#scientific marxism

Text

The "Capitalism vs. Socialism" Debate is a DISTRACTION

youtube

#politics#leftism#socialism#capitalism#leftblr#socialist#progressive#western propaganda#Kolkhozes#market#Soviet Union#utopian and scientific#Free marketism#社会主義#資本主義#マルクス#Scientific Marxism#Marxist#Leninist#marxismo#leftisms#production#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Avoid dogmatism. Every revolution has errors, and your time and place are different from theirs. If you apply theory blindly, you don't understand it. We need the creative and scientific application of theory.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marxism as a “Scientific” Revolution?

So I happen to be reading both The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels, and The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas Kuhn, at the same time, and there really seems to be some sort of connection here, at least philosophically / theoretically... might be worth looking into for someone in academia...

#marxism#scientific revolution#the communist manifesto#karl marx#friedrich engels#the structure of scientific revolutions#thomas s. kuhn#thomas kuhn#academic#academia#connection#breadcrumbs#research#philosophy#theory#research paper#research question#philosophy paper

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Undoubtedly capitalism as a ruling principle has had its day: human evolution has passed it by. This is no longer in dispute: the dictatorships, which largely owe their rise to power to capitalist support, cleverly and unscrupulously profiting by the perplexity of the money power in face of the mounting tide of Socialism and of the power of the working-class organizations, have not denied that capitalism is on its death-bed. It has become fatally enmeshed in a network of contradictions of its own contrivance.

Karl Marx foresaw this stage when he analysed the laws of economic phenomena in his Kapital; perhaps he failed to foresee how quickly it would be reached. This is comprehensible, since the curve of scientific and technical progress is a parabola, with constantly growing acceleration. The war of 1914-18, moreover, greatly increased the acceleration; it has been one of the principal factors of the approaching end of capitalism. It has been suggested that the concentration of capital in trusts or in the hands of governments is simply a modernized, rejuvenated form of capitalism, but there can be no question any longer that the idea of planning, of directed economy, is fundamentally opposed to capitalism and is incompatible with its very existence. It is difficult to suppose that trusts can continue in the long run to dominate the economic systems of advanced countries, since they provoke reactions on the part of the State itself in the most highly trustified country in the world, the United States.

Conversely, a return to capitalist psychology has been seen by some people in the fact that the Russian Revolution has softened its economic policy in the course of years, permitting the individual certain rights of property, and no longer treating all its citizens on a basis of equality in regard to their material needs, as was done at the outset of the period of “ war Communism”. But it is forgotten that in times of social disaster and war all nations adopt measures in restriction of the most sacred rights of the individual. It is absurd to suppose that Socialism ever envisaged the imposition of restrictions, in the midst of the abundance it implies, out of simple love of an abstract principle; what it does set up as a doctrine is that men shall not be allowed to exploit their fellow-men, and this is precisely what distinguishes it from capitalism.

Karl Marx studied capitalism above all from the point of view of the scientist. After analysing it he expressed the opinion that this form of the life of human societies is doomed to failure by the logic of facts, and that it will have to disappear to enable mankind to exist. Then, as a politician, he sought means of accelerating that inevitable process and of rendering its accomplishment less painful. His action and doctrine have been baptized “Marxism”, and little by little that theoretical denomination has become a slogan of political struggle. When we speak today of “Marxism”, we must be clear as to our meaning. Primarily Marxism is the work and doctrine of Marx; but its secondary and principal meaning comprises today the whole collection of economic and political theories of his disciples, which underlies the programme of the Labour parties; .thirdly and finally it is the slogan which Fascists shout in pure demagogy to designate the democratic idea in general. The slogan is disingenuous; most of these so-called “anti-Marxists”, if driven into a corner, have to admit that they have not read a line of Marx and know nothing about his ideas.

Marx was one of the first to attempt to view economic and sociological problems from the angle of the science of his time; this will make his work immortal, as is that of Darwin, who set the idea of biological evolution on a firm basis, and greatly contributed to its spread. But even “Darwinism”, that is to say, Darwin’s attempt to find an explanation of the facts of evolution, and to define the factors that determine its course, no longer holds against present-day scientific criticism; similarly some of Marx’s ideas are no longer in conformity with the contemporary state of science: it would never have been imagined in his day that economic sociology was in reality a branch of biology, and that it must therefore employ its methods of analysis and synthesis in that capacity. Moreover, Marx himself, with his insistence on the necessity of a scientific Socialism, would have been horrified at the present-day exegetical battles that rage now and then over his doctrine, treating it as a sort of infallible Bible, instead of what it was, an attempt at explanation from the point of view of the science of his day.

An error for which Marx is less responsible than his commentators and the modem prophets who have given “Marxism” its new aspect, lies in regarding human behaviour entirely from the materialist point of view, that is to say, as proceeding from what we have called the second (nutritive) instinct; according to their ideas, economic factors count above all else. Even from their own point of view, that of “scientific materialism”, we consider that their theory is untenable. Our position is itself the outcome of positive, experimental scientific research. Human behaviour is usually a complex phenomenon in which there are other factors besides the economic ones, factors actually of greater force and importance, which nevertheless are purely physiological, and therefore material.

This is confirmed by recent economic and sociological experience. The economists declared, for instance, at the outset of the war of 1914-18, that it could not last longer than a few weeks, for if it did it would bring a total collapse of the economic structure of the world. It has been stated that the Bolshevist experience in Russia was economically irrational, that the five-year plans were an absurdity, that hunger and economic difficulties would prevent their realization. Yet we have seen a people enduring for years the harshest material sacrifices, and, far from succumbing, it has ultimately benefited. The reason was that the Soviet leaders, ignoring the predictions of Marxist theorists, learned to play on certain strings of the human soul which are independent of economic influences, and secured reactions which enabled the “miracle” to be performed. Our modern scientific data show that the miracle was no miracle, but an entirely natural physiological effect. Here popular propaganda played a decisive part. The same is true of Germany: humorists have declared, indeed, that all that is needed to give the Germans a sense of happiness and well-being is to play military music once a week and make the people march to it.”

- Serge Chakotin, The Rape of the Masses: The Psychology of Totalitarian Political Propaganda. London: George Routledge & Sons, 1940. p. 263-267

#capitalism#capitalism in crisis#karl marx#marxism#world war 1#theoretical marxism#scientific materialism#soviet union#collapse of capitalism#the great depression#serge chakotin

1 note

·

View note

Text

Plekhanov's scientific socialism

'A cardinal tenet of the revolutionary movement up to the early 1890s had been that Marx's teaching on historical evolution did not apply to Russia, whose communal institutions would enable it to build a socialist society without going through the stage of "bourgeois capitalism" and without creating an alienated and poverty-stricken proletariat, such as had been seen in Britain, the United States, and, more recently, Germany.

The first revolutionary figure to question this doctrine was Georgii Plekhanov, the man who had rejected terrorism [at a congress of Zemlia i Volia] in 1879. In a series of studies written on emigration in the 1880s he argued that Russia had already entered the era of bourgeois capitalism and was creating a modern industrial system, including a proletariat of the kind Marx had described. As for the commune, it was only the remnant of a dying economic system, already being destroyed by the pressures of capitalism. Only when capitalism had exhausted its potential and the proletariat had expanded and matured would revolution become possible: to try to bring it about before then was to act in a premature and irresponsible manner.

Plekhanov believed that only his version of Marxism had the right to be called "scientific socialism," and he disdainfully wrote off the revolutionaries of the period up to 1881 as narodniki, "the people worshippers." Though translated more respectfully as "populists," the word is still commonly used for all non-Marxist Russian revolutionaries. His assertions launched a lively debate in the 1890s between the "populists," who held that Russia had its own distinctive path of social evolution, and the "Marxists," who believed that it would follow the same road as other European countries, though with some delay caused by its relative backwardness.

Plekhanov's view appealed to those who liked to regard themselves as "scientific" and to those who wished to see themselves as part of an international scene, to escape from the claustrophobia of insisting on Russia's distinctiveness. But there was a serious drawback to his doctrine: if Russia was to wait till it had a numerous and "mature" proletariat, then revolution would have to be delayed for decades, at least. In the meantime the revolutionaries would be obliged to welcome the growth of capitalism and of bourgeois liberalism as progressive developments. Most revolutionaries were not so patient or understanding.'

Russia and the Russians, by Geoffrey Hosking

#plekhanov#marxism#communism#socialism#russian socialism#revolution#historical materialism#scientific socialism#marx#internationalism#narodniki#populists

0 notes

Text

The first book I am reading is "Socialism: Utopian and Scientific," by Frederick Engels. I will share my thoughts on the work tomorrow. In the meantime, if anyone has any thoughts on the text, please let me know.

#frederick engels#marxism leninism#marxism#socialism#communism#growing left#marxist#socialism: utopian and scientific#theory

0 notes

Text

an introduction of sorts

so i'm setting up this blog as a side place for me to document my journey into marxism and becoming a marxist - especially as someone who is transsexual and has my roots in social justice firmly from my own lived experience. I have worked in activist spaces since I was around 16 - ranging from identity to environment - but only recently have I delved into marxism. and i've kind of thrown everything i've got into it. its my new hyperfixation, new special interest even.

i had considered staying on at university to do a masters but i didnt have a direction. i now know i want to study marx's theory of alienation and apply it with the right clinical psychological analysis that it deserves. our current society is suffering from a pandemic level crisis of mental health. it is as broad as day - but yet class consciousness is consistently being thwarted every single day due to the alienating nature of capitalism as it exists within the class system we are being forced to live under. the masters im considering taking is political psychology.

as part of my marxist journey, i have been a part of a reading group. we have covered

marxism vs idpol (day session)

the communist manifesto

state and revolution

dialectical materialism (article)

we are scheduled to read value, price and profit. whether i can read this by sunday remains to be seen. uni is kicking my neurodivergent arse.

i'll do a proper introductory post soon describing more about me. but this is suffice for now. im gonna try and keep this blog very casual and low maintenance - but i strive to update it with notes from certain readings and articles to inspire me to document and learn more.

#dialectical materialism#scientific socialism#marxism#marxist#engels#lenin#marx#communist#communism#socialism#socialist#leftist#radical leftist#radical leftism#imt

0 notes

Text

Socialism: Utopian and Scientific- Friedrich Engels

This was originally the first three chapters of a larger work- Anti-Duhring, published in 1878.

The initial idea was that Engels would write a more approachable condensed version of Marx's larger Das Kapital, which was a difficult read.

1 The Development of Utopian Socialism

Engels outlines the development of earlier forms of socialism by Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Robert Owen.

Engels writes that the 18th century French philosophers saw reason as the ultimate answer to the betterment of society. They thought that history prior to the enlightenment had been one long age of unreason, and if only universal reason were applied, the problems of humanity would disappear. Despite the promises of the enlightenment, Engels sees the actual application of these 'inalienable rights of man' as being nothing more than further entrenchment of the bourgeois.

None of the three utopian socialists, says Engels, represented the interests of the proletariat. They sought the emancipation of all humanity, not just workers. Their mistake was to attempt to apply enlightenment values of reason and justice, rather than deal with what Marxists saw as the real problem- class antagonisms.

Engels notes that the French revolution tried installing enlightenment values, but ended in the Reign of Terror, therefore the application of enlightenment reason to society was a failure. Engels ignores the American experiment, which has been successful, and focuses on the French revolution in order to appeal to facts that support his assertion.

There had been Utopian socialists that had tried experiments in small scale communism. Engels sees their theories as crude responses to crude conditions. Capitalistic production had not developed enough to bring about the necessary conditions for revolution, so the utopian socialists' designs were pure fantasies.

The first was Henri de Saint-Simon, a son of the Revolution. While the revolution was a victory by the third estate (the common people), that victory soon showed itself to be essentially bourgeois in effect. The French revolution was an antagonism between the idlers (aristocracy and all those that earned without working) and workers. The idlers had lost the capacity to lead, as the revolution had proven. The new leadership would be a union between science and industry and a reformed new Christianity. But these were all lead by the bourgeois.

Second was Charles Fourier, who was a critic of modern society and wrote of the moral and material bankruptcy of the bourgeois. He contrasts the reality with the promises made by those promoting reason. He divided history into 4 stages: savagery, barbarianism, patriarchate, and civilization (which Engels says it the same as bourgeois society). He says these move in a vicious circle, constantly reproducing.

Third was Robert Owen, a Scottish cotton mill owner who had noted the conditions of the working class, and implemented humane conditions in his factory as a response. The result was a model colony. But even then Owen realized his workers were still essentially at his mercy, and he recognized that, while relatively better off, his workers were still far from being allowed rational development in their character and intellect.

While the factory had been highly profitable, he was still paying proprietors on the capital they laid out, meaning the workers were still not profiting as they should from their labor.

He drew up plans for more widespread reform in Ireland, but always based in the practical costs.

But as his ideas developed to a more general communism; including private property, religion, and marriage, he knew that he would be socially excommunicated. His attempts at founding such a colony in America ruined him. Engels claims it was bourgeois ostracization that caused the failure. But New Harmony, Indiana, the colony he was using to implement his ideas, failed after only two years due to failed expectations, in-fighting, and commercial failure. They had lofty ideals, but couldn't clearly address how to make the community function.

Engels says Socialist thought has largely been patterned after these utopian. To these, socialism is the expression of absolute truth, reason, and justice, and only has to be discovered in order to conquer the world. But, says Engels, to make a science of socialism, it had to first be placed upon a real basis.

2 Dialectics

Engels says Hegel had the highest form of reasoning: dialectics. Aristotle had long ago analyzed the essential forms of dialectic thought1. The more modern philosophers used it, but in metaphysical mode.

The essence of dialectic thought is to consider nature, the history of mankind, or our own intellectual activity. We see an endless entanglement of relations and reactions, permutations and combinations- basically everything in its natural state of flux. Things are not static, but ever changing. We see the whole, and then the individual parts in the background. Heraclitus describe it as: everything is and is not, for everything is fluid, is constantly changing, constantly coming into being and passing away.

Engels writes that while true, this isn't sufficient. For a long time, we needed more knowledge of the natural and historical material with which to do analysis. As we've enlarged our scope of knowledge, there is more to work with, but the habits we gained over time was to study things in isolation, not in connection with the whole. This habit was transferred to the metaphysical realm. Ideas were isolated, to be considered apart from each other- and they become rigid, fixed.

This seems to be common sense, but it forgets that things are constantly in motion. Even cause and effect, which is useful applied to individual cases, begins to blur in the big picture of processes. But these processes don't enter into metaphysical reasoning.

Dialectics on the other hand comprehends the totality.

Nature is the proof of dialectics. It doesn't move in a perpetually recurring cycle, but in a historical evolution. Darwin showed this.

An exact replication of the universe, its evolution, and its consequences for man can only be obtained through dialectics and its regard of fluidity.

The importance of Hegel is that the world and history is seen as process. Now we need to follow the march of this process and find the inner law running through it. Hegel didn't solve the problem, but he propounded the problem. No single individual will ever be able to solve it.

The old materialism saw the world as essentially irrational and disconnected. The new materialism sees the process of evolution and seeks to discover the laws at work.

Engels goes on to assert that the facts laid out in the dialectic examination of history reveal that ALL past history was the history of class struggles. These warring classes are always the products of modes of production and exchange- or, economic conditions.

I don't know if Marx gave evidence of this assertion in Capital, but Engels doesn't here, he just asserts it. In fact, this most crucial fact, underpinning nearly all Marxist thought, seems, on the face of it, to be not only not true, but not even possible.

If I were to guess at why Marx thought this, I'd guess he is only considering history from a much later date- say the middle ages on. But even now, smaller tribal groups have councils- leadership that settles disputes. Disputes arise, I would believe, because of human nature and our innate self-interest, not because of class conflict. Class conflict could never grow until society grew large enough. Marx seems to recognize that his assertion doesn't count for prehistoric times, but even today there are conditions where tribes and individuals within them have conflicts that don't have anything to do with class antagonisms. So this fundamental assertion of Marx seems to me on the face of it- wrong.

Engels says: Now that history is understood dialectically, and a materialistic understanding of history is granted; it was understood that man knows by being, rather than being by his knowing.

From here, socialism is the necessary outcome of the struggle between the two historically developed classes.

Again, Marx and Engels assert that these things are true. They claim they are rigidly scientific in their analysis, and therefore, they can't be wrong about the hypothesis. But oddly enough, while their dialectical approach should lead to more nuanced understanding, they seem exceptionally narrow and rigid in their conclusions. They took Darwin's early work and accepted that a materialistic understanding of history was granted. But the scientific method itself should have taught them they can never attain absolute certainty. One must always be open to later facts that would shed further light on the subject.

And even accepting this, it's laughable now to read that socialism was thought to be the necessary outcome of the class antagonisms they saw. Clearly, 170 years later, it hasn't come close to materializing. Yet they were religiously certain in their conclusions.

Engels finishes the section by noting the old utopian socialism condemned capitalism as bad, but couldn't explain it. The new socialism understands capitalism and its exploitation, and by the discovery of surplus value, shows us exactly where that exploitation occurs, and how to end it. With these discoveries, socialism became a science. The next thing was to work out all its details and relations.

3 Historical Materialism

Engels says the materialist conception of history starts from the proposition that production and exchange are the basis of all social structure. The final causes of all social changes are due to changes in modes of production, not in better insights into truth and justice. The perception that social institutions are unreasonable and unjust are due to changes in production and exchange.

Again, no evidence is given for these assertions, but I'm inclined to accept some of them, since they seem at face value to be true. I'm not sure if all social changes are due to changes in modes of production. It seems to me that war and conquest were probably a bigger factor in this than modes of production. Though I suppose since war was an acceptable way of increasing wealth, its consequences could be termed a change in the mode of production....

In the middle ages, the instruments of labor were the instruments of individual workmen. So the labor and output belonged to the producer himself.

One of capitalism's mechanisms was to transform this individual labor of an entire product, into a series of tasks, each done by different workers. This increased production, but it meant the end product no longer belonged to any one workman. Engels says, instead, the capitalist appropriates the end product.

And his appropriated product is always exclusively derived from the labor of others.

This new mode of production is where the entirety of social antagonism lies. The contradiction between socialized production and capitalistic appropriation manifests itself in the antagonism between proletariat and bourgeoisie.

Certainly, this could lead to antagonisms. But is it necessarily so, as the Marxists assert? I don't think so.

Yes the capitalist sells the commodity produced by labor. But while Marxists term this appropriation, the capitalist pays the workers for their labor. It isn't just taken from them. Marx seems to make a huge deal out of the fact that workers now work on a specialized part of a shoe, rather than one individual making them entirely from scratch. But so what? I've been a freelance worker, and it can be very hard to survive all on your own. Whereas if you work in a larger entity, the entity carries all the responsibility and pays you for your work whether the product sells or not. Again, these are basic assumptions of Marxism that seem wildly misplaced.

Engels writes: In medieval society, production was directed towards satisfying the needs of the individual. Only when a family began to produce more than it needed, would the produce become a commodity. But production of commodities on this scale was restricted, narrow, stable and local.

As production of commodities increased, the producers became wage laborers. Whenever the capitalist organization of labor took place in an industry, it displaced all others. Modern capitalism, at a global scale, has made the antagonism between bourgeois and proletariat a universal struggle.

Engels believed this antagonism was innate in capitalism and it was unable to do anything else. Capitalists would be forced by the demands of the market to continually use better machinery until finally the workers themselves would be displaced. Machinery is the ultimate tool that would tear the means of subsistence out of the hands of the working class. The machine then is the tool of subjugation.

This ultimately will lead to the consumption of the masses and the destruction of the home market.

The working class rises up in the demand that they be treated as a social production force.

This assertion that capitalism would inevitably end up in disaster clearly proved to be wrong. The arguments would seem to be sound, especially in Marx's day, but complex systems rarely prove to be so easily read. In fact, some law of mitigating factors meant that continual adjustments were made until capitalism avoided the dire predictions Marx made. Did the Marxists then use Hegelian dialectic to readjust their models with continually more nuanced understandings? Nope. They have religiously held on to these pronouncements long after they've proven false. They continue to read Marx as if his writings were holy writ, incapable of being wrong.

Engels says these active social forces, once understood, can be harnessed for the good. Recognizing the real nature of productive forces, it can be turned to the good of the community when the proletariat seizes power and turns the means of production into state property. The proletariat then also abolishes class distinctions and ultimately even the state itself, since the state is only an institution to protect the bourgeois. When the state becomes the real representative of all of society, not just the bourgeois, then it is no longer necessary. When economic antagonisms are removed, there is no longer anything to repress. Government gives way to administration.

Engels believed that the time was now (1877) that the capitalist system was finally breaking. It couldn’t happen before capitalism reached the necessary state of development, but once that happened, its demise was imminent.

As socialism took root, the means of production would be used for the betterment of the community, not just the wealthy, and even waste and devastation of productive forces would be eliminated. As production is turned towards the systematic good through definite organization, the struggle for existence disappears. Finally man emerges from subsistence into truly human existence. All of the conditions of life that ruled over man, are now subject to man.

Footnotes:

1. Socrates Dialectic method was to show argument by a conversation between Socrates and others. Positions would be defined, countered, and refined. Hegel thought the older dialectical method resulted in either a position being null, or skeptical, which can only approximate truths, but falls short of genuine science. But Hegel thought reason necessarily generated contradictions. In his epistemology, opposing sides are different definitions of consciousness and of the object that consciousness is aware of or claims to know. The dialectic process should lead from simpler understandings to more sophisticated.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The contradiction between dogmatism and revisionism can only be resolved through the combination of scientific creativity and staunch communist principles. Theory must be applied creatively, but always toward building communism.

#socialism#communism#Marxism#Marxist theory#dogmatism#revisionism#opportunism#dialectical materialism#scientific socialism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

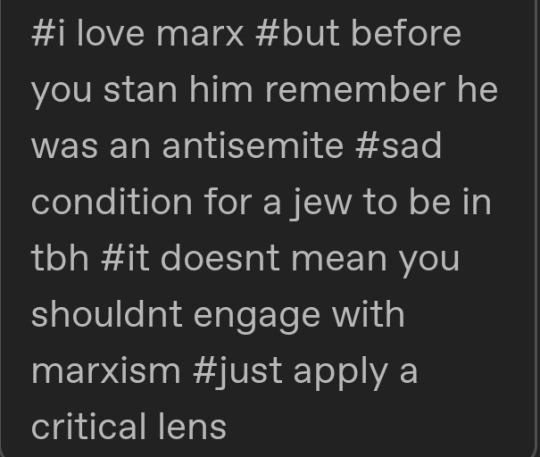

1. Marxism is not a religion or celebrity cult where people "stan" Marx and the validity of his theories is proven by his exemplary personal life, it's a science of political economy that's been used, adapted, critiqued, and modified by billions of people for almost two centuries. It's called "Marxism" for the same reason it's called "Darwinism" - he's the guy that laid the theoretical foundations of a scientific theory.

2. Presuming this is about "On the Jewish Question" (one of Marx's earliest writings which predates The Communist Manifesto and indeed his own formulation of Marxism), the myth that it's a virulently antisemitic text has been repeatedly debunked (short version from Jacobin, long version from Jewish socialist Hal Draper). He was in fact arguing for the emancipation and granting of citizenship rights to Jews within the overwhelmingly antisemitic climate of early 19th century European politics.

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

niceys positive anon!! i don't agree with you on everything but you are so clearly like well read and well rounded that you've helped me think through a lot of my own inconsistencies and hypocrises in my own political and social thought, even if i do have slightly different conclusions at times then u (mainly because i believe there's more of a place for idealism and 'mind politics' than u do). anyway this is a preamble to ask if you have recommended reading in the past and if not if you had any recommended reading? there's some obvious like Read Marx but beyond that im always a little lost wading through theory and given you seem well read and i always admire your takes, i wondered about your recs

it's been a while since i've done a big reading list post so--bearing in mind that my specific areas of 'expertise' (i say that in huge quotation marks obvsies i'm just a girlblogger) are imperialism and media studies, here are some books and essays/pamphlets i recommend. the bolded ones are ones that i consider foundational to my politics

BASICS OF MARXISM

friedrich engels, principles of commmunism

friedrich engels, socialism: utopian & scientific

karl marx, the german ideology

karl marx, wage labour & capital

mao zedong, on contradiction

nikolai bukharin, anarchy and scientific communism

rosa luxemburg, reform or revolution?

v.i lenin, left-wing communism: an infantile disorder

v.i. lenin, the state & revolution

v.i. lenin, what is to be done?

IMPERIALISM

aijaz ahmed, iraq, afghanistan, and the imperialism of our time

albert memmi, the colonizer and the colonized

che guevara, on socialism and internationalism (ed. aijaz ahmad)

eduardo galeano, the open veins of latin america

edward said, orientalism

fernando cardoso, dependency and development in latin america

frantz fanon, black skin, white masks

frantz fanon, the wretched of the earth

greg grandin, empire's workshop

kwame nkrumah, neocolonialism, the last stage of imperialism

michael parenti, against empire

naomi klein, the shock doctrine

ruy mauro marini, the dialectics of dependency

v.i. lenin, imperialism: the highest stage of capitalism

vijay prashad, red star over the third world

vincent bevins, the jakarta method

walter rodney, how europe underdeveloped africa

william blum, killing hope

zak cope, divided world divided class

zak cope, the wealth of (some) nations

MEDIA & CULTURAL STUDIES

antonio gramsci, the prison notebooks

ed. mick gidley, representing others: white views of indigenous peoples

ed. stuart hall, representation: cultural representations and signifying pratices

gilles deleuze & felix guattari, capitalism & schizophrenia

jacques derrida, margins of philosophy

jacques derrida, speech and phenomena

michael parenti, inventing reality

michel foucault, disicipline and punish

michel foucault, the archeology of knowledge

natasha schull, addiction by design

nick snricek, platform capitalism

noam chomsky and edward herman, manufacturing consent

regis tove stella, imagining the other

richard sennett and jonathan cobb, the hidden injuries of class

safiya umoja noble, algoriths of oppression

stuart hall, cultural studies 1983: a theoretical history

theodor adorno and max horkheimer, the culture industry

walter benjamin, the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction

OTHER

angela davis, women, race, and class

anna louise strong, cash and violence in laos and vietnam

anna louise strong, the soviets expected it

anna louise strong, when serfs stood up in tibet

carrie hamilton, sexual revolutions in cuba

chris chitty, sexual hegemony

christian fuchs, theorizing and analysing digital labor

eds. jules joanne gleeson and elle o'rourke, transgender marxism

elaine scarry, the body in pain

jules joanne gleeson, this infamous proposal

michael parenti, blackshirts & reds

paulo freire, pedagogy of the oppressed

peter drucker, warped: gay normality and queer anticapitalism

rosemary hennessy, profit and pleasure

sophie lewis, abolish the family

suzy kim, everyday life in the north korean revolution

walter rodney, the russian revolution: a view from the third world

#ask#avowed inframaterialist reading group#i obviously do not 100% agree with all the points made by and conclusions reached by these works#but i think they are valuable and useful to read

925 notes

·

View notes

Note

You can't call yourself a Marxist and be ideologically opposed to trans people, those are incompatible modes of thought.

gender identity theory is incompatible with the Marxist scientific method.

believing your thoughts determine your reality is a product of subjective idealism. Marxism is not idealism but dialectical materialism, there is an objective reality and objective material conditions from which human consciousness stems. we exist as material, physical beings rather than immaterial conscious spirits. subjective consciousness is subordinate to and dependent upon the material world.

the correct Marxist position is not "i feel i'm a woman therefore i am a woman" but "i am objectively female, and this makes me a woman".

#marxist feminism#marxism#gender abolition#gender identity#transgender#gender#dialectical materialism#marxism leninism#marxist leninist#marxist theory#original posts

697 notes

·

View notes

Note

im confused about this thing people say about heinrich, does "worldview marxism" = structural marxism?

not really. worldview marxism is much broader and refers to a tendency among marxists generally to think about their beliefs as having more explanatory power than they do, so that the analysis of a social system becomes a much bigger framework for understanding all of reality etc etc etc. so, like people who make a fuss about dialectics as the best way of approaching natural science. what this typically amounts to is imposing an empty dialectical method onto phenomena where it's not adequate, but the facts are made to fit the assumptions so that everything is reduced to some stupid set of "contradictions" and the more of them you can name off in explaining your account of [whatever], the more scientific your marxism is.

heinrich's point is that this actually, in some sense, naturalizes the terms of the critique and makes it collapse in on itself, turning it from a historically specific critique of a mode of production oriented toward building a radically different world into a transhistorical set of laws that we are bound to and which, in most marxisms, can't even account for the subjective and revolutionary element.

76 notes

·

View notes

Note

so i prommy im showing up in good faith, i saw it cuz i follow you but like, re: moral stances, iget what people mean when they say x marxist stance is not a moral one or y critique is not moralistic, but that dont mean that morals are absent right? like i can say that quality of life in a place is getting worse because of xyz reasons without moralistic reasoning, but then i would go ”and thats bad” then thats a moral stance, right? im assuming youre working off a different definition of ’morality’ bc that would make the most sense, so what would that definition be? like idk how even the most scientific marxism would be able to abstain from any moral stances because then it wouldnt be political

fundamentally Marxist analysis is made from a scientific perspective, where we look at the world as it actually is regardless of morality; we recognize that morality is a human creation that is ontologically dependent on material forces rather than preceding them; we don't see it as useful to look for Good and Bad People, for whose Fault something is on a moral sense, etc. it doesn't matter whether the capitalist's heart is full of sin or misguided righteousness, it doesn't matter how virtuous we can claim ourselves to be as individuals, etc. the material world is the basis, ideas and morality develop out of it. in the political stage we do make a value judgement in saying we support the resolution of the contradictions of capitalism through advancing the interests of the proletariat. this is not an Objective Morality though, we must understand even ourselves and our motivations as being determined by material forces. morality has a place in marxism in the form of proletarian morality as long as we understand that the reason the proletarian has this set of ethics is because it advances their interest as a class rather than being a feature of the fabric of reality. we support marxist politics not through free will and a virtuous soul but because we have internalized a proletarian morality that develops as the superstructure of material phenomena. just like bourgeois morality exists fundamentally as a tool of capitalism, proletarian morality forms as a justifying ideology for the interests of the proletariat as a class. morality is a social technology for facilitating social cohesion and advancing the interests of the ruling class beyond purely selfish and coercive incentives

141 notes

·

View notes

Note

While broadly speaking Religion can play a revolutionary in class struggle, the particular nature of Marxism-Leninism makes it largely incompatible with Religion. Marxism-Leninism is a Materialist Ideology while Religion is by its nature Idealist. There's a quote from Dialego's Philosophy and Class Struggle I think is relevant /1

consider:

I mean, I'm more lenient with religion than most marxists mostly because it can play a role in advancing socialism but the separation of religion as a force of material political-economy comes with the dissolution of religion as an institution and the general improvement of material conditions. As livelihoods improve, people will turn away from religion as an institution until it becomes either something as mundane as "personal philosophy" or is abandoned all together. From a theory perspective, religion, being an immaterial, abstract dogma is contradictory and antagonistic to scientific socialism which is based off of materialism and dialectics (not to say some religions don't have dialectics, but those are significantly rarer).

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really need to get more into marxist god-building. As soon as I started reading a review of Lunacharsky’s writings on how Marxism evokes religious emotion and is basically scientific theology it was like discovering what i had believed but didn’t realise it

#also have been pretty compelled by his discussion of the role of religion in socialism#like in terms of capturing the ritual and social emotion that religion evokes for the purposes of uniting the working class#it resonated a lot with the history I’d read of the Haitian revolution and the role religion played in slave organising#like obviously religion plays a massive role in most conflicts but using it as a mobilising force for proletarian movements resolves a lot#of my confusion/uncertainty about religion in a socialist society#anyway I need to read a lot more I’m not very far into it#hoping maybe I can do a bit more reading in the summer but I have comp preparation then. augh#book club

62 notes

·

View notes