#in reflection as a gay/trans adult and thinking about what those things might have potentially been expressing or something

Text

edit sorry this post is both long (if the readmore fails i am truly truly sorry) & longwinded im just reflecting and thinking; (another edit: u can probably just read the tl dr and get it)

anyway allow me to spin some very personally based theory here for a mo while i put off/warm my fingers up from the cold in preparation to email my therapist

so growing up i had, i think only, het ships, but i never quite had the ones you were (narratively speaking) “supposed to” have

in most media i recall when i was a kid, there were like, 2 diff structures of character romance plot arcs in media i consumed, there was the main lead and 2 best friends model, where thered be the star of the show who had outside romantic leads and the 2 best friends (who were always a boy and a girl) would have their secondary romance, OR there were ensemble shows where there was a more clear romance set up between the main boy and main girl, then side characters whod pair off in whatever ways ended up happening. in the first, see: hannah montana, the second, see: zoey 101. obv this isnt a hard rule and there were loads of exceptions but like, lets just say i tended not to care for the romances set up for the main girls in the trio models, or quite as hard for the main boy and girl in the ensembles, and in general if there was an obvious romance between two leads i either didnt care or outright hated it

basically i never liked the ships they set up for us in straight media, as a kid (namely, a girl) i liked being that “ew pink!” “i hate valentines day” sort of contrarian, but what i remember actually disliking was the predictability of it, because i clearly still shipped characters, so it wasnt /really/ that i hated romance, per se

looking back on it i think it was probably or at least to a degree more like that i hated the hetero expectation of it- i can nit pick down to more specific examples of why i disliked the main pairings (kataang, for example, i thought was weird bc katara acted like a mother/older sister figure to aang, and i didnt feel like there was romance between them at all except where it felt shoehorned in) - maybe it was also that i thought it made more sense for a main character to be with someone they clearly already spent a lot of time with and not some random new hot boy in town (i very distinctly remember shipping miley and oliver on hannah montana, and i believe that was the first time i ever read fanfiction @ age like... 11 lol) as is often the case w like these things.

theres another level to this though, which is that i notice i tended to ship characters who were more vaguely similar to each other, like, physically (ie, similar heights, or hair colors mainly) obviously this is funny now since my main pairing is johnlock which is such a physically different ship we can construct them from basic shapes and colors and theyre still recognizable as who they are, but i have some thoughts about this- but i think there might be two interesting things about this again in retrospect

first of all, this sounds silly ik, but shipping the vaguely similar ones as a child’s way of queering heterosexuality is an interesting concept and not that difficult, like, two boys are also vaguely similar to each other in a similar way a boy and a girl with the same hair color and height might be, which is something i thought of a while ago

the other way in which this is really interesting to me now, that i think might have been more actually pertinent to myself as a trans child, is that i think i shipped the characters i did in an attempt to morph the concept of boy and girl? to find the boy counterpart to every girl??? that second one makes more sense actually. anyway, i digress

2 start off i definitely had gender feelings starting from a very young age so i think these observations ring more true than just reflections, PERHAPS

so the first thing i remember shipping, ie wanting them to be together, thinking about it an inordinate amount of time outside watching the films, even imagining them eating ice cream together in their pjs (i was NINE DHFJGghfkg) was jack sparrow & elizabeth swan from potc (basically my franchise of choice as a kid bc i never read harry potter) now this doesnt quite fit the “visually similar” thing bc actually orlando bloom looks more like kiera knightly and is prob due to them like making out in one movie, but i think this works for the “shipping as gender expression” theory, because elizabeth swan dressed up as a boy, spent most of that movie wearing boy’s clothes, etc- meanwhile jack was a wacky pirate which like hello duh i’d want to be. so i wonder if beyond the fact that they kissed and flirted, there was something to this concept of me wanting two characters to be together, meant i wanted to marry together two conceptual things happening with two characters, or absorb the cool dude and the boyish girl characters into each other to make one whole archetype for myself? i likewise shipped aang and toph (toph who, normally doesnt really have anyone to be shipped with, since she likes sokka but he has a gf) who we all know is the VERY boyish girl character, so boyish im p sure her actually being a trans dude later in life is a p decently accepted headcanon (i dont actually delve into aatla fandom though so i can only hope)

another thing about this ship thing, is most of my ships had brown hair (like miley and oliver), just like i always have, and in certain cases the girl character would look a LOT like me (i also shipped logan and quinn on zoey 101, which to my surprise n delight actually came true later (although looking back im like... 11 yr old me is glad they made out a lot but adult me is like uhhh why were the kids on this show making out a lot? anyway thats another issue) and i def was a weirdo girl with glasses and long brown wavy hair) which sort of further fuels my feeling that this was an attempt by my brain to do 1 of 2 things, if my own involvement really was a greater motivating factor in this thing, 1. ship MYSELF with a boy (which is like def possible for my gay kinnie ass, but not quite my thesis here) or 2. morph these boy and girl counterparts by imagining them together, seeing them together, etc

for example, i realize now, when i was a kid i drew an avatar sona for myself and said sona looked an awful lot like how id imagine a katara/zuko fusion would be, and the fact that i shipped zutara (very hard lol) was what lead me down this thought path rn

i feel like even to me this concept sounds weird and far fetched but like, gem fusion made enough sense for someone to write with its clearly, usually, romantic implications and we all “get” that, so whom knows???

another thing ive noticed while writing this is for a good few of these ships you can argue the boys in them can be read gay, like jack sparrow and zuko and aang, which feels even more strongly like me trying to marry my gay boy feelings to my tomboy realities [thinking emoji]

the biggest reason i think this makes sense to me is because when i was 10 i became obsessed with the idea that this boy i was friends with and i were secretly twins separated at birth, like i was so into the concept that we looked alike, i like hoped and wished so hard for it to be true, i wished a christmas miracle would happen for fucking real and a magic door in my house would open and be his new room and itd all work out perfectly! and you might think this was a manifestation of my difficulties with my family and wishing to leave it, but in my dream world my parents were still my parents and he came to live with us- which makes me think the obsession of ME looking like this BOY was a manifestation of my gender feelings, which i think can maybe be traced to this concept of pairing a visually similar, possibly gay, brunette boy to every brunette and/or tomboyish girl

anyway. if you actually read all of this id love it if you lmk somehow (doesnt need to be a like) like this is clearly very long and strange but i hope it makes sense. i think i stop myself a lot from ever commenting on gender or theory or whatever but i am a living breathing trans person who has experienced things and i have opinions and i dont think im claiming anything destructive with this lol i think its not unusual to reflect on the way you interacted with the world as a gay/trans kid

also im obviously not saying that shipping straight things is somehow inherently queer, im not trying to retroactively claim something about straight ships, like, those two characters are still functionally straight, and i definitely also shipped probably all of them for normal shipping reasons (although, kid ones, so less “oh theres a lot of ACTUAL romantic subtext between these two” but rather “oh theyre friends and would be cute together!” (or like they kissed and i was like O: )) but im just trying to theorize about something its possible my tiny trans brain was trying to express- and who knows maybe im not the only one!

anyway i guess the TL;DR is: when i was a kid i had a lot of “unconventional” straight ships- i already observed that i eschewed the main canon pairings in kids media in what was probably my tiny baby brains rejection of hetero culture, but i also actively shipped side characters who looked like me, and also looked like each other (ie, both tall and brunette, a boy and girl counterpart of Each Other) OR characters who seemed to be a gayish boy and a tomboyish girl, and im theorizing that maybe the reason that was was my tiny trans brain wanting to gem fusion those two together because of my Gender Feelings and fuse the boy with the girl and this desire manifested in shipping therefore thinking about a lot these pairings of boy and girl counterparts

#please dont be weird about this post i hope its like understandable what im trying to think about here?#like i dont think its that weird to consider nor am i claiming anything bad or destructive about ppls lives n genders n whatever#purely an observation about myself and the way i consumed media ages like 8-12#in reflection as a gay/trans adult and thinking about what those things might have potentially been expressing or something#i dont know any official queer theory stuff n i dont think that should stop me from thinking my own thoughts so here u go#also i am TRULY sorry if this readmore doesnt work

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Let’s talk about upcoming books!

It’s hard to believe the year is nearly over, but it’s equally hard to believe that it’s somehow still 2020 ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ Either way, the new year means at least one good thing- cool new books!

Click the read more for a little on each and why I’m excited! And have a great new year! 💓🎉

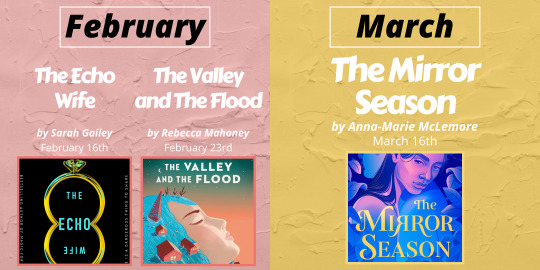

The Echo Wife by Sarah Gailey is Gailey’s third full-length novel, and their second Adult novel. It’s an SFF story about a woman whose husband is cheating on her… with a clone of herself… which he made by stealing her research. The layers of betrayal! Obviously her and the clone have to kill him, what other choice do they have? I’m super excited for another one of Gailey’s fun, complex characters and the concept alone sounds so, so cool.

The Valley and the Flood by Rebecca Mahoney I’ve already had the pleasure over reading and I am PUMPED to get other people to read it! This is a magical realism story about grief and baggage mixed with a southern (western?) gothic vibe with the town in the desert full of otherwordly “neighbors”. This is a beautiful story of PTSD and healing and as well as a lushly magic one.

The Mirror Season by Anna-Marie McLemore is another one I’ve already been lucky enough to get an advanced copy of. This is a magical realism story about the trauma of two characters’ unfortunately closely connected sexual assault. This one is heavy, and if you’re sensitive to stories involving rape and/or blackmail you may want to avoid it, but it’s well written and honestly an excellent story of healing and reflection.

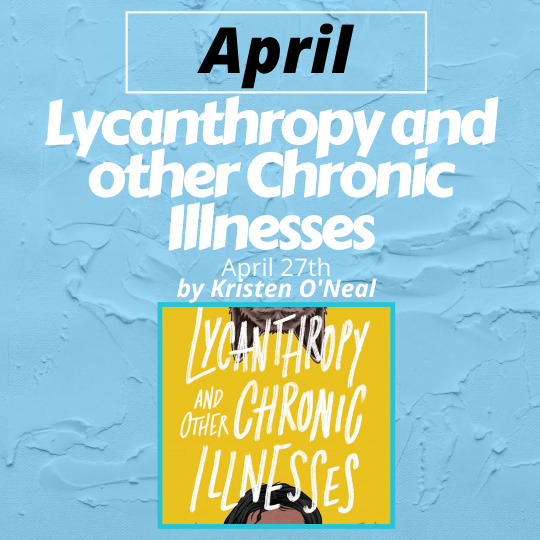

Lycanthropy & Other Chronic Illnesses by Kristen O’Neal I…. have also already read! Sorry- I am just a very lucky reader of books! This is a really modern online friendship based story of a girl and her community of people with chronic illnesses, like the one that forced her to come back home from college. But it turns out her best friend’s chronic illness is a little… weird. I love the humor in this book, I love the characters, I love the representation of these illnesses and the online communities they form, and I honestly think that anyone who 1) like werewolves and 2) is still on tumblr will love this book.

Blade of Secrets by Tricia Levenseller combines three of my favorite things- bladesmiths, magical quests, and the author of The Shadows Between Us. A magical bladesmith takes a commission from someone far more dangerous than she knows, and winds up with an uber powerful sword able to steal secrets, on the run, and with some surprising friends. I can’t think of anything I don’t like from that, and I know I already love Levenseller’s characters, so!

Mister Impossible by Maggie Stiefvater has… that title, but is also the sequel to Call Down the Hawk, Stiefvater’s Ronan Lynch centric TRC spin off. CDTH was incredible and ended with a massive cliff hanger, so I’m chompin at the bit for this book. More magical dreams! More disembodied voices! More murder and art theft and Declan Lynch failing at pretending not to be weird af!

May the Best Man Win by ZR Ellor has the potential to make me cry right from the get go. This is a MLM trans lovers-to-enemies-to-friends-to-lovers story and my God I’m vibrating. Basically it’s a battle for prom king between exes who had a messy break up because one of them ended their relationship in order to come out & transition. The cover is so cute and I’m ready for this to be fluffy and fun.

One Last Stop by Casey McQuiston is McQuistion’s sophomore novel after Red, White & Royal Blue, so… obviously? This one is sapphic and involves falling for someone who is literally in the past. I trust McQuiston so much I’d need this book immediately even if the concept didn’t sound amazing, but I’m feeling blessed that it does!

Violet Ghosts by Leah Thomas is about being best friends with (and crushing on) a ghost while also coming out to yourself as trans. As an enby who likes ghost books- may I just say trans rights? This book also involved parental abuse, so beware if you find that distressing or triggering!

Blood Like Magic by Liselle Sambury not only has a stunning cover and a main character who looks like she means serious business, but it’s a dark urabn fantasy about witches. The main character fails her ritual to come into her magic, she’s forced to kill her true love or strip her whole blood line. Ah, I love difficult choices, gray morality, and magic, so I’m already in love with this.

The Box in the Woods by Maureen Johnson I’m astounded and super excited to know is going to exist at all. I loved the Truly, Devious trilogy, and while this isn’t exactly a part of that it is the same main character and it is still a mystery about an unsolved murder! Plus, I love summer camps, so a summer camp murder mystery makes me happy.

Gearbreakers by Zoe Hana Mikuta is a sappic enemies-to-lovers about two girls on opposite sides of a war fought by giant Windups. This is a cyberpunk book of spies and pilots and gay love, and it’s also the first in a series!

Any Way the Wind Blows by Rainbow Rowell is the third and (most likely) final book of the Simon Snow series and it’s gonna be GOOD. My only wish is for it to be about 500 pages longer because I want a full out door stopper of tying up loose ends.

The River Has Teeth by Erica Waters is the second book by the Ghost Wood Song author- which was on my most anticipated list for 2020 last year! That one was creepy and folky and queer, and this one looks to be the same. This one has a sister disappear and some strong magic to find out what happened to her, and if their mother was the one who did it.

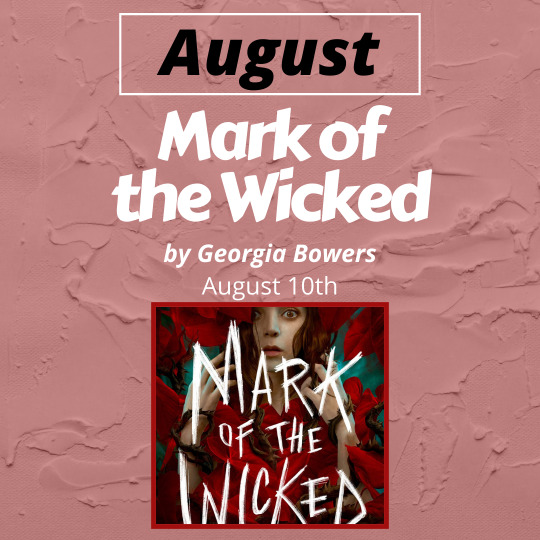

Mark of the Wicked by Georgia Bowers is a dark fantasy about a girl who comes into her powers but has some different ideas about how she should be using them. I love morally gray or just plain dark main characters, so I’m ready to jump right on this one. This one also involves memory loss/blacking out and being framed, which always adds a cool mysterious layer!

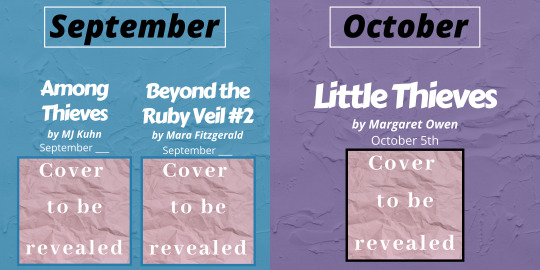

Among Thieves by M.J. Kuhn involves queer, selfish thieves forced to band together. I have a soft spot for characters who are really flawed and don’t want to work together (especially if it leads into found family!) and this also has a slow burn sapphic relationship and a lot of possible betrayal in it, so I’ll probably go crazy from reading it.

Beyond the Ruby Veil #2 by Mara Fitzgerald doesn’t have a title yet but it does have a great plot to work off of. I loved the first book- which was creepy, had a completely awful, villainous main character, and full (I mean full) of murder- and it ended in a way that point to the sequel being just as good if not better. The first one had the quality of just watching the world burn, and I have a feeling this one’s going to be the same thing with maybe more flames. If you plan on picking up either of them, consider checking out the CWs, though!

Little Thieves by Margaret Owen got added to this immediately because Owen definitely gained my love and trust via The Merciful Crow duology, and I’m certain it’s going to be incredible solely because she’s a wonderful writer and her characters are a lot of fun- and speaking of characters, she’s already shared some drawings and info on them and they’re GREAT I cannot wait to meet them. This is a retelling of The Goose Girl story, from the maid’s POV!

Jade Fire Gold by June C.L. Tan was originally on my 2020 most anticipated but then 2020 happened so… yeah. But it is actually coming out in 2021, as long as the world doesn’t end again (fingers crossed). Inspired by East Asian mythology, this one is about a dangerous cult, a peasant cursed to steal souls, and an exiled prince!

The Heartbreak Bakery by A.R. Capetta is going to be one of those cute, fluffy, feel good reads, which I think we probably all need about now. I love Capetta’s work and their very queer characters, and I love the idea of a magical baker both breaking up and then getting couples back together. Also, the MC is agender- we love to see it.

The Second Coming by André-Naquian Wheeler follows a teen with a traumatic past falling for a boy who might be the second coming of Jesus Christ. Honestly, I’m a little nervous about this one- but also I almost wrote my own queer second coming story, so who am I to talk? I don’t know much more about this book, but I’m excited to see what it turns out like!

#new books#2021 books#2021 releases#the echo wife#sarah gailey#the valley and the flood#rebecca mahoney#the mirror season#anna marie mclemore#lycanthropy & other chronic illnesses#lycanthropy and other chronic illnesses#kristen o'neal#blade of secrets#tricia levenseller#may the best man win#zr ellor#mister imposible#cdth#maggie stiefvater#one last stop#casey mcquiston#violet ghosts#leah thomas#blood like magic#lielle sambury#the box in the woods#truly devious#maureen johnson#gearbreaks#zoe hana mikuta

45 notes

·

View notes

Link

On May 14th, 2021, The Lancet published an editorial titled “A flawed agenda for trans youth”. This contains a number of weak or flawed arguments and rhetorical framing that I believe are far below the quality one might reasonably expect from a publication as prestigious as The Lancet.

On April 6, 2021, amid a flood of new bills to curb the rights of transgender and gender diverse (trans) youth in the USA, Arkansas became the first state to prohibit doctors from providing youth (<18 years) with gender-affirming treatment: puberty blockers, hormone therapy, and gender-affirming surgery.

From the outset, the focus is on the political and legal situation in the US, which of course is not reflective of the global picture. Seen from the UK, our legislative, medical and political landscape are markedly different, but that has not stopped this article being shared approvingly by UK-based lobbyists such as Stonewall’s Nancy Kelley.

Here we see that editorials such as this are not merely narrowly focused on the specifics - and ethics - of care of vulnerable youth, but actually in service of wider political lobbying. This is evident from the language and framing of the whole editorial:

However, what the bills seek to protect appears to be traditional gender norms, using a vulnerable group in a protracted culture war. The bills' socially conservative advocates create fear by focusing on emotive issues, honing the same messaging around protecting women and children that was used in earlier campaigns against abortion and same-sex marriage. As clinicians, it is important to use evidence to debunk the false claims being made.

The author castigates “social conservatives”, and links opposition to euphemistically titled “gender-affirmative care” as akin to anti-abortion or anti-gay marriage.

This is a binary framing that bears no real relation to the actual breadth of opinion and concern out there. For sure, many social conservatives are in opposition on those grounds - but there is a failure to recognise and account for the positions of the many people who come from an entirely different position. People who embrace and encourage gender nonconformity, who fought for gay marriage, and who now see current attitudes as a regressive approach to behavioural stereotypes that are harming predominantly gay and lesbian youth.

Disproportionate emphasis is given to young people's inability to provide medical consent, a moot point given that—like any medical care—parental consent is required.

This is not a moot point. A parent does not have unlimited power to subject a child to elective medical treatment. Indeed, this is the entire crux of the matter: is the treatment necessary? Does the potential benefit outweigh the potential harm? Is a child capable of understanding what they are consenting to?

This is why so much of this is framed in life-or-death terms - because absent some imminent threat, there is no justification for subjecting a child to experimental treatment in the first place.

Supplanting parents with the law for this decision presumes that a parent living alongside their child cannot grasp what is best for them, despite often witnessing many years of struggle.

And yet, parents abuse their own children, and sometimes the duty of the state is to intervene in the best interests of the child. This is a legitimate conflict - simplistically pretending it doesn’t exist, or that a balance is not needed to be struck, denigrates the debate.

Driving this consent narrative is the anxiety evoked by focusing on the minority who regret transition (estimated as 1% of adults who had gender-affirming surgery as adolescents).

This cites a recent meta-analysis of 27 articles, going back to the 80s. As such, I think it has the following weaknesses for making this specific claim:

It covers decades of adult transitioners. Adults are not directly comparable to children because there is wide variation in the persistence of dysphoria past adolescence (as high as 88% in a recent study). This is a key point of contention with early intervention, because this would indicate a nearly 9-in-10 chance of unnecessarily and permanently medicating a child. If regret samples are only drawn from the pool of those who persist into adulthood, then of course regret measures will be lower.

It covers surgical outcomes only. This again does not apply to children maybe given puberty blockers and hormone treatments.

Patients lost to followup or who (for whatever reason) do not proceed to surgery are often not accounted for - and by the above metric these could easily be patients who presented for treatment, before desisting, something much more likely with younger patients. For example, the meta-analysis cites the following paper as having a cohort of 132, only 2 of whom express regret. But actually, the paper starts with 546, which becomes 201 participants, only 136 of whom proceed to surgery, 4 of which are lost to followup. This is a very different picture, with 75% of the recruited sample an unknown quantity - and it is those lost to contact, or refusing to participate, or who simply drop out that are most likely to contain those with regret.

Whatever else, I don’t think that regret rates of adult surgical transition are a useful proxy for regret rates of children who have been affirmed as the opposite sex from a young age and proceed through puberty blockers to cross-sex hormones. I think these are entirely different groups, and using the best-case success rate of one to downplay concerns about the other is disingenuous.

However, in any situation when medical treatment will alter a person's identity, no one can know whether post-treatment regret will occur; therefore what matters ethically is whether an individual has a good enough reason for wanting treatment. Regardless of law makers' stance on identifying with a gender other than one's birth-assigned sex, the autonomy for this decision lies with young people and their parents.

Autonomy, but also clear and informed consent. A child who simplistically believes they are in the wrong body, who may be struggling with internalised homophobia - or homophobic parents - and comorbid mental health issues. Who has been told by people they trust that blockers and other interventions are necessary, and that they will simply go through the “correct” puberty for their “identity”, is being told lies. Phrasing such as “birth-assigned sex” is part of that lie - for sex is determined at conception, and cannot be changed. The association of the word “gender” with “sex” is part of that lie. How can anybody meaningfully consent when surrounded by such imprecise language? Why are children encouraged to change their sex characteristics to express their “gender identity”? What does any of this even mean? When even the Lancet publishes misleading data about rates of regret, or the reversibility and side effects of blockers (see below), how can a child understand this complicated and contradictory picture and offer informed consent?

More fear is stoked by rhetoric about a malevolent threat to children. Social conservatives in the USA, UK, and Australia frame gender-affirming care as child abuse and medical experimentation. This stance wilfully ignores decades of use of and research about puberty blockers and hormone therapy: a collective enterprise of evidence-based medicine culminating in guidelines from medicalassociations such as the Endocrine Society and American Academy of Pediatrics. Puberty blockers are falsely claimed to cause infertility and to be irreversible, despite no substantiated evidence.

Again, the editorial frames opposition as “socially conservative” - and completely ignores the social progressives who are expressing concern. This is simply not a narrative that fits the polarised binary of US liberal/conservative politics. In fact - especially in the UK - opposition is largely left wing, from those who don’t believe that gender nonconformity is something that should be medicalised, and who are worried at the prevalence of gay and lesbian youth in the cohort of children now being referred for paediatric transition.

It is telling also that the study offered to rebut the claims about infertility or irreversibility of blockers is not applicable. The cited paper is a study of the effects of blockers as a treatment for several conditions, but the author here cites the outcome when treating precocious puberty, ie in the instances where a young child is given blockers to halt early pubertal development for a short period, and then allow the remainder of normal adolescence to continue as much as possible.

This is not at all applicable to the treatment of children who go on to cross-sex hormones. These children never experience natural puberty. Blockers in this instance do not delay, they prevent it entirely, and substitute with synthetic hormones to encourage the development of opposite sex characteristics. This is a wholly different treatment pathway, and yes, blockers cause infertility and in some cases complete loss of sexual function, as well as other long term issues.

And the paper itself confirms this:

I believe The Lancet are wholly wrong to present this position with such certainty, and that by making claims that are contradicted by the given citation they fatally undermine this claim.

The dominance of the infertility narrative, usually focused on child-bearing ability, perhaps reveals more about conservatives' commitment to women's role as child-bearers.

Again, this does a huge disservice to the actual debate. The focus is on such things as fertility and sexual function because these are the very things children are incapable of consenting to lose. A child cannot know if they will never want to have a child of their own. A child too young to experience an orgasm cannot consent to never experiencing one.

Puberty blockers are framed as pushing children into taking hormones, whereas the time they provide allows for conversations with health providers and parents on different options. Gender transition involves many decisions over a long time, and those who take hormones do so because they are trans. Contrary to claims of a new phenomenon, trans youth have always existed; historians show they have sought trans medicine since it became possible: the 1930s in the USA.

The concern is that affirming the social sexual transition of a child too young to understand what sex is, is fixating on a fantasy identity that then becomes a medical one, again before a child is too young to know the implications. This is something borne out by the difference in desistance rates between children left to resolve their gender identity in adolescence (ie, allowing non-conforming boys and girls to simply be authentically nonconforming boys and girls) which are up to 88%, and the <1% desistance rate seen with the affirmation approach at the Tavistock. If the intervention itself is fixating and medicalising an otherwise fluid identity, is that really in the interests of the child? And again, this was found in the Keira Bell case - blockers are not in practice “a pause” for “time to think”, rather an early intervention to avoid the development of secondary sexual characteristics and lay the ground for inevitable cross-sex hormones.

Focusing on potential harms ignores the fact that wellbeing is broader than physical health alone. The harms to wellbeing posed by prohibiting care are huge. Being a marginalised group (<2% of US youth), trans youth already experience the stress of discrimination and stigmatisation. They have high rates of depression, anxiety, and suicide: almost double the rates of suicide ideation of their cis peers. As Laura Baams discusses in her Comment, puberty blockers reduce suicidality.

Except as the published work by the Tavistock shows, this is not true. Blockers don’t improve mental health outcomes at all, and indeed the focus on avoiding the development of secondary sex characteristics may even be creating distress.

Additionally, such studies of mental health and suicidality are skewed both by sex differences and confounding comorbidities. Notably, girls are more likely to suffer poor mental health than boys, especially lesbian and bisexual girls. There are large numbers of co-presenting conditions, like eating disorders and self-harm - and it is specifically among girls that we are seeing a large rise in identifying as trans or non-binary.

The author says they have poor mental health because of discrimination and stigmatisation. However, another hypothesis might be that children are identifying as trans as a response to homophobia (as has been reported at the Tavistock), or - in the case of girls - as an escape from a highly sexualised culture of objectification, or experiencing social contagion in friendship groups as has been shown with eating disorders and self-harm in the past. Do they have poor mental health because they are trans, or do they identify as such in response to poor mental health and other social factors?

Separating out whether identifying as trans is a cause of or a response to such things is difficult, but statements like the above are reductive and simplistic. The author leaves no room for such alternative interpretations of the same evidence, which again falls into the whole polarised culture-war framing of the article. Such alternatives invariably are not given weight in pieces like this because they do not fit that narrative.

Removing these treatments is to deny life.

And here is the crux of it - the emotional blackmail. The only thing that could possibly justify the risk of unnecessarily sterilising children is the threat of death.

Moreover, whereas the bills focus on medical treatments, the care trans youth receive is far wider in scope. Those seeking care typically also see social workers and psychiatrists, and much of health providers' work involves listening, talking, and setting up support in their families, schools, and communities. Health providers also discuss with them the idea that gender is something we “do” in social practice and can take many forms.

I struggle to see what the point of this paragraph is. If wider care and therapy are not under threat, why mention them? If the focus of legislation is on medical interventions, then talking about other forms of care is irrelevant. If people are arguing for less medical intervention and more of these wider social measures, then what is the author taking issue with?

Indeed, some choose social transition without medical treatment, and it is useful to remember that the notion of gender dysphoria perpetuates the historical pathologisation of gender diversity. Challenging the current social construction of male–female will undoubtedly ease trans youths' lives, reducing the pressure of rigid definitions. But alongside these social aspects is a pressing need for medical care.

This is pure doublespeak. What is more pathologising of gender diversity than the medication of children who display it, to “fix” their bodies so that they match their expression?

It is precisely the opposition to the pathologisation of gender nonconformity that is at the heart of many progressive objections to the current treatment regime.

We would agree that encouraging children to express themselves however they like is the aim - but we argue that telling them that they need to somehow “correct” their bodies in order to do this is a regressive step. You cannot literally change sex, and telling young children that you can, or connecting such things to stereotypical dress and behaviour and ephemeral feelings is so bizarre that I am still staggered as to how prevalent such a conservative idea is among supposed “progressives”.

Indeed, the idea that you can literally change your sex in this way also means that you can literally change your sexuality. With the right treatment, apparently a gay child becomes the straight one they truly were all along. Can the author really not see how some gay and lesbian people might be appalled by such measures? Might see such interventions as conversion therapy?

This editorial is partisan and polarising. It relies on limited or questionable evidence, does not consider the full range of contradictory evidence, and focuses on a narrow - and false - political framing of a complex and wide-ranging issue. It does nothing more than provide superficial legitimacy and ammunition to a particular political stance, rather than any sort of informative or open assessment of the evidence or genuine criticism.

As such, it is no different to 99% of what is written on this subject, but I do feel that The Lancet ought to aspire to more.

5 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

Masha Gessen, Interview: Judith Butler Wants Us To Reshape Our Rage, The New Yorker (February 9, 2020)

Masha Gessen: In this new book, you propose not just an argument for nonviolence as a tactic but as an entirely different way of thinking about who we are.

Judith Butler: We are used to thinking strategically and instrumentally about questions of violence and nonviolence. I think there is a difference between acting as an individual or a group, deciding, “Nonviolence is the best way to achieve our goal,” and seeking to make a nonviolent world—or a less violent world, which is probably more practical. I’m not a completely crazy idealist who would say, “There’s no situation in which I would commit an act of violence.” I’m trying to shift the question to “What kind of world is it that we seek to build together?” Some of my friends on the left believe that violent tactics are the way to produce the world they want. They think that the violence falls away when the results they want are realized. But they’ve just issued more violence into the world.

Masha Gessen: You begin with a critique of individualism “as the basis of ethics and politics alike.” Why is that the starting point?

Judith Butler: In my experience, the most powerful argument against violence has been grounded in the notion that, when I do violence to another human being, I also do violence to myself, because my life is bound up with this other life. Most people who are formed within the liberal individualist tradition really understand themselves as bounded creatures who are radically separate from other lives. There are relational perspectives that would challenge that point of departure, and ecological perspectives as well.

Masha Gessen: And you point out that in the liberal individualist way of thinking, the individual is always an adult male in his prime, who, just at this particular moment when we encounter him, happens to have no needs and dependencies that would bind him to others.

Judith Butler: That model of the individual is comic, in a way, but also lethal. The goal is to overcome the formative and dependent stages of life to emerge, separate, and individuate—and then you become this self-standing individual. That’s a translation from German. They say selbstständig, implying that you stand on your own. But who actually stands on their own? We are all, if we stand, supported by any number of things. Even coming to see you today—the pavement allowed me to move, and so did my shoes, my orthotics, and the long hours spent by my physical therapist. His labor is in my walk, as it were. I wouldn’t have been able to get here without any of those wonderful technologies and supporting relations. Acknowledging dependency as a condition of who any of us happens to be is difficult enough. But the larger task is to affirm social and ecological interdependence, which is regularly misrecognized as well. If we were to rethink ourselves as social creatures who are fundamentally dependent upon one another—and there’s no shame, no humiliation, no “feminization” in that—I think that we would treat each other differently, because our very conception of self would not be defined by individual self-interest.

Masha Gessen: You have written before about the concept of grievability, and it is an important idea in this book. Can you talk about it?

Judith Butler: You know when I think it started for me? Here in the United States, during the aids crisis, when it became clear that many people were losing their lovers and not receiving adequate recognition for that loss. In many cases, people would go home to their families and try to explain their loss, or be unable to go home to their families or workplaces and try to explain their loss. The loss was not recognized, and it was not marked, which means that it was treated as if it were no loss. Of course, that follows from the fact that the love they lived was also treated as if it were no love. That puts you into what Freud called melancholia. In contemporary terms, it is a version of depression, even as it admits of manic forms—but not just individual depression but shared melancholia. It enraged me then, as it does now, that some lives were considered to be more worthy of grieving publicly than others, depending on the status and recognizability of those persons and their relations. And that came home to me in a different way in the aftermath of 9/11, when it was very clear that certain lives could be highly memorialized in the newspapers and others could not. Those who were openly mourned tended to lead lives whose value was measured by whether they had property, education, whether they were married and had a dog and some children. The traditional heterosexual frame became the condition of possibility for public mourning.

Masha Gessen: You are referring to the twenty-five hundred mini-obituaries in the Times, right?

Judith Butler: Yes. It was rather amazing the way that the undocumented were not really openly and publicly mourned through those obituaries, and a lot of gay and lesbian people were mourned in a shadowy way or not at all. They fell into the dustbin of the unmournable or the ungrievable. We can also see this in broader public policies. There are those for whom health insurance is so precious that it is publicly assumed that it can never be taken away, and others who remain without coverage, who cannot afford the premiums that would increase their chances of living—their lives are of no consequence to those who oppose health care for all. Certain lives are considered more grievable. We have to get beyond the idea of calculating the value of lives, in order to arrive at a different, more radical idea of social equality.

Masha Gessen: You write about the militant potential of mourning.

Judith Butler: It’s something that can happen, though it doesn’t always happen. Black Lives Matter emerged from mourning. Douglas Crimp, the great art historian and theorist, reflected on mourning and militancy in an important essay by that name.

Masha Gessen: In “The Force of Nonviolence,” you repeatedly stress the importance of counter-realism, even an “ethical obligation” to be unrealistic. Can you explain that?

Judith Butler: Take the example of electability. If one takes the view that it is simply not realistic that a woman can be elected President, one speaks in a way that seems both practical and knowing. As a prediction, it may be true, or it may be shifting as we speak. But the claim that it is not realistic confirms that very idea of reality and gives it further power over our beliefs and expectations. If “that is just the way the world is,” even though we wish it were different, then we concede the intractability of that version of reality. We’ve said such “realistic” things about gay marriage before it became a reality. We said it years ago about a black President. We’ve said it about many things in this world, about tyrannical or authoritarian regimes we never thought would come down. To stay within the framework of Realpolitik is, I think, to accept a closing down of horizons, a way to seem “cool” and skeptical at the expense of radical hope and aspiration. Sometimes you have to imagine in a radical way that makes you seem a little crazy, that puts you in an embarrassing light, in order to open up a possibility that others have already closed down with their knowing realism. I’m prepared to be mocked and dismissed for defending nonviolence in the way that I do. It might be understood as one of the most profoundly unrealistic positions you could hold in this life. But when I ask people whether they would want to live in a world in which no one takes that position, they say that that would be terrible.

Masha Gessen: I want to challenge your examples a little bit. The electability issue can be argued not from the point of view of counter-realism but by saying, “Your view of reality is limited. It doesn’t take into account the number of women voters, or the number of women who were elected in the midterms.” Same with gay marriage--people who didn’t believe it was possible simply didn’t realize what a huge shift in social attitudes had occurred between generations. In a sense, those are easier arguments than the one I think you are making, which is, “You might be right about reality, but this is not a reality we should be willing to accept.”

Judith Butler: I am talking about how the term “reality” functions in social-political discourse. Sometimes “reality” is used to debunk as childish or unknowledgeable points of view that actually are holding out a more radical possibility of equality or freedom or democracy or justice, which means stepping out of a settled understanding. We see how socialist ideals, for instance, are dismissed as “fanciful” in the current election. I find that the dismissive form of realism is guarding those borders and shutting down those horizons of possibility. It reminds me of parents who say, “Oh, you’re gay . . .” or “Oh, you’re trans—well, of course I accept you, but it’s going to be a very hard life.” Instead of saying, ��This is a new world, and we are going to build it together, and you’re going to have my full support.”

Masha Gessen: On the other hand, I have been accused by my kids of not understanding how the world works—for rejecting what’s broadly understood to be the way things are. Don’t we also have a responsibility to acknowledge the hardships kids face?

Judith Butler: If the terms of their struggle and their suffering are the ones that they bring to you from their experience, then, yes, of course. But if you impose it on them before they even had a chance to live, that’s not so good.

Masha Gessen: Let’s talk about your approach to nonviolence as a matter not of individual morality but of a social philosophy of living.

Judith Butler: Most of the time, when we ask moral questions—like “What would you do?” or “How would you conduct yourself, and how would you justify your actions?” if such-and-such were the case—it’s framed as a hypothetical in which one person is offering a justification to another person, with the aim of taking individual responsibility for a potential action. That way of thinking rests on the notion that individual deliberation is at the core of moral action. Of course, to some degree it is, but we do not think critically about the individual. I am seeking to shift the question of nonviolence into a question of social obligations but also to suggest that probing social relationality will give us some clues about what a different ethical framework would be. What do we owe those with whom we inhabit the earth? And what do we owe the earth, as well, while we’re at it? And why do we owe people or other living creatures that concern? Why do we owe them regard for life or a commitment to a nonviolent relationship? Our interdependency serves as the basis of our ethical obligations to one another. When we strike at one another, we strike at that very bond. Many social psychologists will tell us that certain social bonds are consolidated through violence, and those tend to be group bonds, including nationalism and racism. If you’re part of a group that engages in violence and feels that the bonds of your connection to one another are fortified through that violence, that presumes that the group you’re targeting is destroyable and dispensable, and who you are is only negatively related to who they are. That’s also a way of saying that certain lives are more valuable than others. But what would it mean to live in a world of radical equality? My argument is that then we cannot kill one another, we cannot do violence to one another, we cannot abandon each other’s lives.

Masha Gessen: And this is where your critique of self-defense comes in.

Judith Butler: Don’t get me wrong--I’ve been trained in self-defense. I’m very grateful for that early training. But I’ve always wondered what that self is that we’re defending. Many people have pointed out that only certain people, in courts of law, are permitted to argue self-defense, and others very rarely are. We know that white men can protect themselves and their property and wield force in self-defense much more easily than black and brown people can. Who has the kind of self that is recognized by the law and the public as worthy of self-defense? If I think of myself not just as this bounded individual but as fundamentally related to others, then I locate this self in those relations. In that case, the self I am trying to defend is not just me but all those relations that define and sustain me, and those relations can, and should be, extended indefinitely beyond local units like family and community. If the self I’m trying to defend is also in some sense related to the person I’m tempted to kill, I have to make sure not to do violence to that relation, because that’s also me. One could go further--I’m also attacking myself by attacking that person, since I am breaking a social bond that we have between us. The problem of nonviolence looks different if you see it that way.

Masha Gessen: In a couple of places in the book, you say that nonviolence is not an absolute principle, or that you’re not arguing that no one has the right to self-defense—you are just suggesting a new set of guiding principles. I found myself a little disappointed every time you make that caveat. Does it not weaken your argument when you say, “I’m arguing against self-defense, but I’m not saying that no one has a right to self-defense”?

Judith Butler: If I were giving a rational justification for nonviolence as a position, which would make me into a much more proper philosopher than I am—or wish to be—then it would make sense to rule out all exceptions. But we don’t need a new rational justification for nonviolence. We actually need to pose the question of violence and nonviolence within a different framework, where the question is not “What ought I to do?” but “Who am I in relation to others, and how do I understand that relationship?” Once social equality becomes the framework, I’m not sure we are deliberating as individuals trying to come up with a fully rational position, consistent and complete and comprehensive for all circumstances. We might then approach the world in a way that would make violence less likely, that would allow us to think about how to live together given our anger and our aggression, our murderous wishes—how to live together and to make a commitment to that, outside of the boundaries of community or the boundaries of the nation. I think that that’s a way of thinking, an ethos—I guess I would use that word, “ethos,” as something that would be more important to me than a fully rational system that is constantly confounded by exceptions.

Masha Gessen: And would it be correct to say that you are also asking us not to adopt this new framework individually but actually to rethink together with others—that adopting this frame requires doing it in an interdependent way?

Judith Butler: I think so. We would need to develop political practices to make decisions about how to live together less violently. We have to be able to identify institutional modes of violence, including prisons and the carceral state, that are too often taken for granted and not recognized as violent. It’s a question of bringing out in clear terms those institutions and sets of policies that regularly make these kinds of distinctions between valuable and non-valuable lives.

Masha Gessen: You talk about nonviolence, rather unexpectedly, as a force, and even use words like “militant” and “aggressive.” Can you explain how they go together?

Judith Butler: I think many positions assume that nonviolence involves inhabiting the peaceful region of the soul, where you are supposed to rid yourself of violent feelings or wishes or fantasy. But what interests me is cultivating aggression into forms of conduct that can be effective without being destructive.

Masha Gessen: How do you define the boundary of what is violence?

Judith Butler: The physical blow cannot be the only model for thinking about what violence is. Anything that jeopardizes the lives of others through explicit policy or through negligence—and that would include all kinds of public policies or state policies—are practices of institutional or systemic violence. Prisons are the most persistent form of systemic violence regularly accepted as a necessary reality. We can think about contemporary borders and detention centers as clear institutions of violence. These violent institutions claim that they are seeking to make society less violent, or that borders keep violent people out. We have to be careful in thinking about how “violence” is used in these kinds of justifications. Once those targeted with violence are identified with violence, then violent institutions can say, “The violence is over there, not here,” and inflict injury as they wish. People in the world have every reason to be in a state of total rage. What we do with that rage together is important. Rage can be crafted—it’s sort of an art form of politics. The significance of nonviolence is not to be found in our most pacific moments but precisely when revenge makes perfect sense.

Masha Gessen: What kinds of situations are those?

Judith Butler: If you’re someone whose family has been murdered, or if you’re part of a community that has been violently uprooted from your homes. In the midst of feeling that rage, one can also work with others to find that other way, and I see that happening in nonviolent movements. I see it happening in Black Lives Matter. I think the feminist movement is very strongly nonviolent—it very rarely gets put in that category, but most of its activities are nonviolent, especially the struggle against sexual violence. There are nonviolent groups in Palestine fighting colonization, and anticolonial struggles have offered many of the most important nonviolent movements, including Gandhi’s resistance to British colonialism. Antiwar protests are almost by definition nonviolent.

Masha Gessen: One of the most striking passages in the book is about what you call “the contagious sense of the uninhibited satisfactions of sadism.” You write about the appeal of blatant and indifferent destructiveness. What did you have in mind when you wrote those phrases?

Judith Butler: It’s unclear whether Trump is watching Netanyahu and Erdoğan, whether anyone is watching Bolsonaro, whether Bolsonaro is watching Putin, but I think there are some contagious effects. A leader can defy the laws of his own country and test to see how much power he can take. He can imprison dissenters and inflict violence on neighboring regions. He can block migrants from certain countries or religions. He can kill them at a moment’s notice. Many people are excited by this kind of exercise of power, its unchecked quality, and they want in their own lives to free up their aggressive speech and action without any checks--no shame, no legal repercussions. They have this leader who models that freedom. The sadism intensifies and accelerates I think, as many people do, that Trump has licensed the overt violence of white supremacy and also unleashed police violence by suspending any sense of constraint. Many people thrill to see embodied in their government leader a will to destruction that is uninhibited, invoking a kind of moral sadism as its perverse justification. It’s going to be up to us to see if people can thrill to something else.

Masha Gessen: That goes back to my question about where the boundary of violence lies. For example, can you describe Trump’s speech acts as violence? He hasn’t himself stopped anybody at the border or shot anyone in a mosque.

Judith Butler: Executive speech acts have the power to stop people, so his speech acts do stop people at the border. The executive order is a weird speech act, but he does position himself as a quasi king or sovereign who can make policy through simply uttering certain words.

Masha Gessen: Or tweeting.

Judith Butler: The tweet acts as an incitation but also as a virtual attack with consequences; it gives public license to violence. He models a kind of entitlement that positions him above the law. Those who support him, even love him, want to live in that zone with him. He is a sovereign unchecked by the rule of law he represents, and many think that is the most free and courageous kind of liberation. But it is liberation from all social obligation, a self-aggrandizing sovereignty of the individual.

Masha Gessen: You describe this current moment rather beautifully in the book as a “politically consequential form of phantasmagoria.”

Judith Butler: If we think about the cases of police violence against black women, men, and children who are unarmed, or are actually running away, or sleeping on the couch, or completely constrained and saying that they cannot breathe, we would reasonably suppose that the manifest violence and injustice of these killings is evident. Yet there are ways of seeing those very videos that document police violence where the black person is identified as the one who is about to commit some terribly violent act. How could anyone be persuaded of that? What are the conditions of persuasion such that a lawyer could make that argument, on the basis of video documentation, and have a jury or judge accept that view? The only way we can imagine that is if we understand potential violence to be something that black people carry in them as part of their blackness. It has been shocking to see juries and judges and police investigators exonerate police time and again, when it would seem—to many of us, at least—that these were cases of unprovoked, deadly violence. So I understand it as a kind of racial phantasmagoria.

Masha Gessen: Just to be clear, you’re not saying that these juries saw violence being perpetrated against somebody nonviolent and decided to let the perpetrator off. You’re saying that they actually perceived violence--in the radically subjugated black body, or the radically constrained black body, or the black body that’s running with fear away from some officer who is threatening them with violence. And if you’re a jury—especially a white jury that thinks it’s perfectly reasonable to imagine that a black person, even under extreme restraint, could leap up and kill you in a flash—that’s phantasmagoria. It’s not individual psychopathology but a shared phantasmatic scene.

Masha Gessen: How did this book come about?

Judith Butler: I have been working on this topic for a while. It’s linked to the problem of grievability, to human rights, to boycott politics, to thinking about nonviolent modes of resistance. But, also, some of my allies on the left were pretty sure that, when Trump was elected, we were living in a time of fascism that required a violent overthrow or a violent set of resistance tactics, citing the resistance to Nazism in Europe and Fascism in Italy and Spain. Some groups were affirming destruction rather than trying to build new alliances based on a new analysis of our times, one that would eventually be strong enough to oppose this dangerous current trend of authoritarian, neo-Fascist rule.

Masha Gessen: Can you give some examples of what you see as affirming destruction?

Judith Butler: At a very simple level--getting into physical fights with fascists who come to provoke you. Or destruction of storefronts because capitalism has to be brought to its knees, as has happened during Occupy and anti-fascist protests in the Bay Area, even if those storefronts belong to black people who struggled to establish those businesses. When I was in Chile last April, I was struck by the fact that the feminist movement was at the forefront of the left, and it made a huge difference in thinking about tactics, strategies, and aims. In the U.S., I think that some men who always saw feminism as a secondary issue feel much freer to voice their anti-feminism in the context of a renewed interest in socialism. Of course, it does not have to go that way, but I worry about a return to the framework of primary and secondary impressions. Many social movements fought against that for decades.

Masha Gessen: You have faced violence, and I know there are some countries you no longer feel safe travelling to. What has happened?

Judith Butler: There are usually two issues, Palestine or gender. I have come to understand in what places which issue is controversial. The anti-“gender ideology” movement has spread throughout Latin America, affecting national elections and targeting sexual and gender minorities. Those who work on gender are often maligned as “diabolical” or “demons.” The image of the devil is used a lot, which is very hard on me for many reasons, partly because it feels anti-Semitic. Sometimes they treat me as trans, or they can’t decide whether I’m trans or lesbian or whatever, and they credit my work from thirty years ago as introducing this idea of gender, when even cursory research will show that the category has been operative since the nineteen-fifties.

Masha Gessen: How do you know that they see you as trans?

Judith Butler: In Brazil, they put a pink bra on the effigy that they made of me.

Masha Gessen: There was an effigy?

Judith Butler: Yes, and they burned that effigy.

Masha Gessen: “Pink bra” wouldn’t seem to be the headline of that story?

Judith Butler: But the idea was that the bra would be incongruent with who I am, so they were assuming a more masculine core, and the pink bra would have been a way to portray me in drag. That was kind of interesting. It was kind of horrible, too.

Masha Gessen: Did you witness it physically?

Judith Butler: I was protected inside a cultural center, and there were crowds outside. I am glad to say that the crowd opposing the right-wing Christians was much larger.

Masha Gessen: Are you scared?

Judith Butler: I was scared. I had a really good bodyguard, who remains my friend. But I wasn’t allowed to walk the streets on my own.

Masha Gessen: Let’s review this “gender ideology” idea, because not everyone is familiar with this phenomenon.

Judith Butler: It’s huge.

Masha Gessen: It’s the idea, promoted by groups affiliated with Catholic, evangelical, and Eastern Orthodox churches, that a Jewish Marxist–Frankfurt School–Judith Butler conspiracy has hatched a plot to destroy the family by questioning the immutability of sex roles, and this will lead white people to extinction.

Judith Butler: They are taking the idea of the performativity of gender to mean that we’re all free to choose our gender as we wish and that there is no natural sex. They see it as an attack on both the God-given character of male and female and the ostensibly natural social form in which they join each other—heterosexual marriage. But, sometimes, by “gender” they simply mean gender equality, which, for them, is destroying the family, which presumes that the family has a necessary hierarchy in which men hold power. They also understand “gender” as trans rights, gay rights, and as gay equality under the law. Gay marriage is particularly terrifying to them and seen as a threat to “the family,” and gay and lesbian adoption is understood to involve the molestation of children. They imagine that those of us who belong to this “gender movement,” as they put it, have no restrictions on what we will do, that we represent and promote unchecked sexual freedom, which leads to pedophilia. It is all very frightening, and it has been successful in threatening scholars and, in some cases, shutting down programs. There is also an active resistance against them, and I am now part of that.

Masha Gessen: How long has this been going on, this particular stage of your existence in the world?

Judith Butler: The Pontifical Council for the Family, led by Pope Francis before his elevation, published papers against “gender” in 2000. I wrote briefly about that but could not imagine then that it would become a well-financed campaign throughout the world. It started to affect my life in 2012 or ’13.

Masha Gessen: And, aside from finding it, as I can tell, sometimes a little bit amusing—

Judith Butler: Oh, no, it’s terrifying. I have feared for my life a few times, and scholars in Bahia and other parts of the world have been threatened with violence. Even the clip you saw online was incomplete—they, the gender-ideology people, made it and circulated it because they were apparently proud of themselves. What they didn’t show is the woman who came after me, running with a cart, as I went to the security checkpoint. She was about to shove me with that metal cart when some young man with a backpack came out of a store and actually interposed his body between the cart and me, and he ended up on the floor, in a physical fight with her, which I saw as I was going up the elevator. I looked back, and I thought, This guy has sacrificed his physical well-being for me. I don’t know who he is to this day. I would like to find this person and thank him.

Masha Gessen: Is that the only time you have faced physical violence?

Judith Butler: Some people in Switzerland, too, were up in arms about Biblical authority on the sexes. This was probably about four or five years ago.

Masha Gessen: Do you see this at all as an indication of your influence?

Judith Butler: It seems like a terrible indication of my influence, in the sense that they don’t actually know my work or what I was trying to say. I see that they’re very frightened, for many reasons, but I don’t think this shows my influence.

Masha Gessen: And, other than that, how are you feeling about your work in the world?

Judith Butler: I’m working collaboratively with people, and I like that more than being an individual author or public figure who goes around and proclaims things. My connection with the women’s movement in Latin America has been important to me, and I work with a number of people in gender studies throughout Europe. Leaving this country allows me to get a new perspective, to see what is local and limited about U.S. political discourse, and I suppose my work tends to be more transnational now than it used to be.

Masha Gessen: What is the work in Latin America?

Judith Butler: I have been part of a grant from the Mellon Foundation to organize an international consortium of critical-theory programs. Critical theory is understood not only in the Frankfurt School sense but as theoretical reflection that’s trying to grasp the world we live in, to think about and transform that world in ways that overcome a range of oppressions and inequalities. We often connect with academic and activist movements and reflect on social movements together. The Ni Una Menos—“Not One Less”—grassroots movement fighting violence against women, in particular, has been really impressive to me. Sometimes the movement can bring one [million] to three million people out into the streets. They work very deliberatively and collectively, through public assemblies and strikes. They’re very fierce and smart, and they are also hopeful in the midst of grim realities. I am also working with friends in Europe and elsewhere who are trying to defend gender-studies programs against closure—we call ourselves the Gender International.

Masha Gessen: Are you still involved in Palestine work?

Judith Butler: It’s not as central in my life as it was, but all my commitments are still there. Israel has banned me from entry, because of my support for B.D.S. [the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement], so it is hard to sustain alliances in Palestine—Israel controls all those borders. I work with Jewish Voice for Peace. I’m particularly worried about Trump’s new anti-Semitism doctrine, which seems to suggest that every Jew truly or ultimately is a citizen of the state of Israel. And that means that any critique of Israel can be called anti-Semitic, since Trump—and Netanyahu—want to say that the state of Israel represents all Jewish people. This is a terrible reduction of what Jewish life has been, historically and in the present, but, most frighteningly, the new anti-Semitism policy will license the suppression of Palestinian student organizations on campus as well as research in Middle East studies. I have some deep fears about that, as should anyone who cares about state involvement in the suppression of knowledge and the importance of nonviolent forms of advocacy for those who have suffered dispossession, violence, and injustice.

#nonviolence#violence#interview#judith butler#lgbt#gender#controversy#human rights#palestine#discrimination#critique#individualism#anti-individualism#The Way We Live Now#grief#politics#injustice#mourning#black lives matter#activism#douglas crimp#self-defense#antifascism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Four Crucial Queer Survival Tips for 2019

Elizabeth Duck-Chong

As we approach this new annum and everything that lies in store, instead of thinking about the ephemera one could manifest into being, I want to ask how we create the space to make our queer love and joy stand out and shine.

As the calendar turns over into the new year, it’s common to see people talking about their plans, resolutions, and the high hopes they have for the next twelve months. However, it's not news to say that it's a scary time to be out in the world as a queer person, and so each coming year can feel as exhausting or terrifying to think about as it might feel exuberant or hopeful.

We live in a period where we are simultaneously the most visible we have ever been, but also the most legislated against, and the most condemned. No wonder it can feel really tough, like being out and proud is something that other people are able to do, but maybe not you.

I'm not going to lie, there's a lot of things to be scared about, but I also believe there's so much to celebrate, and that we are so deeply worth fighting for. To lose some of the battles along the way doesn't mean we have to lose hope, and there's plenty of hope to go around. This century, this last year even, has shown more trans people are able to be out, proud and successful than ever before. Even as we speak, trans people are running for state office, writing brilliant tv, modeling in world-wide campaigns, writing award winning literature and more by the day! From athletes to academics to artists, and everything in between, we are living the best lives we ever have been able to, and supporting each other to do so.

Still, it can feel like a big tough world out there. As we approach this new annum and everything that lies in store, instead of thinking about the ephemera one could manifest into being, I want to ask how we create the space to make our queer love and joy stand out and shine.

Find your passion

Nothing breeds success like doing what we love. Whether you want to stream on Twitch or paint or get really good at dodgeball, practice makes perfect. Many years ago, a friend of mine said they liked a blog post I’d sent them and that I should write more, and now I'm here, writing this to you!

We live in a world that can make doing what we love, or what we want to do, really difficult, with many people just trying to get through our weeks and months with some love, some support and hopefully even some savings! Finding those shining moments in between all of our day to day, though, is where we can find who we are and who we want to be (and who knows, maybe find a career path or partner or realize a dream)! This may look like dragging a friend to a convention to connect with others, taking some free online classes and seeing what grabs you, joining a Facebook group or forum for your fandom or favorite author, or something else entirely! Even now, if a friend wants to take me to something I’ve never tried before, I like to give it a go because I might just find my new passion! There are so many things to do, and one of them might just be the coolest thing you’ve ever found.

Plan to allow yourself some real time and energy for your hobby. Organize that tabletop game with friends, that cross-continental musical jam session, or that poetry zine you've always wanted to start. It all flows onto the rest of our lives. Heck, do all of it at once, but just discover your loves, listen to them and give them time, patience and love.

Find your people

When the chips are down, I turn to community.

This big, messy word tries to sum up the complexity of all of us altogether, how we meet and fight and grow, but it only conveys the very surface of it — community is so big, so momentous, that the big picture is one of potential, and of hope. When I was barely out, I found my people in protest marches — getting changed into the skirts usually stuffed down the back of my dresser in public bathrooms before marching through the streets, shouting and singing with people who saw me wholly. Nowadays I commune in other ways: at dinner parties and bars, gigs and readings, and in so many places that younger me didn’t know was possible (and still, sometimes, at protest marches)!

Community may take many forms for you, from a forum of friends you've never met, swapping links and stories deep into the night, or a Gay Straight Alliance at your school or college, or a group of friends who don't really have words for your experiences yet, but share a love of each other and of the chance for discovery. Sometimes there are friends around us that may or may not one day come out to us, but who accept us all the same. Sometimes we find our people in totally new and different ways altogether. Whether it’s on Tumblr, Twitter, or forums like Scarleteen’s very own, there’s so much room online too for community-making, and in many cases those communities are already there and just waiting for someone just like you.

As an adult, I turn to my community in times of stress and struggle, group messaging my elders and friends, my lovers and my loved ones for advice, for help in a crisis, and to offer the same in kind. You may not know who your people are yet, or may want to figure out who you are before you find out who they may be, but I promise they are out there. If there's one thing I can guarantee about queers, it is that we are everywhere, sewn into the fabric of family and geographical place, waiting to be found.

Celebrate the difference

Of all the vast number of gender and sexual minorities that come under today's umbrella terms, or prefer to step out from under them, we are a broad group. That we keep talking about our ever-expanding acronym is a testament to the multitude of identities across which we celebrate both similarities and differences. From Pose to Pynk, Love Simon to Drag Race, Frank Ocean to Anoni, and Queerstories to Carmilla, we are creating work that showcases our lives with all the detail and difference we really exist within. In the span of my lifetime, the tools available to creators have shifted so radically, making the queer art that has always existed more widely available and knowable. I watch the people I love being able to create and publish their own blogs, photos, webcomics, TV, albums and EPs, illustrations and even full-length films, and having that work reflect how many wavelengths of color our rainbow contains!

When the bullies and bigots are at the door, one of the most beautiful weapons we have is to manifest and exist as our most real and wonderful selves — of all genders, backgrounds, wants, needs and desires. Our difference is our power, that we group together and say we are the same but also are so many things, and I truly believe that's what will change the world.

Create the joy

There's so much trying to keep us down right now, and sometimes it can be overwhelming. Taking the time to mourn, to sit with our struggle and understand the pain is so important, but so is taking the time to love, to celebrate and to live joyfully.

This may be starting with one thing each day, one little smile. As a teenager, I tried to find one beautiful thing every day, and wrote it down in a notebook. One day it would be a sunset, the next a carpet of beautiful grass, the next a friend's laughter. Through some real dark times I held onto sometimes just one thing at a time, but slowly it became easier, seeing the beauty and the light in everything, becoming a reflex. It’s a cliché, but one that let me hold onto something and imagine a better world I could be a part of.

Maybe for you it's playing a piece you love with one less mistake than last time, or rereading the latest chapter of your new favourite novel, or nailing that practice exam, or just getting a hug from a friend; joy comes in so many packages, and with time and practice we come to know the ones we can’t wait to unwrap.

It’s easy to get lost in how big the world can feel, and to be such a small part of it, but that is actually a blessing, allowing us to move through versions of ourselves until we find the ones that fit perfectly, and then come together with others until we form something far more visible, beautiful and powerful.

Have hope, because there is so, so much to hope for, and I believe that we will make that hope a reality we can live in together in 2019, and beyond.

queer

trans

new year

survival

LGBQTA

help

support

community

passion

difference

joy

working it out

self-care

survive

youth

Sexual Identity

Gender

Etc

from MeetPositives SM Feed 4 http://bit.ly/2R5zLM7

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Renew the `Tude

For a long time, I have had people tell me that I had a bad attitude. It was such a force in my life, that for a number of years I thought that I was inherently mistaken about everything. Nowadays, we call it gaslighting, and I have had to deal with it from my older brother (including a Thanksgiving where everything he said was prefaced by the phrase “Well, actually...”), by exes and roommates, and it just keeps going.

Part of the problem might be that I listen to other people too much. I got in trouble as a kid, and the way I avoided that was listening to those in charge, so that I did not step on their toes.

Is it any wonder that by my freshman year off college my girlfriend was cheating on me, my roommate was having sex on my bed whenever I went home for the weekend, and I had ulcers in my throat.

My roommate at the time told me that I didn’t have a positive enough attitude, and my girlfriend told me that I wasn’t manly enough. But it was not my attitude that was the problem, but the fact that I did not like being lied to and mistreated those ways.