#which for me is linguistics and how languages work on a fundamental level and especially how they change over time

Note

Hi Hunxi!!🥰 I just finished the first The Poppy War book and wanted to ask your opinion about something. Tho I loved it — exhilarating action, drug-fueled avatar assumption, rekindled ancestral rage and all — one thing bothered me a lot. As a native Chinese speaker (tho studying in the states, yay) I instinctively recognized much of the historical analogues + literary references, which made it all the more offputting to see place and people names like Nikara, Khurdalain, Venka & Kesegi. (1/2)

These names seem insanely incongruous with the Chinese landscape depicted, especially when contrasted with the 蘇妲己, 姜子牙, 哪吒, Fang Runin and other more obviously/culturally mandarin ones. Some of them (ex. Nikara and Kesegi) even sound vaguely Japanese which is so ironic given the history the book draws on. I’m not trying to nitpick but they literally kept pulling me out of the reading experience. Just wondered whether you had any thoughts on that? Hope you have a great 2023💕 (2/2)

hi anon! this is a fascinating question, because R.F. Kuang's deliberate decision to make the naming conventions in The Poppy War trilogy inconsistent (i.e. rather than all Mandarin-derived, or all made up) actually has a lot of layers of thought and craft to it on a metafictional level that tbh I never thought of until this ask??

Kuang has made no secret of the fact that the trilogy places 20th century Chinese history in a Song Dynasty-esque setting; her characters have direct counterparts in Chinese history, literature, and culture (most notably, Fang Runin being a reception of Mao Zedong). that being said, despite the fairly obvious expies in the world of The Poppy War (Nikara for China, Hesperia for the UK, etc etc), the series still remains fundamentally secondary-world fantasy

the genre distinction is important here: R.F. Kuang deliberately chose to write secondary-world fantasy, not historical fantasy. maybe she didn't want to deal with research and historical accuracy (unlikely, given her methodology in Babel). maybe she wanted to dig her hands into Song Dynasty aesthetics (extremely valid of her). maybe she wanted to be inspired by history but not bound to it, as remixing historical events into secondary-world fantasy reads differently from rewriting historical events and changing the course of history. maybe situating the violence and the war crimes of the narrative in a secondary world was critical for her writing process (she has, I believe, mentioned in interviews how in many ways The Poppy War was born out of her negotiating generational trauma and academic research). I don't know for sure! she might've said so in an interview, maybe not. the point is, The Poppy War trilogy is secondary-world fantasy, and that matters on a fictional and metafictional level

if you'll let me, er, quote myself here for a bit:

Particularly in the Chinese tradition, there are three thousand years of thinkers, philosophers, essayists, poets, novelists, and satirists that contributed to the culture. There are schools of thought that metastasize and spill over into squabbling branches that snipe at each other for subsequent centuries; there are critics and scholars and libraries full of annotations buried in intertextual commentary. Faced with this unwieldy, ponderous inheritance, each author working with the Chinese tradition has to choose—how much of the tradition will they lay claim to, to reimagine and reinvent?

Language, history, and culture are so inextricably bound together in any culture or civilization that borrowing a single element from the Chinese tradition—worldbuilding, literary references, character names, genre tropes—necessarily involves translation both figurative and literal. On a linguistic level, how do you render terms that lack an English counterpart? On a cultural level, how do you do justice to the tiny details and customs that form the fabric of a familiar-unfamiliar world? For secondary-world silkpunk like Ken Liu’s epic trilogy The Dandelion Dynasty, Liu files off the serial numbers on ancient Chinese schools of thought, pitting Ruism, Daoism, and Legalism against each other under different names (cheekily, he renames the Confucius figure “Kon Fiji” and comments on his stuffy rigidity), while Chinese poems such as Liu Bang’s 《大风歌》 Da Feng Ge / Song of Great Wind cameo in his text as the lyrics of “mournful old Cocru folk tune[s].” Layered through translation and one degree removed from their original sources, Liu’s reception of the Chinese tradition takes the historical Chu-Han contention as a springboard into a secondary-world fantasy epic that veers sharply away from its historical analog by the second book.

In contrast, R.F. Kuang calls directly upon classical thinkers and characters by name in The Poppy War. Though likewise set in a fantastic secondary world, The Poppy War sees its protagonists studying recognizable Chinese classical thinkers like Zhuangzi and Sunzi in school, while legendary figures like Su Daji and Jiang Ziya from 《封神演义》 Feng Shen Yan Yi / Investiture of the Gods (a 16th century Ming Dynasty novel) walk the earth as unspeakably powerful shamans. In doing so, Kuang angles her trilogy towards an explosive confrontation between history and modernity, science and magic, the rigidity of a traditional past and the mutability of a devastating future.

so! while The Poppy War clearly and lovingly borrows aspects of its worldbuilding and construction from Chinese history, literature, and culture, I think R.F. Kuang’s decisions to break away from, for lack of better phrasing, making the world “too authentically Chinese” in the series is critical to the text’s role as a diasporic reception of Chinese history, literature, and culture. the things that are familiar are familiar. the things that are unfamiliar are deliberately unfamiliar. the story may resemble Chinese history, but it is not Chinese history

being able to make this distinction frees Kuang to do much more exploration in the series, both in terms of following the implications of intensely destructive, magical drug-powered warfare as well as experimenting with “what if” scenarios that are absent from or adjacent to actual 20th century Chinese history. I don’t think it’s an accident that the characters and names that are most distinctively Chinese (Su Daji, Jiang Ziya, and to an extent Nezha) are the ones that are most associated with history, tradition, an older world order. meanwhile, characters with “less Chinese” names (Chen Kitay and Fang Runin, since in no conceivable variation of Chinese I know would “Runin” ever be abbreviated as “Rin” yet here we are) are the young generation, the receivers and remixers and destroyers and recreators of the very traditional culture that Kuang borrows for her worldbuilding. Kitay, Rin, and Nezha in the narrative inherit the Chinese literary and historical tradition, and over the course of the trilogy, they rewrite it in blood as Nikara limps into the modern day

I also think it’s worthwhile to point out that Kuang’s Nikara — fantasy China if you will — is very conscious of its diversity and colorism. colorism deeply shapes Rin’s childhood and resentment towards the world around her; other characters like Altan Trengsin and Chaghan Suren are deliberately and distinctively not Han. in diversifying the naming of The Poppy War world, Kuang destabilizes the image of a monolithic, Han-only (fantasy) China in a powerfully receptive, diasporic, and postcolonial manner

all of which is to say: I agree with you! the naming definitely pulled me out of the narrative when I was reading it too, but I think the choice to do so was intentional on R.F. Kuang’s part, since examining the naming as a level of worldbuilding and craft yields a lot of metafictional nuance and value

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

is it bad or wrong to think that yoohyeon might have adhd? like idk it’s probably not great to headcanon things like that about a real person, idk... but... i kinda think she might and that just makes me happy and makes me feel good about myself so idk. im not actually gonna like ask her or believe that it’s true, i’m just gonna notice little things she does that i also do, and smile about those things.

#people should probably treat idols being possibly not straight the same way#thats a bigger issue than adhd too#but anyway#i get vibes a liiiiittle bit from yoojung and hayoung too#which is why theyre also ult biases lol#i dont get as strong vibes from them as i do from yoohyeon though#so much of her ''weird clumsy goofy forgetful but also super passionate super talented super knowledgeable'' personality#can be explained by her having adhd lol#i swear i catch little moments where she's spacing out or thinking two or three steps ahead and like#blurts out something that in her mind she arrived at after making several connections from thing to thing-#but to everyone else it came out of nowhere lol#she's a top tier rambler too#but her focuses on language dancing and singing and how talented she is at that stuff doesnt necessarily fit her spaced out persona...#...unless maybe she has adhd haha#same with how fromis 9 hayoung has a reputation for being good at literally everything she does... except talking#she stumbles over words and rambles and cant look in one direction for more than a second at a time#and yet is a main dancer main vocalist songwriter and weirdly good at games of skill and stuff like that lol#these are my people#im not saying im as talented as them... just that i also have that same kind of drive to know everythng there is to know about my thing#which for me is linguistics and how languages work on a fundamental level and especially how they change over time#but im a clumsy idiot who forgets things all the time and cant even read books because they arent stimulating enough#anyway

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear ‘White guy speaks perfect X and shocks Y!’ language YouTubers: STOP

A rant about every single fucking video by Xiaomanyc and similar YouTubers all titled things like CLUELESS WHITE GUY/GIRL LEARNS [INSERT NON-WHITE LANGUAGE HERE] AND SHOCKS [INSERT PLACE].

Disclaimer: I am white British, and I am also very often a moron. I'm trying to inform myself more, and would like to learn. So let me know if there is anything I should change, anything I’ve got wrong or any terminology I can change.

So this evening I opened YouTube to get some quality Hikaru no Go content, and saw yet another video recommended to me about Xiaomanyc called Clueless white guy orders in perfect Chinese, shocks patrons and staff!!!!

Really? Really. Ok, his Chinese certainly is good - but it isn't great. And it isn’t necessarily any better than people I've seen in the higher levels of a class at university who have spent some time in China. It's solidly intermediate. That's not an insult - that level of Chinese is hard to attain, and definitely worth celebrating!! Hell, I celebrate every new word I learn. But while it may be unusual, it doesn't forgive the clickbait type videos like 'White guy speaks perfect Chinese and wows [insert place]'.

These kind of clickbait titles rest on a number of assumptions. Before I say any more, I just want to make a note about terminology. Note that ’majority’ and ‘minority’ are not necessarily helpful labels, because they imply both a) a higher number of speakers in a certain place, and b) socially prestigious in some way. Of course a language like standard Mandarin is not a minority in China, but it might be in Germany. Talking about ‘minority’ languages that have a large speaker base outside of the country, like Chinese, is also not the same as talking about languages that have been systematically surpressed by a colonising, dominant language in their original communities, like indigenous languages. In many communities, especially in colonial and post-colonial situations, the language spoken by the majority is not one of prestige at all. Or some languages may be prestigious and expected in oral contexts, but not written - and so on. I use these terms here as best I can, but don't expect them to work 100% of the time.

So let’s unpack these assumptions a little.

1) That there is something inherently more ‘worthy’ in somebody who learns languages because they want to, rather than because they have to: and that, correspondingly, the people who want to are white (spoilers: much of Europe is multilingual, and white immigrants in majority white countries also exist, as well as discrimination against them e.g. Polish people in the UK), and that those who have to learn are not (spoilers: really? There are plenty of non-white monolinguals who are either happy being monolingual, don’t have access to learning, or don’t have to learn another language but are interested in it).

2) That everybody from a certain background automatically speaks all ‘those’ languages already, or that childhood multilingualism is a free pass - spoilers, it isn’t. Achieving high levels of fluency in multiple languages is hard, especially for languages with different writing systems, because no matter how perfect your upbringing, you’re still ultimately exposed to it maximum 50% of the time of monolingual speakers. Realistically, most people get far less exposure than 50% in any of their languages. Also, situations of multilingualism in many parts of the world are far more complex than home language / social language. You might speak one language with your father and his father, another with your mother and her family, another in the community, and another at school. Which one is your native language then? Monolinguals tell horror stories of ‘both cups half empty’ scenarios, but come on - how on earth do you expect a person to have the same size vocabulary in a language they hear only 25% of the time? Also, languages are spoken in different domains, to different people, in different social situations: just because someone hears Farsi at home doesn’t mean they can give a talk on the filing system at their local library. If something is outside of a multilingual person’s langauge domain, they might have to learn the vocabulary for it just like monolinguals. There’s no such thing as the ‘perfect bilingual’.

3) That learning another language imperfectly for leisure is laudable, but learning one imperfectly for work or survival is not. If you’re a speaker of a minority language, learning another language is necessary, ‘just what you have to do’, and if you don’t do it ‘properly’, that’s because of your lack of intelligence / laziness etc. It’s cool for the seconday school student to speak a bit of bad Japanese, but not so cool for the Indian guy who runs her favourite restaurant in Tokyo.

4) That majority speakers learning a minority language is somehow an act of surprising benevolence that should not go unrewarded. Languages are intrinsically tied up with identity - and access to them may not be a right, but a gift. Don’t assume that because you get a good reception with some speakers of one language that speakers of another will be grateful you’re learning their language, or that everyone will react the same. One of the reasons these videos are possible at all is that many Chinese speakers, in my experience, are incredibly welcoming and enthusiastic to non-natives learning Chinese. Some languages and linguistic groups have been so heavily persecuted that imagining such thing as an ‘apolitical’ language learner is a fundamental misunderstanding of the context in which the language is spoken, and essentially an impossibility when the act of speaking claims ownership to a group. Many people will not want you to learn their language, because it has been suppressed for hundreds of years - it’s theirs, not yours. We respect that. Whilst it’s great to learn a minority language, don’t do it for the YouTube likes - do it because you’re genuinely interested in the language, people, culture and history. We don’t deserve anything special for having done so.

5) That speaking a ‘foreign’ (i.e. culturally impressive / prestigious) language is much more impressive and socially acceptable than speaking a heritage language, home language or indigenous language. There are harmful language policies all around the world that simultaneously encourage the learning of ‘educational’ languages like Spanish, and at the same time forbid the use of the child’s mother tongue in class. And many non-majority languages are not foreign at all - they were spoken here, wherever you are, before English or Spanish or Russian or, yes, standard Mandarin Chinese. Policies that encourage standardised testing in English from a very young age like the ‘No Child Left Behind’ policy in the US disproportionately affect indigenous communities that are trying to revitalise their language against overwhelming callousness and cruelty - they expect bilingual children to attain the same level of English as a monolingual in first grade, which in an immersion school, they obviously won’t (and shouldn’t - they’ll get enough exposure to English as they grow up to make it not matter later down the line). But if the schools want funding, their kids have to pass those tests.

There’s more to cover - that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Some people’s response to these videos and why the titles are ‘wrong’ would be: does it matter that he's white? Shouldn't it just be 'second language learner speaks perfect Chinese'? This is the same sort of attitude as ‘I don’t see race’. I think it does matter that he is white - because communities of many languages around the world are so used to them having to learn a second language and colonial powers not bothering to learn theirs. You wouldn't get the same reactions in these videos if he were Asian American but grew up speaking / hearing no Chinese - because then it would be expected. You also wouldn't get the same reaction if he were an immigrant in a Chinese-speaking community from somewhere else in Asia.

It also implies that all white people = monolingual Americans with no interest in other cultures. While we all are complacent and complicit in failing to educate ourselves about the effects of historical and modern colonialism, titles like this perpetuate a very harmful stereotype - and I don't mean harmful as in 'poor Xiaomanyc', but harmful in that it suggests that this attitude is ok, it's part of 'being white', and therefore doesn't need to change. The reaction when someone doesn't engage with other cultures and isn't willing to learn about them shouldn't be 'lmao classic white guy'. That not only puts the subject in a group with other 'classic white guys', but puts a nice acceptable label on what really is privilege, a lack of curiosity, ignorance, and the opportunity (which most non-white people don't have) to have everything you learn in school and university be about you. If you're ignorant - ok. We are all about many things. But you don't have any excuse not to educate yourself. The 'foreigner experience' that white people get in places like China is not the same as immigrants in a predominantly monolingual, predominantly white English speaking area. As we can see in those kind of videos, white foreigners may be stared at, but ultimately enjoy huge privilege in many places around the world. It's not the same.

It also ignores, well, essentially the whole of Europe outside the UK and Ireland and many other places around the globe, where multilingualism is incredibly common - and where the racial dichotomy commonly heard in America isn't quite appropriate, or an oversimplification of many complex ethnic/national/racial/religious/linguistic etc factors that all influence discrimination and privilege. Actually many 'white guys' in Europe and places all around the world speak four or five languages to get by - some in highly privileged upbringings and school systems, yes, but others because they have grown up in a border town, or because they are immigrants and want to give their children a better start than they did, or because they want to work abroad and send home money. Many, like people all around the world, don't get a chance to learn to read and write their first language or dialect, which is considered 'lesser' than the majority language (French, Russian, English etc); many people, like Gaelic speakers in Scotland or speakers of Basque in France, have faced historical persecution and have been denied opportunities for speaking their mother tongue. My mother was beaten and my grandparents denied jobs for being Gaelic speakers. They are white, and they have benefited from being white in lots of other ways - but their linguistic experience is light-years from Xiaomanyc's.

It isn't 'white' to be surprised at a white person speaking another language - it's just ignorant. But the two ARE correlated, because who in modern America can afford to go through twenty one years and still be ignorant? People who have never had to learn a second language; people who have always had everybody adapt to THEIR linguistic needs, and not the other way around. People who have had all media, all books, centred around people who look like them and speak like them. And even in America, that's not just 'white' - that's specifically white (often middle class) English monolinguals.

I'm not saying everybody who doesn't speak a language should feel guilty for not learning one ( it's understandably not the priority for everyone - economic reasons, family, only so many hours in the day - there are plenty of reasons why language learning when you don’t have to is also not accessible to everyone). But be aware of the double standards we have as a society towards other socially/racially/religiously disadvantaged groups versus white college grads. You can't demonise one whilst lauding the other.

To all language YouTubers - do yourself a favour, and stop doing this. Your skills are impressive - that's enough.

tldr; clickbait titles like this rely on double standards and perpetuate harmful ideas - don't write them, and let your own language skills do the talking please.

#linguistics#lingblr#racism#sociolinguistics#languages#langblr#polyglot community#I don't really know what to tag this as#chinese#xiaomanyc#taking a break from my break to clearly post about two (2) things#hualian over on main and this here#meichenxi manages

128 notes

·

View notes

Note

How'd you learn so much about languages, if you don't mind me asking? I've always wanted to try my hand at building a language of my own, but never had even the faintest clue of where to start and how to do it correctly

i never mind questions!!

anyway, i don’t know a lot about languages, really. i know enough to leverage a very powerful conlang-building tool to get a result that feels Real Enough For Fantasy, which is very different from having true expertise in linguistics, which are very complicated and very confusing. i have wikipedia-level knowledge, but as a writer that’s really all you need, though of course genuine expertise or experience is always helpful.

some tips for expanding your general knowledge:

familiarize yourself with IPA notation, phonemes, and basic phonological concepts — vulgarlang actually has a decent basic rundown of this here and an IPA chart with audio here. this is important because the first thing you need to know about a language is what phonemes it uses.

pick a language. look it up on wikipedia. read the whole article, and look up any terms you don’t understand. pay attention not just to the discussions of syntax, morphology, spelling, phonology, but also to any information about the historical and cultural context of the language itself. culture is intrinsically linked to language, and this is something to keep in the back of your mind when you’re building a conlang. repeat this step frequently, with many different languages.

study the grammar of any languages you speak. this is especially important if you are a native english speaker who grew up in the united states in the last couple decades, because that means you probably weren’t taught english grammar in school beyond the absolute basics. a good way to strengthen your understanding of grammar in that case is actually to go looking for ESL resources, like this.

the goal here isn’t to become An Expert but rather to just get yourself a basic grasp of the fundamental building blocks that make up a language, so you can take them apart and put them back together in a naturalistic way.

now as for the actual process of conlanging, that goes basically like this:

#1: decide on phonemes and orthography, ie what the sounds are and how they are spelled. for example, here’s the consonants saporian uses (phonetic IPA on top, spelling on bottom)

k | χ | d | ð | ʝ | x | l | m | n | p | ɾ | s | ɕ | ʃ | t | θ | z | ʑ | ʒ

c | ch| d | dh| gh| h | l | m | n | p | r | s | ś | sh| t | th| z | ź | zh

and there’s the broad vowels (same deal):

a | ɑ | ʏ | ɪ | ɔ

a | ā | ē | ī | o

and the slender vowels:

æ| ɛ | i | eɪ̯

a | e | i | ae/ay

(*saporian has something called vowel harmony, which is where you have two classes of vowels that must match within a word. so in saporian every word is either broad, with broad vowels, or slender, and all prefixes/suffixes have a broad and slender version, there’s rules for compounding mismatched words etc. etc.)

(**eɪ̯ is a diphthong and it makes the sound “ay” as in “day.” you can find every other character here on an IPA chart if you’re interested in the pronunciation.)

at this stage you also want to decide what, if any, illegal combinations there are: are there sounds that are never allowed to go together in a word? for example, in saporian, you can’t have two fricatives in a row [fricatives being ch, dh, gh, h, s, ś, sh, th, z, ź, zh].

and finally, what kind of sound changes are there? for example in saporian, the phoneme “k” changes into a “χ” (c→ch) at the end of a word and when it occurs in front of a broad vowel other than ɔ (o) or the slender vowels ɛ and i. or as another example, in english the letter “c” turns from a k into an s if it’s before the letter e or i. [i think in general with a conlang, you should apply sound change rules with an eye towards making things easier to pronounce]

this all gives you the basic “sound” of a language. again using saporian as an example—notice how many of the consonants here are fricatives? that makes saporian a very sibilant, somewhat phlegmy language.

#2: decide on word structure. what sounds and combinations of sounds tend to occur at the beginning of words? in the middle? at the end? does your language have a consistent stress pattern and if so what is it (and if not, does stress encode lexical meaning—are there words that are otherwise identical but have different meanings based on where they’re stressed? eg in saporian—cathay (cathAY) is the god of the dead, but cáthay (CATHay) is the number five.)

#3: based on all this, start creating words. [or pop these settings into vulgarlang and let it generate words for you.] if you’re creating words by hand, think about things like shared etymological roots and how a given word can be morphed into other, related words, like this:

Turn a Verb into an Adjective resulting from the Verb

to torture → tortured

Remove the infinitive ending.

Shift the vowels (broad ↔ slender).

Turn a Verb into an Adjective causing the Verb

to torture → torturous

Remove the infinitive ending.

Shift the vowels.

Append the appropriate suffix (-ɪʃ or -iʃ).

Turn a Verb into a Noun that is the act of the Verb

to torture → torture

Remove the infinitive ending.

Turn a Verb into a Noun that is the product of the Verb

to torture → trauma

Remove the infinitive ending.

Append the appropriate suffix (-ɑn or -æn).

Turn a Verb into a Noun that is doing the Verb

to torture → torturer

Remove the infinitive ending.

Append the appropriate suffix (-aɾ or -eɪ̯ɾ).

this part is important because it produces a language that feels cohesive and like something that could have developed naturally over time. words that are related to each other should sound similar to each other. if you’re using vulgarlang you can do this part automatically by setting up affixes, which are pretty impressively robust in terms of what you can do with a bit of regex and basic understanding of how if/then/else statements:

VERB.TO.PRODUCT.NOUN =

IF (ɪʝ)# THEN (ɪʝ) > ɑn

IF (iɾ)# THEN (iɾ) > æn

IF (æm)# THEN (æm) > æn

IF (eɪ̯)# THEN eɪ̯ >> æn

IF (i|ɛ|æ)# THEN V >> æn

IF (i|ɛ|æ) THEN -æn

IF (a|ɔ|ɪ|ʏ|ɑ)# THEN V >> ɑn

IF (a|ɔ|ɪ|ʏ|ɑ) THEN -ɑn

"to torture → torture

Remove the infinitive ending.

Append the appropriate suffix (-ɑn or -æn).

#4: at this stage you also want to start thinking about grammar. what is the basic word order—subject-verb-object, like in english? VSO? OSV? SOV?—and what about other parts of speech? do adjectives come before or after the nouns they modify? what about adverbs?

how does your language do adpositions—are they prepositions (like in english) or postpositions, or is that meaning conveyed in other ways (eg through verb conjugation, noun case, or affixes?)

how do you create questions? how do you negate a phrase? how does counting work? how do you encode temporal or spatial meaning?

how does noun declension work in your language, and how many different noun cases are there? what about verb conjugation—do you have just one conjugation for your basic tenses, or does additional information get encoded in a conjugated verb (ie english i ran, you ran, he ran, we ran, you all ran, they ran, vs german ich lief, du liefst, er lief, wir liefen, ihr lieft, sie/Sie liefen). how are plurals created?

does your language have an informal and formal you? and what other pronouns are there? (for example, saporian has four gendered third person pronouns: za (she), śa (he), źa (neuter), and ān (it)—but only one “you,” sā (singular) and dhām (plural), because formality/respect is encoded through different means.)

#5: finally, what are some exceptions to the rules? all real languages have them. are there irregular verbs, and if so how are they conjugated? are there situations in which morphological or phonological rules don’t apply? i would keep this part pretty simple, but do try to work in a small handful of exceptions because it does make a conlang feel a lot more real.

for example:

in saporian, most adverbs begin with the prefix ɕʏ- (śē-) or ɕɛ- (śe-), but a handful [those beginning with any vowel or x (h), unless they are derived from an adjective] do not. so āram (now) and hagh (maybe/perhaps) are adverbs that lack the prefix.

and with most affixes, the prefix or suffix replaces the vowel at the beginning or end of the word being affixed, but the two honorific prefixes [ʒa- (zha-) or ʒæ- (zha-), kɾʏ- (crē-) or kɾɛ- (cre-)] instead lose their vowels if they’re being affixed to a word that begins with a vowel.

and i’ve been kicking around ideas for a handful of irregular verbs that don’t end with the three standard infinitive endings [-ɪʝ (-īgh), iɾ (-ir), or -æm (-am)] and are conjugated differently but i haven’t settled on precisely how yet so For Now those irregular verbs still take the standard conjugation suffixes.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Untamed: unsorted

Well... I am nothing, if not eccentric, after all. Why not publish a huge post all of a sudden? :)

The Untamed (СQL) is an abyss, and I am still falling, grasping at some scattered thoughts... that tend to arrange themselves in equally chaotic blocks of thoughts, which, in turn, multiply questions successfully.

Spoilers ahead, I guess...

I.

The timeline of СQL is more than a little blurry, and when I try to calculate, how old Wei Ying was, when he died, I come up with the sorrowful conclusion he couldn’t be more that 21, probably younger. Which, in turn, means that the post-time-skip Sizhui is, actually, of the same age or even older than Wei Ying and Lan Wangji were, when they did a lot of things I honestly can’t imagine the new generation pulling off, even physically/magically, let alone psychologically (although I wouldn’t go as far as to call young LWJ and WWX mature - they clearly were not, and that was a huge part of the tragedy foundation, in my opinion). The young disciples are referred to as ‘children’, and they truly are. Compared to 16-17 year old LWJ and WWX, they are very, very young, inexperienced and not especially capable – while still being quite skilled and smart. And it’s both fabulous and painful to watch. Fabulous because it’s a very vivid and authentic demonstration of how exceptionally gifted LWJ and WWX are (and were); and painful because, unfortunately, not all of their greatness comes just from inborn talents.

II.

I am easily charmed by languages, but СQL, being the third Chinese dorama I have ever watched, is still the first one to so profusely tempt me to learn Chinese – in order to translate the songs and to understand the subtleties of the dialogues.

III.

I can’t get rid of the impression that the concept of rules/order breaking and punishment/atonement is fundamental for СQL (and its world). As far as I am aware, the Chinese culture does tend to be quite severe in this regard, but right now I am considering the symbolic layer of the process rather than the harm/good/efficiency of any particular method. And I wonder, whether I am imagining things or Wangji’s history of ‘transgressions’ and punishments within his sect is really openly symbolic and not merely coincidental.

My interpretation certainly lacks some special cultural insight because I can’t help being of European origin, so I read all the codes as a European would, first, and only then make an attempt to switch lenses and decipher the message, taking into account my scarce knowledge of the Chinese (and Asian) culture.

And yet...

The first time (drinking) Wangji is not only completely innocent, but also a ‘victim’ of Wei Ying’s careless (and questionable) mischief. They share the punishment (and we encounter the number 300, by the way), but Wangji is obviously (and rather fiercely) on his own here, and evidently by choice, despite Wei Ying’s sincere efforts first to exclude and then to include him. Wangji, just as obviously, truly believes he deserves the punishment – not for drinking as such, I think, but for lowering his guard and being not attentive enough: internally, he substitutes one transgression with another, and the equation works for him (actually, it might be unfair, but quite fortunate for their future relationship that Wangji blames himself or, at least, blames himself more than Wei Ying). To put it in a nutshell, for Wangji, the system and order are intact and non-contradictory: he is understandably upset, even angry, but hardly shaken, and simply intends to do better than that in the future, so to say. It’s hard to speculate, if this is Wangji’s most unpleasant experience so far or not, but in any case, the psychological pressure is minimal and reproach is rather mild (and I am really surprised, Lan Xichen didn’t find all that story highly suspicious… or was it his indirect method of showing WWX that he hadn’t been told on?..)

The copying of the rules happens after a considerable amount of… experience, if not time. And the transgression is not specified, but hinted at very heavily. I also wonder, if Lan Qiren realized an additional message he conveyed through his choice as well as through his general treatment of his nephew during that meeting: a strict reminder that, a war hero or not, LWJ is still too young to have an opinion. Wangji accepts the book of rules reverently, accepts the punishment… the word, that springs to mind is ‘habitually’: he doesn’t disregard it, per se, he doesn’t devalue the fact his uncle is not happy with him, he still wants to do better, but… there are things of greater importance to him now, and LWJ is so focused on them that he makes the request about the restricted books at the least suitable moment, really. (And I believe this dismissal does cut him rather deep.) The system still works, but the seed of the conflict is already planted.

The third episode seems pivotal in itself: we actually don’t know, what the punishment for letting WWX and the Wens go was, except for having to kneel, while being lectured, but this time this is a result of a conscious choice to do something that definitely wouldn’t be approved. And I can’t remember a single second of the screen-time, when Wangji would look repentant: conflicted, upset, slapped (when Lan Qiren mentions his mother), stressed (his uncle uses some pretty cruel techniques that border on manipulation, to my mind), but not sorry at all – not for letting the fugitives go, at least. And comparing the shades of Wangji’s silence here and on the previous occasion, this one seems somehow more determined. And closed-off. And there is no intention to do better, in regard to this transgression: the alternative he is being pushed to is unacceptable.

Kneeling again, for the whole day, in the cold, lifting a… what is it, as a matter of fact? It does look like a slightly smaller version of ‘the discipline whip’ we’ll see later, and if it is really so, then it’s beyond prophetic symbolic – it looks more like a promise on Lan Qiren’s part. :/ Anyway, my impression is that, for the first time in the series, LWJ is actively absent from the scene of his own punishment: he doesn’t reflect on it (I think he expected something like that), he also doesn’t mentally substitute one transgression with another to restore the balance (his inability to help Wei Ying is not something to atone for by kneeling). He simply endures. And thinks. And feels. Just not what he is expected and obliged to be thinking and feeling at the moment. And through all of this, Wangji is utterly, hopelessly and stoically alone and unaccepted. His concerns have been dismissed and care rejected by Wei Ying. His actions and decisions have been castigated by a significant authority figure (whom he loves and respects). If I am not mistaken, in the special edition Wangji’s loss-and-loneliness are somewhat artificially heightened through the pseudo-contrast because his moments are mixed with the moments of Wei Ying’s drinking with his new family, who values and appreciates him. (In reality their situations are just the same: they are both in anguish and feel helpless to change things they wish to change.) And, a cherry on top: we don’t know, what has been said initially, and by whom, however, we see that Wangji is released not by his uncle, but by some adept (or disciple). It might be a normal procedure, but it completes the picture of being unequivocally separated from any supportive figure and hints at a lack of closure, in a way, as there was no forgivenes-and-reconnection after the punishment.

I am struggling to verbalize, why exactly, but to me, this scene is, in a sense, more bitter than the next one, despite the circumstances.

During the next punishment Wangji is as actively present as he was absent during the previous one. And if then he was frozen in sadness, now he is all fire (fueled by grief, and guilt, and fury, and despair, yes, but fire, nonetheless). And the system and order get burned down: what Wangji re-builds during his seclusion is his very own set of rules. They do coincide with the Gusu Lan set, but not fully. And this is a point of no return because, filtered through Wangji’s own system of values, now they are more than just the elders’ lessons learned and tested – they are the only valid reference point for recognizing transgressions and ‘living with no regrets’.

(On another level, I am more than a little puzzled by several details here:

1) linguistics: do they really call this thing a discipline ‘whip’ in Chinese?

2) cultural message: as literally nothing could get in the way of filming a beating with an actual whip, the type of instrument has to make some sense, doesn’t it? (For now, I can’t think of any reason to choose this tool, though. Except the number 300 as 300 lashes are hardly survivable, even with a golden core.)

3) application: I can understand, why Wangji has his shirt on (although this is a more dangerous and torturous option: such a thin layer is no protection at all, but it will be hell to clean the wounds afterwards), but why is his hair down his back like that?..

4) consequences: the scarring looks rather odd, considering. (And again: it was definitely not a problem to paint whatever they had to, so – why?)

The only (and vague) explanation I can come up with is that the type and form of the tool is not important at all: it’s the intent and sentence that count, so the wounds and pain would be the same, even if the instrument looked like a rod or a cane. (Still doesn’t explain the hair, though.) And as for the scars, perhaps, not all of them have to stay forever, especially if the cultivator is very strong.

Well, no: unsatisfactory...)

IV.

I wonder... My first impression after watching the scene, where Lan Wangji cuts off Jin Guangyao’s arm, was that he was actually saving him from Baxia, separating Guangyao from the mark on his hand. And the only reason, why the spirit of the sword attacks Jin Ling next, are the drops of the bad/damned blood on the boy’s shoulder. But after the special edition I am not so sure.

V.

Lacunae and plotholes (or what I subjectively perceive as such) are extremely challenging and thought-provoking in this series. Right now, I wonder about the Wens: Wen Qing clearly stated she had asked one of the clansmen to look after WWX, so not all of them were going to surrender. Could it be that they were attacked at the Burial Mounds, when seeing the siblings off, and taken away by force?

...Enough. For now.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hobbies and Criticism

I sat on this when it happened, and again yesterday but it’s something I do want to speak about because I’ve seen it happen often enough that it merits discussion. There are a few separate elements here and I will try to be cohesive in stringing them together.

It’s long so it’s going under a cut... Sorrynotsorry XD

On Unsolicited Criticism

Fan art and fan fiction are, fundamentally, hobbies. I am not addressing commissions here. I am talking about artists who create their art out of their own desire to make something based on whatever inspired them. Some people love sharing that art with the world. Some people don’t. They are not doing so because they are being paid for their work but because they want to create something out of personal love for it. Those who share it with the world are not obligated to. It is a gift. A gift, by virtue of the internet, that you are not required to accept or like - certainly I don’t like every fanfiction written about my fave pair. In fact I don’t like most of them. It is still a gift, however and the mannerly thing to do when you come across a gift that isn’t to your liking, is to simply pass on it. It’s very easy to do on the internet. Hit the back button. Scroll past it. Block the artist if you find their art repulsive. The fundamental rule of mature fandom behavior on the internet. Curate your own experience.

Further to this, when a person offers up a gift, it isn’t your place to critique them, unsolicited. You aren’t doing anyone a good turn by pointing out where they are fucking up. You may think you are somehow contributing to fandom by “helping” a struggling artist to improve their works by providing unsolicited criticism but you aren’t. In fact, from what I have seen and heard from artists, it’s usually the opposite. Many fan artists aren’t professionals. Some might be, more so I’ve noticed in the graphic art sphere than in the writer sphere, but most aren’t. Many fan artists are beginners. Many fan artists are students of their art. Many are learning as they are doing. Most importantly, many are doing this for fun, as a hobby, and aren’t aiming to become professionals.

Many fan artists who are either learning as they go or just doing this for fun when they have time are more than aware that they aren’t professionals. They know that they aren’t the best. They usually have an idea of where their weaknesses are. Sharing their art often takes a great deal of courage for them because they know they are offering something up that isn’t perfect but they love it enough to share it in the hopes that other people will love it too. Coming into their space after they’ve shared a work of love and pointing out all the things that are wrong with it is more likely to cause a new writer or artist to recoil and give up than it is to cause them to double down and try to get better. This isn’t theoretical for me. I’ve heard former artists and writers say that they gave up because all they ever heard was how bad they were. Again, not people who wanted to be professionals. People who just wanted to create things for fun. Who had that fun stripped away from them by strangers who thought it acceptable to enter their space and shit on their work.

When a child is learning to do something we do not take the picture they drew of their stick people families and smiley suns and tell them “Honey, the sun doesn’t have a face. People aren’t sticks. That’s not how to draw hair.”

We do not do that because it is not productive. It is hurtful. We know this and yet fans seem to think it’s “helpful” and acceptable to do this to other adults. Assuming the artists are adults, which is a fallacy. Many are teens as well. Under the assumption that adults aren’t going to burst into tears because you pointed out their failings, you shovel your criticisms over them without stopping to consider that maybe, just maybe, they will because they know they aren’t that perfect. They know they can’t draw hands. They know that their grammar isn’t the best. But they’re trying and they’re creating and they just want to share their ideas. They want to share their love with people who love the thing too.

They didn’t ask for criticism. They provided a gift and had someone take a shit on it. This is not kind and helpful and certainly I would not be inclined to continue to provide gifts to anyone who treated me in such a way. Unsolicited criticism does not improve artists, it drives them away.

On Solicited Criticism and Being Constructive

I’m going to talk from a writer’s perspective here because I am a writer and I don’t entirely understand artists methods because I never took any sort of art classes. I still think the overall theme of this applies to artists as well, especially when discussing the purpose of criticism and the method of delivery.

Many artists and writers do want to improve and would appreciate genuine criticism of their works. This is a double-edged sword, of course because in my experience we aren’t taught how to take criticism as a flaw in our skill without feeling like it is a flaw in ourselves. We associate our worth very strongly with our ability to do things and as such, addressing our flaws can become a very emotional battle.

When an artist solicits for constructive criticism, they aren’t asking you to point out everything that is wrong with their work. That isn’t what criticism in this situation is meant to be. They are asking for explanations on why things don’t work. They are asking for guidance on how to improve. If you cannot provide that kind of feedback, don’t give the criticism in the first place.

As a writer I do wonder if I am perhaps more attuned to the way words work than the average reader. As such, I try to give people the benefit of the doubt when it comes to word choices and I want to talk about that a bit as it relates to online conversations around criticism. We give tone to certain words. A single word’s meaning might not be negative but how we use it in day-to-day conversation can very much instill a level of emotional subtext to that word that translates into how people write and read that word.

When giving feedback to a person, it’s easy to make a checklist of all the things they got wrong. In some cases, this can be acceptable, such as with basic grammar mistakes. If you’re asking me to proofread your work for grammar, I’m just going to red pen it and note the corrections in the margins because this is simply the mechanics of writing and I know plenty of native English speakers who don’t understand the full complexities of the language. I speak about English (which is the literal worst language in existence) because it’s my native tongue but this can apply to any language.

However, when you begin to delve into deeper things like characterization, themes, plot and so on, this becomes significantly less straightforward. When you add a writer’s voice (or an artist’s vision) into the mix, it gets very messy.

The one thing that should never change when giving criticism is tone. One should not be cruel or harsh in delivering criticism. One should be kind and understanding. The artist is opening themselves up and asking for help which is difficult enough on its own. The response should be patient and helpful. Take care to choose your words to support and uplift the artist, not to tear them down. For every criticism you offer, you should also try to offer a solution or a guideline for the artist. If the criticism is about how the pacing of the story is too slow, making the story drag, then explain what makes it feel slow and why that is a negative thing. Offer suggestions on what might improve the pacing.

Ex. I noticed that in this chapter it felt like nothing was really happening to further the plot and that left me feeling bored. Perhaps you could improve the pacing of this chapter by including some reference to how this affects the greater plot? Or add something to the end of the chapter to bring us back around to where the plot is headed?

As many “beta readers” are also not professionals, it’s understandable that maybe you don’t know how to offer constructive criticism. Maybe you just have a feeling that something doesn’t look or read write but you don’t know linguistics well enough to identify the why behind it. That’s ok too, as long as you convey that honestly and kindly.

Ex. When I was reading this part of the chapter it didn’t feel like it flowed very well but I’m not sure why. If you have another editor, maybe ask them for their opinion on it?

Because sometimes when we are reading something our own internal biases will create problems where there are none, or catch problems without knowing why they are problems. This is especially useful if you’re being asked for your opinion on whether or not someone is handling a sensitive topic well (race, sex, sexual orientation etc.).

When it comes to the writer’s voice, this is where criticism is very difficult. If an author loves their purple prose (overly flowery descriptions of everything) and it bothers you as a reader, you’re probably not their audience and criticizing them for it isn’t actually helpful. It’s fine to ask them if they mean to write in that manner, or ask if it serves a specific purpose to them but if their response is that it is the way they enjoy writing, then it is not a topic that is open for criticism.

Conclusion

Artists - Nay, People grow by learning from their mistakes but they need support in understanding what those mistakes are and how to improve them. They do not grow by constantly being told to “get better”. Respect those who are gifting you with their art. Give them the respect they deserve for being kind and brave enough to post their creations. If they don’t want criticism, respect that boundary. If they do want criticism, give it in a kind and helpful way.

Lastly, and especially because this is what bothered me the most about the incident that caused me to write this:

Artists grow by doing. They cannot get better without doing and making mistakes and doing more and making more mistakes. This is the literal process of learning a skill.

Do not ever tell an artist to stop creating because they aren’t good enough.

It doesn’t make you ‘helpful’. It makes you a giant fucking douchebag.

#writer things#or artist things#fandom observations#constructive criticism#what it is and what it isn't#just really needed to put this out there#cause I really hate watching artists and writers#getting shit on in the name of constructive criticism#and the entitlement that some fans show#thinking they have the right to determine#what is good and what is bad in fandom art#ps I hate the term beta reader#like there's a word for this already#so why'd you go and steal an tech term?#what's wrong with editor?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Burrowing Dramaturgy: Andy Edwards @ Tron

In Burrows

A new performance in BSL and spoken word, created by Andy Edwards, presenting at Tron Theatre on March 23rd and 24th.

credits: Julia Bauer

The performance frames the act of description through a series of choreographies, investigating the relationship between spoken language, sign and meaning, and exploring perspective and how we engage with the world around us.

In Burrows will be accompanied by a number of guest performances. Musician Blair Coron will perform a composition developed especially for the event. Petre Dobre and Adriana Navarro will present the short performance Words, who needs them?

What was the inspiration for this performance?

In Burrows began as a short piece, first performed at Only Skin’s SCRATCH back in October 2016. In the work I would describe an image to the audience, an image that was placed onstage so that they couldn’t see it, in 1500 words. What inspired this performance was a desire to make the easiest piece of work I could possibly make, that offered the maximum amount to the audience it could while carrying with it as little as possible. So it made sense to work with an audiences imaginations. Then I also wanted a piece of work I could just turn up and do, make up on the spot, so it made sense to play with improvisation.

The method of improvisation I employ was developed as part of the ground, the highest point a duet of text and dance I performed with Paul Hughes at a couple of festivals during 2015. Initially it very strongly drew from (or, less charitably, stole) Tim Etchell’s solo practice but since then it has departed considerably, and I’ve improvised poetry across a wider range of contexts, developing my own particular set of enquiries. Those enquires are primarily linguistic – I’m interested in how language works.

When offered to present In Burrows at Tron I was posed with the problem of how to take a very solid short work and evolve it into something three times the length, without just dragging it out. I’d been curious about working with a British Sign Language interpreter for a while, largely out of a desire to make my work more accessible to an audience I’d previously not made any work for and also because I was curious about the language itself. Placing Amy Cheskin into the work has been brilliant. A simple act that has produced lots of tensions, questions, that have driven the work forward.

Thinking about translation, interpretation and the fuzzy areas in

between has given the project a new lease of life – and certainly inspired me to push forward with it. Rehearsals are thundering along and we’re both pretty buzzed by how fascinating language is, and how it intersects – both producing and being produced by – what you’re thinking, what you’re feeling, how you’re trying to position yourself to others and the world around you.

Is performance still a good space for the public discussion of ideas?

It is a good launch-pad for the public discussion of ideas – and then, that discussion, happens after the performance has taken place. Any good discourse is advanced by someone making a claim about something, and then other people assessing that claim. Me saying that I think this gives you something to react off of.

The way I go about making performance is to think that each performance I make is an act of making a claim about something, taking up a position, and that by taking up a position I’m inviting others to observe, discuss and criticise that position. That’s the basic task that I’m up to – trying to hold someone’s attention long enough for them to know what it is I’m claiming but with a relaxed enough grip so that they can react to it. And then things that I’m doing are hugely informed by the ideas I’ve previously discussed that have led me up to this point.

I think that’s why art in general is a good space for the public discussion of ideas – because it is often people making statements about the world that have a smaller impact on that world. That isn’t to say that impact is negligible. Not at all. Or that it doesn’t have a significant impact on the world. It most definitely does – and that isn’t always a positive one. But there’s something both flimsy and robust about art that means the stakes are low enough so that we can discuss it but that also our discussion of it won’t kill the thing stone dead. So yes, in that sense, it’s has the potential to be a great space to discuss ideas.

That’s all potential though, because if only a small segment of people can access the space in which the discussion takes place then it won’t be much of a discussion at all. So, it depends on what the performance is, where it is being held and who is allowed in.

How did you become interested in making performance?

I’m not particularly sure. I came about it the long way around and avoided it for a while, in part due to a certain type of pressure applied to me when I was younger, and in part due to being scared that I’d be totally rubbish at it. As a teenager I found acting, with characters and lines and arcs, such a release for a build up of emotions I’d not learnt how to deal with. I did a GCSE, then A-Level, in drama. Then fell in with the theatre crowd at University – after a brief attempt to avoid doing it – then did a masters – after another brief attempt to avoid doing it – and since then I continually flip flop between wanting to knock Shakespeare off his perch and “getting a job in a bank”, forgetting of course that getting a job in a bank is probably quite difficult / the banks might not be particularly in desperate need of my services.

Is there any particular approach to the making of the show?

Me and Amy work in a manner where the creative responsibility is a little imbalanced. Given Amy is a translator, that’s a really necessary thing for her to do her job, but it leads to the interesting tension where if the work is crap it isn’t her fault, it’s mine. So it is interesting how labour divides up as a result of that. The pattern is that we meet once a week and for three hours throw things about, try something and note what happens. Then I’ll go away and write something, some notes, a script, or whatever – and then we’ll come back together again and throw what’s left together again. So we move forward like that – and it’s going super well I think.

Thinking about our general approach, we spend a lot of time asking what the audience will be getting from the work, and how audiences with different abilities will receive the work differently. The work will be accessible to a range of audiences including those who are D/deaf, hard of hearing, partially sighted or blind, with integrated BSL interpretation and audio description. This desire to make a piece of work that offers a rich theatrical experience to these audiences informs a lot of decisions we make. Rather than to offer one blanket experience of the work, we’re curious as to what we can offer each of these specific audiences in turn. The work, as a whole, is concerned with a very specific relationship to each and every one of its audience members. It’ll be a bit different for everyone, given that a lot of it will take place inside their heads.

Does the show fit with your usual productions?

While I’ve performed my work before, most recently as part of Andy Arnold’s group show NOWHERE during Take Me Somewhere 2017, I am more commonly found as a playwright. Typically I write text for others, in a ‘New Writing’ context, whereas for In Burrows I’m speaking text that has never been written down.

There’s a thread that runs through all this work though, which is about being in control of language. That sentence sounds a bit gross, reading it back. With In Burrows I’m making that process more explicit to the audience then if I were to write a play, which I’d typically do out of sight.

So while it will look very different to a lot of my other work, I think the underlying mechanics are fundamentally the same.

What do you hope that the audience will experience?

The dramaturg for In Burrows, Paul Hughes, wrote this note to me after a development weekend:

“I’m looking at a photograph by Andy Goldsworthy currently on display in the Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art: a line of upturned leaves placed on dense patch of bracken, the stark white undersides standing out from the vivid green of the forest. It doesn’t impress the viewer in how it has acquired huge or rare or precious materials, or on how many people the artist holds in their command, or even in how it has hoodwinked and mocked the institution that houses it. No sustained physical commitment was required to produce this; in fact, the action so simple that we can imagine the exact steps with which it was undertaken. The gesture points towards the artist themself as much as any material circumstance or image.

Is this an alchemical transformation? Do we perceive the artist as a magician, effortlessly transforming reality around them? This can only be determined on a case-by-case basis, depending on the individual viewer’s tastes, affiliations and readiness to go along with the trick. What’s more clear is the particular sense of romance, of the poetic, within the artist: of the ways in which they read charm and delight in the world around them. Perhaps in this work - and obviously I’m talking about In Burrows too - the artist is inviting us to briefly see the world through their eyes - not as a way to seduce us, but to share with us a way in which we might allow ourselves to be seduced. We stand before an intimate proposition; the individual’s un/abashed offer of their very personal relationship to beauty”

So perhaps that sums it up, perhaps it doesn’t. I’m wanting the audience to have the experience of observing something very personal to themselves, namely their relationship to language, memory, imagination and image. It’ll be small, quiet, and hopefully full of stuff for them to latch on to and play with.

Both In Burrows and Words, Who Needs Them? have been created for the enjoyment of hearing, hard-of-hearing and D/deaf audiences. In Burrows also features integrated audio description for blind or partially sighted audiences.

from the vileblog http://ift.tt/2ohvYuv

1 note

·

View note

Text

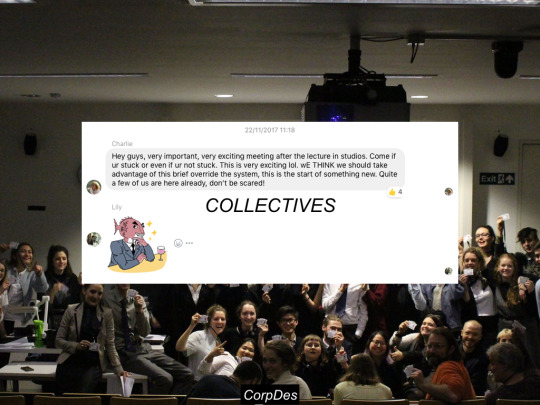

On Assembly

On Friday I was joined by Michael Hardt on Novara to talk about his new book - co-authored with Toni Negri - Assembly. It’s a follow-up to the Empire trilogy and a serious and ambitious intervention. Empire is one of those books which I think suffered from its success; its theses were often broadened out and vulgarised. That’s the fate of any successful book (how Benedict Anderson must have come to hate the phrase ‘imagined communities’) but I think it was especially bad here. I imagine the same will happen here, but the book is very much worth reading, and even though I have some substantial disagreements with parts of it, I was struck by how much I had missed its ambition and brio – it is an attempt to think the current political moment in its totality, from the practical activity of the ‘movement’ (especially, for H&N, the arc of protests and struggles extending from Tunisia to 15M to Occupy, though not exclusively) to the current form of capitalism and emergent forms of cooperation and solidarity. Their ambition is to operate beyond the political per se and enter the ‘hidden abode’ of economic and social need which is its matrix. It’s a good ambition and the book repays careful reading.

It is a less politically theoretical book than the previous work: there is no lengthy digression on Spinozist ‘multitude’, or careful genealogy of the concept of sovereignty. That’s partly because the book rests on the earlier theoretical work, but also because of the different historical moments in which they have been written: Empire, especially, was written as a way of seeking a theoretical articulation of a global political ‘moment’ in its crescendo; the situation now is decidedly more mixed. The theoretical slant of the book is a tussle with Rousseau, especially, although it’s only carried out obliquely, save in chapter 3; I’d have liked to see it pursued a bit more.

But it struck me while reading how different the fruits of ‘Western Marxism’ – which they defend, correctly I think, in a late section of the book – are between intellectual traditions. Their two preferred figures are a little strange –Lukács and the later Merleau-Ponty – but it allowed me to understand their project as part of a line of work which blends Marxism primarily with philosophy, which allows for their systemic ambition, but only briefly dallies with history. This is quite different from another Western Marxism, one strain of which is Anglophone, which blends Marxism with history: think EP Thompson, Hobsbawm, Perry Anderson, or even Peter Linebaugh (the line is certainly heterogeneous). It might have been fruitful to grapple with Anderson’s insight that the secret signature of all Western Marxism is failure, and operate from there. That kind of thinking might have been especially useful in suggesting that H&N proceed from the specific problems of particular moments of struggle (what did people think they were doing? what did they want? what future did they see? what were they struggling against?) rather than allowing them to appear just as examples of broader, overarching arguments. But then that would have been a different book.

There are two specific things I find awkward in the book:

The first is the idea of ‘nonsovereignty’, which I don’t think is ever fully articulated. I suspect H&N have painted themselves into a philosophical corner here. In brief, nonsovereignty is a conceptual polemic against all political conceptions framed around sovereignty, which they see as inevitably (re)producing relations of domination – against this they propose a somewhat murky idea of ‘nonsovereign’ institutions which emerge from the matrix of pre-existing co-operation and sociality coming into self-consciousness. But here things get problematic. Not only does this skirt the historical question – why do so many contemporary movements, right and left, articulate themselves in terms of sovereignty? – but it seems to smuggle in sovereignty under the rubric of nonsovereignty. In other words, nonsovereign institutions are sovereign institutions (i.e., fully autonomous ones which set their own rules, determine their own nature and limits etc) but with sovereignty used for other, non-dominating ends. I think that’s good! I just don’t see the need for the term.

But I understand where it comes from: not only a generalised suspicion of the ‘political’ per se – hence the polemic against the ‘autonomy of the political’ which we argue about a little in the show – but a long commitment to the idea that capitalism produces new, resistant subjects, with resources which surpass capital’s attempts to exploit them. That is what Negri was doing with the baroque figure of the ‘operaio sociale’ decades ago, and it’s the same here. But the theoretical consequences of this orientation cuts off any consideration that political concepts are themselves sites of struggle for meaning – and therefore politics is only conceived of as their total negation.

The second matter I struggle with is related – it is about a ‘resistant subject’ and also about political concepts. In a way it is a minor thing, but also an indicative one. H&N write:

“Migrants, for example, who play such a fundamental role in shaping the contemporary world, who cross borders and nations, deserts and seas, who are forced to live precariously in ghettos and take the most humiliating work in order to survive, who risk the violence of police and anti-immigrant mobs, demonstrate the central connections between the processes of translation and the experience of “commoning”: multitudes of strangers, in transit and staying put, invent new means of communicating with others, new modes of acting together, new sites of encounter and assembly���in short, they constitute a new common without ever losing their singularities.Through processes of translation, the singularities together form a multitude. Migrants are a coming community, poor but rich in languages, pushed down by fatigue but open to physical, linguistic, and social cooperation. Any political subjectivities seeking to take the word with legitimacy today must learn how to speak (and to act, live, and create) like migrants.” (pp.152-3)

Now, on one level, I can appreciate the transvaluation going on here – instead of conceiving of migrants as absolutely wretched, objects of pity at best and hatred at worst, H&N are trying to conceive the migrant as subject, and follow the arc of political potential which therefore emerges. I think that’s valuable as far as it goes, and actually in its own terms, as a gesture against much of predominant discourse, I think it’s fine. It’s also a common move among those influenced by Negri and working on migration, especially Sandro Mezzadra. But there’s something missing here. Most migrants don’t want to be migrants: either they don’t want to have migrated at all, or they want something quite at odds with the way H&N conceive of them here – stability and citizenship. For many, the most fervent hope is that ‘migrant’ is a temporary position. One of the things that’s awkward about the polemical dismissal of the body of concepts emanating from the republican tradition is that H&N lose the ability to operate in this conceptual realm, the realm which frames most political desires articulated by their resistant subjects. It seems to me a more difficult, but more rewarding thing to attempt to think through and beyond those terms, as especially ‘sovereignty’ and ‘citizenship’ are two of the key sites of struggle for the next few decades.

Anyway –– listen to the interview! Read the book!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

the study of signs (w2)

This week we looked at semiology and how data for semiotic analysis can be gathered using web scraping tools.

Reading

Semiology

Chandler begins to explain semiology by showing what a broad sweep it takes in its study - it could include linguistics, art, film, written language, even music.

My favourite definition was Barthes’, who declared that 'semiology aims to take in any system of signs, whatever their substance and limits; images, gestures, musical sounds, objects, and the complex associations of all of these, which form the content of ritual, convention or public entertainment: these constitute, if not languages, at least systems of signification' (Barthes 1967, 9). I think of semiology as the process by which we understand what we see, and it’s interesting to think of how that extends beyond sight.

Chandler defined some other terms that crop up in analysis, I liked the definition of a ‘text’, as recorded in some way so it is physically independent of the sender or receiver. A text is something we can engage in, detached from its creator. However, it’s interesting to think of ‘dynamic’ texts - for example, I analysed an app interface last semester. The app was developed as a dynamic interface which is personalised by the user - it was impossible for my experience of it to be detached from me as the ‘receiver’.

Chandler talked about how a medium becomes transparent the more it is used by people, so we write instinctively on a computer because it has become the natural way to record things. However, media is a subject which decisively interrupts our ‘unthinking’ ways of communication. I am really interested in how using different messaging applications (e.g. Whatsapp vs. Messenger) changes the way people communicate. This research question would involve some semiotic analysis of interface design, and inextricably the message content and patterns of communication.

Using social semiotic analysis: beyond the self(ie)

Zhao, S. and Zappavigna, M. (2018) ‘Beyond the self: Intersubjectivity and the social semiotic interpretation of the selfie’, New Media & Society, 20(5), pp. 1735–1754.

This paper sets out to "problematise some fundamental assumptions of the selfie" (1748). I like the idea of a "micro-autobiography of the present moment" (Schesler, 2014) (1739). Selfies convey the 'hereness' of that person in that moment in that place. It's not just "look at this place" or "look at me" it's look at me, here in this place in this moment. The selfie is diary-esque in its logging. With snapchat it’s not even about recording or remembering, it's about capturing the fleeting moment only to be shared briefly.

It’s interesting to think about selfies in relation to the way women are seen or how they see themselves. In traditional photography there is the viewer, the subject and the photographer, in a selfie, photographer and subject are one (1741). As women grow up with an understanding that they are the ‘object’ (Berger), does the selfie subject-ify them? Is the selfie a way of reclaiming the dynamic of observed vs. observer? (1740) The selfie may tell others to look at us, but we are the artist. While we may be criticised for our vanity, we put the mirror in our own hand (ref. to Berger).

I disagreed with some of the arguments being made in this paper. The writers argue that a selfie is about showing one’s perspective, more than oneself. I think this may be true for some kinds of selfies, but as someone who has (a) taken a fair few selfies and (b) spent some time on instagram. I would argue that selfies can be about situating oneself in a situation, but seem a compromised way of showing one's perspective. Surely a thoughtfully taken photo of what you are seeing or experiencing is a better reflection of your perspective? Surely taking a picture of yourself, if that shows your perspective, suggests your focus is self-orientated, inward looking rather than outward looking? I think a photo taken by a person, says “look at what I’m seeing”, whereas a selfie says “look at me”.

Project

The accessible icon project: design activism

The project was started by Sara Hendren and Brian Glenney in Boston. Sara ran a blog called "Abler" where she wrote about "about prosthetics in the ordinary sense, but also about assistive technologies in the far less ordinary sense: low tech tools, hybrid technologies, art works, and more" (source: ablersite.org).

This project, which was originally a street art project, recognises that design influences the way we see people, and semiotics have an impact on our judgements about the world. So many of the signs (understood in the general sense, like toilet signs) we see on a daily basis are abstract or iconic symbols which we have learned to associate a meaning to, to the point where we are not conscious of the signification process. A 99% Invisible podcast episode ‘Icons for Access’ looks at this project. The podcast is about the designed world, and this specific episode explores the value of internationally recognised icons, an implicit consideration of the importance of semiotics in communication.

This project reminds me that I feel embarrassed and sad about the way us able-bodied people are willing to ‘other’ people with disabilities. Even the improved symbol draws upon a stereotype of what a person with a disability looks like. How can invisible disabilities be respresented? What compromises are we making when we choose icons to represent abstract ideas? I believe inclusive icon design is important, especially where a person is supposed to select an icon and say “yes, this is me” or walk through a door which tells them “this is where you belong. See Clue’s take on inclusive icon design.

Design activism is designed to challenge ways of thinking, and interrogate exisiting and accepted design principles. This project is activism because it speaks to a wider issue of ableism in society. The purpose of the (original) icon is to provide access to people who are disabled, allowing them to navigate public spaces designed for able-bodied people.

“Feeling nostalgic” or feeling-nostalgic.png

Task - scraping

to view the data I had to be on the page where I found it

I chose a site where every image had it's own page, I couldn't figure out how to group them so I had to scrape individually

chose to scrape a smaller sample to make this do-able

some of the data I scraped didn't feel super useful, and the data I actually wanted (the images) I had to manually scrape. at my level of understanding, the scraper didn't feel very useful.

it was cool to see the website dissected, almost in parts instead of as a functioning whole

Analysis: the name of the comic is not designed to introduce it or 'anchor' it (Barthes), it functions as a placeholder, taking words from the relay text so the image has a name. The name does not allude to the story in the comic at all.

0 notes

Note

Have you read any of the official English translations of danmei novels? Would you recommend them to someone who is practicing reading in Chinese but not quite at the level of understanding everything, and wants to double check the meanings with translations?

nope, haven't read any of the licensed English translations! I generally figure if I've read them in the original I don't need to re-read them in translation, so alas I cannot offer any comment on their merit as potentially instructive texts