#sarsnet

Text

Sloppy Latina Deep Throat POV

Busty Alexis Diamond throatfucked before anal plow

Filipina Hooker Gives A Blowjob By Stranger

Mexican female ass

Sexy girls from snapchat at videos compilation

Hot threesome video cam amateur blowjob and fuck

Sexy hot saree navel and sexy sound moaning for masturbating video check my profile for sexy saree navel pictures hd

Shirtless gay bondage and electrical And who nicer to make him learn

Stepmother Whore Beg For Crazy Orgasm By Stepson

ho chunk casino wisconsin dells room rates

#obituary#peevers#flossification#burster#low-filleted#undersaturate#pandore#raptury#unworkable#sarsnet#zestfulnesses#lore#nonmissionaries#todomomo#not-soul#Hypochaeris#distortion#underreckoning#bushbeck#defectology

1 note

·

View note

Note

I saw one of your ask about King James and I wanted to ask if you can elaborate/explain what you mean by “He's this person who is born visibly "different" (physically and sexually) from the society around him, but he's the king and so society has to adapt to that rather than he adapt to society.” I’m sorry if you already answered this question or something similar!

The most colorful complete description of what James was like comes from The Court and Character of King James I, which is a somewhat suspect and very anti-James and anti-Buckingham source. It has been said of the purported author, Anthony Weldon, that he was bitter over being dismissed from court and published this as a spiteful hit piece. But historians have cast some doubt on this. What is definitely true is that it was republished and circulated during the Civil War as Parliamentarian propaganda, to portray the whole Stuart dynasty as corrupt and degenerate.

In it the author says:

He was of a middle stature, more corpulent through his cloathes then in his body, yet fat enough, his cloathes ever being made large and easie, the Doublets quilted for steletto proof … He was naturally of a timorous disposition, which was the reason of his quilted doublets, his eye large, ever rowling after any stranger came in his presence, in so much, who that for shame have left the room, as being out of countenance; his Beard was very thin; his tongue too large for his mouth, which ever made him drink very uncomely, as if eating his drink, which came out into the cup of each side his mouth; his skin was soft as Taffeta Sarsnet, which felt so, because he never washt his hands … his legs were very weak, having as was thought some foul play in his youth, or rather before he was born, that he was not able to stand at seven years of age, that weakness made him ever leaning on other mens shoulders; his walk was ever circular, his fingers ever in that walk fidling about his cod-piece

This vivid image is what has been passed down to us as the dominant image of James. It is likely that this is exaggerated for propaganda effect. However, it does appear that James was physically different and more complimentary observers also noticed this. Albert Fontenay, diplomat on behalf of Mary QOS, described James as remarkably intelligent, but also that "He is never still in one place but walks continuously up and down, though his gait is erratic and wandering, and he tramps about even in his own chamber … His body is feeble and yet he is not delicate. In a word, he is an old young man." (this translation from Majestie: The King Behind the King James Bible) It seems he was always a weak and clumsy walker, and it is likely his obsession with riding and hunting may have come from the sense of freedom it gave him from his lower body weakness. But he was still a clumsy rider and fell off his horse into a river and almost drowned on two separate occasions. This was in addition to chronic health complaints (as he aged he got a LOT of issues, but his digestion was already bad from an early age).

His courtiers observed this, and they also observed his very open, lavish affection for his favorites. (One of the "James wasn't gay" arguments is that none of his contemporaries accused him of sodomy. Except, they totally did.) None of this could really be denied or covered up. This is also not just a time period where sodomy stands for absolute evil, but also one where physical beauty/"perfection" and inner goodness are equated. But, James was a divine right monarch and a steadfast proponent of the idea that the king is God's chosen representative on earth. How do you reconcile that? People of James's time had to do it, somehow. (Though later, in accounts like Weldon's, physical difference WAS leveraged to delegitimize Stuart rule.)

Although a lot of authors I've read talk about James's physical difference, I haven't yet read an analysis of James primarily and specifically through the lens of disability. Although I find most attempts to diagnose people of the past foolish (anyone who says "obviously James had cerebral palsy" gets a lot of side-eye from me; I'm not even sure anyone has adequately explained what his contemporaries meant when they said he had a "circular walk"), looking at him, we can probably call him "disabled". But to what extent was he dis-abled by his physical differences, and to what extent cushioned by his position as lifelong king? How did his tenure as king affect the popular concept of disability? I'm sure there's some great deep dive out there on this but I haven't found it yet, so if one of you knows of one I'd love to read it!

#james vi and i#james and disability#james's weird stan rambles again#what the heck even is a circular walk

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

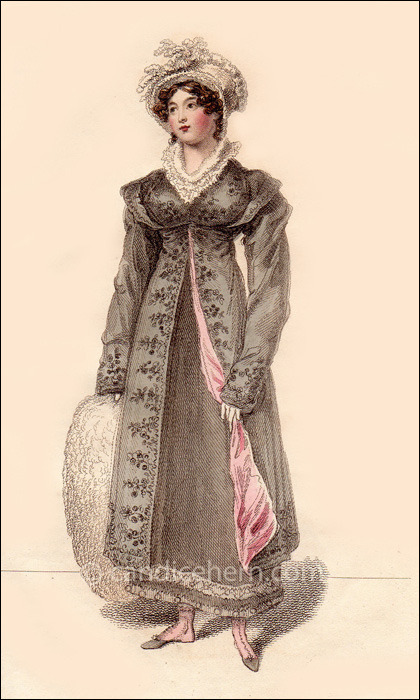

Monday Mourning

A mourning evening dress from the March 1820 edition of Ackermann's Repository.

This would have been published shortly after the deaths of George III and Prince Edward who had both died in late January. Edward was the father of 8-month-old Princess Victoria who would become Queen 17 years later in 1837.

Description of the dress by Ackermann's Repository:

"PLATE 17. — EVENING DRESS. A black crape round dress over a black sarsnet slip: the bottom of the skirt is finished by a single flounce of the same material, set. on full, and fancifully ornamented at the edge by black bugles: this is surmounted by a trimming composed of two rows of puffs; they are shaped like a shell, and are let in above each other in a drapery style. The corsage is cut very low all round the bust, which is tastefully ornamented, and in part shaded by a tucker of black crape, made to correspond with the trimming of the skirt: a double row goes from the front of the shoulder round the back of the bust. Short full sleeve, decorated in the middle by two rows of puffs, placed crosswise, to correspond with the trimming of the skirt, and finished at the bottom by a leaf-trimming, also composed of crape. Headdress, a black crape toque: a band of black bugles goes round the bottom next to the face; the top part is round; it is ornamented with bugles, scattered irregularly over it: a broad band of bias crape, doubled, goes round the top, and stands out at some distance from it; this band is also ornamented with bugles. A crape tassel edged with bugles, falls on the left side, and a plume of black feathers droops over the tassel. Necklace and earrings, jet. Black shamoy gloves and shoes.

We are indebted for both these dresses to Miss Pierpoint, maker of the corset, a la Grecquc, No. 9, Henrietta-street, Covent-Garden."

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, Etc.

Volume 6, Number 35, November 1, 1825, Third Series

Garden Costume

Pelisse of Pomona-green gros de Naples, open in front, and lined with pale pink sarsnet: plain collar, sloped off from the front, stiffened, and half turned, so as to display the pink lining and the neat embroidered frill round the throat: the corsage full, and of such a length as to shew an elegant shape to advantage: the sleeve large, and confined above the wrist by a band and small oval buckle, and secndly, by a broad gold bracelet: straight cuff, slit as far as the wrist: corded band round the waist, fastened by a gold buckle on the right side.

Plain jaconot muslin high dress: the corsage made to fit, and elegantly worked: the skirt scolloped at the edge, and ornamented with three deep tucks, and insertion-work between. Hair in graceful ringlets à la Vandyke, partly covered by a beautifully embroidered lace veil. Necklace of red cornelian, worn outside the pelisse; ear-rings to correspond. Lemon-colour gloves; purplye morocco shoes; rose-colour parasol, lined with white, and an antique wreath round the edge.

#Repository of Arts#19th century#1800s#1820s#1825#periodical#retouch#color#fashion#fashion plate#dress#costume#garden#parasol#pelisse#pomona#green#gros de Naples#sarsnet#pink#corsage#jaconot#muslin#vandyke

60 notes

·

View notes

Link

Discussion of Walking Dresses or Promenade Dresses in the Regency era

^Lady’s Monthly Museum

January 1804

“Walking Dresses”

This is only half of a larger fold-out print that included two other dresses – a morning dress and an evening dress. (You can see the line of the fold in the figure on the right.) The two walking dresses are described as follows:

“1. A light Blue Beaver Military Helmet Hat, covered with light Blue Netting, ornamented with a White Feather. A short Walking Dress of White Muslin. A Military Spencer, trimmed with Silver Cord, and Epaulette. York tan gloves.

“2. A Scarlet Velvet Bonnet, with a White Ostrich Feather. A Pelisse of Scarlet Kersimere, trimmed with Black Velvet. Brown Bear Muff.”

^La Belle Assemblée

July 1807

“Kensington Garden Dresses for July 1807”

The print is described in the magazine as follows:

“No. 1 – A plain cambric round dress, a walking length. Roman spencer of celestial blue sarsnet, with Vandyke lapels and falling collar; finished with the same round the bottom of the waist, and flowing open in front of the bosom. A village hat of Imperial chip, with bee-hive crown, confined under the chin with ribbon the colour of the spencer. Cropped hair, divided in the center of the forehead with full curls. Gloves and shoes of lemon-coloured kid. Parasol of salmon-coloured sarsnet.

“No. 2 – Round train dress of India muslin, with short sleeves, ornamented round the bottom and sleeves with a rich border of needlework. Promenade tippet of Brussels lace, lined with white satin. Hat of white chip, or fancy cap of lilac satin, with a Brussels lace veil. Hair confined in braids over the right temple, and formed in loose curls on the opposite side. Gold hoop earrings. Gloves and slippers of lilac kid.”

^ La Belle Assemblée

March 1810

“Hyde Park Walking Dress”

“A pelisse of black merino cloth or velvet, buttoned from the throat to the feet, made to fit tight to the shape with a band of crape, ornamented with a double row of gold braiding, or an oriental embossed silk trimming, worn over a chemisette of French lawn. A Spanish hat and flat drooping ostrich feather tipped with orange. Half boots of black or orange coloured Morocco; Angola muff lined with yellow [painted pink in this print]; the hair lightly curled on the left side with a thick braid crossing the face. Ear-rings of gold or amber. Gloves of York tan.”

^La Belle Assemblée

November 1812

“Morning Walking Dress”

The print is described in the magazine as follows:

“Short pelisse of deep lilac, shot with white; back broader than they were worn last month, and on each hip a Spanish button. It is made with a collar up to the throat, and trimmed round with rich fur; sleeves long and loose, with a fur at bottom to form a cuff, rather shorter in front than behind, and two Spanish buttons are placed just at the bottom of the pelisse in front, which fastens with a loop crossing from one to the other. The bosom is ornamented in the same manner; a belt of embroidered ribband round the waist, and a gold clasp in front. A bonnet of the same materials as the pelisse, crown a helmet shape, front very small, and a wreath of laurel round it; three white feathers are placed at the back of the bonnet, and fall over the front; broad ribband, same as the bonnet, is pinned plain under the chin. The hair is brought very low at the sides, and a single curl on the forehead. Buff gloves, and dark brown kid boots. Large silver bear muff.”

^Ackermann’s Repository of Arts

November 1814

“Walking Dress”

The print is described in the magazine a follows:

“An Italian striped sarsnet lilac-coloured dress, ornamented round the bottom with a double quilling of satin ribband; short full sleeve, trimmed to correspond; the fronts of the dress cross the bosom and form an open stomacher; a Vandyke French ruff, and full bordered cap to correspond. The satin straw hat, tied under the chin with a check or striped Barcelona handkerchief, crossing the crown with a small plume of ostrich feathers in front. French shawl, a white twill, embroidered with shaded scarlet and green silks, and fancifully disposed on the figure. Gloves, Limerick or York tan, drawn over the elbow. Half-boots of York tan or pale buff kid.”

^ La Belle Assemblée

January 1815

“Morning Walking Dress

^Ackermann’s Repository of Arts

November 1817

“Walking Dress”

The print is described in the magazine as follows:

“Cambric muslin high dress, the lower part of the body made full, and the upper part, which is tight to the bust, composed entirely of rich work. A row of pointed work forms a narrow pelerine, which is brought rather high on the bosom, and ends in a point in front. The bottom of the skirt is finished by a deep flounce and heading, composed of the same material, which is surmounted by a row of soft muslin bouffone let in at small distances from each other. Over this dress is worn a spencer, composed of gros de Naples, ornamented with figured buttons, which are intermixed with a light, novel, and elegant trimming. For the form of the body, we refer our readers to our print. The sleeve, of a moderate width, is finished at the wrist to correspond with the body, by a double row of buttons and trimming intermixed. The epaulette, of a new and singularly pretty form, is edged with trimming, and finished with buttons on the shoulder. Autumnal bonnet, the front rather large, and of a very becoming shape; the crown low: it is tied under the chin by a large bow of ribbon. We are interdicted from describing either the novel and elegant materials of which this bonnet is composed, or the ornament which finishes it in front. Swansdown muff, lilac sandals, and pale lemon-colour kid gloves.“

^Ackermann’s Repository of Arts

February 1818

The print is described in the magazine as follows:

“A fawn-coloured poplin round dress: the body is of a three-quarter height; it is cur byas and has no seam, except under the arm. The back is narrower than last month; the fronts just meet, but do not cross; the sleeve is long, rather loose, and confined across the wrist by a satin piping disposed in waves; they are about two inches in length, and are finished by a small silk tuft at the end of each wave. The bust is trimmed to correspond, and the skirt is finished round the bottom by three rows of satin pipings, which form a deep wave, and which are also finished by tufts.“Over this is worn a pelisse composed of fine fawn-coloured cloth, and lined with white sarsnet. The waist of the pelisse is of a moderate length, the body is tight to the shape, and it has a small standing collar. The trimming which goes down the front, and finishes the bottoms of the sleeves, is extremely tasteful; it is an embroidery composed of intermingled blue ribbon and chenille, which ha a very striking effect. The sleeve is rather wide, except at the wrist, and is finished by a half-sleeve in the Parisian style; that is to say, very full on the shoulder, and confined across the arm by a row of small silk buttons. Head-dress, a bonnet composed of satin to correspond with the colour of the pelisse, lined with white sarsnet, and elegantly ornamented with a light embroidery in straw. For the shape of the bonnet, which is singularly becoming, we refer our reader to our print: it is trimmed with blue satin ribbon and a large plume of feathers. Limerick gloves, and half-boots composed of fawn-coloured kid.”

#fashion#regency#regency fashion#walking dress#19th century#19th century fashion#fashion history#resources#gender nonconforming fashion#hats#outerwear

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Holy thorn (Crataegus monogyna cv. 'Biflora')’

“The Holy or Glastonbury Thorn is a variety of the common HAWTHORN which produces flowers in winter as well as at the usual time in early summer. What appears to be the earliest reference to the Thorn is found in a lengthy poem, entitled Here begynneth the lyfe of Joseph of Armathia, which is believed to have been written at the opening of the sixteenth century. The poem states that there were three thorn trees growing on Wearyall Hill, just south of Glastonbury in Somerset, which:

Do burge and bere grene leaues at Christmas

As fresihe as other in May when ye nightingale

Wrestes out her notes musycall as pure glas.

[Anon., 1520]

However, there is some slight evidence to suggest that the Thorn may have been in existence almost 400 years earlier. At Appleton Thorn in Cheshire a custom known as 'Bawming the Thorn' used to be per- formed each year. Basically the custom consisted of decorating a thorn tree which grows in the centre of the village. Local tradition states that a tree has stood on this site since 1125, when an offshoot of the Holy Thorn was planted by Adam de Dutton [Hole, 1976: 26]. If there is any truth in this tradition, it would imply that there was a thorn tree at Glastonbury early in the twelfth century, when the Benedictine monks at its abbey were busily accumulating their massive, but poorly authenticated, collection of relics, which was destroyed in a disastrous fire in 1184. It is quite possible that a hawthorn which produced flowers at Christmas time might have been added to the attractions provided to stimulate pilgrimages to the abbey.

The lyfe of Joseph gives no information on the trees' origins, and does not mention the production of winter flowers. Fifteen years after its publication, four years before the suppression of Glastonbury Abbey, the Christmas flowering of the Thorn was first recorded. On 24 Au- gust 1535 Dr Layton, the visitor sent to the Abbey, wrote to Thomas Cromwell from Bristol, and enclosed two pieces of a tree which blossomed on Christmas Eve.

By this bringer, my servant, I send you Relicks: First two flowers wraped in white and black sarsnet, that on Christen Mass Even, hora ipsa qua Christus natus fuerat, will spring and burge and bare blossoms. Quod expertum est, saith the Prior of Mayden Bradley. [Batten, 1881: 116]

During the reign of Elizabeth I the Thorn growing on Wearyall had two trunks:

when a puritan exterminated one, and left the other, which was the size of a common man, to be viewed in wonder by strangers; and the blossoms thereof were esteemed such curiosities by people of all nations that Bristol merchants made traffick of them and exported them to foreign parts. [Collinson, 179I: 265]

Or, according to an earlier, more credulous account:

It had two Trunks or Bodies till the Reign of Queen Elizabeth, in whose days a Saint like Puritan, taking offence at it, hewed down the biggest of the Trunks, and had cut down the other Body in all likelyhood, had he not bin miraculously punished (saith my Author) by cutting his Leg, and one of the Chips flying up to his Head, which put out one of his Eyes. Though the Trunk cut off was separated quite from the root, excepting a little of the Bark which stuck to the rest of the Body, and laid above the Ground above thirty Years together; yet it still continued to flourish as the other Part did which was left standing; after this again, when it was quite taken away and cast into a Ditch, it flourished and budded as it used to do before. A Year after this, it was stolen away, not known by whom or whither. [Rawlinson, 1722: 109]

Later, during the reign of James I, the Thorn enjoyed some popularity as a garden curiosity, and the aristocracy, including the King's consort Anne of Denmark, paid large sums for cuttings [Collinson, 1791: 265). It is possible that this fashion of growing thorns in private gardens saved the plant from extinction, for during the civil unrest later in the century the surviving trunk of the original tree was destroyed by a Roundhead, who 'being over zealous did cut it downe in pure devotion' (Taylor, 1649: 6]. In 1653 Godfrey Goodman, Bishop of Gloucester, lamented: "The White Thorn at Glastonbury which did usually blossome on Christmas Day was cut down: yet I did not heare that the party was punisheď [Rawlinson, 1722: 301].

In 1645 the Revd John Eachard described the Glastonbury Thorn, which was then much mutilated by visitors who cut off pieces of it for souvenirs, as being of the kind 'wherewith Christ was crowned'. An elaboration of this belief relates how St Joseph of Arimathea brought two treasures to Glastonbury: silver containers holding the blood and sweat of Christ (which seem to have become confused or equated with the Holy Grail) and a thorn from Christ's Crown of Thorns, which grew and proved its holiness by flowering each year at the time of Christ's birth [Hole, 1965: 39].

Seventy years after Eachard wrote, an oral tradition collected from a Glastonbury inn-keeper explained how the Thorn had grown from a STAFF carried by St Joseph of Arimathea [Rawlinson, 1722: 1). According to tradition, the Apostles divided the world between them, St Philip being sent to Gaul, accompanied by St Joseph of Arimathea, who is usually considered to be an uncle of the Virgin Mary. After some years Joseph left the Apostle and accompanied by eleven others set out for Britain, arriving at Glastonbury, and eventually founding the first church to be built on British soil, in AD 63 [Hole, 1965: 35]- When Joseph reached Glastonbury he rested on Wearyall Hill and thrust his staff into the ground, where it grew and became the original Holy Thorn [Rawlinson, 1722: 2]. Some writers have asserted that it was this miracle which caused Joseph to settle in Glastonbury.

A second version of the legend relates how St Joseph landed on the Welsh coast, or possibly at Barrow Bay in Somerset, but found the natives hostile. He continued his wanderings and reached the land of King Arviragus. Although Joseph was unable to convert the monarch, he made a sufficiently good impression for land at Ynyswitrin—Glastonbury—to be granted to him and his companions. However the local inhabitants showed little enthusiasm for the new faith. It was not until Joseph fixed his staff in the ground and prayed, whereupon it immediately produced blossoms, that people began to pay serious attention to the missionaries' preaching [Anon., n.d.: 6 and 23]. It is sometimes claimed that Joseph performed this miracle on Christmas Day and hence the Thorn has flowered on this day ever since [Wilks, 1972: 98].

Some recent writers have asserted that there is some truth in the various legends and suggest that the Thorn originated from stock brought from the Holy Land, or at least a country bordering the Mediterranean. The winter flowering of the tree is explained by the suggestion that it belongs to a variety of hawthorn native to the Middle East [Batten, 1881: 125]. The Revd Alan Clarkson, Vicar of St John's church in Glastonbury, in a pamphlet produced in 1977 in aid of church restoration funds, claimed that: 'Whatever the legend may say, a Thorn has been growing here for 2,000 years and it came from Palestine.' A recent study of hawthorns states:

In North Africa, flowering in late autumn and early winter is known also in populations of C[rataegus] monogyna that are morphologically fairly similar to the Holy Thorn of Glastonbury. [Christensen, 1992: 111]

A young leafy shoot of hawthorn, labelled 'Oxyacantha autumnalis, from Wells, Joseph of Arymathaea rod’, is preserved in the herbarium of the Natural History Museum in London. This specimen was in- cluded in a collection given by the London apothecary Robert Nicholls to the Apothecaries' Company in 1745, and was part of 'a valuable series of plants' presented by the Company to the Museum in 1862 [Vickery, 1991: 81].

It is told that, in the eighteenth century, a miller walked all the way from his home in Wales to visit the Thorn. His English vocabulary was restricted to three words, 'Staff of Joseph', but these were sufficient to ensure that he reached Glastonbury, and he was able to proudly carry home a sprig from the tree [Bett, 1952: 139].

When the calendar was reformed in 1752 the Holy Thorn attracted considerable attention, for people watched the trees to see if they would produce their Christmas blossoms according to the new or old calendar. The Gentleman's Magazine of January 1753 recorded that on Christmas Eve, 24 December 1752, hundreds of people gathered at Glastonbury to see if the several Thorn trees growing there would produce flowers. No flowers appeared, but when the crowds reassembled on Old Christmas Eve, 5 January 1753, they were rewarded and the trees blossomed, confirming the onlookers' doubts about the validity of the new calendar. Later in 1753 a correspondent of the Magazine stated that, after reports of the Thorns' flowering on Old Christmas Eve had been printed in a Hull newspaper, the vicar of Glastonbury had been questioned. According to him, the trees blossomed 'fullest and finest about Christmas Day New Style, or rather sooner' [Gentleman's Magazine, 1753: 578].

At Quainton in Buckinghamshire over two thousand people gathered to watch a thorn they remembered as being a descendant of the Glastonbury tree:

but the people finding no appearance of bud, 'twas agreed by all, that Decemb. 25 N.S. could not be Christmas-Day and accordingly refused going to church, and treating their friends on that day as usual; at length the affair became so serious, that ministers of neighbouring villages, in order to appease the people thought it prudent to give notice, that old Christmas-Day should be kept holy as before. [Gentleman's Magazine, 1753: 49]

Until early in the present century people continued to visit Holy Thorns on Old Christmas Eve.

It is believed that the Holy Thorn blossoms at twelve o'clock on Twelfth Night, the time, so they say, at which Christ was born. The blossoms are thought to open at midnight, and drop off about an hour afterwards. A piece of thorn gathered at this hour brings luck, if kept for the rest of the year. Formerly crowds of people went to see the thorn blossom at this time. I went myself to Wormesley [Herefordshire] in 1908; about forty people were there, and as it was quite dark and the blossom could only be seen by candle light, it was probably the warmth of the candles which made some of the little white buds seem to expand. The tree had really been in bloom for several days, the season being extremely mild. [Leather, 1912: 17]

A thorn in the garden of Kingston Grange in Herefordshire was annually visited by people who came from miles around, and 'were liberally supplied with cake and cider' [Leather, 1912: 17]. However, such convivial gatherings sometimes gave way to unruly behaviour, and some people destroyed thorns growing on their property so that unwelcome visits might be stopped. Near Crewkerne in Somerset, in January 1878:

Immense crowds gathered at a cottage between Hewish and Woolmingstone to witness the supposed blooming of a 'Holy' thorn at midnight on Saturday. The weather was unfavourable and the visitors were impatient. There were buds on the plant, but they did not burst into flower as they were said to have done the previous vear. The crowd started singing and then it degenerated into a quarrel and stones were thrown. The occupier of the cottage, seeing how matters stood, pulled up the thorn and took it inside, receiving a blow on the head from a stone for his pains. A free fight ensued and more will be heard of the affair in the Magistrates' Court. [Pur man's Weekly News, 10 January 1978]

Similarly:

A Holy Thorn made a brief appearance in Dorset in 1844 in the garden of a Mr Keynes of Sutton Poyntz. It was rumoured that it had grown from a cutting of the famous Glastonbury Thorn and was expected to blossom at midnight on Old Christmas Eve. 150 people turned up to see the event. Violent scenes took place, the fence was broken down and the plant so badly damaged that it died. [Waring, 1977: 68]

Not surprisingly, tales were told of misfortunes (many of which were very similar to those which befall people who destroy LONE BUSHES in Ireland) which happened to those who attempted to cut down Holy Thorns. An early attempt to destroy a tree resulted in thorns flying from the tree and blinding the axeman in one eye, so that he was 'made monocular' [Howell, 1640: 86]. A man who attempted to cut down a tree that grew in his garden at Clehonger in Herefordshire was more lucky and was let off with a warning: 'blood flowed from the trunk of the tree and this so alarmed him that he left off at once!' [Leather, 1912: 17]. A farmer who destroyed a thorn at Acton Beauchamp in Worcestershire was successful, but within a year he broke an arm and a leg, and part of his house was destroyed by fire [Lees, 1856: 295].

Shortly before Christmas each year sprays from a Thorn tree which grows in St John's churchyard in Glastonbury are sent to the Queen and Queen Mother. In 1929 the then vicar of Glastonbury, whose sister-in-law was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Mary, sent a sprig to the Queen, reviving, according to some writers, a pre-Reformation custom [Anon., 1977]. A report in the Western Daily Press of 20 December 1973 stated that the custom started in Stuart times, and it is recorded that James Montague, Bishop of Bath and Wells, sent pieces of the Holy Thorn and Glastonbury's miraculous WALNUT tree to Queen Anne, consort of James I [Rawlinson, 1722: 112]. About a week before Christmas a short religious service is held around the Thorn. Children from St John's Infants' School sing carols and play their recorders, and the vicar and mayor of Glastonbury cut twigs from the tree. It is said that the Queen has her sprays placed on her breakfast table on Christmas morning, while the Queen Mother has hers placed on her writing table. Letters sent by ladies-in-waiting to the vicar, asking him to convey thanks to the people of Glastonbury, are pinned on the church notice board [Vickery, 1979: 12].

The tree in St John's churchyard which had been used for this ceremony died early in 1991, but fortunately there is a younger tree growing in the churchyard, and other Holy Thorns may be found in the Abbey grounds, outside St Benedict's church, and in private gardens in Glastonbury.”

—

Oxford Dictionary of Plant-Lore

by Roy Vickery

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Historical Guide to | Getting Dressed in the 18th Century [ 1701 - 1800 ] Part 2 Outer Garments !! Female Clothing | Middling - Lower Class | Colonial England - Colonial North America Styles

Check out part 1 here!

Hi friends! I hope you are well. This is part 2 of a historical guide to getting dressed in the 18th century. This got long so there will be a part 3 for everything else. :)

I wanted to share this with you because a lot of what people know of historical costuming is based on tv shows, like Outlander, Poldark, Turn, or Harlots &c. … While some of the clothing is based off extant garments that did exist, many hollywood productions take extreme creative liberties that are not historically accurate to the time period. This post will contain the outer garments and all the correct terms that you may want to include when describing your characters clothing or the way their body moves in the clothing in rpgs. Clothing standards and trends did evolve over the the course of the 18th Century and did vary widely based on social class status, location, religion, race, ethnicity, nationalities and cultures.

For the majority of the English / American experience during the 18th Century, most would have been of the Middling - Lower social class; working class as trades people, farmers, servants, slaves or employed by the military in various different occupations [want a guide?] .

Assume everything was hand sewn using either linen, or silk threads, with linen, wool, and some cotton prints (and more!) materials. If you have specific questions about materials please ask.

If you have any other questions please ask me. I can help you with research :) If you are interested please continue reading more…

This list is in order of first layer to last.

Everything a woman wore in the 18th century was either tied or pinned on, with the exception of riding habits, worn while on a journey on horseback. If a person had the means to have a set. Riding habits mimic the males style with buttons and were often accompanied with a waistcoat, a long sleeve shift, and petticoats that matched the riding habit.

PETTICOATS also known as “the skirts” or “skirt”, a term which did not come into use until the mid 19th century. Would have been worn by all classes of women during the 18th century. The Petticoat is worn in such a way where the two bands and petticoat ties are tied around the front of the body. Women would wear at least two - three layers of petticoats with the first usually a light-weight linen so it can be laundered if needed. Other layers could be made from worsted wool, flannel, linsey woolsey, hand quilted silk, hand quilted flannel or a documented cotton print of petticoat to match the outer gown of the same print.

GOWN As stated at the beginning of this post, clothing for the individual person varies widely in size, style, shape, and color. The outer garments are no exception. The style of gown that we’ll focus on is an English style gown, which includes a stomacher and robings, the most common style for the majority of the 1760’s - 1770’s. Gowns varied from location to location and from culture to culture. Gowns could be made from any material such as silk, lightweight wool, linen, linsey woolsey, printed cotton, or printed calico and chintz.

BEDGOWN | Bedgowns became a staple in British and American wardrobes and not usually seen until the later half of the 18th Century. They are most appropriate for early morning and nighttime wear as they are described as a ‘wear-at-home’ clothing item. Bedgowns can be made from different kinds of fabric such as worsted wool, wool flannel, documented cotton print, linsey woolsey, and linen. Bedgowns of the period come to just about thigh length, and are often topped with an apron to finish the outfit.

APRONS While aprons can be a decorative item of clothing for a woman’s wardrobe as it was the outermost layer that was first visible, aprons can be described as a utility item of clothing. They not only help close all the layers around the body but could be used to protect the other layers from getting dirty. Since aprons were the first line of defense for the other layers they were most commonly made from linen in order to be laundered and were made from a in a variety of patterns and colors, such as blue or brown check, small stripes or solid white. Plain worsted wool aprons were also documented in this era. Aprons should be narrowly hemmed around the edges and be long enough to meet the length of your petticoat or just an inch shorter. All material should be stroke gathered into a narrow waistband of the same fabric and should fasten with narrow linen or hand loomed tapes around the waist and tied in the front of the body.

CAPS There are many different styles of caps and the style of the cap is up to the individual. Caps would always be worn to cover most of the hair, sitting at the crown of the head, secured to the hair with straight pins. Caps would have been made out of a very thin (nearly transparent) bleached white linen, and decorated with a silk ribbon.

SILK BONNETS Were one of the more popular style of hat worn on the east coast with an overwhelming amount of women and children having one. According to the blog kittycalash and her post A Bonnet, Universally Acknowledged: “ Brim shape and bonnet material— fabric and colour– vary by period (and region). So let’s look at Boston in the first years of the 1770s. One tricky bit is that there are fewer indentured servants and enslaved people in Boston than elsewhere in the American Colonies in this period, so runaway ads are scarce, giving us fewer clues than we get in Pennsylvania and points south. Still, there are plenty of ads to help guide us … Most bonnets (70%) were black, but a few white, green, crimson, and blue were seen. Most bonnets were made of silk satin, with others of taffeta or sarsnet (sometimes twilled silk). Most bonnets would have a shorter, higher brim that curves across the face just above eye level, with a high, rounded crown/caul and bow trims. Bonnet brims would vary between bonnet (paste) board and boned. ”

CLOAKS | Cloaks most commonly appeared in red and blue, but also may be cream, gray or black. The hood may be lined in a white or color matching silk, wool, or linen and the closures should be made from period correct hook and eyes or ties. The Edges may be faced in wool plush or matching silk. Period appropriate gimp may also be used. Cloaks could be in a variety of lengths as well otherwise known as a “short cloak”.

image by wickersty

[ more to come in a part 3! ]

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charles V & Germaine de Foix

Years ago, historian from Valencia, Regina Pinilla Pérez de Tudela, during her research for doctoral thesis about Germaine de Foix, found documents, that would indicate Germaine and her step-grandson, Charles V, had a love affair.

Germaine was the second wife of Ferdinand II of Aragon, who married her in order to double cross his son-in-law, Philip the Handsome, allying himself with his natural enemy, Louis XII of France, and to get a male heir, given the salic law in his kingdom, according to which, the crown would go straight into Philip’s hands after Ferdinand’s death.

At the time Germaine was 17 and Ferdinand 53 years old. In May of 1509 Germaine gave birth to Ferdinand’s son, John, who died shortly afterwards. They did not have more children.

In 1515 the Venetian ambassador Zuan Badoer said that:

The Queen his wife, a French woman, the sister of Monseigneur de Fois, is very fat, and she will not bear children.

Ferdinand, exhausted by severe illness and his long, and turbulent reign, died on 23th January of 1516. In the instructions directed at his grandson, Charles, the king asked him to take care of his young widow:

…after God there is nothing more left to her but you…

In 1516 Germaine did not have anyone of her closest family, who could take care of her. She became an orphan before her marriage to king Ferdinand, her brother Gaston de Foix, died in the battle of Ravenna in 1512, and her uncle, Louis XII of France, passed away in 1515. Although she was a claimant to the throne of Navarre, it was conquered by Ferdinand in 1512 and annexed to the Crown of Castile three years later, making his daughter, Joanna I of Castile, its nominal Queen. Germaine was left alone in foreign and hostile country.

Charles came to Spain in 1517 already as the king (he had been proclaimed the King of Castile and Aragon, on 14th March 1516 at the church of St. Gudule in Brussels) accompanied by his older sister, Eleanor of Austria. During his first meeting with the Queen Dowager, Charles kissed and greeted her, doing the same with her ladies-in-waiting. The eyewitness of the meeting, Laurent Vital noted:

…I heard that he [Charles] had won then the love of one Lady…

Manuel Fernández Álvarez, one of Charles’ biographers, did not have any doubts as for the identity of the said lady. It was Germaine de Foix, the Dowager Queen of Aragon.

It seems that in spite of the age difference – in 1517 Charles was 17 and Germaine 29 years old – they had many things in common. They both spoke French and were raised in similar fashion, also they both found themselves at foreign and hostile court.

Germaine was seen in Spain as a symbol of betrayal and many misfortunes were attributed to her, including Ferdinand’s death, allegedly being a result of love potions that she had prepared.

Charles according to Ferdinand and many Castilians, and Aragoneses, was not the best candidate for the heir because as a foreigner, he did not speak the language and did not know the culture, and customs of the kingdoms that he would one day rule. In spite of the intense efforts and requests of Ferdinand and Isabella, directed at Philip the Handsome, the latter did not agree to send his eldest son to Spain where he would be raised.

Charles’ younger brother, however, was born and brought up in his grandparents’ kingdoms, and as such was a better option, according to many. But at the end of the day, Ferdinand the Catholic decided to respect the law and Isabella’s last will, and hence in his testament, dictated on 22th Januray 1516, in Madrigalejo, he designated Charles to be Joanna’s successor and regent.

The above mentioned historian, Manuel Fernández Álvarez, presents many proofs that would support his and Regina Pinilla Pérez de Tudela’s theory. It was Germaine in whose honour the young king threw banquets and tournaments and like Vital mysteriously added:

And no wonder because nothing is impossible for people who are in love…

Charles’ palace and Germaine’s residence in Valladolid were situated close to each other but it was not enough for Charles, who ordered a wooden bridge to be lifted between them:

…so the king and his sister could go to visit the said Queen in more privacy…

…and also the said Queen used it to go to the King’s palace…

…it was very useful and especially for these who were in love, who thanks to it [the bridge] could go to visit their beloved ones…

In spite of the Flemish chronicler’s suggestions, historians have ignored these adventures of the young king. It is possible, given the construction of Vital’s testimony, that they did not notice anything – for it was incestous relationship, against all the morals and Charles was always considered a very religious man and defender of the Christian faith. Maybe that’s why they also ignored other evidence that is stored at the Archivo General de Simancas and is much more solid than Vital’s insinuations, which may have been taken as innocent rumour.

There is the testament and last will of Germaine de Foix in which she said:

…we leave that string of thick pearls that belongs to us and is the best that we have, which consists of 133 pearls, to the Most Serene doña Isabel, infanta of Castile, daughter of His Majesty the Emperor, my lord and son… And I do this because of the great love that we have for Her Highness…

Germaine did not mention the mother of the said infanta but her third husband, Ferdinand of Aragon, Duke of Calabria, in the letter to the Empress Isabella, Charles V’s wife, in October of 1536, wrote:

Your Majesty will see the legacy of pearls that she leaves to the Most Serene Infanta doña Isabel, her daughter. Your Majesty will let me know if it serves You for it to be sent with proper man…

It is possible the said Isabel was being raised at her step-mother’s court or at some nunnery, however, it must have been a great secret, because this girl’s life is shrouded in mystery. She did not have a right to use the title of the infanta because Charles never recognized her as his child.

Certainly it was not one of the Emperor’s daughters by his wife, since none of them was named Isabel and the Duke of Calabria in his letter specifically said it was Germaine’s child.

Germaine accompanied Charles on his trip to Barcelona, where in 1519 she got married to the Marquis of Brandenburg.

Later we find her at Charles’ side again, on his trip to the Netherlands. In May of 1520 both of them visited England, as we can read in the base Letters and Papers:

Outside the gates of Canterbury were 60 dappled palfreys, saddled with women’s pillions, but empty; the pillions were all of cloth of gold, one of them being embroidered with fine pearls and jewels. These palfreys had been prepared for the Queen Germainede Foix, the French woman, relict of the late King Ferdinand the Catholic, now married to the Marquis of Brandenburg.

After dinner there was dancing, and in the evening, the Queen Germaine and 60 ladies on horseback, mounted on white palfries saddled with cloth of gold, made their entry. She was met, amongst the rest, by the Lady Mary, late Queen of France, and accompanied also by 200 Spanish ladies dressed according to their own fashion, but with long thin veils and small caps on their heads as worn in Flanders, with flaps (coste) and double brims, also in the Flemish fashion, some white, some green, and some tawney. These ladies were not handsome, but graceful (gratiate), and very attractive from their Spanish costume.

On the morrow, Whit Monday, at the hour of mass, the King accompanied by the ambassadors, and with no less pompous a retinue than on the preceding day, came from the abbey (his abode) to the cathedral; inside which, near the door, he awaited the Emperor and his train; and after they had embraced, placing him on the right hand, he took him to the high altar to the appointed pew.

Shortly after, the Queens came—first the Queen of England; and then Queen Germaine, and the Lady Mary, the former being on the right hand as a mark of honour for a foreigner, and she was accompanied to her abode by 120 ladies, besides the 20 Spanish dames, all most richly arrayed.

Queen Germaine was dressed in cloth of gold in the Flemish fashion.

The Queen Mary in cloth of silver lama.

In the Emperor’s company was the Prince of Orange, a youth about 18 years of age. His entire costume—doublet, hose, and shoes— was all of silver lama, striped longitudinally with cloth of gold; and so wide were the sleeves of his doublet, which were lined with cloth of gold lama, that they almost touched the ground; and the hose and doublet joined in jacket fashion, with three plaits; his shirt being of red murrey sarsnet, which contrasted admirably with his white arms.

The mass was celebrated in state, and the Sovereigns being then accompanied to the Emperor’s chamber, their Majesties dined together. The Emperor sat at the centre of the table; on his left the King; to the right of the Emperor, the Queen of England; to the left of the King, the Lady Mary; and to the right of Queen Katharine, Queen Germaine.

The right reverend Cardinal of York, Queen Germaine and the Lady Mary, having washed their hands together, seated themselves at table, and the Cardinal to the right of Queen Katharine, but there was space between them for another chair. To the right of the Cardinal was Queen Germaine, and to the left of the King, his sister, Queen Mary, these six sitting at the table placed at the head of the hall.

On the morrow, Tuesday, the Emperor and the King rested part of the day, and then sat in council until late in the evening, when, at about an hour after sunset, the Emperor quitted Canterbury, accompanied by the King and Cardinal, without the ambassadors, who were told to remain behind, though all the rest of the royal retinue followed by torchlight, the torches not being many, but of wax, and very long indeed, in the English fashion; and having quitted Canterbury together, their Majesties took leave of each other five miles thence. The Emperor however was accompanied towards Sandwich by Cardinal Wolsey; the King proceeding to Dover; the Queens also doing the like, and Queen Germaine taking leave of Queen Katharine.

Charles never forgot about Germaine and in spite of the fact that after Ferdinand the Catholic’s death, he arranged two more marriages for her, she often accompanied him on this journeys. In 1523 he designated her to be the Viceroy of Valencia and when her second husband passed away, she lived at his court. She was also present at the official betrothal banquet of Francis I of France and Eleanor of Austria, sitting next to Charles as his pair. In 1526 the Emperor decided to marry her off again.

Of course, it can be said that Charles simply fulfilled his grandfather’s will – it is weird that any ambassador or any of the Emperor’s enemies did not say a thing about his suspicious relationship with the Queen Dowager. But even thought Germaine’s presence at the court and the chronicler’s suggestions may be taken as details of no importance, such documents as the Queen’s last will and her husband’s letter to the Empress, can not be simply dismissed and ignored.

There is a new thesis in regard to the identity of the mysterious Isabel de Castilla, daughter of Charles V and Germaine, of whom we don’t have any records besides the above mentioned documents. Pere Maria Orts put forward a theory that one of the Emperor’s illegitimate daughters, known as Margarita de Parma and Isabel de Castilla are, in fact, one and the same person.

Margarita went down in history as the daughter of Johanna Maria van der Gheynst, one of Charles’ mistresses and was one of the two illegitimate kids, whom the Emperor officially acknowledged. (In general Charles sired at least five bastards by as many different mothers and recognized only two of them.)

She was born in 1522, in Oudenaarde and was raised at the court of Margaret of Austria, Charles’ aunt. Margaret provided her with solid education and had done everything in her power to persuade Charles to acknowledge the girl, which he eventually did, in 1529. After Margaret of Austria’s death, it was the Emperor’s sister, Mary of Hungary, who took care of her niece.

Charles mentioned Margarita in his last will:

…being in Flanders, before I got married and betrothed, I had had a natural daughter whose name is Madame Margarita…

Pere Maria Orts based his theory on some documents and Margarita’s portrait, made by Antonio Moro, where she wears the string of thick pearls – allegedly the same that once belonged to Germaine de Foix.

The historian points to the document that was signed by Charles in February of 1537. It refers to the matrimonial tax that should be paid by the inhabitants of Valencia, on the occasion of the wedding of his illegitimate daughter, Isabel, and Alessandro de’ Medici, that had taken place a few years earlier. It is well known that Margarita de Parma was Alessandro’s wife and after his death in 1537, she got married again, this time to Ottavio Farnese, Duke of Parma.

Orts did not establish whether Germaine was, in fact, Margarita’s mother but it seems there is no certainty that she was born in Oudenaarde as the daughter of Johanna Maria van der Gheynst. If Margarita and Isabel were the same woman, assuming that her mother was Johanna Maria, it is hard to explain why Germaine de Foix would leave her the most precious jewels that she had, speaking of her with such tenderness and love in her testament and last will. Given Margarita was brought up at the court of Margaret of Austria, being born in 1522, the Queen Dowager would not have a chance to meet her, let alone form a bond with the girl.

Some claim that the incestous relationship between Germaine and Charles did not take place because no one noted her pregnancy and the ambassadors, as well as the Emperor’s enemies, would use this against him. No one, however, has found a way to explain Germaine’s last will and the letter, in which it was clearly stated that Charles and the Queen Dowager had a daughter.

Sources:

1. Carlos V, el César y el hombre, Manuel Fernández Álvarez

2. Między wojną a dyplomacją: Ferdynand Katolicki i polityka zagraniczna Hiszpanii w latach 1492-1516, Filip Kubiaczyk

3. (x)

4. (x)

5. (x)

#perioddramaedit#historyedit#carlos rey emperador#charles v#germaine de foix#germaine of foix#germana de foix

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

sarsnet with sash window

who’s sashes might swell

cellar man seen vulnerable at unusual angle

through cellar has chest

weeping dryly

fingering the mutton with abandon

his face bows in on itself in a violent wilt that is

unbelievable and alarming.

it would have been impossible from my place motionless and obscured in the convex rutted spine of the court mortised split-rail fencing with odd patches of chainlink remaining like a sick mammals hair (far)

fixto tell whether / what his sickle gash mouth migh mumber

rephrase distance safety glass

face mangly as i said

across the court through four layers safety glass

from across the way and with the layers of safety glass

whether the umber sickle gash that is his mouth is mangling in silence or actually emitting the whimpering sounds that are

unbelievable as I said

besides seesaws abruptly but at an even cadence

patches of chainlink rot seemed potentially cosmetic

functionless touching me

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of Anne’s maids of honour was a very beautiful girl of about eighteen, Katharine, the orphan daughter of Lord Edmund Howard, brother of the Duke of Norfolk, and consequently first cousin of Anne Boleyn. During the first months of his unsatisfying union with Anne, Henry’s eyes must have been cast covetously upon Katharine; for in April 1540 she received a grant from him of a certain felon’s property, and in the following month twenty-three quilts of quilted sarsnet were given to her out of the royal wardrobe.

The Wives of Henry the Eighth and the Parts They Played in History - Martin Hume

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, Etc.

Volume 9, Number 52, April, 1813

Carriage Costume

Carriage Costume

A high round robe of jaconot or cambric muslin, with plaited bodice, long sleeve, and deep falling frill, terminated with a vandyke of needle-work. A Russian mantle, of pomona or spring green sarsnet, lined with white satin, and trimmed with rich frog fringe and binding, confined with a cord and tassel, as taste or convenience may direct. A cottage slouch bonnet, of corresponding materials, edged with antique scollopped lace, confined under the chin with ribband, tied on the left side; and appositely ornamented with a small cluster of spring flowers. Slippers of green kid, or jean, and gloves of primrose kid.

#Repository of Arts#1800s#1810s#1813#periodical#retouch#fashion#fashion plate#dress#carriage#costume#vandyke#Russian#mantle#bonnet#flowers#frog fringe#sarsnet#jaconot#cambric#muslin

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, Etc.

Volume 10, Number 60, December 1, 1820, Second Series

Walking Dress

A high dress composed of bright grey bombasine: the skirt is trimmed at the bottom with velvet bands to correspond in colour; they are bias; are scolloped at one edge, and plain at the other: there are four of these bands, placed at a little distance from each other; the bottom one is rather more than half a quarter in breadth; the others are each something narrower. The body is tight to the shape: the long sleeve is rather straight, and falls a good deal over the hand; it is finished by three bands of velvet to correspond with those on the skirt, but much narrower: full epaulette, intersected with bands, which form into bias puffs: small standing collar, composed of velvet. The pelisse worn with this dress is composed of velours simulé, lined with sarsnet, and wadded; the colour an Egyptian brown: the skirt is rather wide; it is finished at the bottom by a broad band of velvet to correspond, above which is placed a trimming of the same material as the pelisse: it consists of two thick rolls, one of which is wreathed in a serpentine direction round the other, and both are ornamented with narrow folds of satin and gros de Naples mixed, which are fancifully twisted round them. The fronts are fastened up by full bows and ends. The waist is of a moderate length; and the body, which is plain, is almost concealed by a large pelerine trimmed with velvet to correspond. The sleeve is of moderate width; it is finished at the hand with velvet. High standing collar, fastened in front by a full bow. Head-dress, a bonnet to correspond in colour with the pelisse: it is a mixture of velvet and gros de Naples; the crown, low and somewhat of a melon shape, is covered with scollops of gros de Naples, edged with velvet, which stand up round it, and form a cluster on the summit. The front is very deep; it is rounded at the corners, and finished at the edge by a band of bias velvet; a bias band of satin, laid on in folds, is attached to the edge of the velvet, which is next the crown; and satin bows, fastened with a knot in the middle, are placed at regular distances. A full bouquet of roses mixed with fancy flowers, ornaments one side of the crown, and Egyptian brown strings tie it under the chin. Half-boots, to correspond with the pelisse. Limeric gloves.

We are indebted to Miss Pierpoint, inventress of the corset à la Grecque, No. 9, Henrietta-street, Covent-Garden, for [this dress].

#Repository of Arts#19th century#1800s#1820s#1820#periodical#retouch#color#fashion#fashion plate#dress#walking#high#bombasine#velvet#velours simulé#sarsnet#pelisse#Egyptian#brown#gros de Naples#pelerine#satin#bias#corset à la Grecque#credited#bows

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, Etc.

Volume 7, Number 40, April, 1826 (Third Series)

Carriage Costume

Pelisse of Turkish satin of a bright blue or hyacinthine colour, lined with white sarsnet and fastened in front; the collar square and turned down; the corsage plain and close to the shape, and ornamented on each side with a row of diamonds of the same material as the dress, edged with a narrow satin rouleau of the same colour, and united with a satin button. The two rows diverge towards the shoulders and meet in front at the waist, where the diamonds unite in pairs, and gradually increase in size as they descend; two rows of swansdown adorn the bottom of the dress, between which s an elegant satin scroll. The sleeve is still en gigot, but much smaller from the elbow to the wrist, which has three diamond ornaments to correspond, place perpendicularly. The ceinture has a highly wrought gold buckle in front; deep square collerette of British Brussels lace; cap of white crèpe lisse; a bouquet of damask roses on the right side, and others variously disposed. The hair in large curls, arranged to accord with the border of the cap, which is full, and of folded crèpe lisse. Gold ear-rings and bracelets; gold chain and eye-glass; jonquil-colour kid gloves and shoes.

We are indebted to Miss Davis, of Charlotte-street, for the above elegant costumes.

#Repository of Arts#19th century#1800s#1820s#1826#periodical#retouch#fashion#fashion plate#dress#carriage#costume#pelisse#satin#Turkish#blue#hyacinthine#red white and royal blue#sarsnet#corsage#rouleau#gigot#British#Brussels#lace#crèpe lisse#jonquil#credited

47 notes

·

View notes

Link

Article giving the definition and description of “morning dress” in the Regency era

(Image at top:

La Belle Assemblée

March 1812

“Morning or Home Costume”The print is described in the magazine as follows:“A white cambric frock, with a demi train; short sleeves fastened up in front with cordon and tassels; a necklace formed of two rows of opal; the hair dressed in full curls, and confined by a demi-turban of very fine muslin tied on the right side with a small bow; silk stockings with lace clocks, richly brocaded, and plain black kid slippers.”)

^Ackermann’s Repository of Arts

August 1813

“Morning or Domestic Costume”

The print is described in the magazine as follows:

“A petticoat of jaconet or cambric muslin; with a Cossack coat, or three-quartered pelisse, of lemon-cloured sarsnet, with vandyke Spanish border of a deeper shade. Full sleeves, confined at the waist with a broad elastic gold bracelet; confined also at the bottom of the waist, with a ribband en suite. Foundling cap of lace, with full double border in front, confined under the chin with a ribband the colour of the pelisse, tied on one side; a bunch of variegated carnations placed on the left side. Gloves and Roman slippers of lemon-coloured kid.”

^Ackermann’s Repository of Arts

October 1815

“Morning Dress”

The print is described in the magazine as follows:

“A cambric muslin petticoat, ornamented at the feet with a double flounce of French work, appliquéd with a narrow heading of the same;the body, from the shoulder to the neck, gathered full into narrow trimming, corresponding with the heading of the flounce; a military collar, frilled with the French work, short French negligé open in the front, and trimmed entirely round to coorespond; long loose sleeve, gathered into a narrow trimming at the wrist, with a ruffle of the same French work. A round cap, composed of white satin and quilled lace; a white satin rose in the front. Stockings, ribbed silk. Slippers, red morocco or black kid.”

^Lady’s Monthly Museum

January 1802

“Morning Dresses”The print is described in the magazine as follows:“1. A crimson velvet bonnet, with a crimson feather. A tippet of crimson velvet, trimmed with balck fur. A chemise handkerchief, with a frill. A palin gown. Crimson shoes; York tanned gloves; and bear-skin muff.

“2. A bonnet of balck and blue velvet, with ribbands of the same colours. A lead-coloured silk spencer, trimmed with white fur, and ribbands to suit the bonnet. A plain gown. Yorked tanned gloves; and blue or black shoes.”

^ Ackermann’s Repository of Arts

October 1810

“Morning Dress or Costume à la Devotion”

^ Ackermann’s Repository of Arts

August 1818

“Morning Dress”

“A high dress composed of jaconet muslin: the body ha a little fullness in the back; the fronts are plain, and wrap across in the style of a fichu. A row of richly worked trimming, headed with a doudle rouleau of muslin, through which a coloured ribbon is run, ornaments the back between the shoulders, and goes down on each side of the front. Instead of a collar, the body is ornamented at the throat by a single row of work, headed by a rouleau of muslin. The skirt is of an easy fullness; it is richly embroidered round the bottom in a light pattern of branches of leaves placed upright. Over this dress is worn a pelisse composed of pearl-coloured striped lutestring, trimmed round with a row of light embroidery in a wave pattern of pearl-coloured silk. The body is made plain, tight to the shape, and the waist is of a moderate length; it has no collar, but is finished at the throat by a frill of pointed blond. Plain long sleeves, embroidered at the wrist to correspnd with the skirt of the pelisse. Head-dress, the Clarence bonnet, compoised of blond intersected with pipings of pale pink satin, and ornamented with a full garland of moss and damask roses and bluebells. This bonnet is of a French shape, but it is a moderate and becoming size: it is tied under the chin with pale pink satin ribbon. Lemon-coloured gloves, and pale pink slippers.”

#fashion#regency#regency fashion#fashion history#19th century#19th century fashion#morning dress#resources

102 notes

·

View notes