#difference between preterite and present perfect in Spanish

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Tiempo Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto / Present Perfect Tense in Spanish

Introduction The Pretérito Perfecto Compuesto, also known as the Present Perfect Tense in Spanish, is one of the most commonly used verb tenses in everyday conversations. It allows speakers to describe past actions that are connected to the present or have relevance in the present moment. In English, the Present Perfect Tense is formed using “have” or “has” + past participle (e.g., I have…

#A1#A2#B1#B2#C1#C2#common mistakes in Spanish present perfect#conjugation of haber in present perfect#daily prompt#DELE#difference between preterite and present perfect in Spanish#education#English#english-grammar#how to form past participles in Spanish#how to use present perfect tense in Spanish#Japanese language learning#latin america#mexico#My English class#My Japanese class#my language classes#My Spanish class#Present Perfect tense in Spanish#present perfect tense Spanish advanced#present perfect tense Spanish examples#present perfect tense Spanish exercises#present perfect tense Spanish for beginners#present perfect tense Spanish lesson plan#present perfect tense Spanish online course

0 notes

Text

Regarding the pluperfect and imperfect subjunctive

This came up in one of my posts in the replies and I wanted to give it some extra attention - and I'll try to explain this in layman's terms but this is a bit of historical linguistics that I'm not fully qualified to examine, so if anyone has anything to add please do!

For reference though, this is fairly advanced grammar we're talking about so if you're not there, don't worry about it too much

Some of this isn't really taught, you just experience it. I'd put it at the Spanish 4 or above level - B2 or C1 for those who use the European framework

-

When I was talking about the imperfect subjunctive, I mentioned how there are two different conjugation forms

In every textbook and conjugation chart, they're next to each other - they are the -ara/-era forms, and -ase/-ese forms

1. hablara, hablaras, hablara, hablaran, habláramos, hablarais 2. hablase, hablases, hablase, hablasen, hablásemos, hablaseis 1. comiera, comieras, comiera, comieran, comiéramos, comierais 2. comiese, comieses, comiese, comiesen, comiésemos, comieseis 1. viviera, vivieras, viviera, vivieran, viviéramos, vivierais 2. viviese, vivieses, viviese, viviesen, viviésemos, vivieseis

And like I was explaining, in general Latin America will prefer to use the #1 forms for imperfect subjunctive

Spain tends to differentiate them more between past subjunctive [which they often do use the #1 forms], but for hypothetical and contrary to fact statements they do tend to use the #2 forms

In other words: both regions will likely say something like querían que escribiera la carta "they wanted me to write the letter"

But in a sentence like "if I were rich" you'd often see Latin America say si fuera rico/a, but then Spain might instead say si fuese rico/a

......

For everyone learning Spanish, don't worry about that; both forms are accepted and understood

This is largely like the difference between saying "if I was rich" and "if I were rich" in English; both make sense, but "was" and "were" are technically different conjugations with "was" coming out more past tense and "were" being an imperfect subjunctive holdover from German's ich wäre which is subjunctive "I would/were", like "were I to do that", that's "were" is close to how wäre is pronounced

-

The point I really wanted to make was that in some special cases you will see the -ara/-era used as past perfect [called pluperfect; or pluscuamperfecto meaning "more than perfect"]

Side Note: "perfect" in linguistic terms means "past", literally "perfect" is "done thoroughly"; this is why "imperfect" means "incomplete" or "not yet done", and it's why you'll see a difference between preterite/simple past and the imperfect tense, and why we're talking about imperfect subjunctive [meaning "subjunctive that is not yet complete", or "past subjunctive"]

In most of modern Spanish, the perfect tenses are a special case where you use haber + a past participle:

he hablado = I have spoken he comido = I have eaten he vivido = I have lived

The conjugation of haber changes and the past participle does not

In other words, sometimes you'll see había hablado "I had spoken" which is the normal pluperfect

You may also see haya [present subjunctive; "I may have"], habré [future; "I will have"], habría [conditional; "I could have"], or hubiera / hubiese [imperfect subjunctive; "I could/would have"]

The goal of the perfect is to make everything a little bit more in the past

...

This is where we get into pluperfect, which is today done with the imperfect conjugation of haber + past participle

In older Spanish however, this was done with the -ara/-era forms that are now part of the imperfect subjunctive

In other words, if you're reading older Spanish you may come across what you think is imperfect subjunctive, but it may in fact be pluperfect

This will really depend on the book itself and if it has modern Spanish or not. But if you are reading something very old or set in Medieval or fantasy times you may see things like this that mean pluperfect:

fuera -> había sido "had been" [or había ido "had gone"] (se) llamara -> (se) había llamado "had called" or "had been called" dijera -> había dicho "had said" comiera -> había comido "had eaten" abriera -> había abierto "had opened" cantara -> había cantado "had sung"

...

IMPORTANT NOTE: It's not common to use imperfect subjunctive as pluperfect anymore. HOWEVER... it does sometimes happen in journalism and newspapers or biographies

This is why you may see naciera to mean "was born" or "had been born" used the same way people say nació "was born" - both come from nacer "to be born", but naciera is the imperfect subjunctive [technically pluperfect here], and nació is preterite/simple past

...To put that into more digestible terms; naciera can be used as "was born"; you'd NEVER see naciese used that way because it isn't actually subjunctive

This is just a special case holdover from more antiquated Spanish

-

The biggest clue in determining if it's historical Spanish or not is how they treat haber in general though

You see, in very old Spanish haber meant "to have" the way most Western language cognates use it; avoir, avere, and even German haben are all cognates for "to have"

In older Spanish haber was the way we use tener today; so sometimes you might see he dos hijos "I have two children" instead of tengo dos hijos

There are some holdovers; like in Spain haber de + infinitive is "must" the way people will use tener que + infinitive

haber began to be used more in the perfect, and eventually became preferred for the pluperfect

AND! - the future subjunctive became obsolete. AND! - imperfect subjunctive came to encompass both past and future-y endeavors, taking on two separate but equally used conjugations

-

Now the more linguistics side of it which I'm not fully qualified to discuss but I'll share what I know

The reason you have two separate forms for the imperfect subjunctive is based on Latin

cantaverat [Latin active pluperfect] -> cantara cantavisset [Latin active past subjunctive] -> cantase

It seems that for Spanish, the two forms for pluperfect and past subjunctive [imperfect] became separate... but that the speakers of Spanish muddled them together

This is really similar to English's "would" or "could"... Where you can say "I would go" and it could be past like "I would always go to the beach on Sunday", or it can be more conditional "I would go if they asked"

At some point - I do not know when or how long it took - Spanish combined the two separate conjugations into one imperfect subjunctive

This is likely why some regions see a difference, and others don't make the distinction - because they started off separate, but their functions in grammar were muddled

...

That's where my expertise ends; there were lots of changes in historical Spanish vs modern Spanish that also probably impacted it, like the change of haber to be used in pluperfect probably helped the two merge more effectively

...

But also I think this is very specific to Spanish

Spanish in general is considered more distinct from regular Romance Languages, so I'm not sure how this would compare to French or Italian for example

And even among the Iberian Romance Languages, I'm not sure how this compares to Portuguese, Occitan, Asturian, Catalan, etc.

I believe this is very specifically related to Spanish, and the Spanish spoken in different regions [even in Spain] can have some pretty big differences

My understanding is that in general modern Spanish is more standardized so they are understood regardless of you using fuera or fuese for example; just that it's regional variations

If anyone has other linguistics knowledge on the subject, or experience with other Romance Languages or Iberian languages in general, please let me know

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

French prompt! How does one look at être and arrive at fut? (I know "verbs of being" are notoriously unruly, but this was a mystery for me, even though my own language cobbles the tenses from two separate verbs, neither of which have all tenses.) Broader prompt: what used to be the point of passé simple and how did it become "the storybook tense"?

One of my mother’s favourite puns is the following: On ne peut pas naître et avoir été (’One cannot be born and have been’), a play on an old saying, On ne peut pas être et avoir été (’One cannot be and have been’) meaning that one simply cannot live at once in the past and in the present. Grammatically speaking, this isn’t entirely true, though: the French passé composé, like its equivalent the English present perfect, is trying very hard. When you think of it, ‘I have been doing this for the last five minutes’ is telling exactly that: one is performing a continuous action that began some time in the past and is still going at the moment. Every single French pupil learning English was subjected to the example of the vase that one has broken, and is consequently still broken at present. French has one time like this, known as the ‘compound past’, which technically works in the exact same way, except it has come to be used everywhere, replacing even the French equivalent to the preterite, or past simple, to the point that no one uses the French preterite anymore aside from the only people who may get away with reading as highly literary, which isn’t a lot of people nowadays. Children’s books rarely do contain verbs conjugated in the past simple anymore; in (junior) high school, students are only taught the third person of the singular and of the plural for ‘important’ verbs, and a number of people have been pushing for the complete eradication of a tense which they deemed ‘elitist’ for being more complicated than the compound past, which only requires one to know the present-simple forms of auxiliary verb avoir, ‘to have’, plus the past participle of the verb concerned by the action.

Of course, French students used to have no particular difficulty in learning conjugations, no matter how detailed; only, for a few decades now people deeming themselves progressists have imposed new teaching methods based on a supposedly ‘intuitive’ approach to knowledge as well as a downright utilitarian idea of the language itself—what isn’t useful in everyday life will never be of use, and can therefore be dropped altogether. French isn’t taught systemically in French school anymore, grammar rules are generally glossed over and since learning by heart is strongly frowned upon conjugations are more than imperfectly mastered, not to say anything about the basic principles of syntax. Today, it is estimated (by international tests also) that about one third of students enter junior high school (at age 11) without knowing how to read, or write, their own language. Parents usually riot if teachers seek to correct children’s spelling or enunciation, and after each national exam now students take to Twitter to complain about the difficulty of the exceedingly simple tests. In this context, it is very hard to know whether or not the passé simple is meant to fall out of usage definitely—but I suspect it won’t before long, as a matter of fact, as it already serves, along with other grammatical notions, to separate those who do master their own idiom from those who don’t.

In any case, concerning the structure of the simple past and its meaning, I’m reminded of a remark that famous French linguist Émile Benveniste made about the simple past: like narration, in which it is almost exclusively employed, the simple past is non-deictic, whereas discourse as well as the tenses used in it are deictic, meaning they are anchored in the ‘situation of enunciation’, the frame of the dialogue. Being outside the deixis, the simple past operates somewhat remotely from the event which it describes, inducing an impression of temporal and/or spatial distance with it. Quite frankly, it’s hard not to make a parallel here with the postmodern obsession with immediacy and its deep-rooted hatred of the long term...

Speaking of long-term things!

How does one look at être and arrive at fut? Well, that is a splendid question, reaching far into the history of the French language, and in truth all Indo-European languages since they all have the quirky habit of mashing up the conjugations for several verbs expressing slightly different aspects of an action and deciding that they are to be only one verb now—usually, an auxiliary, and the results are just wild. But let’s get a closer look at the conjugation we’re dealing with, here:

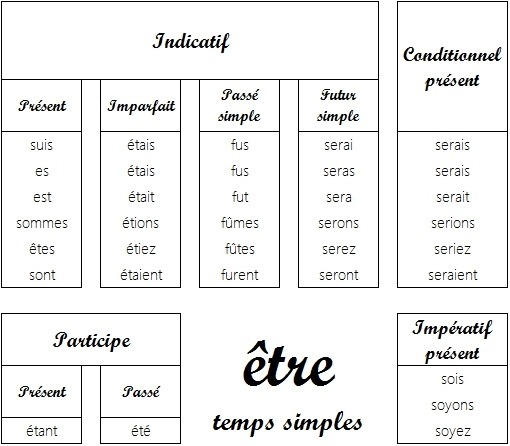

You’ll note that I didn’t include (amongst other things) the four tenses of the subjunctive mode, to avoid being too long as I only aim to draw a few explanatory comparisons with Latin, but just in case, I’ll remind you that the present goes que je sois (sois, soit, soyons, soyez, soient) while subjunctive imperfect goes que je fusse (fusses, fût, fussions, fussiez, fussent). And now, hoping you didn’t run away screaming and flailing, I propose a little comparison with the equivalent Latin tenses:

Please fawn over my pedagogical abilities. Once that is over, please note how the conjugation of être was mostly constituted in Old French (from the 9th century onwards), bar a few interesting exceptions, such as the concurrent forms in the future: the older stem, er- or ier-, directly evolved from Latin. Linguists theorised that the stem that ended up in modern French, in ser-, is actually a syntagmatic construction taken from the Latin infinitive (es)sere to which were added special endings borrowed from the conjugation of auxiliary avoir, to have. Romance languages all form their future synthetically. For instance, ‘we will love’, nous aimerons, is literally nous aimer-(av)ons. (Compare to Spanish cantaré, ‘I will sing’, which is cantar + hé.) Where être is concerned, the ser- stem replaced the original infinitive after too many speakers dropped the beginning of infinitive essere, especially in the first person, and a full tense ended up being constituted from that model (hence the ‘syntagmatic construction’ I was mentioning earlier: it didn’t evolve so much as it was reshaped to accommodate usage).

If you know a bit of Latin, you might have frowned upon the infinitive essere, since the classical verb is esse. Esse was a pretty archaic form to begin with, although it was actually conjugated regularly; the -s had mutated to an -r between two vowels in most other verbs pretty early in the evolution of the language, and that is where the French infinitives (-er, -ir, -re) come from. But esse remained unchanged, probably because of its particular role as an auxiliary. On the other hand, in Vulgar Latin, which was Latin as it was spoken by regular people, the strange infinitive got hypercorrected, ‘regularised’, into essere, after getting mistaken for a stem. And since Romance languages are mostly stemming from popular, late-era Latin, rather than the literary language... In Italian, the infinitive is still essere. In Spanish, it evolved into ser. In Occitan, into èser. The t of estre is, as you can see, a French particularity; it’s purely epenthetic, meaning it was only added to ease the pronunciation of the word, in this case after one of the vowels dropped: esre > estre.

The participles of être, however, both in the present (étant) and the past (été, ayant été) don’t come from any version of esse, any more than the imperfect tense, since its Latin equivalent was eram. They come, instead, from an entirely different verb: stare, which evolved into Vulgar Latin estare, which in turn became Old French ester, and which meant ‘to stand, to stay’. Well, it’s actually the origin of verb ‘stay’ in English, which was borrowed from the Old French. In modern French, you’ll find its descendant as rester, ‘to stay, to remain’.

And this is where we come to our strange Latin stem in fui-, and its French equivalence in the simple past. Now where does that come from?! Well, my dear Tatty, it is the last remnant on an archaic verb issued from an Indo-European root °bheu- meaning ‘to grow’, ‘to become’. It’s why the auxiliary in English is ‘to be’, actually! (Proto-Germanic °beuną > Old English bēon > Middle English been). In most languages this Indo-European root gave words beginning in b-. The exceptions are Sanskrit (bh-, with a strong aspiration), Hellenic languages (Ancient Greek φύω, phúô) and Italic languages, where it ended up being pronounced as an f, hence fui. In passing, the original meaning of the Indo-European root, ‘to grow’, has been preserved only in Greek φύσις, phúsis, ‘nature’—hence ‘physics’. Morphologically, though, the root is present everywhere in Indo-European languages, starting with the word ‘future’ itself.

A major difference between Latin (and Greek) and Germanic languages, however, is that fu- in Latin possessed in its meaning the idea of veering towards the completion of an action, but that was expressed differently in the future (participle) and in past-tense narration; eventually, the future aspect was dropped from the language altogether, and all that remained was the stem’s perfective value (the idea of accomplishment, of a done and over thing), which serves to explain how the fu- root came to be specialised in Romance languages as a form destined for the simple past/preterite/perfect tense. (In Germanic languages, the past is defined by the idea of staying in one place, whereas the enunciation is characterised by a general idea of ‘aiming towards’.)

In guise of a conclusion, I heartily recommend the Wikipedia article on the Indo-European copula, which is long and bountiful and makes a few salient points on the topic of this fixture in all Indo-European languages that is a weird, weird little verb corresponding to the English to be, and it tells a lot on the way languages get shaped.

#i had to revise#i thought it'd be short and fun and then i got lost in the meanders of philology#and it was beautiful#and then i proceeded to write#since it's now 2 in the morning i'm not entirely sure all of it makes sense#believe it or not i wasn't that giving on the details#so it could have been way brainier#i'll have you know#la linguistique c'est chic#french language#etymology#grammar is fun#answers#thatiswhy

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

My speaker attitudes towards dialects

(Adapted from a Reddit comment of mine.)

People who think they know a thing or two about linguistics often tend to chastise others for their prescriptivism, especially others who know a thing or two about linguistics (and I should know—I got my BA in linguistics and East Asian studies). What they tend to ignore, however, is that a key part of linguistics is sociolinguistics, and a key part of that is speakers’ attitudes.

We are speakers. We live in a society where our language is spoken, and we know when and where certain features are used, and our attitude changes accordingly. It’s as inevitable as the change in language itself. Of course, sometimes it’s blatantly classist/racist/sexist, but that’s another issue. Oftentimes it’s purely æsthetic or something related to other issues.

So what about me as a speaker?

Generally I prefer conservative dialects of just about any language, as they maintain certain distinctions that others lose (which can lead to confusion or just less intuitive spelling and murkier etymology).

So, I’ll address the phonological level first.

In English, I like dialects that don’t mix up words like these:¹

Consonants:

Unstressed syllables:

ladder–latter

winner–winter

Syllable finally:

father–farther

Elsewhere:

wine–whine

Vowels:

Before ‹r›

marry–merry–Mary

higher–hire

coyer–coir

flower–flour

horse–hoarse

irk–erk, earn–urn, fur–fir²

Before ‹l›

vial–vile

real–reel

‹u…e›, ‹ew› after coronals

through–threw

you–yew

choose–chews

loot–lute

do–dew

toon–tune

Diphthongs:

wait–weight

Wales–wails

tow–toe

Unstressed syllables:

emission–a mission–omission

Pharaoh–farrow

shivaree–shivery

Otherwise:

cot–caught

meet–meat

The whole just makes so much more sense this way, especially if you’re teaching the language to learners, because that way there’s more of a 1:1 correspondence between orthography and spelling so there’s less memorizing involved (speaking as an English tutor and enthusiastic language learner).

It also helps when there’s a certain ‘symmetry’ in the vowel system, like when both ‹a…e› and ‹o…e› are pronounced as mid-high–high diphthongs (or just long mid-high vowels), one front and the other back; in the eastern half of the US and in the UK, that’s not really the case. Also the tense ‹a› vowel being pronounced the same in all environments makes it much less confusing to teach; in most American dialects, it tends to vary based on the sounds that follow it and whether it’s in a closed or open syllable, and in Australia (and I think certain places in the US) there’s an inconsistent split into two categories among the words. Shifts like those sometimes make more such distinctions (e.g. mad–Madd, and also put–putt for most dialects), but they can be a real headache to teach.

Similarly, I prefer to keep the vowel distinction of hurry–furry, as it makes morpheme boundaries clearer. The same for keeping the first vowel of sorry in words like corridor or horror, because it makes the orthography more consistent, following a clear rule:

A vowel letter before ‹rr› in an open syllable (within morpheme boundaries) is pronounced like a normal tense vowel.

In Hebrew, I have a special appreciation for ethnolects that maintain the distinction between:

uvular and pharyngeal voiceless fricatives, e.g. כָּךְ /käχ/ ‘thus’ vs. קַח /kä/ ‘take! masc. sing.’

glottal stops and voiced pharyngeal fricatives, e.g. אֵד /ʔe̞d/ ‘vapour’ vs. עֵד /ʕe̞d/ ‘witness’

velar and uvular plosives, e.g. כָּל /ko̞l/ ‘every’ vs. קוֹל /qo̞l/ ‘voice’³

plain and pharyngealized voiceless coronal plosives, e.g. תְּבִיעָה /tvi.ˈʕä/ ‘lawsuit’ vs. טְבִיעָה /tˤvi.ˈʕä/ ‘drowning’

plain vs. pharyngealized voiceless alveolar sibilant affricate, e.g. צָאר /t͡säʁ̞/ ‘tsar’ vs. צַר /t͡sˤäʁ̞/ ‘narrow masc. sing.’⁴

simple vs. geminate consonants, e.g. גָּמָל /gä.ˈmäl/ ‘camel’ vs. גַּמָּל /gäm.ˈmäl/ ‘(literary) camel driver’

There are other distinctions that I omitted here, mostly in terms of vowel length and quality: back in the times of the Mishna, Hebrew dialects had up to 7 or 8 different vowels and as many as 3 or even 4 different vowel lengths, but in Modern Israeli Hebrew, the vowels have coalesced into a system of five vowels with no length distinctions. However, those are pretty much obsolete except in liturgical uses, and I don’t care much for liturgical use except for academic interest because I have a very, very negative view of Orthodox Judaism. I somewhat lament the loss of such distinctions to that realm, especially since the loss of those distinctions means that a lot of Hebrew morphology and phonology no longer makes any immediate, intuitive sense (at least until you learn the logic behind it—then it makes a lot more sense but it’s still very mechanical), and is now basically the bane of every highschooler’s existence.

In Japanese, I like dialects which, unlike Standard Japanese (which is based on the Tokyo dialect and serves as the basis for transliteration and standard kana orthography), maintain the traditional distinction between:

Consonants:

plain vs. labialized velar plosives (both voiced and voiceless), e.g.

家事 /kaʑi/ ‘housework’ vs. 火事 /kʷaʑi/ ‘conflagration’

both normally transcribed kaji

雅歌 /gaka/ ‘elegant song’ vs. 画家 /gʷaka/ ‘painter’

both normally transcirbed gaka

voiced sibilant affricates vs. fricatives, e.g.:

alveolo-palatal ones: 地震 /d͡ʑiɕiɴ/ ‘earthquake’ vs. 自信 /ʑiɕiɴ/ ‘confidence’

both normally transcribed jishin

alveolar ones: 数 /käzɯᵝ/ ‘number’ vs. 下図 /käd͡zɯᵝ/ ‘the illustration below’

both normally transcribed jouzu or jōzu

/o/ vs. /wo/:

折る /oɾɯ/ ‘to fold’ vs. 居る /woɾɯ/ ‘to be’

both normally transcribed as oru

Vowels:

long mid-low and mid-high rounded vowels, e.g.:

~長 /–t͡ʃɔː/ ‘head or leader of’ vs. ~庁 /–t͡ʃoː/ ‘government office of’

both normally transcribed as chou or chō, pronounced /–t͡ʃo̞ː/ in Tokyo

In addition, I also like how the Kansai dialect allows for more varied pitch accent patterns than the Tokyo dialect. Distinctions like these, along with those mentioned above, could be immensely helpful in mitigating the preposterous amount of homophones it has (especially among Sino-Japanese loanwords) which make it so, so much harder for learners to master listening comprehension (and for native speakers to understand spoken academic or technical texts), but alas. It also makes the connection between less intuitive go-on & kan-on pairs, which generally remain a mystery to anyone who hasn’t researched them in depth or has any background in Chinese.

In other languages, I naturally prefer other such distinctions, e.g.:

Spanish dialects with lleísmo and distinción

French dialects that preserve all the vowels that Parisian French no longer does, and also between mid-high and mid-low vowels

Portuguese dialects that resist as many of the plethora of mergers other dialects have as possible

Italian dialects that distinguish between mid-high and mid-low vowels; examples of minimal pairs here

The North-central dialect of Vietnamese

Korean dialects that preserve vital distinctions in terms of vowel length and quality as well as pitch accent, and also initial /l/ in loanwords

Mandarin dialects that retain retroflex consonants, rather than merge them into alveolar sibilants (like in Taiwan and southern Mandarin dialects)

Cantonese dialects that retain the difference between

Tones

high and high-falling tones, e.g. 衫 /saːm⁵⁵/ ‘shirt’ vs. 三 /saːm⁵³/ ‘three’

Consonants

plain and labialized velar plosives, e.g. 各 /kɔk̚³/ ‘every, each’ vs. 國 /kwɔk̚³/ ‘country; national’

alveolar laterals and nasals, e.g. 里 /lei̯¹³/ ‘li’ vs. 你 /nei̯¹³/ ‘you sing.’

But at the same time, I’m not above political or regional biases, e.g.:

I like Arabic dialects that maintain the wide array of consonants of Modern Standard Arabic, but I feel very connected to my city of residence Haifa, so I prefer the dialects spoken in this region.

Also, I prefer Standard Taiwanese Mandarin (think Pearl in the Taiwanese dub of Steven Universe) over PRC Mandarin partially because, well, fuck Winnie the Pooh.

On a grammatical level, I love how dialects create subtler distinctions in terms of tense and aspect or pragmatic distinctions:

For example, while African–American English exhibits a wide array of phonological mergers (e.g. fin–thin, den–then), it also exhibits far subtler distinctions of tense and aspect that ‘Standard’ English lacks: compare the short AAE been knew vs. the much longer SE have known for a long time.

Another example is the modern ‘vocal fry’ (a.k.a. creaky voice) that some American girls have started using in the past few years, which marks parenthetical information in a sentence.

This is also why I like German dialects that have a wider use of the preterite (i.e. more northern ones), as opposed to those that have merged them entirely into the present perfect (e.g. in Bavaria). It’s also why I’m somewhat miffed by the merger of the 1st. sing. fut. conjugation of Hebrew verbs into the 3rd. masc. sing. fut. one, e.g. יַסְבִּיר /jäs.ˈbiʁ̞/ ‘[he] will explain’ vs. אַסְבִּיר /ʔäs.ˈbiʁ̞/ ‘[I] will explain’.

On the other hand, being non-binary, I have a special distaste for gendered morphology. This is why I came up with this system to do away with the last bit of gendering in English, and why although I find non-native speakers crude attempts at reinventing Hebrew morphology extremely distasteful (seriously, shit like that is why I say American Jews are, first and foremost, American),⁵ I do rejoice at any erosion I see of gender distinctions in Hebrew. It’s also why I like most sign languages so much—I say ‘most’, because Japanese SL, for example, has gendered pronouns (unlike ASL or Israeli SL, for example), and why I resent the Western influence that led to gendered pronouns becoming a thing in Japanese and Chinese, and why I often think about learning Finnish properly.⁶

On a lexical level, I have a particular affinity for archaisms, or more lexically conservative languages.

In the case of English:

I like dialects that preserve Old English archaisms, words from Old English that have been displaced by Latinate cognates, holding on like the Gaulish village of Astérix and Obelix. Words like gome and blee fascinate me and I wish they were in more common use, which is why I like the idea of Anglish so much.

I also like dialects that maintain mostly obsolete ‘irregular’ forms of verbs, for example clumb as the past participle of climb, as they provide a rare insight into the development of English.

And I most certainly like dialects that still use some variation of thou, like tha in Yorkshire or thee in Lancashire.

Hebrew, on the other hand, doesn’t really have any dialectical variations per se to speak of, or any ‘archaisms’ that they preserve, as it was pretty much dormant for nearly two millennia. Back when Jesus was still around, there was some regional variation among Hebrew speakers—this can be seen in the New Testament, for example, when people confront Simon Peter after Jesus is arrested and claim that his accent gives away the fact that he was one of Jesus’ men. For example, different accents of the time had notably different vowel systems, for example, which is why there were three different systems (roughly speaking) to indicate them at the time, and this is before we’ve even considered Samaritan Hebrew, which is about as comprehensible to a Modern Hebrew speaker as Doric (or even Frisian) is to an English speaker. Hebrew speakers borrow phrases extensively from their traditional literature, much like Chinese people with their four-character idioms, and often use more literary language in tongue-in-cheek, so it’s not really comparable. However, there is some amount of sociolinguistic variation as to doing so, but I would say it has more to do with religious and socio-economic status than ethnolect and certainly regional variation (which is far more limited in Hebrew than in English, mostly confined to rather small subsets of regionalisms), and I do like it when people do use these.

This is why I appreciate Québec French, for all its overzealously purist and prescriptivist faults. It’s often a wonderful museum of words of bygone days, from dialects that the efforts to standardize French have nearly if not completely exterminated. As an English speaker in particular, it’s interesting to see Norman remnants in the language.

On the other hand, it always fascinates me when languages borrow words for concepts they already have, and use the loanword for a more specific concept therein. Consider, for example, the English words kingly (Germanic), royal (Norman), and regal (Latin), or these fascinating examples.

The problem is that many of these features are fairly stigmatized.

In terms of phonology, I make a conscious effort to maintain most of the distinctions above when I speak English, but on the other hand I flap my ‹t›s and ‹d›s in rapid speech to avoid sounding like a stuck-up prick. Similarly, I don’t maintain the wine–whine distinction, for example, unless, say, I’m working with a student on a story that takes place in the Southern US, because I would sound like a dick who’s trying to sound like a Southern gentleman or something. I still teach the distinction, if only to explain why there is such a difference in the orthography to begin with even if I tell students not to observe it when actually speaking. When I speak Hebrew, I most certainly don’t make those traditional ethnolect distinctions—that would come across as being either unbelievably pedantic or outright mocking. When I speak Japanese or other languages, well, I generally don’t know them well enough to maintain all the distinctions as I would like to, even those that aren’t stigmatized, but I do make an effort to at least observe those distinctions when the orthography makes them clear enough (and stick to the standard in Japanese).

In terms of grammar, I don’t teach dialectical English irregular forms. At most, I gloss over them with a sentence or two, and leave it at that. I assume my average student would hardly read books or watch films or TV shows that take place in Appalachia or what-have-you, certainly not without subtitles anyway. If I ever got a particularly advanced student, however… I would still be reluctant, as I am hardly over-familiar with those dialects myself, and don’t want to mislead them. In Hebrew, on the other hand, my grammar and spelling do tend to be very conservative to the point of anachronism sometimes (like, I generally follow the BuMP rule when I speak; most Israelis don’t), but I balance it out with a decent amount of slang.

In terms of lexical items, I pretty much avoid teaching dialectical archaisms altogether. Those are almost entirely useless for students, and I don’t even speak the dialects that use them, so I can’t say for a fact which dialecticalisms are even in current use. In Hebrew, I might make some detours, but that’s because truly archaic words, that wouldn’t even be used in tongue-in-cheek, are a rarity, and oftentimes they share roots with more common words, so they can cement the understanding of those roots more readily.

If no socio-linguistic considerations (or my own fluency) were a complete non-issue?

In English:

I’d make an effort to maintain all of the distinctions mentioned above, including those that are observed today only by a handful of older people from rural areas.

I’d pronounce ‹gh› in words like right and weight to tell them apart from rite and wait.

I’d use thou and AAE grammar and any dialectical archaism or even Anglish coinage I could get away with.

And, of course, I’d use my gender-neutral pronoun system for everyone except trans people who might get dysphoric.

In Hebrew:

I’d speak Hebrew with extremely conservative pronunciation, like BCE-level ancient, making all of the distinctions mentioned above.

On top of those, I would distinguish between the voiceless alveolar sibilant and lateral fricatives (which was lost very early on), so I pronounce סוֹרֵר /soː.ˈreːr/ ‘unruly, recalcitrant’ and שׂוֹרֵר /ɬoː.ˈreːr/ ‘existing, prevailing’ (both in masc. sing.) differently (rather than pronounce both like the first).

I’d reintroduce syllable-final glottal stops so that the orthography and grammar finally make a lick of sense.

On the other hand, I would think of a system to do away with gendered language in Hebrew that still made internal sense.

In Japanese:

I’d speak Japanese with all of the distinctions mentioned above, the fact that they characterize two parts of Japan that are practically on oppsite ends of the country be damned.

I might maybe even bring back a few obsolete features, like nasal vowels or the syllable ye and palatalized consonants before e (when applicable), because they make go-on and kan-on relationships clearer, and also clear up their relationship to Mandarin and other languages with extensive Sinitic vocabulary. (Although I doubt there are modern dialects that do that today, certainly not in a discriminating way, so I might give up on that.)

And, of course, I would do it all with Kansai pitch accent, or at least There are too many homophones, damnit, I gotta tell them apart SOMEHOW!

In Mandarin:

I’d speak Mandarin with Standard Taiwanese pronunciation.

Maybe I’d even use the Old National Pronunciation—what with my background in Japanese, it would save me a lot of memorizing, because I’d remember that all the characters that ended with a voiceless consonant in Japanese have the same tone in Mandarin.

Hell, I might even reintroduce the distinction between /e/, /ɔ/, and /a/.

In Cantonese:

I’d distinguish between the tones and the initial consonants, as mentioned above.

In addition, I might even bring back the distinction between alveolar and palato-alveolar sibilants that died in 1950—it’ll certainly make things easier for me, as I’ve learned some Mandarin in the past.

In Korean:

I’d speak a mix of dialects preserving all of the above distinctions and then some; I’d probably sound a lot like I were from North Korea, but in this scenario this wouldn’t matter.

In Vietnamese:

North-central dialect all the way.

In that scenario, the only thing that would stop me from talking like that would be comprehensibility. It would definitely be an issue—even today English speakers would probably be thrown off by pronouncing the ‹gh›, for one, and I’m sure my variety of Hebrew would be incomprehensible to most native speakers today.

But for now, I’ll make do with what I got, I guess.

—

Endnotes

¹ Most dialects that do mix them up generally pronounce them like the former in each pair.

² These distinction traditionally exists in Scotland; Ireland has a two-way split that works differently. On this note, I’d also count distinctions between e.g. wait and weight, but at this point it’s already Scots, not English. (Which is just another reason I love Scots so much, along with its lexical conservatism.)

³ This distinction, as well as the three that follow, are exceedingly rare.

⁴ The phranyngealized voiceless alveolar sibilant affricate was not preserved as such in any ethnolect: it either became a pharyngealized voiceless alveolar sibilant fricative (in Yemenite and Mizrahi Hebrew), or it simply lost its pharyngealization (in Sephardi and Ashkenazi Hebrew, and Modern Israeli Hebrew)—e.g. צַד /t͡sˤäd/ > /sˤäd/, /t͡säd/ ‘side’. Barring the exceedingly rare loanword, I could not think of a single minimal pair such as the one given above.

⁵ For the record: I was raised speaking English alongside Hebrew, albeit in a non-Anglophone country, and a lot of research went into my solution to ensure that it’s based on precedent rather than be a tasteless neologism.

⁶ There are other genderless languages as well, but they’re either super-niche or spoken by communities that aren’t as progressive, or both.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cool read, thanks for posting!

As a knower of Latin, I wanted to tack on a little blurb about the Latin forms, and maybe some of the reasons for their diverging evolution. Let me start by saying that the information I have absolutely DOES NOT explain why sapio > sé while capio > quepo; why that split happened is likely what you said, the orthography muddying things up.

You see, Latin verbs actually belong to THREE (3) patterns simultaneously, known as the Present Stem, the Perfect Stem, and the Supine Stem. There are 4 (and a half) patterns for the present stem, called the conjugations.

"capiō, capĕre" and "sapiō, sapĕre" do follow the same conjugation, called the 3rd io (this is the half-conjugation). The defining feature of 3rd conjugation is the short "ĕ" in the infinitive (as opposed to the long "ā", "ē", or "ī" of 1st, 2nd, and 3rd, respectively); but regular 3rd conjugation features a 1st person singular ending in just -ō, with either a consonant or a "u" preceding it (the "u" is part of the stem and does not interact with the vowel of the verb ending in any way). Examples of such regular 3rds are "dīcō, dīcĕre" > decir and "cōnstituō, cōnstituĕre" > constituir.

Notice that the short "ĕ" of the infinitive becomes an "i" in Modern Spanish; that's partly down to the sound changes between Latin and Spanish, but it was also a feature in Latin. The "ĕ" only appears in less than a handful of forms in Latin (the present active infinitive, the singular present imperative, and the 2nd person singular passive), otherwise being deleted (as in the present first person singular forms, both active and passive) or shifted to another vowel (typically "i", as it would become in Spanish, but "u" in the present 3rd person singular).

3rd io is a special case of the 3rd conjugation, which features a somewhat phantom "i" at the end of the stem. In the present tense, it only manifests in the 1st person singular (the signiture "iō" ending that gives the pattern its name) and the 3rd person plural, (-iunt). In the places that regular 3rd shows an "ĕ", 3rd io will as well (with no extra "i" in sight), and everywhere else outside the present tense that uses this stem will be identical to 4th conjugation.

As an aside, this is actually something your charts got wrong. The 2nd person singular forms should be "capĭs" and "sapĭs" with SHORT "ĭ", since these are 3rd io verbs (4th would have the long "ī", but would also have it -īmus and -ītis).

So up to this point, "capiō" and "sapiō" are identical. But they differ in how they deal with the perfect stem, and THAT is origin of the Spanish preterite. You see, there are 8 different transformation that can be applied (and multiple can be applied for extra difficulty!) to create the Perfect stem. I won't get into all of here, and just focus on the two patterns the "capiō" and "sapiō" follow.

I'll actually start with "sapiō". It follows what most would consider to be the "default" perfect formation strategy in Latin (which is a bit odd, since most 2nd and 3rd conjugation verbs DON'T). This strategy is to add a "v" to the end of the present stem, thus sapĭ- > sapīv-. notice the phantom "ĭ" returns" and, in fact, lengthens; it's probably due to conflation with the 4th conjugation again, which has a long "ī" as its major vowel and does, on average, prefer this perfect formation.

On the other hand, "capiō" follows the 3rd or 4th most common strategy, ablaut, changing from căp- > cēp-. …And I just realized this doesn't explain the irregularites of caber's preterite at all; in fact, from what I (not a knower of spanish) can tell, caber and sé seem to have similar preterites, and the forms would make more sense starting from sapiō's patterns than capiō's, what with the "v" to vocalize and metastasize to form the "u".

*shrugs*

As a final note, the Supine stem forms the basis for the perfect passive. Capiō has a fairly regular 3rd conjugation supine, "captum", featuring no vowel before the supine stem's added -t. Sapio does not have passive forms, and thus has no supine stems.

Anyway, I hope my ramble about Latin conjugation was readable, enjoyable, and/or informative, even if it didn't really explain ANYTHING about this particular case.

Caber. Anyone who has looked at this verb has probably found themselves shaking their head, wondering how humans could allow a such an evil verb to continue. It's slowly been gaining media attention, recently being the target of a defamatory attack by tumblr user portugue. But how did we get to this point? Is its existence a commentary on the cruelty of human nature, or just sound change?

If you don't know what I'm talking about, caber, which means 'to fit', is pretty irregular in Spanish. The first person present form is quepo, which carries over to the subjunctive forms (quepa, quepas, etc.). And the preterite also has its own irregularities - cupe, cupiste, cupo, cupimos, and cupieron. If you're a little observant, you'll notice something: this is almost exactly like another verb, saber! The only difference is that the first person present form for saber is just sé. But the two followed the same path to get there!

Caber comes from the Latin verb capĕre, while saber comes from sapĕre. The present subjunctive of these two verbs seems pretty normal (but let it be said here -- I am not a Latin knower or anything):

So you're probably thinking, little Cappy was such a good kid, where did I go wrong as a mother? But no worries -- it was a sound change in the making for a long time.

See the /i/ that comes after the /p/ in both words? In this position (hiatus), the /i/ becomes a /j/ over time. For those who aren't familiar with IPA, the /j/ sound is equivalent to the sound of y in English words like yolk and yellow. This also kicked into motion the chain of events that led to French sache, from savoir.

What happens next? In a process called metathesis, the /p/ and the newly formed /j/ switch places. Methasis is a familiar process - this is the reason you pronounced spaghetti as pasketty as a kid. So anyway, we've now gone from /kapja/ to /kajpa/ (and we've lost the word final /m/ in the first person conjugation, but that's not important to this story). My dear Portuguese speakers will recognize this change, since this is the subjunctive for saber & caber -- saiba & caiba!

From here, the new diphthong /aj/ coalesces and becomes an /e/, leaving us wretched souls with /sepa/ and /kepa/, spelled sepa and quepa respectively.

For the present indicative forms, I would assume the same thing happens (though I couldn't find a source for this) -- sapio becomes sajpo then sepo and then the -po is dropped for sé, while quepo keeps a hold of it.

Why, then, is caber such a strange verb, while saber is just, well, normal? Does caber resent being stuck in her older sister's shadow? Truthfully, it's probably a combination of the orthography (throwing that <qu> in there when the rest of the conjugations are spelled with c, i mean, come on), the fact that saber is just a much more common verb, and the fact that sé drops the -po (could you imagine if it was yo sepo??? we might hate it just as much). It couldn't be the other way around, imagine if it were qué (-- que no qué! --no haces qué? --no qué! --qué? --tú sí cabes, pero no qué!)

I hope you learned something today! I wanted to unravel this mystery so I got in contact with one of my professors and he explained it to me :) Thanks for reading!!

233 notes

·

View notes

Text

PTerm

In this article Syntax New-Pn PTerm -Name -Id -Lcid -TermSet -TermGroup. Pterm is the terminal emulator program developed by Cyber1 staff, but there are others. Below are operating system releases for Pterm and others. The original PLATO terminals were of several types: Plato IV or Maggie. PTerm - A modern go module to beautify console output. A compound, usu. Of whiting and linseed oil, used to secure windowpanes, patch woodwork defects, etc. Any of various substances for sealing the joints of tubes or pipes. A mixture of lime and water with sand and plaster of Paris, used as a finish plaster coat.

Terminator Makeup Kit

Plato Emulator

Peter Mark Richman

Ptarmigan

Terminator

I use Unix terminal a lot in work, when i work with Pharo and ROS (PhaROS), switching regularly between Pharo and native terminal application (for ROS command line) is kind of inconvenient. I've been thinking of using a terminal emulator application for Pharo. Googling around, i found out that there is no such thing that is ready for production work on modern Pharo, except a prototype work of Pavel Krivanek available at: https://github.com/pavel-krivanek/terminal. However, that code is messy, buggy, and not ready for production work . So i decided to take my time to work on it.

I grabbed the code from Pavel's repository, kept and improved only the UI and protocol parts (fix display/keyboard event bugs, clean up unused code, etc.), then decided to implement my own FFI calls to the underlying system terminal.

Github: https://github.com/lxsang/PTerm

In-image FFI calls to spawn a tty in a child process

Since libc'sfork() does not work really well on Pharo, an in-image (no external C lib calls other than libc) solution to spawn a tty using classic fork() is not feasible in this case. An alternative way is to use posix_spawn(), this function allows to spawn a child process and execute an Unix command on that process (eg. /bin/bash). With posix_spawn and some setting functions (for IO redirection), i am able to spawn a Bash on a new child process and redirect its IO to Pharo using only in-image FFI calls to libC (no external C code needed). However, due to the limitation of posix_spawn we cannot control what happens inside the child process, including making the child process a new session leader (using setsid()). Consequently, the spawned tty is not fully interactive, the following warning will display:

The spawned shell works well for almost single process commands like ls, top, htop, etc, but does not support commands that require job control or command that creates new subprocess like ssh.

Fully interactive shell on Pharo using custom C lib

Since i really need a fully interactive shell, the classic way is to use fork() in an custom C library for spawning a tty in a child process, then make FFI calls to that library in Pharo whenever we want the terminal access. My solution in this case is similar to what Pavel did. However, the C code is a little bit different. The down side is that this solution requires gcc to be installed on the system. This allows to compile the custom C code to shared library on the first run of the application. The compilation is automatic and off-scene without user notice though.

Combine the two solutions into one application

The idea is that we can use the in-image solution as a fallback situation for the custom C library solution. On the first run, the application will try to compile the C code and make FFI calls to the compiled lib in order to spawn a fully interactive shell. For some reason, if the application fail to access or compile the C lib, a second attempt will be made by using the in-image FFI calls, if success, a shell without job control will be spawned.

Install on Pharo 7

Bugs are expected and welcome!

(redirected from Pterm) Also found in: Thesaurus, Encyclopedia.

put·ty

(pŭt′ē)n.pl.put·ties1.

a. A doughlike cement made by mixing whiting and linseed oil, used to fill holes in woodwork and secure panes of glass.

b. A substance with a similar consistency or function.

2. A fine lime cement used as a finishing coat on plaster.

3. A yellowish or light brownish gray to grayish yellow or light grayish brown.

tr.v.put·tied, put·ty·ing, put·ties

[French potée, polishing powder, from Old French, a potful, from pot, pot, from Vulgar Latin *pottus.]

American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition. Copyright © 2016 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

putty

(

ˈpʌtɪ) n, pl-ties

1. (Building) a stiff paste made of whiting and linseed oil that is used to fix glass panes into frames and to fill cracks or holes in woodwork, etc

2. (Building) any substance with a similar consistency, function, or appearance

3. (Building) a mixture of lime and water with sand or plaster of Paris used on plaster as a finishing coat

5. (Elements & Compounds) See putty powder

6. a person who is easily influenced or persuaded: he's putty in her hands.

7. (Colours)

a. a colour varying from a greyish-yellow to a greyish-brown or brownish-grey

8. up to putty informalAustral worthless or useless

vb, -ties, -tyingor-tied

[C17: from French potée a potful]

Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2014

put•ty1

(ˈpʌt i) n., pl. -ties,n.

1. a compound, usu. of whiting and linseed oil, used to secure windowpanes, patch woodwork defects, etc.

2. any of various substances for sealing the joints of tubes or pipes.

3. a mixture of lime and water with sand and plaster of Paris, used as a finish plaster coat.

4. a person or thing easily molded, influenced, etc.

v.t.

[1625–35; < French potée, literally, (something) potted. See pot1, -ee]

put•ty2

(ˈpʌt i) n., pl. -ties.

Random House Kernerman Webster's College Dictionary, © 2010 K Dictionaries Ltd. Copyright 2005, 1997, 1991 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

putty

Past participle: puttied

Terminator Makeup Kit

Gerund: puttying

Imperativeputtyputty

PresentI puttyyou puttyhe/she/it puttieswe puttyyou puttythey putty

PreteriteI puttiedyou puttiedhe/she/it puttiedwe puttiedyou puttiedthey puttied

Present ContinuousI am puttyingyou are puttyinghe/she/it is puttyingwe are puttyingyou are puttyingthey are puttying

Present PerfectI have puttiedyou have puttiedhe/she/it has puttiedwe have puttiedyou have puttiedthey have puttied

Past ContinuousI was puttyingyou were puttyinghe/she/it was puttyingwe were puttyingyou were puttyingthey were puttying

Past PerfectI had puttiedyou had puttiedhe/she/it had puttiedwe had puttiedyou had puttiedthey had puttied

FutureI will puttyyou will puttyhe/she/it will puttywe will puttyyou will puttythey will putty

Future PerfectI will have puttiedyou will have puttiedhe/she/it will have puttiedwe will have puttiedyou will have puttiedthey will have puttied

Future ContinuousI will be puttyingyou will be puttyinghe/she/it will be puttyingwe will be puttyingyou will be puttyingthey will be puttying

Present Perfect ContinuousI have been puttyingyou have been puttyinghe/she/it has been puttyingwe have been puttyingyou have been puttyingthey have been puttying

Future Perfect ContinuousI will have been puttyingyou will have been puttyinghe/she/it will have been puttyingwe will have been puttyingyou will have been puttyingthey will have been puttying

Past Perfect ContinuousI had been puttyingyou had been puttyinghe/she/it had been puttyingwe had been puttyingyou had been puttyingthey had been puttying

ConditionalI would puttyyou would puttyhe/she/it would puttywe would puttyyou would puttythey would putty

Past ConditionalI would have puttiedyou would have puttiedhe/she/it would have puttiedwe would have puttiedyou would have puttiedthey would have puttied

Collins English Verb Tables © HarperCollins Publishers 2011

Plato Emulator

Noun1.putty - a dough-like mixture of whiting and boiled linseed oil; used especially to patch woodwork or secure panes of glass

cement - something that hardens to act as adhesive material

filler - used for filling cracks or holes in a surface

Verb1.putty - apply putty in order to fix or fill; 'putty the window sash'

apply, put on - apply to a surface; 'She applied paint to the back of the house'; 'Put on make-up!'

Based on WordNet 3.0, Farlex clipart collection. © 2003-2012 Princeton University, Farlex Inc.

kyt

gitt

cam macunu

putty

[ˈpʌtɪ]

A.N → masillaf to be putty in sb's hands → ser el muñeco de algn

Collins Spanish Dictionary - Complete and Unabridged 8th Edition 2005 © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1971, 1988 © HarperCollins Publishers 1992, 1993, 1996, 1997, 2000, 2003, 2005

putty

[ˈpʌti]n → masticmput-up job n → coupmmontéput-upon [ˈpʊtəpɒn]adj I feel put-upon → Je trouve qu'on profite de moi.

Collins English/French Electronic Resource. © HarperCollins Publishers 2005

putty

1

n → Kittm; he was putty in her hands → er war Wachs in ihren Händen

Collins German Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged 7th Edition 2005. © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1980 © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1997, 1999, 2004, 2005, 2007

putty

[ˈpʌtɪ]n (for windows) → stucco, masticem da vetrai

Peter Mark Richman

to be putty in sb's hands (fig) → essere come la creta nelle mani di qn

Collins Italian Dictionary 1st Edition © HarperCollins Publishers 1995

putty

(ˈpati) noun

a type of paste made from ground chalk and oil, used to fix glass in windows etc. stopverf مَعْجونة لِتَثْبيت الزُّجاج маджун massa de vidraceiro kyt der Kitt kit στόκοςmasilla kitt بتونه kitti masticמרק पुटीन, पुट्टी, लेप gitt dempul kítti stucco パテ (접합제) 퍼티 kitas, glaistas tepe dempul stopverfkitt, sparkelmassekit ګلګل betume chit замазка git kit staklarski git kitt, spackel ปูนอุดรอยรั่ว cam macunu 油灰 замазка для вікон; шпаклівка سفيد�� اور السي تيل کا مرکب جو کھڑکي وغيرہ ميں شيشہ فٹ کرنے کے کام آتا ہے vữa, mát-tít 油灰

Kernerman English Multilingual Dictionary © 2006-2013 K Dictionaries Ltd.

Want to thank TFD for its existence? Tell a friend about us, add a link to this page, or visit the webmaster's page for free fun content.

Ptarmigan

Link to this page:

Terminator

0 notes

Photo

I got a 4 on the exam, but I’ve taken Spanish for 5 years at a high school level and I’m dual-enrolled in a college class, so hopefully I can help you out a little bit. (i know this test was last week but lol i forgot to post this so whatever. they’ll still be giving it next year)

1. You NEED to expose yourself to Spanish outside of class

This was legitimately the difference between a 4 and 5 in my case. This test is hard, there’s no other way to put it and it requires you to be able to use the language in all it’s forms: listening and speaking as well as reading or writing.

Some suggestions of how you can do that:

Listen to Spanish music while you study

here’s all the Latino spotify playlists to start

There’s a bunch of Spanish language movies and TV shows on Netflix. But if that’s not your jam, most Netflix-produced tv shows have the option to change the language to Spanish. See how much you can pick up (without subtitles) on your rewatch of Stranger Things or A Series of Unfortunate Events.

if you’re not at that level yet, turn on the English subtitles and see if you can tell how accurate they are.

change your phone’s language to Spanish. You’ll be forced to interact with it every day.

Talk to your friends who are also taking that class in Spanish once or twice a week and text them in Spanish as well. It’ll help you both practice.

Hopefully, your class is taught entirely in Spanish. If not, still try to take notes in the language and answer questions in it as well.

If you know someone in your family or have a friend who is a native speaker, use that resource. Call and talk to them or start emailing them or writing letters.

If all else fails, there a bunch of websites and apps that can connect you to native speakers. Look at the langblr community on tumblr or apps like Hellotalk, which connect you with native speakers.

2. Don’t try to translate what you’re listening to while you listen to it

This might seem like the exact opposite of what you need to do but trust me. The people in the listening sections of the tests are native speakers and your brain simply isn’t going to be able to go from Spanish to English fast enough to keep up.

Instead, don’t try to translate and write down notes of what you’re hearing in Spanish to go back to later. Otherwise, you’ll just get frustrated or behind and shut down for the rest of the selection. (I speak from experience.)

3. Know your complex tenses!

If you continue to study Spanish, you’re going to need to know them anyway, so you might as well know them now.

Demonstrating you know the difference between preterite and the imperfect or what triggers the subjunctive shows you have a grasp of the language that goes above and beyond basic present tense conjugations.

What I suggest you should definitely know:

preterite and imperfect

subjuntive (at least the present tense)

commands

future

conditional

participles

progressive (-ing words)

4. Know the right vocab.

This shouldn’t be the only vocab you should know, but there are some themes that tend to come up on the test pretty often.

The ones my teacher highlighted included:

technology

the environment

politics (developing countries)

the arts (usually there’s some reading/listening passages about authors, painters, etc.)

your future/travel (college scholarships, studying abroad and volunteering, etc.)

Also know your idiomatic and transition phrases. If you can make your essays flow more smoothly, you’ll score higher and sound more like a native speaker.

5. Tips, tricks, and other things you need to remember

One of the writing exercises is usually an email or a letter. The recipient will vary so know how to format both formal and informal letters: greetings, farewells, when to use tú or Usted, etc.

Like I said above, idiomatic and transition phrases, as well as complex tenses are your friends.

Circumlocution: a fancy word that basically means if you don’t know the word you want to say, use different ones to make the same point or talk around it. It might sound more awkward but it won’t completely paralyze you while writing your essay.

One of the speaking exercises will require you to compare your community with one in a Spanish speaking country. If you don’t have one you’re super familiar with already, pick one and study up a bit on the culture.

Take notes! Especially during the listening sections, jot some things down (in Spanish), especially for the longer ones or those they only play once.

6. Practice, Practice, PRACTICE

The exercises are timed. You want to get used to how long writing for 15 minutes are. You want to know how long speaking for 20 seconds feels (it’s a hell of a lot longer than you think it is sometimes).

Same goes for word counts. Figure out about how many words you write on a line so that way you don’t have to be counting word by word. Also, figure out how to hit that word count by using idiomatic expressions and transition phrases.

Getting familiar with how the exercises are set up and the format of the test is the most helpful thing you can do before you start. College Board posts past tests you can use to do this. They go from what is easiest for most people (reading) to hardest (speaking) so that definitely helps. (I found the listening section hardest though.)

7. You don’t have to be perfect.

Again, the test leaves room for you to make some mistakes. They know that, if you’ve been studying for three or four or five years and are not a native speaker, that you might forget an accent or leave out an “a” or forget to change “o” to “u” where you need to. As long as you’re making yourself understood, you’re on the right track.

Good luck! If you have any questions (or suggestions of your own), please send me an ask!

#isabel says things#isabel gives advice#how to pass your ap classes#ap study#ap spanish#ap spanish lang#spanish#language study#language learning#ap studyblr#long post#study tips#langblr#isabel's study suggestions

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conjuguemos—11:55 AM, Sunday, March 29th, 2020

Quick Confession: I make the deadlines for my blog posts at noon and midnight. One can see how bad I procrastinate through the times I leave on posts. Today, I woke up at 6:30 AM, but I am still almost waiting until the last few minutes to post it. Well, in truth it takes me about thirty minutes, or less, to type/write/compose these, so it is currently 11:30. Thank goodness for my typing speed.

Today will be about conjuguemos.com, so Spanish only. Of course, I am not saying that the Japanese language does not have conjugation, just that Conjuguemos does not support it. This is a very useful resource, although moreso for intermediate or advanced learners than beginners. As mentioned in previous posts, conjugation is a key element of grammar, and it is prevalent in English too; we just do not notice it. Hm, English verb conjugations might be an interesting blog topic for someday. But I digress.

Interesting. I just looked at Conjuguemos again, and it seems like it has a lot more resources than the last time I checked. I do remember seeing a whole thing about a beta version a year back, so maybe they came with the updates.

The best part of Conjuguemos would be its conjugation practice, wherein one can practice conjugating for a specific tense or all verb tenses—that might need to be saved for the advanced level. Beginners should probably focus on present indicative, which has many exceptions, and maybe present progressive, preterite, and imperfect. Intermediates could rotate between the above, future, conditional, imperative, subjunctive, and present perfect. Of course, this is just a vague outline, and there is nothing wrong with jumping around.

As expected, Conjuguemos also has a tab of grammar lessons, which include verb conjugations with conjugation tables, as well as articles like "ser" vs. "estar," "por" vs. "para," "saber" vs. "conocer," and "verbs like gustar," among others, which I was not originally aware of but am presently surprised by. Here, it is similar to Spanishdict, and while I prefer Spanishdict because I am more familiar with it, I think it would be worth it to use both for explanations on a topic for additional angles and better understanding.

Like Spanishdict, Conjuguemos has vocabulary lists. However, I am more partial to the vocabulary lists on Conjuguemos because they seem to be pulled from textbooks, which are typically more structured. That said, I have not delved into either's lists, but something about "colors" and "1000 words for Beginners" turns me away from Spanishdict.

Finally, Conjuguemos has listening practices. This was the one thing that completely caught me off guard, and I almost want to swear that it is new, but I also know that I can be very unobservant at times. They have speakers from different countries, which is quite promising—Spanish-learners may have problems adapting to different accents/dialects, so this makes for good practice. Anyway, I will check that out sometime this week and give a review of it on Thursday.

0 notes

Note

hi, I was wondering when to switch between the imperfect and preterite tenses? I’ve been reading some spanish texts and I’ve noticed that the imperfect is the main tense used, but I also see the preterite thrown in sometimes.

I'll link to my other things I've done on this in a reblog since I'm on my phone atm but it comes down to narration vs action a lot of the time

In linguistic terms "perfect" means "completed" [lit. "thoroughly done"], so "imperfect" means "not yet completed"... the imperfect tense is used for things that may or may not still be happening or continuing, so it is often used for narration and description

Imperfect is often used for:

narration, description

continuous past ("was doing", "was eating", "was sleeping")

used to, was in the habit of

telling time - always imperfect (era la una, eran las dos, etc)

soler + infinitive as "used to" as past tense is ALWAYS imperfect; there is no preterite form accepted so you normally only see soler in present tense "to be in the habit of" and imperfect "used to"

Preterite is commonly called "simple past", where it is things that happened and are done, and they are actions

In terms of reading, it's more that imperfect introduces something and describes it, while the preterite shows an "interruption" or "the action"

A common example I like to use:

Dormía y sonaba el teléfono. = I was sleeping and the phone was ringing. [imperfect + imperfect; no interruption, background description] Dormía y sonó el teléfono. = I was sleeping and the phone rang. [imperfect + preterite; involves an "interruption" of an "action" to the background description]

If you use the two imperfect, it sounds like someone was sleeping through the phone ringing, and/or that the phone ringing was part of the background. If you use imperfect and then preterite, it implies the preterite was a sudden occurrence that breaks up the narration.

...

But please be aware that most verbs can exist in the two different tenses and it becomes a matter of how they're understood...

Assuming 3rd person singular - se dormía would be "was falling asleep", while se durmió would be "fell asleep"

Sometimes it really depends on the mood - especially with ser and estar in preterite or imperfect - like you don't see too much difference between ¿dónde estabas? "where were you?" vs. ¿dónde estuviste? "where were you?" except in context where preterite feels more like interrogation "where were you (at that specific time)?"

...

There are a handful of verbs that change meaning depending on preterite and imperfect

I'll link things below that will explain it more but in general be wary of:

poder

no poder

querer

no querer

conocer

saber

haber

And also tener. Where normally tener is imperfect as preterite tener can come across as "to obtain", but there are so many idiomatic ways of using tener like "hungry", "thirsty", "hot/cold", and your age that there are times when preterite could be used. Still, in general, preterite tener is most often a synonym of conseguir or obtener as "to get"

-

Additional links:

A Linguistic Perspective on the Spanish Past

More in-depth explanation of imperfect

Using soler

The imperfect tag

The preterite tag

Preterite and Imperfect Contrasted from Bowdoin

Spanish Tenses & Moods Masterpost

#spanish#langblr#learn spanish#language learning#spanish lessons#asks#long post#la gramatica#preterite#imperfect#the eternal struggle

130 notes

·

View notes

Note

Alright teacher🥸,

Who uses the Future(?) Subjunctive? I'm reading a novel with dialogue "Ojalá fuese tan fácil" and now I have a headache. My eyes read it as "Ojalá fuera tan fácil". Are there differences between these subjunctive moods? 🫠

Today, fuese is more common in Spain, and fuera would be more common in the US and Latin America

This is actually imperfect subjunctive, and if you look in a conjugation chart in a textbook you'll see the two forms presented as largely synonymous

For Spain though, fuera tends to be more used for past subjunctive, while fuese is more common for future or hypothetical subjunctive

You can consider it the difference between "I wish it was that easy" vs. "I wish it were that easy"; both make sense to an English-speaker but you're technically using different conjugations for the same grammatical mood

A Spanish-speaker might see "was" and "were" and get confused, but an English-speaker might see it as a stylistic choice and one that ultimately communicates the same idea

...

This is a bit of history lesson. But originally there was imperfect subjunctive [past subjunctive] and there was future subjunctive and they were different ideas entirely

To add to the confusion; the -ara/-iera endings like fuera were once pluperfect forms because haber was not used in perfect tenses as commonly as it is now... before that haber was used almost like tener "to have" [as in some things will show you he dos hijos "I have two children"; there are some holdovers in language like he de limpiar is "I must clean" exactly the same idea as tengo que limpiar]

...

So! In an older historical setting, fuera could have been understood as "had been"

In journalism you see remnants of it; naciera is sometimes used as "was born" [synonymous with nació preterite in this case]; but you'd never see naciese used in that context

Pluperfect then got replaced with haber in the imperfect tense + past participle...

In other words, hablara "had spoken" become había hablado, comiera to había comido, viviera to había vivido

If you read older Spanish in its original form, they modernize a lot of this. If you read Don Quixote, your version might be the older 16th century one which has more of the archaic verb usage, but there are also modernized updated ones

[Spanish also uses more modern language for many current Shakespeare translations so Shakespeare in Spanish actually makes more sense to me than the older English]

...

More history! The future subjunctive actually ends in -are/-iere [hablare, comiere, viviere]

You rarely see the actual future subjunctive used today. The only times I've seen it were when I was reading old Spanish. Occasionally you see si fuere menester which is extremely old-fashioned but it's "in the event of" for some contracts - literally "should it be necessary"

Future subjunctive described future events that would use subjunctive, primarily hypothetical situations like "in the event of" or "should it come to pass"

The true future subjunctive here merged with imperfect subjunctive [a past subjunctive] into the current hablara/hablase, comiera/comiese, viviera/viviese forms

Today, it's considered a style choice. Spain makes a clearer distinction than Latin America

Journalism sometimes uses the imperfect subjunctive -ara/-iera forms as pluperfect the way it used to be

-

There's some other finer details involved so please take this as an overview, but for your purposes either fuese or fuera makes sense. I don't think I've seen many Latin Americans use the fuese but that could be my own experience

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you explain when to use imperfect vs preterite vs perfect past tense? I struggle knowing when to use which.

So this is going to be just a quick overview of preterite and imperfect, and I'll include more links now for more in depth things that you can look at because I talk about them very often

Preterite tag

Imperfect tag

The Perfect Tenses w/ haber

-

In many cases preterite and imperfect are both valid choices, depending on what you're trying to express: leí "I read" vs. leía "I was reading / I used to read" as an example

Preterite in Spanish is also known as "simple past"; it's used for things that have definitely happened. By "definitely" I mean there's often a time phrase associated with it that says "this happened at this time"

It typically is action or something that did specifically happen, so it can read as very clinical and matter of fact

...

Imperfect on the other hand has more uses. The linguistic term "imperfect" means "not yet completed"

Imperfect is often used with narration and description, describing the weather, the time, personalities

But the big thing that I find helpful is that in general the imperfect tense seems to be narration, while the preterite seems to be an interruption or action.

Whether you choose preterite or imperfect in some cases is more about how much description you're giving, as imperfect gives you a scenario, while preterite shows an action taking place in that scenario.

Dormía y entonces sonó el teléfono. = I was sleeping and then the phone rang. Dormía mientras sonaba el teléfono. = I was sleeping while the phone was ringing. [implying "I" didn't wake up] Dormí y sonó el teléfono. = I slept, and the phone rang. [two preterites imply a list of actions, like recalling a memory

The other very important function of imperfect tense is that it can mean "used to"; this can be done with or without the verb soler "to be in the habit of"

*Quick note on soler; it can't exist in preterite, it's usually in present tense suele ir a la playa "he/she normally goes to the beach" or imperfect solía ir a la playa "he/she would go to the beach". Because the imperfect tense can mean multiple things depending on context, soler adds a special bit of emphasis on "used to" to clear up any confusion:

Iba a la playa. = I was going to the beach. [imperfect continuous/progessive] Iba a la playa. = I used to go the beach. [imperfect, marking habitual] Solía ir a la playa. = I used to go to the beach. [habitual; soler being a clear marker of habitual]

Another common one is vivir. You could say vivía en la ciudad to mean "I lived in the city" OR "I used to live in the city", but if you wanted to be very clear - solía vivir en la ciudad "I used to live in the city"

Additional Notes:

You can only tell time in the past with imperfect - era la una, eran las dos, eran las tres etc

You can do the passive voice with preterite + past participle, and it only works with preterite here

-

The perfect tenses are a bit of a special case. I never know quite how to classify them because they can be in pretty much any tense, and they exist in indicative and subjunctive

Essentially though, "perfect" means "thoroughly done"; the same linguistic root as "imperfect" being "not yet completed"

Perfect tenses use a conjugation of haber + a past participle, and some past participles are irregular... as an example hacer "to done" turns into hecho "done"

Past participles are useful to know because they're also frequently the adjectival forms of verbs... like haber roto "to have broken", but then as an adjective roto/a is "broken"