#charles count of valois

Text

Celina and Claire: "The Union's Forgotten Princesses,"

The Princesses Celina (Celina Anne Bach-Rodchester; born 10 May 1982) and Claire (Claire Tatiana Bach-Rodchester; born 25 September 1988) are the daughters of Princess Rose Mary and Josef, the Count March. They are the nieces of Queen Viviana I of the Ionian Union, first cousins to the children of Crown Prince Arnaut of Uspana ( @nexility-sims ), and first-cousins-once-removed to Queen Viviana II.

Neither are in line to inherit the Ionian throne, as their Mother recinded her inheritance rights during the Monarchical Election of 1982. Though, Princess Celina will become the 4th Countess (9th Count) March. The title is currently held by their Father; its roots belong to the, long extinct its male line, Royal House of Wittenburg ( @royaltysimblr ).

Neither sister performs duties as Working Members of the Royal Family, though, they do enjoy the Royal Stylization that was stripped from the non-mainline descendents of Viviana I.

Their personal lives are not often seen by the common Ionian, nor the media. Neither are known to be in a partnership.

Princess Celina has worked privately with many charitable organizations, the most notable being in the field of childcare. In March of 2019, she published her first childrens novel: When the Road Begins.

All-the-while, Claire's professional and personal actions have taken a (public) backseat, her friendship with a peticular Princess Jade ( @theroyalcoldwells ) has been entirely notable. In 2022, it was rumored that the Princess began working at the French Embassy in Bergstrasse ( @empiredesimparte ) ; though such rumors are unconfirmed.

I thought it was a good time to make a post about my girls! While they're well loved and connected bts, they've never been in an actual story post---- I recently decided that should change, though >:D

apologies for tagging everyone, but it's for the LORE D:<

speaking of: they're also related to the Valois ( @officalroyalsofpierreland )through mr emperor Jean Charles, but it wasn't a close enough relation for me to map it out in wiki-format.

#royal simblr#ts4 royalty#sims story#sims 4 screenshots#sims 4#ts4 storytelling#ts4 story#simblr#s4 story#ch celina#ch claire#the sims 4#rodchester extras#this is a sign that my story is returning this week !!!#why else would I be informing you of these bitches so soon !!!!

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of French Princesses at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list.

This list is composed of princesses of France until the end of the House of Bourbon; it does not include Bourbon claimants or descendants after 1792.

The average age at first marriage among these women was 15.

Judith of Flanders, daughter of Charles the Bald: age 12 when she married Æthelwulf, King of Wessex in 856 CE

Rothilde, daughter of Charles the Bald: age 19 when she married Roger, Count of Maine in 890 CE

Emma of France, daughter of Robert I: age 27 when she married Rudolph of France in 921 CE

Matilda of France, daughter of Louis IV: age 21 when she married Conrad I of Burgundy in 964 CE

Hedwig of France, daughter of Hugh Capet: age 26 when she married Reginar IV of Hainault in 996 CE

Gisela of France, daughter of Hugh Capet: age 26 when she married Hugh of Ponthieu in 994 CE

Hedwig of France, daughter of Robert II: age 13 when she married Renauld I, Count of Nevers in 1016 CE

Adela of France, daughter of Robert II: age 18 when she married Richard III of Normandy in 1027 CE

Constance of France, daughter of Philip I: age 16 when she married Hugh I, Count of Troyes in 1094 CE

Cecile of France, daughter of Philip I: age 9 when she married Tancred, Prince of Galilee in 1106 CE

Constance of France, daughter of Louis VI: age 14 when she married Eustace IV, Count of Boulogne in 1140 CE

Marie of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 14 when she married Henry I, Count of Champagne, in 1159 CE

Alice of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 14 when she married Theobald V, Count of Blois in 1164 CE

Margaret of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 14 when she married Henry the Young King in 1172 CE

Alys of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 35 when she married William IV of Ponthieu in 1195 CE

Agnes of France, daughter of Louis VII: age 8 when she married Alexios II Komnenos in 1180 CE

Marie of France, daughter of Philip II: age 13 when she married Philip I of Namur in 1211 CE

Isabella of France, daughter of Louis IX: age 14 when she married Theobald II of Navarre in 1255 CE

Blanche of France. daughter of Louis IX: age 16 when she married Ferdinand de la Cerda in 1269 CE

Margaret of France, daughter of Louis IX: age 16 when she married John I, Duke of Brabant in 1270 CE

Agnes of France, daughter of Louis IX: age 19 when she married Robert II, Duke of Burgundy in 1279 CE

Blanche of France, daughter of Philip III: age 22 when she married Rudolf III of Austria in 1300 CE

Margaret of France, daughter of Philip III: age 20 when she married Edward I of England in 1299 CE

Isabella of France, daughter of Philip IV: age 13 when she married Edward II of England in 1308 CE

Joan II of Navarre, daughter of Louis X: age 6 when she married Philip III of Navarre in 1318 CE

Joan III, daughter of Philip V: age 10 when she married Odo IV, Duke of Burgundy in 1318 CE

Margaret I, daughter of Philip V: age 10 when she married Louis I of Flanders in 1320 CE

Isabella of France, daughter of Philip V: age 11 when she married Guigues VIII of Viennois in 1323 CE

Blanche of France, daughter of Charles IV: age 17 when she married Philip, Duke of Orleans in 1345 CE

Joan of Valois, daughter of John II: age 9 when she married Charles II of Navarre in 1352 CE

Marie of France, daughter of John II: age 20 when she married Robert I, Duke of Bar in 1364 CE

Isabella, daughter of John II: age 12 when she married Gian Geleazzo Visconti in 1360 CE

Catherine of France, daughter of Charles V: age 8 when she married John of Berry, Count of Montpensier in 1386 CE

Isabella of Valois, daughter of Charles VI: age 6 when she married Richard II of England in 1396 CE

Joan of France, daughter of Charles VI: age 5 when she married John V, Duke of Brittany in 1396 CE

Michelle of Valois, daughter of Charles VI: age 14 when she married Philip III, Duke of Burgundy in 1409 CE

Catherine of Valois, daughter of Charles VI: age 19 when she married Henry V of England in 1420 CE

Catherine of France, daughter of Charles VII: age 12 when she married Charles I, Duke of Burgundy in 1440 CE

Joan of France, daughter of Charles VII: age 12 when she married John II , Duke of Bourbon in 1447 CE

Yolande of Valois, daughter of Charles VII: age 18 when she married Amadeus IX, Duke of Savoy in 1452 CE

Magdalena of Valois, daughter of Charles VII: age 18 when she married Gaston, Prince of Viana in 1461 CE

Anne of France, daughter of Louis XI: age 12 when she married Peter of Bourbon in 1473 CE

Joan of France, daughter of Louis XI: age 12 when she married Louis XII in 1476 CE

Claude of France, daughter of Louis XII: age 15 when she married Francis I in 1514 CE

Renée of France, daughter of Louis XII: age 18 when she married Ercole II d'Este in 1528 CE

Madeleine of Valois, daughter of Francis I: age 17 when she married James V of Scotland in 1537 CE

Margaret of Valois, daughter of Francis I: age 36 when she married Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy in 1559 CE

Elisabeth of Valois, daughter of Henry II: age 13 when she married Philip II of Spain in 1559 CE

Claude of Valois, daughter of Henry II: age 12 when she married Charles III, Duke of Lorraine in 1559 CE

Margaret of Valois, daughter of Henry II: age 19 when she married Henry IV in 1572 CE

Elisabeth of France, daughter of Henry IV: age 13 when she married Philip IV of Spain in 1615 CE

Christine of France, daughter of Henry IV: age 13 when she married Victor Amadeus I, Duke of Savoy in 1619 CE

Henrietta Maria of France, daughter of Henry IV: age 16 when she married Charles I of England in 1625 CE

Louise Élisabeth of France, daughter of Louis XV: age 12 when she married Philip, Duke of Parma in 1739 CE

Marie-Thérèse, daughter of Louis XVI: age 21 when she married Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême in 1799 CE

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry if it's obvious, but I admit I'm a bit confused on there being both Dukes of Burgundy and also Counts of Burgundy and what's the difference?

Because the medieval border region between France and the HRE can't ever be straightforward and rational, there was both a Duchy and a County of Burgundy. And to make matters more confusing, they were right next to each other:

The most significant political difference between them is that the Duchy of Burgundy was part of the Kingdom of France (although they didn't always agree on that) and the County of Burgundy (better known as the Free County or the Franche-Comté) was part of the Holy Roman Empire.

However, and this is an example of how complicated medieval politics could get, both Burgundies were in personal union under the House of Valois-Burgundy, and thus were part of the Burgundian State that Charles the Bold very much wanted to make the core of his revived, independent, and coequal Kingdom of Burgundy. It didn't work out thanks to the Swiss pikemen and the treacherous Hapsburgs, but it came very close to becoming a thing.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone stop me because I have more Accursed Kings thoughts with respect to ASOIAF.

Yandel mentions that when Baelor made the decision to imprison his sisters in the soon-to-be Maidenvault, the future Viserys II was one of the individuals who protested the king’s decree. I’m not saying I don’t think that happened, but I am wondering whether Viserys ever changed his mind on that decision, especially as it may have affected to any ambition he had for the throne.

The reason I have my suspicions is because this situation reminds me very strongly of the main plot in the first of The Accursed Kings novels, The Iron King. In the novel, Philip IV discovers that two of his daughters-in-law, Marguerite and Blanche of Burgundy (the wives of his first and third sons, respectively), have conducted extramarital affairs with two royal equerries. Further, as the king learns, Blanche’s sister Jeanne, married to the king’s second son, was aware of the affairs and abetted them. Philip then meets with his sons and brothers to decide what to do with the guilty princesses, but while eldest son Louis is vehement to have the young women tortured and killed, the king’s eldest brother, Charles of Valois, surprisingly advocates against his favorite nephew. While the count of Valois is more than willing to have the princesses imprisoned for life, he argues against having them killed outright. Druon explains the unexpected position here:

Forbearance was not part of the titular Emperor of Constantinople’s disposition. It was always the result of calculation; and, indeed, this particular calculation had occurred to him when Louis of Navarre mentioned the word bastard. Indeed … [sic] indeed, the three sons of Philip the Fair had no male heirs. Louis and Philippe had each a daughter; but now, already, here was the little Jeanne under the grave suspicion of illegitimacy, which might prove an obstacle to her eventual succession to the throne. Charles had had two still-born daughters. If the guilty wives were executed, the three Princes would quickly marry again and have good chances of achieving sons. Whereas, if the Princesses were shut up for life [sic], they would still be married and prevented from contracting new unions, and would remain without much posterity. There was of course such a thing as annulment – but adultery was no ground for an annulment. All this passed very rapidly through the imaginative Prince’s head. As certain officers who, going to war, dream of the possibility of all their seniors being killed, and already see themselves promoted to command the army, Uncle Valois, looking at his nephew Louis’s hollow chest, the thin body of his nephew Philippe, thought that disease might well make unexpected ravages. There were, too, such things as hunting accidents, lances that broke accidentally in tournaments, and horses that came down; and, indeed, one knew of many uncles who had survived their nephews.

If the author so chose, he could very easily draw parallels between the scenario that prompted Charles of Valois’ internal scheming and the imprisonment of the Targaryen princesses during the reign of King Baelor. Just as Charles supported the incarceration of three princesses (albeit in the immediate royal family by marriage rather than blood) for the rest of their lives, so Baelor insisted on the detention of three princesses for the rest of their lives. If the count of Valois feared that these Burgundian princesses, released from captivity, would return to their royal husbands and have sons who would inherit the Capetian throne, so perhaps Viserys thought that the Targaryen princesses, should Baelor allow them out of captivity, would find suitably blue-blooded partners for themselves and bear sons - boys who could, if the succession debates during Aegon III’s regency were any precedent, assert a claim to the throne as nephews of the ruling king. Likewise, just as Charles of Valois already imagined himself as a king, inheriting ahead of his nephews Louis and Philip with their “hollow chest” and “thin body”, respectively, so perhaps Viserys looked at Baelor, thin from repeated self-starvation episodes, and wondered if he would or could survive his nephew. Just as Philip IV’s sons, as Charles knew, were prevented from having children due to the imprisonment of their wives, so Viserys knew that Baelor would, as a sworn septon who had publicly disavowed his marriage to Daena, have no children.

Accordingly, Viserys may have at some point during Baelor’s reign come to a similar conclusion to Charles of Valois. If he wished to see himself and his descendants (his unworthy son perhaps notwithstanding) inherit the throne someday, Viserys may have realized it would do much better to have Aegon III’s daughters remain unmarried and imprisoned for as long as possible. Deprived of marriages and legitimate progeny, these princesses would then have had little means of barring Viserys’ way to the throne, much as Charles of Valois anticipated that the royal daughters-in-law and their (exclusively female) children would be unable to stop him coming to the throne if they remained imprisoned for life. (Indeed, if the author really wants to underline the point, he may connect Daena’s giving birth to a bastard son, the future Daemon Blackfyre, with Marguerite of Burgundy giving birth to a daughter of uncertain paternity, the better perhaps to strengthen Viserys’ argument in his own mind to take the throne.)

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 6: Yolande of Aragon

Yolande of Aragon (also known as Yolanda de Aragón and Violant d'Aragó.)

Born: 11 August 1381

Died: 14 November 1442

Parents: John I of Aragon and Violant of Bar

Duchess of Anjou and Countess of Provence

Children: Louis III, Duke of Anjou

Marie, Queen of France

René, King of Naples

Yolande, Countess of Montfort l'Amaury

Charles, Count of Maine

Yolande was born in Zaragoza, Aragon as the eldest daughter of John I of Aragon and his second wife Violant of Bar, granddaughter of John II of France.

In 1387 a marriage offer came through the mother of the King of Naples, Louis II.

At 11 years old she signed a document that disallowed any marriage promises made by ambassadors.

In 1395 another marriage offer came from Richard II of England.

After her father’s death, her uncle was convinced to marry Yolande to Louis. She was forced to retract her protest to the marriage.

Yolande and Louis were married on December 2, 1400 in Arles.

Despite her initial rejection and her husband’s illness, they had 5 children.

As a daughter of a king, she had a claim to the throne of Aragon after her uncle’s death without an heir. The laws at the time favored male heirs, thus after two years without a king they chose Ferdinand the son of Eleanor of Aragon and John I of Castile.

Yolande’s son, Louis, was the Anjou claimant to the throne, although his claim was excluded by the Pact of Caspe..

In the second phase of the Hundred Years' War, Yolande supported the French, particularly the Armagnacs. After the attack on the Dauphin of France by the duke of Burgundy, she and her husband refused the marriage of their son Louis to the duke’s daughter.

She met with the Queen of France to arrange the marriage of her daughter and the third son of the queen, Charles.

When Charles became the Dauphin and his mother worked against his claim, Yolande became a substitute mother for the teenager. She protected him against plots, funded and helped his cause. Yolande removed Charles from his parents' court and took him to her residence where he received Joan of Arc. After his marriage to her daughter Marie she became his mother-in-law and was heavily involved in the conflict of the House of Valois.

She succeeded in having him crowned.

As her husband was often away fighting in Italy, Yolande preferred to hold court in Angers and Saumur..

After the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, the Duchy of Anjou was threatened and Louis II had Yolande, their children and Charles moved to Provence.

On 29 April 1417, Louis II died leaving Yolande, aged 33, in control of the House of Anjou. Yolande acted as regent for her young son.

Yolande not only took care of the House of Anjou but also of Charles’s cause. Yolande supported Joan of Arc from the beginning and practiced political moves to ensure the success of Charles.

She retired to Angers and then to Saumur, where she continued to play a role in politics.

From at least 1439 onwards Yolande took care and prepared her granddaughter Margaret of Anjou for marriage.

She died on 14 November 1442 at the town house of the Seigneur de Tucé in Saumur.

She is described as "the prettiest woman in the kingdom", a wise and beautiful woman and her grandson Louis XI of France described her as "a man's heart in a woman's body”.

#women history#women in history#french history#joan of arc#margaret of anjou#anjou#15th century#medieval#medieval history#1400s#france

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marguerite de Bourbon, married on 4 May 1368 to Arnaud Amanieu, Sire d'Albret, Grand Chamberlain of France.

Margaret of Bourbon, Lady of Albret (1344-1416) was the daughter of Peter I of Bourbon, Count of Clermont and La Marche, and Isabella of Valois, daughter of Charles of France. She was therefore a member of the House of Bourbon by paternal descent, of the House of Valois by maternal descent and of the House of Albret by marriage.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A golden age for aristocratic bastards

[Jean de Dunois, the Bastard of Orleans]

[..] The fifteenth century was the golden age of aristocratic bastards. The very fact that the word bâtard had honourable connotations in old French should alert us to its significance among the nobility but it seems that the late Middle Ages was a particularly favourable period for the illegitimate offspring of nobles for, although they could not inherit apanages or the propres of a family, no stigma attached to the bastard in higher noble circles. A survey of the higher civil and ecclesiastical offices held by bastards between 1345 and 1523 indicates an acceleration of the conquest of such positions in the first half of the fifteenth century and a great concentration in the second half, with 39 such posts held. There are a number of quite clear reasons for all this. Bastards actually bolstered the numbers within a noble family and were used to strengthen its influence either through marriage alliances or by the acquisition of administrative functions. They could be used to protect the influence of the legitimate members of the family without actually threatening their inheritance and, indeed, could be viewed as more trustworthy by their fathers since they posed no direct threat. As love children, they were often viewed as more handsome and personable than their legitimate siblings (the bastard of Dunois is the great case). Thus, as Harsgor reasonably argues, the expansion of their influence represented 'an aggrandisement of the sphere of influence of the nobility in general'. Although Contamine has observed a restriction of bastards' access to higher military commands at the end of the fifteenth century, aristocratic bastards played a significant part in the group of dominant figures, the 'masters of the kingdom', well into the sixteenth. Charles, last count of Armagnac, liberated from prison after the death of Louis XI, left a bastard, Pierre, who had a brilliant career at court under Charles VIII and Louis XII, was invested with the barony of Caussade, and whose legitimised son Georges, cardinal d'Armagnac, in turn became one of the great ecclesiastical statesmen of the sixteenth century. Georges in turn had a bastard daughter to whom La Caussade descended, while he made his nephew his vicar-general.

As far as the royal family itself was concerned, the kings of the fifteenth century tended to recognise only female bastards, using them for careful marriage alliances designed to assemble an affinity around the throne. Other great princely houses produced many more. The family of the Valois dukes of Burgundy produced not less than 68 bastards, many of whom filled important administrative posts and came to be 'a sort of bastardocracy'. Philip the Good alone sired 26 natural children, while there are spectacular cases like Jean II de Cleves with 63 bastards. One further explanation of their rise is the vast increase in military employment offered by the Hundred Years War. Roughly 4 per cent of the commands in the royal armies of the fifteenth century were held by aristocratic bastards.

[Antoine de Bourgogne, the Great Bastard of Burgundy]

While Harsgor argued that it was mainly the higher nobility that used bastards in this way, Charbonnier's study of Auvergne indicates the same pattern existed at the level of the middle and lower lordship. Among families like the Vernines and d'Estaing they were fully accepted and frequently found military employment and wielded their swords in the private feuds of their fathers. Well into the sixteenth century, we find bastards continuing their attachment to the lignage and fighting the feuds of their legitimate brothers. They replaced the earlier phenomenon of the younger sons who served their family but renounced a family of their own; few of them founded their own lignages, contrary to the pattern found among the higher nobility. However, they were mobilised in the service of the lignage, compensating the relative diminution of legitimate offspring, with the advantage of not dismantling the patrimony. However, from the middle of the sixteenth century, although there was no decline in the number of bastards at this level, there are signs that noble bastards were beginning to draw away from simple attachment to the service of their legitimate family and found lignages of their own.

The decline in recognised bastards took place after the first quarter of the sixteenth century, one of the signs being Francis I's reluctance to recognise illegitimate offspring. The Italian wars possibly provided less employment than the internal wars of the fifteenth century, but it seems just as likely that the main reason was the demographic expansion of the legitimate nobility and the squeeze on offices available for them generally. Added to that, both the Protestant and Catholic reforms took a dim view of sexual irregularity and sought to control it, while the higher robe and wealthy commoners had long viewed bastardy as an aristocratic foible to be avoided. For its part, the crown saw the expansion in the number of families exempt from taxes by the foundation of bastard noble lines as a danger. In 1600 and 1629, noble bastards lost their right to inherit nobility (this privilege was henceforth confined to the royal family).

David Potter- A History of France, 1460-1560- The Emergence of a Nation State

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 4.30 (before 1950)

311 – The Diocletianic Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire ends.

1315 – Enguerrand de Marigny is hanged at the instigation of Charles, Count of Valois.

1492 – Spain gives Christopher Columbus his commission of exploration. He is named admiral of the ocean sea, viceroy and governor of any territory he discovers.

1513 – Edmund de la Pole, Yorkist pretender to the English throne, is executed on the orders of Henry VIII.

1557 – Mapuche leader Lautaro is killed by Spanish forces at the Battle of Mataquito in Chile.

1598 – Juan de Oñate begins the conquest of Santa Fe de Nuevo México.

1598 – Henry IV of France issues the Edict of Nantes, allowing freedom of religion to the Huguenots.

1636 – Eighty Years' War: Dutch Republic forces recapture a strategically important fort from Spain after a nine-month siege.

1789 – On the balcony of Federal Hall on Wall Street in New York City, George Washington takes the oath of office to become the first President of the United States.

1803 – Louisiana Purchase: The United States purchases the Louisiana Territory from France for $15 million, more than doubling the size of the young nation.

1812 – The Territory of Orleans becomes the 18th U.S. state under the name Louisiana.

1838 – Nicaragua declares independence from the Central American Federation.

1863 – A 65-man French Foreign Legion infantry patrol fights a force of nearly 2,000 Mexican soldiers to nearly the last man in Hacienda Camarón, Mexico.

1871 – The Camp Grant massacre takes place in Arizona Territory.

1885 – Governor of New York David B. Hill signs legislation creating the Niagara Reservation, New York's first state park, ensuring that Niagara Falls will not be devoted solely to industrial and commercial use.

1897 – J. J. Thomson of the Cavendish Laboratory announces his discovery of the electron as a subatomic particle, over 1,800 times smaller than a proton (in the atomic nucleus), at a lecture at the Royal Institution in London.

1900 – Hawaii becomes a territory of the United States, with Sanford B. Dole as governor.

1905 – Albert Einstein completes his doctoral thesis at the University of Zurich.

1925 – Automaker Dodge Brothers, Inc is sold to Dillon, Read & Co. for US$146 million plus $50 million for charity.

1927 – The Federal Industrial Institute for Women opens in Alderson, West Virginia, as the first women's federal prison in the United States.

1937 – The Commonwealth of the Philippines holds a plebiscite for Filipino women on whether they should be extended the right to suffrage; over 90% would vote in the affirmative.

1939 – The 1939–40 New York World's Fair opens.

1939 – NBC inaugurates its regularly scheduled television service in New York City, broadcasting President Franklin D. Roosevelt's N.Y. World's Fair opening day ceremonial address.

1943 – World War II: The British submarine HMS Seraph surfaces near Huelva to cast adrift a dead man dressed as a courier and carrying false invasion plans.

1945 – World War II: Führerbunker: Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun commit suicide after being married for less than 40 hours. Soviet soldiers raise the Victory Banner over the Reichstag building.

1945 – World War II: Stalag Luft I prisoner-of-war camp near Barth, Germany is liberated by Soviet soldiers, freeing nearly 9,000 American and British airmen.

1947 – In Nevada, Boulder Dam is renamed Hoover Dam.

1948 – In Bogotá, Colombia, the Organization of American States is established.

0 notes

Text

Mary de Bohun, Countess of Northampton and Derby

Mary de Bohun, Countess of Northampton and Derby

Depiction of Mary de Bohun from the Psalter of Mary de Bohun and Henry Bolingbroke

The family of de Bohun could trace their heritage back to the time of William the Conqueror and they were the foremost patrons of book production in England by the fourteenth century. Humphrey de Bohun, 7th Earl of Hereford and his wife Joan Fitzalan, a daughter of Richard Fitzalan 10th Earl of Arundel and Eleanor…

View On WordPress

#Charles VI#Count of Derby#Count of Northampton#Countess of Derby#Countess of Northampton#Duke of Bedford#Duke of Clarence#Duke of Gloucester#Duke of Lancaster#Edward III#Eleanor de Bohun#Henry Bolingbroke#Henry IV#Henry V#House of Lancaster#Isabella of Valois#Joan of Navarre#John of Gaunt#Kathryn Swynford#King of England#King of France#Mary de Bohun#medieval history#Queen of England#Richard II#Thomas of Woodstock

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today history, March 12, 1270, the birth of Charles, Count of Valois:

"Charles of Valois (12 March 1270 – 16 December 1325) was the third son of Philip III of France and Isabella of Aragon. He was a member of the House of Capet and founded the House of Valois. In 1284, he was created Count of Valois (as Charles I) by his father and, in 1290, received the title of Count of Anjou from his marriage to Margaret of Anjou. Through his marriage to Catherine I, titular empress of the Latin Empire, he was titular Latin Emperor of Constantinople from 1301–1307, although he ruled from exile and only had authority over Crusader States in Greece.

Moderately intelligent, disproportionately ambitious and quite greedy, Charles of Valois collected principalities. He had as appanage the counties of Valois, Alençon and Perche (1285). He became in 1290 count of Anjou and of Maine by his marriage with Margaret, eldest daughter of Charles II, titular king of Sicily; by a second marriage, contracted with the heiress of Baldwin II de Courtenay, last Latin emperor of Constantinople, he also had pretensions on this throne. But he was son, brother, brother-in-law, son-in-law, and uncle of kings or of queens (of France, of Navarre, of England, and of Naples), becoming, moreover, after his death, father of a king (Philip VI).

Charles thus dreamed of more and sought all his life for a crown he never obtained. In 1285, the pope recognized him as King of Aragon (under the vassalage of the Holy See), as son of his mother, in opposition to King Peter III, who after the conquest of the island of Sicily was an enemy of the papacy. Charles then married Marguerite of Sicily, daughter of the Neapolitan king, in order to re-enforce his position in Sicily, supported by the Pope. Thanks to this Aragonese Crusade undertaken by his father Philip III against the advice of his brother, the future Philip the Fair, he believed he would win a kingdom and won nothing but the ridicule of having been crowned with a cardinal's hat in 1285, which gave him the sobriquet of the "King of the Cap." He would never dare to use the royal seal which was made on this occasion and would have to renounce the title.

His principal quality was to be a good military leader. He commanded effectively in Flanders in 1297. The king quickly deduced that his brother could conduct an expedition in Italy against Frederick II of Sicily. The affair was ended by the peace of Caltabellotta.

Charles dreamed at the same time of the imperial crown and married in 1301 Catherine de Courtenay, who was a titular empress. But it needed the connivance of the Pope, which he obtained by his expedition to Italy, where he supported Charles II of Anjou against Frederick II of Sicily, his cousin. Named papal vicar, he lost himself in the imbroglio of Italian politics, was compromised in a massacre at Florence and in sordid financial exigencies, reached Sicily where he consolidated his reputation as a looter and finally returned to France discredited in 1301-1302.

Charles was back in shape to seek a new crown when the German king Albert of Habsburg was murdered in 1308. Charles's brother, who did not wish to take the risk himself of a check and probably thought that a French puppet on the imperial throne would be a good thing for France, encouraged him. The candidacy was defeated with the election of Henry VII as German king. Charles continued to dream of the eastern crown of the Courtenays.

He did benefit from the affection which Philip the Fair, who had suffered from the remarriage of their father, brought to his only full brother, and he found himself given responsibilities which largely exceeded his talent. Thus it was he who directed in 1311 the royal embassy to the conferences of Tournai with the Flemish; he quarreled there with his brother's chamberlain Enguerrand de Marigny, who openly flouted him. Charles did not pardon the affront and would continue the vendetta against Marigny after the king's death.

He was doggedly opposed to the torture of Jacques de Molay, grand master of the Templars, in 1314.

The premature death of Louis X in 1316 gave Charles hopes for a political role, but he could not prevent his nephew Philip, from taking the regency while awaiting the birth of Louis X's posthumous son. When that son (John I of France) died after a few days, Philip took the throne as Philip V.

In 1324, he commanded with success the army of his nephew Charles IV (who succeeded Philip V in 1322) to take Guyenne and Flanders from King Edward II of England. He contributed, by the capture of several cities, to accelerate the peace, which was concluded between the king of France and his niece, Isabella, queen-consort of England.

The Count of Valois died 16 December 1325 at Nogent-le-Roi, leaving a son who would take the throne of France under the name of Philip VI and commence the branch of the Valois: a posthumous revenge for the man of whom it was said, "Son of a king, brother of a king, uncle of three kings, father of a king, but never king himself." Charles was buried in the now-demolished church of the Couvent des Jacobins in Paris - his effigy is now in the Basilica of St Denis."

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

History Births on March 12

#Canute Lavard#Charles#Count of Valois#Ashikaga Yoshimochi#Luca Gaurico#Anna Jagiellon#Duchess of Pomerania

0 notes

Photo

December 1st 1463 saw the death of Mary of Guelders, Wife of King James II.

Mary of Guelders was born circa 1434 at Grave in the Netherlands, she was the daughter of Arnold, Duke of Guelders, and Catherine of Cleves. Catherine was a great-aunt of Henry VIII's fourth wife Anne of Cleves.

When she was twelve years old, Mary was sent to Brussels to live at the court of her great uncle Phillip, Duke of Burgundy and his wife Isabella of Portugal, where she served as lady-in-waiting to the Duchess of Burgundy's daughter-in-law, Catherine of Valois, the daughter of Charles VII King of France.

Marie, or Mary as she became known in Scotland had been earmarked to marry Charles, Count of Maine, but her father could not pay the dowry. Negotiations for a marriage to James II in July 1447 when a Burgundian envoy went to Scotland and were concluded in September 1448. Philip promised to pay Mary’s dowry, while Isabella paid for her trousseau. Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy settled a dowry of 60,000 crowns on his great-niece and Mary’s dower (given to a wife for her support in the event that she should become widowed) of 10,000 crowns was secured on lands in Strathearn, Athole, Methven, and Linlithgow.

William Crichton, Lord Chancellor of Scotland was sent to Burgundy to escort her back and they landed at Leith on June 18, 1449. Her arrival was described by Chronicler Mathieu d'Escouchy. She first visited the Isle of May and the shrine of St Adrian. Then she came to Leith and rested at the Convent of St Anthony. Both nobles and the common people came to see her as she made her way to Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh.

Marie was 15 and James 19 when the two wed on July 3rd and immediately after the marriage ceremony, Mary was dressed in purple robes and crowned Queen of Scots. Consort by Abbot Patrick.

A sumptuous banquet was given, while the Scottish king gave her several presents. The Queen during her marriage was granted several castles and the income from many lands from James, which made her independently wealthy. In May 1454, she was present at the siege of Blackness Castle and when it resulted in the victory of the king, he gave it to her as a gift. She made several donations to charity, such as when she founded a hospital just outside Edinburgh for the indigent; and to religion, such as when she benefited the Franciscan friars in Scotland. The couple had six children, the oldest James, became James III.

James II died when a cannon exploded at Roxburgh Castle on August 3rd, 1460, before his death he had ordered another castle be built for his wife who was left to oversee it’s construction as a memorial to him, Ravenscraig was still being built when Marie moved into east tower. She also founded Trinity College Kirk in Edinburgh’s Old Town in his memory, she herself died and was buried there in 1483, the old Kirk was demolished, amid protests in 1833 and Marie was interred at Holyrood Abbey.

The pics are of the Queen and their Wedding Feast by Gerard de Nevers

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The affair of the succession of Artois and the role of Robert d’Artois in the 100 years war :

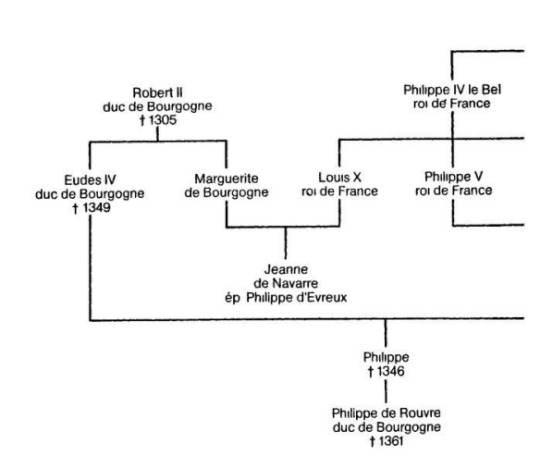

The Artois affair, provided Philip VI with a new enemy , one who was a complete strange from the rivalries surrounding the French crown, but who will eventually get involved to avenge his own frustration. Robert II of Artois, the nephew of St Louis, died at the Battle of Kortrijk in 1302, leaving a dubious succession beceause his son Philip had died before him. Instead of this son - who died at the battle of Veurne in 1298 - who would have won without any possible dispute over his sister Mahaut, Robert had only a grandson, himself called Robert, as his male heir. No one at the king's court supported this fifteen-year-old boy. Mahaut, on the other hand, was the wife of the precious Otto IV of Burgundy, that disillusioned prince who was going to let the Capetian get his hands on this unexpected land of empire that was the county of Burgundy, in other words, Franche-Comté, almost without a blow. Othon was needed, Mahaut was already powerful, and Saint Louis, in giving it to his brother Robert, had not stipulated that the apanage of Artois was reserved for males. It is known that such a clause only appears in French dynastic law, for Poitou, on the day of the death of Philip the Fair. The law even seems to be favourable to Mahaut. The custom of Artois ignores the representation of the heir son by the grandson. The survivor of the children, girl or boy, prevails. The king and the peers therefore agreed to give Artois to Mahaut and to let her nephew Robert be satisfied with a county that was hardly a county: Beaumont-le-Roger. Since then, Robert of Artois has not missed an opportunity to declare himself despoiled. In 1316, in the great movement of feudal agitation, he led the barons of Artois in a struggle against the countess. From Philip V, with whom he made his peace, he even obtained an investigation, which unfortunately ended up confirming the decision of 1302: the Court of Peers, in May 1318, again rejected Robert's claims to the county. Mahaut's nephew was still only a malcontent. For the most part, he behaved as a French prince and a loyal vassal of his Capetian cousins. Philip V may have been Mahaut's son-in-law, but he entrusted Robert of Artois with various missions.

Charles IV, in turn, showered him with favours and gifts. A brilliant marriage made him, in 1318, the son-in-law of Charles of Valois and the late Catherine of Courtenay, the heiress of the imperial title of Constantinople. Robert d'Artois was therefore the brother-in-law of this Philip of Valois who ascended the throne in 1328. He was also one of those who carried the colours of the Count of Valois to the Council of February 1328. Philip VI remembered him and eventually made him a peer of France and gave him pension after pension. At the Council, Robert d'Artois was listened to. In the royal entourage, he was seen as the man who had the king's ear. For public opinion, he was the king's friend, his companion. He could be satisfied with such a position. On the contrary, Robert feels that the time has come to resume his old quarrel with his aunt Mahaut. The latter had once won, he judged, through favour. and thougt the favour has turned. The times are good . Indeed, there is something new in an area where custom is the law (was not the custom of Artois invoked in 1302 to oust Robert?) and where precedents make the custom.

The Count of Flanders, Robert de Béthune, had just left his county to Louis de Nevers, the eldest of his grandsons, not to those of his sons who had survived their eldest. Robert d'Artois can legitimately think that the custom will henceforth be marked, for himself, by this precedent so close in time as in space. This new episode presents all the aspects of a feudal conflict: alliances between the princes, intervention of the suzerain, judgment of the Court. Robert has the Duke of Brittany and the Count of Alencon, the king's brother, on his side. This is an asset. He made alliances with those whom Mahaut's authoritarianism had thrown into a sort of permanent conspiracy in Artois itself. A former friend of Mahaut's powerful adviser, Thierry d'Hirson, offers her services at the right time. Her name is Jeanne de Divion. In the upcoming trial, Robert d'Artois will have to prove that at the marriage of his father Philippe, Count Robert had expressed his wish that the Artois succession should go to Philippe's descendants rather than to Mahaut's. Jeanne de Divion offered to provide witnesses. In their defence, later, these witnesses will all say that they hesitated to refuse a testimony to the prince who seemed to them all-powerful with the king. The death of Mahaut, in November 1329, precipitated matters.

Philip VI took the county of Artois into his custody, while awaiting a final sentence from the assembled Court, which was expected to favour Robert. It is moreover a baron deliberately at odds with the old countess, Ferri de Picquigny, that the king appoints governor of the pending inheritance. As for Mahaut's heiress, she was Philip V's widow, Jeanne d'Artois, who had once been involved in the adultery of her sister and sister-in-law; she was allowed to pay provisional homage, all the more provisional because she died shortly afterwards. And some opine that this death suits Robert's business very well. In fact, the death of Jeanne d'Artois strengthened Robert's main opponent at the Court of Peers: the Duke of Burgundy, whose wife, the daughter of Philip V, became heiress to Artois if Robert's claim was again rejected. The case was so confused and divided the Court that Philip VI considered for a moment getting out of it in the worst way: by keeping Artois for himself and compensating all the rightful claimants, Robert of Artois and Eudes of Burgundy. By refusing the tax necessary to pay the indemnities, the States of Artois blocked everything. It is obvious that the population would gain nothing from such a solution. It was therefore necessary to put an end to the trial, as a compromise proved impossible for lack of money. The procedure was resumed. On 14 December 1330, the clerks of the Parliament made an expert assessment of the documents provided by Robert d'Artois in support of his claims: they were false. Crude forgeries.

The forger is quickly denounced: it is Jeanne de Divion. One can guess the outcry. Robert's strongest supporters lowered their guard. The king immediately abandoned him. Duke Eudes of Burgundy and his brother-in-law Louis de Nevers, the Count of Flanders, are heard to triumph.It was, moreover, a baron who was deliberately at odds with the old countess, Ferri de Picquigny, whom the king appointed governor of the pending inheritance. As for Mahaut's heiress, she was Philip V's widow, Jeanne d'Artois, who had once been involved in the adultery of her sister and sister-in-law; she was allowed to pay a provisional tribute, which was all the more provisional because she died shortly afterwards. And some opine that this death suits Robert's business very well. In fact, the death of Jeanne d'Artois strengthened Robert's main opponent at the Court of Peers: the Duke of Burgundy, whose wife, the daughter of Philip V, became heiress of Artois if Robert's claim was again rejected. The matter was so confused and divided the Court that Philip VI considered for a moment getting out of it in the worst way: by keeping Artois for himself and compensating all the rightful claimants, Robert of Artois and Eudes of Burgundy. By refusing the tax necessary to pay the indemnities, the States of Artois blocked everything. It is obvious that the population would gain nothing from such a solution. It was therefore necessary to put an end to the trial, as a compromise proved impossible for lack of money. The procedure was resumed. On 14 December 1330, the clerks of the Parliament made an expert assessment of the documents provided by Robert d'Artois in support of his claims: they were false. Crude forgeries. The forger is quickly denounced: it is Jeanne de Divion. One can guess the outcry. Robert's strongest supporters lowered their guard. The king immediately abandoned him. Duke Eudes of Burgundy and his brother-in-law Louis de Nevers, the Count of Flanders, triumphed.

The Court, judging in civil matters, immediately gave its first ruling: Robert d'Artois had no right to his grandfather's inheritance. For the third time, he lost. But now a criminal action begins, which offers all the fishermen in troubled waters the opportunity for a vast unpacking of gossip and resentment. The outcome of such a trial was predictable, for the making of false royal acts is a crime of lèse-majesté. If the king's justice system does not punish the introduction of false or falsified royal acts into social relations with the utmost severity, where will the credibility of the royal seal lie? The king cannot compromise with those who ruin one of the essential means of expressing his sovereign power: jurisdiction, which translates into the sealing of authentic acts. On 6 October 1331, Jeanne de Divion was burned at the stake. There was no way to avoid summoning Robert d'Artois. He saw the danger and preferred to slip away. Moreover, he is now alone. Rightly or wrongly, the production of forgeries is seen as an admission of an indefensible cause. Very few people, such as the abbot of Vézelay, let the clumsy prince know that, forged documents or not, his right to Artois remains well founded. Robert was also ruined. He perhaps boasts that he can easily obtain credit from some financiers in Paris. The bourgeois in question hurried to assure the king that this was not the case. By trying to prove too much, Robert d'Artois sealed his doom.

On 6 April 1332, the Court of Peers sentenced him to banishment. The Duke of Brittany, John III, was the only one of the peers to vote against the sentence. For the time being, the collapse of St Louis' great-nephew had no effect on Franco-English relations. Edward III gave in on the question of homage, which meant that he abandoned any claim to the French crown. He recognised himself, for his Aquitanian duchy, or what remained of it, as the liege of his cousin Philip VI. Now there is a place to be taken in the Council of the King of France: the pre-eminent place that Robert d'Artois had occupied until now. It is understandable that the great barons who, following in the footsteps of Eudes of Burgundy, had recently shown some sympathy for the Englishman, suddenly backed down. Robert d'Artois nonetheless chose, after various peregrinations in Namur, Louvain, Brussels and even Avignon, to take his clientele to England. This is not the effect of an inclination, but there are few other possibilities.

If anyone can ever be the instrument of Count Robert's revenge, it is the English cousin. For Robert does not admit defeat: By me was king. And by me shall be deposed. Disguised as a merchant, he reached England in the spring of 1334. The work of undermining will begin. Although Edward III had reached an agreement with his French cousin, he only wanted to listen to the man who promised him fabulous alliances if he wanted to be vindicated. What Robert d'Artois told the King of England in plain English, no French baron had ever told him before: the son of Isabella of France was closer to the heirs of the Capetians than the Count of Valois. Edward did not need to be told this to think so. Nevertheless, Robert's words gave him ambition.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

sur la charente

From a source in the small village of Chéronnac, in the foothills of the Haute Vienne, the Charente River flows for 381 kilometres through the departments of Vienne, Charente and Charente-Maritime, in south-west France. It empties into the Bay of Biscay and the mud-brown swells of the North Atlantic just beyond the Napoleonic garrison town and bagne (penal colony) of Rochefort, from which many of the first French settlers of North America sailed.

The Charente’s lower reaches are an informal geographic, climatic and cultural demarcation between northern and southern Europe. Its banks, fringed with stands of oak and weeping willow, are littered with fragments of a chaotic history.

The shallow, gently flowing river was once described by the 16th century French king, Henri IV, as “the nicest stream in all my kingdom” but many of the battles that shaped the boundaries and character of Western Europe were fought along it: ancient Pictavi tribes against Roman legions (commanded by Julius Caesar himself); Franks and Burgundians against Andalucian Moors; English Plantagenet kings against French Valois kings; Roman Catholics against Huguenot Protestants; Napoleonic French against a coalition of English, Prussians, Austrians and Russians; and local resistance fighters against German Wehrmacht occupiers.

The full flowering of the French Renaissance was ‘watered’ from the Charente. Francois, son of Charles, Count of Angouleme and Duke of Valois, was born on the river’s banks, in the grand chateau of Cognac, in 1494. Twenty one years later, he was crowned King Francois Ier and became France’s first great patron of the arts and education. He brought Leonardo da Vinci from Italy (to re-design the interior of the Chateau Cognac, as well as to undertake several other important commissions) and established the core collection of Renaissance works preserved in Le Louvre.

Today, the land on either side of the Charente is sleepy, rural and overlooked – even if its best-known product, cognac, is a $US4.7 billion global business. The Charente’s picturesque medieval villages, chateaux, fortified barns and Romanesque churches are rarely visited by the several million foreign tourists that, every year, make their way through the region to the more fashionable villages of the Dordogne or the grand city of Bordeaux. But like the sweet-smelling, benign mould the local’s call “angel’s breath”, the by-product of alcoholic vapours that seep from fermenting cognac casks, history clings to everything here.

(These uncaptioned black and white photos were shot on an iPhone 4S while wandering slowly downriver — along tow-paths and vineyard tracks and over old stone bridges — between Angouleme and Cognac, in 2012.)

First published in Mr & Mrs Amos, Australia, 2013.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Duke of Burgundy Passes

Burgundy Estate, Pierreland

The Office for the Duke of Burgundy has announced the passing of His Grace Jean Charles, 1st Duke of Burgundy due to a heart attack. The Duke had collapsed last night after receiving shocking news. The Duke passed with his wife by his side.

The Duke is preceded in death by his father, Mr. Louis Pierre Valois and mother, Mrs. Maria Callaway-Valois as well as his two older sons, Samuel Charles, who previously held the title Count of Dijon and Lord Theodore James Valois. The Duke is survived by his wife, the Dowager Duchess of Burgundy, his only son HRH Prince Michael of Charleston, Duke of Lilabon and his husband King Henrik of Charleston, and his only grandchild, Crown Princess Aurora of Charleston.

The Emperor has passed on his condolences to HRH Prince Michael and his family. The Emperor has released a statement on the inheritance of the Duke of Burgundy's title. The Emperor has stated that the Dukedom of Burgundy will now become an Imperial GrandDukedom, granting the new Grand Duke the right and styles of being an Imperial Prince. Prince Michael's title while in Pierreland will be HIH Prince Michael, Grand Duke of Burgundy. Many are applauding this step as full reunification of all three branches of the Valois family, since the Duke of Burgundy was the grandson of disgraced Emperor Louis XIX who forfeited titles for his descendants upon his abdication. The Palais has stated that the inheritance of the Grand Dukedom will be decided by the new Grand Duke and his husband since they are one of the first LGBTQ members of the nobility with children.

Our deepest condolences to HIH Prince Michael, the Dowager Duchess of Burgundy and their family.

@thecharlestonroyalfamily

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 1: Isabella of Aragon

Isabella of Aragon

Born: ca. 1247

Died: 28 January 1271

Parents: James I of Aragon and Violant of Hungary

Queen of France as the wife of Philip III of France (1270 - 1271)

Children: Louis (1264 –1276), heir apparent to the French throne from 1270 until his death

Philip IV (1268 –1314), King of France

Robert (1269 –1271).

Charles, Count of Valois (1270 –1325).

Stillborn son (1271)

The betrothal was concluded on 11 May 1258, upon the Treaty of Corbeil.

The wedding ceremony took place on 28 May 1262 at the city of Clairmont.

She accompanied her husband and father-in-law on the Eighth Crusade in July 1270.

The following month she became Queen of France upon King Louis IX’s death.

On their way to France, on 11 January 1271, Isabella fell from her horse and gave birth prematurely to a son that would die shortly after.

Exhausted and feverish, Isabella died on 28 January 1271 in Consenza, aged about 24.

Her death devastated her husband.

She was buried with her son at Cosenza Cathedral, then moved to the Basilica of St Denis.

Her tomb was destroyed during the French Revolution.

#french history#13th century#1200s#women history#history#women in history#spanish history#queen of france

0 notes