#river reptiles

Text

The Stupendous Alligator Snapping Turtle

Alligator snapping turtles (Macrochelys temminkii) are one of three recognised species of snapping turtle, all of which are found in North America. This particular species is found in the southeastern United States and the Mississippi Basin in particular. Macrochelys temminkii prefers deep freshwater, and is especially common in deep rivers, wetlands, and lakes.

The alligator snapping turtle is the largest freshwater turtle in North America, and is one of the heaviest in the world. Most individuals weigh between 70-80 kg (154-176 lbs), and are about 79-101 cm (31-39 in) long. However, the largest verified indiviual weighed over 113 kg (249 lb), and many others have been recorded in excess of 100 kg. The species is easily identifiable by its large, boxy head and thick shell with three rows of raised spikes. Typical alligator snapping urtles are solid black, brown, or olive green, though the shells of many older individuals can be covered in green algae.

M. temminkii is famous for its strong bite, which is most often utilised when feeding. The turtle's tongue resembles a worm, and at night individuals lie on the bottom of the river or lake bed with their mouths open. Fish are enticed by the bait-tongue, and when they get close enough the alligator snapping turtle's mouth clamps down around them. In addition to fish, this species may also feed on amphibians, invertebrates, small mammals, water birds, other turtles, and even juvenile alligators where their territories overlap. The alligator snapping turtle's relies on ambush techniques, and so hunters can remain submerged for up to 40 minutes. In some cases, individuals can also 'taste' the water to detect neaby mud and musk turtles. Because of this species' thick shell and ferocious bite, adults have few predators, but eggs and hatchlings may fall prey to raccoons, predatory fish, and large birds.

This species spends most of its time in the water, only emerging to nest or find a new home if their current habitat becomes unsuitable. Mating occurs between Februrary and May, starting later in the northern regions of the species' range. Males and females seek each other out, but generally don't travel great distances. About two months after mating, females dig a nest near a body of water and deposit between 10-50 eggs. Incubation takes up to 140 days, and the average temperature of the nest determines the sex of the hatchings; the hotter it is, the more males are produced. In the fall, hatchings emerge and are left to fend for themselves. Sexual maturity is reached at between 11 and 13 years of age, and individuals can live as old as 45 years in the wild.

Conservation status: The alligator snapping turtle is listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN. The species is threatened by overharvesting for meat and for the pet trade, and by habitat destruction.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Ed Godfrey

Cindy Hayes

Eva Kwiatek

Nathan Patee

#alligator snapping turtle#Testudines#Chelydridae#snapping turtles#freshwater turtles#reptiles#freshwater fauna#freshwater reptiles#lakes#lake reptiles#wetlands#wetland reptiles#rivers#river reptiles#north america#southern north america#animal facts#biology#zoology

455 notes

·

View notes

Text

via

#alligator#reptiles#underwater#naturecore#photography#nature#water#water aesthetic#watercore#blue#green#forestcore#forest#woods#plants#lake#pond#river#1k

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

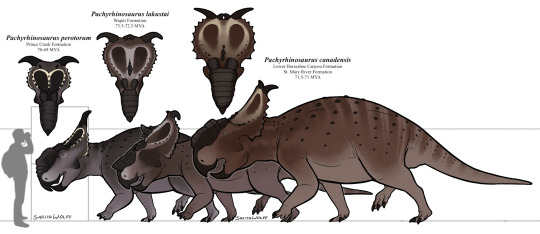

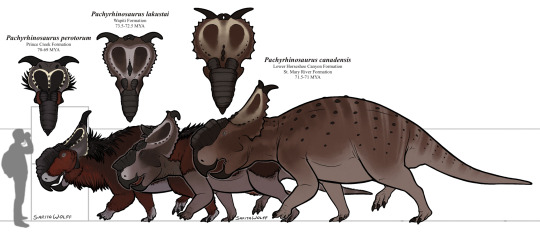

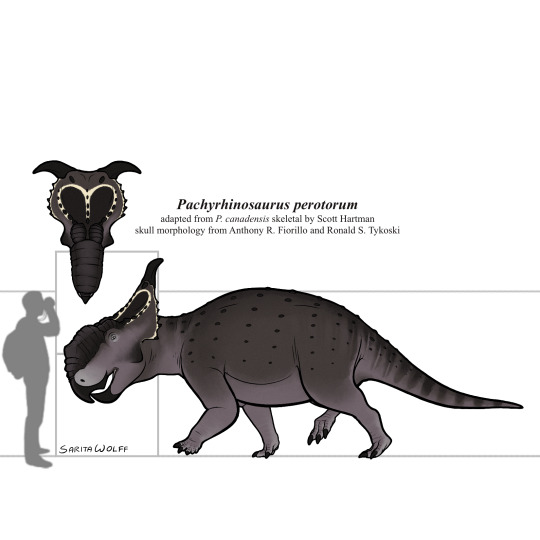

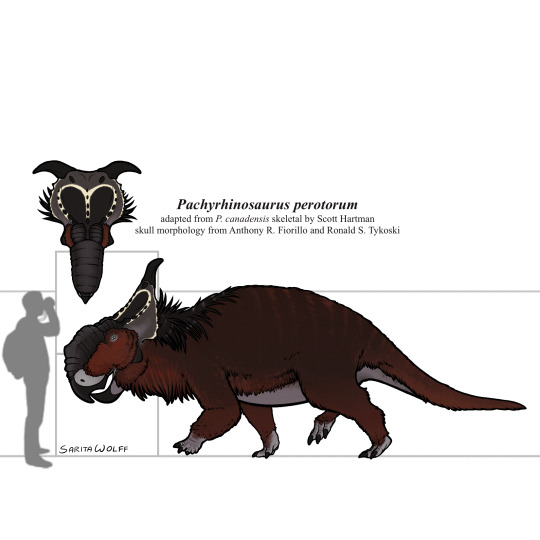

A Patreon request for rome.and.stuff (Instagram) - Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum… that I went a bit overboard with lol. I’ve been waiting for an excuse to draw my favorite ceratopsian, and to digitally adapt my old Pachy marker drawing design.

So! Pachyrhinosaurus! As seen above, there were three known species of Pachyrhinosaurus, living in different locations and eras in Late Cretaceous North America.

The oldest, P. lakustai, was native to the Wapiti Formation of Alberta and British Columbia, Canada. It’s known for the extra spikes it has at the center of its frill.

The slightly younger P. canadensis was native to the lower Horseshoe Canyon Formation and the St. Mary River Formation of Alberta and northwestern Montana. It was the largest of the three.

The youngest, P. perotorum, was native to the Prince Creek Formation of Alaska. As this ceratopsid seemingly stayed put during the long, dark, cold Alaskan Winters, it likely had adaptations for keeping warm.

The depiction of a “woolly” Pachyrhinosaurus was first popularized by Mark Witton as a speculative work, but the trope has prevailed. While many paleontologists find a heavy feather covering on a centrosaurine to be highly unlikely, and maintain that the animal’s size and homeothermy would have kept it warm enough, we still have no skin impressions to suggest that P. perotorum was fully scaly. So a feather coating is not completely out of the question (though it is unlikely). Still, I love the look of a woolly Pachyrhinosaurus and how it challenges our previous conceptions of non-avian dinosaurs. Stranger things exist in nature. I had to include a “woolly” option, especially since I already use the guy as my avatar on my paleo Instagram account, SaritaPaleo.

Pachyrhinosaurus was particularly unique in that it seemingly traded off something that had previously worked for other ceratopsians, horns, for a large nasal boss instead. For Pachyrhinosaurus, a battering ram worked better than a sword.

It was herbivorous, using its strong cheek teeth to chew tough, fibrous plants. Perhaps during the dark and cold Winters, P. perotorum would have also dug for roots or even scavenged carcasses. At any rate, from observations of their unusually conspicuous growth banding, it appears growth for P. perotorum would have been stunted during the harsh Winter, but was extremely rapid in the warmer months, an adaptation for the Alaskan climate.

The tundra of the Prince Creek Formation housed a surprising amount of diversity. Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum would have lived alongside smaller ceratopsians like Leptoceratopsids, as well as other ornithischians like the pachycephalosaurine Alaskacephale and the hadrosaurid Edmontosaurus. Theropods such as Dromaeosaurus and Saurornitholestes, as well as a yet unidentified giant Troodontid, lived here as well. P. perotorum’s main predator would have been the tyrannosaur Nanuqsaurus. Small mammals were also somewhat common here, such as Cimolodon, Gypsonictops, Sikuomys, Unnuakomys, and an indeterminate marsupial.

(Btw, the request tier for Patreon starts at only $5 a month. 😉 Link is pinned at the top of my blog.)

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Pachyrhinosaurus#Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum#Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai#Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis#Centrosaurines#ceratopsians#ceratopsids#ornithischians#dinosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Prince Creek Formation#Wapiti Formation#Horseshoe Canyon Formation#St. Mary River Formation#Late Cretaceous#Canada#United States of America

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

river friend :)

#mine#this is a harmless common water snake !#they're nonvenomous but usually grumpy and will bite#i have snake charm though ive never gotten bitten by one#snakes#river#animals#photography#animal photography#herpetology#field herping#reptiles#tattoos#hands#nature photography#ruralcore

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘Chonkosaurus,’ plump Chicago snapping turtle captured on video, goes viral

Footage of a plump snapping turtle relaxing along a Chicago waterway has gone viral after the man who filmed the well-fed reptile marveled at its size and nicknamed it “Chonkosaurus.”

Joey Santore was kayaking with a friend along the Chicago River last weekend when they spotted the large snapping turtle sitting atop a large chain draped over what appear to be rotting logs.

He posted a jumpy video of the turtle on Twitter, labeling it the “Chicago River Snapper aka Chonkosaurus.”

Read more: https://apnews.com/article/chonkosaurus-snapping-turtle-chicago-river-70a9267163efd041c2f3a13dedd258ad

#chonkasaurus#snapping turtle#turtle#reptile#animals#nature#north america#rivers#aquatic#herpetology

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today I met a very lovely friend at the Cosumnes River Preserve!

They were very patient and didn't mind at all as a dozen ecology students got up in their face with cameras, ooh-ing and aah-ing.

#I'm sure they deal with this sort of thing regularly#living by the path in the nature reserve guarantees a measure of celebrity#wild snake#Cosumnes River Preserve#racer#snake#snakes#reptile#reptiles#reptiblr#colubrid

229 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nile crocodile - Awash river, 2018

#picofthenight#travel#ethiopia#africa#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#nature#animals#reptiles#crocodile#river side#nature photography#photoofthenight

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yellow spotted Amazon river turtle 🐢

[ID: an illustration of a turtle facing to the left on a sea foam green background. The turtle is dark in color with bright yellow areas on its face and shell. It is surrounded by mossy rocks. End.]

359 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gray ratsnake (Pantherophis spiloides) - I really wish there was something to show scale in the photo because he was definitely over six feet long and as big around as my wrist

5/31/23

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abroad with the Broad Shelled Turtle

Chelodina expansa, more commonly known as the broad shelled turtle, is one of the largest freshwater turtles in Australia. The length of their shells can reach up to 50 cm (19.6 in), and their neck accounts for an additional 60-80% of their total length. Because of this length, C. expansa tucks its head in sideways as opposed to pulling it directly into its shell. At maximum, females reach a mass of 6 kg (13.2 lbs), while males only typically weigh about 4 kg (8.8 lbs). The top of the shell, or carapace, is dark brown or green, while the underside is a light cream; the same is true for the broad shelled turtle's head, neck, and legs. The feet are webbed, and have large claws which help adults to dig or fend off predators.

While they spend the winter buried in the mud, the broad shelled turtle is most active during the summer months, from November to March. During this time they are almost entirely aquatic, rarely emerging from the water even to bask. This species lives throughout the river basins of eastern Australia, and can be found in rivers, dams, lakes, and wetlands with plenty of vegetation cover. C. expansa is entirely carnivorous, feeding on crustaceans, aquatic insects, fish, and frogs via ambush, and carrion whenever it can find it. To locate prey, they have a keen sense of smell. Adults are not usually predated upon due to their thick shells and sharp claws, but eggs and juveniles are often prey for foxes, dingos, birds, rakalai, and large fish.

C. expansa nests in the winter, beginning in late February or March. Outside the mating season, individuals are generally solitary, but aggressive territoriality has not been observed. When mating time roles around, males seek out females to mate with; following the encounter, the female climbs out onto the bank and digs a nest for a clutch of anywhere from 5 to 28 eggs. To seal the nest, she then slams her body into the re-piled sand and mud, compacting it into a plug that will remain intact until the following year.

Incubation takes about 360 days, though some nests have been recorded as hatching at 500 days; this process is exceptionally slow due to the two periods of diapause, or developmental delays, that embryos pass through in order to survive the winter. Juveniles hatch in the spring, and emerge from the nest at the first heavy rain. It's unknown how long these turtles can live in the wild, but given their slow growth rate and adult invulnerability it's likely that they can live in excess of 20 years.

Conservation status: The IUCN consideres the broad shelled turtle to be Near Threatened, due primarily to habitat loss and high rates of nest predation by introduced foxes.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a kofi!

Photos

Claire Treilibs

Catherine Heuzenroeder

Shanna Bignell via iNaturalist

#broad shelled turtle#Testudines#Chelidae#snake-necked turtles#Austro-South American side-neck turtles#side-neck turtles#turtles#reptiles#freshwater reptiles#river reptiles#lake reptiles#wetland reptiles#Oceania#Australia#East Australia

252 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What a gorgeous afternoon for a Mid-April hike in the Cheat River Canyon. Spring’s delicate treasures were out in full force. From top: halberd-leaved yellow violet (Viola hastata); sweet white violet (Viola blanda); broadleaf toothwort (Cardamine diphylla); Carolina spring beauty (Claytonia caroliniana); bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis); common blue violet (Viola sororia); Allegheny serviceberry (Amelanchier laevis); sweet birch (Betula lenta) catkins; and a cranky Allegheny rat snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) newly out of hibernation.

#appalachia#vandalia#west virginia#cheat river#cheat river canyon#chestnut ridge#snake hill wildlife management area#spring#april#wildflowers#reptile#snake#allegheny rat snake#eastern rat snake#halberd-leaved yellow violet#sweet white violet#broadleaf toothwort#two-leaf toothwort#crinkleroot#carolina spring beauty#bloodroot#common blue violet#allegheny serviceberry#sweet birch#black birch

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

via

#nature#photography#Florida#alligator#springs#water#river#plants#green water#nature photography#reptiles

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

7/13/23 - Oh, to be a pile of turtles on a log,

#nature#nature log#places#potomac#potomac river#maryland#river#water#creek#stream#trees#plants#summer#turtle#turtles#reptiles#herps#animals#swamp#swampcore

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

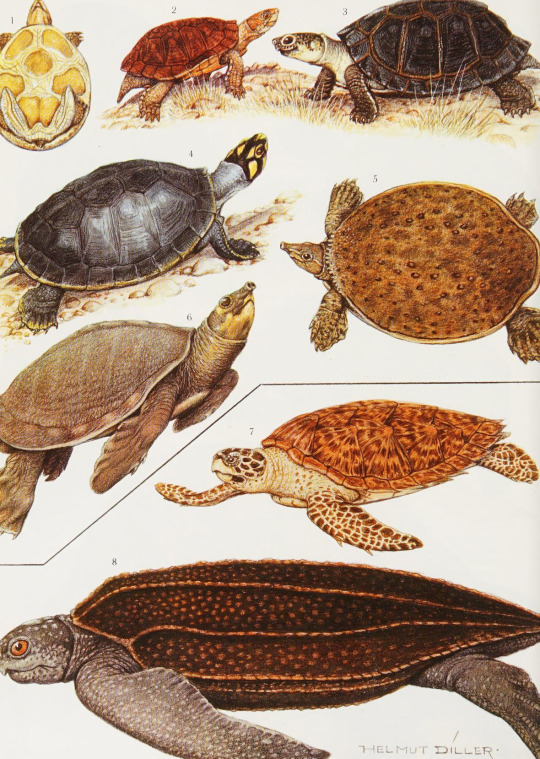

Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Volume 6: Reptiles. Written by Bernard Grzimek. 1984. Illustration by Helmut Diller.

1.) Indian flapshell turtle (Lissemys punctata)

2.) Marsh terrapin (Pelomedusa subrufa)

3.) Pan terrapin (Pelusios subniger)

4.) Yellow-spotted river turtle (Podocnemis unifilis)

5.) Spiny softshell turtle (Apalone spinifera)

6.) Pig-nosed turtle (Carettochelys insculpta)

7.) Hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata)

8.) Leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea)

#reptiles#turtles#Indian flapshell turtle#Marsh terrapin#Pan terrapin#Yellow-spotted river turtle#Spiny softshell turtle#Pig-nosed turtle#Hawksbill sea turtle#Leatherback sea turtle#Helmut Diller

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

Have you ever seen aquatic (water-dwelling) turtles sitting out in the sun (basking) together in a group?

Maybe even stacked on top of one another? Why do aquatic turtles, like these Rio Grande cooters, bask in groups?

Aquatic turtles routinely haul out of the water and bask in the sun to get warm. When there aren’t enough suitable basking spots, turtles tend to group together. Simple enough.

But is that the only reason? It’s not completely clear. Preliminary research suggests that when there are more turtles at a basking spot, they may be able to detect predators from farther away. More eyes can be a good thing.

Rio Grande cooters are what we might call “habitual baskers,” meaning they bask a lot, and they’re commonly seen in groups. These medium to large turtles (usually around 10 inches long) sun themselves on river banks, logs, and other vegetation. They’re shy, though, and will quickly slip into the water when disturbed.

Whether in groups or on their own, ARC protects these turtles throughout the US portion of their range in Texas and New Mexico. Grouping together with our supporters enables us to conserve Rio Grande cooters, other reptiles, and amphibians across the US. Stay in the loop about this work for vitally important yet often overlooked species by subscribing to our e-newsletter, The ARC’ives. Visit ARCProtects.org, and scroll to the bottom.

Photo: © Laura Keene, CC-BY-NC

via: Amphibian and Reptile Conservancy

#turtle#animal behavior#turtles#reptile#herpetology#cooter#animals#nature#north america#aquatic#rivers#texas

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

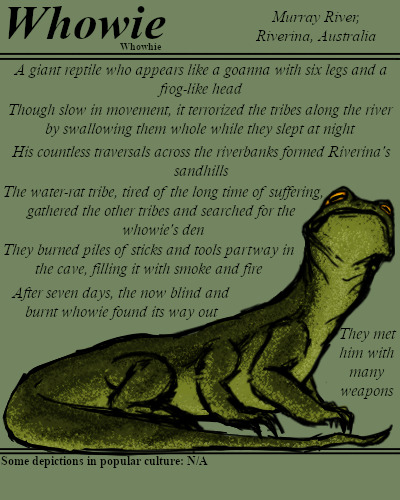

Some say that the Whowie was ultimately killed by the tribes after it had been forced out in its weakened state. Others believe that it managed to drag itself back into its cave where its weak breath can continue to be heard as it continues to approach its eventual death.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#myth#mythology#monster#whowie#whowhie#australian folklore#australian legend#australian mythology#riverina#murray river#legendary reptile

36 notes

·

View notes