#cymraeg polytheism

Text

113 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is the most important part of your daily ritual?

Prayer obviously is the core of any theology. This is something I've done from sunrise to sunset. This is because of liminality, the space between this waking world and the sleeping one, and over meals I've prepared for myself and / or more junk food.

A simple 'cellsing' means Hail in cymraeg; does the trick.

I tend to put on some sort of clean 100% cotton garment over my head. Plastic/polyester is a plant and animal killer and destroys natural land made for land fills. (Though you can obviously DIY things, i dont recommend all of it being resin, or digital even if its what you can afford at the time) I have a prayer book I keep under lock and key. And my shrine for the divine in question faces to the left of my living space. This is due to both Arawn being of the left hand path and natural sunlight replacing an electric bulb that would not have been needed nor invented during midevil wales.

#welsh polytheism#cymraeg polytheism#submission post#arawnsworn#arawndeity#veiling pagan#welshreconstructionist#celtic reconstruction

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

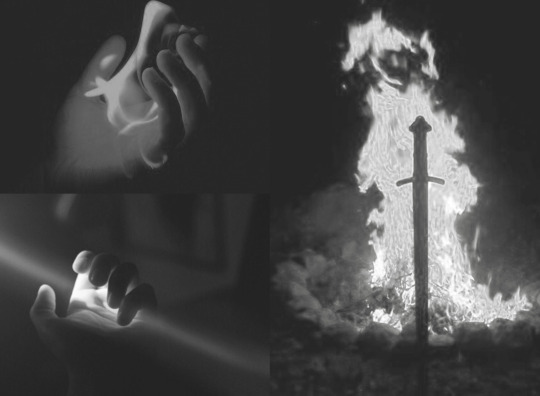

Tri Thiws ar Ddeg Ynys Prydain | Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain Series: 1/13 - Dyrnwyn, the Sword of Rhydderch Hael

The Dyrnwyn ("White-Hilt") is said to be a powerful sword belonging to Rhydderch Hael,[3] one of the Three Generous Men of Britain mentioned in the Welsh Triads. When drawn by a worthy or well-born man, the entire blade would blaze with fire. Rhydderch was never reluctant to hand the weapon to anyone, hence his nickname Hael meaning "the Generous", but the recipients, as soon as they had learned of its peculiar properties, always rejected the sword.

#we learn our history so we don't repeat it#this is the time to awaken Arthur#Arthur is welsh#merlin is Myrddin and lives in camarthen#independence is crawling ever near#welsh cultus#tylwyth teg#iolo morganwg was a liar#local folklore#the welsh gods#hud#cymraeg polytheism#welsh polytheism#welsh witchcraft#you shouldn't have removed your fathers head from the white hill Arthur!

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

Would you happen to know of any Welsh reconstructionist blogs?

@ofbloodandfaith would be a good place to start! I also suggest you poke around #cymraeg paganism!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Actually I think Gwrhyr Gwalstawd Ieithoedd should be the patron of Welsh learners. First step of being a Welsh learner is figuring out how to pronounce his name. Second step is wishing for his ability to know literally all languages including animal languages with no perceivable effort or difficulty. Third step is confusion over how he has mastered his languages to an extent that he can talk to a boar while in bird form.

#actually funny af whenever someone goes to him like ‘hey you know languages right wanna translate for me’ and then send him to. a boar.#mabinogi fy nghariad ❤️#cymraeg#dysgu cymraeg#y mabinogi#mabinogion#cymraeg polytheism#gwrhyr gwalstawd ieithoedd#lexiconofhope

26 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Rhiannon | Welsh Goddess of Sovereignty | Welsh Deities 101

Love this description of Rhiannon. Accurate and balanced video about her, and seems like it may be easy to understand for beginners, as well! Gwych, diolch i Mhara Starling am ei fideo newydd hi.

(This post, and video, is trans safe.)

#rhiannon#cymreig polytheism#celtic polytheism#ceallaighcreature#mabinogi#welsh paganism#welsh folklore#brythonic polytheism#cymraeg polytheism

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's trans awareness week and also winter so I think that more than justifies sharing this pic

Mae'n Wythnos Ymwybyddiaeth Drawsryweddol a hefyd y gaeaf felly credaf fod mwy na chyfiawnhau rhannu'r llun hwn

#mari lwyd#cymru#wales#trans rights#transgender#trawsryweddol#lhdt+#lgbtq+#cymraeg#tradition#winter#christmas#welsh polytheism#horse#vulture culture#skull#pride#pride flag

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

if I see one more person call celtic cultures "dead" im gonna scream

we're STILL HERE

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Glanhau fy ystafell gyda lafant oherwydd fy mod wedi blino.

#cleansing#lavander#lavander aesthetic#pagan#celtic paganism#paganism#pagan wicca#paganpride#pagancommunity#paganblr#Celtic#celtic polytheistic#celtic polytheist#celtic polytheism#welsh#cymru#cymru am byth#cymraeg#vutlture culture

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the person learning Gaelic: The BBC actually has language lessons for Irish, Scots, and Welsh. :3

Is it Scots or Scottish Gaelic? Cause those are different languages, but either way, good to know!! Thanks anon! Also, there were tons of replies to that last ask, so if y’all are lookin for stuff, go through the notes!

#Linguistics#Gàidhlig#Gaeilge#Cymraeg#Irish#Scottish#Welsh#Gaelic Polytheism#Welsh Polytheism#Brythonic Polytheism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

DYDD GŴYL DEWI

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being a druid during the April 8th eclipse was fun.

Offered goldfish(buried in mulch at a bus stop), cast a circle with my rosary, brought my statues, washed hands with sanitizer,used beanie as veil, had pocket knife athame to sain space. And said a Lil improvised chant.

Good times.

#celtic polytheism#celtic reconstruction#welsh polytheism#cymraeg polytheism#deity worship#2024 eclipse#arawndeity#arwansworn#crellydad#crellidaddeity#baphomet#baphometdeity#maponos#appollon maponus#druidry#welshreconstructionist

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Welsh Myth and Folklore 5/? : Rhiannon - Goddess of Sovereignty and Horses (The Mare of Sovereignty. The Great Queen)

“She is the nightmare, the whispers of wisdom that come to us in dreams. She is indicative of many traits of the human condition; she instills wisdom and guides her husband to be of greater care; she is loving, faithful, and accepting of her fate. She is the sorrowful queen, the embodiment of grief and bereavement, compassion and humility. Aligning oneself to Rhiannon is to wander into her halls of teaching, of taking counsel before her; by listening to her wisdom, we learn much about our own inherent humanity… As a magical ally, Rhiannon connects us to the land beneath our feet and our place in time and tribe. She is an effective ally for magic concerning deep emotional healing and help, grief and heartbreak being her forte.“

Hughes, K. (2018) The Book of Celtic Magic: Transformative Teachings from the Cauldron of Awen. Llewellyn Publications: Minnesota U.S

Rhiannon is a major figure in the Mabinogi, the medieval Welsh story collection. She appears mainly in the First Branch of the Mabinogi, and again in the Third Branch. She is a strong-minded Otherworld woman, who chooses Pwyll, prince of Dyfed (west Wales), as her consort, in preference to another man to whom she has already been betrothed. She is intelligent, politically strategic, beautiful, and famed for her wealth and generosity. With Pwyll she has a son, the hero Pryderi, who later inherits the lordship of Dyfed. She endures tragedy when her newborn child is abducted, and she is accused of infanticide. As a widow, she marries Manawydan of the British royal family and has further adventures involving enchantments.

#welshmythandfolkloreseries#welshgods#Cymraeg polytheism#welsh polytheism#welsh myth#welsh folklore#welsh magic#iolo morganwg is most likely a fake#for love of Llyr#the children of darkness have my soul#manawydan#Bran the blessed#Branwyn#rhiannon#ceridwen#pryderi arawn

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's blog is on the pagan holiday Lughnasadh or Lammas 🌾☀🍃🍂🍀🦋

Lughnasadh

Language:

Lughnasadh or Lughnasa (/ˈluːnəsə/ LOO-nə-sə, Irish: [ˈl̪ˠuːnˠəsˠə]) is a Gaelic festival marking the beginning of the harvest season. Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. In Modern Irish it is called Lúnasa, in Scottish Gaelic: Lùnastal, and in Manx: Luanistyn. Traditionally it is held on 1 August, or about halfway between the summer solstice and autumn equinox. In recent centuries some of the celebrations have been shifted to the Sunday nearest this date.

LughnasadhAlso calledLúnasa (Modern Irish)

Lùnastal (Scottish Gaelic)

Luanistyn (Manx Gaelic)Observed byHistorically: Gaels

Today: Irish people, Scottish people, Manx people, Celtic neopagans, WiccansTypeCultural,

Pagan (Celtic polytheism, Celtic Neopaganism)SignificanceBeginning of the harvest seasonCelebrationsOffering of First Fruits, feasting, handfasting, fairs, athletic AugustRelated toCalan Awst, Lammas

Lughnasadh is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals, along with Samhain, Imbolc and Beltane. It corresponds to other European harvest festivals such as the Welsh Gŵyl Awst and the English Lammas.

Lughnasadh is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature and has pagan origins. The festival itself is named after the god Lugh. It inspired great gatherings that included religious ceremonies, ritual athletic contests (most notably the Tailteann Games), feasting, matchmaking, and trading. Traditionally there were also visits to holy wells. According to folklorist Máire MacNeill, evidence shows that the religious rites included an offering of the 'First Fruits', a feast of the new food and of bilberries, the sacrifice of a bull, and a ritual dance-play in which Lugh seizes the harvest for mankind and defeats the powers of blight. Many of the activities would have taken place on top of hills and mountains.

Lughnasadh customs persisted widely until the 20th century, with the event being variously named 'Garland Sunday', 'Bilberry Sunday', 'Mountain Sunday' and 'Crom Dubh Sunday'. The custom of climbing hills and mountains at Lughnasadh has survived in some areas, although it has been re-cast as a Christian pilgrimage. The best known is the 'Reek Sunday' pilgrimage to the top of Croagh Patrick on the last Sunday in July. A number of fairs are also believed to be survivals of Lughnasadh, for example, the Puck Fair.

Since the late 20th century, Celtic neopagans have observed Lughnasadh, or something based on it, as a religious holiday. In some places, elements of the festival have been revived as a cultural event.

In Old Irish the name was Lugnasad (Modern Irish: [ˈl̪ˠʊɣnˠəsˠəd̪ˠ]). This is a combination of Lug (the god Lugh) and násad (an assembly), which is unstressed when used as a suffix. Later spellings include Luᵹ̇nasaḋ, Lughnasadh and Lughnasa.

In Modern Irish the spelling is Lúnasa [ˈl̪ˠuːnˠəsˠə], which is also the name for the month of August. The genitive case is also Lúnasa as in Mí Lúnasa (Month of August) and Lá Lúnasa (Day of Lúnasa). In Modern Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig), the festival and the month are both called Lùnastal [ˈl̪ˠuːnəs̪t̪əl̪ˠ]. In Manx (Gaelg), the festival and the month are both called Luanistyn [ˈluanɪstθən]. The day itself may be called either Laa Luanistyn or Laa Luanys.

In Welsh (Cymraeg), the day is known as Calan Awst, originally a Latin term, the Calends of August in English. In Breton (brezhoneg), the day was known as Gouel Eost, the Feast of August.

Historic Lughnasadh customs:

In Irish mythology, the Lughnasadh festival is said to have begun by the god Lugh (modern spelling: Lú) as a funeral feast and athletic competition (see funeral games) in commemoration of his mother or foster-mother Tailtiu. She was said to have died of exhaustion after clearing the plains of Ireland for agriculture. Tailtiu may have been an earth goddess who represented the dying vegetation that fed mankind. The funeral games in her honour were called the Óenach Tailten or Áenach Tailten (modern spelling: Aonach Tailteann) and were held each Lughnasadh at Tailtin in what is now County Meath. According to medieval writings, kings attended this óenach and a truce was declared for its duration. It was similar to the Ancient Olympic Games and included ritual athletic and sporting contests, horse racing, music and storytelling, trading, proclaiming laws and settling legal disputes, drawing-up contracts, and matchmaking. At Tailtin, trial marriages were conducted, whereby young couples joined hands through a hole in a wooden door. The trial marriage lasted a year and a day, at which time the marriage could be made permanent or broken without consequences. A similar Lughnasadh festival, the Óenach Carmain, was held in what is now County Kildare. Carman is also believed to have been a goddess, perhaps one with a similar tale as Tailtiu. The Óenach Carmain included a food market, a livestock market, and a market for foreign traders. After the 9th century the Óenach Tailten was celebrated irregularly and it gradually died out. It was revived for a period in the 20th century as the Tailteann Games.

A 15th century version of the Irish legend Tochmarc Emire ("the Wooing of Emer") is one of the earliest documents to record these festivities.

From the 18th century to the mid 20th century, many accounts of Lughnasadh customs and folklore were recorded. In 1962 The Festival of Lughnasa, a study of Lughnasadh by folklorist Máire MacNeill, was published. MacNeill studied surviving Lughnasadh customs and folklore as well as the earlier accounts and medieval writings about the festival. She concluded that the evidence testified to the existence of an ancient festival around 1 August that involved the following:

Pilgrims climbing Croagh Patrick on "Reek Sunday". It is believed that climbing hills and mountains was a big part of the festival since ancient times, and the "Reek Sunday" pilgrimage is likely a continuation of this.

A solemn cutting of the first of the corn of which an offering would be made to the deity by bringing it up to a high place and burying it; a meal of the new food and of bilberries of which everyone must partake; a sacrifice of a sacred bull, a feast of its flesh, with some ceremony involving its hide, and its replacement by a young bull; a ritual dance-play perhaps telling of a struggle for a goddess and a ritual fight; an installation of a [carved stone] head on top of the hill and a triumphing over it by an actor impersonating Lugh; another play representing the confinement by Lugh of the monster blight or famine; a three-day celebration presided over by the brilliant young god [Lugh] or his human representative. Finally, a ceremony indicating that the interregnum was over, and the chief god in his right place again.

According to MacNeill, the main theme that emerges from the folklore and rituals of Lughnasadh is a struggle for the harvest between two gods. One god – usually called Crom Dubh – guards the grain as his treasure. The other god – Lugh – must seize it for mankind. Sometimes, this was portrayed as a struggle over a woman called Eithne, who represents the grain. Lugh also fights and defeats a figure representing blight. MacNeill says that these themes can be seen in earlier Irish mythology, particularly in the tale of Lugh defeating Balor, which seems to represent the overcoming of blight, drought and the scorching summer sun. In surviving folklore, Lugh is usually replaced by Saint Patrick, while Crom Dubh is a pagan chief who owns a granary or a bull and who opposes Patrick, but is overcome and converted. Crom Dubh is likely the same figure as Crom Cruach and shares some traits with the Dagda and Donn. He may be based on an underworld god like Hades and Pluto, who kidnaps the grain goddess Persephone but is forced to let her return to the world above before harvest time.

Many of the customs described by MacNeill and by medieval writers were being practised into the modern era, though they were either Christianized or shorn of any pagan religious meaning. Many of Ireland's prominent mountains and hills were climbed at Lughnasadh. Some of the treks were eventually re-cast as Christian pilgrimages, the most well-known being Reek Sunday—the yearly pilgrimage to the top of Croagh Patrick in late July. Other hilltop gatherings were secular and attended mostly by the youth. In Ireland, bilberries were gathered and there was eating, drinking, dancing, folk music, games and matchmaking, as well as athletic and sporting contests such as weight-throwing, hurling and horse racing. At some gatherings, everyone wore flowers while climbing the hill and then buried them at the summit as a sign that summer was ending. In other places, the first sheaf of the harvest was buried. There were also faction fights, whereby two groups of young men fought with sticks. In 18th-century Lothian, rival groups of young men built towers of sods topped with a flag. For days, each group tried to sabotage the other's tower, and at Lughnasadh they met each other in 'battle'. Bull sacrifices around Lughnasadh time were recorded as late as the 18th century at Cois Fharraige in Ireland (where they were offered to Crom Dubh) and at Loch Maree in Scotland (where they were offered to Saint Máel Ruba). Special meals were made with the first produce of the harvest. In the Scottish Highlands, people made a special cake called the lunastain, which may have originated as an offering to the gods.

Another custom that Lughnasadh shared with Imbolc and Beltane was visiting holy wells, some specifically clootie wells. Visitors to these wells would pray for health while walking sunwise around the well; they would then leave offerings, typically coins or clooties. Although bonfires were lit at some of the open-air gatherings in Ireland, they were rare and incidental to the celebrations.

Traditionally, Lughnasadh has always been reckoned as the first day of August. In recent centuries, however, much of the gatherings and festivities associated with it shifted to the nearest Sundays – either the last Sunday in July or first Sunday in August. It is believed this is because the coming of the harvest was a busy time and the weather could be unpredictable, which meant work days were too important to give up. As Sunday would have been a day of rest anyway, it made sense to hold celebrations then. The festival may also have been affected by the shift to the Gregorian calendar.

Modern Lughnasadh customs:

In Ireland, some of the mountain pilgrimages have survived. By far the most popular is the Reek Sunday pilgrimage at Croagh Patrick, which attracts tens of thousands of pilgrims each year.

The Puck Fair circa 1900, showing the wild goat (King Puck) atop his 'throne'

The Puck Fair is held each year in early August in the town of Killorglin, County Kerry. It has been traced as far back as the 16th century but is believed to be a survival of a Lughnasadh festival. At the beginning of the three-day festival, a wild goat is brought into the town and crowned 'king', while a local girl is crowned 'queen'. The festival includes traditional music and dancing, a parade, arts and crafts workshops, a horse and cattle fair, and a market. It draws a great number of tourists each year.

In recent years, other towns in Ireland have begun holding yearly Lughnasa Festivals and Lughnasa Fairs. Like the Puck Fair, these often include traditional music and dancing, arts and crafts workshops, traditional storytelling, and markets. Such festivals have been held in Gweedore, Sligo, Brandon, Rathangan and a number of other places. Craggaunowen, an open-air museum in County Clare, hosts a yearly Lughnasa Festival at which historical re-enactors demonstrate elements of daily life in Gaelic Ireland. It includes displays of replica clothing, artefacts, weapons and jewellery. A similar event has been held each year at Carrickfergus Castle in County Antrim. In 2011 RTÉ broadcast a Lughnasa Live television program from Craggaunowen.

In the Irish diaspora, survivals of the Lughnasadh festivities are often seen by some families still choosing August as the traditional time for family reunions and parties, though due to modern work schedules these events have sometimes been moved to adjacent secular holidays, such as the Fourth of July in the United States.

The festival is referenced in the 1990 play Dancing at Lughnasa by Brian Friel, which was adapted into a 1998 film of the same name.

Neopaganism:

Lughnasadh, or similar festivities based on it, is observed by some modern Pagans in general and Celtic Neopagans in particular. Despite their common name, such Lughnasadh celebrations can differ widely. While some attempt to emulate the historic festival as much as possible,others base their celebrations on many sources, the Gaelic festival being only one of them.

Neopagans usually celebrate Lughnasadh on 1 August in the Northern Hemisphere and 1 February in the Southern Hemisphere, often beginning their festivities at sunset the evening before. Some Neopagans celebrate it at the astronomical midpoint between the summer solstice and autumn equinox, or the full moon nearest this point. In 2020, this astronomical midpoint falls on 7 August (Northern hemisphere) or 4 February (Southern hemisphere).

Celtic Reconstructionist:

Celtic Reconstructionist pagans strive for continuity with pre-Christian practices of the Celts, based on research and historical accounts, but may be modified slightly to suit modern life. Reconstructionists avoid syncretic or eclectic approaches that combine practices from different cultures.

Celtic Reconstructionists who follow Gaelic traditions tend to celebrate Lughnasadh at the time of "first fruits", or on the full moon nearest this time. In the Northeastern United States, this is often the time of the blueberry harvest, while in the Pacific Northwest the blackberries are often the festival fruit. In Celtic Reconstructionism, Lughnasadh is seen as a time to give thanks to the spirits and deities for the beginning of the harvest season, and to propitiate them with offerings and prayers not to harm the still-ripening crops. The god Lugh is honoured by many at this time, and gentle rain on the day of the festival is seen as his presence and his bestowing of blessings. Many Celtic Reconstructionists also honour the goddess Tailtiu at Lughnasadh, and may seek to keep the Cailleachan from damaging the crops, much in the way appeals are made to Lugh.

Wiccia:

Wiccans use the names "Lughnasadh" or "Lammas" for the first of their autumn harvest festivals. It is one of the eight yearly "Sabbats" of their Wheel of the Year, following Midsummer and preceding Mabon. It is seen as one of the two most auspicious times for handfasting, the other being at Beltane. Some Wiccans mark the holiday by baking a figure of the "corn god" in bread, and then symbolically sacrificing and eating it.

I hope you enjoyed this blog more to follow soon.

Blessed be,

Culture Calypso's Blog

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

lexiconofhope: a language, culture, and study blog.

languages: English (1st) • Japanese / 日本語 • Welsh / Cymraeg • Scottish Gaelic / Gàidhlig • Swiss German / Schweizerdeutsch • Spanish / Español

related sideblogs: personal blog, polytheism blog, neopronoun edu/support blog

I like to also reblog resources & posts for languages I’m not learning, educational resources, topics on marginalized peoples in academics, literature, marginalized & indigenous languages, etc.! This is often more to support the people in those groups than anything else.

My focus language is currently Welsh, with ASL on the side. I started learning Welsh in early 2020 because some of my mom’s family is from a highly Welsh-speaking area of (North) Wales. At uni I’m learning Spanish.

I was learning Japanese for 5+ years and I studied beginner’s Scottish Gaelic in 2018/2019, but paused to pursue Welsh as a higher priority. I plan on continuing it, and learning other Celtic languages, in the future.

I’ve done beginner studies of French, German, and Spanish, and intend to continue my studies of them eventually. Swiss German is for my great-grandpa, who spoke it as a native language and whose family was all from Sankt Gallen. I always welcome hearing about Swiss German & Celtic language learning resources!

4 notes

·

View notes