Text

Consider:

Victorian England: 1837-1901

American Old West: 1803-1912

Meiji Restoration: 1868-1912

French privateering in the Gulf of Mexico: ended circa 1830

Conclusion: an adventuring party consisting of a Victorian gentleman thief, an Old West gunslinger, a disgraced former samurai, and an elderly French pirate is actually 100% historically plausible.

173K notes

·

View notes

Text

Some more recent commissions I've done 😊

Commission Info

Patreon

132 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Covers by Larry Rostant.

==========

Today, rather than reviewing David Alan Mack's three Dark Arts novels (The Midnight Front, The Iron Codex, and The Shadow Commission), I have elected to instead do an analysis of what is known regarding some of the less-explained elements of the supernatural systems underlying his secret history series, especially those that are not fully explained in the glossaries or on his website. To simplify, angels and demons will be called "Presences" for their overall designation.

For more information regarding the terminology of for the practice of magick within the series, see the pages for generalized information and the glossary. To learn more about Black Magick affiliated with the powers of Hell, see the Infernal Hierarchy and a list of demons. To look into the less common White Magick associated with Celestial powers of Heaven, see the Celestial Hierarchy and a list of most, but not all, angels present in the story.

In referencing individual angels or demons, their names will be listed entirely in capital letters, much like how they are presented within the novels and by David Alan Mack in external communications. Furthermore, the word "magick" will be capitalized when referring to one type or another, and the words "karcist" and "magician" will be relatively interchangeable, as they were in the third novel.

Disclaimer: Mentions of various entities within this analysis do touch on real-world religions, but are not to be taken as opinion on the matter beyond basic objective commentary on the story as it is presented in the novels.

==========

As a note: There are other systems presented within the story, primarily through general mentions, such as "Wūshi of the ancient Chinese way, Arctic shamans, [and] doctors of the African Rites" (colloquially known as "witch doctors" in common parlance), is has been confirmed that they are still working with the same Presences, just through different names and rituals.

This approach has precedence in the books, particularly in The Iron Codex's examination of the creation myth of The Mystery of the Dead God. Cultures across centuries and countries, each of them with their own cultures, all contribute to the same story of creation. The range is pretty extensive, as can be seen chronologically in Cade Martin's examination: roughly 3000 BCE Egypt, 1700 BCE Babylon, 1000 BCE Zhou dynasty China, ninth century BCE Greece, 800 BCE Judea, and third century BCE Maya, each of which would have had completely different ways of using magick to learn of the mystery.

In terms of practitioners of these non-Eurocentric methods of the Art, there are at least two culturally distinct examples deliberately shown.

First, there is the Vate Pythia, the last Oracle of Delphi, who works in prophecies and can call out to individual people who are in need of and deserving of her aid. The way that she functions seems to follow an ancient Greek form of magick, one of divine inspiration rather than yoking demons or angels into one's body or calling on them in the same ways as modern European karcists. She also appears to still worship the old gods, mentioning Chronos, the Greek god of time.

Second, there are the uses of Kabbalah, a form of Jewish mysticism. In The Iron Codex, they are alluded to in that they apparently work with White Magick in ways that would enable them to translate the eponymous codex of magickal knowledge. In The Shadow Commission, a user of magick under the employ of Mossad sends a golem, a nigh-indestructible assassin, after a former Nazi agent in the United States, with its sheer durability and the method of its defeat directly referencing the way in which the most famous story of a golem in Jewish folklore was shut down (by turning the "Truth" word on its forehead to "Death" by removing one of the Hebrew letters). This more hostile usage of Kabbalistic magick is likely their "Black Magick" variation, Sitra Achra.

==========

The nadach and the nikraim are, respectively, mortals who have had their soul bound with that of a particular demon or angel, boosting their magickal power significantly. While these can occur naturally from birth, as in the case of the sole known nadach in the story and one of the two nikraim examples, certain rituals can be called forth to artificially invoke that connection to create a powerful magick user from a normal person, with powers as strong as the Seraphim. While these people are not immortal by any means, they are known to handle yoking demons or angels with less strain, with those naturally formed doing so with less need to indulge in distractions such as drug abuse than those who are created artificially.

As an added bonus, those who are fused by soul with the infernal or the holy seem capable of utilizing specific supernatural powers even without yoking a single spirit. The nadach who was bound to LEGION proved capable of splitting his consciousness into three distinct beings, and perhaps more given sufficient the time and practice. The natural nikraim in the books was capable of using an unnamed angel's abilities to project her thoughts telepathically to animals in her vicinity, nudging them to act in her favor, though not directly hearing them in response. The artificial nikraim had a more unusual gift supplied by the Seraph GESHURIEL, namely that of being able to yoke a tremendous amount of demons without being driven to madness, along with his ability to read proto-Enochian, "the language of angels in the epoch before the Fall," with relatively little difficulty compared to many others, to the point that it was described as "preternatural ease" by an onlooker. However, that one still felt weaker than the natural nikraim.

==========

There are some particulars about the Pauline Art (as opposed to the Black Magick "Goetic Art" of working with demons) that help to distinguish itself pretty extensively from the primary magick used during World War II (and, for that matter, apparently beforehand in Europe). First, let us go into the etymology of the two terms, each of which are named for books in The Lesser Key of Solomon, a five-volume grimoire on demonology compiled in the mid-17th century from materials that preceded it by several centuries.

The "Goetic" Art is named for (arguably) the most famous of the aforementioned books, the first named Ars Goetia. As it so happens, "Goetia" is also a term for a form of magick that includes the conjuration of demons.

The "Pauline" Art is named for the third of the volumes, Ars Paulina, itself named for Paul the Apostle who is purported to have communicated with heavenly powers. This two-book work encompasses the twenty-four angels aligned with the fwenty-four hours of the day and the three hundred sixty spirits of the degrees of the zodiac.

As Pauline magicians are bound by oaths of non-interference with the machinations of Black Magick karcists by the inter-order "Covenant," they tend to restrict their interactions with the Divine to remotely viewing actions, divining the future, healing the wounded, and defending with a variety of magickal shields. Only those who breach the boundaries and decide to become gray magicians such as Father Luis Pérez. Whether or not this is true for other traditions of magick is unclear, or if it is restricted to the White Magick side of the Eurocentric model.

==========

As stated in the general analysis of magick, yoking angels is much harder than their fallen counterparts, with the one calling for them needing to be granted the favor of the Divine and to beg of the Celestial forces, rather than invoke demands in accordance with a pre-existing pact, on account of angels still having the link to the Divine and the will behind it rather than not having that will as demons. In fact, there are no defined pacts linking humans to any one angelic patron when using White Magick, meaning that multiple distinct highly-ranked angels capable of being called upon at any one time, or even all at once.

Although not entirely unique to the Celestial side of the Art as shown in the novelette “Hell Rode With Her,” there seems to be an added focus on taking up the powers of one or several of the seven archangels and utilizing their powers in a manner similar to that of yoking demons into a karcist's body. As some notable examples, there has been the use of MICHAEL and URIEL's swords and GABRIEL's shield.

The organization of angels makes for a very different kind of chess game regarding how to defend against any one Presence. There do appear to be "dukes" affiliated with individual higher powers, as is mentioned in the aforementioned Ars Paulina itself. One example was the yoking of DAROCHIEL, BENOHAM, and MALGARAS after asking permission from the archangel SAMAEL, and another was the yoking of that of HAMARIEL after asking it of ABASDASHON, who has notably not been directly identified as an archangel in the novel nor the associated website. Specific Orders of these angels are not always described, but those who are called upon to seek aid from another angel seem to primarily be of the upper Orders. According to dialogue in The Shadow Commission, even if one were to exclude one of the seven archangels who likely take up a great many of the Presences, there are still dozens of alternative protective barriers that can be made.

Owing to the lack of contracts, and perhaps to some other oddities, it appears that specific angels can be called upon for protection against harm except for those weapons that bear the sigil of the protecting angel. While this is not entirely unique to angels, especially given its prominence throughout the novels on the demonic side, demons only appear to be used for defensive sigils of individual patrons, one of six apparent options.

One particular "trap" is known for those who use White Magick: the angel's snare, a version of a "devil's trap" used for angels rather than demons. Those who are caught within its binds when it is invoked are rendered paralyzed so long as they hold on to the Celestial Presences within. The arcane sigil itself is formed with proto-Enochian script, the language from before the demons' fall from grace.

A variety of powers provided by angels are known even outside of individually named ones, even barring those already mentioned above. While magickal injuries are difficult to heal, if not impossible, the power of an angel can be used to draw the dwindling life force from one person and apply it to another, saving one life at the expense of the one from which said life was taken. Blasts of pure light are a fairly standard use of angelic power that is easily associated with their kind.

Another relatively common ability is the use of holy fire, which appears to take the form of invisible or white-hot tongues of flame rather than the blues, greens, and perhaps other colors associated with hellfire. This form of fire seems to be more versatile than the nearly always destructive hellfire, with uses such as the conjuration of weapons, beams from the eyes, a breath of flame, and even usage in conjunction with other angels to create temporary flames for torturing the infernal powers or banishing spirits and demonic sigils.

The usage of the Sight, identified by Mack as "full-spectrum vision, including perception of invisible or magickally concealed persons and things," is different from that of Black Magick karcists. According to those viewing users of the Pauline Art, said vision takes the form of green flames replacing the eyes, or the eyes themselves seeming to "flicker" in some way to see what is hidden.

In terms of teleportation, some White magicians may be capable of teleportation, be it through a "thunder jump" in a bolt of lightning from one location to another (seemingly only through single use in at least some angels), or by summoning enormous, feathered angel wings to near-instantaneously move to another person, take hold of them, and transport themselves to another, safer location.

One of the most potent uses of White Magick in the series is the use of something identified as a "spirit hammer," a way to sever the bonds of all of the yoked spirits of a Black Magick karcist (though perhaps not a White Magick one; unproven one way or the other) from a distance by invoking an exorcism rite, with this ability only able to be utilized once before the angel ascends back to Heaven.

Certain angels can be called upon to let loose individual spells, much as demons probably can be used to the same effect, each of which have their incantations stated in Latin. While the most common incantations beyond the experiments to yoke demons or angels that are shown in the series are for exorcism, there is at least one case of a spell cast that is deliberately mentioned as tied to an individual angel, namely MARBAS, which has its incomplete incantation translate to "Spill blood."

==========

In The Shadow Commission, an intriguing magickal artifact is brought up, one that invites another wrinkle into the overall system: phylacteries. The original phylacteries are derived from Jewish folklore, more commonly known amongst the religion as tefillin. They are a set of small black leather boxes containing scrolls of parchment inscribed with verses from the Torah, and are worn by observant Jews during weekday morning prayers on the forehead and one palm.

In fantasy, including in this magical system, they are more often a container to hold someone's soul, allowing them to live continuously and often not age at all unless the container is somehow destroyed. Destruction of the phylactery can cause instantaneous acceleration of the soul owner's age to befit their chronological age.

In The Shadow Commission, at least one member of the eponymous group, along with probably the rest as well, has one of these artifacts, and it is known to be a particularly powerful one. It is described as thus:

It was a bottle of hand-blown lavender crystal, its body broad at the base and tapering at the top to meet a long and narrow neck. The surface of the bottle was etched with eldritch sigils, many of which Anja recognized as Enochian, the language of the angels. A fine metallic mesh had been woven around the bottle, a delicate web of precious metals pulled into hair-thin filigree. Sealing the bottle was a long cork secured with an abundance of tightly wrapped steel wire.

The use of Enochian, the language of angels, rather than proto-Enochian, helps to figure out that the means of producing a phylactery are likely infernal in origin, as said language is used in Black Magick experiments extensively, as opposed to the proto-Enochian for White Magick.

These devices are evidently extremely volatile, as a blast that was capable of destroying it caused the artifact to let loose all of its energy very explosively, to a degree similar to a very strong hand grenade, or even stronger, capable of dealing lethal damage even to an accomplished nikraim.

The most interesting element of phylacteries, by far, is the fact that, according to the owner of the one known, the soul within does not need to be that of an actual magician. The owner was not a user of any form of magick beyond that which he hired from elsewhere, but still had a phylactery, and the same can be said of the various members of the Commission, showing that one does not need to have extensive power with magick directly to be able to have a serious impact on its use and prevalence as the centuries continue ever onward.

#the dark arts#the dark arts series#dark arts series#david alan mack#david mack#Tor Books#magic analysis#magick analysis#ars goetia#ars paulina#the midnight front#the iron codex#the shadow commission#hell rode with her#nadach#nikraim#angel#demon#angelic magic#demonic magic#kabbalah#black magic#black magick#karcist#white magic#white magick#archangel#archangels#religious magic#magic religion

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

With "Black Star Renegades," @michael-moreci set up a fascinating world of science fantasy in the vein of Star Wars or any number of hero's journeys. Cade Sura and his allies were coming into their own in a story that takes a bit from Star Wars: A New Hope.

With We Are Mayhem, he kicks things up a notch in a huge way. More than just Cade's journey, this is the tale of a group of friends who all have their own reasons for doing what they do, and an interlocking chapter structure, split between Cade and his friend/girlfriend Kira helps to showcase different aspects of the society, from the ace pilot war action to the Jedi-esque adventures of Cade himself. As the perspective switches, the chapters do, meaning that the stories dovetail into a cohesive whole that works marvelously together. If "Black Star Renegades" is "A New Hope," then "We Are Mayhem" is a combination of both "The Empire Strikes Back" and "Return of the Jedi."

None of this is to say it is entirely derivative by any means. The way the magic works is extremely enticing, taking cues from the Force, but taking those cues far beyond even what Star Wars ever did. There is a dark and a light path, but rather than just concentrating on the dark, there is emphasis on what the light is capable of (rather than just on dark and neutral), an emphasis that is essential to the way in which the story functions.

The character beats are fantastic, from Wu-Xia the enlightened yet retired warlord; to Percival, the sarcastic, irritable mentor; to Lux Ersia the teenaged Queen (from whom readers can glean a lot of influence off of "Dishonored"'s Empress Emily Kaldwin I, another character Moreci has written for in the past).

The story seems to be over, but who knows? The worlds open to the Rokura and its masters have a long way to go, both backward and forward across the timeline of the duology, so perhaps we can, some day, hope for more from such an excellent story.

#black star renegades#we are mayhem#cade sura#Michael moreci#star wars#science fiction#science fantasy#dishonored

0 notes

Photo

Cover by Yoshioka.

Today I'll be reviewing "Bloodborne" #11, the mostly silent issue that takes up the third part of four to the 'A Song of Crows' arc of the ongoing comic series based on the FROM Software video game Bloodborne. The comic is written by @aleskot, illustrated by Piotr Kowalski, colored by Brad Simpson, and lettered by Aditya Bidikar, published by @titancomics.

"You are granted eyes."

These are the only four words in the entirety of the narrative for "A Song of Crows, Part 3 of 4." However, their meaning is all too evident to fans of Bloodborne. Being "granted eyes" means to gain Insight, a type of eldritch knowledge which can be very dangerous. While it does allow one to see things that they otherwise would not, including entities that will seek harm upon the bearer, Insight also increases the potential for "frenzy," a state of madness in which the user causes him or herself harm. Furthermore, if one is not careful with their own insights, they can end up like the babbling mad Micolash, Host of the Nightmare or the virtually catatonic Provost Willem.

None of this is to say that a lack of Insight is a good thing either, as it can lead to a different kind of bestial state, but careful management is key.

In the context of the issue, the statement is connected to Eileen the Crow, famous among players as the Hunter of Hunters, who somehow makes contact with Rom the Vacuous Spider at the Moonside Lake. It is unclear if she is actually the Hunter of Hunters yet, given that the Caryll Rune at the start of the issue, similar to others in the arc and the ones in the preceding "The Healing Thirst" arc, is that of "Communion" which relates to the Healing Church, rather than her own Covenant's one of "Hunter," but perhaps she became that vigilante persona later, or perhaps the rune designation is irrelevant to the arc, despite other arcs having different runes each.

Without any other words aside from the aforementioned four, which are at the closing moments of the issue, the creative team together shows an utterly deranged state of mind. It is difficult to say where the choices were made by Aleš Kot versus where they were made by Piotr Kowalski or Brad Simpson, but taken together, the whole is certainly not meant to show any form of true stability, and likely meant to enhance confusion.

Water is a key factor in the imagery, as it would be based on both the fact that Rom lives within the lake and the fact that much is made of the themes revolving around water much like another famous eldritch mythos. The fact that one of the first images after witnessing Eileen staring into one of Rom's many eyes is that of a crow's eye bursting open and the intraocular fluid flowing freely from the socket does not go unnoticed, and serves as a hint to the sheer madness to come.

Repetition is rampant throughout the pages, from very slight alterations from one panel to another to showcase slowed perceptions to outright repeated imagery. In two separate double-page spreads, there is a set of panels that completely mirror one another as if to show a twisted perception of all of it as things change or stay the same. What is happening with the ritual involving the sacrifice of some kind of animal, perhaps a cow, over a young child's supine form? Is the imminently approaching blood moon rising or setting? What is Rom looking for or at? Is Eileen even standing upright, or is she horizontal?

Eventually, the images settle somewhat, and the image of the child, who remains in grayscale despite the colors around, comes toward Eileen, only to run off toward the distant Byrgenwerth College shortly thereafter across what appears to be the surface of the water. Despite Rom seemingly hovering about her, and despite the memory of what was seen regarding said child, Eileen follows, the path suddenly covered in fresh snow, with the trail of footsteps seemingly leading her around to the left of the entryway to the abandoned institution. Cue the four words listed above.

What has happened? How much was real? How much can we rely upon Eileen's own perceptions? Does it even matter, given the madness all around her? This issue raises far more questions than it answers, but with the bizarre imagery and the near complete silence, it is a worthy experiment and one of the most interesting issues of the series to date.

#bloodborne#bloodborne comic#a song of crows#bloodborne a song of crows#bloodborne: a song of crows#ales kot#piotr kowalski#brad simpson#aditya bidikar#from software#fromsoftware#titan comics#titan entertainment#eileen the crow#hunter of hunters#caryll runes#byrgenwerth college#byrgenwerth#rom the vacuous spider#yoshioka

0 notes

Photo

Today, rather than writing a review, I will be going through an analytical approach to a certain element of Focus Home Interactive and Asobo Studio's A Plague Tale: Innocence.

Be fairly warned: spoilers follow regarding the latter half of the game.

The element being examined is the Prima Macula, known through the game as the blood-borne connection that Hugo de Rune and others before him have to plague-bearing creatures, most notably feral rats, enabling them to exert telepathic control over the creatures to manipulate movements in their frenzy, as well as being able to see into their minds on some level to sense them when they are near.

According to a brief exchange with Narrative Director Sébastien Renard, it seems entirely possible that while the Prima Macula in 1348 France has concentrated control over rats that spread the bubonic plague, previous wielders (and subsequent ones) may have had control over other creatures declared as vermin. To use his words exactly, "Well, swarms of animals have always be a tradition among plagues, such as in the Plagues of Egypt. I can only say that our version is the rats, and let you imagine what you'd fear more :) (yet in France today, it would definitely be mosquitos! :D)"

If taken to its logical conclusion, plenty of animals could be controlled, from birds to insects to much more. Similar to the plague rats of the original Dishonored being comparable to the bloodflies of Dishonored 2 in function for an epidemic-ridden society and how someone developing their powers in one era or another would be connected to their own time and place's source of infestation, users of the Macula in other time periods could utilize their power over infected creatures to perform acts like creating a temporary artificial darkness in the form of thousands or even millions of insects or birds (if they are not afflicted with the same light sensitivity as the rats), capsize and sink watercraft through fish, or even control larger land animals than the waves upon waves of rats encountered by the de Rune children and their friends.

Similarly, the locations where said animals live would be drastically different. The gore-filled tunnels of the rats are a hint of the kind of macabre living spaces these creatures live within, but what if they were in trees as nests, or otherwise lying in wait in places at a significant height that would make it harder to spot them until it is too late?

That said, all of this may be completely inaccurate. The main element that may make this speculation invalid is a look at the historical pathology related to the Prima Macula as known within the story. Research in-game places the earliest known account of the hosts for the Prima Macula at the time of the Plague of Justinian (541-542 CE) in the Byzantine Empire, a disease that has been since confirmed as originating from the same bacteria (Yersinia pestis) as the aforementioned Black Plague (1347-1351 CE), and thus all fitting under the collective label of "plague" in terms of epidemics.

If Mr. Renard's denotation of the Macula as for "plagues" rather than all epidemics is accurate and not just a general colloquialism, then the applicability of when and how this type of power is used would be greatly limited, mostly just to rats and perhaps fleas, as there does not seem to be direct control that bearers of the Macula have over species that are infected by said rats. However, none of this is to say that the spread of the Macula would be too inherently limited. There have been many plagues throughout history, numbering greater than forty.

The existence of such a significant element as the hosts of the Prima Macula give rise to the idea of how it could potentially alter the way in which society develops if it were to be known to higher authorities, as demonstrated by Vitalis Bénévent's goals within the game itself. First it seems prudent to go over what is known about how to control the Macula.

Control over the Prima Macula relies upon certain "thresholds" through which the host experiences a lot of pain until their body can become accustomed to the power, coupled with symptoms such as times of significant weakness and some rather high fevers. Certain alchemical concoctions are capable of controlling these thresholds, such as the ones used by Béatrice de Rune and her fellow alchemist Laurentius, but only with the help of the large book known as Sanguinis Itinera ("Voyages of the Blood") was such an elixir completed. Another component important to the Macula's progress appears to be internal, related to moments of intense emotion such as heightened fear or anger, but these elements can be worked through by having someone close by to manage said fears, and are much less important once the host passes the final threshold to the point of being able to control the rats, which also appears to allot a kind of passive immunity to the plague itself through rats' unwillingness to attack said host. Whether or not this type of issue would be a significant problem for people who are older than the five-year-old Hugo is unknown, but perhaps it is a recurring element.

As shown by the alchemical works within the Inquisition, some other scientific means have been used to transmit the Prima Macula. A blood transfusion from one who has a hereditary form of the Macula to someone who does not grants a connection through their blood. The artificial host is granted power over the infected creatures at the same rate as the natural host, even crossing the thresholds in tandem. Whether or not artificial hosts suffer from the same debilitating effects as those for natural ones is unknown, but as shown by Hugo de Rune's transfusion to Vitalis Bénévent and the eventual boss battle, not only is the natural host able to sense the Macula within the artificial one, but he or she is also capable of understanding if the Macula, which appears semi-sentient (unless Hugo is wrong) is "fighting" the artificial host in some way to prevent the use of power.

Certain elements, such as the "exsanguis" substance procured from rat-infested locations and the resultant "odoris" alchemical substance utilized to draw rats into one area or another, help to give the impression of non-carriers of the Macula having some defense nonetheless, albeit one that is rather dangerous to procure and utilize. Similarly, the specially treated white rats, which respond only to Vitalis and not to Hugo, along with being immune to bright lights or fire, show another way of controlling the use of the ability itself.

All of these elements come to a head when thinking about the implications for said developments going forward.

In terms of developments to society, such scientific works could be used to manage or even neutralize the effectiveness of potential hosts of the Macula, especially with the increase in scientific knowledge since the 14th century CE. For instance, if such a serum were created, it could help to keep such a horrific superhuman from emerging, or conversely be even worse and attempt to heighten emotional extremes to keep them down with their own sickness. Neither of these are benevolent options, to be clear, but both seem within the realm of possibility for the game.

Through the experimentation of Vitalis Bénévent, it is shown that while there are drawbacks (even excluding the difficulties with blood transfusions in general), it is entirely possible that people could create more carriers of the Macula while keeping the natural hosts safely away. Between the transfusion technique and the unusual white rats, plague-based officers are entirely within the realm of possibility for the later years or centuries of the story's narrative.

Meanwhile, elements like exsanguis and odoris show how society could develop other means to control the infected creatures through a variety of inventions to redirect or otherwise neutralize them even outside of common exterminators or plague vaccines. Together with the aforementioned officers, not to mention more positive uses such as redirecting plague vectors away from population centers to limit infection, there is an enormous amount of potential at work.

Of course, all of this could be for naught, as it is not clear whether or not A Plague Tale: Innocence will have any further stories in its universe, but much like another disease-related game published by Focus Home Interactive, Vampyr, all of this serves as an interesting thought for what could potentially exist moving forward.

#focus home interactive#focus home#a plague tale#a plague tale innocence#a plague tale: innocence#hugo de rune#vitalis benevent#sebastien renard#asobo studio#vampyr#prima macula#analysis#exsanguis#odoris#inquisition#plague#epidemic#dishonored#dishonored 2

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cover by Bethesda Softworks and Arkane Studios.

Today I’ll be reviewing the third (and so far final) installment in Adam Christopher’s Dishonored novel trilogy, following Dishonored: The Corroded Man and Dishonored: The Return of Daud, in addition to following its relatively immediate predecessor Dishonored: Death of the Outsider in the games and tying into the comic bridging story Dishonored: The Wyrmwood Deceit. Chronologically, this story is the last in the Dishonored timeline thus far, for reasons that will be readily evident.

The book was published by Titan Books of Titan Entertainment.

A lot has changed in the Empire of the Isles since the fall of the Outsider in 1852. His removal from his place at the Ritual Hold fundamentally altered the nature of magic, and the world itself is breaking down by degrees as the Void moves apart from the “real” world.

The fracturing of magic has driven the Abbey of the Everyman to the point of needing to be abolished by Empress Emily Kaldwin the Wise, with the men of the Overseers and the women of the Oracular Order driven against one another, resulting in the surviving Overseers being driven into poverty, and the Oracles driven off and/or killed in witch hunts, the latter of which are not under the control of the Empress at all.

Following the fall of Delilah Copperspoon’s usurping government, Alexandria Hypatia’s recall of her invention the Addermire Solution seems to have ultimately resulted in no form of the elixir being produced anywhere at all, presumably on account of the side effects of said drink when taken in high doses. Said side effects seem to include addiction, given the disposition of one former Overseer. As such, this explains why there is no restorative for mana in Death of the Outsider.

With the Outsider gone, there is little to keep the world stable. While Billie Lurk was able to see “hollows” in the fractures between worlds, things have gotten much worse since then, to the point of rips in the fabric of reality itself that Lurk calls “rifts.” Far more dangerous than the hollows, these tears can make travel impossible from one point to another, and in the case of Morley, were involved in the “Crisis,” better known as the “Three-Day War” between Queen Eithne and King Briam that ravaged the country and the city of Alba in particular.

What exactly happened to the Outsider is deliberately unclear, but some inferences can be made. The text avoids actually saying that the Outsider is dead or was killed, using terms like “fell” and “gone” instead. While this word choice on its own might just be an implication that anything is possible, there is one added piece of the puzzle. In Death of the Outsider, if Billie Lurk kills the Outsider instead of freeing him from the Void and giving him back his life and his name, she tells the ghost of Daud that “The world might change, but we won’t. Killers never change,” continuing on in the conclusion that “after all this, I’m still just a murderer.” That kind of fatalistic attitude is not present in the novel’s Billie, who seems to have done her best to move past her failures. To paraphrase a certain character from Brandon Sanderson’s Oathbringer, the world cannot have her pain, and her every movement forward indicates a refusal to allow her past to dictate her future. In all, her ability to move forward seems to indicate that the boy who was once the Outsider is still alive, but that Billie has told not a single soul what happened that day in the Ritual Hold between her, the god in human form, and Daud.

On another note, Martha Cottings finally has her arc paid off, one first set up with the original appearance of the post-prostheses Billie Lurk back in late 2016’s The Wyrmwood Deceit. It’s a small thing, but still good to know where that was going.

"The Outsider had fallen, and the Void had become unmoored from the world—but it was still connected to it. It still existed, but its relationship with the world was different. Somehow, that had changed the way magic worked. That change had driven the Overseers and the Sisterhood to moonstruck oblivion, and had affected Billie’s black-shard arm and the Sliver."

Predictably, removing the focal point from the magic system has resulted in a serious shift in the way in which magic actually works. Although this change was alluded to in The Return of Daud, having been implied in Death of the Outsider, this is the first time we see it in any sort of depth.

First and foremost, the most famous use of the Void, through the Outsider’s Mark. Given the Mark was a means to connect to the Outsider and share in his connection to the Void, those empowered in this way (in particular Emily Kaldwin and the possibly-alive-and-imprisoned Delilah Copperspoon) have lost their powers altogether, their connection to the supernatural power completely cut off. Whether or not the Mark itself has disappeared is unclear, but such a thing is largely irrelevant now given the revelation that it is the Outsider’s true name, especially with him gone.

"The world is broken around you, and you carry the scars. I wonder if you can live with that."

Important to the magic system is a new term that refers to what Billie has become: Void-touched. Individuals of this type are both a part of the Void and not, having an intricate, physical connection to both worlds that lasts beyond deposing the Outsider. Owing to that connection, magic still does flow to these persons, albeit in different ways that are more “standardized” than the specialization made possible by the connection to the Outsider himself. In the case of Billie, she can summon the Twin-bladed knife and can view through walls akin to Daud’s Void Gaze, in addition to seeing trails leading toward areas of high Void energy concentration, but her teleportation (Displace), mystical disguise (Semblance), power to strike with the power of the Void through her knife (Void Strike), and ability to see across vast distances (Foresight) are inaccessible.

Much like how Daud felt agony when he tried to empower himself with a rune in The Return of Daud, there are certain significant downsides to Billie’s abilities that last beyond the Outsider’s fall. Given that her powers still derive from the cognitive aspects of the Void, she has difficulty using said powers for the majority of the novel. Said difficulty comes from her insecurity with herself after the fall of the Outsider and the changes in the world, feeling she is too different to reconcile her own life’s experiences. Until she manages to accept that both she and the world are changing, but that change is just a part of life, she has a chance of not summoning her powers, but merely feeling agony. In essence, she has to realize that while the Void may be harder to grasp, given it is now further away, and given that this means that her powers will be weaker and slower to activate, she has to accept the world as it is and own her new identity for herself.

Certain runes, including those from Maximilian Norcross’s collection, have new characteristics, ones that can be replicated or otherwise utilized to act as a kind of “magical technology” bridge. The most overt use of these runes is the Leviathan Company’s teleportation to and from the Void Hollow, a location that has emerged in the space between the Void and the normal, “real” world and is more of a reflection of the real world with elements of the Void within, including the ambitious Leviathan Causeway. The runes allow one to transport through the aforementioned rifts, rather than just view them, and to teleport to any point within the Hollow as well. Other supernatural abilities are likely possible, but are not gone into depth about. Most notable is that these abilities can be used by anyone, including those without any connection to the Void before, so long as they have two of these runes in their possession and know how to use them.

The Void itself has had some major changes, as well as elements that existed before that are expanded upon. The most prominent is definitely the effects of the Void itself (including the Void Hollow) on unprotected individuals. Without proper protection akin to a mystical HAZMAT suit with certain specific runes, individuals will slowly find their flesh turn to stone, in an accelerated form of the transformation that the original members of the Cult of the Outsider underwent when becoming the “Envisioned.” To use a real life analogy, the Void seems to exude a kind of supernatural radiation that infects life from outside the Void itself, eventually turning victims into little more than shells of their former selves, incapable of interacting with others around them beyond fulfilling some relatively basic mystical commands such as grabbing someone or transporting them away.

Some of these cracks are in time itself, not unlike the fractured nature of time around Stilton Manor as seen in the Dishonored 2 mission “A Crack in the Slab.” As such, some entities like the Shadow (a mysterious Void presence tied to a particular conspiracy in Morley) and Billie Lurk herself can manipulate the rifts to travel to various points in time.

"I know more than most. I know that time is bleeding into itself around you. I know you have felt it, and you’re searching for the places where the world has broken against the Void."

Whereas many cannot make changes in time that will stick, others such as Billie can on account of having a physical presence in both the Void and the normal world. In a sense, Billie herself is a focal point around which time solidifies itself on account of her Outsider-given Void-connected prostheses, the cold black shard arm and the Sliver of the Eye of the Dead God, making her essentially the only person who can solve many of these problems.

On account of the increased use of the Void by mundane persons, there is an increased focus on certain physical elements present in the Void itself. One particular one that has been seen before but never thoroughly examined is the very Void stone that is common in locations of the Void, seemingly the same one that makes up the black shard arm: voidrite. On the mystical end, this material can be shaped into new artifacts, such as blades with mystical properties (such as one wielded by the aforementioned former Overseer Woodrow) capable of causing paralysis through some kind of self-harm ritual combined with a vocal incantation (“Eco, lazar, lapolay, yram.”) to paralyze a target until the spell is broken. On the mundane end, there are far more applications, including use as a volatile fuel source that can also negate gravity, allowing for the first air vehicles in the entire Dishonored franchise, along with giving some similarities to DC Comics’ Nth metal. One particular fact holds true for another use of voidrite: a weakness for Void-based entities. Much like how the Twin-bladed knife is lethal to Envisioned and even the Outsider himself, voidrite fuel can harm even monstrously enormous Void creatures when other sources cannot do a thing.

"I am here because you are different. The Void has found you through the cracks in your broken life. And when you cut me out of it, what will remain? What will you leave behind when you walk away?"

Technically speaking, Billie Lurk can be considered the most heroic and selfless character of the various Dishonored protagonists. Corvo Attano wanted to save his daughter and lover and in theory reclaim his good name. Emily Kaldwin wanted to save her father and reclaim her throne. Daud did perform a heroic act in The Knife of Dunwall and The Brigmore Witches, but only on the urging of the Outsider, and subsequently ignored any and all blame in any of his actions to the point of becoming a villain once more across The Return of Daud.

By contrast, Billie Lurk’s decision to look into the rifts is entirely on her own volition for the safety of the Isles and perhaps the entire world. Yes, she is the only one who can truly sense them and see what is wrong, but she had no outward obligation to do anything about them. By going out of her way to try to stop the madness, a problem she is well aware that she is responsible in part for causing in the first place, she proves she is better than Daud, something that his ghost admitted to her in his talk about her forgiving nature. From going to the Imperial Palace to try to solicit her friend Emily for help (a surprise, given it was unclear if they were even allies anymore, let alone friends), to going to the Academy of Natural Philosophy to use up Anton Sokolov’s remaining goodwill in a fruitless attempt to get the scientists to look into the rifts as anything but a meteorological phenomenon, to traveling to Morley on her own so as to help solve the problem of the rifts, everything involves her being the instigator. Even when she nominally is traveling to Morley to get evidence and support for Withnail Hugh Bruce Dribner’s experimentation with the Void rifts, she is the one in charge, considering she is the only one who could stop any of it on account of her borderline Schrödinger’s cat nature.

Her personality, as ever, leaves something to be desired in terms of her rudeness, but Adam Christopher manages to make her blunt, rude exterior and relationship with royalty absolutely hilarious, especially in how she deals with people trying to be overly polite with her in accordance with their protocols. Even her interactions with the borderline antisocial personality of the stoic Miles Severin are entirely reasonable, neither overly harsh (given circumstances) nor overly kind when dealing with his better sides. She is simply matter-of-fact and, to a point, highly manipulative, showing the darker sides of even the most heroic of people in the Isles owing to her upbringing.

“What will we do with the drunken whaler? What will we do with the drunken whaler? What will we do with the drunken whaler, early in the morning?”

Certain elements in the novel, on top of those in previous ones, give implications as to how this story may move forward into future games.

Voidrite is outright stated to be volatile, and able to expel an extraordinary amount of energy. Additionally, the substance is capable of sealing rifts, as it did with the one at the Leviathan Causeway, on top of being lethal to Void entities like the Shadow or Envisioned, but in powerful enough levels even able to face down fully realized Void gods like the Outsider himself. Said substance could be made into not only swords, but also projectile or placed weapons of untold power with a “poisoning” effect added on, primarily in the form of grenades or traps, but not excluding bolts nor bullets either.

Together, this could end up taking the balance of power shift away from the Void alone and more toward a more evenhanded use of power between magic and technology, a stance that had already begun under the creation of Jindosh’s clockwork soldiers and their ability to effortlessly take on the anti-witch Overseers. The fact that the anti-gravity properties of voidrite have made for the creation of flying machines within a year of the Outsider’s fall even further shows the rapid expansion of technological superiority without letting magic fall too far behind either. What other properties could this substance have? It appears that only the surface of its utility has been explored thus far.

In addition, the Voidrite infected seen at the Leviathan Causeway seem to be, in some ways, not dissimilar from the Weepers of Dishonored nor the Nest Keepers of Dishonored 2, with the “radiation” of the Void corrupting them by even faster degrees than the Envisioned. Adding to the ability to seal rifts, this set of facts sets up a possibility of a variation on the Gears of War “emergence hole” sealing mechanic for explosives to avoid incursions of the Void, or even to open them up in the first place to change the flow of battle.

The fact that the teleportation runes can be used to travel not only into the Void Hollow and out, but also across the other dimension to other locations in that parallel world, brings up the very real possibility of near-instantaneous intercontinental travel, allowing for incredibly fast invasions and, from a gameplay perspective, a reason for not only a fast-travel system in a series that is becoming increasingly open-world (especially in Death of the Outsider), but also for a far larger map including more of the Isles, and even a possibly more global conspiracy.

Adding to the possible globalization of the game, we have the other, rather familiar properties of the Void’s atmosphere, which bring to mind a host of hazardous materials with the use of a mystical HAZMAT suit. However, the sheer destructive power and heightened energy release bring particular focus on an analogy to nuclear power. Much like Edmund Roseburrow’s discovery of whale oil as a fuel source acted as an analogy to various power sources (in particular gasoline) for Dunwall’s industrial revolution, the discovery of the power of voidrite could act as an analogue to nuclear power. Couple that with the very real possibility that Morley could invade other nations with superior, air-based firepower made from the Void-based substance, along with the economic implications inherent to the trans-oceanic Leviathan Causeway, and the stability of the Isles could fall into ruin with the advent of voidrite national superpowers.

Rifts are seen to have erupted all across time, or be capable of being used to access different eras as far back as 1790 and likely earlier still. Without a Void-touched being who has a corporeal presence in the Void and reality (Billie Lurk being the only known example), these eras are not in much danger of having serious alterations in the timeline, but can still pull people from other eras through them. Could this mean that earlier villains could emerge once again, perhaps for some kind of alliance across the ages, brought forth by a magitechnology sorcerer with a mission?

On the magical end, do bonecharms still function? They are not used overtly in the novel, unlike runes, but they do seem to be disconnected from the Outsider’s Mark, especially in the hands of Zhukov (who used the fully powered Twin-bladed knife which might not have the same abilities), Paolo (who used Vera “Granny Rags” Moray’s Marked hand as a vector), and Breanna Ashworth (who had access to her powers through the Arcane Bond with Delilah). How would their functions have shifted, or even been removed altogether, with the changes in the Void? Do they connect with the Leviathans, if we will ever see their like again?

Many questions and possibilities to think on.

In all, Dishonored: The Veiled Terror serves as a great way to conclude at least this saga of the Dishonored franchise, tying together at least most, possibly all, of the remaining loose threads and making a knot through which further stories down the line might continue.

#dishonored#dishonored: the veiled terror#dishonored the veiled terror#dishonored 2#dishonored: the return of daud#Dishonored: The Corroded Man#Dishonored: Death of the Outsider#death of the outsider#the return of daud#the corroded man#the veiled terror#adam christopher#Titan Books#Titan Entertainment#Arkane Studios#Bethesda Softworks#billie lurk#outsider#the outsider#voidrite#magitek#magitech#void#the void

5 notes

·

View notes

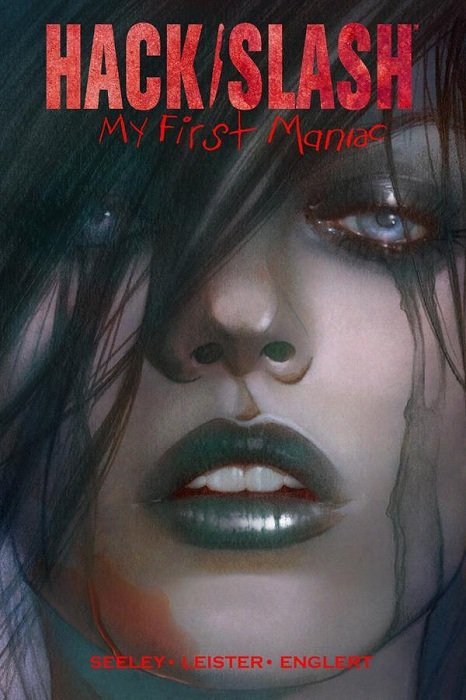

Photo

Artwork by Tim Seeley, Daniel Leister, Mark Englert, and Chris Crank through Image Comics from “Hack/Slash: My First Maniac” #1.

(Mild censorship applied to Mortimer Strick’s buttons.)

For October 30 and Halloween of 2018, I did a thorough analysis of “Hack/Slash,” the horror comic epic (in the classical sense of the term) primarily by Tim Seeley. The analysis (viewable here as Part One and Part Two) was deliberately incomplete, as not only did it only intensely cover the first half of the original 2004-2013 run, but doing so involved providing intentionally inaccurate information as to the way in which the world of “Hack/Slash” functions so as to entice incoming readers without giving too many spoilers.

Here, I will be examining one way in which the world of “Hack/Slash” actually seems to function, by way of looking at the creatures that inhabit it so far as can be thoroughly explained.

There are many different kinds of beings in the world of “Hack/Slash,” all of which initially were collapsed under the overall collective name of “slashers.” While the Psychofiles in the earlier volumes (Volumes 1-5, collected in Omnibuses 1 and 2) did label them all as “slashers,” there were enough outliers, especially those who are given their own, unrelated categorization like “Faustian,” that the term itself seemed too generalized. In fact, many of the most famous villains of the slasher genre do not technically qualify under the actual, more precise definition proposed roughly halfway into the epic’s initial run.

As a note, “Hack/Slash” is a mature comic series. As such, there is the possibility of the occasional swear, as well as graphic imagery.

Furthermore, there will be no censorship for spoilers on this article either, so it assumes the reader is comfortable with the epic as a whole.

Some of the information gleaned here is from inference based on the information presented across the epic, while other pieces are from direct questions asked to Tim Seeley himself either online or through in-person conversation at New York Comic-Con 2018.

Slashers

For convenience, it seems best to list at least part of the first half of the analysis I did on Halloween for this.

What are slashers? Well, imagine your basic slasher movie villain. Revenge driven, extremely durable and at times supernatural. Commonly able to survive and escape if you don’t keep them in your sights. In many cases having additional supernatural abilities, most commonly superhuman strength and at least some level of physical regeneration to come back from death again and again. These villains focus on hurting those who are often guilty of some vice, mostly in terms of sexual activity.

Some of these villains, including many in “Hack/Slash” itself, focus on a specific day or a specific set of circumstances, in particular a holiday or otherwise a single day a year, before returning to their graves. These types of slashers are definitely the most predictable, and so are only very rarely dealt with, but do come up, in particular ones for Groundhog Day, Memorial Day, and Christmas each having some time devoted to fighting them in the story, and some others being mentioned as having been fought off-panel.

[…]

As defined, the slashers in “Hack/Slash” are also known as revenants, an older variation on the zombie archetype from European folklore as early as the Middle Ages, if not earlier. These undead are reanimated corpses that are believed to have revived to haunt the living. In the case of the slashers, as far as Cassie Hack knows from the beginning, they are reanimated by their sheer unstoppable hatred and insanity, their need for revenge, and are drawn to the things that they miss from life, mostly the aforementioned sexual vices. Furthermore, they often (but not always) retain intelligence on some level, enough to remember their past lives in spite of their new (or perhaps not-so-new) murderous obsessions, with their homicidal tendencies geared toward those memories, or even just basic impressions on the moments prior to or directly involved with their deaths in particular.

Additionally, several slashers tend to develop a skill set associated with the method of their death, making for a range of different types of villains. These powers range from someone who can kill others in their dreams, to secreting acids when sexually aroused, to the ability to detach one’s own limbs and move them independently, to transmission through the Internet like an electronic ghost. Each of these powers connects primarily to the manner of death, but also sometimes connect to the users’ personalities, in particular with respect to the acid user and the Internet transmission. The powers eventually tend to evolve over time and with subsequent appearances, developing new means of utilizing skill sets like the acidic secretions or a merger of dream-based powers with general psychic illusions, but on the whole, the power sets stay within set parameters in terms of what kinds of things they can accomplish.

While they do have a variety of powers, there are also some weaknesses that often do not come up in slasher movies. For instance, the most common slashers can be taken down with gunfire if in sufficient amounts, and can also suffer greatly from other forms of damage including blunt trauma or being cut up. In essence, while some slashers may have incredibly high healing abilities, they still can only take so much damage. One especially powerful weakness is fire. Whether or not it is truly the case, fire and explosions seem to do more damage than most other things. Those killed by fire have a tendency to have far more difficulties coming back from the dead again. The weakness is potent enough that Cassie tells others that “fire is your friend” when it comes to slashers. How exactly it works is unclear, but there are a high quantity of stories (which Cassie researched in the process of learning more about slashers) that include fire being used to keep things dead, especially zombies or vampires, so perhaps the same rules of “purifying the unholy” follows, as far as she can initially understand.

Now, all of that is all well and good. But why does fire work so well? Why do only some vengeful beings come back as slashers, while others do not? Not every serial killer Cassie Hack and Vlad face returns as undead, after all, and some of the slashers, like Blackfin the shark, are not even human in the first place.

The answer lies in where they come from, and by whom they were initially created. In fact, the elements stated before are an oversimplification at best.

The two elements at play are best said together at first, then explained separately. Rather than try to tell in general terms, it seems best to go to a certain quote from “Hack/Slash: The Series” #24.

“During his travels, Akakios discovered a small African tribe whom regularly used a plant with many unusual properties. When burned, it created a black flame. When its nectar was injected into a corpse, the body would regain a semblance of life. The plant was used respectfully, and in moderation. Inevitably, the plant’s effects on the brain wore off, leaving only a starving, unliving beast that fed upon living flesh. Akakios destroyed the tribe, taking the secret of the plant, which he called black ambrosia, with him back to Greece. […] Akakios synthesized a chemical from the flower, which he and his followers ingested. Akakios’ alchemy would allow the most devote among the believers to return to life after death, as true paladins of their beliefs. They would live again, stronger than ever before, some with bizarre powers and abilities like the Roman gods of myth, to destroy the Children of Dionysus and save the world. […] [Modern] paladins are those who have the nectar of the black ambrosia running through their veins even after many generations. Those you call slashers.”

First, let’s talk about black ambrosia, and its applications. The flower itself is rarely ever seen, but its nectar is rather prominent. The use of fire seems to burn away the black ambrosia nectar in the slashers’ blood, thereby making reanimation far more difficult (if most of it is removed) or outright impossible without other magical means (if all of it is removed). In the case of fire from lighting up black ambrosia flowers’ oil, the effect is even more potent, first negating the supernatural powers of a slasher, then killing them without the ability for the alchemy to bring them back. Furthermore, every subsequent death seems to result in both heightened powers (if they have specialized abilities) and lessened morals (to the point of attacking those formerly out of their own personal morality either without much care or with deliberate malice, such as in the cases of Bobby Brunswick and Acid Angel). In all, it seems as though a part of the slasher is left behind with each return, replaced with the power that flows through them.

The fluid is not limited to humans, as it has been shown to reanimate and make hostile at least one shark (Blackin) and one car (which will go unnamed intentionally, but appears in “Hack/Slash: Trailers 2”), indicating that ingesting the fluid can also cause one to turn given enough time.

Black ambrosia sees use in two distinct forms: through the bloodline of those who previously been given it, or through direct experimentation to create similar effects artificially.

The ones born into a bloodline with the black ambrosia can be considered “pureblood” slashers. They are the most common of slasher types, seeing as they can crop up at random and are bound to the anti-“sin” mentality originally thought up by Akakios himself, be it intentionally going after such people or unintentionally targeting them. The substance has to be activated, most commonly by the subject’s death, but it can, in theory, be neutralized by certain modern science to at least be rid of the homicidal insanity (or at least the exacerbation of it by the black ambrosia itself), but leave them biologically at the apparent age of their initial death until they are killed by external means. In this case, some of the more famous examples include Jason Voorhees of the Friday the 13th franchise (with his resurrection as a zombie) and, possibly, Michael Myers/The Shape of the Halloween franchise (with his ambiguously supernatural abilities even in continuities that lack the Curse of Thorn). The members of this group that are “Hack/Slash” villains are extremely high, including, but by no means limited to, Doctor Edmund Gross, Angela Cicero/Acid Angel, Ashley Guthrie, both Fathers Wrath, Ian Mattheson/D1aboliq, Matthew Ravenswood/Grinface, Delilah Hack/Lunch Lady, and many, many more.

On the other hand, certain organizations have taken to creating slashers artificially, either intentionally or not, by utilizing black ambrosia-related substances.

On the unintentional side, we have “hate juice” distilled from captive slashers by the pharmaceutical company Ceutotech, Inc., which engaged in “experimental cosmetics” as one of its bases. The goal was to replicate slashers’ ability to heal in order to make better anti-aging creams and presumably other applications to that effect. Of course, the fact that the name was “hate juice,” along with Emily Cristy’s to use it herself, indicates that Ceutotech was aware of its dangerous nature. After ingesting the fluid orally (by drinking it), she began to take on some elements of a slasher, primarily in the form of some limited healing. Cristy, unfortunately, also took on some of the negative side effects as a result, including the “back of your head ‘panic attack’” voice (to quote Cassie from ‘My First Maniac’) and highly violent actions, but managed to keep herself more or less under control aside from some slips until her first death in the explosion of her building. Despite probably not being a hereditary slasher herself, she reanimated, and was far more lucid than many others, even to the point of paying back Cassie and Vlad’s kindness by saving their life once. Her ability to reanimate appeared to be far less potent than most, as being impaled killed her once again, and subsequent reanimations were quickly dealt with.

On the more intentional side, we have the work of Doctor Ezekiel Chase at the Englund Prison in Indigo River (examined in ‘Resurrection’ during its first arc). He seemed to be completely aware of the nature of slashers, to the point of having sought out Vlad to help her, and various “resurrection fluid” formulas (which are directly identified as connected to black ambrosia by Cassie and Vlad both) are able to reanimate subjects in varying levels of cognition, ranging from Vlad having all of his faculties back to Dominique Peacetree being little more than a zombie, as was the case with the “controlled fun-dead” of the prison and the fatally poisoned counselors. While this type does engage in some ritualized behavior in the case of the less aware, as Cassie herself says, “their brains are mostly soup at this point.”

Outside of black ambrosia itself, we have its originator, the mystical alchemist Akakios. Without indulging too heavily in who he actually is, his power over existing slashers, especially those of the pureblood variety, cannot be denied. To explain, it seems best to indulge not only in the events of his life (and apparent unlife) but also what came after his final death. During ‘Final,’ he seemed to have an unparalleled control over slashers as a whole, able to control even the most volatile of his “paladins” such as the first Father Wrath and Grinface with little more than a look and a speech, could control entire hordes of slashers in the averted apocalyptic timeline, and could even “feel their deaths, new and final” when Nef magic annihilated his army at the end of ‘Final.’

As Cassie says in “Hack/Slash vs. Chaos!” #1, “Vlad and I put an end to the slasher bloodline. They don’t come back anymore.” In arcs ranging from ‘Crossroads’ to ‘Final’ (especially those two), the black flame seemed able to resurrect many slashers without any direct input, something that ceased entirely after Akakios was finally executed with extreme prejudice, indicating that the slasher repeated reanimations relied upon his continued life as a mystical tether. This idea is further proven by the fact that Dick Weiner of the final issue of “Hack/Slash: Resurrection” was reanimated in the 1980s, but unlived long into the 2010s until his death by woodchipper being his last demise, as well as the reanimation fluid of Dr. Chase only allowing for one extra life.

Putting together these clues, Akakios seems to, as the “father” of the slashers as a whole, link the slashers’ reanimations to himself through his mystical alchemy to enhance his control over them and render himself indispensible (not to mention heighten his apparent messiah complex as the “murder messiah”). The problem with this is that Akakios renders the entire group vulnerable once he is killed off, but what can you do?

Witches

Some characters can use magic, but only a rare few are so integrated with magic that they can easily learn it. Only directly identified as “witches” in ‘Murder Messiah,’ this kind of magic user is distinct from other ones due to the fact that she (the examples given are both female) is intrinsically tied to magic through her bloodline, rather than being just any random person who can use a spell book.

In the world of “Hack/Slash,” the two primary examples are Laura Lochs and her black sheep sister, Liberty “Libby” Lochs. Magic comes exceptionally easily to these, and likely other, witches, regardless of its form. However, the type of magic used differs depending on the witch’s preferences (in terms of the style of how they use it) and what they come across (in terms of the magical systems themselves) more than anything else. Both of the Lochs sisters were able to learn myriad types of magic about as easily as basic study of a book, rather than needing any real training in many cases.

For Laura, it came in the form of the spell book with which she originally learned magic in her first story, ‘Girls Gone Dead,’ which seemed to consist of verbal magic and blood rituals, but very little, if anything, in the way of direct offensive use of her power. On finding Papa Sugar, she learned the use of certain voodoo magics (in the style of Child’s Play, on account of it being during the ‘Vs. Chucky’ story) such as the creation of certain potions and use of specific incantations, with little apparent effort needed to learn any of the intricate elements. She also appears to have known necromancy, which she taught to her sister Libby. Her own style focused on controlling others and the environment through murder, including creation of voodoo zombies, controlling a slasher’s actions through verbal commands said backwards, and leading her sister to control Julian Gallo the Mosaic Man by linking him intrinsically to the powers of death.

Libby, on the other hand, stuck to a different style. Aside from controlling the Mosaic Man in the name of revenge against Cassie’s hand in Laura’s death, she used necromancy’s control of souls to attempt to help people by manipulation of luck. After abandoning necromancy itself, she took to a more “modern” sorcery, to the point of openly calling herself a witch, focusing in on the use of verbal commands to control those who can hear them, to the general effect of far more offensive use of magic in the name of helping others instead of her sister’s malevolent, more low-key use of spells in general. She also seems to have a very good grasp on Neffish black magick (to be discussed lower down), such that she is capable of using the Neffish guitar for time travel relatively easily (physical illness notwithstanding).

According to Libby, every witch gets a “broom” (hers being a motorcycle) and a “familiar” (hers being flesh-eating bacteria), leaving the possibility that the reason why Laura did not develop either of these things is that she never took the time to do so or did not live long enough to accomplish it, unlike Libby’s several months on her own learning new magic.

Just because witches can have easy access to magic does not mean that they are completely aware of all of the intricacies of the magic that they use, as can be seen from attempts to use necromancy for benevolent purposes without understanding its basic manipulation of souls.

“She ruins everything she touches. She wanted to do ‘good’ with a necromancy book. She tried to make lucky items for the dregs, the luckless losers like her. But necromancy isn't meant to bless items. To do so drags a spirit out of the afterlife and binds it to the object. A slave spirit that doesn't want to be there.”

On account of their mystical nature, some of these beings (in particular Laura) can subvert their own death by latching on to another witch’s consciousness to teach how to use some magic, becoming a kind of ghost in the process, albeit one with very limited connection to the physical world.

Mystic Empowerment

Certain entities were empowered by magical sources, whether through spells they cast or those cast upon them or others connected to them. As these entities are not intrinsically magical in the same way as witches, they seem appropriate to discuss separately.

Insofar as famous examples in fiction go, we have Charles Lee Ray and his transformation into Chucky through voodoo magic of the Heart of Damballa in the Child’s Play franchise (though he might, possibly, be a witch), and the cursed, corporeal ghost of Victor Crowley in the Hatchet films, both of which coincidentally appear in the “Hack/Slash” series themselves.

While slashers can be additionally mystically empowered, such as the case with the Mosaic Man in ‘Sons of Man’ and ‘Foes and Fortunes,’ that power is distinct from that of external spells, and so cannot truly be considered the same type of foe. However, empowering certain beings with additional magic may leave them as servants of said forces instead of their own will, as is the case with the aforementioned slasher.

“When we raised Julian, we bonded him to the powers of death and black magic so that he would be at our beck and call. Julian serves death. He'll free any spirits imprisoned on this plane.”

In general, mystic empowerment is a subset to the doings of witches more than it is a distinct power on its own.

Nef

The creatures of Nef (adjective form “Neffish”) are, by and large, some kind of amalgamation between aliens and demons. They are called demons, and treated as such, but in fact are not in any form of Hell that can be accessed by humans after death. Instead, Nef seems to be some kind of alternate dimension.

The only real method of reproduction for the beings of Nef is impregnating virgin females from the main dimension, regardless of species. The resultant Nef being emerges from the host’s body through their torso akin to an Alien franchise chestburster, killing the mother very violently. Understandably, finding a willing mother is pretty much impossible, hence the use of avatars (see Avatars below).

What type of Nef being emerges depends upon the individual being impregnated. In the case of a dog, the emergent Nef demon will be a “lowbeast,” a kind of hellhound type creature that is what appears to be the lowest form of Nef life, and of which the character Pooch is a member. Others exist, such as the apparent greatest warrior Kuma, a tusked humanoid misidentified as “Bigfoot,” but barring one appearance of hers and some others like minor villain Kumok, there isn’t a lot of emphasis on them as a whole.

One thing that is known is that, again much like the Xenomorphs of the Alien franchise, Nef creatures appear to have some form of DNA reflex, an ability to take on certain aspects of the host creature while still being definitely of Nef. This difference accounts for not only the bizarre look of lowbeasts being vaguely similar to a dog or a horse, but also certain abilities of more advanced Nef beings. Mid-level Nef creatures like Kumok have the ability to utilize weapons such as Nef wands to control “black magick,” but instead of being sorcerers on their own, these wands seem accessible to and easily usable by anyone, including Cassie Hack or Vlad, meaning that there isn’t an intrinsic ability more than there is general sapience.

The most prominent example of this reflex giving powers has to be the Stillborn, a creature that was born from the body of the psychic Martha "Muffy" Jaworski possessed by the dream-based killer Ashley Guthrie, the latter of whom had a psychic connection to Cassie Hack that had only been exacerbated by increased powers through the former. As a result, he had an exceptionally strong psychic connection to Cassie, able to have her see through his eyes during his serial killings even aside from his fame-based cannibalistic empowerment, paralysis-inducing “starstruck” abilities, and eventual electrical manipulation, both of which fit in with the “worship through a rock star” attitude of Nef itself.

Avatar

In some cases, individuals play host to an otherworldly, superhuman power. The means of acquiring these powers differ, but the overall effect is that of a need to keep the connection to that power to retain magical (or presumably other) abilities.

On the one hand, we have the classic Faustian bargain, offering something up in exchange for power from demonic entities, ones that entirely relinquish their hold on said abilities until they decide to take them back through one manner or another. Our most prominent example of this kind of power would have to be Jeffrey Brevvard, a.k.a. Six Sixx of the short-lived band Acid Washed. Given access to the Neflords (see Nef above) by their latest recruiter and former avatar (heavily implied but never outright stated to be a certain music King who is presumed to have died in August of 1977), he sacrifices young women to the Neflords in exchange for various powers that his Psychofiles profile identifies as “black magick,” a skill set that includes raising his soulless bandmates from their crates, transforming into a demonic entity with wings, the ability to be seen as very famous and popular in spite of his lackluster music through probability alteration, and access to his black magick Neffish guitar. The latter is not as much a part of his type of creature as it is a consequence of said power, which can be used by others if they can get their hands on it to do things including opening a portal to different dimensions such as Nef and the Dream World or between different areas on Earth, time travel, projection of blasts of energy, hypnosis of virgins, and potentially much more. In all, the power relies upon a steady flow of virgin sacrifices, to which point Six Sixx develops a body count of at least fourteen before the end of his run.

Another example of this kind of power is famous from slasher films, and even comes up under a different name in the ‘Mind Killer’ arc after a brief appearance at the ends of ‘Shout at the Devil’: the Dream Demons that empowered Freddy Krueger of the A Nightmare on Elm Street franchise. Although the Dream Demons are only identified as “Dread Drinkers” by Six Sixx on account of him not knowing their names, their appearance and fear-inducing abilities make their true identities readily apparent to those with the right knowledge, placing Krueger (who had been previously identified by Chucky and also was mentioned without directly stating his name in ‘My First Maniac’) in the role of an avatar to their power, rather than a slasher in and of himself. The fact that he could be depowered through skillful use of time travel in Freddy vs. Jason vs. Ash: The Nightmare Warriors adds further credence to him not being a slasher.

The other major type of power is that of a divine influence, as is the case with Fantomah, Mystery Woman of the Jungle, a character in public domain who was involved in events during the ‘Super Sidekick Sleepover Slaughter’ arc and her own one-shot arc ‘Mystery Woman.’ In her case, the powers granted are fantastical to the point of her being seen as a goddess, able to perform ridiculously powerful, often quite over-the-top punishments on those she deems to be worthy of said behavior, including villains associated with her capture and those who would attack her jungle. However, while the powers themselves are quite memorable, their source is less reliable. Fantomah’s power relies upon the continued existence of her jungle, and with her capture for decades in the “Godbox,” she was unable to prevent the quite realistic destruction of said jungle by modern society’s deforestation. As such, while her powers are quite strong shortly after emerging from her captivity, they quickly weaken to nothing more than illusions, and eventually are removed from her altogether in favor of a more suitable host, leaving her to mortality once more.

Monsters

Perhaps the best term to use for the creatures outright called “monsters” in ‘Son of Samhain’ would be “orcs,” in the classic J.R.R. Tolkein scheme. Judging from how the overall tone of ‘Son of Samhain’ is more of a pulpy action story than a horror story, determining their characteristics is a bit more difficult, in no small part due to them only being brought up for a single arc.