#but the series is completed and with a happy ending

Text

the moth and the flame part 9: the yearning

poly!Nessian x f!Reader

summary: after meeting Nesta in a bookshop, you find the darkest parts of yourselves bonding with each other. Naturally, Cassian finds himself entangled with the two of you.

warnings: light smut

a/n: this series is officially completely written, so I'm hoping to post the last parts this month!

series masterlist

You didn’t truly feel like yourself around them anymore. Instead, you’d become the version of yourself you carefully crafted and molded to please them. To make them happy. To your dismay, you hated it, but not as much as you thought you should’ve.

‘A version of you, custom built for Nesta and Cassian,’ you thought bitterly, because apparently who you were before just wasn’t good enough. Would never be good enough. They called it your ‘lowest,’ but you thought they just couldn’t love you when you were yourself.

That, or you were an addict with people pleasing tendencies, leading you right down these lines of thinking. In the end, you supposed there truly was no one but yourself to blame, but it was always much easier for you to blame other people.

The high road was boring, you’d much rather be your chaotic self than a watered down version. With that in mind, you wrapped a jacket around your shoulders and took off into the night. Both Cassian and Nesta were out of town, and you had a few old haunts to track down, perhaps a friend or two who could help you out. You were good for the money, they knew that. It was time to test just how far your partner’s reach went, and just how much influence they’d attempted to extend in order to keep you how they wanted you.

You didn’t make it far. Just seconds after you passed the threshold of your door, feet hitting the landing, the downstairs one slid open and two very familiar scents drifted in. Spring, but winter sunrise and snow chilled wind threatened to transport you somewhere else. The earlier hint of animosity you felt towards them vanished so easily you kicked yourself for it. Trying and failing to summon that back, you slid into your apartment and quickly shed your jacket and shoes.

Questions about what you were planning on doing wouldn’t be good, because you had no solid explanation and if anything they hadn’t let you get away with vague answers recently.

A lump formed in your throat. You were doing the opposite of what you’d vowed not to just moments ago. To keep the peace. To keep them happy. To keep yourself from going over the edge. Two of out three for them, just one for you, and it didn’t seem fair. It wasn’t fair.

Key clicked in the locked, the door swung open, a gorgeous female and male appeared in your doorway.

Swinging around, mouth parted lightly, careful to keep eyes wide, feigning surprise, you found a genuine sort of joy did fill you. They still had that effect on you.

“Hello sweetheart,” Cassian strode in first, Nesta hot on his heels. After kicking his shoes off, he covered the distance between you in moments. His arms felt like home, like safety, like solace. A smaller, but still strong pair of arms wound around your waist from behind.

“We’re happy you’re here,” Nesta whispered, as if they’d been afraid you’d be somewhere else. You didn’t like that. But ... keep the peace, you told yourself, not wanting to lose hold of that genuine joy that had gripped you, you brushed the words off. For them, you’d roll with any waves or punches, give everything you might not get back, do whatever it took to show your love.

For you, love and hatred danced and blurred an already fine line.

It had been so long for the three of you, that when the glances and looks grew bolder, none of you hesitated.

When their grip on you tightened slightly, with a type of longing you didn’t remember feeling before, you leaned into it and let it anchor you. Maybe sex could be a new kind of drug to drag you to new and different highs. The thought was dangerous. Your actions were dangerous. Everything about this reeked of danger but you threw yourself into it regardless.

Cassian’s hand ran down your thigh, pausing to squeeze right above your knee, his finger tips digging in. “Beautiful,” he murmured, almost to himself, as he pushed the fabric of your dress up further, pushing back on your shoulders to splay you out on your bed, not unlike a feast.

Nesta crawled up next to you, her mouth kissing at your shoulder, then your breast, tongue darting at all of the sensitive areas surrounding your nipples except them. Cassian kissed up your inner thigh.

Each movement was so tender, so sweet, and so full of something you couldn’t stand. You didn’t deserve it. You were broken and fucking unworthy. It felt like everything but love, and you couldn’t handle it a moment longer.

“Stop,” you were barely breathing as you said the word, your heart thundering in your chest.

Both froze in place, you slowly sat up, shifting sideways and taking care to avoid any contact with them.

-

Nesta could only watch as you wiggled around them like they were diseased and any touch might kill you.

You grabbed your clothes, throwing them on your body haphazardly, dressing like you were running away from a one night stand.

Never. You’d never shut anything down like this, and selfishly her first thought was what the hell had she done wrong, rather than what you might be going through. Nothing had been aggressive or rough or ... a door slammed. Then another. More clothes rustled.

“I was just giving her a head start,” she heard Cassian say, “but I'm not letting her wander out there alone.”

Her vision wasn’t really there, all she felt was the rejection. “I’ll stay here in case she comes back.”

Not that you’d be able to escape Cassian’s monitoring from the sky, even in you wanted to, but she couldn’t quite track him down with you.

It didn’t feel right, not when she’d already had one foot out the door.

For someone with one foot out the door, she realized she was taking the rejection rather hard.

Letting her nerves steel with a few breaths, she set about straightening up your apartment instead. It would give her something to do, and maybe show you just how little she was moved by your actions.

-

general taglist: @rowaelinsdaughter @bookishbroadwaybish @nestaismommy @erencvlt @book-obsessed124 @callsigns-haze

acotar taglist: @lilah-asteria @yeonalie @I-am-a-lost-girl16

series taglist: @breadsticks2004 @shamelessdonutkryptonite @rowaelinsdaughter @fightmedraco @acourtofbatboydreams @readinggeeklmao @krowiathemythologynerd @kooterz @anxious-study @lilah-asteria @nestaismommy

#nessian x y/n#nessian x reader#poly!nessian#poly!nessian x y/n#poly!nessian x reader#cassian x y/n#cassian x reader#nesta archeron x reader#nesta archeron x y/n#acotar x reader

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

questions

Ridoc Gamlyn x reader (sweetheart!)

Part three of Ridoc and Sweetheart's story

words: 2.9k

🏷: no real book spoilers, this will make more sense if you've read Resson (Garrick's version) but it's not required, set a week or two into Iron Flame, this is a sweetheart chapter so warning for intrusive / self-deprecating thoughts and anxiety spirals, I made a bunch of stuff up about Ridoc's life because RY never told us anything, Rhith being a cool mom, this hasn't been proofread, oops. gonna go have a bagel now byeeee

Rhith had told you that Ridoc would meet you at the gates at eleven — so naturally you’ve been standing there since 10:45, rocking back and forth on your heels and peeling your cuticles.

Why did you agree to do this? Actually, this was your idea — why did you bring it up? What if he’s not going to show up, and you’re just going to stand here for an hour like an idiot?

“Hey! Am I late?” he asks, startling you out of your thoughts. He’s a little out of breath, like he’d ran here, but he offers you a wide smile nonetheless.

You open your mouth to speak just as the bells chime.

“Guess not,” he laughs when they’re done. “You ready to go?”

You nod, stuffing your hands into your pockets so he can’t see the state of your fingers. Thankfully it’s not too hot to wear your flight jacket. This is your first venture into town, and you don’t want to have your relic on display when you’re in a new place — just going is scary enough.

He leads the way — of course he knows where you’re going. He probably goes out every weekend with his friends; another way you’re completely different.

“I figured we could play twenty questions,” he offers. “Get to know each other a little more. You can go first, if you want.”

You take a second to remember how to speak again. “Alright, um… do you have any hobbies?”

“Coming up with jokes is pretty time consuming.”

“And here I thought they were all completely spontaneous,” you say, shaking your head. “Do you write them all down in that fabled diary of yours?”

He laughs. “Would you believe me if I said I didn’t actually have one?”

You tilt your head to the side, considering it. “Only because I don’t see you spending your free time sitting down, writing.”

“You wound me, sweetheart. I assure you, I’m perfectly capable of writing complete sentences.”

“I never said you weren’t. I just said that I didn’t see you doing it.”

“Fair. Tell me about your book,” he prompts. “The one you’re always carrying around.”

“That’s not a question.”

He gives you a sly smile. “Well played. I’ll rephrase, then. What’s the book about? Do you like it?”

“That’s two questions.”

He laughs, warm and full. “I can’t get anything past you, can I?”

“Three.”

“Okay, okay. The first one, then — what's it about?”

“The main character is a trained assassin who is called before the king to join a contest to become his hitman, basically. But the contestants keep getting murdered in the night by some creature that they can’t track down. It’s part of a series, but I’ve never seen the other volumes anywhere. I like to imagine a different ending every time I read it.”

“You’ve read it more than once?”

You ignore the fact that that’s yet another question, answering it without protest. “Yeah. I know that’s dumb, but it was the book I was in the middle of when my life went to shit. It’s technically property of the library in Aretia, but it was burnt to the ground, so I never gave it back.”

Your heart beats a little faster at the mention of your hometown, and you immediately regret bringing it up, but thankfully Ridoc seems none the wiser.

“There’s nothing dumb about it if it makes you happy.”

You’ve just stepped into the tiny restaurant when a man that you guess is the owner sees Ridoc and pulls him into a tight hug. “I was wondering when you’d bring your girlfriend!”

Your cheeks warm, but you don’t correct him — that would be too awkward.

Ridoc doesn’t correct him either. “I set up Ezra here with ice that never melts,” he explains with a smile.

“It’s been a blessing. Keeps everything fresh longer, so I don’t have to waste it. You two sit — I’ll make you something special, on the house.” He disappears into the tiny kitchen in the back, leaving the two of you alone in the nearly-empty dining room.

Ridoc gestures to a table in the corner, away from the door, and you settle into the chair silently. You can’t help but run through Garrick’s mental checklist — your back is to the wall, and you have clear sight of the two exits. You have a knife in your right boot and one in your left sleeve — plus the blunt one laid on the table in front of you. The fork would probably do more damage, though.

“I think it’s your turn.”

“Hm? Oh. Right.” You take a moment to look at him. “Why are you here?”

He gives you a stupid grin. “Because you asked me on a date.”

You roll your eyes. “No, I mean, why Basgiath? Why the rider’s quadrant?”

“Oh, I know. I just wanted to remind you that this whole thing was your idea. But really… probably because I’m an adrenaline junkie who feels like he has to prove to the world that he’s not an idiot. And I’ve always admired the riders and their magic. We can do some pretty cool shit.”

There’s a pause, and his voice softens as he continues. “I know you didn’t want to be here, so I probably sound super ignorant saying all that. I do think it’s fucked up that you didn’t get a choice — and the way that they handled all of it.”

“I respect your answer. It was honest.”

His turn for a question. “How do you feel about it, really, being here? Not here as in here,” he clarifies, tapping the table, “but at Basgiath.”

You look at him for a second. “Is that your question, or…”

“It can be. But if you don’t want to talk about it, we can go back to the dumb ones.”

“No, it’s fine,” you say quietly, thinking for a second. “I’ve accepted it, but that doesn’t make it any less terrifying.”

He’s quiet, giving you space to elaborate — the same way Garrick does; not prying, but silently offering to let you tell him what you’re thinking, if you want to.

“Challenges are the one thing here that doesn’t scare me, because I don’t have to think about it anymore. I know what to do if someone takes a swing at me, and I know how to disarm someone, because Garrick made me practice hundreds of times. But everything else…”

“Is uncertain and unfamiliar, and therefore scary,” he finishes for you.

You’re a little surprised by the gentle tone of his voice, the lack of judgment in his words. “That pretty much sums it up.”

Another pause.

“I’ve had an anxiety disorder pretty much my whole life,” you admit. “I was that kid in school that everyone thought couldn’t speak, because I never talked to anyone, except my siblings. Liam was my first real friend who was my age. He didn’t mind the quiet. We would just sit together, and he’d do his wood carvings while I read my books. That was good enough for both of us.”

“Where are they now? Your siblings, I mean.”

You’re silent for a moment, looking down at the tablecloth and the barely distinguishable pattern of flowers woven into it.

“I know that’s two in a row for me,” he says, backpedaling. “And you don’t have to answer if you don’t want to.”

“I had a brother and a sister. They were eight and ten years older than me, but they were my best friends. I think they knew that I didn’t have anyone my age, so they always let me tag along for everything until they left for Basgiath.”

“They went here?”

You nod. “As infantry. When they graduated, they joined Fen Riorson’s movement, and a few years later, they were executed along with my parents.”

“I’m so sorry,” he says softly. “I shouldn’t have asked.”

Something compels you to keep talking, to push past the awkwardness and condolences. “I don’t mind talking about them. It’s hard, but they were an important part of my life, and they deserve to be remembered. Losing them was devastating, but Garrick and my foster sister helped fill that void.”

You trace a fingernail over one of the tiny flowers. “I think… I think that’s why I kept pushing you away, and why I haven’t really made any friends here. Being marked doesn’t help, but I can never let myself get close to anyone, because everyone I’ve ever been close to has left me, one way or another.”

You can’t bring yourself to say “died” — and that wouldn’t be quite correct, either. Garrick is very much alive, last you’d heard, but he’s at least a twelve hour flight away.

“I’m sorry,” he says softly. “I only met her twice, but she was always kind to me and everyone she met.”

It takes you a second to realize that he means your foster sister — as far as Ridoc and the rest of the school know, she’d died at Resson along with Liam and Soleil.

“She was,” you say softly.

It feels weird speaking about her in the past tense. You know she’s not dead, that she’s safe with Brennan and the elders, but the last time you saw her, she might as well have been — she’d felt so cold, and looked so drained, unable to respond to you or even open her eyes.

She has to be awake by now, starting to recover. She has to push through, if for no reason other than that it would absolutely shatter both you and Garrick if she didn’t.

Ridoc exhales, choosing his next words carefully. “I really am sorry. You shouldn’t have had to go through any of that, especially so young. But for what it’s worth, which probably isn’t a lot — I think you’re handling it all incredibly well, and you’re really brave for it.”

You, handling anything well? and being brave? Yeah, right. You take a sip of water to cover the look of dry disbelief on your face, but he sees it anyway.

“I mean it. Bravery isn’t “never being scared”, it’s “being scared but doing the scary thing anyway”, and you’ve been doing that every day for the last year — for your whole life, honestly. I think that’s admirable.”

You blink at him for a moment, surprised.

“It’s true,” Rhith says gently.

“Thank you,” you say softly — to both of them. “I’ve never thought about it like that before.”

He offers you a soft smile. “I think that’s enough deep questions for now. Thank you for telling me all of that, though. I’m sure it wasn’t easy.”

“It wasn’t,” you agree. “But I feel… lighter.”

“Lighter is good.”

Ezra arrives at the perfect time, holding a tray with two plates of steaming noodles and two glasses of water, placing them in front of you and making a quick exit.

Ridoc brushes a hand against his glass, and you watch the pattern of frost crawl over the edges as it chills itself near instantly. “Want me to do yours?”

You blink, realizing he’s speaking to you. “Sure. Thank you.”

He pushes the cold glass toward you, taking the other and chilling it for himself.

The question comes out before you can think. “How long did it take you to get used to the cold?”

He looks up at you, surprised. “Not long. A week, maybe. I run hot, so sometimes it’s kinda nice.”

You nod in understanding. He’d been warm to the touch when he’d wrapped his arms around you, and you’d melted right into him. That was a first. But so is this, and it seems to be going okay.

You both eat without further discussion, every minute of quiet a little more comfortable than the last. The food is good — better than anything they serve at Basgiath.

“So, where’s home for you?” you ask after a while.

“Deaconshire,” he answers. “My dad’s still out there. It’s been just me and him for a while.”

“Not too far, then,” you comment, not wanting to draw attention to the fact that he hadn’t mentioned his mother.

“Yeah. I’ve thought about going AWOL for an afternoon, just to see him for an hour or two. But at least the letters will arrive fast.”

“Right,” you say softly, pushing the last piece of pasta around your plate idly.

It hadn’t really sunk in yet that you can write letters now, as a second year. You could write to Garrick, but it would be too dangerous to send anything to Aretia, with the professors reading everything to make sure there’s no classified information being spread. You might be able to write to the Duke, and hope he passes it on to the right people, but that would still be deemed suspicious.

Maybe Bodhi could help you.

“Where’d Garrick get stationed?” he asks.

“Samara,” you answer quietly.

He winces, knowing that’s right on the front between Navarre and Poromiel, but he recovers quickly. “He’s with Xaden, right? They’ll take care of each other.”

“Yeah.”

“They’ll be fine,” he reassures. “They were the two biggest, most intimidating dudes in fourth wing. Nobody’s going to mess with them — but if anyone’s dumb enough to try, they’ll get what’s coming to them. And they can definitely kick ass in the air, too.”

He’s right — they’ll be fine.

Probably.

“Yeah,” you say again, hoping it sounds convincing. “They can definitely hold their own.” But against wyvern… what if what happened to Deigh happens to Chradh or Sgaeyl, and there’s nothing they can do?

You force the thought out of your head before the universe can hear it and make it come true.

“You ready to head back?” he asks gently.

You nod in affirmation, and he gets up, finding Ezra. The owner bids him a cheerful goodbye that includes a hearty pat on the back, while you stand by the table and offer him a weak wave and a soft thank you.

The walk back to the school is quiet, only the crunching of gravel under your boots, but this time the silence isn’t as loud.

You’ve already said everything you needed to say, laid all your cards face up on the table and shown them to the other — almost all of them, you think with a little flare of guilt, but there are some things you just can’t tell anyone, for the sake of Tyrrendor in its entirety.

“This one’s mine,” you say quietly, stopping in front of your door.

You call it yours, but it doesn’t feel that way. Just because you sleep here and your stuff is piled up in the corner, yet to be unpacked, doesn’t make it feel like yours, and doesn’t make it feel safe, despite the ward that Garrick had helped you put up before he left for Samara with Xaden.

Ridoc offers you a warm smile. “Thank you for taking a chance on me. I’d really like to see you again, if you want.”

“I’d like that too.”

He lingers, and for a moment you’re worried that he’s expecting something of you, but he remains a few steps away, his hands in his pockets.

“Thank you,” you add. “For today. And for finding me yesterday.”

“Of course, sweetheart. And next time you start to feel that way, you can have Rhith tell Aotrom to get me, okay? You shouldn’t have to deal with that alone.”

“Okay,” you say softly.

He gives you another knee-weakening smile before he heads off, disappearing into a room that must be his — eight doors down, on the other side of the hall.

You make it inside just as the bells strike twelve thirty. The afternoon is still young.

You decide to unpack — starting by shoving the box of your sister’s things into the bottom of the armoire. You’d burned most of her stuff, to maintain the appearance that she’s actually dead, but you and Garrick had both taken some for yourselves. Malek couldn’t get mad about that, right?

You don’t know if you should worry what he thinks or not — you despise him for taking everyone away from you, but you need to remain in his good graces if you want to keep the few people you have left. But you aren’t sure how — it remains unclear what you did, or didn’t do, to deserve that.

“It was nothing you did,” Rhith says gently, startling you. “And you didn’t deserve it.”

“Sorry,” you stammer. “I didn’t mean to project that to you.”

“We’ve talked about the apologies, sweet one,” she prods. “They’re never necessary.”

“Sor—” you stop yourself before you can finish the word. “I’ll work on that.”

She changes the subject for you. “I’m proud of what you did today. I know that was difficult for you.”

“It’s easier with him,” you say quietly. “I don’t know why, but it is.”

“Many things don’t require explanation. It is enough to simply appreciate them.”

Spoken like a true green. “I wish I could be as logical as you,” you sigh.

“There is value in both logic and emotion, but there is a balance to be found between them.”

You sit with the statement for a moment as you start to fold the laundry you’d shoved into a bag and dragged up the stairs when you’d moved, trying to smooth out the wrinkles to no avail.

“What do you think?” you ask. “about him, I mean.”

“I think he has a good heart. He genuinely cares for you, but it is your decision whether to trust him or not. And even if you do, there are some things that he can never know.”

“Yeah,” you say softly. “I know.”

“I’m proud of you, my girl.”

You’re a little bit proud of yourself too.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

As someone who's a fan of Good Omens (the show and the book), in the wake of the revelations about Neil Gaiman I want to say that the victims' wellbeing is more important than any closure from the completion of Series Three. If the showrunners find a way to remove Gaiman and complete it without any input from him, that would be a blessing. But if it never sees the light of day, I'll accept it.

We had one amazing first series that was based on the novel which Terry Pratchett's daughter has stated was 75% his work. The second series ... well, no matter how good you think it is (or isn't), it feels like an impostor now - a way to string out the story and keep fans on the hook with a cliffhanger ending before rewarding us with a final series based on some alleged ideas that the two authors once had for a sequel. For me, I think I can be OK without it.

I'm angry and disgusted with Gaiman but I realised that I don't feel sad. For his victims, yes. For other fans who lost faith in an author they loved, yes. But not for myself as a fan. Because as good a writer as he was, his own books were never, unlike Terry Pratchett's, up there with my favourites. And that's because, ironically, Gaiman fails at writing happy endings.

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why does tsukasa seem to not care much about himself?

I had a hard time figuring out what you meant by this because to be honest, I don’t focus on the Yugi twins as much as some of the other characters. I still try to read analyses on them and understand them, and I have been talking a lot abt Tsukasa lately, but I haven’t rly grasped their characterization as quickly as I did with some of the others

However, after giving it some thought I believe you’re referring to scenes like these

If this is what you mean, then the explanation is that Tsukasa simply doesn’t want to exist. He is a yorishiro and existence for them is essentially hell, just look at what Sumire went through being stuck in a time loop for 100 years. It is not a reach to assume Tsukasa went through something similar, seeing as he alludes to being trapped in a place before escaping near the start of the series when we first meet him. He reached out to Hanako for years, but Hanako never answered any of his calls. So Tsukasa wanting to be destroyed isn’t really out of any self-sacrificial nature, it would be a peaceful ending for him. He’d be able to move onto the afterlife, or otherwise accomplish any conniving goals he might have with the entity (idk as I said, not a Yugi twins expert)

He views Hanako as selfish for wanting to hold onto the people he loves at the expense of their wellbeing. Part of Nene’e fate is to die young, it’s sad but that is the natural path her life is meant to follow. She herself even tries to come to terms with this and make peace with it, but Hanako won’t let her. He loves her, so he wants her to live a long and happy life. This is completely understandable, but it is also selfish. It is part of human nature to be selfish, and part of Hanako will always be tied to the human boy he once was. Selfishness isn’t always bad, sometimes it’s necessary. But from’s Tsukasa’s perspective, Hanako is robbing Nene of an escape

Tsukasa makes this a personal issue because Hanako treats him the same way. It would be objectively better and more natural for him to let Tsukasa go, especially if the theories abt him killing Tsukasa to free him from the entity are true. That is what Tsukasa wants, to be free, to no longer be a yorishiro. But Hanako is selfish, and he loves Tsukasa too much to grant him freedom

Now, if you’re talking about Tsukasa’s lack of self-care in regards to Hanako “hating” him, that’s a bit different

Tsukasa seems to conceptualize relationships in a very black and white way. You either love someone, or you hate them. He’s interested mainly in how other people feel and react to things, so he’s constantly asking them how they feel about others. I don’t think he differentiates much between platonic love and romantic, it is simply “love vs. hate” to him. The two are opposites and cannot intersect

The most genuine statement I could possibly make about Tsukasa is that he loves his brother. Both versions of him, no matter how you interpret his current existence. The possessed Tsukasa we know now is the one who grew up with Amane, he spent ten years of his life with him whilst Baby Tsukasa only knew Amane for three. Ofc that was still his brother so time isn’t rly relevant to how much love/attachment Amane still holds for the original version of Tsukasa, but that doesn’t change the fact that the brother he knew for most of his life was the possessed Tsukasa. They shared holidays and birthdays together, lived together, walked to school together every single day. Through and through, they are brothers and it would be impossible for Hanako not to see him that way, even if he claims not to. It must be a complicated situation for him, on one hand he grew up with this Tsukasa but on the other he blames this Tsukasa for the old one’s disappearance

Back to how Tsukasa feels, he loves Amane fully. He does describe them as rivals, so I would say the feelings are complex on his end as well, but overall he loves his brother. He loves his brother so much that he doesn’t care if Amane hates him. And he must, he threw him across the room once when they were kids when Tsukasa was bothering him. He knew something was off when Tsukasa returned, and his attitude towards him likely reflected that throughout the 10 years they spent together. He killed him, he freezes up when he sees him, he consistently sides against him. For a character that views love in black and white terms, that sure looks a lot like hate. He recognizes that Amane is sad without him, but he also understands that Amane hates him. At least, from Tsukasa’s perspective, that’s what it looks like

But Tsukasa’s love for Amane is unconditional, he doesn’t really care if Amane hates or loves him. Baby Tsukasa says he wants Amane to be an astronaut with their parents, somewhere far away from him so Tsukasa can never make him upset. He believes Amane hates him, but he doesn’t care as long as Amane is happy. That’s all he wants, for Amane to be happy. His brother is the most important person to him, as long as Amane is happy he doesn’t care what happens to himself. Until it reaches a breaking point ofc, and Tsukasa realizes that the best situation for everyone would be for him to disappear

I’m pulling a lot of this out of my ass so I apologize if I got any information incorrect! Also just to be clear I don’t mind being asked about the Yugi twins at all, people were asking me a lot about Tsukasa yesterday so I get why the questions keep coming. Just beware that I am a self-proclaimed Not Expert lol. I do plan to look more into them whenever I start that series of character analyses tho so stay tuned for that

#tbhk#toilet bound hanako kun#jibaku shounen hanako kun#jshk#ask#ask me anything#tsukasa yugi#amane yugi#hanako kun#yugi twins#yugi brothers#analysis

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

can you tell esper is uhhhhh. ill?

got tagged by @beecreeper for the character insp meme! (check out his here!!) this was a lot of fun, there are a couple of honourable mentions i'll get into under the cut, along with some elaborations for the curious.

list of names, L > R

1: harrowhark nonagesimus -- the locked tomb saga

2: isaac -- castlevania (netflix series)

3: cole -- dragon age: inquisition

4: blackbeard -- our flag means death

5: (bingo free space)

6: seven of nine -- star trek: voyager

7: katya zamolodchikova -- real life / unnnhhhh

8: paul muad-dib atreides -- dune

9: maomao -- the apothecary diaries

1: harrowhark nonagesimus -- the locked tomb saga

if you've read the locked tomb, this one's pretty self-explanatory. but i took a lot of inspiration from harrow's grief-sodden religious zealotry for esper's pre-tadpole self, and i think about harrow the ninth every time i write from esper's perspective during the events of the game. it's the amnesiac goblin madness for me. esper would also absolutely put their bone marrow into a soup to kill someone if that was something they could do. they're extra like that

2: isaac -- castlevania (netflix series)

i just fucking love isaac, man. he's such a fascinating character, taken from a place of pain and degradation into the service of a mad god-figure hellbent on destroying humanity, then banished and forced to just. figure out for himself what he wants to do with his life. and it turns out that what he wants to do is relate to the hellbeasts he raises to use as soldiers, and let them try to eat strawberries and live in houses for a change, take a chance at living as something other than vessels of violence. i love him. that's really all esper wants, too -- to find a peaceful existence after a lifetime of pain and brutality and monsterhood.

3: cole -- dragon age: inquisition

cole is such a vibe. he lives in the attic staring unsettlingly at people and reading their minds and exhuming their pain so he can help them with it, including with his knives. he has that unearthly creepy vibe that esper projects, as well as their tendency to poke around in people's private emotions and their slight uncanny distance from human morality and ethics. making cole more human also ends up around the same for esper -- cole is never quite all the way there, but happy to be truly Among the people whose souls he reads and finally able to experience those things for himself.

4: blackbeard -- our flag means death

apart from the leather and queerness and propensity for violence, blackbeard was also a big influence for esper's journey from "yeah, this violence thing is fun for me, besides it's not like i can Leave this life, i'm stuck here so i might as well enjoy it" to "actually even though it's fun it's also exhausting and all i really want is peace. maybe even a monster like me can love and find a community that loves me."

6: seven of nine -- star trek: voyager

god, where to start? "i was a child who was raised to be perfect, my humanity and individuality were completely overridden and my very body was used as an object for unimaginable violence, and now even though i don't know how to be a Person anymore, i'm cut off from everything i've ever known and i don't know what to do." and now, like seven, esper is just trying their best to build a personality out of the leftover scraps they have with the help of their crew of misfits and weirdos. also, perpetrator trauma -- like seven, esper doesn't feel Guilty about their past actions, but it does haunt them, and they don't really know what to do with it. also, i didn't mean for the two images of esper and seven here to make them look exactly the same, but hey.

7: katya zamolodchikova -- real life / unnnhhhh

this one's more of a bit. i watch unnnhhhh with my wife a lot, and every now and again katya will just say something that makes us both go "that's esper-coded". she has that slightly imperfect balance of genuine darkness and unhinged silliness that esper also teeter-totters between, which results in a specific kind of charisma that you kind of have to see to understand.

8: paul muad-dib atreides -- dune

esper's pre-durge and pre-tadpole backstory draws a fair bit of inspiration from paul's narrative arc lmao. he starts out life as a male heir to a bloodline of female psychic specialists, trains with them, and ends up sacrificing his humanity to fulfil a violent divine path pre-ordained for him. real evil messiah hours. esper has way fewer qualms about killing from the start, and the match isn't perfect, but this is an inspiration, not a stencil.

9: maomao -- the apothecary diaries

another weird one, but probably the most purposeful inspiration on the board here. when i was first playing as esper and trying to sort out their personality, i was also watching apothecary diaries, and maomao's feline predilections and sense of mischief and flawless composure and cunning without ambition had me completely enraptured, so i thought, what the hell. she also shares some backstory elements with esper as the [spoilers] bastard daughter of a disgraced but extremely talented courtesan and a creepy war tactician. like esper, maomao just wants to keep her head down and make enough money to fund her special interests. they also both drink poison for fun (at least, esper does pre-tadpole). i think the main thing they diverge on is that esper thinks poison is for basic bitches.

honourable mentions

jimmy "pickles" hoffa -- jimmyhoffathecat

just look at him. that's an esper. photo credit here

tilly -- my parents' house

pretty self-explanatory for any cat owners out there. esper acts like a cat in general, but they specifically act like this cat. she's so influential and talented and perfect.

towa "murase" -- slow damage

this one is an honourable mention instead of being on the board because i didn't meet towa slowdamage until like 3 weeks ago (well after esper was already realized), but the two of them have so many specific things in common it's actually ridiculous. convergent evolution at its finest.

fenris -- dragon age 2

esper and fenris have very little in common story- or personality-wise, but i can't deny that he was a huge visual influence, especially for pre-tadpole esper. i mean, come on. look at him.

yelena belova -- black widow, hawkeye

i'm not much of an mcu person, but the concept of the black widows in general did influence a lot of esper's pre-durge backstory, and i like yelena. she's like a more charismatic and more down-for-murder natasha. she's not a specific inspiration for esper as a character, but they do have a rhyming vibe.

selcis aureus, umbras heltor -- exodusbound

hello, it's fantrolls! i disqualified selcis and umbras from the inspboard because they're literally other ocs i had a hand in creating, and a lot of the things they have in common with esper aren't public, but they both did (and exodusbound did in general) have a lot of influence on esper as a character. i can't help that i like themes of alienation and life persevering in spite of it all in my characters. art shown here by my wife barbelzoa!

espurr -- pokemon

literally a pokemon, not a character. special place in my heart though because i literally named esper after this thang when i first made them in the character creator. they just had the same dead eyed stare and psychic magic, so i went, yeah, that'll do.

thank you so much for reading this much if you did!!!!!

#loquor#esper#bg3 durge#tag game#the dark urge#bg3 oc#not tagging all the other characters. not interested in clogging tags#OH also#forgot to tag people. idk do this if you want to

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

I love how House is a much better parental figure for Chase than his actual parents,even tho he's a disaster. The bar is so low...

The bar is subterranean. And I think the funny thing is, I don’t think either of them would label their relationship as such: Chase kind of does this with every authority figure he runs into (sucks up to them and tries to get them to like him); House resists every relationship that isn’t on precisely his own terms.

I was thinking just the other day about Human Error vs the Nobody’s Fault/Chase duo. A bit running theme of House is that he hates change. He lives in the same apartment, drives the same car, plays the same guitar. What relationships he has are grandfathered in: he’s known Cuddy on and off since med school, Wilson for a decade at the series start. He had One Relationship with Stacy. He does not generally seek new friends or romantic partners.

And House when called on this gets pretty contrary, of course. He buys a motorcycle. He buys a new guitar. He… fires Chase. And that’s an interesting decision to me, because it really is out of nowhere. House is told he’s struggling to let Foreman go, to let things change, so he proves he’s fine with change by… firing Chase. It’s not because he actually hates Chase; I’m not arguing they’re bffs or have a reciprocal father-son thing at this point. But he’s had Chase the longest.

And the point comes up again in Nobody’s Fault. Cofield practically starts his conversation with Chase with: you’ve worked with him longer than anyone. He brings the point up again with House:

COFIELD: He's your friend, and he's not well.

HOUSE: He's a coworker.

COFIELD: Coworker whom you've known for almost ten years who nearly died and who's still scared he may not walk.

(earlier:

COFIELD: So your testimony is that Dr. House's complete lack of concern is evidence of his deep concern?

)

And yes, sure, knowing someone ten years is enough in itself. But again and again for House, that’s a big deal. That’s… Wilson in S1. Chase has been part of House’s life for a decade. House fired him and he came back. I’ve talked before about how, to Chase, House is the one constant in his life, the one person who approves of what he does and takes him back and wants him around. But it really does go both ways. No, Chase isn’t the only person House has, or the most important person in House’s life. But Chase got fired, and he came back. House punched Chase and immediately regretted it, and Chase didn’t press charges or hold a grudge.

The thing is, House really doesn’t treat Chase like a peer or an equal, and Chase doesn’t try (unlike Foreman and Cameron) to be treated as an equal. I think that’s why their relationship has such father-son vibes; they’re both seemingly pretty happy with the weird employer/mentor/approval seeker relationship they ended up with. But on other levels, they’re very close. Chase gets House, and while in some ways he does seem to idealize him (Chase consistently — and very interestingly given his own history — ignores and enables House’s addictions), he neither idealizes House into a polish or into a monster: he is very good at reading House. They’re both very observant, they both hate opening up, they have deeply parallel histories that the show eventually leans into. Chase was not the first fellow House ever had, but he is the first one that stuck. The first one that stayed.

House can’t admit that means something, but Chase doesn’t need him to, because Chase knows how House thinks. Chase is lonely, S8 drives home he’s lonely and stuck and wants change (and will never get it): House, in his way, always makes it known he notices and cares. They’ve been in one another’s lives for ten years.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

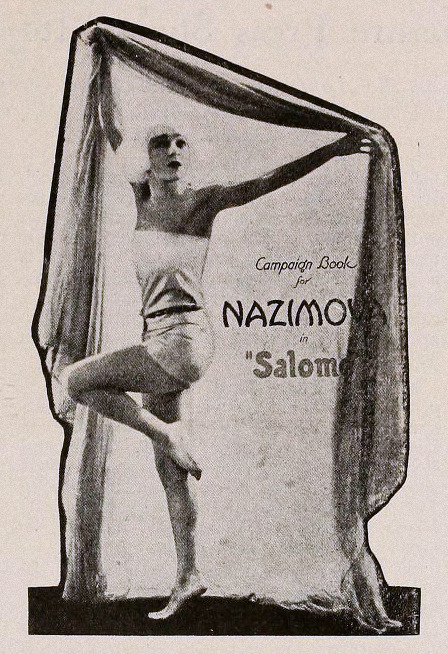

Cosplay the Classics: Nazimova in Salomé (1922)—Part 2

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

As the studio system emerged in the American film industry at the start of the 1920s, many of the biggest stars in Hollywood chose independence. Alla Nazimova, an import from the stage, was one of them. In 1922, she made a series of professional and creative decisions that would completely change the trajectory of her career.

In part one of CtC: Nazimova in Salomé, I described how Nazimova’s independent productions were shaped in response to trends and ideas surrounding young/independent womanhood in America after World War I and the influenza pandemic. Here in part two, I’ll fit these productions, A Doll’s House and Salomé, into the broader context of the big-money business of film becoming legitimate in America.

While the full essay and photo set are available below the jump, you may find it easier to read (formatting-wise) on the wordpress site. Either way, I hope you enjoy the read! Oh and Happy Bi Visibility Day to all those who celebrate!

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

Artists United? Allied Artists and the Release of Salomé

When Nazimova made her screen debut in War Brides (1916), the American film industry was undergoing a series of formative changes. Southern California became the center of professional filmmaking in the US—fleeing New Jersey (where War Brides was filmed) largely because of Thomas Edison’s attempts to monopolize the business. Preferences of audiences and exhibitors shifted away from one and two-reel films and towards feature-length films. The Star System emerged in full force. Nazimova soon relocated to Hollywood, signed a contract with Metro, and reaped the benefits of this boom period for American film artists.

The focus on feature-film production and the marketing of films based on the reputations of specific filmmakers or stars required a greater initial outlay of resources—time, money, and labor. But, it also paid dividends—the industry quickly grew into a big-money business. The underlying implication of that is that a larger share of the profits were shifted from the people doing the creating (artists and technicians) and towards other figures (capitalists). In practice, this also meant film companies would become eligible for listing on the stock exchange and could secure funding from banks and financial institutions, both of which were rare or impossible before the mid-1920s. The major players on the business end of production, distribution, and exhibition, therefore, wanted to consolidate their power and reduce the power and influence of the filmmakers.

To illustrate how momentous this handful of years was in the history of the US film industry, allow me to highlight a few key events. Will Hayes’ office was set up in 1922 to make official Hollywood’s commitment to self-censorship. Eastman Kodak introduced 16 mm film in 1923, a move which, while making filmmaking more accessible and affordable, also widened and formalized the division between the professional industry and amateur filmmaking. Dudley Murphy’s “visual symphony” Danse Macabre[1] was released in 1922—considered America’s first avant-garde film. Nazimova’s Salomé was considered America’s first art film from its initial release in 1923. That these labels were deemed relevant in this period illustrates the line being drawn between those films and film as a conventional, commercial product. The concept of art cinemas in the US was first proposed in 1922 spurring on the Little Cinema movement later in the decade.

from Danse Macabre

from Salomé

As any industry matures, both the roles within it and its output become more starkly delineated. That is to say that, as the US industry began differentiating between art/avant-garde/experimental film and commercial film, the jobs within professional filmmaking also became more firmly defined. Filmmaking has always been a collaborative art, but in the period prior to the 1920s, it was common for people in film to do a little of everything. As a result, what sparse credits made it onto the final film didn’t necessarily reflect all of the work that was done. To illustrate this using Nazimova,[2] at Metro, she had her own production unit under the Metro umbrella. While her films were “Nazimova Productions,” she didn’t have full creative control of her films. However, Nazimova did choose her own projects, develop said projects, and contribute to their writing, directing, and editing. When those films were released, aside from the “Nazimova Productions” banner, her only credit would usually be for her acting. Despite that impressive level of creative power, the studio still had the ultimate say on whether a film got made, and how it would be released. As studios grew and tightened control of their productions, this looser filmmaking style became much less common.

The structure of the industry at this time was roughly tripartite—production, distribution, and exhibition. Generally speaking, the way studio-made films traveled from studio to theatre—before full vertical integration—was that the production company would make available a slate of films of different scales. (Bigger productions with bigger names attached would have a special designation and come with higher rental fees.) Famous Players-Lasky was the biggest production house at the time, though other studios, like Metro, were quickly catching up. Distribution companies would then place this slate of films on regional exchanges, centered in the biggest cities in a given region. Exhibitors (this could be owners of chains like Loew’s in the Midwest and Northeast, the Saengers around the gulf coast, or individual theatre owners) could then rent films through their local exchanges. (This was an ever-shifting industry, so this process was not true for every single film. This is only meant as a quick overview of the system.) As the 1920s wore on, exhibitors began entering the production arena and producers further merged with distribution companies and exhibition chains. Merger-mania was the rule of the day.

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

As merger upon merger took place and a handful of businessmen tried to monopolize the industry, American filmmakers responded by championing the artistic legitimacy of filmmaking in the US. Leading this charge were the very filmmakers on whose backs the big business of film had been built. As noted in Tino T. Balio’s expansive history of United Artists, The Company Built by the Stars:

…Richard A. Rowland, president of Metro Pictures, proclaimed that ‘motion pictures must cease to be a game and become a business.’ What he wanted was to supplant the star system, which forced companies to compete for big names and pay out-of-this-world salaries for their services. Metro, he said, would thenceforth decline from ‘competitive bidding for billion-dollar stars’ and devote its energies to making big pictures based on ‘play value and excellence of production.’”

It’s notable for us that these ideas were espoused by Rowland, head of the studio where Nazimova was currently one of those “billion-dollar stars.” (“Billion-dollar” is obviously a massive overstatement.) It was a precarious time for any filmmaker who cared about the quality and artistry of their work. It was this environment that birthed United Artists, a new production company built around the prestige and reputation of its filmmakers, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, and D.W. Griffith. As the statement announcing the formation of UA detailed:

“We also think that this step is positively and absolutely necessary to protect the great motion picture public from threatening combinations and trusts that would force upon them mediocre productions and machine-made entertainment.”

It’s an accurate assessment of industry trends at the time. If the desired product is a high-quality feature-length film, production is necessarily more expensive. As the UA statement intimates, monopolizing the entire industry and sacrificing quality for quantity to fill the exchanges and theatrical bills was the studio heads’ solution to rising costs. Not a great signal for filmmaking as art in America.

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

So, Nazimova was in good company when she chose to go independent, believing in film as art and that American moviegoers deserved better than derivative, studio-conceived films. Some of the other artists who went independent included George Fitzmaurice (one of the most revered directors of the silent era, though most of his films are now sadly lost), Charles Ray, Max Linder, Norma Talmadge (in alliance with Sam Goldwyn), and Ferdinand Pinney Earle (whose massive mostly-lost artistic experiment Omar Khayyam, I profiled in LBnF). If these filmmakers shared the motivation of UA to create higher-calibre productions, where would the money come from? For Nazimova, the answer was her own bank account.

In 1922, Nazimova’s final film for Metro, Camille (1921), was still circulating widely due to the rising popularity of her co-star, Rudolph Valentino, after the release of Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) and The Sheik (1921). While Nazimova had the funds to complete A Doll’s House and Salomé, there was no sure bet for the films’ releases. Nazimova’s initial concept for her independent productions was the “repertoire” film. This scheme would have seen A Doll’s House released as a shorter film with Salomé as a feature and the two could be rented as a package by exhibitors. It was a creative response to growing tensions between producers and exhibitors over a practice called block booking. Block booking was a strategy studios employed to leverage the Star System to its fullest. They would take the most in-demand films associated with the biggest drawing stars and only make them available in a package deal with productions that were perceived as less marketable. Nazimova was aware that her films at Metro had been rented this way (as the special feature). It’s not completely clear from my research if the decision to release Salomé and A Doll’s House as two features was creative, practical, or a combination of the two. The “repertoire” concept may not have gone according to plan, but it was an early indication that Nazimova was well-informed of the nuances of distribution and exhibition.

Nazimova’s need for proper distribution was met by United Artists’ distribution subsidiary, Allied Artists. United Artists’ first few years were a struggle. Fairbanks, Pickford, and Griffith[3] needed significant time and money to finish the high-quality productions that they promised and Allied was their solution. This distribution arm would release the work of other independent talent using the same exchanges as UA, but under a different banner. Though Allied used UA’s exchanges for distribution, the subsidiary had its own staff. Allied having different branding would also protect the prestige of the UA name. (An unkind, but not entirely inaccurate summary: the money your work brings in is good enough for us, but your work is not.) Allied would have a full release slate to generate the revenue that UA needed to remain in operation.

Nazimova was one of the filmmakers who signed a distribution deal with Allied and had reason to regret it—though she and Charles Bryant didn’t openly rag on UA/Allied.[4] Notably, Mack Sennett had arranged the release of Suzanna (1923) through Allied and was vocal about the company bungling its release. Differences over distribution and exhibition would also lead to Griffith’s exit from the company and a major rift between Chaplin and Pickford-Fairbanks. After 1923, Allied reduced its operation, at least in part because of the bad reputation they were garnering with other filmmakers. Despite numerous independents losing money on productions released through Allied, by 1923, Allied had netted UA 51 million dollars in revenue!

Trade ad for Salomé from Motion Picture News, 10 March 1923

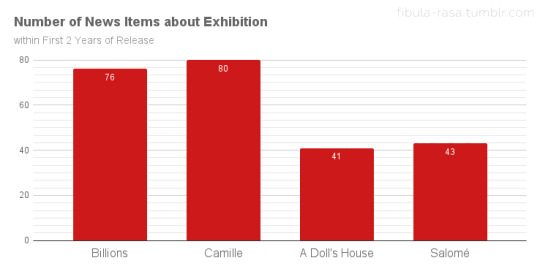

The questionable deals that these independent filmmakers received with Allied are often mentioned in discourse about the period, but very, very rarely does anyone offer details of what Allied’s inadequate distribution looked like. Using the information available to me via Lantern, I collected and analyzed data regarding the release and exhibition of Nazimova’s final two Metro films and both of her Allied films.[5] Looking at the trade publications Exhibitor’s Trade Review, Moving Picture World, Motion Picture News, and Exhibitors Herald, I categorized every item I found about the release or exhibition of Billions (1920),[6] Camille, A Doll’s House, and Salomé. The “release” items are primarily advertisements, reviews, and news items about release dates or pre-release screenings. The number of these items for all four films were comparable.

The items in the “exhibition” category, however, reveal a marked difference between the Metro and Allied releases. This category includes items like first-run theatre listings, exhibitor feedback, and advertising advice for theatre owners. Only counting exhibition items from the first two years (24 months) from the initial release of each film, Billions and Camille had twice as many items as A Doll’s House and Salomé!

While this isn’t necessarily hard data on how many theatres ran each film, it is a rough indicator of how well the films circulated. This data suggests that neither A Doll’s House or Salomé had distribution comparable to the Metro films. In order to compensate for the Rudy factor—Valentino’s major rise to stardom in 1921—which could have affected Camille’s numbers in a big way, I included Billions as well. Billions was sold as a special (a bigger production with premium rental fees) on Nazimova’s name alone. It was not especially well received. Exhibitors/theatre owners had mixed feelings on the film because Nazimova’s previous film, Madame Peacock (1920), had underperformed. Many exhibitors viewed Billions as an improvement, though it still did not meet their perception of Nazimova’s standard of quality. Despite that, Billions had 76 exhibition-related items across its first 24 months of availability to Camille’s 80.

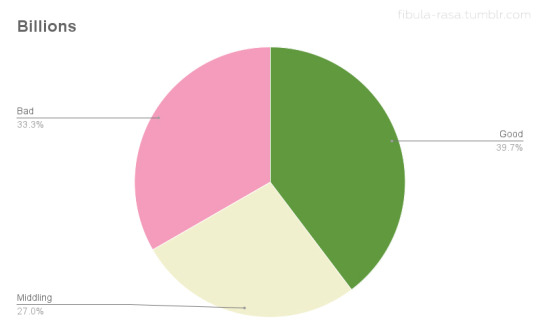

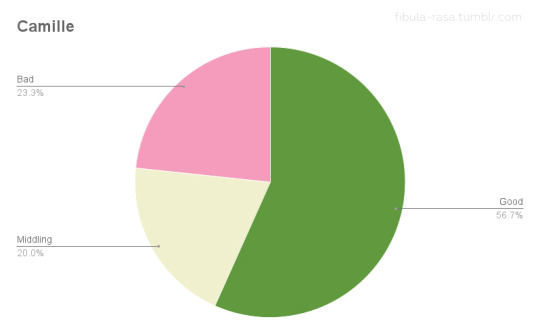

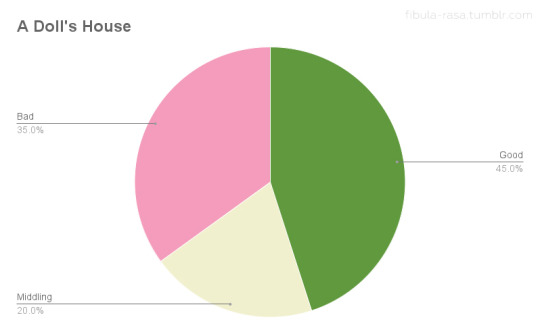

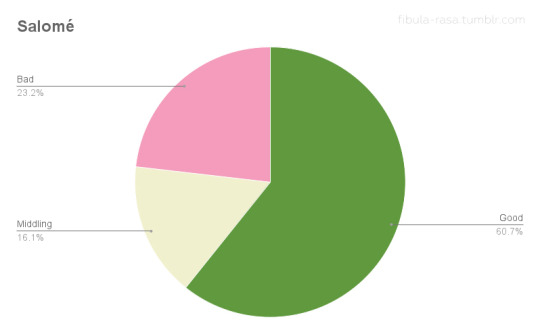

To get a little deeper into this data, I wanted to see how the feedback from exhibitors and theatre owners compared. I broke down the exhibitor feedback for each film as positive, middling, or negative based on how the exhibitors assessed audience response and/or box office receipts. (I discounted feedback that only reflected theatre owners’ own personal assessment of the films without mention of their patrons or receipts.) Positive feedback could be good reception and/or good receipts, middling suggests only average business and no noteworthy reception, and negative indicates poor response and/or poor ticket sales. Since there are so many more items about Camille and Billions than A Doll’s House and Salomé, I compared ratios as an indicator of exhibitor satisfaction. The results were truly surprising.

Theatre owners who rented Salomé may have been in significantly smaller numbers than those who ran Camille, but their satisfaction with ticket sales and audience feedback was roughly equivalent. (Though slightly more positive for Salomé!) The numbers for Billions line up with the qualitative assessment I summarized above, displaying a roughly equal 3-way split. A Doll’s House was the most divisive with the highest proportion of negative feedback of the four films, yet with a higher proportion of positive feedback than Billions.

Taking all of this into account, it’s clear that Salomé did not flop because it was too artsy or esoteric for the American moviegoing public. Such assumptions are obviously not very thoughtful or informed by reliable data.[7] A more historically sound reading is that, as professional filmmaking matured into a “legitimate” industry in the US, the various arms of the business were rigidly formed to fit conventional output. The conservatism that this engendered made the American industry ill-equipped at marketing anything too unconventional or experimental. While Hollywood insiders were lamenting European filmmakers artistically outdoing Americans—especially following the US release of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)—very few people with the power to shape the industry did anything to support experimentation. Given this environment, Salomé could only have been produced independently, but the quickly ossifying distribution and promotional systems didn’t have the range to give it a proper release. Two films contemporary to Salomé, Beggar on Horseback (1925) and The Old Swimmin’ Hole (1921) offer further evidence of the industry’s limitations.

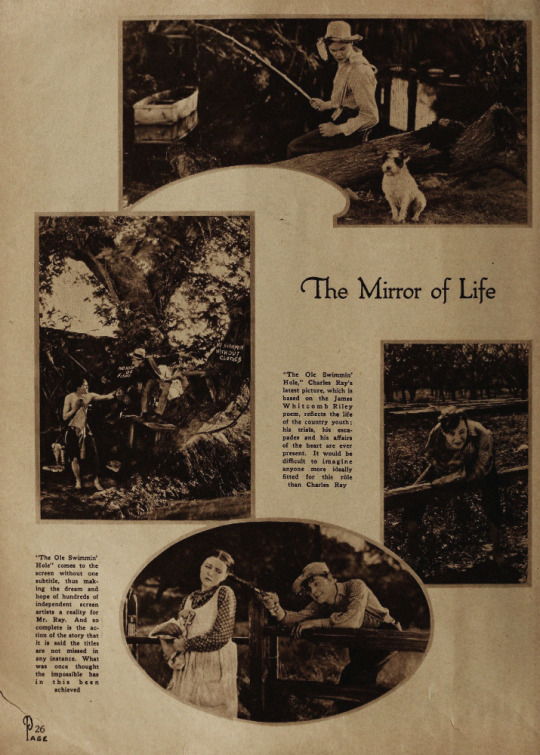

The Old Swimmin’ Hole is a feature-length production by Charles Ray, experimental in that it uses no intertitles. The story is simple and familiar with Ray playing the Huck-Finn-type character he was well known for. Ray’s experiment was not an expensive one and the film was successful. However, decision makers at First National, the film’s distributors, felt that The Old Swimmin’ Hole was simply too complex for small-town Americans to comprehend and it wasn’t released outside of cities. To put it plainly, the distributor’s unfounded concept of ignorant yokels meant that a film about country living was largely inaccessible to anyone actually living in the country. Though the film was well received and turned a profit, this distribution decision likely limited its audience as well as possible revenue from small-town exhibition.

Stills from The Old Swimmin’ Hole from Motion Picture Magazine, April 1921

Beggar on Horseback was produced by one of the biggest studios in Hollywood, Famous Players-Lasky, and distributed by Paramount. Starring comedian Edward Everett Horton, Beggar was an expressionist comedy based on a popular play. The film had a popular star, popular source material, and was made and released by a major company, but Beggar was apparently too unconventional for that major company to adequately market it. (Unfortunately, only a few minutes of the film survive, so we can’t fully reassess it unless more is found/identified!)

Stills from Beggar on Horseback from Picture-Play Magazine, August 1925

With all these complicating factors at play, how might have Salomé found its audience in 1922-3? Nazimova and Charles Bryant had innovative ideas for the film’s release that might have done the trick, if they had been able to act on them. Nazimova and Sam Zimbalist had finished cutting Salomé in late-spring 1922. Having spent practically all of her money to finish the film, and following A Doll’s House’s disappointing results, Nazimova was eager for Salomé to hit theatres. Though the film was in the can and private preview screenings had been held by Bryant by summer ‘22, Salomé wouldn’t be released until February of 1923. In studio filmmaking, holding a film in extended abeyance wasn’t ideal but it was not disastrous. Studios had significantly more resources and revenue streams than independent producers. If, for example, the release of Billions had been delayed for seven months, Nazimova still had two films on the Metro exchanges (and therefore in theatres) and Camille would have entered production in the meantime. But for Nazimova as an independent producer, this situation was wholly untenable. (In fact, Pickford, Fairbanks, and Griffith were in a similar untenable situation when they founded Allied.)

Initially, Bryant proposed roadshowing Salomé. Roadshowing is a release strategy for notable film productions where a film is toured around major cities, often with in-person engagements by stars, writers, and/or directors. Nazimova expanded the idea of touring with Salomé not simply as a roadshow, but paired with a short play in which she would star. Double the Alla, double the fun. As far as I can tell, there isn’t publicly available information about why Salomé wasn’t roadshowed. However, we do know that Griffith, as the only non-performer in UA, wanted to utilize different approaches for the release of his films—like roadshowing—and it became one of the major points of disagreement with his fellow UA decision makers. That could be taken as an indication that something similar might have occurred with Nazimova and Allied.

As time dragged on without a release date for Salomé and Nazimova returned to theatrical work—openly admitting to audiences that she was broke—Bryant took matters into his own hands. At the end of December 1922, Bryant negotiated with the owner of the Criterion Theatre in New York City for Salomé to run on New Year’s as a special presentation. In two days, Salomé grossed $2,630, setting records for the theatre. Adjusted for inflation, that’s $48,988.96. It was successful enough that the owner of the Criterion opted to hold the film over. This bold move must have lit a fire under Allied’s tuckuses, as Salomé finally had its first-run release a little over a month later.

In the 1920s, the first-run booking of a film was a crucial part of its further success. Concurrent nationwide release of films wasn’t the norm yet, and if a film was a big production, getting booked at high-capacity motion picture houses in major cities was a necessity. These big city releases would, in theory, generate interest in the film with exhibitors across the country and internationally. Basically, if you spent a lot on a movie but couldn’t land a first-run release, you weren’t likely to turn a profit or even break even. Salomé had a handful of first-run bookings and local reviewers from those cities believed the film would succeed. A reviewer from the Boston Transcript in February 1923 wrote:

“…this newest Salome is something far better than a photographed play. Considered both as picture acting, and as an interesting experiment in design, “Salome” is a notable production. It will have a far and wide reaching influence on future films in this country.”

But, as I mentioned, only a handful of first-run theatres played Salomé, and, taken collectively, the notices I analyzed from contemporary trades imply that it didn’t gain traction once it was made available beyond its initial run.

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

During this regrettably short theatrical run, exhibitors and reviewers from trade publications advised that Salomé was a unique film that called for unique promotion. The overall assumption was that theatre owners knew their patrons and recognised whether out-of-the-ordinary movies were popular with them. Rather than purely judging a film’s quality, exhibitors and trade reviewers had concerns specific to exhibition when providing feedback. These concerns cannot be overlooked if you want to understand their assessments. For example, exhibitor feedback was very often informed by how high the rental fees were for a film, even if exhibitors don’t directly mention said fees. That is to say, a mediocre film might be rated highly if the rental fees were modest (and if block booking wasn’t an issue). Reviewers in the early 1920s, both for popular magazines and trade publications, were already accustomed to the formulaic nature of most studio output. Their reviews commonly expressed fatigue with studio films’ lack of originality. And, perhaps surprisingly, this sentiment was shared among theatre owners as well—particularly when a run-of-the-mill film was sold to them as anything other than a “programmer” (a precursor to B-movies).

What I have learned, not just by analyzing feedback for Salomé, but also for all of the films in my LBnF series, is that when a 1920s reviewer calls out bizarreness in a film, it’s not always a negative quality, even when the review isn’t positive. In the case of reviews written for exhibitors/theatre owners, focussing on what makes a movie different is purely pragmatic. It guides how exhibitors might market films to patrons and helps exhibitors judge if a film would be suitable for their audiences. And, from that same research, I’ve found significant indications there were numerous markets throughout the US that were hungry for novelty—contrary to what studio apparatchiks wanted to admit. So, pointing out Salomé’s bizarreness was a recommendation for those markets to consider renting it as much as it was a warning against renting for theatre owners who only had success with more conventional films.

Cover of the Campaign Book for Salomé reproduced in Exhibitors Herald, 9 February 1924

In the case of Salomé, reviews and feedback upon its release focused on two major points:

The film isn’t “adult” in nature. Well-known productions of Strauss’ opera and the 1918 Theda Bara film of the same name led to a presumption of salaciousness. (I talked a bit about that in Part One!)

The film deserves/requires a build up as an artistic event film.

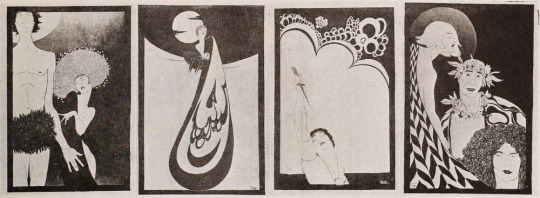

Nazimova’s company helped exhibitors with the latter point in a few ways. The company provided Aubrey Beardsley inspired art posters conceived by Natacha Rambova and executed by Eugene Gise. They printed a book to guide promotion of an artistic spectacle. (So far, I haven’t been able to find a physical or digital copy, so I can’t assess how good the advice was!) Salomé was also distributed with an official musical score, apparently written for a full orchestra.

Art Posters designed by Rambova and painted by Gise as reproduced in Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 10 February 1923

The exhibitors who ran Salomé—and put at least some of this advice into practice—were satisfied with the business it did. By these accounts, the American moviegoing public was attracted by the novelty of Salomé, but what chance were they given to see it?

While this evidence of Allied’s poor distribution work may be circumstantial, it certainly complicates the narratives that Salomé was an unqualified flop or that average Americans weren’t (or aren’t) receptive to artistic experimentation. Given that Nazimova was not the only independent filmmaker who suffered from Allied’s inept distribution, it does seem like the underwhelming business Salomé did was due more to a poor choice of business partners than to any quality of the film or of American moviegoers. That said, with the increasing monopolization of the industry, Nazimova did not have a wealth of options.

Though Salomé was made and released at an tumultuous period for the US film industry, it did eventually find its audience through circulation in art cinemas. As the gap between experimental/avant-garde film widened in the US and the professional industry became less and less tolerant of departures from convention, Americans concerned with film as an art form rallied around amateur filmmaking clubs and art cinemas began popping up in cities by the middle of the decade. Salomé played in these theatres even after the advent of sound—occasionally even today. This is likely the key reason that Salomé survives and we’ve been able to continue to enjoy and reevaluate it one hundred years later.

Salomé is a significant film made at a significant moment in American film history. Nazimova took a major risk in going independent and personally funding two artistic projects. These films were founded on the beliefs that American moviegoers wanted art made by human beings with unique imaginations, feelings, sensibilities and that there was an audience for more than derivative, “machine-made” film. In my opinion, through close analysis of the circumstances of Salomé‘s release, we can see that Nazimova was likely correct, but didn’t get a genuine chance to prove it in her lifetime. Additionally, it’s important to note that Nazimova’s risks did not “ruin” her as is occasionally said. The state of her finances were more greatly affected in the 1920s by her fake husband’s habit of spending her money and by getting swindled by a pair of con artists over her estate, The Garden of Alla. Soldiering on, Nazimova continued to work in both theatre and film for the rest of her life and found more stability with the partner she would meet at the end of the 1920s, Glesca Marshall.

——— ——— ———

Once I finished this “Cosplay the Classics” entry, I realized that it would way too much for me to include a section on another relevant topic to Salomé: Orientalism in Hollywood. But, I feel that the topic is too important to just edit that writing out. Look out for a shorter “postscript” entry soon!

——— ——— ———

☕Appreciate my work? Buy me a coffee! ☕

——— ——— ———

Footnotes:

[1] Danse Macabre is also thought to be a major influence on Walt Disney animating to music, as seen in “Silly Symphonies” and later Fantasia (1940) and Disney’s other musical anthology features. It was also in this period that Disney fled from his debtors in the Midwest to California with his first “Alice” movie. However, the wide-ranging effects of Disney’s business practices were not felt until much later, so that’s another story for another time!

[2] Nazimova was one of a handful of women in Hollywood at the time who held significant creative power. June Mathis and Natacha Rambova, both of whom Nazimova regularly worked with, Mary Pickford and her regular tag-team partner Frances Marion are among some of the others.

[3] Chaplin wouldn’t produce a film for UA until 1923’s A Woman of Paris, as he was fulfilling a pre-existing contract with another studio.

[4] According to Gavin Lambert’s biography of Nazimova (which I discussed as a largely unreliable source in Part One), Robert Florey supposedly advised Nazimova against signing with them, citing Max Linder and Charles Ray as artists who had been “ruined” by their deals. However, the timeline does not quite match up. Though Florey did visit the set of Salomé, Nazimova had already signed the Allied deal by then and Ray had not finished The Courtship of Miles Standish (1923) when Salomé was in production. In fact, there was almost a year and a half between the completion of Salomé and the release of Standish. Whether this was a lapse of memory by Florey or misreporting by Lambert, I can’t be sure.

[5] Originally, I wanted to include Madonna of the Streets (1924) in my comparisons but, at the moment, Lantern has gaps in their Moving Picture World archive for 1924-5. I didn’t want to draw conclusions from incomplete data.

[6] Billions was also a Rambova-Nazimova collaboration. Rambova designed a fantasy sequence for the film.

[7] A mindset that’s still common among commercial media outlets today unfortunately. I could rant and rant about “content” and “content creation” all day but that’s another story for another time.

——— ——— ———

Bibliography/Further Reading

(This isn’t an exhaustive list, but covers what’s most relevant to the essay above!)

Lost, but Not Forgotten: A Doll’s House (1922)

“Nazimova in Repertoire” in Motion Picture News, 29 October 1921

“Alla Nazimova Plans for Her New Pictures” in Moving Picture World, 29 October 1921

“Nazimova Abandons Dual Program for Latest Film” in Exhibitors Herald, 24 December 1921

“Plays and Players”in Photoplay, February 1922

“PICTORIAL SECTION” in Exhibitors Herald, 4 February 1922

“New Nazimova Film May Be Roadshowed“ in Exhibitors Herald, 15 April 1922

“Newspaper Opinions” in The Film Daily, 3 January 1923

“Splendid Production Values But No Kick in Nazimova’s ‘Salome’” in The Film Daily, 7 January 1923

“Claims “Salome” Hit New Mark at N. Y. Criterion” in Exhibitors Herald, 27 January 1923

“Salome” in Exhibitors Trade Review, 20 January 1923

“Nazimova in SALOME” in Exhibitors Herald, 27 January 1923

“Nazimova Appeals To Exhibitors In Behalf of ‘Salome’” in Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 27 January 1923

“Novelty Features Paper and Ads for ‘Salome’” in Exhibitor’s Trade Review, 10 February 1923

“SALOME’ —Class AA” from Screen Opinions, 15 February 1923

Nazimova: A Biography by Gavin Lambert (Note: I do not recommend this without caveat even though it’s the only monograph biography of Nazimova. Lambert did a commendable amount of research but his presentation of that research is ruined by misrepresentations, factual errors, and a general tendency to make unfounded assumptions about Nazimova’s motivations and personal feelings.)

Lovers of Cinema: The First American Avant-Garde 1919-1945 ed. Jan-Christopher Horak (most notably, “The First American Avant-Garde 1919-1945” by Horak, “The Limits of Experimentation in Hollywood” by Kristin Thompson, and “Startling Angles: Amateur Film and the Early Avant-Garde” by Patricia R. Zimmermann)

United Artists: The Company Built by the Stars, Vol. 1 1919-1950 by Tino Balio

#1920s#1922#Salomé#salome#nazimova#alla nazimova#film history#cosplay#queer film#silent era#classic movies#film#avant garde#experimental film#cinema#queer film history#silent cinema#1923#classic cinema#american film#women filmmakers#women in film#silent film#classic film#silent movies#bisexual visibility#cosplayers#natacha rambova#united artists#Metro

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

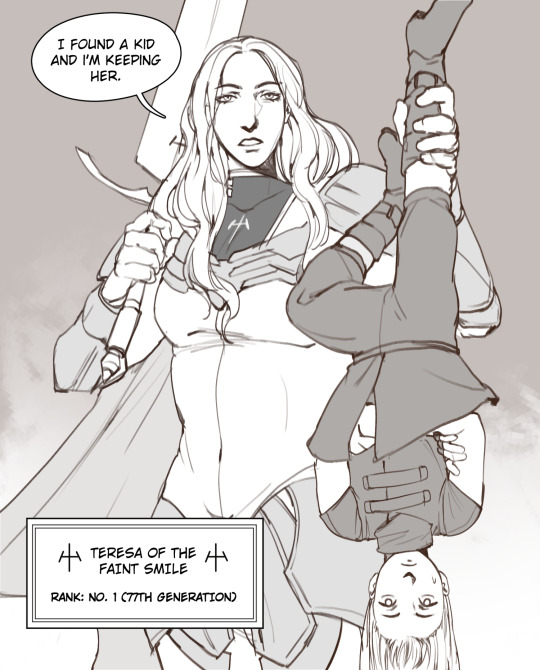

how clare managed to lock down the two strongest warriors of her generation as mums.

a claymore fancomic.

#the manga claymore literally completed in 2014#its nearly been a decade since it ended#and of all times the brainrot strikes now#i havent read this series all the way through since i think 2016#the sword lesbian brainrot lies ever dormant#anyway this is an au where everything is fine and i decide the rules#everyone's happy#clare claymore#teresa claymore#irene claymore#claymore manga#teresa of the faint smile#manga#stillindigo art#comic art#teresa x irene#fancomics

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

🏳️⚧️ DOUBLE HEADCANON ATTACK!!! 🏳️⚧️

Family HCs are already fun on their own but with transness added on they're even better. It's actual comedy gold. Also I've always wanted to draw some kind of Meta Knight VS Galacta Knight type thing, but I can't take anything seriously like that. So you get This.

What This is, is a way too high effort shitpost. It took a combined 2 and a half? Days, though most of it was just sketching. I'm proud of it! Anything for the bit.

Textless version + unfinished doodle under the cut

#kirby#kirby series#galacta knight#does he know? (he does not know)#meta knight#trans meta knight#trans mask even. is anyone there. whatever.#anyway. the extra doodle was originally gonna be part of the main drawing#specifically the bottom one. i think you can really tell by how much effort i put into it#But in the end it wasn't looking like i pictured it#i was also struggling trying to draw GK's lance in a way that didn't completely annoy me#so i gave up#i also gave up coloring it. sorry#i love colored lineart!#also i swear on my life i intended to shade this#i tried. thought about how it was almost 12 am. and decided against it#i do like how it looks unshaded though#i'm not very good at shading/lighting yet so it would've probably looked muddy#thank god for filters#i hope you guys like mk's wings those were also a source of eternal torment#i'm so happy with how they look though#also. obligatory baby orb. squish him and bake him into bread okay?#my art

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

The world he dreamt

will never be.

So, let’s enjoy reality.

#happy ending thailand#happy ending the serie#jeff satur#barcode tinnasit#mike angelo#jorin khumpiraphan#happyendingedit#thai drama#my edits.#this teaser took me by complete surprise#i love jeff's brand of psychological horror

319 notes

·

View notes

Text

✦ F F X I V L E V E L 9 0

—compendium