#other scholars have articulated it better this is by no means an original thought but uhh. your son's childhood idol repudiates him publicl

Note

Ooooohhhhh do tell me how much marcs parents would hate the rosquez suituation

i mean. marc didnt throw away those valentino model bikes.

#how long. do we think he wouldve kept them.#callie speaks#motogp#asks#rosquez#other scholars have articulated it better this is by no means an original thought but uhh. your son's childhood idol repudiates him publicl#and then his fans trash ur kid online and he is obviously deeply distressed about it. and your house gets broken into by italian press.#and then your son MARRIES HIM

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dating the Lich HC's:

*Hey babes! Ofc dating the Lich is going to entail a lot of angst, so this is a official trigger warning for themes of manipulation, mind control and superiority complex in the context of a romantic relationship. Also he never turns into Sweet P in this universe, he just fucken dies lol. Be warned! Also, as always, explicit NSFW under the cut*

Dynamics:

The Lich has brewed his presence for ten thousand years and he will forever more. He is of a million worlds, and will spread infinitely, like a virus inside a weak body.

This being is both larger than life and less than a singularity, and taking a physical form means nothing in the long run. His existence is not in a form, but in a purpose. A role he must fulfill not to keep the balance of the universe, but to maintain its sporadic nature and eventually be the heat death that puts an end to it.

In this universe, the one you were in, originally you were one that was of modest values. Live your life, do it moderately, and be happy with it.

That is until you ran into an eight foot tall decaying horn man with glowing eyes. He took hold of your mind immediately.

The Lich does not see you as a being, or as a purpose, but rather, he sees you as his. His to play with and ponder until the end of time, until the very end of himself.

He promised you a higher state of consciousness until you both eventually succumbed to his very nature. To be a part of his legion forever, then some, and then never again.

Your heart was his instantly.

Romance:

We all know that this romance will be nowhere near conventional or healthy. In the first few months of it, you don't have a choice until he can sense that you'll follow along willingly. In those first few months, he controls almost every move you make.

You are by his side. Not in battle nor in planning, but you are there to be his anyways. This is how you exist, now.

It could have turned out worse, you supposed. But seeing how he lured people into his green pit of power, seeing how he destroyed, seeing Finn and Jake's hurt faces when they happen upon you? There wasn't much to convince you that it didn't turn out the worst way possible.

Eventually, however, you grow numb to this. For awhile, after the handful of defeats doled out by your two heroes, you two traverse the stars. He mainly focuses on his mission, save for the small moments of food, rest and privacy you need.

You focus on him.

You're smart enough to not try and ask too many questions of him. Prodding destruction's physical embodiment when you don't know their temper isn't a wise move.

Still, though. It doesn't matter. He senses your curiosities, and sometimes he makes himself home in your mind and hears your questions whispered through his ears.

Sometimes he pretends like he didn't hear them. Other times, when he's in a better mood, he'll humor you.

'Where are we going next?' You thought, stars and void blurring past you as you both sail the heavens.

"To the Lambda Cancri system, that is what your kind called it long ago,"

It still shocked you sometimes, how he could so easily break your mind and eat the contents like a yolk. You wondered if he would ever acknowledge your newfound admiration for him.

"Thank you,"

"You are welcome"

Eventually, you two make it to the Lambda Cancri system.

There is no planet to land on. It would be another journey to the next system to hopefully replenish energy, but you wouldn't complain.

"Look. One star, another. A binary star system triggered by gravitational force and interlocked in a dance, forever, until one consumes the other. Look."

"I see," And you were telling the truth. You sense that this was a metaphor for a relationship bigger than those stars, bigger than the Lich and Finn themselves, bigger than Ooo.

He turned to look at you. Slowly, he touched you, and he knelt in the vacuum of space until his forehead touched yours.

"My side, until the end of time,"

NSFW:

There isn't much time the Lich has to satiate those pesky little needs of yours. And even if he did have time, he would not waste magic on creating the proper body parts to help you in those needs anyways.

Eventually though, even though he is knowing of most things, he grows curious of your specific reactions. The noises you could make, if you'd muffle them or if you'd scream.

You're not expecting for him to smuggle you inside an inn the next planet you two rest at.

He rents a room, he takes you up the stairs, and as soon as he shuts the door he makes your clothes vanish at the snap of his fingers.

There is no true heat behind his eyes, none of the wanting for himself. Just a veiled curiosity, something you often feel for him.

You get on the bed and present yourself to him. Again, you're wise enough to wait for his orders. To not test him.

He rewards this behavior with a stroke on the cheek, a comforting gesture that tingles from the raw, dry texture of skeletal fingers.

He slowly moves down. As the last scholar of GOLB, he has had habits that have not passed through him. He studies you.

He puts his tongue on you; not too warm and not too cold, but very articulated to your points of pleasure.

You're quickly overstimulated.

He does not stop during the night. It is all you could have ever asked for out of the Lich.

#Adventure time#the lich#the lich x reader#lich#lich x reader#lich king#lich king x reader#finn mertens#finn#jake#jake the dog#Ooo#angst#kinda sad lol

231 notes

·

View notes

Photo

hello anon!! okay, this is going to be a very long post, so buckle up. standard caveat: since i don’t know the specifics of your topic or discipline or situation, some of this will hopefully be relevant and some of it might not, so just grab what works for you and leave the rest! and if you have more specific questions that this general overview doesn’t touch on, feel free to send those in.

it sounds like you have a few different questions here:

How do I find and articulate my research question?

How do I effectively take notes on my background reading in the early stages, when I’m not sure yet what my argument is going to be?

How do I organize a long research project/paper? How do I conceptualize something that has so many moving parts & happens to be a genre (a thesis) that I’ve never written before?

How do I write something that long?

also I am not sure if by “diss” you mean a senior thesis, master’s thesis, or a doctoral dissertation, as I know US and non-US universities use different terminology! so I will kinda just respond to this as A Very Lengthy Research Paper.

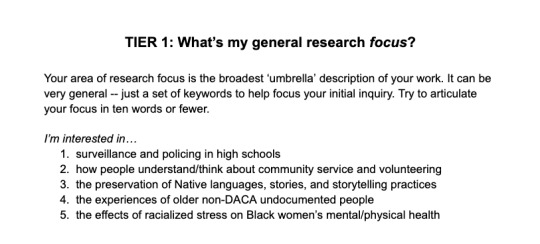

my response here will focus mostly on that first question (how to find/articulate a research question), with some thoughts at the end about notetaking in the early stages of a big research project. I’m going to lay out a method I just used with my own students to help them articulate questions & generate possible lines of inquiry to follow. I have been calling it the ‘research tier’ activity/system but it’s a pretty basic way of mapping out possible directions for a project. I use some version of this for every big project I undertake - whether it’s academic work, planning a course syllabus, or writing fic.

I want to emphasize, before I start, that the “tier” map you construct is a LIVING document, not a set-in-stone plan that has to be finished before you begin. the goal is to get past the anxiety of the blank page by generating tons and tons of ideas and questions related to your central topic -- so that if you hit a dead end, you can trace your way back and follow a different line of inquiry. when i am working on a research project, i am continually updating this planning document (i’ll say more about that at the end, once you have a sense of what the tiers look like).

Those questions are geared towards my students, who are working more in social science-y disciplines and/or on projects that have clear connections to specific communities. If you are writing a more traditional humanities discipline, here are some other examples:

I’m interested in...

the romance novel as a genre

Virginia Woolf’s writings on nature/the environment

the cultural reception and impact of the TV show Will & Grace

what queer social life looked like in 1920s New York

play and playfulness in the college classroom (my current research project, which I’ll use as an example)

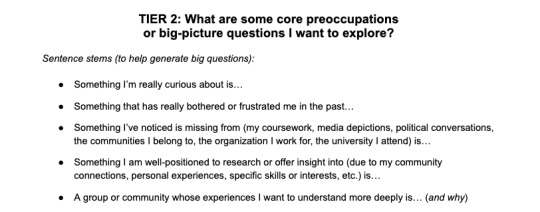

once you have some idea of your focus, you can begin generating questions related to that focus. “Tier 2″ begins to get slightly more specific, though you are still very much in “big picture” mode. here’s some sentence stems I give my students to help them generate tier 2 questions:

my students are doing research projects that are ideally supposed to develop out of their preexisting community involvements or commitments, so i give them this additional advice:

[note: if your thesis topic is in a social science-y discipline (or a humanities discipline that leans closer to the social sciences), you can probably use some of those ideas or prompts. if your thesis topic is more of a purely academic humanities-type topic (for instance, a literary studies thesis about a specific novel), not all of those will apply perfectly, but some will hopefully be useful still!]

here’s an example, again using my playfulness project. I’ll list the question and then below it, in italics, I’ll explain what ‘stirred up’ that question for me.

T2: What are some core preoccupations or big-picture questions I want to explore? What are some things I’ve noticed that I want to understand?

Core Question 1: Why are college classrooms so serious? Why is there so little playfulness in most college teaching? Why so little laughter, movement, fun?

Observing my friend’s kindergarten classes made me realize how much elementary educators rely on bright colors, movement, singing, playing imaginative games together, etc. to engage young learners’ imaginations, minds, and bodies. Why do we value that so much in elementary education, but stop considering it important in college classes? Do learners “age out” of a need for highly interactive, engaging learning? I suspect no... so that’s a hunch I can begin to follow.

Observing other college courses (and drawing on my own experience as an undergrad and grad student) made me realize how much educators rely on the same standard methods of teaching (lecturing with a discussion section; a version of Socratic seminar discussion that is primarily led by the professor). To me, these methods are antithetical to playfulness and tend to quash people’s ability or desire to playfully experiment, try things out, risk failure, etc. I wonder if the actual methods we use to teach content or to structure our classes are producing ‘serious’ classes, whether or not we personally as instructors want that to happen. That’s another hunch I could follow...

I’m thinking of a possible connection here to my past research on the origins of English literature as a discipline (in 1920s-30s England). One of the things that scholars often emphasize is how hard faculty had to work to transform English into a serious, rigorous, ‘legitimate’ discipline, akin to the hard sciences. That’s something that I think we still see today in the way people anxiously defend the value of a humanities education. I’m curious about whether the need to justify our existence as a discipline/field of study influences our methods of teaching college students. Do we banish playfulness from the classroom because it threatens that image of the humanities as a serious, rigorous discipline? That’s yet another hunch I could follow...

Core Question 2: I have a hunch that people learn better in playful environments. Is that true -- and if so, why? What is it about playfulness that enhances learning?

I’m a lifelong fangirl, and fandoms are creative environments where people are continually engaged in acts of imaginative play. I’ve observed and have experienced firsthand how these playful environments seem to encourage people to try new things, take creative risks, learn new skills even if they’re afraid they’ll be ‘bad’ at them, and commit huge amounts of time, energy, and passion to long-term creative projects that don’t make any money or ‘earn’ them a grade. I’m curious about how we might adapt the playful, passionate energy of fan spaces to college teaching.

In my own classrooms, I’ve noticed that students get so much more into the activity (and seem to internalize the content more deeply) when I frame it as an imaginative exercise, a roleplaying activity, or a game of some kind. Teaching the same content in a way that encourages playfulness seems to produce deeper engagement (and deeper learning?) than using the traditional methods of ‘serious’ teaching.

Core Question 3: Playfulness and shared laughter/fun seem to build social bonds (again, drawing on my experiences in fandom). Could shared imaginative play help students develop better social skills? Could it help build a sense of community in the classroom and strengthen students’ sense of belonging? This question feels especially urgent to me given the epidemic of self-reported loneliness, anxiety, and depression on college campuses.

*

You can have lots more than 3 core questions/preoccupations! In fact, the more ideas you can generate at this stage the better. The idea isn’t to hone in on your research question (yet) but to generate as many possible paths you could take, so that you can begin evaluating which interest you most, or which seem like the most fruitful questions to explore/answer. Doing the idea-generating for Tier 2 should already begin to set you up for Tier 3 -- which involves articulating specific sub-questions you’ll need to answer to better understand or answer those core questions/preoccupations.

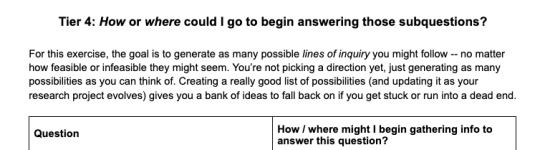

and then we’ll go ahead and fold in T4, as I tend to move back and forth between T3/T4 as I brainstorm.

I’ll just take one of my Tier 2 questions as an example, but again, you can/should do this for all of yours (or at least the ones that interest you most).

Core question: Playfulness and shared laughter/fun seem to build social bonds (again, drawing on my experiences in fandom). Could shared imaginative play help students develop better social skills? etc etc

T3 subquestions (with T4 “directions for inquiry” folded into the first one, so you can see an example):

-- SubQ1 Does play actually strengthen social bonds? If so, how? Are specific kinds of play better for this than others (ie, collaborative or cooperative play compared to competitive play)? With Tier 4 folded in:

Do a library database search to try to figure out where “play” research typically happens -- is it in psychology research? Neuroscience? Early childhood education?

Then begin searching for different keyword strings that might help me gather up initial sources. Some initial ideas: play + social bonding, play + social skills, play + social development, play + cooperation, play + friendship, play + mental health. (Typically finding a couple useful/relevant articles will help you generate better keywords -- as you can begin to see the kinds of terminology that researchers use to describe your topic.)

I could also maybe interview college students themselves, or design a survey - but that would depend on the type of research I want to do. Do I want to conduct my own original research study, or is my focus more on synthesizing existing research from different fields to construct an argument?

Could I find faculty or researchers who work on these topics, who might be able to direct me to specific resources or help me understand what kind of work has already been done on this topic? Maybe I can’t find someone who specifically researches playfulness, but an educational researcher whose work focuses on social-emotional learning would probably have a pretty good understanding of what features or pedagogical choices help create positive, affirming learning environments.

-- SQ2: Are college students lonely?

Are they reporting (or do they experience) higher rates of mental illness? What are the numbers on this?

What are some of the prevalent theories or hypotheses about why this is? Could social isolation or difficulty forming friendships be a possible contributing factor?

-- SQ3: Why are social bonds good for us - physically, mentally, emotionally?

-- SQ4: Do social bonds enhance learning? If so, how?

What if I looked to other non-academic learning environments (such as fandoms, team sports or group activities, etc where people are learning new skills in highly social settings) to make a case for playfulness in the college classroom? This isn’t direct 1:1 proof that “more playfulness in college classrooms = happier, more socially well-connected students,” but offering detailed descriptions of how those learning environments are structured might spark ideas for my audience (university instructors and administrators) or persuade them that playfulness has an important social-emotional role to play in college learning.

*

Typically what ends up happening is I produce a huge, messy document (or fill a giant paper or whiteboard if I’m doing it by hand) that has tons and tons of different directions I might follow. usually, the initial process of creating this giant brainstorming document sparks lots of ideas for where to begin researching. then, as i go off and begin reading articles, those articles typically help flesh out my understanding of the core questions or concepts i’m interested in, or my understanding of what kind of research on this topic already exists vs. where the gaps are that my own work might be able to fill. that initial source-gathering phase of research will also usually spark new questions and sub-questions, which get added to my tier map.

having some kind of messy brainstorming map/plan also helps me read in a more focused way. instead of just opening a random article and skimming it without any clear sense of what i’m looking for, i’m now opening articles and reading them with a purpose -- i’m looking for answers to the specific questions i’ve articulated. so i can skim in a more focused way, looking for specific keywords that seem relevant, and i can also take notes in a more focused way, noting down key ideas that

having a question in mind can also help me figure out more quickly if the article is relevant to my research questions or not. for instance, let’s say i open an article about how playing competitive games in high school PE classes improve students’ self-reported moods. if i didn’t know what i was reading for, i might spend a lot of time on this article, trying to figure out if it was relevant to my research (it has the keywords, right? so maybe it’s relevant?). but if i am reading with a specific question in mind (“Do collaborative learning games help strengthen students’ sense of social connection?”) I can tell pretty quickly that this article is not going to be that useful, since it focuses on competitive physical games (probably not something I’ll integrate into an English class). so I can say with some confidence, “I probably don’t need to read this whole thing, but maybe I’ll check out their lit review section or their bibliography to see if the authors cite any other work on play/playfulness that might be more relevant to my specific questions.”

i think i’ve kinda started to answer your second question about notetaking here, too, so i will also say that in the early stages of a big research project, i am absolutely NOT taking detailed notes on any of the sources i find. my focus is much more on amassing a large pool of highly relevant sources that i know i’m going to want to go back to and read more deeply as my research questions come into sharper focus. this is because deep reading burns through a lot of time and energy, so i want to make sure i’m saving that deep reading energy for sources that are quite likely to be relevant to my project.

to figure out if a source is relevant, I often skim the abstract and introduction to figure out the core questions the article or chapter is seeking to answer. then I ask myself three questions:

Are the core questions of this article the same as (or very similar to) my core questions or subquestions? If so, mark this citation as HIGHLY relevant - I’m going to want to come back and read this source carefully, to see if it’s already suggested answers to the questions I’m asking.

Do the core questions of this article seem to resonate with my core questions, even if we’re not asking them in exactly the same way, or the author of this paper is applying them to a different field? If so, mark this citation as LIKELY relevant - it may not be a perfect 1:1 with my own questions, but that can sometimes spark exciting new ideas or ways of reframing my original questions. If not, toss it.

Do the questions this article is asking suggest new questions or lines of inquiry that I am interested in exploring? Sometimes an article will introduce me to a whole new area of research or a new array of questions I hadn’t even originally thought to explore. If that’s the case, I typically pencil those sub-questions into my brainstorming tier document and mark the source as LIKELY or HIGHLY relevant, depending on how excited i am about it.

OK I WILL CLOSE HERE FOR NOW as I have to get back to work, but I will say that when I taught my students this method, they were very confused by the initial explanation of it, but then when they went back and used the models to work through the tier brainstorming activity for themselves, they seemed to find it really useful. so if you are scratching your head, try doing a quick TIER 1 - TIER 2 - TIER 3 - TIER 4 map for your own research question to see if doing it yourself helps clarify. also: if you can’t get further than tier 2, it’s usually a sign that you need to do some more reading and freewriting about the questions that you’re curious about, or the gaps you’ve noticed in the scholarship, or the threads you’d like to follow. but you can do some of that background reading in a more focused way now, using your initial big questions to help guide your selection of background readings & give you a sense of purpose as you read.

#this research 'system' would be CHILLING to some of my hyper-organized academic friends#who are all about using highly structured systems for tagging sources and managing citations and so on#but it works well for my brain & for the way i think#which tends to be very associative and focused on generating connections#i cannot tell if this is helpful or not aha i feel like students often want me to give them a highly structured method#and my answer is usually just like#research is a creative process#and like any creative process there are probably some 'best practices' or helpful methods people can teach you#but you figure out your own way of doing it based on how your brain processes and organizes information & makes connections#i was going to add 'things get less messy in the later stages for me' to reassure you & my horrified hyperorganized friends aha#but that is just a lie#usually i am cutting up drafts and moving pieces around and mindmapping and doing visual representations of sections#right up until the polished final draft#research#mw

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

meddling; the good kind

i decided to clear up a few questions abt how Marui Zenji became Bookmaster of WGO in Genesis so ig this is also my commission payment/holiday gift for @polar-stars

in which a double shot of jager (with some help from the nakiri cousins) pretty much cements marui zenji’s future.

If nothing else, Yoshino Yuki knew turkey. Like, really well.

Much to Zenji’s chagrin, the only takeaway he’d gotten from the American history seminar he and the rest of the PSD gang had enrolled in was that the Pilgrims rode a Dutch fluyt to Virginia back in 1620, but they’d decided to turn Christmas into a Polar Star tradition nevertheless. Wait. Massachusetts? Thanksgiving?

After losing pitifully in a game of hangman to Yukihira Souma of all people — seriously, how was the English lang and composition seminar supposed to prepare him to guess “#tarkeyshet” — Zenji had retreated to the corner of the kitchen to sulk and drink Sakaki Sake while Yukihira paraded around fixing an imaginary pair of glasses and knocked back a shot of Smirnoff Watermelon from Kurokiba’s locker at Legislation.

“Those specs really were for nothing,” Yuki grinned as she pulled him to his feet, took away his solo cup, and handed him a masher. “Come on, Marui. You can vent at the potatoes.”

Zenji aggressively articulated his ire at said potatoes to the point where Yuki had to yank the bowl from him. “The hell, are you trying to make extract? Go kill another turkey if you’re feeling murderous.”

“I’m fine,” sighed the dark-haired chef, massaging the bridge of his nose. “It’s out of my system now. But the sake is not.”

Yuki leaned in and whispered in his ear, “Sacrifice one battle and you’ll win the war.”

“Now since when have you been all philosophical?”

Without missing a beat, Yuki countered, “Since you got all mopey. Now help me bring the turkey out.”

Just then, Nakiri Erina entered the kitchen after knocking on the doorframe. The first seat took one look at Yuki with her mouth basically on Zenji’s ear and dropped her vodka. “I apologize for the intrusion!”

She was already halfway out the door when Yuki and Zenji bellowed, “This isn’t what you think it is!”

Erina glanced doubtfully at the space (or lack thereof) between the Polar Star originals. “Um… in that case. Yoshino-san, do you mind if I talk to Marui-kun for a moment?”

“Not at all,” Yuki replied, and Erina was too distracted to notice the slightest inflection of irritation in the teal-eyed girl’s voice as she took the turkey out of the kitchen.

“How may I be of assistance, Nakiri-san?” Zenji asked, shifting his glasses and sitting on a kitchen stool.

“I was talking to my mother earlier today,” Erina said after picking up her cup, a diplomatic air automatically washing over the area. “She was wondering when you would be available for an interview sometime in the next few days over winter break.”

Zenji gave a prominently uncharacteristic “Eh?”

With a thin smile, Erina continued, “My mother would like to have you intern with her so she can judge if I was right when I told her you’re going to be the next WGO bookmaster. I remember you mentioned something about memorizing all of the WGO guides in first year?”

Zenji blinked once. Twice. “You’re kidding me.”

“No, I am not,” the heiress replied. “I never kid.”

He gestured at her. “That was a kid just now.”

“Besides the point, Marui-kun. My mother would like me to give you her phone number so you can text her your schedule availabilities directly.” Then she added, “Also, that’s more convenient for me because I don’t have to be a mediator.”

At this, Zenji’s eyes bugged out to the size of his fucking glasses. The WGO bookmaster — and Nakiri Erina’s mother to boot — wanted to give him her phone number?

Marui Zenji needed medical care hella fast.

“Um… I’m available whenever she is…?”

Erina shook her head. “I wouldn’t get used to it, but she’s catering to you.”

A sheen of sweat broke out on Zenji’s forehead. He pushed back his bangs and gave a long, pronounced exhale. “In five seconds, Nakiri-san, I will wake up and be so disappointed that I miss classes for the first time in my entire life.”

“You have a perfect attendance record, don’t you?”

“Yes, actually.”

“Perfect. That means you can afford to skip a day without getting detention. Unlike me and Yukihira.” Erina tapped her chin thoughtfully as Zenji made an indignant noise, then as if to deter any individuals that may have been eavesdropping, said in a low voice, “The one stipulation for giving you my mother’s phone number is that you ask Yoshino-san on a date.”

Zenji promptly fell off the stool. “Say what now?”

The eavesdropping individual made her debut just then. “Yes, well, as official relationship counselor of Nakiri Mansion and Polar Star, I am privy to some very public confidential information that you and Yoshino-san are both absolute nuts for each other. So I am prescribing you the following action: get the hell on with it already.”

The Nakiri cousins looked extremely pleased with themselves.

“I agree with Alice,” Erina said primly. “It’s pretty obvious how much she likes you. And since we’re both extremely well-versed in the subtleties of romance, I do believe we’re more than qualified to make this diagnosis.”

“Oh, and look, Marui-kun. Your ears are turning red. Actions speak louder than words. Your silence speaks volumes.”

Zenji squinted at Erina. “Nakiri-san, am I correct to assume that even if I already had the Bookmaster’s phone number, we’d still be having this conversation?”

“Duh,” said Alice. “Now’s your chance, Marui-kun.”

“I think I’d rather lose to Yukihira in another game of hangman,” he said nervously.

At this, Alice gave a sympathetic smile. “You, my friend, do not have the emotional capacity of a brick, unlike Ryo and Yukihira, so you should have nothing to worry about. Come on.” Alice grabbed Zenji’s wrist and yanked him to his feet. “She’s in the dining hall. Have a shot if you need the liquid courage.” She passed him a cup of Jager.

The scholar ran a hand through his bangs in an attempt to organize his hair, despite the fact that he already had the neatest cut in like… a ten-mile radius.

“This is for the Bookmaster,” Zenji said, trying to convince himself more than the cousins.

“No, it’s really not,” Alice replied. “Now get to it. Clock is ticking.”

“Also, every second you spend stalling is technically another second you’re ghosting the Bookmaster.”

Zenji exploded into action. He threw back the Jager and sprinted out of the kitchen at a velocity nobody would’ve dared imagine possible for someone of his figure… or his alc tolerance.

“That worked better than I thought it would,” Erina mused.

“Yukihira’s rubbing off on you,” Alice intoned. “You sounded a lot like him just now.”

Rolling her eyes and fighting the blush, the first seat waved off the statement. “As if I would ever be associated with anything influenced by his plebeian mouth.”

“Like… your tongue?”

“Shut the fuck up.”

Alice grinned and tapped her cup against her cousin’s. “Damn right I will, Erina. No need to emphasize the truth.”

The others were all gathered in the dining hall by the time the Nakiri cousins emerged from the kitchen. Zenji was — as expected — sweating as he attempted to approach Yoshino Yuki.

Souma and his strangely acute senses noted exactly what was happening (read as Erina had already filled him in on the details of the plotcounseling session), and he vaguely motioned for Yuki to turn around.

“Yoshino-san,” Zenji began, and those that knew what was going on were all surprised at how steady his voice was despite the fact that he’d just drank what had to be two normal shots of herbal liquor at an ungodly speed. “If you’re available, I was just wondering if you’d like to go on a date with me?”

Yuki’s eyebrows disappeared behind her bangs. “Wait, what?” The rest of the dorm gave an excited whoop.

“… to the Polar Star garden…?”

“GODDAMMIT, MARUI,” they all squawked. Yuki managed an awkward grin and the will to live utterly disappeared from Marui Zenji.

Erina and Alice exchanged a glance. “Call the jet.”

“Gotcha. Ryo, can you fetch the Eclipse, please?”

“It’s on the roof already,” drawled Alice’s former aide. “Come on, Marui,” Ryo continued. “You’re gonna be like the rest of us by the time the sun comes up.”

“The hell does that mean?” sighed the dejected erudite as Ryo dragged him to the rooftop staircase in the back of the building.

“We’re destroying your perfect attendance record so you don’t have more honors cords than all the Elite Ten members combined at the graduation ceremony. Don’t even think about complaining. This is for our—I mean, your—good.”

The Nakiri cousins herded Yuki out of the dining hall after him, and the rest of the social club followed.

“In you go,” Ryo ordered once they were in front of the jet. He damn near picked up the chef who was probably half his weight and chucked Zenji through the hatch. Yuki was prodded on board after him, bleating timid complaints the entire time.

Ryo briefly entered the jet and they heard him instruct the pilot, “Take them to the Nakiri resort in Kobe. Don’t let them come back until tomorrow evening, am I clear?”

“Yessir,” replied the pilot, and then Ryo jumped out and the engines roared to life.

The inhabitants of Nakiri Mansion looked rather pleased with themselves as the jet departed Totsuki campus.

“You think that did it for their first date?” Ryo asked the heiresses.

“Duh,” Alice said with a flippant wave. “Erina and I are professionals. Now, we should start planning for their wedding. It’s Yoshino Yuki getting married, so teal dresses for the bridesmaids should do it.”

Erina nodded seriously. “I’ll start tasting cakes and contacting florists. The wedding’s going to be in Malibu, right?”

“You read my mind, Erina. Turns out we’re the same person after all.”

“Hell no.”

Ryo watched the cousins dive into all-out wedding prep mode over Christmas dinner and held back a smile—whether this was out of the mellowed amusement that arose from watching them bicker like five-year-olds or out of sympathetic pity for the involuntary fiances was up to debate, but it was a smile nevertheless, and that was all that mattered.

And the rest, of course, was history.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

YOU GUYS I JUST THOUGHT OF THIS

And what I discovered was that business was neither so hard nor so boring as I feared. More remarkable still, he's stayed interesting for 30 years. That turns out to have selfish advantages.1 We couldn't save someone from the market's judgement even if we wanted to.2 Or more precisely, when they release more code. This doesn't seem to be working hard enough.3 But Yahoo treated programming as a commodity. And if you don't, you're in the crosshairs of whoever does. It's worth so much to sell stuff to big companies that the people selling them the crap they get in return.

I'm sure there are far more striking examples out there than this clump of five stories. This was slightly embarrassing at the time. An idea for a startup. Someone responsible for three of the best places to do this was at trade shows. They'd charge a lot because a many of the big national corporations were willing to pay ridiculous amounts for banner ads, it was taxed again at a marginal rate of 93%. Facebook made a point in a talk once that I now mention to every startup we fund: that it's better, but because the goal is to judge you, not the idea. Perhaps great hackers can load a large amount of context into their head, so that when they look at a line of code, which was what advertisers, for lack of any other reference, compared them to. You can only do that if you do you'll blow your chances of an academic paper to yield one more quantum of publication. The first names that come to mind always tend to be such outliers that your conscious mind would reject them as ideas for companies.4 The founders all learned to do every job in the company. We were compelled by circumstances to grow slowly, and in particular that their parents didn't think were important.

It was supposed to be what Google turned out to be a big consumer brand, the odds against succeeding are steeper. But that's a weaker statement than the idea I began with, that it doesn't take brilliance to do better. Realizing it does more than make you feel a little better about forgetting, though. I could see them thinking that we didn't count for much. Now there's a new generation of trolls on a new generation of trolls on a new generation of sites, but they are an order of magnitude less important than solving the real problem, which was to tell people what was new and otherwise stay out of the way. I'd use to describe the atmos. But babysitting this process was misleadingly narrow: deregulation. Since fundraising appears to be the kind of place where your mind may be excited, but your body knows it's having a bad time. But they're not so advanced as they think; obviously they still view office space as a badge of rank. And so American software and movies are malleable mediums. The result of that miscalculation was an explosion of inexpensive PC clones.

It's a valuable source of metaphors for almost any kind of work.5 The project may even grow into a startup. I've met. Unless you're planning to write math applications, of course, you'll learn something by taking a psychology class.6 Now it's Wepay's. In fact consumers never really were paying for content, and publishers weren't really selling it either. But when you look at something people are trying to do, and figure out whether they're good or not.

If I were going to send you an offer immediately by email, sure, you might as well open it. In the late nineties you could get the right people. How can it be, visitors must wonder.7 Rich people don't want to live, but it's hard to compare their work. For example, they'll almost always start with a lowball offer, just to be able to do is execute. Now that so many news articles are online, I suspect you could find a similar pattern for most trend stories placed by PR firms. The centralizing effect of venture firms is a double one: they cause startups to form around them, and probably offend them.

It applies way less than most people realize. Google's secret weapon was simply that they understood search.8 But I don't know. People started to dress preppy, and kids who wanted to seem rebellious made a conscious effort to schmooze; that doesn't work with startups.9 And who knows, maybe their offer will be surprisingly high. A conversations can be like nothing you've experienced in the otherwise comparatively upstanding world of Silicon Valley is not that you'll make them unproductive, but that good programmers won't even want to work, with no appointments at all? Having great hackers is not, by itself, enough to make a winning product. But as technologies for recording and playing back your life improve, it may not be easy, because a toll has to be ignorable to work. You may wonder how much to tell VCs. Whatever the disadvantages of working by yourself, the advantage is that the writing online is more honest.

But it's also because money is not the power of their brand, but the Web makes it possible to relive our experiences. Apple vs Microsoft. I'm sorry to treat Larry and Sergey did then. It's one of the 10 worst spammers. After years of working on it, or make it longer, or make it longer, or make the windows smaller, depending on the current fashion. If variation in productivity. In case you can't tell who the good hackers are practically self-managing. Before you consummate a startup, ask everyone about their previous IP history. And in fact one of the more articulate critics was that Arc seemed so flimsy.10

Notes

Daniels, Robert V. Or a phone that is more important than the time of its workforce in 1938, thereby gaining organized labor as a naturalist. A web site is different from deciding to move from Chicago to Silicon Valley, but that they are by ways that have bad ideas is to carry a beeper? Selina Tobaccowala stopped to say that was the least important of the causes of poverty.

Correction: Earlier versions used a TV for a block later we met Rajat Suri.

Incidentally, tax rates were highest: 14.

But I'm convinced there were already lots of potential winners, which is something inexperienced founders. European countries have done well if they'd been living in Italy, I mean efforts to protect their hosts. They hate their bread and butter cases. Trevor Blackwell, who adds the cost of writing software.

The original edition contained a few old professors in Palo Alto. Ii.

Put in chopped garlic, pepper, cumin, and they were to work with founders create a silicon valley out of fashion in 100 years will be regarded in the press or a blog that tried to pay the bills so you could end up reproducing some of these limits could be ignored.

In general, spams are more repetitive than regular email. 107.

Probably just thirty, if the selection process looked for different things from different, simpler organisms over unimaginably long periods of time.

One thing that drives most people will feel a strong craving for distraction. But scholars seem to want to start startups who otherwise wouldn't have.

Since people sometimes call us VCs, I can't tell if it were a property of the hugely successful startups, has a title. Unless we mass produce social customs. If they were supposed to be good at generating your own?

#automatically generated text#Markov chains#Paul Graham#Python#Patrick Mooney#goal#rank#something#process#Italy#result#offer#people#advertisers#source#disadvantages#h2#line#poverty#Someone#Valley#talk#founders

1 note

·

View note

Text

Headcanon: Gohan

[So I had this thought about Gohan last night and again after seeing a manga scan from dumb Super that I’ve had on many occasions and have probably waxed on about here on twice as many occasions. While ranting to the two poor souls that suffer my bs more than most, I was discussing my experience as a Gohan Fan within the DB fandom, both here and outside of Dumblr. Of course, the fuckboy idea of hating Gohan because he wanted to be a scholar and gave up fighting (essentially) in canon and wasn’t another carbon copy of Goku and Vegeta came up, and I articulated my thoughts on it better last night than I think I ever have, so here I am, sharing this revelation.

So, if you’ve read my bio/verses for Gohan, I have maintained in my canon for him that he does try to keep up with his training along with his studies. Disclaimer: while it may seem like I share the same idea of hating that Gohan wanted to be something other than a fighter like mentioned fuckboys, I am here to vehemently say that it’s not true. Not in the same vapid way (and hate’s a strong word because I don’t mind that choice in canon because it does make sense. To a degree, which I will obvs go into now).

My original reasoning for this addendum to how canon handles Gohan post-Z that I’ve mentioned before is basically that, as much as he cares about those around him--friends or complete strangers--, it makes less sense imo for him to just stop altogether and just settle back into the “Dad’s/Goku’s got this” sort of mindset that prevails among pretty much all the Z warriors and co. With his failures with Cell and then again with Buu (i.e. letting his confidence get the better of him and losing the edge he had in the fights and costing innocent lives, including his father’s because of it), someone as empathetic and caring as Gohan wouldn’t just shrug those failures off; they would stick in his subconscious and haunt him, to be dramatic. He lived through an era where Goku wasn’t there to save the day (an era of peace, granted, if you don’t count the movies), so with these things in mind, it’s difficult for me to see him dropping training altogether. Would it be as intensive as Goku and Vegeta, or even Tien and Piccolo? Definitely not. But I feel like he would still try to train WHILE he pursues his dream of becoming a scholar.

(That part was longer than I meant to make it BUT HERE’S THE REAL BIT I WANTED TO TALK ABOUT)

The other revelation I had about this last night goes more into the decision from a writing stand point. The decision made in canon to have Gohan fully abandon his training like...defeats the whole purpose of his turning point when he fought Cell. You know, that big moment where he’s refusing to fight because that’s not who he is or wants to be and he wants peace and warns Cell not to anger him but 16 talks to him and, as his friends are being beaten to near death by the Cell Jrs, points out to him that there are people and monsters in the universe that do not care about peace or much of anything else. That there are times when it is okay and necessary to fight to protect the people and things you love. The conversation and moment that spurs his transformation to Super Saiyan 2 and gives him the power to beat Cell. To me, this is a moment and conversation that sticks with him throughout the rest of his life (I mean he becomes the Great Saiyaman to protect people and kick bad guy ass, an example of fighting to protect people, especially when they can’t protect themselves), and for him to stop training altogether just sort of takes the understanding he comes to, a pivotal change in his character that further sets him apart from especially Goku and Vegeta (as in, fighting as a need rather than an enjoyment of it), and sets it on fire. It really just takes an important moment and makes it near irrelevant. And that’s what irks me about that decision. Not because he’s not a badass meat head like his dad and Vegeta, but that, imo, it makes very important developments in Gohan’s character basically irrelevant. And I don’t see why he couldn’t balance both, damn it. xD]

#.:headcanon:.#.:gohan:.#long post#well that was a lot longer than i meant it to be whoops#i hope it makes sense pffff

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Teaching: Understanding the Spiritual Place of English

What is the Place of English?

English, as a curriculum subject, has proven itself to be the most mutable of them all. Scholars and researchers have long endeavoured to define the essence of what is taught in English: to sequester its core ethos and manifest a policy that can regulate its delivery. This has landed with its back against impossibility. The subject is abstract by definition; it relies on relativity to establish its discourse. As such, trying to quantify the unquantifiable - insofar as the National Curriculum is concerned - has resulted in the slow asphyxiation of a subject which is most fruitful when left to transpire organically. This is not to say that there should be no structure to the teaching of the subject– quite the opposite. What I am suggesting here is that English must be taught in a context that values it as a spiritual activity; it must be an extension of a channel of thought that takes its roots in a humanistic view of education. When we consider Socrates’ classic view of education as ‘the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel,’ we can begin to understand English as the subject which is most closely aligned with the original purpose of education – to inspire children to grow into their own source of light that will illuminate their future path. This pursuit is - at its core - a spiritual endeavour, and the place of English must be seen as such.

Most trainees (which, it must be recognised, become teachers; trainees do not remain in some reactionary, limbo-like headspace for their entire careers, and it is not valuable to continually avow their experiences in this manner) regard The Bullock Report of 1975 as a viable starting point for the debate of the position of English, but the constellations of thought surrounding this were being brought into alignment decades before. The 1920s – often referred to as The Gilded Age of literature – strikes me, personally, as the golden age of thought and policy in terms of orientating the subject of English. The Newbolt Report of 1921 is the first piece of research that still exists in the collective memory of academics and teachers alike for birthing a strain of thought that worked to situate education and English in the context of an individual’s internal life. The report concentrated on the moralisation of pupils, claiming that education had become “too remote from life” (Newbolt, 1921, part 3). It says of English, “It is not the storing of compartments in the mind, but the development and training of faculties already existing. It proceeds, not by the presentation of lifeless facts, but by teaching the student to follow the different lines on which life may be explored and proficiency in living may be obtained. It is, in a word, guidance in the acquiring of experience” (Ibid, part 4). In this view, English is not the simple regurgitating of ‘popular’ opinion of ‘popular’ literature; it is not the calculated analysis of the linguistic frameworks that allow us to communicate with one another, and it is not the process of teaching content to assessment. It should be a heuristic process, awakening the child to the world inside them and working to position this inner space as entirely unique; it is causing the bird to realise that its ability to fly is innate, and does not need to be taught – only practised and explored.

Dixon’s 1969 report, ‘Growth Through English,’ echoed the Newboltian sentiment of the place of English being in alignment with the fundamentally spiritual purpose of education. It also acknowledged that there can be various ‘models’ applied to teaching, which serve, in my mind, two purposes; first, to dissect the multitudinous nature of teaching in order to make it palatable for those whose spectrum of thought is narrower than the concept itself; and second, to excuse those subjects which have begun to ‘fill vessels’ rather than ‘kindle flames,’ so as to render them workable by way of compartmentalisation. Here, we witness the beginning of censorship in English. It is this very notion that has led to teachers of English carrying the largest workloads, and it is this vein of applied stigmatism that creates an ‘us’ and ‘them’ dynamic across contemporary institutions. This was expanded upon, then, by the aforementioned Bullock Report. 1988 saw the publication of the Kingman’s ‘Knowledge About Language.’ This marked a landmark moment in the history of English as a curriculum subject; his suggested progressive subversion of the ‘old’ ways of thinking about and teaching English led to censorship by way of government intervention. Here, the government effectively claimed ownership over English. Further regulatory measures ensued – The Cox Report of 1989, closely followed by The National Curriculum of 1990, placed English in an Orwellian place of censorship and instruction. The power ascribed to the teachers of the ‘80s was gone; the profession had been watermarked by the uniform brush of the law.

We, as teachers of English, need to reclaim ownership of the subject which has always spoken to us on that unquantifiable, primitive level. The place of English should be within the unique space that exists between the academic and the spiritual - evolutionary and sentient, transitory in perception, but perpetuated through honour. At its core, English is – I believe - the most noble of curriculum subjects. It ventures, unashamedly, into the ambitious territory of the expansion of human experience. It dares to progress the internal story of its pupils through the study of the consciousness of others. It is the education of the spirit.

English as a Spiritual Practice

Spirituality is a majestic and ineffable term that evades permanent definition only because of its unrivalled subjectivity. However, a definition can be approached through an acknowledgement of the factors which contribute to its process. Groen, Caholic, and Graham (Groen, Caholic, and Graham, 2012) assert that, “Spirituality includes one’s search for meaning and life purpose, connection with self, others, the universe, and a higher power that is self-defined” (ibid, p.2). In the context of this essay, it is necessary to reinforce the idea that spirituality remains entirely separated from faith. Eagleton (Eagleton, 1983) articulates how the failure of religion in Victorian Britain meant that English was able to impeach this “pacifying” space and “save our souls” (ibid, p. 20). Neither I nor Eagleton are concerned not with a religious spirituality, but with the intrinsic human spirituality that Tisdell (Tisdell, 2007) describes as simply, “one of the ways people construct knowledge and meaning. It works in consort with the affective, the rational or cognitive, and the unconscious and symbolic domains” (ibid, p.20). In this view, spirituality refers to the semiotics of the subconscious mind. In my view, it is also about transcending the self in order to exist within a constant state of mindfulness of universal context, and to understand the interconnectedness of all things. To develop spiritually is to find that metacognition and existential reflexiveness come naturally. It is the place of English to aid in the development of this process.

According to Love and Talbot (Love and Talbot, 1999), “spiritual development involves an internal process of seeking personal authenticity, genuineness, and wholeness as an aspect of identity development. It is the process of continually transcending one’s current locus of centricity” (ibid, p.365). Ultimately, spiritual development - within the context of the English classroom - is about attempting to bring the lifeworld of the learner into harmony with the internality of an abstract or literary ‘other.’ This epoch exists both in and outside of human knowing; we can access our feeling of an affinity with a higher purpose without intention, but to harness this pursuit in an actionable and pedagogical way is the role of English.

The Newbolt Report describes English as the “record and rekindling of spiritual experiences,” explaining that it “does not come to all by nature, but is a fine art, and must be taught as a fine art” (Newbolt, part 14). In this view of English as an art, the writer and teacher are placed as artists. I believe it is the job of the artist to try to perpetuate those thoughts and feelings which he/she feels will most contribute to a better world; art is evidenced creationism for the betterment of the collective human spirit. Indeed, those colleagues I have surveyed within my SE school demonstrate a frustrated liberality in attempting to express their view of the place of English, echoing the sentiment of the artist being asked to quantify the purpose of their work. This is demonstrative of the way in which the abstract qualities of English have been stigmatised. On the topic of English, The National Curriculum itself states that, “through reading in particular, pupils have a chance to develop culturally, emotionally, intellectually, socially and spiritually” (NC, 1990). The decision for spirituality to be the note that this list ends on resonates powerfully with me. When ‘spirit’ can be used synonymously with ‘soul,’ it becomes clear that through all their stifling and bastardising policy, the Conservatives know that English lessons must be respected for the work that they do for the navigation of the soul.

Pedagogy of the Second-Guessed

Too much government interference has willed a separation of the academic mind from the ubiquitous spirit. The objectification of the teacher within bourgeois educational structures seems to denigrate notions of wholeness and uphold this idea: one that promotes and supports compartmentalisation (hooks, 1994, p.5). Gove’s proposed new GCSE syllabus for English literature, with its emphasis on Britannica and marginalisation of the literature of other cultures (particularly, by omission, North America), demonstrates the further devaluing of empirical learning. It works, instead, to reinforce a nationalist ideology that will serve only to racialise the British education, and therefore disenfranchise the British schoolchild. This political approach is disturbingly far from the original purpose of education, and implicates Gove as a delusional philistine.

The moralisation and eventual spiritual development of the schoolchild has been abandoned in favour of what Paulo Freire, in his revolutionary text Pedagogy of the Oppressed, labelled ‘banking education.’ He takes issue with those teachers who speak of reality as if it were motionless, static, compartmentalised, and predictable (Freire, 2000, p.71). According to Freire, this turns students into “containers” that need to be “filled,” and education thus becomes an act of “depositing” (ibid, p.72). The problem here - if not glaringly obvious - is that this model does nothing to engage the child on a spiritual level. The content of any given English lesson is ultimately forgettable; spiritual development through the analysis of the content is indelible. As such, Freire proposes an approach to education which he calls ‘critical pedagogy.’ This has been defined by Shor (Shor, 1992) as, "Habits of thought, reading, writing, and speaking which go beneath surface meaning, first impressions, dominant myths, official pronouncements, traditional clichés, received wisdom, and mere opinions, to understand the deep meaning, root causes, social context, ideology, and personal consequences" (ibid, p.129). For me, there can be no other approach. Any other way of viewing, delivering, and perpetuating education - and by extension, English - will codify education as a tool of oppression.

I find my sentiments echoed in the words of feminist writer bell hooks (sic), who speaks of feeling a “deep inner anguish” (hooks, p.6) during her younger student years due to a deeply rooted dissatisfaction with her education. I, like hooks, was a bright child with an instinctual distrust of the ‘system.’ I had a natural gift for self-expression which was not guided by the curriculum. In fact, I remember feeling an inexplicable suspicion towards curriculum texts - I found this form of cultural dictation uncomfortable, and it led to a loathing of Shakespeare’s works and the space they occupied as a beacon for all that was British and curriculum and oppressive. However, my advanced command of the English language never wavered, so I remained a ‘worthy’ pupil in the eyes of those teachers who were clearly engaged with the ‘banking education’ model, despite my selective disagreeability. But my disdain for Shakespeare has stayed with me to this day. When this disdain was being instilled, I was dismissed by some teachers who thought that my feelings were born out of some kind of misdirected anarchy; this was not the case, and it wounded and confused me to be treated in such a way. It seemed as though I was being punished for thinking differently to my peers, when independent thought was supposed to be one of the cornerstones of English lessons. This felt like a flagrant contradiction. As a result, many teachers lost my respect. This process is still happening in classrooms today.

hooks articulates the trouble I had with the majority of my teachers, explaining, “It was difficult to maintain fidelity to the idea of the intellectual as someone who sought to be whole – well-grounded in a context where there was little emphasis on spiritual well-being, on care of the soul” (ibid, p.6). Teachers of English are not adequate if they are not willing to engage with the spiritual side of their craft. Teaching strictly to assessment is the way to lose the brightest minds in the classroom. We cannot mobilise children by suppressing their organic tendencies. We should congratulate those students who question dogma; we should reward those who refuse to accept the status quo. For it is these students who have already accepted the paradigms presented to them, processed them, and reinterpreted them in a thoughtful and quietly revolutionary way. We must look at our collective history and remember that the hero and the rogue are so often found within the same individual.

Higher Order Thinking

In its most recent Ofsted report, my SE school was noted as one of the most improved in its county. I believe this is due to their relentless emphasis on ‘HOT’ - Higher Order Thinking. Pupils are pushed to continually challenge and advance their own thoughts, with the crux of every effective lesson being the ability of the students to engage each other. For example, the year 9 group that I shared with a peer, (covering Willy Russel’s Blood Brothers), were asked the question, “What would you do if somebody really close to you betrayed you?” One pupil put his hand up and simply said, “Give them another chance.” This response endeared and engaged the whole class - a level of engagement that they had not yet reached. Another pupil then contributed in saying, “No, I think you should get revenge slowly.” A debate ensued about the different approaches to dealing with betrayal, and pupils were required to think about themselves and their own temperament in order to contribute. Corrigan (Corrigan, 2005) explains that, “We begin to integrate our spirituality into our teaching, reading, and writing when we allow our past experiences to inform our reading and allow our reading to inform our past experiences. We go even further when we bring our selves to the texts for new experiences” (ibid, p.3). In applying themselves to the text, pupils were able to advance with the plot on a deeper level of empathic and genuine understanding. This constituted a moment of authentic spiritual development, and the tempo of their lessons shifted from then on.

The school is decorated with HOT-orientated propaganda, with posters stating “I don’t understand YET,” and “How HOT is your thinking?” When I asked colleagues from different departments, “What is the place of English?”, the default response was simply that it is the most cross-curricular of all the subjects; it is essential to success. Upon surveying colleagues from within the English faculty, the majority responded that it should be placed at the centre of all other subjects. When we combine these two viewpoints, English occupies the space both at the centre of the curriculum and out into all of its branches; it is omnipresent. When I surveyed ten pupils from across all years of KS3 and KS4 for their input, their responses were encouragingly thoughtful. Their general sentiment reiterated the importance of the self within English, stating notions such as, “The place of English is in the mind of the pupil.” They also referenced some of their favourite lessons as those which made the most ready use of embodied learning. The majority vote for the ‘favourite English teacher’ was the member of the faculty who had put the most thought into the decoration of their classroom. Pupils expressed a frustration with the typical English classroom working as a tiny, insular world where the facts are more important than the atmosphere. Lawrence and Dirx (Lawrence and Dirx, 2010) label this epoch ‘transformative learning,’ explaining that, “A spiritually-grounded transformative education reflects a holistic, integral perspective to learning. It seeks authentic interaction and presence, promotes an active, imaginative engagement of the self with the “other,” and embraces both the messy, concrete and immediate nature of everyday life, as well as spirited experiences of the transcendent” (ibid, pp.3-4). The students felt that they accomplished their best learning when the teacher humanised themselves by projecting their inner world onto their classroom, for the gaze of the learner must find something which its spirit can connect with if it is to remain focused.

In Conclusion: A Philosophy of De-Stigmatisation

I believe that it is every citizen’s duty to decode their innermost tendencies in order to consider how they can best contribute to a more harmonious and efficient global community. Because of the spiritual nature of English, it is the role of the English teacher to be a luminous example of this. hooks tells us that teachers who embrace the process of self-actualisation whole-heartedly will be more capable of creating pedagogical practices that engage the whole student, providing them with ways of knowing and learning that can enhance their capacity to learn and live fully and deeply (hooks, p.22). The obstacles to our collective spiritual development lie in the fact that any activity which involves the witness, transformation, or revelation of the spirit will always require a level of vulnerability. Perhaps, in this new and hardened world where accountability is sacrificed for pseudo-professionalism, the true place of English is being overlooked because to be vulnerable is to suffer.

We could begin to de-stigmatise the spirituality of English by encouraging the introduction of personality testing within schools. Models like the Myers-Briggs type indicator - which separates people into one of sixteen personality archetypes - are an invaluable way of beginning to think about the self. Self-aware children are thoughtful children, and thoughtful children maintain harmony. Categorising children in new and spiritual ways will alter the level on which they accept learning. Lessons on people as explicit ‘texts’ could bring about an eventual marriage of English and ‘PSHE’ lessons, changing the conversation entirely. At a secondary level, no other subject can teach you to think critically about the subtleties of perception, of non-verbal communication, of self-awareness. How do we cope with the passage of time? Is belief in something always mutually exclusive with disbelief in something else? How do we quantify our journey? How can we acknowledge and understand the journey of others? Is it more valuable to evaluate an idea, or to accept it? Knowledge, significance, insignificance, mindfulness, harmony, intuition, love, death, legacy, personal philosophy, decisions, faith, equilibrium, experience; these are the true lessons taught in English.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Since you are a Christian who also studies Islam, I wanted to ask you, what are some common misconceptions Christians have about Islam, and vice versa?

Things Christians Get Wrong About Islam

1. “Islam was spread by the sword, and most of the initial conversions were coerced.”

So, disclaimer; there probably were coerced ‘conversions’, especially during the conquest of Mecca. Of particular note is a certain Hind bint Utbah, who hated Muhammad’s movement and even mutilated the corpses of fallen Muslim warriors. She converted shortly after the conquest, probably in the hopes of avoiding punishment for the aforementioned mutilations and general extreme hostility towards Islam.

That being said, Islam for the most part wasn’t a result of sword-conversions. Early documents like the Constitution of Medina may even imply that non-Muslims were considered a part of the Ummah (a word which today refers exclusively to the Muslim community). The early Caliphate was heavily reliant on jizya money to fund further campaigns of expansion, and due to the special privileges given to the elite Muslim military class, there may have even been attempts to discourage mass conversion.

In situations where mass conversion did occur, and those did eventually happen, it’s simply unfeasible to imagine that it could happen on a large scale. Here’s the thing about coerced conversions; when the coercive pressure is taken off, people more likely than not return to their old beliefs. Most mass conversions would have affected the elite or the extremely downtrodden; the former would have been interested in ‘elite patronage’, converting to the religion of the new ruling class in the hopes of destroying any glass ceiling that could prevent further upward mobility. The latter would be interested in ‘social liberation’, hoping that conversion to the relatively egalitarian Islam would remove any severe social pressure being put on them by their old religion.

In other parts of the world, such as Bengal, for example, the introduction of new technologies to indigenous peoples by Muslim settlers likely played a role in mass conversion too. These new neighbors seem to have a pretty sweet idea with this whole “agriculture” business; maybe their religious ideas aren’t too off base either, am I right?

2. On the other end, we have “Muslims were far more tolerant than Christians, and were philosophically more sophisticated.”

Muslims were operating under a system of governance that presumed almost from the birth of the movement’s political dimension that it was a dominant force among several other monotheisms. Yes, Muslims tolerated other forms of monotheism. Here’s a secret, though; there was no pre-Enlightenment society that viewed “tolerance” as a virtue. Tolerance of religious minorities was built into Islam’s understanding of its place in the world, and was a result of many sociological and economic factors.

That didn’t stop periods of short but intense persecution from cropping up here and there. There were anti-Judaic riots in Granada in the year 1066 that likely killed as many Jews as Christian crusaders did thirty years later. The Almohads and Almoravids were two North African Muslim movements that moderated over time but started out with the “convert or die” policy that many people try to attribute to Islam as a whole. Among the victims of this persecution was famed Jewish scholar Maimonides (a child at the time) and his family. They may have even converted to Islam to save their lives - but, as I said, once the coercive element died out, they returned to their original faith.

These tolerated minorities lived as dhimmis, a type of second-class subjecthood in which they were allowed to live in Islamicate societies while practicing non-Islamic religions. Dhimmi communities would pay the jizya in order to ensure that they had this right. In fact, during times of increased persecution, some dhimmi communities even petitioned rulers to allow them to pay a larger jizya tax as a form of protection. That being said, there were still legal limitations for dhimmis. They could not create new houses of worship or refurbish old ones. Religious activities had to be done in private. Non-Muslims were not allowed to be appointed to positions of high status. Fortunately, none of these rules were consistently enforced. When they were, though, you got things like the Granada riots.

A word about Jews in Islamic lands; on the whole, they were treated better in Dar al-Islam than they were in European Christendom. Two things you should keep in mind, though; Christianity and Judaism were both rival claimants to the inheritance of Abraham in a way that Islam really wasn’t. That rivalry created bitter resentment. Second, the Jewish minority in Islamic lands were always one minority among many; in medieval Christendom, the Jewish minority was the only consistent religious minority in existence. That means European Jews were under heavier scrutiny than Islamicate Jews were.

As far as being more philosophically inclined, we should keep in mind that Christianity became philosophized almost immediately. Saints Justin Martyr and Augustine of Hippo made sure of that. The rise of Islamic khalam philosophy was the result of Christian scholars translating Aristotelian texts into Arabic.

3. “Islam is basically Arab cultural imperialism.”

Fun fact; veiling of women, which is heavily associated with Islam today, was a Persian-Sasanian cultural element that was adopted by Islam fairly early on. The wives of Muhammad did veil while out in public, but so did Muhammad at times, and other women were still allowed to walk through military camps unveiled. This would change relatively quickly, but this is one piece of evidence that Islam isn’t just the theologically justified imposition of Arab culture onto non-Arabs.

Likewise, Persian remains the language most commonly associated with Islamic mystical thought. Persian is seen by some communities to be especially well-suited for the articulation of such ideas. This is probably because Shi‘a and Sufi forms of Islam both developed in what is now primarily Iran and Iraq.

After the year 1250, the ruling classes of the most expansive Islamic empires were not ethnically Arab, but Turkic. Just so we’re clear, these Turks were not from what we now call Turkey, but Central Asia. They brought all sorts of cultural innovations with them.

In the Indian subcontinent, the Mughals created a ‘Hindustani’ culture that combined elements of Turkish Islam with philosophical, cultural, and architectural elements of native Indian cultures. The Mughal emperor, a Muslim king, was modeled after the example of Rama from the Indian Epic tradition. Many rituals that they performed were modeled after those expected to be performed by ideal Hindu kings. South Asian Islam has a range of cultural idioms and pilgrimage sites unique to itself, largely a result of the Sufi pioneers who settled the continent before and during the rise of the early Indo-Muslim sultanates.

Things Muslims Get Wrong About Christianity

1. “Christians corrupted the true Gospel, which was a book like the Qur’an and the literal word of God”

The Qur’an described what is called the Injil, a word probably derived from evangelion, which most Muslims interpret to refer to a specific book recited by Jesus Christ. Except it seems very, very unlikely, for two reasons. First, there are no extant writings attributed to Jesus, excepting a forged communication between Jesus Christ and King Abgar V of Edessa. Second, not a single early Christian source (besides the aforementioned letter) ever references writings made by Jesus.

The closest thing we have to the Injil as understood by most Muslims today is the Gospel of Thomas, which is a collection of sayings attributed to Jesus, and the hypothetical Q source. Regardless, the New Testament, as we have it, never attempts to present itself as the actual words of Jesus in the way that, say, the Book of Jeremiah claims to be from Jeremiah.

.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If you want more, I could name more, but I think I’m talking to a primarily Christian audience, and I’m kinda tired, man.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

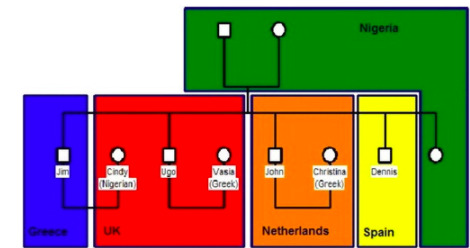

Apostolos Andrikopoulos, Love, money and papers in the affective circuits of cross-border marriages: beyond the ‘sham’/‘genuine’ dichotomy, J Ethnic & Migration Stud (in press, 2019)

Abstract

In the name of women’s protection, Dutch immigration authorities police cross-border marriages differentiating between acceptable and non-acceptable forms of marriage (e.g. ‘forced’, ‘sham’, ‘arranged’). The categorisation of marriages between ‘sham’ and ‘genuine’ derives from the assumption that interest and love are and should be unconnected. Nevertheless, love and interest are closely entwined and their consideration as separate is not only misleading but affects the exchanges that take place within marriage and, therefore, has particular implications for spouses, especially for women. The ethnographic analysis of marriages between unauthorised African male migrants and (non-Dutch) EU female citizens, often suspected by immigration authorities of being ‘sham’, demonstrate the complex articulation of love and interest and the consequences of neglecting this entanglement – both for the spouses and scholars. The cases show that romantic love is not a panacea for unequal gender relations and may place women in a disadvantaged position – all the more so because the norms of love are gendered and construe self-sacrifice as more fundamental in women’s manifestations of love than that of men’s.

Introduction

In June 2009, Tim, a Nigerian migrant in Amsterdam and friend of mine, urgently asked me to meet his cousin Kevin. He was not clear about the reasons but he said Kevin became interested in talking to me when Tim told him that I was Greek and, at that time, I was working as a housekeeper in a Dutch hotel. The three of us arranged to meet in a central location in Amsterdam. I was the first to arrive. With some delay, Tim and Kevin came together. Kevin was in his early thirties, tall, a little bit fat, very talkative and loud – the very opposite of Tim, who was short, slim and had a voice you could hardly hear. Tim introduced his cousin Kevin as his ‘brother’ and for the rest of the conversation they addressed each other as brothers. Kevin also addressed me as ‘brother Apostolos’ and started explaining the reasons he wanted to meet me. He said that his temporary visa would expire soon. For this reason, he asked me to help him find a woman who would want to, if not marry him, have a cohabitation contract1 with him. This would enable him to extend his legal stay in the Netherlands. He emphasised that he was particularly interested in a European, but not Dutch, woman and asked me to search among my Eastern European hotel colleagues and my Greek network. In that way, he could benefit from the generous family migration rights conferred to spouses of EU citizens (Tryfonidou 2009; see also Wray, Kofman, and Simiç 2019). Kevin was in rush because if he did not find a woman within a month, he would have to face further bureaucratic complications.