#navalny sea

Text

Rename the Arctic's seas the "Navalny Sea"

#arctic#ocean#canada#greenland#denmark#finland#iceland#norway#sweden#usa#alexei navalny#yulia navalnaya#aleksei navalny#russian#political dissidents#justice#navalny sea#beaufort sea#barents sea#lincoln sea#white sea#norwegian sea

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny has died in jail, the country’s prison service has said, in what is likely to be seen as a political assassination attributable to Vladimir Putin.

Navalny, 47, one of Putin’s most visible and persistent critics, was being held in a jail about 40 miles north of the Arctic Circle where he had been sentenced to 19 years under a “special regime”. In a video from the prison in January, he had appeared gaunt with his head shaved.

The Kremlin said it had no information on the cause of death.

In early December he had disappeared from a prison in the Vladimir region, where he was serving a 30-year sentence on extremism and fraud charges that he had called political retribution for leading the anti-Kremlin opposition of the 2010s. He did not expect to be released during Putin’s lifetime.

A former nationalist politician, Navalny helped foment the 2011-12 protests in Russia by campaigning against election fraud and government corruption, investigating Putin’s inner circle and sharing the findings in slick videos that garnered hundreds of millions of views.

The high-water mark in his political career came in 2013, when he won 27% of the vote in a Moscow mayoral contest that few believed was free or fair. He remained a thorn in the side of the Kremlin for years, identifying a palace built on the Black Sea for Putin’s personal use, mansions and yachts used by the ex-president Dmitry Medvedev, and a sex worker who linked a top foreign policy official with a well-known oligarch.

In 2020, Navalny fell into a coma after a suspected poisoning using novichok by Russia’s FSB security service and was evacuated to Germany for treatment. He recovered and returned to Russia in January 2021, where he was arrested on a parole violation charge and sentenced to his first of several jail terms that would total more than 30 years behind bars.

Putin has recently launched a presidential campaign for his fifth term in office. He is already the longest-serving Russian leader since Joseph Stalin and could surpass him if he runs again for office in 2030, a possibility since he had the constitutional rules on term limits rewritten in 2020.

337 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexei Navalny returned to Russia in January 2021. Right before he boarded the plane, he posted a film titled “Putin’s Palace: The Story of the World’s Largest Bribe” on YouTube. The video, nearly two hours long, was an extraordinary feat of investigative reporting. Using secret plans, drone footage, 3-D visualizations, and the testimony of construction workers, Navalny’s video told the story of a hideous $1.3 billion Black Sea villa containing every luxury that a dictator could imagine: a hookah bar, a hockey rink, a helipad, a vineyard, an oyster farm, a church. The video also described the eye-watering costs and the financial trickery that had gone into the construction of the palace on behalf of its true owner, Vladimir Putin.

But the power of the film was not just in the pictures, or even in the descriptions of money spent. The power was in the style, the humor, and the Hollywood-level professionalism of the film, much of which was imparted by Navalny himself. This was his extraordinary gift: He could take the dry facts of kleptocracy—the numbers and statistics that usually bog down even the best financial journalists—and make them entertaining. On-screen, he was just an ordinary Russian, sometimes shocked by the scale of the graft, sometimes mocking the bad taste. He seemed real to other ordinary Russians, and he told stories that had relevance to their lives. You have bad roads and poor health care, he told Russians, because they have hockey rinks and hookah bars.

And Russians listened. A poll conducted in Russia a month after the video appeared revealed that one in four Russians had seen it. Another 40 percent had heard about it. It’s safe to guess that in the three years that have elapsed since then, those numbers have risen. To date, that video has been viewed 129 million times.

Navalny is now presumed dead. The Russian prison system has said he collapsed after months of ill health. Perhaps he was murdered more directly, but the details don’t matter: The Russian state killed him. Putin killed him—because of his political success, because of his ability to reach people with the truth, and because of his talent for breaking through the fog of propaganda that now blinds his countrymen, and some of ours as well.

He is also dead because he returned to Russia from exile in 2021, having already been poisoned twice, knowing he would be arrested. By doing so he turned himself from an ordinary Russian into something else: a model of what civic courage can look like, in a country that has very little of it. Not only did he tell the truth, but he wanted to do so inside Russia, where Russians could hear him. This is what I wrote at the time: “If Navalny is showing his countrymen how to be courageous, Putin wants to show them that courage is useless.”

That Putin still feared Navalny was clear in December, when the regime moved him to a distant arctic prison to stop him from communicating with his friends and his family. He had been in touch with many people; I have seen some of his prison messages, sent secretly via lawyers, policemen, and guards, just as Gulag prisoners once sent messages in Stalin’s Soviet Union. He remained the spirit behind the Anti-Corruption Foundation, a team of Russian exiles who continue to investigate Russian corruption and tell the truth to Russians, even from abroad. (I have served on the foundation’s advisory board.) Earlier this week, before his alleged collapse, he sent a Valentine’s Day message to his wife, Yulia, on Telegram: “I feel that you are there every second, and I love you more and more.”

Navalny’s decision to return to Russia and go to jail inspired respect even among people who didn’t like him, didn’t agree with him, or found fault with him. He was also a model for other dissidents in other violent autocracies around the world. Only minutes after his death was announced, I spoke with Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, the Belarusian opposition leader. “We are worried for our people too,” she told me. If Putin can kill Navalny with impunity, then dictators elsewhere might feel empowered to kill other brave people.

The enormous contrast between Navalny’s civic courage and the corruption of Putin’s regime will remain. Putin is fighting a bloody, lawless, unnecessary war, in which hundreds of thousands of ordinary Russians have been killed or wounded, for no reason other than to serve his own egotistical vision. He is running a cowardly, micromanaged reelection campaign, one in which all real opponents are eliminated and the only candidate who gets airtime is himself. Instead of facing real questions or challenges, he meets tame propagandists such as Tucker Carlson, to whom he offers nothing more than lengthy, circular, and completely false versions of history.

Even behind bars Navalny was a real threat to Putin, because he was living proof that courage is possible, that truth exists, that Russia could be a different kind of country. For a dictator who survives thanks to lies and violence, that kind of challenge was intolerable. Now Putin will be forced to fight against Navalny’s memory, and that is a battle he will never win.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexei navalny did not like tragedies. He preferred Hollywood films and fables in which heroes vanquish villains and good triumphs over evil. He had the looks and talent to be one of those heroes, but he was born in Russia and lived in dark times, spending his last days in a penal colony in the Arctic permafrost. A fan of “Star Wars”, he described his ordeal in lyrical terms. “Prison [exists] in one’s mind,” he wrote from his cell in 2021. “And if you think carefully, I am not in prison but on a space voyage…to a wonderful new world.” That voyage ended on February 16th.

Mr Navalny’s death was blamed by Russian prison authorities on a blood clot—though his doctor said he suffered from no condition which made that likely. Whatever ends up on his death certificate, he was killed by Vladimir Putin. Russia’s president locked him up; in his name Mr Navalny was subjected to a regime of forced labour and solitary confinement. Mr Navalny will be celebrated as a man of remarkable courage. His life will be remembered for what it says about Mr Putin, what it portends for Russia and what it demands of the world.

A man of formidable intelligence, Mr Navalny identified the two foundations on which Mr Putin has built his power: fear and greed. In Mr Putin’s world everyone can be bribed or threatened. Not only did Mr Navalny understand those impulses, he struck at them in devastating ways.

His insight was that corruption was not just a side hustle but the moral rot at the heart of Mr Putin’s state. His anti-corruption crusade formed a new genre of immaculately documented and thriller-like films that displayed the yachts, villas and planes of Russia’s rulers. These videos, posted on YouTube, culminated in an exposé of Mr Putin’s billion-dollar palace on the Black Sea coast that has been watched 130m times. Despite the palace’s iron gates, adorned with a two-headed imperial eagle, Mr Navalny portrayed its owner not as a tsar so much as a tasteless mafia boss.

Mr Navalny also understood fear and how to defeat it. Mr Putin’s first attempt to kill him was in 2020, when he was poisoned with the nerve agent Novichok smeared inside his underwear. By sheer good luck Mr Navalny survived, regained his strength in Germany and less than a year later flew back to Moscow to defy Mr Putin in a blast of publicity.

He returned in the full knowledge that he would probably be arrested. On the way back to confront the evil ruler who had tried to poison him he did not read Hamlet. He watched Rick and Morty, an American cartoon. By mocking Mr Putin, he diminished him. “I’ve mortally offended him by surviving,” he said from the dock during his trial in 2021. “He will enter history as a poisoner. We had Yaroslav the Wise and Alexander the Liberator. And now we will have Vladimir the Poisoner of Underpants.”

Mr Navalny was sentenced to 19 years in jail on extremism charges. He turned his sentence into an act of cheerful defiance. Every time he appeared in court hearings via video link from prison, his smile cut through the walls of his cell and beamed across Russia’s 11 time zones. On February 15th, on the eve of his death, he was in court again. Dressed in dark-grey prison uniform he laughed in the face of Mr Putin’s judges, suggesting they should put some money into his account as he was running short. In the end there was only one way Mr Putin could wipe the smile off his face.

In his essay “Live Not by Lies”, in 1974, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, a Nobel-prize-winning Soviet novelist, wrote that “when violence intrudes into peaceful life, its face glows with self-confidence, as if it were carrying a banner and shouting: ‘I am violence. Run away, make way for me—I will crush you’.” Mr Navalny understood, but instead of running he held his ground.

His great strength was to understand Mr Putin’s fear of other people’s courage. In one of his early communications from jail he wrote that: “it is not honest people who frighten the authorities…but those who are not afraid, or, to be more precise: those who may be afraid, but overcome their fear.”

That is why his death portends a deepening of repression inside Russia. Mr Navalny’s murder was not the first and it will not be the last. The next targets could be Ilya Yashin, a brave politician who followed Mr Navalny to prison, or Vladimir Kara-Murza, a historian, journalist and politician who has been sentenced to 25 years on treason charges for speaking against the war. The lawyers and activists who continue to defend these dissidents are also in danger. Since Mr Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, the number of prisoners has increased 15 times. Even as the remnants of Stalin’s gulag fill with political prisoners, professional criminals are being recruited and released to fight in Ukraine.

Mr Navalny’s death also casts a shadow over ordinary Russians. In Moscow and across Russia, people flooded the streets at the news. Before the police started to arrest them, they covered memorials for previous victims of political repression in flowers. Yet that repression is intensifying. Since the start of the war in Ukraine, 1,305 men and women have been prosecuted for speaking out against it. A wave of repression is also swallowing up people who never before engaged in politics. The president will shoot into the crowds if he must.

For the West, Mr Navalny’s death contains a call to action. Mr Putin considers its leaders too weak and too decadent to resist him. And for many years Western politicians and businessmen did much to prove that fear and greed work in the West, too. When Mr Putin first bombed and shelled Chechnya in the early 2000s, Western politicians turned a blind eye and continued to do business with his cronies. When he murdered his opponents in Moscow and annexed Crimea in 2014, they slapped his wrist. Even after he had invaded Ukraine in 2022, they hesitated to provide enough weapons for Russia to be defeated. Every time the West stepped back, Mr Putin took a step forward. Every time Western politicians expressed their “grave concern”, he smirked.

The West needs to find the strength and courage that Mr Navalny showed. It should understand that Mr Navalny’s murder, the soaring number of political prisoners, the torture and beating of people across Russia, the assassination of Mr Putin’s opponents in Europe and the shelling of Ukrainian cities are all part of the same war. Without resolve, the West’s military and economic superiority will count for nothing.

Western governments should start by treating people like Mr Kara-Murza as prisoners of Mr Putin’s war who need to be exchanged with Russian prisoners in the West or prisoners of war in Ukraine. They should not stigmatise ordinary Russians living under a paranoid dictator and his goons, or put the onus on ordinary people to overthrow the dictator who is repressing them.

The best retort to Mr Putin is by arming Ukraine. Every time America’s Congress votes down aid, Russia takes comfort. The leaders assembled at the Munich Security Conference, who heard Mr Navalny’s wife, Yulia, speak of justice for her husband’s death, need to stiffen their resolve to see through the war. For their part Ukrainian politicians must see that standing up for Russian activists and prisoners is also a way of helping their own country—just as Mr Navalny called for peace, for rebuilding Ukraine and the prosecution of Russian war crimes. Liberating Ukraine would be the best way to liberate Russia, too.

The voyage ends

After he had been poisoned, Mr Navalny returned home because he believed that history was on his side and that Russia was freeing itself from the deadly grip of its own imperial past. “Putin is the last chord of the ussr,” he told The Economist a few months before he took that last fateful journey. “People in the Kremlin know there is a historic current that is moving against them.” Mr Putin invaded Ukraine to reverse that current. Now he has killed Mr Navalny.

Mr Navalny would not want Mr Putin’s message to prevail. “[If I get killed] the obvious thing is: don’t give up,” he once told American film-makers. “All it takes for evil to triumph is the inaction of good people. There’s no need for inaction.”

Mr Navalny’s death has seemed imminent for months. And yet there is something crushing about it. He was not alone in believing that good triumphs over evil, and that heroes vanquish villains. His courage was an inspiration. To see that moral order so brutally overturned is a terrible affront. ■

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why would President Emmanuel Macron threaten to send French soldiers marching into Ukraine to fight the Russians? asked Alba Ventura. Macron shocked his NATO allies last week by saying that he hadn't "ruled out" deploying ground troops to help Ukraine win its battle against invading Russian forces. "Nobody followed him" to second the idea - not the U.S., not the U.K., not a single other NATO member - and "he is fully aware of being isolated." He had simply been pushed too far. Early in the war, he had "maintained dialogue with Vladimir Putin," but in recent months, Russia has been increasingly aggressive toward France, conducting cyberattacks and even threatening to shoot down French planes over the Black Sea.

And the last few weeks brought "a confluence of events": the assassination of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, Ukraine running out of ammunition, and the Americans' feckless inability to get aid through Congress. With Germany too weak to give a European response, Macron deployed "the weapon of a nuclear-power president" and threatened Russia outright.

His domestic rivals on both left and right may condemn him as a warmonger, but that only makes them look weak. Macron's saber rattling "shows the French that when it comes to defending French values" in Ukraine, only he is willing to step up.

THE WEEK March 15, 2024

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexei Navalny, who has died suddenly aged 47 while in prison, was Russia’s best-known campaigner against high-level corruption. For many years he was the leading critic and opponent of President Vladimir Putin and his political party, United Russia.

Repeated arrests, jail sentences and physical assaults did not deter Navalny from digging up financial scandals, which he published on his blogs and X feeds as well as YouTube. In a 2011 radio interview, he described United Russia as a “party of crooks and thieves”, which became a powerful and popular mantra on social media and at political protests.

Repression did not stop him attracting enthusiastic crowds in support of opposition politicians in local elections in cities across Russia. Occasionally he ran for office himself, most notably in 2013 for the mayoralty of Moscow, when the official result gave him 27% of the vote – which he said was rigged so as to deny him victory.

In 2016, Navalny launched a campaign for the 2018 presidential election but was barred by Russia’s central election commission due to a prior criminal conviction. In 2017 he was attacked with a spray, leaving him partially blind in one eye. In 2019 Navalny fell ill in prison, from what he claimed was poison. His most dramatic brush with death came in 2020 at the end of a political campaign trip through Siberia, when he was taken seriously ill on a flight from Tomsk to Moscow. His condition was so grave that the pilot made an emergency landing in Omsk, where he was rushed to hospital. Navalny’s wife and supporters asked for him to be taken to Germany, where they felt he would be better treated.

The Russian authorities agreed and Navalny was flown to the Charité hospital in Berlin, where toxicology tests showed traces of the nerve agent novichok in Navalny’s body. Russian officials complained that the test results were not made public nor disclosed to them. Navalny recovered and was released from hospital after a month.

He decided to convalesce for several weeks in Germany. Russian court authorities announced that if he returned late to Moscow he would be jailed for breaking the terms of a probation order. The threat was seen as a device to deter Navalny from returning to Russia in the hope, as the authorities saw it, that in exile his influence would rapidly decline.

Showing great courage, but defying the advice of his family and friends, he flew back to Moscow in January 2021, accompanied by his wife and dozens of journalists, and was arrested on landing. His Anti-Corruption Foundation promptly published on YouTube an investigation with pictures of a luxury multimillion-dollar mansion on the Black Sea, which they dubbed Putin’s palace.

Navalny’s stock had never been higher at home or abroad, and when a court gave him a two-and-a-half year sentence, western political leaders, including the US president, Joe Biden, protested openly and imposed sanctions. But Putin was determined to destroy him politically.

In 2022, Navalny was sentenced to an extra nine years after being found guilty of embezzlement and contempt of court. In 2023, he was given a further 19 years in prison on extremism charges.

Navalny was born in Butyn and grew up mainly in Obninsk, a small town south-west of Moscow. His mother, Lyudmila, worked as a lab technician in micro-electronics and then moved to a timber-processing factory. His father, Anatoly, a Ukrainian, was in the military. In addition to Russian, Alexei learned Ukrainian through spending summers with his grandmother near Kyiv. He gained a law degree (1998) at the Peoples’ Friendship University in Moscow.

In 2000 he joined the United Democratic party, known as Yabloko. Under its leader, Grigory Yavlinsky, the party stood for liberal and social democratic values. Navalny gained an economics degree at the Financial University (2001), and from 2004 to 2007 served as chief of staff of the Moscow branch of Yabloko. A charismatic speaker, he was attracted by the concept of television debates, and in 2005 founded a social movement for young people, with a name taken from the Russian word for yes, DA! – Democratic Alternative, which was active in the media.

Navalny started to move gradually to the right, and in 2007 he was expelled from Yabloko after clashing with Yavlinsky over Navalny’s increasingly nationalist and anti-immigrant views.

He then co-founded a movement known as Narod (The People), which aimed to defend the rights of ethnic Russians and restrict immigration from Central Asia and the Caucasus. A year later he joined two other Russian nationalist groupings, Movement Against Illegal Immigration (MAII) and Great Russia, in forming a new coalition called the Russian National Movement.

It made little impact and Navalny turned his attention to journalistic muckraking. His main outlet was a blog, LiveJournal. In 2010 he published leaked documents about the alleged theft by directors of millions of roubles from the pipeline company Transneft. The following year he exposed a scandalous property deal between the Russian and Hungarian governments. He decided to establish the Anti-Corruption Foundation, which continued until his death.

He also went back into electoral politics, leading street protests over unfair practices by United Russia. Navalny urged people to vote any way they liked in the 2011 parliamentary elections, including for the Communist party, so long as they voted against United Russia. He was tempted to run against Putin in the 2012 contest for the presidency, but said the ballot would be rigged. After the poll, he led several anti-Putin rallies in Moscow and was briefly arrested.

The following year Moscow was to elect its mayor. Navalny registered as one of six candidates. The next day he was sentenced to five years on embezzlement and fraud charges. Initially he called for an election boycott, but when he was released on appeal he changed his mind. Some analysts speculated that Putin wanted him to run to make the electoral contest look genuinely open. Navalny lost to the incumbent mayor and Kremlin ally Sergei Sobyanin, but claimed to have won. In 2016 he announced he would stand against Putin in the 2018 presidential contest. More arrests and repression followed.

Navalny’s nationalism put him in agreement with Putin on one major issue: Crimea. The territory had been ceded to Ukraine in 1954, but in 2014 Putin used force to reincorporate it into Russia. Navalny said he would not return it to Ukraine if he had the power to do so. Like Putin, he argued that Ukraine was an artificial construct. “I don’t see any kind of difference at all between Russians and Ukrainians,” he said, while admitting his views might provoke “horrible indignation” in Ukraine.

However, his agreement with some of Putin’s views on Ukraine did not bring him to support Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. That March, Navalny released a statement from jail. Through his spokesman he urged Russians “to overcome their fear” and take to the streets and demand a “stop to the war” against Ukraine. He called Putin an “obviously insane tsar”. “If in order to stop the war we have to fill prisons and paddy wagons with ourselves, we will fill prisons and paddy wagons with ourselves.”

“Everything has a price, and now, in the spring of 2022, we must pay this price. There’s no one to do it for us. Let’s not ‘be against the war’. Let’s fight against the war.” At the end of 2023 he was transferred to the remote penal colony at Kharp, north of the Arctic circle.

In 2000 he married Yulia Abrosimova, and she and their daughter, Daria, and son, Zakhar, survive him.

🔔 Alexei Anatolievich Navalny, politician and anti-corruption campaigner, born 4 June 1976; died 16 February 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Dictator Vladimir Putin probably hates this film which Alexei Navalny made about his greed and corruption. That's the best reason to watch it!

Much of the documentary focuses on what we call the Putin Palace – Vlad's opulent crib on the Black Sea near Gelendzhik. The Putin Palace makes Saltburn look like a cheesy AirBnB. The Putin Palace is said to be the largest single residence in Russia.

Speaking of Saltburn, this is even longer than that film. So make sure there's plenty of popcorn on hand. 🍿

Since it's probably banned in Russia, look at ways of sending this vid to friends and family there which can get around digital censorship.

EDIT: Putin is as afraid of the dead Navalny as he was of the living Navalny.

Russian digital map service reportedly blocking reviews at memorial sites visited by Navalny mourners

Alexei Navalny death latest: Putin critic’s wife says Kremlin ‘waiting for novichok poison’ to leave his body

Putin's assassination of Navalny seems to be turning into another Russian public relations disaster.

#alexei navalny#russia#vladimir putin#the putin palace#documentary#film#putin's corruption#oligarchs#greed#assassination of navalny#алексей навальный#Геленджик#путинский дворец#коррупция#олигархи#владимир путин#долой путина#путин - вор#путин хуйло#путин – убийца#путина в гаагу!#нет войне#путин – это лжедмитрий iv а не пётр великий#союз постсоветских клептократических ватников#руки прочь от украины!#геть з україни#вторгнення оркостану в україну#деокупація#слава україні!#героям слава!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

15 questions meme

Tagged by @saiditallbefore :)

Are you named after anyone? Not really. I choose my name and I picked names that weren't emotionally connected. I considered using my grandfather's name but it is pretty common and a somewhat famous trans guy I can't stand has it.

When was the last time you cried? While watching the graveside flowers being left at Alexei Navalny's grave, seeing the crowds in the streets of Moscow risking their lives to pay their respects. Devastating. I struggled to write for a week after he died. Nalvany was four years older than me and I'd watched him work for a long time. His death felt like the destruction of something so irreplaceable and beautiful. But in the darkness of it, there were people finding themselves and the fortitude to keep going. Navalny's dream for the beautiful future of Russia will not die with his body.

Do you have kids? No. I have never wanted to be a parent. The moment I learned about pregnancy and what was possible when I was around 9-10 years old, I immediately began planning to get sterilized as soon as possible.

What sports do you play/have you played? None. I was not athletically gifted as a kid and opportunities/money were not something I had. I took fencing at university and loved it, but it's an expensive hobby.

Do you use sarcasm? I do, but I like to think I achieve a better balance of sarcasm and earnestness these days. Like a lot of people, I went through that very grim/sarcastic phase. But I value genuine enjoyment more. Death to cringe culture and people afraid to just enjoy things/let other people enjoy things.

What is the first thing you notice about people? Probably their clothes. If they have interesting accessories.

What is your eye color? Green, very green. Possibly the one thing about my physical form that has never disappointed me.

Scary movies or happy endings? Are we meant to think these things are mutually exclusive? Because I think they go together. Look on the very basic level I'm more likely to watch a scary movie just because most happy ending movies are relentlessly heterosexual and I find that boring.

What are your talents? I'm a good cook and baker. I can follow a recipe and improvise as needed. My particular traumas mean when someone needs emergency services I know how to get things done in a crisis and can save the freak out for later. I can spin endless stories.

Where were you born? In the Panhandle Plains of Texas, where the sky goes on forever. You can see a storm coming for miles. It was land that the Comanche roamed for generations, traversing the seas of grass and the Caprock. The second largest canyon in America is there and it is beautiful. They've reintroduced bison and they roam. It is stark and empty and terrible in some ways but also beautiful.

What are your hobbies? Reading, writing, gardening, doing the occasional fidgety crafty sort of thing. Casual bird watching from my windows. I like to try different things and I'm going to try weightlifting next.

Do you have any pets? A cat who is 21+ years old named Jasmine. She is pretty deaf and has two heated beds plus a heating blanket on the couch for her comfort.

How tall are you? Five foot four inches as I have been for about 30 years. Disappointing to me but probably ultimately irrelevant.

Dream job/career? I have now, which is to say I do not have a job. I'm a house husband and a writer. Work is a scam and we live in a capitalist hellscape. My dad spent his entire life doing a job he hated because it was wrapped up in the idea that a Man did certain things. The longest I ever stayed at a job was seven years, the shortest was one week. Quitting is always my favorite part.

Tagging a couple of people if you want to play the meme game @balconyskeletons @yourstrulyknits @by-ilmater @udunie @sineala

#personal#I tried to make my answers interesting#because what are these random questions for#if not to try to make something beautiful

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

No demonstrations in the West after Navalny's death. Don't the boys who want to liberate Palestine "from the river to the sea" wish for a free Russia?

#hamas#hamas is isis#palestine#israel#russia#russian#russians#vladimir putin#putin#vladimir#alexei navalny#navalny#rip navalny

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A former nationalist politician, Navalny helped foment the 2011-12 protests in Russia by campaigning against election fraud and government corruption, investigating Putin’s inner circle and sharing the findings in slick videos that garnered hundreds of millions of views.

The high-water mark in his political career came in 2013, when he won 27% of the vote in a Moscow mayoral contest that few believed was free or fair. He remained a thorn in the side of the Kremlin for years, identifying a palace built on the Black Sea for Putin’s personal use, mansions and yachts used by the ex-president Dmitry Medvedev, and a sex worker who linked a top foreign policy official with a well-known oligarch.

In 2020, Navalny fell into a coma after a suspected poisoning using novichok by Russia’s FSB security service and was evacuated to Germany for treatment. He recovered and returned to Russia in January 2021, where he was arrested on a parole violation charge and sentenced to his first of several jail terms that would total more than 30 years behind bars.

Putin has recently launched a presidential campaign for his fifth term in office. He is already the longest-serving Russian leader since Joseph Stalin and could surpass him if he runs again for office in 2030, a possibility since he had the constitutional rules on term limits rewritten in 2020.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexei Navalny is dead.

Neither Murashko, nor Mizulina, nor Milonov, not once in their long careers have they suddenly crashed on the road into someone's car, drowned in the sea, or choked on a potato, but for some reason it was just before the election that the "foreign agent" had a heart attack. And in such a way that the intensive care unit could not pump him out. Now I understand what it means to see with your eyes, to understand with your mind, but not to have the language to say it in such a way that it is a fact, a fact, not an afterthought and conspiracy. Killed. Killed, but now it will go from word of mouth - "accident, impaired health" - and we will repeat it like sweethearts.

I love this country, but my language has been uprooted.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

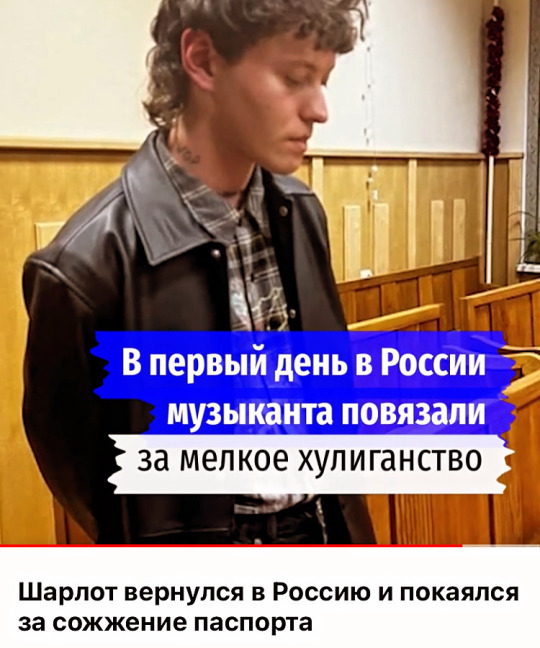

Шарлот вернулся, как Навальный.

Надеясь жить, как музыкант.

В стране кровавой, аморальной,

Чтоб выжить, должен быть талант:

В искусстве ползать на коленях

Там надо сильно преуспеть.

Придёт повестка и тюленем

В окопы уползти на смерть.

Считать, что над страной нависли,

Чтоб только на неё напасть,

Поэтому и сотни тысяч

В мир мёртвых следует украсть.

И что границы расширяя,

И продвигая русский мир,

Там, за горами и морями,

Получишь сказочный пломбир.

Ну а без этого Шарлоту

Не провести уже концерт.

Скорей служить в штрафную роту

Его отправит офицер.

Нужны в штрафбате пианисты,

Чтоб гнать на подвиги народ

Кантатой дьявольских амбиций,

Сюитою «кремлёвский чёрт».

Разбавить ноты и харизму -

Искусство подсобит в бою…

Шарлот мечтал о мирной жизни,

Но стыд и срам в родном краю.

######################

Charlotte returned back, like Navalny,

He hoped to live like a musician fellow.

But in a bloody, immoral country,

In order to survive, one must have a big talent:

In the art of crawling on ones knees

One have to be very successful all times.

And if a summon will come like a seal

One have to crawl into the trenches to die.

Trust that enemies were hanging over the country,

Just to divide it like Hitler and Stalin divided in the past Poland.

And it was a root cause why hundreds of thousands people

In the world of the dead getting quickly stolen.

Trust that expanding the boundaries,

And promoting the Russian world as a dream.

Somewhere, beyond the mountains and seas,

One will receive a fabulous ice cream.

Well, without this talent, Charlotte

Wouldn’t be able to conduct a concert.

He would rather serve in a penal company

Reporting to the aggressive and drunk officer.

Pianists are needed in the penal battalion,

To drive soldiers to heroic deeds

A cantata of devilish ambitions may matter

It was written by the kremlin beast.

A bit of inspiring notes and charisma,

And art may help to the battlefield gang.

Charlotte dreamed that his ife will be peaceful

But pain and darkness embraced native land.

#книга#стихи#поэзия#poetry#война#украина#россия#шарлот#ukraine#russia#politics#history#war#peace#musician#музыкант#москва#петербург#concert#концерт

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best Picture

“All Quiet on the Western Front”

“Avatar: The Way of Water”

“The Banshees of Inisherin”

“Elvis”

“Everything Everywhere All at Once”

“The Fabelmans”

“TÁR”

“Top Gun: Maverick”

“Triangle of Sadness”

“Women Talking”

Best Director

Martin McDonagh (“The Banshees of Inisherin”)

Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert (“Everything Everywhere All at Once”)

Steven Spielberg (“The Fabelmans”)

Todd Field (“TÁR”)

Ruben Östlund (“Triangle of Sadness”)

Best Actress

Cate Blanchett (“TÁR”)

Ana de Armas (“Blonde”)

Andrea Riseborough (“To Leslie”)

Michelle Williams (“The Fabelmans”)

Michelle Yeoh (“Everything Everywhere All at Once”)

Best Actor

Austin Butler (“Elvis”)

Colin Farrell (“The Banshees of Inisherin”)

Brendan Fraser (“The Whale”)

Paul Mescal (“Aftersun”)

Bill Nighy (“Living”)

Best Supporting Actress

Angela Bassett (“Black Panther: Wakanda Forever”)

Hong Chau (“The Whale”)

Kerry Condon (“The Banshees of Inisherin”)

Stephanie Hsu (“Everything Everywhere All at Once”)

Jamie Lee Curtis (“Everything Everywhere All at Once”)

Best Supporting Actor

Brendan Gleeson (“The Banshees of Inisherin”)

Brian Tyree Henry (“Causeway”)

Judd Hirsch (“The Fabelmans”)

Barry Keoghan (“The Banshees of Inisherin”)

Ke Huy Quan (“Everything Everywhere All at Once”)

International film:

“All Quiet on the Western Front” (Germany)

“Argentina, 1985” (Argentina)

“Close” (Belgium)

“EO” (Poland)

“The Quiet Girl” (Ireland)

Best animated feature:

“Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio”

“Marcel the Shell With Shoes On”

“Puss in Boots: The Last Wish”

“The Sea Beast”

“Turning Red”

Original screenplay:

“Everything Everywhere All at Once”

“The Banshees of Inisherin”

“The Fabelmans”

“Tár”

“Triangle of Sadness”

Visual Effects:

“Avatar: The Way of Water”

“Top Gun: Maverick”

“The Batman”

“Black Panther: Wakanda Forever”

“All Quiet on the Western Front”

Music (original score):

Volker Bertelmann, “All Quiet on the Western Front”

Justin Hurwitz, “Babylon”

Carter Burwell, “The Banshees of Inisherin”

Son Lux, “Everything Everywhere All at Once”

John Williams, “The Fabelmans”

Original song:

“Applause,” from “Tell It Like a Woman”

“Hold My Hand,” from “Top Gun: Maverick”

“Lift Me Up” from “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever”

“Naatu Naatu” from “RRR”

“This Is a Life” from “Everything Everywhere All at Once.

Documentary feature:

“All That Breathes’

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed”

“Fire of Love”

“A House Made of Splinters”

“Navalny”

Original screenplay:

“The Banshees of Inisherin”

“Everything Everywhere All at Once”

“The Fabelmans”

“Tár”

“Triangle of Sadness.”

Adapted screenplay:

“All Quiet on the Western Front”

“Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery”

“Living,”

“Top Gun: Maverick”

“Women Talking.

Cinematography:

James Friend, “All Quiet on the Western Front”

Darius Khondj, “Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths”

Mandy Walker, “Elvis”

Roger Deakins, “Empire of Light”

Florian Hoffmeister, “Tár”

Costume design:

“Babylon”

“Black Panther: Wakanda Forever”

“Elvis”

“Everything Everywhere All at Once”

“Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris”

Animated short:

“The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse”

“The Flying Sailor”

“Ice Merchants”

“My Year of Dicks”

“An Ostrich Told Me the World is Fake and I Think I Believe it"

Live action short:

“An Irish Goodbye”

“Ivalu”

“Le Pupille”

“Night Ride”

“The Red Suitcase”

Film editing:

“The Banshees of Inisherin”

“Elvis”

“Everything Everywhere All at Once”

“Tár”

“Top Gun: Maverick”

Sound:

“All Quiet on the Western Front”

“Avatar: The Way of Water”

“The Batman”

"Elvis”

“Top Gun: Maverick”

Production design:

“All Quiet on the Western Front”

“Avatar: The Way of Water”

“Babylon”

“Elvis"

“The Fabelmans."

Makeup and hairstyling:

“All Quiet on the Western Front”

“The Batman”

“Black Panther: Wakanda Forever”

“Elvis”

“The Whale”

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earlier this month, the imprisoned Russian politician Alexey Navalny released, with the help of his team, an extended essay on who should be held responsible for the erosion of democracy in Russia. Navalny’s insistence that Russia’s authoritarian turn under Putin is rooted in the unprincipled politics of the 1990s sparked a discussion about how much that period still matters in determining the outlook of contemporary Russia. Timothy Frye, the author of “A Weak Strongman: The Limits of Power in Putin’s Russia,” discussed this question with Meduza special correspondent Margarita Liutova. Meduza presents a condensed English-language version of Timothy Frye’s side of that conversation, edited lightly for clarity.

After communism

Many factors drive institutional choice; the most important is the bargaining power of the different groups who write the rules. If we look at a country like Uzbekistan, for example, the same people who were in power in the late 1980s got to write the rules in the early 1990s. And lo and behold, they gave a lot of power to a president everyone knew would remain in power. And so, Islam Kerimov managed to write constitutional rules in his own favor.

In other settings, there’s a lot more bargaining that takes place. For example, if we look at Russia in 1990 and 1991, there was a great deal of bargaining within the Russian Federation between the RSFSR Supreme Soviet and the newly-created presidency, as they tried to figure out the actual rules — because often institutional choices are made at a very abstract level, to be defined further as politics happens. It’s very difficult to define an institution so precisely that the rules would address every contingency. This is why we have constitutional courts, which can help legislatures and presidencies interpret the rules. But in the post-communist world, constitutional courts were quite weak. This renders institutional choice more of a function of the political struggle between the main groups in power.

In the Russian case, the great difficulty was that there were leftist forces (headed by the Russian Communist Party) and more liberal forces (headed by President Yeltsin), and these competing forces with different policy preferences controlled different institutions, using those institutions to pursue their own policy goals.

In contrast, weakened communist parties in Eastern Europe and the Baltic states had to reform themselves and become supporters of democracy and market economics. We saw this in Poland and Hungary, for example. The differences between Polish communists and liberals were within the normal range of politics. A traditional left camp and a traditional right camp fought over policy, but it was within the range of normal political outcomes.

In cases like Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, there was very little political turnover, and it was easy to agree on the rules because there was no one to oppose them.

But cases like Russia, Bulgaria, and Romania are particularly interesting because they feature largely unreformed communist parties holding significant political power and liberal groups holding roughly equal political power. Throughout the 1990s, the Russian Communist Party had the largest membership. It was also the best-organized party, given its history and the institutions that it was able to preserve. It’s also just very difficult to build new parties from scratch. In Russia, the liberal wing could never coordinate a common policy platform beyond opposing the Communists.

Rebuilding the ship while at sea

Throughout Eastern Europe, liberal parties struggled with coordination far more than their ex-communist rivals, particularly where there wasn’t a natural leader, or where infighting (between social-democratic and pro-market camps, for example) distracted liberal groups from vying for power.

Those groups lacked the kinds of institutional resources that the communist parties had inherited: various organizations, lists of supporters, hierarchies that are really difficult to create from scratch. It typically takes a long time to build parties, and in Russia the ship had to be rebuilt while at sea, with the 1992–1993 inflation crisis and the 1994 war in Chechnya.

Also, post-communist transitions had no historical precedent, and the countries enacting them were not just building market economies and more competitive political systems; they were also trying to rebuild states that had great difficulty collecting revenue, judicial systems, and political parties — all at the same time. It was a very chaotic period, regardless of the country you were in.

In principle, countries can be stable as long as everybody agrees on the basic set of rules: agreement as such matters more than the decision to play by the rules of a parliamentary system, or to play by the rules of a presidential system, or to have a federal system allocating specific powers to subnational units, as opposed to the center. But what often happens is that stakeholders fight about the rules and how to interpret them, rather than fighting within the parameters of a particular kind of political system.

In Russia, the rules were constantly being rewritten. The root of the fight that led to the conflict between the presidencyand the parliament in 1993 was over decree power and what it would mean to grant presidential authority to issue decrees on economic policy. It was also about how to change the constitution,given that the Supreme Soviet had repeatedly changed it. And when the rules constantly change, it’s very difficult for businesses to attract investment, to produce new products, or to plan for the future.

Still, as long as the groups that are losing in policy terms under the current rules are determined to keep playing by that same set of rules, that system of rules will remain in place. So, for example, if there’s an election and one party loses, that party can challenge the election and say it was fraudulent and that they won’t accept it and will protest and resort to violence. Or they could say: We lost this time, but the rules themselves are legitimate, and if we play by the same rules again, we might win in the next round. As long as the groups that lose today think that they can win tomorrow under the same rules, they will continue to abide by those rules.

Regarding constitutional design, political scientists often say that rules which reduce the gains to the winners and the losses to the losers are generally better in the long run than rules that allow one party to take all.

There are also cases like Hungary, where, according to the rules of the 2018 election, Viktor Orbán’s party received about 48 percent of votes but got 66 percent of the seats. Rules that allow huge gains on small margins of victory are often really dangerous because they make it seem that if you lose today, you will lose forever. This means you must fight to change the rules, instead of continuing to play by them.

Putin and the lawless 1990s

In the early aughts, when Putin came to power, Russia had many different options. What happened in the 1990s did not determine what followed. We can criticize the economic and political reforms of the 1990s, the corruption, the loans-for-shares deal, which many people thought was wrong even then. But the fact is that when Putin came to power in 2000, Russia could have gone in many different directions.

The great failure of the 1990s was the failure to build institutions like a legislature, a party, a business association, or strong regional governments that could have constrained Putin from consolidating power in his own hands. Political scientists always assume that politicians want to take more power. And what prevents them from doing so are groups that can threaten them with removal from power if they try to take all power into their own hands. In Russia, there were powerful governors and business people, but they acted as individuals rather than as organizations.

Why didn’t institutions spring up, then? First, it takes time to build institutions, and the polarization we saw in Russia prevented the left and the right from agreeing on a set of rules that everyone would be willing to follow. Another factor was the price of oil.

Economic reforms in Russia were starting to turn the corner in 1996–1997. Growth was starting to return, but the East Asian financial crisis in 1997 caused oil prices to plummet. Oil prices in 1996 and 1997 were $12 and $17 a barrel. This made it really difficult for the government to collect the revenue needed to pay pensions and salaries for bureaucrats, the police, and the military. There was a sense that the government wasn’t working, and this made it harder for people to play by the rules.

The prevalent notion about privatization — the transfer of state assets to private hands — had been that it would lead various groups to demand a single set of rules for everybody. In Russia, however, privatization largely sanctioned or formalized what was already occurring on the ground. By then, managers had taken control of the enterprises, and the state was too weak to reclaim it. So, the state just recognized the managerial control over the enterprises, and the managers then became an interest group more interested in seeking rents for themselves than in building a broad coalition to support a single set of rules.

Everybody hates privatization. If you look across the post-communist world, privatization has been incredibly unpopular everywhere, even in places where economic reforms were largely successful. But I do think that the loans-for-shares privatization, which took place before the 1996 election and where the state relinquished control over some of its most valuable assets, was a mistake. And later, Vladimir Putin re-established control over those assets in a way every bit as ugly as the way they were privatized in the first place.

Vladimir the Lucky

The banking sector was the big beneficiary of the high state bond prices, since the banks were buying a large portion of those bonds. Essentially, they became a pro-rent-seeking lobby that benefited from the government’s hunger for money. In a sense, the worse things were for the government, the better they were for the banks and the people buying these bonds as long as the government could repay them. After President Yeltsin’s election in 1996, it looked like the economy was starting to turn the corner. Privatization was largely over, and inflation was coming down. The sharp economic declines of the early 1990s had stopped, and the economy was just starting to recover when oil prices collapsed. That made it extremely difficult for the Russian government to raise the revenue to pay off those bonds. The oligarchs, banks, and foreign investors who bought those bonds then blocked policy change.

The 1998 financial crash broke this pro-inflation, pro-rent-seeking coalition of banks and oligarchs. When Putin came to power, the main institutions of a market economy were all in place: there were free-floating prices, private property, and a currency that was undervalued, making exports very profitable. And then, oil prices surged, which meant that Vladimir the Lucky joined Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great in the succession chain of Russian power. The economic conditions for a boom were already in place — not because of what Putin did, but because of the 1998 financial crash and what he’d inherited from his predecessors.

When Putin came to power, the concern was less about autocracy than about the weakness of the Russian state. The whole gamut of people, from liberals like Gaidar to Putin supporters, shared this view. If we look at what Putin did in his first three years in office, he conducted a lot of economic reforms that had broad consensus among the elites. But oil prices stayed high, and Putin could deal with the governors and business people piecemeal, buying them off one at a time and consolidating power in his own hands.

When a leader has to bargain with other groups who wield the power to remove him, this may turn into an autocracy, albeit an autocracy where a party or the military constrains the ruler. Russia, on the other hand, turned into a personal autocracy where it was Putin making all the major personnel and policy decisions, without a single institution being able to keep him from doing what he wants.

Once an autocrat consolidates power in their own hands, it becomes very difficult to get them to relinquish it. Typically, they can use the power they have today to expand the power they have tomorrow. So, the real battle of trying to prevent an autocracy comes before the autocrat consolidates power. To compel Putin or any Russian leader today to bargain with other groups when making policy, it would have been necessary to create institutions before 2004–2007.

If we think of Russia in the 1990s, Yeltsin was a very powerful president on paper, but he still had to bargain with the parliament to get the budget passed, to get it to spend money on government programs, and there were big fights around the budget every year. What Putin was able to do when he came to power was to deal with the powerful governors and the powerful business people, and then to create a majority within the parliament, which Yeltsin never had. By the time Putin decided to consolidate power in his own hands, no one could stop him.

A different narrative

The 1990s were pivotal in Russian history, and the discussion around this period has become very politicized. The Kremlin tries to paint the 1990s with a broad brush, as pure chaos, impoverishment, and subjugation before the West. There’s also a camp within the opposition to Putin that is very critical of the democrats during the 1990s, blaming them for creating the conditions that allowed Putin to seize power. But I think it’s important for us to look at what actually happened and to recognize the great difficulties of the period.

Even well-intentioned politicians would have found it very hard to make the transition without having lots of corruption and making lots of mistakes. We must recognize just what a difficult task it was to go from a political system with no private property or autonomous institutions and basically no civil society, when that system collapsed overnight. The 1990s were a complex political task, and we should avoid using this period to score political points, either for the regime or its liberal critics.

I think the conditions of a post-Putin era will be very different from those in the 1990s. The rudimentary institutions of a market economy are already in place, and people already know about competitive politics. I’d also point out that voting rates in Russian presidential elections in 1996 and 2000 were higher than in the United States in those same two years. So, the notion that Russians are somehow unfit for democracy just doesn’t hold water.

Weak democracies can govern pretty well, often better than weak autocracies. I’m skeptical of the notion of building a weaker autocracy instead of a weaker democracy. If you value voting rights, equality before the law, and other liberal rights that go along with liberal democracy, those are almost by definition going to be greater under a weak democracy than under a weak autocracy. Given the choice, seeing Russia as a strong, capable, stable democracy would be the best choice. Failing that, a weak democracy would be preferable to a weak autocracy, as far as ordinary Russians are concerned.

The key to preventing the rise of a new autocracy is to build institutions: business associations, legislatures, regional governments — any kind of organization that can make life difficult for a would-be autocrat. I think that’s the important task for building a post-Putin Russia. In the interim, maintaining ties with the outside world and preventing Russia from becoming even more isolated is an important goal. A good task for right now is to think about what a post-Putin Russia would look like and which resources within and outside of Russia might allow Russians to build a more open, competitive political system in a post-Putin era.

The human capital in Russia is still quite good and can be used to build a better Russia in the future. Russians can begin addressing these long-term structural conditions even today, and this is an important agenda for those interested in building a more open and democratic Russia in the future. Diversifying the economy and rebuilding society after the war would also be important. And ending the war itself is critical. Typically, wars produce deep cleavages within societies, unless they’re short victorious wars where people rally around the government. Longer wars tend to be much more divisive. How Russia deals with the fallout from the invasion of Ukraine is likely to be an issue that will last for a very long time.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russia-Ukraine Daily Briefing

🇷🇺 🇺🇦 Friday Briefing:

❗ Ukrainian drone damages building in Moscow disrupting air traffic

- US approves sending F-16s to Ukraine from Denmark and Netherlands

- Lukashenko admits Russian troops invaded Ukraine through Belarus in 2022

- Ukraine gets two IRIS-T air defense systems from Germany

- Russia progressing on mass production of attack drones

- Turkey 'warned' Russia after Black Sea ship attack

- Ukraine may receive remaining Czech Soviet-made helicopter gunships

- US sanctions four Russians involved in the poisoning of Navalny

- Mass surveillance in Russia expands rapidly since Ukraine invasion

- Russian colleges to introduce drone operator training programs

- Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania join G7 declaration of support for Ukraine

📨 More news in a daily newsletter: https://russia-ukraine-newsletter.beehiiv.com/subscribe

💬 Keep up with me on Twitter: https://twitter.com/rvps2001

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Chancellor: The Remarkable Odyssey of Angela Merkel (Kati Marton, 2021)

"On the one hand, she has called for European solidarity and has led the way in calling out Putin’s human rights violations.

But even as Putin’s most vocal domestic adversary lay in a coma in a Berlin hospital, Merkel declined to cancel the Nord Stream 2 pipeline project, which will pump gas directly from Russia, across the Baltic Sea, and into Germany.

When finished, the project will pour billions into the Kremlin’s coffers and provide fuel for only one member of the EU: Germany.

Allowing Nord Stream to proceed exposed in Merkel’s record a blind spot that is hard to square with her many principled positions, but it serves as a reminder that she is also a calculating politician.

It is true that Europe’s energy landscape has been dramatically altered by a recent shift away from Russian to US and Norwegian natural gas, and by antitrust cases against Gazprom, the Russian state-owned gas company.

The EU under Merkel has become far more interconnected in this and other areas.

But her professed ambition of a Europe that behaves as a mature bloc, with a united foreign policy, is undermined by this unilateral act.

Moreover, the country that will most suffer if Nord Stream is completed is one where the chancellor has spent a great deal of time and effort: Ukraine.

Kyiv will lose over $1 billion a year in transit fees once the pipeline is completed under the Baltic Sea.

Merkel no doubt weighed all these factors, including how bad the optics would be if she proceeded.

The issue, long predating the Navalny episode, has perplexed some of her staunchest allies.

“Every time Obama asked Merkel why she was going ahead with Nord Stream, Merkel gave a different answer,” Charles Kupchan, an Obama administration national security advisor told me.

“Pressures from the business community, domestic politics, keeping her coalition together, this is not her decision to make, and so on—always a different answer.”

The true answer was likely all of these factors combined.

One of Merkel’s favorite explanations in complex circumstances is “The advantages outweigh the disadvantages.”"

2 notes

·

View notes