#environmental studies books publishers.

Text

PM Publishers Pvt. Ltd. (PMP) is a leading publishing house of educational school books. PMP books incorporate the projected NEP 2020, NIPUN BHARAT and NCF 2022 guidelines by MHRD, Gol, the Department of School Education & Literacy, MoE, Gol, and NCERT respectively. For providing cost-effective quality books, the prescribed curriculum framed by NCERT/ SCERT based for the CBSE, ICSE and other state boards forms a basis for us to cater to the needs of all stakeholders.

In a short span of time, the house has created a niche amongst educators. More than 4000 established schools both in India and abroad have already appreciated the significant presence of our books. The books are supported with the latest technology like AR Apps, Multimedia, Assessment Tools, Question Paper Generator, and Quiz Generator. Explore more

Links: https://www.pmpublishers.in/

#Books publishers#computer books publishers#gk books publishers#art & craft books publishers#artificial intelligence books publishers#data science books publishers#english grammar books publishers#environmental studies books publishers.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

NASA Inspires Your Crafty Creations for World Embroidery Day

It’s amazing what you can do with a little needle and thread! For #WorldEmbroideryDay, we asked what NASA imagery inspired you. You responded with a variety of embroidered creations, highlighting our different areas of study.

Here’s what we found:

Webb’s Carina Nebula

Wendy Edwards, a project coordinator with Earth Science Data Systems at NASA, created this embroidered piece inspired by Webb’s Carina Nebula image. Captured in infrared light, this image revealed for the first time previously invisible areas of star birth. Credit: Wendy Edwards, NASA. Pattern credit: Clare Bray, Climbing Goat Designs

Wendy Edwards, a project coordinator with Earth Science Data Systems at NASA, first learned cross stitch in middle school where she had to pick rotating electives and cross stitch/embroidery was one of the options. “When I look up to the stars and think about how incredibly, incomprehensibly big it is out there in the universe, I’m reminded that the universe isn’t ‘out there’ at all. We’re in it,” she said. Her latest piece focused on Webb’s image release of the Carina Nebula. The image showcased the telescope’s ability to peer through cosmic dust, shedding new light on how stars form.

Ocean Color Imagery: Exploring the North Caspian Sea

Danielle Currie of Satellite Stitches created a piece inspired by the Caspian Sea, taken by NASA’s ocean color satellites. Credit: Danielle Currie/Satellite Stitches

Danielle Currie is an environmental professional who resides in New Brunswick, Canada. She began embroidering at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic as a hobby to take her mind off the stress of the unknown. Danielle’s piece is titled “46.69, 50.43,” named after the coordinates of the area of the northern Caspian Sea captured by LandSat8 in 2019.

An image of the Caspian Sea captured by Landsat 8 in 2019. Credit: NASA

Two Hubble Images of the Pillars of Creation, 1995 and 2015

Melissa Cole of Star Stuff Stitching created an embroidery piece based on the Hubble image Pillars of Creation released in 1995. Credit: Melissa Cole, Star Stuff Stitching

Melissa Cole is an award-winning fiber artist from Philadelphia, PA, USA, inspired by the beauty and vastness of the universe. They began creating their own cross stitch patterns at 14, while living with their grandparents in rural Michigan, using colored pencils and graph paper. The Pillars of Creation (Eagle Nebula, M16), released by the Hubble Telescope in 1995 when Melissa was just 11 years old, captured the imagination of a young person in a rural, religious setting, with limited access to science education.

Lauren Wright Vartanian of the shop Neurons and Nebulas created this piece inspired by the Hubble Space Telescope’s 2015 25th anniversary re-capture of the Pillars of Creation. Credit: Lauren Wright Vartanian, Neurons and Nebulas

Lauren Wright Vartanian of Guelph, Ontario Canada considers herself a huge space nerd. She’s a multidisciplinary artist who took up hand sewing after the birth of her daughter. She’s currently working on the illustrations for a science themed alphabet book, made entirely out of textile art. It is being published by Firefly Books and comes out in the fall of 2024. Lauren said she was enamored by the original Pillars image released by Hubble in 1995. When Hubble released a higher resolution capture in 2015, she fell in love even further! This is her tribute to those well-known images.

James Webb Telescope Captures Pillars of Creation

Darci Lenker of Darci Lenker Art, created a rectangular version of Webb’s Pillars of Creation. Credit: Darci Lenker of Darci Lenker Art

Darci Lenker of Norman, Oklahoma started embroidery in college more than 20 years ago, but mainly only used it as an embellishment for her other fiber works. In 2015, she started a daily embroidery project where she planned to do one one-inch circle of embroidery every day for a year. She did a collection of miniature thread painted galaxies and nebulas for Science Museum Oklahoma in 2019. Lenker said she had previously embroidered the Hubble Telescope’s image of Pillars of Creation and was excited to see the new Webb Telescope image of the same thing. Lenker could not wait to stitch the same piece with bolder, more vivid colors.

Milky Way

Darci Lenker of Darci Lenker Art was inspired by NASA’s imaging of the Milky Way Galaxy. Credit: Darci Lenker

In this piece, Lenker became inspired by the Milky Way Galaxy, which is organized into spiral arms of giant stars that illuminate interstellar gas and dust. The Sun is in a finger called the Orion Spur.

The Cosmic Microwave Background

This image shows an embroidery design based on the cosmic microwave background, created by Jessica Campbell, who runs Astrostitches. Inside a tan wooden frame, a colorful oval is stitched onto a black background in shades of blue, green, yellow, and a little bit of red. Credit: Jessica Campbell/ Astrostitches

Jessica Campbell obtained her PhD in astrophysics from the University of Toronto studying interstellar dust and magnetic fields in the Milky Way Galaxy. Jessica promptly taught herself how to cross-stitch in March 2020 and has since enjoyed turning astronomical observations into realistic cross-stitches. Her piece was inspired by the cosmic microwave background, which displays the oldest light in the universe.

The full-sky image of the temperature fluctuations (shown as color differences) in the cosmic microwave background, made from nine years of WMAP observations. These are the seeds of galaxies, from a time when the universe was under 400,000 years old. Credit: NASA/WMAP Science Team

GISSTEMP: NASA’s Yearly Temperature Release

Katy Mersmann, a NASA social media specialist, created this embroidered piece based on NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) global annual temperature record. Earth’s average surface temperature in 2020 tied with 2016 as the warmest year on record. Credit: Katy Mersmann, NASA

Katy Mersmann is a social media specialist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. She started embroidering when she was in graduate school. Many of her pieces are inspired by her work as a communicator. With climate data in particular, she was inspired by the researchers who are doing the work to understand how the planet is changing. The GISTEMP piece above is based on a data visualization of 2020 global temperature anomalies, still currently tied for the warmest year on record.

In addition to embroidery, NASA continues to inspire art in all forms. Check out other creative takes with Landsat Crafts and the James Webb Space telescope public art gallery.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

#NASA#creativity#fiber art#embroidery#art#art challenge#needlework#crafts#handmade#textile art#cross stitch#stitching#inspiration#inspo#Earth#Earth science#Hubble#James Webb Space Telescope#climate change#water#nebula#stars

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Inupiaq Books

This post was inspired by learning about and daydreaming about visiting Birchbark Books, a Native-owned bookstore in Minneapolis, so there will be some links to buy the books they have on this list.

Starting Things Off with Two Inupiaq Poets

Joan Naviyuk Kane, whose available collections include:

Hyperboreal

Black Milk Carbon

The Cormorant Hunter's Wife

She also wrote Dark Traffic, but this site doesn't seem to carry any copies

Dg Nanouk Okpik, whose available collections include

Blood Snow

Corpse Whale

Fictionalized Accounts of Historical Events

A Line of Driftwood: the Ada Blackjack Story by Diane Glancy, also available at Birchwood Books, is a fictionalized account of Ada Blackjack's experience surviving the explorers she was working with on Wrangel Island, based on historical records and Blackjack's own diary.

Goodbye, My Island by Rie Muñoz is a historical fiction aimed at younger readers with little knowledge of the Inupiat about a little girl living on King Island. Reads a lot like an American Girl book in case anyone wants to relive that nostalgia

Blessing's Bead by Debby Dahl Edwardson is a Young Adult historical fiction novel about hardships faced by two generations of girls in the same family, 70 years apart. One reviewer pointed out that the second part of the book, set in the 1980s, is written in Village English, so that might be a new experience for some of you

Photography

Menadelook: and Inupiaq Teacher's Photographs of Alaska Village Life, 1907-1932 edited by Eileen Norbert is, exactly as the title suggests, a collection of documentary photographs depicting village life in early 20th century Alaska.

Nuvuk, the Northernmost: Altered Land, Altered Lives in Barrow, Alaska by David James Inulak Lume is another collection of documentary photographs published in 2013, with a focus on the wildlife and negative effects of climate change

Guidebooks (i only found one specifically Inupiaq)

Plants That We Eat/Nauriat Niģiñaqtuat: from the Traditional Wisdom of Iñupiat Elders of Northwest Alaska by Anore Jones is a guide to Alaskan vegetation that in Inupiat have subsisted on for generations upon generations with info on how to identify them and how they were traditionally used.

Anthropology

Kuuvangmiut Subsistence: Traditional Eskimo Life in the Latter Twentieth Century by Douglas B. Anderson et al details traditional lifestyles and subsistance customs of the Kobuk River Inupiat

Life at the Swift Water Place: Northwest Alaska at the Threshold of European Contact by Douglas D. Anderson and Wanni W. Anderson: a multidisciplinary study of a specific Kobuk River group, the Amilgaqtau Yaagmiut, at the very beginning of European and Asian trade.

Upside Down: Seasons Among the Nunamiut by Margaret B. Blackman is a collection of essays reflecting on almost 20 years of anthropological fieldwork focused on the Nunamiut of Anuktuvuk Pass: the traditional culture and the adaption to new technology.

Nonfiction

Firecracker Boys: H-Bombs, Inupiat Eskimos, and the Roots of the Environmental Movement by Dan O'Neill is about Project Chariot. In an attempt to find peaceful uses of wartime technology, Edward Teller planned to drop six nukes on the Inupiaq village of Point Hope, officially to build a harbor but it can't be ignored that the US government wanted to know the effects radiation had on humans and animals. The scope is wider than the Inupiat people involved and their resistance to the project, but as it is no small part of this lesser discussed moment of history, it only feels right to include this

Fifty Miles From Tomorrow: a Memoir of Alaska and the Real People by William L. Iģģiaģruk Hensley is an autobiography following the author's tradition upbringing, pursuit of an education, and his part in the Alaska Native Settlement Claims Act, where he and other Alaska Native activists had to teach themselves United States Law to best lobby the government for land and financial compensation as reparations for colonization.

Sadie Bower Neakok: An Iñupiaq Woman by Margaret B. Blackman is a biography of the titular Sadie Bower Neakok, a beloved public figure of Utqiagvik, former Barrow. Neakok grew up one of ten children of an Inupiaq woman named Asianggataq, and the first white settler to live in Utqiagvik/Barrow, Charles Bower. She used the out-of-state college education she received to aid her community as a teacher, a wellfare worker, and advocate who won the right for Native languages to be used in court when defendants couldn't speak English, and more.

Folktales and Oral Histories

Folktales of the Riverine and Costal Iñupiat/Unipchallu Uqaqtuallu Kuungmiuñļu Taģiuģmiuñļu edited by Wanni W. Anderson and Ruth Tatqaviñ Sampson, transcribed by Angeline Ipiiļik Newlin and translated by Michael Qakiq Atorak is a collection of eleven Inupiaq folktales in English and the original Inupiaq.

The Dall Sheep Dinner Guest: Iñupiaq Narratives of Northwest Alaska by Wanni W. Anderson is a collection of Kobuk River Inupiaq folktales and oral histories collected from Inupiat storytellers and accompanied by Anderson's own essays explaining cultural context. Unlike the other two collections of traditional stories mentioned on this list, this one is only written in English.

Ugiuvangmiut Quliapyuit/King Island Tales: Eskimo Historu and Legends from Bering Strait compiled and edited by Lawrence D. Kaplan, collected by Gertrude Analoak, Margaret Seeganna, and Mary Alexander, and translated and transcribed by Gertrude Analoak and Margaret Seeganna is another collection of folktales and oral history. Focusing on the Ugiuvangmiut, this one also contains introductions to provide cultural context and stories written in both english and the original Inupiaq.

The Winter Walk by Loretta Outwater Cox is an oral history about a pregnant widow journeying home with her two children having to survive the harsh winter the entire way. This is often recommended with a similar book detailing Athabascan survival called Two Old Women.

Dictionaries and Language Books

Iñupiat Eskimo Dictionary by Donald H. Webster and Wilfred Zibell, with illustrations by Thelma A. Webster, is an older Inupiaq to English dictionary. It predates the standardization of Inupiaq spelling, uses some outdated and even offensive language that was considered correct at the time of its publication, and the free pdf provided by UAF seems to be missing some pages. In spite of this it is still a useful resource. The words are organized by subject matter rather than alphabetically, each entry indicating if it's specific to any one dialect, and the illustrations are quite charming.

Let's Learn Eskimo by Donald H. Webster with illustrations by Thelma A. Webster makes a great companion to the Iñupiat Eskimo Dictionary, going over grammar and sentence structure rather than translations. The tables of pronouns are especially helpful in my opinion.

Ilisaqativut.org also has some helpful tools and materials and recommendations for learning the Inupiat language with links to buy physical books, download free pdfs, and look through searchable online versions

151 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm guessing that as a graduate student you have read a zillion and one documents and books and papers and things in your field. Would it be outrageous to ask for recommendations/your favorites? I'm really interested in learning more about the history of Native land use and food systems in the midwest (which I suppose is a very long history, I'd be happy learning about any time period), prairie ecology, and the current outlook for native plants and pollinators (and conservation recommendations). Even one recc for each would be amazing. Feel free to postpone this ask if you're too busy! P.S. can't wait to read your dissertation.

This is a big ask, and I get a lot of these types of asks! In the future it'd be nice if people were more specific about their interests and not asking about general, huge topics. There's a level that you can and should be googling yourself! Many academic papers are online for free through sites like academia.edu and I'm not a search engine!

General answer if you're interested in this range of topics is Robin Wall Kimmerer's Braiding Sweetgrass. She comes from the midwest and writes some on prairie and the book is all about Indigenous science stewardship.

Otherwise, the topics you're asking for don't have one single source that will tell you everything you're looking for. People make small studies of one community, one ecosystem, one plant. Whether it's ecology or ethnobotany, there's no one making compendiums of info, especially not in the midwest. That's why I do the work I do, but even what I do is imperfect. Be suspicious of anyone who/any text that claims to be comprehensive on a huge, complex subjects; they probably are bsing you.

Indigenous Land Mgmt:

Two good recent papers:

The subject of indigenous wild management is more intensely covered in California (M. Kat Anderson) and Vancouver (Nancy J. Turner). Those two authors are great for both nuts and bolts chat and philosophical perspectives about how people have lived in and altered and restored their ecosystems.

A compelling academic book on the subject is Roots of Our Renewal:

Ethnobotany and Cherokee Environmental Governance by Clint Carroll, which is just as much about philosophy, knowledge production and protection and community building, as plants.

Prairie Conservation Practices:

Like I said above, currently published stuff is about very specific interactions and focuses, like a particular pollinator group in a particular plant. What you're looking for, a generalist summary of the field, doesn't really exist.

If you're looking for plant lists and how-tos Tallgrass Restoration Handbook or the Tallgrass Prairie Center Guide. Do not go for Ben Voigt. If you're looking for a general conceptual entry to Midwest conservation/restoration, there's Ecological Restoration in the Midwest

If you're looking for general recommendations for free, Xerces.org is the resource for bee-friendly landscaping and planting.

If you live near a University or Arboretum or Botanic Garden, this is the kind of thing where you should just browse the shelves near the books I've recommended! Chances are you have free access to the libraries, if not the ability to check the books out yourself!

#this is imperfect but it took 40 minutes just to put this together#please be considerate of people's time#long post

198 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey!! do you have any recs for books/reading about veganism?

full disclosure, i don't read a bunch on veganism in terms of animal and environmental ethics, because the graphic depictions of abuse/violence/etc. often featured in them i find extremely upsetting. that being said, i do have a few readings - not all books - that i can confidently recommend, as well as a few cookbooks i love!

general theory/etc readings:

Sunaura Taylor, Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation

Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals

Disability and Animality: Crip Perspectives in Critical Animal Studies (edited collection PDF linked!!)

Ruth Ozeki, My Year of Meats (novel)

Lauren Berlant (z"l), Cruising Veganism (the link is to a pdf on my google drive bc I can't find it atm on google scholar)

Some books on my TBR are:

Julia Feeliz Brueck, Veganism of Color: Decentering Whiteness in Human and Nonhuman Liberation

Han Kang, The Vegetarian (novel)

The Routledge Handbook of Vegan Studies - these handbooks always have both hits and misses, but I think it's worth checking out!

My favorite vegan cookbooks:

Vegan Richa's Indian Kitchen & Vegan Richa's Everyday Kitchen

The Vegan Table (this is tragically out of print now but easy to get used!)

The Vegan Chinese Kitchen

Vegetable Kingdom

Also, The Veginners Cookbook is a great resource for new vegans/people interested in trying veganism, published by a blogger I've liked for a while.

hope this helps!

200 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Edward Burtynsky, “African Studies”

From the diamond mines of South Africa to the richly textured landscape of Namibia’s Tsaus Mountains, the series spotlights the sub-Saharan region and its reserves of metals, salt, precious gemstones, and other ores.

“I am surveying two very distinct aspects of the landscape,” he says in a statement, “that of the earth as something intact, undisturbed yet implicitly vulnerable… and that of the earth as opened up by the systematic extraction of resources.”

Taken over seven years in ten nations—these include Kenya, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, Senegal, South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Madagascar, and Tanzania—the aerial photos, which are compiled in a forthcoming book published by Steidl, present a dichotomy between a region irrevocably altered by humanity and one of immense possibility.

Since 2013 when it launched its Belt and Road initiative, China has invested billions of dollars in expanding its global presence, with many African nations as targets. This growth, along with international competition for access and power on the continent, has widespread economic, environmental, and governmental impacts, which Burtynsky explores through the series.

#art#photography#aerial#africa#human footprint#humanrights#edward burtynsky#south africa#landscape#kenya#nigeria#ethiopia#senegal#ghana#china#human impact#nature rights#poisened land#Consumerism

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jade S. Sasser has been studying reproductive choices in the context of climate change for a quarter century. Her 2018 book, Infertile Ground, explored how population growth in the Global South has been misguidedly framed as a crisis—a perspective that Sasser argues had its roots in long-standing racial stereotypes about sexuality and promiscuity.

But during the Covid-19 pandemic, Sasser, an environmental scientist who teaches at UC Riverside, started asking different questions, this time about reproductive choices in the Global North. In an era in which the planet is getting hotter by the day, she wondered, is it morally, ethically or practically sound to bring children into the world? And do such factors as climate anxiety, race, and socioeconomic status shape who decides to have kids and who doesn’t?

The result is her latest book, Climate Anxiety and the Kid Question, published last month by the University of California Press, which centers on a range of issues that are part of a broader conversation among those who try to practice climate-conscious decisionmaking.

From the outset, Sasser cautions that her work does not attempt to draw any conclusions about what the future might hold or how concerns about global warming might affect population growth going forward.

“This book is not predictive,” Sasser said in a recent interview with Inside Climate News. “It’s too soon to be able to say, ‘OK, these are going to be the trends. These people are not going to have children, or are going to have fewer children or this many, that many.’ We’re at the beginning of witnessing what could be a significant trend.”

Sasser said that one of the most compelling findings of her research was how survey results showed that women of color were the demographic cohort that reported that they were most likely to have at least one child fewer than what they actually want because of climate change. “No other group in that survey responded that way,” Sasser said.

Those survey results, Sasser said, underscores the prevalence of climate anxiety among communities of color. A Yale study published last year found that Hispanic Americans were five times as likely to experience feelings of climate change anxiety when compared to their white counterparts; Black Americans were twice as likely to have those feelings.

“There is a really large assumption that we don’t experience climate anxiety,” said Sasser, who is African American. “And we do. How could we not? We experience most of the climate impacts first and worst. And the few surveys that have been done around people of color and climate emotions showed that Black and Latinx people feel more worry and more concerned about climate change than other groups.”

Sasser, who also produced a seven-episode podcast as part of the project, said that she hopes her work can help fill what she sees as a void in the public’s awareness of climate anxiety in communities of color.

“Every single thing I was reading just didn’t include us in the discussion at all,” Sasser said. “I found myself in conversations with people who were not people of color and they were saying, ‘Well, I think people of color are just more resilient and don’t feel climate anxiety. And this doesn’t factor into their reproductive lives.’ That’s just simply not true. But how would we know that without the research to tell us? But now I’ve started down that road, and I really, really hope that other researchers will take up the mantle and continue studying these questions in the context of race in the future.”

Sasser recently sat down with Inside Climate News to talk about the book and how she uses her research to show how climate emotions land hardest on marginalized groups, people of color, and low-income groups. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Creative Flight: AURORA Interviewed

An interview with AURORA by Susan Hansen for the Clash Magazine (June 24th, 2024)

An emotional meeting with the Norwegian star...

Alternative pop singer AURORA is a creative and political lead, an artist who shines a bright, much needed light on the world.

A tour de force, Aurora Aksnes’ ambitious new LP is cause to celebrate, even if the state of the world fails to match. The distinguished musician is unafraid to share understanding and insights gained in the past few years, where much time was spent reading, studying and acquiring knowledge.

The Norwegian singer-songwriter is on a composite journey that involves, but is not limited to, absorbing information, examining creativity and political activism. There is a strong conviction and the commitment shown is unwavering.

Creativity first, however. A meeting with the singer is arranged, the location is central London, and Clash meets her on a cloudy afternoon in May. “I bought a notebook in the airport,” she tells us. What initially is at risk of seeming like a mundane snippet of information gains in significance, fairly rapidly.

Her way of observing the clouds is anything but casual, it seems. A painter too, looking at them inspires something else; “I understand why we painted these clouds in the ancient days,” the singer considers. “They were so gorgeous. I was flying through them, looking at them, it was magical. I wrote down what I was seeing, it became a creative flight. It was spiritual.”

One of several core themes, spirituality is a recurring thread in AURORA’s body of work. Then there is a need to make a difference, to help instigate change, have an impact on the outside world, this might explain why she has more to offer than a hit-upon-hit chart artist, which is just how she likes it. Not feeling right about topics such as love, heart aches and revenge is one thing, her agenda is substantial.

“I rant about something that I feel is needed for the world,” she reflects. “It’s hard work to tune in on other things in our daily lives, when there’s so much going wrong outside of us, outside of our families. We’re all brought up to care about our inner circle. All the politics, all these things that we are so scared of outside our inner circle, I write about the outer circles, far away from people in our circles.”

Continuing to discuss, essentially arguing that things in the outer circle are a lot less distant than we think, saying that they actually have a profound effect on us. “I believe that those things far away really affect the things in here, without us being aware of it. I keep that in mind when I write.”

Unsurprisingly, writing is the backbone, and so much has been achieved, racking up billions of streams, world tours, her book, The Gods We Can Touch published in 2022, selling 14,000 copies, the recent vocal contribution on ‘liMOusIne’ with alt icons Bring Me the Horizon, the list goes on.

She is the first to admit that things can become too personal and overwhelming, simply be too open to cope with. A decade can go quickly, she knew it was time to do things differently. “It’s very heart on sleeve,” she admits. “It can seem very personal. This album is the first time in my career, where it’s more personal. I was going through something for a long time, something that pulled me so far down that I actually needed music for myself.”

Fair point. But there is AURORA, the activist and environmental campaigner. A Greta Thunberg of music and art, where a dedicated, compassionate approach is demonstrated, an engagement of long-term commitment. What can seem fairly abstract about her work becomes more and more tangible as our conversation progresses. “It’s easier to call it activism. I just always loved nature, I want people to love her too. We need her and indigenous people are connected to that. To me everything comes back to nature, I’ve been very aware of it for years.”

Honest, direct engagement is priority. Through The Rainforest Alliance contact with some groups was established, including conversations with three female tribe leaders in Colombia, Brazil and Argentina. “They remember a lot of things that we need to remember,” she states with a hint of frustration in her voice. “I cannot believe that we are attacking the very groups, who are protecting what’s left of the world and actually have so much to teach us. That’s a big thing for me.”

She maintains that it makes little sense to “attack the people who are connected to something, it’s like we want the world to forget. Taking the women who are the source of life, taking the children out who are the source of the future, those who are the connection to the past. We are killing everything.”

Viewing herself as a person whose role it is to influence and spread such words, makes arguing the opposite impossible and irrelevant. To her, listening goes beyond anything else, it’s about great listening skills, as is the quality to talk as a friend, as opposed to someone who lectures or patronises. The ability to talk as a friend combined with an urge to learn, educate and let oneself be educated along the way.

The discovery of a passion for speaking about the environment started early on, even if she didn’t associate it with activism or identify it as such back then, she has been active since the age of sixteen. Her statement “art without politics is boring” is a huge part of who she is. The early realisation that she could use her voice, be someone who expresses ideas, opinions and perspectives was a conscious choice, it made her seek out the political path, which makes more sense now than ever before.

There are situations where only a friend can help express the most uncomfortable facts, when things have gone too far. So often a friend can help provide what’s needed, and this is the type of voice AURORA aims to be and the voice she shares with others. It’s how she likes to communicate about important topics.

The connection to nature and earth feeds right into album title ‘What Happened To the Heart?’ If the earth is the basis of everything the world should hold on to, then why is so little care shown, how did we become so far removed from it? “The situation in Palestine shows how willing we are to let unfair things happen, if it’s far away from us. It makes me ask the question now more than ever, what happened to the heart of human kind?”

The prospect of seeing a colourful world, earth and nature turn into “grey nothingness” is less than favourable. The singer insists that “Mother Earth is the same, she doesn’t scream to us with words that we understand. She speaks to us in her own language, and many of us have forgotten that language completely.”

What remains immensely positive is seeing how the urgency of this topic is dealt with so skilfully on the record. A concoction of style, a lofty effort, it doesn’t fail to thrill or educate. With its cathartic core it offers a spectrum of emotion, thought and sound palette. From electro-pop song ‘Some Type of Skin’, there are pulsating techno vibes as heard on ‘Starvation’, the more synth led ‘My Body Is Not Mine’ stands out, as does the more instinctive ‘My Name’. It’s an album of unlimited scope and invention.

It has been an rewarding experience, which according to the singer offered numerous standalone moments. She worked closely with collaborators she knows well (Ane Brun and Matias Tellez), the record also captures fresh openings, new adventures that continue to invigorate. A meeting with a Chinese Pipa player (a string instrument similar to a lute) became the source of an enthralling collaboration. Impressing when she played one of the tracks, the singer just knew the player had to be involved. “I sent her the song. She came back to me the day after, it was amazing. What a woman, I loved the work and kept everything.”

It’s a busy year that continues to get even busier. With festival appearances in the diary, splendid events are in store this summer and include a return to Glastonbury and Roskilde. These are more than just cultural events, they involve engagement with different crowds, they are opportunities to engage with individuals. Each affair is different, people need different things every year, because the world keeps changing.

“I’m excited to see how the youth inspires me, it makes me hopeful for the future. I want to see them be very much alive and well, which I hope and believe will happen. I’m excited to see the energies amongst people now, you get to see crowds and you realise what the audiences are like right now.”

The prospect of a world tour scheduled to begin later this year is massive, one of unmitigated excitement. “I’m very happy that I’m going out there. It’s beautiful that people accept me all over the place.”

It’s hard to imagine a place or a country where AURORA isn’t accepted, given the amount of thought and consideration she puts into everything. It’s such a beautiful thing…

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

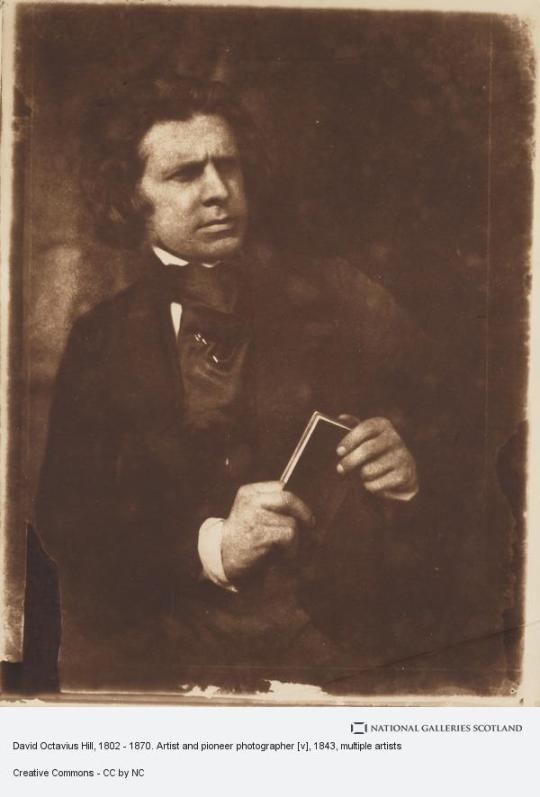

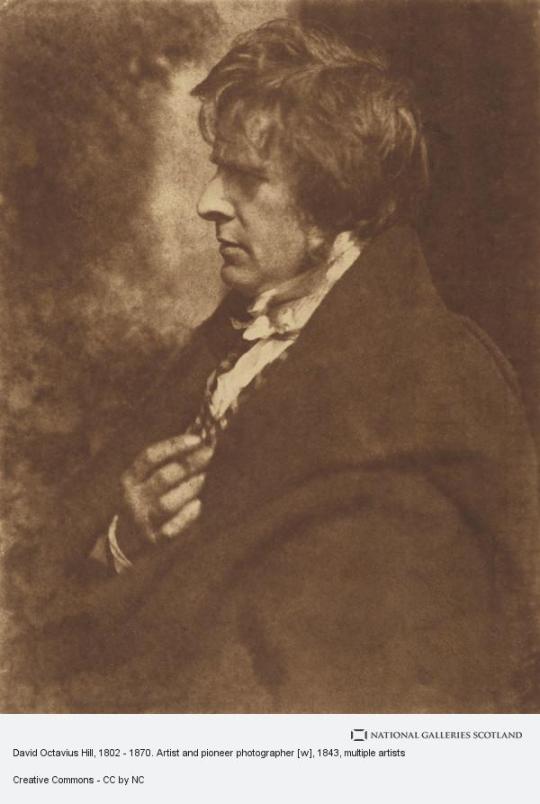

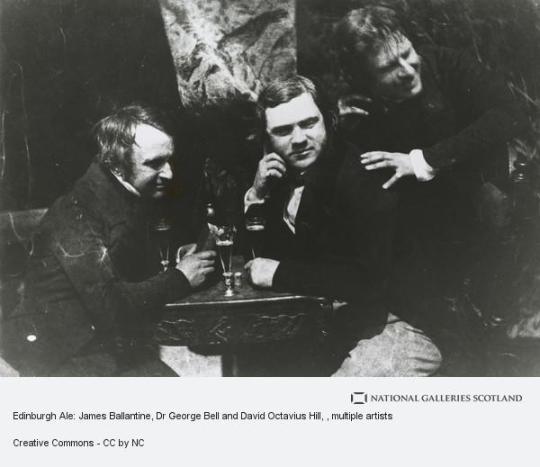

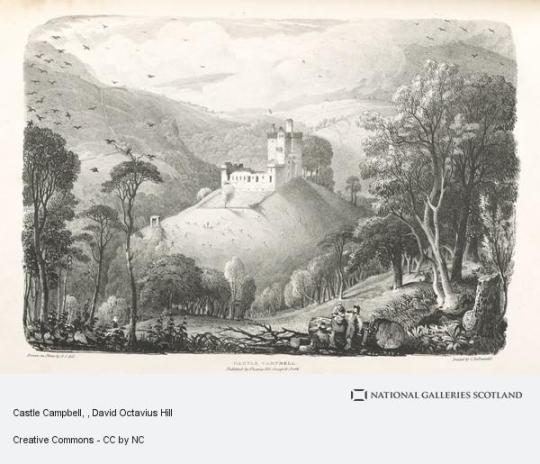

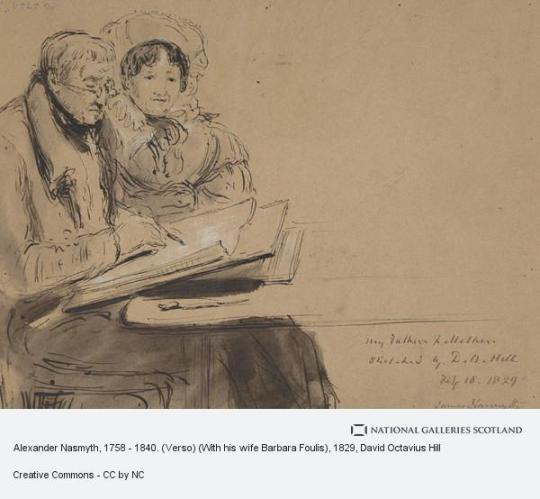

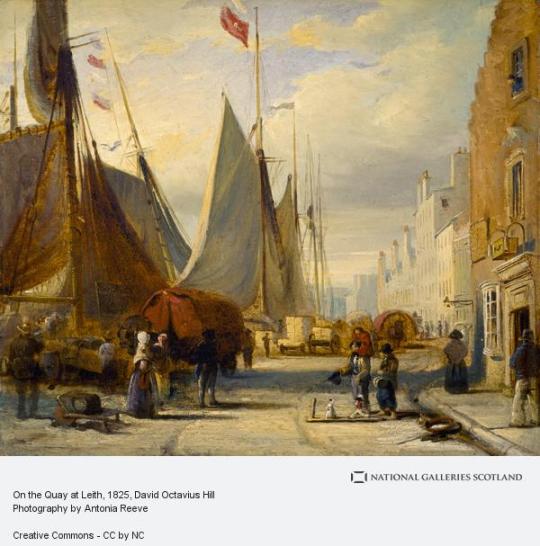

On 17th May 1870 David Octavius Hill, the painter and pioneering Scottish photographer, died.

Hill was one of several pioneering photographers Scotland produced during the 19th century. If you follow my posts you have definitely seen lots of his pictures.

David Octavius Hill was born in Perth, the son of a book publisher. He was educated at Perth Academy and the School of Design in Edinburgh. Hill was an acceptable landscape painter and illustrator (illustrating some novels for Sir Walter Scott). Always involved in the art world, he helped organize the Royal Academy of Scotland and served as secretary from its inception until his death. He was a respected artist in his time, but not one that would be recognized today had he not become involved with Robert Adamson.

David Octavius Hill was present in 1843 at the meeting of the Church of Scotland and witnessed the succession of 457 ministers to reassemble as the Free Church of Scotland. Hill was so moved he pledged to paint a portrait of all 457 ministers together. Sir David Brewster, who had studied for the clergy of the Church of Scotland was also at the meeting. He suggested the use of the Calotype as a sketching tool.

Adamson, who had opened his studio at Rock House just weeks before, entered into a joint venture with Hill to photograph all 457 men of the new Free Church of Scotland. The subjects were posed outside. One set was designed to appear indoors but was actually outdoors with furniture and drapery against a wall of the building.

David Octavius Hill’s 12 ft-wide Disruption Painting, widely thought to be the first time a painter based his work on photographs. The work, which was begun in 1843 and took 23 years to complete, includes everyone involved in signing the agreement that set up the Free Church of Scotland in the 19th century.

Hill and Adamson mainly made Calotype documentary portraits that beautifully speak of their time. They photographed not only the churchmen, but also a variety of subjects: landscapes, architecture, friends and family. Their environmental portraits were among the earliest recorded, utilizing the new medium of photography. They worked together on their project for four and a half years, until Adamson’s early death in 1848.

After Adamson’s premature death at age 27, Hill temporarily abandoned photography and returned to painting. Hill became a member of the Photographic Society of Scotland in 1856 and ran a studio with Alexander McGlashan from 1861 to 1862 publishing Some Contributions Towards the Use of Photography as an Art. Hill sold the remnants of his studio with Adamson in 1869. The property on Calton Hill is now holiday accommodation.

Hill is buried in Dean Cemetery, Edinburgh - one of the finest Victorian cemeteries in Scotland. He is portrayed in a bust sculpted by his second wife, Amelia, who is buried alongside him.

Pics are mainly of Hill, with several pieces of his artwork.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

History and Interpretation (BLOG 6)

Hello and welcome back to my nature blog! This week I have done some thinking on history and how things of the past can be interpreted. When we think of history, we think of the great stories and background behind artifacts that are left over. However, without interpretation, these artifacts that unpack tales of the past would simply be items or really old landscapes. In nature, history allows the information about land, the species it holds, and the people that use it to be conveyed and be used in many ways. History in nature allows local communities to share their past, gives cultural richness, and helps scientific research study the land for important preservation or monitoring rising issues like climate change.

"There is no peculiar merit in ancient things, but there is merit in integrity, and integrity entails the keeping together of the parts of any whole, and if these parts are scattered throughout time, then the maintenance of integrity entails a knowledge, a memory, of ancient things. …. To think, feel or act as though the past is done with, is equivalent to believing that a railway station through which our train has just passed, only existed for as long as our train was in it."

(Edward Hyams, Chapter 7, The Gifts of Interpretation)

In this quote shared as this week's prompt, it seems Edward Hyams dives into the meaning of interpretation in the context of preserving history. He starts by introducing the merit of artifacts, in which he describes what I had mentioned: without a story and someone to debunk the history and an honest background, historical artifacts have little to no worth. The mention of ancient things acknowledges the importance of remembering the history of a place or artifact and how they contribute to the present. This is extremely applicable when talking about nature's history as historical landscapes and ecosystems are all formed by their long evolution over time. These evolutionary processes are important to be understood through interpretation to debunk how species, the climate, and the earth came to be.

The last part of the quote uses a train station analogy to describe the importance of memory. This analogy describes that the past isn't simply something to be discarded or ignored. Just because an event is past, doesn't mean that it wasn't significant to the present or future.

I think Hyams quote also can describe how disregarding historical events that “only existed for as long as our train was in it”, creates struggle in using natural history for conservation. The historical aspects of nature continue to influence the future and we can't forget about the past as there may be great clues to drivers of change currently in ecosystems. For example, cycles of lower temperatures like the ice ages and warmer interglacial periods are all elements of environmental history that have allowed scientists to study the earth's climate and predict the natural waves of temperature versus human impact. Interpretation also keeps historical culture alive and teaches younger generations about having a relationship with nature. An example of this is how Indigenous communities keep their ancestors' history alive for cultural reasons and use stories to convey the importance of certain natural features or landscapes for spirituality (Beck et al., 2018, p.341).

It is extremely important to remember history. This makes interpreters especially important as their role is to keep the integrity of history alive and not forgotten (Beck et al., 2018, p.326). With this, preserving history can be a driver of change for the future having a huge impact on scientific research and cultural practice. Without acknowledging and remembering the past, these "trains" of history will be lost.

Resources

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World (pp. 81–102). Sagamore Publishing LLC. https://sagamore.vitalsource.com/books/9781571678669

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jade S. Sasser is an associate professor in the Department of Gender & Sexuality Studies at UC Riverside. Her research explores the relationships between reproductive justice, women’s health and climate change, and she’s the host of the podcast “Climate Anxiety and the Kid Question.” The following excerpt is from her newest book, “Climate Anxiety and the Kid Question: Deciding Whether to Have Children in an Uncertain Future,” which was published earlier this year.

Full text under cut.

The kid question. It comes up over and over again in the form of family questions and expectations. It arises in conversations with peers, partners and new dates. It appears in the quiet times, sitting in the spaces where our wildest hopes and deepest fears collide.

American society feels more socially and politically polarized than ever. Is it right to bring another person into that?

In 2021 and 2022, I conducted a series of interviews on this topic with millennials and members of Generation Z, all of them people of color. Some grew up in low-income families and neighborhoods while others were from the middle- or upper-middle class. Some of them identify as queer, or their close family members and friends do, which shapes their sensitivity to discrimination against gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people.

These interviewees have more climate change knowledge than most people do. All of them are college-educated; most of them either grew up or have lived for some time in Southern California; and most have taken environmental studies classes, either as undergrads or in graduate school.

Their experiences as members of marginalized groups have shaped their experiences with climate emotions like anxiety, fear, and trauma — as well as hope and optimism. Paying closer attention to those emotions and mental health in communities of color, including how they shape reproductive plans, will become an increasingly important component of climate justice in the United States.

Bobby

Bobby, 22, considers himself an environmentalist. He recently graduated from college in Southern California with a degree in sustainability studies. His family is Guatemalan American.

Bobby is both confident that he will become a parent one day and also certain that he won’t bring his own biological kids into the world. His thoughts about the environment, the future, and parenting come into sharp relief through his current job at a restaurant, where he is unhappily employed. “There’s so much being wasted that could be returned to the earth.”

He connects these waste issues to carbon emissions and how he feels about having children. For Bobby, this is an ethical issue, a reason why he should not have biological children:

Students discard food into a bin as part of a lunch waste composting program at an elementary school. (Associated Press)

“This is why I’m leaning more toward a foster kid, and maybe eventually adopting them. Because it wasn’t my choice to have that kid, but I can help guide them to have a better life. … The environment is really the deciding factor for me.”

Although he always wanted to have children, his thoughts about fostering arose from taking environmental studies classes. “Going into college was the first time I was exposed to this information firsthand, and I realized for the first time, it’s not all rainbows and sunshine. I had never learned before … about things like food waste and carbon emissions. And that’s when the gears started turning in my head about the future and what I wanted to do.”

Victoria

Victoria is the same age as Bobby; she graduated from the same university and is also from an immigrant family, though hers is from Ghana. In Victoria’s house there were four siblings and half a dozen cousins who were always around. As a result, Victoria really cherished the closeness and security of a large family.

“I guess in the future, I would love to have children,” she says. “I’d really like to have a big family. I grew up in a big family, so it’s nice.”

Victoria is interested in perhaps adopting or fostering, and she also connects the desire for this to her undergraduate education in environmental topics.

Protesters hold a “silent march” against racial inequality and police brutality that was organized by Black Lives Matter Seattle-King County in June 2020. (Associated Press)

Victoria’s concerns about biological children are multifaceted: She worries about the future of healthcare access, wealth inequality, and whether her children would receive a low-quality education or be racially tracked in public schools. Ultimately it comes back to how racial inequality interacts with other social challenges to heighten her own sense of vulnerability and that of her potential future children.

“If I have children, they will be Black children,” she says. “It isn’t self-hatred. I love being Black, but the things I’ve gone through I wouldn’t wish on other children.”

This is a frequent topic of conversation among Victoria and her friends. They talk about whether they want to have children in the future. Most of them do not.

That feeling of being traumatized by an awareness of ongoing racial inequality shaped the perspectives of a group of Black women I spoke to. They were different ages, from their 20s to their late 30s, and they ranged from just starting out to having established careers. However, each perceived herself, and the prospect of becoming a mother, through the lens of vulnerability.

Rosalind

Rosalind, 38, is a Black woman of Caribbean origin living in Southern California. She has a graduate degree, a job as a scientific researcher, and is settled in a community she likes. Nevertheless, thoughts of the future are a heavy, ever-present burden. When I ask if there is one issue that feels like the primary reason for not having kids, she answers decisively: racism.

“With all of the anti-Black violence, and the police violence against us, it just seems so unsafe. And I see so many of my friends who do have children that are constantly stressed because of this, especially the ones who have teenage boys who are taller than average. They send their kids out there and then just spend their time worrying about whether their child is going to be targeted or harassed in some way, or potentially killed. I just don’t think I have the disposition to put up with that kind of stress.”

Melanie

Melanie, a 26-year-old Native American woman, was raised on the Navajo reservation and in Southern California. She idealizes having a big, happy family, but there are aspects of the world that give her pause, so she struggles with whether it’s morally OK to have children.

Drought last year took a toll on Joshua trees at Joshua Tree National Park. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Melanie’s feelings about climate change include a general sense of powerlessness and lack of control over other people’s actions, which directly translates into her fears about parenthood: “With climate change, we’re the driving force of things breaking down, but then also, the planet’s going to do what the planet’s going to do. … So … it almost feels, like, kind of shameful to want to have children.”

Juliana

Juliana, a 23-year-old Mexican American woman, is strongly aware of negative peer pressure from friends. She recently graduated from art school, and her friend circle is mainly composed of queer and transgender, anti-establishment artists. Most of them have no intention of having children of their own, which seeps into conversations with Juliana.

Her friends cite environmental and mental health concerns. Their anxiety tells them that they can’t properly take care of themselves, much less a child. They also struggle, as trans and nonbinary people, with the issues of access to fertility centers and the need to use reproductive technologies that feel out of reach.

The Borel fire devastated Havilah, a historic mining town in Kern County, in late July. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

As a dark-skinned Mexican woman, she regularly experienced racism growing up in Southern California— and given that her husband is white, any child she might birth would be biracial, which raises questions about whether and how they would navigate the world differently than she has. But Juliana is an optimist, and she does plan to have one child.

Elena

I spoke to several young women who are addressing the kid question with their dates, potential partners, and long-term boyfriends. Elena, 22, is one of the most certain people I’ve met: She is not having children.

She’s from a Salvadoran immigrant family in which she is one of four children, while her mother was one of 12. Her certainty that stems from both life experiences and climate fears:

“Me being interested in environmental policy cemented my decision to not have kids, but I do have some personal things that I’ve gone through in life that I wouldn’t want my kids going through, like not having a dad. So I feel like it’s best if I just focus on myself and take care of my mom. ... I can also spend my time and energy focusing on someone that’s already here.”

Elena brings this conversation up on every first date with any new guy she sees. Given that most of them expect to have families in the future, Elena feels strongly that she does not want a relationship. This has been discouraging for her, but her mind is made up.

Like some of the other people I interviewed, Elena’s feelings about climate change were sparked by environmental studies classes. She says, “[I] started feeling like having kids is definitely not a sustainable thing to do. … I don’t want them to grow up and have to leave their home because of sea level rise. Or be worried because of really weird weather patterns.

A pump station sits idle near homes in Arvin, Calif., where toxic fumes from a nearby well made residents sick and forced evacuations in November 2019. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

Veronica

Elena’s close friend Veronica, a 22-year-old from Los Angeles, manages the cultural expectations of a large, immigrant family from Guatemala. “Because of my Hispanic background people are always like, when are you gonna have children, of course you’re having children. It is what it is, right? But now that I’m an adult, I think about it differently. Would my child have a good quality of life? Will they be able to survive?”

She wants to have a child, “but I also want to be mindful of that child. Because it’s not just about having it, it’s about raising it. And being able to sustain it as well.”

For Veronica the everyday environmental concerns link directly to the larger issues shaping climate change: power, who has it, and who doesn’t. Though seemingly distant, intergenerational power imbalances — and older generations’ legacies of generating the emissions that have caused climate change — make her feel that it is unfair for people her age to have to ask the kid question.

She says: “I just think that people in power, whether they believe in climate change or not, it’s not beneficial for them to really do something about it. Because they’re older, it’s not going to affect them the way it affects us. … They have so much money and power it doesn’t affect them the same way. They can buy protection from what the rest of us are going to have to deal with.”

Although these interviews focused primarily on the challenges young people face as they approach reproductive questions, many of them still wanted families of their own. For those who were certain about having children, the reasons were emotional: love, joy, happiness, and hope.

Bobby was clear that he doesn’t plan on having biological children, but he was happy about the thought of fostering in the future and was particularly excited at the thought of his sister having kids.

“I would love to be an uncle,” he said. “Just seeing the next generation, the reason why I’ve been more optimistic about having a foster child of my own, is about being able to see them grow.”

This 2019 aerial photo provided by ConocoPhillips shows an exploratory drilling camp at the proposed site of the Willow oil project on Alaska’s North Slope. (Associated Press)

“I want to create a space where kids have loving, supportive parents. My parents aren’t perfect, but I know that I grew up in a loving home where they would do anything for my success and protection, and I want to create that for someone else.”

Her sentiments were echoed by Melanie, whose experience living in a racially and gender-diverse family inspires her to want to recreate the same.

She said: “When I look within my own family, we’re very diverse. We’re Black, we’re white, we’re Native American. We’re straight, we’re queer, we’re nonbinary. And we still have compassion for each other and that kind of spills over into compassion for other people that we don’t know. And I think, like, I don’t want to quit. I don’t want to let the bad things dictate how I make my decisions

“The idea of bringing someone into this world and growing them with compassion and love, and making sure they grow up knowing to stand up for other people and stand up for what’s right, that’s a little glimmer of hope.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

This article tells me that either (a) the law clerks who worked for the US Supreme Court justices when they were developing their new case law about the Clean Air Act did a lousy job on researching Congressional intention or (b) the law clerks did their jobs but the justices (primarily Alito, Gorsuch, Roberts, Kavanaugh and Thomas) decided to ignore the clerk's work and memos. Most likely a combination of the two.

Excerpt from this story from Inside Climate News:

Among the many obstacles to enacting federal limits on climate pollution, none has been more daunting than the Supreme Court. That is where the Obama administration’s efforts to regulate power plant emissions met their demise and where the Biden administration’s attempts will no doubt land.

A forthcoming study seeks to inform how courts consider challenges to these regulations by establishing once and for all that the lawmakers who shaped the Clean Air Act in 1970 knew scientists considered carbon dioxide an air pollutant, and that these elected officials were intent on limiting its emissions.

The research, expected to be published next week in the journal Ecology Law Quarterly, delves deep into congressional archives to uncover what it calls a “wide-ranging and largely forgotten conversation between leading scientists, high-level administrators at federal agencies, members of Congress” and senior staff under Presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. That conversation detailed what had become the widely accepted science showing that carbon dioxide pollution from fossil fuels was accumulating in the atmosphere and would eventually warm the global climate.

The findings could have important implications in light of a legal doctrine the Supreme Court established when it struck down the Obama administration’s power plant rules, said Naomi Oreskes, a history of science professor at Harvard University and the study’s lead author. That so-called “major questions” doctrine asserted that when courts hear challenges to regulations with broad economic and political implications, they ought to consider lawmakers’ original intent and the broader context in which legislation was passed.

“The Supreme Court has implied that there’s no way that the Clean Air Act could really have been intended to apply to carbon dioxide because Congress just didn’t really know about this issue at that time,” Oreskes said. “We think that our evidence shows that that is false.”

The work began in 2013 after Oreskes arrived at Harvard, she said, when a call from a colleague prompted the question of what Congress knew about climate science in the 1960s as it was developing Clean Air Act legislation. She had already co-authored the book Merchants of Doubt, about the efforts of industry-funded scientists to cast doubt about the risks of tobacco and global warming, and was familiar with the work of scientists studying climate change in the 1950s. “What I didn’t know,” she said, “was how much they had communicated that, particularly to Congress.”

Oreskes hired a researcher to start looking and what they both found surprised her. The evidence they uncovered includes articles cataloged by the staff of the act’s chief architect, proceedings of scientific conferences attended by members of Congress and correspondence with constituents and scientific advisers to Johnson and Nixon. The material included documents pertaining not only to environmental champions but also other prominent members of Congress.

“These were people really at the center of power,” Oreskes said.

When Sen. Edmund Muskie, a Maine Democrat, introduced the Clean Air Act of 1970, he warned his colleagues that unchecked air pollution would continue to “threaten irreversible atmospheric and climatic changes.” The new research shows that his staff had collected reports establishing the science behind his statement. He and other senators had attended a 1966 conference featuring discussion of carbon dioxide as a pollutant. At that conference, Wisconsin Sen. Gaylord Nelson warned about carbon dioxide pollution from fossil fuel combustion, which he said “is believed to have drastic effects on climate.”

The paper also cites a 1969 letter to Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington from a constituent who had watched the poet Allen Ginsberg warning of melting polar ice caps and widespread global flooding on the Merv Griffin Show. The constituent was skeptical of the message, called Ginsberg “one of America’s premier kooks” and sought a correction of the record from the senator: “After all, quite a few million people watch this show, people of widely varying degrees of intelligence, and the possibility of this sort of charge—even from an Allen Ginsberg—being accepted even in part, is dangerous.”

Jackson then sent the letter to presidential science advisor Lee DuBridge, who responded by detailing the latest science, which showed that while there was uncertainty about the effects of increased levels of carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas effect was real and a product of fossil fuel combustion.

“We just felt that strengthens the argument that this is not some little siloed scientific thing,” Oreskes said of the episode. “It’s not just a few geeky experts.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I figure the next Satanic Panic literature I'll look at will be Wicca: Satan's Little White Lie. It was written by William "Bill" Schnoebelen, a guy who claimed to have been involved not only in Wicca, but also Freemasonry and Mormonism, and discovered that each one of them was Satanic. The dude claims he was involved with the Illuminati, which was of course Satanic.

Now of course, if you're active in witchcraft and neopagan discourse, you'll know that Wicca has been subjected to lot of criticism - particularly regarding its members being culturally appropriative and overstepping boundaries by claiming that all gods and goddesses are aspects of Wicca's Lord and Lady. But I think you'd also agree that it's not Satanic, and that claiming that it's part of a giant Satanic conspiracy is just... silly.

The book was published by Chick Publications, as in Jack Chick, as in Chick tracts. Jack Chick, for the unaware, spent his life creating small comics meant to lead others to Jesus. They were full of conspiracy theories and general hatred toward anyone who wasn't an Evangelical. Though it seems that as of late, Chick Publications (no longer run by Jack Chick, who is deceased) has cut ties with him, because Schnoebelen has been getting into flat earth and defending Christian use of Kabbalah.

So. Yeah.

On the first page, Schnoebelen describes Wicca as "one of the more seductive deceptions that Satan has come up with." Now Bill, I know Gerald Gardner was... not great, but I don't think he was Satan.

He claims:

It claims to be a “back to nature” religion which worships the sky and earth, and thus has attracted many adherents among those sympathetic to environmental and ecology issues. Yet, for all its charm and nostalgic fantasy, Wicca drew me into the deepest quagmire of satanic evil imaginable.

Dude... if you decided to jump ship from Wicca to Satanism (or at least, Satanism According To Evangelical Conspiracy Theorists), that's on you. If you were so greedy for power that you went as far as you claim, that's your fault.

Um. What:

The actual spiritual difference between Wicca and satanism might best be illustrated this way: Practicing Wicca is like having a hand-grenade blow up in your face, in terms of the spiritual impact. Practicing satanism is like having an neutron bomb detonate in your face. The difference is there and discernable, but it is still an utter disaster for you, either way.

Schnoebelen points out that Wicca was created in the mid-20th century, which I mean, fair enough. But then he tries to assert that Wicca Is Bad because Etymology and also the Dictionary and also there's arguments over what a witch is among neopagans, and like. It's just absurd because it's not like Christianity is free of questionable historical claims or infighting.

And then he claims:

In my own personal development as a witch, and the development of almost all our colleagues, I found that after about five or six years it was necessary to begin pursuing the study of the “Higher Wisdom” of Satan in order to keep growing. Magick is like a drug. You keep needing more in order to stay at a level at which you feel fulfilled. There is no end to it! If you’ve stayed a Wiccan or “white” witch for a long time, it’s only because you don’t have enough of the Promethean itch to grow. OR it may be that you have many Christian friends or loved ones praying for you.

Did you ever think of that?

Bill. My dude. The problem is that you are a power-hungry fuck, who apparently lacks any ability to recognize when a spiritual claim or worldview is just kinda ridiculous or fucked up, and drop it like the crap it is. I'm guessing that's why you're getting into Flat Earth these days. You just don't know where to quit, and you're projecting this onto everybody else.

45 notes

·

View notes

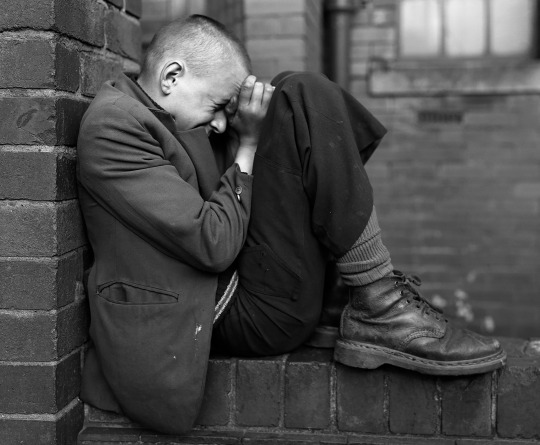

Photo

“I don't pretend to be an intellectual or a philosopher. I just look.”--Josef Koudelka

Chris Killip was one of Britain’s most important documentary photographers, and yet, he has been under appreciated outside of the UK. His contributions to photography and to his students at Harvard, where he taught from 1991-2017 as Professor of Visual and Environmental Studies, have never gained the wider recognition he deserved, until now.

Coinciding with a major retrospective at The Photographer’s Gallery in London, Thames & Hudson has recently published Chris Killip (1946-2020), offering the most comprehensive collection of Killip’s work to date. What we discover poring through the monograph is an artist at home in the communities he photographed. Chris Killip, himself the son of pub managers from the Isle of Man, lived small town life and the quotidian. He also understood class. His sympathies and work with the historic Miner’s Strike in the Thatcher years make it clear. His 1988 landmark book In Flagrante showed us potently how class impacts communities. Thus, his superlative images come through an intimacy of understanding, an acknowledgement of class, and a love for people.

Killip left school at age 16, and probably never imagined he would one day become a tenured Professor at Harvard, or spend the remainder of his life actively engaged as a working photographer. With his passing in October 2020, this new collection of his work is a fitting tribute to his legacy, the people he photographed and the images he left us. Like his old friend Josef Koudelka, Killip wants us “to look” and to see. --Lane Nevares

#chris killip#photography#Thames & Hudson#the photographers gallery#english photographers#working class#england

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Links Roundup

The interwebs had so many interesting things to read this week! Here’s a links roundup of a few.

Hurricanes Becoming So Strong That New Category Needed, Study Says

Where else would we start but at The Guardian, with an article about how much bigger and more intense the biggest, most intense hurricanes (and other cyclones) are becoming. You might call it doom and gloom, but the climate–adjacent scientist in me finds some weird satisfaction in seeing that, yes, retaining extra energy within the climate system because we’ve overinsulated it by adding extra greenhouse gas to the atmosphere is having spectacular effects. Honestly, we need to get our act together about reducing our greenhouse gas emissions to net zero ASAP (40 years ago would have been better).

Should More British Homes Be Built Using Straw?

The BBC website had an interesting article about adding straw–packed panels to the exteriors of buildings (generally as they’re being newly constructed, given the size constraints) to improve their insulation. The straw is packed so tight that it’s fire resistant but not so tight that it doesn’t trap air inside the stuffing, thus serving effectively as insulation, vastly reducing how much you need to heat or cool a building. At the moment, here in Germany, they use thick slabs of Styrofoam, which release horrendously toxic fumes if the building catches on fire. Straw sounds like an interesting, non–toxic, sustainable alternative, especially if you consider how much waste straw is generated every time crops like wheat, rye, and even oilseed rape (Canola) are harvested. The main catch is that production of the panels would need to be scaled up quickly enough to matter in our fight against further climate change by reducing the amount of energy needed to keep buildings at a comfortable temperature.

A US Engineer Had a Shocking Plan to Improve the Climate – Burn All Coal on Earth

This article, also on the BBC website, is about the opposite of trying to save energy, and it’s a quick history of our attitude toward anthropogenic global warming. Turns out, the sort of people who don’t want to admit it’s real today were the sort of people who used to think it would be great to burn all the fossil fuels to take the edge of the chillier aspects of climate. Bonkers. These were probably also the people who liked to think that adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere would totally boost plant growth, and therefore crop yields, on a major scale. Also bonkers.

Can Slowing Down Save the Planet?

The New Yorker published an interesting review of the book Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto, in which the Marxist philosopher Kohei Saito lays out the case for “degrowth communism”. He argues that green capitalism won’t be enough to save the planet—and us. It just looks good from a certain vantage point right now because it pushes the environmental and social costs of resource extraction and good production into the Global South. This allows consumers in the Global North to remain blissfully ignorant of the damage they’re (we’re) doing with their (our) unsustainable lifestyles and obsession with continuous economic growth.

How Craftivism Is Powering 'Gentle Protest' for Climate

Back to the BBC for a fun article about “craftivism”. I’d never thought about this before, but it’s actually a thing that has touched almost all of our lives, even if we’re all thumbs with a terrible sense of aesthetics. Who hasn’t walked past a street pole or statue encased in guerilla knitwear? Even I knitted a pussyhat to wear to an anti–Trump demo on inauguration day (although I didn’t knit a pink one because I would rather die than wear pink, except utterly ironically). And—although perhaps I’m revealing my age here—who hasn’t seen at least a few squares of an AIDS quilt? On the whole, I think it’s good that people put their crafting skills to good political use. Otherwise—and this may be an unpopular opinion—our need to continually craft is just an extension of our unsustainable overproduction and overconsumption of goods. Everyone I know who knits (including myself) has already made more sweaters, hats, scarves, socks, and baby blankets than they can wear out in a lifetime and yet we keep on knitting.

A Big Idea for Small Farms: How to Link Agriculture, Nutrition and Public Health

NPR had a great article that fits with our current podcast episode on regenerative farming with Solarpunk Farms. A literally existential crisis that we’re currently failing to tackle is that of how we grow food. The whole agricultural system is messed up from top to bottom. Food’s too cheap (and many people aren’t paid enough to be able to pay the real price of food, which is a whole other enormous issue). Because of this, farmers are pissed off and dependent upon subsidies from the governments they’d increasingly like to overthrow. Meanwhile, they’re frantically farming so intensively to try to bring in enough income that they’re destroying what’s left of our natural world. Their farming practices are degrading soils and polluting our air and waterways with fertilizers and petrochemical pesticides, destroying adjacent ecosystems and driving numerous species of plants and animals (including insects and other key invertebrates) to extinction. Related to this, we’re eating too much of the wrong stuff (meat, highly processed foods) and not enough of the rights stuff (fruits, nuts, seeds, and vegetables). Enter the solution: nutrition incentive programs that make it possible for people with lower incomes to obtain fruits and vegetables from smaller, regenerative farms. It’s a win for public health, a win for fruit and vegetable farming, which isn’t subsidized the way corn, soy, and wheat farming is, and it’s a win for the small percentage of food producers fighting not to be swallowed up by the Big Food companies who’ve all but monopolized the production of the food we eat.

Tractor Chaos, Neo-Nazis and a Flatlining Economy: Why Has Germany Lost the Plot?

Having started at The Guardian, we’ll bring things full circle and end there with a look at the situation here in Germany. Lots of us are increasingly concerned about the rise of the far right and... perhaps still flying under a lot of people’s radar... that angry farmers are going to end up ushering in the Fourth Reich. The op–ed says it all, while trying to maintain a sense of humor about it. As with so much else in the news these days, it makes you want to scream that we have more important things to be doing right now—that matter for the survival of billions of people—than withdraw into the hermit crab shell of authoritarianism. Their easy answers and general denial of the problems that need solving will only make life even more miserable for most people and allow all our existential problems, like widening wealth inequality, environmental devastation, and increasingly catastrophic climate change, to escalate even further before we begin dealing with them.

Sci_Burst

To end on a happier note, here’s a shout out about Sci_Burst, a fun podcast from Australia about “science, popular culture, and entertainment”. They even have an episode on solarpunk. If you’re all caught up with us (including with all the extras on our YouTube channel), our feelings won’t be hurt if you give them a listen. 😊

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adam Sills’s well-written and beautifully produced Against the Map is in some ways a strange book to review [...] [from the disciplinary perspective of environmental studies]. Sills shows little interest in environmental history or ecocriticism, even in the “ecology without nature” mode [...]. His basic argument is that cartography, because of print capitalism, seeped into all sorts of facets of life on the British Isles during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It became something that playwrights, novelists, and creative nonfiction types, like Samuel Johnson, developed spaces of resistance to in their publications. Sills highlights the political nature and problematic historical genealogies of maps, an argument that has broader implications for [contemporary] environmental historians who use maps to convey [relatively more “objective” and/or “scientific” information] [...].

Sills begins by accepting the idea, derived from Ben Anderson’s comparative work, that “the history of the map and the history of the modern nation state are inextricably bound up with each other” (p. 1). He then cites two of the key analysts of this in relation to Britain: Richard Helgerson on the literary nationalism of the English Renaissance and John Brewer on the fiscal-military state of the eighteenth century, with its army of surveyors and excise tax collectors. In this historiography, the “surveyor emerges as an authorial figure,” key to the making of the modern state as distinct from traditional dynastic and ecclesiastical authority (p. 3). Combined with cheap printing, the result was what Mary Pedley has called a “democratization of the map” (p. 4). [...]

---

For John Bunyan, the “neighborhood” became a site of resistance (as it is for Denis Wood in his 2010 Everything Sings: Maps for a Narrative Atlas). [...]

For Aphra Behn, [...] the theater and “built environment” of the “fragmented, chameleonlike ... scenic stage” had the ability to challenge coherent representations of the Atlantic empire produced by maps like those of world atlas publisher and road mapper John Ogilby (p. 65).

From Dublin, Jonathan Swift directly satirized the cartographic and statistical impulses of the likes of William Petty, Henry Pratt, and Herman Moll, who all helped visualize London’s colonial relationship with Ireland [...].

From London, Daniel Defoe questioned efforts to define what precisely makes a market or market town through maps and travel itineraries, pointing toward the entropic aspects of the market (“its inherent instabilities and elusive nature”) that challenged and escaped efforts to stabilize such spaces through representations in print (p. 163).

Johnson’s travels to Scotland redefined surveying, resisting the model put forward by the fiscal-military state in the aftermath of the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745.

---

The final chapter and conclusion, “The Neighborhood Revisited,” looks at Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (1814), a classic novel of the artificial environment of the estate garden. By the early nineteenth century, neighborhoods were more like gated communities and symptomatic of Burkean conservatism and nostalgia. But in Austen’s hands, their structures of affect also suggest the limits of the controversial map- and data-centric literary methodologies [...] and perhaps more broadly the digital humanities. “The principle of spatial difference and differentiation, the heterotopic conceit, always remains a formal possibility, not only at the margins of the empire but at its very center as well,... a possibility that the map cannot acknowledge or register in any fashion” (p. 234). For Sills, this is true of eighteenth-century mapping as well as the fashion for “graphs, maps, and trees” in the early twenty-first century.

---

Sills’s basic argument, that a certain canonical strain of English literature - from Bunyan to Austen - positioned itself “against the map,” seems quite solid. He makes this point most directly by appealing to the work of Mary Poovey on the modern “fact,” with the map as “a rhetorical mode ... that serves to legitimate private and state interests by displacing and, ultimately, effacing the political, religious, and economic impact of those interests” (p. 91).