#theme analysis

Text

a comparison of themes

a brief comparison of the shared/juxtaposed themes between the works "the stranger" by albert camus, "no longer human" by osamu dazai, and "notes from the underground" by fyodor dostoevsky

(will try to keep this spoiler-free as possible!)

opening notes:

themes:

alienation, apathy and envy, misanthropy and understanding others, pride versus conformity

main characters

meursault from "the stranger"

yozo from "no longer human"

underground man from "notes from the underground"

premise

meursault is a man who lives in french algeria. his initial characterization is established when his mother dies, and he doesn't care much. later on, he happens to commit a crime, and we are shown his detached nature throughout the legal/penal process

yozo deems himself "disqualified as a human being" while examining his life; he finds himself unable to understand other people and is frightened by their strange emotions and behaviors while he spirals in and out of addiction and depression

the underground man is a spiteful loner who drives away the people around him and favors his own fantasies over his real life; he chooses to indulge in his romanticized, emotionally charged perspective, which in turn causes him more pain

alienation:

-- all three main characters are shown to be outcasts, unable to participate "properly" in society. in a narrative sense, all three end up "punished" by society for being different (either literally or as they perceive)

-- all three characters try to form romantic relationships, only to be thwarted at some point (note: meursault was arguably most successful). in each case, their prospective partners were interested, only to leave them under circumstances that all arguablely stemmed from the protagonist's actions.

apathy:

-- meursault is apathetic towards his uncaring nature in-of-itself. he is not bothered by his apparent loneliness and callousness, nor how other people perceive him. in fact, he barely sees himself as different, unlike our other two protagonists

-- meanwhile, the underground man tries hard to appear "cool" and unaffected by what he sees as slights upon his honor, but he ends up raging anyway; he envies the status, wealth, and social connections that other people have and emulates those in his fantasies

-- on the other hand, yozo is painfully affected by everything around him and overthinks every action both he and other people make. he determines himself as thoroughly unable to be human

misanthropy and understanding others:

-- the underground man and yozo find themselves disturbed and perplexed by other's actions. both distrust others, believing society to be maliciously out to get them. they're ultimately hindered by this self-consciousness.

-- yozo tried hard to "fit in" to the expectations around him, only to deviate more as he cracked under pressure

-- the underground man tried a few times to be sociable but ultimately gave up and declared himself a member of the "underground", retreating into his own world

-- opposing this is meursault, who is seen as the frightening, perplexing being by other people due to his apparent lack of emotion by the end of the book. however, before the climatic incident of the novel, he was seen as an ordinary, albeit bland, man who just goes through his life. he never tried "too hard" to fit in, even though through his narration, we can tell that he was already apathetic, to begin with. the incident merely called everyone's attention to him

pride versus conformity:

-- ultimately, all three men chose pride, consciously or not. they refused (or were not able) to become molded to society's standards, and all chose the "wrong" path in the end, even though they tried to live "normally" at some point

-- they stayed true to their nature (as outlined above) to the end of their respective novels. each novel resolved with a respective resignation/acceptance of their fates

#literature#books#world literature#character analysis#theme analysis#literary analysis#reading#the stranger#albert camus#no longer human#dazai osamu#notes from the underground#fyodor dostoevsky#book comparison#i love reading#its so fun drawing parallels#i did this instead of working so now you gotta read it#so yeah no poems today#just me gushing over famous books#hope it all makes sense#feel free to correct me#or debate me

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I need more friends who also love character analysis. Infodump to me about your blorbo!!! Analyze those themes bestie!!!

#actually though if anyone just wants to infodump#literally just say hi#I can carry a conversation i got you <3#character analysis#theme analysis

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Outsiders at the table

Tables are one of the most recurring settings in Young Royals season 1. There is a lot to be said about them, the plate setting, who is allowed at what table, etc., I want to focus however on the idea of an outsider at a table or more specifically how someone can be made to feel as an outsider.

Ayub at Eriksson’s

It is implied that Ayub has been Simon’s friend for a long time. So Ayub eating dinner at Eriksson’s in ep 1 should be a frequent occurrence. But look at his face when Sara lashes out and says, “A mix of losers that will never be anything.” This is his school she is talking about. Sara has her reasons (she was bullied there) to say this but Ayub is left to feel like shit. He is left with the realization that he doesn’t fit in there like he used to, that his friends moved on, moved up.

Simon during workies

In ep 2, We see everyone at these small tables just studying (or watching Simon study if you are Wilhelm) during their workies. Simon seems pretty content at this table, he is a student at this school so he has every right to be there. But then enters August and spits the bullshit, “class, ethnicity doesn’t matter.” You can see the immediate discomfort in Simon as he is made to feel like an outsider at this table. And all he was doing is just studying with his classmates.

Linda on Parent’s day

Linda is having the best time when she comes to Hillerska for the parent’s day lunch. She is proud of her kids, she is chatting with the professors, and just getting to see the school. But of course, August has to come to remind them, “Lunch is not for everyone today.” The difference between Linda and the other examples though is how easily she brushes off this push to make her feel like an outsider. It could be that she is an adult and is better at hiding her feelings but I think this actually shows how Linda was used to being treated this way and she just developed a thicker skin.

Wilhelm at the society

Now the society party night table is the most exclusive table. It is only for the members at the top of the chain and Wilhelm at this point is the Crown prince so he should feel right at home. And he does for most of the night, he has no problem accepting this place at the table that his social status and privilege got him. He is laughing, calling the others friends, and fits right in for the most part. Except, when August starts listing the requirements to be part of this club (Noble and first born). Go watch this scene again carefully and notice Wilhelm here. When August says “Noble,” Wilhelm shows no shame in accepting this privilege, he is counting the requirements with his fingers. But then August says “first-born”, and this is when it hits Wilhelm, his face falls, this is not his place, he is in fact an outsider here. He is not the first-born child, he will never be even if Eric is dead. He realizes he doesn’t care for his place at this table anymore, he just wants to get fucked up and forget everything.

There are other examples too, Wille at his first forest ridge dinner, Simon eating lunch at forest ridge, and Sara eating dinner at Manor house but I think these are more self-explanatory.

I want to see a nice parallel to this in season 2, with Wille at Ericsson’s table and Simon at a table in the palace. (I know one is more likely than the other, but it would be so cool to see Simon in the palace)

#young royals#young royals rewatch#outsiders at a table#ayub young royals#simon eriksson#sara eriksson#linda eriksson#crown prince wilhelm#august horn#scene analysis#theme analysis

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anarchist Themes in Assassins Creed (An Overview)

I apologize @assinteractions for the sheer length of this. I kind of hazed out and just kept going once I actually started writing/stopped just researching and drafting.

Note: This has yet to be edited. A link to the full, edited version on AO3 will be included later.

Sources at the bottom. Games are not included in the source list, as I mostly focused on sourcing things that were more external to the games.

Summary: The aim of this post is to look at anarchist themes in (some of) the Assassins Creed franchise. Constraints included the games I’ve actually completed, time, and the topics I felt comfortable speaking deeper on vs the ones that I felt it more appropriate to stay at a surface level, with the hopes those with more experience and knowledge feel comfortable enough to hop in with their perspectives and opinions. Finally, it ends with a brief look at the conflicts such theming creates for Ubisoft, and an analysis of the poor decisions made as a result. It is not in any way an attempt to exonerate Ubisoft, and I hope my tone makes that clear. Rather, it is an attempt to understand why a narrative with these themes has the kind of execution that it does.

Definitions & Sub-Categories

Any discussion around anarchy should start, at minimum, with some definitions. At its broadest, as defined in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (plato.stanford.edu; note, this is the major source for much of the philosophical side of this analysis, as I do work and have a number of personal projects going on that chip into my time to do the heavy reading for this kind of meta), anarchy is an ideology that is suspicious of the state. Most forms of anarchy will outright declare the state unethical, and suggest that the organization of people in such a manner causes more harm than good.

As things fall, there are then two (again, very broad for the purposes of this essay) sub-categories of anarchy that fall along action lines. I hesitate to use political terminology due to the flexibility and malleability of such terms, so instead I will term them collective-interest and individual-interest.

Collective interest anarchy would posit that, in the place of the state, the organization of people should be undertaken in the form of voluntary-association communes. First, the voluntary nature is important. This idea of anarchy would posit that the most ethical way of organizing should include an “opt-out” option. If you are unhappy, it should be within your freedom to find another group or to live on your own, if you so choose.

The collective piece comes in that mutual aid is a major part of this conception of ideal anarchic organization. Community gardens tended by the group, community work, etc. The group works together for their mutual gain.

The individualist conception of anarchy instead posits an “everyone for themselves” mentality. One’s personal interests should be paramount. It also presupposes that each individual has near equal ability to act in their interests and, thus, does not or should not need aid (excepting, in some conceptions, extreme circumstances).

Notably, the individual-interest conception aligns well with the needs and goals of capitalism. It perpetuates narratives that outright support and perpetuate capitalism. Hence, sometimes, you will see the term “anarcho-capitalism”, often referencing a stark minimizing of the state in the interests of letting corporate and capitalist organizations take the lead.

As such, this analysis will be in three parts. First, a look at the Creed itself. Then, a look at both the depictions of collective organization/work efforts in several games and the depictions of state power. Finally, a more Doylist look at how the status of Ubisoft as a corporation impacted telling a story that so prominently centers anarchist philosophies and ideas.

For the only outright political commentary I will make in this essay, if you do support anarcho-capitalism, I would ask you to do actual, proper research into the history of the US labor rights movement (as a look at just how bad it can get) or the labor rights movement in your country. The Battle of Blair Mountain, the shootings of tent cities, often populated by workers kicked out of factory housing for trying to unionize, the casualties of the Triangle Shirt-Waist Fire, and the brutalization of children under child labor practices are all aspects of unchecked capitalism, but they are not the only ones.

The Assassins and Anarchy: The Creed

The Assassins have several maxims they operate by. The ones most of interest to this analysis, however, are the last tenet of the Creed (“Never compromise the Brotherhood”) and the often quoted Creed-maxim itself, “Nothing is true, everything is permitted.”

Starting with the latter, it suggests a philosophy inherently suspect of state/social authorities. Nothing is true, therefore social/cultural norms are open for questioning. If they are open for questioning, then everything is theoretically permitted. I stress that this is in theory, because from the first game we are given Altair saying that the Creed requires and mandates wisdom. It requires that those that follow it use their own judgment, not the judgment of others or of society in determining the validity and ethical weight of their actions.

The first cited piece points to what is a more broadly seen collectivist instinct in the Assassins throughout the franchise. The Brotherhood is a collective, an organization made up of multiple individuals, but those individuals seek to work to their mutual gain and goals. This may involve compromising some personal goals or gains in that pursuit.

This collectivist mindset is also put forward towards the people. While on some level, the people around them are tools in the execution of their goals (“Hide in plain sight” often being demonstrated as “hide yourself among the civilian population”), they are focused on minimizing the harm they do to those around them. Both the tenet of staying their blade from innocents and the rebuke given for too-public of assassinations play into this. To have such a public assassination would, historically, cause problemes for the otherwise uninvolved civilians. Soldiers and guards might ransack houses, or seize family members while they try to find the culprit.

This creed, however, lasts throughout history and throughout major social and political shifts. That suggests a guiding principle that would stress adapting to the times more than adhering to a traditional interpretation of the Creed.

This collective-interest focus of the Assassins then shows throughout the games in the economic aspects. Ezio rebuilds Monteriggioni, Arno funds a place of public discourse in France, the Fryes become known entities and forces for protection on the streets of London. Somewhere in the twentieth century, though, we see the shift towards an individual-focus in line with their fall in power. Notably, this is not the only time we see such a parallel.

I will also note that, while the selection of games is limited to games I have played most or all the way through, I have also gone out of my way to pick games that take place in major social/political/economic shifts in history.

Ezio

To start with the collective action comparisons, the best place to start is Assassins Creed II.

Upon taking some level of power and control in Monteriggioni, the player is introduced to the economic mechanic of rebuilding the town to generate income. However, from a more Watsonian perspective, we are seeing that Ezio is taking the reigns of the city and immediately working to improve the conditions of its people. After all, none of these people are Assassins. He is doing this because he sees them as part of his cause, though not part of his Brotherhood. On one of the broadest scales we see in the games, the Assassin character is actively working to the betterment of the immediate group around them.

Notably, he is not looking to engage in politics (state activities) outside of eliminating the Templars. This is somewhat complicated by the social systems of the day - namely, that as a Lord he has a theoretical duty to be seeing to the welfare of his people. We are shown, however, that he is a change from the previous lord, his own uncle. He is taking action where others have not. Ezio, being then a bastion of a rejuvenated Brotherhood later in the timeline, builds his legacy on a basis that challenges a major arbiter of state/military power (the Church) while also working towards collective good and goals. This is a consistent narrative choice in his later games, I understand, though I have not completed those games.

Arno Dorian

Next in the line up, from the timeline, we have Arno Dorian. He is in a more familiar setting. While still French nobility, we see him in a sort of liminal position. As an orphan and a ward of another noble in these times, Arno doesn’t have much standing or position himself, it is entirely dependent on Msr. de la Serre. Furthermore, we are shown that an adult Arno, while enjoying the finer life provided to him, is just as comfortable among people of a lower socioeconomic class. That comfort remains a standing part of his character, even bringing him into conflict later with other higher class Assassins. Furthermore, the comfort remains even after he loses the protection of being the de la Serre ward.

Moreover, Arno’s fluidity between the classes is largely made possible by his morals. He is an Assassin because he believes in the values, but he clashes throughout the game. The Dead Kings DLC gives some impression that his grief had pushed him, for some time, away from Paris, it is telling how the sequence opens. De Sade is based in Paris. Given his acquaintance with Arno and his shown-to-be-keen understanding of the goings-on around him, it is a safe assumption that he knows about the Assassins. If he doesn’t know how to contact them, he knows where the Cafe Theatre is and can assume there are people there to pass along a message.

Instead, he seeks out Arno, knowing that Arno’s motives will not be entirely based in the goals of the Assassins, but in part curiosity, and part the welfare of the people. He can interact with the various levels of Parisian society because he is acting from goals of protection and assistance.

That the economic function is the Cafe Theatre and the social clubs is also symbolically important. France is in the middle of massive upheaval, and the game goes out of its way to demonstrate that much of the city is torn between monarchy and the ideal of a republic. Using the benevolent benefactor model we saw with Ezio doesn’t work in that context, specifically because Paris and France are not holding to the social structures that support that. Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite (pardon my spelling), as the famous slogan goes, are the ethos of the day.

The Cafe Theater, then, serves as a meeting place for all those ideas and ideals to come. Arno is, in essence, opening and hosting a salon for the people of Paris to share and debate their ideas. His business is benefiting the Assassins as much as it is benefiting the people. The inclusion of crowd events, then, suggests another shift in the collective-focused Assassin mindset. Direct action in the midst of the chaos means that Arno is able to do a lot of good directly on the streets, preventing pickpockets and the like. While similar mechanics existed in other games (i.e. the criers and hunting corrupt politicians in II), they are named and tallied in Unity.

As far as being a transitional period for the Assassins and for history, the French Revolution is the end of a monarchy in a major European power. France, at the time, was also a hub of philosophical and political thought. Often termed the Enlightenment, this period was rife with new ideas for French society.

A liminal character in a liminal space in a liminal time, then, fits the criteria set above: someone operating and adapting the Creed from what they are introduced to into something that fits the needs of the people and time.

Arno is inducted with ceremony and ritual. It is not unlike the Templar inductions we see, particularly if we take into account the companion novel. While understandable, it is remarkable from a viewing perspective that the aesthetics are so closely aligned. Indeed, Mirabeau, a sympathetic character in his own right, is shown as being hesitant to act. The fragile peace with the Templars is already gone, with de la Serre dead, but he still wants to fight to preserve it. Also being part of the monarchist faction of France, he is the embodiment of an “Old Guard” of French elites.

Conversely, we are given a sort of “old guard” of Assassin thought in Pierre Bellec. He is hardened by what he has witnessed from the Templars, and he does not trust the peace with them at all. He is vocally against anything to do with Elise de la Serre, regardless that as a temporary ally she could be incredibly useful. He is a foil, in many ways, to Mirabeau as he is to Elise, but he also fulfills a similar narrative purpose: pushing Arno to consider more than what he is told, but what he sees in front of him.

Taking our earlier discussion of the Cafe Theatre and the crowd events, then, into account, we are left with the beginnings of what Syndicate later built upon: Assassins that are working on smaller levels, and notably outside of state authority, to better the lives of the people. Arno is pursued by police for crowd events, if they see him. Further, he often is seen actively breaking into areas of power and chasing down information or targets that are holders of state power, whether directly or indirectly via their money.

Syndicate: Gangs, Poverty, and Collective Interest

Syndicate brings the player to the shifting tides of industrial London. The urbanization, giving way to dangerous living conditions, the lack of regulation on products in the ever-shifting market, and the need to survive are the backdrop for the story of the Frye twins hunting Crawford Starrick. Moreover, the hunt takes place in the aftermath of outright rebellious action; the Assassins are based in Crawley, where the Fryes have grown up. Jayadeep Mir has been begging assistance from the British Assassins for a significant time because the people of London are suffering. He has been denied, in equal measure, because of the distance, physical and symbolic, of the Assassins from the people.

That the Frye twins start in Whitechapel is particularly notable. They start with getting control in a neighborhood that is already poor, and already suffering. The game works through the districts systematically, and they get progressively nicer as the player works their way through. The economic stratification, then, is part of the scenery, and for good reason. To start in an idyllic London, some of both the side quests and the main story wouldn’t quite stand out as much.

But the scenery is not so important as the story. And what Syndicate does, in the vein of collective-interest anarchy, is focus on a story that has as much a sociopolitical factor as it does a historical one.

Crime and gang violence are, often, associated with poverty. And while there is a false assumptions in institutions of “law enforcement” that poor areas will stop being poor if crime is “addressed”, usually in a way that is preferable to the propertied classes (Behind the Bastards: Behind the Police miniseries), academic research has borne out a different understanding.

Studies of crime and poverty suggest that the lack of resources that is such a persistent part of poverty is more likely to increase crime. Furthermore, research bears out that when measures are taken to better distribute resources, to increase access to resources for communities that need them, and to reduce income inequality, there is a higher level of trust and lower levels of crime (Some sources below; Robert, of Behind the Bastards also covers it in the linked episodes (and other episodes) with better sources than my “what isn’t behind a paywall” searching could).

Similarly, gangs often form out of a need for community protection. From the Sicilian Mafia to the gangs we see in Syndicate, it is clear that there is an initial function to the gang. The Sicilian Mafia started due to the lack of social protections in Sicily (Overly Sarcastic Productions, “History Sumamrized: Sicily” does a nice little overview of this). A group with a collective goal and interest. However, as Syndicate makes clear, it is all too easy for a collective interest group that is willing to work outside the confines of the law to act in selfish interest. The Blighters are, after all, the first gang we meet. Quite aptly named, as well, given they are a blight to the people. The Blighters also act in the traditional role of police, despite the existence of the police in-game (Behind the Bastards): they are paid thugs working toward aims set by people with more money. This is also shown, in brief, in Rogue. Hope Jensen’s gangs start extorting the people they claim to protect.

It is important, then, that from the outset the Rooks, both the name for a type of bird-of-prey and a notably strong-yet-limited piece on the chessboard, are given a clear mandate and mission. They are meant to help liberate London, and it is established early on. It is also a way, given Rook power in any region grows through the player taking down other gang bases, Templar agents and institutions working off of child labor, for the player to see the “improved economic conditions create improved social conditions” paradigm.

The Rooks are a criminal element, but within a society that is working off of exploitation. The state power is bolstered by the likes of Crawford Starrick, and has little interest in separating from them. By this point in history, the East India company was gaining power through the sheer amount of capital they brought to Britain, nevermind they were doing it to the cost and tune of human life and wellbeing across the globe. By the point the game takes place, the British crown had outright taken control of the British East India Company, all its India holdings, and its armed forces. Again, I would refer back to Behind the Bastards, specifically the second episode listed below, “How the Police Went from Gangsters to An Army for the Rich”. The thesis of the game, then, relies on the earlier discussion of the Creed commanding wisdom above all else.

The Fryes cannot single-handedly dismantle capitalism in the industrial era, nor can they, alone, undo poverty in London and its effects. The helplessness is, in some instances, baked into the narrative. They are inherently limited, unless they want to tangle with state power. Beyond just outright denying Queen Victoria on her final side-quest due to the ethics of colonialism, though, the Frye twins’ story also centers it in the main narrative. Working with Mrs. Disraeli means Jacob has to try and cater to a woman who has, as far as he can see, little understanding of how the lower classes of London live and work. That she manages well enough is a surprise to him, and part of what is meant to endear her to the player; she is not as bad as other state actors.

The ball scene, however, is set in the seat of power in Britain: Buckingham Palace. It is no coincidence that Evie’s dress constricts her as she has to talk to Crawford Starrick. While the use of the trope could be dismantled for a separate, feminist critique of the game, the physical metaphor is powerful: If Evie (or Jacob) were to be working through the existing institutions of power, they would not be able to accomplish their goals in any significant manner. They would be inherently limited by the interests of the propertied class, whose voices would outnumber them. Yes, this scene is during the hunt for the Shroud. But the hunt for the Shroud has taken place alongside the social narrative, and continues to do so.

It is little wonder, then, that we have allies like Karl Marx throughout the game, discussing the state of class politics in Britain. Or that, as players, we are watching the bottom-up approach of organizing and agitating. While there is another critique (and it will be brought up later) of how this could then be extended as a metaphor for unionization, and the sticky bits involved, in the context of the game it is important that the player understand why the existing power structures are not a viable option for the (social) goals of the Frye twins.

Which brings us back to Freddy Abberline. From the outset, he says he doesn’t get the money to do the work he really wants to do, which is work that would help the people around him. He is inherently limited. He is the “good cop”, and the game centers the limitations he exists within as it shows the ways the cops exist as part of the institutions funded and perpetuated by the propertied classes. Notably, our discussion of backdrop comes back here. The nicer the neighborhoods in Syndicate, the more police presence there is. While actual research on real-world policing bears out the opposite (Behind the Bastards), the police are as much a symbol in this game as they are a social mechanic. As a symbol, then, the game is making clear that the wealthier people have the money to be protected and to be worth protecting. The poorer districts, however, do not see the same attention.

Bill Miles & The Modern Assassins

It makes sense, then, that the narrative of the games would show the failures of the modern assassins alongside the creep towards individual-minded practices. Much like the decline of Monteriggioni under Mario, the modern assassins and what I’ve seen in various fan spaces called Bill’s “scorched earth” policy, the same policy that saw Clay Kaczmarek sacrificed as a test subject to Abstergo, is emblematic of the departure from the thing that made Assassins successful in the past: adaptation, and social consciousness.

Notably, things come together once Desmond is involved. He is shown trying to get to know the people around him, and that encourages a stronger team atmosphere. The lessons Bill seems to learn from this then translate into later games such as Odyssey, where we see Layla Hassan working with an Assassin Team (and, in the DLC, the consequences she sees when she focuses too much on her goal and not enough on the advice and value of her team), and Valhalla, where we catch up with Sean and Rebecca as they once again work on a team towards Assassin goals.

The Assassins also seem to have failed to adapt to 21st Century capitalism. Where Ezio funded the city through his work until it funded itself, Arno funded the Assassins through fostering a community resource, and the Fryes through the use of a protection racket that aimed to actually protect the people, the Assassins are secluded. The Farm is hidden in the middle of the Black Hills, and is repeatedly suggested to be incredibly remote. Desmond, notably, manages (on some level) because of the time he spent integrated into the normal world. How would the Isu plans of him being the savior have panned out if he had no concrete connection to the broader people?

Isolation, then, from the people is part of what brings the Assassins low.

Templars: Agents & Emblems of the State

The Borgias

I will admit outright that, like the section on ACII, this will be a somewhat shorter section. My knowledge of Renaissance Italy is not so strong as my knowledge of more recent/modern political factions and movements.

Given the Italian peninsula saw state power more organized along city-state lines during the Renaissance, as Italy would not unified until the 19th century, the writers were left with the question of where to put the vestments of state power. States, however, are one more type of institution; the institution with the most broad-reaching power, then, is the Catholic Church, leading us to the Borgia. In some regards, it makes sense that this was the second setting in the Franchise; the Knights Templar, after all, were very entangled with Catholic history.

What is particularly of note, however, is that the Borgias (even in reality) were agents of social and religious power. The Catholic Church, for one, was very tied up in political and military matters throughout European history, particularly in the Renaissance. I’ve linked all four parts of the Overly Sarcastic Productions Pope Fights series as they’re very funny and informative, but the relevant one is Pope Fights 3 (and yes, Blue makes an Assassins Creed reference). This goes over some of the history in more detail than I am capable of doing.

Our track of analysis, however, is more looking at why pick this period. The scientific progress, certainly, allows for the transitional narrative we see from Ezio. From the side of choosing antagonists, the Borgia are historically attractive antagonists. They make it easy, in some regards, to cast them as the villains. However, the choice of protagonists makes for its own compelling argument.

As they’re written, the narrative religious power is vested in Rodrigo, the narrative military power in Cesare and the narrative social power in Lucrezia. The family is a foil to the Auditore family in many ways; the Auditore family was, at its closest, power adjacent. Giovanni was a banker, making his social power largely reliant on the good graces (and remaining-in-power) of Lorenzo di Medici. Ezio spends the series being a criminal and outlaw; he isn’t in a position to occupy more than social and economic power, and even that is constrained by what social circles he can actually access. Mario is shown to be more personally comfortable around mercenaries than he is around politics. Contrasted, the Borgia are dripping in the trappings of power.

Moreover, both families operate off a triad of characters. The fighters, Cesare and Ezio, are accompanied by a sister and a parent. Ezio and Cesare are, arguably, the most similar. They are both the “military”/force arm of the triad. However, where Ezio’s power is increased by work for the people where he is, Cesare’s is increased at their detriment. Similarly, while both Claudia and Lucrezia, the sisters, are involved in working towards family goals, Claudia’s work is often more direct. She oversees the books of Monteriggioni, then takes over the brothel in Rome. Meanwhile, Lucrezia is often seen more as a pawn to be moved and married to political advantage. Finally, Maria and Rodrigo, literally opposites as the matriarch and patriarch of their respective families, are the last symbols of the divide between the Assassins and their localized mutual-aid organizing and the Templars far-reaching sociopolitical power. Borgia is a man in the Renaissance, and Pope besides. He has all the social power he could need at his fingertips. Maria is helping her daughter run a brothel in Rome after her family was disgraced.

To summarize, the actions of the Audtiore, which are often taken towards a broader, collective good, are far easier to see against the actions of the Borgia, which often show us a much more fragmented, individualist thought process.

Crawford Starrick: The State And Capital

Crawford Starrick as the villain for an industrial-age story is one that forces the player into seeing a direct line between money and politics. More specifically, positioning him as the head of a major corporation, on the public front, and the backer of many other, illicit enterprises in the private ends, asks the player to consider why there is a connection between politics and money.

As the ability to produce increased so drastically, it is fairly widely acknowledged that worker exploitation became more than commonplace in the West. It became the backbone of the economy. Not unlike the Imperial Roman economy, which could not have functioned without slave labor, the Industrial and Imperial British economy relied on paying unlivable wages and hours that were not meant to be livable or survivable. Workers were meant to become replaceable.

The British started two wars in China over the right to sell opium, a substance the Chinese government had tried to outlaw due to public health and economic concerns. That opium was, most often, from India, where workers were overworked, underpaid, and could often barely afford necessities, all at the command of the British East India Company. Remember, by the time of the game, the EIC is in the hands of the Crown.

However, the discussion of imperial interests is tabled, at first, in the game. Arguably, it may be a wise move. After all, a wide variety of players have to get on board with a staunchly anti-capitalist narrative. Focusing on the evils of imperialism out of the gate might have them turning the game off too soon. Or, Ubisoft is a corporation and doesn’t want to look too closely at the ethical implications of being a corporation.

Crawford Starrick is a conventionally attractive, smartly dressed man. He is established as considering himself a “railroad baron”. The wording here (from the wiki) is telling; railroad barons are the origination of the robber baron trope, in which a wealthy man has amassed that wealth through illicit, illegal, often exploitative means. The self-glorification, however, speaks to a character that is centering power and capital.

However, as the game shows, he does have moments where he is aware of the situation around him. In the face of inflation, he increases his workers wages (though, as the wiki points out, this also consolidates his power, by trying to prevent workers from agitating for other raises) and he promises to financially support Lucy Thorne for her service, before hearing of her death. There is a man somewhere in there that is aware of the good his money can do. However, his most generous act is towards someone from whom he has gained something. His most public facing act of generosity also acts towards his aims.

Finally, we see him at the ball. It makes sense he is there - the player is repeatedly shown he is trying to get the Shroud of Eden. However, just as the interaction between him and Evie shows she (and Jacob) would be limited if they should try to work within the existing power structures, Starrick’s position at the ball is the exact opposite. To begin, it is stressed throughout the narrative that Jacob and Evie would need more money and connections to even go. Starrick’s presence there, regardless of his motives, plants him as a firmly entrenched piece of the institution. He has the kind of prestige and power that he can only get with the money and connections he has built up through exploiting his workers. What all the different ventures he is associated with have been suggesting, what the sheer propagation of factories with his name on them point to, is outright confirmed.

Crawford Starrick, despite his quarrels with the institution of the monarchy, benefits immensely from the capitalism and imperialism that is fueling the British state in 1868.

Abstergo: Modern Pharmaceuticals

The final look at state power is an interesting one to say the least. Abstergo, as a corporation, takes the tropes of the “Tony Stark” archetype; massively wealthy, but doing just enough philanthropy to keep the masses distracted about how they’re so wealthy. Moreover, picking a pharmaceutical company in the age of the opioid crisis, puts an entirely different spin on the narrative as a whole.

The opioid crisis is, on one level, the fault of pharmaceutical companies like the infamous Purdue Pharma incentivizing doctors to prescribe opioids. More details are available in the John Oliver segments linked below. On another level, it is the fault of legislation that treats addiction as a crime and not a public health crisis (see the John Oliver segments on rehab and harm reduction, linked below, for more information). The choice, then, of having Abstergo be a pharmaceutical company is its own point of interest and could serve as its own meta post. To summarize it briefly, though, it positions Abstergo as being directly involved in causing direct harm. And, much like the companies involved in the current opioid epidemic, they have enough money to buy their way around the laws of whichever country they are being challenged in.

However, looking at it from the corporate angle (though I will discuss the motivations in making a narrative centered around emergent tech be spearheaded by a pharmaceutical company in the next section, where I look more at the intersection of Ubisoft’s interests and the actual narrative), it is an industry that continues growing. And, one that is known for being more straight-laced. Start-up cultures and tech-company dress codes are known, at least in some part, for being much more relaxed about professional standards. From a Watsonian perspective, then, choosing the more straight-laced pharmaceutical industry makes sense for an organization like the Templars that centers power and control.

The more interesting perspective, though, is the security forces of Abstergo. Discussed more at length in the second Behind the Bastards link, “How the First Police went from Gangsters to An Army For the Rich), the private security forces are a telling choice. They still have the accoutrement of ‘police’, which is a visual tie to state power and authority.

Anarchist Protagonists, Corporate Creators

This will likely, by far, be the shortest section. Ubisoft is, in the real world, a corporation. This is not disputed. Therefore, their interests are in profit and in keeping and expanding their audience in this franchise.

The challenge, then, for Ubisoft, is how to tell the Assassins Creed stories without running into the conflicting values of the protagonists and their company. For instance, as a corporate entity, they are directly benefited by the propagation of state systems of power. While they may not like working around taxes and regulations, the state still provides a set of agreed upon standards in negotiations, in pricing, and in currency value. They can price their games, then, according to one standard for one country.

However, the stories they tell are centering agents that have reason to be directly questioning the state’s power and existence. Moreover, many anarchist philosophies challenge the basis of capitalist institutions like corporations. After all, corporations, in many cases, are not acting in a collective good or cause more harm than they do benefit. Whether it is worker exploitation (which Ubisoft is notorious for, see sources) or resource exploitation, corporations do not benefit from people (consumers) questioning their value or freedoms.

This means Ubisoft, in many instances, is incentivized to make some incongruous narrative decisions. For instance, while it could be argued the instances of generosity on the part of Crawford Starrick are meant to make him more complex (i.e. raising wages in the face of inflation, promising to financially support Lucy Thorne), the Doylist explanations are not promising, and the Watsonian ones are even less so. On the Doylist front, Starrick is the head of a corporation, and Ubisoft has reason to try and make him more sympathetic. It is far easier to draw a line from Starrick Industries to Ubisoft and other modern corporations than it is from Rodrigo Borgia to a modern company. On the Watsonian front, Starrick raising wages pre-empts any wage calls from the workers themselves, meaning he is kneecapping any forthcoming efforts to agitate for better pay. People grateful for the pay will continue on and people not grateful will be easily marked out and discarded. As for Lucy Thorne, he outright says only one can wear the Shroud, and it will be him. Before he knows she is dead, he intends to leave her behind (setting aside, for now, the complications of the narrative suggesting a cure for disability; that is its own discussion and it is one worth having in a separate post) in order to further his own goals.

Similarly, Ubisoft makes assumptions about its consumer base. Altair is, notably, white as hell in the first game. I haven’t picked the first game back up because it was so jarring. While some have taken the Watsonian track of “it’s an earlier Animus, it makes sense it does weird shit”, there is the Doylist take that… Ubisoft does have a lot of mixed protagonists instead of outright having people of color as their protagonists. Much like the imperial narrative being shunted to the side in Syndicate, Ubisoft doesn’t want to risk making “too many waves” by doing something it thinks will lose buyers.

And the imperialist narrative of Syndicate. Hoo boy. I’ll keep this brief, since it is more useful to go into it on its own, solo merits, and this is already fast approaching “longer than papers I wrote as a poli sci major in college” territory. However, the fact that most of the critique of colonialism is related to a set of side quests that cannot be unlocked until after the main story is, itself, a way to hide them away. Some people will never play those quests, because they play the main story and are done. By the time they do, they might not internalize the message nearly so much as they otherwise might have.

The other opportunity to critique colonialism came in another set of side quests, and yet the face of them was a man who was hesitant to agitate against British imperial activity in India. While on the individual level it seems to be in line with history and it makes sense, as he was taken to Britain for his education (a very common imperialist tactic to put in place local rulers sympathetic to the imperial power), it is still a decision Ubisoft actively made. And why? To blur the lines on the colonialism and imperialism issue.

Finally, making Abstergo a pharmaceutical company as opposed to a tech company, and only introducing the “Abstergo Entertainment” branch later in the franchise, establishes them in a more separate category than Ubisoft. A tech company might make more sense, especially if it were a biotech company. However, the jump from “tech company” to “video game company” is much shorter than “pharmaceutical company” to “video game company”; while this may not be the reasoning for it, it is still worth pointing out the incentive there, in my opinion.

Do not take this list as in any way exhaustive, either. I am open to critique on it, as well, as there are perspectives I am underqualified to speak on on anything more than a surface level.

Sources:

Plato.stanford.edu

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-80897-8 (De Courson & Nettle, 2021; study on poverty, income inequality, and crime. Will admit some of the statistics went a little over my head so open to feedback on this one)

https://okjusticereform.org/2021/12/how-poverty-drives-violent-crime/ (overview of several studies done on the link between poverty, income inequality, and crime)

https://open.spotify.com/episode/3mvH93Dq1on0KlVkwMAaAz?si=4sDaa82HRtmfCrA_GB97XQ (Behind the Bastards: Behind the Police: Slavery, Mass Murder & The Birth of American Policing)

https://open.spotify.com/episode/74UxGpu3UgXKQNWDW8Gzu8?si=xRsUj7-9QuW83G0zCMFUXQ (Behind the Bastards: Behind the Police: How the First Police Went from Gangsters to An Army for the Rich)

https://open.spotify.com/episode/0RuHisfwLLEpl5K6llocZl?si=r5wSKnKNR--ryiobFOrt7g (Behind the Bastards: Behind the Police: The History of American Police and the Ku Klux Klan)

https://open.spotify.com/episode/2oqqAtDrcY36cllysGDHxu?si=vOQ5HryTRD6hY1lvkNLmgA (Behind the Bastards: Behind the Police: How American Police Defeated Lynching via Torture)

https://open.spotify.com/episode/6QDynNT07bFpSp7jzxOUPu?si=fwnbzdqPRY6Kt35elGF3YA (Behind the Bastards: Behind the Police: How Police Unions Made Cops Even Deadlier)

https://open.spotify.com/episode/3PwmCGYt5yPxdwhpEECGJw?si=x0HrzypcR3-tI3exx_ddHg (Behind the Bastards: Behind the Police: How the Police Declared War on Us All)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N9aS8yy1n98&t=23s (Overly Sarcastic Productions: “History Summarized: Sicily)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q5majAET5KA (Overly Sarcastic Productions: “Pope Fights”)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3PiyOojCIDQ&t=527s (Overly Sarcastic Productions: “Pope Fights 2: The Reformation”)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SXm60mJyqqU (Overly Sarcastic Productions: “Pope Fights 3: The Italian Wars”)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4BFsADb5_vY&t=41s (Overly Sarcastic Productions: “Pope Fights - Frederick II History Summarized”)

https://law.jrank.org/pages/9632/Railroad-Robber-Barons.html (Railroad- The Robber Barons)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robber_baron_(industrialist) (Wikipedia: Robber Baron (industrialist))

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQZ2UeOTO3I (John Oliver - Marketing to Doctors)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5pdPrQFjo2o (John Oliver - Opioids)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qCKR6wy94U (John Oliver - Opioids II)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uaCaIhfETsM&t=418s (John Oliver - Opioids III)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hWQiXv0sn9Y (John Oliver - Rehab)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RMpCGD7b_H4 (John Oliver - Harm Reduction)

https://www.theverge.com/2020/10/2/21499334/ubisoft-employees-workplace-misconduct-ceo-yves-guillemot-response (Survey shows 25% of Ubisoft Employees have experienced or witnessed workplace misconduct)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p2nXGULzd88 (Feb 23, 2022: Ubisoft employees are still fighting for better working conditions)

https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2020-07-14-toxic-culture-at-ubisoft-connected-to-dysfunction-in-hr-department (2020: Toxic culture at Ubisoft connected to dysfunction in HR department)

#assassins creed#asscreed#anarchy#meta#critical analysis#theme analysis#ezio auditore#jacob frye#evie frye#arno dorian#crawford starrick#borgias#ubisoft

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Huh, you know what, I’ve never realized how one of the big themes of Wandersong is confidence and self-image. Bard struggles with the idea of not being a hero and not being enough to make a difference, Miriam always has had trouble to be seen and doesn’t know how to make friends or be vulnerable because she’s afraid of rejection, and struggles with the thought of not being needed or important, and then Audrey… Well, the most obvious example of it, the hero, the chosen one with a big destiny to fulfill no matter what. The beloved, the skilled, the always right.

I never realized this, that is, until I spontaneously decided to make a Stranger Things AU with Eddie, Chrissy and Jason. YEAH this is incredibly niche but omfg guys, omfg guys it fits perfectly. Eddie the bard, Chrissy the witch and Jason the hero… Be prepared I will dunk sketches on y’all

#wandersong#mini analysis#character analysis#theme analysis#stranger things#stranger song AU#eddie munson#chrissy cunningham#jason carver#my posts#my au#eddissy#hehehehe

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jack gets into Dean's anime collection, but he skips the hentai and gets obsessed with trippy stuff like Angel's Egg.

youtube

#spn + anime#angel's egg#Youtube#jack + the story of the chicken and the black snake#spn + the bible#spn + religion#tfw + fishing#tfw + faith#jack + nephilim#spn + flood narratives#spn + reality vs unreality#spn + blind faith#spn + amnesia#theme ideas#inspiration#videos#theme analysis#spn + making meaning from nothingness#spn + faith when the miracles happen and when they don't#spn + leviathan#spn + the empty

0 notes

Text

You have 90 minutes to complete. (original poem: r.a.)

In participation of the MCYT Recursive Exchange 2024 hosted by @mcytrecursive!

Inspired by know that all my love will be your breath (i will save you when your lights go out)

[text under cut]

1. Have you ever been in love?

(Please circle your answer.)

a. It's me and him

b. Our hearts beat in sync

c. Our lives intertwined

2. Do you understand what you’ve done?

(Please circle your answer.)

a. I couldn't do anything

b. I lost my balance

c. I doomed us both

3. It's been god knows how long since you felt phantom hands on your neck and there is no one in sight. If you were soul-bound to him and both of you died at the same time then why are you still waiting in the void?

Please answer clearly, in full sentences.

(Not a correct answer:I just wanted to see him one more time).

4. Define two (2):

Fate | The feeling of his forehead against yours

Curse | The moment you realise he isn't linked to you anymore

5. True or False:

i. It was your fault.

ii. You wish you had met him under different circumstances.

iii. You can’t regret a single moment that you had him.

iv. You would do it all over again if you could.

v. It ended long before either of you said anything.

thumbnails:

sketch cover thing for imgur link:

#team ranchers#team rancher#rancher duo#jimmy solidarity#tangotek#trafficshipping#mcyt recursive exchange#events#fic fanart#my art#“canary has butterfly-shaped wings it cant do a dramatic spread like that” watch me. (draws dramatic wings) (sorry)#“you have 90 minutes” have been rattling in my brain for so long ever since i suddenly remembering a web weave using it (yes the beeduo one#very glad i can release it (using it in art) from its confines (my mind)#hm i suppose the title would be more in theme if its abt limited life ranchers#← havnt watched limlife yet#but! happy with what i come up with. lil bit proud even#had so much trouble with the panelling and layers in p2 cause it looks too busy (explodes)#also punching the floor bc i only noticed the “yes-no” pair(?) in the original poem when im already half-done w/ the comic#me when making silly comic makes you do poem analysis#i dont even go there ← does not have enough poetic braincells

2K notes

·

View notes

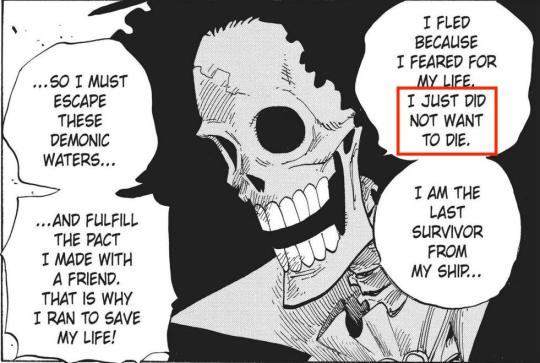

Text

This idea is so, so important to the series in general, and Brook in particular. There are times in One Piece where people die for noble causes, and others where people act knowing that there's a good chance that they could die, but knowingly choosing death over life is never portrayed in a positive light.

As someone who views One Piece through the lens of Romantic literature, this is really important because historically the Romantics, er, well, romanticized suicide and death and the historic last stand. It's doubly interesting to me as a Japanese story, with Japan having its own long, complicated history with the concept of honorable death.

One Piece directly challenges both of these ideas, with life and living being romanticized instead, even if that means you have to get on your knees and beg for it like Brook does with Ryuma later on.

And it's a tightrope that story has to balance. Nami willingly lived under to boot of the man who killed her mother for years, but there came a time when enough was enough, and both she and the village had to stand up and fight for her freedom. She carried that lesson to her fight with Enel, even though she was hopelessly outmatched and would have been reduced to a greasy smear if Luffy hadn't shown up to save her. Within the context of the story both instances were portrayed positively, with Oda indicating through his writing that she had made the correct decision.

But that's not what's happening here. This is Luffy being willing to run away at Sabaody because he knew the Pacificas were too strong. This is Usopp lambasting the samurai at Wano for rushing toward their deaths rather than living to fight another day.

It's Brook knowing he made a promise to a friend, and doing everything in his power to keep it, even if it meant looking like a sniveling coward groveling at the feet of his own shadow.

#opbackgrounds#one piece#ch456#themes threads and throughlines#romanticism#brook#I love him so much#character analysis

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Me: *reading a post that makes the joke “Peeta dropped the baby bomb, Gale drops bombs on babies”* haha good one

Also me: you’re missing the point! You’re missing the point! YOURE MISSING THE POINT! He grew up starving. His best friend almost died of hunger. Most of his people live in poverty. He watched children die in a bloodbath every year for the capital’s entertainment. The girl he loved went into the games. Was tortured by the capitol. His district was bombed out of existence. Nearly everyone he knew was killed. Their only crime was being fed up of being hungry and oppressed and sharing the same district as Katniss. All those innocent people. Murdered. He had to take refuge in a district that was bombed out of existence and forced to live underground. Of course he joined the war effort. Of course he designed unethical bombs and battle tactics. He wanted revenge. He wanted the capitol to have a taste of their own medicine. He wanted the rebellion to succeed. And tell me you could live through what he did, and that no part of you would be screaming for Justice and vengeance. Gale is you. You are Gale. He represents a part of feelings and actions that reside within us, even if you don’t act on it.

“But he killed prim!” Exactly! Gale loved prim. She was a second family to her. He looked after Katniss’ family. He saved them from the district 12 bombings. He loved her. He never would’ve put her in danger. He never would’ve put in order for a bombing if it would kill Prim. But coin would. And did. She took what was meant to be a tool of Gale’s righteous revenge for all the suffering he and his people suffered through, only for someone in power to take it and use it to kill someone he loved.

There’s some many lessons to take. We can’t control the things we create. War spares no one. Even justifiable rage and actions can end up rebounding and hurting those you love instead of your targets.

“He drops bombs on babies” is too simplistic of a takeaway and does a disservice to the story and Gale.

#end rant#the first few times I laughed#now I’m getting tired of seeing the same joke again and again and again#i get it#Peeta is the best boy and you’ve been shipping everlark since the books came out#but please stop ignoring the themes and messages I beg you#Gale didn’t even order the bombing 😭#the hunger games#thg#thg series#thg analysis#thg gale#gale#katniss everdeen#peeta mellark#gale hawthorne#mine#primrose everdeen#everlark#abosas#the capitol#district 12#district 13#president coin#president snow#hunger games

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about film scores & concept albums & auditory storytelling

#grrr argh bite#it's so!!!!!#i love you film & tv composers you're my world#film scores#songwriting#narratives#music#film#leitmotifs#media analysis#themes#motifs#she speaks!#id in alt text#15k

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

anyway while i'm thinking about it i will never understand people who are like "why would you ever watch a movie/read a book/play the same game/etc. more than one when there are always new media to experience, it's just a waste of time" because like. how else are you supposed to fully appreciate the themes and narratives, the artistic choices made, your personal feelings and interpretations and the creator's intentions, the nuances of the story and the characters? every time i revisit a story i already know, i realize there's something i missed last time. i always discover there's more to learn if i'm willing to keep looking for it. there's nothing more exciting to me than searching the same cave for more hidden treasure.

#🐉#this is my dads opinion. he cant understand what i could possibly gain from a repeat viewing#and when i tell him about the themes and analysis and details he says 'so you make stuff up and read into it to stay interested. that#doesnt make sense' and i dont get what hes missing! but our opinions are just incompatible lmao

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

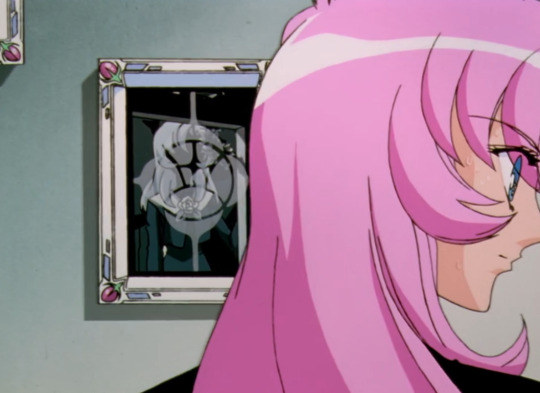

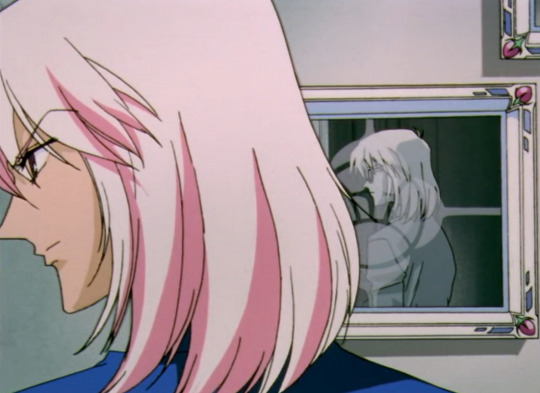

some thoughts on photography and memory in utena:

on the wall in nemuro memorial hall, there are pictures of real people. i'm not sure who they are, but i assume they're of people involved in making the show. either way, they're obviously not real; in the close-up shots of them, they change into pictures of the black rose duelists and other imagery from the show. i imagine it's there as a fun detail by the creators, but also to show how weird and inconsistent reality itself is in the black rose arc.

as for the black rose duel images themselves, it's possible that they are literal as i've talked about in a previous post, but what i think is more likely, is that utena noticing them is a visual representation of her connecting the dots of what's really been going on in this arc.

when mikage brings up the idea of memories and eternity, we see the picture on the wall behind utena, of her at her parents funeral. and behind mikage we see one of his own defining memories.

a pretty clear line is being drawn between memory and photographs. in fact, memories are so important to mikage that photographs are his black rose duel symbol. it's the one he keeps of mamiya and tokiko, altered to look like anthy's disguise, just like his memories are. through mikage we see both how memories of the past can keep you trapped in it, as well as the malleability of these memories. let's look at everybody else:

saionji has a framed photograph of him and touga as kids on his desk. he values their friendship, or at least the memory of how it used to be. he idealizes the time touga was less cruel (or maybe just the time saionji wasn't aware of his cruelty.)

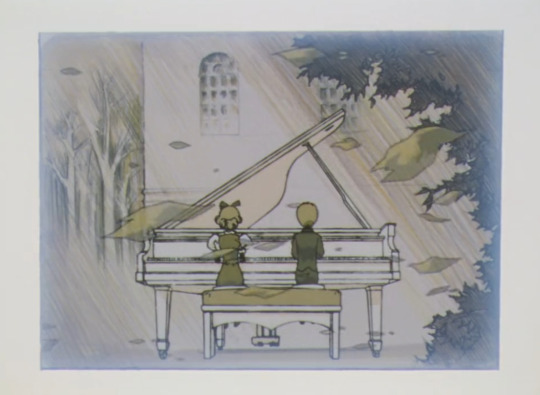

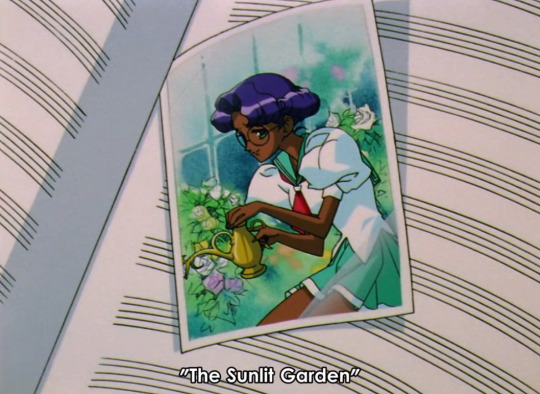

miki doesn't have any literal photographs of kozue or the sunlit garden, though his memories of them are often framed as such. he also keeps a picture of anthy amidst his sheet music. she is his idealized memory now.

juri has the locket of course, inside of which is a cutout of shiori from a picture captured in the moment that ends up defining their entire relationship. is this the version of shiori that juri idealizes? not really, but she is fixated on her resentment of shiori's percieved cruelty, just not the cruelty of taking the boy away. juri keeps this photograph closer than anybody else does with theirs, but she also keeps it hidden. this could mean she treasures her memories the most out of everyone, and is also the least open about it, although i'm not sure i believe the first part.

nanami has the photo-album of her and touga; she idealizes her relationship with him, as well as their childhood. when she makes the connection that touga is adopted, the photos are scattered all over her bed, probably to represent her emotional state.

touga doesn't keep any photographs from what we see, which makes sense with everything we know about him. unlike the rest of the council, he doesn't have any idealized memories of his childhood. but he does use akio's camera, so let's talk about that.

the camera is, much like the car, a tool that only akio is shown to own (although, wakaba does mention a photography club in episode 34.) like the car, it is used to facilitate his grooming (specifically of touga and saionji when he takes those shirtless pictures with them.) and, also like the car, he offers to lend it to touga, to make him feel more like an equal part of the whole thing. unlike the car though, touga accepts the camera.

the photoshoot scene in episode 37 has a transition where the camera shutter sound effect is played over the previous scene. over the shot of utena and anthy holding hands after confiding in each other about akio. i think it's to show that he's always watching, and that they can never truly be free of him as long as they're in ohtori.

i think it also shows the idea of akio framing the narrative of the show as a whole. he plays a sort of director role in it, in that he directs the events happening, as well as how they're portrayed. it's no coincidence that he is quite literally behind the "camera" in episode 33. like the car, a symbol of akio's power and sexual abuse (which is not-coincidentally also present in all of the photoshoot scenes,) his camera (his narrative, his biased framing of events) is ever-present.

and then there's the most important photograph in the show, the frame it all ends on. the picture utena and anthy took together is, unlike every other photograph, used as a look into their future. the reason they take it in the first place is because utena realizes she has no photos of anthy, which distresses her, presumably because she worries that their friendship might not last forever, and she wants something to remember anthy by. this obviously comes with the risk of making anthy an idealized memory, like every other person put in a photograph in this show, but instead it ends up as a symbol for their love. akio may have set up the camera, but anthy (with the help of chu-chu) manipulated their positions so her and utena could hold hands. she also cuts akio out of the frame, much like she cuts him out of her life in the last episode. she doesn't want his presence to tarnish her and utena's memory anymore (although he isn't completely gone from the photograph either, as he will never truly be forgotten.)

#id in alt text#finally finished this post#these are not the only photographs in the show just the ones linked closest to the themes i wanted to discuss here#revolutionary girl utena#analysis#utena#mikage#saionji#miki#juri#nanami#touga#akio#anthy#m#the narrative

602 notes

·

View notes

Text

BBC Merlin being about 'magic' for 7 minutes gay

#not to be all autistic about media analysis again but i think fandom tends to overlook the symbolic/metaphorical aspect of queer subtext#a show can be queer coded because two same sex characters have an intense relationship with homoerotic undertones#or it can be queer coded because it conveys themes of alienation. repressed identity. oppression. internalised shame#Merlin does both. several times over#gay ass wizard show#bbc merlin#merlin#merthur#magic is gay#magic as a metaphor#flashing#flashing lights#< thanks to photosensitive-despair for advising me to change the tags

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Architecture of Rain World: Layers of History

A major theme in Rain World's world design that often goes overlooked is the theme of, as James Primate, the level designer, composer and writer calls it, "Layers of History." This is about how the places in the game feel lived-in, and as though they have been built over each other. Here's what he said on the matter as far back as 2014!

The best example of this is Subterranean, the final area of the base game and a climax of the theme. Subterranean is pretty cleanly slpit vertically, there's the modern subway built over the ancient ruins, which are themselves built over the primordial ruins of the depths. Piercing through these layers is Filtration System, a high tech intrusion that cuts through the ground and visibly drills through the ceiling of the depths.

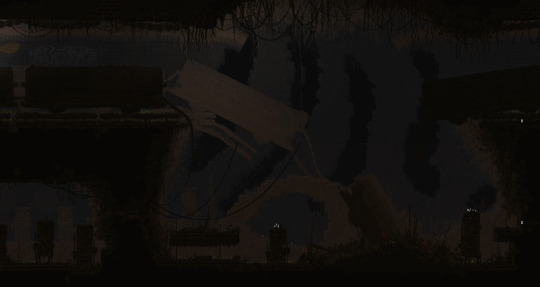

Two Sprouts, Twelve Brackets, the friendly local ghost, tells the player of the "bones of forgotten civilisations, heaped like so many sticks," highlighting this theme of layering as one of the first impressions the player gets of Subterranean. Barely minutes later, the player enters the room SB_H02, where the modern train lines crumble away into a cavern filled with older ruins, which themselves are invaded by the head machines seen prior in outskirts and farm arrays, some of which appear to have been installed destructively into the ruins, some breaking through floors.

These layers flow into each other, highlighting each other's decrepit state.

The filtration system, most likely the latest "layer," is always set apart from the spaces around it. At its top, the train tunnels give way to a vast chasm, where filtration system stands as a tower over the trains, while at the bottom in depths, it penetrates the ceiling of the temple, a destructive presence. (it's also a parallel to the way the leg does something similar in memory crypts, subterranean is full of callbacks like that!)

Filtration system is an interesting kind of transition, in that it is much later and more advanced than both of the areas it cuts between. This is a really interesting choice from James! It would be more "natural" to transition smoothly from the caves of upper subterranean to the depths, but by putting filtration system in between, the two are clearly demarcated as separate. The difference in era becomes palpable, the player has truly found something different and strange.

Depths itself is, obviously, the oldest layer not only of subterranean but of the game itself. The architecture of Depths has little to do with the rest of the game around it, it's a clear sign of the forgotten civilisations that our friend Two Sprouts, Twelve Brackets showed us, there's not actually that much to say about it itself, it's mostly about how it interacts with the other layers of subterranean.

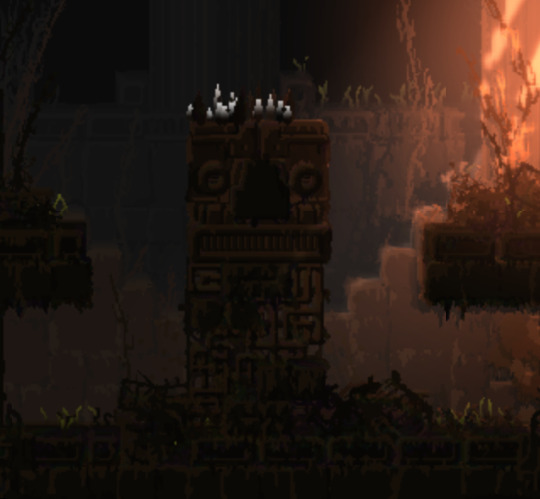

That said, Subterranean is far from the only case of the theme of layers of history. It's present as soon as the player starts the game!

The very first room of the game, SU_C04, is seemingly a cave. It is below the surface, the shapes of it are distinctly amorphous rather than geometric. (well. kind of, it doesn't do a very good job of hiding the tile grid with its 45 degree angles.)

But let's take a closer look, shall we?

See that ground? it's made of bricks. The entire cave area of outskirts is characterised by this, the "chaotic stone" masonry asset is mixed with brickwork, unlike the surface ruins which are mostly stone. This, seemingly, is an inversion of common sense! The caves are bricks and the buildings are stone. This is not, however, a strange and unique aspect but a recurring motif.

This occurs enough in the game for it to be clearly intentional, but why would materials such as bricks be used in otherwise natural looking terrain?

The answer lies in the "Layers of History" theme. This is in fact, something that happens in real life, and it's called a tell

To be specific, a tell is a kind of mound formed by settlements building over the ruins of previous iterations of themselves. Centuries of rubble and detritus form until a hill grows from the city. Cities such as Troy and Jericho are famous examples. The connections to the layers of history theme are pretty clear here, I think. Cities growing, then dying, then becoming the bedrock of the next city. The ground, then, is made of bricks, because the ground is the rubble of past buildings. The bones of forgotten civilisations, heaped like so many sticks!

#rain world#rainworld#rain world lore#rainworld lore#rw lore#rw#subterranean my beloved#thank you to videocult for making the first survival game themed around stratigraphy and new york city rats#i would've gone on for another paragraph about how OE relates to this but like.#that's dlc stuff#and i still think of the dlc stuff as modded content lol#better to keep it separate#also this analysis is not comprehensive! the layers of history stuff is common throughout#there's farm arrays there's the relationship between shaded citadel and five pebbles there's the stuff buried under garbage wastes#so much more#unfortunately i do not have much energy lol

495 notes

·

View notes

Text

will and mike when they first met: i’m not the only one who’s lonely

will and mike in season 1: i’m not the only freak

will and mike in season 2: i’m not the only one who feels crazy

will and mike in season 3: i’m not the only one struggling to survive puberty and figure out who i am if i’m not a kid anymore

will and mike in season 4: i’m not the only one who’s afraid to be honest with people about my feelings

will and mike in season 5: i’m not the only one who’s gay and in love with my best friend???!?

#their dynamic EVERY season has been finding solace and relatability in each other#st3 was a bit different bc even tho they were struggling with basically the same thing#they dealt w it differently which resulted in conflict#but this is the THEME of their friendship#and ppl want me to believe the end of the arc of their friendship will be them NOT feeling the same way as each other??????#yeah ok🙄#stranger things#byler#will byers#mike wheeler#mike wheeler is gay#stranger things 4#stranger things 3#stranger things 2#stranger things 1#byler analysis#byler proof#mike wheeler analysis#anti mileven#eden talks

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

and you know, if you REALLY want to have a rough night, all you have to do is think about how arthur loves. how uther treated him all his life, loving only just enough for him to feel safe, just enough to be protected and not warm. how arthur grew up knowing that, and only that, how it is perfectly clear in the way he treats merlin, because he'll shove him around, yell, and be loud in his words as in his actions, but god will he also go above and beyond to keep him safe, will even lie to uther himself to protect merlin. and truly, that's where his heart really bleeds through, in the veil between how he was taught to love and how he really wants to love, in the moment between, where he's allowed to show he cares, where keeping merlin safe from anyone but him is soaked red with affection, because that's what love is, right?

#02x11 is a horrible episode to watch when you're insane like me btw#merlin rewatch#merthur#bbc merlin#02x11#also yes this is a merthur post only because he does love in different ways#it's different with gwen for example#there are certainly similar themes to be noticed but it is not nearly the same#merlin analysis

344 notes

·

View notes