#c: xerxes

Text

Took me a bit but I still ran out of energy with this piece, but Finch and Xerxes have art! I just thought that they were neat so :) I’m too out of it right now to add much about them right now but I’ll do that in the morning. For now, enjoy.

#i was gonna make them both red haired but descided against it#flight rising#fr#flight rising dragon share#fr dragon share#fr art#flight rising art#dragon share#fr gijinka#flight rising gijinka#c: finch#c: xerxes#art

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

a gift for @ofromulan,

note: time is a construct, but we're spiraling

Haven's demise marked the beginning fragments of Tamlen's self-destruct button. All had been forced underground to continue their plans to reset the world to it's former... sanity; but Tamlen was forced to sit inside the depths of the underground world for that one demigod's radar would easily snuff him out if he were to come up for air. Confidence and ego was diffused into a relic further embittered; where once he was angry at mortals for their cruelty against his kind, he drowned in his resentment until he was starkly indifferent to what was asked of him. A warrior forced to be a magical reservoir, the Worldly glared at those who came and went whether it was simple expeditions for supplies or intricate missives to search for and salvage possible survivors. His armor, powered by Yggdrasil's bark collected dust as he sat around, begging for mere scraps of journeys from those who returned back to the catacombs.

Tamlen had once ignored the vampires, lingered with Titania and her generals, even Felandaris; his wall's were subtly whittled down and cracked until the foundation proved to be unstable and the celestial elf could only find himself clinging to anything that gave him something of interest to nod at. Xerxes had went on a frenzy before the gates of the Inferno had opened, slaughtering fey and drow alike, Tamlen had avoided him before they were forced into the catacombs. He smelled of something rotten if one focused too heavily upon it, but Tamlen's senses faded along with his reason and as a few others headed out for supplies, it seemed Xerxes was the one to watch over the celestial elf and his vestige of potent ichor.

The very antithesis of one another, Tamlen pristine and held together, Xerxes vampirically feral, the celestial elf pulled his legs up to his chest and sat in a scowling sense of a tantrum. His magic was drained for the missive's purpose, practically daily, and though he did not feel weaker as a result, his head often felt a touch murky, "Taking the day off?" It was charged with a bitter timbre, but it was only evidence of how Tamlen skulked at what he was reduced to.

0 notes

Text

Double Bull Column Capital from the Apadana of the Palace of Darius & Xerxes. c. 520-465 BCE, Achaemenid period. Persepolis (now housed at National Museum of Iran)

524 notes

·

View notes

Text

British victorian era generator ! :D

Your month of birth:

January: Prince/Princess

February: Baron/Baroness

March: Marquis/Marquise

April: Earl/Countess

May: Butler/Maid

June: Duke/Duchess

July: Homless boy/girl

August: Salesman/woman

September: King/Queen

October: Joker

November: Prostitute

December: Farmer/worker

First letter of your first name:

A: Arthur/Alice

B: Benedict/Beatrice

C: Charles/Cordelia

D: David/Dorothea

E: Elijah/Evelyn

F: Francis/Fiona

G: George/Gwen

H: Humphrey/Helena

I: Isaiah/Iris

J: John/Juliette

K: Kyrie/Kelvin

L: Luther/Lucille

M: Marcus/Muriel

N: Neville/Novalynn

O: Oscar/Ophelia

P: Pascal/Penelope

Q: Qasim/Quintessa

R: Randall/Rosemary

S: Samuel/Sophia

T: Theodore/Theodosia

U: Uriah/Urith

V: Vincent/Victoria

W: William/Willow

X: Xerxes/Xenia

Y: Yoel/Yolanda

Z: Zander/Zipporah

Last letter of your last name:

A: Addams

B: Berrycloth

C: Chapman

D: Dankworth

E: Edwards

F: Featherswallow

G: Graham

H: Hughes

I: Insworthy

J: Jones

K: Knight

L: Lawrence

M: Matthews

N: Naiswell

O: Osborne

P: Palmer

Q: Quintrell

R: Ratcliff

S: Stewart

T: Taylor

U: Underhill

V: Villin

W: White

X: Xavier

Y: Yates

Z: Zachary

Your favorite color:

White: Death by suicide

Yellow: Poisoned by an secret admirer

Orange: Burned alive as a witch

Brown: Stumbled into horseshit face first, while being drunk and suffocated

Red: Killed by Jack the Ripper

Purple: Ran over by a carriage

Blue: Fell of a great height

Green: Ripped apart by a grizzly bear

Grey: Died peacefully in their sleep

Black: Killed by the pest

Comment bellow what you got and tag at least three people >:D

@ctitan98

@lacelynpage

@we-r-loonies

274 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artemisia I - King Xerxes female Admiral

Artemisia I of Caria was a daughter of Lygdamis of Halicarnassus and on her mother's side she was of Cretan descent. After the death of her husband, whose name is unknown, she took over the government of Halicarnassus, Kos, Nisyros and Kalydna before 480 BC - as guardian of her young son Pisindelis. In doing so, she was subject to the suzerainty of the Persian king.

The Battle of Salamis with Artemisia all in white in the middle, by Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1805-1874) (x)

Without external coercion, the extremely daring Artemisia took part in Xerxes I's campaign against Greece in 480 BC and, during the expedition, was in charge of the five ships she contributed, which, according to the historian Herodotus (7,99), "were the most excellent in the whole fleet after Sidon". Herodotus rightly praises her determination and wisdom as well as her influence with the Great King, but some of her actions are anecdotally embellished or even completely invented, which is why her existence is also discussed in research.

First, Artemisia fought in the naval battle at Cape Artemision (August or September, 480 BC) on the Greek island of Euboea. According to Herodotus' account, she was the only one who advised Xerxes not to attack the Greeks in the strait between Attica and Salamis, where the Greek fleet had retreated. All the other war councillors and allies of Xerxes, on the other hand, had advocated the implementation of the naval battle of Salamis. To justify her position, Artemisia stated that the Greek fleet was superior to the Persian one; moreover, the entire Persian land army would also suffer if the fleet were destroyed by the enemies. Instead, Xerxes should move quickly with his land army to the Peloponnese; the Greeks, who lacked provisions at Salamis anyway, would then disperse, abandon Athens and return to their home towns. Apparently, Herodotus is not reproducing an authentic speech by Artemisias here, but his own assessment of the military situation. According to Herodotus (8,68-69), Xerxes was impressed by Artemisia's speech, but nevertheless decided to risk the naval battle against her advice.

Artemisia I, Dynastin of Halicarnassus in the 5th century BC at the Battle of Salamis, by Ferdi[and] Dietz 1881 (x)

Artemisia then took part in the battle of Salamis, September, 480 BC, and is said to have performed great deeds. According to Plutarch, she was able to recover the body of Xerxes' brother and Admiral Ariamenes or Ariabignes, how Herodotus (7,97) called him and bring it back to the Great King. The Athenian fleet commanders had been ordered to capture Artemisia without fail; the one who succeeded was to receive a reward of 10,000 drachmas. The Athenians were outraged that a woman dared to fight against them.

Later in the battle, which was extremely unfortunate for Xerxes, Artemisia was able to evade pursuit by the Athenian Ameinias by sinking an allied ship commanded by Damasithymos, the king of Kalynda, which blocked her escape route. The latter concluded from Artemisia's action that the crew of her ship must be either Greeks or Persian deserters, so he turned away and attacked other ships. Thus Artemisia managed to escape. Xerxes observed the incident and believed she had sunk an enemy ship. He is said to have then noticed that his men behaved like women and his women like men. Herodotus (8,88)

Similarly, Polyainos describes the ruse used in the naval battle of Salamis: when the Persians were already fleeing from the Greeks' ships, Artemisia ordered her sea soldiers, when they were almost caught up, to take down the Persian flags and hoist the Greek ones. By which Polyenus in his work Strategemata c. 100 AD even portrays her as a cowardly pirate (8,53,4). However, she ordered her helmsman to attack one of her own passing Persian ships. This made the Greeks think it was an allied ship, so they turned away and faced other ships. Artemisia, however, having escaped the danger, quickly sailed home.

After the lost battle, Mardonios, a leading Persian military commander, recommended to the Persian Great King that he attempt a new attack on the Peloponnese. Either he should lead this campaign personally or leave it to him, Mardonios, and retreat himself. Before Xerxes made his decision, however, he again asked Artemisia for advice, who firmly advised the king to return home. Herodotus (8,101) While Xerxes marched overland to the Hellespont and then continued to Sardis, she sailed to Ephesus with several of the king's illegitimate sons on board, according to Herodotus (8,103). Plutarch (De Herodoti malignitate, 38), on the other hand, thinks that Xerxes would have brought women from Susa in case his son needed female companions. As we can already see here, we do not know exactly what became of her. And so her story was presumably simply re-spun, because the further statements about her life do not appear until the 1st century AD.

Thus it becomes very dramatic in the story told by Ptolemy Chennos in the 1st century AD that Artemisia gouged out the eyes of her lover Dardanos from Abydos, who had spurned her, in her sleep and then threw herself from the Lucadian rock into the Aegean Sea because of this unhappy love. Her son Pisindelis followed her in the government.

106 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Alastor [Greek mythology; Christian demonology]

In Greek mythology, the name ‘Alastor’ refers to several individuals, including Zeus. It also the name of a specific group of malicious spirits or demons. In particular, an Alastor is an avenging spirit and is associated with a specific family, punishing the members of that bloodline for crimes and misdeeds. These punishments are dissed out on behalf of the Alastor’s host and were said to be the avengers of the dead.

When the Persians invaded Greece, the slave Sicinnus deceived Xerxes, making him send his troops right into an enemy ambush. Poets later claimed that Sicinnus was told to do so by an Alastor, implying that these spirits manipulate people into making decisions that end in bloodshed.

Note that the word ‘demon’ carries a distinctly negative connotation in English, but this wasn’t necessarily the case in ancient Greece: the word daimon (plural daimones), according to Hesiodos in the 8th century B.C., referred to the undead spirits of the people who lived in the mythical ‘golden age’. After dying, these people would return to the world of the living as invisible spirits. They were benevolent, distributing wealth to the living, as long as they were respected. But malicious demons also existed and in some cases, demons were associated with a particular individual and punished them for bad deeds. Or in the case of Alastor demons, with an entire family.

The name ‘Alastor’ was later carried over to Christian demonology as a specific demon: in this iteration, the devil Alastor delivers the sins of fathers onto their children. He also tempts mortals into committing murders. According to Jacques de Plancy’s 1818 Dictionnaire Infernal (see image), Alastor is the executor of decrees in Lucifer’s court of justice. Even among the demons of hell, he is said to be exceptionally cruel and severe.

Sources:

Hastings, J. E., 1911, Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, Volume IV, p.591, which you can read here.

Saniotis, A., 2004, Tales of Mastery: Spirit Familiar in Sufi’s Religious Imagination, Ethos, 32(3): pp 397-411.

De Plancy, J. C., 1818, Dictionnaire Infernal ou Recherches et Anecdotes sur les Démons, les Esprits, les Fantômes, etc., Paris, France.

Bane, T., 2014, Encyclopedia of Demons in World Religions and Cultures, McFarland, 416 pp.

Jones, L., 2005, Encyclopedia of Religion, Volume 4, Macmillan Reference USA, USA, 112 pp.

(image source: Louis le Breton, illustration for 1863 edition of ‘Dictionnaire Infernal’)

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

PREVIOUSLY WASABICHIPS

lex/alex. 28. black. they/them. i play silly little games and yell about my ocs.

i do not follow or talk to minors, and this blog is 18+. while most of my posts are pretty tame, considering tumblr's rules and guidelines, i do sometimes post explicit thoughts/text posts about my ocs and favorite characters, and i am not comfortable with minors seeing/interacting with those posts. so yeah, minors please clear out. i will block you.

mutuals feel free to ask for my discord or other socials !!

— BALDUR'S GATE 3 —

| general | valen ( my pride and joy !! ) | iaira | ten | | indra | caelum | spoilers | mod list ( not comprehensive; just my favorites )

— TS4 —

| general | wcif ( i am wcif friendly btw !! ) | interiors | cas pics | resources ( needs updating ) | cc finds blog |

— OCS —

| valen ( my baby my mf cinnamon apple; i will take any and every opportunity to talk about them ), | beau | kanver (yes, he's named after a city in ffxvi ) | zahir | oliver | lulakhan | rina | mickey | khorvis | isao | jasper | xerxes | yves ( still really new; valen took over shortly after they were made :c ) | kaias | zeus | caem | teddy | haiba | kit | tatsu | hachi |

— OTHER STUFF —

| final fantasy xvi | final fantasy xv ( my comfort game of all time ❤️ ) | final fantasy xiv | final fantasy vii | nbc hannibal |

#lext post#finally finished linking everything#even linking ocs i don't post anymore bc i still love them and my roommate and i still rp with them so

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

In some of your posts, you've said we can't believe the speeches in the original sources like Plutarch and Arrian. And I get it, that they wouldn't have ways to record exactly what people said, but wouldn't they try to get it at least close? Didn't orators publish their speeches, so they'd know what they said? Demosthenes published speeches about Philip, I know. And wouldn't readers back then get angry if they realized the writers were just making things up?

When it comes to ancient texts, particularly ancient historical texts, speeches, dialogue, and letters are especially problematic. Why? Authenticity.

As the asker indicated, a lack of recordings automatically problematizes this. But their memories were generally better. The real issue centers on ancient ideas of WHAT HISTORY WAS FOR.

Ancient historians were writing to entertain, as well as to educate, and promote their notions of how the past should be understood, often to school people in their present. “Cautionary tales,” if you will. Or models to emulate. When they do say where they got their information (frustratingly rarely), it’s as much to show off their education/how well-read they are, rather than to assure their readers they know what they’re talking about.

It’s critical to understand that ancient history was akin to modern creative nonfiction. I don’t say that to diss creative nonfiction (says the historian who also writes historical fiction). But it’s crucial to recognize it was nothing like modern academic history with footnotes, peer reviews, and fact-checks.*

In terms of preserved speeches (or orations), we have two types. The first (often forensic) were published after the fact by the orator himself.** Those are indeed their words, but their edited words. Unlike now, ancient speeches were typically composed aloud, not in writing. But at least speeches published by the orator are authentically their ideas, if not, perhaps, what was actually said (in court, the assembly, etc.). Nobody is putting words in their mouth.

By contrast, the orations and dialogue in our histories are the creations of the authors of those histories. Why goes back to the first (Greek) historians: Herodotos and Thucydides (and Xenophon). They set a pattern that later generations deliberately followed. All put speeches into the mouths of their major players. This is called oratio recta (direct speech), or what we’d call a quotation. Another form is oratio obliqua (indirect speech), or what we’d call a summary or a paraphrase. In general, the use of the former characterizes the Greek historians, while Roman historians preferred the latter. (There are any number of exceptions, however.)

Incidentally, these writers didn’t lie about it. Their readers/listeners realized it highly unlikely Herodotos knew what Darius or Xerxes said back in Susa or in the Persian camp, but they were there for the drama. Thucydides even admits (1.22.1) he has no clue what was said in the speeches he records from the Peloponnesian War, but he wrote what he thinks would have been proper for the situation.

Why make it up?

Orations were entertainment.

Just as modern fiction authors craft a story to forward themes and motifs, so also with ancient authors. When an author writes out a speech, PAY ATTENTION. It usually contains key points.

In our modern world with lowered attention spans, we can forget that people might listen to orations (especially longer ones) for fun.

Yet this is extraordinarily recent. For as long as we’ve been human, we’ve gathered to hear good storytellers and be inspired by good speakers. Sometimes the art of rhetoric is equated with intentional lying. That’s cynically silly. The art of rhetoric just means getting across your point clearly, and powerfully. A goodly chunk of Barack Obama’s appeal was his fine rhetoric. Ironically (and like it or not), the same can be said of Trump; the Maga crowd adores his word-salad “oration” style. Similarly, in some religious traditions, “good preachin’” is considered essential to good pastoring. And monologues, whether comedic, newsy, or folksy can develop cult followings, as The Rachel Maddow Show proves, or Stephen Colbert, or the much earlier “News from Lake Wobegon” from Prairie Home Companion (Garrison Keillor). You can probably name another half-dozen without breaking a sweat.

Because the oration was a form of entertainment in antiquity, many ancient authors sought to prove their own creative brilliance by writing speeches. That’s why you should never, ever, ever assume a verbatim speech in ANY Classical Greek or Roman text is what the speaker actually said. If you’re lucky, it may at least represent the gist. But it also might not. Dialogue is similar. They make it up.

With letters, one might think at least they could copy it—no need to remember. Like orations, letters were sometimes published by one of the authors, for posterity. (The letters of Cicero, or the Younger Pliny are good examples.) Yet the same principle applies. Letters were a way for an historian to display creative chops so “tweaked” letters were not uncommon, even if based on an original. And sometimes letters were invented whole-cloth, at need.

Yet there’s another issue with letters that moderns aren’t aware of: accidental forgeries.

How can a forgery be accidental?

It’s a rhetorical-school lesson that “escaped.”

A popular assignment for students was to write a letter (or oration) “in the style of ___ famous person,” or “as if from the point-of-view of ___ famous person.” Lessons weren’t just to learn how to turn a phrase, but also to instill proper morals. So, for instance, some ancient schoolboy’s essay prompt might be: “Illustrate pistos/fides (loyalty) in a letter from Alexander to his mother, Olympias.” To get a good grade, he had to show he knew something about Alexander, about proper pistos/fides, as well as how to write like a king.⸸

Some of these letters got confused later with the real thing. Remember, record-keeping was rather haphazard.

So…recorded speeches, dialogue, and letters in our ancient histories should be regarded much the same as you’d regard such in modern creative non-fiction: dramatization to increase reader interest.

——————————————-

* This isn’t to say ancient historians never critiqued each other; they most certainly did. Sometimes quite brutally—and from the beginning. Thucydides is our the second surviving Greek historian and he begins his history by, in his very first chapter, including an oblique criticism of Herodotos, who invented the discipline!

** Male gender used on purpose. Greek women weren’t allowed to make public speeches, and Hortensia was considered a weirdo who pissed off the Second Triumvirate. She certainly gave a speech, but Appian put words in her mouth—like most ancient writers.

⸸ Ironically, I do something very similar in my own classes on Alexander. We put him on trial for war crimes, and students write either as Alexander in his own defense, or as the prosecutor, whoever that might be (Demosthenes, the King of Tyre, a Persian noble, etc.). They must write their speech demonstrating the morals of the ancient world, not the modern, using the primary sources. To get a feel for it, they must read a couple Greek forensic speeches too, in order to understand how to properly frame their arguments. This allows them “to get into the heads” of the ancients themselves. It’s not only more fun, but more effective as a learning tool, imo.

#asks#ancient literature#speeches in ancient literature#letters in ancient literature#historiography#Classics#Greek historians#Roman historians#ancient history#tagamemnon

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just in time for Payday! Iron Wind Metals restocks are up for BattleTech!

20-206 Huitzilopochtli Assault Tank "Huey" (Standard)

20-267 Sentry SNT-04

20-318 Pilum Wheeled Tank

20-398 Shrike SHK-VP-A

20-458 Cattlemaster RA-4 Hunter / Herder

20-5134 Juliano JLN-5A

20-5167 Raven II RVN-5X

20-5174 Ursus II (Standard)

20-5185 Commando COM-2D

20-5194 Sojourner Prime

20-5200 Carrion Crow Prime

20-610 Black Hawk "Nova" Prime (Old Sculpt)

20-634 Epona Pursuit Tank Prime (2)

20-642 Berserker BRZ-A3

20-648 Venom SDR-9K

20-674 Falconer FLC-8R

20-722 Anhur Transport

20-757 Strider SR1-O Prime

20-800 Hex Bases (4)

20-904 O-Bakemono OBK-M10

20-958 Vanquisher VQR-2A

20-9122 Battleforce Hex Base

99-201 Large Flat Top Hex Base #1

BT-001 Orc Protomech

BT-006 Phalanx Battle Armor

BT-023 Overlord

BT-026 Union (2708)

BT-027 Union C

BT-028 Cavalier Battle Armor

BT-029 Sloth Battle Armor

BT-035 Overlord C

BT-057 Gazelle

BT-058 Fury

BT-067 Golem Battle Armor

BT-087 Scout / Quetzalcoatl Jumpship

BT-169 Behemoth Micro Dropship

BT-170 Buccaneer

BT-178 Jade Hawk JHK-03

BT-183 Aurora Micro Dropship

BT-188 Nighthawk Battle Armor

BT-189 Kobold Battle Armor

BT-202 Rogue Bear Heavy Battle Armor

BT-226 Fast Recon

BT-232 Warg Battle Armor

BT-260 Sprint Scout VTOL

BT-284 Svartalfa Ultra ProtoMech 2

BT-285 Sprite Ultra Protomech

BT-287 Zephyros Infantry Support Vehicle

BT-312 Gun Trailers (2)

BT-316 Chimera CMA-2K

BT-353 Mad Cat MK II 4

BT-373 Centaur Protomech

BT-376 Minotaur Protomech

BT-393 Kage Battle Armor Squad (4)

BT-404 Wusun Prime Micro Fighter

BT-405 Ostrogoth Prime Micro Fighter

BT-430 Wulfen H

BT-436 Buraq (Standard) Battle Armor

FT-019 Kirghiz Mech Scale Fighter

FT-022 Xerxes Mech Scale Fighter

FT-024 Shiva Mech Scale Fighter

FT-035 Tatsu Mech Scale Fighter

FT-036 Defiance Mech Scale Fighter

OP-013 Thor E ATM Pod

OP-021 Loki A LRM 20 (from 20-603R)

#battletech#alphastrike#ironwindmetals#battletechalphastrike#miniatures#catalystgamelabs#battlemech#battletechminiatures#battletechpaintingandcustoms#classicbattletech#miniaturewargaming#mechwarrior#mecha#gaming#boardgames#tabletop#tabletopgames#tabletopgaming#wargaming#wargames#hobby#scifi#sciencefiction#miniaturepainting#mech#6mmminis#6mmscifi#dougram#gundam#robotech

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

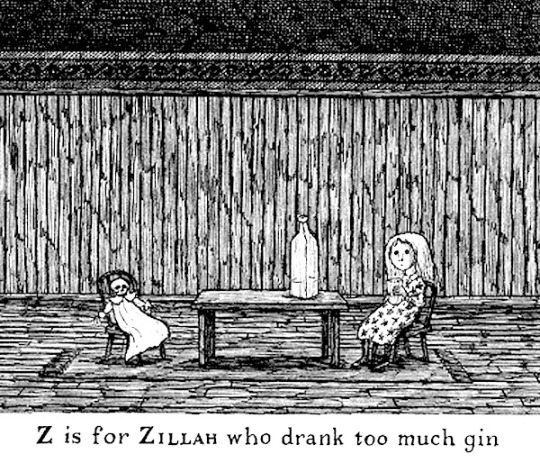

EDWARD GOREY

The Gashlycrumb Tinies

A is for Amy who fell down the stairs.

B is for Basil assaulted by bears.

C is for Clara who wasted away.

D is for Desmond thrown out of a sleigh.

E is for Ernest who choked on a peach.

F is for Fanny sucked dry by a leech.

G is for George smothered under a rug.

H is for Hector done in by a thug.

I is for Ida who drowned in a lake.

J is for James who took lye by mistake.

K is for Kate who was struck with an axe.

L is for Leo who swallowed some tacks.

M is for Maud who was swept out to sea.

N is for Neville who died of ennui.

O is for Olive run through with an awl.

P is for Prue trampled flat in a brawl.

Q is for Quentin who sank in a mire.

R is for Rhoda consumed by a fire.

S is for Susan who perished of fits.

T is for Titus who flew into bits.

U is for Una who slipped down a drain.

V is for Victor squashed under a train.

W is for Winnie embedded in ice.

X is for Xerxes devoured by mice.

Y is for Yorick whose head was knocked in.

Z is for Zillah who drank too much gin.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Moschophoros (c. 560 BC), at the moment of his discovery on the Acropolis, Athens

Part of the archaeological remains called Perserschutt, or "Persian rubble": remnants of the destruction of Athens by the armies of Xerxes I. Photographed in 1866, just after excavation.

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2554279

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

my sona is supposed to be a fusion of me and xerxes and a bit of naven. don't question it :}

my artstyle's inspired by lindsay c. cibos (especially her book "peach fuzz")

#epithet erased lovepotion#phoenica fleecity x trixie roughhouse#phoenica fleecity#trixie roughhouse

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

You may have seen me talk about Xerxes fic on here--and there it is! Enjoy!

Fullmetal Alchemist, Mature, Ch 1/?, 5.5K

Tags/Warnings: Rape/Non-Con, Post-Canon, Angst and H/C, Hurt Edward Elric, Non-Consensual Drug Use, Rape Recovery

Summary:

Edward had meant to only briefly stop in Xerxes for some research on his way to visit Alphonse in Xing.

He hadn't expected to encounter people living in the ruins of Xerxes—not Ishvalan refugees, but settlers from Amestris.

And what kind of researcher would he be if he didn't find out what had brought them here?

If he had known what he would find, he would never have gotten involved. He wouldn't have let them see him.

#fma#fullmetal alchemist#fmab#fma fanfic#fullmetal alchemist brotherhood#nihi writes stuff#xerxes fic

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Tourist's Perspective Visit Iran and Myanmar

Embarking on an expedition to uncover the histories of Iran and Myanmar feels like entering a crafted tapestry adorned with stories of empires diverse cultures and awe-inspiring landscapes. The allure of these two countries lies in their captivating blend of wonders. Magnificent natural beauty. This essay delves into the captivating encounters that await those who seek an understanding of the historical narratives woven within Iran and Myanmar.

I. Enigmatic Persia; Irans Enduring Tapestry

Iran, with its heritage spanning across centuries stands as a testament to the timeless strength of civilization. Every corner, from the wonders of Persepolis to the markets of Isfahan holds stories that echo through the annals of history.

A. Persepolis – A Glimpse into Ancient Splendor;

No journey through Iran is complete without experiencing the awe-inspiring Persepolis once the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire. Marvel at the Apadana Palace adorned with carved reliefs and be awestruck by the imposing Gate of All Nations. As you explore these ruins it's almost as if you can sense echoes, from Darius the Great and Xerxes resonating in every breath.

C. Yazd – A Living Heritage:

The ancient city of Yazd, with its labyrinthine lanes and adobe architecture, provides a glimpse into traditional Persian life. Explore the Jameh Mosque, the Yazd Atash Behram (Zoroastrian fire temple), and the historic wind towers that define the city's skyline. Yazd's designation as a UNESCO World Heritage site underscores its importance in preserving Iran's cultural heritage.

II. Myanmar's Enigmatic Past: Tracing the Footsteps of a Golden Land

Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, is a land steeped in spirituality and adorned with ancient temples. From the plains of Bagan to the serenity of Inle Lake, Myanmar Luxury Travel offers a journey through time, unveiling the mysteries of its past.

A. Bagan – Where Temples Touch the Sky:

The archaeological wonder of Bagan is a testament to Myanmar's glorious past. With over 2,000 temples dotting the landscape, Bagan is a surreal experience for history enthusiasts. Sunrise hot air balloon rides over the plains provide a breathtaking panoramic view, allowing visitors to appreciate the sheer scale of this ancient city.

B. Mandalay – Royal Residences and Spiritual Sanctuaries:

Mandalay, the last royal capital of Myanmar, boasts the Mandalay Palace and the revered Mahamuni Buddha Temple. The U Bein Bridge, stretching gracefully across Taungthaman Lake, is a mesmerizing spot to witness both sunrise and sunset. Mandalay's cultural richness and regal heritage showcase the opulence of Myanmar's past.

C. Inle Lake – Serenity Amidst Nature:

Inle Lake, surrounded by mist-shrouded mountains, is a haven of tranquility. Explore floating gardens, stilted villages, and the unique leg-rowing technique of Inle's fishermen. The Phaung Daw Oo Pagoda, situated on the lake, is a sacred site that adds a spiritual dimension to the natural beauty of the surroundings.

III. Cultural Encounters and Gastronomic Delights:

Both Iran and Myanmar offer not only historical treasures but also vibrant cultures and delectable cuisines that leave a lasting impression on every visitor.

A. Iranian Hospitality and Cuisine:

Iranian hospitality is legendary, and the warmth of the people enhances the travel experience. Indulge in aromatic Persian dishes such as kebabs, saffron-infused rice, and flavorful stews. The bustling bazaars are a sensory delight, offering spices, textiles, and handicrafts that showcase the richness of Iranian culture.

B. Myanmar's Culinary Tapestry:

Myanmar's cuisine reflects its diverse ethnic makeup. Sample Mohinga, a traditional noodle soup, and savor the flavors of Burmese curries. The street markets are a treasure trove of local delicacies, allowing you to embark on a culinary adventure through the diverse regions of Myanmar.

Conclusion:

Embarking on a tour of Iran Travel Packages and Myanmar is a transformative journey that takes you through time and space. The rich history, architectural wonders, and cultural nuances of these nations weave a tapestry that resonates with the echoes of ancient civilizations. Whether exploring the grandeur of Persepolis or witnessing the sunrise over the temples of Bagan, each moment in Iran and Myanmar is a brushstroke on the canvas of a traveler's soul, creating memories that endure long after the journey concludes.

#travel blog#vacation#holiday#travel guide#places to visit#traveling#travel#love on tour#tours and travels#travel photography#europe#asian#christmas

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay thanks to movies and series many foreigners are aware of the Trojan and the Thermopylae war (with the 300 Spartnas). But i believe not many know other important battles that happened during ancient Greece.

Which ones do you think are also worth mentioning?

Just some clarifications for interested people who might not know:

While the Trojan War (sometime in c. 1299 BCE - c. 1100) did happen, we have no idea how accurate any realistic event in the Iliad is. The only thing we know is that the consequences of the war were terrible for both sides. The aftermath is believed to have led to a period of deep regression even in victorious Greece, which is known as the Dark Ages.

The Battle of Thermopylae (not war) (480 BC) is a very real battle, part of the ongoing Persian Wars, meaning the attempts of the Persian Empire to conquer the Greek city-states. While the battle was a defeat stained by treason, the conscious sacrifice of the tiny Greek army caused an uprise of pride and resistance from the Greek people, who up to that point were torn as to whether they should fight or not risk opposing to the massive empire. This is why this battle is considered so important.

So some other turning points in Ancient Greek war history were:

The Battle of Marathon (490 BC). First victory of the Greeks against the Persian King Darius I, despite his much larger forces. The Athenian general was Miltiades. Darius wouldn't return but his son Xerxes attempted to materialize his father's dream 10 years later. Western scholars deem this one of the most significant battles in world history.

Naval battle of Salamís (480 BC), Battle of Mycale (479 BC) and the Battle of Plataea (479 BC). Greek victories. In the Battle of Plataea, the Greeks finally manage to create a big army (for Greek standards). This was the final battle that ended the Persian ambitions over Greek territory once and for all.

Many important battles took place during the Peloponnesian War (431 - 404 BCE) but since this was just something that we nowadays would call a hell of a civil war, I don't think it matters a lot to analyze it here. Just imagine literally everyone fighting literally everyone.

Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC). While this is a battle belonging to the great sphere of the violent infighting started and perpetuated after the Peloponnesian War, I'm gonna mention this one because it did change history forever. King Philip II of Macedon alongside the Epirotes, Thessalians, Aetolians, Phoceans and Locrians defeat the usual elites of the Athenians, Thebans, Corinthians, Achaeans, the Chalcidians of Euboea and the Epidaurians. This begins the Macedonian hegemony over Greece, that will lead towards the dissolution of the Greek city-states, the disempowerment of mighty Athens and Sparta, but also the rise of the Macedonian Empire and a more unified sense of Greek identity, in the grand scheme of things.

We talking great battles, right? Not just “side of the angels”... Greeks have given historically significant battles where they were on the offensive, too.

Battle of Issus (333 BC). The Hellenic League led by Alexander the Great defeats the Persian Empire and acquires Asia Minor.

Battle of Gaugamela (331 BC). Under Alexander, Greeks take full control of the Persian Empire.

Battle of the Hydaspes (326 BC). Alexander marches against what is modern-day Pakistan and reaches the outskirts of India.

And we should mention the history-changing defeats:

Pyrrhic War (280–275 BC). The Greek King Pyrrhus of Epirus was asked by the Greeks of South Italy to help them against the rising and expanding Roman Republic. Pyrrhus indeed gave great and demanding fights on their behalf, nearly all of them victories, however these victories were so costly that in the end they turned against the exhausted Greek populations. His victories were soon overturned by the Romans, making famous the phrase “Pyrric victory”, which roughly means “winning the battle and losing the war”.

Battle of Pydna (168 BC). After an initial Greek advantage, Romans eventually defeat the Macedonians and take control of the northern Greek lands.

Battle of Corinth (146 BC). Romans utterly destroy the city of Corinth in the Greek South and assume power over the entirety of Greece, which becomes part of the Roman Empire.

War of Actium (32-30 BC). Long story short, the Romans acquire more and more of the lands once taken by the Greeks. The Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt has been going through civil wars, harbored by the Romans. In the War of Actium taking place in Greece and Egypt, Cleopatra and her Roman ally Mark Anthony are defeated by the Roman Emperor Octavian. This is a defeat of the Egyptian people but also the last nail in the coffin of Greek hegemony in the ancient world.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

“How Reliable is Herodotus’ Account of the Persian Wars?

Answer by Paul Cartledge

Herodotus was not just any old historian but the founder of an entire intellectual discipline and practice, or craft, the one that I am honoured to try my hand at myself. Opinions differ today, as they always have done, on what exactly a historian’s chief task or aim should be, but Herodotus made a pretty good stab at adumbrating it in the famous Prooimion or Preface to his Histories (‘Researches’, ‘Enquiries’): he wished both to record for posterity and to celebrate ‘great and wonderful deeds or achievements (erga)’ and – above all, N.B. – to explain them. In his particular case what he wished to explain above all was why and how and thanks to whose responsibility Greeks and non-Greeks (principally Persians) had come to fight each other.

He had in mind as his subject what we today call the ‘Persian Wars’ or (more accurately) Helleno-Persian Wars, as those were fought out by land and sea on either side of the Aegean at the far eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea between 490 (Battle of Marathon) and 479 BC/BCE – or from 499 to 479, if one includes also the essential preliminary ‘Ionian Revolt’ (499-4), since this was the first occasion on which Greeks, then many of them subjects of the mighty Persian empire, had engaged in warfare with their ‘barbarian’ (non-Greek) masters in pursuit of the ideal of political freedom. That (unsuccessful) revolt gave Herodotus, himself an Eastern Greek from Asia Minor (Halicarnassus) and born c. 485 a Persian subject into a mixed Greek-barbarian family, his own dominant theme.

It was always clear to Herodotus where his linear chronological narrative would end – 479, with the final victory for those (few) Greek cities led by Sparta and Athens who had dared to resist the intended Persian conquest of all mainland Greece led by Emperor Xerxes. But where to begin? Herodotus boldly chose what we call the mid-6th century or c. 550 BCE for his starting point, but how could he possibly claim to know or at any rate confidently believe anything at all about events and processes ongoing some 70 years or two to three generations before his own birth? Given that he seems not to have been able to speak or read any language other than his own Greek (he wrote in the Ionic dialect but spoke in Doric), and given that the Hellenic world of the mid-6th century was not a world either of extensive official public documentation or of extensive prose-writing of a descriptive, factual nature, he had no choice but to become not only the world’s first historian but also the world’s first oral historian. That is to say, the chief type of evidence – not quite the only, since he does quote some documents and cite some physical monuments– that he gathered from about 450 to 430 was the oral testimony of either face-to-face or second-hand informants. Those informants moreover were either native Hellenophones or non-Greeks with a sufficient command of Greek.

It is hugely to his credit that Herodotus evolved a sophisticated hierarchy of value in interpreting such oral testimony, a hierarchy according to reliability. Top of the table was what he called opsis, or autopsy, meaning first-hand testimony whether of his own or of those of his informants who had actually viewed or participated in the events related, including evidence of physical monuments (another meaning of erga). After that, some way after, came what he called akoê or hearsay evidence, evidence that might reliably go back ultimately as far as two to three generations (but no farther) before his own time. Both types of evidence however were then further subjected to the reliability test: were his informants to be trusted – or might there perhaps be reasons why they would provide him knowingly or unknowingly (‘false memory syndrome’) with false testimony both as to facts and as to their interpretation?

At this point it’s necessary to state unequivocally that Herodotus was in no way an official historian, indeed his work has been characterised as the very denial of official history – that is, of the sort of records – or propaganda sheets – put out by middle eastern rulers or priestly castes. But even if he was not compiling and composing in the interests of any particular state or power-group, does that mean he was always himself disinterested either in what he chose to relate or in how he chose to relate it? Here Herodotus is vulnerable to two kinds of negative critique: first, that in interpreting the deeds of humans he nevertheless was too quick to invoke the notion of supernatural or divine intervention as an explanatory mode, that he was in short too theological; second, that he did not always sufficiently perceive the bias of his informants, whether they were members of an aristocratic Athenian family or members of a hereditary Egyptian priesthood. Both those critiques seem to me to have some force. And Herodotus himself was clearly very aware of the second: in response he claimed, somewhat speciously, that it was his job to ‘relate what he was told’ and that it shouldn’t be assumed he necessarily believed it. (I should probably here add that I do not myself believe the hyper-criticisms that have been levelled at Herodotus since antiquity, to the effect that he just made things up, or that, for example, he didn’t in fact view the monuments and cities abroad such as Babylon that he claimed or implied he had seen.)

Reliability, finally, operates on several levels – from a particular detail of his account of say the finally decisive Battle of Plataea all the way up to the alleged motivation of Xerxes in planning and effecting his simply massive expedition (though not as massive as Herodotus believed – here he was certainly guilty of considerable factual inaccuracy). If we make due allowance for an excess of theology, for a weakness for large numbers, and for an occasional prejudice in favour of or against a particular key player (for Athens at the Battle of Salamis, for instance, or against King Cleomenes I of Sparta and Themistocles, or – as Plutarch vehemently protested – medizing Thebes), then I think we may confidently say that Herodotus’ historical judgement is remarkably reliable given the conditions in which it had to be exercised.

I have left to the end a bit of a ‘stinger’. Almost all that I have written above applies to Herodotus the historian of the Helleno-Persian Wars conceived pretty much as we would frame that still vitally important topic today. Herodotus, however, deployed and depicted a far broader and richer canvas, since besides being that historian he was also what we would call today a pioneer ethnographer and comparative social anthropologist, interested to discover and compare the nomoi – laws and customs – of a multiplicity of non-Greek peoples living adjacent to the Hellenes, above all others the Egyptians (book 2) and a variety of what he called ‘Scythians’ (book 4). In this area Herodotus’s vulnerability to deception, disinformation or sheer ignorance was far greater, and his reliability correspondingly far smaller.

Further Reading suggestions: With apologies for apparent self-promotion, I develop the above discussion at greater length in my introduction to Tom Holland’s bold new Penguin Classics translation (London 2014). See also my 2017 (Chalke Valley History Festival) History Hub blogpost. An inventive way of re-reading Herodotus is William Shepherd’s The Persian War in Herodotus and Other Ancient Voices (Oxford 2019). A particularly good ‘very short introduction’ to Herodotus is Jennifer T. Roberts’ Herodotus (Oxford 2011). Roberts is also the editor of the excellent Norton Critical Edition of the Histories as translated by Walter Blanco and accompanied with a wide variety of supporting essays by Blanco (London 2013).’

Source: the site of Herodotus Helpline ( https://herodotushelpline.org/how-reliable-is-herodotus-account-of-the-persian-wars/).

Very good text from a very important Classicist. My only criticism is that I think that Pr. Cartledge does not take sufficiently into account the fact that Herodotus’ ethnography, despite its inevitable flaws and errors, offers often accurate and important information on the customs of non-Greek peoples (and even in other cases in his ethnography, in which Herodotus is mostly wrong, there is a kernel of truth in what he relates or at least he preserves aspects of how some ancient peoples of his time showed themselves, their past, and their neighbors).

3 notes

·

View notes