#riparian habitat

Photo

Lower Alpine meadow and a group of small ponds teaming with trout. Pinnacles Lakes Basin, John Muir Wilderness, Sierra Nevada Mountains, California, USA Photo by Van Miller

#Alpine Meadows#lakes#riparian habitat#geology#flora#alpine flora#mountains#pinnacles lakes basin#john muir wilderness#Sierra Nevada Mountains#backpacking#hiking#california#©Van Miller#photography#travel#Wanderlust#Wilderness#the wilderness journals

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Trail by the saltmarsh

#rb if you love riparian habitats 💚#mother nature#my photography#salt marsh#brackish#estuary#riparian#water#places#nature trail

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

girl lying in her bed sighing eyelashes fluttering drawing hearts in a notebook with a glitter gel pen but when you look in the notebook it just says "Arundinaria gigantea" north america's native species of bamboo that once formed miles-wide riparian thicket habitats called canebrakes

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Headline by: Ryan Burns. “Ground Has Been Broken on Klamath River Restoration, the World’s Largest-Ever Dam-Removal Project.” Lost Coast Outpost. 23 March 2023.

---

The world’s largest dam removal in history is slated for 2023. Led by Indigenous tribes in partnership with organizations, lawyers, scientists and activists, the project will remove four dams, clearing the way for the lower Klamath River to flow freely for the first time in more than a century.

Headline and italicized text excerpt by: Malia Russ. “The Science of Saving Salmon as Klamath Dams Come Down.” UC Davis - Blogs - Climate. 24 February 2023.

---

Headline by: Jackson Guilfoil. “Klamath dam removals, habitat restoration, begins.” The Mercury News. 25 March 2023.

---

Headline by: Kale Williams. “‘The salmon are coming home’: Work begins on Klamath River dam removal.” KGW8. 27 March 2023.

---

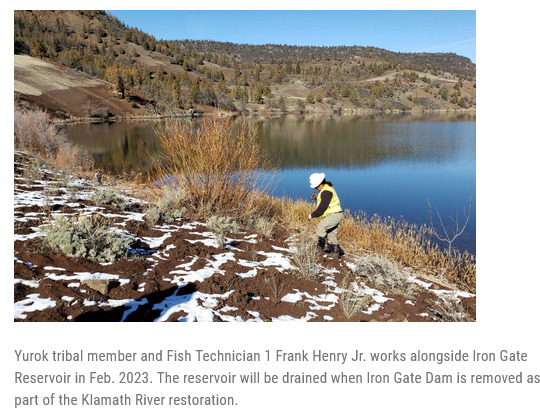

Iron Gate is a sinuous, skinny reservoir tucked into the folds of the Siskiyou Mountains. Draining it will expose about 900 acres of wet mud. “It’s our job to make sure it’s revegetated. We want that to be revegetated with a healthy native plant ecosystem,” says Joshua Chenoweth, Senior Riparian Ecologist for the Yurok Tribe who is leading the replanting effort. [...] Last fall, they seeded the strip with a mix of native grasses and flowering plants; now, they’re installing young shrubs and trees: buckbrush, serviceberry, and Oregon ash, along with the Klamath plum. Collectively, these plants will create a “wall of green,” taking up space that would have otherwise been overrun by non-native plants [...]. The revegetation of the Klamath River has been called the largest river restoration project in American history. Collecting, propagating, and growing enough seeds and plants to populate the reservoir footprints -- approximately 2,200 acres in all -- is a staggering task. [...] Their planting design includes 96 different species: culturally significant plants like yampah and lomatium, important pollinator species like milkweed, and tens of thousands of oak trees. [...] What will a restored, wild Klamath River look like? Imagine it. Stand at the Wanaka Springs boat launch and picture Iron Gate reservoir drained. The river has found its channel at the base of its original canyon. Willows flank the banks. Much of the reservoir footprint is flush with upland vegetation -- oak copses; thickets of buckbrush and Klamath plum; blooming rose and lupine.

---

Headline, images, captions, screenshot, and italicized text excerpt from: Juliet Grable. “After the dams: Restoring the Klamath River will take billions of native seeds.” Jefferson Public Radio. 13 March 2023.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Lauren Diaz

The Appalachian mountains share their story with us in many forms, beginning from their wise and weathered peaks, through their towering forests, and down to the rushing roar of their rocky streams and rivers. Many of these clear, mountain rivers are inhabited by the cryptic and awe-inspiring Eastern Hellbender. Truly a living fossil, the hellbender has existed for millennia and yet sadly it has been quickly disappearing over the last century. The Hellbender is a lonely species; it is the only giant salamander in the western hemisphere, as its cousins live in China and Japan. An ancient creature that is hardy enough to withstand thousands of years of flooding and drought, Hellbenders were once abundant even in the mainstem of the Ohio river. Unfortunately, they are now being lost at an unprecedented rate, and for many reasons we don’t understand.

Although many factors implicated in the Eastern Hellbender’s rapid decline are large scale — urbanization, removal of riparian tree cover, siltation, and pollution — there is one simple issue that every one of us that recreates in the Appalachians has control over: the moving of rocks in these streams to create dams, chutes, and rock statues (also known as cairns). The rivers where we still have healthy hellbender populations, such as those within the Pisgah National Forest and Great Smoky Mountains National Park, are the same rivers that are receiving an extraordinary rise in human use. While the hellbenders are holding on for now, the very real possibility of loving these rivers to death is just around the corner.

The Hellbender relies on the spaces under river rocks for their homes and to find their favorite food: crayfish. They share these spaces with the stoneflies and caddisflies that feed the iconic rainbow trout, as well as a variety of other small fish, mussels, and salamanders. Most importantly, they require cavities under large boulders to breed. Hellbenders lay their eggs under these large boulders in early fall, and then the male Hellbender will stay in that cavity protecting the eggs and larvae until they emerge in late spring. Moving rocks around in streams disturbs the delicate homes and breeding grounds of these enigmatic mountain species.

Cairns are a recent phenomenon, and their ubiquitous presence in national park and forest rivers is undoubtedly tied with the rise of social media. You have surely seen a picture of one, probably accompanied with a quote about balance. You may think, “there’s no harm in making small ones if they only use boulders!”, but in fact small rocks are important habitat for larval and juvenile Hellbenders. Plus, just seeing one cairn in a river (even with tiny rocks) encourages others to make them too, despite nearby signs asking visitors not to move the rocks. Dams and tube chutes not only make large boulders unavailable to Hellbenders, but they also slow down water flow and essentially make pools of dead habitat. This slow, silty water can no longer support the needs of the unique species that require swift, cool, well-oxygenated water. Silt accumulates in the pools above and below rock dams, and that silt fills in the spaces that hellbenders need to live and reproduce. Moving boulders for any of these uses has the potential to crush any animals living underneath them, including hellbenders.

The motivations behind moving rocks are innocent. But the consequences for the rare species that rely on a very specific kind of stream substrate are damaging and permanent. Some hellbenders will spend their entire lives (up to 30 years!) living under one rock. We ask that when recreating in hellbender habitat, please keep in mind that you are a guest in their home. Respect the forces of nature that put each stone in its perfect place and the millions of years of evolution shaping these stream systems so that every insect, fish, and salamander can live in perfect harmony.

For more information on hellbenders, check out these resources on the article page.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Until recently, a visit to the Colorado River’s delta, below Morelos Dam, would be met with a mostly dry barren desert sprinkled with salt cedar and other undesirable invasive plant species. Today, that arid landscape is broken up with large areas of healthy riparian habitat filled with cottonwood, willow, and mesquite trees. These are restoration sites which are stewarded through binational agreements between the United States and Mexico, and implemented by Raise the River—a coalition of NGOs including Audubon"

Thanks to @aersidhe for sending this in!

#submission#bird conservation#river conservation#wildlife#biodiversity#conservation#environment#good news#hope#ecosystem#habitat#habitat restoration#river restoration#climate change#global warming

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

North America once housed more beavers than humans — by a lot. Even before Europeans showed up and built an entire extractive economy on beaver pelts, estimates put the number in the hundreds of millions (during the Pleistocene, there were even giant species of beaver, as large as bears). The North American fur trade, which lasted for centuries, nearly wiped beavers off the continent — and, unknown to trappers, vastly changed its ecosystems from sea to sea.

“There is evidence that riverscapes across the West were much more complex and ‘anastomosed’ prior to European colonization,” says Nicholas Kolarik, a Ph.D. student working with Brandt, who is focusing on mapping data sets of wetlands. Anastomosis denotes branches connecting two things, like organs in the body, but in this case, he means streams, since waterways in the U.S. West used to be much more interconnected.

Today, they’re “starved of wood,” he says, but by adding wood into streams and rivers, especially by building dams, beavers slow water down significantly.

“In doing so, sediment is stored, water infiltrates into the aquifers, riparian vegetation establishes, habitat is created, and carbon is stored,” Kolarik says.

[...]

“Beavers maintain healthy riverscapes which store carbon and water. Consistent access to water is key to mitigating the effects of climate disturbances like drought.”

Beavers’ role as firefighters has already been documented in Idaho. A 2018 technical report by Anabranch Solutions, a river restoration company, found that beavers were a major factor in decreasing burn intensity along Baugh Creek during that year’s Sharps Fire.

“Where active beaver dams were present, native riparian vegetation persisted, unburnt,” the authors wrote. In our hotter and fierier world, beavers are a buffer.

435 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was so, so lucky to meet a very special trio of snakes for a class I'm taking on methods in field ecology. One of my two professors is a specialist in garter snakes and was kind enough to bring three different species in for us to compare in person and observe up close. The first was the gorgeous common garter snake, Thamnophis sirtalis, pictures above. She was so calm and well-mannered!

Next was this tiny (by comparison) T. elegans dude, a western garter snake, who was wary of the camera but very patient about being passed around by a group of excited college students. He matched my classmate's sweater perfectly!

Finally, an endangered and incredibly precious T. gigas, the giant garter snake. She's about half of her maximum adult size, so a giant indeed! She musked and peed a bit but for the most part this gojira-faced beauty was pretty chill. We got to observe a full work-up for her including documenting records and microchipping.

She's one of the last of her species. Despite Herculean efforts by her protectors and conservation experts (mostly just one man and his dedicated team), this is a very difficult species to observe in the wild and their habitats are disappearing faster than their need for prioritization of protection in a given area can be assessed. These snakes rely on riparian habitat near rivers, which is also unfortunately a favorite for human development. At this time we don't know how exactly many giant garter snakes are left or whether their current populations are stable.

Today we got to visit their marshland habitat and watch these three go back to the place where they were caught. It was a huge honor and something I'll carry with me forever.

#snake#snakes#reptile#reptiles#reptiblr#garter snakes#garter snake#native species#we put that thing back where it came from or so help me#so help me!#science#ecology#endangered species#giant garter snake#western garter snake#common garter snake#when i got home i ate a salad so big that it made me sleepy

466 notes

·

View notes

Text

The King of All Birds

The Eurasian wren, also known as the northern wren or the winter wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) is found throughout Asia, most of Europe, and northern Africa; it has also been introduced into parts of North America. This bird can thrive in a variety of habitats, but prefer deciduous or coniferous forests with plenty of bushes and leaf cover.

The northern wren is on the small side, only 9 to 10 cm (3.5 to 3.9 in) long with a wingspan of 13–17 cm (5.1–6.7 in), and weighing at most about 10 g (0.35 oz). It is brown all over; darker on top, and mottled tan on the underside, wings, and tail. Males and females are nearly identical, but in the breeding season they can be distinguished by a brood patch on the females or a swollen cloaca in the males. T. troglodytes has several calls and songs, the most common of which is a "tic-tic-tic" sound.

Breeding season throughout Europe and Asia is in the spring and summer, from March to August. Males maintain a territory, reinforcing its boundaries with complex songs and building several nests to draw in females. When a female arrives, he gives her a tour of his territory and, if she's impressed, she allows him to mate. After this, she lays 5-7 eggs in one of the males' nests and proceeds to incubate them while he provides food. At about 15 days, the eggs hatch. Generally the young are cared for by the female, while the male seeks out another mate, but some monogamous males will stay with the nest until the chicks have fledged at about 16 days old. Winter wrens only live about 2 years old in the wild, though some individuals may live as long as 4 years.

The eurasian wren is active primarily during the day, and when not defending their territories or seeking out mates, they are foraging for insects. Their primary prey are moths, butterflies, millipedes, and larvae-- and, in riparian areas, aquatic invertebrates. Birds of prey like northern harriers are the primary predators of T. troglodytes adults, while nests are targets for crows, jays, and weasels.

Conservation status: Due to its large range and population size, the Eurasian wren is considered Least Concern by the IUCN. In fact, studies and monitoring programs indicate that the number of winter wrens is increasing.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a kofi!

Photos

Ashley Bradford

Andy Wilson

Steve Garvie

Andreas Eichler

#eurasian wren#Passeriformes#Troglodytidae#wrens#perching birds#birds#deciduous forest birds#evergreen forest birds#generalist fauna#generalist birds#europe#asia#eastern asia#africa#north africa

164 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Piute Creek, Hutchinson Meadow, John Muir Wilderness, Sierra Nevada Mountains, California, USA Photo by Van Miller

#Piute Creek#Piute Canyon#Hutchinson Meadow#john muir wilderness#Sierra Nevada Mountains#california#©Van Miller#hiking#backpacking#camping#geology#Wild Rivers#riparian habitat#photography#travel#Wanderlust#Wilderness#the wilderness journals

121 notes

·

View notes

Note

are mustangs a native or invasive species? do you think they should be rounded up?

I think it would be overly conclusory to say either at this point. As far as I know, there haven't been any radio carboned equine remains that show they survived through the ice age in North America. There is some evidence that shows they survived later than what was originally thought though, and were also in the West before the Pueblo Rebellion, which was when many white people thought they were introduced there.

But if they are not native, it would be a mistake to automatically conclude that they are invasive because there is also a lot of new evidence that shows that they are ecosystem engineers. "Invasive" implies a species that causes ecological harm to a new area, but several studies done on wild horses and burros in the Western US show some positive impacts. The ones that I know of are:

Equids engineer desert water availability - this study was done in the Sonoran desert in AZ and showed that equine dug wells increased biodiversity in the surrounding areas by 64%, and often were the only water sources. The researchers concluded "that equids, even those that are introduced or feral, are able to buffer water availability, which may increase resilience to ongoing human-caused aridification.”

Impact Of Wild Horses On Wilderness Landscape And Wildfire - this was done in Northern California to push back on claims made by the BLM that wild horses had a negative impact on the ecosystem and had no predators. It found that horses degraded land less than some of the even-toed ungulates because their hooves are not sharp and pointed like theirs. The riparian ecosystems in the area of study were not permanently damaged by horses because predators prevented them from staying long, and their predators included coyotes, mountain lions, and bears for foals, and bears and mountain lions for adults. Additionally, by eating dry grass the horses reduced the fuel load in the area, and likely prevented a branch that fell and ignited after being hit by lightening from causing a wildfire.

A roundup in the Ash Meadows Reserve in Nevada caused a population of critically endangered pupfish to go extinct - this was cited by the first study mentioned. Once the equines were removed from the area, the riparian habitat became choked by vegetation, a whole population of pupfish died as a result.

To me what these studies suggest is that native or not, the mustangs and burros are filling a distinct role that was not taken on by another native species if their ancestors did go extinct. I don't think the BLM has properly taken this into account in their Appropriate Management Level assessments, though courts tend to give them so much deference as a federal agency that I don't think any have found that they actually violated National Environmental Policy Act. Under NEPA, the BLM is supposed to consider all reasonable alternatives when making environmental impact statement and assessment proposals. I think these studies show that livestock reduction and predator re-introduction should be considered as reasonable alternatives before roundups given the immense cost of roundups and lack of permanent improvement of the range after them, but the BLM has given reasons not to try these options such as "the horses don't have predators in this area" or " it doesn't conform to the current multiple use land management plans." The courts usually accept these reasons as valid. See Friends of Animals v. Silvey.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Image 1 : Southern river otter - Lontra provocax

Fun fact: Southern river otters live in freshwater with riparian vegetation. Riparian vegetation protects the water from hot summers and cold winters, shielding the waters so that the aquatic life living there won't become distressed.=(^.^)=

Image 2 : Asian small-clawed otter - Amblonyx cinereus

Fun Fact: asian small-clawed otters are the smallest of all other otter species. They also have whiskers called vibrissae that detects movement of prey in the water. ( ^w^)

Image 3 : Marine otter - Lontra Felina

Fun Fact: Marine otters are the only species with the genus Lontra that is found in marine habitats. Sometimes they even eat fruits! (╹◡╹)

September 19 , 2023(*^o^*)

@meowzerswhirlingsomewhere

#marine biology#ocean#rivers#fun facts#meow#marine science#scientific names#endangered species#aqua life#aquaculture#otters#sea otter#river otter#asian small clawed otter

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rod Hendrick :

Kayaking In The Woods

Willow Lake riparian habitat Prescott

Arizona

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Because bats drink while in flight, they must have pooled or slow-moving water to get a drink,” says BCI Restoration Team Lead Ethan Sandoval. “Their ability to use these pooled water resources is determined by each species’ flight maneuverability, as well as the size and length of a pool and the flyway surrounding it. A stretch of riparian habitat with long, reliable pools is where you see the most bat activity.”

Sandoval and his team are currently working on projects to restore water sources and riparian habitat for bats and other wildlife in Arizona, Idaho, New Mexico, Oregon, and Utah. The team partners with state and federal agencies, other non-profits, private landowners, and local communities. They seek to target resources close to known bat roosts, using years of roost survey data assembled by BCI’s Subterranean Team in collaboration with abandoned mine and cave managers.

360 notes

·

View notes

Text

Warbler Showdown; Bracket 8, Poll 3

Northern Waterthrush (Parkesia noveboracensis)

IUCN Rating: Least Concern

Range: migratory; breeds from Alaska all the way to Newfoundland, with some populations dipping into Montana and the Northeast states. Overwinters in the Greater Antilles, and from southern Mexico to Colombia and Venezuela.

Habitat: breeds in areas of dense ground cover where surface water is present, such as bogs, wooded swamps, and riparian thickets. Overwinters in similar habitats, but can also be found heavily associated in mangroves.

Subspecies: none

Louisiana Waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla)

IUCN Rating: Least Concern

Range: migratory; from the Northeast states down the Appalachian mountains and into the Southeast, as well as the Mississippi river drainage from Missouri down to Texas; overwinters in the Greater Antilles, as well as Mexico down through the very top of Colombia.

Habitat: found most consistently around streams, preferring those in close-canopy, hilly, deciduous or mixed-evergreen forests, both during breeding and overwintering seasons.

Subspecies: none

Image Sources: Northern (Kyle Blaney) Louisiana (Malcolm Kurtz)

#NWW Showdown#northern waterthrush#louisiana waterthrush#parkesia#parulidae#passeriformes#polls#bird poll#animal poll

18 notes

·

View notes