#gruffydd ap rhys

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nest of Deheubarth and Gwenllian ferch Gruffudd ap Cynan

Lemme talk about two fabulous Welsh women who deserve to be yelled about more because they occupy fascinating roles in Welsh history and also they were SISTERS-IN-LAW. If they'd met I do think they would have a very Morgan Le Fay and Guinevere relationship (without the casual murder? Hmm.)

Anyways, Nest of Deheubarth (Also known as Nesta, or Annest, was the 'Helen of Wales,' which, seriously, we gotta stop appellating Helen of Troy to women whose beauty starts wars. It is a handy metric, but, like, neither were THEIR FAULT.) daughter of Rhys ap Tewdwr - yes, as in the Tudors. They have links to them through Rhys' son, Gruffudd - and Gwladys ferch Rhiwallon ap Cynfyn of Powys. (Said it before will say it again intermarriage between Gwynedd, Deheubarth, and Powys is super common.)

(This is Nest with Henry II. Note how they both have crowns on in bed. Like, I know it's to telegraph they're royal but like imagine them kissing. *clang* sorry, my crown keeps slipping off my head *clang* sŵs.)

Anyways, born in about 1085 (give or take) Nest was Princess of Deheubarth. Normally, this would entail being married to another Welsh royal family - and possibly your cousin, yeesh - but, sadly (or happily depending on your view) this was not to be the case for Nest.

Her father, Rhys, was King of Deheubarth until 1093. Deheubarth had largely been left untouched by the Normans thanks to a peacy treaty brokered by Rhys and thr King of England William Rufus but, sadly, Henry I soon put a stop to that after his brother, William Rufus' death. (For those wondering he got shot in an arrow in the New Forest. Some say Henry did it so he could assume the throne)

Rhys perished in battle at Breacon against Bernard de Neufmarche's forces, with him being beheaded at Penrhys in Rhondda Cynon Taf (Penrhys literally means Rhys' head.) Brut Y Tywysogion records: 'Rhys ap Tewdwr, king of Deheubarth, was slain by the Frenchmen who were inhabiting Brycheiniog, and with him fell the kingdom of the Britons' His death allowed the Normans to take Deheubarth unopposed and they wouldn't even begin to break their yoke until Gwenllian.

Anyways, Nest, her mother, her half-brothers, and her sisters were captured by the Normans once they'd murdered Rhys and were sent to either prison or the Anglo-Norman court to live as hostages to prevent any further rebellions. Meanwhile, Nest's younger brother, Gruffydd, was spirited away to Ireland (more about him later!).

But even there Nest wouldn't exactly be allowed to fly under the radar. She grew into a beauty - don't all captured foreign historical women, honestly? Like, grim - and caught the eye of Henry I, becoming his mistress, bearing him a son -- also called Henry* as it goes. See, having the same name as your dad is just a Welsh trait, ngl.

Soon after, in around about 1102 but possibly later, and once Henry I had dealt with some rebellions from his subjects (namely Robert de Bellême) he married Nest off to Gerald FitzWalter who was the constable of Pembroke Castle, purely cuz he sided with him. Nest's feelings are not recorded in history, but I'd imagine she was both delighted to be going home to Wales and distraught that she was married to a Norman lord who'd had a hand in subjugating her country.

Either way, with her marriage to Gerald she was both seen as a Norman - as were her sons, collectively known as the Geraldines, famous for subjugating Ireland, and nephew, Gerald of Wales - and as a figurehead for Welsh resistance.

And it's this that gives her the claim for being the Helen of Wales. Now, various reports of how shit went down are given but the facts are thus: in either 1106 or 1109 her cousin, Owain ap Cadwgan, Prince of Powys, kidnapped Nest and her sons. Gerald escaped either by escaping down the latrine (smelly toilet pit) or fighting his way out. Some say this was during an Eisteddfod given by Owain's dad, some say this was at Cilgerran Castle, a Norman castle that Gerald had built. Idk. Either way, she was once again, a hostage. Kari L. Maude says Owain was 'overcome by her [Nest's] charm,' but, equally, he could've been making a point of raiding the castle to spite a Norman and carrying off his cousin to try and force the Welsh to rebel. 'What is clear,' Maund further writes, 'Is that Owain was engaged on a consistent campaign against the Norman colonies in Wales.'

(OR, Nest had engineered the whole affair deliberately cuz she and Owain were lovers. There is talk that Owain was gonna be betrothed to Nest before everything that occurred but that is spurious speculation so idk. Whatever floats your boat, I guess.)

ANYWAYS. The earliest account of this shenaniganery we have is by Caradoc of Llancarfan which relates that: 'At the instigation of the Devil, he [Owain] was moved by passion and love for the woman, and with a small company with him...he made for the castle by night.' Once he'd done this he took Nest and her kids to a hunting lodge by the Eglwyseg Rocks north of Llangollen, presumably to live in what he thought was relative peace.

Hoo boi, he was WRONG. The abduction of Nest, done with her consent or not, aroused the wrath of both the Normans (for obvious reasons those HEIRS ARE NORMAN-BLOODED GIVE THE SONS BACK) and the Welsh (I guess because this was seen as a Welshman abducting a Princess of Deheubarth? Unsure.) Either way, the Normans bribed Owain's Welsh enemies to attack him which they did. (Pls remember that the Powysians hated Deheubarthians and Gwyddelians hated them both ect, etc.)

Owain's dad throughout all of this desperately tried to persuade his son to give Nest back ('Pls, pls, pls, Owain, your himbo arse has gotten us into SO MUCH SHIT!' I can imagine him saying. This does, however, ignore the fact that Cadwgan himself was sanctioning his son's raids.) With Owain just brushing him off. Nest, once again, saves a man's life and entreats Owain: 'If you would have me stay with you and be faithful to you, then send my children home to their father.'

Owain did so, but before long, both he and his dad were then obliged to seek safety in Ireland lest further attacks were made on them. Nest was also returned to her husband. Whether willingly or not idk but yeah.

Now, by this time (1112), her brother Gruffudd had returned from his sojourn in Ireland and was trying to drum up support to get Deheubarth back under his rule, particularly with the aid of the King of Gwynedd, Gruffudd ap Cynan, who would ultimately become Gruffydd's father-in-law when Gruffydd married his daughter, Gwenllian 🥳🥳🥳. It's interesting to imagine that Nest was giving her brother a hand in this but we have no textual support to say so. Tbf, perhaps she did and she was just so good at doing it that it's just remained undetected for hundreds of years. 🤷🏻♀️

War broke out between Gruffydd and the Normans. Gruffydd, expecting to have his inheritance given to him and no liking to hear the word 'NO' yelled at him Henry I with a fuckin megaphone, fuckin burned Carmarthen and then destroyed Arberth in 1115, alongside 'members of the younger nobility'. (As he should, in all honesty.)

Owain ap Cadwgan who had, by this time, tootled back from Ireland, been PARDONED BY THE KING (Henry I, that is.), and became prince of Powys after his dad was ASSASSINATED (Assassin's Creed: Powys edition when?) Obliged by Henry I to rendezvous with a Norman force to proceed against Gruffydd, Owain found himself meeting up with Nest's husband, Gerald.

( Sjdjxjxjddkxj Could not make that up. Sounds like a Hollyoaks episode.)

Gerald, wanting to fuckin Murk Owain for what he did to his kids and wife, proceeded to Murk Owain. I do honestly feel like Gerald also thought 'If he kills my bro-in-law my wife will fuckin KILL ME.' so I respect this for being In Fear of his wife.

Gerald himself died in 1135, yet Nest delightfully, was still going. She married Robert FitzStephen, having another kid to the five she'd already had with Gerald, including the mother of my arch-nemesis Gerald of Wales, Angharad.

It isn't known when she died but it's estimated that it was about 1135/1136, thus allowing her to see the start of her brother and sister-in-law's rebellion that would eventually put the land that the Normans had so cruelly taken from the back into the hands of their family.

A note:

*Henry would later be killed in Ynys Môn during a battle against Nest's brother-in-law Owain Gwynedd, coincidently led by Owain's son - and my fuckin pookie - Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd. Apparently, again according to the Brut, Henry died 'by a shower of lances.'

Up next: Gwenllian!!!!!!!

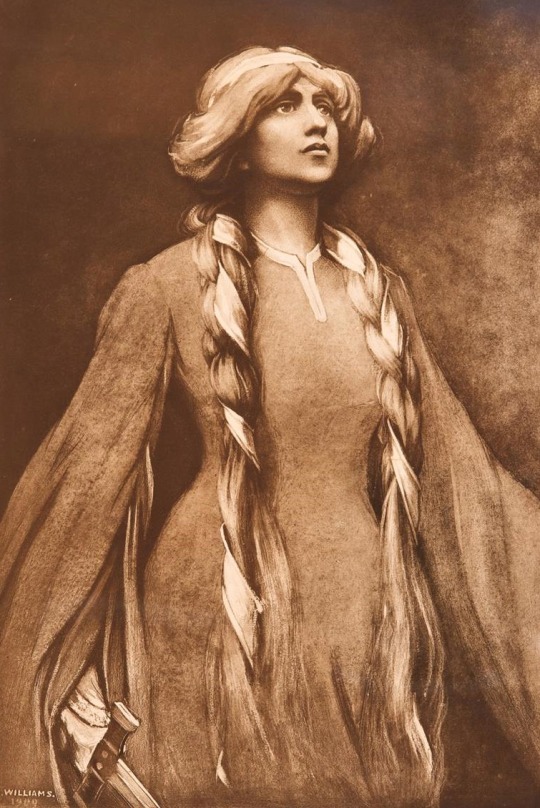

Sadly we have no drawings of Gwenllian, but that's okay cuz artists are more than up to the challenge. Also, idk why but the fact that she has red hair is generally accepted even though we don't know how she looked. I guess it's because bravery is telegraphed as red, or at least fieryness which, ngl, she defo was.

Born in about 1097, Gwenllian was the daughter of the King of Gwynedd, Gruffudd ap Cynan, and his wife, Angharad ferch Owain.

Gwynedd, at this time, was perhaps the most stable of the Welsh kingdoms, although Gruffudd ap Cynan HAD had to battle like fuck to free Gwynedd from the Normans before he could even sit on the throne. (He got thrown in Chester for a time and had to be rescued by a very tall man called Cynwrig. Will do a post on him because he's FUN) so rebellion is very much in Gwenllian's blood. We don't know much about her childhood although we can assume it was happy and filled with the various activities of a Welsh Princess.

Still, that would soon shift.

Gwenllian, at around about thirteen /fourteen or so (remember girls became women when they reached 14 under Welsh law), soon became involved with Gruffydd ap Rhys after her father hosted him when Gruffydd was hoping to summon up aid for his Getting Rid of the Normans scheme.

Unfortunately for Gruffydd - who I will now call Griff so as not to confuse with Gruffudd ap Cynan - this place at the Gwyddelian court became tenuous. Gruffudd ap Cynan, unwilling to further inflame tensions with the Normans after he'd just recovered Ynys Môn (Anglesey) from them and now ruled kinda peacefully, elected to hand Griff over to them. Somehow - probably through Gruffudd ap Cynan's nobles - news of this rescued Griff and he once again left for Deheubarth.

Only he wouldn't travel alone.

Gwenllian, unwilling to let the man she loved slip away, eloped with him and became his wife. They soon became 'the Robin Hood's of Wales' as Philip Warner writes and set about killing the Normans. Griff, emboldened by his and his wife's success hastened to meet with his father-in-law, Gruffudd ap Cynan, in an effort to get troops.

So, Gwenllian was left to helm her husband's forces by herself. To be fair to her SHE DID. AND honestly, this is why she's compared to 'Buddug' or Bouddica. Normans led raids a just as she and Griff had done against them- and she was compelled to rise an army for Deheubarth's defense.

The Great Revolt of 1136, as it was known, was to be Gwenllian's last conflict for she and two of her sons, Maredudd and Maelwgyn were beheaded by the Normans after their forces were routed at Cydweli Castle. Yet Gwenllian would not be forgotten. Her youngest son, the Lord Rhys, would become Prince of Deheubarth and recover much of the territory that had once been their family's. And Nest? Well, Griff had sent time in her and Gerald's castles as he went about letting how to get Dejeubarth back. It's tempting to think that she and Gwenllian met.

Also, Dr Andrew Breeze HAS argued that Gwenllian is the author of the Mabinogi because much of the action takes place in Gwynedd and Deheubarth where Gwenllian was based. Might it have been a tract to inspire people to rebellion? Or for women to know their worth? It's tempting but we'll never know. We can only guess. All we can say is 'Dial Achos Gwenllian!'

(That's Revenge for Gwenllian btw. Long may she reign, as it were.)

#gwenllian ferch gruffudd ap cynan#nest ferch rhys#house of aberffraw#house of dinefwr#welsh#wales#cymru#welsh history#hanes gymaeg#mytholeg#welsh culture#welsh stuff#welsh mythology#the mabinogion#mabinogion#welsh myth#welsh folklore#the lord rhys#owain gwynedd#y mabinogi#y mabinogion#the mabinogi#norman conquest of welsh#the laws of hywel dda#the tudors#arthuriana#queen guinevere#morgan le fey#gruffydd ap rhys#king arthur

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katherine Daubeney, née Howard, was Anne's mother's half-sister, and served as chief female mourner at Elizabeth Boleyn's funeral in 1538 [...] Following the execution of her first husband, Rhys ap Gruffydd, for treason in December 1531, Katherine married Henry Daubeney, the future Earl of Bridgewater. Theirs was not a happy marriage and, by 1535, both parties were actively seeking a divorce. In early October, Katherine appealed to Cromwell for support, and lamented that she has many kin 'and few that doth for me, unless [...] the queen's highness, which I am very much bound unto.' She noted, though, that her enemies were trying to 'set [Her Grace] to withdraw her favour from me.' [...] Despite the controversy that surrounded Katherine's marriages, Anne did not turn her back on her kinswoman like most of her family had done. Remarkably for the time, divorce was granted [...] as well as [...] 'her whole jointure at his death' [...] It's hard not to see Anne's influence behind this surprisingly favourable outcome, especially when we consider that within days of [Daubeney's letter] [...] the king and Anne anounced a visit to the Daubeney home, Bramshill House.

'The Final Year of Anne Boleyn’, Natalie Grueninger

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there,

I noticed you've been following me for awhile thanks. I saw some of your posts on the Howards and noticed that you mentioned somewhere that the Duke of Norfolk might have played a part in Cromwell's downfall in 1540 in order to get revenge for Anne Boleyn's execution.

That's a very interesting theory and I like it. Is there much evidence for any affection Norfolk or the other Howards had for Anne? I've always seen Norfolk as an evil villain who treated his family badly but maybe there was more to him than that?

Hello.

Sorry it's taken such a time to respond, but as you'll see it's VERY long, so I wouldn't start reading this on the bus.

Part One

As a child I used to be very annoyed by 20th-century writers treating historical figures like ice-cold robots welded to lifeless 'logic', and incapable of doing anything rash or ridiculous.

Oh why would Richard kill the Princes when it'd make him look bad?!

See? It must've been a plot by Margaret Beaufort all along.

(I know it's improved since then, but that first impression stuck.)

Reading history, I've always assumed family members instinctively cared for one another, unless their words and actions proved otherwise, and yet the above mentality pushed the exact opposite: that it was 'irresponsible' to even suggest any sort of natural bond between relatives unless they actually wrote it down, which is an absurd standard.

To me it's as silly as saying 'we don't know' if they breathed air as no one put it in a diary.

What does it matter how long ago they lived? They're still people.

I've even seen the extremely smug attitude that caring about one's own children is entirely a 'modern' invention, and the Mediæval and Tudor age wouldn't have understood such a concept.

Wouldn't have understood love!

Since then I've been interested in emotional bonds between friends and family, given how much closer they were than now, particularly rebelling against the idea Elizabeth didn't care about Anne.

And the Boleyns / Howards are my favourites, so their clannish level of kinship fascinates me the most.

Let's go through some of them:

Catherine Howard, Countess of Bridgewater

Catherine's first husband was Rhys ap Gruffydd, heir of a powerful Welsh family.

Problem was when his grandfather died Rhys got passed over (I expect because he was seventeen) in favour of Walter Devereux (the 10th Baron Ferrers), and Rhys wasn't 'avin that.

Devereux arrested him for disturbing the peace, which sent Catherine bananas as she'd convinced herself they were all out to get her husband.

In response she stirred up the local gentry and marched on Carmarthen Castle, threatening to burn the door down and bust on in there if Rhys wasn't freed.

Well after that unease and bitter factionalism bubbled up to denonation point, with servants killed on either side and Catherine attacking and destroying Devereux's property, meaning he sent word to England descibing BOTH of them as leaders of a 'rebellion and insurrection'.

Rhys sounds like a knob to me. You could say Henry caused this mess in the first place, but Rhys ought to have known where all this was leading.

His Wiki page lays it on that he was some noble folk hero martyred to the Reformation, but adding 'FitzUrien' to his name, thereby playing on ancient Welsh myths and thus (supposedly) announcing himself as Prince of Wales, was pushing his luck to say the least.

That's a worse blunder than Henry Howard made and no one ever feels sorry for him.

I shouldn't think he had conspired with James V, but going by this quote from the chronicler Elis Gruffudd (a very interesting fella in his own right) he wasn't universally mourned:

Rhys was beheaded in 1531, but Catherine was in the soup herself after all she'd been up to assisting him.

As Gareth Russell says:

'While we may never know exactly how much his own actions brought about Rhys's death, we can be certain of the devastating effect it had on his widow. She had been intimately involved in her husband's quarrel, and so the possibility that she would be accused of complicity in his alleged treason was tangible.

Left to forge prospects for their three young children — Anne, Thomas and Gruffydd — and fearful for herself, Lady Katherine followed in the footsteps of her elder brother Edmund and flung herself on the mercy of their niece, Anne Boleyn. Once again, the family's dark-eyed golden girl did not disappoint.'

It notable how often you see Anne, and later Elizabeth, willingly pull relatives out of sticky situations, which suggests at least some previous attachment on both sides, as I shouldn't imagine either would be too happy doing it for the more hostile characters.

Compare Katherine's reliance on Anne, a half-niece, to Elizabeth Seymour writing to Cromwell for help, not Jane, her own sister.

'She may even have tried to limit the damage for her aunt and young cousins shortly before Rhys's execution.'

Which was good of Anne considering Rhys had slagged her off, with both of those links having the nerve to imply his death was somehow her doing.

Had he lived, I do wonder if his opposition, compared to Catherine, who, familiarity or not, no doubt wanted to benefit from the connection, would've provoked a certain marital discord.

'Rhys had been attainted at the time of his conviction, meaning that the Crown could seize his goods and property, but his Act of Attainder specifically and unusally made provisions for his widow, who was left with an annual income of about £196.

If Anne could not save Rhys, she worked hard to salvage his family's situation.'

Meaning she got Henry to surrender some of his ill-gotten gains solely to avoid her aunt's destitution, where plenty of other widows and orphans were left to fend for themselves.

Anne also got Catherine a new husband in old-timer Henry Daubeney, but they bloody hated each other and split up soon enough.

According to Eric Ives:

'Over the winter of 1535-6, Katherine Howard, Anne's aunt, was trying to secure a separation from her second husband, Henry, Lord Daubeney. She told Cromwell that the only assistance she was receiving was from the Queen herself, and this despite the strenuous efforts which were being made to destroy her standing with Anne.

The help may have been very practical indeed; Lord Daubeney, who was certainly pleading financial hardship at one stage, reached an amicable agreement with his wife after Anne's father had made available £400.'

Even though this post about Catherine insists neither Anne nor Norfolk gave a toss about her personal woes, from the looks a things Anne was trying to solve this problem too.

'I have none to do me help except the Queen, to whom I am much bound, and with whom much effort is made to draw her favour from me.

My lord my husband has paid well to make friends against me, but I trust that the truth of what I suffer will be known...'

One wonders how all these paid agitators ended up gathered 'round Anne, nagging or distracting her from Catherine's cause, but evidently she wasn't put off.

Plus, according to that last link, Catherine never learnt her lesson and took part in the Pilgrimage of Grace an' all, raising 3,000 men against Henry!

By the sounds of it, this isn't a sudden burst of furious piety at work, rather there's almost an absence of religion in Catherine's life.

The obvious explanation would be yet again wreaking vengeance in Rhys's memory, and that's evident given her long-standing vendetta against his disloyal servants.

But would it be too much to think she was motivated to a certain extent by the death of her niece and nephew, being 'much bound' to the former?

And as she avoided all punishment, the remaining Howards (i.e. Norfolk) had to have covered up for her.

William Howard, 1st Baron Howard of Effingham

In 1529 there was much scrapping over the wardship of the Broughton sisters.

Wolsey ended up with the younger, Katherine, but upon his fall it seems Anne got the girl transferred to the care of Agnes Tilney, who then married her to William, so Anne was responsible for his first marriage.

(Not that it prevented Katherine Broughton from acting, as Ives puts it, as 'ringleader', in a demo for Mary six years later, and getting herself locked up in the Tower as a result, but there you go.)

Given the amount of important roles he enjoyed during Anne's queenship, all whilst barely out of his teens, she must have liked him:

• 1531: Ambassador to Scotland.

• 1532: Travelled to Calais with Anne to meet Francis.

• 1533: Served as Earl Marshal during Anne's coronation, in place of Norfolk.

• 1533: Held the canopy at Elizabeth's christening.

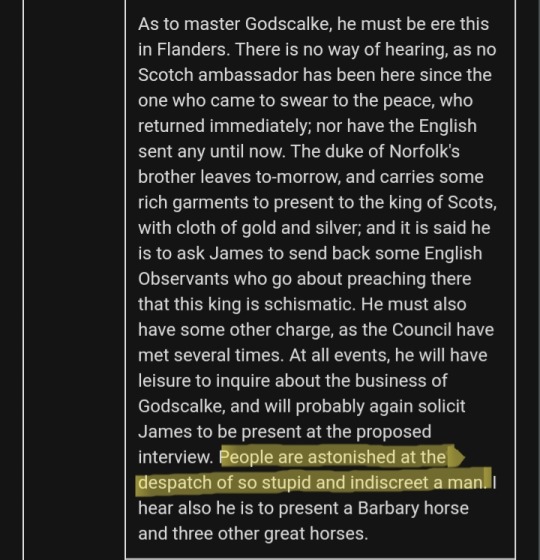

• 1535: Visited Scotland to award the Order of the Garter to James.

• 1536: Went again to Scotland to arrange a meeting between Henry and James.

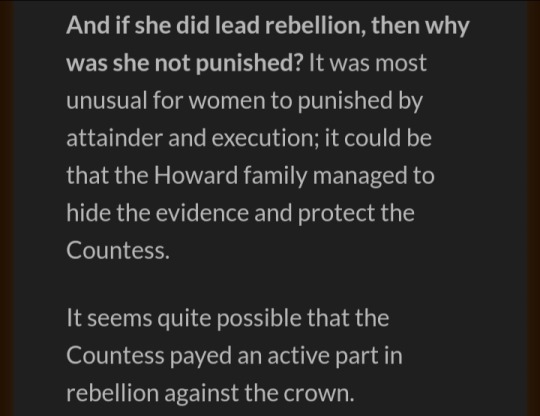

Besides, Chapuys said of him:

'People are astonished at the despatch of so stupid and indiscreet a man.'

So he had to be Anne's friend.

Once he hears of her arrest, William curses it as 'heavy news', demanding to know the truth from Cromwell and resenting all the Scottish clergy as 'capital enemies' for rejoicing in her fall.

Mainly I'm mentioning him to discuss his own character, and where his evident loyalty to other family might give us a further suggestion of his relationship to Anne, and how he kept to that sense of honour even when it led him into dangerous territory.

Consider, for example, how he named his son Charles after his brother, and called his daughter Douglas in honour Margaret Douglas, Charles's wife, thus commemorating their doomed romance.

You'd also be surprised how often he turns up in Young and Damned and Fair, as he appears to have been Katherine's closest uncle, for all that she's usually connected to Norfolk.

Indeed, so deep was he in it Agnes had to be advised not to warn him off coming home, meaning he arrived from France and found himself immediately clapped in the Tower, whereupon he craftily claimed all his best plate was washed overboard so Henry couldn't get at it, which worked.

Later, his connection with Henry Howard ensured he missed out on being Admiral, and when he did get it, Mary took it off him to punish his partiality to Elizabeth.

There's a section here detailing his bond with Elizabeth, where he's credited with saving her life, if you ignore the obvious errors:

I especially like the idea everyone feared William would kidnap Philip!

However, there's a very odd paragraph in his son's Wiki page:

'In 1552, he was sent to France to become well-educated in the French language, but was soon brought back to England at the request of his father because of questionable or unexpected treatment.'

Am I mad or does this imply Charles Howard endured sexual abuse in his teens?

Were it only poor lodgings or sub-standard teaching, he could've moved elsewhere.

Were it excessive beating, you'd expect it to be made plain, not using all this cagey, obfuscating language.

But the thought did lead me to ponder their father-son bond, where Charles, whatever shame he suffered, knew he was loved enough that writing to his father would make it stop.

And William, reading it, rescued him immediately, proving the boy right.

This is a mere fancy of mine, but when it's just after Elizabeth's ordeal, whom he obviously cared so much about, and knowing she could easily have died like Katherine, which happened in part because he never stopped Dereham, one wonders if his moral failing then pushed him to protect Charles and Elizabeth later.

Thomas Howard, 1st Viscount Howard of Bindon

I'm hard-pressed to unearth much information on this lad, but everyone leaves him out so I won't.

There's gotta be some reason Elizabeth ennobled him, and so early on (in 1559) before he'd had the chance to serve her.

It can't just be she looked round the court, noticed he was the last of Norfolk's children, and awarded him for that.

I wish we knew more about Elizabeth's childhood, as in who she met and associated with at court, because you can be certain she met the Howards then.

I also want to add a little about his eldest son, the 2nd Viscount, who was...odd, to say the least:

• Being a pirate;

• Dressing as a tramp;

• Beating everyone including his wife.

This gave me the the idea that perhaps his and Norfolk's reputation had somehow been rolled up together over the centuries, where this Henry Howard, although unknown today, was probably infamous in his time, and maybe his behaviour in a sense lended credibility to the accusations of spousal abuse against Norfolk, where people felt Henry 'got it from somewhere'.

When Elizabeth learnt what he was up to, she sent Hercules Meautys (what a name) to rescue his sister, and took Frances in, with her husband dubbing her 'a filthy and porky whore', which was rich coming from him.

And his other son, the 3rd Viscount, killed his own father-in-law and had a long-running feud with Walter Raleigh.

He also spent years trying to have his brother's granddaughter Ambrosia declared a bastard to grab all her land, so Elizabeth locked him up!

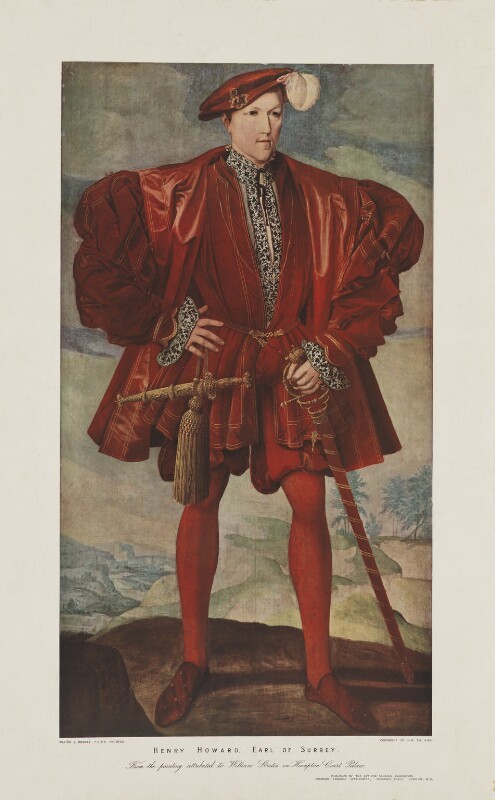

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey

Anne found Surrey a wife and took him with her to France, where he and FitzRoy remained as honoured guests until the next autumn.

He was then obliged to serve as Earl Marshal as Anne and George were sentenced to death.

Four years later, according to Gareth Russell, Surrey not only watched Cromwell's execution, but gloated about it afterwards:

'Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, stood at the forefront of the crowd and watched the scene without pity. He was missing his cousin's wedding to be here to see his family's bête noire finished off.

Later that day, he could not conceal his good mood. It felt to him like a settling of scores:

"Now is the false churl dead, so ambitious of others' blood."'

What does this mean?

Who's blood has Cromwell lusted after?

Who did he kill four years ago?

Surrey can't be referring to himself when Cromwell had actually protected him from punishment not long before, which in itself suggests a few interesting things:

• Cromwell was not yet aware of just how much the Howards despised him, as in, up til then his relationship with them was at least civil, cordial even, so the old line about Norfolk begrudging the 'new men' just because they're new men doesn't quite wash.

• This would've the perfect opportunity to bring down a mighty rival, but instead Cromwell felt bizarrely generous and intervened on Surrey's behalf, meaning he saw no harm in preserving the family, and instead thought it useful to get them on side.

• Why does he feel the need to favour the family?

Has he done something to antagonise them?

• The Howards are collectively putting on an Oscar-worthy acting routine of feigned friendliness, or at least indifference to said actions, so Cromwell, whilst he might suspect he's given slight offence, assumes it'll soon be forgotten if he pats them on the head here and there.

• Except whatever Cromwell did, saving Surrey wasn't enough to warrant forgiveness.

And let's examine this quote in detail:

Surrey is at 'the forefront' of spectators, keen to behold Cromwell dying in all its gory brutality, besides opting to watch such a horrendous deed over attending Katherine's wedding.

Instead of a happy celebration of his family's success, something he could've easily enjoyed in the knowledge of Cromwell being dealt with out of the way, he insisted on serving as a witness, as if it wouldn't be over until he'd seen it done, almost to be sure that it had.

For this would 'settle the score', shedding his blood in payback for... what exactly?

Thetford Priory?

Is that all?

Or for the blood Cromwell himself so coveted?

And even the sight of such suffering left Surrey unmoved, ridiculing the dead man not only as a 'churl', but a 'false' one.

False to whom?

'False' as in affecting loyalty to his Queen whilst working to bring her down?

Because is that extreme level of hatred really just supposed to be nothing deeper than empty class prejudice?

Usually, Cromwell's fractious history with the Howards is portrayed as Norfolk's one-man defamation campaign of all-encompassing lordly outrage verging on eye-popping insanity, except Surrey clearly loathed him too.

Perhaps from that we can conclude that Cromwell had become unpopular with the whole family, hence the 'bete noir' reference above.

When Surrey's resentment is remembered, it's conveniently boxed up and filed away as the same-old 'snobbery' of his father, which a very neat, uncomplicated excuse that prevents us looking into it properly.

I daresay Surrey was proud and class-conscious, but wouldn't everyone be like that, to a greater or lesser extent?

Why then is this 'haughtiness' only ever attributed to characters we're supposed to dislike, namely Anne, Norfolk, and occasionally George and Surrey, with the 'good' people somehow immune to such 'base' emotions?

Indeed, I'm starting to wonder how much real evidence there is for this common supposition of arrogance.

As if Surrey's known at all, it's for the manner of his death, namely he 'got himself killed' by 'stupidly' quartering the royal arms with his own, which, whilst a gross oversimplification, nevertheless defines him, where history views his character through this lens and reads his entire life backwards, as if there's no explanation for his behaviour other than he was just born to be a cocksure moron.

It plays upon modern bigotry against aristocrats, where they're all stuck-up, slow-witted inbreds fixated with the pecking order and archiac symbolism, keeping the honest worker down to prove they're better than everyone else, which is a laugh because they're all REALLY shallow, superfluous chuckleheads and deserve what they get.

Since the idea Surrey died for something so 'silly' as what badge went where slots so well into the stereotype, then it's cheapened his reputation overall.

Rather than being highly esteemed as a pioneer of English literature and the forerunner of Shakespeare, he's treated as nothing but a hot-headed toff tripped up by his own idiotic pretensions, with an end offered as a 'fitting' denouement, almost a lesson in morality; about where not 'knowing your place' or 'getting ideas above your station' leads... after vilifying Surrey and Norfolk for apparently demanding people know their place and not get ideas above their station.

Something hypocritical there.

There's also a reflexive judgementalism within this fandom and the lower end of publishing (i.e. novels and pop. history) where it's assumed if Anne or any of her family are executed, then even if they're technically innocent, they must've deserved it really, else 'the universe' wouldn't let it happen.

Therefore, known evidence is read with the most bad-faith interpretation, with any declared slip leapt upon and blown out of proportion, solely to prove their own bias correct.

You're right to think that, you are.

Hating them makes you A Good Person.

Again, this ONLY applies to Anne and her supporters, not her enemies.

No, no. They were martyrs to the Cause.

But I wouldn't say Surrey's usage of royal arms spoke to any pathological sense of superiority, certainly not to the extent it should define his memory.

Heraldry and ancestry is the lifeblood of nobility: everyone he knew fought for whatever their birth and court careers entitled them, so why shouldn't he?

Look at his sister protesting again and again and again for her rights as FitzRoy's widow: does this make her a 'snob' because she never gave up fighting?

In fact, dubbing Cromwell a 'churl' doesn't mean too much either.

The average person objects to someone because they're a thief, cheat, liar, etc. but calling them as much is a toothless insult, as they'd require a sense of honour to feel the sting.

And if they had that, they would've have committed the offence it in the first place.

So, you pick on something they probably are sensitive about, such as status or physical appearance, to get your own back.

Calling Henry VIII, for example, a fat bastard, doesn't mean you oppose him for having a weight problem, or that you dislike fat men generally.

It's that you're hitting 'below the belt' to inflict the worst punishment you can.

Oh yeah, it's petty, but the aggrieved often are.

Surrey's real crime, if we deem it one, was apparently rash language of what vengeance he'd wreak on his foes once the King was gone, meaning the Seymours.

So is it mere coincidence that the main targets of this infamous 'snobbery' are those who caused or benefited from Anne's fall?

Are we to believe his only complaint, right down to twice vetoing Mary Howard's marriage, is nothing better than looking down his nose at humble Seymour origins, for they've done nothing whatsoever to draw his ire?

For all the time I've been reading history, the way the court of 1536 splits between the Boleyns and those pushing Jane Seymour, and then, once the Boleyns are wiped out, it greatest rivalry becomes Howard versus Seymour, one lasting for the remainder of Henry's reign, has always struck me as both telling and appropriate.

The idea the Howards took over hating the Seymours because of their slain family is to me to most obvious explanation; the driving force pushing the enmity beyond a decade, and blaming it all on snooty la-di-da attitudes baffles me.

It's so pat and offhand, as if it was thrown into historical research centuries ago and never questioned, passed down to us as unassailable received wisdom, rendered true from repetition, as no one likes Surrey or Norfolk enough to bother reassessing their motivations.

But could such prolonged open hostility run on no greater impulse than keeping the gentry in check?

Is THAT all?

And do note how leading this narrative is, where, if we accept the Howards despised the Seymours as upstarts, then the fault for all bad blood is immediately shoved onto them and them alone, when those poor Seymour lads, rosy-cheeked and pure of heart, are just doing their best in life, working hard and loving everyone.

But oh! Those nasty Howards bullies are So Mean!

Not once is it reversed, proposing that the Seymours envied the Howards' breeding and birth, vowing to bring them down out of spite.

Instead they're absolved of all guilt in the conflict and justified in everything they do as a self-defence measure, even when they brought about Surrey's death and tried it on ten years previously.

So why on earth should he like them?

How I wish this painting still existed.

Starkey describes Henry Howard thus:

'Surrey inherited all Buckingham's grand pride in blood and aristocracy, and all his determination that noblemen should once more come into their own.

Perhaps it was from his mother's side too that he got his most dangerous trait: a rashness and a violence that bordered on madness.

Add to all this an intelligence that was both penetrating and fast and the result was one of the most remarkable men of the age.'

And yet I don't know of any aggressive outbursts prior to 1536, being then known for 'soberness and good learning'.

We tend to class poets of later eras as on the sensitive side, so far from being 'always like that', it may well be that the deaths of George, Anne, FitzRoy and putting down the Pilgrimage of Grace knocked him off the rails, a process then driven beyond all remedy by watching Katherine die and the suicidal shame he endured over his military failures.

Although I do like the sound of him as the hero of High Fantasy.

Whilst I'm here, let's look at this very awkward scenario of Surrey attending the triple Neville wedding, being the children of his mother's intended and her sister.

Considering how desperate so many are to clear Henry VIII of Anne's death, protesting how he Genuinely Believed and that makes it alright then, he's cheerful enough fannying about as a Turk less than two months later.

Finally, writing this I read several of Surrey's poems, and must include this truly endearing piece commemorating his wife's love for him:

Such a poet, and still no one credits him with any tender emotions.

Anyway, don't mind me but I've hit the picture limit.

I'm not sure when Part Two will be done, but I'll let you know, come the time.

#Henry Howard#Catherine Howard Countess of Bridgewater#William Howard#Thomas Howard 1st Viscount Howard of Bindon#Anne Boleyn#Elizabeth I#Henry Howard 2nd Viscount Howard of Bindon#Thomas Howard 3rd Viscount Howard of Bindon#Frances Meautys#Rhys ap Gruffyd#Thomas Cromwell#Young and Damned and Fair#Gareth Russell#The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn#Eric Ives#David Starkey#Quotes

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

GWENLLIAN FERCH GRUFFYDD // PRINCESS OF DEHEUBARTH

“She was Princess consort of Deheubarth in Wales, and married to Gruffydd ap Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth. Gwenllian’s “patriotic revolt” and subsequent death in battle at Kidwelly Castle contributed to the Great Revolt of 1136.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heroínas

Boudica

Boudica foi rainha da tribo britânica Iceni, que liderou uma revolta fracassada contra as forças do Império Romano em 60 ou 61 d.C.

Boudica era a esposa do rei Prasutagus que governou suas terras como um aliado independente de Roma e que, portanto, deixou sua propriedade dividida entre o imperador Nero e a esposa e duas filhas. Após sua morte, no entanto, as terras icenas foram usurpadas por Roma, Boudica foi açoitada e suas filhas foram estupradas pelos romanos por ousarem presumir que tinham direitos que deveriam ser reconhecidos por Roma.

Boudica rapidamente reuniu sua tribo e atacou três cidades, resultando em mais de 80.000 cidadãos romanos massacrados. Boudica foi derrotada na Batalha de Watling Street em 61 d.C. por Suetônio, que criteriosamente escolheu o local da batalha para favorecer seu menor número.

Uma estátua de Boudica e suas filhas foi concluída em 1905, encomendada pelo príncipe Alberto como presente para a rainha Vitória, admiradora de Boudica. A estátua fica perto da Casa do Parlamento e da Ponte de Westminster, em Londres.

Boudica é considerada uma heroína nacional britânica e um símbolo da luta por justiça e independência.

-> Estátua de Boudica em Londres, Inglaterra

~*~

Gwenllian ferch Gruffydd

Gwenllian ferch Gruffydd foi uma princesa galesa que liderou um exército na batalha contra os normandos.

Gwenllian ferch Gruffydd era casada com Gruffydd ap Rhys, Príncipe de Deheubarth. Dizia-se que ela tinha uma grande beleza, era inteligente e bem educada. Gwenllian viveu em tempos conturbados, pois os senhores galeses perderam muitas de suas posses para os normandos após a invasão da Inglaterra por Guilherme, o Conquistador, em 1066. Como havia recebido treinamento militar, Gwenllian lutou ao lado de seu marido. Ela e Gruffydd lideraram ataques a assentamentos estrangeiros tomando bens e dinheiro para redistribuir entre os galeses que foram despossuídos por esses colonizadores, como um par de "Robin Hoods de Gales".

Enquanto seu marido estava em Gwynedd buscando uma aliança com seu pai, os anglo-normandos fizeram ataques e Gwenllian assumiu o comando do exército. Em uma batalha um de seus filhos foi morto e ela e seu outro filho foram capturados e executados. A notícia da morte de Gwenllian e seus filhos enfureceu os senhores galeses, que rapidamente se juntaram à rebelião.

As ações de Gwenllian foram comparadas com as de outra líder celta: Boudica. O campo onde se acredita que a batalha tenha ocorrido, é conhecido como Campo de Gwenllian e por séculos depois, os galeses usaram "Vingança por Gwenllian!" como um grito de guerra

Hoje em dia algumas pessoas acreditam que Gwenllian pode ter sido a autora dos Quatro Ramos dos Mabinogi, as primeiras histórias em prosa na literatura da Grã-Bretanha.

1 note

·

View note

Text

gruffydd ap cynan

a different gruffydd ap cynan who is the first one's great-grandson

gruffydd ap rhys

a different gruffydd ap rhys who is the first one's grandson (it literally goes rhys-gruffydd-rhys-gruffydd)

gruffydd ap llywelyn

gruffydd ap maredudd, who is gruffydd ap llywelyn's grandson

a different gruffydd ap maredudd who i don't think is closely related to him. but is the nephew of the second gruffydd ap rhys

gruffydd ap rhydderch. who is not related to any of them except that his great great granddaughter eventually married gruffydd ap maredudd (the second one)

that's assuming I am even reading this diagram correctly

the worst thing about medieval Wales is how everyone has the same name. there are eight people called gruffudd in this one diagram* i'm looking at and they're all within about a hundred years of each other. get more names!!!

*sort of a family tree? but some parts of it are fairly tangentially connected

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

RHYS AP GRUFFUDD

Prince of Deheubarth

"THE LORD RHYS"

(born circa 1132 - died 1197)

pictured above is an imagined portrait of the Prince of Deheubarth, painted by Jean Pierre Victor Dartiguenave circa 1870

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

RHYS was born around 1132, on an unrecorded location, probably in the Kingdom/Principality of Deheubarth, modern-day Wales in the United Kingdom.

As one of the sons of Gruffudd ap Rhys and Gwenllian ferch Gruffudd, he was a member of the HOUSE OF DINEFWR. He was named RHYS AP GRUFFUDD, meaning Rhys son of Gruffudd, following Welsh tradition.

Before he was born, his family had lost the Kingdom of Deheubarth to the English. And, at the time of his birth, even though his father had control over a small portion of Deheubarth known as Cantref Mawr, the territories were under Norman rule.

Sources and historians diverge on the definition of Deheubarth since the Norman invasion. Some call it a Principality and others a Kingdom.

By 1135, his father took advantage of the death of Henri I, King of the English, to take control as the rightful King of Deheubarth.

pictured above is the coat of arms of the Kingdom/Principality of Deheubarth

Both of his parents died when he was young. As the Welsh continued to fight the Norman Lords, his mother died while leading an army during the Great Revolt of 1136, while his father was killed in 1137. So he was probably orphaned before his 5th birthday.

What was left of Deheubarth was inherited by his eldest brother, Anarawd ap Gruffudd, an illegitimate son of his father who became the new Prince/King of Deheubarth.

In 1143, when his eldest brother was killed, another of his illegitimate brothers, Cadell ap Gruffudd, became the new Prince/King of Deheubarth.

Nothing is known of his childhood. The first time he was recorded was in 1146, aged around 14 years old, fighting over Llansteffan Castle, alongside his brothers.

His brother Prince/King Cadell suffered an attack in 1143, barely surviving, and decided to abdicate and leave the country. Deheubarth was left to him and another of his older brothers, Maredudd, the only legitimate surviving sons of his father.

So, from the age of about 21, he ruled as joint Prince/King of Deheubarth until the death of his brother around 1155-57, becoming the only PRINCE/KING OF DEHEUBARTH.

At some point around these events, he married GWENLLIAN FERCH MADOG, a daughter of Madog ap Maredudd, Prince of Powys, and Siwsana ferch Gruffudd. With his wife, he had at least eleven children. But he also had illegitimate children.

Check a list of his legitimate and illegitimate children at the end of this post!

Henri II, King of the English, invaded Wales in 1157, starting with the Kingdom of Gwynedd. Before the English invaded Deheubarth, he tried to negotiate an agreement but was forced to give up almost all of Deheubarth.

Over the next years, he fought the English but was not successful. At some point, he had to give his sons as hostages and was also taken hostage himself, only to being freed and having to pay homage to the King of England.

Between 1164-70, he united with other Welsh Princes, from Gwynedd and Powys, in an uprising against the English. At that time, one of his sons was blinded by order of King Henri II.

Following the death of his maternal uncle, Owain "Gwynedd," Prince of Gwynedd, in 1069, he became the leader of the Welsh Princes against the English.

He made peace with King Henri II in the early 1170s, even sending help to stop a rebellion of the sons of the King around 1173/74.

During a council in Oxford, in 1177, he and other Welsh Princes held homage to the English King. And, he received the territory of Meirionnydd, part of the Kingdom of Gwynedd.

Amidst the peace years, he rebuilt Cardigan Castle in Ceredigion, in stone, and founded Talley Abbey in Carmarthenshire.

However, when King Henri II died in 1189, he considered that the truce with the English had ended and began to attack the Norman Lords again. Even though the successor, King Richard I and his brother Jehan "Lackland" tried to make peace again.

Meanwhile, his own sons started to rebel, as some supported Norman Lords that were related to them by marriage. So, he ended up imprisoning some of them along the 1190s.

The Prince of Deheubarth died excommunicated in 1197. Though the place of his death was not recorded, it was likely in the Principality of Deheubarth. He was circa 65 years old when he died.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

To succeed him as ruler of Deheubarth, he chose his eldest son Gruffudd ap Rhys II. But Maelgwn, another of his sons, refused to accept, and the brothers fought over the inheritance until the death of Gruffudd in 1201.

Llywelyn "the Great," Prince of Gwynedd, divided the remainder of Deheubarth in 1216. And, following the English conquest over Wales, Deheubarth was completely dismantled by 1284.

Through his daughter Gwenllian, he is an ancestor of the House of Tudor, and therefore, he is an ancestor of Charles III, the current Monarch of the United Kingdom.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

RHYS and his wife, GWENLLIAN, had eleven known children.

Gruffudd ap Rhys II, Prince of Deheubarth - married to Maud de Braose;

Maredudd ap Rhys - married to an unknown woman;

Cynwrig ap Rhys - probably unmarried;

Rhys "Gryg" ap Rhys - married first to an unknown woman, and possibly second to Maud de Clare;

Maredudd ap Rhys, Lord of Cantref Bychan - probably unmarried;

Maelgwn ap Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth - married;

Hywel "Sais" ap Rhys - possibly married;

Maredudd ap Rhys, Archdeacon of Cardigan - unmarried;

Gwenllian ferch Rhys - married to Ednyfed "Fychan" ap Cynwrig;

Morgan ap Rhys - nothing is known about his life; and

Nest ferch Rhys - possibly married to Rhodri ap Owain "Gwynedd," Lord of Anglesey.

And, he also had illegitimate children.

With an unknown woman:

a daughter - married to Einon "Clud" of Elvael; and

another daughter - married to Einon ap Rhys of Gwerthrynion.

With one of his nieces:

Meurug ap Rhys - nothing is known about his life.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

COLLECTION: Descendants of the Kings of the Britons - #DotKotB

In a span of four generations, Rhys ap Gruffudd, Prince of Deheubarth, was related to the Kings of the Britons through the paternal family of his wife.

His wife was Gwenllian ferch Madog;

Her father was Madog ap Maredudd, Prince of Powys;

Her grandfather was Maredudd ap Bleddyn, Prince of Powys; and

Her great-grandfather was Bleddyn ap Cynfyn, King of Gwynedd and Powys - a King of the Britons in the 11th century.

But he was himself a more distant descendant of the Kings of the Britons through the maternal family of his father.

His father was Gruffudd ap Rhys, King of Deheubarth;

His grandmother was Gwladus ferch Rhiwallon;

His great-grandfather was Rhiwallon ap Cynfyn, King of Powys;

His 2x-great-grandmother was Angharad ferch Maredudd; and

His 3x-great-grandfather was Maredudd ap Owain, King of Gwynedd, Deheubarth, and Powys - a King of the Britons in the 10th century.

#rhys ap gruffudd#rhys ap gruffydd#prince of deheubarth#dinefwr#welsh royals#welsh royalty#british royals#british royalty#monarchy#monarchies#royals#royalty#royal history#welsh history#british history#history#history lover#history with laura#middle ages#the anarchy#DotKotB

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Going West: A Wounded Church

Going West: A Wounded Church

I had barely raised the camera to start photographing the interior of the great cathedral at St Davids before a gentleman approached and told me that I could not… or, at least, not without paying for a permit. Now, I know that these ancient churches cost a good deal to keep standing and pay for their conservation, but I have a problem with those that demand exorbitant entry fees before forcing a…

View On WordPress

#Celtic Christianity#Geraldus Cambriensis#Life#Norman Cathedral#pembrokeshire#Rhys ap Gruffydd#sacred sites#Silent Eye 2016 Workshop#spirituality#St David&039;s#The Silent Eye

0 notes

Photo

MARY: SERIES ONE

When King Henry VIII announces his daughter unable to inherit the crown of England, Princess Mary Tudor and her friends at court rebel and conspire against him.

An imagined six episode psychological drama series, focusing on Princess Mary Tudor and the intrigues, secrets and lies of Henry VIII’s court...

THE KING’S PEARL

Princess Mary Tudor, Princess of Wales and heir to the throne of England, is at her court in the Welsh Marches. Rhys ap Gruffydd kneels in irons before her; he has been arrested for inciting rebellion and is on the way to the Tower of London. Rhys petitions Mary for help in getting his grandfather’s lands and titles restored to him, as they are his by right and not her stewards, who has been gifted them by the king. Rhys says surely Mary knows what it is like to have an inheritance threatened. Mary promises to help him when she returns to court. Rhys thanks his princess, stating that though his wife is related to the king’s mistress, Anne Boleyn will never be Rhys’ queen.

Mary returns to court for Christmas. All along the streets nobles and peasants alike cheer for their princess before she is welcomed lovingly by her parents King Henry VIII and Queen Katherine of Aragon.

There is a grand feast; Mary reunites with her father’s cousin Henry Courtenay and his wife Gertrude, one of Katherine’s ladies. She dances with the courtier Nicholas Carew while her parents watch proudly.

Mary petitions her father to release Rhys from imprisonment in the Tower. The king, delighted to have his pearl back, agrees, but refuses to grant him his grandfather’s lands and titles. The pair decide to go riding together.

On their return, Gertrude escorts Mary to see her mother. She tells Mary her father’s mistress, Anne Boleyn, has just arrived back at court. Katherine introduces Mary to Eustace Chapuys, ambassador to Mary’s cousin Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Chapuys promises he will do his best to help her and her mother. Katherine and Chapuys reveal Pope Clement has forbidden the king from marrying Anne, threatening him with excommunication from the church if he does.

After Mass, where the royal family pray together, a freed Rhys seeks out Mary. He thanks her for his release and attempting to get his inheritance back.

Mary goes to her father’s chambers, where Thomas Cromwell introduces himself as King Henry’s new minister. Mary asks where her father is. When Cromwell replies he is with Anne Boleyn, Mary leaves for the sanctuary of her mother’s rooms.

Henry Courtenay arrives from parliament, telling Katherine, Mary and Gertrude that the king has now declared himself the Supreme Head of the Church of England. Gertrude tells them she heard of a nun in Kent who can predict the future. Katherine warns her not to do anything foolish.

On Saint David’s Day, the patron saint of Wales, Mary is given a Welsh leek by the king’s gentlemen pensioners in a grand ceremony. She is watched by a crowd of courtiers and Chapuys, who compliments her. They talk for a while before she leaves.

Exiting, Mary comes across Anne Boleyn. They glare at each other before Anne reluctantly sinks into a curtsey. Mary ignores her.

Mary plays the virginals for her parents. Despite their praise, there is obvious tension between the pair.

At nightfall Mary and her father talk. Mary is confused how he has declared himself the head of a church that doesn’t exist. Henry says she is clever; one day his pearl will understand. After he has left, Mary tells her governess, Margaret Pole, that she doesn’t think she will ever understand.

Katherine worries when Margaret wakes her in the night to inform her Mary is ill. Gertrude brings up the Nun of Kent again, but Maria Willoughby and Jane Seymour shush her. Katherine goes to help Margaret care for Mary. As Mary continues to vomit, Katherine strokes her daughter’s hair, clutching her necklace which she believes contains a piece of the True Cross. She prays her daughter will get better, comforting her with old stories of her and King Henry when they were younger.

In the morning a recovered Mary wakes to six luxurious new dresses, a gift from her father. She immediately puts one on.

At breakfast, the queen is sat at the table alone. The king left them earlier in the morning to go on summer progress with Anne Boleyn, forcing most of the courtiers to go with them, including the Courtenay’s. Katherine smiles and tells Mary they can still have a good time, just the two of them and their households.

Reginald, the son of Margaret, is sent money by the king to study in Padua. Katherine and Margaret are hopeful Reginald will convince King Henry to recant his decision to break from Rome and marry a heretic. Reginald promises he will. Mary hugs her cousin goodbye, wishing him well.

At court, Chapuys watches on with Nicholas Carew and an incensed Gertrude and Henry as Anne Boleyn takes the queen’s role at a feast. While talking, Rhys Gruffydd is publicly re-arrested for encouraging Wales to rebel against the king, and supposedly taking the title of Prince of Wales. The group disbelieve this after what Mary did for him.

Katherine hears from Maria that Rhys has been beheaded, but she is determined to protect her daughter and keeps the news a secret.

Mary and Katherine go hawking, but on their return are sent orders to separate. Katherine promises she will see Mary soon, encouraging her to stay strong. Any bastard born of Anne Boleyn will never rule; Mary is the heir and future queen of England.

PRINCESS OF WALES

Mary and her tutor Richard Featherstone are having a Latin lesson on Utopia by Sir Thomas More. In the book women are encouraged to fight in battle; Mary tells the priest she would if she could.

Mary is walking in the fields with her ladies, Susan Clarencius and Anne Hussey, and her cousin Margaret Douglas. Her and Margaret’s cousin Frances Brandon has recently married Henry Grey. Mary is betrothed to the French Dauphin, but she has heard no news lately of a marriage... she is surprised to come across her father, riding with Nicholas. He asks how she is and Mary replies she is well, but missing her mother now she has seen him. The king is going to Calais with Anne Boleyn, now the marquess of Pembroke, but promises to see her more often when he returns.

Gertrude sees the Nun of Kent in disguise, switching clothes with her maid. Amazed at her trance, she invites the woman, Elizabeth Barton, to her house.

Mary is having her breakfast served by her friend Henry Jerningham when she is informed by her chamberlain that her father has, with the blessing of the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, married Anne Boleyn. John Hussey asks for a verbal response to the news for the king, but Mary ignores him entirely, continuing to talk with Henry and her ladies. Uncomfortable, he carries on with his orders; Mary is forbidden from writing to her mother and he must take Mary’s jewels. Margaret refuses to give them up to John unless she has a direct order from the king.

Gertrude welcomes Elizabeth warmly, asking about her prophecies. The nun says there may be war now the king has married Anne Boleyn; Gertrude asks her to pray her husband will remain safe. It grieves him that men of noble blood are being dismissed from the privy chamber, with the king ruled by Cromwell who is the son of a blacksmith.

That night, Gertrude tells Henry about the nun’s visit, telling him the king will flee the realm one day. Henry is horrified at her listening to the prophecies, potentially earning the wrath of his cousin when he finds out. He demands she tell the king.

Mary and Margaret Douglas are informed by Margaret that their aunt Mary has died. The pair worry over Frances, but Margaret tells them she has a husband to comfort her now. Mary fears the French accepting Anne Boleyn as queen means her betrothal will be void. The three are interrupted by Mary’s servant Randall Dodd, who delivers a letter passed on by her mother’s servant Anthony. Katherine writes she has “heard such tidings today that I do perceive if it be true, the time is come that Almighty God will prove you; and I am very glad of it, for I trust He doth handle you with a good love [...] But one thing I especially desire you, for the love that you do owe unto God and unto me, to keep your heart with a chaste mind, and your body from all ill and wanton company, not thinking or desiring any husband for Christ’s passion; neither determine yourself to any manner of living till this troublesome time be past.”

Shortly after there is an official command from King Henry to take Mary’s jewels. Her personal arms are stripped from her and her household is to be reduced, with some servants, including Randall Dodd, sent to wait on her new sister Elizabeth, whose christening John Hussey must attend.

King Henry confronts Gertrude, informing her that he knows she has visited the Nun of Kent. She petitions King Henry to forgive her, blaming her womanly foolishness. He does, and orders his cousin to as well. To show his goodwill towards her, Gertrude is bestowed the honour of becoming Princess Elizabeth’s godmother, but an annoyed Gertrude sees it as an insult.

Mary is playing a card game with her ladies and Henry Jerningham when John returns from the christening and tells Mary she is longer a princess. Mary refuses to accept it and writes to her father, believing he was “not privy to it, not doubting but you take me for your lawful daughter, born in true matrimony.”

In response to her letter the Duke of Norfolk comes to dissemble all her household; Mary is to go to Hatfield to serve her sister Elizabeth, the Princess of Wales. Mary says that title belongs to her by right, and no one else.

Mary is only allowed to take one lady in waiting with her and chooses Susan. Her cousin Margaret Douglas is to serve the new queen. Margaret offers to serve Mary at her own expense, but Norfolk refuses. Mary has an emotional goodbye with her staff. Margaret urges her to remember her grandmother had been declared a bastard before becoming queen of England.

On the way to Hatfield, one of the men escorting Mary whispers she must hold firm, for the sake of England.

Arriving, Norfolk asks if she will pay her respects to the Princess of Wales. Mary replies she knows of no other princess in England except herself. The daughter of the marquess of Pembroke has no such title - but if her father acknowledges her as his own, she will call her sister as she calls Henry Fitzroy brother.

As he leaves, Norfolk asks if can take a message to the king. Mary says to tell him his daughter, the Princess of Wales, begs for his blessing. When Norfolk refuses, Mary tells him curtly he might leave it then, and to go away and leave her alone. She retires to her bedchamber to cry.

UNBRIDLED BLOOD

Mary refuses to pay court to Elizabeth unless made to by force. When walking, she is always far in front or far behind the newborn, never at her side. She eats in her own rooms with food Susan steals from the kitchens, avoiding the public table. She has outgrown the ornate dresses her father gave her.

An outraged Gertrude shows Chapuys the letter she has received from the king, telling his subjects that they ought to thank God for giving them a lawful heir. Chapuys reveals he has already sent a Latin declaration for Katherine to sign and pass along to her daughter.

The king arrives to visit his youngest daughter. Mary is desperate to see her father, but is visited by Norfolk and Cromwell. They urge her to renounce her title, but Mary says it is labour wasted to press her; they are deceived if they think bad treatment, rudeness, or even the chance of death would make her change her determination. She asks to see her father and kiss his hand, but is refused. When they leave, she runs to the terrace at the top of the house and kneels in mercy. The king bows and doffs his cap, as do the men with him, before leaving.

The Oath of Supremacy and 1534 Act of Succession are both implemented, making Henry VIII Head of the Church of England, and Elizabeth and any other children of Anne Boleyn his heirs. The Courtenay’s are annoyed as queen Anne flaunts her belly; she is pregnant again.

Mary receives a letter from her mother, which comforts and encourages her, along with the Latin declaration Chapuys spoke of that denies her illegitimacy. She signs it and Susan smuggles it out of Hatfield back to Chapuys.

John Hussey and his wife Anne are returning home now Mary’s household has been dissolved, but before they go John talks with the Courtenay’s and Chapuys about the possibility of the emperor invading in support of his cousin’s rights. Chapuys says he is trying hard to convince his master. Henry says he wishes he had the opportunity to shed blood in the service of Katherine and Mary. John replies he could easily rise the north of England to help Princess Mary, and “the insurrection of the people would be joined immediately by the nobility and the clergy”. Gertrude reminds them of the prophecies of the Nun of Kent; perhaps there will be war over this...

When moving households, Mary refuses to share a litter with Elizabeth and is forcibly put in by guards. Roughly manhandled, she shouts a public protest to some peasants who salute and cheer her as princess. Her new caretaker, Anne Shelton, warns Mary her niece queen Anne has ordered her to box Mary’s ears as a cursed bastard when she uses the title of Princess.

After Gertrude informs him of Mary’s abuse, Nicholas pays the king’s fool to insult queen Anne and princess Elizabeth. The king is furious, banishing the jester from court, but Nicholas shelters him in his own home.

A badly bruised Mary hears of Nicholas’ actions and sends a letter of thanks to him via Susan. Shelton summons Mary to visit her, questioning why she has received a letter from Elizabeth Carew, Nicholas’ wife. Elizabeth urges her to submit to the king for the passion of Christ, otherwise she will be undone. Mary pleads ignorance and throws the letter in the fireplace.

As they watch queen Anne and her uncle Norfolk prepare to visit Elizabeth, Jane Seymour tells the Courtenay’s that the queen has had a miscarriage. They fear how she will treat Mary.

As punishment for the litter incident, Norfolk takes Mary’s remaining jewels. He mocks a brooch from her childhood spelling out the Emperor. Mary is furious, even more so when Anne visits her, urging her to honour her as queen and she will reconcile her to her father. Mary says she knows of no queen of England but her mother - but if her father’s mistress would intercede on her behalf, she would be much obliged. An enraged Anne storms out, swearing to bring down her unbridled Spanish blood.

Shelton tells Mary if she were the king she would kick her out of the house for disobedience, and that the king said she will lose her head for breaking the law and not renouncing her title. Seeing Richard Featherstone preparing to leave in the retinue of queen Anne, a quick witted Mary asks him if she can practise her Latin. The people around them do not understand as she asks if the rumours are true and she is to be killed. Richard is shocked, saying it is not good Latin before leaving with the rest of Anne’s entourage. Returning to London, he immediately informs Chapuys of the danger Mary is in. The ambassador is determined to find a way to see her.

The Nun of Kent is publicly executed, with her head put on a spike on London Bridge. After, the king tells Henry the trust his daughter has in the emperor makes her obstinate, but he fears no one if his vassals stay loyal. He warns his cousin not to trip lest he lose his head.

WORST ENEMY IN THE WORLD

After she was forced into a litter, Mary asks to ride on her horse when moving households. As soon as she is mounted, she races ahead of her sister’s litter, riding across the countryside to the waiting river barge. Exhilarated by the freedom of her ride, she beats the rest of the household there and takes the place of honour. On the riverbank, Chapuys watches on as Mary sails past. They smile at each other, reassured.

Shelton wonders how the ambassador knew they would be there. Suspecting Susan of sending messages in and out of the household, she dismisses Mary’s last lady. Mary is completely alone.

Months have passed; it is now winter. King Henry remains furious at his daughter’s continued defiance, telling his cousin Mary will be an example to show that no one ought to disobey the laws; at the beginning of his reign he was as gentle as a lamb, and by the end he will be worse than a lion. Henry tells his wife.

Gertrude disguises herself to visit Chapuys, saying after the next parliament Mary and Katherine will die. She swears it is as true as the Gospel. Gertrude is adamant they must do something to help save their princess. Chapuys says Katherine spoke to him of Mary marrying Reginald Pole and uniting their claims to the throne. The emperor is busy taking Tunis, but Chapuys believes only a small army sent by Charles V with Reginald amongst the troops would be enough to make people declare for Mary. Gertrude pledges the support of her relatives, but says they need a quicker solution.

Mary is no longer allowed to eat in her room, but she refuses to eat at the main table and submit to a lower rank then her sister Elizabeth, now a toddler at the head of the table. She is slowly starving.

After seeing the king talking with Jane Seymour, Gertrude has an idea. She tries to convince Jane to attract the king’s attentions in the hope of getting better treatment for Mary but a haughty Jane refuses.

Mary is constantly belittled by servants, who say the world will be at peace when they are discharged of the pain and trouble she gives them. She is incensed to hear the French ambassadors are to visit Elizabeth in the hopes of a betrothal. She declares she is the Dauphin’s future wife, not her bastard sister. Shelton orders her to her room, and when Mary refuses she is locked in by force.

The next morning, a weak Mary discovers she has started her period. Disoriented, she calls out for her mother and Margaret. While getting up, she collapses.

Shelton weeps, fearing people will think she has poisoned Mary. She tells a bedridden Mary the king will not see her until she admits to being a bastard. He believes she is his worst enemy in the world. Mary sobs but refuses to give in, saying God has not blinded her to confess her father and mother had lived in adultery and made her a bastard.

Chapuys talks to Cromwell and then the king, trying to convince them to let Katherine tend to her daughter. Henry refuses; if mother and daughter are together, Katherine might “raise a number of men and make war, as boldly as did queen Isabella her mother.” He also refuses to send Margaret Pole, who Chapuys calls Mary’s second mother, as she is a fool of no experience. If Mary had been in her care she would have died, but Shelton is an expert in female complaints.

After queen Anne shows no sympathy for a grievously ill Mary, Jane agrees to help Gertrude.

Mary is examined by a doctor. She fainted due to her heavy period, in addition to not eating or drinking enough. She is suffering from sorrow. The doctor orders her to eat more and recommends being moved closer to her mother to improve her spirits. Mary knows it will never happen.

Shelton reveals Sir Thomas More and several monks have been executed for refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy, and Richard Featherstone is now imprisoned in the Tower. She tells Mary to take warning by their fate. Servants openly desire her death, especially now the queen is pregnant again with what is sure to be a son. Mary notices her old servant Randall Dodd does not join in their bullying. Cornering him in private, she convinces him to deliver a letter to Chapuys.

Gertrude leads Jane to Nicholas, and the pair coach her on how to act. Nicholas tell Jane she must by no means comply with any of the King's wishes, except marriage.

Mary watches out of the window as armed guards are stationed at the gates. Randall walks through them, carrying a letter for Charles V urging the emperor to invade. Mary tells him “In the name of the Queen, my mother, and mine, for the honour of God take this matter in hand, and provide a remedy for the affairs of this country; begging you in the meantime not to forget to solicit permission for me to live with my mother.”

MONSTER IN NATURE

Chapuys visits a mortally ill Katherine. She worries over her daughter, but he promises to look after her. After Maria Willoughby arrives she is no longer alone and begs Chapuys to go and protect Mary.

Mary is summoned to see Shelton, who informs her of her mother’s death. She is devastated. Shelton implores her to submit, saying she will not receive the necklace her mother left her in her will. Mary replies she would rather die a hundred times than change her opinion, before going to her bedchamber to cry.

Randall gives a letter to Mary from Chapuys, making plans for her to escape England. The emperor cannot spare any troops, but there is a ship waiting 40 miles away if she can get there. Chapuys says he will write with a plan soon but Mary is convinced she must go at once lest she be killed.

Chapuys holds a dinner party with the Courtenay’s, Nicholas and Jane. Nicholas has been inducted into the Order of the Garter over George Boleyn. They discuss queen Anne having a quarrel with Cromwell, and rumours of the king wanting a new wife. Gertrude advises Jane to tell the king his subjects hate his marriage, and no one considers it legitimate. A messenger arrives for Jane from the king, with a letter and a purse of money. All watch on with approval as Jane sends it back, saying she can only accept a gift of money from the king when he makes her an honourable match. Chapuys hopes the progress of their scheme will mean Mary will not need to flee - he tells them “she is so eager to escape from all her troubles and dangers that if he were to advise her to cross the Channel in a sieve she would do it.”

In turmoil, a grieving Mary takes matters into her own hands. While playing with Elizabeth she tests the strength of the garden gate, noting where Shelton’s window looks out. Returning to the house, she tells the doctor she can’t sleep. He says he will get her some pills to help.

On the same day Katherine is buried, queen Anne has a miscarriage. The king tells Henry he has been seduced by witchcraft into his marriage, which is null because God has not granted him a son.

Mary laces some wine with the sleeping pills, and prepares to give it to Shelton and her maids. Only a letter from Nicholas delivered by Randall dissuades her. He begs her to “be of good cheer, for shortly the opposite party will put water in their wine as the King is already sick and tired of the concubine as could be.” Mary replies telling them to do everything possible to remove the mistress.

At queen Anne’s trial for adultery against the king, Henry votes guilty. He, Gertrude, Nicholas and Chapuys watch on as Anne is beheaded and Jane marries the king.

Mary is astonished to receive a visit from her old lady, Anne Hussey. They have returned from the north as John has to attend parliament, where Elizabeth will be declared a bastard now queen Anne is dead. While talking to Mary, Anne calls for a drink for the princess, and is arrested. Mary is in shock and writes a letter to her father, hoping to reconcile with him now her enemy is dead.

After being presented as the new queen, Jane tells the Courtenay’s, Nicholas and Chapuys that Henry has received his daughter’s letter but is not happy. She promises to help Mary, and Chapuys christens her the peacemaker.

Margaret Pole returns to court, attracting hundreds of people on the way who think Mary is with her. She carries a scathing letter from her son Reginald. King Henry is outraged that Reginald accuses him of tearing true defenders of religion to pieces, as well as likening him to the tyrant emperor Nero.

A group of nobles headed by Norfolk arrive to harass Mary into signing the acts, calling her a monster of nature and a traitress for continuing to defy her father. When she argues with them they say if she were their daughter they would beat her to death, or bash her head against a wall until it was a soft as a boiled apple.

Mary is locked in her bedchamber and not allowed to talk to anyone. She is to be watched over day and night. Hours pass and she refuses to back down. The guards are changed - this time Randall is on duty. Mary creates a distraction for the other guard and passes a scribbled letter to Randall for Chapuys.

Jane pleads for mercy, but the king calls her a fool for interfering; she ought to think of the children they will have together and not any others. King Henry swears that not only will Mary suffer, but also his cousin, Cromwell and others.

Anne is interrogated in the Tower for calling Mary a princess, but she insists it was merely due to habit. Henry is kicked off the privy council, and Nicholas is questioned about his relationship with Mary. Legal papers are drawn up to put Mary on trial for treason.

Randall returns, detailing what has happened to her friends and giving Mary a letter from Chapuys. Chapuys points out she now has a better opportunity of becoming heir to the crown than when Anne Boleyn was alive. He urges her to save her life for the tranquillity of the kingdom, and comforts her with the knowledge that “God looks more into the intentions than into the deeds of men.”

Fearing for her and her friends lives, a broken Mary finally submits to her father and signs the document before her without reading the contents.

GRACE

Mary lies awake in the night crying before being disturbed by a knock at the door - Susan has returned. She is to resume her duties as the king is riding to see Mary.

A nervous Mary sees her father for the first time in years, along with his new wife Jane who gives her a diamond. King Henry says he regrets their long separation, giving Mary some money and the necklace Katherine left her daughter in her will. He promises she can soon return to court.

Freed from the Tower, Anne returns north with her husband John, where the people mutter about the king being ruled by evil ministers who have closed the monasteries and forced Princess Mary to sign acts labelling her a bastard.

Mary returns to court, where the king pats Jane’s stomach, insinuating she is with child. He tells Mary some of his councillors were desirous of her death and she swoons in fear, but her father assures her all will be well now. She sits beside the queen at the high table while Gertrude serves them.

Cromwell welcomes Mary back, congratulating her on finally signing the acts and calling her “the most obstinate woman that ever was.”