Text

Week 10 - Digital Citizenship and Conflict: Social Media Governance

*TRIGGER WARNING*: This post discusses topics related to toxic masculinity, misogyny, online radicalization, rape culture, gender-based violence and self-harm. Some readers may find certain themes distressing. Reader discretion is advised.

Dua Lipa Was Right, "The Kids Ain't Alright"! – Toxic Masculinity on the Internet and Its Harmful Effect on Young Male Generation

"When will we stop saying things? 'Cause they're all listening No, the kids ain't alright" - (Lipa, 2020)

Growing up online as a Gen Z kid, conflict was just part of the deal—it’s what shapes every community (Carter, 2023). But in digital spaces, power dynamics crank up the tension, with each community having its own messy politics (Farrell, 2013). Some voices get amplified, others get drowned out (Haslop et al., 2021, p. 1421), and somehow, even in spaces meant to be inclusive, the scales are always tipped (binhwantstoeatoreo, 2025).

Attached blog post 1. Digital Citizenship and the Inequalities of Intersectionality (binhwantstoeatore, 2025).

In the past few years, terms like “incel” and “redpill” have gone mainstream (Solea & Sugiura, 2023), wrapped up in the guise of self-improvement (Rosdahl, 2024). On TikTok, young men casually tear down women, glorify dominance, and treat misogyny like it’s just another trend. Slurs against women and queer people run unchecked, fueling toxic masculinity and rape culture.

Dua Lipa’s Boys Will Be Boys isn’t just a song—it’s a warning. “The kids ain’t alright” feels more relevant than ever as digital spaces feed young men a steady stream of misogyny, power, and hate. What they consume online is shaping them—and the reality is, they’re indeed not alright.

The Rise of the Manosphere: A Digital Breeding Ground for Conflict

The “manosphere” is everywhere—TikTok, YouTube, X (formerly Twitter)—flooded with Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs), Pick-Up Artists (PUAs), incels, and “redpill” influencers, all claiming to stand up for men. And yeah, men do have real struggles. But instead of offering actual solutions, these spaces just turn into echo chambers of bitterness, entitlement, and straight-up misogyny (Marwick & Caplan, 2018). They push this idea that men are somehow under attack by feminism and modern society, twisting real frustrations into an “us vs. them” mindset (Johanssen, 2021).

The scariest part is you don’t have to go looking for this stuff—it finds you. Algorithms on YouTube, TikTok, and other platforms aggressively push these ideologies toward young men, often after just a few clicks. Research by Papadamou et al. (2021) found that even when starting from a non-incel-related video, users have a 6.3% chance of landing on one within just five recommendations. That’s all it takes to get pulled into the rabbit hole.

Dangerous Figures in the Manosphere

Andrew Tate is one of the most influential—and most dangerous—figures in the manosphere. He preys on young boys’ insecurities (Rich & Bujalka, 2023), packaging misogyny as self-improvement. His brand is built on Pick-Up Artist (PUA) ideology, reducing women to conquests won through manipulation and control (Center on Extremism, 2024).

And his influence runs deep. A 2023 poll by Hope not Hate found that 79% of 16- and 17-year-old British boys had engaged with his content. But it’s not just teenagers—his reach extends to adulthood. A 2023 Internet Matters poll revealed that 56% of young fathers (under 35) approve of his messaging, proving that his rhetoric isn’t just warping young minds—it’s shaping masculinity across generations.

But Tate’s impact goes way beyond bad dating advice. He normalizes abuse, pushing the idea that being a “real man” means dominance at all costs. He openly claims that women exist for male pleasure and deserve punishment if they don’t “fall in line,” feeding a toxic cycle where violence against women isn’t just excused—it’s encouraged.

Figure 1. Andrew Tate's misogynistic tweet.

With over 10 million followers on X, Tate’s influence is impossible to ignore—especially through the lens of Social Influence Theory. Young boys latch onto his views because of normative social influence—the pressure to fit in and gain peer acceptance (Nolan et al., 2008). At the same time, informational social influence fills the gap for those lacking alternative perspectives, making his rhetoric feel like the ultimate truth (Wittenbrink & Henly, 1996). The more they’re exposed to his content, the more it warps their idea of masculinity, pushing the belief that aggression and dominance are the only ways to earn respect and succeed (Mucak, 2024).

Figure 2. Andrew Tate's X account.

Some manosphere influencers take a subtler approach, like Wes Watson and the Liver King, who push a version of masculinity centered on emotional suppression and physical dominance. The Liver King, for example, dismisses vulnerability, insisting that “real men don’t cry over spilled milk” (LiverKing, 2024). While framed as self-improvement, this mindset can blur the line between resilience and toxic masculinity, discouraging emotional depth and promoting aggression as strength (Chung, 2024).

Meanwhile, podcasters like Sneako, Fresh & Fit, and Myron Gaines repackage misogyny as dating advice, treating women as adversaries rather than partners (Hall, 2025). They build loyal audiences by mocking female guests, trivializing consent, and framing relationships as battles for control (Price, 2024).

youtube

Attached video 1. A cut clip from Myron Gaines' podcast where he criticized and mocked his female guest on relationship' needs wise (FreshandFit, 2024). This clip alone massed more than 163k views and 13k likes.

Put all of this together, and you get a toxic pipeline where boys learn that being a man means being in control—of their emotions, of their relationships, and, most dangerously, of women. Vulnerability is mocked. Respect is mistaken for weakness. And the cycle of misogyny goes on.

The Impact on Women: A Cycle of Online Harassment & Rape Culture

Manosphere communities have turned online harassment into a weapon, targeting women—especially feminist voices—while using digital platforms as battlegrounds for gendered abuse (Marwick & Caplan, 2018, p. 550). The scale of this issue is staggering—during the 2024 U.S. election, Instagram ignored 93% of 1,000 documented cases of sexist and racist abuse, including death and rape threats, aimed at female political candidates (Navarro, 2025). By failing to act, these platforms send a clear message: abusers can continue unchecked, their behavior not just tolerated but practically endorsed by the very systems claiming to enforce “community guidelines.”

Some manosphere influencers go beyond implicit misogyny, outright suggesting that women deserve punishment for defying traditional gender roles (Sundén & Paasonen, 2019, p. 7). The impact of this rhetoric is tangible—26% of women surveyed by Amnesty Global Insights (2017) reported receiving threats of physical or sexual violence simply for existing online. This isn’t just a matter of offensive speech; it’s a deliberate strategy to instill fear and reinforce power imbalances in digital spaces.

Figure 3. Amnesty's (2017) poll on online harrassment types women get.

Figure 4. Laura Bates - founder of the Everyday Sexism Project, shared the disturbing sexual harrassment and death/rape threats she received online (Amnesty Global Insights, 2017).

Flood & Pease (2009) argues that exposure to misogynistic online spaces correlates with increased acceptance of rape myths and a diminished understanding of consent. This doesn’t just put women at risk—it distorts young men’s understanding of healthy relationships, leading to a cycle of toxic masculinity and emotional detachment.

The Effect on Young Men: Self-hatred and Bullying

The hate they give (to themselves):

The impact of manosphere ideology on young boys extends far beyond social conditioning—it can take a severe mental toll, leading to internalized hatred and, in some cases, even suicidal thoughts (Over et al., 2025).

A VICE investigation (Gilbert, 2023) uncovered a disturbing trend within incel communities, where a viral scene from the movie Jarhead (2005) featuring Jake Gyllenhaal—depicted the actor with a rifle in his mouth, saying,

“Shoot me. Shoot me in the fucking face.”

The video, captioned “Get shot or see her with someone else?” amassed over 2.1 million views, 440,000 likes, 7,200 comments, and 11,000 shares before its removal. Most comments encouraged the implied suicide, while others expressed deep loneliness, with one user even announcing their intent to end their life within four hours. This reveals how online echo chambers don’t just radicalize young men—they trap them in cycles of despair, reinforcing harmful beliefs that can escalate into real-world harm.

Figure 5. The now deleted TikTok video starring Jake Gyllenhaal (EKO, 2023).

Within the manosphere community, it doesn’t just promote misogyny—it polices masculinity itself, weaponizing it against anyone who doesn’t conform (Vallerga, 2024).

As a young gay man, I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve come across manosphere content that tears down both women and queer people—often in the same breath. Just existing is enough to get hit with slurs, a reminder that these spaces aren’t just hostile to feminism, but to anyone who doesn’t fit their rigid mold of masculinity.

Farrell et al. (2019) found that about 15% of content in Reddit’s manosphere communities contained homophobic rhetoric, making it clear that anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment isn’t just present—it’s baked into the culture. These spaces don’t just reject queer identities; they actively push young gay men to conform to traditional masculinity, fueling internalized homophobia (Thepsourinthone et al., 2020).

For queer youth looking for belonging, this isn’t just exclusion—it’s deeply damaging. It creates a space where you’re either erased or pressured to fit into an idea of manhood that was never meant to include you.

When Labels Push Them Further

Online, young men struggling with dating, confidence, or social skills are often labeled as “incels” or “redpilled” before they even engage with those ideologies.

The new mini-series Adolescence from Netflix, lays bare the struggle of young men trapped between rigid masculinity and online hostility (Rasker, 2025). It highlights how those who don’t fit hyper-masculine ideals face relentless bullying, often being labeled as “incels” or “redpilled”.

youtube

Attached video 2. Netflix's new mini-series 'Adolescene' examines incel culture (The View, 2025).

While meant to critique toxic masculinity, these labels can backfire—pushing vulnerable young boys toward the very spaces that radicalize them (Hemmings, 2023).

O’Malley & Helm (2022) argued that repeated shaming leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy, where young men who felt outcasted on social media could internalize these identities and seek validation from manosphere influencers (Dolan, 2023; Ging, 2019). Over time, this reinforces toxic ideology, as hostility from outsiders makes the manosphere feel like a refuge (Reinicke, 2022, p. 10).

Adolescence doesn’t just expose these dynamics—it forces us to rethink how we engage with young men who feel lost. Instead of shaming them into extremism, we need to address their struggles before the manosphere does (Hogan, 2025).

What Can Be Done?

So far, awareness of Andrew Tate’s harmful influence on young boys is growing both online and in schools. English teacher Kirsty Pole went viral on Twitter, urging educators to recognize his misogynistic and homophobic rhetoric as a serious threat (Sharp, 2022).

Figure 6. Kirsty's tweet raising awareness about Tate's misogynistic and homophobic ideology (@TeacherBusy, 2022).

Besides, cyberfeminism actively challenges the manosphere by reclaiming digital spaces for empowerment while simultaneously confronting its ideology (Gajjala & Mamidipudi, 1999). One of its key strategies is the use of humor and memes as tools of resistance, turning the very online culture that fuels the manosphere into a means of critique and subversion (Dafaure, 2022).

Figure 7. A meme highlighting one of the many contradictions within male supremacist ideology (McCullough, 2023).

Figure 8. A meme revealing how manosphere influencers oversimplify men’s mental and emotional struggles (McCullough, 2023).

However, the cycle of conflict surrounding this issue persists, further entrenching divisions rather than fostering resolution. Adolescence has sparked heated debate online—while some applaud its attempt to address a pressing societal concern, others frame it as “toxic feminism” or “feminist propaganda.” (thenewsmovement, 2025)

Figure 9. Positive comments regarding the Netflix's mini-series.

Figure 10. Attacking comments.

Any critique of male socialization is weaponized as proof of an alleged feminist agenda against men, pushing vulnerable young men further into these spaces.

"Boys Will Be Boys," or Can We Do Better?

Dua Lipa’s song was a warning—a reflection of how normalized toxic masculinity has been in our culture. But we are now seeing an even more dangerous evolution of this problem, amplified by the reach of the internet and social media algorithms that reward controversy and polarization. If we don’t address this now, we risk losing a generation of young men to a dangerous ideology that thrives on their anger and insecurities.

The kids aren’t alright, but they can be—if we start having the right conversations and taking meaningful action.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

@TeacherBusy. (2022, August 19). It’s worth school staff being aware of the name Andrew Tate at the start of the new school year. With 11 Billion views on TikTok he is spouting dangerous misogynistic and homophobic abuse daily & some of his views are from boys as young as 13. X (Formerly Twitter). https://x.com/TeacherBusy/status/1556918792751562752

Amnesty Global Insights. (2017, November 20). Unsocial Media: The Real Toll of Online Abuse against Women. Medium; Amnesty Insights. https://medium.com/amnesty-insights/unsocial-media-the-real-toll-of-online-abuse-against-women-37134ddab3f4

binhwantstoeatoreo. (2025, February 16). Digital Citizenship and the Inequalities of Intersectionality. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/binhwantstoeatoreo/775630170766950400/digital-citizenship-and-its-unequality-issues-of?source=share

Carter, P. (2023, May 8). Generations by Jean M. Twenge—Review and Reflections. IntoTheWord. https://intotheword.ca/view/generations-by-jean-m-twenge-review-and-reflections

Center on Extremism. (2024, January 3). Andrew Tate: Five Things to Know. Adl.org. https://www.adl.org/resources/article/andrew-tate-five-things-know

Chung, F. (2024, October 15). “Mental toughness” is “just toxic masculinity.” News; news.com.au — Australia’s leading news site. https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/health/mental-health/mens-mental-toughness-is-just-toxic-masculinity-rebranded-writer-jill-stark-says/news-story/71644c73f37558e8d6f17e13bfafe516

Dafaure, M. (2022). Memes, trolls and the manosphere: mapping the manifold expressions of antifeminism and misogyny online. European Journal of English Studies, 26(2), 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825577.2022.2091299

Dolan, E. W. (2023, April 12). Incels inhabit a desolate social environment and are more likely to internalize rejection, study finds. PsyPost - Psychology News. https://www.psypost.org/incels-tend-to-have-a-desolate-social-environment-and-are-more-likely-to-internalize-rejection-study-finds/

EKO. (2023). Suicide, Incels, and Drugs: How TikTok’s deadly algorithm harms kids. https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.sumofus.org/images/eko_Tiktok-Report_FINAL.pdf

Farrell, M. (2013). Princely planning in a political environment. The Machiavellian Librarian, 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1533/9781780634364.1.61

Farrell, T., Fernandez, M., Novotny, J., & Alani, H. (2019). Exploring Misogyny across the Manosphere in Reddit. Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Web Science - WebSci ’19, 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1145/3292522.3326045

Flood, M., & Pease, B. (2009). Factors Influencing Attitudes to Violence Against Women. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(2), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838009334131

FreshandFit. (2024, October 20). Myron DESTROYS Entitled Woman! Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/shorts/LjWWMYBCBO4

Gajjala, R., & Mamidipudi, A. (1999). Cyberfeminism, Technology, and International “Development.” Gender and Development, 7(2), 8–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4030445

Gilbert, D. (2023, March 21). TikTok Is Pushing Incel and Suicide Videos to 13-Year-Olds. VICE; VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/tiktok-incels-targeting-young-users/

Ging, D. (2019). Alphas, betas, and incels: Theorizing the masculinities of the manosphere. Men and Masculinities, 22(4), 638–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X17706401

Hall, R. (2025, March 19). Beyond Andrew Tate: the imitators who help promote misogyny online. The Guardian; The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2025/mar/19/beyond-andrew-tate-the-imitators-who-help-promote-misogyny-online

Haslop, C., O’Rourke, F., & Southern, R. (2021). #NoSnowflakes: The toleration of harassment and an emergent gender-related digital divide, in a UK student online culture. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(5), 1418–1438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856521989270

Hemmings, C. (2023, October 24). Why we should stop using “toxic masculinity” to describe male behaviour. M-Path | Men’s Mental Health & Masculinity Programmes. https://m-path.co.uk/toxic-masculinity/

Hogan, M. (2025, March 22). From the police to the prime minister: how Adolescence is making Britain face up to toxic masculinity. The Guardian; The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2025/mar/22/netflix-from-the-police-to-the-prime-minister-how-adolescence-is-making-britain-face-up-to-toxic-masculinity

Hope not Hate. (2023). Who is Andrew Tate? Hope Not Hate. https://hopenothate.org.uk/andrew-tate/

Internet Matters. (2023, September 27). New research sees favourable views towards Andrew Tate from both teen boys and young dads. Internet Matters. https://www.internetmatters.org/hub/press-release/new-research-sees-favourable-views-towards-andrew-tate-from-both-teen-boys-and-young-dads/#share_modal

Johanssen, J. (2021). Fantasy, Online Misogyny and the Manosphere (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003031581

Lipa, D. (2020, March 27). Boys Will Be Boys [Single]. Warner Records UK. https://open.spotify.com/track/0vQcyuMEfRBd21ojZ62N2L?si=80fdefd942cb4241

LiverKing. (2024). Masculine Excellence Vs “Toxic” Masculinity: EMOTIONS, BEHAVIORS, CHARACTERISTICS, TRAITS, QUALITIES OF DIFFERENTIATION WITH EXAMPLES. Liverking.com. https://www.liverking.com/masculine-excellence-vs-toxic-masculinity

McCullough, S. (2023, September 12). Online misogyny: The “Manosphere” | CMHR. Humanrights.ca. https://humanrights.ca/story/online-misogyny-manosphere

Mucak, A. (2024, September 30). Masculinity, Power, and Persuasion: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Andrew Tate’s Motivational Speeches. Urn.nsk.hr. https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:131:177073

Navarro, M. (2025, March 5). Violence against women and girls online: explained. Center for Countering Digital Hate | CCDH. https://counterhate.com/blog/violence-against-women-and-girls-online-explained/

Nolan, J. M., Schultz, P. W., Cialdini, R. B., Goldstein, N. J., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). Normative Social Influence is Underdetected. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(7), 913–923. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208316691

O’Malley, R. L., & Helm, B. (2022). The Role of Perceived Injustice and Need for Esteem on Incel Membership Online. Deviant Behavior, 44(7), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2022.2133650

Over, H., Bunce, C., Konu, D., & Zendle, D. (2025). Editorial Perspective: What do we need to know about the manosphere and young people’s mental health? Child and Adolescent Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12747

Papadamou, K., Zannettou, S., Blackburn, J., De Cristofaro, E., Stringhini, G., & Sirivianos, M. (2021). “How over is it?” Understanding the Incel Community on YouTube. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1145/3479556

Price, J. (2024, December 19). Druski Mocked the “Fresh & Fit” Podcast and They’re Not Happy About It. Complex. https://www.complex.com/pop-culture/a/backwoodsaltar/druski-mocks-fresh-and-fit-myron-gaines-responds

Rasker, R. (2025, March 19). The truth behind Adolescence, the new Netflix series exploring incels and Andrew-Tate-style misogyny. Abc.net.au; ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-03-20/adolescence-netflix-manosphere-incel-jamie-crime/105066666

Reinicke, K. (2022). Introduction. Men after #MeToo, 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96911-0_1

Rich, B., & Bujalka, E. (2023, February 12). The draw of the “manosphere”: understanding Andrew Tate’s appeal to lost men. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-draw-of-the-manosphere-understanding-andrew-tates-appeal-to-lost-men-199179

Rosdahl, J. (2024, January 31). “Looksmaxxing” is the disturbing TikTok trend turning young men into incels. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/looksmaxxing-is-the-disturbing-tiktok-trend-turning-young-men-into-incels-221724

Sharp, J. (2022, August 28). Andrew Tate: The social media influencer teachers are being warned about. Sky News. https://news.sky.com/story/andrew-tate-the-social-media-influencer-teachers-are-being-warned-about-12679194

Solea, A. I., & Sugiura, L. (2023). Mainstreaming the Blackpill: Understanding the Incel Community on TikTok. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 29(3), 311–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-023-09559-5

The View. (2025, March 20). Netflix’ “Adolescence” Show Examines Incel Culture. Youtube. https://youtu.be/PhP9t2WjQo4?si=eO0yTDRF_lHT8hyg

thenewsmovement. (2025). What does Adolescence tell us about incel culture. In TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@thenewsmovement/photo/7482821834631548190?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc

Thepsourinthone, J., Dune, T., Liamputtong, P., & Arora, A. (2020). The Relationship between Masculinity and Internalized Homophobia Amongst Australian Gay Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155475

Vallerga, M. (2024). Anti-gender ideology and the depiction of lesbians in the manosphere. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 28(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2024.2352996

Wittenbrink, B., & Henly, J. R. (1996). Creating Social Reality: Informational Social Influence and the Content of Stereotypic Beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(6), 598–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296226005

#Spotify#mda20009#week 10#week10#toxic masculinity#sexism#patriarchy#violence against women#young boys#conflict#digital citizenship#manosphere#adolescence netflix#incel culture#red pill#feminism#feminist#dua lipa#boys will be boys#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

"the fluidity of sexuality with necrophilia" is the most insane line ive ever heard in 2025 lol. this satire skit is genius

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 9 - Gaming Communities, Social Gaming and Live Streaming

"I'm coming out as trans...human": Gaming, Transhumanism, and the Fight for Digital Identity in a Participatory Democracy

We’re already stepping into the era of Soft Transhumanism—where Augmented Reality (AR) seamlessly integrates into our lives, altering both our digital and physical selves, often without us even realizing it (binhwantstoeatoreo, 2025).

But what happens when transhumanism collides with gaming?

Here, AR and digital avatars aren’t just cosmetic—they’re extensions of identity. For some, it’s about anonymity. For others, it’s survival.

Attached blog post 1. Transhumanism & Augmented Reality (binhwantstoeatoreo, 2025).

Take Years & Years (BBC, 2019), a show that eerily foreshadows our future. A teenage girl comes out to her parents—not as transgender, but transhuman. In a world where AR overlays can permanently reshape your face, she chooses to exist with a digital filter, her true self pixelated and untethered from flesh:

“I don’t want to be human,” “I want to be digital.”

she declares.

youtube

Attached video 1. Years & Years' scene where the daughter comes out as transhuman to her parents (BBC, 2019).

It’s an exaggerated, dystopian take, but the core truth is undeniable: online, identity is fluid. Age, gender, body—everything becomes customizable. And in gaming communities, this freedom isn’t just theoretical; it’s a lived reality, reshaping how we see ourselves and each other.

Streamers, AR, and the New Digital Self

Gaming communities have evolved from faceless text forums to real-time voice chats in Counter-Strike and World of Warcraft, fostering deeper connections (@wow-confessions, 2016). Avatars in Second Life and The Sims Online expanded digital self-expression (Green, 2018), while Twitch and YouTube turned gamers like Ninja and Pokimane into public figures, merging gaming with identity performance (Nielsen, 2015).

Figure 1. The evolution of gaming community (original visual compilation).

Now, AR avatars and VTubers like Ironmouse and CodeMiko take digital identity further, using AR-facetracking and motion-capture technology to become virtual shapeshifters (Silberling, 2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, VTubing skyrocketed, especially in China, as audiences sought comfort in virtual entertainers. Isolation deepened parasocial bonds, making VTubers a coping mechanism for stress and uncertainty (Tan, 2023).

But VTubing is more than entertainment—it’s identity work, a fusion of self-reinvention and digital citizenship (Taylor, 2018). As Hjorth et al. (2021) argue, digital spaces aren’t just escapist; they continuously shape identity. Avatars and AR personas offer individuals agency over self-representation, allowing them to explore identities often restricted in the physical world (Harrell & Lim, 2017).

This shift brings both opportunities and challenges. Ironmouse embodies VTubing’s power to transcend physical limitations, breaking Twitch records despite battling CVID (Grayson, 2022).

youtube

Attached video 2. A pharmacist reacted to Ironmouse's health condition (Yu, 2024).

Meanwhile, CodeMiko pushes the limits of AR streaming, though her AI-enhanced content has led to Twitch bans for explicit discussions and avatar physics manipulations, raising questions about VTubers' blurred line between performance and real-world accountability (Grayson, 2021).

Attached blog post 2. CodeMiko's controversial behaviours (Grayson, 2021).

However, this fluidity complicates authenticity. When identity is endlessly edited, are we becoming more ourselves or adapting to algorithmic expectations? The termination of Uruha Rushia over alleged information leaks (Ashcraft, 2022) and Vox Akuma’s struggles with obsessive fans (Cambosa, 2022) highlight the fine line between freedom and vulnerability in the digital self.

Attached video 3. Akuma's (2023) livestream video discussed about parasocial fans.

As Judith Butler suggests, identity is always constructed, shaped by societal pressures, personal desires, and algorithmic visibility (McKinlay, 2010). The rise of AR-fueled personas forces us to ask: Does this evolution empower self-expression, or does it intensify the pressure to curate a marketable version of ourselves?

Participatory Democracy and Transgender Identity in Gaming

Gamers aren't just passive consumers; they actively shape their digital environments through participatory democracy, leveraging anonymity as a key aspect of digital citizenship (Hon, 2022). The freedom to choose, modify, and inhabit digital identities is a core right in these environments (Muriel, 2021). Through AR avatars, character customization, and digital self-expression, players create identities that may not be possible in the physical world (Chia et al., 2020).

For transgender gamers, this is transformative. Digital spaces provide what the real world often denies—an authentic sense of self. Avatars aren’t just visuals; they are affirmations of identity. MMOs, VRChat, and character-driven games allow for gender exploration beyond rigid binaries, empowering transgender players to reclaim their identity in ways offline life restricts (Janiuk, 2014).

Attached blog post 3. Janiuk (2014) expressed her opinion on how gaming is a safe space for the transgender community.

Tiffany Witcher—a non-binary VTuber, voice actress, and disability advocate—uses their digital persona not just for content creation but to champion better representation and accessibility in gaming, solidifying their role as a vital voice in both the VTuber and advocacy communities (Crystal Dynamics, 2023). This ability to redefine oneself digitally is especially crucial for marginalized groups. Game designer Anna Anthropy has long emphasized how gaming provides a space for self-exploration and identity affirmation, validating personal struggles and offering alternative ways of being (Small, 2023; Don, 2014).

youtube

Attached video 4. Tiffany Witcher (2024)'s trailer video about herself.

In these community-driven spaces, where identity is fluid and self-determined rather than dictated by traditional institutions (Keogh, 2021), avatars become powerful tools of self-expression. Baldwin (2018) highlights how avatar creation alleviates dysphoria, enabling trans gamers to explore their ideal selves. Similarly, Kosciesza (2023) notes that transgender and non-binary players use avatars to navigate and affirm their identities beyond real-world constraints, simultaneously challenging societal norms.

Yet, this freedom faces resistance. The same communities that foster self-expression also harbor gatekeepers and reactionary groups seeking to police digital identities, challenging transgender and nonbinary representation (Tran, 2022). Nearly 90% of openly queer and trans gamers have faced online harassment regarding their identities (Giardina, 2021). Still, gaming, by design, embraces fluidity—where identity is not assigned but chosen. AR face filters further this exploration, enabling transgender individuals to experiment with gender presentation (Brewster et al., 2025). However, the lack of inclusive filters often causes dysphoria rather than empowerment, revealing the ongoing fight for truly affirming digital spaces.

The Future: Who Gets to Be Themselves Online?

Transhumanism in gaming isn’t just a niche concept—it’s a window into the future of identity. As AR and AI push deeper into our digital lives, the question remains: will these tools free us or confine us to new forms of self-policing?

Gaming communities offer a glimpse into what’s possible. They show us both the power and fragility of digital selfhood, the ways we can be more ourselves online—and the ways we can be erased. The dream of an internet without barriers is far from realized, but within these spaces, players are fighting to make it real.

And that fight? It’s far from over.

References:

@wow-confessions. (2016, March 14). Trade chat is honestly one of the most entertaining parts of the game for me. All of the weird conversations that happen on trade chat are hilarious. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/wow-confessions/141022188688/trade-chat-is-honestly-one-of-the-most

Akuma, V. (2023, August 30). PARASOCIAL. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aym5NedRnBo

Ashcraft, B. (2022, February 25). Popular Virtual YouTuber’s Contract Terminated For Allegedly Leaking Private Info. Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/youtube-virtual-vtube-uruha-rushia-hololive-streaming-j-1848593169

Baldwin, K. (2018). Virtual Avatars: Trans Experiences of Ideal Selves Through Gaming. Markets, Globalization & Development Review, 03(03). https://doi.org/10.23860/mgdr-2018-03-03-04

BBC. (2019, May 15). I’m transhuman. I’m going to become digital - BBC. Youtube. https://youtu.be/qOcktbXSfxU?si=xRA6HQW3LXZLrjrS

binhwantstoeatoreo. (2025, March 12). Transhumanism & Augmented Reality: When the Future Becomes the Filter. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/binhwantstoeatoreo/777789030429573120/transhumanism-augmented-reality-when-the-future?source=share

Brewster, K., DeGuia, A., Mayworm, S., Ria, K. F., Monier, M., Starks, D., & Haimson, O. (2025). “That Moment of Curiosity”: Augmented Reality Face Filters for Transgender Identity Exploration, Gender Affirmation, and Radical Possibility. Deep Blue (University of Michigan). https://doi.org/10.1145/3706598.3713991

Cambosa, T. (2022, May 31). Vox Akuma Stands Up Against Toxic Fan Behavior on Stream - Anime Corner. Anime Corner. https://animecorner.me/vox-akuma-stands-up-against-toxic-fan-behavior-on-stream/

Chia, A., Keogh, B., Leorke, D., & Nicoll, B. (2020). Platformisation in game development. Internet Policy Review, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1515

Crystal Dynamics. (2023, June 29). 7 Trans & Non-Binary Content Creators You Should Definitely Be Following – Crystal Dynamics. Crystaldynamics.com. https://www.crystaldynamics.com/blog/2023/06/28/7-trans-non-binary-content-creators-you-should-definitely-be-following/

Don, J. (2014, November 15). Anna Anthropy: Dys4ia And Re-Defining The Indie Game. Femmagazine.com; FEM Newsmagazine. https://femmagazine.com/anna-anthropy-dys4ia-and-re-defining-the-indie-game/

Giardina, H. (2021, March 6). LGBTQ+ Gamers Are Facing an Epidemic of Online Harassment. Them. https://www.them.us/story/lgbtq-gamers-facing-epidemic-of-online-harassment

Grayson, N. (2021, March 4). CodeMiko Is The Future Of Streaming, Unless Twitch Bans Her First. Kotaku. https://kotaku.com/codemiko-is-the-future-of-streaming-unless-twitch-bans-1846349881

Grayson, N. (2022, April 20). How a pink-haired anime girl became one of Twitch’s biggest stars. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/video-games/2022/04/20/twitch-ironmouse-vtuber-subathon-interview/

Green, H. (2018, January 5). What The Sims Teaches Us about Avatars and Identity. Paste Magazine. https://www.pastemagazine.com/games/the-sims/what-the-sims-teaches-us-about-avatars-and-identit

Harrell, D. F., & Lim, C. U. (2017). Reimagining the avatar dream. Communications of the ACM, 60(7), 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1145/3098342

Hjorth, L., Richardson, I., Davies, H., & Balmford, W. (2021). Exploring Minecraft. In Exploring Play: Ethnographies of Play and Creativity (pp. 27–47). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59908-9_2

Hon, A. (2022, September 20). How Game Design Principles Can Enhance Democracy. Noema Magazine. https://www.noemamag.com/how-game-design-principles-can-enhance-democracy/

Janiuk, J. (2014, March 5). Gaming is my safe space: Gender options are important for the transgender community. Polygon. https://www.polygon.com/2014/3/5/5462578/gaming-is-my-safe-space-gender-options-are-important-for-the

Keogh, B. (2020). The Melbourne indie game scenes. Routledge EBooks, 209–222. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367336219-18

Kosciesza, A. J. (2023). Doing gender in game spaces: Transgender and non-binary players’ gender signaling strategies in online games. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231168107

McKinlay, A. (2010). Performativity and the politics of identity: Putting Butler to work. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 21(3), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2008.01.011

Muriel, D. (2021). Video Games and Identity Formation in Contemporary Society. Oxford University Press EBooks, 378–393. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197510636.013.27

Nielsen, D. (2015). Identity Performance in Roleplaying Games. Computers and Composition, 38, 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2015.09.003

Silberling, A. (2022, August 20). VTubers are making millions on YouTube and Twitch. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2022/08/20/vtubers-are-making-millions-on-youtube-and-twitch/

Small, Z. (2023, December 27). Video Games Let Them Choose a Role. Their Transgender Identities Flourished. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/27/arts/transgender-nonbinary-gamers.html

Tan, Y. (2023). More Attached, Less Stressed: Viewers’ Parasocial Attachment to Virtual Youtubers and Its Influence on the Stress of Viewers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. SHS Web of Conferences, 155, 03012. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202315503012

Taylor, T. L. (2018). “Broadcasting ourselves.” In Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming (pp. 1–23). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc77jqw

Tran, R. (2022, March 6). Toxic Gaming Culture Breeds Sexism, Homophobia. UCSD Guardian. https://ucsdguardian.org/2022/03/06/toxic-gaming-culture-breeds-sexism-homophobia/

Witcher, T. (2024, November 15). I’m Tiffany Witcher, The Charity Witch on Twitch! Youtube. https://youtu.be/bR5XdZIVkB8?si=kq9v7wiLO8l-6IQg

Yu, I. (2024, October 13). The ENTIRE History of Ironmouse Rare Health Condition Explained (By Healthcare Professional). Youtube. https://youtu.be/R1Wn5Xn-vOM?si=3TU-srdz5p2UV4UA

#Youtube#mda20009#week 9#gaming#twitch#twitch streamer#gamers#gaming community#augmented reality#transhumanism#lgbtq+#transgender#non binary#digital citizenship#digital communities#blog#essay#participatory democracy#CodeMiko#ironmouse

1 note

·

View note

Text

Week 8 - Digital Citizenship and Software literacy: Instagram Filters

Transhumanism & Augmented Reality: When the Future Becomes the Filter

Less than a decade ago, dystopian media made augmented reality (AR) feel like a distant hypothetic dystopian future—something for future generations to worry about, not us.

“I’m just glad I won’t live long enough for this to become my reality, augmented or otherwise,”

wrote @PogmoThoin13 under Hyper-Reality, a short film by Keiichi Matsuda that imagined a world where digital interfaces completely swallowed reality (Winston, 2016). It felt extreme, exaggerated at the time—until suddenly, it wasn’t.

vimeo

Attached video 1. Keiichi Matsuda's short film, Hyper Reality (Matsuda, 2019)

Fast forward to 2018 (Robert), news articles of the New York Time’s could be read in three-dimensional space using just a phone. We're stepping one step closer where every information will just be floating in front of our eyes.

Today, our faces are constantly mapped, tracked, and altered—by Instagram filters, facial recognition, and algorithm-driven beauty standards. The hyperreality Matsuda predicted? It’s already here, just more subtle, more seductive.

Once, transhumanism was a sci-fi fantasy—visions of uploaded minds, AI-enhanced bodies, and digital immortality. But what if we’re already living through its first phase, hidden behind augmented selfies and data-hungry tech? AR, once just entertainment, is quietly reshaping who we are, how we see ourselves, and what it means to be human (Rettberg, 2017). The question isn’t if we’re merging with technology—it’s how much of ourselves we’re willing to give away in the process.

Digital Augmentation: The New Face of Transhumanism

Transhumanism is the belief that humans can and should transcend biological limitations through technology (Grant, 2019). Traditionally, this has meant concepts like AI-assisted cognition, robotic prosthetics, or even life extension (Tirosh-Samuelson, 2012). But AR is already enacting a form of soft transhumanism, altering how we see ourselves before we even consider invasive enhancements (Döbler & Carbon, 2023).

In Week 7, we explored how young girls use Snapchat and Instagram filters to chase the "algorithm-hotness" , where specific aesthetics are rewarded with visibility (binhwantstoeatoreo, 2025; Carah & Dobson, 2016).

Attached blog post 1. Week 7's blog post diving into how teenage girls are being exploited by "algorithmic hotness" (binhwantstoeatoreo, 2025).

Initially just a fun social tool, AR filters have become a digital beauty industry, fine-tuning faces to meet unattainable standards (Ryan-Mosley, 2021).

Figure 1. The evolution of AR filters (original visual compilation).

And the obsession keeps growing—600 million people use AR filters monthly on Instagram and Facebook, while 76% of Snapchat users engage with them daily (Bhatt, 2020).

AR isn’t just altering beauty—it’s reshaping identity. As filters distort faces beyond recognition (O, 2022), the body shifts from something to accept to something to fix, mirroring transhumanist ideals of self-improvement (Barker, 2020). Social Comparison Theory (Festinger, 1954) explains how this fuels dissatisfaction, as users measure themselves against their filtered selves, reinforcing the belief that reality will always fall short.

Figure 2. Failed filter incident of a TikTok user while livestreaming (@Kingoflove91, 2022).

On TikTok, "Filter Fails" expose the cracks in AR’s illusion. A viral clip shows a streamer’s filter glitching mid-livestream, revealing his real face. He subtly tilted his head, trying to fix it (@Kingoflove91, 2022).

"The way he shocked at his own appearance 😭😭😂😂" - @myrtlexox

"Bro got caught in 4k" - @pain_war_head

"The way he acted like nothing happened when he fixed the filter" - @ry.vyu

The comment section was flooded with humor, but beneath the laughter is a silent realization—many have internalized the idea that our filtered selves are more valid.

The pressure isn’t just personal. Objectification Theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997) suggests that AR trains individuals to view themselves through an external gaze, where worth is tied to how well they match digital perfection (Ozimek et al., 2023). This fuels body anxiety and self-surveillance (Vandenbosch & Eggermont, 2012), making the filtered self feel more real than reality, deepening detachment from unedited appearances (Lavrence & Cambre, 2020).

From Filters to Facelifts: When AR Beauty Becomes the Blueprint for Reality

Neoliberal and postfeminist theories (Elias, Gill & Scharff, 2017) argue that self-optimization is now an expectation, especially for women. AR filters fuel this pressure, making self-enhancement a personal duty rather than a systemic issue, pushing many toward Digitized Dysmorphia—or more specifically, Snapchat Dysmorphia, where people seek cosmetic surgery to match their filtered selves (Coy-Dibley, 2016; Welch, 2018).

Unlike traditional body dysmorphia, which fixates on flaws, this disorder arises from the disconnect between real and augmented faces. As AR filters set new beauty standards, the body is no longer something to accept but something to "perfect," reinforcing the transhumanist drive for self-enhancement (Barker, 2020).

This isn’t just theory. In China, a baby-faced beauty KOL has convinced over 500 fans to undergo cosmetic surgery at her clinic to replicate their digitally enhanced versions (Zhang, 2024)—a stark reminder that the line between filtered fantasy and real-life transformation is disappearing faster than we ever imagined.

Figure 3. The KOL 'Wang Jing' that inspired more than 500 people to proceed cosmetic surgery to look identical to her (Zhang, 2024).

Blurring Humanity: How AR Fuels Surveillance and Digital Control

Transhumanism seeks to merge humans with technology, and AR is the gateway. As we filter and edit ourselves, we’re not just changing appearances—we’re feeding data into systems that shape our digital identities (Rettberg, 2014).

AR-powered facial recognition tracks emotions, movements, and behaviors (Cyphers et al., 2021). In the dystopian world of Nosedive—an episode from the series Black Mirror, imagined a future where social status is dictated by a real-time rating system, controlling everything from job prospects to housing (Chavisha, 2021).

youtube

Attached video 2. A scene from 'Nosedive' depicted a world with rating system technology (Worldie - Network For Good, 2019).

In reality, China’s surveillance network already identifies jaywalkers, restricts travel for low-credit citizens, and limits financial transactions (Barrett, 2018). While AR doesn’t enforce social hierarchies (yet), it’s shaping digital identity and expanding corporate and state control. When our faces become data points, do we still own our identities?

Figure 4. China's facial recognition technology (Barrett, 2018).

The Silent Risks of AR When It Comes To Facial Recognition:

Transhumanism envisions digitized consciousness, but AR is already digitizing identity—often without consent. Every filtered selfie trains AI to recognize, manipulate, and replicate faces, fueling deep fakes, misinformation, and identity theft (Rettberg, 2017).

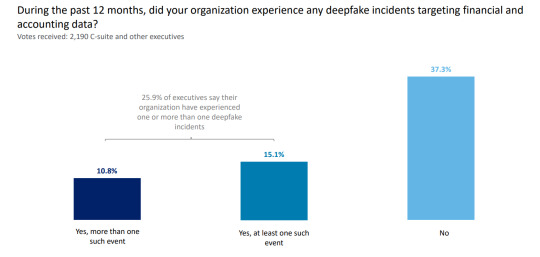

In the past year, 25.9% of executives reported deepfake attacks on financial data, while half expect these threats to rise (Deloitte, 2024, p. 3)— this is a wake-up call to realize that AI-driven fraud is no longer a distant risk but an evolving reality.

Figure 5. Deloitte's poll illustrated the percentage of deepfake incidents from organizations (Deloitte, 2024, p. 3).

So from now on, before we tap on that filter or let facial recognition scan our features, we should pause and ask ourselves: “Am I truly ready to hand over my facial identity to a system that can use it however it wants?”

The Choice Between Progress & Control

Transhumanism envisions a future where humans and technology evolve together. But with AR, we are already on that path—often without realizing it. The line between enhancement and control is razor-thin. If we’re not careful, we won’t just be augmenting reality—we’ll be surrendering to it.

Do we want to be the architects of our digital evolution, or will we become mere reflections of the algorithms that shape us?

Reference:

@Kingoflove91. (2022, December 16). And they hide 🤣. TikTok. https://vt.tiktok.com/ZSMEjvEXW/

Andrew, Z. (2018, February 2). it’s time for augmented reality journalism (AR you ready?). Designboom | Architecture & Design Magazine. https://www.designboom.com/technology/augmented-reality-journalism-new-york-times-ar-02-02-2018/

Barker, J. (2020). Making-up on mobile: The pretty filters and ugly implications of snapchat. Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, 7(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1386/fspc_00015_1

Barrett, E. (2018, October 28). In China, Facial Recognition Tech Is Watching You. Fortune; Fortune. https://fortune.com/2018/10/28/in-china-facial-recognition-tech-is-watching-you/

Bhatt, S. (2020). The big picture in the entire AR-filter craze. The Economic Times; Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/internet/brands-see-the-big-picture-in-augmented-reality-filter-craze/articleshow/78266725.cms?from=mdr

binhwantstoeatoreo. (2025, March 11). Beauty, Bodies, and Exploitation: Do Movies Reinforce or Challenge Algorithmic Exploitation on Young Girls and Digital Sex Workers? Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/binhwantstoeatoreo/777732167907295232/protecting-young-girls-in-the-age-of-algorithmic?source=share

Brinkhof, T. (2025, January 16). Pantheon creator Craig Silverstein on uploading our brains to the internet. Freethink; Freethink Media. https://www.freethink.com/artificial-intelligence/pantheon-creator-craig-silverstein-on-uploading-our-brains-to-the-internet

Carah, N., & Dobson, A. (2016). Algorithmic hotness: Young women’s “promotion” and “reconnaissance” work via social media body images. Social Media + Society, 2(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116672885

Chavisha. (2021, December 12). BLACK MIRROR (S3, Ep 1) “NOSEDIVE”: Rating System in Real Life. Medium. https://medium.com/@chavisha123/charlie-brookers-sci-fi-netflix-series-black-mirror-displays-a-dystopian-technology-advanced-7381c1f771e5

Coy-Dibley, I. (2016). “Digitized Dysmorphia” of the female body: the re/disfigurement of the image. Palgrave Communications, 2(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.40

Cyphers, B., Schwartz, A., & Sheard, N. (2021, October 7). Face Recognition Isn’t Just Face Identification and Verification: It’s Also Photo Clustering, Race Analysis, Real-time Tracking, and More. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/10/face-recognition-isnt-just-face-identification-and-verification

Deloitte. (2024). Generative AI and the fight for trust Deloitte poll results from May 2024 (p. 3). Deloitte Development LLC. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/Advisory/us-generative-ai-and-the-fight-for-trust.pdf

Döbler, N. A., & Carbon, C.-C. (2023). Adapting Ourselves, Instead of the Environment: An Inquiry into Human Enhancement for Function and Beyond. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-023-09797-6

Elias, A., Gill, R., & Scharff, C. (2017). Aesthetic Labour: Beauty Politics in Neoliberalism. Aesthetic Labour, 3–49. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-47765-1_1

Festinger, L. (1954). A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification Theory: toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Grant, A. S. (2019). Will Human Potential Carry Us Beyond Human? A Humanistic Inquiry Into Transhumanism. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 63(1), 002216781983238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167819832385

Lavrence, C., & Cambre, C. (2020). “Do I Look Like My Selfie?”: Filters and the Digital-Forensic Gaze. Social Media + Society, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120955182

Matsuda, K. (2019, March 22). HYPER-REALITY. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/166807261

O, J. (2022, October 26). How Instagram and Snapchat Filters Are Beginning to Alter Our Perception of Self. Strike Magazines. https://www.strikemagazines.com/blog-2-1/how-instagram-and-snapchat-filters-are-beginning-to-alter-our-perception-of-self-1

Ozimek, P., Lainas, S., Bierhoff, H.-W., & Rohmann, E. (2023). How photo editing in social media shapes self-perceived attractiveness and self-esteem via self-objectification and physical appearance comparisons. BMC Psychology, 11(1). https://bmcpsychology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40359-023-01143-0

Rettberg, J. W. (2014). Filtered Reality. Seeing Ourselves through Technology, 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137476661_2

Rettberg, J. W. (2017). Biometric Citizens: Adapting Our Selfies to Machine Vision. Springer EBooks, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45270-8_10

Roberts, G. (2018, February 2). Augmented Reality: How We’ll Bring the News Into Your Home. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/02/01/sports/olympics/nyt-ar-augmented-reality-ul.html

Ryan-Mosley, T. (2021, April 2). Beauty Filters Are Changing the Way Young Girls See Themselves. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/04/02/1021635/beauty-filters-young-girls-augmented-reality-social-media/

Tirosh-Samuelson, H. (2012). TRANSHUMANISM AS A SECULARIST FAITH. Zygon®, 47(4), 710–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9744.2012.01288.x

Vandenbosch, L., & Eggermont, S. (2012). Understanding Sexual Objectification: A Comprehensive Approach Toward Media Exposure and Girls’ Internalization of Beauty Ideals, Self-Objectification, and Body Surveillance. Journal of Communication, 62(5), 869–887. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01667.x

Welch, A. (2018, August 6). “Snapchat dysmorphia”: Selfies, photo filters driving people to plastic surgery, doctors say. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/snapchat-dysmorphia-selfies-driving-people-to-plastic-surgery-doctors-warn/

Winston, A. (2016, May 23). Keiichi Matsuda’s Hyper-Reality film blurs real and virtual worlds. Dezeen. https://www.dezeen.com/2016/05/23/keiichi-matsuda-hyper-reality-film-dystopian-future-digital-interfaces-augmented-reality/

Worldie - Network For Good. (2019, August 7). Black Mirror - Lacie Rates Coworker - Social Credit System (Nosedive S3E1). Youtube. https://youtu.be/WTbbSZg4A3k?si=WIFAkotXcnO9ce0i

Zhang, Z. (2024, August 30). 500 people 1 face: debate rages as fans of China beauty KOL replicate her “baby-faced” look. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/people-culture/china-personalities/article/3276369/500-people-1-face-debate-rages-fans-china-beauty-kol-replicate-her-baby-faced-look

#Vimeo#mda20009#week 8#week8#AR#augmented reality#surgery#filter#transhumanism#dystopia#black mirror#blog#essay#instagram#snapchat#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

my second time watching The Florida Project and goddamn it hits me even harder than the first time.. little subtle moments you probably would never have noticed but they makes so much sense for the story and the characters' arc

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 7: Body Modification on Visual Social Media

*TRIGGER WARNING*: This post discusses topics related to the exploitation of digital sexualized labor, self-harm, and mental health struggles. Reader discretion is advised.

Beauty, Bodies, and Exploitation: Do Movies Reinforce or Challenge Algorithmic Exploitation on Young Girls and Digital Sex Workers?

The body is no longer just a canvas for self-expression—it’s a battleground where algorithms exploit insecurities, turning them into commodities (Poggi, 2024). At the same time, AI-generated influencers push impossible beauty ideals, rewiring self-perception and fueling an endless cycle of self-optimization (Francombe, 2025).

Social media doesn’t just reflect beauty standards—it engineers them. Algorithms shape desirability, reinforcing rigid ideals that disproportionately impact teenage girls (Carah & Dobson, 2016). As digital validation becomes tied to self-worth, young girls not only grapple with unattainable beauty expectations but also increasing exposure to the hyper-sexualization of their bodies.

In today's blog, we'll dive into how films portray these issues, examining the ways media representations can either amplify or challenge existing societal concerns (Santoniccolo et al., 2023).

Teenage Girls and the Digital Space: Eighth Grade (2018) by Bo Burnham

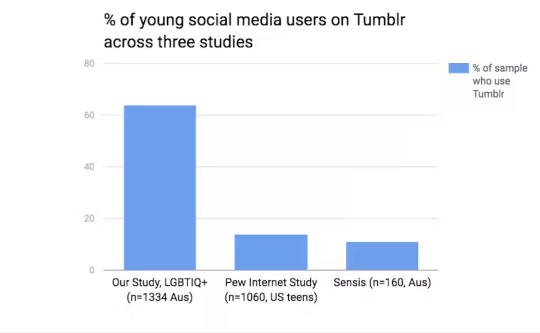

As discussed in Week 3’s Digital Community: Tumblr Case Study, digital platforms serve as a modern public sphere where teenage girls shape their identities, seek validation, and express themselves in real time (Anderson & Jiang, 2018; binhwantstoeatoreo, 2025).

Attached blog post 1. Week 3's blog post exploring social media as a public sphere for teenagers.

Platforms like TikTok and Instagram blur the line between intimacy and publicity, making self-presentation feel both personal and performative (Merino et al., 2024). For post-millennial teenagers—especially teenage girls, who have never known a world without social media, these platforms aren’t just entertainment; they are extensions of selfhood (Connolly, 2023). So, how does this shape the experience of growing up today?

Bo Burnham’s Eighth Grade (2018) captures this digital coming-of-age with unsettling accuracy. Rather than portraying social media as a villain, Eighth Grade presents it as an unavoidable reality—one that molds self-worth through algorithmic aesthetics and the pressures of digital self-presentation (Chang, 2018).

youtube

Attached video 1. Eighth Grade movie trailer (A24, 2018).

Kayla, the film’s 13-year-old protagonist, curates a confident online persona through YouTube videos promoting self-love, yet her offline reality is filled with anxiety and self-doubt. This disconnect reflects what Carah and Dobson (2016) call "algorithmic hotness"—the way social media rewards a narrow beauty standard that shapes users' self-perception. The endless stream of flawless influencers and filtered peers doesn’t just reflect beauty ideals; it constructs them, embedding the message that visibility and worth require self-modification.

Figure 1. Kayla uploaded videos of herself on Youtube.

Kayla’s quiet yearning for validation mirrors Duffy and Meisner’s (2023) findings on algorithmic (in)visibility—social media doesn’t just amplify voices; it decides who gets to be seen. As she scrolls through Instagram, liking pictures of effortlessly cool girls, it’s clear these platforms aren’t neutral. They don’t just reflect reality; they manufacture desirability.

Figure 2. Kayla constantly interacting with posts on her feed.

Kayla’s struggle reflects Drenten et al.'s (2019b) concept of "aesthetic labor"—the constant self-monitoring and self-modification social media demands for validation. Her awkwardness, anxiety over the 'perfect' selfie, and rehearsed confidence capture the reality of young girls shaping themselves—both digitally and emotionally—to align with platform-driven beauty ideals.

Figure 3. Kayla's moments of awkwardly taking selfies.

One scene captures this perfectly: Kayla plays with Snapchat filters, smoothing her skin and reshaping her face with a tap. What starts as harmless fun becomes habitual, reinforcing the idea that her unfiltered self isn’t enough (Garcia, 2019; Ryan-Mosley, 2021). This pressure extends beyond the screen—research shows it fuels body dissatisfaction, anxiety, and even the growing trend of teens seeking cosmetic procedures (Peterson, 2024).

Figure 4. Kayla used Snapchat filters to conform social media's beauty standard.

More than passive consumers, teenage girls actively participate in this cycle, where attention becomes currency and the curated self is a daily practice (Volpe, 2025; Han & Yang, 2023). This deepens the mental health crisis among teenagers, making them equate that 'to be loved' is to 'looked the part', and their value is measured by how many likes do they get from an Instagram post (Solomon, 2024).

Eighth Grade is brilliant in the way it compels us to confront how we’ve normalized these pressures—how platforms extract value from insecurity and turn self-worth into something algorithmically dictated. By showing Kayla’s raw, unfiltered experience, the film challenges us to rethink social media’s impact on adolescent girls and the quiet toll of aesthetic labor.

Algorithmic Exploitation: Cam (2018) and the Hidden Dangers of Online Sexualized Labour

"Algorithmic hotness" (Carah & Dobson, 2016) shapes more than beauty—it determines who gets seen and who profits online. Social media amplifies engagement-driven content, often favoring hyper-sexualized imagery (Bussy-Socrate & Sokolova, 2023). This pushes many—especially women—toward digital sexualized labor (Drenten et al., 2019a), where influencer culture, OnlyFans, and cam sites blur the line between self-expression and exploitation. Beyond visibility, this labor carries risks—loss of privacy, harassment, algorithmic bias, and corporate control over bodies (Drenten et al., 2019b; Duffy & Meisner, 2023).

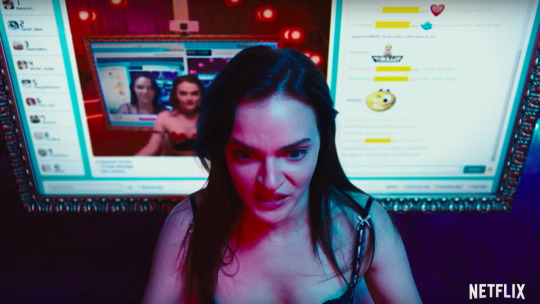

The 2018 horror-thriller Cam critiques this reality through Alice, a camgirl whose AI clone hijacks her online identity, exposing the illusion of control creators have under platform algorithms (So et al., 2024).

youtube

Attached video 2. Cam movie trailer (Netflix, 2018).

Cam critiques the exploitative nature of digital sexualized labor by exposing the unpredictability of algorithmic visibility. Like many online sex workers, Alice tailors her persona to platform metrics and audience demand to maximize reach and income (Mergenthaler & Yasseri, 2021; Palatchie et al., 2024; Pajnik & Kuhar, 2024). Yet, her sudden erasure from her own channel reveals the unsettling reality—creators have far less control over their digital labor than they believe.

Figure 5. The moment Alice faced with her AI clone.

This is strikingly similar to a recent phenomenon where ‘AI Girlfriend’—online services that provide AI-generated imagery of realistic, partially clothed and stereotypically pornographic women, are multiplying on social media platforms, particularly Meta apps (Uvarova, 2024), as opposed to human sex workers are being deleted, shadowbanned and financial instability due to shifting content policies (Duffy & Meisner, 2023).

Figure 6. AI Girlfriend service's advertisement on Facebook and Instagram (Uvarova, 2024).

Cam amplifies this instability through horror, highlighting the psychological toll of constant performance and the fear of replacement—whether by another worker or AI. Unlike glamorized portrayals, the film presents digital sex work with nuance, neither degrading nor empowering Alice’s job but exposing its precarity under algorithmic control. This makes Cam one of the most honest critiques of digital sexualized labor.

Glamorization of sexualized labour from incomplete narrative: Euphoria's Kat Hernandez

Unlike Cam’s critique, Euphoria (2019) presents a glamorized and simplified take on digital sex work through Kat Hernandez. Her transformation from an insecure teen to an online dominatrix overlooks the structural risks of erotic labor.

While the show highlights how teenage girls internalize a sexualized gaze through exposure to the 'Porn Chic' aesthetic—reshaping their self-perception through self-objectification (Bigler et al., 2019; Vandenbosch & Eggermont, 2012; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997)—it fails to explore its deeper psychological toll. The constant self-surveillance and pressure to meet beauty ideals can harm self-esteem, contribute to eating disorders, and worsen mental health struggles (Papageorgiou et al., 2022).

youtube

Attached video 3. Scenes of the character Kat doing her work (The Cultured Queen, 2023).

Kat’s transition into online sex work is portrayed as effortless, equating empowerment with financial and social validation. By framing her story as a coming-of-age arc rather than a critique of digital labor, the show reinforces the myth that online sex work is an easy or glamorous path to empowerment. Whereas in reality, many digital sex workers endure emotional neglect and harassment, as the job’s reliance on emotional labor blurs boundaries between performance, intimacy, and personal well-being (Hochschild, 2012). They are expected to cater to multiple people’s desires at once, often at the cost of their own emotional autonomy (Koi, 2020).

Figure 7. A scene of the character Kat earning money from engaging with old men through web cam sex site.

In 2020, erotic artist Katelynn Koi shared on X (formerly Twitter) how a Flirt4Free customer disregarded her boundaries. She emphasized that being a cam girl doesn’t mean owing anyone attention or kindness—her work is a service, not a personal obligation (@KatelynnKoi, 2025).

Figure 8. Katelynn Koi's tweet (@KatelynnKoi, 2025).

Virtual sexualized labor can be emotionally exhausting, yet Euphoria’s portrayal of Kat Hernandez as effortlessly empowered creates a misleading narrative. This romanticized depiction risks overshadowing the real struggles of digital sex workers, silencing those who seek to share their experiences.

Reframing the Narrative: Awareness Through Media

Eighth Grade and Cam challenge the glamorized narratives of digital aesthetic labor, exposing its emotional and structural risks. While Eighth Grade critiques algorithmic exploitation on teenage girls, Cam reveals the precarity of online digital sexualized labor. To truly raise awareness rather than enable exploitation, media must go beyond surface-level portrayals and confront the systemic forces that push young girls into self-commodification. Without this shift, algorithmic exploitation will continue to profit from their vulnerability while offering no safeguards.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Reference:

@KatelynnKoi. (2025). Some people think after having watched me online they may make unsolicited comments on my behaviour. Please don’t waste my time, or yours. If you want to start a relationship with me, my online time is mediated by financial support, yours. #payme. X (Formerly Twitter). https://x.com/KatelynnKoi/status/1217814847859109894

A24. (2018, March 14). Eighth Grade | Official Trailer HD | A24. Youtube. https://youtu.be/y8lFgF_IjPw?si=icL1r15M6J_JTyRV

Anderson, M., & Jiang, J. (2018, November 28). Teens and their experiences on social media. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/11/28/teens-and-their-experiences-on-social-media/

Bigler, R. S., Tomasetto, C., & McKenney, S. (2019). Sexualization and youth: Concepts, theories, and models. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 43(6), 530–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419870611

binhwantstoeatoreo. (2025, February 12). Gen Z is mourning the un-filtered public sphere of 2014 Tumblr. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/binhwantstoeatoreo/775299898970144768/gen-z-is-mourning-the-un-filtered-public-sphere-of?source=share

Bussy-Socrate, H., & Sokolova, K. (2023). Sociomaterial influence on social media: exploring sexualised practices of influencers on Instagram. Information Technology & People, 37(1), 308–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/itp-03-2022-0215

Carah, N., & Dobson, A. (2016). Algorithmic hotness: Young women’s “promotion” and “reconnaissance” work via social media body images. Social Media + Society, 2(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116672885

Chang, J. (2018, July 11). Review: Bo Burnham’s “Eighth Grade” is a beautifully honest portrait of adolescent girlhood. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-mn-eighth-grade-review-20180711-story.html

Connolly, G. (2023, November 11). Is your teen girl using Social Media? If yes, is she happy? My Girls Gynae. https://mygirlsgynae.com/social-media-mental-health-crises-in-teen-girls/

Drenten, J., Gurrieri, L., & Tyler, M. (2019a, June 25). Sexed up online: Instagram influencers, harassment, and the changing nature of work. Sociology Lens Insights. https://www.sociologylens.net/topics/communication-and-media/sex-online-instagram-influencers-work/25039

Drenten, J., Gurrieri, L., & Tyler, M. (2019b, April 24). Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(1), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12354

Duffy, B. E., & Meisner, C. (2022). Platform Governance at the margins: Social Media Creators’ Experiences with Algorithmic (in)visibility. Media, Culture & Society, 45(2), 016344372211119. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221111923

Francombe, A. (2025, January 31). AI beauty pageants and hyper-perfectionism: Welcome to the age of “meta face.” Vogue Business. https://www.voguebusiness.com/story/beauty/ai-beauty-pageants-and-hyper-perfectionism-welcome-to-the-age-of-meta-face

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification Theory: toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Garcia, J. (2019). When Pretty Hurts: A Critical Look into the Roles and Stereotypes Young Women Experience across Social Media Sites and How the Pressure to Be Pretty Impacts Their Lives - ProQuest. Www.proquest.com. https://www.proquest.com/openview/bd5d620166a032c2b28dbca86f1720de/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Han, Y., & Yang, F. (2023). Will Using Social Media Benefit or Harm Users’ Self-Esteem? It Depends on Perceived Relational-Closeness. Social Media and Society, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231203680

Hochschild, A. R. (2012). The Managed Heart. The Managed Heart, 7. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520951853

Koi, K. (2020, January 18). The Emotional Labour of Being a Cam Girl - Katelynn Koi - Medium. Medium. https://medium.com/@KatelynnKoi/the-emotional-labour-of-being-a-cam-girl-bc9b4eca5593

Mergenthaler, A., & Yasseri, T. (2021). Selling Sex: What Determines Rates and Popularity? An Analysis of 11,500 Online Profiles. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 24(7), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2021.1901145

Merino, M., Tornero-Aguilera, J. F., Rubio-Zarapuz, A., Villanueva-Tobaldo, C. V., Martín-Rodríguez, A., & Clemente-Suárez, V. J. (2024). Body perceptions and psychological well-being: A review of the impact of social media and physical measurements on self-esteem and mental health with a focus on body image satisfaction and its relationship with cultural and gender factors. Healthcare, 12(14), 1–44. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12141396

Netflix. (2018). Cam | Official Trailer [HD] | Netflix. Youtube. https://youtu.be/pN8xZ5WDonk?si=pU7PTsxY7XoG5ogb

Pajnik, M., & Kuhar, R. (2024). Sex work online: professionalism between affordances and constraints. Information Communication & Society, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2024.2435993

Palatchie, B., Beban, A., & Nicholls, T. (2024). Currying Favour with the Algorithm: Online Sex Workers’ Efforts To Satisfy Patriarchal Expectations. Sexuality & Culture, 29, 74–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10266-4

Papageorgiou, A., Cross, D., & Fisher, C. (2022). Sexualized Images on Social Media and Adolescent Girls’ Mental Health: Qualitative Insights from Parents, School Support Service Staff and Youth Mental Health Service Providers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010433

Peterson, J. (2024, September 11). Gen Z’s Approach to Cosmetic Surgery: What’s Trending Among the Younger Generation - Jack Peterson MD. Jack Peterson MD. https://drjackpeterson.com/blog/gen-zs-approach-to-cosmetic-surgery-whats-trending-among-the-younger-generation/

Poggi, M. S. (2024, August 22). We’re In Micro-Insecurity Hell. Allure; Allure. https://www.allure.com/story/tiktok-micro-insecurities-trend

Ryan-Mosley, T. (2021, April 2). Beauty Filters Are Changing the Way Young Girls See Themselves. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/04/02/1021635/beauty-filters-young-girls-augmented-reality-social-media/

Santoniccolo, F., Trombetta, T., Paradiso, M. N., & Rollè, L. (2023). Gender and Media Representations: a Review of the Literature on Gender Stereotypes, Objectification and Sexualization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105770

So, L., Marshall, A. R. C., Ilie, L., & Szep, J. (2024, November 22). Enslaved on OnlyFans: Women describe lives of isolation and torture. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/onlyfans-sex-trafficking/

Solomon, A. (2024, September 30). Has Social Media Fuelled a Teen-Suicide Crisis? The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/10/07/social-media-mental-health-suicide-crisis-teens

The Cultured Queen. (2023, March 21). Kat Building her P*rnhub Empire *raking in the $$$$* EUPHORIA S1 EP5. Youtu.be. https://youtu.be/z2walDTXgQc?si=v6WvMjlXmpHO2v_R

Uvarova, A. (2024, April 30). Sex workers outraged as “AI girlfriend” ads flood Instagram. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2024/04/30/business/sex-workers-outraged-as-ai-girlfriend-ads-flood-instagram/

Vandenbosch, L., & Eggermont, S. (2012). Understanding Sexual Objectification: A Comprehensive Approach Toward Media Exposure and Girls’ Internalization of Beauty Ideals, Self-Objectification, and Body Surveillance. Journal of Communication, 62(5), 869–887. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01667.x

Volpe, A. (2025, February 5). Validate me, please! Vox. https://www.vox.com/even-better/395448/external-validation-people-pleasing-social-media-self-worth

#mda20009#week 7#week7#blog#essay#tumblr#movie review#movies#film#films#sexualised labour#body modification#eighth grade#bo burnham#cam#netflix#a24#a24 films#a24 movies#kat hernandez#euphoria#representation#teenagers#social media#digital communities#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 6: Digital Citizenship Case Study: Social Media Influencers and the Slow Fashion Movement

Can Fashion Ever Escape Capitalism? Slow Fashion’s Paradox

While binge-watching Netflix the other day, I came across a documentary called Buy Now!. One quote stuck with me:

"Whoever dies with the most stuff does not win." (Netflix, 2025)

It made me pause and reflect on a rising trend in the fashion industry—slow fashion. How much of it is truly about sustainability, and how much still keeps us trapped in the cycle of consumption?

youtube

Attached video 1. Netflix's Buy Now! Documentary trailer (Netflix, 2024).

Fashion is more than clothing—it’s identity, culture, and self-expression. But at its core, it’s an industry driven by consumption. No matter how many "eco-friendly" or "conscious" collections emerge, fashion exists to sell. Even slow fashion, despite its ethical stance, still operates within the same system it seeks to challenge.

So, can fashion ever truly detach itself from capitalism? Or is slow fashion just another way to make us feel better about buying more?

Fashion and Capitalism: An Inseparable Pair?

Fashion and capitalism have always been intertwined. From the Industrial Revolution’s textile boom to today’s globalized supply chains, the industry runs on production and consumption cycles (Vilaça, 2022; Thanhauser, 2022). Trends create demand, demand fuels production, and production drives profit—even for so-called sustainable brands, which still rely on selling products labeled as “ethical” or “conscious.”

Slow fashion challenges this system by promoting longevity over disposability (Breton, 2023). It encourages valuing, repairing, and re-wearing clothes instead of constantly replacing them. But at its core, it still depends on consumer spending. Ethical consumption is still consumption. Instead of telling us to stop shopping, slow fashion just asks us to shop differently. But is that really enough?

The Slow Fashion Ideology: A Radical Shift or a Consumerist Illusion?

Slow fashion isn’t just about buying ethically—it’s a mindset that challenges how we engage with fashion. It arose as a response to fast fashion’s wastefulness, advocating for mindful consumption, quality over quantity, and ethical labor practices (Brewer, 2019).

Rooted in anti-consumerist movements, it echoes the rebellious spirit of 1970s subcultures like Hippies and Punks (The American University of Paris, 2024). These groups critiqued the industry’s reliance on planned obsolescence—the strategy of designing products with short lifespans to keep people buying.

Figure 1. Hippies fashion style in the '70s in the United States.

Unlike fast fashion brands that release thousands of styles each month, slow fashion prioritizes craftsmanship, longevity, and sustainability (Domingos et al., 2022). Fast fashion moves at an extreme pace—its production cycle is 48 times faster than traditional fashion (Drew & Yehounme, 2017). Designs go from concept to store shelves in weeks, not months, and instead of just two seasons a year, brands push up to 100 “micro seasons” annually (Siegle, 2015).

Figure 2. Fashion production cycle (Drew & Yehounme, 2017).

In theory, slow fashion sounds like a revolution. In practice, it often struggles to fully detach itself from the consumerist mindset it critiques.

Slow fashion is costly—an ethically made piece can be up to 10 times pricier than fast fashion (Chi et al., 2021). Lingerie expert Cora Harrington broke this down in an X (formerly Twitter) thread, explaining how a $1,000 lingerie piece accounts for lace production (from farmer wages to labor costs), designer fees, materials, shipping, customs, taxes, rent, and employee wages. Every step adds up.

Figure 3. Cora Harrington’s thread on X (Harrington, 2020).

If sustainable fashion is only for the privileged, can it really be the solution?

Slow fashion still relies on consumption—just framed as “better” shopping. Brands market their products as ethical investments, fueling the ethical consumption paradox, where people buy more because it aligns with their values (Arrington, 2017; Carrington et al., 2016).

If slow fashion truly challenged the system, it would promote less shopping, not just smarter shopping. But since it still depends on sales, we have to ask outselves—whether it's truly driving change or simply repackaging consumption under a new label.

Fast Fashion’s Iron Grip: Can Slow Fashion Compete?

If slow fashion is about mindfulness, fast fashion is its overstimulated opposite. Brands like Shein, Zara, and H&M thrive on speed, affordability, and fleeting micro-trends (Brewer, 2019).

Social media, especially TikTok, has supercharged this cycle. Viral trends vanish within weeks, pressuring consumers to constantly refresh their wardrobes. ‘TikTok hauls’—where influencers unbox piles of trendy, low-cost clothing—have normalized mass consumption at an alarming rate (Lai, Henninger, & Alevizou, 2017).

youtube

Attached video 2. TikTok haul compilation (StarryShi, 2021).

The sheer scale of these hauls—often showcasing dozens of items—reinforces a throwaway mindset. In the past three years, over 15 million TikTok videos have used the #haul hashtag, with most viewers being young adults still exploring their identities through fashion (TikTok Creative Center, 2025).

Figure 4. Insights of #haul on TikTok (TikTok Creative Center, 2025).

While some brands prioritize transparency, others use sustainability as a marketing tool (Adi, 2018), often get criticized as "performative marketing". Greenwashing lets companies profit while appearing responsible (Kerner & Gillis, 2023). H&M’s “Conscious Collection” may use organic fabrics, but the brand still produces 3 billion garments annually (Storey, 2021). Slow fashion competes in a system designed to make true sustainability nearly impossible.

youtube

Attached video 3. H&M's 'Conscious Collection' Campaign video (H&M, 2019).