Text

Backpack Backpack, Let's Explore Bitch!

·:*¨༺𖤐☆✮☆𖤐༻¨*:·

When it comes to pretty much any art form, exploration is extremely important. Not only should you explore your creativity, but you should explore everything else, too!

Explore the things that motivate you, your process, your writing program, your vocabulary, explore your favorite cafe's menu, hell get outside, and find something to explore in the real world, too! You never know what you're going to find. Keep exploring, keep learning, and keep using it.

#writeblr#writers on tumblr#writing#writerscommunity#writer things#writblr#writers#writerslife#book blog#writerscorner#original writing#creative writing#writers block#writing stuff#writing advice#writings#thoughts#advice

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you’re experiencing writers block, make a playlist with songs that remind you of your WIP and go on a 30 min walk.

Trust me.

#writeblr#original writing#writing blog#writers of tumblr#creative writing#writing#writerscommunity#writers on tumblr#writer problems#writing a book#writers block

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Most Powerful Hack to Make Your Readers Cry

You’ve seen it all: show, don’t tell, plant a visceral image in the reader’s brain of the environment/character, write a complex character arc with lots of growth and setbacks, establish deep relationships, high stakes, etc.

All the advice for making readers cry I’ve seen so far is basically that list. But, while those things are absolutely important, I find that the thing that always does the trick, whether as a tipping point or in and of itself, is this:

THE CALLBACK!

Before we move on, this is an ANALYSIS heavy post, so all the book + show examples contain spoilers!!

So, what do I mean by a “callback?” Think of Chekhov’s gun, but, here, you use the gun to pierce your reader’s heart. As a refresher for anyone who needs it, Chekhov’s gun is just a rule in writing that anything you introduce in the book should play some role in the plot.

Specifically, the name comes from the example that if a reader introduces a gun in the first act, it MUST go off later, (maybe, say, in the third act). For example, in the TV show Breaking Bad, the protagonist Walter White prepares a vial of poison (ricin) that he wanted to use to eliminate an opponent early on in the series. After the assassination attempt falls through, the ricin makes an appearance again in the very last episode of the show, when Walt finally uses it to kill another opponent.

Got that? Alright, onto the examples of successful, tearjerking callbacks:

1. The Last Olympian (Rick Riordan); “Family, Luke, you promised.”

Context: The character Annabeth says this line. Years ago, Annabeth had run away from home, and Luke had effectively adopted her into a found family with another kid named Thalia. Common reason for leaving home = parental trauma! Yay! He promised Annabeth that they would be each other’s “family” from now on.

Now: Kronos, the antagonist titan, has possessed the demigod Luke and uses his body to strike Annabeth, injuring her. She’s also holding a dagger that Luke had given her when she joined his “family.”

Significance: her words + the dagger are a mental + physical reminder to Luke of his promise. They force him to recognize the sheer degree of his current betrayal by bringing him back to a different time. The fact that their found family only happened because of parental trauma bringing them together makes it worse—Luke felt abandoned by his Olympian father, Hermes. Now, he realizes that he basically did the equivalent to Annabeth by joining the titans.

2. Les Miserables (Victor Hugo); Jean Valjean’s death

Context: At the beginning of the book, the bishop had caught Valjean trying to steal candlesticks to sell. Instead of handing him over to the police, the bishop told the police that he had given them to Valjean, saving him from arrest and showing him mercy. This changed his life forever, kickstarting his character redemption arc.

Now: Jean Valjean dies surrounded by his loved ones, remembered as a benevolent man who bettered thousands of lives. He’s surrounded by light from candlesticks that once belonged to a bishop.

Context: Valjean had once taken in an impoverished woman named Fantine, showing her mercy and promising to take care of her daughter, Cosette, after Fantine died. Valjean then rescued Cosette from abusive quasi-foster parents (it’s a long story), raising her as his own daughter. This furthered his arc by allowing him to finally understand how unconditionally loving someone feels.

Now: Valjean describes Fantine to Cosette, who never knew her mother.

Significance: Both examples throw readers back to much earlier points in the story before the completion of Valjean’s character arc. In a way, this final scene feels like an external manifestation of his kindness paying off; both he and the reader feels a sense of accomplishment, relief, and just a general “OMG WE MADE IT.” Readers don’t feel cheated, because they were with Valjean every step of his 1,400 page arc. The weight of it all just crashes down on you…

3. Your Lie in April (anime); Kaori’s letter after she dies

Context: Kaori’s entire plot significance is that she helps Kousei, a piano prodigy who can’t play piano anymore due to traumatic parental memories associated with it, play again—but also, just to help him enjoy life again after a turbulent upbringing. She meets him a year before she dies of a medical condition, and her free spirit + confidence influences him to find beauty in life and music again. They basically do a crap ton of crazy funny stuff together lol

Now: Kaori has died, and she leaves a letter to him. Among other general confessions and thoughts, she references things they did and memories they shared: she says, “sorry we couldn’t eat all those canelés,” reminisces about jumping with him off a small bridge into the stream below, “racing each other alongside the train,” singing Twinkle Twinkle Little Star as they rode the bike together, etc.

Significance: Yes, the nature of the letter is just sad because she’s revealing that she loved him all along, apologizing for not being able to spend more time with him, lying that she didn’t like him (to spare his feelings b/c she knew she would die soon), etc. BUT, these small details highlight exactly how many experiences they shared, and the depth of their relationship. Thus, they emphasize the significance of her death and the emptiness it leaves behind.

4. Arcane (show); “I thought, maybe you could love me like you used to, even though I’m different.”

Context: Character Jinx says this in the last episode to her now estranged older sister, Vi. Without going into the crazy complex plot, basically, orphans Vi and Jinx used to care for each other before a bunch of crap went down that got them separated. They then grew up on opposite political sides; Jinx grows up on the side of the underbelly city rebellion, and Vi grows up working on the side of the richer city that essentially oppresses the undercity. Thus begins the development of their opposing viewpoints and work environments, to the point where they always meet on opposite sides of a political battle, never able to come together as a family or understand each other again.

Now: After a super dramatic confrontation, Jinx reveals that although she wants Vi to love her like she did before their separation, she knows it’s not possible because “[Vi] changed too.” She finishes with, “so, here’s to the new us” before blowing up a political council meeting a few blocks down filled with people Vi sides with. Oops! This cleanly seals the fate of their relationship as something basically irreparable.

Significance: This callback isn’t through literal flashbacks or items like in the previous examples. Jinx’ lines are enough to bring back images of their childhood to the audience’s mind. Now, the audience subconsciously places this image of: 1) two sisters so different, hurt, and torn apart, right next to 2) the image of two sisters as innocent children who loved each other and would care for each other no matter what.

Why do callbacks work so well?

If you’ve noticed something in common with all of them, you’re right: they remind audience of a time BEFORE the characters have come so far on their arcs, developed, and put on so much more emotional baggage.

Callbacks force the audience to SUDDENLY and IMMEDIATELY feel the weight of everything that’s happened. The character’s anguish and overwhelming emotions become the audience’s in this moment. Callbacks are a vehicle for the juxtaposition of worlds, before and after significant development.

This works because we, as mortals, fear IMPERMANENCE the most. We fear LOSS. For us, time gone is time we will never get back; callbacks make us face that exact fact through a fictional character. A lost moment, time period, or even part of oneself may hurt as much as losing a loved one, and nothing makes humans grieve more than the realization of a loss. A callback slaps the audience in the face with the fact that something was lost; loss hurts so much because almost 99% of the time, what’s gone is gone forever.

Of course, a good callback requires good previous character development, stakes, imagery, and all that jazz, but I thought I’d highlight this specifically because of how under covered it is.

∘₊✧────── ☾☼☽ ──────✧₊∘

instagram: @ grace_should_write

I’ve been binging general media lately: I finished Death Note, Your Lie in April, and Tokyo Ghoul all within like a month (FIRST ANIMES I”VE EVER WATCHED!!), reread lots of Les Miserables, analyzed a bunch of past shows like Breaking Bad, watched a bunch of My Little Pony, worked to fix up my old writing… and that’s not even all! The amount of times I’ve CRIED while enjoying the above media and so much more honestly just inspired this post.

Like, no joke, my eyes were almost always swollen during this period whenever I hung out with my friends and it was so embarrassing help

Personally, I just find that this method works super well for me, and I watched a bunch of reaction videos to these above scenes (and read book reviews on the book scenes I mentioned), and it seemed that just about everyone cried during these parts. That’s when I realizes that the callback might also just be a universal thing.

Anyway, this post is long and dense enough as is. SORRY! As always, hope this was helpful, and let me know if you have any questions by commenting, re-blogging, or DMing me on IG. Any and all engagement is appreciated <3333

Happy writing, and have a great day,

- grace <3

#writing tips#writers on tumblr#booktok#writing#writer#writeblr#writerslife#novel#writergram#wattpad#wip#media analysis#writing ideas#plot holes#writing a book#anime#ya fantasy#characters

741 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to make your writing sound less stiff

Just a few suggestions. You shouldn’t have to compromise your writing style and voice with any of these, and some situations and scenes might demand some stiff or jerky writing to better convey emotion and immersion. I am not the first to come up with these, just circulating them again.

1. Vary sentence structure.

This is an example paragraph. You might see this generated from AI. I can’t help but read this in a robotic voice. It’s very flat and undynamic. No matter what the words are, it will be boring. It’s boring because you don’t think in stiff sentences. Comedians don’t tell jokes in stiff sentences. We don’t tell campfire stories in stiff sentences. These often lack flow between points, too.

So funnily enough, I had to sit through 87k words of a “romance” written just like this. It was stiff, janky, and very unpoetic. Which is fine, the author didn’t tell me it was erotica. It just felt like an old lady narrator, like Old Rose from Titanic telling the audience decades after the fact instead of living it right in the moment. It was in first person pov, too, which just made it worse. To be able to write something so explicit and yet so un-titillating was a talent. Like, beginner fanfic smut writers at least do it with enthusiasm.

2. Vary dialogue tag placement

You got three options, pre-, mid-, and post-tags.

Leader said, “this is a pre-dialogue tag.”

“This,” Lancer said, “is a mid-dialogue tag.”

“This is a post-dialogue tag,” Heart said.

Pre and Post have about the same effect but mid-tags do a lot of heavy lifting.

They help break up long paragraphs of dialogue that are jank to look at

They give you pauses for ~dramatic effect~

They prompt you to provide some other action, introspection, or scene descriptor with the tag.

*don't forget that if you're continuing the sentence as if the tag wasn't there, not to capitalize the first word after the tag. Capitalize if the tag breaks up two complete sentences, not if it interrupts a single sentence.

It also looks better along the lefthand margin when you don’t start every paragraph with either the same character name, the same pronouns, or the same “ as it reads more natural and organic.

3. When the scene demands, get dynamic

General rule of thumb is that action scenes demand quick exchanges, short paragraphs, and very lean descriptors. Action scenes are where you put your juicy verbs to use and cut as many adverbs as you can. But regardless of if you’re in first person, second person, or third person limited, you can let the mood of the narrator bleed out into their narration.

Like, in horror, you can use a lot of onomatopoeia.

Drip

Drip

Drip

Or let the narration become jerky and unfocused and less strict in punctuation and maybe even a couple run-on sentences as your character struggles to think or catch their breath and is getting very overwhelmed.

You can toss out some grammar rules, too and get more poetic.

Warm breath tickles the back of her neck. It rattles, a quiet, soggy, rasp.

She shivers. If she doesn’t look, it’s not there. If she doesn’t look, it’s not there. Sweat beads at her temple. Her heart thunders in her chest. Ba-bump-ba-bump-ba-bump-ba-

It moves on, leaving a void of cold behind.

She uncurls her fists, fingers achy and palms stinging from her nails.

It’s gone.

4. Remember to balance dialogue, monologue, introspection, action, and descriptors.

The amount of times I have been faced with giant blocks of dialogue with zero tags, zero emotions, just speech on a page like they’re notecards to be read on a stage is higher than I expected. Don’t forget that though you may know exactly how your dialogue sounds in your head, your readers don’t. They need dialogue tags to pick up on things like tone, specifically for sarcasm and sincerity, whether a character is joking or hurt or happy.

If you’ve written a block of text (usually exposition or backstory stuff) that’s longer than 50 words, figure out a way to trim it. No matter what, break it up into multiple sections and fill in those breaks with important narrative that reflects the narrator’s feelings on what they’re saying and whoever they’re speaking to’s reaction to the words being said. Otherwise it’s meaningless.

—

Hope this helps anyone struggling! Now get writing.

#writing#writing advice#writing a book#writing resources#writing tips#writing tools#for beginners#refresher#writeblr#book formatting#sentence structure

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Creating a magic system for my Book

I should say that I started out my writing career by trying to make as many stories as I could in the shortest amount of time with all of these creative and imaginative ideas. Then I realized that it was too ambitious, that obviously this takes time, and part of that time that I needed to spend was on a magic system.

At first it was inspired by the Infinity stones that I saw in Avengers, then I watched arcane. Every time I keep seeing things like this I was like okay cool, rocks, I want to do that. So in one of my earlier stories that I tried to craft, the cities were powered by magical rocks, and as the story progressed, they gained more explanation. They were special crystals made out of silicon that had the ability to take light and turn it directly into energy that happened to be a specific color. (The crystals could also create life but that is not important right now)

That is where the idea that my magic system would draw on the light spectrum, and where it earned its name, Ma'alight (from Mana and light) however there were a few hick ups that I found along the way. When I began writing the story that I am working on now, I decided that the main character and his daughter would be able to use magic that glowed black. Now if you know things about color, black isn't a color, it's the absence of color. But I couldn't just scrap all of my ideas, so I came up with a solution.

The plot of my book is boosted by the characters having access to Ma'alight, and an important trial that they must overcome involves them being unable to use their powers. This involved taking light away, but instead of everything going black, everything goes greyscale, this (in the story's universe) becomes known as void, an anti magic / colorless emptiness that makes it impossible for the characters to channel their energy.

Now there are still other things that my magic system can do, like household, for fighting, as well as create manifestations out of light and even be corrupted >:)

So, my magic system was created to enhance the plot and it came with some cool things along the way. Please let me know if you'd like to know more!

#interesting#to read#to analyze#writeblr#writing#writers on tumblr#worldbuilding#bookblr#booklr#writerscommunity#original story#creative writing#books

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Telling Better Stories

Your story, novel, fic, whatever, is made up of scenes, right? These scenes should always have a point and should be moving the story forward in some way in order for your readers to not get bored. Nobody loves 100k of just fluff (if you do, bb we need to unpack that).

One way to structure an impactful scene and story is to follow something called the Hegelian Dialectic, which is where you take a thesis (true statement) and then apply that to an antithesis (no, that's actually not true because of 'x').

When those two things collide, your characters then have to confront that difference and create a new thesis based on this information. Then they enter the next act with that new thesis, get confronted with another antithesis, and so on and so on.

And who is the person torturing the characters and making them confront these? You.

How do you start this process? Your character should be introduced to us in some kind of stasis. Some kind of norm that they are used to, and then you need to disrupt it. Really shove the knife in and make it uncomfortable, make them really face the thesis head on.

Then you should force them into a decision where they can never go back to that stasis ever again. And then make that painful.

In short, your character should have a different outlook when we leave them than when the story began. They should be changed and we should believe it. That is why, they need to be given the opportunity to go back to the old stasis ways, but then reject the opportunity because they have grown and now know better.

Struggling? Drop me a line! My ask box is open!

#creative writing#writers on tumblr#writing#writeblr#writing advice#story writing#build a better narrative#storytelling#to check

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

the thing folks living in Christian dominant cultures gotta realize is that even if you’re not Christian, your basic understanding of religion and spirituality and morality is still being filtered through a Christian lens. your very concept of what religion is and does is filtered through that lens.

129K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Causal Chain And Why Your Story Needs It

The most obnoxious thing my writing teacher taught me every story needed, that I absolutely loathed studying in the moment and that only later, after months of resisting and fighting realized she was right, was something called the causal chain.

Simply put, the causal chain is the linked cause-and-effect that must logically connect every event, reaction, and beat that takes place in your story to the ones before and after.

The Causal Chain is exhausting to go through. It is infuriating when someone points out that an event or a character beat comes out of nowhere, unmoored from events around it.

It is profoundly necessary to learn and include because a cause-and-effect chain is what allows readers to follow your story logically which means they can start anticipating what happens next, which is what is required for a writer to be able to build suspense and cognitively engage the audience, to surprise them, and to not infuriate them with random coincidences that hurt or help the characters in order to clumsily advance the author's goals.

By all means, write your story as you want to write it in the first draft, and don't worry about this principle too much. This is an editing tool, not a first draft tool. But one of the first things you should do when retroactively begin preparing your story to be read by others is going step by step through each event and confirming that a previous event leads to it and that subsequent events are impacted by it on the page.

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

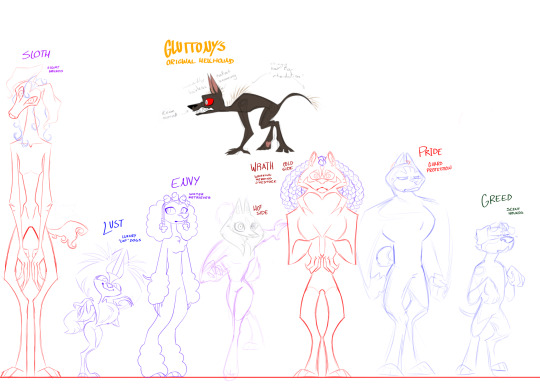

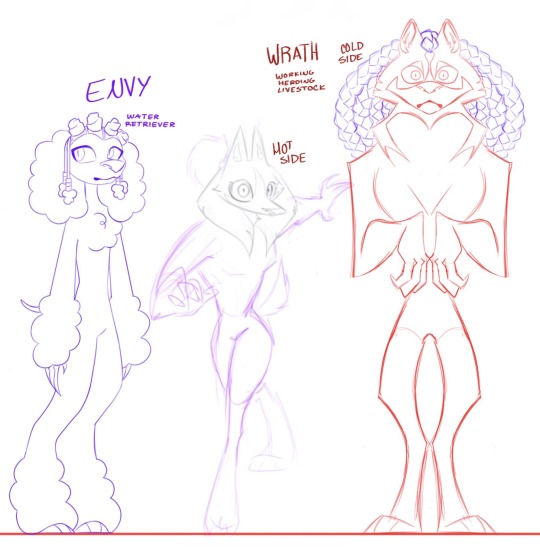

I wanted to finish this one unfortunately I got tired so I’ll just do it another day jiji

Anyways here is a small explication on the Hellhound situation in my rewrite. Basically all breeds originate from Gluttony’s original hound, created by Lilith and later taken care by Beelzebub as their Queen because of her canine likeness and her indulgence of sinful desires. Since the Hellhounds were once the most desperate and neglected of demons, Queen Bee´s lifestyle was really admired by the hounds. Since Hell is divided by rings, each ring was a specific weather and environment in which the original residents evolved into their most efficient form to thrive in, including Hellhounds. Gluttony´s original hound is a breed similar to the Xoloitzcluintle and slowly the species gained alternative breeds by the long evolutionary history of living in the different rings. I tried to keep their features consistent (since I do like the idea of the hellhounds reflecting earth breeds) so I categorized them from working purposes and habitat. Nowadays you can find almost every breed in all rings, especially in Gluttony, but they do thrive better in their home Rings.

449 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Show, Don’t Tell”…But This Time Someone Explains It

If you’ve ever been on the hunt for writing advice, you've definitely seen the phrase “Show, Don’t Tell.”

Writeblr coughs up these three words on the daily; it’s often considered the “Golden Rule” of writing. However, many posts don't provide an in-depth explanation about what this "Golden Rule" means (This is most likely to save time, and under the assumption that viewers are already informed).

More dangerously, some posts fail to explain that “Show, Don’t Tell” occasionally doesn’t apply in certain contexts, toeing a dangerous line by issuing a blanket statement to every writing situation.

The thing to take away from this is: “Show, Don’t Tell” is an essential tool for more immersive writing, but don't feel like a bad writer if you can’t make it work in every scenario (or if you can’t get the hang of it!)

1. What Does "Show, Don't Tell" Even Mean?

“Show, Don’t Tell” is a writing technique in which the narrative or a character’s feelings are related through sensory details rather than exposition. Instead of telling the reader what is happening, the reader infers what is happening due to the clues they’ve been shown.

EXAMPLE 1:

Telling: The room was very cold.

Showing: She shivered as she stepped into the room, her breath steaming in the air.

EXAMPLE 2:

Telling: He was furious.

Showing: He grabbed the nearest book and hurled it against the wall, his teeth bared and his eyes blazing.

EXAMPLE 3 ("SHOW, DON'T TELL" DOESN'T HAVE TO MEAN "WRITE A LOT MORE")

Telling: The room hadn't been lived in for a very long time.

Showing: She shoved the door open with a spray of dust.

Although the “showing” sentences don’t explicitly state how the characters felt, you as the reader use context clues to form an interpretation; it provides information in an indirect way, rather than a direct one.

Because of this, “Show, Don’t Tell” is an incredibly immersive way to write; readers formulate conclusions alongside the characters, as if they were experiencing the story for themselves instead of spectating.

As you have probably guessed, “showing” can require a lot more words (as well as patience and effort). It’s a skill that has to be practiced and improved, so don’t feel discouraged if you have trouble getting it on the first try!

2. How Do I Use “Show, Don’t Tell” ?

There are no foolproof parameters about where you “show” and not “tell" or vice versa; it’s more of a writing habit that you develop rather than something that you selectively decide to employ.

In actuality, most stories are a blend of both showing and telling, and more experienced writers instinctively switch between one and another to cater to their narrative needs. You need to find a good balance of both in order to create a narrative that is both immersive and engaging.

i. Help When Your Writing Feels Bare-Bones/Soulless/Boring

Your writing is just not what you’ve pictured in your head, no matter how much you do it over. Conversations are stilted. The characters are flat. The sentences don’t flow as well as they do in the books you've read. What’s missing?

It’s possibly because you’ve been “telling” your audience everything and not “showing”! If a reader's mind is not exercised (i.e. they're being "spoon-fed" all of the details), your writing may feel boring or uninspired!

Instead of saying that a room was old and dingy, maybe describe the peeling wallpaper. The cobwebs in the corners. The smell of dust and old mothballs. Write down what you see in your mind's eye, and allow your audience to formulate their own interpretations from that. (Scroll for a more in-depth explanation on HOW to develop this skill!)

ii. Add More Depth and Emotion to Your Scenes

Because "Show, Don't Tell" is a more immersive way of writing, a reader is going to feel the narrative beats of your story a lot more deeply when this rule is utilized.

Describing how a character has fallen to their knees sobbing and tearing our their hair is going to strike a reader's heart more than saying: "They were devastated."

Describing blood trickling through a character's fingers and staining their clothes will seem more dire than saying: "They were gravely wounded."

iii. Understand that Sometimes Telling Can Fit Your Story Better

Telling can be a great way to show your characters' personalities, especially when it comes to first-person or narrator-driven stories. Below, I've listed a few examples; however, this list isn't exclusive or comprehensive!

Initial Impressions and Character Opinions

If a character describes someone's outfit as "gaudy" or a room as "absolutely disgusting," it can pack more of a punch about their initial impression, rather than describing the way that they react (and can save you some words!).

In addition, it can provide some interesting juxtaposition (i.e. when a character describes a dog as "hideous" despite telling their friend it looks cute).

2. Tone and Reader Opinions

Piggybacking off of the first point, you can "tell, not show" when you want to be certain about how a reader is supposed to feel about something. "Showing" revolves around readers drawing their own conclusions, so if you want to make sure that every reader draws the same conclusion, "telling" can be more useful!

For example, if you describe a character's outfit as being a turquoise jacket with zebra-patterned pants, some readers may be like "Ok yeah a 2010 Justice-core girlie is slaying!" But if you want the outfit to come across as badly arranged, using a "telling" word like "ridiculous" or "gaudy" can help set the stage.

3. Pacing

"Show, don't tell" can often take more words; after all, describing a character's reaction is more complicated than stating how they're feeling. If your story calls for readers to be focused more on the action than the details, such as a fight or chase scene, sometimes "telling" can serve you better than "showing."

A lot of writers have dedicated themselves to the rule "tell action, show emotion," but don't feel like you have to restrict yourself to one or the other.

iv. ABOVE ALL ELSE: Getting Words on the Page is More Important!

If you’re stuck on a section of your story and just can’t find it in yourself to write poetic, flowing prose, getting words on the paper is more important than writing something that’s “good.” If you want to be able to come back and fix it later, put your writing in brackets that you can Ctrl + F later.

Keeping your momentum is the hardest part of writing. Don't sacrifice your inspiration in favor of following rules!

3. How Can I Get Better at “Show, Don’t Tell”?

i. Use the Five Senses, and Immerse Yourself!

Imagine you’re the protagonist, standing in the scene that you have just created. Think of the setting. What are things about the space that you’d notice, if you were the one in your character’s shoes?

Smell? Hear? See? Touch? Taste?

Sight and sound are the senses that writers most often use, but don’t discount the importance of smell and taste! Smell is the most evocative sense, triggering memories and emotions the moment someone walks into the room and has registered what is going on inside—don’t take it for granted. And even if your character isn’t eating, there are some things that can be “tasted” in the air.

EXAMPLE:

TELLING: She walked into the room and felt disgusted. It smelled, and it was dirty and slightly creepy. She wished she could leave.

SHOWING: She shuffled into the room, wrinkling her nose as she stepped over a suspicious stain on the carpet. The blankets on the bed were moth-bitten and yellowed, and the flowery wallpaper had peeled in places to reveal a layer of blood-red paint beneath…like torn cuticles. The stench of cigarettes and mildew permeated the air.

“How long are we staying here again?” she asked, flinching as the door squealed shut.

The “showing” excerpt gives more of an idea about how the room looks, and how the protagonist perceives it. However, something briefer may be more suited for writers who are not looking to break the momentum in their story. (I.e. if the character was CHASED into this room and doesn’t have time to take in the details.)

ii. Study Movies and TV Shows: Think like a Storyteller, Not Just a Writer

Movies and TV shows quite literally HAVE TO "show, and not tell." This is because there is often no inner monologue or narrator telling the viewers what's happening. As a filmmaker, you need to use your limited time wisely, and make sure that the audience is engaged.

Think about how boring it would be if a movie consisted solely of a character monologuing about what they think and feel, rather than having the actor ACT what they feel.

(Tangent, but there’s also been controversy that this exposition/“telling” mindset in current screenwriting marks a downfall of media literacy. Examples include the new Percy Jackson and Avatar: The Last Airbender remakes that have been criticized for info-dumping dialogue instead of “showing.”)

If you find it easy to envision things in your head, imagine how your scene would look in a movie. What is the lighting like? What are the subtle expressions flitting across the actors' faces, letting you know just how they're feeling? Is there any droning background noise that sets the tone-- like traffic outside, rain, or an air conditioner?

How do the actors convey things that can't be experienced through a screen, like smell and taste?

Write exactly what you see in your mind's eye, instead of explaining it with a degree of separation to your readers.

iii. Listen to Music

I find that because music evokes emotion, it helps you write with more passion—feelings instead of facts! It’s also slightly distracting, so if you’re writing while caught up in the music, it might free you from the rigid boundaries you’ve put in place for yourself.

Here’s a link to my master list of instrumental writing playlists!

iv. Practice, Practice, Practice! And Take Inspiration from Others!

“Show Don’t Tell” is the core of an immersive scene, and requires tons of writing skills cultivated through repeated exposure. Like I said before, more experienced writers instinctively switch between showing and telling as they write— but it’s a muscle that needs to be constantly exercised!

If I haven’t written in a while and need to get back into the flow of things, I take a look at a writing prompt, and try cultivating a scene that is as immersive as possible! Working on your “Show, Don’t Tell” skills by practicing writing short, fun one-shots can be much less restrictive than a lengthier work.

In addition, get some inspiration and study from reading the works of others, whether it be a fanfiction or published novel!

If you need some extra help, feel free to check out my Master List of Writing Tips and Advice, which features links to all of my best posts, each of them categorized !

Hope this helped, and happy writing!

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

morality: a character creation guide

creating and understanding your oc’s personal moral code! no, i cannot tell you whether they’re gonna come out good or bad or grey; that part is up to you.

anyway, let’s rock.

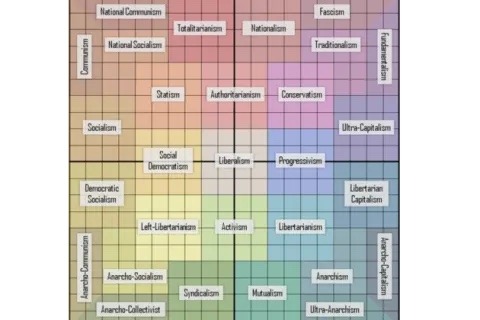

i. politics

politics are a good way to indicate things your character values, especially when it comes to large-scale concepts such as government, community, and humanity as a whole.

say what you will about either image; i’d argue for the unintiated, the right image is a good introduction to some lesser discussed ideologies… some of which your oc may or may not fall under.

either way, taking a good look at your character’s values on the economic + social side of things is a good place to start, as politics are something that, well… we all have ‘em, you can’t avoid ‘em.

clearly, this will have to be adjusted for settings that utilize other schools of thought (such as fantasy + historical fiction and the divine right of kings), but again, economic/social scale plotting will be a good start for most.

ii. religion + philosophy

is your oc religious? do they believe in a form of higher power? do they follow some sort of philosophy?

are they devout? yes, this applies to non-religious theist and atheist characters as well; in the former’s case… is their belief in a higher power something that guides many of their actions or is their belief in a higher power something that only informs a few of their actions? for the atheists; do they militant anti-theists who believe atheism is the only way and that religion is harmful? or do they not care about religion, so long as it’s thrust upon them?

for the religious: what is your oc’s relationship with the higher power in question? are they very progressive by their religion’s standards or more orthodox? how well informed of their own religion are they?

does your oc follow a particular school of philosophical thought? how does that interact with their religious identification?

iii. values

by taking their political stance and their religious + philosophical stance, you have a fairly good grasp on the things your character values.

is there anything they value - due to backstory, or what they do, or what they love - that isn’t explained by political stance and religious and/or philosophical identification? some big players here will likely be your oc’s culture and past.

of everything you’ve determined they value, what do they value the most?

iv. “the line”

everyone draws it somewhere. we all have a line we won’t cross, no matter the lengths we go for what we believe is a noble cause. where does your character draw it? how far will they go for something they truly believe is a noble cause? as discussed in part iii of my tips for morally grey characters,

would they lie? cheat? steal? manipulate? maim? what about commit acts of vandalism? arson? would they kill?

but even when we have a line, sometimes we make exceptions for a variety of reasons. additionally, there are limits to some of the lengths we’d go to.

find your character’s line, their limits and their exceptions.

v. objectivism/relativism

objectivism, as defined by the merriam-webster dictionary, is “an ethical theory that moral good is objectively real or that moral precepts are objectively valid.”

relativism, as defined by the merriam-webster dictionary, is “a view that ethical truths depend on the individuals and groups holding them.”

what take on morality, as a concept, does your character have? is morality objective? is morality subjective?

we could really delve deep into this one, but this post is long enough that i don’t think we need to get into philosophical rambling… so this is a good starting point.

either way, exploring morality as a concept and how your character views it will allow for better application of their personal moral code.

vi. application

so, now you know what they believe and have a deep understanding of your character’s moral code, all that’s left is to apply it and understand how it informs their actions while taking their personality into account.

and interesting thing to note is that we are all hypocrites; you don’t have to do this, but it might be fun to play around with the concept of their moral code and add a little bit of hypocrisy to their actions as a treat.

either way, how do your character’s various beliefs interact? how does it make them interact with the world? with others? with their friends, family, and community? with their government? with their employment? with their studies? with the earth and environment itself?

in conclusion:

there’s a lot of things that inform one’s moral compass and i will never be able to touch on them all; however, this should hopefully serve as at least a basic guide.

#ldknightshade.txt#writing#creative writing#writing ideas#writing inspiration#writing tips#writing help#writing advice#writing tumblr#writeblr#how to write

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Weird Brain Hacks That Help Me Write

I'm a consistently inconsistent writer/aspiring novelist, member of the burnt-out-gifted-kid-to-adult-ADHD-diagnosis-pipeline, recently unemployed overachiever, and person who's sick of hearing the conventional neurotypical advice to dealing with writer's block (i.e. "write every single day," or "there's no such thing as writer's block- if you're struggling to write, just write" Like F*CK THAT. Thank you, Brenda, why don't you go and tell someone with diabetes to just start producing more insulin?)

I've yet to get to a point in my life where I'm able to consistently write at the pace I want to, but I've come a long way from where I was a few years ago. In the past five years I've written two drafts of a 130,000 word fantasy novel (currently working on the third) and I'm about 50,000 words in on the sequel. I've hit a bit of a snag recently, but now that I've suddenly got a lot of time on my hands, I'm hoping to revamp things and return to the basics that have gotten me to this point and I thought I might share.

1) My first draft stays between me and God

I find that I and a lot of other writers unfortunately have gotten it into our heads that first drafts are supposed to resemble the finished product and that revisions are only for fixing minor mistakes. Therefore, if our first draft sucks that must mean we suck as writers and having to rewrite things from scratch means that means our first draft is a failure.

I'm here to say that is one of the most detrimental mentalities you can have as a writer.

Ever try drawing a circle? You know how when you try to free-hand draw a perfect circle in one go, it never turns out right? Whereas if you scribble, say, ten circles on top of one another really quickly and then erase the messy lines until it looks like you drew a circle with a singular line, it ends up looking pretty decent?

Yeah. That's what the drafting process is.

Your first draft is supposed to suck. I don't care who you are, but you're never going to write a perfect first draft, especially if you're inexperienced. The purpose of the first draft is to lay down a semi-workable foundation. A really loose, messy sketch if you will. Get it all down on paper, even if it turns out to be the most cliche, cringe-inducing writing you've ever done. You can work out those kinks in the later drafts. The hardest part of the first draft is the most crucial part: getting started. Don't stress yourself out and make it even harder than it already is.

If that means making a promise to yourself that no one other than you will ever read your first draft unless it's over your cold, dead body, so be it.

2) Tell perfectionism to screw off by writing with a pen

I used to exclusively write with pencil until I realized I was spending more time erasing instead of writing.

Writing with a pen keeps me from editing while I right. Like, sometimes I'll have to cross something out or make notes in the margins, but unlike erasing and rewriting, this leaves the page looking like a disaster zone and that's a good thing.

If my writing looks like a complete mess on paper, that helps me move past the perfectionist paralysis and just focus on getting words down on the page. Somehow seeing a page full of chicken scratch makes me less worried about making my writing all perfect and pretty- and that helps me get on with my main goal of fleshing out ideas and getting words on a page.

3) It's okay to leave things blank when you can't think of the right word

My writing, especially my first draft, is often filled with ___ and .... and (insert name here) and red text that reads like stage directions because I can't think of what is supposed to go there or the correct way to write it.

I found it helps to treat my writing like I do multiple choice tests. Can't think of the right answer? Just skip it. Circle it, come back to it later, but don't let one tricky question stall you to the point where you run out of brain power or run out of time to answer the other questions.

If I'm on a role, I'm not gonna waste it by trying to remember that exact word that I need or figure out the right transition into the next scene or paragraph. I'm just going to leave it blank, mark to myself that I'll need to fix the problem later, and move on.

Trust me. This helps me sooooo much with staying on a roll.

4) Write Out of Order

This may not be for everyone, but it works wonders for me.

Sure, the story your writing may need to progress chronologically, but does that mean you need to write it chronologically? No. It just needs to be written.

I generally don't do this as much for editing, but for writing, so long as you're making progress, it doesn't matter if it's in the right order. Can't think of how to structure Chapter 2, but you have a pretty good idea of how your story's going to end? Write the ending then. You'll have to go back and write Chapter 2 eventually, but if you're feeling more motivated to write a completely different part of the book, who's to say you can't do that?

When I'm working on a project, I start off with a single document that I title "Scrap for (Project Title)" and then just write whatever comes to mind, in whatever order. Once I've gotten enough to work with, then I start outlining my plot and predicting how many chapters I'm going to need. Then, I create separate google docs for each individual chapter and work on them in whatever order I feel like, often leaving several partially complete as I jump from one to the other. Then, as each one gets finished, I copy and paste the chapter into the full manuscript document. This means that the official "draft" could have Chapters 1 and 9, but completely be missing Chapters 2-8, and that's fine. It's not like anyone will ever know once I finish it.

Sorry for the absurdly long post. Hopes this helps someone. Maybe I'll share more tricks in the future.

#creative writing#writing#writerscommunity#writers on tumblr#writing tips#writing advice#novel writing#writers block#fiction writing#writer#writers of tumblr

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's talk about misdirection.

(Requested by @voiceless9000. Hope this is helpful!)

Misdirection in storytelling, through foreshadowing and other techniques, is a powerful tool that can enhance suspense, surprise, and engagement in your narrative and make plot twists more unexpected.

Remember to maintain coherence and avoid contrivances that may undermine the integrity of your storytelling.

Here are some techniques you can use to effectively misdirect readers:

Red Herrings: Introduce elements or clues that suggest a certain outcome or plot direction, only to later reveal that they were misleading. These false leads can divert readers' attention away from the true resolution.

Selective Detailing: Highlight certain details or events in a way that implies their significance, while downplaying or omitting others that might be more relevant to the actual outcome. By controlling what information readers focus on, you can steer their expectations.

Character Misdirection: Use characterisation to mislead readers about characters' true intentions, motivations, or identities. Create multi-dimensional characters who may behave ambiguously or inconsistently, leaving readers unsure of their true allegiances, motivations, or goals.

Foreshadowing: Employ foreshadowing to hint at future events or outcomes, but do so in a way that misleads interpretation. Provide clues that could be interpreted in multiple ways or that lead readers to expect one outcome while delivering another. (See my previous post about foreshadowing for more!)

Misleading Narration: Utilise an unreliable narrator or perspective to present events in a biased or distorted manner. Readers may trust the narrator's account implicitly, only to discover later that their perceptions were flawed or intentionally deceptive.

Subverting Tropes: Set up situations or scenarios that seem to follow familiar narrative tropes or conventions, only to subvert them in unexpected ways. This can keep readers guessing and prevent them from accurately predicting the story's trajectory.

Parallel Storylines: Introduce secondary storylines or subplots that appear unrelated to the main narrative but eventually intersect or influence the primary plot in unexpected ways. This can distract readers from anticipating the main storyline's developments.

Setting: Manipulate the setting or environment to create false impressions about the direction of the plot. For example, presenting a seemingly idyllic setting that harbors dark secrets or dangers.

Timing and Pacing: Control the pacing of your story to strategically reveal information or developments at opportune moments, leading readers to draw premature conclusions or overlook important details. (See my post on pacing for more tips!)

Twists and Reversals: Incorporate sudden plot twists or reversals that upend readers' expectations and challenge their assumptions about the story's direction. Ensure that these twists are logically consistent but sufficiently surprising to catch readers off guard.

Happy writing!

Previous | Next

#writeblr#writing#writing advice#writing tips#writing help#writing resources#deception-united#plot development

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

What is... Alpha vs. Beta Reader?

Most writers do not publish a work without it going through the process of being critiqued by multiple people beforehand. People that do the critiquing are alpha and beta readers.

But where is the difference?

Alpha readers come in first. They can read your draft at any point, you can even just run your first ideas by them. The alpha reader should focus on the general story, the bigger picture. They tell you where plot holes are and if an idea or scene in underdeveloped. They will tell you if one of your ideas just don't translate on the page just yet. You should take their feedback and apply it.

After working on the draft with the feedback you got, it's time for the beta reader. This one comes in towards the end, when the overall draft is finished. A beta reader should represent your target audience and should tell you what they liked and didn't like as a reader, not a fellow writer. They can tell you about what they felt while reading your story and if they cared about the characters. Beta readers will examine the whole story like the alpha readers, but they will do it more in-depth, which is why it's important to have them come in at the end, when you've gone through multiple rounds of revisions of the overall story.

#what is... wednesday#writing help#writing tips#writeblr#writing community#writing advice#writers on tumblr#alpha reader#beta reader

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Where to Start Your Research When Writing a Disabled Character

[large text: Where to Start Your Research When Writing a Disabled Character]

So you have decided that you want to make a disabled character! Awesome. But what's next? What information should you decide on at the early phrase of making the character?

This post will only talk about the disability part of the character creation process. Obviously, a disabled character needs a personality, interests, and backstory as every other one. But by including their disability early in the process, you can actually get it to have a deeper effect on the character - disability shouldn't be their whole life, but it should impact it. That's what disabilities do.

If you don't know what disability you would want to give them in the first place;

[large text: If you don't know what disability you would want to give them in the first place;]

Start broad. Is it sensory, mobility related, cognitive, developmental, autoimmune, neurodegenerative; maybe multiple of these, or maybe something else completely? Pick one and see what disabilities it encompasses; see if anything works for your character. Or...

If you have a specific symptom or aid in mind, see what could cause them. Don't assume or guess; not every wheelchair user is vaguely paralyzed below the waist with no other symptoms, not everyone with extensive scarring got it via physical trauma. Or...

Consider which disabilities are common in real life. Cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, stroke, cataracts, diabetes, intellectual disability, neuropathy, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, thyroid disorders, autism, dwarfism, arthritis, cancers, brain damage, just to name a few.

Decide what specific type of condition they will have. If you're thinking about them having albinism, will it be ocular, oculocutaneous, or one of the rare syndrome-types? If you want to give them spinal muscular atrophy, which of the many possible onsets will they have? If they have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, which one out of the 13 different types do they have? Is their amputation below, or above the knee (it's a major difference)? Not all conditions will have subtypes, but it's worth looking into to not be surprised later. This will help you with further research.

If you're really struggling with figuring out what exact disability would make sense for your character, you can send an ask. Just make sure that you have tried the above and put actual specifics in your ask to give us something to work with. You can also check out our "disabled character ideas" tag.

Here are some ideas for a character using crutches.

Here are some ideas for a character with a facial difference (obligatory link: what is a facial difference?).

If you already know what disability your character is going to have;

[large text: If you already know what disability your character is going to have;]

Start by reading about the onset and cause of the condition. It could be acquired, congenital, progressive, potentially multiple of these. They could be caused by an illness, trauma, or something else entirely. Is your character a congenital amputee, or is it acquired? If acquired - how recently? Has it been a week, or 10 years? What caused them to become disabled - did they have meningitis, or was it an accident? Again, check what your options are - there are going to be more diverse than you expect.

Read about the symptoms. Do not assume or guess what they are. You will almost definitely discover something new. Example: a lot of people making a character with albinism don't realize that it has other symptoms than just lack of melanin, like nystagmus, visual impairment, and photophobia. Decide what your character experiences, to what degree, how frequently, and what do they do (or don't do) to deal with it.

Don't give your character only the most "acceptable" symptoms of their disability and ignore everything else. Example: many writers will omit the topic of incontinence in their para- and tetraplegic characters, even though it's extremely common. Don't shy away from aspects of disability that aren't romanticized.

Don't just... make them abled "because magic". If they're Deaf, don't give them some ability that will make them into an essentially hearing person. Don't give your blind character some "cheat" so that they can see, give them a cane. Don't give an amputee prosthetics that work better than meat limbs. To have a disabled character you need to have a character that's actually disabled. There's no way around it.

Think about complications your character could experience within the story. If your character wears their prosthetic a lot, they might start to experience skin breakdown or pain. Someone who uses a wheelchair a lot has a risk of pressure sores. Glowing and Flickering Fantasy Item might cause problems for someone photophobic or photosensitive. What do they do when that happens, or how do they prevent that from happening?

Look out for comorbidities. It's rare for disabled people to only have one medical condition and nothing else. Disabilities like to show up in pairs. Or dozens.

If relevant, consider mobility aids, assistive devices, and disability aids. Wheelchairs, canes, rollators, braces, AAC, walkers, nasal cannulas, crutches, white canes, feeding tubes, braillers, ostomy bags, insulin pumps, service dogs, trach tubes, hearing aids, orthoses, splints... the list is basically endless, and there's a lot of everyday things that might count as a disability aid as well - even just a hat could be one for someone whose disability requires them to stay out of the sun. Make sure that it's actually based on symptoms, not just your assumptions - most blind people don't wear sunglasses, not all people with SCI use a wheelchair, upper limb prosthetics aren't nearly as useful as you think. Decide which ones your character could have, how often they would use them, and if they switch between different aids.

Basically all of the above aids will have subtypes or variants. There is a lot of options. Does your character use an active manual wheelchair, a powerchair, or a generic hospital wheelchair? Are they using high-, or low-tech AAC? What would be available to them? Does it change over the course of their story, or their life in general?

If relevant, think about what treatment your character might receive. Do they need medication? Physical therapy? Occupational therapy? Orientation and mobility training? Speech therapy? Do they have access to it, and why or why not?

What is your character's support system? Do they have a carer; if yes, then what do they help your character with and what kind of relationship do they have? Is your character happy about it or not at all?

How did their life change after becoming disabled? If your character goes from being an extreme athlete to suddenly being a full-time wheelchair user, it will have an effect - are they going to stop doing sports at all, are they going to just do extreme wheelchair sports now, or are they going to try out wheelchair table tennis instead? Do they know and respect their new limitations? Did they have to get a different job or had to make their house accessible? Do they have support in this transition, or are they on their own - do they wish they had that support?

What about *other* characters? Your character isn't going to be the only disabled person in existence. Do they know other disabled people? Do they have a community? If your character manages their disability with something that's only available to them, what about all the other people with the same disability?

What is the society that your character lives in like? Is the architecture accessible? How do they treat disabled people? Are abled characters knowledgeable about disabilities? How many people speak the local sign language(s)? Are accessible bathrooms common, or does your character have to go home every few hours? Is there access to prosthetists and ocularists, or what do they do when their prosthetic leg or eye requires the routine check-up?

Know the tropes. If a burn survivor character is an evil mask-wearer, if a powerchair user is a constantly rude and ungrateful to everyone villain, if an amputee is a genius mechanic who fixes their own prosthetics, you have A Trope. Not all tropes are made equal; some are actively harmful to real people, while others are just annoying or boring by the nature of having been done to death. During the character creation process, research what tropes might apply and just try to trace your logic. Does your blind character see the future because it's a common superpower in their world, or are you doing the ancient "Blind Seer" trope?

Remember, that not all of the above questions will come up in your writing, but to know which ones won't you need to know the answers to them first. Even if you don't decide to explicitly name your character's condition, you will be aware of what they might function like. You will be able to add more depth to your character if you decide that they have T6 spina bifida, rather than if you made them into an ambiguous wheelchair user with ambiguous symptoms and ambiguous needs. Embrace research as part of your process and your characters will be better representation, sure, but they will also make more sense and seem more like actual people; same with the world that they are a part of.

This post exists to help you establish the basics of your character's disability so that you can do research on your own and answer some of the most common ("what are symptoms of x?") questions by yourself. If you have these things already established, it will also be easier for us to answer any possible questions you might have - e.g. "what would a character with complete high-level paraplegia do in a world where the modern kind of wheelchair has not been invented yet?" is much more concise than just "how do I write a character with paralysis?" - I think it's more helpful for askers as well; a vague answer won't be much help, I think.

I hope that this post is helpful!

Mod Sasza

#mod sasza#writing advice#writing reference#writeblr#writing resources#writing disabled characters#writing resource#long post#writing tips#writing guide

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's talk about transitions.

Transitioning between fast-paced and slow-paced scenes is essential for maintaining the flow of your narrative and keeping readers engaged throughout your story, allowing for moments of reflection, introspection, and character development.

Here are some strategies to smoothly transition between different pacing levels:

Use scene endings and beginnings: End a fast-paced scene with a cliffhanger or revelation that propels the story forward, then transition to a slower-paced scene that allows characters (and readers) to process the events. On the flip side, begin a slow-paced scene with a hook or question that intrigues readers and draws them deeper into the story.

Bridge paragraphs: Include bridge paragraphs between scenes to provide a smooth transition. These paragraphs can briefly summarize the previous scene's events, set the scene for the upcoming events, or transition between different settings, characters, or points of view.

Change in tone or focus: Shift the tone or focus of the narrative to signal a change in pacing. For example, transition from a tense action scene to a quieter moment of reflection by shifting the narrative focus from external events to internal thoughts and emotions.

Utilise pacing within scenes: Even within a single scene, you can vary the pacing to create transitions. Start with a fast-paced opening to grab the reader's attention, then gradually slow down the pacing as you delve deeper into character interactions, dialogue, or introspection. Conversely, speed up the pacing to inject energy and excitement into slower scenes.

Symbolic transitions: Use symbolic elements within the narrative to signal transitions between pacing levels. For example, transition from a fast-paced scene set during a stormy night to a slow-paced scene set in the calm aftermath of the storm, mirroring the shift in pacing.

Foreshadowing: Use subtle foreshadowing in fast-paced scenes to hint at upcoming events or conflicts that will be explored in slower-paced scenes. This creates anticipation and helps to smoothly transition between different pacing levels by maintaining continuity in the narrative arc.

Character reactions: Show how characters react to the events of fast-paced scenes in the subsequent slower-paced scenes. Use their thoughts, emotions, and actions to provide insight into the impact of these events on the story and its characters, helping to bridge the transition between pacing levels.

See my post on pacing for more! ❤

Previous | Next

#writeblr#writing#writing advice#writing resources#writing tips#writing help#transitions#pacing#plot development#creative writing#deception-united

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

5 Tips for Creating Intimidating Antagonists

Antagonists, whether people, the world, an object, or something else are integral to giving your story stakes and enough conflict to challenge your character enough to change them. Today I’m just going to focus on people antagonists because they are the easiest to do this with!

1. Your antagonist is still a character

While sure, antagonists exist in the story to combat your MC and make their lives and quest difficult, they are still characters in the story—they are still people in the world.

Antagonists lacking in this humanity may land flat or uninteresting, and it’s more likely they’ll fall into trope territory.

You should treat your antagonists like any other character. They should have goals, objectives, flaws, backstories, etc. (check out my character creation stuff here). They may even go through their own character arc, even if that doesn’t necessarily lead them to the ‘good’ side.

Really effective antagonists are human enough for us to see ourselves in them—in another universe, we could even be them.

2. They’re… antagonistic

There’s two types of antagonist. Type A and Type B. Type A antagonist’s have a goal that is opposite the MC’s. Type B’s goal is the same as the MC’s, but their objectives contradict each other.

For example, in Type A, your MC wants to win the contest, your antagonist wants them to lose.

In Type B, your MC wants to win the contest, and your antagonist wants to win the same contest. They can’t both win, so the way they get to their goal goes against each other.

A is where you get your Draco Malfoy’s, other school bullies, or President Snow’s (they don’t necessarily want what the MC does, they just don’t want them to have it.)

B is where you get the other Hunger Games contestants, or any adventure movie where the villain wants the secret treasure that the MCs are also hunting down. They want the same thing.

3. They have well-formed motivations

While we as the writers know that your antagonist was conceptualized to get in the way of the MC, they don’t know that. To them, they exist separate from the MC, and have their own reasons for doing what they do.

In Type A antagonists, whatever the MC wants would be bad for them in some way—so they can’t let them have it. For example, your MC wants to destroy Amazon, Jeff Bezos wants them not to do that. Why not? He wants to continue making money. To him, the MC getting what they want would take away something he has.

Other motivations could be: MC’s success would take away an opportunity they want, lose them power or fame or money or love, it could reveal something harmful about them—harming their reputation. It could even, in some cases, cause them physical harm.

This doesn’t necessarily have to be true, but the antagonist has to believe it’s true. Such as, if MC wins the competition, my wife will leave me for them. Maybe she absolutely wouldn’t, but your antagonist isn’t going to take that chance anyway.

In Type B antagonists, they want the same thing as the MC. In this case, their motivations could be literally anything. They want to win the competition to have enough money to save their family farm, or to prove to their family that they can succeed at something, or to bring them fame so that they won’t die a ‘nobody’.

They have a motivation separate from the MC, but that pesky protagonist keeps getting in their way.

4. They have power over the MC

Antagonists that aren’t able to combat the MC very well aren’t very interesting. Their job is to set the MC back, so they should be able to impact their journey and lives. They need some sort of advantage, privilege, or power over the MC.

President Snow has armies and the force of his system to squash Katniss. She’s able to survive through political tension and her own army of rebels, but he looms an incredibly formidable foe.

Your antagonist may be more wealthy, powerful, influential, intelligent, or skilled. They may have more people on their side. They are superior in some way to the protagonist.

5. And sometimes they win

Leading from the last point, your antagonists need wins. They need to get their way sometimes, which means your protagonist has to lose. You can do a bit of a trade off that allows your protagonist to lose enough to make a formidable foe out of their antagonist, but still allows them some progress using Fortunately, Unfortunately.

It goes like… Fortunately, MC gets accepted into the competition. Unfortunately, the antagonist convinces the rest of the competitors to hate them. Fortunately, they make one friend. Unfortunately, their first entry into the competition gets sabotaged. Fortunately, they make it through the first round anyway, etc. etc.

An antagonist that doesn’t do any antagonizing isn’t very interesting, and is completely pointless in their purpose to heighten stakes and create conflict for your protagonist to overcome. We’ll probably be talking about antagonists more soon!

Anything I missed?

#writing#creative writing#writers#screenwriting#writing inspiration#filmmaking#writing community#books#writing advice#antagonists#film#writing antagonists#villains#5 tips for creating intimidating antagonists

2K notes

·

View notes