#william p. thompson

Text

William Irwin Thompson, Evil and World Order

570 notes

·

View notes

Text

tessa thompson and michelle williams via harper's bazaar us

#angels <3#p: tessa thompson#p: michelle williams#*mine#mine: edits#photography!#fashion!#fashion#michelle williams#tessa thompson#met gala#met gala 2024

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear White People (2014) dir. Justin Simien

#Dear White People#2010s#movie#уважаемые белые люди#Tessa Thompson#Tyler James Williams#Kyle Gallner#Teyonah Parris#Brandon P Bell#Brittany Curran#Marque Richardson II#Dennis Haysbert

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sandman Comics: Original Artists Library

A reference post from the Sandman March Mania event

I thought it might be nice to have all the artists of the Sandman March Mania fandom event in one post, because it's slightly cumbersome to go through the tags and find each individual post. You can also go through the four rounds here (the links send you to all matches and their daily roundups, which contain the contributions of everyone who took part. I would have loved to include them all, but Tumblr hit me over the head with the 100 link limit):

Please keep in mind that a few original Sandman artists are missing from this post because to qualify for the event, they had to be a main artist (usually the penciller) for the main run and deliver at least one panel that shows Dream’s face. Even so, this is a pretty comprehensive list.

And here they are (“Round xyz” contains my write-up for the week’s brief, “xyz art tag” every post about the artist, including all art, ever posted on my blog):

Allred, Michael

Round One, Allred’s art tag

Amano, Yoshitaka

Round One, Round Two, Amano’s art tag

Bachalo, Chris

Round One, Bachalo’s art tag

Doran, Colleen

Round One, Round Two, Doran’s art tag

Dringenberg, Mike

Round One, Round Two, Round Three, Round Four, Dringenberg’s art tag

Eagleson, Duncan

Round One, Eagleson’s art tag

Hempel, Marc

Round One, Round Two, Hempel’s art tag

Jones, Kelley

Round One, Jones’ art tag

Kieth, Sam

Round One, Kieth’s art tag

Kristiansen, Teddy

Round One, Kristiansen’s art tag

McManus, Shawn

Round One, Round Two, Round Three, Round Four, McManus’ art tag

Muth, Jon J

Round One, Round Two, Round Three, Muth’s art tag

Prado, Miguelanxo

Round One, Round Two, Round Three, Prado’s art tag

Russell, P. Craig

Round One, Round Two, Round Three, Russell’s art tag

Sienkiewicz, Bill

Round One, Sienkiewicz’s art tag

Stevens, Alec

Round One, Stevens’ art tag

Talbot, Bryan

Round One, Talbot’s art tag

Thompson, Jill

Round One, Round Two, Round Three, Round Four, Thompson’s art tag

Vess, Charles

Round One, Vess’ art tag

Wagner, Matt

Round One, Wagner’s art tag

Watkiss, John

Round One, Round Two, Watkiss’ art tag

Woch, Stan

Round One, Woch’s art tag

Williams III, JH

Round One, Round Two, Williams’ art tag

Zulli, Michael

Round One, Round Two, Zulli’s art tag

#the sandman#sandman#the sandman comics#dream of the endless#morpheus#lord morpheus#sandman art#sandman x art#sandman artists#sandman original artists#sandman march mania#sandman art analysis#queue crew

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

F.8.4 Aren’t the enclosures a socialist myth?

The short answer is no, they are not. While a lot of historical analysis has been spent in trying to deny the extent and impact of the enclosures, the simple fact is (in the words of noted historian E.P. Thompson) enclosure “was a plain enough case of class robbery, played according to the fair rules of property and law laid down by a parliament of property-owners and lawyers.” [The Making of the English Working Class, pp. 237–8]

The enclosures were one of the ways that the “land monopoly” was created. The land monopoly referred to feudal and capitalist property rights and ownership of land by (among others) the Individualist Anarchists. Instead of an “occupancy and use” regime advocated by anarchists, the land monopoly allowed a few to bar the many from the land — so creating a class of people with nothing to sell but their labour. While this monopoly is less important these days in developed nations (few people know how to farm) it was essential as a means of consolidating capitalism. Given the choice, most people preferred to become independent farmers rather than wage workers (see next section). As such, the “land monopoly” involves more than simply enclosing common land but also enforcing the claims of landlords to areas of land greater than they can work by their own labour.

Needless to say, the titles of landlords and the state are generally ignored by supporters of capitalism who tend to concentrate on the enclosure movement in order to downplay its importance. Little wonder, for it is something of an embarrassment for them to acknowledge that the creation of capitalism was somewhat less than “immaculate” — after all, capitalism is portrayed as an almost ideal society of freedom. To find out that an idol has feet of clay and that we are still living with the impact of its origins is something pro-capitalists must deny. So are the enclosures a socialist myth? Most claims that it is flow from the work of the historian J.D. Chambers’ famous essay “Enclosures and the Labour Supply in the Industrial Revolution.” [Economic History Review, 2nd series, no. 5, August 1953] In this essay, Chambers attempts to refute Karl Marx’s account of the enclosures and the role it played in what Marx called “primitive accumulation.”

We cannot be expected to provide an extensive account of the debate that has raged over this issue (Colin Ward notes that “a later series of scholars have provided locally detailed evidence that reinforces” the traditional socialist analysis of enclosure and its impact. [Cotters and Squatters, p. 143]). All we can do is provide a summary of the work of William Lazonick who presented an excellent reply to those who claim that the enclosures were an unimportant historical event (see his “Karl Marx and Enclosures in England.” [Review of Radical Political Economy, no. 6, pp. 1–32]). Here, we draw upon his subsequent summarisation of his critique provided in his books Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor and Business Organisation and the Myth of the Market Economy.

There are three main claims against the socialist account of the enclosures. We will cover each in turn.

Firstly, it is often claimed that the enclosures drove the uprooted cottager and small peasant into industry. However, this was never claimed. As Lazonick stresses while some economic historians “have attributed to Marx the notion that, in one fell swoop, the enclosure movement drove the peasants off the soil and into the factories. Marx did not put forth such a simplistic view of the rise of a wage-labour force … Despite gaps and omission in Marx’s historical analysis, his basic arguments concerning the creation of a landless proletariat are both important and valid. The transformations of social relations of production and the emergence of a wage-labour force in the agricultural sector were the critical preconditions for the Industrial Revolution.” [Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor, pp. 12–3]

It is correct, as the critics of Marx stress, that the agricultural revolution associated with the enclosures increased the demand for farm labour as claimed by Chambers and others. And this is the whole point — enclosures created a pool of dispossessed labourers who had to sell their time/liberty to survive and whether this was to a landlord or an industrialist is irrelevant (as Marx himself stressed). As such, the account by Chambers, ironically, “confirms the broad outlines of Marx’s arguments” as it implicitly acknowledges that “over the long run the massive reallocation of access to land that enclosures entailed resulted in the separation of the mass of agricultural producers from the means of production.” So the “critical transformation was not the level of agricultural employment before and after enclosure but the changes in employment relations caused by the reorganisation of landholdings and the reallocation of access to land.” [Op. Cit., p. 29, pp. 29–30 and p. 30] Thus the key feature of the enclosures was that it created a supply for farm labour, a supply that had no choice but to work for another. Once freed from the land, these workers could later move to the towns in search for better work:

“Critical to the Marxian thesis of the origins of the industrial labour force is the transformation of the social relations of agriculture and the creation, in the first instance, of an agricultural wage-labour force that might eventually, perhaps through market incentives, be drawn into the industrial labour force.” [Business Organisation and the Myth of the Market Economy, p. 273]

In summary, when the critics argue that enclosures increased the demand for farm labour they are not refuting Marx but confirming his analysis. This is because the enclosures had resulted in a transformation in employment relations in agriculture with the peasants and farmers turned into wage workers for landlords (i.e., rural capitalists). For if wage labour is the defining characteristic of capitalism then it matters little if the boss is a farmer or an industrialist. This means that the “critics, it turns out, have not differed substantially with Marx on the facts of agricultural transformation. But by ignoring the historical and theoretical significance of the resultant changes in the social relations of agricultural production, the critics have missed Marx’s main point.” [Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor, p. 30]

Secondly, it is argued that the number of small farm owners increased, or at least did not greatly decline, and so the enclosure movement was unimportant. Again, this misses the point. Small farm owners can still employ wage workers (i.e. become capitalist farmers as opposed to “yeomen” — an independent peasant proprietor). As Lazonick notes, ”[i]t is true that after 1750 some petty proprietors continued to occupy and work their own land. But in a world of capitalist agriculture, the yeomanry no longer played an important role in determining the course of capitalist agriculture. As a social class that could influence the evolution of British economy society, the yeomanry had disappeared.” Moreover, Chambers himself acknowledged that for the poor without legal rights in land, then enclosure injured them. For “the majority of the agricultural population … had only customary rights. To argue that these people were not treated unfairly because they did not possess legally enforceable property rights is irrelevant to the fact that they were dispossessed by enclosures. Again, Marx’s critics have failed to address the issue of the transformation of access to the means of production as a precondition for the Industrial Revolution.” [Op. Cit., p. 32 and p. 31]

Thirdly, it is often claimed that it was population growth, rather than enclosures, that caused the supply of wage workers. So was population growth more important than enclosures? Given that enclosure impacted on the individuals and social customs of the time, it is impossible to separate the growth in population from the social context in which it happened. As such, the population argument ignores the question of whether the changes in society caused by enclosures and the rise of capitalism have an impact on the observed trends towards earlier marriage and larger families after 1750. Lazonick argues that ”[t]here is reason to believe that they did.” [Op. Cit., p. 33] Overall, Lazonick notes that ”[i]t can even be argued that the changed social relations of agriculture altered the constraints on early marriage and incentives to childbearing that contributed to the growth in population. The key point is that transformations in social relations in production can influence, and have influenced, the quantity of wage labour supplied on both agricultural and industrial labour markets. To argue that population growth created the industrial labour supply is to ignore these momentous social transformations” associated with the rise of capitalism. [Business Organisation and the Myth of the Market Economy, p. 273]

In other words, there is good reason to think that the enclosures, far from being some kind of socialist myth, in fact played a key role in the development of capitalism. As Lazonick notes, “Chambers misunderstood” the “argument concerning the ‘institutional creation’ of a proletarianised (i.e. landless) workforce. Indeed, Chamber’s own evidence and logic tend to support the Marxian [and anarchist!] argument, when it is properly understood.” [Op. Cit., p. 273]

Lastly, it must be stressed that this process of dispossession happened over hundreds of years. It was not a case of simply driving peasants off their land and into factories. In fact, the first acts of expropriation took place in agriculture and created a rural proletariat which had to sell their labour/liberty to landlords and it was the second wave of enclosures, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, that was closely connected with the process of industrialisation. The enclosure movement, moreover, was imposed in an uneven way, affecting different areas at different times, depending on the power of peasant resistance and the nature of the crops being grown (and other objective conditions). Nor was it a case of an instant transformation — for a long period this rural proletariat was not totally dependent on wages, still having some access to the land and wastes for fuel and food. So while rural wage workers did exist throughout the period from 1350 to the 1600s, capitalism was not fully established in Britain yet as such people comprised only a small proportion of the labouring classes. The acts of enclosure were just one part of a long process by which a proletariat was created.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

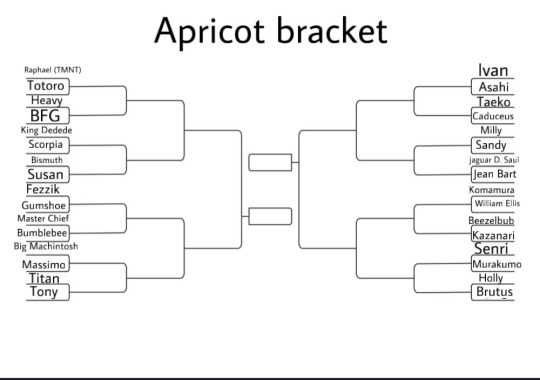

HELLO EVERYONE! I SHALL NOW REVEAL THE BRAKCETS

First up

Wait

MOST FUCKABLE GENTLE GIANT

The A bracket (finished)

Battle 1-16

(most submissions in form 1 and most submissions in form b)

Starts Friday the 9th of June. 5pm CET. The brackets will be posted between the 9-10th of June.

Side A, 9th of June. 5pm to 8pm cet

Raphael Hamato (rise of the TMNT) vs Totoro (my neighbor Totoro)

Heavy (team fortress 2) vs Big Friendly Giant (BFG)

King Dedede (Kirby) vs Scorpia (She-ra)

Bismuth (Steven universe) vs Susan Murphy (monsters vs aliens)

Fezzik (the princess bride) vs Dick Gumshoe (ace attorney)

Master Chief (halo) vs Bumblebee (bumblebee)

Big Macintosh (my little pony: friendship is magic) vs Massimo Marcovaldo (Luca)

The titan (the owl house) vs Tyson (Percy Jackson)

Side B, 10th of June, 5pm to 8pm CET

Ivan Bruel (miraculous ladybug) vs Asahi Azumane (haikyuu)

Takeo Goda (ore monogatari) vs Caduceus Clay (critical role)

Milly Thompson (tri-gun) vs Sandy (Lego monkie kid)

Jaguar D. Saul vs Jean Bart (one piece)

Komamura (bleach) vs William Ellis (identity v)

Beelzebub (obey me) vs Kazanari Genjuurou (symphogear)

Senri (plus anima) vs Murakumo (rune factory 5)

Holly (super lesbian animal rpg) vs Brutus Feels (Kane and feels)

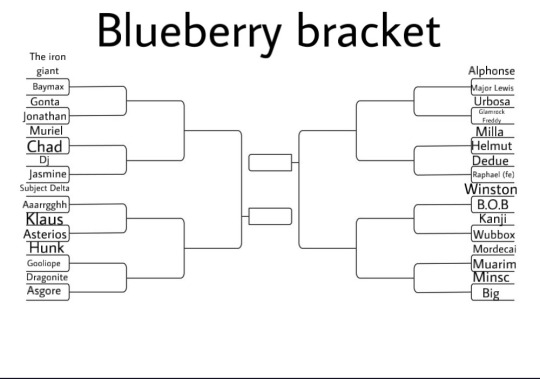

The B bracket (finished)

Battles 17-32

Characters who have returned from the spring bracket and from fandoms I’ve personally interacted with. So the spring bracket but we blacklisted big man

Date: Tuesday 13/6 to Wednesday 14/6, between 5pm to 8pm CET

Side A (Tuesday)

The iron giant vs Baymax (big hero 6)

Gonta gokuhara (danganronpa) vs Jonathan Joestar (JoJo’s bizarre adventure)

Dj (total drama) vs Yasutora “Chad” Sado (bleach

Muriel (the arcana) vs Jasmine (total drama)

Subject Delta (bioshock) vs aaarrrgghh (trollhunters)

Klaus Von Reinherz (kekkai sensen) vs Asterios (fate grand order)

Hunk (Voltron) vs Gooliope Jellington (monster high)

Dragonite (Pokémon) vs Asgore Dreemurr (undertale)

Side B (Wednesday)

Alphonse Elric vs Major Lewis Armstrong (full metal alchemist)

Urbosa (legend of Zelda) vs Glamrock Freddy (five nights at Freddy’s)

Milla Vodello vs Helmut Fullbear (psychonauts)

Dedue Molinaro vs Raphael Kirsten (fire emblem: three houses)

Winston vs B.O.B (overwatch)

Kanji Tatsumi (persona) vs Common Wubbox (my singing monsters)

Mordecai vs Muarim (fire emblem: gay rights path of radiance/radiant dawn)

Minsc & Boo (baldur’s gate) vs Big the cat (sonic the hedgehog)

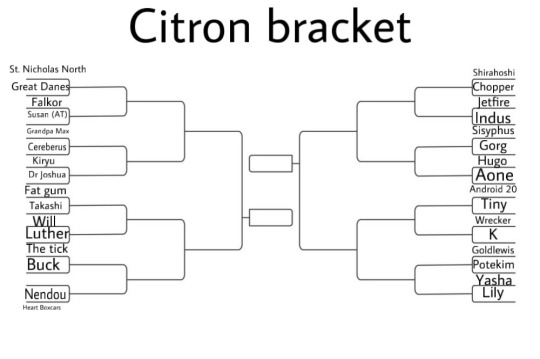

C BRACKET (ongoing)

Battles 33-48

Those who fell in between the A and the D bracket. So this one has some pretty chaotic matchups

Date: Sunday the 18th to Monday the 19th, 5pm to 8pm cet

A bracket: Sunday

Nicholas St North (rise of the guardians) vs Grear Danes (irl)

Falkor the good luck dragon (the never ending story) vs Susan Strong (adventure time)

Grandpa Max (Ben 10) vs Cerberus (Greek mythology)

Kiryu Kazuma (yakuza) vs Dr Joshua Strongbear Sweet (Atlantis)

Fatgum (my hero academia) vs Takashi Morinozuka (ouran highschool host club)

Will Powers (ace attorney) vs Luther (Detroit: become human)

The Tick (the tick 1994) vs Evan Buck Buckley (911 on fox)

Riki Nendou (saiki k) vs Hearts Boxcars (homestuck)

Side B (Monday)

Shirahoshi vs Tony Tony Chopper (one piece)

Jetfire/skyfire (transformers) vs Indus Tarbella (epithet erased)

Sisyphus (hades) Vs Grog Strongjaw (critical role)

Hugo the abominable snowman (looney tunes) vs Aone Takanobu (Haikyuu)

Android 16 (dragon ball) vs Tiny (ever after high)

Wrecker (Star Wars: the bad batch) vs K (virtues last reward)

Goldlewis Dickinson vs Potemkin (guilty gear)

Yasha Nydoorin (critical role) vs Lily Bowen (fall out)

D BRACKET

Battles 49-64

Aka the one where the contestants sadly got the least amount of votes)

Date: Thursday 22/6th to Friday 23/6th 5pm to 8pm CET

Side A: Thursday

lain chu (dragon hunters) vs Panda (tekken)

Isaroth (genshin impact) vs Bizarro (DC red hood and the outlaws)

Jienji (Inuyasha) vs Jackie Wells (cyberpunk 2077)

Looks to the moon (rain world) vs Jogu (naruto)

Bane Perez (identify V) vs Zinnia (super lesbian animal rpg)

Vulkanon (rune factory 4) vs Argus (Greek mythology)

Mountain (ark knights) vs Taiga Saejima (yakuza)

Abbi (Omori) vs Gorem (bakugan)

SIDE B: Friday

Junko (storm hawks) vs Hajin (monstress)

Gylph (super lesbian animal RPG) vs Bongchun (Bongchun bride)

Fitz Fellow (detective grimoire) vs Bubbles (questionable content)

Dubo (omega strikers) vs Bob the titan (Percy Jackson)

Otto the giant water dog (wondla) vs Kurita Ryoukan (Eyeshield 21)

Mele the Horizons Roar (ishura) vs Gentle Bear (dog island)

The Selfish Giant vs Banjo Lilywhile (the hogfather)

Livio the double fang (trigun) vs Hank McCoy (x-men)

I will make propaganda master posts and if you want to add, just use the ask box or dm me with propaganda for one of the characters who’s going to participate. But that’s all!

May the best gentle giant WIN!

SECOND CHANCE BATTLES FOR ROUND 1

27/6, apricot bracket

Battle 1

Battle 2

Battle 3

Battle 4

29/2, shavedown of the apricot bracket

The battle

1/7, blueberry bracket

Battle 1

Battle 2

Battle 3

Battle 4

3/7, shavedown

The battle

4/7, citron bracket

Battle 1

Battle 2

Battle 3

Battle 4

5/7, shavedown

7/7, durian bracket

Battle 1

Battle 2

Battle 3

Battle 4

8/7, shavedown

The (un)official GGSmod messed up someone’s name post

The crime list

Ask game

#gentle giant swag#tumblr tournament#fandom tournament#tumblr bracket#fandom bracket#my neighbor totoro#bioshock#Kirby#jjba#ace attorney#trigun#total drama#danganronpa#the arcana#the iron giant

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

[MANHATTAN PROJECT]. Document commemorating the "Los Alamos New Mexico Atomic Bomb Project" SIGNED BY 30 SCIENTISTS, OFFICERS AND CIVILIANS EMPLOYED ON THE MANHATTAN PROJECT, INCLUDING GEN. LESLIE GROVES, J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER, EDWARD TELLER, ENRICO FERMI and others. Los Alamos, New Mexico n.d. [ca.1945]. 1 page, 4to, even age-toning, minor chipping at top edge of sheet, neatly pasted at corners to stiff backing board.

THE MEN AND WOMEN WHO BUILT THE BOMB: THE SCIENTISTS, ENGINEERS AND TECHNICIANS OF THE MANHATTAN PROJECT

A highly unusual document commemorating the massive, top-secret scientific and technical efforts from 1939 to 1945 which resulted in the successful deployment of the first atomic weapons. At the top of the sheet is a hand-drawn emblem of the Manhattan Project executed in blue, black and red inks. The six-line hand-written text beneath the emblem reads: "We, the undersigned, in grateful appreciation of our joint association in the Los Alamos, New Mexico Atomic Bomb Project, hereby list below a lasting record of friendship spent in working on the World's Greatest Secret The Atomic Bomb."

Below, arranged in three neat columns on dotted lines, are the signatures of 30 individuals including: Leslie R. Groves (General and commanding officer of the Manhattan Engineering District [the Manhattan Project]); J. Robert Oppenheimer (Theoretical Physicist and Director of Los Alamos Laboratory); Samuel K. Allison (Physicist at the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago, who also did the Trinity countdown); Lt. D.H. Dick; Edward Teller (Theoretical Physicist and Head of Thermonuclear Research Group during wartime Los Alamos); Harry S. Allen (Head of Procurement Group and later Supply and Property Group); [?] B. Auker; Lt. Col. Stanley Stewart (Manhattan Project Contracting Officer for Los Alamos); Peter M. Petersen; Gus Schultz (Foreman of the drafting room and machine shop); Dana P. Mitchell (Head of Technical Procurement and later Assistant Director of the Los Alamos Laboratory); L.B. Thompson; Robert McDermott; Enrico Fermi (Theoretical Physicist University of Chicago, also Head of the F Division at Los Alamos as well as Associate Director); Robert F. Bacher (Experimental Physicist and Head of the G[adget] Division at Los Alamos, which developed Fat Man); Capt. W.S. Parsons (Head of Chemical Division); Charles L. Critchfield (Mathematical Physicist who did much of the basic development work on both Little Boy and Fat Man); Edwin Creutz (Experimental Physicist who worked on the magnetic method of implosion diagnostics); William Schuster; M.W. Johnson; J.D. Clartout; Pearce Marshall; John Patrick Callahan; S.H. Young; Capt. W.A. Farina (Head of the Manhattan Projects Property Inventory Section); Margaret K. Thompson; Bruno Rossi (Experimental Physicist who did implosion diagnostics in the RaLa program and at Trinity); A.J. Dickemeyer; Clyde E. Reum (Head of the General Service and Warehouse Section). RARE. We are grateful to Roger Meade, Laboratory Archivist/Historian at Los Alamos for valuable assistance in cataloguing.

Christie’s

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

This set of portfolios entitled “Oriental Ceramic Art, illustrated by Examples from the Collection of W.T. Walters” contains one hundred and sixteen gorgeous chromolithograph plates created by Louis Prang. Prang (1824-1909) was a German immigrant who ran a highly successful printing firm in Boston during the late nineteenth century.

The publication features objects from the collection of successful businessman and art collector William Thompson Walters (1820-1894), which later formed the basis of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, MD.

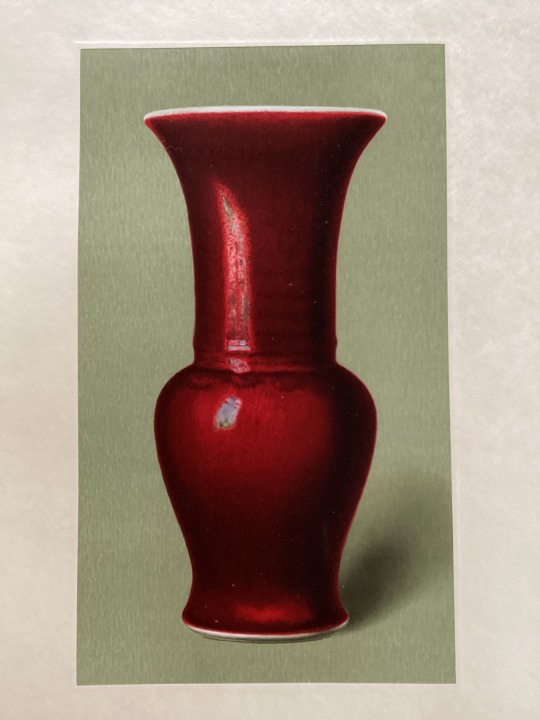

Each plate in the portfolios is accompanied by guard sheet with descriptive letterpress. In this post, we show you Plate 1 from Volume I with the guard sheet as well as the beautiful illustration of a porcelain vase underneath. Sang-de-boeuf is a deep red colored glaze that first appeared in Chinese porcelain at the start of the 18th century. The term is French, meaning “ox blood.”

Plate 1. Lang Yao Beaker.

Beaker-shaped vase (Hua Ku), 16” high, enameled with the crackled glaze of the sang-de-boeuf mottled tints of the celebrated Lang Yao. The interior is coated with the same rich red glaze.

Oriental ceramic art : illustrated by examples from the collection of W. T. Walters : with one hundred and sixteen plates in colors and over four hundred reproductions in black and white

Author / Creator: Bushell, Stephen W. (Stephen Wootton), 1844-1908.

New York : D. Appleton, 1897.

10 v. in portfolios (v, 429 p., 96 col. leaves of plates)

English

HOLLIS number: 990041622660203941

#OrientalCeramicArt#Ceramic#Porcelain#SangDeBoeufGlaze#ChineseCeramic#ChinesePorcelain#LangYaoBeaker#SpecialCollection#ChineseArt#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Obscure Characters List - Male Edition

Obscure Characters I love for some reason. (By obscure I mean characters that have little to no fanfic written about them. Not necessarily characters nobody’s ever heard of.) Don’t ask me to explain why.

A

Abraham Alastor/Anthony Clarke (Dark Pictures Little Hope)

Adam (Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter)

Adam (Hallmark Frankenstein 2004)

Al Capone (Night at the Museum)

Alan McMichael (Crimson Peak)

Alec Fell (Nancy Drew, The Silent Spy)

AM (I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream)

Amphibian Man/The Asset (Shape of Water)

Anthony Walsh (Blood Fest)

Anton Herzen (Professor Layton and the Diabolical Box)

Ardeth Bay (Mummy series)

Armand (Queen of the Damned 2002)

Armando Salazar (Pirates of the Caribbean 5)

B

Barnaby (Sabrina Down Under)

Baron Humbert von Gikkingen (The Cat Returns)

Baron Meinster (Brides of Dracula)

Beast/Hank McCoy (X-Men, Kelsey Grammer version)

Beast/Prince (Beauty and the Beast 2014)

Ben Willis (I Know What You Did Last Summer)

Bernard the elf (Santa Clause series)

Black Phillip (The VVitch)

Blade (Puppetmaster series)

Bughuul (Sinister 1 and 2)

C

Caliban/John Clare (Penny Dreadful)

Captain Frederick Wentworth (Persuasion)

Captain James Hook (Peter Pan 2003)

Cedric Brown (Nanny McPhee)

Christian Thompson (Devil Wears Prada)

Colonel William Tavington (The Patriot)

Cornelis Sandvoort (Tulip Fever)

Crown Prince Ryand'r/Darkfire (DC comics/Teen Titans)

D

Daniel Le Domas (Ready Or Not)

Death (Final Destination series)

Dimitri Allen (Professor Layton and the Unwound Future)

Dimitri Denatos (Mom’s Got a Date With a Vampire)

Dustfinger (Inkheart)

Dr. Alexander Sweet/Dracula (Penny Dreadful)

Dr. Gregory Butler (Happy Death Day 1 & 2)

Dr. Manhattan (Watchmen)

Driller Killer (Slumber Party Massacre 2)

E

Edward Gracey (Haunted Mansion 2003)

Edward Mordrake (Urban Legend/American Horror Story Asylum)

Edward/Eddie “Tex” Sawyer (Texas Chainsaw Massacre 3)

Elemer of the Briar (Elden Ring)

Erik Carriere (Phantom of the Opera 1990)

Ethan (Pilgrim 2019)

F

Father Gascoigne (Bloodborne)

Faustus Blackwood (Chilling Adventures of Sabrina)

Fegan Floop (Spy Kids trilogy)

Fox Mask/Tom (You’re next)

G

George Knightley (Emma)

Ghost/Mitch (Haunt 2019)

Godskin Apostle (Elden Ring)

Godwyn the Golden (Elden Ring)

Gold Watchers (Dark Deception)

Greg (Bodies, Bodies, Bodies)

Grim Matchstick (Cuphead)

Gurranq Beast Clergyman (Elden Ring)

H

Henry Jekyll/Edward Hyde (Broadway, Rob Evan version)

Henry Sturges (Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter)

Hugh Crain (Haunting of Hill House, the book and 1963 film. Not the Flanagan show or 1999 movie remake)

Hugo Butterly (Nancy Drew, Danger by Design)

I

Ingemar (Midsommar)

J

Jack Ferriman (Ghost Ship)

Jack Worthing/Uncle Jack (We Happy Few)

Jafar (Once Upon a Time, not the Wonderland spin-off)

Jan Valek (John Carpenter’s Vampires)

Jefferson "Seaplane" McDonough/Alex (Jumanji 2 and 3)

Jervis Tetch/Mad Hatter (Arkhamverse! Video Games)

Jester (Puppetmaster series)

John (He’s Out There)

Joseph “Joey” Mallone (Blackwell series)

Juan (The Forever Purge)

Juno Hoslow, Knight of Blood (Elden Ring)

K

Kalabar (Halloweentown)

Kenneth Haight (Elden Ring)

Killer Moth/Drury Walker (Teen Titans)

King Paimon (Hereditary)

L

Lamb Mask/Craig (You’re next)

Lamplighter (The Boys)

Launder Man (Crypt TV)

Lawrence “Larry” Gordon (Saw series)

Loki (Apsulov: End of Gods)

Lucifer (Devil’s Carnival 1 & 2)

M

Magic Mirror (Snow White 1937/Shrek)

Man in the Mask (The Strangers)

Manon (The Craft)

Man-Thing (Marvel’s Werewolf By Night)

Marco Polo/Merman (Crypt TV)

Marcus Corvinus (Underworld series)

Markus Boehm (Nancy Drew, the Captive Curse)

Mephistopheles (Faust’s Albtraum)

Micolash, Host of the Nightmare (Bloodborne)

Miquella (Elden Ring)

Mirror Man (Snow White and the Huntsman)

Mr. Crow/Aldous Vanderboom (Rusty Lake series)

Mr. Le Bail (Ready Or Not)

Mr. Slausen (Tourist Trap)

N

Nigel Billingsley (Jumanji 2 and 3)

Night’s Cavalry (Elden Ring)

Nothing (The Night House)

P

Pazuzu (The Exorcist)

Pierre Despereaux (Psych)

Prince Anton Voytek (Vampire 1974)

Prince Escalus (Romeo and Juliet, no particular adaptation)

Prince Quartus (Stardust)

Prince Septimus (Stardust)

Professor Petrie/Phantom of the Opera (Phantom of the Opera 1962)

Peter Quint (Turn of the Screw, the book and maybe some other adaptations. Not the Bly Manor Flanagan show.)

R

Reese Kelly (Scarlet Hollow)

Rene Belloq (Indiana Jones, Raiders of the Lost Ark)

Roland Voight (Hellraiser 2022)

Ronin (Star Trek)

Rorschach (Watchmen)

Rupert Giles (Buffy the Vampire Slayer)

Rusty Nail (Joyride trilogy)

S

Salem Saberhagen (Sabrina the Teenage Witch)

Sam Wayne (Scarlet Hollow)

Silver Surfer/Norrin Radd (Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer)

Simon Jarrett (SOMA)

Sir Lancelot (Night at the Museum 3)

Sportacus (LazyTown)

Starscourge Radahn (Elden Ring)

STEM (Upgrade)

Sutter Cane (In the Mouth of Madness)

T

Thantos DuBaer (Twitches 1 and 2)

The Auditor (Hellraiser: Judgment)

The Babadook (The Babadook)

The Black Knight Ghost (Scooby Doo 2 Monsters Unleashed)

The Curator (Dark Pictures Anthology)

The Designer (Devil’s Carnival 2)

The Djinn/Nathaniel Demerest/Professor Joel Barash/Steven Verdel (Wishmaster series)

The Faun (Pan’s Labyrinth)

The Fox (The Little Prince 1974)

The Jester (The Jester, A Short Horror Film series)

The Kinderfänger (Crypt TV)

The Knight/Tarhos Kovács (Dead by Daylight)

The Look-See (Crypt TV)

The Man (Carnival of Souls)

The Merman (Cabin In The Woods)

The Metal Killer (Stage Fright 2014)

The Mirror (Oculus)

The Narrator (Stanley Parable)

The Other (Hellfest)

The Phantom (Phantom Manor)

The Projectionist (Pearl)

The T-1000/Cop (Terminator 2, Terminator Genisys)

The Tall Man/The Entity (It Follows)

The Thing (The Thing 1982)

The Torn Prince/Royce Clayton (Thirteen Ghosts remake)

The Torso/James “Jimmy” Gambino (Thirteen Ghosts remake)

Thomas Alexander “Alex” Upton (TAU)

Tiger Mask/Dave (You’re Next)

Tommy Ross (Carrie, 1976)

V

Valak (The Conjuring)

Valdack and his real world counterpart (Black Mirror)

Van Pelt (Jumanji 2)

Venable (Wrong Turn 2021)

Viktor (Underworld series)

Viktor Frankenstein/Dr. Whale (Once Upon a Time)

Vladislaus Dracula (Van Helsing 2004)

W

Wade Thornton (Nancy Drew, Ghost of Thornton Hall)

Wesley Wyndam-Pryce (Buffy the Vampire Slayer)

Westley/Dread Pirate Roberts (The Princess Bride)

Wildwind/Dark Skull, Stormy Weathers, and Lightning Strikes (Scooby Doo and the Legend of the Vampire)

“William”/The Headless Figure (Crypt TV)

William "Billy" Butcherson (Hocus Pocus 1 and 2)

X

Xenan the Centaur (Xena Warrior Princess)

#Obscure characters list#character list#Obscure characters#Characters list#Obscure fictional characters#Male Characters List#will be added to over time#I'm not even gonna attempt to tag this any further#It'd just be too much#Don't ask me to explain#I don't know what to tell you#characters I like inexplicably

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 2.26

Beer Birthdays

Gabriel Sedlmayr II (1811)

Frederick C. Miller (1906)

Art Larrance (1944)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Tex Avery; cartoon director (1908)

Johnny Cash; singer, songwriter (1932)

Jackie Gleason; actor, comedian (1916)

Plato; philosopher (428 BCE)

Theodore Sturgeon; writer (1918)

Famous Birthdays

Robert Alda; actor (1914)

Grover Cleveland Alexander; Philadelphia Phillies P (1887)

Erykah Badu; singer (1971)

William Baumol; economist (1922)

Michael Bolton; pop singer (1953)

Godfrey Cambridge; actor (1933)

"Buffalo" Bill Cody; scout, entertainer (1846)

Honore Daumier; artist (1808)

"Fats" Domino; singer, pianist (1928)

Herbert Henry Dow; chemical manufacturer (1866)

Bill Duke; actor (1943)

Kevin Dunn; actor (1956)

Marshall Faulk; St. Louis Rams RB (1973)

William Frawley; actor (1887)

Jennifer Grant; actor (1966)

Victor Hugo; writer (1802)

Betty Hutton; actor (1921)

John Harvey Kellogg; dietician, doctor (1852)

Kara Monaco; model (1983)

Teresa Palmer; actor (1986)

Tony Randall; actor (1920)

Mitch Ryder; rock singer (1945)

Levi Strauss; inventor (1829)

Jenny Thompson; swimmer (1973)

Elihu Vedder; artist, illustrator (1836)

Wenceslas of Bohemia; ruler (1361)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is there a masterlist of, like, actors and celebrities that have come forward for trans rights?

I know the internet has all sorts of collections of people who've done something messed up and those always depress me but reading about David Tennant being supportive in the face of the UK government and current legislation and stuff really hit me and I'd love to be able to see who else is out there standing up for us and what's right.

If not, here's a list I'm putting together, feel free to add to it or add context in the notes if you want! I'm including celebrities who have affirmed their support for trans family members even if they're not doing other activism. I'm also only listing celebrities I know of, and this list does not in any way endorse any problematic stuff any of them may have done outside of the topic.

Just making this list is cheering me up a lot tbh

David Tennant

Daniel Radcliffe

Emma Watson

Rupert Grint

Pedro Pascal

Jamie Lee Curtis

Ariana Grande

Lady Gaga

Don Cheadle

Taylor Swift

Gabrielle Union

Colin Mochrie

Andrew Garfield

K. A. Applegate

Cher

David Arquette

Jannifer Lopez

Angeline Jolie

Vanessa Carlton

Kevin Bacon

Nick Offerman

Sheryl Crow

Hayley Williams

Sade

Anna Paquin

Jon Oliver

Jon Stewart

Colbert

Keanu Reeves

Anthony Rapp

Charlize Theron

Zendaya

Kate Winslet

Shawn Mendes

LeBron James

Anthony Stewart Head

Gerard Way

Bea Arthur

Hozier

Wil Wheaton

Warren Beatty

Lynda Carter

Selena Gomez

Billy Ray Cyrus

Rihanna

Megan Thee Stallion

Cardi B

Shania Twain

Anna Kendrick

Kendrick Lamar

Dolly Parton

Drew Barrymore

Mark Ruffalo

Bruce Springsteen

Taron Egerton

Orville Peck

Charles Barkley

Yungblood

Sigourney Weaver

Bad Bunny

Emma Thompson

Liev Schreiber

Magic Johnson

Anne Hathaway

Chris Pratt

Ryan Reynolds

Chris Evans

Margot Robbie

Sandra Bullock

Christina Aguilera

Mariah Carey

Adele

Dua Lipa

Tony Hawk

Matt Berry

Harry Styles

John Leguizamo

Patrick Stewart

Jon Bernthal

David Lynch

Russel T Davies

Garth Brooks

Paris Hilton

Lucy Lawless

Bill Nye

Ally Sheedy

Miley Cyrus

Joan Jett

Mike Shinoda

Dick Van Dyke

Eric Idle

Ian Mackellan

Benedict Cumberbatch

Matthew Lillard

P!nk

Adam Conover

Megan Fox

Gwen Stefani

Terry Pratchett

Neil Gaiman

Mara Wilson

David Attenborough

Michael Sheen

Joaquin Phoenix

Halsey

John Lithgow

Jim Norton

Mr Beast

M Shadows

John Cusack

Hugh Jackman

Penn Jilette

Janet Jackson

Brie Larson

Bjork

Britney Spears

Jenna Ortega

Selena Gomez

oh man there are so many more i can't even keep listing but here's a list of 500 feminists who signed an open letter supporting trans women and girls

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dark Horse Presents

Aliens: Havoc (1997)

Aliens: Havoc #1-2 (1997)

by Mark Schultz & Kent Williams & Leif Jones & Duncan Fegredo & D’Israeli & John Totleben & Arthur Adams & Gary Gianni & Geof Darrow & George Pratt & Igor Kordej & Paul Lee & John K. Snyder III & Mark A. Nelson & Peter Bagge & Brian Horton & Dave Taylor & Kelley Jones & Guy Davis & Kellie Strom & Jay Stephens & Jerry Bingham & Kevin Nowlan & Frank Teran & Joel Naprstek & Travis Charest & P. Craig Russell & Adrian Potts & Sean Phillips & Rebecca Guay & Jon J. Muth & Kilian Plunkett & Ron Randall & John Pound & Gene Ha & Vania Zarouliov & Sergio Aragonés & John Paul Leon & Derek Thompson & David Lloyd & Moebius & Dave Cooper & Mike Allred & Tony Millionaire

#comic book art#20th century fox#dark horse comics#comic books#aliens#aliens podcast#xenomorph#dark horse presents#aliens (1986)#Gene Ha#arthur adams#art adams#michael allred#travis charest#kelly jones#steve bissette#moebius#dave cooper#p craig russell#geoff darrow#mark nelson#dave taylor#duncan fegredo#igor kordey#sergio aragones#kevin nowlan#guy davis

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear White People (2014) dir. Justin Simien

#Dear White People#2010s#movie#уважаемые белые люди#Tessa Thompson#Tyler James Williams#Kyle Gallner#Teyonah Parris#Brandon P Bell#Brittany Curran#Marque Richardson II#Dennis Haysbert

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round One Wrap-Up And Round Two Announcement

Wow, what a Round One it’s been!

We’ve compiled all the pairings and results for you again so you can check which of your favourites went through, and whom we’ve already lost along the way (we’re as sad about some of these as you).

Michael Allred vs Jon J Muth (78%)

Michael Zulli (89.2%) vs Bill Sienkiewicz

Teddy Kristiansen vs Yoshitaka Amano (78.4%)

Shawn McManus (90.7%) vs Kelley Jones

Alec Stevens vs Miguelanxo Prado (63.2%)

Chris Bachalo vs Marc Hempel (56.4%)

Stan Woch vs JH Williams III (81.5%)

Duncan Eagleson vs Jill Thompson (80%)

Matt Wagner vs Colleen Doran (69.7%)

Charles Vess vs P. Craig Russell (83.1%)

Sam Kieth vs Mike Dringenberg (91.3%)

John Watkiss (78.1%) vs Bryan Talbot

Each link contains the OP and the daily roundups—please make sure to check them out because many people have shared amazing art and thoughts on why their favourite designed the Dream they preferred.

On Monday, we will be back with Round Two. Here comes the next bracket (you can still find the round one overview here):

Yes, we’re already agonising, too—it’s only going to get trickier from here.

And to already prepare yourselves:

In round two, we will ask you for the Dream/Morpheus/Daniel panel(s) by your favourite artist that show your least favourite depiction.

Sounds like a contradiction in terms? Not really. This time, we are looking for consistency in design. Consequently, we want to see all those panels that make you go:

“They didn’t get him quite right here,” or, “That’s downright ugly to me.”

That might be easier to do for the artist you don’t support, but we want you to do it for your favourite.

Really dig deep, and no cheating—sometimes it’s good to examine one’s bias 😉

We will obviously remind you on each individual post, but this gives you a bit of time to prepare. If you have any questions, hit us up.

We’ll see you all again on Monday 6pm/London with our first match-up, and it’s going to be a tough one…

Event organisers: @writing-for-life and @tickldpnk8

#the sandman#sandman#dream of the endless#morpheus#neil gaiman#sandman march mania#round one wrap-up#round two announcement#sandman x art#sandman art#queue crew#sandman comics#vertigo comics#dc comics

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

G.1.1 What about their support of the free market?

Many, particularly on the “libertarian”-right, would dismiss claims that the Individualist Anarchists were socialists. By their support of the “free market” the Individualist Anarchists, they would claim, show themselves as really supporters of capitalism. Most, if not all, anarchists would reject this claim. Why is this the case?

This because such claims show an amazing ignorance of socialist ideas and history. The socialist movement has had a many schools, many of which, but not all, opposed the market and private property. Given that the right “libertarians” who make such claims are usually not well informed of the ideas they oppose (i.e. of socialism, particularly libertarian socialism) it is unsurprising they claim that the Individualist Anarchists are not socialists (of course the fact that many Individualist Anarchists argued they were socialists is ignored). Coming from a different tradition, it is unsurprising they are not aware of the fact that socialism is not monolithic. Hence we discover right-“libertarian” guru von Mises claiming that the “essence of socialism is the entire elimination of the market.” [Human Action, p. 702] This would have come as something of a surprise to, say, Proudhon, who argued that ”[t]o suppress competition is to suppress liberty itself.” [The General Idea of the Revolution, p. 50] Similarly, it would have surprised Tucker, who called himself a socialist while supporting a freer market than von Mises ever dreamt of. As Tucker put it:

”Liberty has always insisted that Individualism and Socialism are not antithetical terms; that, on the contrary, the most perfect Socialism is possible only on condition of the most perfect Individualism; and that Socialism includes, not only Collectivism and Communism, but also that school of Individualist Anarchism which conceives liberty as a means of destroying usury and the exploitation of labour.” [Liberty, no. 129, p. 2]

Hence we find Tucker calling his ideas both “Anarchistic Socialism” and “Individualist Socialism” while other individualist anarchists have used the terms “free market anti-capitalism” and “free market socialism” to describe the ideas.

The central fallacy of the argument that support for markets equals support for capitalism is that many self-proclaimed socialists are not opposed to the market. Indeed, some of the earliest socialists were market socialists (people like Thomas Hodgskin and William Thompson, although the former ended up rejecting socialism and the latter became a communal-socialist). Proudhon, as noted, was a well known supporter of market exchange. German sociologist Franz Oppenheimer expounded a similar vision to Proudhon and called himself a “liberal socialist” as he favoured a free market but recognised that capitalism was a system of exploitation. [“Introduction”, The State, p. vii] Today, market socialists like David Schweickart (see his Against Capitalism and After Capitalism) and David Miller (see his Market, State, and community: theoretical foundations of market socialism) are expounding a similar vision to Proudhon’s, namely of a market economy based on co-operatives (albeit one which retains a state). Unfortunately, they rarely, if ever, acknowledge their debt to Proudhon (needless to say, their Leninist opponents do as, from their perspective, it damns the market socialists as not being real socialists).

It could, possibly, be argued that these self-proclaimed socialists did not, in fact, understand what socialism “really meant.” For this to be the case, other, more obviously socialist, writers and thinkers would dismiss them as not being socialists. This, however, is not the case. Thus we find Karl Marx, for example, writing of “the socialism of Proudhon.” [Capital, vol. 1, p. 161f] Engels talked about Proudhon being “the Socialist of the small peasant and master-craftsman” and of “the Proudhon school of Socialism.” [Marx and Engels, Selected Works, p. 254 and p. 255] Bakunin talked about Proudhon’s “socialism, based on individual and collective liberty and upon the spontaneous action of free associations.” He considered his own ideas as “Proudhonism widely developed and pushed right to these, its final consequences” [Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings, p. 100 and p. 198] For Kropotkin, while Godwin was “first theoriser of Socialism without government — that is to say, of Anarchism” Proudhon was the second as he, “without knowing Godwin’s work, laid anew the foundations of Anarchism.�� He lamented that “many modern Socialists” supported “centralisation and the cult of authority” and so “have not yet reached the level of their two predecessors, Godwin and Proudhon.” [Evolution and Environment, pp. 26–7] These renown socialists did not consider Proudhon’s position to be in any way anti-socialist (although, of course, being critical of whether it would work and its desirability if it did). Tucker, it should be noted, called Proudhon “the father of the Anarchistic school of Socialism.” [Instead of a Book, p. 381] Little wonder, then, that the likes of Tucker considered themselves socialists and stated numerous times that they were.

Looking at Tucker and the Individualist anarchists we discover that other socialists considered them socialists. Rudolf Rocker stated that “it is not difficult to discover certain fundamental principles which are common to all of them and which divide them from all other varieties of socialism. They all agree on the point that man be given the full reward of his labour and recognise in this right the economic basis of all personal liberty. They all regard the free competition of individual and social forces as something inherent in human nature … They answered the socialists of other schools who saw in free competition one of the destructive elements of capitalist society that the evil lies in the fact we have too little rather than too much competition, since the power of monopoly has made competition impossible.” [Pioneers of American Freedom, p. 160] Malatesta, likewise, saw many schools of socialism, including “anarchist or authoritarian, mutualist or individualist.” [Errico Malatesta: His Life and Ideas, p. 95]

Adolph Fischer, one of the Haymarket Martyrs and contemporary of Tucker, argued that “every anarchist is a socialist, but every socialist is not necessarily an anarchist. The anarchists are divided into two factions: the communistic anarchists and the Proudhon or middle-class anarchists.” The former “advocate the communistic or co-operative method of production” while the latter “do not advocate the co-operative system of production, and the common ownership of the means of production, the products and the land.” [The Autobiographies of the Haymarket Martyrs, p. 81] However, while not being communists (i.e. aiming to eliminate the market), he obviously recognised the Individualists Anarchists as fellow socialists (we should point out that Proudhon did support co-operatives, but they did not carry this to communism as do most social anarchists — as is clear, Fischer means communism by the term “co-operative system of production” rather than co-operatives as they exist today and Proudhon supported — see section G.4.2).

Thus claims that the Individualist Anarchists were not “really” socialists because they supported a market system cannot be supported. The simple fact is that those who make this claim are, at best, ignorant of the socialist movement, its ideas and its history or, at worse, desire, like many Marxists, to write out of history competing socialist theories. For example, Leninist David McNally talks of the “anarcho-socialist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon” and how Marx combated “Proudhonian socialism” before concluding that it was “non-socialism” because it has “wage-labour and exploitation.” [Against the Market, p. 139 and p. 169] Of course, that this is not true (even in a Marxist sense) did not stop him asserting it. As one reviewer correctly points out, “McNally is right that even in market socialism, market forces rule workers’ lives” and this is “a serious objection. But it is not tantamount to capitalism or to wage labour” and it “does not have exploitation in Marx’s sense (i.e., wrongful expropriation of surplus by non-producers)” [Justin Schwartz, The American Political Science Review, Vol. 88, No. 4, p. 982] For Marx, as we noted in section C.2, commodity production only becomes capitalism when there is the exploitation of wage labour. This is the case with Proudhon as well, who differentiated between possession and private property and argued that co-operatives should replace capitalist firms. While their specific solutions may have differed (with Proudhon aiming for a market economy consisting of artisans, peasants and co-operatives while Marx aimed for communism, i.e. the abolition of money via state ownership of capital) their analysis of capitalism and private property were identical — which Tucker consistently noted (as regards the theory of surplus value, for example, he argued that “Proudhon propounded and proved [it] long before Marx advanced it.” [Liberty, no. 92, p. 1])

As Tucker argued, “the fact that State Socialism … has overshadowed other forms of Socialism gives it no right to a monopoly of the Socialistic idea.” [Instead of a Book, pp. 363–4] It is no surprise that the authoritarian left and “libertarian” right have united to define socialism in such a way as to eliminate anarchism from its ranks — they both have an interest in removing a theory which exposes the inadequacies of their dogmas, which explains how we can have both liberty and equality and have a decent, free and just society.

There is another fallacy at the heart of the claim that markets and socialism do not go together, namely that all markets are capitalist markets. So another part of the problem is that the same word often means different things to different people. Both Kropotkin and Lenin said they were “communists” and aimed for “communism.” However, it does not mean that the society Kropotkin aimed for was the same as that desired by Lenin. Kropotkin’s communism was decentralised, created and run from the bottom-up while Lenin’s was fundamentally centralised and top-down. Similarly, both Tucker and the Social-Democrat (and leading Marxist) Karl Kautsky called themselves a “socialist” yet their ideas on what a socialist society would be like were extremely different. As J.W. Baker notes, “Tucker considered himself a socialist … as the result of his struggle against ‘usury and capitalism,’ but anything that smelled of ‘state socialism’ was thoroughly rejected.” [“Native American Anarchism,” pp. 43–62, The Raven, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 60] This, of course, does not stop many “anarcho”-capitalists talking about “socialist” goals as if all socialists were Stalinists (or, at best, social democrats). In fact, “socialist anarchism” has included (and continues to include) advocates of truly free markets as well as advocates of a non-market socialism which has absolutely nothing in common with the state capitalist tyranny of Stalinism. Similarly, they accept a completely ahistorical definition of “capitalism,” so ignoring the massive state violence and support by which that system was created and is maintained.

The same with terms like “property” and the “free market,” by which the “anarcho”-capitalist assumes the individualist anarchist means the same thing as they do. We can take land as an example. The individualist anarchists argued for an “occupancy and use” system of “property” (see next section for details). Thus in their “free market,” land would not be a commodity as it is under capitalism and so under individualist anarchism absentee landlords would be considered as aggressors (for under capitalism they use state coercion to back up their collection of rent against the actual occupiers of property). Tucker argued that local defence associations should treat the occupier and user as the rightful owner, and defend them against the aggression of an absentee landlord who attempted to collect rent. An “anarcho”-capitalist would consider this as aggression against the landlord and a violation of “free market” principles. Such a system of “occupancy and use” would involve massive violations of what is considered normal in a capitalist “free market.” Equally, a market system which was based on capitalist property rights in land would not be considered as genuinely free by the likes of Tucker.

This can be seen from Tucker’s debates with supporters of laissez-faire capitalism such as Auberon Herbert (who, as discussed in section F.7.2, was an English minimal statist and sometimes called a forerunner of “anarcho”-capitalism). Tucker quoted an English critic of Herbert, who noted that “When we come to the question of the ethical basis of property, Mr. Herbert refers us to ‘the open market’. But this is an evasion. The question is not whether we should be able to sell or acquire ‘in the open market’ anything which we rightfully possess, but how we come into rightful possession.” [Liberty, no. 172, p. 7] Tucker rejected the idea “that a man should be allowed a title to as much of the earth as he, in the course of his life, with the aid of all the workmen that he can employ, may succeed in covering with buildings. It is occupancy and use that Anarchism regards as the basis of land ownership, … A man cannot be allowed, merely by putting labour, to the limit of his capacity and beyond the limit of his person use, into material of which there is a limited supply and the use of which is essential to the existence of other men, to withhold that material from other men’s use; and any contract based upon or involving such withholding is as lacking in sanctity or legitimacy as a contract to deliver stolen goods.” [Op. Cit., no. 331, p. 4]

In other words, an individualist anarchist would consider an “anarcho”-capitalist “free market” as nothing of the kind and vice versa. For the former, the individualist anarchist position on “property” would be considered as forms of regulation and restrictions on private property and so the “free market.” The individualist anarchist would consider the “anarcho”-capitalist “free market” as another system of legally maintained privilege, with the free market distorted in favour of the wealthy. That capitalist property rights were being maintained by private police would not stop that regime being unfree. This can be seen when “anarcho”-capitalist Wendy McElroy states that “radical individualism hindered itself … Perhaps most destructively, individualism clung to the labour theory of value and refused to incorporate the economic theories arising within other branches of individualist thought, theories such as marginal utility. Unable to embrace statism, the stagnant movement failed to adequately comprehend the logical alternative to the state — a free market.” [“Benjamin Tucker, Liberty, and Individualist Anarchism”, pp. 421–434, The Independent Review, vol. II, No. 3, p. 433] Therefore, rather than being a source of commonality, individualist anarchism and “anarcho”-capitalism actually differ quite considerably on what counts as a genuinely free market.

So it should be remembered that “anarcho”-capitalists at best agree with Tucker, Spooner, et al on fairly vague notions like the “free market.” They do not bother to find out what the individualist anarchists meant by that term. Indeed, the “anarcho”-capitalist embrace of different economic theories means that they actually reject the reasoning that leads up to these nominal “agreements.” It is the “anarcho”-capitalists who, by rejecting the underlying economics of the mutualists, are forced to take any “agreements” out of context. It also means that when faced with obviously anti-capitalist arguments and conclusions of the individualist anarchists, the “anarcho”-capitalist cannot explain them and are reduced to arguing that the anti-capitalist concepts and opinions expressed by the likes of Tucker are somehow “out of context.” In contrast, the anarchist can explain these so-called “out of context” concepts by placing them into the context of the ideas of the individualist anarchists and the society which shaped them.

The “anarcho”-capitalist usually admits that they totally disagree with many of the essential premises and conclusions of the individualist anarchist analyses (see next section). The most basic difference is that the individualist anarchists rooted their ideas in the labour theory of value while the “anarcho”-capitalists favour mainstream marginalist theory. It does not take much thought to realise that advocates of socialist theories and those of capitalist ones will naturally develop differing notions of what is and what should be happening within a given economic system. One difference that has in fact arisen is that the notion of what constitutes a “free market” has differed according to the theory of value applied. Many things can be attributed to the workings of a “free” market under a capitalist analysis that would be considered symptoms of economic unfreedom under most socialist driven analyses.

This can be seen if you look closely at the case of Tucker’s comments that anarchism was simply “consistent Manchesterianism.” If this is done then a simple example of this potential confusion can be found. Tucker argued that anarchists “accused” the Manchester men “of being inconsistent,” that while being in favour of laissez faire for “the labourer in order to reduce his wages” they did not believe “in liberty to compete with the capitalist in order to reduce his usury.” [The Individualist Anarchists, p. 83] To be consistent in this case is to be something other — and more demanding in terms of what is accepted as “freedom” — than the average Manchesterian (i.e. a supporter of “free market” capitalism). By “consistent Manchesterism”, Tucker meant a laissez-faire system in which class monopolies did not exist, where capitalist private property in land and intellectual property did not exist. In other words, a free market purged of its capitalist aspects. Partisans of the capitalist theory see things differently, of course, feeling justified in calling many things “free” that anarchists would not accept, and seeing “constraint” in what the anarchists simply thought of as “consistency.” This explains both his criticism of capitalism and state socialism:

“The complaint of the Archist Socialists that the Anarchists are bourgeois is true to this extent and no further — that, great as is their detestation for a bourgeois society, they prefer its partial liberty to the complete slavery of State Socialism.” [“Why I am an Anarchist”, pp. 132–6, Man!, M. Graham (ed.), p. 136]

It should be clear that a “free market” will look somewhat different depending on your economic presuppositions. Ironically, this is something “anarcho”-capitalists implicitly acknowledge when they admit they do not agree with the likes of Spooner and Tucker on many of their key premises and conclusions (but that does not stop them claiming — despite all that — that their ideas are a modern version of individualist anarchism!). Moreover, the “anarcho”-capitalist simply dismisses all the reasoning that got Tucker there — that is like trying to justify a law citing Leviticus but then saying “but of course all that God stuff is just absurd.” You cannot have it both ways. And, of course, the “anarcho”-capitalist support for non-labour based economics allow them to side-step (and so ignore) much of what anarchists — communists, collectivists, individualists, mutualists and syndicalists alike — consider authoritarian and coercive about “actually existing” capitalism. But the difference in economic analysis is critical. No matter what they are called, it is pretty clear that individualist anarchist standards for the freedom of markets are far more demanding than those associated with even the freest capitalist market system.

This is best seen from the development of individualist anarchism in the 20th century. As historian Charles A. Madison noted, it “began to dwindle rapidly after 1900. Some of its former adherents joined the more aggressive communistic faction … many others began to favour the rising socialist movement as the only effective weapon against billion-dollar corporations.” [“Benjamin R. Tucker: Individualist and Anarchist,” pp. 444–67, The New England Quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. p. 464] Other historians have noted the same. “By 1908,” argued Eunice Minette Schuster “the industrial system had fastened its claws into American soil” and while the “Individualist Anarchists had attempted to destroy monopoly, privilege, and inequality, originating in the lack of opportunity” the “superior force of the system which they opposed … overwhelmed” them. Tucker left America in 1908 and those who remained “embraced either Anarchist-Communism as the result of governmental violence against the labourers and their cause, or abandoned the cause entirely.” [Native American Anarchism, p. 158, pp. 159–60 and p. 156] While individualist anarchism did not entirely disappear with the ending of Liberty, social anarchism became the dominant trend in America as it had elsewhere in the world.

As we note in section G.4, the apparent impossibility of mutual banking to eliminate corporations by economic competition was one of the reasons Voltairine de Cleyre pointed to for rejecting individualist anarchism in favour of communist-anarchism. This problem was recognised by Tucker himself thirty years after Liberty had been founded. In the postscript to a 1911 edition of his famous essay “State Socialism and Anarchism”, he argued that when he wrote it 25 years earlier “the denial of competition had not effected the enormous concentration of wealth that now so gravely threatens social order” and so while a policy of mutual banking might have stopped and reversed the process of accumulation in the past, the way now was “not so clear.” This was because the tremendous capitalisation of industry now made the money monopoly a convenience, but no longer a necessity. Admitted Tucker, the “trust is now a monster which … even the freest competition, could it be instituted, would be unable to destroy” as “concentrated capital” could set aside a sacrifice fund to bankrupt smaller competitors and continue the process of expansion of reserves. Thus the growth of economic power, producing as it does natural barriers to entry from the process of capitalist production and accumulation, had resulted in a situation where individualist anarchist solutions could no longer reform capitalism away. The centralisation of capital had “passed for the moment beyond their reach.” The problem of the trusts, he argued, “must be grappled with for a time solely by forces political or revolutionary,” i.e., through confiscation either through the machinery of government “or in denial of it.” Until this “great levelling” occurred, all individualist anarchists could do was to spread their ideas as those trying to “hasten it by joining in the propaganda of State Socialism or revolution make a sad mistake indeed.” [quoted by James J. Martin, Op. Cit., pp. 273–4]

In other words, the economic power of “concentrated capital” and “enormous concentration of wealth” placed an insurmountable obstacle to the realisation of anarchy. Which means that the abolition of usury and relative equality were considered ends rather than side effects for Tucker and if free competition could not achieve these then such a society would not be anarchist. If economic inequality was large enough, it meant anarchism was impossible as the rule of capital could be maintained by economic power alone without the need for extensive state intervention (this was, of course, the position of revolutionary anarchists like Bakunin, Most and Kropotkin in the 1870s and onwards whom Tucker dismissed as not being anarchists).

Victor Yarros is another example, an individualist anarchist and associate of Tucker, who by the 1920s had abandoned anarchism for social democracy, in part because he had become convinced that economic privilege could not be fought by economic means. As he put it, the most “potent” of the “factors and forces [which] tended to undermine and discredit that movement” was “the amazing growth of trusts and syndicates, of holding companies and huge corporations, of chain banks and chain stores.” This “gradually and insidiously shook the faith of many in the efficacy of mutual banks, co-operative associations of producers and consumers, and the competition of little fellows. Proudhon’s plan for a bank of the people to make industrial loans without interest to workers’ co-operatives, or other members, seemed remote and inapplicable to an age of mass production, mechanisation, continental and international markets.” [“Philosophical Anarchism: Its Rise, Decline, and Eclipse”, pp. 470–483, The American Journal of Sociology, vol. 41, no. 4, p. 481]

If the individualist anarchists shared the “anarcho”-capitalist position or even shared a common definition of “free markets” then the “power of the trusts” would simply not be an issue. This is because “anarcho”-capitalism does not acknowledge the existence of such power, as, by definition, it does not exist in capitalism (although as noted in section F.1 Rothbard himself proved critics of this assertion right). Tucker’s comments, therefore, indicate well how far individualist anarchism actually is from “anarcho”-capitalism. The “anarcho”-capitalist desires free markets no matter their result or the concentration of wealth existing at their introduction. As can be seen, Tucker saw the existence of concentrations of wealth as a problem and a hindrance towards anarchy. Thus Tucker was well aware of the dangers to individual liberty of inequalities of wealth and the economic power they produce. Equally, if Tucker supported the “free market” above all else then he would not have argued this point. Clearly, then, Tucker’s support for the “free market” cannot be abstracted from his fundamental principles nor can it be equated with a “free market” based on capitalist property rights and massive inequalities in wealth (and so economic power). Thus individualist anarchist support for the free market does not mean support for a capitalist “free market.”

In summary, the “free market” as sought by (say) Tucker would not be classed as a “free market” by right-wing “libertarians.” So the term “free market” (and, of course, “socialism”) can mean different things to different people. As such, it would be correct to state that all anarchists oppose the “free market” by definition as all anarchists oppose the capitalist “free market.” And, just as correctly, “anarcho”-capitalists would oppose the individualist anarchist “free market,” arguing that it would be no such thing as it would be restrictive of property rights (capitalist property rights of course). For example, the question of resource use in an individualist society is totally different than in a capitalist “free market” as landlordism would not exist. This is a restriction on capitalist property rights and a violation of a capitalist “free market.” So an individualist “free market” would not be considered so by right-wing “libertarians” due to the substantial differences in the rights on which it would be based (with no right to capitalist private property being the most important).

All this means that to go on and on about individualist anarchism and it support for a free market simply misses the point. No one denies that individualist anarchists were (and are) in favour of a “free market” but this did not mean they were not socialists nor that they wanted the same kind of “free market” desired by “anarcho”-capitalism or that has existed under capitalism. Of course, whether their economic system would actually result in the abolition of exploitation and oppression is another matter and it is on this issue which social anarchists disagree with individualist anarchism not whether they are socialists or not.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

BEYOND THE TIME BARRIER (1960) – Episode 171 – Decades Of Horror: The Classic Era

“Sterile?” Yes, sterile! And they weren’t talking about surgical instruments. Join this episode’s Grue-Crew – Chad Hunt, Daphne Monary-Ernsdorff, Doc Rotten, and Jeff Mohr – as they blast off to the distant future of… 2024? The movie is Beyond the Time Barrier (1960).

Decades of Horror: The Classic Era

Episode 171 – Beyond the Time Barrier (1960)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel!

Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content!

https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

ANNOUNCEMENT

Decades of Horror The Classic Era is partnering with THE CLASSIC SCI-FI MOVIE CHANNEL, THE CLASSIC HORROR MOVIE CHANNEL, and WICKED HORROR TV CHANNEL

Which all now include video episodes of The Classic Era!

Available on Roku, AppleTV, Amazon FireTV, AndroidTV, Online Website.

Across All OTT platforms, as well as mobile, tablet, and desktop.

https://classicscifichannel.com/; https://classichorrorchannel.com/; https://wickedhorrortv.com/

In 1960, a military test pilot is caught in a time warp that propels him to the year 2024 where he finds a plague has sterilized the world’s population.

Director: Edgar G. Ulmer

Writer: Arthur C. Pierce

Produced by: Robert Clarke (produced by); Robert L. Madden (executive producer); John Miller (executive producer)

Casting by: Baruch Lumet (uncredited), Sidney Lumet (uncredited)

Music by: Darrell Calker

Production Design by: Ernst Fegté

Makeup Department:

Corinne Daniel (hairdresser) (as Corrine Daniel)

Jack P. Pierce (makeup creator) (NOT the mutants!)

Special Effects by: Roger George

Costumer: Jack Masters

Selected Cast:

Robert Clarke as Maj. William Allison

Darlene Tompkins as Princess Trirene

Arianne Ulmer as Capt. Markova (as Arianne Arden)

Vladimir Sokoloff as The Supreme

Stephen Bekassy as Gen. Karl Kruse

John Van Dreelen as Dr. Bourman (as John van Dreelen)

Boyd ‘Red’ Morgan as Captain (as Red Morgan)

Ken Knox as Col. Marty Martin

Don Flournoy as Mutant

Tom Ravick as Mutant

Neil Fletcher as Air Force Chief

Jack Herman as Dr. Richman

James ‘Ike’ Altgens as Secretary Lloyd Patterson (as James Altgens)

William Shephard as Gen. York (as William Shapard)

John Loughney as Gen. Lamont

Russ Marker as Col. Curtis (as Russell Marker)

Arthur C. Pierce as Mutant Escaping from Jail (uncredited)

Malcolm Thompson as Guard (uncredited)

While testing the latest and greatest airship just above the atmosphere, Major William Allison (Robert Clarke) accidentally travels to the apocalyptic future of… 2024! Little did they know. Beyond the Time Barrier (1960) is a low-budget, sci-fi B-picture from director Edgar G. Ulmer (The Black Cat, 1934; Detour, 1945) and writer Arthur C. Pierce (The Cosmic Man, 1959; The Human Duplicators, 1965). To Chad’s dismay, the plot includes a lot of walking and talking across a set filled with inverted pyramids. Oh, and the mutants… sigh. Check out what the Grue Crew has to say about this B&W, time-travel trainwreck. Also, stick around for the usual batch of feedback from past episodes.

You might also want to check out these Decades of Horror: The Classic Era episodes:

THE HIDEOUS SUN DEMON (1958) – Episode 41: w/Robert Clarke as writer, director, producer, and star

THE BLACK CAT (1934) – Episode 67: directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, starring Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff

At the time of this writing, Beyond the Time Barrier is available for streaming from the Classic Sci-Fi Movie Channel, Amazon Prime, and Tubi. The film is available on physical media as a Blu-ray from Kino Lorber in the Edgar G. Ulmer Sci-Fi Collection, a trio of films that also includes The Man from Planet X (1951) and The Amazing Transparent Man (1960).

Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror: The Classic Era records a new episode every two weeks. Up next in their very flexible schedule, as chosen by guest host Michael Zatz, is The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), another silent scream starring Lon Chaney! Sanctuary! Sanctuary! Incidentally, this will be the Classic Era’s tenth discussion of a silent film.

Please let them know how they’re doing! They want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans: leave them a message or leave a comment on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel, the site, or email the Decades of Horror: The Classic Era podcast hosts at [email protected]

To each of you from each of them, “Thank you so much for watching and listening!”

Check out this episode!

2 notes

·

View notes