#marthe robert

Text

Some Brothers Grimm fairytales facts (1)

So, my mother has this old copy of the Brothers Grimm fairytales published in the 70s - a selection of Grimm fairytales translated by Marthe Robert. If you do not know Marthe Robert, she is one of the famous French literary critics of the 20th century, known for her many translations of German works (she is recognized as one of the experts of Kafka in France), as well for her numerous works about the psychanalitic interpretation of literature.

And this edition also has a preface where she points out some things that are quite interesting... Now, I need to precise, I wouldn’t advise you to take everything in this preface. As I said, Marthe Robert had a psychanalysis-approach to fairytales (which was the one popularized and widespread by Bruno Bettelheim’s work). And while I, for myself, enjoy those interpretations (Bruno Bettelheim was actually how I got to first discover the depths and complexity of the fairytales), I also came to realize, by studying fairytales, that they are not the best to ACTUALLY understand fairytales. Mostly because psychanalytic readings and interpretations of fairytales are strongly intertwined with the folklorist reading of fairytales, and... as I keep pointing out, the folklorist point of view has been discovered to be quite flawed in several aspects. It doesn’t remove the beauty or poetry of these readings and interpretations, which provide a new richness and new meanings to the tales... But to be taken with a grain of salt.

However we are here talking about the Grimm fairytales, which due to being folktales in nature (though slightly edited to fit an ideology), are much more fitted for folklorist and psychanalytic readings. And as a translator of the works of Grimm, Robert brings some interestng points... So let’s see them.

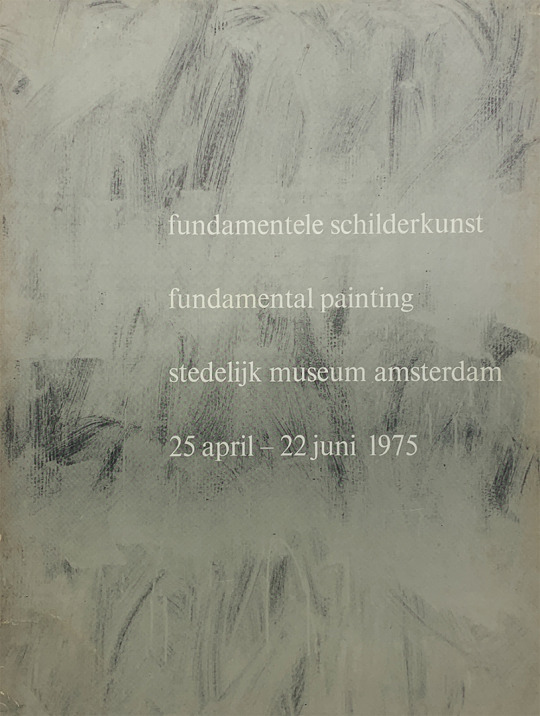

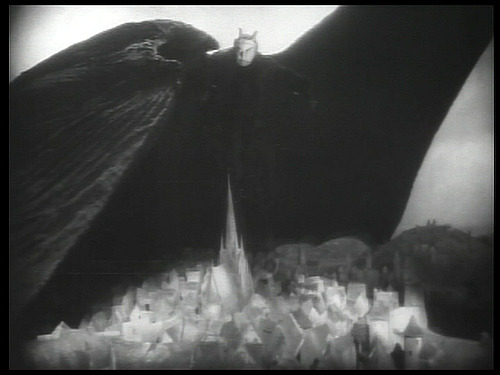

(This is the painting on the cover of the book, so I’ll add it for a bit of illustration)

1) One thing that is very true, and that we should never forget - the Grimms might be criticized any way you like, but what can’t be robbed for them, is the fact that thanks to their hard-work and dedication they managed to survive and restore an entire oral folklore that was slowly dying out and about to be lost forever. Without the Brothers, we would have never have so many tales that are classics of our culture today.

2) A good illustration of the literary VS folklorist point of view. Marthe Robert, having written this preface in the 70s, was heavily influenced by the folklorist studies, and this shows in the text. Most notably, already at the beginning, we see the presence of a HUGE misconception spread by the folklorists. This misconception is that “While Perrault made the fairytales popular among scholars and people of taste, nobody until the Brothers Grimm thought of these stories as something more than just the charming, naive and simple products of a popular imagination, only fully enjoyable by old women and children”. This is a HUGE misconception. The thing is that the whole “These stories are just humble folk-tales told by old nurses, by the fireside during evenings are peasant homes” or “These tales were written and told with a child-like mind, and are just little nonsense for your entertainment” was present in the literary texts of fairytales we had (such as Perrault’s tales)... But it was a narrative and publishing strategy. Fairytales, as a literary genre, was a whole aesthetic, and Perrault, like others, were trying to imitate the folktales they took inspiration from - so of course they were going to add elements defending the “childishness” or “simple-mindedness” of their tales. It was also an excellent way to avoid censorship (which was strong, back in the days) and to deal with the very harsh world of critics and literary feuds at the time (you don’t know how strong it was back in 17th century France, worst than Internet dramas these days). By pretending that these tales were just “simple folktales of foolish old women and naive children”, the authors could avoid a lot of things that would have raised the ire of the censorship. But these things, half-hidden, were clearly spot-on by those in the known...

Because, I can’t tell it enough, while the pre-Grimm fairytales, especially the French fairytales, Perrault and others, were PRESENTED as simple folktales, they were not at all simple folktales written hastily. They were literary works, carefully planned, with several drafts. They were stories written by adults for adults, part of games, entertainments, discussions and debates in intellectual circles. They were filled with jokes, and wordplays, and innuendos, and dark undertones, and there were layers of hidden meanings and symbolism everywhere. Because it was part of the “game” of the fairytales back then. They weren’t just about “Who can invent the wackiest tale?”. The pleasure was also to try to understand what the author hid and wrapped under the costume of a “poor, naive folktale”. The way Little Red Riding Hood was an obvious metaphor for ill-intentioned seducers, the way that Diamonds and Toads is in truth a praise of flattery and politeness (which were key elements when living at the royal court), the way that Puss in Boots was an humoristic critique of the ascension to power of some and of the system of inheritance and rewards at the time, in Louis XIV′s France...

All that being said, take the next sentence of Marthe Robert and you’ll understand what is wrong with it: “While people had fun reading them, or sometimes writing them, nobody actually wondered why they came to be, and their meaning was clear enough to be resumed in a short morality that, while making these tales useful, also justified their weirdness”. It is true that the Moralities were here as a “safety measure”, to justify the nonsense and bizareness of these tales (in late 17th century France, nonsense was considered garbage, and every literary work needed to have a reason to be and a usefulness to it, you didn’t actually just wrote something because you felt like it - if you did that, you were not perceived as a true author, or even as a writer, but just a scribbler). But the mistake here is to believe that these “Moralities” hold the entire, simplified meaning of the tales. Far, far from it, as French fairytales were purposefully designed to have a game of meaning and complex senses: the fun was all about decyphering them.

3) Marthe Rober then proceeds to describe the thought-process that led to the rise of the “folklorist reading” of fairytales, and which was the point of view that dominated ever since the Grimms’ work became popular. And this thought process is: Let’s collect folktales and stories from all around the world, from various countries and continents. Then, let’s compare them, in how similar they are. Now, we see that they have a common structure, common narratives, with elements that are sometimes described and placed in identical fashons - except for a few exceptions. But beyond them, these striking similarities and identicalities prove a continuity of themes beyond countries and cultures. How to explain this? It can only be explained by a common source, a common origin: all the tales have a common ancestor.

[Note by me: This is the folklorist point of view. But the literary point of view that is now contradicting this one, if you are ever interested, is that maybe the “story-ancestor of all the tales” is a myth that never truly existed ; maybe these similarities and continuities are due to stories feeding of each other, and blooming and spreading from each other, due to an intertextuality and cross-cultural influence rather than a so-called “common ancestor” that had “children” everywhere - and unlike the folklorist viewpoint, which casts aside the unusual and pattern-breaking variations as “exceptions to the rules” or “one time weirdness”, the literary point of view considers that, on the contrary, they should be considered with as much importance as the stories that deviate from the “main mold”.]

Marthe Robert even mentions the theory held by the Grimms themselves (though she doesn’t seem to fully adhere to it?), that the common ancestor of these stories was... Aryan stories. For them, the “aryan tribes” were the ancestors of the Hindus, the Persians, the Greek, the Romans, and the other people of Europe, and thus the common ancestor of all those folktales and fairytales were none other than the “ancient Aryan tales”... [Did I mention the Nazis had a huge liking of the Brothers Grimm and reinterpreted their books and works in perverse ways? Well, if I hadn’t before, now you’re warned.]

4) Moving on, Marthe Rober then explains that, once the origin of the tales are explained in this way, all that is left is to interpret these tales and get their meaning. And she offers us something she calls the “natural reading” of these tales. A type of interpretation that was REALLY popular for a time, that is quite poetic in itself I’ll admit, but that also gets really wacky and wonky sometimes, when pushed to its extreme limits. This “natural reading” is simply the interpretation of fairytales as descriptions and allegories of natural events and phenomenon. The first example she gives, and which is the one that is invoked a lot even today, and perhaps the most “solid” of them all, is Sleeping Beauty: the asleep princess represents spring or summer, her hundred-years sleep is winter, and the young prince that wakes her up must be the sun “waking up” nature in spring (Marthe Robert notes that this interpretation still has leftovers in the tale of Perrault, where the princess two children are “Day” and “Dawn”). Okay, so far so good... But then Robert adds two more “natural readings” which, for me, are completely off, and just stretching the concept heavily. There is the “natural reading” of Cinderella, where the titular heroine is the “hidden light”, some sort of solar figure whose light and shine is clouded or obscured by the ashes covering her - and who gets to only shine bright again by marrying her prince. Quite a stretch of a reading, but at least I get where it’s coming from. And then... Then there’s the worst offender. The natural reading of “Donkey Skin/A Hundred-Furs”. The reading where “the girl fleeing her father’s incestuous desires by hidng in a beast skin” is actually “dawn, hunted by the sun, of which she fears the burn”... Poetic, but really wacky. And not solid enough to hold what Marthe Robert adds - that “with this reading, all these tales come to have roughly the same meaning”, aka a description of a battle to restore light.

5) Hopefully the “natural reading” paragraph was purposefully presented in a not-so-good light by Marthe Robert, since she immediately adds that this subject has been debated, discussed and debunked for a long time now - and is just a “historical fact”. She notably invokes how these theories, be it the “aryan theory” of the Grimm or the “natural readings”, only work for European folktales, and completely break down when it comes to fairytales from other continents. Comparing them to the European tales completely debunks the idea that all these stories have a supposedly common ancestor whose influence spans worldwide. (That’s something I enjoy with psychoanalysis interpretations of fairytales, while they completely miss the literary aspect, they are also detached enough from the folklorist one to see its most obvious flaws. Of course, then they go sometimes into far-fetched places themselves, but nothing is perfect). In Robert’s own words, the theory of the brothers Grimm was “far too narrow and yet far too large”, but it had the praise to actually make people realize and understand that the fairytales were actually just as important and meaningful as the myths of old.

6) Marthe Robert then goes on to describe how, despite social and religious changes, the continuing fairytales keep carrying the same meanings behind the allegories, and the same “human experience” hidden by its images - she notably points out that, despite being developed in Christian cultures, fairytales still hold on dearly to many elements of paganism, through depictions of various rites, practices and customs - for her, these are more than just memories carried on by the tales, but rather instructions making the fairytales didactic, turning them into manuals and teachers.

7) So, while she rejects the Grimm-brought idea that the “true meaning” of all fairytales is a mythological description of the cycles of nature and weather or astral phenomenon, she, as a psychanalyst-influenced literary critic, still believes in a “general meaning” behind fairytales, a “recurring sense”. And for her, the fairytales are all about a passage, a transition. A needed passages, a difficult transition, with a thousand obstacles on the way, preceeded by seemingly unbeatable trials, but that always ends up happily concluded. “Under all of the most incomprehensible fantasies, a real fact keeps appearing: the necessity for an individual to go from one state to another, to transition from one age to another, and to shape themselves through painful metamorphosis, that will only end when they reach a true maturity”. For her, in the “archaic” culture that the fairytale preserved, the rite of age-passage, be it from children to teenager, or from a teen to an adult, is a perilous transition, a trial that can only be won by an initiation beforehand. So this is why the child or the young man of the fairytale, finds suddely himself lost in a deep forest with no way out, and there meets a wise person, often older than him, whose advice will help him find his way back. [Note: You can see here that she is very influenced by the Märchen, of which she is writing a preface of and that she just translated. But this is a common thing with psychanalist readings of fairytales, they usually focused exclusively on the Grimms and Perrault, with a tiny bit of Basile on the aside, but that’s it.]

8) Another typical “folkorist slander” of French fairytales: “If the French tradition weakened the initiatic aspect of the fairytale to replace it by a barely-disguised eroticism and a conformist morality, the German fairytale, less “civilized”, keeps all of its strength”. Urg. “A barely-disguised eroticism”, I guess when you want to denounce the dangers the sexual abusers, you need to add some sexual elements lady! And have you seen Basile’s story? They are sex comedies, and scatological too, true medieval tales of Reynard! As for the “conformist moralities”, I talked about it before - the Moralities of Perrault (and she is clearly referring Perrault because he was the only one to put Moralities in all of his fairytales) only looked “conformist”, but the minute you pay attention to them, you realize they are in truth subversive moralities.

9) Now, while she uses this element to exemplify her slander above, this part is deeply interesting, because she describes there one of the major differences between French fairytales and German fairytales, hightlighted by the comparison of duets (the two Cinderellas, the two Sleeping Beauty, the two Donkey Skins): the treatment of the “fairy” character. The French fairytale fairy, for Robert, is this “character with a shining dress, a star on her forehead and a magic wand in her hand, who arrives exactly when she is needed to solve the love problems of young people”. (This is a bit of a caricature, but that’s also kind of true...). But in the German fairytales? No fairies. They are rather replaced by... “the wise women”.

An old woman, that doesn’t get any description, and who is very ambiguous - when she shows up, the reader can’t tell if she is a protective spirit, or an evil witch. This frightening hag does not have the “shine” of the fairies - she is not admired, she is not beloved. Even whe she is here to bring happiness, she is gaunt and dry. She is the very opposite of the “radiant fairy who, in front of orphans, fuses herself with the figure of the dead mother”. The “old woman” here appears briefly, when all hope is lost, and she is the godmother of no one. If she sometimes assists the birth of those she helps, she never appears for their wedding, and as soon as her task is done she disappears. And in German fairytales, this character is called the “wise-women”. A name with two meanings. She is of course a literal “wise woman”, a woman full of wisdom, but she is also a “midwife” - because “midwives” were traditionally called “wise women”, since it was believed that one needed to know the “rules of wisdom”, aka the strict obediance to the rites presiding over birth, to be able to deliver a baby safely. This is why the “old women” of the Grimms are guardians of rites and taditions, hence why they are feared but respected - before being witches or enchantresses, they were the Greek Moirai and the Germanic Norns, these embodiments of Fate presiding over the destiny of humans (which is why the märchen old woman is often seen weaving). Between the fairy and the witch, the “wise woman” can be good or bad depending on the situations, while neither fully eing one or the other - she only responds to the customs and rites of the great events of life, and is here to highlight their meaning.

To place an example behind her development, Marthe Robert takes the Grimm version of Sleeping Beauty, “Briar-Rose”. In this story, there are thirteen wise-women in the kingdom that the king knows of, but he cannot actually invite them all due to him only having twelve golden plates - and apparently wise-women can only eat in this kind of plates. So the thirteenth wise-woman is purposefully “forgotten”, and this omission is a breaching of the rules of the rituals. This fault leads to the imposition of a serious ban over the baby girl: the prohibition to ever use a spindle. Which means, the inability to live a normal and regular young girl’s life. This prohibition leads to another omission, since all the spindles are destroyed except for one - one that stays in the hands of an old weaver-woman (in which one could reconize the thirteenth wise-woman, according to Robert). And from this second omission comes the last trial: an attenuated form of death, the Hundred-Years Sleep, which will only end with a nuptial rite. “Wrongly birthed”, since her birth is tied to a flawed act, the Beauty cannot develop herself without fearing death at every instant - her transition into teenagehood can only be done through a deep lethargy, and it is with great lateness that she finally “wakes up” through love. [Note: this is a REAL psychanalytic-reading. Having read Bettelheim, thus is pure psychanalysis-interpretation.]

A midwife, a scholar, a wizardess, the “wise-woman” is, for Marthe Robert, a better ancestor of her “ancestor from Antiquity”, than the romantic fairy of French fairytales: her role is to transmit to the individuals who need it the most (aka the children and teenagers) the knowledge of religious and social practices through which man becomes part of the “order of things”, through which man truly “comes into the world” and finds there his “place”. Once we understand that this is the function of the fairytale, it becomes very clear (again, all of this is Marthe Robert’s point of view) why the fairytale is such a paradoxical genre. It becomes clear for example why these stories supposedly for children keep treating a theme that is far away from being childish in nature: the erotic quest of the beloved, through a thousand painful trials. In truth, for Robert, this contradiction only exists for our modern eyes, according to the criteria of a moral pedagogy - but it disappears once we understand that the “wise-woman” character is the one causing the initiation, the advisor of the protagonist, and the keeper of rites.

And this is also why fairytales are, at the same time, so innocents... and so cruel.

[More in my following post!]

#fairytales#fairy tales#grimm fairytales#brothers grimm#french fairytales#perrault fairytales#charles perrault#fairy#fairytale archetypes#the wise woman#witches#comparative fairytales#folklorist vs literary#marthe robert

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

ho scritto un giorno molto giustamente a proposito di qualcuno: “teme che la vergogna gli sopravviva.

Josef K., da Solo come Kafka, Robert Marthe

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

CANNES CONFIDENTIAL (2023 -)

Lucie Lucas as Camille Delmasse & Shy'm as Lea Robert

#cannes confidential#shows#~#lucie lucas#camille delmasse#shy'm#tamara marthe#lea robert#camille x lea#acorn tv#kraina#cannesconfidentialedit#wlwedit#lgbtedit#usergay#wlwgif#wlwsource#otpsource#userspot#userthing#filmtvcentral#dailylgbtq#femalecharacters#userladies#dailytvwomen#femalegifsource#usertreena#tuserjen#tuserhan

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marthe Wiggers by © Robert Harper

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

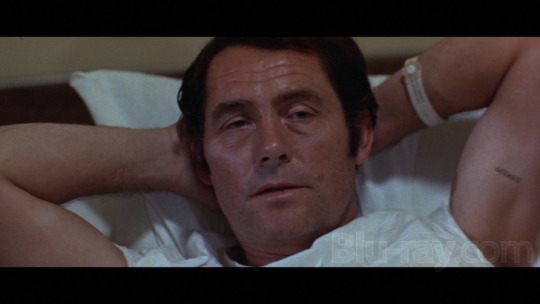

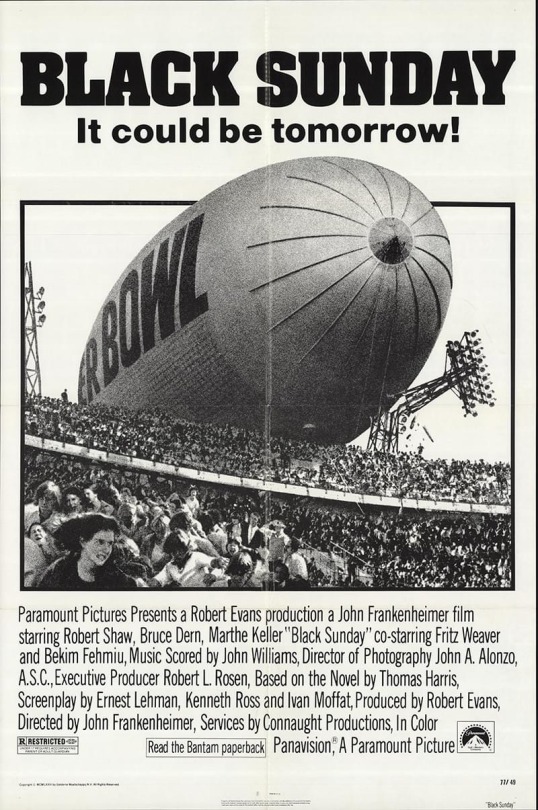

Blu-ray review: “Black Sunday” (1977)

View On WordPress

#Bekim Fehmiu#Black Sunday#Black Sunday bluray#Black Sunday bluray review#bluray#bluray review#Bruce Dern#film#horror#John Frankenheimer#Marthe Keller#movie review#movie reviews#movies#Robert Shaw

1 note

·

View note

Photo

transhet, transneutral bigender, and she/et robert icons

like/reblog if you use and credit me

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Robert Doisneau. Marthe au marché de Pleaux.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fundamentele schilderkunst / Fundamental Painting, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 1975

Artists: Jaap Berghuis, Jake Berthot, Louis Cane, Alan Charlton, Raimund Girke, Richard Jackson, Robert Mangold, Brice Marden, Agnes Martin, Tomas Rajlich, Edda Renouf, Gerhard Ritcher, Stephen Rosenthal, Robert Ryman, Kees Smits, Marthe Wéry, Jerry Zeniuk

Design: Wim Crouwel, Daphne van Peski / Total Design

Photographs: Martien Coppens, Dorothee Fischer, J.J. de Goede, Paul Maenz, André Morain, Nathan Rabin, Cor van Weele, Dick Wolters

(on the way of L'Arengario Studio Bibliografico, FTN books & Art)

#graphic design#art#exhibition#catalogue#catalog#cover#wim crouwel#daphne duijvelshoff#total design#stedelijk museum amsterdam#1970s

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Passant par l'avenue, une silhouette inachevée, un lambeau d'imperméable, une jambe, le bord de devant d'un chapeau, une pluie variant rapidement de place en place.

F. Kafka, Récits et fragments narratifs, Œuvres complètes, Pléiade, t. II, p. 408. Traduction Marthe Robert.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m curious, is your book gonna be like a non fiction history sort of thing or historical fiction? Are there any liberties you’re taking? I’m totally gonna buy that when its done my special interest needs more attention omfg

More like historical fiction. Thanks for asking ! It'll be in French, though.

I do take some liberties, but not a lot. Mostly "fill in the blanks" kind of stuff. Like Charles-Henri becoming his father's assistant at 14 instead of 12. Heavily inspired by the Mémoires.

The main plot with Charles-Henri so far would be:

(of what I already written)

-Charles-Henri gets expelled from boarding school

-Charles-Henri becomes his father's assistant for a spell

-Charles-Henri returns to another boarding school were he gets bullied and befriends the school's corrector. (His job is to whip the kids).

-During this time, he has a misadventure. Basically, his friend is in financial trouble and he gets bullied. His main bully is involved in some not good activity, so Charles-Henri tries to kill two birds with one stone. He gets caught, explains everything, but his plan succeeds anyway. Charles-Henri even manages to manipulate his bully into punching him in front of a teacherHe now has to work extra hard to regain the trust of his teachers.

-His identity is discovered when his dad goes to visit him. They leave almost immediately, and there is some father-son bonding time.

-Charles-Henri is privately tutored by Grisel

-Now, I am at the part, were Charles-Henri nearly litterally dies of boredome because he doesn't get jumped any more.

-(Next to be written) Once healed, he gets to see the theater with his big sis and father Grisel (his tutor), they get recognized and have to make a run for it.

-More bonding and learnign with tutor and big sis (who also crushes on him)

-Charles makes his first comunion, and is very happy about it. Father Grisel is very pleased his pupil made it so far, and everything is cute. The priests gets suspicious about father Grisel, but it's quite inconsequencial.

-Father Grisel finally succombs to his illness.

-Now, Charles-Henri has no other option but to become his father's apprentice.

-Brainwashing from granny and executions

-Sibbling bonding time. The shinigans with his sibblings and his father's other apprentices make it so Charles is more willing to become an executioner. Jean-Baptiste and Anne-Marthe encourage this as this helps avoid in-fighting.

-Eventually, Jean-Baptiste has to leave for Brie-Comte-Robert because of either vacations or actually doing some work there. Charles-Henri was picked at random to go with him, and so Jean-Baptiste, La Blancheur, Caboche, Charles-Henri, Nicolas-Charles Zelles and Petit Matelot all leave for Brie-Comte-Robert. They have to stop at an inn because the horses get too tired to carry the carriage further, and Jean-Baptiste randomly share a table with a musketeer and master swordsman, who was one day branded by Jean-Baptiste's hand. The tavern owner thinks the Sanson are nobility, and they get extra nice service, thinking it would later attract a higher end clientel. They recognize each other and the argument rapidly escalades to the Musketeer drawing his rapier. Jean-Baptiste had left his weapons under lock and key in the carriage seat to eat, and only has a butter knife to defend himself. His hand is gashed, but otherwise, he's unharmed and manages to actually win and wrestles his opponant to the ground. He asks his servant to fetch the roughest brush they can find, and uses it to expose the man's brand in front of the audience, as revenge for outing him as executioner. They are forced to leave. Jean-Baptiste ends up paying double than intended and leaves his silk coat, so that the tavern owner has something to survive on now he's probably out of buisness with this scandal.

-After the Brie buisness is done, they all return to Paris.

-Some time passes, and New Year is upon them.

-January is insanely stressful, with all the extra injuries, all the executions that didn't happen in december happen then, and eventually, Jean-Baptiste's heart gives in. He has a heart attack, he survives but half-way paralyzed.

-Runnign the household with a hemi-plegic head requires a lot fo their attention.

-Rivals all flock, and it's time for Anne-Marthe to shine. And brightly she does, she presents Charles-Henri to the magistrates, but surprise !

-Some rivals have already arrived, they failed, but it means someone had been spreading the news about Jean-Baptiste's declining health.

-Spoiler ! Spoiler ! Spoiler !

-So, a few days later, another rival arrives to their house, and places an ultimatum: the eldest daughter's hand, or he would take Jean-Baptiste's post. He's adult, competant, and the magistrates do seriously consider his candidature. So, the wedding takes place.

-The day before she leaves, Madeleine-Claude-Gabrielle confesses her feelings for her younger brother, and says that if he doesn't want her virginity, it's fine. She then does not need her beauty, and disfigures herself and shaves her beautiful hair in an act of both protest, and because if Charles-Henri doesn't want her, she no longer needs or wants her beauty. The card was already played.

-Charles-Henri attends, and his uncle too.

-In the end, the Lescombats affair happen. Charles-Henri falls for Madame Lescombat or Marie-Louise Taperet. In a last ditch at survival, she manipulates him into distracting the jailers to allow her servant and lover to enter her cell one more time. He then has to listen to the woman he falls head over heels for have sex with another man. Boy is fifteen.

-Some few weeks later, Taperet is no longer pregnant and her lover is dead. So of course, she replaces him with another one, and Charles-Henri has to do this entire thing once again. They both did consider doing it together, but Charles-Henri is too cowardly to break the law under the nose of a rival, and should the plan succeed, would not be able to bring himself to bring his own child to the Hôpital Général.

-Soubise thinks Charles-Henri is the father, and would do anything to prove it.

-He fails, but the hanging is a fiasco, and Charles-Henri nearly dies lynched. He survives with a completely broken finger and many severe bruises on his back.

-The epilogue ends with Nicolas-Gabriel being called in to patch him up, and some after-care insues. The nail matrix has to be destroyed in the surgery to save his finger. Charles-Henri is now convinced that if God allowed him to live, it's to continue the Sanson family legacy. The end.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Faust (F.W. Murnau, 1926)

Cast: Gösta Ekman, Emil Jannings, Camilla Horn, Frida Richard, William Dieterle, Yvette Guilbert, Eric Barclay, Hanna Ralph, Werner Fuetterer. Screenplay and titles: Gerhart Hauptmann, Hans Kyser, based on a play by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Cinematography: Carl Hoffmann. Art direction: Robert Herlth, Walter Röhrig. Film editing: Effi Bötrich.

Power corrupts, as we knew long before Lord Acton so nicely formulated it for us. It's the truth underlying so many myths, from the Garden of Eden to the Nibelungenlied to the Faust legend. Goethe's Faust is a philosophical poem, a closet drama not designed for stage or film, but that hasn't prevented playwrights, opera librettists, or screenwriters from making the attempt. F.W. Murnau's version is probably the most distinguished cinematic attempt, but not because of its fidelity to the source. Murnau's version works because it concentrates on the power struggle, initially between Good, as represented by the archangel (Werner Fuetterer), and Evil, as represented by Mephisto (Emil Jannings), and later by the attempt of Faust (Gösta Ekman) to obtain mastery over Time. It begins with a wager, borrowed from the book of Job, between the archangel and Mephisto, over whom Faust's soul will belong to. Then it eventually devolves into what is the core of most dramatic treatments of Goethe's story, the seduction of Gretchen (Camilla Horn), with the aid of Mephisto. In the end, both Gretchen and Faust are redeemed by his willingness to sacrifice himself, an abnegation of power. But that too-familiar story is distinguished by Murnau's staging of it, with the significant help of Carl Hoffmann's cinematography and the art direction of Robert Herlth and Walter Röhrig. This is one of the most beautiful of silent films because of the interplay between light and dark, a superb evocation of the paintings of Rembrandt in the composition and lighting of scenes. The tone of the film is set near the beginning by the spectacular image of a gigantic Mephisto looming over a German town, which clearly influenced the similar scene in the "Night on Bald Mountain" sequence of Walt Disney's Fantasia (1940). Jannings manages to be both sinister and gross as Mephisto -- the latter mode most in evidence in his scenes with Gretchen's lustful Aunt Marthe (Yvette Guilbert). (If Guilbert looks familiar it's because, as a Parisian cabaret singer during the Belle Époque, she was the subject of numerous portraits by Toulouse-Lautrec.) This was the last of Murnau's films in Germany: The following year he moved to Hollywood, where he made probably his greatest film, Sunrise. He was soon followed to America by the actor who played Gretchen's brother, Valentin, William Dieterle, who became a prominent Hollywood director.

Top: Yvette Guilbert and Emil Jannings in Faust. Bottom: Yvette Guilbert by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Brothers Grimm fairytales facts (2)

10) We left on the last post on the explanation, according to Marthe Robert, of why fairytales were “so innocent and yet so cruel”. Aka, why the märchen keeps evoking blood-spilling actions, murders and mutilations, human sacrifices, as if it wasn’t revolting actions, but rather every-day, common things. This is, according to her, because the crualty is tied to the “ritual world” of which the fairytale is a distant reflection. The fairytale isn’t here to silence or mute the cruelty of life, but to make it manifest. Due to its “initiation ritual” nature of the fairytale, the omnipresence of blood in fairytales makes sense: young girls mutilate their feet upon their wedding night (the sisters of Cinderella, with the “blood in the slippers), young girls have their hands cut-off by their father (The Girl Without Hands), fathers sacrifice their own sons (Faithful John, The Twelve Brothers, The Raven...) and husbands kill their beloved wives. The blood consacrates a ritual transition no one can escape from.

The bloody sacrifice can sometimes be coupled wth an ascetism: a complete fasting, an interdiction of talk or laugh (vows often taken by young girls to help their brothers), a long isolation in a dark forest. In many ways, the trial is the reason of being of the fairytale, the test is its main teaching.

11) Another strong “folklorist” belief pronounced here by Marthe Robert: According to her, one can only be amazed to see how this teaching still survived with a stubborness despite the cultural shifts, and especially despite the influence of Christianity. And she suggest that perhaps, it survived thanks to “those old women, good women or nurses who, passing on the story from generation to generation, by the fireside, played humbly and unknowingly the role of the “wise-woman” and the “fairy”.

12) This is another belief of the “psycho-analytic” reading of the fairytale: “fairytales exclusively talk about families”. There is a whole passage dedicated to that: according to it, this is why fairytales speak so much to children and are better understood by them, and why they believe in them on an instinctual level - because children find in those stories elements they identify with themselves, their parents, their family. According to the interpretation of Robert, fairytales actually exclusively evolve in the familial world, which ends up being confused with the “true” world. As a result, every “kingdom” of fairytales is in fact just the image of a family unit, a well-defined and limited family inside of which a tragedy will happen. The king of the kingdom is always the husband or the father, “nothing else, or at least this is how he is presented to us”. His immense wealth, his political power, his numerous belongings, are only here to “highlight the paternal authority” - because very ofte, beyond his status as a king, nothing much is known of him. Very often, kings are only introduced by “Once upon a time, there was a king who had a son”, and then the story forgets all about the king to follow the son’s adventures - except maybe until the end, where the son has to reconcile himself with his father. In fact, the exact same story plays out when the father isn’t a king, but just an humble man. The king in the märchen is merely a man defined by carnal and affective relationships with the other members of his family. The king is never a bachelor, and when he is a widow (which happens often), his most important business is to find a new wife - and again, this is a structure also found among “common-rank fathers” of fairytales, such as the father of Cinderella. The king cannot stay without a wife, and even less without a child, and every time he is in a bad situation, the narration somehow gets him out of it. As for the queen, she also solely exists to be a wife and a mother, while the prince and the princess embody the son and the daughter - at least untl they create their own families, and mark the end of a rule - the end of the rule of the older generation.

13) So, with “simplicity”, the fairytales of the Grimms are always a “familial novel” with an unmoving schema: a child is born in an anonymous family located in an unknown country. The child is either loved or abused by its parents, and it is worth noting that the worst treatments of the child always come from the mother, whose ferocity clashes with the kindness of the father, who is sometimes a dreamer, sometimes a coward. (Abusive fathers can be found but only rarely - for example in The Twelve Brothers, or in “The goose-girl at the well”, and they pale in comparison to the numerous wicked stepmothers. In fact, the very stepmother position of the abusive mother shows what she is truly: a cruel, devouring, jealous mother who opposes the sweet and loving mother, devoted until her sacrifice - because this mother, with rare exceptions, is always either absent or dead.)

Always, the childhood of the protagonist has some accidents. If the protagonist is loved by their parents, they will be hated by a brother or sister. If the protagonist is surrounded by friendship and affection, they will e hunted down by a fault prior to their birth, usually the fault of one in their family: it can be an omission, a careless wish, a naive promise to the devil. As a result, the protagonist cannot grow up normally: as soon as they become a teenager, they need to leave their family, and go throughout the world... And it is there, in this world of “the dark woods”, where the protagonist needs to lose themselves, that they will encounter lack of resources, anguish, loneliness, and the first touch of love. The protagonist will go down a path covered with perils, where a wicked spirit will be hunting them down - as if leaving their family couldn’t defeat their familial fatality. The only hope of saving comes from encountering the being they will love, and who will “deliver” them from the spell tied to his “infantile attachments”. The one who cannot fully and definitively cut their ties to their family is doomed. The one who manages to cut off all the heads of the dragon wins ; but if the protagonist returns to their house and breaks the promise done to their beloved of not kissing their parents or speaking more than “three words” to them... they will be plunged back in oblivion and unconsciousness, in the chaos of childhood they had such a hard time getting out from. And if, awake dreamers, they accept the spouse prepared by their parents, and thus abandon their free choice of love, they will lose themselves forever by losing their “true love”.

Note: This is here the psycho-analytic reading of the fairytale in all of its splendor. This psychanalytic aspect only gets reinforced by the next sentences, where Marthe Robert compares the prince of the fairytale with Oedipus out of all things! The difference between the hero of a fairytale and Oedipus, is that the hero ends up overcoming his trial and being spared from Oedipus double-crime - the hero manages to overcome the violence manifested within the “father-realm”, by doing so breaks off his “infantile ties” and is thus able to live happily ever after, as a counterpoint to Oedipus who fails to properly defeat the violence and desires of his father. All in all, according to Robert, the fairytale shows that the transition from teenagehood from adulthood is always filled with perils. In short, it is a true “novel of sentimental education”, with a strong pedagogic vocation.

14) Continuing on the “pedagogic nature” of the fairytale, Marthe Robert points out that, even though the realm of the fairytale is a “realm of the desire”, where the wish and its fulfilling are not separated in any way, the märchen still offer points of views and descriptions of the every-day reality, of the hidden/obscure work, of the suffering and the patience that is built up every day ; but these topics are looked at with many different looks - some bright, sometimes piercing, sometimes happy, sometimes sad, but always with “a lot of warmth, a lot of light, and a true love for life”. If the fairytale offers a “consoling world where every misery is balanced by the accomplishment of impossible desires”, it has too much respect to “deny misery itself” - rather, it denotes its presence with a form of melancholy. She points out how in “The Goose-girl at the well”, the story points out that the miracle of tears turning into pearls “doesn’t happen anymore these days, else poor people would soon become rich.” It is true that the fairytale puts an end to the natural laws, but it is still filled wth flesh and blood, it never ignores the body of its hero, it describes characters tormented by hunger, coldness and tiredness. Fairytales also keep the memory of war: the simple soldier will become a king, not so much because of his virtue, but because of his bravery and exploits ; but before that, the soldier will be depicted despondent and humiliated, made bitter and now ready to do anything, as a simple jobless mercenary. “Fairytales do not merely animated vasts countries of which the king is the dream. Like every other deep and poetic works, the fairytale is attentive and respectful of life in its most humble manifestations: through this, it gains its main privilege, which is to lie without giving credit to the illusion, to lie while staying true”.

#fairytales#fairy tales#marthe robert#grimm fairytales#brothers grimm#psychanalytic fairytales#psychanalytic interpretation#german fairytales#fairytale archetypes#fairytale structure

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

all this talk about Chris Pratt as Mario  is making people forget that 3 years ago we had a pokemon movie starring Ryan Fucking Renolds as Pikachu, i’m convinced if Nintendo ever does more movies with their IP‘s in the future they will have the dumbest casting for the main title character

in fact i’m calling some of these rn, ryan gosling as link, Margot robbie as Samus Aran, tom holland as a squid kid, and robert downey junior as marth

#super mario#mario movie#chris pratt#nintendo#ryan gosling#ryan reynolds#pikachu#pokemon#fire emblem#metroid

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

«"Black Sunday," starring Robert Shaw, Bruce Dern, and Marthe Keller, opened today in 1977.»

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

TV & Satellite Week Article - Issue 25 (24 - 30 June 2023)

Tap/Click ‘Keep Reading’ to view the transcript.

Picture Cannes and you’ll probably imagine an azure ocean, the annual film festival or multimillionaires sunbathing on superyachts - but Acorn TV’s six-part romantic crime drama Cannes Confidential is hoping to make it synonymous with screwball comedy and a ‘will they, won’t the? central pairing.

Detective Camille Delmasse (Lucie Lucas) is having a challenging day when she collides with debonair art collector Harry King (Beyond Paradise’s Jamie Bamber) on the Boulevard de la Croisette, wrecking her beloved classic car in the process. Already irritated by the smooth-talking stranger, Camille’s day goes from bad to worse as she and her colleague Léa Robert (Tamara Marthe) investigate the murder of a street artist known as the Jester, only to find themselves crossing paths with Harry...

He pops us everywhere within the town, infuriating her,’ reveals Bamber. ‘They get off on the wrong foot, and the bickering and badinage, an that energy between two people with sexual chemistry finding each other intolerable was what drew me in.’ It soon becomes clear that there’s much more to Harry than he’s willing to let on to anyone, but as Camille comes close to finding out what he’s really up to, he proposes a mutually-beneficial alliance between the two of them.

PIVOTAL PACT

‘When Harry finds out she’s a policewoman, it’s a problem for him because he’s got something to hide,’ says Bamber, 50. ‘But he also happens to know a lot of the characters involved in the supposed wrongful imprisonment of her dad, the former chief of police, so they each have something that the other needs.

‘They have a quick agreement, a sort of poisoned chalice that they each take a sip from, and from that moment, they become more dependent on each other.’

Bamber likens the show to ‘the love child of Moonlighting, The Persuaders! and Miami Vice’ with its compelling blend of a feuding odd couple at its centre and solving crimes in scenic locations, but Cannes Confidential has a few more twists up its sleeve... ‘Léa, Camille’s police partner has designs on her as well,’ explains Bamber. ‘So you’ve got this odd love triangle at the heart of the show, each angle of the triangle antagonising the other.’

For avowed Francophile Bamber, who speaks fluent French, the lure of filming on location in and around Cannes proved impossible to resist - as was the opportunity to deploy his skills for the show’s French-language version. ‘The language was a big deal, because you’ve got a mostly French cast who are working in English and they were real troopers,’ says Bamber. ‘But they shoe was on the other foot when we dubbed into French - I was allowed to dub my own part, but that was when the French actors really came to the fore!’

Navigating a language barrier wasn’t the only difficulty that Bamber faced during filming for the series last summer - the scorching Mediterranean temperatures left him literally hot under the collar. ‘The most challenging thing I had to deal with was wearing a three-piece suit in the sunshine for three months, and trying not to ruin it with perspiration!’ he laughs. ‘My dresser, did amazing work with portable fans, whipping one shirt off and drying it while I wore the other, because I was wringing wet a lot of the time.’

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

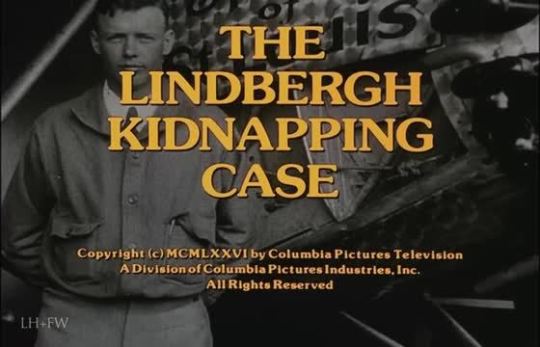

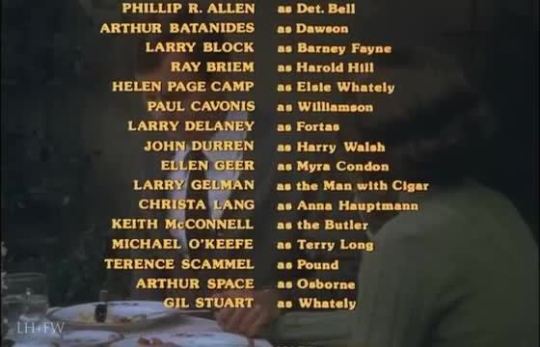

The Lindberg Kidnapping Case - CBS - February 26, 1976

Historical Drama

Running Time: 148 minutes

Stars:

Cliff DeYoung as Charles Lindbergh

Anthony Hopkins as Bruno Hauptmann

Denise Alexander as Violet Sharpe

Sian Barbara Allen as Anne Morrow Lindbergh

Martin Balsam as Edward J. Reilly

Joseph Cotten as Dr. John F. Condon

Peter Donat as Col. H. Norman Schwarzkopf

John Fink as Mr. Anderson

Dean Jagger as Arthur Koehler

Laurence Luckinbill as Gov. Hal Hoffman

Frank Marth as Chief Harry Wolfe

Walter Pidgeon as Judge Thomas Whitaker Trenchard

Tony Roberts as Lt. Jim Finn

Robert Sampson as John Curtis

David Spielberg as David Wilentz

Joseph Stern as Dr. Schonfeld

Kate Woodville as Betty Gow

Keenan Wynn as Fred Huisache

Alan Beckwith as Walter Lyle

3 notes

·

View notes