#étienne macdonald

Note

A fun little ask: the Marshalate is informed there is cake in the break room. How do each of them react?

Who ever you are, thank you for this sweet little question and I apologise for my late response. 🙈💕

I have ideas for some of them, however I am **not** aware of the maréchals eating habits so any input is welcome here. Also, I don't know all of the marshals well enough but I will try to include as many as possible. Don’t expect any historical accuracy in this.

See this post as a very big headcanon and as one ongoing story where I am going to try to mimic the marshals characters and miserably fail.

Shall we begin? :D

Les Maréchals and cake

Berthier would hear about it and quietly get excited by the idea of having a nice little piece of cake, just for him to be too busy with everything so that he isn't able to leave his desk. Either this or someone (probably one of his adcs) would be nice enough to get for Berthier his piece of cake.

Murat: You bet he is one of the first ones to look at this cake. His reaction might depend on how the cake looks. If it's a huge cake with a lot of golden details, Murat will carry it around so everyone admires this phenomenal cake because it deserves to be looked at.

Augerau and Masséna wonder why there is such a fancy a cake in the break room in the first place and who might have put it there. Augerau asks Masséna with a low voice: “How much money do you want to bet on the cake being poisoned?” Before Masséna is able to answer, Lannes enters the scene.

Lannes runs after Murat with the cake knife demanding to finally get his damn piece of this cake while Murat can't make himself to cut it because this cake is “so damn beautiful that it would be a waste to eat it.” This little game goes on for a minute or two until the other marshals grow impatient, one of them being Ney.

Ney who is known for his hotheadedness tries to save this cake from a disaster aaaaand fails. :) The three of them dispute over who is the actual culprit of this mess.

L: Murat, what have you done?

M: I have done nothing. You followed me with a knife.

N: You let the cake fall.

M: You intervened in my business with Lannes.

The cake has fallen to the ground as Davout, Suchet and Macdonald watched. “Aaand here goes the cake”, Macdonald says; “At least the floor was able to taste it.”

Suchet asks: “What do you think was its flavour?”

”Chocolate vanilla.” Davout answers. After a moment of silence, he adds. “Soult has a good recipe.”

Mortier walks in, seeing how Lannes, Murat and Ney are loudly disputing while Masséna and Augerau get themselves black coffee and Davout, Suchet and Macdonald talking. Lefebvre who was walking right behind Mortier gestures him to move away from the door so he can get into the break room: “What is going on?”

Suchet: “We found a cake-“ Davout interrupts him: “We found a chocolate vanilla cake which we don’t know how it got here or if it was poisoned and now it’s inedible because his royal highness, the King of Naples, made it fall.”

Murat shouts from the back: “I didn’t let it fall.”

Lannes: “Oh, you did.”

Lefebvre offers a solution like the good fatherly figure he is: “Do you still want cake? We could bake a new cake, messieurs.”

Davout replies: “This sounds like a smart idea, Monsieur. Maréchal Soult knows an excellent recipe.”

Lefebvre: “Ahh, excellent. Where is our maréchal?”

Mortier: “He is in his office.”

“Then this where our journey goes next.” Lefebvre slams the door open and accidentally hits Oudinot. “Ah, Monsieur, my apologies. If I had known you were there, I wouldn’t have slammed the door as hard as I did. Are you alright? Yes? Until the next time then.”

Davout walks up to his friend to make sure how Oudinot is doing and explains to him in the meanwhile what is going on and also promises Oudinot to bring him a piece of the cake they are going to bake.

Lefebvre takes the lead and walks straight to Soult’s office while Davout and Mortier follow him. Suchet decides to stay behind while Macdonald thinks about it.

Lefebvre knocks on Soult’s office door: “Monsieur, le maréchal? Are you here?” *Lefebvre knocks again with his energetic manner.* “Monsieur, le maréchal, it’s me, Lefebvre. Open the door!*

Soult opens the door with his usual unimpressed demeaner: Hm?

Lefebvre: “Excusez-moi, mon maréchal, I heard you have a recipe for a delicious cake?”

Soult: Cake? What cake?

Davout: The chocolate vanilla one… the one you baked for your daughter Hortense’s birthday. The delicious one.

Soult: Ah, yeah. That one. What of it?

Mortier: We would like to bake this cake, which is why we want to ask if you mind us borrowing the recipe?

Soult stares at his co-maréchals for a second, he shuts the door, opens it again with a piece of paper in his hand which he gives to Lefebvre. “Here. Is there anything else you need?”

Macdonald who decided to join the baking group walks up to them and asks Soult: “Would you mind to lend us your baking equipment?”

- “No. Have a nice day.”

Soult shuts his door while Lefebvre shouts: “Thank you for your help, Monsieur Soult.”

Macdonald asks: “What are we going to do now?”

“We are going to bake the cake now, my good friend”, Davout answers.

Mac: “Where? Where do you want us to bake the cake? Do we have the right ingredients?”

D: In the kitchen and I don’t see why we shouldn’t have the ingredients.

Macdonald looks at Davout with suspicious eyes about the matter if they are going to manage to bake this cake…

The group of maréchals appear in the imperial kitchen where they start to gather the right ingredients. While the group is busy with the preparations, les maréchals Pérignon and Sérurier appear, wondering what is going on. As Lefebvre is explaining these two their baking journey up until now, Pérignon and Sérurier decide to join them: “A cake made by maréchals for maréchals.”

What could possibly go wrong with two additional heads in the kitchen? As it turns out: Everything.

Pérignon and Sérurier manage to overdo the cake by confusing salt with sugar. The cake tastes salty, the icing itself is fine because it was made by Davout who religiously followed Soult’s directions. In addition to that, monsieur Lefebvre manages to mix up usual paper with baking sheets.

Bernadotte walks into the kitchen as he sees his fellow maréchals working on their baking project. He comments on the scenery: “This is just pure chaos without any discipline, a chaos which can’t possibly create something edible.”

Davout replies “Well, have you ever baked anything in your miserable existence which you so call your life?”; to which Bernadotte says: “wELL, no, BUT-“

Davout continues: “Then get out of this room and give me my peace back or shut up.” Bernadotte decides to leave.

As Bernadotte is leaving, Jourdan walks right into the scene with an apple in his hand. A fire starts to break out in the oven and Jourdan, like the team player he is, turns and leaves this mess to his co-maréchals without saying one word.

Nothing is going as Davout had it planned. He sits in a corner, mourning this beautiful chocolate vanilla cake he had in mind. Macdonald sits right next to him with a spoon, telling him: “Well, at least the frosting you made yourself is delicious.”

Davout, completely shattered by the fact that he wasn’t able to make his desired chocolate vanilla cake, puts his face into his palms until a surprise visits the kitchen: It’s maréchal Soult. With a cake. A chocolate vanilla cake. A chocolate vanilla cake which is neither burnt nor oversalted. A chocolate vanilla cake according to the recipe. Next to Soult is Oudinot who cuts two pieces of the cake: one for himself and one for his good old friend, Louis Nicolas Davout.

After Soult, Ney and Lannes enter the kitchen. Ney silently takes a piece of Soult’s cake, saying nothing except a simple “thank you”. So do Macdonald and Mortier. Soult tolerates Ney’s presence. Lannes on the other hand goes straight to the oversalted and burnt cake which the older maréchals made and are also eating. Kellermann and Grouchy, as late to the party as ever, also go for Lefebvre’s bad cake while Soult’s good cake is still sitting there. Soult can’t hide his look of disgust.

At some point, Bessières and Murat join or rejoin retrospectively the scene, walking up to Soult’s cake. Bessières, as well mannered as he is, takes one piece of a cake to which Murat comments: “I know how much you like this lovely type of cake, Bessières, take a second piece.”

- “No”, Soult replies: “That’s not your cake. Take your piece and leave.”

Murat adds: “For whom are the other pieces then? I don’t see anybody who would possibly want to eat this gorgeous baked good. We want to eat your delicious creation of a fabulous cake.”

- “One piece each. You can give him your piece if you like to.”

Bessières interrupts the two: “I am content with my piece.”

Murat doesn’t listen to what Bessières says and continues his conversation with Soult: “My fellow maréchal, I don’t understand, why do you struggle so much with allowing somebody to have one additional piece of cake than the other ones?”

While Murat and Soult continue their dispute which leads to nowhere, one adc enters slowly the kitchen. He looks at Soult who recognises this man as one of Berthier’s adcs. He came to get a piece of cake for his marshal. Soult lets him take one of the few pieces left.

All of a sudden, Kellermann seems to be chocking on his salty cake piece. All the maréchals are gathering around him and in the chaos, the last few pieces of Soult’s cake fall to the ground. Soult looks at his cake or what’s left of it. One could argue that everyone who wanted to eat it was able to eat it. One could argue that these fallen pieces can be ignored and Soult could go on with his day never ever thinking about the pieces again. However, we are talking about maréchal Soult here who sees the art in baking. The love, the accuracy of it. Today he didn’t just bring cake to his fellow maréchals. Today he witnessed how some of them have no sense of dignity for what it means to be able to eat good food. Good cake. Soult is leaving the room, not bothered about Kellermann as he wouldn’t be able to help anyway. He is going to his wife, his Louise Berg, who asks him about his day. He tells her the whole of it. How he was surprised by his fellow maréchals who wanted to bake a cake. How he knew that they are going to mess up his recipe. How he baked that cake properly and how a part of it went to waste. “Some of them ate oversalted and burnt cake. Who eats bad cake? Who likes bad cake???”

Davout on the other hand was thankful for Soult. With a smile on his face, Davout enjoyed his so desired chocolate vanilla cake, unbothered by the event surrounding him.

The end. :)

#Napoleonic headcanon#headcanon#napoleonic#louis alexander berthier#joachim murat#charles pierre augerau#andré masséna#jean lannes#michel ney#louis nicolas davout#louis gabriel suchet#étienne macdonald#édouard mortier#nicolas charles oudinot#françois joseph lefebvre#jean baptiste bernadotte#jean baptiste bessières#jean baptiste jourdan#jean de dieu soult#louise berg soult#And the rest :)#i am too tired for this#i hope you like it#cake

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt:

The King of Naples, who during the retreat had shown a lot of energy, courage and calm, was not strong enough to bear the burden with which the Emperor had charged him. After Elbing, he no longer saw a way out, and, despairing of the reproaches he received daily from his brother-in-law about his retrograde march, fearing perhaps also, and with reason, that Napoleon would consent to the sacrifice of Naples in order to obtain peace, he abandoned the army and returned home.

#Joachim Murat#Louis-Nicolas Davout#Eugène de Beauharnais#Étienne Jacques Macdonald#Napoleonic wars#Napoleon's marshals#1812#memoirs#translations#blog

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

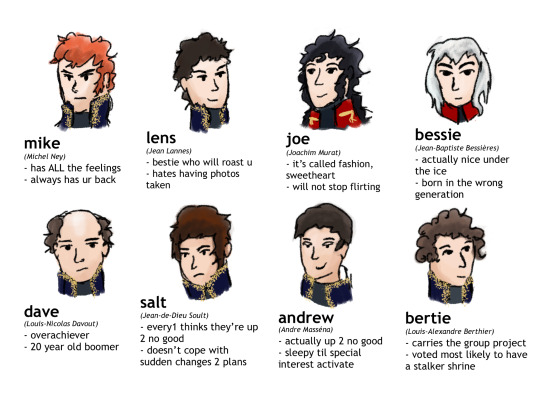

Tag Yourself: Unabridged Shitty Drawing Marshal of the Empire Edition

Yes All 26 Of Them + Bonus 2

drawn and compiled by yours truly, initial and probably inaccurate research assisted by Chet Jean-Paul Tee, additional research from Napoleon and his Marshals by A G MacDonnell, Swords Around A Throne by John R Elting and a bunch of other books and Wikipedia pages

captions under images

mike (Michel Ney)

- full of every emotion

- always has ur back

joe (Joachim Murat)

- it's called fashion sweetheart

- will not stop flirting

lens (Jean Lannes)

- bestie who will call u out on ur shit

- does not like their photo taken

bessie (Jean-Baptiste Bessieres)

- actually nice under the ice

- was born in the wrong generation

dave (Louis-Nicolas Davout)

- overachiever

- 20 year old boomer

salt (Jean-de-Dieu Soult)

- people think ur up to no good

- doesn’t cope with sudden changes 2 plans

andrew (Andre Massena)

- actually up to no good

- sleepy until special interest is activated

bertie (Louis-Alexandre Berthier)

- carries the group project

- voted most likely to make a stalker shrine

auggie (Pierre Augereau)

- shady past full of batshit stories

- will not stop swearing in the christian minecraft server

lefrank (François Joseph Lefebvre)

- dad friend

- in my day we walked to school uphill both ways

big mac (Étienne Macdonald)

- brutally honest

- won't let you borrow their charger even if they have 100%

gill (Guillaume Brune)

- love-hate relationship with group chats

- pretends not to care, checks social media every 2 minutes

ouchie (Nicholas Oudinot)

- needs to buy bandages in bulk

- a little aggro

pony (Józef Antoni Poniatowski)

- can't swim

- tries 2 hard to fit in, everyone secretly loves them anyway

grumpy (Emmanuel de Grouchy)

- can't find them when u need them

- complains about the music, never suggests alternatives

bernie (Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte)

- always talks about their other friendship group

- most successful, nobody knows how

monty (Auguste de Marmont)

- does not save u a seat

- causes drama and then lurks in the background

monch (Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey)

- last to leave the party

- dependable

morty (Édouard Mortier)

- everyone looks up 2 them literally and figuratively

- golden retriever friend

jordan (Jean-Baptiste Jourdan)

- volunteers other people for things

- has 20+ alarms but still oversleeps

kelly (François Christophe de Kellermann)

- old as balls but still got it

- waiting in the wings

gov (Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr)

- infuriatingly modest about their art skills

- thinks too much before they speak

perry (Catherine-Dominique de Pérignon)

- low-key rich, only buys things on sale

- “let’s order pizza” solution to everything

sachet (Louis-Gabriel Suchet)

- dependable friend who always brings snacks

- lowkey keeps the group together

cereal (Jean-Mathieu-Philibert Sérurier)

- unnervingly methodical and precise about fun

- will delete your social media after u die

vic (Claude Victor-Perrin)

- loves spicy food but can’t handle it

- says they're fine, not actually fine

Bonus!

june (Jean Andoche Junot)

- chaotic disaster bisexual

- will kill a man 4 their bestie

the rock (Géraud Duroc)

- keeps a tidy house

- mom friend with snacks

#napoleon’s marshals#napoleonic era#napoleonic shitposting#napoleonic wars#history shitposting#cadmus draws#I thought it would be funny if it was hand drawn#i had to draw these over a few weeks or else my RSI ridden fingers would explode#I will reblog this a few times because this is so stupid and I’m proud of this#yes chatgpt helped because I’m not actually familiar with most of the 26#ended up editing a lot of it but some entries are less based on history and more based on vibes#and as we know vibes are extremely accurate

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friends, enemies, comrades, Jacobins, Monarchist, Bonapartists, gather round. We have an important announcement:

The continent is beset with war. A tenacious general from Corsica has ignited conflict from Madrid to Moscow and made ancient dynasties tremble. Depending on your particular political leanings, this is either the triumph of a great man out of the chaos of The Terror, a betrayal of the values of the French Revolution, or the rule of the greatest upstart tyrant since Caesar.

But, our grand tournament is here to ask the most important question: Now that the flower of European nobility is arrayed on the battlefield in the sexiest uniforms that European history has yet produced (or indeed, may ever produce), who is the most fuckable?

The bracket is here: full bracket and just quadrant I

Want to nominate someone from the Western Hemisphere who was involved in the ever so sexy dismantling of the Spanish empire? (or the Portuguese or French American colonies as well) You can do it here

The People have created this list of nominees:

France:

Jean Lannes

Josephine de Beauharnais

Thérésa Tallien

Jean-Andoche Junot

Joseph Fouché

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand

Joachim Murat

Michel Ney

Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte (Charles XIV of Sweden)

Louis-Francois Lejeune

Pierre Jacques Étienne Cambrinne

Napoleon I

Marshal Louis-Gabriel Suchet

Jacques de Trobriand

Jean de dieu soult.

François-Étienne-Christophe Kellermann

17.Louis Davout

Pauline Bonaparte, Duchess of Guastalla

Eugène de Beauharnais

Jean-Baptiste Bessières

Antoine-Jean Gros

Jérôme Bonaparte

Andrea Masséna

Antoine Charles Louis de Lasalle

Germaine de Staël

Thomas-Alexandre Dumas

René de Traviere (The Purple Mask)

Claude Victor Perrin

Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr

François Joseph Lefebvre

Major Andre Cotard (Hornblower Series)

Edouard Mortier

Hippolyte Charles

Nicolas Charles Oudinot

Emmanuel de Grouchy

Pierre-Charles Villeneuve

Géraud Duroc

Georges Pontmercy (Les Mis)

Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont

Juliette Récamier

Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey

Louis-Alexandre Berthier

Étienne Jacques-Joseph-Alexandre Macdonald

Jean-Mathieu-Philibert Sérurier

Catherine Dominique de Pérignon

Guillaume Marie-Anne Brune

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan

Charles-Pierre Augereau

Auguste François-Marie de Colbert-Chabanais

England:

Richard Sharpe (The Sharpe Series)

Tom Pullings (Master and Commander)

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Jonathan Strange (Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell)

Captain Jack Aubrey (Aubrey/Maturin books)

Horatio Hornblower (the Hornblower Books)

William Laurence (The Temeraire Series)

Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey

Beau Brummell

Emma, Lady Hamilton

Benjamin Bathurst

Horatio Nelson

Admiral Edward Pellew

Sir Philip Bowes Vere Broke

Sidney Smith

Percy Smythe, 6th Viscount Strangford

George IV

Capt. Anthony Trumbull (The Pride and the Passion)

Barbara Childe (An Infamous Army)

Doctor Maturin (Aubrey/Maturin books)

William Pitt the Younger

Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry (Lord Castlereagh)

George Canning

Scotland:

Thomas Cochrane

Colquhoun Grant

Ireland:

Arthur O'Connor

Thomas Russell

Robert Emmet

Austria:

Klemens von Metternich

Friedrich Bianchi, Duke of Casalanza

Franz I/II

Archduke Karl

Marie Louise

Franz Grillparzer

Wilhelmine von Biron

Poland:

Wincenty Krasiński

Józef Antoni Poniatowski

Józef Zajączek

Maria Walewska

Władysław Franciszek Jabłonowski

Adam Jerzy Czartoryski

Antoni Amilkar Kosiński

Zofia Czartoryska-Zamoyska

Stanislaw Kurcyusz

Russia:

Alexander I Pavlovich

Alexander Andreevich Durov

Prince Andrei (War and Peace)

Pyotr Bagration

Mikhail Miloradovich

Levin August von Bennigsen

Pavel Stroganov

Empress Elizabeth Alexeievna

Karl Wilhelm von Toll

Dmitri Kuruta

Alexander Alexeevich Tuchkov

Barclay de Tolly

Fyodor Grigorevich Gogel

Ekaterina Pavlovna Bagration

Ippolit Kuragin (War and Peace)

Prussia:

Louise von Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Gebard von Blücher

Carl von Clausewitz

Frederick William III

Gerhard von Scharnhorst

Louis Ferdinand of Prussia

Friederike of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Alexander von Humboldt

Dorothea von Biron

The Netherlands:

Ida St Elme

Wiliam, Prince of Orange

The Papal States:

Pius VII

Portugal:

João Severiano Maciel da Costa

Spain:

Juan Martín Díez

José de Palafox

Inês Bilbatua (Goya's Ghosts)

Haiti:

Alexandre Pétion

Sardinia:

Vittorio Emanuele I

Lombardy:

Alessandro Manzoni

Denmark:

Frederik VI

Sweden:

Gustav IV Adolph

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

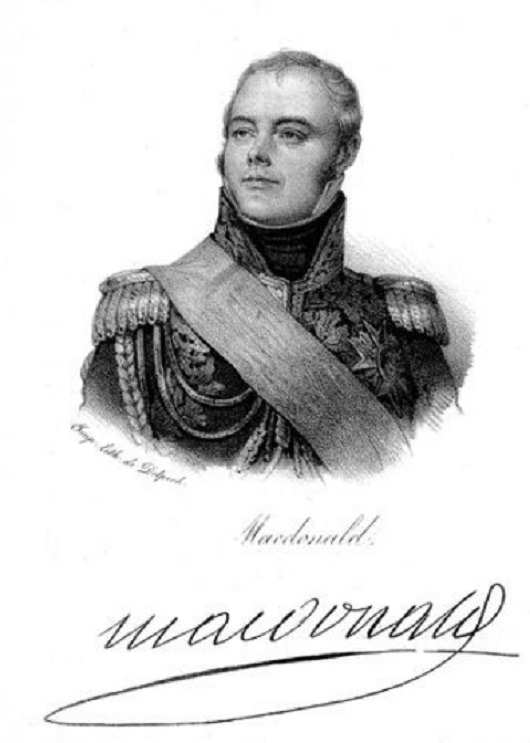

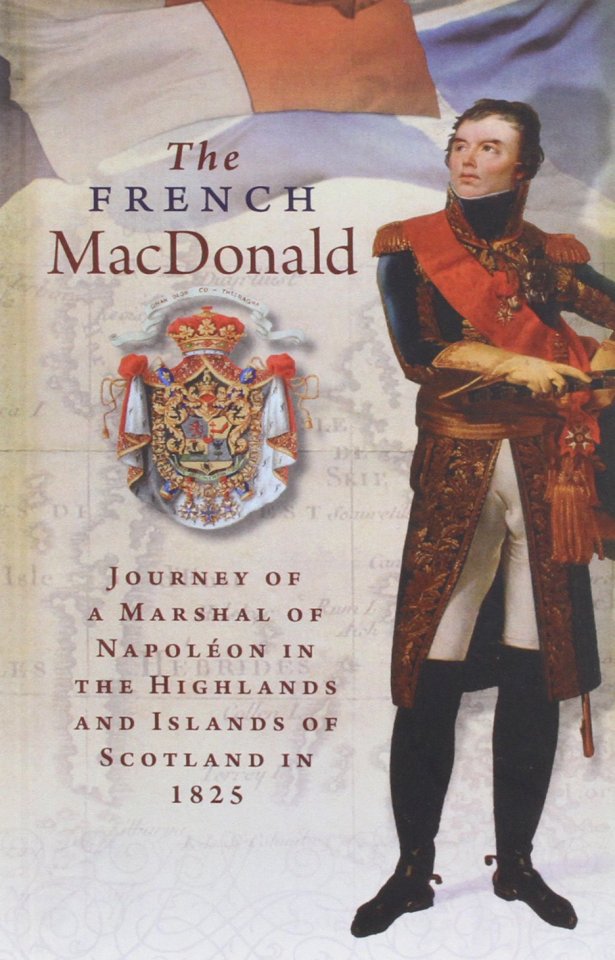

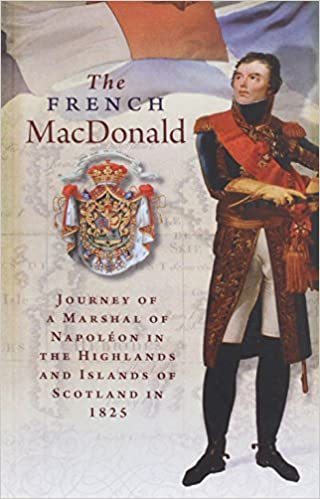

17th November 1765 saw the birth of Étienne Jacques Joseph Alexandre MacDonald at Sedan France.

The French MacDonald, as he is sometimes known, followed in a long tradition of Scots serving in the army of France, although the vast majority were Royalist it is inevitable I would stumble upon a Republican sooner or later.

Étienne was the son of Neil MacDonald, a Jacobite who played a key role in Charles Edward Stuart's escape following his defeat at Culloden in 1746 and also fled, living the rest of his life in exile in France.

A close comrade of Napoleon during his wars around Europe and against the British, this was at a time many Scots regiments were fighting in the European theatre of war, and of course, as mentioned in my post on Saturday, the Scots marched with the instrument of war, the bagpipes. It is with this in mind I found an interesting anecdote that Napoleon Bonaparte dared not let Étienne MacDonald within the sound of bagpipes, lest he defect and join the British. Étienne Jacques Joseph Alexandre MacDonald became a highly regarded military officer and following Napoleon's defeat he became a minister in the French government, a Peer of the Realm and was elevated to Arch-Chancellor of the order of the Legion d'Honneur. His statue stands on the side of the Louvre, his name is inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe and one of the boulevards of Paris was named after him.

Marshall MacDonald visited his fathers birthplace on South Uist in 1825, he returned to France with soil from the land at Howbeg. It was buried with him when he died.

When he died in 1840 at the age of 70 he was given a state funeral and buried in the Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris. Pere Lachaise is where the great and good of early nineteenth century Paris were buried. 14 of Napoleon's 26 Marshals are buried there.

Find out more about him here http://www.historyofwar.org/.../people_macdonald_marshal...

30 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Now there is nothing for it but abdication.

All that could be done had been attempted. It was a marvel that, after the disastrous campaign of Leipzig, the Emperor had been able to resist the invaders for three months. The time was come to make peace, and if Napoleon was an obstacle to it, he must be persuaded to withdraw. The enthusiasm of the soldiers was for the dispirited and disillusioned generals only a warning that there might be difficulties with the army, still so susceptible to the magical influence of its great leader. Ney, who had saved the remnant of the Grand Army amid the Russian snows, led his raw battalions of young troops on field after field in Germany, and taken such a prominent part in the obstinate struglle on the soil of France itself, was now foremost in declaring that all was over. “It is only an abdication that can get us out of this,“ he said.

It was agreed that a deputation of the marshals should wait upon Napoleon after the review. It needed some courage to beard the lion. The Emperor was in a desperate position, and might take a desperate course. He was quite capable of arresting the marshals and sending them before a court martial, for he felt he could count on the soldiers still, whatever the leaders might say. Ney, always ready to take risks, offered himself as spokesman of the deputation. Two of the elder marshals joined him, Lefebvre, Duke of Dantzig, and Moncey, a veteran of the armies of Spain, now 60 years of age, who had commanded the National Guard of Paris on the day of the Allied attack, and who was to show next year on the occasion of Ney’s trial that his moral courage was as great as the soldierly resolution he had so often displayed in the field.

Napoleon had gone back to the palace, and was with Berthier, Bassano, Caulaincourt, and Bertrand, in his study, when the three marshals asked for an immediate audience and entered the room almost before a reply could be given. There was an awkward pause. Then Ney asked the Emperor if there were any news from Paris. Napoleon, though he had just heard from Caulaincourt of a hostile vote of the Senate, answered that he had no news of any kind. Then Ney said that he himself had bad news from the capital. The Senate had declared for the abdication of the Emperor. Napoleon showed no surprise, but quietly pointed out that this was beyond the powers of the Senate, and a matter for the vote of the whole nation. “As for the Allies,“ he said, “I am going to crush them before Paris.” Ney protested that further military operations were now hopeless, and at this point Lefebvre supported him. “It is a pity,” said Ney, “that peace was not made sooner. Now there is nothing for it but abdication.” Napoleon still remained calm. He began to argue about the military possibilities of the situation. He counted up the forces at his command about Fontainebleau, and those he could summon from other parts of France. The Allies, he said, could not maintain themselves with a large army at Paris. He would cut them off from their communications, and the first success he won would be the signal for a widespread rising against the invaders. The marshals listened in stony silence. Berthier and the others said not a word in support of the Emperor’s plea to be allowed one more throw of the deadly dice of war. They were of Ney’s opinion.

While Napoleon was thus arguing to deaf ears, Macdonald and Oudinot entered and reported the arrival of their army corps. The Emperor hoped that they would support him, and spoke of the projected march on Paris. But they sided with Ney. “I declare to you, “ said Macdonald, “that we do not mean to expose Paris to the fate of Moscow. We have taken our decision, and are resolved to make an end of all this.” Once more Napoleon argued that the struggle could be resumed with good hope of victory, and finally declared that, notwithstanding the contrary opinion of the marshals, he would attack Paris. Ney interrupted him. “But the army will not march on Paris,” he said. For the first time Napoleon raised his voice, and looking the Marshal in the face said to him: “The army will obey me!” “Sire,” replied Ney sternly, “the army will obey its generals.”

It was a declaration of war. The two men stood face to face. The others looked on silently, expecting an outburst of anger from Napoleon. But after a pause he resumed his calmer tone, and asked the Marshals to withdraw and leave him alone with Caulaincourt.

A. Hilliard Atteridge - Marshal Ney, the Bravest of the Brave

#napoleonic#a.hilliard atteridge#marshal ney: the bravest of the brave#the first abdication of napoleon#napoléon bonaparte#michel ney#françois joseph lefebvre#bon adrien jeannot de moncey#louis alexandre berthier#armand de caulaincourt#henri gatien bertrand#bassano#étienne macdonald#nicolas oudinot#the marshals vs napoleon#we were weary#the army will obey its generals#we are resolved to make an end of all this

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

LOOK WHO ARRIVED TODAY

BABEYMUGS

@aminoscribbles look at our precious babeys))

#michel ney#marshal bae#ginger babey#Étienne jacques joseph alexandre macdonald#jacques macdonald#shortbread babey#MacMarshal#macposting#babeyposting#got the perfect mugs for mugshots#precious babeys

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy birthday, Marshal Macdonald!

Yes, I’m a day early. Tomorrow will be a difficult day, and I don’t trust this post not to disappear - again - if I put into “drafts”.

One preliminary note about Jacques-Étienne Macdonald (1765-1840): He might have been of Scottish origin, but he spelled his name as the Frenchman he was, with both d’s lower case. So it’s Macdonald, not MacDonald.

This is what Jean Tulard writes about him:

Ce fils d'un Ecossais jacobite réfugié en France entra en 1784 à la légion irlandaise. Il fit une brillante carrière militaire grâce à la Révolution: il est déjà général de division en 1794 puis gouverneur des Etats romains en 1798. Sa défaite devant Souvarov à la Trébie ne compromet pas on avenir jusqu'en Brumaire. Il n'a jamais servi sous Bonaparte qui s'en méfie et l'envoie comme ambassadeur au Danemark. De retour en France, Macdonald se fait le défenseur du général Moreau en 1804. La disgrâce est éclatante.

Pourtant Napoléon ne peut le tenir écarté trop longtemps : il manque de généraux d'expérience. Le 2 août 1809, il envoie Macdonald assister Eugène de Beauharnais à l'armée d'Italie. Il écrit à Eugène : " Cet officier a des talentset du nerf mais je ne me fie pas à ses opinions politiques, Cependant les choses sont bien changées. Je suppose qu'il vous servira de tous ses moyens et qu'il voudra gagner le grade où ses talents et ses anciens services l'appellent. "

A Wagram, Macdonald joue un rôle décisif en enfonçant le centre de l'ennemi. Il y gagne un bâton de maréchal le 12 juillet 1809, la plaque de Grand Aigle le 14 août et le titre de duc de Tarente. Napoléon l'embrassa sur le champ de bataille. Attendri, Macdonald s'écria qu'il lui " vouait désormais une fidélité sincère. "

Il fait de son mieux en Espagne comme commandant de l'armée de Catalogne, puis en Russie, avant d'être battu en 1813 à Katzbach.

Fidèle à sa promesse sur le champ de bataille de Wagram, il fut le dernier des maréchaux à se rallier au gouvernement provisoire et à Louis XVIII, mais il eut l'élégance de rester fidèle au roi pendant les Cent-Jours

Il avait épousé la veuve de Joubert et laissa d'intéressants mémoires sur la campagne de 1809.

This son of a Scottish Jacobite who had taken refuge in France enlisted in the Irish legion in 1784. He made a brilliant military career thanks to the Revolution: he was already a divisional general in 1794, then governor of the Roman States in 1798. His defeat by Suvarov at the Trebbia did not jeopardise his future until Brumaire. He never served under Bonaparte, who distrusted him and had him sent as ambassador to Denmark. Back in France, Macdonald championed General Moreau in 1804. The result was his utter disgrace.

Yet Napoleon could not keep him at bay for too long: he needed experienced generals. On 2 August 1809, he sent Macdonald to assist Eugène de Beauharnais with the army of Italy. He wrote to Eugène: "This officer has talent and energy, but I do not trust his political views. However, matters are quite different now. I imagine that he will serve you to the utmost of his abilities, and that he will seek to obtain the rank to which his talents and his former services entitle him."

At Wagram, Macdonald played a decisive role when he broke through the enemy's centre. He won his Marshal's baton on 12 July 1809, the plaque of Grand Eagle [of the Légion d'honneur] on 14 August of the same year, as well as the title of Duke of Taranto. Napoleon embraced him on the battlefield. Moved by this gesture, Macdonald exclaimed that he was henceforth "devoted to him in sincere loyalty."

He did his best in Spain as commander of the Army of Catalonia, then in Russia, but was defeated in 1813 at Katzbach.

True to his pledge on the battlefield of Wagram, he was the last of the Marshals to rally to the provisional government and to Louis XVIII, but he had the grace to remain loyal to the King during the Hundred Days.

He had married Joubert's widow. He left interesting memoirs about the 1809 campaign.

Jean Tulard, Dictionnaire amoureux de Napoléon. Plon, 2012, pp. 357-358

That is rather concise. As far as I know, no biography of Macdonald has been published.

A few notes here:

I think Tulard is wrong about Macdonald being sent to Eugène in August 1809. To my recollection, this happened before the battle of Wagram.

Macdonald was the only one of the Marshals to acquire his “marshmallow stick” on the battlefield.

As for Macdonald marrying Joubert’s widow, that is true enough; however, Macdonald married not once but three times, and was widowed all three times. All his wives died while still in their twenties. One of them, the last I believe, was the sister of Montholon, the St. Helena courtier and memoirist.

25 notes

·

View notes

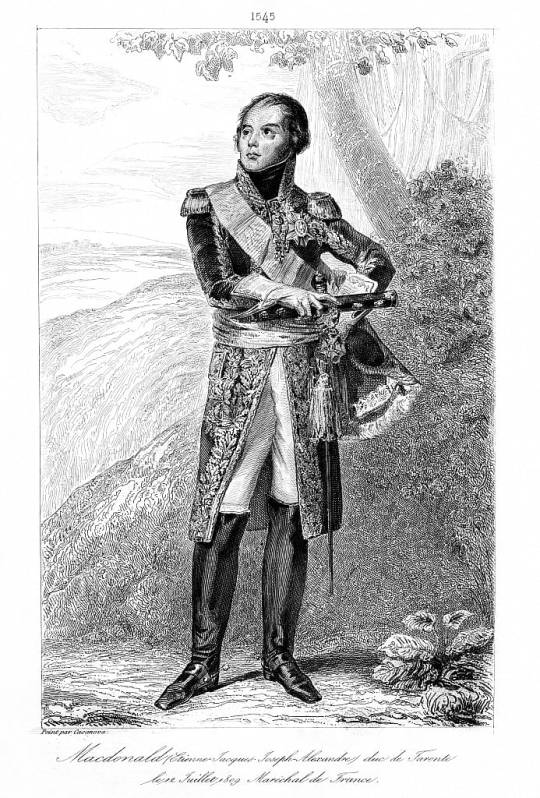

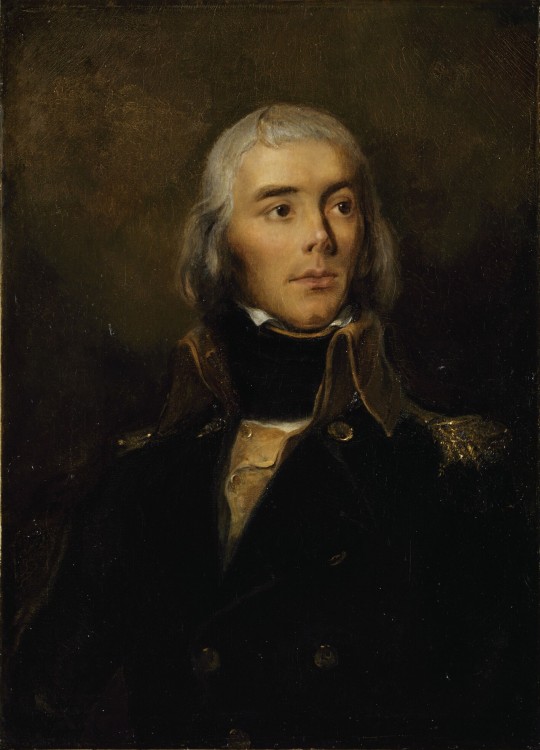

Photo

Étienne Jacques Joseph Alexandre MacDonald, capitaine aide de camp en 1792 par Louis Edouard Rioult

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here, a definitely historically accurate picture of Napoléon holding fries made by (marshal) MacDonald as my 69th post on this blog.

Thanks for sending me this picture, @diagnosed-anxiety-disorder! <3

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Watch the 2024 American Climate Leadership Awards for High School Students now: https://youtu.be/5C-bb9PoRLc

The recording is now available on ecoAmerica's YouTube channel for viewers to be inspired by student climate leaders! Join Aishah-Nyeta Brown & Jerome Foster II and be inspired by student climate leaders as we recognize the High School Student finalists. Watch now to find out which student received the $25,000 grand prize and top recognition!

#ACLA24#ACLA24HighSchoolStudents#youtube#youtube video#climate leaders#climate solutions#climate action#climate and environment#climate#climate change#climate and health#climate blog#climate justice#climate news#weather and climate#environmental news#environment#environmental awareness#environment and health#environmental#environmental issues#environmental education#environmental justice#environmental protection#environmental health#high school students#high school#youth#youth of america#school

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Left to himself, he was always a day late”

17 November 1765--Étienne Jacques Alexandre Macdonald, future Marshal of France, is born.

For generations his true character has been obscured by the sympathy English writers felt for him because of his ancestry.

Macdonald was a son of the Wild Geese, his father being a Scots Jacobite refugee who had followed Bonnie Prince Charlie in “the ‘45,” and later obtained a French commission. Macdonald seems to have received some training in a private military school; his first service was with a semi-mercenary legion in the Dutch Army. He later gained a French commission through service as a gentleman cadet. A lieutenant in 1792, he was a colonel a year later, general of brigade in 1794, general of division in 1796. Very brave, energetic, tall and strongly built, with a commanding voice and a natural air of authority, he could make himself obeyed, even by revolutionary levies. Also, he was an expert scrambler, able to dodge the officer-hunting Jacobin extremists who considered “Mac” a title of nobility and to put his own interests above loyalty to commanders who might be in political disfavor. In early 1799 he got command of the Army of Naples through murky intrigue, but it did him little good: Called north to meet an Austro-Russian army under the famous Suvorov, he was badly wounded in a minor skirmish and then defeated at the Trebbia River. Sore in mind and body, he supported Napoleon’s coup d’état.... In 1809, on Clarke’s suggestion, Napoleon ordered Macdonald to northern Italy to serve under Eugène, noting that he could be used as a “wing” (corps) commander if Eugène so desired.... He did serve usefully and capped this at Wagram by leading the assault that cracked the Austrian left center. In 1812 he commanded the X Corps (Poles, Prussians, and various Germans) on Napoleon’s extreme left flank during the invasion of Russia. Though faced by nothing more than small Russian forces and long distances, he moved timidly; worse, he gave no help to Oudinot and St. Cyr on his right flank. (Later he would have the gall to label St. Cyr a “bad bedfellow.”) Doubtless his Prussian officers noted his behavior; once they were enemies again in 1813-14, they exploited his hesitations and flinching. Under the Emperor’s direct command he could still hit hard; left to himself, he was always a day late--when he did not retreat unnecessarily. At Fontainebleau he was prominent in the marshals’ mutiny, though he did his best to secure the French throne for Napoleon’s son. Thereafter he followed Louis XVIII.

Napoleon considered Macdonald brave but unlucky--meaning, in Napoleon’s vocabulary, that he lacked the quickness of mind to meet unexpected developments. He could be audacious, but too often unthinkingly so: At the Trebbia and again at the Katzbach in 1813 he deliberately crossed a difficult stream on a broad front against a superior enemy, at the Katzbach despite Napoleon’s express orders.

Macdonald suffered from a tendency to free and sarcastic speech, never missing a chance for a jest--preferably barbed. On reexamination, his Souvenirs are unreliable history; he blandly claims credit for actions where he was not present and blames his failures on his subordinates.

By making him a marshal, Napoleon hung a millstone around his own neck. With Oudinot and Marmont, that made three millstones.

--John R. Elting, Swords Around a Throne: Napoleon’s Grande Armée

#Étienne Jacques Macdonald#Nicolas Charles Oudinot#Napoleon's marshals#today in history#Napoleonic wars#Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les gagnants de la 10e édition du concours sont dévoilés !

Trente élèves ont remporté le concours Mordus des mots 2018-2019. Leurs nouvelles fantastiques seront publiées en mai prochain dans un recueil tiré à plus de mille exemplaires. Toutes nos félicitations aux gagnants et merci à toutes les écoles qui ont pris part au concours cette année !

Est ontarien :

Lauréanne Bousquet, École secondaire catholique Béatrice-Desloges

Alima Traoré, École secondaire publique Gisèle-Lalonde

Marianne Lessard, École secondaire publique Gisèle-Lalonde

Nicolas St-Pierre, École secondaire catholique Plantagenet

Madeleine de Salaberry, École secondaire publique De La Salle

Sophie Shields, École secondaire De La Salle

Marie-Jade Larocque, École secondaire catholique L’Escale

Clarissa Martin, École secondaire catholique régionale de Hawkesbury

Emanuelle Savard, École secondaire publique Le Sommet

Yanik Ranger, École secondaire catholique de Casselman

Aline Ahouzi, Collège catholique Mer Bleue

Nord ontarien :

Robert Connor Catherwood, École secondaire L’Alliance

Emily Brock, École secondaire du Sacré-Cœur

Artin Lafrance, École secondaire Macdonald-Cartier

Stéfani Fortin, École secondaire catholique Franco-Cité

Alex Dillon, École secondaire catholique de Hearst

Mathieu Jacques, École secondaire catholique de Hearst

Rafaëlle Boutin-Chabot, École secondaire catholique de Hearst

Ryan Lafleur, École secondaire catholique de Hearst

Sud ontarien :

Abigail-Rose Barbeiro, École secondaire Gabriel-Dumont

Maxime Savehilaghi, École secondaire Gabriel-Dumont

Louardiane Soundous, École secondaire Toronto-Ouest

Hanad Elmi, École secondaire Toronto-Ouest

Brooklyn Kaiser, École secondaire catholique Notre-Dame

Chloé Herbulot, École secondaire Étienne-Brûlé

Amelia Soon, École secondaire Étienne-Brûlé

Steve Fotso, École secondaire de Lamothe-Cadillac

Anaïs Delhomelle, Collège français

Alexander Cappadocia, École secondaire catholique Nouvelle-Alliance

Maggi Dewolf-Russ, École secondaire catholique L’Essor

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

We have finally reached the end of the first round, reducing our 128 person list to 64.

Here is the complete list of who is competing in round 2:

France:

Jean Lannes

Thérésa Tallien

Antoine Charles Louis de Lasalle

Germaine de Staël

François Joseph Lefebvre

Géraud Duroc

Étienne Jacques-Joseph-Alexandre Macdonald

Auguste François-Marie de Colbert-Chabanais

Thomas-Alexandre Dumas

Juliette Récamier

Louis-Francois Lejeune

Louis-Alexandre Berthier

Michel Ney

Joseph Fouché

Nicolas Charles Oudinot

Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont

Jean-Andoche Junot

Josephine de Beauharnais

Andrea Masséna

Joachim Murat

Pauline Bonaparte, Duchess of Guastalla

England:

Richard Sharpe

Tom Pullings

Benjamin Bathurst

Horatio Nelson

Barbara Childe

Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry (Lord Castlereagh)

Captain Jack Aubrey

Horatio Hornblower

Admiral Edward Pellew

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Emma, Lady Hamilton

Scotland:

Thomas Cochrane

Ireland:

Doctor Stephen Maturin

Austria:

Friedrich Bianchi, Duke of Casalanza

Klemens von Metternich

Marie Louise

Wilhelmine von Biron

Archduke Karl

Poland:

Wincenty Krasiński

Józef Zajączek

Zofia Czartoryska-Zamoyska

Józef Antoni Poniatowski

Maria Walewska

Russia:

Prince Andrei Bolkonsky

Levin August von Bennigsen

Pavel Stroganov

Barclay de Tolly

Ekaterina Pavlovna Bagration

Alexander Andreevich Durov

Karl Wilhelm von Toll

Mikhail Miloradovich

Alexander I Pavlovich

Empress Elizabeth Alexeievna

Pyotr Bagration

Prussia:

Louise von Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Frederick William III

Friederike of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Alexander von Humboldt

Dorothea von Biron

The Netherlands:

Ida St Elme

Spain:

Juan Martín Díez

José de Palafox

Lombardy:

Alessandro Manzoni

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

17th November 1765 saw the birth of Étienne Jacques Joseph Alexandre MacDonald at Sedan France.

Scots have had a long history with France, and it did not end with the French Revolution, although no doubt some may very well have become victims of the era and lost their lives and lands, others like Franco-Scot, Étienne MacDonald, would go on to show that their devotion was to France rather than to the ruler.

I’ve posted a few times about MacDonald, but not fully delved into his story, so this is lifted entirely from an article I read. It is a rather long piece, but I found it s very interesting easy read, and shows a man of great dignity. His life covers the French Revolution right through to Napoleon's campaigns through Europe, including his invasion of Russia and his initial abdication in 1814, and beyond.

In 1784 the British Parliament passed the Act of Amnesty which pardoned all Jacobites, but despite this, Étienne’s father Neil MacDonald, who helped Charles Edward Stuart escape to France after the ‘45, never returned to Scotland on account of his poor health and he died in poverty 4 years later.

By this time his son Jacques MacDonald, as he was known, had already begun a promising military career in the French army, and that he would later be central to the cataclysmic events of the French Revolution, Napoleonic Wars and Restoration of the Bourbon Monarchy in France..

MacDonald began his French military career in 1786 by joining the ‘Dillon Regiment’, which was primarily composed of Scottish and Irish Jacobite exiles. The regiment remained loyal to Louis XVI at the outbreak of the revolution in 1789, which led not only to its disbandment in 1791, but the execution of its Colonel, Arthur Dillon, by guillotine in 1794. MacDonald on the other hand was personally loyal to the revolution, marrying a Mademoiselle Jacob, whose father was an enthusiastic supporter of the changes that were taking place in French society.

At the outbreak of war in 1792 MacDonald continued to serve in the new army and was offered a prestigious position as aide-de-camp to General Dumouriez. He distinguished himself at the Battle of Jemappes,and he was also present alongside Dumouriez at the Battle of Valmy. The victory of the French volunteer army at Valmy was a significant turning point in the Revolutionary Wars and it compelled France to formally abolish the monarchy shortly afterwards. By 1793 MacDonald had risen to the rank of Colonel and then refused to desert the Revolutionary Army when Dumouriez defected to the enemy. As a reward for this loyalty he was given the command of a Brigade.

By 1797 he had become a General of a Division and joined the French Army in Italy. He occupied Rome, became the governor of the city, defeated the Austrian Army of General Mack before reorganising the Kingdom of Naples into the Parthenopaean Republic. In 1801 he became the French ambassador to Denmark but did not enjoy the politics of diplomacy and he later asked to be recalled.

After returning to France, it was clear the French Republic was in crisis. Its armies were being outfought by a coalition of empires determined to destroy revolutionary ideas. Internally, France had become politically unstable and a coup d’etat was planned to overthrow the government. It was decided that a general should be part of the coup to ensure the support of the army. The conspirators first choice, General Joubert, was killed in Italy before he could be asked. General Moreau was then asked, but he refused to be a figurehead of the coup. The decision then came to MacDonald himself, and like Moreau before him, he also refused. The next choice for the conspirators was Napoleon Bonaparte, who accepted the offer and took power backed by the army and MacDonald.

Following these events, MacDonald took command of the French Army of Switzerland, an important position that linked the French armies fighting in Germany with those in Northern Italy. He fell out of favour with Napoleon after associating with his rival, General Moreau. This led to Napoleon overlooking MacDonald in his first allocation of Marshals of France around 1805.

The Napoleonic Wars continued from 1805 but MacDonald still remained without a position in the French Army. It wasn’t until 1809 that Napoleon finally allocated command of a Corps to MacDonald, also giving him the responsibility of being a military adviser to Napoleon’s adopted son, Prince Eugene de Beauharnais, the Viceroy of Italy.

The highlight of MacDonald’s career soon followed at the Battle of Wagram in 1809. MacDonald was in command of the reserve corps, and at the height of the battle he was ordered to attack the Austrian centre to relieve pressure on the other parts of the French line. Forming his 8,000 soldiers into an unusual column formation that resembled a large hollow rectangle, MacDonald advanced and successfully held off three Austrian cavalry charges. Under concentrated Austrian cannon and musket fire his Corps suffered 50% casualties and could not advance any further. MacDonald recognised that the Austrians were now disorganised because of his attack, and he ordered the French Guard Cavalry to attack and seize the opportunity to destroy the Austrian centre. General Walther, commander of the Guard Cavalry, refused to take an order from anyone other than Napoleon himself and his cavalry remained stationary. This crucial delay resulted in a lost opportunity to capitalise on the gains that MacDonald had made. Both MacDonald and Napoleon were later furious with General Walther for this decision, Napoleon even being moved to say that it was the first time his cavalry had ever let him down.

Despite the failure of the Guard Cavalry, MacDonald’s attack had sufficiently occupied the attention of the Austrians to allow the French to successfully conduct a general attack on other parts of the line. The French had won the battle and Napoleon rode directly to MacDonald and upon embracing him said,

“General MacDonald, Let us be friends henceforth. You have behaved valiantly and have rendered me the greatest services throughout the entire campaign. On the battlefield of your glory, where I owe you so large a part of yesterday’s success, I make you a Marshal of France. You have long deserved it.”

MacDonald was the first French Marshal to be created on the field of battle and he graciously asked Napoleon to let the rewards be distributed equally among the men of his corps. Napoleon said that he could not refuse him and in further recognition of his services he soon afterwards awarded MacDonald the Grand Eagle of the Legion of Honor, the title of Duke of Taranto and 60,000 francs.

Following the Battle of Wagram, MacDonald was made the Governor of Gratz, a role which he undertook with such distinction that the city wanted to pay him 200,000 Francs when he left, an offer which he refused. MacDonald was then made the Commander of the French army in Catalonia, and also the Governor-General of the principality. MacDonald had serious objections to the manner in which the French were fighting the war in Spain, which had degenerated into a brutal war between French regulars and Spanish guerrilla fighters. Putting aside his objections, he took up the role and met with mixed success. He was defeated at the Battle of Pla in 1811, but later took Figueras after a 4 month siege. Both of these battles were typical of the Spanish War in which large numbers of French troops and resources were tied down by relatively small numbers of elusive Spanish troops. Following the siege of Figueras, MacDonald experienced a sever case of gout, followed by fever. He asked to be transferred and returned to Paris, unable to walk without the assistance of crutches.

MacDonald recovered in time to be present at the French invasion of Russia in 1812, in which he commanded the X Corps and the left wing of the Grand Army. This Corps was a multinational formation, comprising Poles, Bavarians, Westphalians and Prussians. Initially the invasion met with little resistance and MacDonald was able to defend the flank of Napoleon’s invasion by routing a Russian Army near Riga in present day Latvia. Despite his Prussian infantry playing a major part in the victory, MacDonald started to become suspicious of them after they less than enthusiastically undertook his order to pursue and capture the defeated Russians.

After a series of battles Napoleon went on to capture Moscow, which had been completely abandoned by the Russians. After Moscow had been under occupation for three days, the city was set alight by a handful of Russians who had stayed behind to prepare the trap. The resulting fire destroyed 80% of the mostly wooden city and came as a terrible shock to the morale of the French army. Tsar Alexander continued to ignore all calls for surrender from Napoleon and with the French army now camped in a ruined city Napoleon had no choice but to retreat, which the Grand Army began in October 1812.

In November 1812 Napoleon learned that there had been a coup against his rule in Paris. Leaving Marshal Murat in command he left the army had hurried back to Paris to deal with the political problems that had arisen. Marshal Murat also later abandoned the army to save his Kingdom of Naples, leaving Napoleon’s adopted son the Viceroy of Italy, Prince Eugène de Beauharnais in command. MacDonald had previously been a close colleague and military mentor to de Beauharnais and they had worked closely together to secure the French victory at Wagram two years previously.

The French Army had initially invaded Russia with an Army of 450,000 men, but now the remaining 150,000 had the unenviable task of retreating from Moscow through a vicious Russian winter and temperatures of -40c. As the pursuing Russians picked away at the remnants of what was once the largest army in European history, MacDonald was trying to deal with problems within his own Corps. During the retreat he was shocked to discover that General Yorck and the Prussians under his command had defected from MacDonald’s Corps en masse, secretly leaving the army during the night. MacDonald wrote contemptuously of these Prussian’s in his memoirs but he spoke highly of the Polish, Bavarian and Westphalian soldiers of his Corps, who he described as serving faithfully, courageously and with distinction.

During the final stages of the retreat, Marshal Murat requested the advice of MacDonald on how the French Army should proceed. MacDonald recommended abandoning all territory east of the Oder River, holding the line along the river and waiting for the fresh troops being assembled in France. His advice was ignored and the retreat would continue. The total losses during the whole campaign amounted to 380,000 men, with just 35,000 Frenchmen making it home from the initial force.

MacDonald eventually did make it back to France, despite having his travelling expenses of 12,000 francs stolen from him on his way through Prussia. He received a frosty reception from Napoleon when he eventually returned to Paris. The Emperor had been led to believe that the Prussians had deserted the army because MacDonald had treated them badly. In his memoirs MacDonald also suggests that this less than cordial meeting was because Napoleon felt resentment towards his plan of abandoning all territory East of the Oder River. MacDonald left the meeting bemused and with understandable disdain that his services and devotion were met with such a lack of appreciation. However some days later, news had reached Napoleon that the Prussian Government had fully accepted the actions of their soldiers, implying that the desertions had nothing to do with the way MacDonald treated them and everything to do with an imminent Prussian declaration of war against France. He was subsequently summoned by Napoleon, who admitted that he had been misled regarding MacDonald’s actions in Russia, and that he did in fact act wisely in his dealings with the Prussian soldiers of his command.

By 1813 MacDonald was back in the field, joining the 200,000 largely inexperienced soldiers that were sent to link up with the remnants of the French Army in central Europe. A new coalition of powers, including Prussia, had rallied together to defeat Napoleon following his disastrous invasion attempt of Russia.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Leipzig, MacDonald and Prince Poniatowski of Poland were given command of a desperate rear guard action. Hopelessly outnumbered, MacDonald and Poniatowski made a fighting withdrawal through Leipzig towards a bridge across the river Elster. Learning that the bridge had in fact been destroyed by the French in the confusion of the retreat, Poniatowski attempted to swim across the river on horse back. He made it across, but the bank was steep and his horse fell with exhaustion, drowning Poniatowski in the river. As the front disintegrated MacDonald found himself being followed by a crowd of his men desperate to escape the approaching enemy. Seized by his aide-de-camp, MacDonald found a makeshift bridge of wooden logs that had been hastily constructed by a resourceful French engineer. MacDonald dismounted and began walking across the flimsy construction, but as his men began to follow him the bridge began to shake, causing MacDonald to fall into the river. Luckily he fell close enough to the shore that his feet could reach the bottom of the river but he struggled to get out because of the loose soil and steep embankment. Enemy skirmishers fired on him at point blank range before they were scared off by French musket fire on the opposing river bank.

MacDonald barely escaped with his life and upon reaching the top of the riverbank he turned to see whole companies of his men falling into the river, crying out “Marshal! Save your men, save your children!” as they were swept away to their deaths. Overcome with rage and frustration at being unable to save his men, he sat on the riverbank and wept. MacDonald recalls in his memoirs that this scene traumatised him for years after the event and that he could often hear the voices of the screaming men ringing in his ear.

MacDonald was furious with Napoleon for allowing the whole disaster to happen and he initially refused to even meet with the Emperor. Rumors subsequently spread through the army that MacDonald had been killed while crossing the river, but he survived and eventually made his way to Cologne to rebuild his shattered Corps. He remained one of the central commanders of the now hopeless French efforts to keep the allied powers from entering France. Ultimately Paris was captured by the allies in 1814. As Napoleon raced to Fontainebleau it was clear the soldiers were no longer willing to follow Napoleon on what was obviously a lost cause. MacDonald was encouraged to approach Napoleon on behalf of the army, making him aware that the soldiers wanted peace. MacDonald made these points to Napoleon at Fontainebleau, expecting the Emperor to fly into a violent rage, but was surprised when Napoleon reacted quite calmly to the fall of Paris and the reality that the starving and worn out remnants of the army could no longer go on fighting. Napoleon hailed MacDonald as a “good and honorable man” for his frankness and openness. He then turned to all those in the room and announced that he would abdicate the throne in favour of his son. Napoleon sat and wrote out his abdication, rewriting the draft two or three times. Then as Napoleon dismissed them for the evening, he threw himself on the sofa, slapped his leg with his hand and proclaimed, “Nonsense, gentlemen! Let us leave all that alone and march tomorrow, we shall beat them!” No doubt bemused by this departure from reality, MacDonald reiterated everything he had already said about the perilous state of the army. The Marshals, led by Marshal Ney then decided to mutiny against Napoleon to prevent further pointless bloodshed. Napoleon eventually yielded to the inevitable and MacDonald, along with Caulaincourt and Ney, left to personally negotiate the terms of surrender with Tsar Alexander of Russia on behalf of Napoleon.

MacDonald was to write that Tsar Alexander was gracious in victory and spoke respectfully of the French. MacDonald notes in his memoirs that aside from Marshal Ney, who was unstable and aggressive, Tsar Alexander’s conciliatory tone was reciprocated by the French Marshals. The Prussians were far less accommodating and were quick to remind the French that they were the scourge of Europe, immediately demanding compensation and providing none of the compliments that the Tsar had generously offered the French army. The other main member of the allied coalition was Austria, who was willing to allow Napoleon’s wife and son to keep their titles, but on the condition that they were prohibited from ever attaining power in France. Britain refused to negotiate at all, claiming that they did not recognise Napoleon as a legitimate authority, which was probably just as well for Napoleon who half heartedly said that you could “never trust a MacDonald within sound of bagpipes.”

Following the exchange, the allied powers were keen to ensure that the Marshals submitted to the new order. This would guarantee that the French Army would also obediently submit to the provisional government. Marshal Ney immediately submitted, but MacDonald and Caulaincourt remained loyal to Napoleon until the formal ratification of the treaty, after which time MacDonald wrote a simple statement to the provisional government saying that “being released from my allegiance by the abdication of the Emperor Napoleon, I declare that I conform to the Acts of the Senate and the Provisional Government.” This act of dignified defiance infuriated the ever scheming French statesmen de Talleyrand, whose face was said to turn pale before almost bursting with rage when MacDonald politely refused to submit until the formal ratification of the treaty.

MacDonald returned to Fontainbleu to call upon Napoleon. On the morning of the 13th of March 1814, MacDonald entered to find a despondent Napoleon wearing his dressing gown and slippers, with his head buried in his hands and his elbows on his knees. He did not stir when MacDonald entered the room, but on prompting from Caulaincourt he appeared to wake from a dream and MacDonald found him to have a sickly yellow-green complexion. Napoleon apologised and said that he had been sick all night, later evidence suggests that it was likely Napoleon had taken an overdose of opium in an attempt to try and sleep after the emotionally exhaustive events of recent months.

Again, Napoleon sat in the room, remained silent for a period of time before turning to MacDonald and saying,

“Duke of Tarentum, I cannot tell you how touched and grateful I am for your conduct and devotion. I did not know you well; I was prejudiced against you. I have done so much for, and loaded with favours, so many others, who have abandoned and neglected me; and you, who owed me nothing, have remained faithful to me I appreciate your loyalty all too late, and I sincerely regret that I am no longer in a position to express my gratitude to you except by words.”

Napoleon noted that MacDonald had always had a generous manner, never accepting large amounts of money while being an impartial ruler who brought justice wherever he commanded. Napoleon then implored MacDonald to accept the sword of the former leader of the Mamelukes, Murad Bey, which had been captured in Egypt in 1798 and worn by Napoleon at the Battle of Mount Tabor in 1799. MacDonald accepted the gift as a sign of Napoleon’s friendship and the two commanders emotionally embraced each other. It was the last time that MacDonald and Napoleon would ever meet.

I think I’ve taken this as far as I want to for this lengthy post, but there is much more to read in part two just click here!

When he died in 1840 at the age of 70 he was given a state funeral and buried in the Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris. Pere Lachaise is where the great and good of early nineteenth century Paris were buried. 14 of Napoleon’s 26 Marshals are buried there.

Somhairle MacGill-Eain/ Sorley MacLean, wrote a poem about Marshal Étienne Jacques MacDonald of France, I shall post that later.

There are more pics in the article I took this from here https://sonofskye.wordpress.com/2014/05/10/marshal-etienne-jacques-macdonald-of-france-1765-1814/

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Watch the American Climate Leadership Awards 2024 now: https://youtu.be/bWiW4Rp8vF0?feature=shared

The American Climate Leadership Awards 2024 broadcast recording is now available on ecoAmerica's YouTube channel for viewers to be inspired by active climate leaders. Watch to find out which finalist received the $50,000 grand prize! Hosted by Vanessa Hauc and featuring Bill McKibben and Katharine Hayhoe!

#ACLA24#ACLA24Leaders#youtube#youtube video#climate leaders#climate solutions#climate action#climate and environment#climate#climate change#climate and health#climate blog#climate justice#climate news#weather and climate#environmental news#environment#environmental awareness#environment and health#environmental#environmental issues#environmental justice#environment protection#environmental health#Youtube

11K notes

·

View notes