed writing most?

I’ve never written any kind of gangster story, so writing Capaldi was a lot of fun. Writing a villain in general is a lot of fun, actually, but especially in this case, since Capaldi can be a villain or an ally depending on the play-through. That type of character, alternately frightening and endearing, is so rich and prevalent in gangster movies, and I like that in interactive fiction you might only see someone’s worst side when you’re on their worst side, which is just a terrible place to be. I think one reason we get into stories like The Godfather is because we see two sides of people, while the other characters in the story only see one: loving family member, terrifying murderer. It seems impossible that they can be one person.

If you were transported to the world of Bootlegger, what kind of underground shenanigans would you be best at? Distilling, smuggling, or imbibing?

I think I’d be good at distilling. I know I’d be terrible at being in charge of an operation, I have neither the economic wherewithal or ruthlessness. But I was a barista for a long time, so I think I’d be good at tending a still. I don’t think Prohibition had much of a “craft rotgut” scene, but I imagine I’d be able to get to the point of describing the flavor notes to my customers, which could maybe help me work my way up to get the kind of clients who could afford to care about the quality of their whiskey during Prohibition. But I’m also too trusting, so I’d be very easy to rip off. So, if I could find my way into an operation run by someone like Sam in Bootlegger, who takes care of their own, I’d make a very good worker.

Do you have a favorite tipple or are you a teetotaler?

I do love the occasional bourbon or an old fashioned, but generally I stick with beer.

What else are you working on/working on next, writing-wise?

I’m currently getting my Masters in Political Science, so I’m writing several essays, mainly focusing on the global impact of the film industry. I recently had a staged reading of a new play, Wildlife, which focuses on the illegal wildlife trade, as part of an ongoing project for my classes focusing on climate change. I am also working on an audio drama, called Ambrosia’s Big Break, with the hopes of releasing it in podcast format. Over the process of revising Bootlegger, I’ve had more ideas about things I’d like to do in this medium, so I’ve started to sketch out ideas for another interactive novel. This one would take an interconnected series of science fiction stories I wrote, and adapt them into one big world for the player. It’s one of those narratives that I’ve been attached to for years, but haven’t found the proper form for yet.

#choiceofgames#choice of games#interactive fiction#booknerdlife#books#interactivefiction#bootleggers#new book#new author#fantasy

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

With everything that's been coming out lately about the state of Rooster Teeth and how they have treated their workers, I think it's important to really look at the dynamic between creators and higher-ups in media companies in general.

The workers, the people to are actually making these productions, are often there because they want to make a career out of what they are passionate about. They're creatives, artists, technicians, performers. They're motivated by the desire to collaborate and create art.

The problem is, in a free market capitalist society, for all of that creative work to be worthwhile for these workers, they need to be paid for it. They can't be the creatives they want to be if they can't make it a career. They have bills to pay, they need to eat, they need to go to the doctor and the dentist, etc. And productions of such size as, say, RWBY, need a whole lot of funding.

That's where companies like Rooster Teeth come in, and that's where the problem lies.

Because these workers are so passionate, so motivated to create and be part of big projects like RWBY, media companies know they are ripe for the exploiting. Sure these companies will pay them, but not enough. Sure they'll fund their creative projects, but they'll put excessive work requirements on the workers to try to ensure the project is as financially successful as possible. They'll turn a blind eye to the issues with the culture and dynamic between workers and their supervisors in order to lighten their own workload and responsibility, while placing more and more of exactly that upon those same mistreated workers.

And it's inescapable. I don't have the first-hand knowledge to make this claim for certain, but this is likely how it is as every major media company. Just seeing the controversy surrounding The Owl House, how the passionate people behind that show had their aspirations curtailed by media mega-corporation Disney. How the products of countless creative workers were just dumped by Warner Bros. Discovery for whatever money reasons.

The thing is, really the only way creative workers can make high-budget projects is via companies like this. Beloved franchises like RWBY, The Owl House (and everything Disney releases, tbf), could not exist without the backing of these media companies. It's inescapable.

Nothing will change until more eyes are on these controversies and the culture within media companies like RT, and nothing will change unless we get behind the creatives, the performers, the workers who want to create. The people who work to make your favorite shows, games, films, need more support. These workers need heavily supported unions, these media companies need reform, and us, the fans, need to pay attention.

I love RWBY, I love The Owl House, I love playing Splatoon on my Nintendo Switch. Sure, none of these things would exist without all the money the companies that published those projects put into them. And none of these things would exist if the workers behind them didn't have the love and passion they do for their craft. In the kind of economic system we live under, there's really no changing the fact that both workers with talent, and companies with funding are each required to make things like this. The thing that does need to change is how those companies treat those workers.

381 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Animation Guild parent organization IATSE (International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts) has released a set of 10 Core Principles for the application of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) technology in the entertainment industry.

According to the union, the list was assembled in response to technologies that will “fundamentally alter employers’ business models and disrupt IATSE members’ livelihoods.” IATSE had previously announced that the report was being worked on by a union commission on artificial intelligence.

In an accompanying release, IATSE says that any strategy regarding the rise of AI and ML “must be comprehensive, focused on research, collaboration, education, political and legislative advocacy, organizing, and collective bargaining.”

IATSE International president Matthew D. Loeb said: “With AI, the stakes for IATSE members in all crafts [are] high. There is much work to do, but I am pleased to report the union’s efforts are already well underway.”

The release of the core principles, which can be read in full here, is auspiciously timed. On July 3, IATSE tweeted plans for a new LinkedIn Learning Path (a curated group of videos on the social media platform) titled “Artificial Intelligence 101,” which the organization says was developed to provide IATSE workers with a resource to understand and use AI technologies.

That news went over like a lead balloon with many union members, including those in the Animation Guild. IATSE’s social media pages were inundated with complaints about the program, particularly the choice to feature speakers deeply invested in AI technologies.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Generative AI Copyright Disclosure Act

Representative Adam Schiff (D-CA) introduced the Generative AI Copyright Disclosure Act, a bill to establish transparency with respect to copyrighted works used in building generative artificial intelligence (AI) systems, Tuesday.

The International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) is proud to endorse the Generative AI Copyright Disclosure Act – we thank Rep. Schiff for his leadership on this critical issue and for his partnership, inviting the input of IATSE behind-the-scenes entertainment workers in the drafting of this bill.

Speaking in support of the newly introduced federal legislation, International President Matthew D. Loeb said, “IATSE commends Rep. Adam Schiff for introducing the Generative AI Copyright Disclosure Act. Entertainment workers must have consent over the implementation of emerging technologies in their workplaces and must be fairly compensated when their work is used to train, develop or generate new works by AI systems. This legislation will ensure there is appropriate transparency of generative AI training sets, and would empower IATSE workers to enforce their rights.”

The rapid development of generative AI technologies has outpaced existing law, leading to widespread use of creative content without consent or compensation. This legislation introduces critical measures to protect the intellectual property (IP) rights of creators in the age of AI. It mandates transparency from companies in disclosing the use of copyrighted works to train AI systems, ensuring creators are informed and have the tools to advocate for credit where due.

Maintaining strong copyright and IP laws, and prioritizing the people involved in the creative process, is the primary focus of IATSE’s AI-related political and legislative advocacy. As highlighted in the Agenda des questions fédérales de l'IATSE, absent safeguards to ensure consent, compensation, and credit for the use of copyrighted works and IP, and appropriate transparency of training sets, AI will continue to be used as a sophisticated, deceptive tool for content theft.

“AI developers cannot be allowed to circumvent established U.S. copyright law and commit intellectual property theft by scraping the internet for copyrighted works to train their models without permission from rightsholders. The theft of copyrighted works – domestically and internationally – threatens our hard-won health care benefits and retirement security,” said International Vice President Vanessa Holtgrewe in November at the bipartisan U.S. Senate AI Insight Forum on IP and copyright.

We must improve transparency of generative AI training data sets to protect the rights of working people who power the U.S. entertainment industry. The Generative AI Copyright Disclosure Act will do just that. We look forward to continued collaboration with Rep. Schiff to advance this effort and we urge all members of the House of Representatives to cosponsor this important legislation.

Political and legislative advocacy around artificial intelligence and machine learning are part of IATSE’s broad campaign to address the impact of emerging technologies on entertainment workers. Click here to read IATSE’s Core Principles for Addressing Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Technology.

# # #

L'International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees ou IATSE (nom complet : International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States, Its Territories and Canada) est un syndicat représentant plus de 170 000 techniciens, artisans et ouvriers de l'industrie du spectacle, y compris les événements en direct, la production cinématographique et télévisuelle, la radiodiffusion et les salons professionnels aux États-Unis et au Canada.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twenty One Pilots’ Josh Dun Builds His Dream Studio, Part 1

Drums rule inside the Boom Boom Room, the new home facility of Twenty One Pilots drummer Josh Dun and his wife, voice artist Debby Ryan.

By: Steve Harvey

Columbus, OH (August 1, 2023)—The Boom Boom Room—Twenty One Pilots drummer Josh Dun’s studio at his new house in Columbus, Ohio—is a visual treat. The bold aesthetic comes from Dun and his wife, actress, singer and voice artist Debby Ryan, whose quirky and eclectic taste is on display throughout their home.

While fitting in with the home’s overall aesthetic, the studio has been primarily designed as a space where Dun can practice and record his drums, both for band projects and his collaborations with other artists. It’s also set up to accommodate visiting musicians and for Ryan to record voiceovers, ADR for film and television, and her podcast.

If you are unfamiliar with Twenty One Pilots, well, where have you been? Since breaking into the mainstream in 2015 with their fourth studio album, Blurryface, the Grammy-winning twosome—drummer Dun and lead vocalist and multi-instrumentalist Tyler Joseph—have been flying high. In early 2018, Blurryface became the first album in the digital era to achieve RIAA gold, platinum or multi-platinum status for each of the 14 songs. One year later, the album’s 12-song predecessor, 2013’s Vessel, repeated the feat, making the duo the first artists in history to have every song from two separate albums certified at least gold by the RIAA.

The next full-length, 2018’s Trench, became Twenty One Pilots’ third consecutive platinum-certified album, cementing their success. Then along came Covid-19, and the hard-touring duo was suddenly grounded. Their most recent album, the low-key Scaled and Icy (a play on “scaled back and isolated”), was written and largely produced by Joseph at home in Columbus during the pandemic, while Dun, in a first for the drummer, engineered his contributions in the studio at his and Ryan’s house in Los Angeles.

Which brings us back to the Boom Boom Room. After seven years in L.A., Dun and Ryan made the decision to buy a house in Dun’s hometown of Columbus, where Joseph was also born and still lives. “Josh called me and said, ‘Hey, I just bought a house in Columbus. We should build a studio,’” recalls TJ Bechill, co-founder/senior technician with NEAT Audio.

GETTING THE BAND TOGETHER

Bechill goes way back with Twenty One Pilots. In 2012, working as a studio-focused senior sales engineer at Sweetwater Sound in the artist relations division, he saw the band on television, tracked down their FOH engineer and introduced himself. To cut a long story short, the relationship snowballed, eventually leading Bechill to set up NEAT (Next Era Audio Technologies), which specializes in redundant live playback rigs. “By the time I left Sweetwater in 2018, I had over 300 national tours that I was either selling or building rigs for,” he reports.

Along the way, Bechill, who also works for Fender, has held a variety of touring and technical positions with the band, has equipped and managed two studio build-outs for Joseph, and supplied all the gear for Dun’s L.A. studio. As a result, when Dun got in touch about building a facility at his house in Columbus, Bechill knew just who to call first—Indiana-based acoustical consultant Gavin Haverstick of Haverstick Designs, who designed and built both of Joseph’s studios, one in a basement, one in a sunroom.

Haverstick recalls walking through the prospective new house with the couple: “I’m in Indianapolis, so I drove over to tour the house with Josh and Debby. They were wondering if the place would work. Luckily, there was a ready-made spot for the studio in the basement.”

You’ve probably seen rooms designed by Haverstick, perhaps without realizing it. He’s built any number of facilities for commercial, educational and HOW clients, as well as musicians such as Tori Kelly, Polyphia’s Tim Henson, Brooklyn Duo, David Crowder and Luca Pretolesi (Studio DMI). However, unlike some acoustic architects, he doesn’t follow a template or impose his aesthetic on his clients. “We love the fact that all of our rooms look different, because every one of our clients is different,” he says. “We create rooms that inspire; that’s our mission statement.”

It follows that one of the first things Haverstick does is find out what inspires his client. “Josh would share Instagram posts with me and say, ‘I like this aspect of this studio,’ or, ‘Do you think we could do the lights like this?’” he says. “The cool part about working with Josh and Debby was that their whole house is unique, kind of out there and quirky. It was fun, because any idea that I had, I knew it wasn’t going to be too over-the-top.”

The walk-out basement space was previously a children’s playroom. To create a control room, Haverstick extended the space and canted out the walls for acoustical purposes. “It’s just nice to have a bigger control room, plus it helps with the low-frequency response,” he says.

Live Sound Showcase: Twenty One Pilots

The geometry of the control room’s black and gray wall treatments creates the illusion of a larger space. Lines draw the eye to the studio glass and the live room beyond, where a wall of vibrant flowers, the work of Australian husband-and-wife visual artists DABSMYLA, present a colorful backdrop. Haverstick was inspired by the DABSMYLA mural in the high-ceilinged sunroom directly above the roughly octagonal-shaped tracking space.

“I said, ‘Give me 10 extra feet of that image and we can put that on the walls.’ They loved it, and it became a signature part of the live room,” Haverstick says. Matthew Call of Simplified Acoustics handled all the fabric and interior acoustical treatments.

The Boom Boom Room was general contractor Charlie Griffey of Griffey Remodeling’s first recording studio job. Haverstick says Griffey was a joy to work with during the project, which took about a year from start to finish: “Charlie was awesome. He likes to learn, so he would even show up when he didn’t need to be there because he was genuinely curious about how things were going. He took a lot of pride in what he did, and he just nailed it.”

#twenty one pilots#twentyonepilots#josh dun#joshua dun#2023#august#aug#august 2023#aug 2023#august '23#aug '23#interview#boom boom room#drum home studio#drum studio#home studio#text#aug 1#august 1#mix mag#mix magazine#columbus#ohio#columbus ohio#columbus oh#OH#cbus

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nati Davis, a prodigious talent in the realm of music production and audio engineering, has been making waves in the industry with her unparalleled expertise and innovative approach. Born amidst the stunning landscapes of Tirol, Nati’s journey from a renowned ski resort to the bustling streets of Berlin and the serene shores of Madeira has been nothing short of extraordinary.

With a deep-rooted passion for music and technology, Nati’s journey into the world of sound began at an early age. A true technician at heart, she possesses an intimate understanding of every device and plug-in, seamlessly maneuvering through the largest mixing consoles with finesse. Her academic pursuits led her to successfully complete her studies in Audio Engineering, specializing in Electronic Music Production, and furthering her expertise with three semesters in the Audio bachelor’s program.

Nati’s expertise extends beyond the confines of traditional music production. Her main forte lies in recording and sound design with modular synthesizers, a realm where she truly shines as a trailblazer. Collaborating with various singers and artists, she has carved a niche for herself, weaving sonic tapestries that captivate audiences worldwide.

But Nati’s journey is not merely confined to the studio. With a penchant for visual storytelling, she has ventured into the realm of music videos, further expanding her creative horizons. From the vibrant shores of Ibiza to the snow-clad landscapes of Ischgl, Nati’s experiences have shaped her into the multifaceted artist she is today.

After honing her skills in various industries, including information technology and the sports sector, Nati took a leap of faith and founded her own company in 2001, showcasing her entrepreneurial spirit and business acumen. By the age of 28, she had already established herself as a self-made success, a testament to her relentless determination and unwavering passion.

In 2012, Nati embarked on a new chapter in her journey, relocating to Berlin where she set up her own studio as a producer and recording engineer. Today, she continues to push the boundaries of creativity, collaborating with artists and studios across Berlin while splitting her time between the vibrant cityscape of Berlin and the tranquil shores of Madeira.

Nati Davis’s eclectic mix of talent, experience, and unwavering dedication sets her apart as a true visionary in the world of music production. With each endeavor, she continues to redefine the boundaries of creativity, leaving an indelible mark on the industry.

For a glimpse into Nati Davis’s sonic universe, visit her Spotify profile:

View On WordPress

#Album#artists#EDM#EP#hip-hop#HipHop#Hollywood Music#Interview#Music Interview#press release#songwriter#soundlava

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A 160-Year-Old Cézanne Painting Hid a Secret

Cincinnati Art Museum's chief conservator Serena Urry was conducting a routine inspection of the institution's prized Paul Cézanne painting "Still Life with Bread and Eggs" when she noticed something "odd."

For an artwork dating back to 1865, the appearance of small cracks was no surprise. But they were concentrated in two specific areas, rather than distributed evenly across the canvas. What's more, they revealed tiny flashes of white that stood out in contrast to the brooding palette of the French painter's so-called "dark" period.

"I thought there might be something underneath that we should look at," Urry said in a video interview.

The conservator asked a local medical company to bring a portable X-ray machine to the museum, where a technician scanned the 2.5-foot-wide oil painting in several parts. As Urry stitched the series of images together digitally using Photoshop, she saw "blotches of white" that indicated the presence of more white lead pigment.

"I was trying to figure out what the heck they were... then I just turned it (90 degrees)," she recalled. "I was all alone but I think I said 'wow' out loud."

When the scan was rotated vertically, an image of a man emerged, his eyes, hairline and shoulders appearing as dark patches. Given the figure's body position, Urry and her museum colleagues believe it to be Cézanne himself.

"I think everyone's opinion is that it's a self-portrait ... He's posed in the way a self-portrait would be: in other words, he's looking at us, but his body is turned.

"If it were a portrait of someone other than himself, it would probably be full frontal," she added.

Should that be the case, it would be among the earliest recorded depictions of the painter, who was in his mid-20s when the still life was completed. Cézanne is known to have produced more than two dozen self-portraits, though almost all of them were completed after the 1860s and were largely executed in pencil.

"We are at the outset of the process of discovering as much as we can about the portrait," said Peter Jonathan Bell, the museum's curator of European paintings, sculpture and drawings, over email. "This will include collaborating with Cézanne experts around the world to identify the sitter, and undertaking further imaging and technical analysis to help us understand what the portrait would have looked like and how it was made.

"Stitched together, this information may add to our understanding of a formative moment in the early career of this great artist."

Unanswered questions

Part of the Cincinnati Art Museum's collection since 1955, "Still Life with Bread and Eggs" was painted in a realist style — inspired by the Spanish and Flemish Baroque periods — that Cézanne deployed early in his career. He later developed a more colorful aesthetic under the guidance of Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro, before spearheading the more structured style of the post-Impressionist movement.

In the mid-1860s, Cézanne was developing a new coarse painting technique, often using a palette knife to apply color. But whether his hidden portrait was an experiment gone wrong, or whether he simply reused an old canvas to save money, remains a matter of speculation.

Another possibility, Urry ventured, is that the painter suddenly felt inspired and "needed a canvas" — a theory supported by the fact that he appears not to have removed much paint before starting work.

"It's pretty clear that he didn't scrape it down," Urry explained.

Many other questions remain, including the colors Cézanne used and how complete his original portrait was. Museum experts hope to analyze the painting using advanced scanning processes like multispectral imaging, which might reveal the underlying brushwork by assessing textures invisible to the human eye. X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, meanwhile, could reveal which chemical elements are present and, thus, what colored pigments were used by the artist.

"We're hoping to reach out to colleagues in the conservation and curatorial worlds to see if we can get access to other equipment," said Urry.

For now, however, the museum is looking forward to putting "Still Life with Bread and Eggs" back on display. Since making the discovery in May, Urry has cleaned the painting and thinned the varnish on its surface. It returns to public view, alongside an image of the X-ray, from Dec. 20.

Further scans and analysis could entail transporting the artwork to another institution, presenting logistical challenges and meaning visitors to the museum might miss out on a chance to see one of only two — or arguably, now, three — Cézannes in its collection. "You can't just pop it in your car and drive it to Chicago," Urry said.

"The portrait has been there since he painted it, and it's been there since (we acquired it in) 1955," she added, "so there's no rush."

By Oscar Holland.

#Cézanne#Cézanne 'Still Life with Bread and Eggs' 1865#A 160-Year-Old Cézanne Painting Hid a Secret#french artist#painter#painting#self portrait#hidden painting#art#artist#art work#art world#art news#long reads

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oct. 13, 2022Everything RisesNYT Critic's Pick

Not long into “Everything Rises,” which opened at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on Wednesday night, the bass-baritone Davóne Tines confronts the audience with an uncomfortable declaration.

“I was the moth, lured by your flame,” Tines, who is Black, sings with disdain. “I hated myself for needing you, dear white people: money, access and fame.”

“Everything Rises” is a timely collaboration, created by the Korean American violinist Jennifer Koh and Tines, that interrogates what it means to be a classical musician of color — to have chosen to make a creative life and professional career in a medium and a milieu that are overwhelmingly white, and to have tucked away fundamental elements of their identities in the process. The result of those inquiries is a compact, affecting and meditative multimedia work made entirely by people of color, including the composer and librettist Ken Ueno, the director Alexander Gedeon and the dramaturg Kee-Yoon Nahm.

Koh and Tines conceived this show several years ago. Its debut was originally scheduled for spring 2020, but because of the pandemic it instead premiered this April at the University of California, Santa Barbara. What happened across the United States between those two dates — particularly in terms of racial violence perpetrated against Black and Asian Americans — made the enterprise seem even more pressing.

The work begins with Koh and Tines dressed in typical concert dress: she in a wine-colored gown, crowned with demure dark hair, and he in a tuxedo. But he is also wearing a black blindfold, which leaves him feeling his way across the expanse of the Fishman Space stage at BAM. Early on, the audience sees a video clip of Koh’s winning performance as a 17-year-old at the 1994 Tchaikovsky competition in Moscow, an early highlight of what could have been a traditional career.

Soon enough, however, Koh reveals her true, hot pink hair. Tines puts his customary earrings on. The duo wear fitted black tank tops with voluminous black skirts — a coming into their full selves, and a recognition of the parallels of their individual paths.

Musically and narratively, “Everything Rises” underlines the fact that Koh and Tines, as well as their creative partners, are constantly code switching, depending on where they are and whom they are with. Ueno imaginatively expresses those frequent alternations between ways of being, drawing texts from their experiences and sampling audio recordings of interviews with the matriarchs of their respective families: Koh’s mother, Gertrude Soonja Lee Koh, who fled the Korean War to the U.S., and Tines’s grandmother, Alma Lee Gibbs Tines, a descendant of enslaved people.

Ueno weaves clips of these women recounting chilling, graphic stories. Alma recalls the lynching of one of her relatives — “they killed him and hung him, cut his head off and they kicked his head down the streets” — while Soonja remembers, “I saw people being tortured and people on the trees, bodies hanging on the trees.”

There are also moments of melancholic tenderness in “Everything Rises,” such as in the lullaby-like “Fluttering Heart,” and testaments to enduring resilience. Over the course of the show, Tines and Koh hold each other up literally and figuratively: hearing, acknowledging and amplifying each other’s stories.

Ueno’s score nods to 19th-century Western idioms, traditional Korean music and shimmering contemporary electronica. The effect is not a pastiche, but a sonic code switching. He also allows Tines and Koh — exemplary technicians and artists of profound intensity — to explore their full tonal and textural ranges. Moments of racial violence are evoked by Koh playing growling, guttural scratch tones, often on her open G string, while Tines cycles from his rich basso profundo to an ethereal falsetto. (The day before “Everything Rises” opened, BAM named Tines as its next artist in residence, beginning in January.)

The piece ends with a hopeful original song, “Better Angels,” which is preceded by a particularly haunting sequence. Ueno writes a new setting of “Strange Fruit,” the powerful song, made famous by Billie Holiday, that portrays violence against Black Americans and that, in part, led to Holiday’s prosecution by the U.S. government. It’s impossible not to imagine Holiday’s ancestral shadow as part of this work: Alongside Alma and Soonja, she becomes its third matriarch.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alternative Press interviews Daniel Romano about his prolific career and upcoming new LP ‘La Luna’!

“Romano has released a staggering 16 albums in the past three years as a solo artist, with his whip-crack backing band the Outfit and with various collaborative projects. This fall, he and the Outfit released their most ambitious album to date with La Luna, a prog-infused rock opera that exudes the confidence of a true rock ’n’ roll technician working at the height of his powers.“

https://www.altpress.com/daniel-romano-la-luna-interview/

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

TRON Lightcycle Run from GMUNK on Vimeo.

There’s a power, an elegance, and an electric intensity to the TRON Legacy franchise. The narrative of the TRON world itself integrates the tactile human experience with another realm where data, design, stunning architecture, and mood combine for a thrilling ride through a digital plane.

There’s a personal connection Munky has to the franchise. He spent a year designing the holographic world of the film, contributed to high-level concepts for the video game, and now the key visual and live-action campaign for the Lightcycle Run attraction at Magic Kingdom.

What was exciting for him is to be there along the whole collaborative and evolutionary arc of the TRON world. A new favorite agency Disney Yellow Shoes wrote a very cool script focused on typography and pacing, and brought Munkowitz into the fold to apply his aesthetic to the entire package. This point in the journey, particularly, really got him excited because it was truly the most cathartic and fully fleshed out manifestation of the story at immense scale and physicality; the characters, the environment, and the concept in an immersive experience that culminated in a total thrill ride.

To see the ride at scale and to strategize how to capture it was a fresh challenge. Combining that with the primary focus of telling the human story behind the experience, achieved through the same lens and focus on the stylistic flair of the existing franchise was an absolute treat to work on.

Credit List

Yellow Shoes Creative Group

Creative Director: Monse Valera

Art Directors: Connor King, Jesus Diaz

Writer: Frankie Ainsworth

Producer: Wes Lagattolla

Production Editor: Dan Avola

Account Managers: Bridget Fitzgibbons, Ashley Lollar

Project Managers: Meghan Brown, Megan Reilly

Brand Planning: Jessica Rudis, Emily Zimmer

Yellow Shoes Leadership: Helen Pak, Sally Conner, Amy Foster, Jim Real, Toby Myers, Brian Mountain, Cory Stone

Production

Director: GMUNK

Production Company: JOJX

Director Of Photography: Karina Silva

Line Producer: Jason Haymond

1st AD: Bernie Casser

Second Unit Camera: Scott Jones

Lifestyle Photography: Ben Christensen

Additional Photography: Kent Phillips, Steven Diaz, Abigail Nielson

Park Production Support: Wup Fleming, Boxhouse Productions

Park Operations: Gus Castellanos, Taylor Langlas

Post Production

Editorial: Union

Lead Editor: Jim Haygood

Assistant Editors: Brian Leong, Daniel Luna

Producer: Joe Ross

Post-Production: JAMM Visual

Executive Producer: Asher Edwards

Senior Producer: Ashley Greyson

Motion Designers: Toros Kose, Peter Hergert

Flame Lead: Alex Snookes

Flame Artist: Patrick Munoz

CG Artist: Patrick Manning

Colorist: Adam Scott

Color Assist: Carver Moore

Production Coordinator: Jon Lazar

Music: Da House

Composer: Lucas Mayer

Sound Design & Mix: Skywalker Sound

Lead Sound Design & Mixer: Tim Nielson

Sound Editor: Andre Zweers

Mix Technician: Kristina Morss

0 notes

Text

Commemorative Statues: Honoring Great Leaders with Busts and Sculptures

Commemorative statues have long been a powerful way to honor great leaders and preserve their legacies for future generations. From ancient times to the modern day, these public sculptures serve as physical reminders of the significant contributions made by historical figures. In this blog post, we will explore the importance of commemorative statues, their benefits, and how you can create your own with statues.com.

What Are Commemorative Statues?

Commemorative statues are sculptures created to honor and remember notable individuals who have made significant impacts in various fields, such as politics, arts, sciences, and social justice. These statues often depict the person in a lifelike manner, capturing their likeness and essence. They are typically placed in public spaces, such as parks, squares, and museums, where they can be viewed and appreciated by the community.

Benefits of Commemorative Statues

Preserving History and Legacy

Commemorative statues serve as tangible links to our past, preserving the memory of historical leaders and their contributions. By creating these statues, we ensure that future generations can learn about and appreciate the accomplishments of these individuals.

Inspiring and Educating

Public sculptures of great leaders can inspire and educate viewers, providing them with role models to look up to. These statues can spark curiosity and encourage people to learn more about the individuals they depict, fostering a deeper understanding of history and its impact on our present and future.

Enhancing Public Spaces

Adding commemorative statues to public spaces can enhance their aesthetic appeal and create focal points for communities to gather around. These statues can also become landmarks, attracting tourists and boosting local economies.

How to Create a Commemorative Statue

Step 1: Choose a Subject

The first step in creating a commemorative statue is selecting a subject to honor. This could be a historical figure, a local hero, or someone who has made significant contributions to a particular field. Consider the impact this person has had on your community and how their story can inspire others.

Step 2: Research and Gather Resources

Once you have chosen a subject, conduct thorough research to gather information about their life, achievements, and appearance. Collect photographs, written descriptions, and any other resources that can help the sculptor accurately depict the individual.

Step 3: Select a Sculptor

Choosing the right sculptor is crucial for creating a high-quality commemorative statue. Look for artists with experience in creating lifelike sculptures and a portfolio that demonstrates their skill and attention to detail. At statues.com, we have a team of professional sculptors who specialize in creating custom stone and bronze statues tailored to your needs.

Step 4: Collaborate on the Design

Work closely with the sculptor to develop a design that accurately captures the essence of the subject. This may involve multiple consultations and revisions to ensure the final statute meets your expectations. Provide the sculptor with all the necessary resources and feedback throughout the process.

Step 5: Cast and Install the Statue