#least said soonest mended

Text

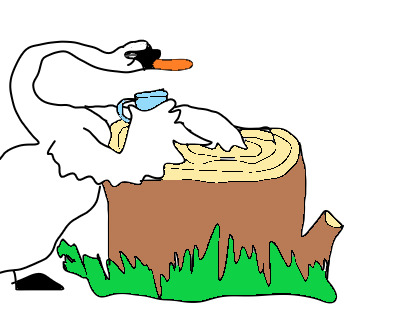

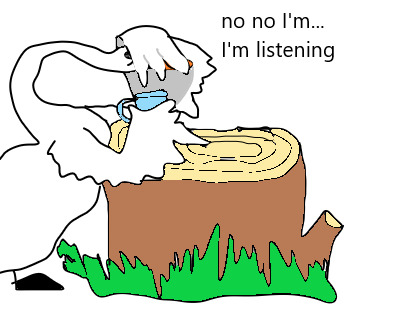

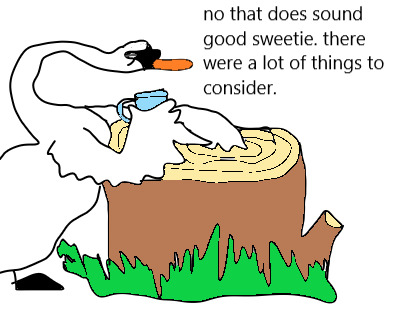

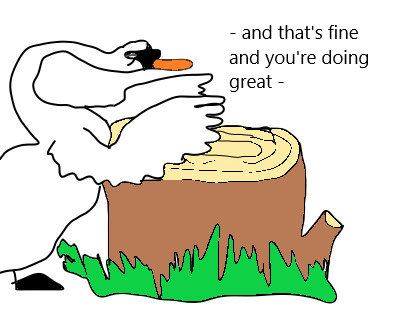

#swan comics#a swan in a santa hat#🦢#I thought about posting this in response to someone#but that would be a bit too much I think#no harm done#least said soonest mended#but this is a conversation I have in my home as well so#perhaps we need a visual shorthand#where the FUCK is my CUP#this is the response to a) kids not putting their socks on but coming downstairs dressed as crocodiles#b) spouse mishearing something but gallantly giving an opinion on it that was so in depth I didn’t have the heart to interrupt#and c) someone explaining to me about the discworld reading order#on a post about the saddening lack of risk-taking and support for creators in the content-gatekeeping industry#none of those are crimes not even the socks#I can strongly understand the Considerations that beset and bedazzle you when you go to put socks on and how the best response is to put on#a fuzzy crocodile onesie#but it’s not what I asked.#like this is a good response to a different thing#please recall the input here - the assignment if you will - was about socks. I love what you’ve done here though#good contribution. you know what we’re keeping it. love it.#just don’t present it as if the original incident report can be marked closed now okay?#do not close the support ticket#the support ticket remains unanswered.#no I completely agree. the outfit DOES need green face paint too. a topic we can add to the queue when oddly enough you have socks on

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghost being raised on ‘least said, soonest mended’ (translation: stop crying before I give you something to really cry about) and never breathes a word about how he’s feeling to anyone.

And Soap being told his whole childhood to ‘let it all out, my lad. It’s ok, feelings are tricky things’ and trying his hardest to get that through to Simon.

It takes Mama MacTavish, and the infinite pool of patience cultivated from raising her wildfire of a son, to break down those walls. Cuppa tea and a kind word every Sunday and suddenly Simon is telling Johnny when something has upset him and what he would like done differently.

“I don’t like the new washing powder, Johnny. It smells… funny.” Simon mumbles, eyes to the floor and shifting uncomfortably from foot to foot.

It’s the smallest thing. Nothing in the grand scheme of getting Ghost to open up and say how he feels, but Soap is grinning like a loon and trying not to punch the air in victory. This is the first time he’s given an opinion on anything other than tactics, bad jokes, or weapons and equipment. It’s a great first step.

“Alright, Si. I’ll get the old stuff again. Thank you for telling me.” Thanks, Ma.

416 notes

·

View notes

Text

Denazification, truth and reconciliation, and the story of Germany's story

Germany is the “world champion in remembrance,” celebrated for its post-Holocaust policies of ensuring that every German never forgot what had been done in their names, and in holding themselves and future generations accountable for the Nazis’ crimes.

All my life, the Germans have been a counterexample to other nations, where the order of the day was to officially forget the sins that stained the land. “Least said, soonest mended,” was the Canadian and American approach to the genocide of First Nations people and the theft of their land. It was, famously, how America, especially the American south, dealt with the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow.

Silence begets forgetting, which begets revisionism. The founding crimes of our nations receded into the mists of time and acquired a gauzy, romantic veneer. Plantations — slave labor camps where work was obtained through torture, maiming and murder — were recast as the tragiromantic settings of Gone With the Wind. The deliberate extinction of indigenous peoples was revised as the “taming of the New World.” The American Civil War was retold as “The Lost Cause,” fought over states’ rights, not over the right of the ultra-wealthy to terrorize kidnapped Africans and their descendants into working to death.

This wasn’t how they did it in Germany. Nazi symbols and historical revisionism were banned (even the Berlin production of “The Producers” had to be performed without swastikas). The criminals were tried and executed. Every student learned what had been done. Cash reparations were paid — to Jews, and to the people whom the Nazis had conquered and brutalized. Having given in to ghastly barbarism on an terrifyingly industrial scale, the Germans had remade themselves with characteristic efficiency, rooting out the fascist rot and ensuring that it never took hold again.

But Germany’s storied reformation was always oversold. As neo-Nazi movements sprang up and organized political parties — like the far-right Alternative für Deutschland — fielded fascist candidates, they also took to the streets in violent mobs. Worse, top German security officials turned out to be allied with AfD:

https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2018/08/04/germ-a04.html

Neofascists in Germany had fat bankrolls, thanks to generous, secret donations from some of the country’s wealthiest billionaires:

https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/billionaire-backing-may-have-helped-launch-afd-a-1241029.html

And they broadened their reach by marrying their existing conspiratorial beliefs with Qanon, which made their numbers surge:

https://www.thedailybeast.com/how-fringe-groups-are-using-qanon-to-amplify-their-wild-messages

Today, the far right is surging around Europe, with the rot spreading from Hungary and Poland to Italy and France. In an interview with Jacobin’s David Broder, Tommaso Speccher a researcher based in Berlin, explores the failure of Germany’s storied memory:

https://jacobin.com/2023/07/germany-nazism-holocaust-federal-republic-memory-culture/

Speccher is at pains to remind us that Germany’s truth and reconciliation proceeded in fits and starts, and involved compromises that were seldom discussed, even though they left some of the Reich’s most vicious criminals untouched by any accountability for their crimes, and denied some victims any justice — or even an apology.

You may know that many queer people who were sent to Nazi concentration camps were immediately re-imprisoned after the camps were liberated. Both Nazi Germany and post-Nazi Germany made homosexuality a crime:

https://time.com/5953047/lgbtq-holocaust-stories/

But while there’s been some recent historical grappling with this jaw-dropping injustice, there’s been far less attention given to the plight of the communists, labor organizers, social democrats and other leftists whom the Nazis imprisoned and murdered. These political prisoners (and their survivors) struggled mightily to get the reparations they were due.

Not only was the process punitively complex, but it was administered by bureaucrats who had served in the Reich — the people who had sent them to the camps were in charge of deciding whether they were due compensation.

This is part of a wider pattern. The business-leaders who abetted the Reich through their firms — Siemens, BMW, Hugo Boss, IG Farben, Volkswagon — were largely spared any punishment for their role in the the Holocaust. Many got to keep the riches they acquired through their part on an act of genocide.

Meanwhile, historians grappling with the war through the “Historikerstreit” drew invidious comparisons between communism and fascism, equating the two ideologies and tacitly excusing the torture and killing of political prisoners (this tale is still told today — in America! My kid’s AP history course made this exact point last year).

The refusal to consider that extreme wealth, inequality, and the lust for profits — not blood — provided the Nazis with the budget, materiel and backing they needed to seize control in Germany is of a piece with the decision not to hold Germany’s Nazi-enabling plutocrats to account.

The impunity for business leaders who collaborated with the Nazis on exploiting slave labor is hard to believe. Take IG Farben, a company still doing a merry business today. Farben ran a rubber factory on Auschwitz slave labor, but its executives were frustrated by the delays occasioned by the daily 4.5m forced march from the death-camp to its factory:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/06/02/plunderers/#farben

So Farben built Monowitz, its own, private-sector concentration camp. IG Farben purchased 25,000 slaves from the Reich, among them as many children as possible (the Reich charged less for child slaves).

Even by the standards of Nazi death camps, Monowitz was a charnel house. Monowitz’s inmates were worked to death in just three months. The conditions were so brutal that the SS guards sent official complaints to Berlin. Among their complaints: Farben refused to fund extra hospital beds for the slaves who were beaten so badly they required immediate medical attention.

Farben broke the historical orthodoxy about slavery: until Monowitz, historians widely believed that enslavers would — at the very least — seek to maintain the health of their slaves, simply as a matter of economic efficiency. But the Reich’s rock-bottom rates for fresh slaves liberated Farben from the need to preserve their slaves’ ability to work. Instead, the slaves of Monowitz became disposable, and the bloodless logic of profit maximization dictated that more work could be attained at lower prices by working them to death over twelve short weeks.

Few of us know about Monowitz today, but in the last years of the war, it shocked the world. Joseph Borkin — a US antitrust lawyer who was sent to Germany after the war as part of the legal team overseeing the denazification program — wrote a seminal history of IG Farben, “The Crime and Punishment of I.G. Farben”:

https://www.scribd.com/document/517797736/The-Crime-and-Punishment-of-I-G-Farben

Borkin’s book was a bestseller, which enraged America’s business lobby. The book made the connection between Farben’s commercial strategies and the rise of the Reich (Farben helped manipulate global commodity prices in the runup to the war, which let the Reich fund its war preparations). He argued that big business constituted a danger to democracy and human rights, because its leaders would always sideline both in service to profits.

US companies like Standard Oil and Dow Chemicals poured resources into discrediting the book and smearing Borkin, forcing him into retirement and obscurity in 1945, the same year his publisher withdrew his book from stores.

When we speak of Germany’s denazification effort, it’s as a German program, but of course that’s not right. Denazification was initiated, designed and overseen by the war’s winners — in West Germany, that was the USA.

Those US prosecutors and bureaucrats wanted justice, but not too much of it. For them, denazification had to be balanced against anticommunism, and the imperatives of American business. Nazi war criminals must go on trial — but not if they were rocket scientists, especially not if the USSR might make use of them:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wernher_von_Braun

Recall that in the USA, the bizarre epithet “premature antifascist” was used to condemn Americans who opposed Nazism (and fascism elsewhere in Europe) too soon, because these antifascists opposed the authoritarian politics of big business in America, too:

https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/premature-antifascist-and-proudly-so/

When 24 Farben executives were tried at Nuremberg for the slaughter at Monowitz, then argued that they had no choice but to pursue slave labor — it was their duty to their shareholders. The judges agreed: 19 of those executives walked.

Anticommunism hamstrung denazification. There was no question that German elites and its largest businesses were complicit in Nazi crimes — not mere suppliers, but active collaborators. Antifacism wasn’t formally integrated into the denazification framework until the 1980s with “constitutional patriotism,” which took until the 1990s to take firm root.

The requirement for a denazification program that didn’t condemn capitalism meant that there would always be holes in Germany’s truth and reconciliation process. The newly formed Federal Republic set aside Article 10 of the Nuremberg Charter, which would hold all members of the Nazi Party and SS responsible for their crimes. But Article 10 didn’t survive contact with the Federal Republic: immediately upon taking office, Konrad Adenauer suspended Article 10, sparing 10 million war criminals.

While those spared included many rank-and-file order-followers, it also included many of the Reich’s most notorious criminals. The Nazi judge who sent Erika von Brockdorff to her death for her leftist politics was given a judge’s pension after the war, and lived out his days in a luxurious mansion.

Not every Nazi was pensioned off — many continued to serve in the post-war West German government. Even as Willy Brandt was demonstrating historic remorse for Germany’s crimes, his foreign ministry was riddled with ex-Nazi bureaucrats who’d served in Hitler’s foreign ministry. We still remember Brandt’s brilliant 1973 UN speech on the Holocaust:

https://www.willy-brandt-biography.com/historical-sources/videos/speech-uno-new-york-1973/

But recollections of Brandt’s speech are seldom accompanied by historian Götz Aly’s observation that Brandt couldn’t have given that speech in Germany without serious blowback from the country’s still numerous and emboldened antisemites (Brandt donated his Nobel prize money to restore Venice’s Scuola Grande Tedesca synagogue, but ensured that this was kept secret until after his death).

All this to say that Germany’s reputation as “world champions of memory” is based on acts undertaken decades after the war. Some of Germany’s best-known Holocaust memorials are very recent, like the Wannsee Conference House (1992), the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (2005), and the Topography of Terror Museum in (2010).

Germany’s remembering includes an explicit act of forgetting — forgetting the role Germany’s business leaders and elites played in Hitler’s rise to power and the Nazi crimes that followed. For Speccher, the rise of neofacist movements in Germany can’t be separated from this selective memory, weighed down by anticommunist fervor.

And in East Germany, there was a different kind of incomplete rememberance. While the DDR’s historians and teachings emphasized the role of business in the rise of fascism, they excluded all the elements of Nazism rooted in bigotry: antisemitism, homophobia, sectarianism, and racism. For East German historians, Nazism wasn’t about these, it was solely “the ultimate end point of the history of capitalism.”

Neither is sufficient to prevent authoritarianism and repression, obviously. But the DDR is dust, and the anticommunism-tainted version of denazification is triumphant. Today, Europe’s wealthiest families and largest businesses are funneling vast sums into far-right “populist” parties that trade in antisemitic “Great Replacement” tropes and Holocaust denial:

https://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/Europe%E2%80%99s%20two-faced%20authoritarian%20right%20FINAL_1.pdf

And Germany’s coddled aristocratic families and their wealthy benefactors — whose Nazi ties were quietly forgiven after the war — conspire to overthrow the government and install a far-right autocracy:

https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/25-suspected-members-german-far-right-group-arrested-raids-prosecutors-office-2022-12-07/

In recent years, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about denazification. For all the flaws in Germany’s remembrance, it stands apart as one of the brightest lights in national reckonings with unforgivable crimes. Compare this with, say, Spain, where the remains of fascist dictator Francisco Franco were housed in a hero’s monument, amidst his victims’ bones, until 2019:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_S%C3%A1nchez#Domestic_policy

What do you do with the losers of a just war? “Least said soonest mended” was never a plausible answer, and has been a historical failure — as the fields of fluttering Confederate flags across the American south can attest (to say nothing of the failure of American de-ba’athification in Iraq):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De-Ba%27athification

But on the other hand, people who lose the war aren’t going to dig a hole, climb in and pull the dirt down on top of themselves. Just because I think Germany’s denazification was hobbled by the decision to lets its architects and perpetrators walk free, I don’t know that I would have supported prison for all ten million people captured by Article 10.

And it’s not clear that an explicit antifascism from the start would have patched the holes in German denazification. As Speccher points out, Italy’s postwar constitution was explicitly antifascist, the nation “steeped in institutional anti-fascism.” Postwar Italian governments included prominent resistance fighters who’d fought Mussolini and his brownshirts.

But in the 1990s, “the end of the First Republic” saw constitutional reforms that removed antifascism — reforms that preceded the rise of the corrupt authoritarian Silvio Berlusconi — and there’s a line from him to the neofascists in today’s ruling Italian coalition.

Is there any hope for creating a durable, democratic, anti-authoritarian state out of a world run by the descendants of plunderers and killers? Can any revolution — political, military or technological — hope to reckon with (let alone make peace with!) the people who have brought us to this terrifying juncture?

[Image ID: The Tor Books cover for ‘The Lost Cause,’ designed by Will Staehle, featuring the head of the snake on the Gadsen ‘Don’t Tread on Me’ flag, shedding a tear.]

Like I say, this is something I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about — not just how we might get out of this current mess, but how we’ll stay out of it. As is my wont, I’ve worked out my anxieties on the page. My next novel, The Lost Cause, comes out from Tor Books and Head of Zeus in November:

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250865939/the-lost-cause

Lost Cause is a post-GND utopian novel about a near-future world where the climate emergency is finally being treated with the seriousness and urgency it warrants. It’s a world wracked by fire, flood, scorching heat, mass extinctions and rolling refugee crises — but it’s also a world where we’re doing something about all this. It’s not an optimistic book, but it is a hopeful one. As Kim Stanley Robison says:

This book looks like our future and feels like our present — it’s an unforgettable vision of what could be. Even a partly good future will require wicked political battles and steadfast solidarity among those fighting for a better world, and here I lived it along with Brooks, Ana Lucía, Phuong, and their comrades in the struggle. Along with the rush of adrenaline I felt a solid surge of hope. May it go like this.

The Lost Cause is a hopeful book, but it’s also a worried one. The book is set during a counter-reformation, where an unholy alliance of seagoing anarcho-capitalist wreckers and white nationalist militias are trying to seize power, snatching defeat from the jaws of the fragile climate victory. It’s a book about the need for truth and reconciliation — and its limits.

As Bill McKibben says:

The first great YIMBY novel, this chronicle of mutual aid is politically perceptive, scientifically sound, and extraordinarily hopeful even amidst the smoke. Forget the Silicon Valley bros — these are the California techsters we need rebuilding our world, one solar panel and prefab insulated wall at a time.

We’re currently in the midst of a decidedly unjust war — the war to continue roasting the planet, a war waged in the name of continuing enrichment of the world’s already-obscenely-rich oligarchs. That war requires increasingly authoritarian measures, increasing violence and repression.

I believe we can win this war and secure a habitable planet for all of us — hell, I believe we can build a world of comfort and abundance out of its ashes, far better than this one:

https://tinyletter.com/metafoundry/letters/metafoundry-75-resilience-abundance-decentralization

But even if that world comes to being, there will be millions of people who hate it, a counter-revolution in waiting. These are our friends, our relatives, our neighbors. Figuring out how to make peace with them — and how to hold their most culpable, most powerful leaders to account — is a project that’s as important, and gigantic, and uncertain, as a just transition is.

Next weekend, I’ll be at San Diego Comic-Con:

Thu, Jul 20 16h: Signing, Tor Books booth #2802 (free advance copies of The Lost Cause— Nov 2023 — to the first 50 people!)

Fri, Jul 21 1030h: Wish They All Could be CA MCs, room 24ABC (panel)

Fri, Jul 21 12h: Signing, AA09

Sat, Jul 22 15h: The Worlds We Return To, room 23ABC (panel)

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this thread to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/07/19/stolpersteine/#truth-and-reconciliation

[Image ID: Three 'stumbling stones' ('stolpersteine') set into the sidewalk in the Mitte, in Berlin; they memorialize Jews who lived nearby until they were deported to Auschwitz and murdered.]

#pluralistic#stolpersteine#historians' dispute#Historikerstreit#nazis#godwin's law#mussolini#berlusconi#italy#antifa#fascism#history#truth and reconciliation#the lost cause#denazification

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

Least said, soonest mended, Your Majesty, isn’t the advice for every occasion.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

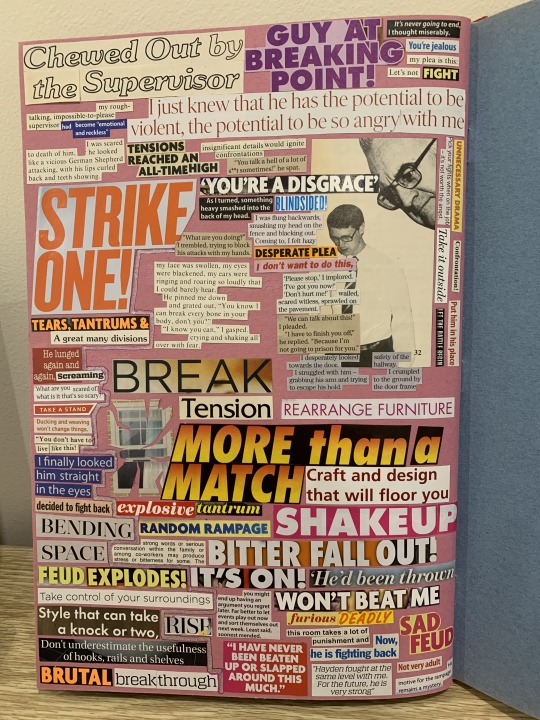

AT LAST, THE X-X COLLAGE IS DONE! Transcript under the cut.

Also, I had to do a little emergency surgery on the scrapbook because some of the pages were falling out. If you ever see me upload a collage page that has pink stitches down one side, shhh no you didn’t =)

Chewed Out by the Supervisor

GUY AT BREAKING POINT!

It’s never going to end, I thought miserably.

my rough-talking, impossible-to-please supervisor

had become “emotional and reckless”

I just knew that he has the potential to be violent, the potential to be so angry with me.

I was scared to death of him, he looked like a vicious German Shepherd attacking, with his lips curled back and teeth showing.

TENSIONS REACHED AN ALL-TIME HIGH

insignificant details would ignite confrontations

“You talk a hell of a lot of s**t sometimes!” he spat.

UNNECESSARY DRAMA

Pick your fights when on the job - it’s not worth the angst.

Confrontation!

Take it outside

Put him in his place

LET THE BATTLE BEGIN

‘YOU’RE A DISGRACE’

As I turned, something heavy smashed into the back of my head.

BLINDSIDED!

I was flung backwards, smashing my head on the fence and blacking out. Coming to, I felt hazy

“What are you doing?” I trembled, trying to block his attacks with my hands.

my face was swollen, my eyes were blackened, my ears were ringing and roaring so loudly that I could barely hear.

He pinned me down

and grated out, “You know I can break every bone in your body, don’t you?”

“I know you can,” I gasped.

crying and shaking all over with fear.

DESPERATE PLEA

I don’t want to do this,

‘Please stop,’ I implored.

‘I’ve got you now!’

‘Don’t hurt me!’ wailed, scared witless, sprawled on the pavement.

“We can talk about this!” I pleaded.

“I have to finish you off,” he replied. “Because I’m not going to prison for you.”

I desperately looked towards the door.

I struggled with him - grabbing his arm and trying to escape his hold.

safety of the hallway.

I crumpled to the ground by the door frame

STRIKE ONE!

TEARS, TANTRUMS &

A great many divisions

He lunged again and again, Screaming

‘What are you scared of? what is it that’s so scary?’

TAKE A STAND

Ducking and weaving won’t change things.

“You don’t have to live like this!

I finally looked him straight in the eyes

decided to fight back

BENDING SPACE

FEUD EXPLODES!

Take control of your surroundings

Style that can take a knock or two,

Don’t underestimate the usefulness of hooks, rails and shelves

BRUTAL breakthrough

BREAK Tension

REARRANGE FURNITURE

MORE THAN A MATCH

Craft and design that will floor you

explosive tantrum

RANDOM RAMPAGE

SHAKEUP

strong words or serious conversation within the family or among co-workers may produce stress or bitterness for some. The

BITTER FALL OUT!

IT’S ON!

you might end up having an argument you regret later. Far better to let events play out now and sort themselves out next week. Least said, soonest mended.

“I HAVE NEVER BEEN BEATEN UP OR SLAPPED AROUND THIS MUCH.”

‘He’d been thrown

WON’T BEAT ME

furious

DEADLY

this room takes a lot of punishment and Now, he is fighting back

“Hayden fought at the same level with me. For the future, he is very strong”

SAD FEUD

Not very adult

His motive for the rampage remains a mystery.

#the hotel podcast#my stuff#god in heaven this one’s wordy#I’m gonna upload another collage as soon as I figure out how to tag it#Collage#x-x

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

So how are you doing surviving the kidmagedon? Hope you'll get some recompense those kids cost you a lot of expensive stuff.

They are

gone

I haven’t asked the parents to replace what was lost. It isn’t worth the hassle. I did quietly mention what happened and they were very apologetic. Least said, soonest mended and all that.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wanted to write a little fic about James meeting his father again after all these years ...or at least a little bit of the aftermath of it and the feelings that came with it and the circumstance around it.

Obligations are Just a Choice for Some and a Duty to Others

Words: 1564

Character: James, his dad, and Theo, (and a random nurse)

TWs: Mentions of Abuse and a brief description of it

Familial obligation.

James wanted to laugh. The bitter kind of laugh; the one where you know that if you don’t you’ll either scream till your voice turns raw or sob till you drown in your own tears.

How dare he. How dare that man…after all these years…

“James—”

“James!”

He ignored the calls of the nurse who was trying to catch up to him.

She gave one last desperate attempt and reached out to grab his shoulder, “James…”

“What?” He snapped, face red with anger, his heart pounding from it too. Were his ears ringing from it as well or were his hearing aids acting up?

“How are you just going to walk away from him like that?” The nurse tried to berate.

James snorted, “Trust me, very easily.”

“Although, it would be a lot easier if he didn’t bash my fucking leg in with a baseball bat.” He continued, slamming his cane onto the ground for emphasis.

She seemed too shocked at his answer if the wide eyes and stammering was any indication.

“How come you never said anything?” The nurse said, eyebrows knit in confusion and sympathy.

James clenched his teeth and sighed, “It’s already hard enough to get people to think that I’m competent at my job; I don’t need another layer of pity on top of it.” He was finding it hard to swallow, “And besides, it doesn’t make for a good conversation or bedside manner, now does it?”

“I suppose not…” She agreed hesitantly, eyes drifting to the floor, purposefully away from where his cane was.

“Listen, I appreciate you trying to mediate, honest, but some things are better left broken and un-mended.”

“So what do you plan to do?” The nurse asked, shuffling uncomfortably in place.

“Hand him off to another doctor, inform security to who he is and give them instructions to make sure he leaves me alone, and if he doesn’t die, the second he’s cured, get them to escort him out at the soonest possible moment.”

“But—”

“But what?” James echoed, “But he’s your father? But he’s family?”

“I know what he—”

“You don’t know anything!” He cut her off, uncaring that he was starting to cause a disturbance, “like I said, I know you mean well, but drop it.”

James swiftly turned away from her and started storming off and down the hallway, “I’m taking a break; don’t bother me.”

James pretended it was the chill of the air that stung his face and not the tears that were threatening to run down it.

He watched the people as they passed by from his sad little place on the sad little bench. James wasn’t a jealous or bitter person. However, sometimes he found himself cursing at a god he on longer believed in and wanting answers as to why he couldn’t have one of the most basic things a human should be given; parental love.

“Rough day?”

Well, he wasn’t expecting to hear that voice.

He managed a smile and turned towards the man who had spoken, “Hello, Theo.”

“Mind if I sit?” Theo asked, pointing to the bench as the other clutched a box to his chest.

“All yours.” James replied, and scooted over a bit.

“So, what’s bothering you?” Theo questioned, gently placing a hand on the others’ back.

James had never been a big fan of being touched but over the last few years had learned to find comfort in it. Even still, he had a hard time not tensing immediately after any contact had been made. However this time James found himself doing something completely unexpected. First, placed his cup of coffee to his unoccupied side, almost robotically, face blank. Then he nearly tossed himself into the other, wrapping his arms around the man like he was his life line.

“Woah!” Theo said, “That bad?”

All James could do was give a small pathetic sob as he nodded and buried his head further into the other’s neck; he smelled like freshly baked oatmeal cookies. They stayed together like that for a few moments; the only thing interrupting their silence was a few muffled sobs and hiccups from the distressed man.

“Sorry.” James said as he pulled away.

Theo kept his hand on the other’s back and rubbed it “Hey, no worries.”

“Listen, I know you like to keep things to yourself, and that’s okay,” Theo comforted, “but I am here if you need to talk or just have a shoulder to lean on. August and Eric too.”

James smiled somberly, “Thank you.”

“I brought you some cookies.”

“Lucky me.”

Theo handed James the box and watched as he opened it eagerly. They weren’t as young as they used to be but he enjoyed the moments where James’ excitement would get the best of him, as few and far between as they were. He always was a shy and reserved man…

“My father’s in the hospital. They assigned him as my patient.” James stated like he was saying the sky was blue.

Theo found out the hard way that yes, it was in fact possible to choke on air and your hear that has leaped up into your throat at the same time, “They what?!”

“Well to be quite fair, they had no really clue about how — and pardon my language— much of bastard that dickhead fucking was,” James said, his words a bit muddled from the cookie he had shoved into his mouth.

“So what did you do?”

James paused, and furrowed his brows, “ I wish I could say that I stood up for myself but…” He dropped his head in shame, “In reality I just walked into the room, let him have his whole speech about how ‘proud’ he was of me and how much of a good son I would be if I donated some bone marrow to him or convinced Jess to…”

“That must have been hard…” Theo looked down at his hands as he clasped them together.

" ‘Familial obligation’ he said,” James mocked, “As if he knows the meaning of those words.”

“I mean—” James looked up at the sky, “what does he know of the meaning of that phrase! Familial Obligation? Where was his familial obligation all those years ago, huh?”

James was starting to get upset again, his chest rising and falling rapidly as memories he had tried to suppress for years came flooding all back, “Why is it that everyone always questions why the child feels no obligation to repair the relationship when the parent was the one who ruined it in the first place?!”

“I—” Theo tried to speak.

“— I mean I was a kid, what was I supposed to do?” His lips were wobbling, eyes wide with fear, “What am I supposed to do now? If I help him I might as well be saying that I forgive him. If I don’t I might as well just be his killer, and everyone will think I’m in the wrong and that I'm heartless; I mean, why wouldn’t they? They don’t know anything about me!”

James gripped at his chest, “My whole life has been spent in fear of that man. I can’t…I can’t just—”

“It’s okay—”

“No it isn’t!” James barked, fear utterly consuming him as he jolted up from the bench, cane falling on the concrete below, “What the fuck is supposed to be okay? There’s nothing okay with this! This situation isn’t okay! I’m not fucking okay!”

Theo slowly stood up, arms out in a comforting gesture, “You’re right. It’s not okay. You shouldn’t have to deal with this, you shouldn’t have this weight on your shoulders.”

“But I do…” James sniffed.

“But you do..” Theo sadly confirmed.

“I’m so tired…” James admitted, his voice wavering, almost giving out.

“I know.”

“What do I do?”

Theo wished he had an actual answer as he brought James back into a hug, “I’m sure whatever decision you make will be the right one.”

“That was a non-answer if I’ve ever heard one.” James laughed bitterly.

“I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be.” James wiped away his tears.

“It’s hard. Sometimes you want to forgive them because they raised you but a part of you knows that they can’t be forgiven for what they’ve done. A part of you will always yearn for the way it was before but there’s no going back,” Theo bent down to grab the cane, “If you ask me, his comfort and anyone else's comfort shouldn’t be worth the risk of your safety.”

James gently grabbed the cane, “Thank you…”

“Maybe you should take some personal time?” Theo suggested.

“Yeah…I think I should.”

“Maybe you could get a free bereavement period out of it,” Theo jested.

There it was; that little smile that James liked to hide, the one where he knew something shouldn’t be funny but couldn’t act like it wasn’t. Theo was very happy to see it.

“I’m gonna…go clock out now.” James said awkwardly gesturing to the hospital doors as he turned to leave.

“Mind if I drive you home?”

James turned around, “I’d like that.” He said smiling before turning back.

“You’re just happy you get to eat the rest of these cookies in the car!”

The bark of laughter that erupted from James was all the comfort and confirmation that Theo needed. He’d bake the man some more when they got home.

Screw that fucking bastard.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Cousin Leofstan is putting himself about,’ Gríma says. He tucks his hands up his outer sleeves. ‘I always thought that it must be a little tense between you all. Not that it’s any of your fault what happened all those years ago with your grandfather chucking out fair Gundwyn but still…does he chafe about it?’

‘Who?’

‘Leofstan. He should be third marshal. Technically.’

Éomer turns to face Gríma who remains looking out over the fields, the crops, the horses, cattle, homesteads. The older man’s profile is sharp, shattered glass. Eyes deep, watchful, and wolf-hungry. Éomer waits, thinking it evident that he wants to know what Gríma is up to. Gríma seems disinterested in enlightening him.

There are a few crickets sawing into the warm air. Also, distant laughter and music from the main grounds. Occasional applause. Trust Gríma to haunt the hinterlands of happy occasions. He can’t help it, Éomer suspects. It’s as part of him as his unnatural stare and ability to cut through a man with insight he should not have.

‘What is that supposed to mean?’ Éomer finally asks.

‘Nothing, save that your aunt Gundwyn was the eldest of the sisters and therefore her progeny should have received your marshallate. Naturally Fengel had opinions on her choice of partner, but the least said about that unfortunate kingship, soonest mended.’

‘You’re bold today.’

‘Nay, my lord, I simply speak as I find. I suppose I am trying to say something, in a manner of speaking. A warning, perhaps.’

‘Why should you warn me?’

Gríma flicks eyes over, a shadowed expression. His head dips for a moment as he gathers his thoughts then he lifts it and turns to full-face Éomer.

‘We’ll be in the midst of war soon. Indeed, some would argue we’re already there. We need surety in our leadership—I believe you capable. I would have you remain third marshal. Others might have differing views on the matter. That is what I am saying.’

‘Riddles,’ Éomer sneers. He advances so they’re inches from each other. ‘All you ever give people are riddles but you label them advice as if calling them by a different name will change their nature.’

‘Names are terribly important when it comes to changing one’s nature. Or signifying it. Defining it. I define myself one way, you define me another. And it’s not a terribly flattering definition, I suspect.’

‘You’re work is plain to see,’ Éomer continues, ignoring Gríma’s response. ‘You’ve been attempting to sow discord between me and my kin for the last two years. But I’ll not take to distrusting my cousins simply because you think one feels slighted. Leofstan has only ever been a friend and ally. Why should I trust your word over his? He, at least, is straight and true. You, on the other hand, bend like willow reed and are as crooked as gnarled oak.’

‘I only meant to bring the issue to your awareness,’ a sloping shrug, ‘you may take it or leave it. I like you, Éomer, but it is little skin off my nose if you decide to ignore my advice. I’ll riddle you this, though, what has life but no shadow?’

‘A flame.’

‘A man who is not present where and when he is needed, and so therefore we have no shadow of his to mark. Leofstan might breed entitlement in his heart, but he’s not the only cousin of which I speak. Has Théodred given you that back-up you asked for a month ago?’

Éomer opens his mouth—sees the winding road of this conversation, as twisted as a forest creek, and so shakes his head. Puts on a cold smile. Says that Gríma will get no more from him, today. If Gríma has anything useful to say, he had best speak plainly, otherwise Éomer considers their conversation complete.

Gríma slithers out a hand with its long-boned fingers and brushes a bit of dust from Éomer’s shoulder. A lightning sharp static seems to go through him at the touch. Patting Éomer’s arm, Gríma gives a mirthless smile, and makes his way back towards the crowds.

Grima out here shit-disturbing.

Anyway, I decree June 30 national Grima/Eomer day, so here you all go.

#what makes a kynge#Kynge sees us meeting Theoden's sisters - or some of them - the unnamed ones get names#lord of the rings#eomer#griomer#grima wormtongue#writing#lotr

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

General: Best Wish!Verse

“I wish… that Emma Swan’s wish….” A new realm - a Wish!Realm, and it brought Rumbellers - or should that be ‘Wish!Rumbellers’ much heartache, with Rumple alone and Belle… Well, yes. Least said - soonest mended.

In the category of Best Wish!Verse, the winner of the 2024 Chipped Cup Award is…

Deception by @eirian-houpe

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

After Elon Musk rolled out a confusing and ever-evolving new verification system on Twitter this week, parody accounts posing as large corporations spread confusion on the site. The most prominent was a fake account for the pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly, which announced that insulin would now be free to customers. Soon the official Lilly account stepped in to refute the news, issuing a statement that apologized for the misunderstanding but avoided, of course, apologizing for how expensive insulin is in the first place. Lilly’s hasty apology is the latest in what Jill Lepore identifies in this week’s issue as a required—and often deeply unsatisfying—ritual of corporate communications in the social-media age. Everyone knows that companies sometimes have to say sorry, but do they ever mean it? And does it really make a difference if they do? “The practice of establishing and enforcing strict requirements for public apology is not a human universal,” Lepore writes. “It happens only here and there, and now and again. You see it in fiercely sectarian times and places—like twenty-first-century social media, or seventeenth-century New England.” You think it’s bad now? Just imagine the Puritans on Twitter.

Whose P.R.-purposed apology was worse? Al Franken’s or Louis C.K.’s? The Equifax C.E.O.’s (for a cybersecurity breach) or Papa John’s (for a racial slur)? Awkwafina’s (for cultural appropriation) or Lena Dunham’s (for Lord knows what)? At SorryWatch.com and @SorryWatch, Susan McCarthy and Marjorie Ingall have been judging the adequacy of apologies and welcoming “suggestions for shaming” since 2012. “There are a lot of awful apologies out there,” the SorryWatchers write. “Apologies that make things worse, not better. Apologies that miss the point. Apologies that are really self-defense dressed up as an apology. Apologies that add insult to injury. Apologies that are worse than the original offense. Apologies so bad people should apologize for them.” McCarthy and Ingall are releasing a new book next year, “Sorry, Sorry, Sorry: The Case for Good Apologies.” Meanwhile, on their Web site they’ve got rules—“Six steps to a good apology”—and categories for classifying defective ones: “Be VEEERY CAAAREFUL if you want to provide explanation; don’t let it shade into excuse.” Heaven forfend.

“Least said, soonest mended” is advice from another century, candle and quill, ox and cart. This past March, the day after Will Smith smacked Chris Rock at the Oscars and failed to apologize to him during his acceptance speech, he apologized on his Instagram account: “I was out of line and I was wrong.” Twitter blew its top! “This is bullshit,” one guy tweeted. “Any normal person is in jail.” Plainly, the Instapology was insufficient. In July, Smith apologized again, in a nearly six-minute video in which he looked as harried and trapped as Steve Carell in “The Patient,” a prisoner in a basement rec room. “Disappointing people is my central trauma,” Smith said into the camera or, actually, multiple cameras. “I am trying to be remorseful without being ashamed of myself, right?” Twitter blew its top! It was either not enough or, oh, my God, please stop. One online viewer sympathized: “Literally me when my mom forces me to apologize to my siblings.” As for Chris Rock, he reportedly said, onstage, “Fuck your hostage video.” By then, Twitter was blowing its top about something else.

It’s easy to blow your top, God knows. If you’re being treated like crap, and nothing you’ve tried has put a stop to it, or if the former President of the United States keeps on saying horrible, wretched things, and you notice that some rich nitwit is getting slammed on Twitter for doing the same thing that’s been done to you, or for saying what the ex-President just said, it can feel good to watch that nitwit burn. But that feeling won’t last. And when that nitwit apologizes it won’t be enough. And the world will have become just a little bit rottener.

Rating apologies and listing their shortcomings started out as a BuzzFeed kind of thing, and then it pretty quickly became a corporate kind of thing: human resources, leadership institutes, political consulting. In 2013, the Harvard Business Review published an essay on the Power Apology. Knowing how to apologize on Twitter became crucial to brand management. “It’s easy to say sorry, but knowing how to say it effectively on Twitter is an essential skill that both brands and celebrities should learn,” a communications manager advised not long afterward, offering nine lessons “on the art of the Twitter apology.” You could do it well, or you could do it badly. Likely, this could be quantified: you’d see it in the price of your stock, the number of your Twitter followers, or the percentage change in your Netflix viewership. As of 2022, even Forbes rates apologies. It seldom helps your vote count, though: politicians who apologize tend to suffer the consequences, which is why they generally brazen these things out.

It’s a good idea to say you’re sorry when you screw up, and to say it well, and to mean it, and to try to make amends. But are people getting worse at that? Or are celebrity publicists, political advisers, corporate lawyers, higher-ed administrators, and media-relations departments just avoiding lawsuits, clearing profits, heading off student protests, and directing news stories by advising people to (a) demand apologies and (b) make them? “Examples of failed apologies are everywhere,” the psychiatrist Aaron Lazare wrote in “On Apology,” a book published not last week but nearly two decades ago. Distressed at a seeming explosion of cheap, showy, and insincere apologies, Lazare got curious about where they’d all come from, like the day you find ants swarming your kitchen counter and yank open all the cupboards, exasperated. He dated what he called the “apology phenomenon” to the nineteen-nineties, but he struggled to understand what had driven this change. He suspected that it may have been due, in part, to “the increasing power and influence of women in society,” because women apologize a lot, he explained, and like to be apologized to. As far as I know, no one asked him to apologize for that comment. But if he’d made it today he’d be in the soup.

Rituals of atonement and forgiveness lie at the heart of most religions, a testament to the human capacity for grace. On Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, Jews fast and pray and repent. Jesus brought this spirit to Christianity and taught his followers to pray to God to “forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.” The early Christian church developed what became the Sacrament of Reconciliation: confession, and penance. There are many steps to atonement in Islam, from admitting a wrong to making restitution and asking for God’s forgiveness. Jews, Christians, and Muslims make themselves right with God. Buddhists, who worship no god, make themselves right with other people. Hindus practice Prayaschitta, rituals of absolution. Mainly, it’s the forgiveness and the atonement that matter.

Apology, though, has a different history. You can confess without apologizing and you can apologize without confessing, and this might be because, historically, an apology is a justification—a defense, not a confession. As the philosopher Nick Smith pointed out in “I Was Wrong” (2008), the word “apology,” in English, didn’t suggest a statement of regret until around the sixteenth century, when, in Shakespeare’s “Richard III,” Buckingham begs Richard’s pardon, for interrupting his prayers, and Richard says, “There needs no such apology.” Medieval Christians practiced what the historian Thomas N. Tentler called “a theology of consolation,” consisting of four elements—sorrow, confession, penitence, and absolution—whose purpose was reconciliation with God and with the body of the faithful. In “Forgiveness: An Alternative Account,” Matthew Ichihashi Potts, a professor of Christian morals at Harvard Divinity School, offers what he calls “a modest theological defense of forgiveness.” His argument follows that of the philosopher Martha Nussbaum, who, in “Anger and Forgiveness” (2016), argued that forgiveness isn’t salutary for either party if, in order to give it, you insist on an apology. Potts calls this “the economy of apology.” It’s not better than vengeance, since to demand an apology and to delight in the offender’s grovelling is vengeance by another name. His evidence doesn’t come from Twitter; it comes mainly from novels, including Marilynne Robinson’s “Gilead” and Toni Morrison’s “Beloved.” Forgiveness, for Potts, is not an exchange—forgiveness granted in return for the opportunity to witness a spectacle of abasement and self-loathing—but a promise not to retaliate. Demanding an apology in exchange for forgiveness can never constitute healing, or deliver justice; it is, instead, a pleasure taken by people who delight in witnessing the suffering of those in their power (if only briefly). There is no such thing as a failed apology, then, only an abuse of power, because all forgiveness, Potts writes, “begins and ends in failure”: it does not, and cannot, redeem or undo pain and loss; it can only demand the necessary attention to pain and loss, as a reckoning, as an act of grief. Forgiveness is, therefore, a species of mourning, a form of sorrow.

Within the early Christian West, acts of public supplication—begging pardon—required confession and might require restitution, but not the scripted public apology in the sense the SorryWatchers want. The same distinction can be made within the history of Judaism. In the twelfth century, the Spanish-born Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, known as Maimonides, wrote a commentary on the Torah and the Talmud that included a section on teshuvah, or “repentance,” an extended reflection on the commandment that “the sinner should repent of his sin before God and confess.” But, as the Jewish historian Henry Abramson remarked in a recent study, “The Ways of Repentance,” Maimonides warned against public confession that “can also be an expression of personal arrogance: ‘Look how good I am at doing teshuvah! ’ ” Watch my apology video on YouTube!

In “On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World,” the rabbi Danya Ruttenberg translates Maimonides into a step-by-step guide for our world, for which she provides modern-day examples. The first step is “naming and owning harm” (one of her examples: “I finally understand how my decision to hold a writer’s retreat at a plantation sanitizes the horrors of slavery”); the second is “starting to change.” Step three: restitution. Step four: apology. Step five: making different choices. These are kindhearted ideas, and Ruttenberg’s book is full of hope and counsel about repair through restitution. But her prescriptions also come close to insisting on the suppression of dissent. She says that “starting to change,” for Maimonides, might have involved “tearful supplication,” but that “these days this process of change might also involve therapy, or rehab, or educating oneself rigorously on an issue about which one had been ignorant or held toxic opinions.”

“This book started on Twitter,” Ruttenberg writes, which is something of a tip-off. “Twitter gamifies communication,” the philosopher C. Thi Nguyen has argued; it’s custom-built to do things like score apologies, to drag users into a rating system that has nothing to do with morality. An unforgiving god rules Twitter, where the modern economy of apology runs something like this: If you express what I believe to be a toxic or ignorant opinion, you must apologize according to my rules for apology. If you do, I may forgive you. If you don’t, I will punish you, and damn you unto eternity.

The practice of establishing and enforcing strict requirements for public apology is not a human universal. It happens only here and there, and now and again. You see it in fiercely sectarian times and places—like twenty-first-century social media, or seventeenth-century New England.

Consider a case from October, 1665, when the Massachusetts legislature assembled in Boston to attend to a docket of ordinary affairs, a day in the life of a puritanical theocracy. It set the price of grain: wheat, five shillings a bushel; barley, four shillings sixpence; corn, three shillings. It addressed a petition filed by three Native men, including the Pennacook sachem Wanalancet, regarding an Englishman’s claim to an island on the Merrimack River. It warned one unhappy, estranged couple, Mr. and Mrs. William Tilley, that he must “provide for hir as his wife, & that shee submit hirselfe to him as she ought,” or else he would be fined and she would be imprisoned. In honor of God’s having graced the colony with abundant rain during the summer and mercifully diverted a fleet of Dutch ships from an invasion, the legislature appointed November 8th “to be kept in solemn thanksgiving,” but, because a plague was still raging in London, a sign of God’s wrath, it declared November 22nd “a solem day of humilliation.” And it condemned five men who had dared to practice a heretical religion, Baptism, at which announcement one colonist, Zeckaryah Roads, blurted out “that the Court had not to doe wth matters of religion.” He was detained as a result.

For the things they said—words whispered, grumbles muttered, prayers offered, curses shouted—dissenters, blasphemers, and nonconformists in seventeenth-century New England faced censure, arrest, flogging, the pillory, disenfranchisement, exile, and even execution. Quakers might have their ears cut off. For holding toxic opinions, one blasphemer was sentenced to have the letter B “cutt out of ridd cloth & sowed to her vper garment on her right arme.” Those who wished to avoid or mitigate these consequences might apologize in public. Mostly, apologies followed a script. The Six Steps to a Good Apology! Disappointing People Is My Central Trauma: How to Avoid the Eight Worst Apologies of 1665! Earlier that year, just months before Zeckaryah Roads dared to voice dissent, Major William Hathorne, of Salem—an ancestor of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s—issued a public apology for his own (now lost to history) error: “I freely confesse, that I spake many words rashly, foolishly, & unadvisedly, of wch I am ashamed, & repent me of them, & desire all that tooke offence to forgive me.” That did the trick. You went off script at your peril, as the historian Jane Kamensky demonstrated in her masterly book “Governing the Tongue” (1997). In the sixteen-forties, observers deemed Ann Hibbins’s apology—essentially, for being abrasive, and a woman—“very Leane, & thin, & poore, & sparinge.” It saved her neck, but not for long: in 1656, Hibbins was hanged to death as a witch. Still, there was one other option: after John Farnham refused to apologize for countenancing heresy, and was therefore banished, he said the day he was kicked out of the church “was the best day that ever dawned upon him.” I mean, fuck it, there was always Rhode Island.

Lately, online, you can find modern apologies ranked by the same standards once so punctiliously applied by Puritan divines. “I doe now in the presence of god & this reverand assemblage freely acknowledg my evell,” Henry Sewall confessed in a church near Ipswich in 1651, although, as he pointed out, he’d been forced to make that apology “as part of ye sentence” he’d been given by the Ipswich court. He squeaked by with that one, but just barely. Modern SorryWatchers might rate it Garrison Keillorian.

In 1665, for intimating that the government ought not to banish people for being Baptists, or kill them for being Quakers, Zeckaryah Roads did what he had to do, as chronicled in the meeting records, “acknowledging his fault, & declaring he was sorry he had given them any offence, &c.” Easy to say from here, of course, but I wish to hell he hadn’t.

The twenty-first-century culture of public apology has its origins in the best of intentions and the noblest of actions: people seeking collective justice without violence for terrible, unimaginable acts of brutality, monstrous wickedness, crimes against humanity itself. In the aftermath of the Second World War, churches and nation-states began issuing apologies for wartime atrocities and historical injustices. Some of the abiding principles that lie behind this postwar wave of collective apologies also found expression in “restorative justice”—individuals making amends to their victims, sometimes as an alternative to incarceration or other kinds of force and violence. The idea gained influence in the nineteen-seventies, when it intersected with the victims-rights movement, and its particular demands for apology as remedy. And you can easily see why. Prosecutors—for years, decades, centuries—had failed to act on allegations of sexual misconduct, had ignored or suppressed evidence of police brutality and predatory policing; in a thousand ways, the criminal-justice system had failed women and children, had failed the poor and people of color. For some, “restorative justice” held out the prospect of a better path. By the nineteen-nineties, schools and juvenile-justice systems had begun using restorative-justice methods, often requiring, of public-school students, public apologies. Meanwhile, in the United States, church membership was falling from around seventy-five per cent in 1945 to less than fifty per cent by 2020. In many quarters, public acts began taking the place of religious ritual, political ideologies replacing religious faith. The national public apology took on the gravity and solemnity of a secular sacrament: Ronald Reagan apologizing, in 1988, for the imprisonment of more than a hundred thousand Japanese Americans during the Second World War (and providing limited reparations); David Cameron apologizing, in 2010, for Bloody Sunday; or the Prime Ministers of Canada apologizing, in 2008 and 2017, for the practice of taking Indigenous children from their homes and confining them to schools where, maltreated, neglected, and abused, they suffered and died.

Apology came to play a role, too, in therapy, including family therapy, in twelve-step recovery programs, and in H.R. dispute-resolution procedures. Conventions that were established for heads of states and churches making public apologies to entire peoples against whom they had committed atrocities came to be applied to apologies from one individual to another, for everything from violent crime to petty insult. The person became the collective. Eve Ensler’s 2019 book, “The Apology,” in which she imagines the apology her father never offered for sexually abusing her, is dedicated to “every woman still waiting for an apology.” The particular injury became the universal harm. “We all cause harm,” Danya Ruttenberg writes in her book on repentance. “We have all been harmed.”

But the origins of the Twitter apology orgy lie elsewhere, too, and especially in the idea that many kinds of speech can be harm, a conviction central to the brand of feminism founded in the nineteen-nineties by the legal theorist Catharine MacKinnon. (Her book “Only Words” was published in 1993.) In 2004, in “On Apology,” Aaron Lazare tried to figure out when the number of public apologies began to explode. He counted and identified a rise in the number of newspaper articles about apologizing, beginning his analysis in the early nineteen-nineties and identifying a peak in 1997-98. He found this puzzling. But, historically, it makes sense: his chronology nicely lines up with Anita Hill’s testimony at the Clarence Thomas hearings, in 1991, and with the breaking of the Monica Lewinsky scandal, in 1998. Thomas maintained his innocence, and although Clinton went on television later that year and admitted to the relationship, many viewers found his apology inadequate. And neither man seemed sorry, either, except insofar as they both quite plainly felt very, very sorry for themselves.

The refusal of Thomas and Clinton to apologize for the ways in which they had harmed women took place on television. And the whole spectacle, with its scripted expectation of apology and contrition, drew its sensibility from television. In the nineteen-eighties and nineties, the stock soap-opera plotline—betrayal, hurt feelings, and misunderstanding followed by tearful apology, reconciliation, and reunion—became a hallmark of the daytime talk-show circuit. Oprah and Phil Donahue staged churchy apologies in front of studio audiences, choreographed for maximum emotional intensity, and advancing the idea that every possible political, economic, or social injustice, from child abuse to police brutality and employment discrimination, could be addressed by a two-shot, a few closeups, and Kleenex. Donahue mounted an especially perverse sorrywatching spectacle in 1993. The year before, after a jury acquitted four Los Angeles policemen who beat Rodney King and riots broke out in angry, anguished protest, a group of Black men pulled Reginald O. Denny, a white man, out of his truck and beat him nearly to death. Henry Keith Watson, charged with attempted murder, was found not guilty, and was convicted only of misdemeanor assault. After Watson got out of jail, Donahue brought Denny and Watson together in front of an almost entirely white audience for a two-part apology special. “Are you sorry?” Donahue asked Watson, again and again, as the audience grew tense and even tenser. “I apologize for my participation in the injuries you suffered,” Watson said to Denny. Then Watson eyed the audience: “Is everybody happy now?” Everybody was not.

Demanding public apologies on daytime television and deeming those apologies insufficient was an occasional thumb-wrestling match between two seven-year-olds sitting on a green vinyl school-bus seat on the ride to second grade compared with the daily, Roman Colosseum-style slaughtering that takes place online. It’s not that people don’t do and say terrible things for which they ought to atone. They do. Some of those things are crimes. Many are slights. Very many are utterly trivial. A few are almost unspeakably evil. But, on Twitter at its worst, all harm is equal, all apologies are spectacles, and hardly anyone is ever forgiven.

In 2017, at the height of the #MeToo movement, Matt Damon tried to rate harm. “You know, there’s a difference between, you know, patting someone on the butt and rape or child molestation, right?” he said in an interview on ABC News. “They shouldn’t be conflated, right?” At that, Minnie Driver tweeted her ire, and later told the Guardian, “How about: it’s all fucking wrong and it’s all bad, and until you start seeing it under one umbrella it’s not your job to compartmentalise or judge what is worse and what is not.” Damon apologized, and said that he’d learned to “close my mouth.”

In 1993, Phil Donahue seemed to think that, by asking Henry Keith Watson to apologize to Reginald Denny in that studio, he was bravely addressing the problem of racism in America. Twenty years from now, what’s been happening on Twitter will likely look exactly as grotesque and cruel and ineffective as that two-part, syndicated apology special. Will Donald Trump or anyone in his inner circle ever apologize for anything—for tearing toddlers from their parents’ arms, for inciting neo-Nazis, for grift, fraud, sedition? Never. Will responding to the gaffe of the day by demanding a six-step apology usher in an age of justice for all, or an end to iniquity? No. There’s a reason Puritanism did not prevail in America; it tends to backfire. In 2018, during an exchange on Twitter, the television writer Dan Harmon apologized for sexually harassing the writer Megan Ganz, and then made a heartfelt video, elaborating. “We’re living in a good time right now, because we’re not going to get away with it anymore,” he said, referring to sexual misconduct. And I hope that’s true. But very little evidence suggests that calling people out on Twitter, self-righteous indignation followed by cynical apology, is making the world a better place, and much suggests that the opposite is true, that Twitter’s pious mercilessness is generating nothing so much as a new and bitter remorselessness.

“I don’t give a fuck, ’cause Twitter’s not a real place,” Dave Chappelle said last fall, in his Netflix special “The Closer.” In June, on the Amazon Prime series “The Boys,” a made-for-television Captain America-style superhero named Homelander, who is secretly a villain, recited a rehearsed apology on television, only to unsay it later, in an unscripted outburst. “I’m not some weak-kneed fucking crybaby that goes around fucking apologizing all the time,” he said, seething. “I’m done. I am done apologizing.” Around the time the episode appeared, the actor who plays Homelander, Antony Starr, who was found guilty of assault and released on probation, told the Times, unabjectly, “You mess up. You own it. You learn from it.” No “I am listening,” no “I am going to rehab.” None of it. It was as if he got away with going off-script because his character already had. And Homelander won’t be the last to make that “I’m done” speech. “I’m done saying I’m sorry,” Alex Jones yelled in a courtroom in September during a trial to assess the money he’ll be required to pay the parents of very young children who were killed in a mass shooting, a shooting that Jones has for years insisted never happened, because those children, he told his audience, never existed. Jones has been found liable for defamation. Even the hundreds of millions of dollars in damages he was ordered to pay to the families whose despair he worsened, and on whose affliction he feasted, goes nowhere near far enough. And neither does any apology.

Twitter is blowing its top, some very angry people very loudly demanding apologies while other very angry people demand the denunciation of the people who are demanding apologies. Dangerously, but predictably, the split seems to have become partisan, as if to apologize were progressive, to forget conservative. The fracture widens and hardens—fanatic, schismatic, idiotic. But another way of thinking about what a culture of forced, performed remorse has wrought is not, or not only, that it has elevated wrath and loathing but that it has demeaned sorrow, grief, and consolation. No apology can cover that crime, nor mend that loss. ♦

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cory Doctorow: Denazification, truth and reconciliation, and the story of Germany’s story

Germany’s denazification was compromised and accommodated powerful, wealthy former Nazis, leading to resurgence of the far right and anti-semitism in Europe today. But it’s still better than the “least said, soonest mended” school of getting past atrocities, as practiced by the US with regard to slavery and genocide of indigenous peoples. These themes are a focus of Cory’s upcoming novel, “The Lost Cause.” pluralistic.net/2023/07/1…

1 note

·

View note

Text

What you never know won't hurt, but it's different when someone's dying, because it's not like you can say least said soonest mended, because there aint going to be no soonest or latest and you won't ever get the chance

again to tell or not tell nothing. - Last Orders, Graham Swift

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rewind, Recap: Weekly Update W/E 24/03/24

Rewind, Recap: Weekly Update W/E 24/03/24

#weeklyupdate #amreading #books #booktwitter

@doug_johnstone @richardosman @writer_suzy @EmmaLK #jamescarol @CazziF @HaylenBeck @stuartneville @jennieg_author @MichaelHWood

Well, after a lovely week off last week, it was back down to earth with a bump this. Had a lovely day trip to an Aquarium on Monday, topped off by a visit to an Ice Cream Farm Drive In. Yes – you read that right. My car developed an issue – yay. Least said, soonest taken to the garage and mended. Thankfully less painful than originally suspected, but still money I hadn’t planned to spend 🤷♀️. I…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

although, come to think about it, she possibly bites Captain Carrot, but least said soonest mended,

- I Shall Wear Midnight, Discworld #38

Haha.

Though I think it's obvious I'm struggling to get through this book. Not because it's bad but I just struggle with unfairness. When something's unfair, whether to a real person or a character, I struggle. And this book is wildly unfair to Tiffany

0 notes

Text

“They travelled 2nd class in the train and Ethel was longing to go first but thought perhaps least said soonest mended. Mr Salteena got very excited in the train about his visit. Ethel was calm but she felt excited inside. Bernard has a big house said Mr S. gazing at Ethel he is inclined to be rich.

Oh indeed said Ethel looking at some cows flashing past the window.”

(Daisy Ashford)

0 notes

Text

Least said, soonest

0 notes