#yemayá

Photo

Yemanja: Wisdom from the African Heart of Brazil (2015), Donna Roberts, Donna Read, Brazil

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

You don't step on me twice

You can't step into the same water twice

Remember?

the water follows

And me too

Ora YêYê, Oxum. Odoyá, Yemanja. It's just love. Have mercy on us.

#artists on tumblr#black art#black tumblr#orishas#support black business#support black creators#umbanda#candomblé#orixás#yemayá#yemaya#iemanjá#yemanjá#oshun#oshunenergy#oxum#loja de umbanda#encontro ancestral

356 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silvia d yemanjá

entregando asé no Dia do Bará do Mercado Público

13/06/2023

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harmonia Rosales, Yemaya with Ibeji, 2022, oil on wood panel, 36” × 36”.

#harmonia rosales#afrolatina artist#women artists#yoruba#yoruba religion#yemayá#yemanjá#orisha#orishas

99 notes

·

View notes

Photo

🌿ORACIÓN PARA TOMAR CUALQUIER HIERBA DE LA NATURALEZA🌿 Ozain te saludo con respeto, solicito tú permiso para tomar parte de tú legado, es para (sanar, tomar, limpiar etc.) Esta hierba (nombre de la planta) en cambio te dejo este derecho (ofrenda) como gratitud de recibir la medicina. Gracias, gracias, gracias padre *Esta oración básicamente pidiendo permiso a conciencia, cualquier persona lo puede realizar #ozain #orishas #eshu #eleggua #oggún #oshun #Yemayá #obatala #shango #oyá #espiritismo #palomonte #Ifá #puebla #loscabos #mexico #chiapas #tlaxcala #guadalajara #españa #chile #perú #estadosunidosdenorteamerica #miami #diloggun https://www.instagram.com/p/CrkBAvgtElu/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#ozain#orishas#eshu#eleggua#oggún#oshun#yemayá#obatala#shango#oyá#espiritismo#palomonte#ifá#puebla#loscabos#mexico#chiapas#tlaxcala#guadalajara#españa#chile#perú#estadosunidosdenorteamerica#miami#diloggun

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

My next African inspired RPG character is a magic using warrior ⚔️💧

She’s based on the Sea spirit, Yemoja/Yemaya from Yoruba religion.

#digital art#artists on tumblr#blacktober#african mythology#yemayá#yemoja#rpg#jrpg#anime#black artist

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life is way too short to spend it at war with yourself. Beating yourself up over and over about every little thing will not magically make everything better.

You must stop with the negative self-talk...it is getting you nowhere. What happened, happened...You can't change the past and no amount of self-hatred can.

Today, start over and choose to move forward with your life...you are not a bad person, a failure, or a disappointment.

What you can do, is change your future. Your pain is your strength...it won’t last forever.

Give yourself time to heal, take life day by day. Every day you survive is another step forward to your greatness!

So be patient with yourself...growth comes in many forms!

Be proud of yourself for how far you’ve come...continue to push through and keep fighting cause this too shall pass!

🐚🌊🧜🏿♀️

Theresa Cattouse

Twin Soul Connections

#love#spirituality#karmicstar#orisha#yoruba#santeria#yemanjá#yemayá#yemanja#african ancestry#african spirituality#soul#self love#self care#self aware queen#self help#self awakening#self awareness

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artist profile: anetteprs on instagram

I don’t talk about her often and how my practice and culture relates to her — for some reason (whether it’s a pull from Her or not, idk) I feel the need to keep her more private — but She’s indeed close to my heart 🩵

1 note

·

View note

Text

When I need balance in my life, I look to Yemaya, the goddess of the ocean and nurturing.

0 notes

Photo

Finalizado… #dibucedario2023 Los tres últimos que faltaban: la letra x #xochiquetzal , la letra y #yemayá y la letra z #zeus #mitologia @rbesonias (en Arroyo, Castilla y León, Spain) https://www.instagram.com/p/CpI3yarMDrO/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Text

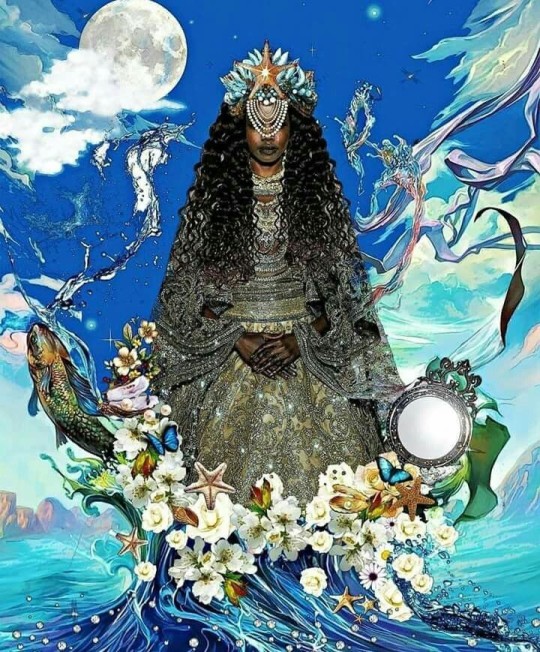

Iemanjá (also spelled Yemayá. Yemoja, Iemoja, or Yemaya) is one of the most powerful orishas. She is the mother of all living things, rules over motherhood and owns all the waters of the Earth. She gave birth to the stars, the moon, the sun and most of the orishas. Yemaya makes her residence in life-giving portion of the ocean (although some of her roads can be found in lagoons or lakes in the forest). Yemaya’s aché is nurturing, protective and fruitful. Yemaya is just as much a loving mother orisha as she is a fierce warrior that kills anyone who threatens her children.

Yemaya can be found in all the waters of the world, and because of this she has many aspects of “caminos” (roads), each reflecting the nature of different bodies of water. She, like Oshún, carries all of the experiences of womanhood within her caminos. Contrary to popular belief she is not just a loving mother. Some of Yemaya’s caminos are fierce warriors who fight with sabers or machetes and bathe in the blood of fallen enemies. Other roads are masterful diviners that have been through marriage, divorce and back again. Some roads of Yemaya have been rape survivors, while other roads betrayed her sisters out of jealousy and spite. No matter what camino of Yemaya, all are powerful female orishas and fiercely protective mothers.

Yemaya has a very special relationship with two orishas in particular: Oshún and Chango. Oshún is often depicted as Yemaya’s sister, and Yemaya allows Oshún to take residence in her rivers. Yemaya and Oshun relate to one another like typical sisters; they love each other and also have a bit of sibling rivalry. Chango and Yemaya are inseparable. Some followers of Santeria say Yemaya is Chango’s mother. The two of them eat together and Chango shares his wealth with Yemaya. Yemaya helped mold Chango into the wise leader he was meant to be from birth (although he initially lacked the skill to rule with grace).

You can find me at: Instagram / Pinterest / Marketplace

#Iemanjá#iemanja#yemayá#yemanjá#umbanda#candomblé#santeria#artists on tumblr#black art#black tumblr#orishas#orixás#shango#xangô#oxum#osun#osùn#support black creators#support black business#support black people#odoyá#encontro ancestral

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yemaya found me in a moment my heart needed its first great comfort. I will be forever grateful for having something to hold on to then.

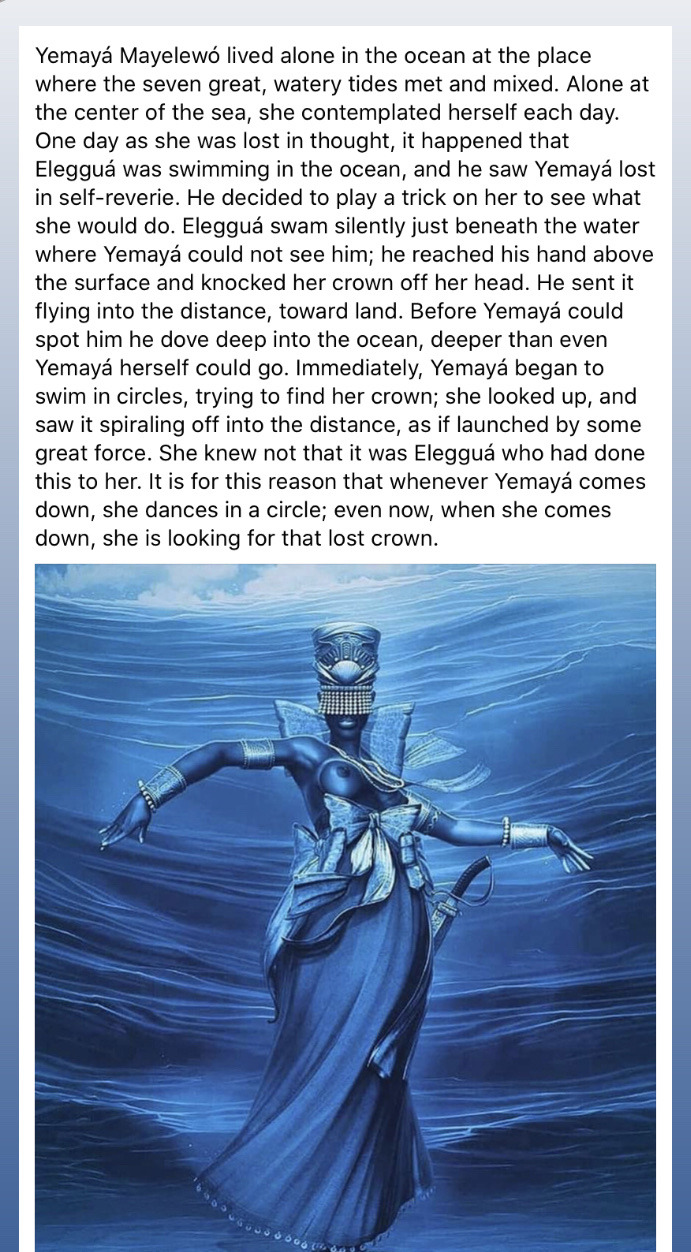

I learned this story years later and it is astoundingly a match to what I’ve experienced & what I aim to avoid from men always.

Maintaining my Crown, no games or compromise.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"El que mal anda, mal acaba" Refrán: Ofun tonti Ogunda #orishas #eshu #eleggua #oggún #oshun #Yemayá #obatala #shango #oyá #espiritismo #palomonte #Ifá #puebla #loscabos #mexico #chiapas #tlaxcala #guadalajara #españa #chile #perú #estadosunidosdenorteamerica #miami https://www.instagram.com/p/CmNnzqitmay/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#orishas#eshu#eleggua#oggún#oshun#yemayá#obatala#shango#oyá#espiritismo#palomonte#ifá#puebla#loscabos#mexico#chiapas#tlaxcala#guadalajara#españa#chile#perú#estadosunidosdenorteamerica#miami

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mermaids and Mr Freud...

What do you think when you hear the word “mermaid”? Chances are, you’ll imagine a beautiful girl with a sparkling fish tail, naked breasts, flowing hair, gazing into a mirror: a scene straight out of early 20th-century Golden Age illustrators Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac. Or perhaps you see Ariel, Disney’s 1989 cartoon version of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, with her cherry-red hair and purple shell bikini. That romanticized – and Disneyfied – picture of a mermaid seems fated to endure with this year’s live-action The Little Mermaid film (though the casting of Halle Bailey in the title role has prompted as much racist backlash as it has celebration. The mermaid of Andersen’s 1837 fairytale was white, say the purists.)

But Andersen himself drew on a far older, stranger, and more subversive folklore to write his story. His tale of a mermaid who, falling in love with a human prince, is forced to sacrifice her tail and her voice in order to become human, was deeply influenced by Undine, the 1811 novella by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, which in turn was inspired by the 16th-century occultist Paracelsus, who coined the word “undine” to describe an elemental water spirit who can only gain a soul by marrying a human. And mermaid legends, like so many other fairytales, have been shared in many parts of the world for millennia.

One of the earliest mermaid stories dates back to sometime around 1000 BC. In Assyrian mythology, the goddess Atargatis, who was venerated for thousands of years all over the Middle East, attains a half-fish, half-human form after throwing herself into a lake. The Yoruba spirit, Yemoja, who is represented as a mermaid, appears under other names as an ocean and river mother goddess – Yemaja, Yemanjá, Yemoyá, Yemayá – across half the world. Mami Wata – a water deity sometimes known as La Sirène - revered in Haiti and many parts of Africa, often appears as a mermaid, with a mirror that allows the passage from one plane of reality to another. And so it goes, from the ningyo of Japanese folklore to the sjókonar of Norse sagas. It is one of the most powerful archetypes in our shared dreaming.

Nor were mermaids always understood to be mythological. Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, European bestiaries and illuminated manuscripts portrayed mermaids as real creatures. On several occasions fishermen have claimed to have caught them in their nets. Early explorers reported mermaid sightings – although it is more likely that they were dolphins, seals or manatees, mistaken for mermaids by sailors expecting to encounter exotic beasts on their journey. Since then, humans have stubbornly continued to look for proof that mermaids are real (so far, without success).

What does the mermaid mean? Why is the half-fish half-woman such a potent, enduring legend? At the heart of these stories is the question of women’s power. Fairy tales and folklore have played an important role in challenging societal roles and giving people opportunities to discuss difficult or taboo subjects through the safety of metaphor – in this case, through the image of a woman whose irresistible sexual power over men is balanced by her own inability to function sexually or to reproduce. And in the days when pregnancy and childbirth often proved fatal, that might not have been such a bad thing. The mermaid cannot be raped, or forced to give birth. Not being human, she is not bound by the conventions of human society or the laws of the Church. She enjoys both the freedom and the sensuality of her element without any of the attendant dangers or discomforts.

In folklore, the mermaid has independence, and can exercise sexual power over men, which makes her ultimately dangerous, unnatural: a monster. Perhaps this is why so many ancient myths and medieval bestiaries depict mermaids as untrustworthy, deceitful creatures, leading sailors to their doom. Their bodies are all sexual promise, but no sexual reward; and their voices are so enchanting as to drive men to madness. Unable to fulfil what some believe to be a woman’s biological destiny, they are often portrayed as soulless. Because a woman who uses without being used, who seduces without being seduced, who moves through water and air – whereas men are doomed to drown if they venture into the mermaid’s world – is a challenge to God, to the patriarchy, and to order itself.

In The Little Mermaid, Andersen tamed this older, more radical tradition. The moralism of his tale serves the dual purpose of mastering the mermaid – of making her fall victim to a human’s charms, rather than the more traditional way around – and taking away her power. The mermaid, made helpless by love of her prince, gives up her native element and the autonomy that comes with it, and exchanges it – via a witch’s spell – for a pair of feet, though walking causes her terrible pain. She also relinquishes the power of speech, which means that she is incapable of expressing her love in any way but the physical. And if her prince falls in love with someone else, then the mermaid is doomed to die on the instant, and to forfeit the soul for which she has sacrificed everything. Her entire being – her very existence – becomes dependent on the love and approval of her prince. Her independence, her challenge to the patriarchal status quo is gone. Though the ending of Andersen’s tale is – to a certain degree – redemptive (the mermaid, refusing to take the life of her prince in order to save her own life, is borne aloft by spirits of air and promised an eternal soul), it seems very cruel, especially as the heroine is only fifteen years old. A contemporary reader might well see in Andersen’s telling a warning to an emerging women’s movement – women’s power has often been seen as fragile, unnatural, and at the mercy of emotion.

Unlike the tragedy of Andersen’s mermaid and prince (and of Fouqué’s Undine), the 1989 Disney film rewards Ariel and Eric with a happily-ever-after ending. And it tells their story in a cheery, colourful palette (a stark contrast to Kay Nielsen’s original dark, eerie concept drawings for the film), which while being pleasingly child-friendly, also reduces the mermaid’s essential alienness, and minimizes her sacrifice, thereby making her tale into little more than a love story with a little added jeopardy.

But Disney also perpetuated other tropes. It is meaningful that the sea witch who provides the mermaid with the spell fits the older-woman archetype well represented in fairy tales: embittered by age, envious of the little mermaid’s youth and beauty. She is the one who demands the mermaid’s voice as payment for her services: a potent image of an older generation, silencing the voices of youth. (In Andersen’s telling, she too is the one who demands that the mermaid’s sisters cut off their hair in order to save their sibling.) The older woman is filled with rage and contempt for the younger woman; taking pleasure in their humiliation and the loss of their power. And as the tentacled Ursula in the Disney version, she is especially monstrous.

Over the centuries, fairy stories have always been reinvented to serve the needs of the changing times. And people have often fretted about this. (In 1853, Charles Dickens criticised the trend for rewriting fairytales to fit didactic, contemporary concerns.) But perhaps that the meaning of the mermaid has drifted further and further away from its origins in ancient folklore should not be cause for too much concern. Today, the mermaid has become the symbol of the trans community, whose members often feel the generational divide especially keenly. And there are endlessly imaginative ways to retell the tradition. (In 2008’s Ponyo, Hayao Miyazaki spins his tale of a goldfish who longs to be human into a charming meditation on childhood.)

Like the ever-evolving traditions of fairytales, magic, too, is transformative. In stories, magic acts as a metaphor for the change we seek to effect in our lives, in ourselves, in the world around us. Perhaps that is why fairy tales resonate so deeply with us. Why else would we cling to them, retell them in so many ways? They teach us not that magic exists, but that change is possible. They teach us not that dragons exist, but that monsters can be overcome. And they teach us to hope, in the face of a world that seems to be getting harsher and more confusing by the day, that sometimes love can save us, and that, even in the face of the cruellest kind of tyranny, we can still keep control of our fate, and hope for a happy ending –not just a Disney wedding, but something perhaps more satisfying. In films like Moana - or more recently Ruby Gillman, Teenage Kraken – the love story is with the sea; a story of claiming, rather than giving up power. Mermaids – in all their aspects – are still working their magic on us. And now, perhaps more than ever, it’s time to listen to their song.

79 notes

·

View notes