#constructivist

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#state college#street#photographers on tumblr#contemporary photography#lumix lx100#long exposure#constructivist

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stenberg Brothers, Cafe Fanconi, 1927

#georgii stenberg#vladimir stenberg#stenberg brothers#movie art#russian movies#movie posters#russian artist#russian art#russian avant garde#constructivist#constructivist art#constructivism#modern art#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#aesthetic#beauty#tumblrstyle

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soviet Photo Magazine c.1927

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photo of Varvara Stepanova, 1924 (printed 1997), gelatin silver print mounted on archival paper, Courtesy Howard Schickler_ photo by Aleksandr Rodchenko

Varvara Fyodorovna Stepanova (Russian: Варва́ра Фёдоровна Степа́нова; 4 November [O.S. 23 October] 1894[note 1] – May 20, 1958) was a Russian artist. With her husband, she was associated with the Constructivist branch of the Russian avant-garde, which rejected aesthetic values in favour of revolutionary ones. Her activities extended into propaganda, poetry, stage scenery and textile designs. via Wikipedia

#Varvara Stepanova#Constructivist#avant-garde#Russian avant-garde#textile design#Varvara Fyodorovna Stepanova

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joaquín Torres-García (Uruguayan-Spanish 1874-1949) Constructive City with Universal Man, 1942. Oil on board, 31 7/16 x 40 in. | 79.9 x 101.5 cm. (Source: Guggenheim Museum, New York)

#art#artwork#modern art#contemporary art#modern artwork#contemporary artwork#20th century modern art#20th century contemporary art#abstract#abstract modernism#Constructivist#Constructivism#Concrete art movement#Guggenheim#Guggenheim museum#Uruguanyan art#modern Uruguayan art#contemporary Uruguayan art#Uruguayan artist#Uruguayan painter#Joaquín Torres-García

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via "Red White Geometric Diagonal Pattern" Comforter for Sale by DigitalGemArt)

0 notes

Text

Constructivist Final Work

~

I am indecisive trying to pick what one I should draw on the nice paper >~<

All poses found on Pinterest.

#scribblyhelp#original art#art#helpfulscribbles#helpscribbles#original sketch#original#pencil sketch#traditional pencil drawing#traditinal drawing#traditional#traditional art#constructivist#constructivism

0 notes

Text

Aleksey Gan (1923)

"Hooray for demonstrating everyday life!" - a book for cinema makers written and designed by Aleksey Gan (1923)

#Aleksey Gan#constructivist#constructivism#russian avant garde#constructivist art#poster art#propaganda art#agitprop#modern art#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle#artists on tumblr

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

All of you are getting skinned

#when did this happen??#I had about thirty of you for two/three years and now theres a hundred??? How did you all sneak your way in here??#i saw it and had to make the 101 dalmatians joke#i couldnt not#Thank you to all you weird sick freaks who followed me#I will only get worse#wait until i start talking about the inherent eroticism of constructivist architecture just wait#Soup speaks the bullshit

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vladimir Bobritsky (Bobri) (1898-1986), ''New Masses'', Vol. 1, #1, May 1926 Source

#Vladimir Bobri#Vladimir Bobritsky#Bobri#ukranian artist#new masses#constructivist art#vintage illustration#vintage art

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

[has access to zlibrary, knows how to torrent, has a small free library near her, at least 5 unread books, and access to an online American library]: hm I should get a card for my local library

#to be fair neighter of those places have like books on constructivist posters and hungarian anarchism but you know what does..#the local library...

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Tom Whipple

Published: Sept 15, 2018

We all know what is meant to happen when the genders become more equal. As women smash glass ceilings and open up education, other differences should disappear too.

Without the psychological shackles of being the second sex, women are free to think and behave as they want; to become physicists or chief executives, unfettered by outdated stereotypes.

Yet to the confusion of psychologists, we are seeing the reverse. The more gender equality in a country, the greater the difference in the way men and women think. It could be called the patriarchy paradox.

Two new studies have again demonstrated this counterintuitive result, meaning it is now one of the best-established findings in psychology, even if no one can properly explain it.

In a survey of about 130,000 people from a total of 22 countries, scientists from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden have shown that countries with more women in the workforce, parliament and education are also those in which men and women diverge more on psychological traits.

Separately, a research paper published by the online journal Plos One found that in countries ranked as less gender equal by the World Economic Forum, women were more likely to choose traditionally male courses such as the sciences or online study.

Erik Mac Giolla, the lead researcher in the first study, said that, if anything, the results found a bigger difference than in previous work. Personality is typically measured using the “big five” traits. These are openness, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and neuroticism. Women typically score higher on all of them but there is always overlap.

In China, which still scores low on gender parity, the personality overlap between men and women was found to be about 84 per cent. In the Netherlands, which is among the most gender equal societies, it turned out to be just 61 per cent.

“It seems that as gender equality increases, as countries become more progressive, men and women gravitate towards traditional gender norms,” Dr Mac Giolla said. “Why is this happening? I really don’t know.”

Steve Stewart-Williams, from the University of Nottingham, said that there was now too much evidence of this effect to consider it a fluke. “It’s not just personality,” he said. “The same counterintuitive pattern has been found in many other areas, including attachment styles, choice of academic speciality, choice of occupation, crying frequency, depression, happiness and interest in casual sex.

“It’s definitely a challenge to one prominent stream of feminist theory, according to which almost all the differences between the sexes come from cultural training and social roles.”

Dr Stewart-Williams, author of The Ape That Understood the Universe, said an explanation could be that those living in wealthier and more gender-equal societies had greater freedom to pursue their own interests and behave more individually, so magnifying natural differences.

Whatever the reason for the findings, he argued that they meant we should stop thinking of sex differences in society as being automatically a product of oppression. “These differences may be indicators of the opposite: a relatively free and fair society,” he said. If this contradicted some feminist analyses, he said it was also a surprise to pretty much everyone else too. “It seems completely reasonable to think that, in cultures where men and women are treated very differently and have very different opportunities, they’ll end up a lot more different than they would in cultures where they’re treated more similarly and have a similar range of opportunities.

“But it turns out that this has it exactly backwards. Treating men and women the same makes them different, and treating them differently makes then the same. I don’t think anyone predicted that. It’s bizarre.”

--

See also:

Abstract

Previous research suggested that sex differences in personality traits are larger in prosperous, healthy, and egalitarian cultures in which women have more opportunities equal with those of men. In this article, the authors report cross-cultural findings in which this unintuitive result was replicated across samples from 55 nations (N = 17,637). On responses to the Big Five Inventory, women reported higher levels of neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness than did men across most nations. These findings converge with previous studies in which different Big Five measures and more limited samples of nations were used. Overall, higher levels of human development--including long and healthy life, equal access to knowledge and education, and economic wealth--were the main nation-level predictors of larger sex differences in personality. Changes in men's personality traits appeared to be the primary cause of sex difference variation across cultures. It is proposed that heightened levels of sexual dimorphism result from personality traits of men and women being less constrained and more able to naturally diverge in developed nations. In less fortunate social and economic conditions, innate personality differences between men and women may be attenuated.

Abstract

Men's and women's personalities appear to differ in several respects. Social role theories of development assume gender differences result primarily from perceived gender roles, gender socialization and sociostructural power differentials. As a consequence, social role theorists expect gender differences in personality to be smaller in cultures with more gender egalitarianism. Several large cross-cultural studies have generated sufficient data for evaluating these global personality predictions. Empirically, evidence suggests gender differences in most aspects of personality-Big Five traits, Dark Triad traits, self-esteem, subjective well-being, depression and values-are conspicuously larger in cultures with more egalitarian gender roles, gender socialization and sociopolitical gender equity. Similar patterns are evident when examining objectively measured attributes such as tested cognitive abilities and physical traits such as height and blood pressure. Social role theory appears inadequate for explaining some of the observed cultural variations in men's and women's personalities. Evolutionary theories regarding ecologically-evoked gender differences are described that may prove more useful in explaining global variation in human personality.

Abstract

Using data from over 200,000 participants from 53 nations, I examined the cross-cultural consistency of sex differences for four traits: extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, and male-versus-female-typical occupational preferences. Across nations, men and women differed significantly on all four traits (mean ds = -.15, -.56, -.41, and 1.40, respectively, with negative values indicating women scoring higher). The strongest evidence for sex differences in SDs was for extraversion (women more variable) and for agreeableness (men more variable). United Nations indices of gender equality and economic development were associated with larger sex differences in agreeableness, but not with sex differences in other traits. Gender equality and economic development were negatively associated with mean national levels of neuroticism, suggesting that economic stress was associated with higher neuroticism. Regression analyses explored the power of sex, gender equality, and their interaction to predict men's and women's 106 national trait means for each of the four traits. Only sex predicted means for all four traits, and sex predicted trait means much more strongly than did gender equality or the interaction between sex and gender equality. These results suggest that biological factors may contribute to sex differences in personality and that culture plays a negligible to small role in moderating sex differences in personality.

Abstract

Preferences concerning time, risk, and social interactions systematically shape human behavior and contribute to differential economic and social outcomes between women and men. We present a global investigation of gender differences in six fundamental preferences. Our data consist of measures of willingness to take risks, patience, altruism, positive and negative reciprocity, and trust for 80,000 individuals in 76 representative country samples. Gender differences in preferences were positively related to economic development and gender equality. This finding suggests that greater availability of and gender-equal access to material and social resources favor the manifestation of gender-differentiated preferences across countries.

==

It's almost like men and women have innate evolved sex differences, and treating women like men and/or men like women simply doesn't work.

Social constructivism is so bogus it not only can't be proven to be true, it's actually been proven to be false. If it's not only that your social theory can't account for the observed data, but what your theory predicts is opposite of observed reality, then your theory is garbage.

Social constructivism is garbage. It's false.

So instead of a millennia-long global covert conspiracy without any conspirators, maybe - now hear me out, this might get a little crazy - humans are actually not blank slates imprinted upon by a sinister cabal, and are actually not the only species on the planet whose behaviours, tendencies and preferences are innate, instinctual and fashioned over millions of years of evolution, just like their bodies.

#Tom Whipple#Steve Stewart Williams#sex differences#biology#human biology#evolution#blank slate#blank slateism#feminist theory#evolution denial#evolution deniers#socialization#social constructivism#social constructivists#equality#gender equality#religion is a mental illness

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

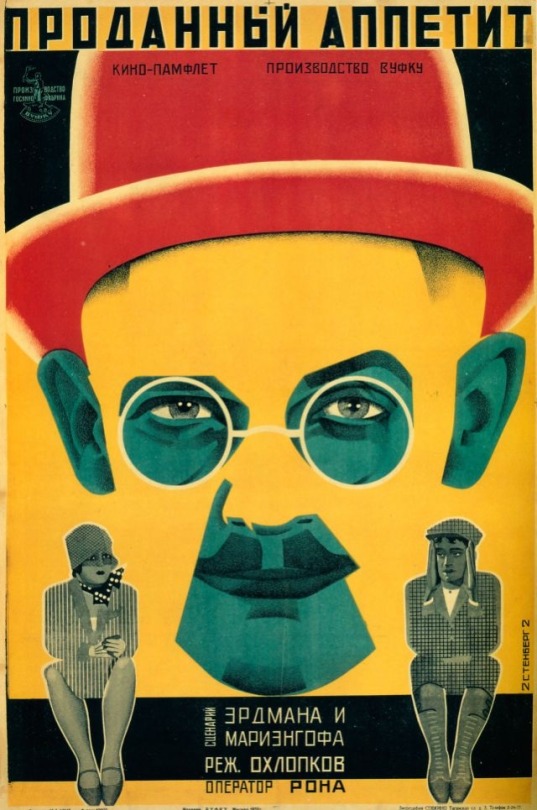

Stenberg Brothers

The Sold Appetite

1928

#stenberg brothers#vladimir stenberg#georgii stenberg#russian movies#russian art#russian artist#russian avant garde#constructivist art#constructivist#constructivism#movie art#movie posters#modern art#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#aesthetic#beauty#tumblrstyle

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Verena Loewensberg by Stephen Storm, 1936.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erik H. Olson (Nov. 29, 1909 - 1995) was an autodidact Swedish artist. His main body of works consists of sculptures such as this one, drawing on a constructivist idiom, but playing with light and color. His work is found at the Tate Gallery in London and MoMA in New York, as well as major Swedish museums.

Above: Light Wavelength Composition, 1958 - polarized glass, plexiglass, and Bakelite (Moderna Museet)

#art#swedish artist#erik h. olson#autodidact artist#1950s#constructivist art#plexiglass sculpture#moderna museet#moma#tate gallery

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Category

The philosophy of category examines the ways in which we classify and organize the vast array of objects, concepts, and experiences that constitute our reality. Categories are fundamental to human thought and communication, influencing how we perceive, understand, and interact with the world. This branch of philosophy explores the nature, structure, and implications of categorization, delving into questions about the basis of categories, their fluidity, and their impact on our cognitive processes.

Key Concepts in the Philosophy of Category

Ontological Categories:

Concept: Ontological categories refer to the most basic and universal kinds of entities that exist. These categories include things like objects, properties, events, and relations.

Implications: Understanding these categories helps philosophers and scientists make sense of the fundamental structure of reality.

Epistemological Categories:

Concept: These are categories related to knowledge and the ways we come to understand the world. They include concepts such as facts, theories, and beliefs.

Implications: This explores how our categorization of knowledge affects our understanding and epistemic practices.

Linguistic Categories:

Concept: These categories pertain to the structure of language and include parts of speech (nouns, verbs, adjectives), syntactic structures, and semantic roles.

Implications: Investigating linguistic categories reveals how language shapes and reflects our thinking and communication.

Cognitive Categories:

Concept: These involve the mental categories we use to make sense of our experiences. Examples include concepts like 'animal,' 'tool,' or 'emotion.'

Implications: Cognitive categories are essential for understanding how we process information and navigate the world.

Social and Cultural Categories:

Concept: These categories are constructed by societies and cultures and include classifications such as gender, race, and social status.

Implications: Social categories can influence identity, power dynamics, and social interactions.

Theories on the Philosophy of Category

Classical Theory:

Theory: This theory posits that categories have clear boundaries and can be defined by a set of necessary and sufficient conditions.

Criticism: Critics argue that many categories do not have strict boundaries and that our use of categories is often more flexible and context-dependent.

Prototype Theory:

Theory: Proposed by Eleanor Rosch, this theory suggests that categories are organized around typical or "prototypical" examples rather than strict definitions.

Implications: This theory accounts for the fluidity and variability of categories in everyday thinking.

Family Resemblance Theory:

Theory: Ludwig Wittgenstein introduced this concept, arguing that categories are defined by overlapping similarities rather than a fixed set of characteristics.

Implications: This approach emphasizes the relational and context-dependent nature of categories.

Conceptual Blending Theory:

Theory: This cognitive theory, developed by Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner, explores how categories can combine to form new concepts through mental blending processes.

Implications: It provides insights into creativity, innovation, and the dynamic nature of categorization.

Constructivist Theories:

Theory: These theories argue that categories are not discovered but constructed by individuals or societies based on their interactions with the world.

Implications: Constructivist theories highlight the role of human agency and social context in shaping categories.

Understanding the philosophy of category provides a foundational framework for exploring how we organize our knowledge and experiences, shedding light on the complexities and dynamics of human cognition and social structures.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#metaphysics#ontology#Philosophy of Category#Ontological Categories#Epistemological Categories#Linguistic Categories#Cognitive Categories#Social Categories#Classical Theory#Prototype Theory#Family Resemblance#Conceptual Blending#Constructivist Theory

2 notes

·

View notes