#source: antony and cleopatra

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Gonta: I wish you all joy of the worm.

Source: William Shakespeare (“Antony and Cleopatra”)

#incorrect quotes#danganronpa#drv3#gonta gokuhara#source: william shakespeare#source: antony and cleopatra

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

"cleopatra movie starring zendaya as cleopatra and timothee chalamet as octavian" i was having a good day and now i have an anger headache

#personal#i like zendaya and chalamet as actors and they have good chemistry#and i'm honestly fine with anything that focuses on the relationship cleopatra and octavian had with each other specifically#i think it's underdiscussed and a great source of drama and narrative storytelling#but not like this#for one i will say it until i'm blue in the face: cleopatra was white as bread. palest woman to have ever lived in egypt.#you know what with the THREE CENTURIES OF ONE GREEK FAMILY INBREEDING OVER AND OVER THAT LED TO HER CONCEPTION#for two: why are octavian and cleopatra gonna be the same age she was a decade older than him#that's important!#she was an adult in a relationship with his great-uncle when they first met in rome and HE was a teenager barely a year into adulthood#(by roman standards)#like she can't be his age and have a relationship with caesar#and even more importantly him being younger is probably a key part in why she might have underestimated him#along with listening to antony but that man was just stupid#it's a recurring theme in octavian's early career: the people around him were older and because he was young he wasn't taken seriously#until he was at their doorstep burning down their house and killing everyone they knew and by then it was too late#i cannot believe hollywood is apparently finding it hard to cast a white woman who can play midtwenties to early forties!!!#denis i know you like these two but pls just executive produce and give the project over to me and let me overhaul it#(where i then scrap the cleopatra focus and make it either a three way show focusing on cleopatra octavian and herod)#(or i just get to make the octavian biopic show i've had in my head for like two years)

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marble portrait of Julius Caesar.

Roman, around AD 50. From the Sanctuary of Athena in Priene, modern Turkey.

The head has been burnt and is badly damaged, with the proper right side and back of the head missing. The features of the portrait, in particular the hair and the profile, correspond very closely to those on other images of Julius Caesar. Caesar, one of Rome's most capable generals, as demonstrated by his conquest of Gaul in the 50s BC, became embroiled in the civil strife that accompanied the disintegration of the Roman Republic. In 48 BC he crossed the River Rubicon, took Rome and effectively became the first citizen. His presumed desire to abandon the Republic as a form of government and return to monarchy led to his assassination in 44 BC. The ensuing civil wars culminated in the defeat of Mark Antony and Cleopatra by Octavian, Caesar's adopted son, who as Augustus ushered in the Empire.

The head was found, along with other pieces of sculpture, including a head of Claudius, on the floor of the cella (main cult room) of the Temple of Athena, during excavations in 1868/9. The sanctuary was dedicated to Athena - specifically to Athena Polias, literally 'the guardian of the city'. An inscription commemorating the dedication of the temple by Alexander the Great is preserved in The British Museum, as are fragments of the colossal cult statue of the goddess. In the Roman period the sanctuary was rededicated to Athena Polias and Augustus, reflecting the new importance of the imperial cult throughout the empire. Special buildings were erected or, as here at Priene, existing sanctuaries and temples were adapted to accommodate the statues and busts of the emperor, his family and ancestors. Caesar's family claimed direct descent from Venus through Ascanius (Iulius) the son of Aeneas, the Trojan prince who brought his people to Italy. The worship of the imperial family was fundamental to the new imperial order, and it was the unwillingness of the Christians and Jews to comply in this which led to their persecution.

Source

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

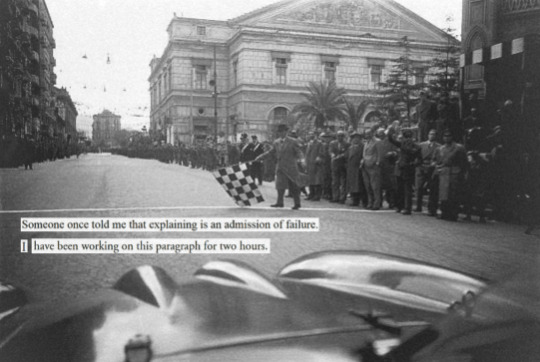

um. the carinae joke but it's house of leaves

Antony & Cleopatra // Vellius Paterculus // Daily Life In Ancient Rome, Jérôme Carcopino // Map of Carinae, Rodolfo Lanciani // 13th Philippic // Magnus Pius: Sextus Pompeius and the Transformation of the Roman Republic, Kathryn Welch // Seneca // Florus // this picture I cannot find the source of // Sextus Pompeius and the Res Publica, Kathryn Welch // Cassius Dio // An Island Amid the Flame: The Strategy and Imagery of Sextus Pompeius, Anton Powell

#fucking around with. idk graphic design? ig?#anyway please remember that i am stupid and know nothing about academia 👍#sextus pompey

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

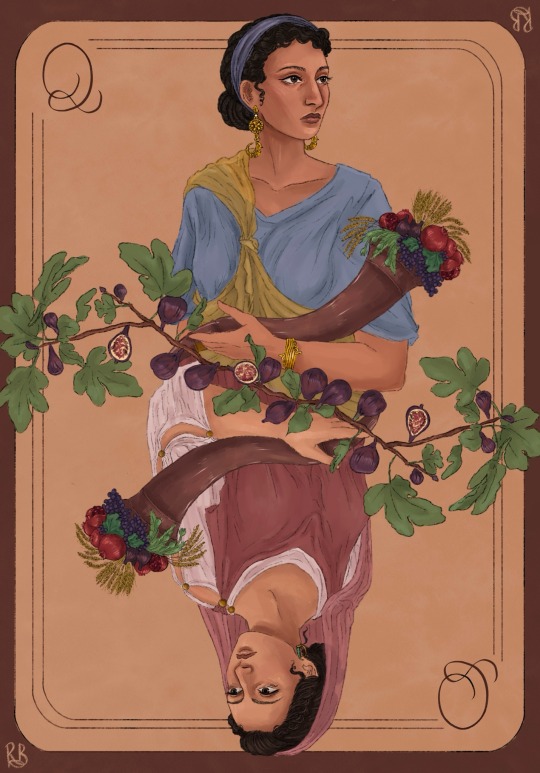

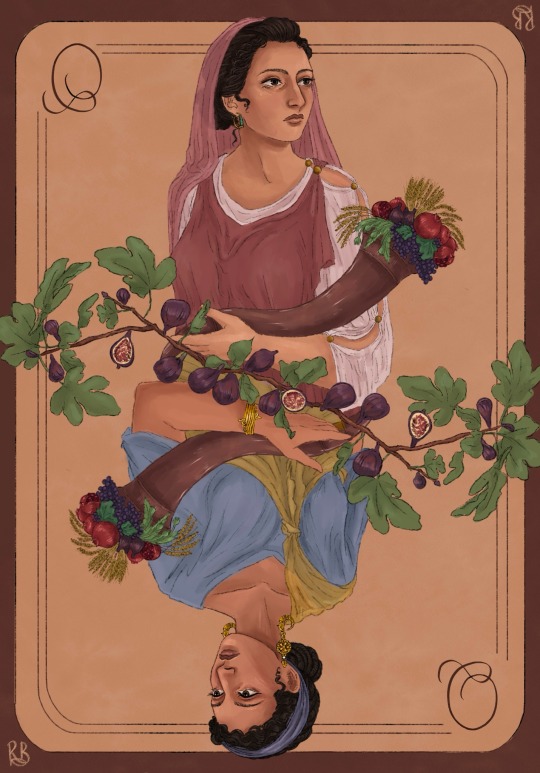

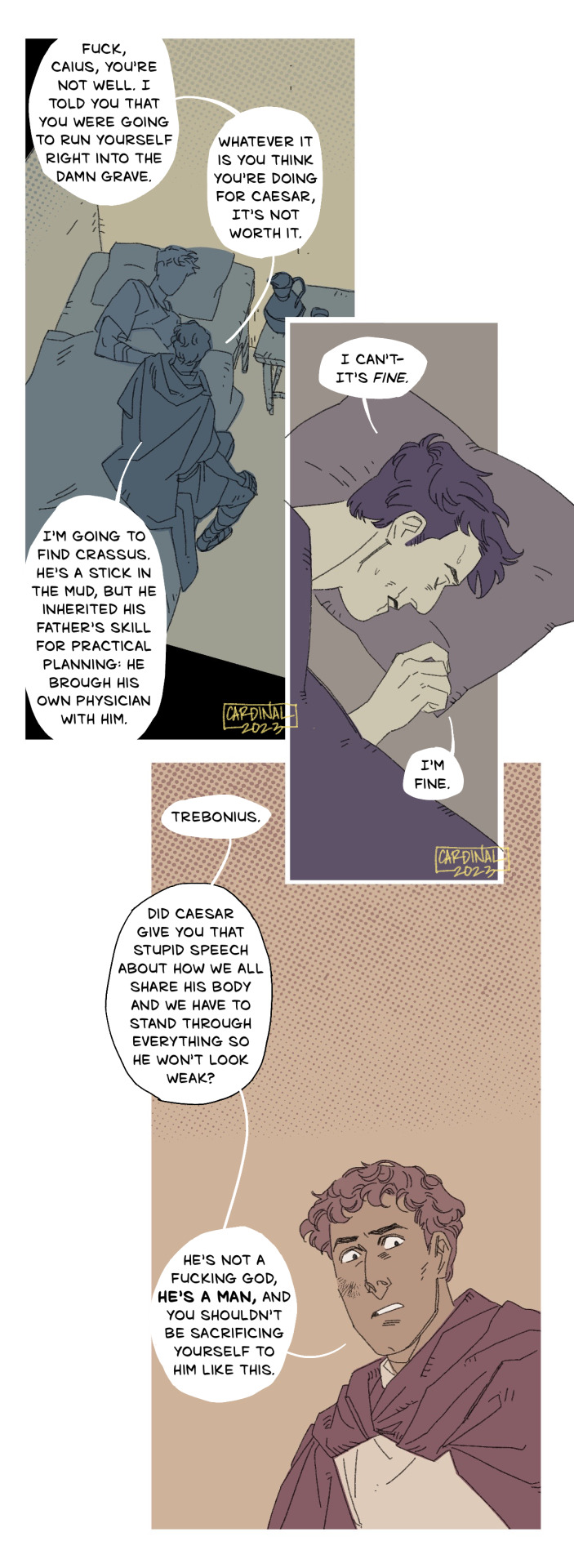

Finals took me out for a bit, but I’m back, and I finally finished!!! Here’s Cleopatra and Livia in all their glory :)

Parallel Lives

To me, Cleopatra VII and Livia Drusilla are two sides of the same coin. They were born exactly ten years apart (Cleopatra in 69 BCE and Livia in 59 BCE), and were the female rulers of two of the most prominent Mediterranean powers of their time. Their families were deeply entwined: Julius Caesar was the father of Cleopatra’s son and Livia’s (adopted) father-in-law; Mark Antony was Livia’s brother-in-law through his marriage to Octavia; when Augustus conquered Egypt, he had Cesarion killed because he was a threat to Augustus’s apparent right to rule.

Both women grew up in a time of civil war and ended up on opposite sides of their families. Cleopatra openly fought her brother Ptolemy XIII and her sister Arinoe VI. Livia’s father and brother died fighting for Brutus and Cassius at Philippi. Her first husband sided with Fulvia and Lucius Antonius when they fought Augustus.

Both of them have been misrepresented by ancient sources and modern media.

Augustus’s propaganda hinged on the presentation of himself as a proper and modest Roman returning to tradition after so much civil war (other than the autocratic ruling ofc). He presented Livia as the ideal and perfect Roman matron, chaste, modest, and pious. He presented Cleopatra as the opposite. She represented the extravagance and backwardness of foreign monarchs. Augustus presented her as domineering over Antony, a reversal of the proper order (his slander of her was largely slander of Antony after all). And although Augustus publicly looked down on Egypt, he adopted many elements of Egyptian monarchy into his dynasty, such as the association of monarchs with gods—as Livia was associated with Ceres, Magna Mater, and Venus, Cleopatra mostly associated herself with Isis (who shares an origin with Venus).

Both were accused by historians of poisoning family members—Cleopatra her brother Ptolemy XIV among others, and Livia Augustus as well as a number of his heirs.

In modern media, Cleopatra is often seen as an over-sexualized seductress, Livia as a conniving and manipulative wife and mother.

Whether or not they did any poisoning, they were both incredibly intelligent and fascinating women and I love both of them a lot.

There are some of motifs in the drawing I want to point out:

- Cleopatra is wearing an Isis knot (the top layer of her dress), a common feature found in depictions of Ptolemaic queens that associates them with the goddess Isis

- She is also wearing a simple cloth diadem as often seen in depictions of Alexander the Great and all the dynasties that emulated him. It’s often seen in Cleopatra VII’s coinage

- She has the melon hairstyle, which she is seen with on coinage and in Roman sculpture. Apparently she popularized it among Roman women when she visited the city!

- Her snake bracelet and bull earrings are also common Ptolemaic motifs

- Livia is dressed like a proper Roman matron in her palla, stola, and tunica. The lack of jewelry is meant to show her modesty as well. Augustus and Livia went out of their way to present as a normal senatorial class couple rather than opulent foreign monarchs

- Her hair is in the iconic nodus style, as seen on basically all her statuary as well as that of other women in Augustus’s household such as Octavia

- Both Livia and Cleopatra are depicted holding cornucopias in their statuary. It associates them with fertility, wealth, and number of mother-goddesses. Pomegranates are a symbol of Juno and Proserpina, wheat and poppy sheafs are associated with Ceres. Wheat is also important because it was a resource Egyptian had in abundance and that Rome was desperate for. A lot of the politics between the two nations were based around that trade.

- And figs. Well, there are a lot of stories that get told about Cleopatra and Livia, many of which paint them with misogynistic stereotypes. Cleopatra’s death has long been the subject of speculation and fantasy. Shakespeare writes that she snuck the snakes she used to commit suicide past the Augustus’s men in a basket of figs. Livia has often been implicated in Augustus’s death. A popular version of that being that she poisoned him with figs. These two women are connected by the imagery and symbolism of the fruit: femininity and fertility, poison and death.

#classicsblr#tagamemnon#augustus#livia drusilla#cleopatra#cleopatra vii#artists on tumblr#my art#digital art#ancient rome#ancient egypt#digital illustration#history#women

108 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roman Egypt

The rich lands of Egypt became the property of Rome after the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE, which spelled the end of the Ptolemaic dynasty that had ruled Egypt since the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE. After the murder of Gaius Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, the Roman Republic was left in turmoil. Fearing for her life and throne, the young queen joined forces with the Roman commander Mark Antony, but their resounding defeat at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE brought the adopted son and heir apparent of Caesar, Gaius Julius Octavius (Octavian), to the Egyptian shores. Desperate, Cleopatra chose suicide rather than face the humiliation of capture. According to one historian, she was simply on the wrong side of a power struggle.

Early Relations with Rome

Rome's presence in Egypt actually predated both Julius Caesar and Octavian. The Romans had been involved periodically in Egyptian politics since the days of Ptolemy VI in the 2nd century BCE. The history of Egypt, dating from the ousting of the Persians under Alexander through the reign of the Ptolemys and the arrival of Julius Caesar, saw a nation suffer through conquest, turmoil, and inner strife. The country had survived for decades under the umbrella of a Greek-speaking ruling family. Although a center of culture and intellect, Alexandria was still a Greek city surrounded by non-Greeks. The Ptolemys, with the exception of Cleopatra VII, never traveled outside the city, let alone learn the native tongue. For generations, they married within the family, brother married sister or uncle married niece.

Ptolemy VI served with his mother, Cleopatra I, until her unexpected death in 176 BCE. Despite having serious troubles with a brother who challenged his right to the throne, he began a chaotic rule of his own. During his reign, Egypt was invaded twice between 169 and 164 BCE by the Seleucid king Antiochus IV; the invading army even approached the outskirts of the capital city of Alexandria; however, with the assistance of Rome, Ptolemy VI regained token control. While the next few pharaohs made little if any impact on Egypt, in 88 BCE the young Ptolemy XI succeeded his exiled father, Ptolemy X. After awarding both Egypt and Cyprus to Rome, Ptolemy XI was placed on the throne by the Roman general Cornelius Sulla and ruled with his step-mother Cleopatra Berenice until he murdered her. Ptolemy XI's ill-advised relationship with Rome caused him to be despised by many Alexandrians, and he was therefore expelled in 58 BCE. However, he eventually regained the throne but was only able to remain there through kickbacks and his ties to Rome.

When the Roman commander Pompey was soundly defeated by Caesar in 48 BCE at the Battle of Pharsalus, he sought refuge in Egypt; however, to win the favor of Caesar, Ptolemy VIII killed and beheaded Pompey. When Caesar arrived, the young pharaoh presented him with Pompey's severed head. Caesar reportedly wept, not because he mourned Pompey's death but supposedly had missed the chance of killing the fallen commander himself. Also, according to some sources, in his eyes, it was a disgraceful way to die. Caesar remained in Egypt to procure the throne for Cleopatra as Ptolemy's actions had forced him to side with the queen against her brother. With the defeat of the young Ptolemy, the Ptolemaic kingdom became a Roman client state, but immune to any political interference from the Roman Senate. Visiting Romans were treated well, even 'pampered and entertained' with sightseeing tours down the Nile. Unfortunately, there was no saving one Roman who accidentally killed a cat - sacred by tradition to the Egyptians - he was executed by a mob of Alexandrians.

History and Shakespeare have recounted ad nauseam the sordid love affair between Caesar and Cleopatra; however, his unexpected assassination forced her to seek help in safeguarding her throne. She chose incorrectly; Antony was not the one. His arrogance had brought the ire of Rome. Antony believed Alexandria to be another Rome, even choosing to be buried there next to Cleopatra. Octavian rallied the citizens and Senate against Antony, and when he landed in Egypt, the young commander became the master of the entire Roman army. His victory over Antony and Cleopatra awarded Rome with the richest kingdom along the Mediterranean Sea. His future was guaranteed. The country's overflowing granaries were now the property of Rome; it became the 'breadbasket' of the empire, the 'jewel of the empire's crown.' However, according to one historian, Octavian believed that Egypt was now his own private kingdom, he was the heir of the Ptolemaic dynasty, a pharaoh. Senators were even prohibited from visiting Egypt without permission.

Continue reading...

56 notes

·

View notes

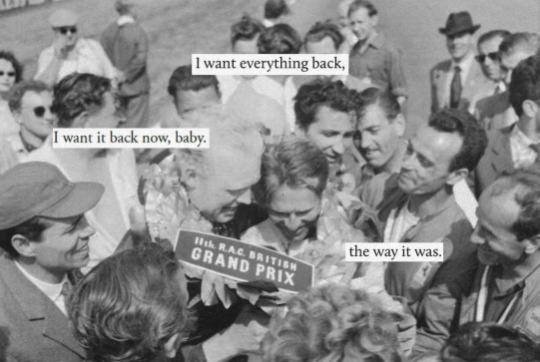

Text

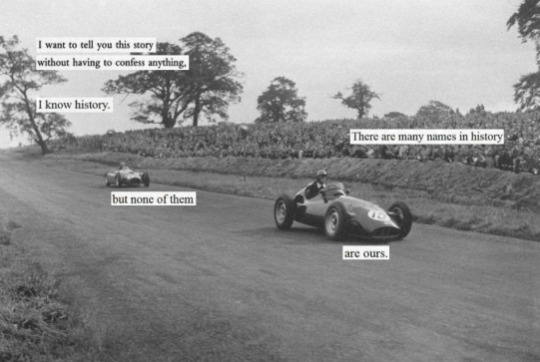

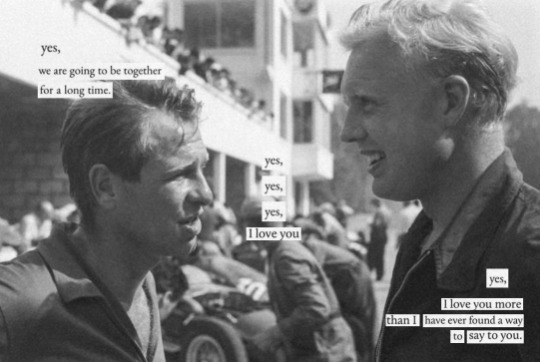

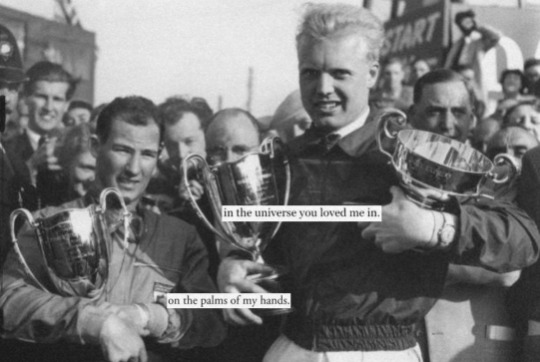

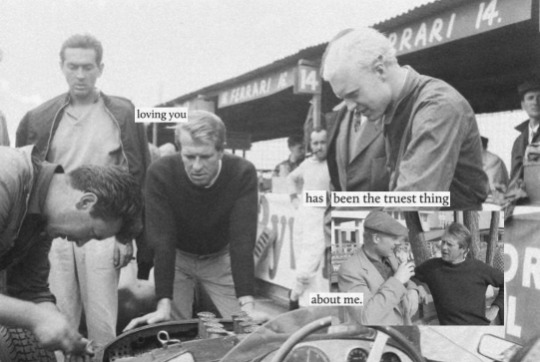

mike hawthorn + peter collins x "little beast", "the torn-up road", "dirty valentine" by richard siken, "the seven husbands of evelyn hugo" by taylor jenkins-reid, "forgetting" by joy ladin, "saudade" by john freeman, "the handmaid's tale" by margaret atwood, "antony and cleopatra" act i scene i by william shakespeare, and other assorted quotes

[ tags: ] @28ms28 , @cazzyf1 , @carbonmono , @dafunzies , @schumi-honey , @darlingnemesis , @sebsonism (please lmk if you want tagged in webweaves! <3)

sources: x , x , x , x , x , x

[ a very late dedication to cazzy <3- sorry it took so long! ]

#if tumblr munches the quality on this i'm logging off#the sourcework for this took years#everything abt this took years lowkey#collins + hawthorn are so close to my heart that a webweave was inevitable unfortunately#wanted to try and do their relationship justice. so. here you go#tentative post before exams because i've already been gone for weeks.. sorry!#pinky promise late may'll see me back to regularly scheduled programming#f1#formula 1#formula one#classic f1#classic formula one#peter collins#mike hawthorn#f1 web weaving#f1 web weave

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pompeo Girolamo Batoni, 1708-1787

Cleopatra and the dying Mark Antony, 1763, oil on canvas, 76x100 cm

Source: The University of Arizona, College of Fine Arts

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

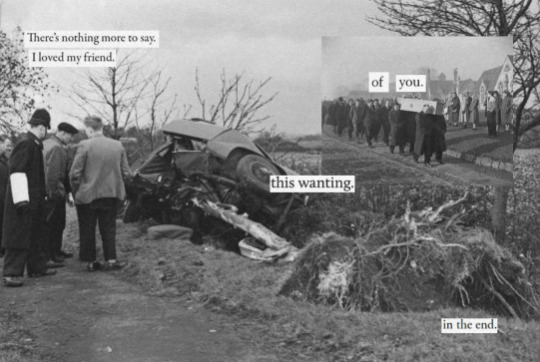

ANTONY: if Caesar doesn't set Sextius Baculus up in a house worthy of Lucullus for all that he did, I'll kill him myself.

so the fun thing about the Caesarians is that there is. weird stuff happening in there. a lot of focus seems to go towards non Caesarian dissent, specifically with the conspiracy of Cassius and Brutus, but there's like. stuff going on in Caesar's own camp that's very Intriguing.

There's a couple places where you can see some clear points that would be grounds for a conspiratorial falling out between Caesar and Trebonius, but from the way that Trebonius tries to seduce Antony over to conspiracy, I wonder if there was a secret third thing that was going on since Antony turned him down but. didn't snitch intriguing!

anyway, all of this is to say that this means I get to invent some shit. like, I'm drawing comics which is already invention, but this is one where I get to really start throwing stuff into the narrative soup because it has to set up three different character arcs (Trebonius, and then Antony twice)

(in theory, this would be explained in the story itself if I did the entirety of the Gallic Wars out as a comic. which I have not done because I do not want to draw horses. I wanted to fuck around with some panel layouts and not draw a single horse, so now I will provide the context and revisit this in the future)

Antony's comment about Trebonius running himself into a grave has to do with the Caesar's Gallic Wars have a lot of men doing a whole lot for Caesar that has me going. hey. hey guys. uh.

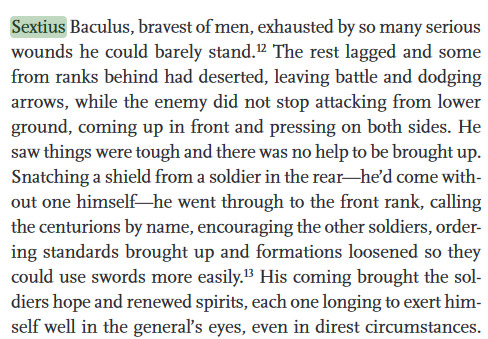

specifically, Sextius Baculus:

The War for Gaul, Julius Caesar (trans James J. O'Donnell)

and the closing comment from Antony is playing on several things: romans claiming gods on their family tree (see: Legendary Genealogies in Late-Republican Rome, T.P. Wiseman for more on this) and then divinization arc of Caesar and Octavian. Antony himself will later be taking part the same kind of god-association that has prompted his disdain in this scene

At any rate, when Antony made his entry into Ephesus, women arrayed like Bacchanals, and men and boys like Satyrs and Pans, led the way before him, and the city was full of ivy and thyrsus-wands and harps and pipes and flutes, the people hailing him as Dionysus Giver of Joy and Beneficent. For he was such, undoubtedly, to some; but to the greater part he was Dionysus Carnivorous and Savage.

Plutarch, Antony 24

and the second layer of thematic fun: Antony's later relationship with his soldiers is something similar to what Caesar had with his here, but ultimately: decayed. Antony's love affair with his military makes his failure to lead well at the end a worse betrayal. at some point I'll talk about Antony's Tormentous Military Nightmare and cite some academic sources, but Linda Bamber's description of the final tragedy of Antony and his men lives in my head rent free

Cleopatra and Antony, Linda Bamber

where's the fun in doing identity focused tragedy if you don't become unrecognizable to yourself later on! isn't that right mark antony

ko-fi⭐ bsky ⭐ pixiv ⭐ pillowfort ⭐ cohost ⭐ cara.app

#gaius trebonius#mark antony#man. this explanation for the scene. is longer than the three panels.#anyway i changed my mind about how trebonius gets his eyebrow scar. he gets it during his Fight with caelius#oh! the crassus mentioned here is the eldest son! sure hope something bad doesn't happen like his father and brother dying haha ha h--#(head in hands)#long post#komiks tag#drawing tag#roman republic tag#anyway. i need to. i need to get my sketch book. this book i was reading called trebonius a pro cassian commander#and im fucking. losing my mind about that. oh my god.

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

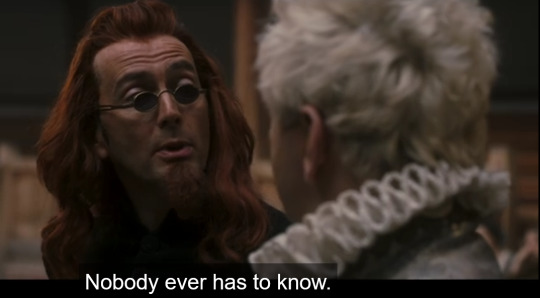

Holy Kittens, Y'all: My Favorite Good Omens Moment Has Gotten EVEN MORE ROMANTIC

Okay so I wrote this post about my favorite moment in Good Omens, and the stuff people are pointing out in the reblogs and comments is blowing my freaking mind, and I HAVE to show you how beautifully this all fits together, like I am flailing at my desk about this.

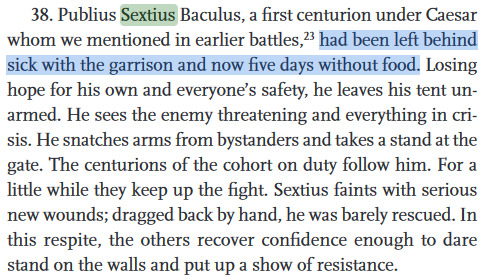

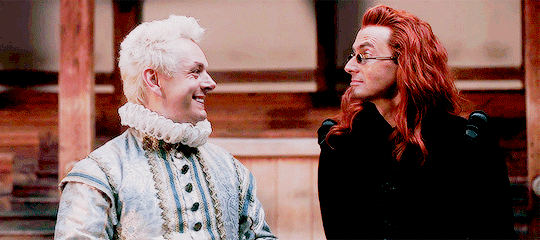

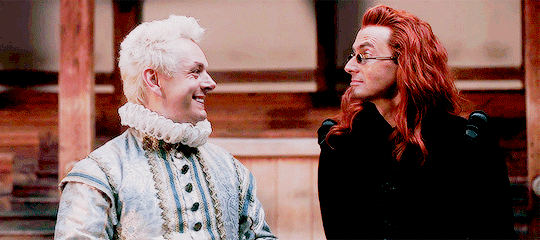

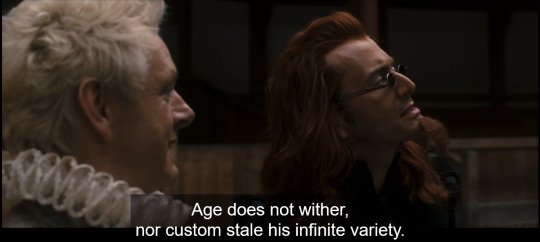

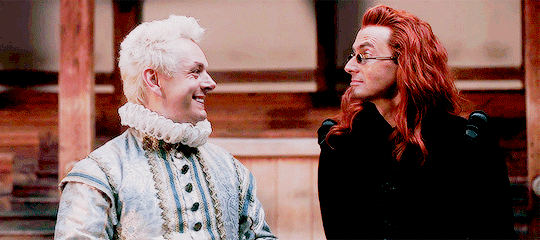

@vidavalor points out this gif from @soft-ange-aziraphale [Source]:

Here it is in sequence (gifs 1-4 from Fuck Yeah Good Omens):

I can't stop laughing over Aziraphale's smile, which shows, as @quoththemaiden says, that he's "utterly delighted with himself" and knows perfectly well that he's minxing Crowley; and this tiny extension of the moment convinces me even more that Crowley is desperately fighting a smile himself here.

Actually there's a lot in @quoththemaiden's comment that's insightful and well-put:

Totes agree with all of this.

And then. AND THEN!

I knew Crowley was trying to communicate something with this Shakespeare line, but I didn't know what until @paperbunny and @musingsofmaisie put it out there: Crowley is complimenting Aziraphale here, telling him he's enjoying being in Aziraphale's company, telling him his humor worked.

Remember how I keep banging on about how much equivocation Crowley does? This is more equivocation. In 1601, Richard Burbage was 34 years old, so age hasn't had the chance to wither his infinite variety yet. The stupidity of demons and the ignorance of angels regarding the human aging process prevent surveillance from noticing the poor applicability of this line to Burbage, but since the first half of the line fits Aziraphale (who does not age at all) more than Burbage (who is merely not yet old) it stands a chance of indicating to Aziraphale that Crowley is speaking about him. And the underlying true meaning of this equivocal statement would be A DIRECT RESPONSE TO MY FAVORITE MOMENT: Even though I have known you so long, you still surprise and delight me.

(Crowley's Antony & Cleopatra line also accomplishes something else important: it gets William Shakespeare to go away so they can speak privately, because Shakespeare doesn't want them to see him writing it down.)

A Dip Into Speculation

I don't think the evidence for it is binding enough to say for sure, because the evidence is really just that it fits together so nicely and lines up so well with A&C's coded romantic messages in 1793; the (pretty overt, actually, I mean damn) romance in 1827; the size and nature of the fight in 1867; the yeah, really overt romance in 1941; and in 1967; and yes okay now that I'm thinking about it the whole series, but I have this View about how the rest of the 1601 scene goes.

And in fact there is Word of Gods that could be interpreted as evidence against this little pet headcanon I have, though it doesn't necessarily have to be:

Here's my assertion: Aziraphale volunteers to go to Edinburgh for Crowley. Crowley cheats the coin toss to accept Aziraphale's offer and to keep up appearances as a demon. Rather than making a deal with (or asking a favor of) an angel, he's 'cheating' him (without the angel's knowledge, but with his consent), which "moves the dials" of evil a bit and would also make Aziraphale appear less at fault if this instance of the Arrangement is ever discovered by Heaven.

This can coexist with Gaiman's statement, above, that it doesn't even occur to Aziraphale that Crowley cheats the toss. THEE ongoing leitmotif of Aziraphale's view of Crowley is that he thinks of Crowley as much more genuinely evil and much less in need of ways to create cover as evil than Crowley actually is.

(Which is interesting, given that he also clearly thinks that Crowley is not as evil as he pretends to be, that he is and wants to do good, and that he deserves to be an angel again. [There is a whoooole nother essay slowly curdling in the churn in my head about how Aziraphale is obliged to practice doublethink and how that stunts his personal development because that's what happens when people aren't free.])

Here's what I mean when I say Aziraphale volunteers.

Does Aziraphale ask in this tone because he is actually feeling suspicious and curt, or because he has to sound suspicious and curt? He could be perfectly willing to do Crowley a favor and would still need to sound the way he does. It's difficult for me to believe this guy--

--or this guy--

--are really all that bothered by the idea that Crowley might want something from him.

Crowley's response sounds like a(n unconvincing) protest of innocence. Maybe it is. But he doesn't disagree with the premise on which Aziraphale based his question, which means Aziraphale now has confirmation: Crowley called the meeting because he wants to ask Aziraphale to do him a favor.

Close your eyes and listen to Sheen's delivery of this line. The way he says it is so soft it's got no judgy angelic sting to it at all. Is this really a prissy answer to Crowley's semi-rhetorical question? Or is Aziraphale using the cover of a prissy answer to ask Crowley, Is what you want related to the no-good you're up to, i.e., demon work?

Either way, Crowley answers:

Is Crowley making a demonic jibe at Aziraphale in return to "You're up to no good," or is he telling Aziraphale, Yes, what I want from you is related to my work, and to your work, esp. what you've got on right now?

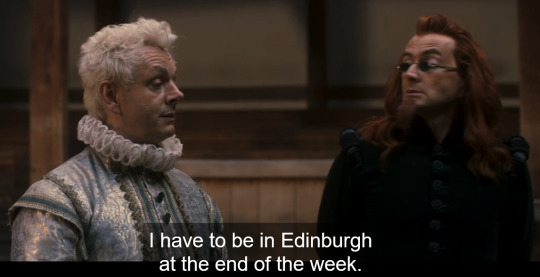

Aziraphale volunteers some information about his schedule and what it is he's got on right now.

--he says, and the velvety way Crowley says "Ohhh," tells us--and could tell Aziraphale--that Crowley already knows this. In this coded communication I'm suggesting, Crowley's tone on "Oh" confirms to Aziraphale that the thing he wants help with does indeed have to do with Aziraphale's trip to Edinburgh.

So Aziraphale gives Crowley his travel details: Yeah, I have a couple of blessings and a minor miracle to perform. It's going to suck; I have to ride a horse.

Crowley's like, yeah, riding horses does suck. You have my sympathies. (Phrasing it as an insult to God: "Major design flaw if you ask me.") And then he says, I have to go to Edinburgh too this week. Tempt a clan leader into stealing some cattle.

And here's where I think Aziraphale volunteers to do Crowley's Edinburgh job for him:

If, as I propose, Aziraphale understands already at this point that Crowley is asking him to take Crowley's Edinburgh temptation, then this response tells Crowley he's willing to do so.

And then they have a little bit of kayfabe theater and a little bit of miscommunication between themselves. Crowley suggests Aziraphale take Crowley's Edinburgh job. Aziraphale protests "You cannot actually be suggesting what I infer you're implying," even though, as Crowley immediately points, out, they've now done this dozens of times.

Now, obviously Aziraphale is pretending innocence here with "You cannot actually be suggesting," etc. But he's not pretending innocence to Crowley. He can't be: Crowley knows about the dozens of other times just like Aziraphale does. So the protest of innocence is for surveillance; it's the spirit, not the letter, of the protest itself that's genuine: I am reluctant about this.

And Crowley misses it.

He reads the surface layer of the equivocation, the Heavenly pearl-clutching; and the surface layer is where he argues. "We've done it before," he points out. "Dozens of times now. The Arrangement--"

But Aziraphale, visibly frightened and looking around, cuts him off. "Don't say that." Getting caught in an Arrangement would be much, much worse than getting caught in a one-off deal.

Why is this suddenly a problem? says Crowley. You know we've been getting away with this; you know they don't check up.

It's not pearl-clutching at all; Aziraphale is worried for Crowley's safety.

When Crowley says--

--is his tone half wheedling and half impatient because that's how he feels, or because it must sound like that? Is it soft only out of courtesy to the other people in the Globe?

There's no difference to the outcome of this scene or the story as a whole whether this romantic interpretation of the Edinburgh bickering is correct, because we've already got a solid base of evidence that the characters have romantic feelings for each other and show each other affection and care in this scene. In my opinion this interpretation fits the tone of the rest of the Globe scene better than only the face-value interpretation. What Gaiman and Mackinnon say about Crowley cheating the coin toss and Aziraphale not being aware of it can still easily apply.

While these three statements together aren't enough evidence to convict, so to speak, if my initial argument about the interpretation of "Buck up!" and Crowley's reaction is correct--and the cool stuff other people have found and pointed out suggests it is AND explains Crowley's Antony & Cleopatra line--this reading of the Edinburgh bickering is, if not ironclad, at least valid.

And holy shit, people, that makes this scene romantic af from beginning to end. I could not have asked for a better little gift from my fellow humans. 🤯I have such a better understanding of the entire 1601 scene because people from anywhere with an Internet connection sat down and spent their time sharing their ideas, and it just makes the lit-nerd lobe of my brain so happy. I love you all, you romantics and nerds and perverts.

#good omens#good omens 1601#ineffable husbands#aziracrow#it turns out my favorite good omens moment keeps going for the rest of the scene#good omens equivocation#crowley equivocation#aziraphale equivocation#good omens meta

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vic Fair “Antony and Cleopatra” original artwork (1972) Source

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anthony, Anthony, Anthony

What does your Anthony mean, exactly?

I feel like your Anthony and my Anthony are different Anthonies…

In 1941 we learn that Crowley has named himself Anthony J. Crowley (Aziraphale doesn’t pronounce the H but closed captions write it and Neil Gaiman hashtags #Anthony and also it’s Anthony the script book so I guess Michael Sheen is just doing a thing idk). I haven’t seen extensive discussion of this topic but I’m going to jump in with both feet.

I propose that Anthony actually has a double meaning; that is, Crowley chose this name for one reason, but Aziraphale believes he chose it for another.

(I cite as indirect inspo a wonderful Tumblr meta about how the ineffable blockheads have completely different interpretations of Jane Austen and how this informs their S2 decision-making).

Read or bookmark for later on Ao3 because this got away from me and now it's a 2,888 word meta on people named Anthony what am I doing with my life

~~~

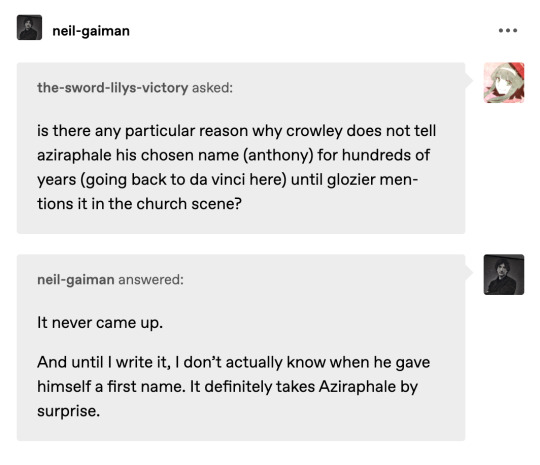

First and foremost, let it be stated that there is no canon for when Crowley anti-christened himself Anthony. Neil Gaiman himself won’t know until he writes it.

Secondly, let it be known that I am not an historian nor a literary scholar of any kind. So people who actually know these stories may find themselves cringing at my surface-level summaries and inaccurate interpretations: I’m just piecing together what I could find easily. I invite someone else to revise and republish if they can delve deeper on these topics.

Part 1: Mark Antony

There is a bust of Marc Antony in Mr. Fell’s bookshop as of S1E1 modern day (2019) which is still there at the end of S2E6, where it features prominently in the center of a shot. In 2019, the bust is adorned with yellow ribbons; in 2023, it is naked. The flashback to 1941 doesn’t give a good view of the part of the shop where the bust would normally be located so I have no idea when the bust actually got added to Aziraphale’s collection. I’m going to assume, for argument’s sake, that Aziraphale acquired this bust after the Blitz. I’m going to further propose that he acquired this bust because he believes that Crowley named himself Anthony after Mark Antony.

Why would Aziraphale think that? Two reasons.

1) Mark Antony was the loser of a civil war for liberty

Mark Antony was a good and loyal Roman citizen, serving Caesar with distinction, even attaining the title of Master of the Horse (Caesar’s second-in-command). See additional metas on horse symbolism seen throughout S2. After the death of Caesar, however, Octavian and members of the senate turned on Antony, starting a civil war. You know, much like a certain someone we know that was involved in Dubious Battle on the Plains of Heaven.

Mark Antony was loyal to Caesar’s political mission, which was to establish a Roman republic, where the voices of the citizens would be heard through their representatives [a suggestion box, if you will]. But Antony’s defeat marked the end of the republic, ushering in an age of autocracy. Octavian, following his victory over Antony, crowned himself the first Emperor of Rome.

2) Mark Antony was a libertine, but also the loyal, ardent lover of Cleopatra

Mark Antony was an infamous, lascivious, debaucherous, womanizing lush. He was also Cleopatra’s lover and closest ally. Though Mark Antony could not often meet with Cleopatra, their affair was allegedly very romantic, and from afar Antony did everything in his power to support Cleopatra politically, expanding her territorial holdings even while they were apart for years.

So legendary was Antony's wanton hedonism that when he went to Athens, he was deified as the New Dionysus, mystic god of wine, happiness, and immortality. Religious propaganda declared Cleopatra the New Isis or Aphrodite (mythic goddess of love and beauty) to his New Dionysus. The ineffable emperors, if you will. [source: Encyclopedia Britannica]

Parallels arising after 1941:

After Antony had officially divorced Octavian’s sister, Octavian formally broke off the ties of personal friendship with Antony and declared war, not against Antony but against Cleopatra. Much like how Shax, after her S2E1 “you scratch my back I’ll scratch yours” proposal, threatened Crowley that if he did not assist her search for Gabriel, Hell would declare war not on him but on Aziraphale.

The legacy of Mark Antony, therefore, is one of hedonism, romance, fighting for a cause that you believe in, and losing that fight. It’s easy to see how Aziraphale drew the conclusion that Anthony J. Crowley took his inspiration from this historical figure.

Part 2: Antony & Cleopatra

How is this a part 2? Weren’t we just talking about Mark Antony and his relationship with Cleopatra? Hear me out.

Crowley has never expressed much interest in politics. Every time something of political import happens, he declares that the humans made it up themselves while also taking credit for it with Hell. This includes 1793 Paris and the Spanish Inquisition. If I forgot any, drop them in the comments.

But Crowley has a deep and pervasive interest in stories, especially romance stories. If he can keep the Bentley from turning it into Queen, he listens to the Velvet Underground. He watches Richard Curtis films (to the degree that he identifies them by director rather than by title). Though book canon is not show canon, it’s worth mentioning that his favorite serial is Golden Girls; while not a romance, it is certainly heartfelt storytelling at its finest and a homosexual staple.

We know, too, that Shakspeare stole a line from him, with an adjustment for pronouns:

"Age Does Not Wither, Nor Custom Stale His Infinite Variety”

Let’s first talk about Crowley’s context for the quote.

Picture it: the Globe Theater, 1601, the house is empty because it’s one of Shakespeare’s gloomy ones and an irritated young Burbage, in the role of Hamlet, is droning out his lines like he would rather be anywhere else.

Burbage: To be or not to be. That is the question.

Aziraphale: To be! I mean, not to be! Come on, Hamlet! Buck up!

Aziraphale looks at Crowley, grinning with delight. Crowley stares back at him, shaking his head slightly, but a smile tugs at the corner of his lip. He wants to be embarrassed, but cannot help being charmed.

Aziraphale: He’s very good, isn’t he?

Crowley: Age does not wither nor custom stale his infinite variety.

Crowley is looking up at the stage, and speaks immediately after Aziraphale has made a comment about Burbage. But is Crowley talking about Burbage? Does it stand to reason that age would not have withered, or custom not staled, this twenty year old (yet somehow jaded) stage actor?

I propose that this is a poetic inversion of the S2E1 cold open, wherein the Starmaker, looking out upon creation, says: “Look at you, you’re gorgeous!” and Aziraphale erroneously thinks the statement was directed at him. Here, even though Crowley isn’t looking at Aziraphale, I believe that Crowley is actually talking about Aziraphale when he delivers that iconic line. Unlike Burbage, Aziraphale is old, very, very old, and we know that he has a penchant for custom, wearing the same clothes and listening to the same music for century upon century. Yet here is this precious angel being a cheerful little peanut gallery of one, continuing to surprise the demon after all this time. Neither age nor custom has staled Aziraphale’s infinite variety.

When Shakespeare commits the line to a play written 1606-1607, a few years after this event, Crowley will recognize his own sentiment about Aziraphale issuing from Antony’s mouth about Cleopatra. The actual historical events will not have left much of an impression, but the immortalization of his own admiration of the angel in human romantic fiction will have.

It must be mentioned that Antony & Cleopatra is a tragedy, where the star-crossed lovers are kept apart by warring factions that demand loyalty to the state at the preclusion of each other.

There are also some (as far as I can tell) nearly copy-paste plot points from Romeo & Juliet about a misunderstood faked suicide followed by actual suicide and the lovers dying in each others’ arms. It does not have a happy ending. Anthony Crowley deliberately choosing his “Christian name” from this play embodies not only his deep love but his hopelessness that he can ever get the happily ever after he desires.

In Summary

Crowley was an admirer, in one respect or another, of Mark Anthony, though he relied more heavily on Shakespeare’s portrayal and reimagining of the character than Aziraphale gives due credit. Nevertheless, the difference…

Wait a minute…

What’s that?

Is that…

A piece of canon evidence that completely undermines my argument??

This screenshot will only be visible to Tumblr users (sorry Ao3), but at some point we get a good look at the Mona Lisa sketch that Crowley has hanging in his apartment. It is signed (translated from Italian) “To my friend Anthony from your friend Leo da V.”

The problem with this is, the Mona Lisa was painted 100 years before Shakespeare penned Antony & Cleopatra.

However, Neil Gaiman reblogged this transcription and translation, posing the hypothetical, “I wonder if Crowley knows what the A in A.Z. Fell stands for.”

Could it be that the Notorious NRG is jerking us around and sending us on wild goose chases? Absolutely a possibility. But. Let’s give a little grace for a moment, and assume that this comment was made in good faith. A bold assumption, I know. But humor me.

We know that Crowley and Aziraphale both knew Jane Austen, but from completely different perspectives. It stands to reason that Crowley knew da Vinci the scientist, but that Antonio Fell knew Leo da V., an artist with a heart that yearned for an unavailable lover. I’m just making wild conjecture that Lisa Gherardini (aka Mona Lisa), the wife of Florentine cloth merchant Francesco del Giocondo, was a love interest of da Vinci, but it could be true in the GO universe and would make for a great story.

Aziraphale also collects signed items from famous people; the inscribed books of Professor Hoffman to a wonderful student, and the S.W. Erdnase book, signed with his real name, come to mind. The Mona Lisa draft fits in much better with that collection of souvenirs than with anything in Crowley’s apartment. So it stands to reason that it could actually be addressed to Aziraphale.

There remains the question of how or why Crowley has it, but I won’t subject that to speculation here. All to say. Neil Gaiman’s implication-by-redirect is… possible. So let’s assume that it is the case, just for a moment.

If the Mona Lisa sketch is signed to “Antonio” Fell, then this allows the above theory regarding Crowley’s self-naming to remain intact. But it brings up a few questions regarding Aziraphale, not the least of which is: why did he name himself Antonio/Anthony?

Part 3: Saint Anthony of Padua

Anthony was the chosen name of a Portuguese monk, taken upon joining the Fransican order. Anthony rose to prominence in the 13th century as a celebrated orator, delivering impassioned and eloquent sermons. He is also associated with some fish symbolism, since he preached at the shore and fish gathered to listen. He was, incidentally, a lover of books:

Anthony had a book of psalms that contained notes and comments to help when teaching students and, in a time when a printing press was not yet invented, he greatly valued it.

When a novice decided to leave the hermitage, he stole Anthony's valuable book. When Anthony discovered it was missing, he prayed it would be found or returned to him. The thief did return the book and in an extra step returned to the Order as well.

The book is said to be preserved in the Franciscan friary in Bologna today. [source: https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=24]

This miraculous incident, wherein the thief not only returns a valuable book but also has a change of heart and returns to the bosom of organized religion, smacks of angelic intervention. But that is neither here nor there.

Saint Anthony is the Patron Saint of the Lost, and is prayed to by those seeking to recover lost things. What is “lost” in this context is usually an item, rather than a person or an intangible concept, however he is also “credited with many miracles involving lost people, lost things and even lost spiritual goods,” such as faith. [Edit: @tsilvy helpfully contributes that "Here in Italy Sant'Antonio is commonly not just the saint patron of lost things, but, maybe primarily, the saint patron of lost *causes*."] He died at the age of 35, and in artwork is typically depicted with a book and the Infant Child Jesus.

It’s a defensible position that the thing that gives Aziraphale the most consternation across the millennia is Crowley’s loss of his angelic status, and it could even be framed such that Aziraphale does not consider Crowley actually fallen, but rather simply lost. It is a fact that he finds difficult to reconcile and, depending on your reading of the Final Fifteen, the offer to restore Crowley’s angelic status is one that is so pivotal to resolving his internal conflict that he cannot refuse. If this conflict is so central for Aziraphale, perhaps he did name himself after a booklover and the patron saint of lost things, hoping that the name would carry with it some of the power of the blessing, and return Crowley to the light, and in turn, to him.

But wait.

Because I googled “St Anthony” to look for some images and….

St. Anthony of the Desert

I shit you not there are multiple St. Antonies and we’re going to talk about another one of them with respect to Aziraphale because this guy is bonkers. The story traces to the Vitae Patrum, yet another fringe biblical text and I cannot even get a quick answer on whether it is canon or apocrypha because it’s so fringe. Anyways. I think the best way to explain St. Anthony of the Desert comes from the wikipedia page on the Desert Fathers:

Sometime around AD 270, Anthony heard a Sunday sermon stating that perfection could be achieved by selling all of one's possessions, giving the proceeds to the poor, and following Jesus. He followed the advice and made the further step of moving deep into the desert to seek complete solitude.

[He] became known as both the father and founder of desert monasticism. By the time Anthony had died in AD 356, thousands of monks and nuns had been drawn to living in the desert following Anthony's example, leading his biographer, Athanasius of Alexandria, to write that "the desert had become a city." The Desert Fathers had a major influence on the development of Christianity.

Let’s all agree that this guy is not Aziraphale; this whole becoming an ascetic and living alone in the middle of a desert thing? Not his cuppertea. But St. Anthony is interesting not just for his decision to go into the desert, but what happened when he got there.

The Torment of St Anthony is a 15th century painting commonly attributed to Michaelangelo. It depicts demons crawling all over and attacking a hermit.

But the first round of demons are scraping the bottom of the barrel, practically the damned. Anthony’s journey continues and he meets another demon. Actually he meets two; a centaur, who is not very helpful, and then a satyr who is. It is much easier to find paintings of St. Anthony and the Centaur than of St. Anthony and the Satyr, so you don’t get an image, but I find the satyr to be a much more interesting character, so you get that story instead:

Anthony found next the satyr, "a manikin with hooked snout, horned forehead, and extremities like goats's feet." This creature was peaceful and offered him fruits, and when Anthony asked who he was, the satyr replied, "I'm a mortal being and one of those inhabitants of the desert whom the Gentiles, deluded by various forms of error, worship under the names of Fauns, Satyrs, and Incubi. I am sent to represent my tribe. We pray you in our behalf to entreat the favor of your Lord and ours, who, we have learnt, came once to save the world, and 'whose sound has gone forth into all the earth.'" Upon hearing this, Anthony was overjoyed and rejoiced over the glory of Christ. He condemned the city of Alexandria for worshiping monsters instead of God while beasts like the satyr spoke about Christ.

St. Anthony, then, is entreated by a demon to ask forgiveness from God upon the demons, and St. Anthony, seemingly, agrees to do it. He’s overjoyed to ask God to forgive demons. In connection to my analysis of the origins of the Metatron, and how Aziraphale and Crowley’s potential beef with him is that, as a human put in the exact same situation, he did the opposite, refusing to take the demon’s petition for mercy to God but instead taking it upon himself to confirm their unforgivability (yes that’s a word now) and damnation.

That seems like it would be pretty important to Aziraphale.

In Summary

I give up. I have no idea what’s going on with this show anymore. Here are two options each for both of our ineffable husbands to have given themselves the same God-blessed/damned name. You guys tell me what you think, I just have a pile of evidence and no spoons to evaluate it.

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

Image Source: Mykukla

Defining Cleopatra

Glory of her father Princess Goddess who loves her father Pharaoh Mistress of Caesar Whore Eternal love of Marc Antony Beloved Enemy of Octavian Foe

Framed by the men in your life You are seen most clearly in the Cobra you pressed to Your breast To escape them.

-Skye

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey man im back have you posted your thesis raw and sloppy yet

for you my friend... it is on the house... click at your peril...

“Her Infinite Variety”: Shakespeare’s Cleopatra in Science Fiction

Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Major in the Humanities

April 18th, 2025

CHAPTER 1: A CERTAIN QUEEN (INTRODUCTION)

Four hundred fifty pages into Emery Robin’s Cleopatran space opera The Stars Undying, the assassins of Caesar come calling. Gracia, the main character and Robin’s Cleopatra equivalent, is visiting space Rome on political business; now she greets Cátia Lançan, who plays the role of the assassin Cassius in a plot modeled after the historical Julius Caesar’s stabbing. Cátia reveals that she has discovered Gracia’s true purpose: to help the Caesar figure, Ceirran, attain immortality by building him a supercomputer the size and shape of a pearl, meant to contain his memories and mind after his death. Gracia bluffs: it is an ordinary pearl; she has never seen it; she is unimpressed. In response, Cátia drops the supercomputer into her glass of wine to watch it erupt. Gracia, who expected to be extorted, realizes she has misjudged the situation: Cátia has come to her fresh from Ceirran’s murder.

Any reader may well be rocked by this scene. Nevertheless, a reader familiar with Cleopatra’s mythos might pick up the additional tail of cultural legend: that of the pearl. It is one of the few stories about the Egyptian queen that Shakespeare, in perhaps the most influential depiction of Cleopatra, completely ignores: Pliny’s Natural History claims that Cleopatra once dissolved a massive pearl earring in wine, then served it as an aphrodisiac to Mark Antony.

Pliny’s story is false—garden-variety, non-computerized pearls do not dissolve in wine—but it encapsulates the aspects of the queen’s legend that preoccupied the Romans and continue to preoccupy modernity: Cleopatra’s voracious sexual appetite and her “exotic” “Eastern” luxury. Only a grotesquely wealthy woman would be so careless with her jewels, and only a grotesquely lustful woman would go to such great lengths to seduce a man. Robin’s rendition turns the tale on its head. The pearl exists because of Gracia’s devotion to Ceirran—qualified by their differing political goals, but still present; it is a gift with no expectation of a sexual reward. And it is Cátia, not Gracia, who destroys it. Cleopatra’s luxurious carelessness becomes Gracia’s frightened vulnerability. The scene does not encourage the reader to gawk at or lust over Gracia but to sympathize with her: the audience, too, has finally learned of the death we expected; we, too, feel both grief and, at last, a release of tension. And, if we know enough history to understand the reference, we feel perhaps a sense of excitement—at our own ability to grasp the intellectual wink; at the book’s cleverness in adapting one of Cleopatra’s most iconic stories. This is a moment of high drama and intensely visual prose. “Rust erupts” with violent immediacy across the computerized pearl, “brown and scarlet and dark as a kiss on someone’s neck,” and the image of the queen with her wine glass, vivid and poised right before her next move, lives on.

Cleopatra VII has spent a long time living on. As a historical figure, her narrative is sparse. Unlike one of her famous lovers (Julius Caesar’s account of his Gallic military campaign stretches eight books), she has left little in the way of source material: nothing written in her own hand; a scattering of coins that may or may not display her face. Nevertheless, since her death in 30 BC, she has been a cigarette, a cartoon, a costume, an operatic role, a seductress, a witch, a lover, a tragedy. In the 2020s AD, she has also become something unexpected: a science fiction protagonist.

NEW HEAVEN, NEW EARTH: CLEOPATRA GOES TO SPACE

Science fiction and William Shakespeare are well-acquainted. In Shakespeare and Science Fiction, Sarah Annes Brown catalogs the Bard’s frequent appearance as a character in time travel and alternate history stories, as well as the presence of his work in fantasy and science-fictional settings (as prohibited literature in dystopian settings, for example, or as proof that even alien cultures find his work universal). Science fiction writers seem determined to prove that Shakespeare was not of an age; he was truly for all time, and all of space, as well.

Brown pays substantially less attention to the repurposing of Shakespeare’s plots and premises—despite the fact that, as I intend to suggest, it is more than possible to read his work as proto-science-fiction. Even when Brown and other academics frame the plays through a genre fiction lens, certain plays draw more attention than others. The most frequently reimagined are the Tempest, one of the first first-contact stories; Hamlet, where concerns about the self and identity lend themselves to issues posthuman identity like artificial intelligence; and Macbeth and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, both texts in which speculative elements (witches, fairies) already drive the story. Brown notes that “the tragedies are invoked more regularly than the histories or comedies.” This is one of the only mentions of the histories. The only Roman play she examines in depth is Coriolanus, in the chapter in dystopia. Antony and Cleopatra receives no mention.

This exclusion seems intuitive. Shakespeare’s histories are, after all, historical. Even the least historically-accurate pop culture Cleopatras are identified by familiarly “Egyptian” symbols: her pharaonic crown and headdress, her elaborate eye makeup, the backdrop of wealth amid the desert, the snake at her breast. Cleopatra’s life was circumscribed by her status as a woman in an Eastern client kingdom of Rome. While she was far from the first ruthlessly powerful Egyptian woman—in Cleopatra’s own family, “various Cleopatras, Berenices, and Arsinoes poisoned husbands [and] murdered brothers”—the world remembers this Cleopatra because of the Romans (especially Shakespeare’s Romans). Her figure loomed monstrous and seductive in the Roman psyche; her rule impacted the fall of the Republic, and even after her death, she slithered her way into the propagandistic art of Horace and Vergil, always a symbol of the Eastern “other.”

In his seminal work Orientalism, Edward Said illuminates the so-called East and West as constructs. “Neither the term Orient nor the concept of the West has any ontological stability;” rather, “each is made up of human effort, partly affirmation, partly identification of the Other.” He does not claim that there is “no corresponding reality” at all to the Western idea of the “East”—of course the region exists, and of course people live there. Rather, Said sets out that the “Orient” is defined and produced by a Western “intellectual authority,” which partitions particular regions and cultures as “Eastern,” then controls academic and cultural representations of this region, filtering each through the lens of the outside “Westerner” or “Occident.” The divide has less to do with geography than the need for a dichotomy: one cannot have an “us” without a “them.” By constructing the “East,” the “West” is able to contrast itself against the Eastern Other, and thus to define itself. The so-called Orient is a region to exploit, but it is also a measuring stick by which to solidify Occidental identity.

Cleopatra, too, is a construction, in history and literature and legend. In the text of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, her “infinite variety” is a product of her almost compulsive theatricality and self-fashioning, from the moment she arrives to meet Antony in a virtuosic display of visual spectacle. On a metatextual level, she is constructed by the Roman propaganda that preserved her in historical amber, by the English author putting words in her mouth, and by a Western audience that still voraciously consumes her image. Cleopatra has often been crafted as metonymy for the entire “East,” “a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences.” Like the East, she is the figure—sinuous, seductive, feminine and dark—against which Romans can define themselves as rigid, logical, and masculine; her scapegoating is not only convenient but necessary in the ongoing process of consolidating identity through the other. It is, to some degree, the role she fills in Shakespeare’s play as well, standing in opposition to Octavian and Rome—though Shakespeare complicates and interrogates this binary throughout, demonstrating that the divide between “East” and “West” is reiterated constantly because it is not self-evident or stable.

If Cleopatra is, then, a figure grounded in time (the end of the Roman republic) and place (the “East,” constructed as it may be), how can she fit into science fiction, the genre of the future? But science fiction is not set in the future by necessity. In an influential 1979 essay, Darko Suvin identified the genre as defined by “the presence and interaction of estrangement and cognition…” and “an imaginative framework alternative to the author’s empirical environment.” The “empirical environment” is the world familiar to the writer (and, presumably, to the reader). To Suvin, science fiction is defined by two conditions: first, that it takes place in a world somehow distinct from this empirical world, and second, that it approaches the strange laws of this new world with scientific rigor.

That is, on the surface, science fiction is defined by an unreal element in the world—a “strange newness” that Suvin calls the “novum” of the text (for example, artificial intelligence, aliens, or the flux capacitor). On a deeper level, however, Suvin argues that science fiction is defined by its ability to reintroduce the reader to a freshly defamiliarized world, similar but uncannily divergent. It holds up, as it were, the mirror to the author’s world:

The aliens—utopians, monsters, or simply differing strangers—are a mirror to man just as the differing country is a mirror for his world. But the mirror is not only a reflecting one, it is also a transforming one, virgin womb and alchemical dynamo: the mirror is a crucible. […] This genre has always been wedded to a hope of finding in the unknown the ideal environment, tribe, state, intelligence, or other aspect of the Supreme Good (or to a fear of and revulsion from its contrary).

Just as the West constructs the East in order to define itself, writers construct science fictional worlds to create an Other by which they can define their own environment. And, Suvin notes, science fiction does not only define, but also redefines, criticizes, and reimagines the world: science fiction is “a diagnosis, a warning, a call to understanding and action, and—most important—a mapping of possible alternatives.” As the great science fiction author Ursula K. Le Guin wrote, “Science fiction is not predictive; it is descriptive.” That is, even science fiction about the future is really about the present. Creating a new world requires a break with the tradition—or an exaggeration of the tradition—of the empirical world. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, for example, takes place in a society where humans have no sexual dimorphism, and thus a society where gender has ceased to exist in any meaningful capacity. The questions this choice invokes—What are the differences between man and woman? How does a lack of gender roles problematize human interaction? Are exclusive binaries even possible to uphold?—are questions easily applied to the reader’s empirical world as well. Le Guin’s constructed world refracts light back at the “real” world, provoking questions with an obliqueness more subtle than a thought experiment. Science fiction is just that: fiction. But the kernels of truth at the core of each nonexistent world allows the reader to look sideways at their own.

Thus, science fiction is perhaps the exact genre in which Cleopatra belongs: a mirrorball genre of constant reflection and infinite variety, a genre playing the eternal Other just as Cleopatra has for centuries. In the two specific science-fictional retellings I will examine, this generic estrangement lends itself to sympathetic depictions of Cleopatra, running against centuries of stories of the vamping, seductive evil queen. In a science fictional world, where the very rules of reality are Other, it is easier to explore what “Other” really means. In a science fictional world, in fact, with the laws of gender and location bent, Cleopatra might not be Other at all. Is Cleopatra exotic in science fiction, or is she right at home?

NOR CUSTOM STALE HER: RETELLINGS & ADAPTATION THEORY

This thesis sets out to analyze two science-fictional “retellings” of Cleopatra’s story. So what defines a retelling? Much of the history of literature is made up of adaptations and re-examinations of the same plots. In the very first paragraph of A Theory of Adaptation, Linda Hutcheon names Shakespeare and Aeschylus as “canonical” authors who “retold familiar stories in new forms.” The process of adaptation is an old and continuous art, practiced by the same authors whose works supply fodder for adaptation now.

Nevertheless, a more specific definition must exist: every work is inspired and influenced by the stories that came before, so the word “retelling” demands more specificity. This thesis draws from Hutcheon’s structure, which includes only those texts with an “overt and defining relationship to prior texts, usually revealingly called ‘sources.’” Adaptations are “inherently ‘palimpsestuous’ works, haunted at all times by their adapted texts;” Barthes called them a “stereophony of echoes, citations, references.” While no text ever really stands alone, adaptations usually explicitly flaunt this relationship to a “parent.” Beneath the surface layer—the words of the new text—lie infinite layers of background reading. Even ordinary turns of phrase are layered with extra weight. The main character Hermione’s declaration, on the final page of E. K. Johnston’s Exit, Pursued By a Bear, that she refuses to live as “a frozen example, a statued monument” of misfortune, may register to any reader as a pretty line. But only those familiar with The Winter’s Tale, Johnston’s “parent” text, will recognize the allusion to Shakespeare’s Queen Hermione’s fate. A potential reading emerges in which the line deliberately repudiates Shakespeare’s ending, opening a new realm of analysis on the relationship between parent and child texts.

Hutcheon defines an adaptation, briefly, as three things: “an acknowledged transposition of a recognizable other work or works,” “a creative and an interpretive act of appropriation/salvaging,” and “an extended intertextual engagement with the adapted work.” “An adaptation,” she adds, “is a derivation that is not derivative;” rather, while an adaptation trumpets its relation to prior texts, it also deliberately warps those prior texts and continues (or diverges from) cultural conversations about the parent text(s).

Working in the strain of Hutcheon, I would like to narrow the parameters even further. Hutcheon counts as adaptation “not just films and stage productions, but also musical arrangements… song covers… visual art… comic book versions… poems put to music and remakes of films, and video games and interactive art.” She includes a great many creative forms, but she also excludes a great many. First of all, sampling does not an adaptation make: brief references that “recontextualize only short fragments” are not enough to qualify a work as an adaptation. T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” for instance, references Antony and Cleopatra (with a host of other works), but a few lines of allusion to Cleopatra’s “burnished throne” are clearly not equivalent to a novel-length reworking of Shakespeare’s narrative. Hutcheon also excludes sequels and prequels, adhering to Marjorie Garber’s observation that these works are spurred by “never wanting a story to end,” while adaptations are spurred by a “desire [for] the repetition as much as the change.” On a similar note, I exclude fanfiction from my definition of a retelling. Most fanfiction disseminated in “fandom” spaces requires a prerequisite knowledge of the setting, characters, and plot of its parent text. I am concerned, however, with works sufficiently independent that audiences do not have to be aware of the parent text, the type of work that Julie Sanders identifies as a “wholesale rethinking of the terms of the original” (rather than, for example, an adaptation that only changes a work’s time period or location). In both of the books I will examine at length, the characters representing Antony and Cleopatra exist in new worlds, but they also have new names and backstories, reminiscent as those names and backstories may be of the parts Shakespeare penned. These works thus stand in contrast to, for example, Linda Bamber’s “Cleopatra and Antony.” Bamber’s work—half essay, half prose adaptation—is a cleverly voicey piece of reception, but it is scaffolded top-to-bottom by the original Shakespeare play: it cannot “stand on its own,” because Bamber assumes readers are familiar with Shakespeare’s plot, structure, and characters.

Like Hutcheon, I am not interested in “fidelity criticism,” that is, in judging an adaptation by how “accurately” it adheres to the details of its parent text. Hutcheon proposes a better way to criticize adaptations: “not in terms of infidelity to a prior text, but in terms of a lack of the creativity and skill to make the text one’s own and thus autonomous.” This is where my interest lies—not in how faithfully my selected authors can trace every contour of Shakespeare’s play, but, rather, in what they change about Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra and what those changes reveal about Cleopatra as a character. This perspective moves away from fidelity criticism’s “implied assumption that adapters aim simply to reproduce the adapted text,” rather than to reexamine, critique, or expand. If an artist cannot diverge from the original work, there is no reason to take interest in the adaptation over the preexisting parent text. Put simply: if I wanted to reexperience Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, I would read the play again.

So what interests audiences in adaptations? Hutcheon cites the appeal of “repetition with variation… the comfort of ritual combined with the piquancy of surprise.” Audiences like familiarity, even when they seek novelty. The most popular works tend to challenge their audiences a little bit, but not too much, which also makes adaptations relatively “financially safe” because fans of the parent text already exist as targets for marketing. This financial security is especially important in expensive and exclusive media such as theater, and may explain “the recent phenomenon of films being ‘musicalized’ for the stage.”

But it would be a vast oversimplification to claim that adaptation is only driven by profit. Most stories endure in ever-changing forms because people enjoy them and because they continue to resonate. The Shakespeare plays most famously reworked and adapted are also broadly considered Shakespeare’s “best” (Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, Macbeth, Lear, and the Tempest, to name a few); far fewer novels promise to retell Timon of Athens. But the quality of Shakespeare’s work still cannot explain just how many Shakespearean adaptations there are. A wealth of literature exists for the reworking; why are so many recent retellings drawn from Shakespeare’s plays?

“To appeal to a global market or even a very particular one,” Hutcheon muses, an adaptor “may have to alter the cultural, regional, or historical specifics of the text being adapted.” When it comes to Shakespeare, however, far less alteration is necessary: Shakespeare’s work is already considered familiar. While few can name all thirty-something plays, the average science fiction reader likely read one or two in school. A Shakespearean retelling, then, can get away with very little cultural alteration, because readers will bring a basic level of background knowledge to the table.

Readers will also, often, bring a basic level of respect for the premise. Despite debates about decentering Shakespeare, or at least removing him from his academic pedestal, the Bard remains a beacon of intellectualism. A Shakespearean retelling borrows this cultural capital and thus carries some stamp of intellectual validity. And intellectual validity confers a vital degree of respectability, which is crucial when many scholars and reviewers alike consider adaptations “culturally inferior,” denigrations and even “desecrations” of the stories they adapt. As Hutcheon observes:

It does seem to be more or less acceptable to adapt Romeo and Juliet into a respected high art form, like an opera or a ballet, but not to make it into a movie, especially an updated one like Baz Luhrmann’s (1996) William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet. If an adaptation is perceived as “lowering” a story (according to some imagined hierarchy of medium or genre), response is likely to be negative.

Never mind that Shakespeare was not actually “high culture” in his day: he wrote for attendees of public theater, hardly a highly-esteemed institution. And, as Hutcheon points out, “Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner were both deeply involved in the financial aspects of their operatic adaptations [of Shakespeare], yet we tend to reserve our negatively judgmental rhetoric for popular culture, as if it is more tainted with capitalism than is high art.”

Hutcheon discusses this idea of adaptational “desecration” primarily in reference to film adaptations of books, as television carries a stink of assumed intellectual inferiority. Nevertheless, this suspicion of pop culture adaptation can extend to novels, and in particular to genre fiction. While science fiction and fantasy have received some critical attention, this attention is often limited to older literature, already culturally influential (for example, Asimov, Bradbury, or Tolkien). Contemporary literary criticism remains hindered by a general cultural idea of which books are “important,” that is, realist and literary, versus which books are “fun,” that is, commercial. Genre fiction—not only science fiction and fantasy, but romance and horror as well—falls into the latter category.

Both novels explored in this thesis are firmly in the science fiction genre, and, while details in each book reward a reader familiar with Antony and Cleopatra, neither book requires intimate knowledge of Shakespeare as a prerequisite. Nevertheless, both texts’ translation of Cleopatra into a new world continues the enduring cultural conversation around Cleopatra as an embodiment of otherness—whatever “otherness” in science fiction means. Emery Robin’s The Stars Undying was published November 2022 by Orbit, an imprint of Hachette; Chloe Gong’s Immortal Longings was published July 2023 by Saga Press, an imprint of Simon and Schuster. That is, both books were published within the last three years by major publishing houses. Both books are explicitly marketed as new twists on the Cleopatra story; both are also explicitly marketed as science fiction. What were the odds, I thought, that one calendar year might see two sci-fi Cleopatra novels? Why would multiple people even think of putting Cleopatra into science fiction?

These questions provided the impetus for this project. Nevertheless, while they share a parent text and a genre, the novels are very distinct. At the simplest level, they are not even the same kind of science fiction. The Stars Undying is a space opera of epic proportions, in which Robin transfers the cultural and physical distance between Shakespeare’s Egypt and Rome to a more dramatic distance between separate planets. The same political tension exists: Szayet (Robin’s Egypt) is a client state in the thrall of the empire of Ceiao (Robin’s Rome). In this world, however, Szayet is a prospect for Ceian conquest because of its technological wealth, not its agricultural surplus. Immortal Longings, on the other hand, is not a space opera but an alternate history novel, grounded in a nation inspired by Hong Kong’s Walled City of Kowloon. Here, the multinational politics of Shakespeare’s play take a backseat to themes of fluidity and vacillation: Gong’s primary novum is a gene that allows most characters to “jump” between bodies as easily as Cleopatra shifts between moods.

On a deeper level, too, the two novels vary widely in style and theme. The Cleopatra figure of The Stars Undying, Altagracia (called Gracia), is the struggling new queen of a planet highly vulnerable to extractive conquest. While the novel attends to Cleopatra’s legendary love stories (with Mark Antony, but also with Julius Caesar), Gracia’s story is at heart a slow, complex political drama, deeply interested in the narratives people create to justify or combat imperialism. Emery Robin is a self-described “sometime student of propaganda;” The Stars Undying draws less from Shakespeare’s plot than from his musings on mythmaking and history. Indeed, the novel is not marketed as a specifically Shakespearean retelling. Its blurb notes only that it “draws inspiration from Roman and Egyptian empires—and the lives and loves of Cleopatra and Julius Caesar.” Nevertheless, I include it as a Shakespearean reception text, both because Shakespeare’s Cleopatra remains the defining pop-cultural image of the character and because Robin includes a number of direct references to Shakespeare’s work (not only Antony and Cleopatra, but also Julius Caesar).

Immortal Longings, by contrast, is marketed as unambiguously “inspired by Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra.” Chloe Gong is already well-known for Shakespearean reception. Her debut novel reimagined Romeo and Juliet in historical Shanghai; it also made her one of the youngest writers to hit the New York Times bestseller list. Her subsequent work has followed the pattern, placing increasingly obscure Shakespeare plays in historical and fantastical new settings, usually with an emphasis on action and romance. Immortal Longings’s adaptation of Antony and Cleopatra centers around the play’s passionate and disastrous central romance, allowing the political implications to fall to the wayside. Gong’s Antony and Cleopatra, Anton Makusa and Calla Tuoleimi, are embroiled in a tournament battle to the death orchestrated by their city’s tyrant king. Shakespeare’s legendary lovers, should their romance fail, stand to lose their national power, but the stakes of Gong’s central romance are more personal: only one can win the death games. Calla’s survival and her feelings for Anton stand in direct opposition; the book hinges not on mythmaking but on the potentially-lethal attraction between the protagonists.

These novels approach Antony and Cleopatra from entirely different angles. For the most part, then, I do not intend to compare them directly. Rather, this thesis explores how each text responds to the most salient qualities of Shakespeare’s Cleopatra: first her unique position as a gendered and ethnic/political Other, then her connection (in the text and metatextually) to theater, which some scholars claim she embodies in herself. How each book employs science fiction to take up, twist, contradict, or ignore Shakespeare’s characterization of Cleopatra serves as an extended case study, not only for Cleopatra as a character but also for the use of science fiction to converse with and transform the canon.

CHAPTER 2: THIS VISIBLE SHAPE

Both Emery Robin’s The Stars Undying and Chloe Gong’s Immortal Longings are set in science fictional worlds without structural misogyny, homophobia, or racism. In the outer space setting of The Stars Undying, same-gender relationships are legally and culturally indistinct from heterosexual relationships—Robin’s Caesar’s marriage to a man is entirely normative, particularly in being political rather than erotic. On the planet of Ceiao, Robin’s Rome, citizens of all genders are expected to perform mandatory military service, and on Szayet, Robin’s Egypt, the fact that both of the king’s potential heirs are women is so meaningless as to go unremarked upon. In Immortal Longings, most citizens of the cities of San-Er can jump between bodies, making gender divisions irrelevant. Bodies aren’t static, so neither are sexed trait, and while a character may identify with any gender they like, this has no bearing on which bodies they are able to seize or why they choose to do so.

This gendered looseness may seem odd. The long tradition of writing about Cleopatra, in history books or on the stage, has defined her intensely by her gender, casting her over and over as the seductress, the other woman, the exotic witch bending Caesar and then Antony to her will. Even in sympathetic portrayals, she is not only woman but foreign woman, exotic woman, dark woman; Chaucer, for example, cannot represent her as a “good woman” without specifying that she is a good wife, and much ink has been spilled about whether she redeems herself by truly loving Antony. This is the tradition Shakespeare’s play inherits: writing Cleopatra without facing down gender is impossible. How, then, can a Cleopatra character exist in a world without misogyny?

LET ROME IN TIBER MELT: ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA’S INSTABILITY

Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra is a play intensely concerned with binaries. On the crudest, most simplified level, the thematic poles of the play center on Rome and Egypt. Rome purportedly represents masculinity, rigidity, war, politics, public identity, all figured through Octavius Caesar; Egypt purportedly represents femininity, fluidity, love, sex, private life—all embodied, of course, by Cleopatra. The Romans thus construct their national identity against Cleopatra’s opposition, an early example of Said’s observation that the “West” produces the “East” to demarcate Western identity via contrast. Yet Shakespeare troubles this easy dichotomy. Over the course of the play, any attempt to maintain this perfect polarity breaks down, revealing that the concept of the “Other” is constructed and precarious rather than natural. The play’s binaries are always on the verge of dissolution, because the world of Antony and Cleopatra is “a world in flux,” defined by “mobility and mutability.”