#to be raised immersed in his mother’s culture instead of that of his white american father

Text

#thinking yet again about how different my grandma’s life could have been had she not assimilated#not just her but how different my father could have been as well as a mixed race child in the city#to be raised immersed in his mother’s culture instead of that of his white american father#i know part of it was there ofc because even i was raised with bits and pieces of it#but ultimately my dad’s values are that of white america’s. that of his father. that of a white man in sf.#i just :/#he could have been different!! he doesn’t even claim his mother’s heritage save for jokes#hnnmhmgngngn……. snifts..#anyways.txt

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Loveboat, Taipei Book Review

Loveboat, Taipei Book Review by Abigail Hing Wen

This book is solid. The few people I’ve foisted conversation onto about this book have heard me lavishly declare it to be the YA teenie-bop version of Crazy Rich Asians.

And while I maintain that my statement above is still true, the book also contained some other elements that either came across as a breath of fresh air or a polluted cloud of toxicity that made me cough and wheeze.

As for the general synopsis, it’s pretty simple all things considered. You have Ever Wong, a senior who is stressed about college applications, her own future potential, disappointing her parents, and ignoring the unrequited love she has for her best friend’s boyfriend. She also happens to be Chinese-American.

Ever’s identity as growing up Asian in the predominantly white-as-bread state of Ohio is kicked off quite strongly from the get-go. Ever talks about how the said pining of her best friend’s boyfriend could have not been pining and instead could have been her, but that he was unwilling to put up with her crazy Asian parents and their strict limitations.

She talks about how her dad, a revered surgeon in Taipei, has been relegated to pushing medical carts in hospitals in the States for the last twenty years as they wouldn’t recognize his medical degree.

She discusses how she and the only other Aisan kid in her class have an unspoken rule of not looking at each other or calling attention to one another as to not emphasize their Asianness.

As you can probably tell without having me list off a litany of other examples, this book heavily concentrates on race, identity, family, and self-control.

At the beginning of the novel, Ever is a shy, timid girl whose willing to give up her dreams of dancing because it’s what's expected of her after all her parents have sacrificed to raise her in America.

But then her mother sells her black pearl necklace to send Ever to Chien Tan, an immersion program in Taipei where thousands of Asian-American kids are sent for the summer, for the purpose of learning the culture, language, and other specialized skills like Chinese medicine, calligraphy, ribbon dancing and stick fighting.

Ever is reluctant at first, desperate to stay back and find a way to keep dancing, but as her mother literally throws her leotard in the dumpster, Ever knows it’s a losing battle.

So she goes. And she is amazingly transformed.

The rest of the book details Ever’s excursions with finding friends and love, immersing herself in the culture that Taipei has to offer, coming to terms with her own identity and race, growing up, making mistakes, hitting a low point, and then getting back up again to achieve her dreams and fight for what she believes in.

Now, the highlight of this book is definitely the representation, the talk of race and culture, and the actual experiences of Chien Tan, more commonly referred to by the kids who attend as Loveboat, drawn from the author Abigail Hing Wen herself.

Loveboat, as they call it, is an actual program that the author Wen and others attended and still attend. It’s obvious just from reading how much of Ever’s experience is drawn from the author’s herself and that IS ALWAYS AN AMAZING THING.

One of the first pieces of writing advice I Ever (hahahha sorry, not sorry) received was to write what you know. Wen does this and knocks it out of the park. Loveboat comes alive with her writing, flowing from page to page seamlessly.

She crafts it with such care and consideration that you feel like you’re there yourself, down to what the dorms look like with sticking doors, what they serve for breakfast, and the electives offered for academic selections. All of these little details brought such life and realism to the story and it made it an incredibly engaging read.

Add on Wen’s real talk of race, racism, identity, and the struggle for identity, and you indeed have a delectable concoction of raw representation from a person of color who has experienced these things first-hand.

Authors of color and representation in YA of characters of color have improved drastically in the last few years, but it’s still something to be expanded upon, drawn from, and encouraged and explored.

Wen’s story is almost entirely made of Asian teenagers of differing backgrounds and experiences, and it was honestly so nice to not read about another white girl from a white girl. The story was real and filled with culture and struggle, but also beauty, friendship, and acceptance.

All of these things hark back to why I call this book solid.

Now onto why I don’t call this book great.

I legitimately would have preferred if this book focused more on Ever’s identity as Ai-Mei, her struggle between wanting to be a dancer and not crushing her parents’ soul by rejecting the medical career they so want her to be in, and immersing herself in all the wonderful sights, smells, and experiences Taipei had to offer.

Of course, love and friendship and drama should play a role, this is YA after all, but personally I felt like the romance dominated the book almost entirely, shoving the questions of race and identity and struggle to the backdrop of a pretty redundant love triangle.

Which. We’re over the love triangle people, stop writing them.

But really, I understand that the two don’t need to be mutually exclusive, and oftentimes, Ever’s struggle with her race and identity went hand-in-hand with her struggles for romance, but there was JUST. SO. MUCH. OF. IT.

It was like an episode of the Bachelor if the Bachelor would stop casting white people as their main lead. Every other chapter was a pretty cliched rendition of some kind of romance trope: the bad boy that draws, the arrogant boy that predictably has a heart, but also a girlfriend, the so-called girlfriend flying out to Taipei, the evil stuck-up girl, literal running into chests moments, shirtless of course, and so many more to offer.

For an author doing incredible things on the front of representation and real talk about stereotypes, racism, and prejudice, I found her book pretty stereotypical of a YA romance itself.

There were several plot points that were also just incredibly predictable (the nude photos, my god, saw that from a mile away) that made reading this book just a little bit lackluster when I otherwise was really enjoying it.

Unfortunately, the biggest turn-off this book had for me other than the recycled plot and the ridiculous, predictable, rampant love triangle were the characters themselves. They all kind of...sucked.

They aren’t awful, by any stretch of the imagination, but they’re also not special either. Other than the fact that they’re Chinese, Chinese-American, or identify as another minority, and the implicit struggles and nuances that come with it, they were like any other archetypal character that I tend to dislike.

By that I mean that many of the characters I found extremely one-dimensional.

Each character had about two things about them that defined their whole characters.

Now, not to blind you with my nerdiness, but other than books, I also am quite the connoisseur of anime. This book, in a lot of ways, comes across as a printed form of anime to me.

There is a term in anime called Isekai which roughly translates to “accidental travel” and is saturated with shows all about people falling into magical worlds unpredictably.

Additionally (stay with me here), anime is also quite infamous for having very archetypal characters where one or two traits dominate their whole being so completely as that is the only thing about them that comes across.

Loveboat, Taipei in my eyes, is literally a print form of an Isekai. Which is not a compliment.

I really wanted to like Ever, Sophie, Rick, and Xavier, the predominant characters along with a whole cast of others. But I kind of...didn’t. Frankly, there wasn’t much to like or know about them.

Ever’s character was dominated by her love for dancing and her determination to break from her parent’s protective shell, Sophie was a bossy bitch, Rick was Wonder Boy incarnate, Xavier was brooding and artistic-see where I’m going here?

Even the side characters were all identified by one thing-Marc with politics, Matteo with anger, Benji with being baby-faced. I understand that this is one novel and that it’s extremely hard to flesh out characters and unfold nuances and depth, but I personally found Loveboat, Taipei to be lacking in this quality, exceptionally so.

Ever especially I found irritating. On some levels, I understand that Wen was trying to depict her as a flawed character who makes mistakes and learns from them, trying to represent the growth of her character and blooming into herself, but more often than not, I found her selfish, immature, and aggravating.

When you add on that Rick is head-over-heels in love with her (as is Xavier) for reasons that don’t really make sense or are legitimately earned in the story, then the romance feels forced and falls apart, hence me wishing Wen focused more on other elements rather than romance.

This plot contrivance, everyone, is what I lovingly call Bella Swan Syndrome-when a hot guy or vice versa falls in love with someone who legitimately doesn’t deserve it or the love is inorganic or just flat out doesn’t make sense.

Wen attempted the whole hate-to-love thing, which I love, but also which I genuinely think failed here due to the romance being subpar and undeserved.

Combine my lack of any real attachment to any character with the trite that was the romance, but mix it in with the praises above of realism and representation and you end at solid.

Recommendation: If you are sick of the white people, I hear you. If you’ve been looking for books heavily centered on POC characters or written by authors of color, then I’m with you there as well. This book is a great novel for discussions of race and identity and for those Crazy Rich Asians fans out there. However, do not expect this to be the pinnacle of romance, story, or characterization, which unfortunately, falls below average on this one.

Score: 6/10

#loveboat#loveboat taipei#abigail hing wen#poc#ya fiction#YA Books#YA literature#book blog#book#books#teen books#Teen Romance#teen fiction#romance#romance fiction#chinese american#book review#book reccs#ya book rec#book recommendations

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Month in Books: November 2019

Ninth House - Leigh Bardugo

Galaxy “Alex” Stern is the most unlikely member of Yale’s freshman class. Raised in the Los Angeles hinterlands by a hippie mom, Alex dropped out of school early and into a world of shady drug dealer boyfriends, dead-end jobs, and much, much worse. By age twenty, in fact, she is the sole survivor of a horrific, unsolved multiple homicide. Some might say she’s thrown her life away. But at her hospital bed, Alex is offered a second chance: to attend one of the world’s most elite universities on a full ride. What’s the catch, and why her?

Still searching for answers to this herself, Alex arrives in New Haven tasked by her mysterious benefactors with monitoring the activities of Yale’s secret societies. These eight windowless “tombs” are well-known to be haunts of the future rich and powerful, from high-ranking politicos to Wall Street and Hollywood’s biggest players. But their occult activities are revealed to be more sinister and more extraordinary than any paranoid imagination might conceive.

The White Album - Joan Didion

First published in 1979, "The White Album "is a journalistic mosaic" "of American life in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. It includes, among other bizarre artifacts and personalities, reportage on the dark journeys and impulses of the Manson family, a visit to a Black Panther Party press conference, the story of John Paul Getty's museum, a meditation on the romance of water in an arid landscape, and reflections on the swirl and confusion that marked this era. With commanding sureness of mood and language, Didion exposes the realities and dreams of an age of self-discovery whose spiritual center was California.

An Echo in the Bone - Diana Gabaldon

Jamie Fraser, erstwhile Jacobite and reluctant rebel, knows three things about the American rebellion: the Americans will win, unlikely as that seems in 1778; being on the winning side is no guarantee of survival; and he’d rather die than face his illegitimate son — a young lieutenant in the British Army — across the barrel of a gun. Fraser’s time-travelling wife, Claire, also knows a couple of things: that the Americans will win, but that the ultimate price of victory is a mystery. What she does believe is that the price won’t include Jamie’s life or happiness — not if she has anything to say.

Claire’s grown daughter Brianna, and her husband, Roger, watch the unfolding of Brianna’s parents’ history — a past that may be sneaking up behind their own family.

Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion - Jia Tolentino

Trick Mirror is an enlightening, unforgettable trip through the river of self-delusion that surges just beneath the surface of our lives. This is a book about the incentives that shape us, and about how hard it is to see ourselves clearly in a culture that revolves around the self. In each essay, Jia writes about the cultural prisms that have shaped her: the rise of the nightmare social internet; the American scammer as millennial hero; the literary heroine’s journey from brave to blank to bitter; the mandate that everything, including our bodies, should always be getting more efficient and beautiful until we die.

Three Women - Lisa Taddeo

It thrills us and torments us. It controls our thoughts and destroys our lives. It’s all we live for. Yet we almost never speak of it. And as a buried force in our lives, desire remains largely unexplored—until now. Over the past eight years, journalist Lisa Taddeo has driven across the country six times to embed herself with ordinary women from different regions and backgrounds. The result, Three Women, is the deepest nonfiction portrait of desire ever written.

We begin in suburban Indiana with Lina, a homemaker and mother of two whose marriage, after a decade, has lost its passion. She passes her days cooking and cleaning for a man who refuses to kiss her on the mouth, protesting that “the sensation offends” him. To Lina’s horror, even her marriage counselor says her husband’s position is valid. Starved for affection, Lina battles daily panic attacks. When she reconnects with an old flame through social media, she embarks on an affair that quickly becomes all-consuming.

In North Dakota we meet Maggie, a seventeen-year-old high school student who finds a confidant in her handsome, married English teacher. By Maggie’s account, supportive nightly texts and phone calls evolve into a clandestine physical relationship, with plans to skip school on her eighteenth birthday and make love all day; instead, he breaks up with her on the morning he turns thirty. A few years later, Maggie has no degree, no career, and no dreams to live for. When she learns that this man has been named North Dakota’s Teacher of the Year, she steps forward with her story—and is met with disbelief by former schoolmates and the jury that hears her case. The trial will turn their quiet community upside down.

Finally, in an exclusive enclave of the Northeast, we meet Sloane—a gorgeous, successful, and refined restaurant owner—who is happily married to a man who likes to watch her have sex with other men and women. He picks out partners for her alone or for a threesome, and she ensures that everyone’s needs are satisfied. For years, Sloane has been asking herself where her husband’s desire ends and hers begins. One day, they invite a new man into their bed—but he brings a secret with him that will finally force Sloane to confront the uneven power dynamics that fuel their lifestyle.

Based on years of immersive reporting, and told with astonishing frankness and immediacy, Three Women is a groundbreaking portrait of erotic longing in today’s America, exposing the fragility, complexity, and inequality of female desire with unprecedented depth and emotional power. It is both a feat of journalism and a triumph of storytelling, brimming with nuance and empathy, that introduces us to three unforgettable women—and one remarkable writer—whose experiences remind us that we are not alone

#ninth house#leigh bardugo#fantasy#horror#the white album#joan didion#essays#an echo in the bone#diana gabaldon#outlander#claire fraser#jamie fraser#trick mirror#jia tolentino#three women#lisa taddeo#non-fiction#fiction#california#historical fiction#time travel#booklr#bookworm#bookshelf#book lover#booklr community#adult booklr#romance#maggie wilken#historical romance

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Month in Books: November 2019

Ninth House - Leigh Bardugo

Galaxy “Alex” Stern is the most unlikely member of Yale’s freshman class. Raised in the Los Angeles hinterlands by a hippie mom, Alex dropped out of school early and into a world of shady drug dealer boyfriends, dead-end jobs, and much, much worse. By age twenty, in fact, she is the sole survivor of a horrific, unsolved multiple homicide. Some might say she’s thrown her life away. But at her hospital bed, Alex is offered a second chance: to attend one of the world’s most elite universities on a full ride. What’s the catch, and why her?

Still searching for answers to this herself, Alex arrives in New Haven tasked by her mysterious benefactors with monitoring the activities of Yale’s secret societies. These eight windowless “tombs” are well-known to be haunts of the future rich and powerful, from high-ranking politicos to Wall Street and Hollywood’s biggest players. But their occult activities are revealed to be more sinister and more extraordinary than any paranoid imagination might conceive.

The White Album - Joan Didion

First published in 1979, “The White Album "is a journalistic mosaic” “of American life in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. It includes, among other bizarre artifacts and personalities, reportage on the dark journeys and impulses of the Manson family, a visit to a Black Panther Party press conference, the story of John Paul Getty’s museum, a meditation on the romance of water in an arid landscape, and reflections on the swirl and confusion that marked this era. With commanding sureness of mood and language, Didion exposes the realities and dreams of an age of self-discovery whose spiritual center was California.

An Echo in the Bone - Diana Gabaldon

Jamie Fraser, erstwhile Jacobite and reluctant rebel, knows three things about the American rebellion: the Americans will win, unlikely as that seems in 1778; being on the winning side is no guarantee of survival; and he’d rather die than face his illegitimate son — a young lieutenant in the British Army — across the barrel of a gun. Fraser’s time-travelling wife, Claire, also knows a couple of things: that the Americans will win, but that the ultimate price of victory is a mystery. What she does believe is that the price won’t include Jamie’s life or happiness — not if she has anything to say.

Claire’s grown daughter Brianna, and her husband, Roger, watch the unfolding of Brianna’s parents’ history — a past that may be sneaking up behind their own family.

Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion - Jia Tolentino

Trick Mirror is an enlightening, unforgettable trip through the river of self-delusion that surges just beneath the surface of our lives. This is a book about the incentives that shape us, and about how hard it is to see ourselves clearly in a culture that revolves around the self. In each essay, Jia writes about the cultural prisms that have shaped her: the rise of the nightmare social internet; the American scammer as millennial hero; the literary heroine’s journey from brave to blank to bitter; the mandate that everything, including our bodies, should always be getting more efficient and beautiful until we die.

Three Women - Lisa Taddeo

It thrills us and torments us. It controls our thoughts and destroys our lives. It’s all we live for. Yet we almost never speak of it. And as a buried force in our lives, desire remains largely unexplored—until now. Over the past eight years, journalist Lisa Taddeo has driven across the country six times to embed herself with ordinary women from different regions and backgrounds. The result, Three Women, is the deepest nonfiction portrait of desire ever written.

We begin in suburban Indiana with Lina, a homemaker and mother of two whose marriage, after a decade, has lost its passion. She passes her days cooking and cleaning for a man who refuses to kiss her on the mouth, protesting that “the sensation offends” him. To Lina’s horror, even her marriage counselor says her husband’s position is valid. Starved for affection, Lina battles daily panic attacks. When she reconnects with an old flame through social media, she embarks on an affair that quickly becomes all-consuming.

In North Dakota we meet Maggie, a seventeen-year-old high school student who finds a confidant in her handsome, married English teacher. By Maggie’s account, supportive nightly texts and phone calls evolve into a clandestine physical relationship, with plans to skip school on her eighteenth birthday and make love all day; instead, he breaks up with her on the morning he turns thirty. A few years later, Maggie has no degree, no career, and no dreams to live for. When she learns that this man has been named North Dakota’s Teacher of the Year, she steps forward with her story—and is met with disbelief by former schoolmates and the jury that hears her case. The trial will turn their quiet community upside down.

Finally, in an exclusive enclave of the Northeast, we meet Sloane—a gorgeous, successful, and refined restaurant owner—who is happily married to a man who likes to watch her have sex with other men and women. He picks out partners for her alone or for a threesome, and she ensures that everyone’s needs are satisfied. For years, Sloane has been asking herself where her husband’s desire ends and hers begins. One day, they invite a new man into their bed—but he brings a secret with him that will finally force Sloane to confront the uneven power dynamics that fuel their lifestyle.

Based on years of immersive reporting, and told with astonishing frankness and immediacy, Three Women is a groundbreaking portrait of erotic longing in today’s America, exposing the fragility, complexity, and inequality of female desire with unprecedented depth and emotional power. It is both a feat of journalism and a triumph of storytelling, brimming with nuance and empathy, that introduces us to three unforgettable women—and one remarkable writer—whose experiences remind us that we are not alone

#ninth house#leigh bardugo#alex stern#darlington#grishaverse#joan didion#white album#california republic#an echo in the bone#diana gabaldon#outlander#claire fraser#jamie fraser#brianna mackenzie#roger mackenzie#historical fiction#historical romance#time travel#sci fi#trick mirror#jia tolentino#essays#three women#lisa taddeo#non-fiction#fiction#journalism#bookblr#bookaholic#bookblogger

1 note

·

View note

Text

Five Potential Side Effects of Transracial Adoption

by Sunny J Reed

A trans- anything nowadays is controversial, but one trans- we don’t hear enough about are transracial adoptees. This small but vocal population got their title from being adopted by families of a different race than theirs — usually whites. But adoption, the so-called #BraveLove, comes with a steep price; often, transracial adoptees grow up with significant challenges, partly due to the fact that their appearance breaks the racially-homogenous nuclear family mold.

I am transracially adopted. My work is an outgrowth of my experience, research, and conversations with other members of the adoption triad; that is, adoptees, birth parents, and adoptive parents. This piece is a response to the misunderstandings and assumptions surrounding transracial adoption, and I hope it brings awareness to some rarely-discussed side-effects of the practice. While this isn’t an exhaustive list, by any means, these are just a few of the struggles that many transracial adoptees grapple with on a daily basis.

1. Racial Identity Crises, or “You Mean I’m Not White?”

Racial identity crises are common among transracial adoptees: what’s in the mirror may not reflect which box you want to check. I grew up in a predominantly white town that barely saw an Asian before — let alone an Asian with white parents. Growing up, I’d forget about my Korean-ness until I’d pass a mirror or someone slanted their eyes down at me, reminding me that oh yeah, I’m not white.

There’s a simple explanation for this confusion: “As members of families that are generally identified as white,” writes Kim Park Nelson, “Korean adoptees are often assimilated into the family as white and subsequently assimilated into racial and cultural identities of whiteness.”

Being raised in an ethnically-diverse area with access to culturally-aware individuals would help keep external reactions in check, but still belies the race-based role you’re expected to play in public. Twila L. Perry relates an anecdote illustrating the complexities of being black but raised in a white family:

“A young man in his personal statement identified himself as having been adopted and reared by white parents, with white siblings and mostly all white friends. He described himself as a Black man in a white middle-class world, reared in it and by it, yet not truly a part of it. His skin told those whom he encountered that he was Black at first glance, before his personality-shaped by his upbringing and experiences-came into play.”

Positive racial identity formation might be transracial adoption’s greatest challenge since much of the dialogue related to race and color begins at home. Multiracial and interracial families sometimes have difficulties finding the language to discuss this problem, so it’s an uphill climb for transracial parents (Same Family, Different Colors is a great study on this).

Parents can begin by talking openly about their child’s race. Acknowledging differences is not racist, nor does it draw negative attention to your child’s unique status in your family. Instead, being honest about it places your child on the path to self-acceptance.

2. Forced Cultural Appreciation (à la “Culture Camps”)

Picture culture camp like band camp (no, not quite the band camp talked about in American Pie). The big difference is that, unlike band camp, culture camp expects you to learn heritage appreciation in the span of just one week instead of how to better tune your trumpet. Sometimes adoption agencies sponsor such programs, designed to immerse an adoptee in an intense week or two of things like ethnic food, adoptee bonding, and talks with real people of your race, as opposed to you, the poseur.

These camps often get the side-eye — and rightfully so. Critics argue that “fostering cultural awareness or ethnic pride does not teach a child how to deal with episodes of racial bias.”

Much like part-time church-going does little in the way of earning your way to the Pearly Gates, once-yearly visits with people that look like you won’t make you a real whatever-you-are. I know culture camps aren’t going away, so a better solution would be using these events as supplements to whatever you’re doing at home with your child, not as the sole source of heritage awareness. And yes, racial self-appreciation should be a lifelong project.

3. Mistaken Identities -aka — “I’m Not the Hired Help”

Transracial adoptees’ obvious racial differences provoke brazen inquiries regarding interfamilial relationships. Having “How much did she cost?” and “Is she really your daughter?” asked over your head while being mistaken for your brother’s girlfriend does not contribute to positive self-image. It publically questions your place in the only family you’ve ever known, setting the stage for insecure attachments and self-doubt.

Mistaken identities aren’t just awkward, they’re insulting. Sara Docan-Morganinterviewed several Korean adoptees regarding what she describes as “intrusive interactions,” and found that “participants reported being mistaken for foreign exchange students, refugees, newly arrived Korean immigrants, and housecleaners. [One adoptee] recalled going to a Christmas party where someone approached her and said, ‘Welcome to America!’”

Obvious racism aside, transracial adoptees often find themselves having to validate their existence, which is something biological children are unlikely to face. Docan-Morgan suggests that parents’ responses to such interactions can either reinforce family bonds or weaken them, so expecting the public’s scrutiny and preparing for it should be a crucial piece in transracial adoptive parent education.

4. Well-Meaning, Yet Unprepared Parents

Sure, they’ll be issued a handy guide (here’s one from the 1980s) on raising a non-white you, but beyond a few educational activities and get-togethers with other transracial families, they’re on their own (unless online forums count as legitimate resources).

Some parents may good-heartedly acknowledge your heritage by providing dolls and books and eating your culture’s food. Others may mistakenly adopt a colorblind attitude, believing they don’t see color; they just see people. But, as Gina Miranda Samuels says, “Having a certain heritage, being given books or dolls that reflect that heritage, or even using a particular racial label to self-identify are alone insufficient for developing a social identity.”

Regarding colorblindness, Samuels explains that it risks “shaming children by signaling that there is something very visible and unchangeable about them (their skin, hair, bodies) that others (including their own parents) must overlook and ignore in order for the child to be accepted, belong, or considered as equal.”

As mentioned in point #1 above, talking about color while acknowledging your child’s race in a genuine, proactive way can counteract these problems. This means white parents must acknowledge their inability to provide the necessary skills for surviving in a racialized world; sure, it might mean admitting a parenting limitation, but working through it together might help your child feel empowered instead of isolated. Talking to transracial adoptees — not just those with rosy perspectives — will be an invaluable investment for your child.

I’d also suggest that white parents admit their privilege. White privilege in transracial adoption is beautifully covered by Marika Lindholm, herself a mother of transracially adopted children. Listening to these stories, despite their rawness, will help you become a better parent. By acknowledging that you may take for granted that being part of a societal majority can come with dominant-culture benefits, you open your mind to the fact that your transracial child may not experience life in the same way as you. It doesn’t mean you love your adopted child any less — but as a parent, you owe it to your child to prepare yourself.

5. Supply and Demand

During the early decades of transracial adoption (1940–1980), racial tensions in the United States were so high that few people considered adopting black babies. People clamored for white babies, leaving many healthy black children aging in the system. (Sadly, this still happens today.) And since adoption criteria limited potential parents to affluent white Christians, blacks encountered near insurmountable adoption roadblocks.

Korea offered an easy solution. “Compared to the controversy over adopting black and Native American children,” says Arissa H. Oh, author of To Save the Children of Korea, “Korean children appeared free of cultural and political baggage…Korean children were also seen as free in another important sense: abandoned or relinquished by faraway birth parents who would not return for their child.”

After the Korean War, adopting Korean babies became a form of parental patriotism — kind of like a bastardized version of rebuilding from within. During this time, intercountry adoption fulfilled a political need as well as a familial one. Eleana H. Kim makes this connection as well: “Christian Americanism, anti-Communism, and adoption were closely tied in the 1950s, a period that witnessed a proliferation of the word “adoption” in appeals for sponsorship and long-distance fostering of Korean waifs and orphans.”

Although we’ve seen marked declines in South Korean adoptions, intercountry and transracial adoptions continue today, retaining some of their politically-motivated roots and humanitarian efforts. We need to keep this history in mind since knee-jerk emotional adoptions — despite the time it takes to process them — have serious repercussions for the children involved.

But we can make it better

None of this implies that transracial adoption is evil. Not at all. Consider this missive as more of a PSA for those considering adoption and a support piece for those who are transracially adopted. I’m aware that I’ll receive a lot of pushback on my work, and that’s okay. I’m writing from the perspective of what I call the “original transracial adoption boom,” and I consider myself part of one the earliest generations of transracial adoptees. Advancements in the field, many spurred by adoptees like myself, have contributed to many positive changes. However, we still have work to do if we’re going to fix an imperfect system based on emotional needs and oftentimes, one-sided decision making.

(source in the notes)

#transracial#transracial adoption#adoption#racism#transracial adoptees#this is pretty good#tq posts#long post

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Double Consciousness

“One ever feels his twoness, -- an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

― W.E.B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk

For many years, I’ve dodged commitment to the identity of a writer because I’ve been afraid of the backlash that would come with my words. I tend to have an out-of-body experience when I put words on paper. They become 3D powerful images, a kind of synesthesia occurs, and arrows whistle towards a target...and there are always casualties.

So, I stopped writing, avoiding opinion articles, blogs like this one, essays, controversial FB posts, because, if people actually read what I had to say beyond the armor of poetry or a creative piece, they’d feel quite different about me as a black female. And I couldn’t risk that.

2.5 Words

I’ve been conscious of myself as a black female since the third grade. Once, I had forgotten something on the PE field, and while walking back to get it, a little boy, on the other side of a fenced in playground, yelled out to me, “you're black.”

2.5 words without an ounce of hostility or error in them.

He didn’t taunt or provoke me, but when I got back to the car, I just remember feeling... wrong. Not different, just faulty or wrong somehow.

I dreamed up a clever retort too late which was, “...black is a color in the crayon box.” I guess I’ve always been a creative and insightful thinker....

This boy was 6 or 7 years old, riding a schoolyard tricycle; I didn’t even know him.

Yet, after that non-hostile experience, I was terrified to walk by that playground again.

Remember, he only vocalized his observation that I am indeed black. I still recall those sharp feelings I felt despite the words being true and true.

But I wonder why he believed it was his prerogative to point it out, to make me notice I was not the same skin color.

Safely Black

This experience was pretty much my introduction to learning I was black. Of course I knew I was not white, but I didn’t know that other people, especially kids, cared that I was not white. From there, it was being laughed at because I said “ax” instead of “ask.” One of my classmates saying, “ew, gross” because of the product in my hair, which was touched without permission. Years later, it was the shade of my knees, which are darker than the rest of my legs. Now, it’s trying to decide if I should purchase a wig for an interview or self-identify on a job application, never sure if my natural hair or shade of melanin will be the undisclosed reason behind “not the right fit.”

From K - 12th grade, I attended predominantly white, private Christian schools. Overt racism never happened to me. Yet, not once did I ever feel safe among my teachers and friends to be a black female... to fully explore what that even means. I was always hiding something.

Yes, I had meaningful friendships and positive experiences, but never as my self.

I feel that I have lived my life dressed up by a host of unsolicited tailors specializing in the way I speak, how I present myself, how I must act inside of stores, the opinions I voice, and the list goes on.

I have learned how to become invisible and nondescript so that I can be “safely” black.

And it’s been to my detriment.

An Angry Black Woman

Many people are feeling shocked by the recent events caught on video and shared via social media. Without me even mentioning the race of this little boy, it will be inferred that he was white. Because, even if some “don’t see color,” everyone knows that Asians, Hispanics, Native Americans, Caucasians, and every other group of people, have worked very hard to point out how we are not the same skin color, and somehow a lesser pedigree of human, for generations.

Until a few days ago, I had remained pretty quiet on the topic of racial injustice--always looking for ways to share my experiences, relate my double consciousness to friends, while not offending anyone.

But right now, black people are being threatened and murdered on live cameras by white people.

And for some reason, despite my coveted relationships with white friends, for several years, I have nursed a fear that it would damage something between us if I commented on any news story about race.

I’ve believed it would alter our friendship if I became a fist-raised Black Power advocate. It would make things awkward if I were to steadily post black injustice on my newsfeed. That, if I said I’m so angry that police are killing little boys and young men, I would be viewed as, wait for it, an angry black woman. Nevermind the truth that I feel wrecked from my core; I’d just rather not make any waves.

That’s what’s been on my mind. Not exclusively the horror of the murders I’ve been stockpiling in my conscious since a young girl, but the fact that I actually know people who would eventually wish I’d stop posting the “angry racist stuff,” and stop trying to “take us back to the past.”

Bullets of Truth

But this is my own mess, my own web of nonsense because I have cultivated and catered to this twisted sense of peace among all men when I shonuff’ know there ain’t been no peace cuz no cops are walkin’ around viewing my black brothers as men.

My shame is that I know I have denied myself and my friends the conversations about what it really means to be black in America BEFORE we were shown these awful attacks. It’s not like I didn’t know it was happening.

But I have been so afraid to put my bullets of truth out there--mainly because you learn, way back in elementary school, when you are black, you just don’t talk about being black with white people because they will somehow make it about how they feel wronged and attacked. You just lock up that door and know what you know.

Except, I can’t feel anything but sick lately-- like I have to projectile vomit my self up from the place I’ve swallowed my self to become fiercely black, once and for all, and unabashedly own what that little boy “accused” me of being.

To finally say out loud, ”No, I am not the whitest black friend you know.”

To shoot down, “You sound white on the phone.”

To reject, “You don’t act like other black people.”

To refuse, “You’re very articulate for a black person.”

To say, “I’m disinterested in being the official tour guide of Black History month” because to be honest, I am still trying to understand what it means to even be black.

Black in America

My mother’s hard decision for my life was to go the route of private education on the other side of town, or attend the public schools we were zoned for in a less desired part of town (by no fault of the town, because lines were redrawn on purpose.) The outcome was me, immersed in a homogenous environment where I got a pretty decent education, but striving to fit in, losing my cultural heritage, pride and identity in progressive stages to the point my mother actually asked me in high school did I want to be white. Whenever I spent time in the black community, I couldn’t quite find my foothold there either, because they too thought I was “trying” to be white.

I don’t regret her choice, but I, as a parent, now know what choosing the first one meant. There are times I am not sure who I am when it comes down to the spectrum of black identity, and it’s sad, confusing, and alienating.

And honestly, I, along with many in my community, don’t have enough moments of peace to experience true self-discovery, to nurture who that person really is.

As soon as we’re proud of Barack and Michelle Obama or overjoyed about the historical Black Panther film or inspired by the shocking legacy of Katherine Johnson or choose to kneel with Colin Kaepernick or feel paranoid by the Confederate flag or unified under the banner of #BlackLivesMatter -- a whole lot of people, including the president of the United States, feel it’s their prerogative to tell us who we are for us [re:thugs]--and that narrative is never, ever good.

We are constantly trying to push it out, fighting cops for our kids’ lives, warding off suspicions, navigating extreme violence and poverty in our own community, and trying to prove our value and worth for school and career, while raising our babies to be proud of their skin color, our beautiful brown babies, who, as soon as they graduate Kindergarten, will cease to become non-threatening.

By the way, we are processing all of this, while watching white people protest masks and quarantine with assault rifles. In 2014, Tamir Rice was shot dead for having a toy gun. He was 12.

Under the Radar

So, I’ve come to this point, feeling like it’s crazy and impossible that I’m literally living through some of the things in my mother’s lifetime, that I must raise my daughter with a keen awareness that not all people are treated equally, even when the Constitution declares we are.

That I must actually teach her that even though the “colored only” signs are gone, the stone place of men’s hearts from where the words originated still exist. And they will mean it and enforce it with all the boldness of the Jim Crow era, just under the radar.

I’ve been trying to understand why in the world I am being so affected by this now, so much that it alters my mood and impacts productivity, why I feel like I have to force myself to be positive and hope for change. Is this what it also means to be black? To stir up my ancestors’ concoction of will, determination, resilience, and sing my own kind of Negro spiritual, and march my way to freedom? No wonder they were so strong!

I am cognizant of the fact that there are many great white men and women who work in the armed forces, and in law enforcement to protect all people in America. And I know there are those have worked in the past to abolish laws and helped to enact civil liberties for people of color.

I also know that it took the braveness from the likes of Frederick Douglas and Harriet Tubman and W.E.B. Dubois to shed light on the black experience...so together these powerful people could push change forward with a vengeance.

I am nowhere near as proficient in elocution as they, but this is my piece. I’m finally saying something about what it means to be black in America, but I am also feeling like that’s not enough.

The White Wall

I have many friends who are parents and who are educators and who are the complex cocktail of both.

Black people have not ever wanted to educate their white friends about what this terror feels like, and honestly, we shouldn’t have to because-- internet.

But I am realizing, with my own education in a predominately white environment, I didn't learn anything from my teachers about me and my world.

Nothing truly existed beyond the white wall--white writers, white poets, white leaders, white composers, white heroes, and Martin Luther King Jr.

From K - 12th grade, what I learned about the realities of being black wasn't taught by teachers or textbooks. The little I did learn was by being in the midst of my community, and eventually reading and pursuing and chasing after knowledge.

Therefore, it’s positively unrealistic to imagine that white people know much at all about the black experience. And both public and private education do not place importance on real diversity. Now, with the visual horror of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd, I venture to believe, for many white people, these past few weeks have been pretty much earth shattering.

But why is knocking down this wall and learning about the black experience (and other races and ethnicities) important?

When a white person’s basic lifestyle is free from external conflict, the tendency is to want to live there and only there. Problematically, she will grow increasingly out of touch with the world beyond her (and perhaps surrounding her if people of color have come into her world). But she will fail to see the good and the bad, except for this: negative media will only show her the bad, and tell her how to think, and what to believe about everyone else who looks different than her, subliminally, judgmentally, until eventually she behaves in the audacious, debased manner of Amy Cooper, a white woman who knew what the fatal consequences would be for a black man if she simply called the police to say she was feeling threatened, and to have had the presence of mind to wield it like a weapon.

A Gaping Chasm

Learning about the black experience is important because Amy Cooper probably did not wake up believing she was a racist or even had a racist bone in her body. But she knew that she was white and he was not, and in her anger, decided to weaponize her whiteness by calling the police on a black man, which depending what “bad apple” was on duty, could have ended his life--too.

That is how it works. It doesn’t always end in loss of life, but always ends in loss of masculinity, loss of spirit, loss of soul, loss of faith, loss of trust; it just ends in loss.

When you don’t fight to change the system, you become part of the system.

So, unless (or until) a white family has been very intentional, they and their children are not learning about the black experience.

Even when teaching my child about the origins of America and the Civil War and Reconstruction, I had to be intentional, essentially going back to school because there are things that were blatantly omitted from my years of learning and were still being omitted for hers if I did not break out from the wall.

To put this in perspective, I was in college when I learned there were accomplished black leaders besides Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks. I was in my 30s when I heard black women and NASA in the same sentence together.

My mom had Black America encyclopedias, and she wore her Afro proudly with a fist in the air, but she trusted my education to the school system--the private, Christian school system, and they emptied out all of the other crayons in the box, and asked me (and my classmates) to only color with the white crayon.

So, for white families, between choice of schools, places of worship, and by not having or seeking out any predominately black cultural experiences, there is a gaping chasm between us.

One that I’d like to lay a log across for my part.

Gateway for Change

Anyone who knows me knows I’m a sucker for kids. I’ll bleed for them. I’ve spent the better years of my life surrounded by them. And from them, I’ve learned they are not afraid to learn something new when it’s presented to them in a digestible manner. I’ve been thinking a great deal about kids lately--my nephews and nieces, my former English students and chess kids, my friends’ children....They have heard the chatter, seen our reactions, and may have even seen the same videos on YouTube.

All of these kids, our kids, are being shaped by this society, and they will one day become adults who must interact and deal with each other politically, socially, emotionally, physically, spiritually, economically, and mentally.

So who is educating them? Who is explaining empathy and justice and teaching love and acceptance? One thing this virus has taught our nation is that parents are capable of teaching their children too. No matter how great your school system is, they are not going to teach your children about race relations with any consequence.

Education is the single most important gateway for change. Yes, there are people who will perpetuate ignorance regardless because they are blocked in by their incestuous beliefs, but for those who wish to break out of that crippling heritage or emerge from the silos of their communities -- with empathy and insight, you have to learn something new and share the wealth.

You have to know what’s being taught inside the homes of black families, multi-racial families, Arab families, Asian families, and most recently, the Navajo nation. Buy books with diverse characters by diverse authors --for yourself, your children, your students. Watch films with diverse casts. Find positive images and media that celebrate the success and vitality of black excellence.

Listen to the lessons and conversations we've been having amongst ourselves for generations and still teach today. White society is not a bad society. Black society is not a bad society. We are not going to see eye to eye on many many things, but we can agree that every life is valuable.

I do not represent every black person, nor does every black person hold my same views.

But absolutely, we do not live or experience life the same way as our white friends and family. This truth is not a victimhood or disadvantage we seek to revel in or exploit, nor does it devalue the privileges others know and experience. Within our own community, we definitely have very real problems to address, but right now, daily life should not be a mental obstacle course that’s filled with active minefields laid out for us everyday.

Lately, it just feels like no matter what we do or don’t do, the fatalities are adding up, and wicked people in this country are treating the taking of our lives like points in a video game.

As you think about these words, and listen to the stories of these young black men, who are being hit the hardest with racial injustice, dare greatly to share widely within your community.

youtube

“But we do not merely protest; we make renewed demand for freedom in that vast kingdom of the human spirit where freedom has ever had the right to dwell:the expressing of thought to unstuffed ears; the dreaming of dreams by untwisted souls.”

― W.E.B. DuBois

Pixabay photos used by permission. Video sourced by New York Times.

0 notes

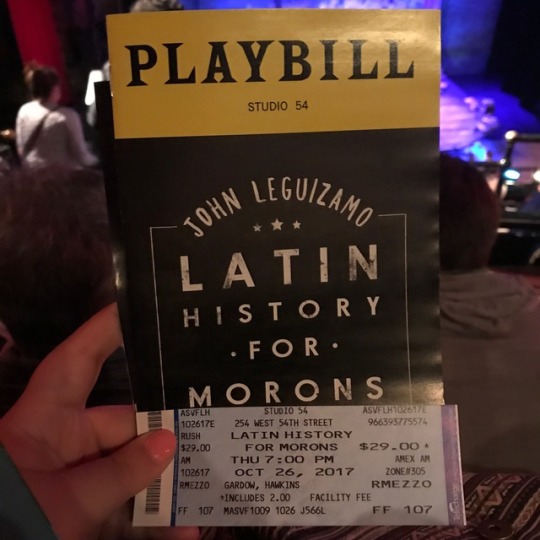

Photo

About a month ago, I went with my roommate to go see John Leguizamo’s Latin History for Morons. As I like going into shows as blind as possible, I knew essentially nothing about what would take place over the course of this 100-minute, one-act play. A month later, I still feel that it is one of the most important shows I’ve seen in the three and a half years I’ve been going to school in New York--and I’ll try my best to explain how, and why.

Latin History for Morons is a play highlighting and educating people on Latino erasure in the context of how damn important they are to history. There’s more to it than that, obviously, but that’s kind of the premise.

The “plot” of this show is that John Leguizamo’s son was being picked on at school for his ethnicity (half-Jewish, half-Latino, though the bullying focused mostly on the Latino half), and he didn’t know how to validate/prove that his culture and the people that came before him were worthy of being valued; in conjunction, he was also supposed to do a personal “hero” project for school, but was struggling with the assignment because he couldn’t find people like him to look up to. Both of these things spurred John Leguizamo to look high and low for the history and people and accomplishments that his kids weren’t being taught about in school, and in turn find this sought-after validation for himself as well.

John Leguizamo relayed this story to us in a pseudo-educational format (I.e. he was in a room full of books and research and used a chalk board, as if actually sitting us down to educate us), but it was full of hilarious, shocking, devastating, and too real moments. It was actually really enlightening and eye-opening, not in the sense that I didn’t know any of what he was teaching us (though there were some finer history points that I didn’t know, most likely because I’m not really a history person), but in the sense that I’ve always struggled with knowing and understanding and connecting to my cultural background, and though it’s different for every person because there’s just such a variety of Latin ethnicities and immersion, it was nice to see that I’m not the only one who has issues connecting or finding validation in it.

I found myself relating remarkably to the son, even though he’s never actually seen and only gets a voice through his father’s imitations. But other than being bullied for his Latino heritage (which I’ve also experienced, though albeit in a different way), he’s a half-Latino, half-Jewish kid who lives in America. And while the show makes no real reference to the degree in which this kid embraces his Jewish heritage, it focuses on his struggle with trying to figure out the value of his Latino heritage and how to fit that into his life in a positive way. It’s hard because he doesn’t live a 100% Latino life—he has another culture (Jewish) and another world (modern America) that he can choose to embrace instead—and fighting to figure out how your culture fits into the modern world you live in is really tough. It’s part lack of exposure to the importance of these things, through both school education and familial education, and part being unable to reconcile this unique thing about you that not every person has in their life and put that part of you in the important place it belongs. It’s much easier to never learn about these things and just go along being an American kid. It’s a choice I half-made a long time ago, but it’s one I’ve always wanted to rectify—I’ve just never known how. Because for those lagging behind like myself, all of the wonderful things I should know are seemingly inaccessible. You don’t know where to start, where to look, what pertains to what exactly it is you’re searching for, because it’s not something that most people are interested in or deem important. It doesn’t have the appropriate exposure it deserves.

For me, the struggle is exacerbated by the clash between my heritage and my ethnicity. I look very white. My half-sisters ALSO look very white. The difference, though, is that my whiteness comes from my mom, who is German, French, Luxembourgian, essentially what she herself refers to as “mixed white”; my sisters, on the other hand, get their whiteness from their mother, who is Cuban—a Hispanic whiteness. That’s the difference between us ethnicity wise. Culturally, they were raised in a completely Latino and Hispanic household; they had exposure to that language and music and those holidays and traditions. I was raised in a half-Hispanic, half-white-American household. Though my mother is all of these European things, there aren’t any traditions from them that her family really knows or practices. My dad by the time I was born had been in America for probably about 30 years, and while he still held on to some of his cultural traditions, it was hard to pass those things along to me for a variety of reasons.

Additionally, I would definitely put myself under the white-passing category—but it’s even more than that, because I AM half white. My dad isn’t 100% native Mexican either (there’s some French and Spanish, and I’m sure there’s other stuff mixed in there too because colonization is a bitch my friend), but that was his world growing up. There wasn’t a choice between cultural heritages for him, it just was. I had that choice, to whatever degree I could consciously choose such a thing at such a young age. I chose to just live my life as a “mixed-white” person, not even really understanding what and how much I was giving up.

The parts of my Mexican side that shine through have always made me very proud. But I’ve always felt like I’ve had the option of not acknowledging it. Sometimes saying I’m white feels like it’s a lie, and sometimes it doesn’t—because I’ve always questioned my claim to a heritage I’ve never really known, never experienced in full force--one I wasn’t raised in but I still have tangled ties to. I struggle to find where I fit in this culture--and then when I try to immerse myself in it, in its beautiful traditions and important advancements and rich histories, they’re no where to be found. Even the people who belong to these heritages cannot find where they fit into the world, and that’s disappointing to the point of being damaging. I think it’s important for everyone to learn about all sorts of cultures and traditions--but if they’re not first and foremost well-versed in their own, how can we preserve and share and teach these things to others?

I don’t know whose job it is to decide these things. Whether it was a higher up school system decision or the American tendency to quite literally white-out everything and everyone that isn’t white. But these things need to be taught and shared. They need to be treated with respect, and valued for their true importance to the fabric of the entire world’s history.

I don’t know whose job it is to change these things, but John Leguizamo, for his sake, his son’s sake, and my sake, has taken it upon himself to start the conversation. And I thank him for that.

#my posts#Latin History For Morons#John Leguizamo#broadway#off-broadway#theatre#new york city#the public#frida kahlo#latino#latinx#latina#hispanic

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

Former Vice President of the United States Joe Biden speaking with attendees at the Presidential Gun Sense Forum hosted by Everytown for Gun Safety and Moms Demand Action at the Iowa Events Center in Des Moines, Iowa. August, 2019. (photo: Gage Skidmore)

Even among people who really want Joe Biden to be the next President of the United States, there is very little enthusiasm. Joe Biden has an even bigger enthusiasm gap than Hillary Clinton did in 2016.

He is a former Vice President, a former Senator- but his in-person events, and now his online events, aren’t very well attended. Unlike the Hillary Clinton campaign, which played off Clinton’s low numbers at campaign functions as a deliberate strategy to an overly-credulous press willing to buy that nonsense, the Biden campaign has just assiduously avoided talking about it.

Biden himself gets a little upset, even visibly flustered when the subject of the lack of enthusiasm for his campaign is raised. He points out, with good reason, that he has managed to become the de facto Democratic nominee in spite of that.

He is right, of course; Joe Biden has managed to cinch the nomination, in spite of the prevailing lack of enthusiasm for Joe Biden, his poor performances during the debates and his lackluster fundraising.

But it wasn’t the strength of his campaign that carried Biden across the finish line, if indeed he has crossed the finish line. It took a massive and concerted effort by Democratic leadership, spear-headed at last by a decisive endorsement by Rep. Jim Clyburn of South Carolina, for Biden to advance.

Why?

If Joe Biden was and remains the best candidate to beat Donald Trump, why didn’t Joe Biden’s campaign do a better job of convincing everyone of that?

More specifically, if Biden was counting on the African-American vote to carry him in the primary contest, as was his constant refrain on the campaign trail when he lost all the primaries that came before South Carolina, why wasn’t Biden more proactively approaching Black community leaders for their help?

More importantly, why wasn’t the Biden campaign doing this?

Influential African-American leader Jesse Jackson endorsed Bernie Sanders on March 8. This fact was lost in the constant drama of the primaries, as was the reason Jackson gave for supporting Sanders when most of the African-American community favored Joe Biden:

Joe Biden never asked for Jesse Jackson’s endorsement.

That might have been a forgivable oversight. But Biden’s team hasn’t exactly been covering itself in glory courting the African-American community.

Which brings us to Charlamagne Tha God and the 18 minute appearance Joe Biden made on his hit morning show, The Breakfast Club. Biden avoided it longer than other candidates running for the Democratic nomination.

Charlamagne Tha God is influential in the young Black community. This interview was an all-important chance for Joe Biden to show that he wasn’t taking the Black vote for granted.

Joe Biden blew it. Or rather, Biden’s team caused him to blow it.

Not because Biden erupted, “if you don’t know if you’re voting for me or Trump, you ain’t Black!” after the host asked him what Biden planned on doing for the Black community if elected.

During the rest of the interview, Joe Biden hardly distinguished himself. And there was no reason for it but pure laziness, failure to plan ahead; failure to take the African-American community seriously as a constituency.

Many people may have never heard of Charlamagne The God; but he isn’t unknown. Charlamagne Tha God wrote an autobiographical book in 2017: “Black Privilege”. In it, CTG describes his whole life, his moral philosophy; everything.

It that book, Charlamagne Tha God- aka Larry, Cowboy and Julie’s son from Monck’s Corner South Carolina- gave a politician, and that politician’s advance guard, everything they could possibly want or need to impress the audience and hosts of The Breakfast Club.

If anyone on Biden’s team were to have read this one book- it isn’t even that long, and on the audiobook version, Charlamagne reads it himself- Biden could have knocked that interview out of the park and deeply impressed the Black community listening.

Charlamagne Tha God loves the truth; he hates lies and liars. He is so committed to the truth, he has taken multiple beatings in his life solely because he refused to lie or pull punches.

CTG loves truth so much, he spends multiple chapters in his book on it. He mentions specifically the strategy his likes to use to diffuse potentially embarrassing truths about himself.

“The Eight Mile Rule”

Being deeply immersed in Hip-Hop and Rap culture, Charlamagne Tha God references the moment in Eminem’s semi-auto biographical film “8 Mile” when “B-Rabbit”, Eminem’s character, enters the last rap battle against his most bitter enemy.

Instead of waiting to be insulted, Rabbit raps every embarrassing truth about himself with which his enemy might attack him: “I know everything he’s got to say against me: I am white, I am a f#$% bum, I do live in a trailer with my mom. My boy Future is an Uncle Tom.”

Joe Biden should have done this.

Knowing Biden’s record of authoring the 1990’s crime bill which has unfairly incarcerated so many young Black men in America for long sentences in the years since; knowing his record of making racist “gaffes”; knowing Charlamagne Tha God’s fervor for the truth, Joe Biden should have come out swinging…with The Truth.

“I made a mistake. I’m sorry. There is no excuse for it. I was wrong. But I helped elect the first African-American president and, if you give me a chance, I can help undo my past mistakes and make sure the next Black President of the U.S. isn’t confined to a jail cell, or lacking educational opportunities, or killed in the streets.”

Charlamagne Tha God is highly intelligent- his mother was a teacher and he was a self-professed “nerd” growing up- with a very curious and flexible mind. He would have known that Biden must have read his book. But Biden would have even gotten bonus points for admitting he had read Charlamagne’s book in order to prepare himself. Even more points if he had admitted reading the 48-Laws of Power, as CTG has, and applying that, too.

For a real laugh, Biden could have opened with, “Hello, my name is Joe Biden and I am not a white devil.” Anyone who has read Charlamagne’s book would understand this joke; any person familiar with the works of authors like Malcom X and Elijah Muhammed would understand as well, and appreciate the humor.

On a silver platter- in black and white, complete with convenient audiobook- radio host Charlamagne Tha God gave everything a guest on his show might need to be successful, even mentioning how much he likes people who are hard-working, diligent and willing to go the extra mile to be prepared.

Except, obviously, no one on the Biden campaign bothered to read it.

Why not? They have had plenty of downtime- no campaign events to plan, no in-person meetings with donors to conduct. The book was released in 2017.

We can tell no one on Biden’s team read Charlamagne’s biography because of the way Joe Biden tried all his normal politician’s tricks of non-answer answers and little contrived mannerisms during the interview; all of which fell as flat as T-Pain without autotune.

Why the lack of curiosity about a wildly popular media figure like Charlamagne Tha God? Why the lack of preparation for what was bound to be a contentious interview full of hard questions?- which the Biden team would have been more prepared for, had they read “Black Privilege”.

Charlamagne Tha God once told Kanye West that West’s newest album “Yeezus was wack to me,”- to his face. And Kanye West isn’t the only one. Far from it.

Charlamagne Tha God certainly has no love for Donald Trump. But there is no way he was impressed with Joe Biden. And that is what should be making voting Democrats the maddest, and most determined to demand accountability from Joe Biden’s campaign staff.

Brad Parscale is Donald Trump’s campaign manager. If Donald Trump was booked on Charlamagne Tha God’s talk show, you can bet someone on that campaign staff would have read “Black Privilege” and given Trump the cliff-notes, at the very least.

Trump’s campaign is coming hard for the African-American vote; and they are getting a great deal farther with young Black men in America that any Democrat should be comfortable with.

This is the very audience of the Breakfast Club; why wasn’t Biden prepared to fight for this constituency by at least doing a little research on an interesting person like CTG?

There are even larger implications with Biden’s lackadaisical approach to key Democratic voting blocs like African-Americans; Biden isn’t trying that hard to win the Hispanic-American vote, either.

Before announcing his Latin-American voter outreach effort “Todos con Biden”, the Biden team couldn’t even be bothered to secure the website; a glaring error the Trump campaign was ready and willing to exploit.

With the Biden campaign in “full gear”, and the Democratic Party in the fight of its life, these errors should be striking fear into the hearts of voting Democrats everywhere.

They should be wondering, as Charlamagne Tha God must have been, if Joe Biden really wants to be President.

(contributing writer, Brooke Bell)

0 notes

Link

Yoga teacher Shane Roberts acted tough in order to fit in as a high school basketball player—until an injury led him to the mat to discover who he truly was.

As a kid, yoga teacher Shane Roberts, cofounder of Red Clay Yoga, always knew he'd play basketball. But hyper-masculine culture of athletics cost him an opportunity to find out who he really was—until an injury helped him change course.

As a kid, the first thing anyone ever wanted to know about me was if I was going to play basketball. I knew I was skilled, and Lord knows I dreamed about fame and fortune, but more than anything, I was tall. By the time I was 13, at 6-foot-6, my body looked like the ticket to material success. It was always assumed it would take me all the way to the NBA. I often overheard my mother talk about me as if she were waiting for her boat to come in. But now, 20 years later, I know that wasn’t the real reason I went to high school basketball tryouts. I went to find a tribe.

I was still traumatized from middle school. Adolescent boys proved how tough they were by using their fists. Watching Rambo and playing Mortal Kombat, we idolized heroes who died fighting. Fear of getting beat up consumed my thoughts because battles erupted often, seemingly from out of nowhere, and I believed violence was the only way to ward off threats at school. In other words, I fought a lot to establish a measure of authority.

But when I got to high school, I was back at the bottom of the social pecking order. Although kids seemed much calmer, displays of male dominance never went away. They manifested in the uneasy hierarchy of social groups. As a freshman, I felt I needed popular, attractive friends to have my back. Since sports culture is infused with valor, vigor, and classroom privileges, such as easy A’s, I was ultimately happy to join the basketball team.

See also How Kung Fu and Poetry Inspired Tyrone Beverly to Build a Better World—One Tough Conversation at a Time

But there was a price to pay. The supreme virtue on the team was obedience, and it went beyond following our coach’s direction in order to win. It policed our personalities, and any show of weakness was immediately checked with discipline. I’m a very sensitive person, and I’ve always wanted to be kind to people. But at some point, I just stopped being nice, because there were times I had revealed my compassionate side only to be punished. Once during a conditioning drill, while sprinting up and down the aisles of the aluminum bleachers on the football field, I spotted one of my teammates throwing up, so I stopped to help him. My coach benched me for going to his aid and started consistently bullying and berating me. I learned not to risk humiliation this way. I learned to fit in.

Basketball became my identity. I thought my sole purpose was to jump high and drain three-pointers to the delight of my classmates. And the more I bonded with my team, the more I needed their validation— proof that I wasn’t different. At the time, Michael Jordan and Gatorade had collaborated on one of the most famous ad campaigns of all time. Perhaps you remember it—the NBA giant was portrayed smiling, dunking, and not saying a word. I thought I had to Be Like Mike: apolitical, raceless, and happy to entertain.

See also How to Work with Yoga Students Who've Experienced Trauma

When I started visiting college campuses, coaches wanted to know whether I’d fit into their system, which was designed to profit off my body. They weren’t concerned with my mind, and definitely not my spirit, which had already been broken.

I ended up attending West Virginia University, where I’d earn my scholarship if I performed. Instead, I dislocated both of my knees on separate occasions during conditioning drills before my freshman season even began. I went back home to Los Angeles to live with my parents. I joined a junior college basketball team but never touched the court.

Benched again, I hated myself. I only identified as a basketball player—a failed one, at that. I started partying and taking drugs to escape the pain of feeling so isolated and lost. Deep down, I knew I wouldn’t thrive if I stayed in LA. Being black and doing drugs is different from being white and doing drugs; I was going to end up in jail or dead. So I got in my car and drove till I hit Atlanta, where I had a few friends from high school.

There, I became a personal trainer and went back to school to study English. I knew that sports culture had left my critical-thinking skills underdeveloped. This challenged me to reflect: Who was I going to be in the world?

See also Why DJ Townsel Left The Football Field for a Yoga Studio

Eventually, as a companion to mixed martial arts training, I started practicing yoga at home through the digital home-fitness regimen P90X. It felt so good to stretch, breathe, and get on my mat without fear—knowing that each practice was unique in what emotions it would raise—that I started attending yoga studio classes. Over five years of practicing yoga, I slowly took a journey inward. I was beginning to understand that I wasn’t just my body or my mind but a complex mind, body, and spirit. After I met my wife, Chelsea, she encouraged me to take my practice to the next level and enroll in teacher training at Kashi Atlanta, an urban yoga ashram.

When I started studying yoga philosophy, it opened me up to a region in my heart where love had been cut off by fear. Love opened up a door into my soul and showed me that I could be vulnerable. It was time to find, ground, grow, and share who I was—a man who descends from enslaved Americans and finds strength in these roots built of compassion, patience, and resilience.

After my basketball career, I had set out to figure out things on my own—an attitude many men lean into. American masculinity often reduces issues into “us versus them” or “me against the world”—which plays out on every level of society, whether it’s in high school classrooms, on basketball courts, or in corporate offices, politics, and beyond.

But yoga taught me that individual expression is stronger when it takes place in community with others. Every privilege, every product, and every service originates from the shared labor of other human beings. As we immerse ourselves in social and political realities, we necessarily nurture our inner selves. That’s why Chelsea and I co-founded a nonprofit organization called Red Clay Yoga, which organizes programs specifically for teen boys and girls. Through yoga, we wanted to teach the next generation of men and women that they can rise above stereotypes, shed their defenses, and be rooted in the glory of their own lives.

See also Helping Adolescent Boys Identify and Express Emotions Through Yoga

About the author

Shane Roberts is a yoga teacher and the co-founder of Red Clay Yoga. He studied yoga philosophy with Swami Jaya Devi Bhagavati at Kashi Atlanta. Learn more at redclayyoga.org.

0 notes

Link

Yoga teacher Shane Roberts acted tough in order to fit in as a high school basketball player—until an injury led him to the mat to discover who he truly was.

As a kid, yoga teacher Shane Roberts, cofounder of Red Clay Yoga, always knew he'd play basketball. But hyper-masculine culture of athletics cost him an opportunity to find out who he really was—until an injury helped him change course.

As a kid, the first thing anyone ever wanted to know about me was if I was going to play basketball. I knew I was skilled, and Lord knows I dreamed about fame and fortune, but more than anything, I was tall. By the time I was 13, at 6-foot-6, my body looked like the ticket to material success. It was always assumed it would take me all the way to the NBA. I often overheard my mother talk about me as if she were waiting for her boat to come in. But now, 20 years later, I know that wasn’t the real reason I went to high school basketball tryouts. I went to find a tribe.

I was still traumatized from middle school. Adolescent boys proved how tough they were by using their fists. Watching Rambo and playing Mortal Kombat, we idolized heroes who died fighting. Fear of getting beat up consumed my thoughts because battles erupted often, seemingly from out of nowhere, and I believed violence was the only way to ward off threats at school. In other words, I fought a lot to establish a measure of authority.

But when I got to high school, I was back at the bottom of the social pecking order. Although kids seemed much calmer, displays of male dominance never went away. They manifested in the uneasy hierarchy of social groups. As a freshman, I felt I needed popular, attractive friends to have my back. Since sports culture is infused with valor, vigor, and classroom privileges, such as easy A’s, I was ultimately happy to join the basketball team.

See also How Kung Fu and Poetry Inspired Tyrone Beverly to Build a Better World—One Tough Conversation at a Time