#celtic reconstruction

Text

A start of shift prayer:

Gorfannon the Smith, guide my hand.

Amaethon of the Plough, give strength to my back.

Let me lose myself in my labours and find peace in my toil,

May my efforts be fruitful and my respite well earned.

#old gods#celtic gods#welsh mythology#welsh gods#ancient celts#celtic mythology#celtic#celtic reconstruction#mabinogi#mabinogion#paganism#pagan gods#pagan#celtic paganism#celtic polytheism#prayer#celtic pantheon

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is the most important part of your daily ritual?

Prayer obviously is the core of any theology. This is something I've done from sunrise to sunset. This is because of liminality, the space between this waking world and the sleeping one, and over meals I've prepared for myself and / or more junk food.

A simple 'cellsing' means Hail in cymraeg; does the trick.

I tend to put on some sort of clean 100% cotton garment over my head. Plastic/polyester is a plant and animal killer and destroys natural land made for land fills. (Though you can obviously DIY things, i dont recommend all of it being resin, or digital even if its what you can afford at the time) I have a prayer book I keep under lock and key. And my shrine for the divine in question faces to the left of my living space. This is due to both Arawn being of the left hand path and natural sunlight replacing an electric bulb that would not have been needed nor invented during midevil wales.

#welsh polytheism#cymraeg polytheism#submission post#arawnsworn#arawndeity#veiling pagan#welshreconstructionist#celtic reconstruction

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lakáskultúra a vaskortól a középkor hajnaláig

A Kárpát-medencében a vaskortól kezdődően több mint másfél ezer évig a lakóépületek egységes szerkezettel és technikával készültek. Ez azt jelenti, hogy a nagy méretű, hosszú házak helyett sokkal kisebb, lemélyített gödörre húztak fel falakat és tetőt.

Legelőször a szkítákhoz köthető Vekerzug kultúránál lehetett megfigyelni, hogy kerek, vagy négyszögletes lemélyítést használtak házalapnak. A gödör belsejében, illetve a külső széleken megtalálható cölöphelyek mutatják, hogy a felmenő szerkezet és a tetőzet miképpen képzelhető el. A falat vesszőfonatra tapasztott paticsból készítették, a tető pedig valószínűleg nádból volt. Régészeti bizonyítékok az előbbiből maradnak meg csupán.

1. kép: Szkíta kultúrához köthető kerek alaprajzú ház

2. kép: Szkíta kultúrához köthető szögletes alaprajzú ház

A La Tène kultúra, vagyis a kelta megtelepedés idején egységesen téglalap alaprajzú földbe mélyített vagy úgynevezett veremházakkal számolhatunk. Ez tulajdonképpen az előző típus letisztult változata. Tőlünk nyugatra élt kelta törzsek (Cseh-, Német-, Franciaország és az Egyesült Királyság területén) összetettebb technikájú, kőfalazással készült, általában kör alaprajzú házakban laktak.

3. kép: Nyugat-európai kelta kerek ház rekonstrukciós rajza

4. kép: Ménfőcsanakon feltárt földbe mélyített házak rekonstrukciós rajza (Szőnyi, E.: Römerzeitliche Altansässigensiedlung von Ménfőcsanak (Umgebung von Győr). Arh. vest. 47, 1996, 249-256.

Itt már felmerül a kérdés, hogy mitől másabb a Kárpát-medence házépítési divatja?

Egyáltalán hányan laktak egy ilyen 6-10-15 m2-es alaprajzú épületben? Hogyan fűtöttek?

Sok hasonló kérdésre a kutatás ma is keresi választ, hiszen a római császárkor idején Pannonia provincia és a környező Barbaricum területén is ugyanezeket a földbe mélyített épületeket használták a falusias településeken. Ezen felül még az avaroknál és a már letelepült magyaroknál is ezt a házszerkezetet találjuk meg.

A miértekre a válaszok még vita tárgyát képezik, de az ilyesfajta változás a lakáskultúrában valószínűleg több különböző okra vezethető vissza. Az egyik ilyen a nyersanyagok hozzáférhetősége - követ nehezebb volt beszerezni, mint például fát, agyagot és nádat. Egy ilyen egyszerű szerkezetű házat viszonylag gyorsan fel lehetett építeni és javítani is könnyebb volt. A nagyállattartó nomád, vagy félnomád népek, mint a szkíta vagy a szarmata kultúra is könnyebben elsajátíthatta egy ilyen épület felépítését, a tartósan letelepült népeknél pedig az egyszerűség is fontos szempont lehetett.

Klimatikus viszonyok is szóba jöhetnek, azonban jelentős felmelegedés a késő vaskorban következett be. Ehhez képest belső tűzhelyet nem minden esetben lehetett megfigyelni. Ezt a jelenséget több módon próbálták magyarázni (komoly és kevésbé komoly ötletekkel), de egyik sem tudott teljesen megnyugtató módon választ adni: csak a parazsat vitték be az épületbe, elég volt összebújni, hogy ne fázzanak, nem is volt olyan hideg stb. Felvetődött, hogy nem is lehet a tűzhely nélküli építményeket lakóházaknak tekinteni, viszont akadnak olyan lelőhelyek, ahol csak ilyen típusú épületek kerültek elő. Tény, hogy a földbe mélyített házak jelentős része műhely volt vagy gazdasági célt szolgált, de ebben az időszakban nem biztos, hogy a háziipari tevékenységek (pl.: szövés-fonás) teljes mértékben elválaszthatóak az élettértől.

5. kép: Kelta fazekasműhely

6. kép: Kelta házbelső rekonstrukciója, Nemzeti Múzeum, Prága

Itt már a különböző méretek meglétére is megkaptuk a választ, hiszen egy 6 m2-es gödör négy fallal és tetővel még egy garzonnak is sovány.

Ha elfogadjuk, hogy a lakóépületekhez csak a 10 m2 feletti épületek tartoznak még mindig kérdéses, hány embernek volt ez elég? Ezekre a választ nem tudjuk megadni, kivéve, ha előkerül egy korabeli postaláda, vagy lakcímnyilvántartás. Annyi biztos, hogy az őskor korábbi időszakaihoz képest maga a lakóközösség összement, talán egy kisebb vagy közepes méretű családnyira. Falusias jellegű településeknél felvetődik, hogy az emberek sokkal több időt töltöttek el a természetben, földeken, de természetesen még ez sem jelenti azt, hogy egy esős hétvégén valakinek mindig kint kellett volna áznia, mert bent nem volt elég ülőhely.

Meg kell említeni egy másik háztípust, aminek régészeti nyomát nehéz, vagy egyáltalán nem lehet megfigyelni. Ilyenek a fából készült cölöpös, vagy boronaházak, amelyek kevés esetben mélyültek le az altalaj szintjéig, ahol a régészeti feltárás zajlik. Nagyon szerencsés körülmények kellenek az ilyen típusú épületek megtalálásához. Ugyanebbe a kategóriába sorolhatók a felszínen meglévő jurták, vagy sátrak, amelyek főleg a nomád életmódot folytató népeknél kerülhetnek szóba.

Ami a jövőben segítheti az ilyen régészeti objektumok megértését, az a részletes, természettudományos vizsgálatokkal egybekötött kutatás. A hasonlóan mélyreható vizsgálatok céljai a régészek és történelemkedvelők kíváncsiságának csillapításán túl még az, hogy megtudjuk a régi korokban hogyan tudott alkalmazkodni az ember a változásokhoz (természeti, gazdasági, stb).

7. kép: Kelta ház elszenült cölöpjének a darabja. Vizsgálata által nem csak a fafajta, de kivágásának ideje és a környezeti viszonyok is megismerhetők.

#hermanottómúzeum#homrégészet#ironage#miskolcimúzeum#régészet#vaskor#ház#házak#lakás#household#household archaeology#laténe#celtic#scythian culture#reconstruction#némethattila

42 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

You Don't Have to be Born in Ireland to Learn Irish Paganism - Lora O'Br...

I would really recommend this video. There is far too much racism in Irish pagan spaces, both overt and more insidious. I see so many Irish pagans on here (usually in NA but not exclusively) peddle disturbing ideas of DNA percentages and how this relates to Irishness. Ideas that cause direct harm to the black and brown people in Ireland.

Also touches on the American colonialist entitlement that is so prevalent here and the idea that evil Irish people are purposefully trying to gatekeep anything Irish. Irish people love sharing our culture, but having it decontextualised and reduced to caricatures is not sharing. It is appropriation, cultural appropriation. Please understand that this isn’t a random book or fandom this part of a culture that many people lived and died to keep, real people.

I think a lot of the anti-Irish resentment in Irish pagan spaces does come from a place of insecurity and I hope this video alleviates some of that insecurity, you have every right to practice but please do so respectfully.

(Standard disclaimer, Lora O'Brien is known for being condescending and short with people and is constantly trying to push her payed classes, which while good, are a matter of paying for convenience, all the information is already out there. This is just who she is as an individual, not a representation of every Irish person)

#irish reconstruct#gaelpol#irish paganism#gaelic paganism#celtic paganism#A really good video#besides from the shilling of her classes#which really arent vital#tbh use her resource guide and z library done#I really hope some people watch this video beacuse its really needed#irish revivalism

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can't wait to get my drivers license just so I can force people to listen to the music I like while I drive them around

0 notes

Text

The Stafford Road Man

Alright? You can call me Stafford Road Man. I was part of the earliest groups of Saxons to migrate to Britain after the fall of that pesky Roman Empire in around 500 CE. I lived longer than any of my other First Folks peers, dying at around 45. I had arthritis in my spine, shoulders, and hips, but was most likely a strong and powerful warrior back in my day! I was hit hard in the back on my leg, causing me to walk with a limp, and even had a broken rib that managed to heal. Nothing could keep me down! …Except maybe a bad tooth. I had a large abscess at the front of my mouth which, let me tell you, was unbelievably painful, and eventually gave me blood poisoning and killed me. Shame, innit?

#history#ancient history#anthropology#archaeology#sussex#east sussex#saxon#anglo saxon#reconstruction#wax work#wax figure#celtic#text#mine

1 note

·

View note

Text

If you don't know how old something is, it's also fun to just ... see the fog of history as a feature.

#sorry the post went around again about beliefs and how old they are. GRAND post#but I thought again how even if I put a lot of time into researching Ireland's ancient beliefs it's hard to reconstruct something#pre-christian. HOWEVER that is fun in the myth AU where Harry is a mortal king but also so clearly superpowered.#like we don't know if all heroes from ancient celtic stories are supposed to be gods but we can guess#but instead of giving a concrete answer about his divine nature let's just leave it up in the air and make him ridiculously gifted#Paddy? Giant. Charlie? Changeling. Harry and Soph? Human ...????? Who knows. The mystery is the spice ~#but also the myth AU goes from fuck me 700 BCE to 1200 AD. Idk the timeline in that bitch everyone is just co-existing#beablabbers

0 notes

Text

So I got this tag on my answer to an ask about when it became acceptable for western women to wear pants, and you know it's all I need to go on a tangent.

I think the short answer here would be men have worn skirts as long as people have worn anything, so pretty long tbh. But since I am incapable of answering anything shortly, I think we can re-frame this question:

When did skirts stop being socially acceptable for men?

So let's start with acknowledging that tunics, togas, kirtles and such men wore through history were, in fact, skirts. I think there's often a tendency to think of these as very different garments from those that women wore, but really they are not. Most of the time they were literally referred to with the same name. (I will do a very broad and simplified overview of men's clothing from ancient times to Early Middle Ages so we can get to the point which is Late Middle Ages.)

Ancient Greek men and women both wore chitons. Even it's length wasn't determined by gender, but by occupation. Athletes, soldiers and slaves wore knee-length chitons for easier movement. Roman men and women wore very similar garment, tunics. Especially in earlier ancient Rome long sleeves were associated with women, but later became more popular and unconventional for men too. Length though was still dependent on occupation and class, not gender. Toga was sure men's clothing, but worn over tunic. It was wrapped around the waist, like a dress would, and then hung over shoulder. Romans did wear leggings when they needed to. For example for leg protection when hunting as in this mosaic from 4th century. They would have been mostly used by men since men would be doing the kinds of activities that would require them. But that does not lessen the dressyness of the tunics worn here. If a woman today wears leggings under her skirt, the skirt doesn't suddenly become not a skirt.

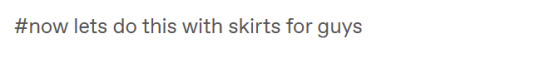

All over Europe thorough the early Middle Ages, the clothes were very similar in their basic shape and construction as in Rome and Greece. In Central and Northern Europe though people would wear pants under shorter tunics. There were exceptions to the everyone wearing a tunic trend. Celtic men wore braccae, which were pants, and short tunics and literally just shirts. Celts are the rare case, where I think we can say that men didn't wear dresses. Most other peoples in these colder areas wore at least knee-length tunics. Shorter tunics and trousers were worn again mostly by soldiers and slaves, so rarely any other woman than slave women. The trousers were though definitely trousers in Early Middle Ages. They were usually loose for easier construction and therefore not that similar to Roman leggings. However leggings style fitted pants were still used, especially by nobility. I'd say the loose trousers are a gray area. They wore both dresses and pants, but still definitely dresses. I'd say this style was very comparable to the 2000s miniskirts over jeans style. First one below is a reconstruction of Old Norse clothing by Danish history museum. The second is some celebrity from 2005. I see no difference.

When we get to the high Middle Ages tunics are still used by both men and women, and still it's length is dependent on class and activity more than gender, but there's some new developments too. Pants and skirt combo is fully out and leggings' are back in in form of hose. Hose were not in fact pants and calling them leggings is also misleading. Really they are socks. Or at least that's how they started. As it has become a trend here they were used by everyone, not just men. During early Middle Ages they were worn often with the trousers, sometimes the trousers tucked inside them making them baggy. In high Middle Ages they became very long when used with shorter tunics, fully displacing the need for trousers. They would be tied to the waist to keep them up, as they were not knitted (knitting was being invented in Egypt around this time, and some knitting was introduced to Europe during middle Ages, but it really only took off much later during Renaissance Era) and therefore not stretchy. First picture is an example of that from 1440s. Another exciting development in the High Medieval era was bliaut in France and it's sphere of influence. Bliaut was an early attempt in Europe of a fitted dress. And again used by both men and women. The second illustration below from mid 12th century shows a noble man wearing a bliaut and nicely showing off his leg covered in fitted hose. Bliaut was usually likely fitted with lacing on the sides, but it wasn't tailored (tailoring wasn't really a thing just yet) and so created a wrinkled effect around the torso.

In the 14th century things really picked up in European fashion. European kingdoms finally started to become richer and the rich started to have some extra money to put into clothing, so new trends started to pop up rapidly. Tailoring became a thing and clothes could be now cut to be very fitted, which gave birth to fitted kirtle. At the same time having extra money meant being able to spend extra money on more fabric and to create very voluminous clothing, which gave birth to the houppelande.

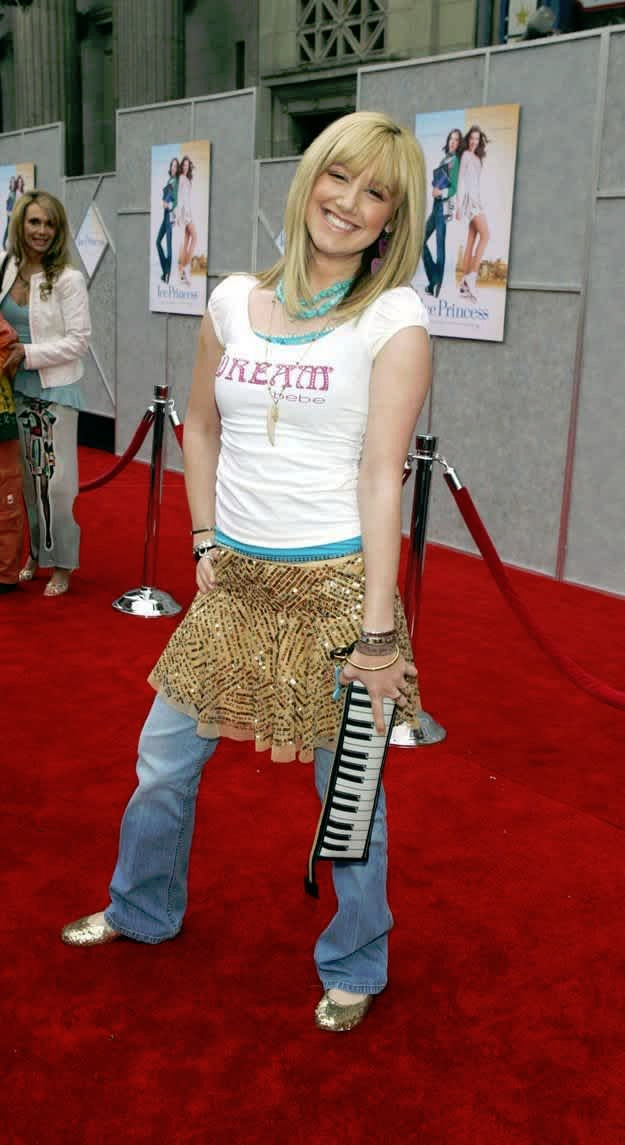

Kirtle was once again worn by everyone. It wasn't an undergarment, for women that would be shift and men shirt and breeches, but it was an underlayer. It could be worn in public but often had at least another layer on top of it. The bodice part, including sleeves were very fitted with lacing or buttons (though there were over-layer kirtles that had different sleeves that changed with fashions and would be usually worn over a fitted kirtle). Men's kirtles were short, earlier in 14th century knee-length but towards the end of the century even shorter styles became fashionable in some areas. First picture below shows a man with knee-length kirtle from 1450s Italy.

Houppelande was also unisex. It was a loose full-length overgown with a lot of fabric that was gathered on the neckline and could be worn belted or unbelted. The sleeves were also wide and became increasingly wider (for men and women) later in the century and into the next century. Shorter gowns similar in style and construction to the houppelande were also fashionable for men. Both of these styles are seen in the second picture below from late 14th century.

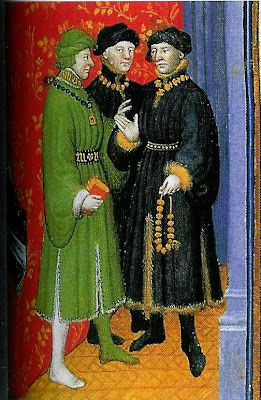

In the very end of 14th century, first signs of pantification of men can be seen. In France and it's sphere of influence the skirt part of the kirtle became so short it barely covered the breeches as seen below on these fashionable musicians from 1395-1400 France. Long houppelandes, length ranging from floor to calf, were still used by men though (the second picture, 1414 France), as were knee and thigh length gowns of similar loose style.

The hems continued to be short through the 15th century in France, but in other places like Italy and German sphere of influence, they were still fairly long, at least to mid thigh, through the first half of the century. In France at some point in late 13th century the very short under-kirtle started to be called doublet and they are just getting shorter in 1400s. The showing underwear problem was fixed by joined hose and the codpiece, signaling the entrance of The Sluttiest Era of men's fashion. Below is an example from 1450s Belgium of doublet and early codpiece in display. As you can see from the other figures, the overgowns of the previous century were also getting very, very short. In the next French example below from 1470s we can see the skirt shrink out of existence right before our eyes.

The very skimpy doublet and it's accompanying codpiece spread to the rest of the Europe in the second half of 15th century and it would only get sluttier from there. The Italians were just showing their full ass (example from 1490s). The dress was not gone yet though. The doublet and codpiece continued to be fashionable, but the overdress got longer again in the French area too. For example in the second example there's Italian soldiers in a knee length dresses from 1513.

But we have to talk about the Germans. They went absolutely mad with the whole doublet and codpiece. Just look at this 1513 painting below (first one). But they did not only do it sluttier than everyone else, they also changed the course of men's fashion.

Let's take a detour talking about the Landsknecht, the mercenary pikeman army of the Holy Roman Empire. (I'm not that knowledgeable in war history so take my war history explanation with a grain of salt.) Pikemen had recently become a formidable counter-unit against cavalry, which earlier in the Medieval Era had been the most important units. Knights were the professional highly trained cavalry, which the whole feudal system leaned against. On the other hand land units were usually not made of professional soldiers. Landsknecht were formed in late 15th century as a professional army of pikemen. They were skilled and highly organized, and quickly became a decisive force in European wars. Their military significance gave them a lot of power in the Holy Roman Empire, some were even given knighthood, which previously wasn't possible for land units, and interestingly for us they were exempt from sumptuary laws. Sumptuary laws controlled who could wear what. As the bourgeois became richer in Europe in late Middle Ages and Renaissance Era, laws were enacted to limit certain fabrics, colors and styles from those outside nobility, to uphold the hierarchy between rich bourgeois and the nobles. The Landsknecht, who were well payed mercenaries (they would mutiny, if they didn't get payed enough), went immediately absolute mad with the power to bypass sumptuary laws. Crimes against fashion (affectionate) were committed. What do you do, when you have extra money and one of your privileges is to wear every color and fabric? You wear every color and fabric. At the same time. You wear them on top of each other and so they can be seen at the same time, you slash the outer layer. In the second image you can feast your eyes on the Landsknecht.

Just to give you a little more of that good stuff, here's a selection of some of my favorite Landsknecht illustrations. This is the peak male performance. Look at those codpieces. Look at those bare legs. The tiny shorts. And savor them.

The Landsknecht were the hot shit. Their lavish and over the top influence quickly took over men's fashion in Germany in early 1500s. Slashing, the technique possibly started by them, but at least popularized by them, instantly spread all over Europe. That's how you get the typical Renaissance poof sleeves. They at first slashed the thighs of their hose, but it seems like to fit more of everything into their outfits, they started wearing the hose in two parts, upper hose and nether hose, which was a sort of return to the early Medieval trousers and knee-high hose style. The two part hose was adopted by the wider German men's fashion early in the century, but already in 1520s had spread to rest of Europe. It was first combined with the knee-length overdress that had made it's comeback in the turn of the century, like in this Italian painting from 1526 (first image). At this point knitting had become established and wide-spread craft in Europe and the stockings were born, replacing nether hose. They were basically nether hose, but from knitted fabric. The gown shortened again and turned into more of a jacket as the trunk hose became increasingly the centerpiece of the outfit, until in 1560s doublet - trunk hose combination emerged as the standard outerwear (as seen in the second example, 1569 Netherlands) putting the last nail on the coffin of the men's dress as well as the Sluttiest Era. The hose and doublet became profoundly un-slutty and un-horny, especially when the solemn Spanish influence spread all over with it's dark and muted colors.

Especially in Middle Ages, but thorough European history, trousers have been associated with soldiers. The largely accepted theory is that trousers were invented for horse riding, but in climates with cold winters, where short skirts are too cold, and long skirts are still a hazard when moving around, trousers (with or without a short skirt) are convenient for all kinds of other movement requiring activities like war. So by adopting hose as general men's clothing, men in 1500s associated masculinity with militarism. It was not a coincidence that the style came from Landsknecht. I may have been joking about them being "peak male performance", but really they were the new masculine ideals for the new age. At the time capitalism was taking form and European great powers had begun the process of violently conquering the world for money, so it's not surprising that the men, who fought for money and became rich and powerful doing so, were idealised.

Because of capitalism and increasingly centralized power, the feudal system was crumbling and with it the feudal social hierarchy. Capitalism shifted the wealth from land ownership (which feudal nobility was built upon) to capital and trade, deteriorating the hierarchy based on land. At the same time Reformation and centralized secular powers were weakening the power of the Church, wavering also the hierarchy justified by godly ordain. The ruling class was not about to give up their power, so a new social hierarchy needed to form. Through colonialism the concept of race was created and the new hierarchy was drawn from racial, gender and wealth lines. It was a long process, but it started in 1500s, and the increasing distinction between men's and women's fashions was part of drawing those lines. At the same time distinctions between white men and racialized men, as well as white women and racialized women were drawn. As in Europe up until this point, all over the world (with some exceptions) skirts were used by everyone. So when European men fully adopted the trousers, and trousers, as well as their association to military, were equated with masculinity, part of it was to emasculate racialized men, to draw distinctions.

Surprise, it was colonialism all along! Honestly if there's a societal or cultural change after Middle Ages, a good guess for the reason behind it is always colonialism. It won't be right every time, but quite a lot of times. Trousers as a concept is of course not related to colonialism, but the idea that trousers equal masculinity and especially the idea that skirts equal femininity are. So I guess decolonize masculinity by wearing skirts?

#this has been sitting in my drafts almost finished for like a year or something#historical fashion#fashion history#fashion#history#dress history#men's historical fashion#renaissance fashion#medieval fashion#western fashion#western fashion history#landsknecht

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The gods of Gaul: Introduction, or why it is so hard to find anything

As I announced, I open today a series of post covering what some can call the "Gaulish mythology": the gods and deities of Ancient Gaul. (Personal decision, I will try avoiding using the English adjective "Gaulish" because... I just do not like it. It sounds wrong. In French we have the adjectif "Gaulois" but "Gaulish"... sounds like ghoulish or garrish, no thank you. I'll use "of Gaul", much more poetic)

[EDIT: I have just found out one can use "Gallic" as a legitimate adjective in English and I am so happy because I much prefer this word to "Gaulish", so I'll be using Gallic from now on!]

If you are French, you are bound to have heard of them one way or another. Sure, we got the Greek and Roman gods coming from the South and covering up the land in temples and statues ; and sure we had some Germanic deities walking over the rivers and mountains from the North-East to leave holiday traditions and folk-beliefs... But the oldest gods of France, the true Antiquity of France, was Gaul. And then the Roman Gaul, and that's already where the problems start.

The mythology of Gaul is one of the various branches of the wide group known as Celtic mythology or Celtic gods. When it comes to Celtic deities, the most famous are those of the British Isles, due to being much more preserved (though heavily Christianized) - the gods of Ireland and the Welsh gods are typically the gods every know about when talking about Celtic deities. But there were Celts on the mainland, continental Celts - and Gaul was one of the most important group of continental Celts. So were their gods.

Then... why does nobody know anything about them?

This is what this introduction is about: how hard it actually is to reconstruct the religion of Gaul and understand its gods. Heck we can't ACTUALLY speak of a Gaulish mythology because... we have no myth! We have not preserved any full myth or complete legend from Ancient Gaul. The pantheon of Gaul is the Celtic pantheon we probably know the least about...

Why? A few reasons.

Reason number one, and the most important: We have no record of what the Gauls believed. Or almost none. Because the people of Gaul did not write their religion.

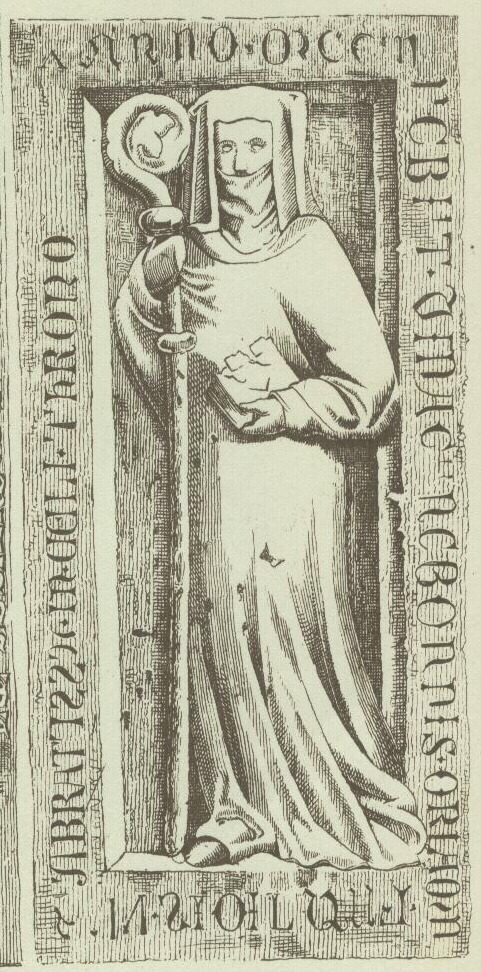

This is the biggest obstacle in the research for the gods of Gaul. It was known that the art of writing was, in the society of Gaul, an elite art that was not for the common folks and used only for very important occasions. The druids were the ones who knew how to read and write, and they kept this prerogative - it was something the upper-class (nobility, rulers) could know, but not always. Writing was considered something powerful, sacred and magical not to be used recklessly or carelessly. As a result, the culture of Gaul was a heavily oral one, and their religion and myths were preserved in an oral fashion. Resulting in a great lack of written sources comng directly from the Gallic tribes... We do have written and engraved fragments, but they are pieces of a puzzle we need to reconstruct. We have votive offerings with prayers and demands inscribed on it - and while they can give us the names of some deities, they don't explain much about them. We have sculptures and visual representations of the deities on pillars and cups and jewels and cauldrons - but they are just visuals and symbols without names. We have calendars - but again, these are just fragments. We have names and images, and we need to make sense out of it all.

To try to find the explanations behind these fragments, comparisons to other Celtic religions and mythologies are of course needed - since they are all branches of a same tree. The same way Germanic mythology can be understood by looking at the Norse one, the same way Etruscan, Greek and Roman mythologies answer each other, the mythology and religion of Gaul has echoes with the Celtic deities of the Isles (though staying quite different from each other). The other comparison needed to put things back into context is reason number 2...

Reason number two: The Romans were there.

Everybody knows that the death of Ancient Gaul was the Roman Empire. Every French student learns the date of Alesia, the battle that symbolized the Roman victory over the Gallic forces. Gaul was conquered by the Romans and became one of the most famous and important provinces of the Roman Empire: it was the Gallo-Roman era.

The Romans were FASCINATED by Gaul. Really. They couldn't stop writing about them, in either admiration or hate. As a result, since we lack direct Gallic sources, most of what we know about Ancient Gaul comes from the Romans. And you can guess why it is a problem. Some records of their religion were written in hatred - after all, they were the barbarian ennemies that Romans were fighting against and needed to dominate. As such, they contain several elements that can be put in doubt (notably numerous references to brutal and violent human sacrifices - real depictions of blood-cults, or exaggeratons and inventions to depict the gods of Gaul as demonic monstrosities?) But even the positive and admirative, or neutral, records are biased because Romans kept comparing the religion of the Gauls to their own, and using the names of Roman deities to designate the gods of Gaul...

Leading to the other big problem when studying the gods of Gaul: the Roman syncretism. The Gallo-Roman era saw a boom in the depictions and representations of the Gallic gods... But in their syncretized form, fused with and assimilated to the Roman gods. As such we have lots of representations and descriptions of the "Jupiter of Gaul", of the "Mercury of Gaul", of the "Gallic Mars" or "Gallic Minerva". But it is extremely hard to identify what was imported Roman elements, what was a pure Gallic element under a Roman name, and what was born of the fusion of Gallic and Roman traditions...

Finally, reason number three: Gaul itself had a very complicated approach to its own gods.

We know there are "pan-gallic" gods, as in gods that were respected and honored by ALL the people of Gaul, forming the cohesion of the nation. But... Gaul wasn't actually a nation. It was very much like the many city-states of Greece: Ancient Gaul was unified by common traditions, a common society, a common religion and a common language... But Gaul was a tribal area divided into tribes, clans and villages, each with their own variations on the laws, each with their own customs and each with their own spin on religion. As a result, while there are a handful of "great gods" common to all the communities of Gaul, there are hundreds and hundreds of local gods that only existed in a specific area or around a specific town ; and given there were also many local twists and spins on the "great gods", it becomes extremely hard to know which divine name is a local deity, a great-common god, a local variation on a deity, or just a common nickname shared by different deities... If you find a local god, it can be indeed a local, unique deity ; or it can be an alternate identity of a shared divine archetype ; or it can be a god we know elsewhere but that goes by a different name here.

To tell you how fragmented Gaul was: Gaul was never a unified nation with one king or ruler. The greatest and largest division you can make identifies three Gauls. Cisalpine Gaul, the Gaul located in Northern Italy, conquered by the Romans in the second century BCE, and thus known as "the Gaul in toga" for being the most Roman of the three. Then there was the "Gaul in breeches" (la Gaule en braies), which borders the Mediterranean sea, spanning between the Alps and the Pyrenean mountains, and which was conquered in the 117 BCE (becoming the province of Narbonne). And finally the "Hairy Gaul", which stayed an independant territory until Cesar conquered it. And the Hairy Gaul itself was divided into three great areas each very different from each other: the Aquitaine Gaul, located south of the Garonne ; the Celtic Gaul located between the Garonne and the Marne (became the Gaul of Lyon after the Roman conquest) ; and finally the Belgian Gaul, located between the Marne and the Rhine. And this all is the largest division you can make, not counting all the smaller clans and tribes in which each area was divided. And all offering just as many local gods or local facets of a god...

And if it wasn't hard enough: given all the sculptures and visuals depictions of the gods of Gaul are very "late" in the context of the history of Gaul... It seems that the gods of Gaul were originally "abstract" or at least not depicted in any concrete form, and that it was only in a late development, shortly before the Roman invasions, that people of Gaul decided to offer engravings and statues to their gods, alternating between humanoid and animal forms.

All of this put together explains why the gods of Gaul are so mysterious today.

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weiße Frauen / White Ladies

White ladies are ghosts that are said to have haunted several castles of European noble families.

The oldest reports of the apparition date from the 15th century, but belief in the white ladies was most widespread in the 17th century. Although there are similarities to other female ghosts in European folk belief – for example the Irish and Celtic banshee – the white lady is a phenomenon that first emerged in and was typical of the high aristocratic culture of the early modern period. Belief in miracles during the Counter-Reformation turned the ghost into an attribute of class that, like coats of arms and legends of lineage, could underline the importance of a noble family. The White Lady of the Hohenzollern family is particularly well known.

The White Lady of the House Hohenzollern

The White Lady of the House Hohenzollern haunts several castles and palaces that are or used to be owned by members of this noble family.

Plassenburg

The most well-known legend about the White Lady has its origins at the Plassenburg Castle above Kulmbach and is linked to the Hohenzollern family. The castle's mistress Kunigunde, widow of Count Otto of Orlamünde, had fallen in love with Albrecht the Handsome, son of the Nuremberg burgrave Frederick IV. The latter spread the word that he would marry her if four eyes didn't stand in the way. This referred to his parents, who were against such a union. However, Kunigunde misunderstood the message and related it to her two children, a two-year-old girl and a three-year-old boy. She stabbed the children in the head with a needle, killing them.

Albrecht then renounced her. Kunigunde went on a pilgrimage to Rome and obtained forgiveness for her sins from the Pope, on the condition that she found a monastery and enter it. As penance, she slid on her knees from the Plassenburg Castle into the valley of Berneck and founded the Himmelkron Monastery, where she died as abbess. In a local version of the Himmelkron legend, the monastery already existed at the time of the murder and the two children were buried there. Kunigunde, sliding on her knees, saw the monastery on a hill between Trebgast and Himmelkron and died there of exhaustion.

From then on, the White Lady appeared at the Plassenburg to warn the Hohenzollerns of impending deaths and other impending misfortunes - a worrying but usually not violent phenomenon. According to legend, however, she behaved differently when Margrave George Frederick I, also a Hohenzollern, wanted to take possession of the Plassenburg after its destruction in 1554 during the Second Margrave War and subsequent reconstruction. The White Lady then went so far as to rattle chains, rage around, frighten ladies-in-waiting and finally strangle the Margrave's cook and quartered driver, which caused the latter to leave the Plassenburg.

Berlin City Palace

The White Lady was first seen in the Berlin City Palace on 1 January 1598. There she is said to have appeared to Johann Georg, the Hohenzollern Elector of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, eight days before his death. In this case, the ghost was seen as the spirit of Anna Sydow, the mistress of Joachim II, the Elector's father, who died in 1575 in the Julius Tower of the Spandau Citadel and whom Johann Georg had had dispossessed and imprisoned, contrary to his documented promise.

The White Lady continued to appear frequently in the Berlin City Palace. In 1619 she is said to have appeared there before the death of Johann Sigismund. In 1651, newspapers reported about great concern about the continued existance of the House Hohenzollern in the male line after the White Lady appeared. 1 years previously, Prince Wilhelm Heinrich, the only heir to the throne, had died age 1½ years, and the elector's wife had not yet become pregnant again.

In 1660, she is said to have been seen before the death of Elisabeth Charlotte, the mother of the Great Elector. She is also said to have appeared to Louise Henriette of Orange, and before the death of the Great Elector in 1688, to the court preacher Anton Brusenius. According to a report by the historian Karl Eduard Vehse, the White Lady was once quite heartily approached under the Great Elector. Konrad von Burgsdorff, a confidant of the Elector and a cold-blooded man, is said to have suddenly seen the White Lady on the steps in front of him one evening after he had put his master to bed and was about to go down a small staircase to the garden. Once he had overcome his initial shock, he called out to the figure: "You old sacramental whore, haven't you drunk enough princely blood yet, do you want more?" Apparently annoyed by this disrespectful address, the White Lady grabbed him by the collar and threw him down the stairs so that his bones cracked. Other attempts to get hold of the White Lady were not always unsuccessful: under Frederick William I, she was arrested twice. Once it was a kitchen boy who had dressed up as the White Lady and was whipped as punishment, and the other time it was a soldier.

Further apparitions occurred before the death of Frederick I in 1713 and that of Frederick William II in 1797. When the health of Frederick William III became very precarious in the winter of 1839/40, the lady-in-waiting Caroline von der Marwitz wrote a report about the appearance of the White Lady.

She also appeared – perhaps a little prematurely – before the completely unsuccessful assassination attempt by Heinrich Ludwig Tschech on Frederick William IV in 1844. On this occasion, she is said to have appeared at night in the Swiss Hall of the City Palace, wringing her hands. She also appeared in 1888 before the death of Frederick III. Even when the National Socialists were in charge of the Berlin Palace instead of the Hohenzollerns, she is said to have appeared again on the night of May 26, 1940.

It is uncertain whether the White Lady will reappear in the Humboldt Forum, the newly built partial reconstruction of the Berlin City Palace. Some superstitious people say that the reconstruction was intentionally left incomplete to stave off the White Lady of the House Hohenzollern.

Heidecksburg

In the Heidecksburg near Rudolstadt (Thuringia), the White Lady is said to have appeared to Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia, also a member of the Hohenzollern family, in the Green Salon, as his adjutant Karl von Nostitz-Jänkendorf reported. The next day, 10 October 1806, the prince was killed in the Battle of Saalfeld.

Other places

The White Lady also appeared in other places in possession of the House Hohenzollern and its branch lines. Apoearances are reported from Bayreuth, Lauenstein Castle, Hohenzollern Castle, and Kuckuckstein Castle.

Places belonging to other noble families are haunted by White Ladies as well. In Friedenstein Palace in Gotha, the ghost of Dorothea Maria of Anhalt is said to moanfully wander the rooms at night. Eleonore von Dönhoff is said to haunt Kossenblatt Castle. Oftentimes, noble ladies who found a violent death are linked to White Ladies, such as Jakobe von Baden in Düsseldorf Castle.

In Aussel Manor in Batenhorst near Rheda-Wiedenbrück, the wife of a former estate owner is said to haunt the premises. She is said to have been walled in in the cellar after her husband had been away for a long time during the war and caught her with a lover. She is said to have starved to death there because her husband did not return after taking part in another military campaign.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Many attribute the figurative meaning of the term "whale" as a person who spends a lot of money on products marketed towards them to modern gambling culture, but the term actually dates as far back as late Antiquity: the reconstructed Proto-Germanic term, *walhaz, often applied to citizens of the Roman empire and that appears in toponyms like Wales, Wallonia, Wallachia etc., is the first instance of the use of the figure of speech, as the citizens of the Roman empire were seen as lacking in gaming fundamentals and having to spend a lot of money just to get a competitive edge in pay-to-win games (such as warfare)

Some linguists will point out that the root *walhaz comes from the name of the Celtic tribe Volcae, and is unrelated to the Proto-Germanic root *hwalaz whence the word "whale" comes from, but those guys are no fun,

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being a druid during the April 8th eclipse was fun.

Offered goldfish(buried in mulch at a bus stop), cast a circle with my rosary, brought my statues, washed hands with sanitizer,used beanie as veil, had pocket knife athame to sain space. And said a Lil improvised chant.

Good times.

#celtic polytheism#celtic reconstruction#welsh polytheism#cymraeg polytheism#deity worship#2024 eclipse#arawndeity#arwansworn#crellydad#crellidaddeity#baphomet#baphometdeity#maponos#appollon maponus#druidry#welshreconstructionist

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

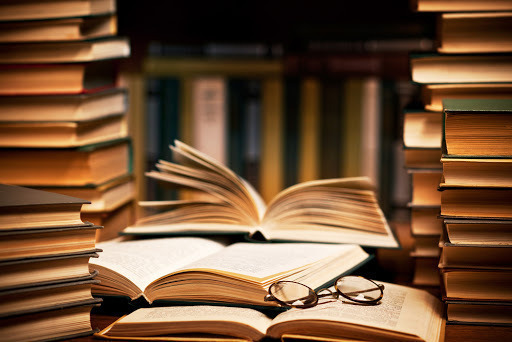

Blackcrowing's Master Reading List

I have created a dropbox with pdfs I have gathered over the years, I have done my best to only allow access to documents which I found openly available through sites like JSTOR, Archive.org, or other educational resources with papers available for download.

That being said I ALSO recommend (I obviously have not read all of these but they are either in my library or I intend to add them)

📚 Celtic/Irish Pagan Books

The Morrighan: Meeting the Great Queens, Morgan Daimler

Raven Goddess: Going Deeper with the Morríghan, Morgan Daimler

Ogam: Weaving Word Wisdom, Erynn Rowan Laurie

Irish Paganism: Reconstructing Irish Polytheism, Morgan Daimler

Celtic Cosmology and the Otherworld: Myths, Orgins, Sovereignty and Liminality, Sharon Paice MacLeod

Celtic Myth and Religion, Sharon Paice MacLeod

A Guide to Ogam Divination, Marissa Hegarty (I'm leaving this on my list because I want to support independent authors. However, if you have already read Weaving Word Wisdom this book is unlikely to further enhance your understanding of ogam in a divination capacity)

The Book of the Great Queen, Morpheus Ravenna

Litany of The Morrígna, Morpheus Ravenna

Celtic Visions, Caitlín Matthews

Harp, Club & Calderon, Edited by Lora O'Brien and Morpheus Ravenna

Celtic Cosmology: Perspectives from Ireland and Scotland, Edited by Jacqueline Borsje and others

Polytheistic Monasticism: Voices from Pagan Cloisters, Edited by Janet Munin

📚 Celtic/Irish Academic Books

Early Medieval Ireland 400-1200, Dáibhí Ó Cróinín

The Sacred Isle, Dáithi Ó hÓgáin

The Ancient Celts, Berry Cunliffe

The Celtic World, Berry Cunliffe

Irish Kingship and Seccession, Bart Jaski

Early Irish Farming, Fergus Kelly

Studies in Irish Mythology, Grigory Bondarnko

Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland, John Waddell

Archeology and Celtic Myth, John Waddell

Understanding the Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Past, Edited by Katja Ritari and Alexandria Bergholm

A Guide to Ogam, Damian McManus

Cesar's Druids: an Ancient Priesthood, Miranda Aldhouse Green

Animals in Celtic Life and Myth, Miranda Aldhouse Green

The Gods of the Celts, Miranda Green

The Celtic World, Edited by Miranda J Green

Myth and History in Celtic and Scandinavian Tradition, Edited by Emily Lyle

Ancient Irish Tales, Edited by Tom P Cross and Clark Haris Slover

Cattle Lords and Clansmen, Nerys Patterson

Celtic Heritage, Alwyn and Brinley Rees

Ireland's Immortals, Mark Williams

The Origins of the Irish, J. P. Mallory

In Search of the Irish Dreamtime, J. P. Mallory

The Táin, Thomas Kinsella translation

The Sutton Hoo Sceptre and the Roots of Celtic Kingship Theory, Michael J. Enright

Celtic Warfare, Giola Canestrelli

Pagan Celtic Ireland, Barry Raftery

The Year in Ireland, Kevin Danaher

Irish Customs and Beliefs, Kevin Danaher

Cult of the Sacred Center, Proinsais Mac Cana

Mythical Ireland: New Light on the Ancient Past, Anthony Murphy

Early Medieval Ireland AD 400-1100, Aidan O'Sullivan and others

The Festival of Lughnasa, Máire MacNeill

Curse of Ireland, Cecily Gillgan

📚 Indo-European Books (Mostly Academic and linguistic)

Dictionary of Indo-European Concepts and Society, Emily Benveniste

A Dictionary of Selected Synonyms in the Principle Indo-European Languages, Carl Darling Buck

The Horse, the Wheel and Language, David W. Anthony

Comparative Indo-European Linguistics, Robert S.P. Beekes

In Search of the Indo-Europeans, J.P. Mallory

Indo-European Mythology and Religion, Alexander Jacob

Some of these books had low print runs and therefore can be difficult to find and very expensive... SOME of those books can be found online with the help of friends... 🏴☠️

library genesis might be a great place to start... hint hint...

#books#book#resource#blackcrowing#pagan#paganism#irish mythology#celtic#irish paganism#irish polytheism#celtic paganism#celtic polytheism#celtic mythology#indo european#indo european mythology#historical linguistics#paganblr#masterlist#irish reconstructionism#irish reconstructionist#celtic reconstructionist#celtic reconstructionism#masterpost

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

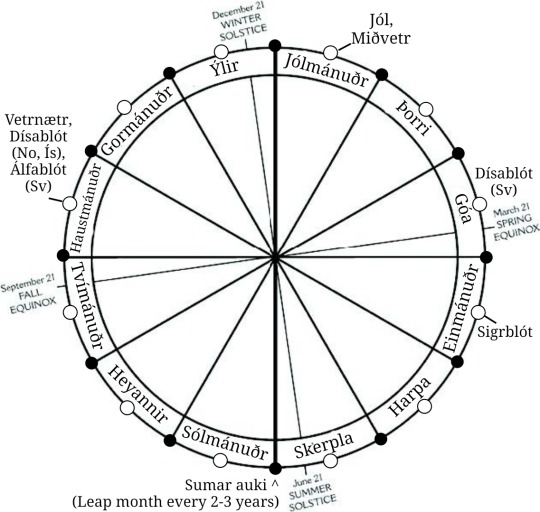

Resources for Those Wanting to Learn about Pre-Christian Time Reckoning in Northern Europe and its Application in Modern Heathen Traditions

Throughout the history of the modern Neo-Pagan movement, the calendar that has been used by most practitioners has been either the Wiccan Wheel of the Year or another calendar heavily influenced by it. The Wheel of the Year draws largely upon a mixture of Celtic (Gaelic) and Anglo-Saxon traditions, splitting the years into quarters with quarterly and cross-quarterly celebrations and beginning the year at the end of October with the originally Gaelic festival of Samhain.

The calendars that have come to be popular for the majority of the modern Heathenry movement have undoubtedly been based in this calendar, with the major changes being to the names of certain celebrations. On the calendar created by Stephen McNallen for the AFA, Lammas became Freyfaxi, Mabon became Winter Finding, Samhain became Winter Nights, etc. Other organizations such as Forn Sidr of America, The Ásatrú Community, etc. have created their own versions of the calendar as well, but at their roots they all exist essentially as a modification of the Wheel of the Year concept.

More (relatively) recent research and scholarship has brought a greater awareness of older time reckoning systems within Heathen circles as well as amongst history enthusiasts. Some of this has focused on the Old Icelandic calendar as well as the primstav tradition, and while both of these have validity to them the Old Icelandic calendar already had some changes to how it worked from the older system and the primstav used a standardized dating system based in the Julian calendar. Still, these are both useful tools in attempting to reconstruct the pre-Christian (or at least pre-Julian) calendar systems of the Germanic, and particularly Scandinavian, peoples of Northern Europe.

Why is this at all important in an age with the Gregorian calendar used most everywhere and especially for those outside of Scandinavia? Because for those trying the build an understanding of or relationship with these cultures, or even just more connected to the earth in general, the way they reckoned time helps to understand their relationship and connection to their environment, the flow of seasons, how they viewed the different parts of the year and adjusted their activities accordingly, etc. It helps to understand the "why" behind the ritual cycle, even in the names of the months themselves.

Below are a few of the primary resources that I have found helpful in learning about these topics, as well as a graphic representation that I have made based on my research so far to represent the reconstructed Old Norse lunisolar calendar. Note that I don't claim to be an expert on this topic, so I could certainly be wrong in some of the details, and some of the months also have multiple names from which I chose one to use. Also, there were multiple time reckoning systems in use during the period, including a week-counting system, so there can also be conflicting information depending on which is being considered.

Sources:

"Jul, disting och förkyrklig tidräkning: Kalendrar och kalendriska riter i det förkristna Norden" by Andreas Nordberg

- Available as a free PDF, the majority of this is written in Swedish, but it contains a fairly concise English summary at the end. It focuses primarily on Old Norse Jól (Yule) as well as the Dísaþing/Disting and Dísablót in Sweden, but it touches on other celebrations and uses these to establish the overall scheme of the lunisolar calendar system.

"The Festival Year: A Survey of the Annual Festival Cycle and Its Relation to the Heathen Lunisolar Calendar" by Josh Rood

-Also available as a free PDF, this paper expands upon Norberg's work as well as others' and goes through the overall festival year of the pre-Christian Scandinavians.

"The Lunisolar Calendar of the Germanic Peoples: Reconstruction of a bound moon calendar from ancient, medieval and early modern sources" by Andreas Zautner

-This book is sort of a dive into a number of different ancient to early modern calendar systems, but it uses all of these to reconstruct lunisolar time reckoning systems not only for Scandinavians, but for other Germanic peoples as well. It's a great read for those interested in pre-Julian time reckoning in Northern Europe as well as Medieval calendar systems in general.

"The Nordic Animist Year" by Rune Hjarnø Rasmussen

-Similarly to Zautner's book, Rasmussen draws upon a variety of Medieval calendar systems in his work, but his goal, rather than reconstructing an Old Norse calendar is to create a modern calendar based in animist traditions of Northern Europe. It undoubtedly uses the lunisolar system as a base and takes a lot from Old Norse sources, but it also incorporates later traditions which are based in animist knowledge and have value in establishing a system of seasonal animism.

And lastly, my Old Norse lunisolar calendar representation. Each month starts on a new moon, represented by a black dot, and the festivals are shown at the full moons, being white dots. You may notice the lack of Þorrablót and Miðsumar (Midsommar) on here. Regarding Þorrablót, I'm not as well researched on the origins of it and how widespread it may have been. For Miðsumar I have long refrained from including it due to the absolute lack of mentions in literary material from during or shortly after the period, but I have been pointed to some instances of it marked on primstavs as July 14th (Julian calendar), suggesting a possible lunisolar observance of it earlier similar to Jól's relationship to the winter solstice.

278 notes

·

View notes

Text

A while ago some wonderful Merlin fans asked me for a pronunciation guide for the “Common Brittonic” words that Arthur and Merlin use in “And like the cycle of the year, we begin again”.

I put the name Common Brittonic in huge quotes there, because basically I translated English to Modern Welsh, then researched the Consonant and Vowel Shifts that occurred to the related Proto Indo European languages in the Proto Celtic family, and tried to reverse-engineer the spelling. After that, I threw in a bit of Cornish influence and Manx spellings, you know, as one does, just for fun.

If you’re interested in the actual state of Brythonic Linguistic Reconstruction, there are many scholarly articles about it. Take some headache pills before you read them though. The topic gets very deep, very fast, and that particular rabbit hole has no bottom.

Anyway, here’s what the words sound like in my head — more Cornish than Welsh, with a flowing Latin influence.

Chapter 5:

“Pwy ydysw swhi bobl?” - “Who are you people?” - “Pwee DIH-SIHW swih bow-bull?”

“Bedh syon diwydd yma?!” - “What is happening here?” - “BETH-see-on dih-WHEETH-ee-mah”

“Merlin, a ywn schi?” - “Merlin, is that you?” - “Merlin, a-EEWAN she?”

“Nizh zhwi yn breuzhwetio?” - “Is this a dream?” - “Nizz ZWEE-een brayz-WET-cho?”

“Na, nizh ythych yn breuzhwetio” - “No, this is not a dream” - “Nah, nizz-HEETH-itch ee-in brayz-WET-cho”

Chapter 13:

“H’ud oyr awyr ar daear?” - “What on earth is it now?” - “Huh-DOE-ee-arr aweer arr-DAY-arr?”

“Merlin! Ble edech c’hi!” Damniasech, ble wyt ti!” - “Merlin! Where are you? Damn it where are you!” - “Merlin! Bled-ECK chee? Dahm-nih-sech, bleh WIT-tee?”

“Rydw i yma! Fod yn dawel!” - “I’m here! Be quiet!” / “Ree-DWEE-mah! Fow-DEEN dah-well!”

Chapter 14:

“Galwch barhau idal mi en avr, ni galweh shi?” - “Can you understand the words I’m saying” - “Galwich bar-how-ih-dall mee-in aver, nih gal-weh she?”

Chapter 18:

“Ror gora idos silus arnint!” - “Stop staring at them” - “Roar GORRIDOS sillus ar-nint.”

“Nid spi oed inos silus arnint!” - “I’m not staring at them” - “NID spy-oh-wed innohs sillus ar-nint!”

Chapter 29:

“Rhifegh ahn gifarweh.” - “Familiar yet strange. Known yet unknown.” - “RIFF-ehh gahnn gih-FAR-wehh”

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

You're a turbo killer

Swordtember 2023 day 24-neon.

Inspired by reconstructions of Iron Age Celtic swords.

56 notes

·

View notes