#leopold von ranke

Text

Die glücklichen Zeiten der Menschheit sind die leeren Blätter im Buch der Geschichte.

The happy times of mankind are the blank pages in the book of history.

Leopold von Ranke (1795 – 1886), German historian

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Grave(s) in Berlin

Recently, I had the opportunity to visit the Sophienkirche in Berlin-Mitte, a hidden baroque treasure tucked away behind a row of grey 19th century houses whose walls still bear the scars of WW2.

Exterior of the Sophienkirche.

Those of you who have read my post on early modern ghost hunts will recall the fate of Sophie Luise zu Mecklenburg-Schwerin, third wife of Friedrich I., King in Prussia, from whom the church receives its name. At first, following her having been sent away from the Prussian court on account of an incident in which she, unaware of her surroundings due to her mental illness, had barged into her dying husband's bedroom covered in blood, the church was dubbed Spandauische Kirche according to its location in the Spandauer Vorstadt (Spandau Suburb) quarter. Curiously, Friedrich Wilhelm I., de facto stepson of Sophie Luise, had the name changed to its originally intended name Sophienkirche (Sophie's Church) a few years later.

Its tragic patron aside, the church can boast a few more celebrity connections: on 13 September 1964, Martin Luther King preached in the church on a surprise visit to East Berlin.

Interior of the Sophienkirche, viewed from the altar room.

But while I am always one for the particular charm of Prussian baroque architecture, another object of interest is located in the former churchyard.

The grave of Leopold (1795–1886) and Clara (1808-1871) von Ranke and their youngest son Albrecht (1849–1850) is easy to miss, seeing as it is located in a part of the former church grounds that has in recent history been converted into a playground for the church-owned kindergarten (am I a tad jealous that my run of the mill kindergarten did not have a playground with historic monuments in it? Absolutely.) and quite overgrown, which is a shame, considering the significance of Leopold and Clara.

Leopold von Ranke was a leading historian of the 19th century, often credited with shaping history as a scholarly discipline as we know it today and his wife Clara (Helena Clarissa, though she seems to have preferred the nickname Clara) was a leading salonnière in mid-19th century Berlin.

Having grown up academically in the shadow of Leopold, it is Clara who has captivated my interest. Helena Clarissa von Ranke, née Graves, was a member of the family I research and sometimes post about among the more light-hearted content. For those of you who do, suffice to say that Clara's great-great-grandfather Henry "Claymore" Graves and Admiral Samuel Graves's (the man around whom most of my research revolves) grandfather James John Graves were brothers.

Born in Dublin in 1808, Clara met Leopold von Ranke in Paris in July of 1843. They married the same year and moved to Berlin together, where the Rankes were renowned for their salon, visited by foreign and domestic intellectuals alike, two of the most famous of whom may have been the Brothers Grimm.

Historically, most of the historiography concerning the von Ranke family has mainly focussed on Leopold, and Leopold's work; which seems natural enough, given his importance to history as a modern academic discipline, but leaves out Clara's equally important role as her husband's equally academically-versed aide (among other things, she was competent in the use of 20 languages, half of whom she spoke fluently and sometimes did translations of Leopold's work into English) without whom a lot of his work would not have been quite so easily possible, an influential salonnière, and most importantly, a woman with literary ambitions (she was a poet, though found having her works published rather difficult), views and opinions on the politics of her time.

This is particularly vexing seeing as their granddaughter Ermentrude Bäcker-von Ranke was, according to different sources, either the first or second woman in Germany to study history and obtain a doctorate. Luckily, this changed in 2012 when Andreas Boldt's The Clarissa von Ranke Letters and the Ranke-Graves Correspondence 1843-1886 was published, allowing for a greater insight into Clara's everyday life as an integral and beloved part of the extended von Ranke family, her political opinions and friendships with influential people such as, to give only one example, Florence Nightingale.

While the Rankes were politically on a conservative spectrum in Germany, Clara maintained a keen interest in Irish politics and expressed her desire for a peaceful coexistence of Catholics and Protestants in the country.

The grave of Leopold and Clara von Ranke, viewed from a flowerbed on the other side of the fence.

I wish I could enclose a better picture of the von Ranke grave; alas, it now being situated in a kindergarten playground, there was no way to access it; a lovely lady who I believe was of the church's friend's association was however so kind as to, after checking for the keys to the gate and not finding them, give me the telephone number of the parish office, with whom a closer look at the grave might be arranged. A few pictures on Wikipedia indicate that they occasionally let people visit the premises, so I am hopeful that I might be lucky. Next time I am around, I might try and call them- stay tuned!

#graves family#leopold von ranke#clara von ranke#19th century#british history#irish history#german history#sophienkirche#berlin#history#my pics#my photography

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

TODAY IN PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY

Karl Lamprecht and Intimations of Interdisciplinarity

Sunday 25 February 2024 is the 168th anniversary of the birth of Karl Gotthard Lamprecht (25 February 1856 – 10 May 1915), who was born in Jessen in Saxony on this date in 1856.

Lamprecht pioneered many ideas that would later become commonplace in history, but which in his time were not yet welcome: cultural history, social history, interdisciplinary history, history of civilization, mentalities, psychological forces, and so on. Lamprecht’s clashes with other historians over methodology resulted in his marginalization in Germany, but his influence was felt in France, Belgium, and the US.

Quora: https://philosophyofhistory.quora.com/

Discord: https://discord.gg/r3dudQvGxD

Links: https://jnnielsen.carrd.co/

Newsletter: http://eepurl.com/dMh0_-/

Podcast: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/nick-nielsen94/episodes/Karl-Lamprecht-and-Intimations-of-Interdisciplinarity-e2g88rr

Text post: https://geopolicraticus.substack.com/p/karl-lamprecht-and-intimations-of

#philosophy of history#Karl Lamprecht#Lamprechtstreit#historicism#Leopold von Ranke#folk soul#interdisciplinarity#Youtube

0 notes

Text

40 Facts About Leopold von Ranke

Leopold von Ranke, a renowned German historian, revolutionized the field of historiography through his meticulous and empirical approach. He prioritized the use of primary sources and archival research to ensure objectivity and accuracy in his work. Ranke’s influence on subsequent generations of historians is widely recognized, and he is considered a pioneer of modern historiography. His…

View On Buzz4Fun

0 notes

Text

Pictured: (foreground) Crown Princess Elizabeth, Prince Thomas, and Queen Anne II (background) The Earl of Gloucester, and The Duke of Chelsea.

Members of the Royal Family gathered this weekend at Woodstock Palace for the recognition ceremony of His Royal Highness The Prince Edmund David Paul Francis Leopold of Wessex.

Prince Edmund is the second child of Crown Prince William and Crown Princess Elizabeth of Wessex. William additionally has a teenage through his first marriage to, Princess Margaret of Lancaster.

Edmund additionally holds the title of Serene Count of Chester as a paternal member of the House of Synklar, thanks to his grandfather The Earl of Gloucester.

The recognition ceremony is traditionally done a few months after the birth of a new member of the Royal Family. The ceremony dates back to medieval times when the sovereign would publicly recognize potential heirs to the throne.

Each new royal is formally presented by either his/her parents or "sponsors" to the Sovereign and rest of the court and blessed by the Bishop of Winchester. It is during the ceremony that the official title and styles of the child are made public.

Prince Edmund holds the rank and titular privileges as if he was child of the Sovereign. Holding the style of "His Royal Highness" along with the title of "The Prince" and territorial designation "of Wessex" giving all children of the Crown Prince the rank of "son of the Sovereign".

Like the ceremony of his older brothers, Prince Edmund's ceremony took place at Beaumont Chapel, the second most senior Chapel Royal.

Pictured: Crown Princess Elizabeth holding Prince Thomas and Crown Prince William holding Prince Edmund.

Since the recognition ceremony of his older cousins, the ceremony has become less formal at the behest of the Queen's son, Crown Prince William. In attempts to modernize, neither court or formal dress are no longer required, and the access the press once had has greatly diminished. The ceremony has since become a private family affair with only select images released by the royals following the ceremony.

Queen Anne II pictured with her youngest granddaughter Princess Maud of Chelsea and oldest grandson, and second in line, Prince Richard of Wessex

The ceremony marks also the Queen's first official appearance in public, since the funeral of her nephew Andreas von Bedford. The Palace reports that The Queen will remain in the capital until the national Fall Day of Thanks celebrations later this month and once again retreat to Fogmorre Castle after.

Affectionately called Leo by family, Prince Edmund is the youngest of the Queen's and Earl of Gloucester's six grandchildren, yet fourth in the line of succession following his father and two older brothers.

HRH Crown Prince William of Wessex, The Duke of Dorset,

HRH The Prince Richard of Wessex

HRH The Prince Thomas of Wessex

HRH The Prince Edmund of Wessex

HRH The Prince George of Wessex, The Duke of Chelsea

HRH Prince Patrick of Chelsea

HRH Caroline, The Princess Royal

HRH Princess Maud of Chelsea

Pictured: Prince Thomas of Wessex standing next to his mother Crown Princess Elizabeth of Wessex holding Prince Edmund.

Pictured: The Duchess of Chelsea with her eldest daughter Caroline, The Princess Royal

Pictured (left to right): Prince Richard of Wessex ; Crown Prince William of Wessex ; Prince Thomas of Wessex ; Crown Princess Elizabeth of Wessex ; Prince Edmund of Wessex

Pictured Standing (left to right): Prince Richard of Wessex ; Princess Albie, The Duchess of Chelsea ; Prince George, The Duke of Chelsea

Pictured Sitting (left to right): Queen Anne II of Wessex ; Crown Prince William of Wessex holding Prince Thomas of Wessex ; Crown Princess Elizabeth of Wessex holding Prince Edmund of Wessex ; Prince Christian, The Earl of Gloucester

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sometimes I feel like we are all reliving the 1930s, hurtling uncontrollably toward the 1940s and to WWIII. I don't think I'm overreacting when I see what's happening in the US and Italy, to say nothing of Russian aggression in Ukraine. As a historian, can you give me any hope, any examples where events of that era could have taken a different turn and where current times could turn out differently? Sorry to dump my angst on you.

Welp. I've been thinking about this ask for a bit, and I'll try to see if I can say anything that makes sense and is both realistic and hopeful. So here goes.

First off, history is not "fixed." It's easy to look back and say "oh, it could only have ever gone that way," but that's not true. So yes, there are literally countless examples, even in the 1920s/30s period between the world wars, and in the wars themselves, where things could have gone differently. People could have made different choices or acted in different ways, things could have broken different ways, luck could have been bad instead of good, good instead of bad -- etc etc. It's just life, and it happened the way life does: messily, chaotically, accidentally, unpredictably, until it was over and eventually people started looking back at it and studying it to see what that was. But it wasn't predetermined to happen that way, and nothing is predetermined or utterly destined to happen now. Yes, there are a lot of unsettling historical parallels -- war, plague, economic unrest, social inequality, etc etc -- that really makes you wonder if all of human history is just repeating our same mistakes in 100-year cycles. I struggle with this feeling myself, especially since as a historian, I DO know so much about what has gone on and failed to work before, and it astonishes me, not in a good way, that it's still happening now.

That said: people are so used to thinking of the study of history as Finding Out What Happened In the Past, and believing that there is only one singular narrative of what "did" happen, which can be uncovered and confirmed by objective theory and universally agreed truth. This was a historiographic theory popularized by Leopold von Ranke, a 19th-century German historian, who was trying to make the writing of history more scientific and systematic and following the essential rules of natural sciences (as the Germans were doing with a lot of academic disciplines in the 19th century). This had its merits in making the practice of history more rigorous and well-researched, but it also completely discounts the fact that all of human experience, experienced by all humans everywhere, cannot POSSIBLY be objective, or agreed on a single perspective, or represented everywhere. History happened to everyone everywhere, in all times and places, even if it wasn't the things that a certain person felt like writing down for posterity. One of my favorite anecdotes is that of a monk keeping a regional chronicle of events -- I can't remember where, in France or possibly Germany in the early 11th century or thereabouts. Next to a famous date, where an emperor died or a pope was overthrown or something of the sort (apologies again that it's early and I can't remember that either), he wrote essentially, "Nothing much happened this year. My brother who was abbot died."

Anyway, that really just sums it up for me. This monk was living in the middle of major events that would interest later historians, but he didn't know that or see that at the time, and his interest in chronicling this year was to write that his brother, who was an abbot, died. He was experiencing history by living his life and commenting on the places he lived and the people who he knew. That is because history is the monk's brother dying, as much as the emperor being overthrown; it happened in these small personal moments, as well as these huge political things. We see things and patterns in hindsight that look much clearer and put together than they actually were, but it's just the collective sum of human experience, good and bad alike.

As I have always said, people are people, in all times and places, and that means there's always hope, and there's always love, and it's usually right. Let me leave you with an absolutely heart-shredding passage from John Clyn, a fourteenth-century Irish monk and chronicler who was writing in 1349, just as the Black Death was sweeping over his monastery and leaving him as the only survivor. Alone and probably already ill with plague himself, Clyn wrote:

"So that notable deeds should not perish with time, and be lost from the memory of future generations, I, seeing these many ills, and that the whole world encompassed by evil, waiting among the dead for death to come, have committed to writing what I have truly heard and examined; and so that the writing does not perish with the writer, or the work fail with the workman, I leave parchment for continuing the work, in case anyone should still be alive in the future and any son of Adam can escape this pestilence and continue the work thus begun."

And just. My God. Even as he is "waiting among the dead for death to come," Clyn the historian finishes his work. He has committed to writing down what happened for future generations, because he still believed that there would be one. He saw the whole world "encompassed by evil," but he left parchment for someone else to write more, because if anyone should be alive in the future and anyone escaped the plague, they would want to continue the work. Of living, and writing, and doing history, and trying again. And you know what? He was right. Sons of Adam (and daughters of Eve, and children of God) did escape the pestilence. Not everybody died. Society was changed and rebuilt and life went on. The work did not fail with the workman. The future came. And the future will come again, even in the darkest and most terrible of hours.

Hugs.

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marlene Dietrich - The Queer Icon

Marie Magdalene "Marlene" Dietrich (born in Berlin, Germany on 27 December 1901) was a German-born actress who often blurred the feminine and masculine, making her "The Queer Icon."

Dietrich's earliest appearances were as a chorus girl in 1922. Making film history, she was cast in Germany’s first talkie The Blue Angel (1930) by director Josef von Sternberg. With the success of the movie, von Sternberg took her to Hollywood under contract to Paramount Pictures. She soon had hits like Morocco (1930) and Shanghai Express (1932).

When war broke, she set up a fund to help Jews and dissidents and toured extensively for the allied effort. After the war, she limited her cinematic life.

In 1953, Dietrich appeared live at Sahara Hotel in Las Vegas. This was so successful that she also appeared at Café de Paris in London and Broadway.

She continued to tour as a marquee performer until 1975, when she fell onstage. She spent her final years mostly bedridden, passing away at 90 in her Paris flat from kidney failure.

Legacy:

Nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress for Morocco (1930) and a Golden Globe Best Actress for Witness for the Prosecution (1958)

Received a Special David at the David di Donatello Awards for Judgment at Nuremberg (1961)

Given a Special Tony Award in 1968

Received German Film Awards Honorary Award in 1980

Is the namesake for asteroid 1010 Marlene in 1923

Inspired the Marlene pants in 1932

Has a Mercedes-Benz model, the 500K Marlene, named after her in 1936

Received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1947, the Commander of the Legion of Honour in 1950 and Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters in 1983 from France, the Order of Leopold in 1965 from Belgium, and Medal of Valor of the State of Israel in 1965

Published an autobiography Nehmt nur mein Leben in 1979

Granted the Council of Fashion Designers of America Lifetime Achievement Award in 1986

Honored with a plaque at her birth site in 1992 and became an honorary Berlin citizen in 2002

Has a permanent exhibit at Deutsche Kinemathek, the Marlene Dietrich Collection Berlin, since 1993

Ranked #60 in Empire's 100 Sexiest Stars in Film History in 1995

Honored with street names: the Marlene-Dietrich-Straße in Munich, Dusseldorf, Weimar, Ingolstadt, and Neu-Ulm, the Marlene-Dietrich-Allee in Potsdam, the Marlene-Dietrich-Platz in Berlin in 1997, and Place Marlène-Dietrich in Paris in 2002

Commemorated by Deutsche Post with a stamp in 1997

Listed 43rd in Entertainment Weekly's 100 Greatest Movie Stars of All Time in 1998

Depicted in a musical, Marlene on the West End in 1997 and Broadway in 1999, and a biopic, Marlene (2000)

Named 9th-greatest female star of classic Hollywood cinema in 1999 by the American Film Institute

Inducted in the Online Film and Television Association Hall of Fame in 2003

Honored by Montblanc with a fountain pen in 2007 and by Swarovski with a dress in 2017

Awarded a star in Berlin's Boulevard der Stars in 2010

Honored with a Google Doodle on her 116th birthday in 2017

Honored as Turner Classic Movies Star of the Month for May 2018

Featured in songs, including Suzanne Vega's "Marlene on the Wall" (1985), Peter Murphy's "Marlene Dietrich's Favourite Poem" (1989), Black Midi's "Marlene Dietrich" (2021)

Depicted onstage in Marlène Dietrich, The Blue Angel's White Nights in 2017 at Théâtre Trévise and Marlene in Hollywood in 2023 at Theater Lindenhof

Featured in exhibits, such as "Marlene Dietrich, Creation of a Myth" at Palais Galliera in 2003, "Marlene Dietrich: Dressed for the Image" at National Portrait Gallery in 2017, "Play the Part: Marlene Dietrich" at International Center of Photography in 2023

Is a muse for designers, including Vivienne Westwood, Thierry Mugler, Jason Wu, Max Mara, David Koma, and Dior

Has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6400 Hollywood Boulevard for motion picture

#Marlene Dietrich#Blonde Venue#Blue Angel#Silent Films#Silent Movies#Silent Era#Silent Film Stars#Golden Age of Hollywood#Classic Hollywood#Film Classics#Classic Films#Old Hollywood#Vintage Hollywood#Hollywood#Movie Star#Hollywood Walk of Fame#Walk of Fame#Movie Legends#Actress#hollywood actresses#hollywood icons#hollywood legend#movie stars#1900s

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

So what was the historical theory of objectivism?

jasminewave asked:

So, what *is* the difference between the small-o objectivists and the Randian Objectivists?

It's more accurate to call them the "Objectivity" School of history, and this one goes all the way back to the very earliest days of history as an academic discipline in the mid 19th century. (This is something we covered in my Intro Theory course in grad school, and I remember it well.) At this time, American historians were really struggling with how to differentiate themselves from the plethora of amateur historians (a problem the disciplne still has), and like a lot of educated people in the Anglo-American sphere they turned to the Germans, because German higher education was the absolute cutting edge in the 19th century.

Specifically, they turned to Leopold von Ranke:

One of the OGs (he started university in 1814, not long after the universities had re-opened after Napoleon had closed them, and his first book was published in 1824), Von Ranke can arguably be called the father of academic history: the dude introduced source-based methods, archival research, seminars, and close reading of texts to the discipline. He's associated with a particular phrase that decribed how he thought history should be approached: "wie es eigentlich gewesen ist." This can translate to either history "as it actually happened" or history "as it happened in its essence."

In part because Von Ranke really hated Hegel (the feeling was mutual) and the whole concept of the "philosophy of history," his English-speaking acolytes used the former translation and committed themselves to a particularly austere version of empiricism in which the historian was to confine themselves to "just the facts" and refrain from any grand theories that sought to explain historical events through a teleological narrative of progress or the working out of an Idea through the dialectic. (Peter Novick argues that this was a total misunderstanding of Von Ranke's work, that Von Ranke was way more of a German Romantic than he was thought to be, and that for example Von Ranke believed that the 16th century had been set aside by God for the working-out of Lutheranism and German nationalism, which Von Ranke thought were basically the same thing.)

Combining Von Ranke's empiricism with Victorian positivism, the Objectivity School believed that (through proper academic methods) historical events could be understood objectively, as if the historian had actually been there at the time, observing with omniscient and impartial eyes. Once that had been accomplished, each historical fact could be added to the general store of knowledge like bricks being stacked into a great pyramid, until at some point in the near future the edifice would be complete, we would know the Past perfectly and completely, and the project of academic history would end.

Every generation and school of historians who followed screamed "bullshit" at the top of their lungs. Not only were historical sources always partial and incomplete, but they were also thoroughly biased so that their description of events couldn't be taken as objective fact but subjective interpretation. The same was true of historians, they argued as the brand-new field of historiography first turned the analytic eye back on the historical discipline, who all were products of their environment and who inevitably interpreted sources through the lens of their own beliefs and values. Rather than a scientific march in the direction of the pyramid of perfected knowledge, history by necessity would have to be a permanent revolution of revisionism, as each new generation and new school of historians reinterpreted the events and facts we thought we had known through new eyes and new ideas.

After a huge dust-up at the turn of the 20th century that saw more than a few younger historians banished from the universities for being godless communards, the Objectivity School faded away within the historical discipline and became merely an object of study, which I think is a fitting end.

So that's the difference between objectivism and Objectivism.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Graves

Graves, oder Ranke Graves, wie er deutlich/ deutsch wegen einer Verwandtschaft mit Leopold Ranke genannt wird, ist zwar kein Baseler Archäologie, kein Hamburger/ Florentinischer/ Jüdischer Kassierer und Bänker, kein Pierre Klossowski oder Roger Caillois. Aber wie die Baseler Archäologen Bachofen, Burkhardt, Nietzsche, Holl und Krajewski hat er zu einer Geschichte und Theorien von Geschichte und Theorie beigetragen.

Diese Figuren trennen Geschichte und Theorie unbedingt, aber nicht unbedingt groß - vor allem aber ist die Trennung Teil einer juridischen Kulturtechnik, die man Scheiden, Distanzschaffen oder Säumen nennen kann, weil sie trennt, assoziiert und austauschbar hält. Warburg gibt dem eine juridische Figur, nicht nur mit dem Begriff des Distanzschaffens (der doch recht abstrakt und für juristische Ohren nicht unbedingt vertraut klingt). Trajans Gerechtigkeit ist die Figur, die bei Warburg zwar Teil einer Geschichte ist (und insofern vorbei ist), aber auch seiner Theorie, weil diese Figur dafür einsteht, was es heißt, ein achronologisch geschichtetes Material zu betrachten. Die Figur hängt an einer Phänomenologie 'historischer' und 'theoretischer' Betrachtung. Äußert gewitzt hat Trajans Gerechtigkeit mit Medien des Rechts zu tun, die auch Tor/ Tür/Bresche/Wundmahl/ Bar/Kasse einerseits sind (in dem Fall der realen Virtualität eines Triumphbogens, der Mimesis am römische Stadttor betreibt und auf der Linie des pomerium steht, indem er sie ins Innere und Äußere von polis/polus versetzt) und Säule/ Stab/Pole sind. Triumphbogen und Säule sind die Medien, die Trajans Gerechtigkeit auf den Schirm gebracht haben,l im tragenden und übertragenen Sinne, aber nicht immer in beiden Sinnen gleichzeitig.

Graves arbeitet dem Warburg affin, an Geschichte und Theorie, die sich nicht erledigen, aber kippen, dabei übertrumpfen und unterliegen kann.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

random Randolph headcanons

Randolph von Bergliez was born Randolph Lautrec, in 1160, in the Fort Merceus. His father was a blacksmith and worked for Caspar's grandfather, who then becomes his step-father when his father dies of a wasting illness when he was just a boy.

Despite not being his son by blood, (or maybe because of it), the then Count Bergliez treated him very well. He didn't go through the infamous Bergliez training though: Count Bergliez's health was declining and he wanted to enjoy the time he had left. His only taste of real battle before he joins the Imperial Army was the military tactics books his step-father would make him read.

He grew up admiring the man, but also realized with time that his mother and Count Bergliez probably started their affair before his father died and it left a bitter taste in his mouth about loyalty. Even moreso as he realized Flèche was fathered by his step-father.

Initially, he was very excited about having an older brother in Leopold. But the man couldn't trust Randolph's mother any less and refused to even acknowledge him or Flèche after his father died. It wasn't really personal, but if Flèche's true parentage came to light, she could petition for the Count Bergliez title if something happened to him.

He has few memories of being allowed to play with Caspar and his brother as kids, one that ended with Randolph punching Caspar's older brother in the mouth after he called Flèche a bastard baby. Once informed, Leopold didn't get angry with him, but said that perhaps there was more Bergliez in him than he first thought. They weren't allowed to play together again and left Fort Merceus soon after.

He used to play cards and lost a good amount of money to it, which led to people thinking he was unreliable. It was well-deserved, he'd also ruined the engagement his step-father had arranged for him before passing, because he refused to marry for anything but love because of aforementioned issues with loyalty.

He was supposed to join the Officers' Academy but his step-father's death stopped that from happening because most of house Bergliez shunned them, and blocked the large inheritance his mother was expecting.

He joined the Imperial Army at seventeen and quickly rose through the ranks. He and Ladislava became quick friends at that time and she was the one to recommend him to Edelgard when she became head of her personal guards.

Dorothea and Randolph are good friends. They met during the early days of the war and immediately hit off due to their similar goals. She often chides him for not taking the easy way and marrying rich like she plans on doing-- he's handsome enough to pull if off, but he reminds her that she's fighting this war just like he is. She'll perform her most popular songs for his men, which really boosts their morale. She calls him 'Randy', which he absolutely loathes but only tolerates from her. Flèche thinks she's the coolest woman EVER.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summary of 1st half of The Paradigm of Catharism; of, the Historians Illusion by Mark Gregory Pegg

So not counting the introduction this is the first essay in Cathars in Question, a collection of essays between scholars debating the existence of Cathars. If you've been following me for a while or know me irl you've probably heard me reference this as 'cathargate.' I'm making it a little project to write out summaries to the essays and post them both for the sake of my own comprehension on the topic and also because a few ppl I've talked to about it have expressed interest in it. If anything in this post interests you I highly recommend reading the essays themselves, both because I'm not an expert and because Pegg's zingers are kind of funny ngl.

Pegg’s opening postulates that Catharism was exclusively an invention of “late 19th century scholars of religion and history.” It’s important to note that he isn’t claiming that Cathars were invented by medieval inquisition. He specifies that it is not “a construct of the persecuting society” (shouting out bestie R.I Moore) but rather a distinctly modern invention. Because, as Pegg understands it, Catharism is a modern invention, it makes sense that he would therefore first go into where he believes this invention originated. Pegg repeatedly calls back to this idea of a paradigm of Catharism, that is supported by two methodologies he identifies as both distinct and incompatible. In this first post we will discuss the first he identifies, that being the Intellectualist approach.

What is the Intellectualist approach, as Pegg defines it?

“It views the study of religion and heresy as an exercise in intellectual history…presumes that heresies have coherent theologies and doctrines combined and disseminated in canonical texts by heretical leaders”

Pegg says this approach was codified after 1870 via who else but the Germans doing “Religionsgeschichte”, a religious historical school that approaches the study of religion by comparing seemingly similar systems of belief. They have this idea called “world religions” or “universal religions”

WHAT ARE THE FEATURES OF A WORLD RELIGION?

elaborate clerical hierarchy

evangelical missionaries

fixed rituals

foundational sacred texts

clear distinction between secular and religious

World religions are intended to resemble Christianity, Pegg says. World religions include Hinduism, Confucianism, Buddhism, antique paganism, Gnosticism and Manichaeism.

The most important exponent of the ‘religious-historical school’ for medieval heresy was Herbert Grundmann, who wrote Religiose Bewegungen im Mittelalter (1935)

He compares the beliefs of individual heretics, wandering preachers, early mendicants and specific religious women in the 12th and 13th centuries. He argues that the religious motivations (such as adopting an apostolic life) were similar, and that there was one general religious movement before 1200 that then fractured into heterodox and orthodox movements during the papacy of Innocent III (Papacy 1198-1216) Apparently this was barely noticed until after 1960. But here in the late 19th century, we have a different problem, and it's called Objektivität.

WHAT IS OBJEKTIVITAT? (according to Pegg)

Approaching history as a science

Approaches religion as a natural process rather than a historical one, meaning you can make scientific generalizations like in taxonomy (lumper problems are forever!)

Desire to study religion objectively without POV from particular religion of historian

This method is seen as distinct from the previous attempt at objectivity, namely, ‘pure historicism’, associated with Leopold von Ranke. Pegg says another characteristic tactic of the religious historical school was to figure out the origin of a particular belief was “finding the first person to think a thought or the first text to expound a belief.’

This is my own input but. You may be thinking “yeah, to find an origin of a belief you go to the first guy who said it” HOWEVER this is under the assumption that the origin of a given belief has a textual tradition, as opposed to an oral tradition. I get the sense Pegg is worried about lumpers again. It seems ‘logical’ to go back to the beginning of a belief in order to figure out the origin, but that is under the assumption that you have indeed found the beginning to a particular tradition, as opposed to a disparate belief/tradition that just so happens to resemble what you’re researching. It also means you’re assuming the religion/belief you’re studying is part of an intellectual history.

What’s next relevant; You’ve got this idea that Cathars are an eastern import. Grundmann argues that the Cathars shared some similarities with western apostolic groups when they initially entered Europe, but ultimately remained outsiders, even if their philosophy sometimes supported the ideas of 12th century heretics, even if it was sometimes shaped by Latin Christianity. According to Pegg this desire to find eastern influences within western religious trends is symptomatic of a particularly German form of Orientalism (Orientalistik) that is a hallmark of Religionsgeschichte, and he claims this Orientalism has been both ignored and carried over by “adherents of the paradigm” (meaning scholars who believe in Cathars as Christian dualists with eastern influences, the conventional narrative.)

Grundmann also says that Waldensianism was a lay Catholic reaction to Catharism, and that Waldensians were provoked more by Cathar heresiarchs than they were by concerns about the Catholic hierarchy. Pegg includes Peter Biller as an example of a contemporary scholar who shares this notion; “Peter Biller, for example, follows Grundmann in arguing that Catharism as an established eastern philosophy…must have existed before Waldensianism, otherwise the latter could not have dome into existence as a coherent western religious movement.” Pegg concludes this section, stating that for both Grundmann and any scholars who believe in the existence of the Cathar heresy, Catharism functions as a ‘world religion.’ Incidentally we’re going to be hearing from Peter Biller himself later in this book. I wonder if he will have any response to the religionsgeschichte allegations.

#next up is Pegg's thoughts on social history as applied to Cathars#and then we leave historiography and get into his analysis on the sources themselves which is exciting#and then John Arnold is on deck#cathargate

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nachahmen ist schon eine Art von Knechtschaft; eigene Ausbildung und Entwicklung, das ist Leben und Freiheit.

Imitation is already a kind of servitude; Independent training and development, that is life and freedom.

Leopold von Ranke (1795 – 1886), German historian, historiographer of the Prussian state, university teacher, and Royal Prussian privy councillor

21 notes

·

View notes

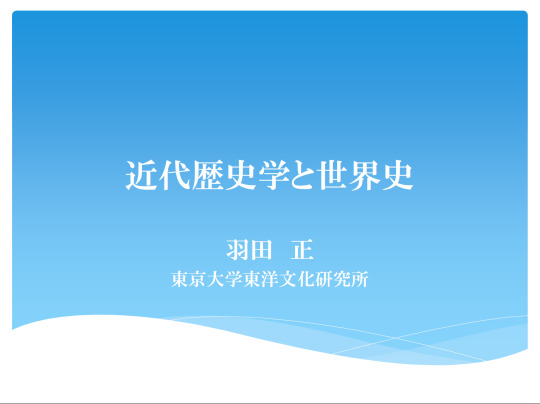

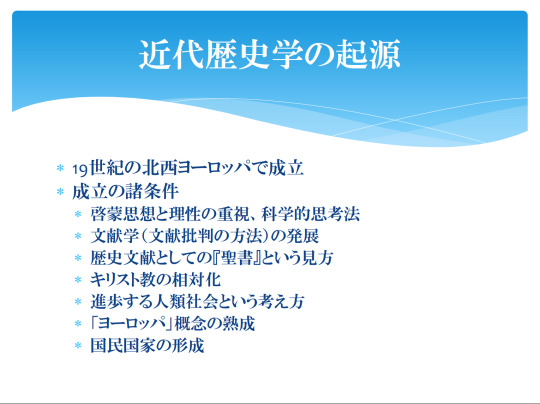

Photo

(近代歴史学と世界史 Modern History and World History | UTokyo OCW (OpenCourseWare)から)

東京大学の正規講義の講義資料・映像を無償で公開しています

2012年度開講

「世界史」の世界史(学術俯瞰講義)

世界史という名前の科目は、日本や中国など東アジア諸国に特徴的にみられ、欧米や中東などでは単に「歴史」と呼ばれる科目しかありません。また、大筋は同じだとしても、国によって、教科書の内容は微妙に異なっています。世界史は、決して一つではないのです。なぜでしょう。 世界史の理解は、自分たちの生きる世界をどう認識するかということ、すなわち世界観と深くかかわっているからです。

この講義では、現代と過去における多様な世界観と世界史理解を紹介し、皆さんが高校で学んだ世界史がどのようにして成立したのかを解説します。これは、世界史を生み出す歴史学という学問の歴史を俯瞰してみせる連続講義です。また、この機会に、現代の私たちにふさわしい世界史理解はどのようなものかを一緒に考えてみましょう。

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

レオポルト・フォン・ランケ - Wikipedia

(Leopold von Ranke, 1795年12月21日[1] - 1886年5月23日)

19世紀ドイツの指導的歴史家[2]。

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

歴史認識の時空 | 佐藤 正幸 |本 | 通販 | Amazon

世界史における時間 (世界史リブレット) | 佐藤 正幸 |本 | 通販 | Amazon

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

新しい世界史へ - 岩波書店

グローバル化が進み,ますます一体となりつつある現代世界.従来のヨーロッパを中心とした世界史像は,もはや刷新されるべき時を迎えている.いまこの時代にふさわしい歴史叙述とはいかなるものか.歴史認識のあり方,語り方を問い直し,「世界はひとつ」をメッセージに,地球市民のための世界史を構想する.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flourishing with Herodotus

"FLOURISHING WITH HERODOTUS

by royalhistsoc | Jul 13, 2023 | General, Guest Posts, History and Human Flourishing | 0 comments

In this second post of the ‘History and Human Flourishing’ series, Suzanne Marchand explores the contemporary value and relevance of Herodotus in historical teaching and methodology. Though often overlooked in favour of a ‘scientific’ approach advocated by nineteenth-century acolytes of Thucydides, Herodotus and his Histories remain a rich — and much needed — guide to history as the story and study of human behaviours. In this post, Suzanne considers Herodotus’ appeal and lessons for historians today.

This post is the second contribution to the Society’s 3-part ‘History & Human Flourishing’ blog series. The first, by Darrin M. McMahon, explores the often-neglected study of the history of human happiness.

There is, in my view, too much Thucydides in our histories and perhaps in our hearts today. This is partly the fault of the nineteenth century, when he became exemplary of the ‘right’ kind of historian: cynical, disciplined, grimly determined not to waste time on trifling matters. Power, for him — in a way oddly reminiscent of the also still-pervasive work of Michel Foucault — is what drives history and defines all human interactions, regardless of what anyone might say. So much have we accustomed ourselves to this cynical view that even the cultural historians among us struggle to wrest ourselves from its grip.

This is why it might be healthy to recall that Thucydides devised his historical principles to demonstrate his superiority to an already famous predecessor — one who has always, also, had his advocates, even if his reputation suffered a tremendous blow in the age of Leopold von Ranke. Pace the military strategists and the philosophers of international relations, we historians do not have to be eternal Thucydideans. Indeed, in doing so we might find new means of flourishing by embracing some of the richer and weirder methods of writing — and especially of teaching — history and of conceiving human nature that Thucydides renounced.

Herodotus gave us so much broader a picture of the calculated and crazy things we do, how rulers succeed and screw up, how cruel and clever we can be.

The spurned predecessor to whom I refer to is, of course, Herodotus, whose Histories relate, in shaggy dog fashion, the cosmopolitan backstory and then the unfolding of the Persian Wars.

It would wrong to insinuate, as Thucydides does in the famous passage at 1.122, that Herodotus wrote merely for entertainment, and did not care about truth, or to assert, as would Plutarch five centuries later, that Herodotus maliciously skewed his story. There are entertaining and improbable stories in The Histories, such as the rescuing of the poet Arion by a sympathetic dolphin, and plausible but probably exaggerated ones, like the water management projects of Assyrian Queen Nitocris (1.185). But even more, there is with Herodotus a rich variety of life, women as well as men (by one count, only six are mentioned in Thucydides, to 370+ in The Histories). To these we may add animals, gods, rivers, kings, and others, motivated not just by self-interest or the yearning for power, but by dreams, vanity, misunderstanding, passion, stupidity, pride, or simply unknown forces the historian cannot fathom.

In Book 6 (6.129-130), Herodotus tells the story of Hippokleides, set to make an advantageous marriage, who drinks too much at his engagement banquet, resulting in a bout of ribald dancing during which, it is suggested, he reveals his privates. When his prospective father-in-law tells him that he has danced away his good fortune (the original ‘balls up’), the merry-maker’s response — still used as an adage in modern Greek — is ‘Hippokleides doesn’t care!’ Don’t we all recognize a Hippokleides in our lives, perhaps (at least occasionally) in ourselves?

Image 1: Claude Vignon, “Croesus showing Solon his Treasure” (1630s) Wikimedia commons

Cicero termed Herodotus the ‘father of history,’ but in the same breath bracketed him with Theopompus, known for his long-winded digressions and his innumerabilies fabulae. What Cicero didn’t note was that Herodotus’ approach had a purpose: to convey a great deal of information and insight into human behaviour, at home, and abroad. Over the centuries, thousands of Herodotean fact-checkers have attempted to verify his information, sometimes finding him mistaken, but often recognising ways in which he was interestingly (if not perfectly accurately) right — about the Egyptian labyrinth, for example, or Persian horse lore.

But an even better reason for teaching Herodotus, or better teaching like Herodotus rather than, unrelentingly, like Thucydides, is that Herodotus gave us so much broader a picture of the calculated and crazy things we do; how rulers succeed and screw up, how cruel and clever we can be. Of course, his was also a very Greek way of seeing the world, and Herodotus’ stories about the despots of the East must be read with this in mind. But as he says in the very first line of his history, his intent throughout is to record for posterity the great deeds of the Greeks and the Persians, as well as to explain why they fought. I believe that Herodutus meant it, as he meant to show, too, that Egypt was full of wonderous things; that Scythia was home to brave if barbaric tribes; that some Greeks were cowards and tyrants; and others, at least some of the time, ingenious and courageous.

What if we accepted a bit more of the Herodotean worldview, and his approach to engaging with the past?

Herodotus certainly did care about human happiness. One of his most beloved tales, that of Solon and Croesus (1.29-33), goes right to the heart of the issue. As Herodotus relates, during travels he initiated to avoid having to repeal laws he imposed in Athens, Solon visited the extraordinarily wealthy king of the Medes. During his visit, the proud king shows Solon his riches, whereupon Solon launches into a story, the moral of which is that as fortune is ever changeable, one should not count oneself happy until one rests on one’s deathbed, surrounded by adoring family and friends.

The story acts as a prophecy, as Croesus will soon fall prey to an epic form of pride inciting a fall. Croesus will recall Solon’s admonition as he is about to be burnt on a pyre after the conquest of his kingdom (1.86). This is no mundane proverb, and it teaches an important, perhaps better, lesson than most Disney movies: one can and should try to live a good, honourable life. But one might fail, and not necessarily because of a ‘fatal flaw’ — fortune can simply deal a bad hand. Isn’t this a sensible way for us to conceive of our fellow humans and their flaws? Sometimes the flaws get you, sometimes you simply have bad luck (which might be structurally conditioned). If the seventeenth century read the story as a warning against enjoying worldly riches (see image 1 above), we might read it as an admonition not to judge people by their fates, and to take seriously the view that there, but for the grace of God, or fortune, go I.

Image 2: Karl Gottfried von Lück, ‘Tomyris with the Head of Cyrus’, Frankenthal Porcelain Manufactory, c. 1773; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Public domain.

Most especially, I would like to advocate for more Herodotean teaching in the classroom … Environmental history has spurred us to put nature and animals in the picture, as did Herodotus; he would approve of discussing commerce and foodways.

What if we accepted a bit more of the Herodotean worldview, and his approach to engaging with the past? I don’t think scholarly history can do this entirely, but it would be a relief to escape the unrelenting cynicism of the Thucydidean-Foucauldians. But most especially, I would like to advocate for more Herodotean teaching in the classroom. College students have endured all too much ‘high’ political and military history in high school, and find more engaging lectures on ‘everyday life,’ whether in discussions of colonial Salem, or Roman Britain, or Nazi Germany. Environmental history has spurred us to put nature and animals in the picture, as did Herodotus; he would approve of discussing commerce and foodways.

Why not indulge in a few good stories, such as that of Queen Tomyris, who avenged her army’s slaughter at the hands of Cyrus by having him decapitated and his head dipped in a bag of blood? Herodotus told this story (1.212), and it was so memorable that even when his Greek text was lost to the West, medieval and early modern writers (including Shakespeare) knew and repurposed it; eighteenth-century porcelain makers, too, recreated it (see image 2). The story may well be apocryphal, but these too can occasion good teaching moments. Let’s see what we can do to make college history more Herodotean. Even if it won’t save us from the disdain of an increasingly presentist culture, at least, like Hippokleides, we might enjoy a last binge.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Suzanne Marchand is Boyd Professor of European Intellectual History at Louisiana State University. Her current research projects include a history of Herodotus’ readers from 1700 to the present, tentatively titled Herodotus and the Instabilities of Western Civilization. Her wide-ranging research interests include classical studies, art history, anthropology, history, and theology in modern Europe, as well as in the history of porcelain and related topics in the history of material culture and consumption in Central Europe.

Suzanne’s publications include the article ‘Herodotus and the Fate of Universal History in Nineteenth-Century Germany’, Journal of Modern History (forthcoming, 2023) and the monographs Porcelain. A History from the Heart of Europe (Princeton UP, 2020) and German Orientalism in the Age of Empire: Race, Religion, and Scholarship (Cambridge UP, 2009).

Her essay, ‘Flourishing with Herodotus’ appeared in Darrin McMahon’s edited collection, History & Human Flourishing (OUP, 2023)."

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

For historians, footnotes “amount to a staccato, partial intellectual biography.” The “historian’s footnotes offer a narrative about the historian who wrote the text.” They tell us what they consulted and how they interpreted those sources. Such historians are, after all, asking us to trust them that they did the work, which is typical of a lot of the reading. “Footnotes give us reason to believe that their authors have done their best to find out the truth about past events and distant countries.” They are, in short, the historian’s credentials, their bona fides (Latin for “in good faith”).

0 notes