"Hate, it has caused a lot of problems in this world, but it has not solved one yet." “Odio, ha causado tantos problemas en este mundo, pero no ha resuelto ni uno.”

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

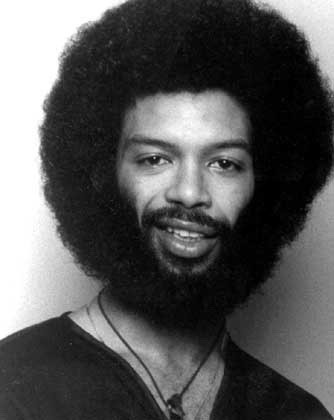

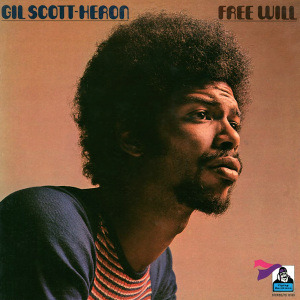

Gil Scott-Heron was a New York City-based writer, spoken word performer, poet, and musician whose 1970s songs are known for laying the groundwork for rap music.

If you have heard the phrase "The revolution will not be televised," you have heard the words of Gil Scott-Heron. While both true and timeless, it's the title of Scott-Heron's poem that depicted the disconnected relationship between television/media representation and demonstrations in the street.

He has been called the "godfather of rap," and his music and words have been sampled by rappers like Common and Kendrick Lamar.

Even if you haven't heard of him, his work may sound more familiar than you think. One of his most famous pieces is "Whitey on the Moon" where he criticizes America's interest in space taking precedence over the well-being of African American citizens.

•••

Gil Scott-Heron fue un escritor, intérprete de la palabra hablada, poeta y músico originario de Nueva York cuyas canciones de los años 70 son conocidas por sentar las bases del rap.

Si has escuchado la frase: «La revolución no será televisada», entonces has escuchado las palabras de Gil Scott-Heron. Aunque cierto y atemporal, es el título del poema de Scott-Heron que describía la desconectada relación entre la representación televisiva/mediática y las manifestaciones en la calle.

Se le ha llamado el «padrino del rap», y su música y sus palabras han sido sampleadas por raperos como Common y Kendrick Lamar.

Aunque no hayas escuchado hablar sobre él, puede que su obra te suene más de lo que cree. Una de sus piezas más famosas es «Whitey on the Moon», donde critica el interés de Estados Unidos por conquistar el espacio encima de el bienestar de los ciudadanos afroamericanos.

#rap music#rapper#history#blackhistory#black history is everybody's history#historyfacts#black history is world history#blackhistorymonth#blackpeoplematter#blacklivesalwaysmatter#knowyourhistory#black history is american history#black history matters#know your history#black history month#black history#black music matters#black musicians#black music#musician#musicians#music#kendrick lamar#common#blacklivesmatter#culture#blackhistoryyear#blackownedandoperated#revolution#new york

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anarcha, Lucy, Betsey: The Mothers of Gynecology

Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey were enslaved women from plantations in and around Montgomery, Alabama. With neither consent nor anesthesia, they were experimented upon by Dr. J. Marion Sims in the 1840s. After publishing the results of his “success,” Sims moved to New York to seek fame and fortune.

Within a decade, he became known as the Father of Gynecology.

By contrast, Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey fell into history. They changed the world, only to beforgotten by it.

All three women developed a painful medical condition after childbirth that caused them to lose control of their bladders and bowels. Enslaved women with this condition were kept apart from other workers. There was no cure. Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy were told they would have to live with the pain and shame of their injuries for the rest of their lives.

The men who enslaved Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy were frustrated with their condition. They wanted to find a cure, not because they cared deeply about the enslaved women, but because the women could no longer do the hard labor that would earn money for their enslavers. In 1844, all three enslavers sought the advice of doctor J. Marion Sims.

Like many doctors in the 1800s, J. Marion Sims was very interested in medical advancement and experimentation. He practiced all kinds of medicine, from dentistry to pediatrics to general surgery. In 1835, he moved from South Carolina to Alabama after two of his patients died. Eventually, he settled in Montgomery County, where he came to the attention of the men who enslaved Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy.

Sims had recently discovered a new way to position surgical patients. He believed he might be able to cure Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy within six months. He made arrangements with their enslavers to lease the women for the duration of their treatment, so he had complete control over their bodies. It is unlikely that Anarcha, Betsey, or Lucy ever had the opportunity to consent to the experimentation they were about to endure.

Lucy was the first of the three women to undergo Sims’s experimental operation. The operating room was packed with doctors who wanted to watch the procedure. She was not asked whether she was comfortable with strange men watching her operation. Lucy was brought to the operating room naked and restrained on the table so her involuntary movements during surgery would not disrupt the procedure. Sims did not use anesthesia to numb her pain. This was partly because doctors feared patients could die from anesthesia and partly because it was commonly believed that black women did not experience pain the same way white women did. Lucy’s surgery took about an hour, and she was conscious for every minute of it.

After the surgery, Lucy developed a terrible infection from a device Sims had placed in her bladder. She experienced days of extreme agony. Sims was able to cure her infection, but her injury did not heal. The operation was a failure.

Betsey was the next person to undergo Sims’s operation. Like Lucy, Betsy was naked on the operating table and not given any anesthesia. This time, Sims used a device he invented for her bladder, and Betsey did not experience the same post-surgical infection that Lucy suffered. But Betsey’s injury was not repaired and this operation was also considered a failure. Anarcha was operated on last, with the same results.

When the results of Anarcha’s surgery became widely known, the local medical community decided that Sims was a failure and stopped supporting his experiments. Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy were left in Sims’s control, because without a cure, they were considered useless to their enslavers. They worked for the Sims family in the periods between their procedures and recovery.

Sims decided to carry on with his experiments even though all of his white male assistants quit. He trained Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy to be his assistants during operations and taught them how to care for each other during their recoveries. Separated from their families and communities, with medical conditions that made them social outcasts, the women had no choice but to continue cooperating with Sims. In time, they became skilled medical practitioners in their own right.

Sims experimented on Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy for the next five years. He also brought in other enslaved women to experiment on. He had no shortage of patients because enslaved women did not receive proper care during pregnancy. Sims bought one patient because her case was unique, and her enslaver was not willing to risk his investment on an experimental surgery. Sims practiced his procedure on a total of 12 women, but only Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy were named in his published reports.

In the summer of 1849, Sims performed Anarcha’s 30th operation. He used all of the new tools and techniques he had developed over the last four years. This time, Anarcha’s injury finally healed and she made a full recovery. Shortly after perfecting his technique, Sims closed his hospital and moved north. Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy all returned to their enslavers after five years of absence and experimentation.

In 1852, Sims published an article that outlined his new procedure. To appeal to a wider audience, he never mentioned that the women he operated on were enslaved or that he had total control over their bodies. He also never mentioned that the enslaved women became skilled medical practitioners. In the illustrations that accompanied his article, he is shown operating on white women with the help of a white nurse. The patient is also covered, a token of respect that Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy never received.

Sims’s work and article revolutionized surgical treatments for women and earned him the nickname “the father of modern gynecology.” But it must be acknowledged that these advancements were made through the exploitation of enslaved women’s bodies. Some historians have argued that Sims’s patients became enthusiastic participants in his experiments, but it is important to remember that they had no choice. Anarcha, Betsey, Lucy, and all of the unnamed patients of J. Marion Sims deserve to be remembered as the mothers of modern gynecology, because without their labor and pain, Sims’s critical achievement would not have been possible.

•••

Anarcha, Lucy, Betsey: Las Madres de la Ginecología

Anarcha, Lucy y Betsey eran mujeres esclavizadas procedentes de plantaciones de Montgomery (Alabama) y sus alrededores. Sin consentimiento ni anestesia, el Dr. J. Marion Sims experimentó con ellas en la década de 1840. Tras publicar los resultados de su «éxito», Sims se trasladó a Nueva York en busca de fama y fortuna.

En una década, se le conoció como el Padre de la Ginecología.

En cambio, Anarcha, Lucy y Betsey pasaron a la historia. Cambiaron el mundo, sólo para ser olvidadas por él.

Las tres mujeres desarrollaron una dolorosa enfermedad después de dar a luz. Les hizo perder el control de la vejiga y los intestinos. A las mujeres esclavizadas con esta enfermedad se las mantenía separadas de los demás trabajadores. No había cura. A Anarcha, Betsey y Lucy les dijeron que tendrían que vivir con el dolor y la vergüenza de sus lesiones el resto de sus vidas.

Los hombres que esclavizaron a Anarcha, Betsey y Lucy se sentían frustrados por su situación. Querían encontrar una cura, no porque se preocuparan profundamente por las mujeres esclavizadas, sino porque las mujeres ya no podían hacer el trabajo duro que ganaría dinero para sus esclavizadores. En 1844, los tres esclavistas buscaron el consejo del doctor J. Marion Sims.

Como muchos médicos del siglo XIX, J. Marion Sims estaba muy interesado en los avances y experimentos médicos. Practicó todo tipo de medicina, desde odontología hasta pediatría y cirugía general. En 1835, se trasladó de Carolina del Sur a Alabama tras la muerte de dos de sus pacientes. Finalmente, se estableció en el condado de Montgomery, donde llamó la atención de los hombres que esclavizaron a Anarcha, Betsey y Lucy.

Sims había descubierto recientemente una nueva forma de colocar a los pacientes quirúrgicos. Creía que podría curar a Anarcha, Betsey y Lucy en seis meses. Llegó a un acuerdo con sus esclavizadores para arrendar a las mujeres mientras durara su tratamiento, de modo que tenía un control total sobre sus cuerpos. Es poco probable que Anarcha, Betsey o Lucy tuvieran la oportunidad de dar su consentimiento a los experimentos que estaban a punto de sufrir.

Lucy fue la primera de las tres mujeres en someterse a la operación experimental de Sims. El quirófano estaba abarrotado de médicos que querían ver la intervención. No le preguntaron si se sentía cómoda con hombres extraños observando su operación. A Lucy la llevaron desnuda al quirófano y la sujetaron en la mesa para que sus movimientos involuntarios durante la operación no interrumpieran el procedimiento. Sims no utilizó anestesia para calmar el dolor. Esto se debía en parte a que los médicos temían que los pacientes murieran a causa de la anestesia y en parte a que se creía que las mujeres negras no experimentaban el dolor del mismo modo que las mujeres blancas. La operación de Lucy duró aproximadamente una hora, y estuvo consciente durante cada minuto.

Tras la operación, Lucy desarrolló una terrible infección a causa de un dispositivo que Sims le había colocado en la vejiga. Pasó días de extrema agonía. Sims consiguió curar la infección, pero la herida no sanó. La operación fue un fracaso.

Betsey fue la siguiente en someterse a la operación de Sims. Al igual que Lucy, Betsey estaba desnuda en la mesa de operaciones y no recibió anestesia. En esta ocasión, Sims utilizó un dispositivo inventado por él para su vejiga y Betsey no sufrió la misma infección postoperatoria que Lucy. Pero la lesión de Betsey no se reparó y esta operación también se consideró un fracaso. Anarcha fue operada por último, con los mismos resultados.

Cuando se dieron a conocer los resultados de la operación de Anarcha, la comunidad médica local decidió que Sims era un fracaso y dejaron de apoyar sus experimentos. Anarcha, Betsey y Lucy quedaron bajo el control de Sims, ya que sin una cura se consideraban inútiles para sus esclavizadores. Trabajaron para la familia Sims en los periodos entre sus intervenciones y recuperaciones.

Sims decidió continuar con sus experimentos a pesar de que todos sus ayudantes varones blancos renunciaron. Entrenó a Anarcha, Betsey y Lucy para que fueran sus ayudantes durante las operaciones y les enseñó a cuidarse mutuamente durante sus recuperaciones. Separadas de sus familias y comunidades, con problemas médicos que las convertían en marginadas sociales, las mujeres no tuvieron más remedio que seguir cooperando con Sims. Con el tiempo, se convirtieron en expertas médicas por derecho propio.

Sims experimentó con Anarcha, Betsey y Lucy durante los siguientes cinco años. También trajo a otras mujeres esclavizadas para experimentar con ellas. No le faltaban pacientes porque las mujeres esclavizadas nunca recibían los cuidados adecuados durante el embarazo. Sims compró a una paciente porque su caso era único y su esclavizador no estaba dispuesto a arriesgar su inversión en una cirugía experimental. Sims practicó sus procedimientos en un total de 12 mujeres, pero sólo Anarcha, Betsey y Lucy fueron nombradas en sus informes publicados.

En el verano de 1849, Sims realizó la trigésima operación de Anarcha. Utilizó todas las nuevas herramientas y técnicas que había desarrollado en los últimos cuatro años. Esta vez, la lesión de Anarcha sanó por fin y se recuperó por completo. Poco después de perfeccionar su técnica, Sims cerró su hospital y se trasladó al norte. Anarcha, Betsey y Lucy regresaron a sus esclavizadores tras cinco años de ausencia y experimentación.

En 1852, Sims publicó un artículo en el que describía su nuevo procedimiento. Para atraer a un público más amplio, nunca mencionó que las mujeres a las que operaba eran esclavas ni que tenía un control total sobre sus cuerpos. Tampoco mencionó que las mujeres esclavizadas se convertieron en expertas médicas. En las ilustraciones que acompañan a su artículo, aparece operando a mujeres blancas con la ayuda de una enfermera blanca. La paciente también está cubierta, una muestra de respeto que Anarcha, Betsy y Lucy nunca recibieron.

El trabajo y el artículo de Sims revolucionaron los tratamientos quirúrgicos para las mujeres y eso le ganó el apodo de «padre de la ginecología moderna». Pero hay que reconocer que estos avances se lograron mediante la explotación de los cuerpos de mujeres esclavizadas. Algunos historiadores han argumentado que las pacientes de Sims se convirtieron en entusiastas participantes en sus experimentos, pero es importante recordar que no tenían elección. Anarcha, Betsey, Lucy y todas las pacientes anónimas de J. Marion Sims merecen ser recordadas como las madres de la ginecología moderna, porque sin su trabajo y su dolor, el logro crítico de Sims no habría sido posible.

#blacklivesmatter#blackhistory#history#blacklivesalwaysmatter#blackhistorymonth#blackpeoplematter#knowyourhistory#blackwomenmatter#protect black women#gynecology#medical apartheid#medical segregation#medicine#medicina#ginecología#lasvidasnegrasimportan#know your history#black history is everybody's history#historyfacts#facts#black history is world history#black history is american history#medicaladvancements#black queens#black history month#black history#historia#culture#blackhistoryyear#power to the people

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

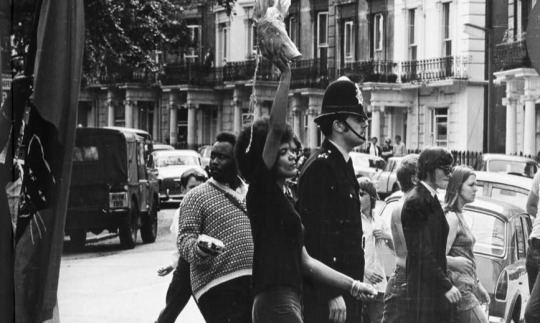

The Mangrove Nine Trial was Britain’s most influential Black Power trial. In Britain, descendants from the Caribbean, Africa, or South Asia, who were mainly immigrants from former British colonies, were considered to be “black.” The London police and the British Home Office, responsible for immigration, security, and law and order, orchestrated the arrest and trial of nine black leaders in 1970 to discredit London’s growing Black Power movement.

The Mangrove trial focused on the police harassment of the Mangrove restaurant in west London’s Notting Hill area, which was owned by Frank Crichlow, a Trinidad-born community activist. The restaurant was the heart of the Caribbean community and was also popular with white and black celebrities. Because Crichlow was a Black Power activist, police raided his restaurant twelve times between January 1969 and July 1970, calling the Mangrove a den of drugs, despite not finding any evidence.

In response to this intense police harassment, Crichlow filed a complaint to the Race Relations Board, accusing the police of racial discrimination. His employee, Darcus Howe, a Trinidad-born Black Power activist, encouraged Critchlow to work with the British Black Panthers (BBP) in London to organize a demonstration against police harassment of the Mangrove.

On August 9, 1970, 150 protesters marched to local police stations and were met by 200 police who initiated the violence that ensued. Nine protest leaders were arrested and charged with incitement to riot: Crichlow; Howe, who later became a BBP member; Althea Jones-Lecointe, head of the BBP; Barbara Beese, BBP member; Rupert Boyce; Rhodan Gordon; Anthony Innis; Rothwell Kentish; and Godfrey Millett.

Initially the court dismissed the charges because the statements of twelve officers were ruled to be inadmissible because they equated black radicalism with criminal intent. However, the Director of Public Prosecutions reinstated the charges and the defendants were rearrested.

The nine defendants used a radical legal strategy in the subsequent trial. Howe and Jones-Lecointe defended themselves arguing that this was a political trial. The radical lawyer Ian McDonald represented Beese and coordinated the defense of Howe and Jones-Lecointe with the other defendants’ lawyers.

Howe and McDonald argued for the right to an all-black jury under the Magna Carta’s “jury of peers” clause. McDonald cited case law allowing Welsh miners to have an all-Welsh jury that led to the practice of selecting juries from the defendant’s neighborhood. The conservative judge rejected these arguments. During jury selection, the defense dismissed sixty-three potential jurors, ensuring that there were only two blacks on the twelve-person jury.

During the fifty-five-day trial Jones-Lecointe described police persecution of Notting Hill’s black community. Howe exposed inconsistencies in police testimony, and a police officer had to leave the courtroom when he was seen signaling to prosecution witnesses as they testified. Meanwhile, outside the courtroom, the BBP organized pickets and distributed flyers to win popular support. Ultimately the jury acquitted all nine on the charge of rioting.

When Judge Edward Clarke stated that there was evidence of racial hatred on both sides, this was the first time a British court judge acknowledged racial discrimination and wrongdoing by the London police. The Mangrove Nine gathered broad public support for the fight against police racism in Britain and showed that the fight for racial justice could be won.

•••

El juicio de los Mangrove Nine fue el juicio de Poder Negro más influyente de Gran Bretaña. En Gran Bretaña se consideraban «negros» a los descendientes del Caribe, África o el sur de Asia, la mayor parte eran inmigrantes de las antiguas colonias británicas. La policía de Londres y el Ministerio del Interior Británico, responsables de inmigración, seguridad y orden público, orquestaron la detención y el juicio de nueve líderes negros en 1970 para desacreditar el creciente movimiento de Poder Negro en Londres.

El juicio Mangrove se centró en el acoso policial al restaurante Mangrove, situado en la zona de Notting Hill, al oeste de Londres, cuyo propietario era Frank Crichlow, un activista comunitario nacido en Trinidad. El restaurante era el corazón de la comunidad caribeña y también era popular entre celebridades blancas y negras. Como Crichlow era un activista del Poder Negro, la policía hizo doce redadas en su restaurante entre enero de 1969 y julio de 1970, calificando al Mangrove como un refugio para drogas, a pesar de no encontrar ninguna prueba.

En respuesta a este intenso acoso policial, Crichlow presentó una denuncia ante la Comisión de Relaciones Raciales, acusando a la policía de discriminación racial. Su empleado, Darcus Howe, activista del Poder Negro nacido en Trinidad, animó a Crichlow a colaborar con los Panteras Negras Británicas (BBP) de Londres para organizar una manifestación contra el acoso policial al Mangrove.

El 9 de agosto de 1970, 150 manifestantes marcharon hacia las estaciones policiales locales y fueron recibidos por 200 policías, los cuales iniciaron la violencia. Nueve líderes de la protesta fueron detenidos y acusados de incitación a los disturbios: Crichlow; Howe, quien más tarde se convirtió en miembro del BBP; Althea Jones-Lecointe, jefa del BBP; Barbara Beese, miembro del BBP; Rupert Boyce; Rhodan Gordon; Anthony Innis; Rothwell Kentish; y Godfrey Millett.

Inicialmente, el tribunal desestimó los cargos porque se consideró que las declaraciones de doce agentes eran inadmisibles porque equipaban el radicalismo negro con la intención delictiva. Sin embargo, el Director de la Fiscalía readmitió los cargos y los acusados volvieron a ser detenidos.

Los nueve acusados utilizaron una estrategia jurídica radical en el juicio. Howe y Jones-Lecointe se defendieron argumentando que todo se trataba de un juicio político. El abogado radical Ian McDonald representó a Beese y coordinó la defensa de Howe y Jones-Lecointe junto con los abogados de los demás acusados.

Howe y McDonald defendieron el derecho a un jurado compuesto exclusivamente por negros en virtud de la cláusula «jurado de iguales» de la Carta Magna. McDonald citó la jurisprudencia que permitía a los mineros galeses tener un jurado compuesto exclusivamente por galeses y que dio lugar a la práctica de seleccionar jurados del mismo vecindario del acusado. El juez conservador rechazó estos argumentos. Durante la selección del jurado, la defensa descartó a sesenta y tres posibles jurados, asegurándose de que sólo hubieran dos personas negras en un jurado de doce personas.

Durante los cincuenta y cinco días que duró el juicio, Jones-Lecointe describió la persecución policial de la comunidad negra de Notting Hill. Howe expuso incoherencias en los testimonios policiales, y un agente de policía tuvo que abandonar la sala al ser visto haciendo señas a los testigos de los acusados mientras declaraban. Mientras tanto, fuera del tribunal, el BBP organizó postes y distribuyó volantes para ganarse el apoyo popular. Finalmente, el jurado absolvió a los nueve acusados de disturbios.

Cuando el juez Edward Clarke declaró que existían pruebas de odio racial por ambas partes, esa fue la primera vez que un juez de un tribunal británico reconocía la discriminación racial y las irregularidades cometidas por la policía de Londres. Los Mangrove Nine reunieron un amplio apoyo público para la lucha contra el racismo policial en Gran Bretaña y demostraron que la lucha por la justicia racial podía ganarse.

#blackhistory#history#knowyourhistory#black panthers#black power#blackhistorymonth#blacklivesmatter#blacklivesalwaysmatter#black history month#black history#black history is everybody's history#historyfacts#black history is world history#black history is american history#london#share#freedom fighters#historia#know your history#power to the people#knowledge#knowledgeisfree#knowledgeispower#blackpeoplematter#lasvidasnegrasimportan#español#blackownedandoperated#blackowned#english#britain

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The poison we learned to drink: Internalized racism.

The first time you were told you weren't enough.

It wasn't with words. It was a look, a sneer, an absence.

It was the silence in the classroom when you said your last name.

It was the restrained laughter when your mother spoke in her language.

It was the “well-meant” advice, “If you straighten your hair, you'll do better.”

No one called it racism.

No one needed to.

The message was already planted:

Being you was a mistake you needed to correct.

Internalized racism doesn't scream.

It sits with you at dinner.

It accompanies you in front of the mirror.

Helps you choose clothes “that make you look less brown or black.”

It advises you not to go out in the sun.

It suggests you shut up so you don't look “too intense”.

And you listen to it.

Not because you love it.

But because one day you were convinced that it was your own voice talking.

How do you disarm something that lives in you?

Sometimes, you don't know if what you feel is shame or weariness.

If what you hate about you is your reflection or the reflection of a story you didn't write.

And then you understand:

Racism doesn't just deny you in the world. It denies you in your own body.

It makes you foreign to yourself.

It makes you look with a lack of confidence at your nose, your skin, your accent, your roots.

And it blames you if it hurts.

It blames you for not knowing how to love yourself in a land that taught you to hate yourself.

There is no recipe for unlearning learned hatred.

To heal is to sit with your history and stop apologizing to it.

Healing is crying for all the times you kept quiet to fit in.

It is to look at a picture of yourself as a child and say,

"You were perfect. It's just that no one told you so."

It's to stop looking for approval in eyes that never really saw you.

It's building a home inside of you, where your skin is not a trench but a temple.

Racialized self-love is not a trend. It is a revolution.

To love your hair, your voice, your grandmother, your neighborhood, your language, your shadow - is to break the centuries-old machinery that works to make you disappear.

Internalized racism is forgetting.

Emotional anti-racism is memory.

And you are remembering.

Sometimes slowly. Sometimes with rage. Sometimes with fear.

But you are coming back.

To you.

•••

El veneno que aprendimos a beber: Racismo internalizado.

La primera vez que te dijeron que no eras suficiente:

No fue con palabras. Fue una mirada, una burla, una ausencia.

Fue el silencio en la sala de clases cuando dijiste tu apellido.

Fue la risa contenida cuando tu madre habló en su lengua.

Fue el consejo “bien intencionado”: “Si alisas tu cabello, te irá mejor.”

Nadie lo llamó racismo.

Nadie necesitó hacerlo.

El mensaje ya estaba sembrado:

Ser tú era un error que debías corregir.

El racismo internalizado no grita.

Se sienta contigo a cenar.

Te acompaña frente al espejo.

Te ayuda a elegir ropa “que te haga ver menos morena o negra”.

Te recomienda no salir al sol.

Te sugiere callarte para no parecer “demasiado intensa”.

Y tú le haces caso.

No porque lo ames.

Sino porque un día te convencieron de que era tu propia voz hablando.

¿Cómo se desarma algo que vive en ti?

A veces, no sabes si lo que sientes es vergüenza o cansancio.

Si lo que odias de ti es tu reflejo o el reflejo de una historia que no escribiste.

Y entonces entiendes:

El racismo no solo te niega en el mundo. Te niega en tu propio cuerpo.

Te vuelve extranjero de ti.

Te hace mirar con desconfianza tu nariz, tu piel, tu acento, tus raíces.

Y te culpa si duele.

Te culpa por no saber amarte en una tierra que te enseñó a odiarte.

No existe una receta para desaprender el odio aprendido.

Sanar es sentarte con tu historia y dejar de pedirle perdón.

Sanar es llorar por todas las veces que te callaste para encajar.

Es mirar una foto tuya de niño y decirle:

“Eras perfecto. Solo que nadie te lo dijo.”

Es dejar de buscar aprobación en ojos que nunca te vieron de verdad.

Es construir un hogar dentro de ti, donde tu piel no sea trinchera sino templo.

El amor propio racializado no es una moda. Es una revolución.

Amar tu cabello, tu voz, tu abuela, tu barrio, tu idioma, tu sombra — es romper la maquinaria de siglos que trabaja para que desaparezcas.

Racismo internalizado es olvido.

Antirracismo emocional es memoria.

Y tú estás recordando.

A veces lento. A veces con rabia. A veces con miedo.

Pero estás volviendo.

A ti.

#letters#love letters#blackhistory#blacklivesmatter#blacklivesalwaysmatter#blackhistorymonth#history#blackpeoplematter#knowyourhistory#black history is everybody's history#black history is world history#historyfacts#black history matters#power to the people#thoughts#racism#racial transformation#español#lasvidasnegrasimportan#cartas#poemas#poems and poetry#poems#black history is american history#africanheritage#heritage#black history month#african history#black history#historia

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

What They Stole from Us and What We Recovered: Cultural Memory of the African Diaspora

The suitcases that never arrived

Imagine being forced onto a ship with no known destination. You can take no luggage, no personal belongings, no language. Everything you know: your name, your religion, your songs, your rituals... all that is left behind.

This was the reality of millions of enslaved African people, whose identities were violently ripped away and scattered throughout the Americas.

The “suitcases that never arrived” is a metaphor for the cultural uprooting our ancestors experienced during the transatlantic slave trade. Not only were bodies trafficked: an attempt was made to erase entire cultures.

Stolen names, imposed surnames

One of the most symbolic acts of slavery was the loss of the African name. The enslaved were given Christian or European names as a form of domination. To lose one's ancestral surname was to lose a direct connection to family history, lineage, and the exact place of origin.

Today, many people of African descent in America cannot trace their family tree back more than a couple of generations. History was forcibly cut off, but not entirely lost.

Religions disguised to survive

African spirituality was also repressed, persecuted, or ridiculed. However, in many cases, it survived in disguise.

• In Brazil, Candomblé hid orixás (African deities) behind Catholic saints.

• In Cuba and the Caribbean, Santeria mixed Catholic symbols with Yoruba practices.

• In Haiti, Voodoo became a force of resistance, even key to the Haitian Revolution.

These religions are living memories of Africa, preserved by the cunning and cultural resilience of our ancestors.

Ancestral knowledge in the body

Not all was lost. Although the “suitcases” did not arrive, our ancestors kept culture in their bodies and practices:

• Braids served as escape maps and a hiding place for seeds and sacred objects.

• Songs and drums were forms of communication, protest, and even instructions for rebellion.

• African flavor seeped into the cuisines of the U.S. South, the Caribbean, Colombia and Brazil. Dishes like gumbo, acarajé or beans with rice have African roots.

What we are reclaiming today

The 21st century has witnessed a powerful Afro-descendant reconnection with African roots:

• DNA tests allow us to discover ethnic origins such as Wolof, Akan, Yoruba, Mandinka, among others.

• Fashion and natural hair reclaim black aesthetics as beauty and pride.

• More and more people are studying African religions, traditional languages and dances such as sabar, afrobeat or mapalé.

We are rebuilding the suitcases that were stolen from us, piece by piece, story by story.

Memory does not die. Despite centuries of attempts to erase our identity, African culture was not destroyed; it was transformed, hidden, protected and transmitted. Today, we are the bearers of that heritage, and with each act of memory, resistance and celebration, we weave anew the thread that binds us to our ancestors.

Remembering is not only an act of justice. It is also an act of love.

•••

Lo Que Nos Robaron y Lo Que Recuperamos: Memoria Cultural de la Diáspora Africana

Las maletas que nunca llegaron

Imagina que te obligan a subir a un barco sin destino conocido. No puedes llevar equipaje, ni objetos personales, ni hablar tu idioma. Todo lo que sabes: tu nombre, tu religión, tus canciones, tus rituales… todo eso queda atrás.

Esta fue la realidad de millones de personas africanas esclavizadas, cuyas identidades fueron violentamente arrancadas y esparcidas por todo el continente americano.

Las “maletas que nunca llegaron” son una metáfora del desarraigo cultural que vivieron nuestros antepasados durante la trata transatlántica de esclavos. No solo se traficaron cuerpos: se intentó borrar culturas enteras

Nombres robados, apellidos impuestos

Uno de los actos más simbólicos de la esclavitud fue la pérdida del nombre africano. A los esclavizados se les asignaban nombres cristianos o europeos como forma de dominación. Perder el apellido ancestral fue perder una conexión directa con la historia familiar, el linaje, y con el lugar exacto de origen.

Hoy, muchas personas afrodescendientes en América no pueden rastrear su árbol genealógico más allá de un par de generaciones. La historia fue cortada a la fuerza, pero no del todo perdida.

Religiones disfrazadas para sobrevivir

La espiritualidad africana también fue reprimida, perseguida, o ridiculizada. Sin embargo, en muchos casos, sobrevivió camuflada.

• En Brasil, el Candomblé ocultó orixás (deidades africanas) detrás de santos católicos.

• En Cuba y el Caribe, la Santería mezcló símbolos católicos con prácticas yoruba.

• En Haití, el Vudú se convirtió en una fuerza de resistencia, incluso clave en la Revolución Haitiana.

Estas religiones son memorias vivas de África, preservadas por la astucia y la resistencia cultural de nuestros ancestros.

Conocimiento ancestral en el cuerpo

No todo se perdió. Aunque las “maletas” no llegaron, nuestros ancestros guardaron cultura en sus cuerpos y prácticas:

• Las trenzas sirvieron como mapas de escape y escondites para semillas y objetos sagrados.

• Las canciones y tambores fueron formas de comunicación, protesta, e incluso instrucciones de rebelión.

• El sabor africano se filtró en las cocinas del sur de EE.UU., el Caribe, Colombia y Brasil. Platillos como el gumbo, el acarajé o los frijoles con arroz tienen raíces africanas.

Lo que estamos recuperando hoy

El siglo XXI ha sido testigo de una poderosa reconexión afrodescendiente con las raíces africanas:

• Las pruebas de ADN permiten descubrir orígenes étnicos como wolof, akan, yoruba, mandinga, entre otros.

• La moda y el cabello natural reivindican la estética negra como belleza y orgullo.

• Cada vez más personas estudian religiones africanas, lenguas tradicionales y bailes como el sabar, el afrobeat o el mapalé.

Estamos reconstruyendo las maletas que nos robaron, pieza por pieza, historia por historia.

La memoria no muere. Pese a siglos de intento de borrar nuestra identidad, la cultura africana no fue destruida; fue transformada, escondida, protegida y transmitida. Hoy, somos los portadores de esa herencia, y con cada acto de memoria, resistencia y celebración, tejemos de nuevo el hilo que nos une con nuestros ancestros.

Recordar no es solo un acto de justicia. Es también un acto de amor.

#lasvidasnegrasimportan#maletas#español#historia africana#historia#blackhistory#blacklivesmatter#history#blacklivesalwaysmatter#blackhistorymonth#blackpeoplematter#knowyourhistory#power to the people#black history is everybody's history#historyfacts#black history is world history#culture#black history is american history#black history month#black history matters#black history#blackhistoryyear#blackgirlmagic#historias#young gifted and black#english#spanish#education#knowlegde#black power

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blood Diamonds: The Luxury That Bleeds

A diamond has long been a symbol of love, success, and timeless beauty. Gleaming on engagement rings, nestled in velvet boxes, or gracing red carpet events, it is marketed as forever. But for millions, the story behind that sparkle is darker than any shadow it reflects.

Blood diamonds—or conflict diamonds—are more than just illicit stones mined in war zones. They are fragments of trauma, extracted from the depths of violence, corruption, and exploitation. For decades, rebel groups in countries like Sierra Leone and Angola turned diamonds into weapons, using them to finance brutal wars. Civilians were maimed, enslaved, and killed. Entire communities were destroyed so that a handful of stones could be traded for guns and power.

This is the chilling paradox of luxury: that something so beautiful can come from such unimaginable horror.

In 2003, the world responded with the Kimberley Process, a certification system designed to keep blood diamonds out of the global market. But like many well-intentioned systems, it suffers from loopholes. The definition of a “conflict diamond” is narrow, applying only to stones that directly fund rebel warfare against legitimate governments. It does not cover diamonds mined by corrupt regimes, those extracted with child labor, or those linked to environmental devastation.

As such, diamonds continue to circulate that are tainted not by war, but by systemic injustice—a quieter, more acceptable form of violence that hides behind bureaucracy and profit margins.

The modern consumer is waking up. In an era of increasing transparency, ethical sourcing is no longer a niche concern—it is a demand. Alternatives like lab-grown diamonds or stones from certified conflict-free regions (such as Canada) offer a path forward. But the burden cannot fall solely on consumers. Jewelers, corporations, and governments must bear the weight of ensuring that what they sell does not come at the cost of blood and suffering.

Ultimately, the problem of blood diamonds is not just about precious stones—it is about the structures that allow suffering to be hidden behind shine, about the cost of luxury in a world that too often forgets the invisible hands that build it.

To wear a diamond ethically is not just to know where it came from, but to care deeply about who paid the true price for its brilliance.

•••

Diamantes de Sangre: El Lujo que Sangra

Durante mucho tiempo, un diamante ha sido símbolo de amor, éxito y belleza atemporal. Brillando en anillos de compromiso, envuelto en cajas de terciopelo o adornando eventos de alfombra roja, se vende como algo eterno. Pero para millones, la historia detrás de ese brillo es más oscura que cualquier sombra que refleje.

Los diamantes de sangre —o diamantes de conflicto— son más que simples piedras extraídas ilícitamente en zonas de guerra. Son fragmentos de trauma, extraídos de las profundidades de la violencia, la corrupción y la explotación. Durante décadas, grupos rebeldes en países como Sierra Leona y Angola convirtieron los diamantes en armas, utilizándolos para financiar guerras brutales. Civiles fueron mutilados, esclavizados y asesinados. Comunidades enteras fueron destruidas para poder intercambiar un puñado de piedras por armas y poder.

Esta es la escalofriante paradoja del lujo: que algo tan hermoso pueda surgir de un horror tan inimaginable.

En 2003, el mundo respondió con el Proceso de Kimberley, un sistema de certificación diseñado para mantener los diamantes de sangre fuera del mercado global. Sin embargo, como muchos sistemas bienintencionados, sufre de lagunas legales.

La definición de "diamante de conflicto" es limitada y se aplica únicamente a las piedras que financian directamente la guerra rebelde contra gobiernos legítimos. No incluye los diamantes extraídos por regímenes corruptos, los extraídos con trabajo infantil ni los vinculados a la devastación ambiental.

De esta manera, siguen circulando diamantes contaminados no por la guerra, sino por la injusticia sistémica: una forma de violencia más discreta y aceptable que se esconde tras la burocracia y los márgenes de ganancia.

El consumidor moderno está despertando. En una era de creciente transparencia, el abastecimiento ético ya no es una preocupación de nicho, sino una demanda. Alternativas como los diamantes cultivados en laboratorios o las piedras procedentes de regiones certificadas como libres de conflictos (como Canadá) ofrecen una vía de avance. Pero la responsabilidad no puede recaer únicamente en los consumidores. Joyeros, corporaciones y gobiernos deben asumir la responsabilidad de garantizar que lo que venden no se haga a costa de sangre y sufrimiento.

En definitiva, el problema de los diamantes de sangre no se limita a las piedras preciosas, sino a las estructuras que permiten ocultar el sufrimiento tras el brillo, al coste del lujo en un mundo que, con demasiada frecuencia, olvida las manos invisibles que lo construyen.

Llevar un diamante de forma ética no se trata solo de saber de dónde proviene, sino de preocuparse profundamente por quién pagó el verdadero precio por su brillo.

#blackhistory#africanhistory365#black history is everybody's history#history#blacklivesmatter#historyfacts#black history is world history#black history is american history#african history#blackhistorymonth#blackpeoplematter#knowyourhistory#black history#historia africana#historia#blackhistoryeveryday#blackhistory365#blackhistoryfacts#blood diamond#blood diamonds#jewelry#ethicalfashion#black history month#blackhistoryyear#blackbloggers#blacklivesalwaysmatter#historic#human rights#luxury#jewels

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gertrude "Ma Rainey" Pridgett is known as the Mother of the Blues and is one of the earliest blues singers as well as one of the first generation of artists to record their work in that genre.

Though Ma Rainey sang quite a lot about men, “Prove It on Me,” according to Angela Y. Davis, “is a cultural precursor to the lesbian cultural movement of the 1970s, which began to crystallize around the performance and recording of lesbian-affirming songs."

Went out last night with a crowd of my friends,

They must've been women, 'cause I don't like no men.

Reportedly, the song refers to a 1925 incident in which Rainey was arrested for hosting an orgy at her home involving women from her chorus. Rainey also was rumored to have had a relationship with Bessie Smith, her protege. An ad for “Prove It on Me” winks at these rumors, showing Rainey mingling with women while wearing a menswear-inspired take on a woman’s suit, under the eye of a cop lurking suspiciously in the shadows.

This is remarkable not only for the openness about lesbian relationships, but the blatant nose-thumbing at law enforcement. For all the new sexual openness of the 1920s, queer sexuality was still taboo and heavily policed- even more so for Black and Brown people, and violence from law enforcement was a constant threat.

Rainey’s legacy is one of defiance, independence, larger-than-life glamor, and iconic artistry, even as her power was limited by the white, male- dominated ruthlessness of the recording industry and the confines of a similarly racist and homophobic America. Despite this, she transformed the role of women in music.

Rainey was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990 for her early influences on today's music industry.

•••

Gertrude "Ma Rainey" Pridgett es conocida como la Madre del Blues, fue una de las primeras cantantes de blues y forma parte de la primera generación de artistas en grabar su trabajo en este género.

Aunque Ma Rainey solía cantar mucho sobre hombres, “Prove It on Me”, según Angela Y. Davis, “abrió camino cultural al movimiento cultural lésbico de la década de los 70, el cual comenzó a cristalizarse en torno a la interpretación y grabación de canciones lésbico-afirmativas.”

Salí anoche con una multitud de mis amigos,

Deben haber sido mujeres, porque no me gustan los hombres.

Según se informa, la canción se refiere a un incidente de 1925 en el que Rainey fue arrestada por organizar una orgía en su casa, en la cual estaban participando mujeres de su coro. También se rumoreaba que Rainey había tenido una relación con Bessie Smith, su discípula. Un anuncio comercial de “Prove It on Me” hace un guiño a estos rumores y muestra a Rainey fraternizando con mujeres mientras usa una versión masculina de un traje de mujer, bajo la mirada de un policía que le está acechando sospechosamente desde las sombras.

Esto es destacable y no sólo por la franqueza sobre las relaciones lésbicas, sino también por la obvia crítica a las autoridades. A pesar de toda la nueva transparencia sexual de la década de 1920, la homosexualidad todavía era un tabú y estaba fuertemente vigilada (aún más para las personas negras y de color), y la violencia por parte de las fuerzas policiales era una amenaza constante.

El legado de Rainey es uno de desafío, independencia, glamour descomunal y arte icónico, incluso cuando su poder estaba limitado por la crueldad de los hombres blancos de la industria discográfica y los confines de un país (Estados Unidos) igualmente racista y homofóbico. A pesar de ello, transformó el rol de la mujer en la industria musical.

Rainey fue incluida póstumamente en el Salón de la Fama del Rock and Roll en 1990 por sus influencias en la industria musical actual.

#blackmusicmatters#black musicians#black music#black music month#pride month#lesbian pride#happy pride 🌈#happy pride

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

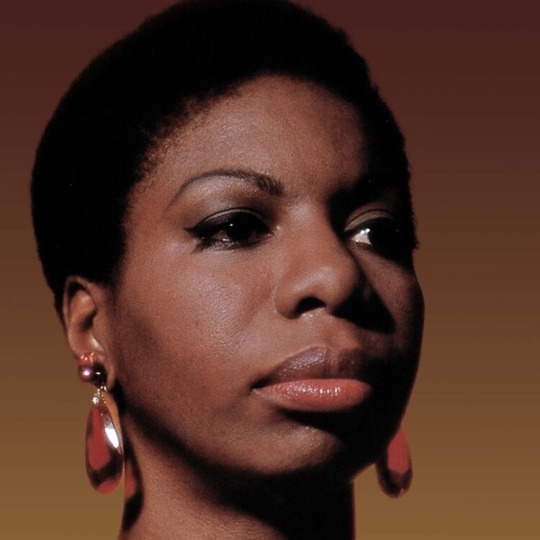

Influenced by the civil rights movement in the 1960s, Simone became known as the “Singer of the Black Revolution.” She composed and recorded a number of songs with political protest themes including “To Be Young, Gifted and Black,” “Old Jim Crow,” “Why? (The King of Love Is Dead),” “Backlash Blues” and “Mississippi Goddam.”

Simone also collaborated with friends Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, and Lorraine Hansberry to financially support the movement and took part in marches and spoke and performed at civil rights rallies.

•••

Influenciada por el movimiento por los derechos civiles de la década de 1960, Simone se dio a conocer como la "Cantante de la Revolución Negra". Compuso y grabó varias canciones con temas de protesta política, como "To Be Young, Gifted and Black", "Old Jim Crow", "¿Por qué? (El Rey del Amor Ha Muerto)", "Backlash Blues" y "Mississippi Goddam".

Simone también colaboró con sus amigos Langston Hughes, James Baldwin y Lorraine Hansberry para apoyar económicamente el movimiento, participó en marchas, habló e hizo presentaciones en protestas por los derechos civiles.

#blackhistory#history#blackhistorymonth#knowyourhistory#black history is everybody's history#historyfacts#blacklivesmatter#black history is world history#black history is american history#nina simone#black musicians#musicians#black music matters#music#black music#black music month#blacklivesalwaysmatter#blackpeoplematter#singer#english#spanish#share#culture#blackhistoryyear#black history#black history month#blackownedandoperated#black history matters#knowledgeispower#knowledgeisfree

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zumbi dos Palmares was a Brazilian Quilombola leader of a group of Afro-Brazilians who lived in maroon communities known as quilombos. He was the last king of the Quilombo dos Palmares, the largest of the quilombos founded by escaped enslaved Afro-Brazilians in what is now Alagoas, Brazil. Zumbi was born in 1655 to a woman named Sabina and an unnamed father in what is today União dos Palmares, Alagoas.

At the age of six, Zumbi was captured by the Portuguese and given to a missionary, Father Antônio Melo who baptized him with the Christian name, Francisco, and taught him Portuguese, Latin, and the Catholic sacraments. Despite this religious upbringing, Zumbi eventually returned to Palmares in 1670 at the age of 15. By then, he was already known for his physical prowess and tactical skill in battle. In his early twenties, he had earned a reputation as a respected military strategist. In 1675, he became commander-in-chief of Palmares’ armed forces.

In 1678, during a power struggle, Zumbi killed his uncle, Ganga Zumba, who was then king of Palmares. One reason for this conflict was Ganga Zumba’s willingness to accept a peace offer from Pedro de Almeida, the Portuguese governor of Pernambuco. The deal granted freedom to runaway slaves who submitted to Portuguese rule. Zumbi opposed the offer, believing that no true freedom existed as long as slavery continued elsewhere in Brazil. He rejected Almeida’s proposal and challenged Ganga Zumba’s leadership, which led to the latter’s death, possibly by poisoning.

After assuming the kingship, Zumbi intensified the resistance against Portuguese forces. Between 1680 and 1686, the Portuguese launched six military expeditions against Palmares, all of which failed. However, in 1694, Portuguese forces under commanders Domingos Jorge Velho and Bernardo Vieira de Melo and assisted by Indigenous Brazilian fighters, mounted a massive assault. After 42 days of fighting, they destroyed the central settlement of Palmares, called Cerca do Macaco, on February 6, 1694.

Zumbi continued to resist but was eventually captured and killed on November 20, 1695. He was decapitated, and his head was displayed on a pike as a warning to others. Despite his death, Zumbi became a legendary figure in Brazilian folklore. Many enslaved people believed he was a demigod and that his strength came from being possessed by Orixás, deities associated with the Yoruba religion of West Africa. Some believed he was the son of Ogum, a Yoruba Orisha linked to war and iron.

Today, Zumbi is remembered as a hero and a symbol of Black resistance. His death is commemorated annually on November 20, celebrated as Black Consciousness Day (Dia da Consciência Negra), honoring his fight for freedom and justice.

•••

Zumbi dos Palmares fue un líder quilombola brasileño de un grupo de afrobrasileños que vivían en comunidades cimarronas conocidas como quilombos. Fue el último rey del Quilombo dos Palmares, el mayor de los quilombos fundado por afrobrasileños esclavizados que escaparon de la esclavitud en lo que hoy es Alagoas, Brasil. Zumbi nació en 1655, hijo de una mujer llamada Sabina y un padre anónimo, en lo que hoy es União dos Palmares, Alagoas.

A los seis años, Zumbi fue capturado por los portugueses y entregado a un misionero, el padre Antônio Melo, quien lo bautizó con el nombre cristiano de Francisco y le enseñó portugués, latín y los sacramentos católicos. A pesar de su formación religiosa, Zumbi finalmente regresó a Palmares en 1670 a los 15 años. Para entonces, ya era conocido por su destreza física y su habilidad táctica en la batalla. A sus veinte años, se había ganado una reputación como un respetado estratega militar. En 1675, se convirtió en comandante en jefe de las fuerzas armadas de Palmares.

En 1678, durante una lucha de poder, Zumbi asesinó a su tío, Ganga Zumba, quien en ese entonces era rey de Palmares. Una de las razones de este conflicto fue la disposición de Ganga Zumba a aceptar una oferta de paz de Pedro de Almeida, gobernador portugués de Pernambuco. El acuerdo otorgaba la libertad a los esclavos fugitivos que se sometieran al dominio portugués. Zumbi se opuso a la oferta, creyendo que no existía verdadera libertad mientras la esclavitud continuara en otras partes de Brasil. Rechazó la propuesta de Almeida y cuestionó el liderazgo de Ganga Zumba, lo que provocó su muerte, posiblemente por envenenamiento.

Tras asumir el trono, Zumbi intensificó la resistencia contra las fuerzas portuguesas. Entre 1680 y 1686, los portugueses lanzaron seis expediciones militares contra Palmares, todas ellas fallidas. Sin embargo, en 1694, las fuerzas portuguesas, al mando de los comandantes Domingos Jorge Velho y Bernardo Vieira de Melo, con la ayuda de combatientes indígenas brasileños, lanzaron un asalto masivo. Tras 42 días de combate, destruyeron el asentamiento central de Palmares, llamado Cerca do Macaco, el 6 de febrero de 1694.

Zumbi continuó resistiéndose, pero finalmente fue capturado y asesinado el 20 de noviembre de 1695. Fue decapitado y su cabeza fue exhibida en una pica como advertencia. A pesar de su muerte, Zumbi se convirtió en una figura legendaria del folclore brasileño. Muchos esclavos creían que era un semidiós y que su fuerza provenía de estar poseído por orixás, deidades asociadas con la religión yoruba de África Occidental. Algunos creían que era hijo de Ogum, un orisha yoruba vinculado a la guerra y el hierro.

Hoy, Zumbi es recordado como un héroe y un símbolo de la resistencia negra. Su muerte se conmemora anualmente el 20 de noviembre, Día de la Conciencia Negra, en honor a su lucha por la libertad y la justicia.

#blackhistory#history#blacklivesalwaysmatter#blacklivesmatter#blackhistorymonth#blackpeoplematter#knowyourhistory#black history matters#black history is everybody's history#historyfacts#black history is world history#black history is american history#black history month#black history#brazil#brasil#south america#black power#power to the people#culture#blackhistoryyear#blackownedandoperated#blackbloggers#historia#lasvidasnegrasimportan#blackheroesmatter#heritage#heroes#knowledgeispower#knowledge

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton was a blues singer and songwriter whose recordings of “Hound Dog” and “Ball ‘n’ Chain” later were transformed into huge hits by Elvis Presley and Janis Joplin.

She was born on December 11, 1926 outside of Montgomery in rural Ariton, Alabama. Her father was a Baptist minister and her mother was a church singer in his congregation. Thornton’s mother died when the singer was 14, and she left home to pursue a career as an entertainer. She joined the Georgia-based Hot Harlem Revue as an accomplished singer, drummer, and harmonica player and spent seven years as a regular performer throughout the South. Following her years as a traveling blues singer, Thornton moved to Houston in 1948 to begin her recording career.

In Houston, Thornton joined Don Robey’s Peacock Records in 1951, often working closely with fellow label artist Johnny Otis.

One of Thornton’s earliest and most popular recorded tracks was “Hound Dog,” initially released by Peacock in 1953. Thornton’s version of “Hound Dog” topped the R&B charts for seven weeks and sold over two million copies nationwide. Though the song brought acclaim to Thornton, it only yielded her about $500. The song became even more popular as Elvis Presley’s first hit record in 1956.

•••

Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton fue una cantante y compositora de blues cuyas grabaciones “Hound Dog” y “Ball ‘n’ Chain” luego fueron transformadas en grandes éxitos por Elvis Presley y Janis Joplin.

Nació el 11 de diciembre de 1926 en las afueras de Montgomery, en la zona rural de Ariton, Alabama. Su padre era pastor bautista y su madre, cantante en su congregación. La madre de Thornton falleció cuando la cantante tenía 14 años, y ella abandonó el hogar para dedicarse al arte. Se unió a la Hot Harlem Revue, con sede en Georgia, como una cantante, baterista y armonicista, y pasó siete años presentándose con regularidad por todo el sur. Tras sus años como cantante de blues, Thornton se mudó a Houston en 1948 para comenzar su carrera discográfica.

En Houston, Thornton se unió a Peacock Records de Don Robey en 1951, trabajando a menudo en estrecha colaboración con su colega y artista de sello, Johnny Otis.

Una de las primeras y más populares canciones grabadas por Thornton fue "Hound Dog", publicada inicialmente por Peacock en 1953. Su versión de "Hound Dog" encabezó las listas de R&B durante siete semanas y vendió más de dos millones de copias en todo el país. Aunque la canción le trajo gran éxito a Thornton, solo le ganó unos 500 dólares. La canción se hizo aún más popular al convertirse en el primer éxito de Elvis Presley en 1956.

#blacklivesmatter#blacklivesalwaysmatter#blackhistorymonth#blackpeoplematter#knowyourhistory#history#blackhistory#black history is everybody's history#historyfacts#black history matters#black history is world history#black history is american history#black history month#black musicians#black music#musician#music#musicians#black music matters#r&b music#r&b/soul#janis joplin#elvis presley#blackhistoryyear#culture#knowledgeispower#knowledgeisfree#black excellence#blackownedandoperated#historia

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

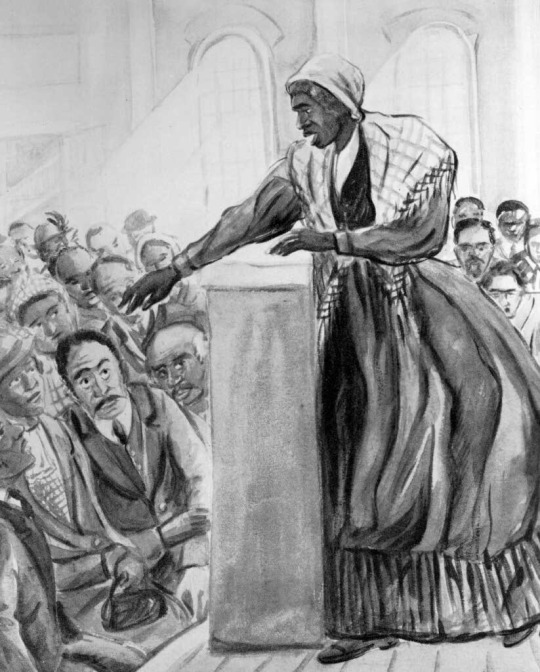

Many of us know Sojourner Truth as an abolitionist and activist for women’s rights. However, many don’t know that Sojourner escaped slavery with her infant daughter in 1826. She then discovered that her 5-year-old son, Peter, was illegally sold to an enslaver in Alabama, and Sojourner sued her former owner to gain custody of her son. She won her case, becoming one of the first Black women to sue a white man in court and win. She went on to pursue her work as an abolitionist and activist and delivered the speech she became famous for, “Ain’t I A Woman?”

•••

Muchos conocemos a Sojourner Truth como abolicionista y activista por los derechos de las mujeres. Sin embargo, muchos desconocen que Sojourner escapó de la esclavitud con su hija pequeña en 1826. Luego descubrió que su hijo de 5 años, Peter, había sido vendido ilegalmente a un esclavista en Alabama, y demandó a su antiguo dueño para obtener la custodia de su hijo. Ganó el caso, convirtiéndose en una de las primeras mujeres negras en demandar a un hombre blanco y ganar. Continuó su labor como abolicionista y activista, y pronunció el discurso por el que se hizo famosa: “¿Acaso no soy una mujer?".

#happy mother's day#motherhood#black mothers#mothers#mothers day#blackhistory#black history is everybody's history#historyfacts#black history is world history#black history is american history#history#blackgirlmagic#black excellence#sojourner truth#blacklivesmatter#blackhistorymonth#knowyourhistory#culture#knowledgeispower#knowledgeisfree#knowledge#blackpeoplematter#blackwomenmatter#black women matter#power to the people#blacklivesalwaysmatter#black liberation#black lives are precious#historia#diadelamadre

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Brown was a controversial figure who played a major role in leading the United States to civil war. He was a devout Christian and lifelong abolitionist who tried to eradicate slavery from the United States through increasingly radical means. Unlike most abolitionists, Brown was not a pacifist, and he came to believe that violence was necessary to dislodge slavery. He engaged in violent battles with pro-slavery citizens in Kansas and Missouri and led a raid on the federal munitions depot at Harper’s Ferry. Although the raid failed spectacularly, it helped precipitate the Civil War and turned Brown into a martyr for the abolitionist cause.

John Brown was born in Torrington, Connecticut, on May 9, 1800, into a deeply religious family. The family was led by a staunchly anti-slavery father, Owen Brown, who was an agent for the Underground Railroad. Brown grew up in a frontier Ohio town in which whites were the minority and where his father taught him that all people should be treated equally. When Brown was 12, he witnessed the beating of a slave boy. This violence had a profound impact on him and helped lead him to his fanatical opposition to slavery.

In 1851, he established the League of Gileadites, an organization that worked to protect escaped slaves from slave hunters.

After Congress passed the Kansas and Nebraska Act in 1854, five of Brown’s sons left for Kansas, and he joined them the following year. He and his sons were heavily involved in “Bleeding Kansas,” defending the city of Lawrence, Kansas, against pro-slavery raiders from Missouri. Brown then led a raid into the pro-slavery town of Pottawatomie Creek, Missouri, during which five pro-slavery men were killed.

On October 16, 1859, he and 21 men raided the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, on the theory that slaves would rise up against their masters when word spread of Brown’s actions. Although Brown gained control of the arsenal, the slave rebellion failed to materialize. Brown’s rebellion was swiftly crushed when U.S. Army Colonel Robert E. Lee and 100 Marines surrounded him. Brown was captured, quickly tried, and convicted of treason. He was hanged on December 2, 1859.

His execution was marked by the tolling of bells at many northern churches, and Brown’s actions were looked upon increasingly favorably in the North as the nation headed towards civil war. A song, “John Brown’s Body,” was written about him and was popular in the North during the Civil War. Julia Ward Howe would use the same tune when she wrote the words to the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

•••

John Brown fue una figura controvertida que desempeñó un papel fundamental en la guerra civil de Estados Unidos. Fue un cristiano devoto y abolicionista de toda la vida que intentó erradicar la esclavitud del país mediante métodos cada vez más radicales. A diferencia de la mayoría de los abolicionistas, Brown no era pacifista y llegó a creer que la violencia era necesaria para erradicar la esclavitud. Participó en violentos enfrentamientos con ciudadanos esclavistas en Kansas y Misuri y dirigió un asalto al depósito federal de municiones de Harper's Ferry. Aunque el asalto fracasó, contribuyó a precipitar la Guerra Civil y convirtió a Brown en un mártir de la causa abolicionista.

John Brown nació en Torrington, Connecticut, el 9 de mayo de 1800, en el seno de una familia profundamente religiosa. La familia estaba liderada por un padre firmemente antiesclavista, Owen Brown, quien era agente del Ferrocarril Subterráneo. Brown creció en un pueblo fronterizo de Ohio donde los blancos eran minoría y donde su padre le enseñó que todas las personas debían ser tratadas por igual. A los 12 años, Brown presenció la paliza de un niño esclavo. Esta violencia lo impactó profundamente y lo condujo a su oposición fanática a la esclavitud.

En 1851, fundó la Liga de Galaaditas, una organización que trabajaba para proteger a los esclavos fugitivos de los cazadores de esclavos.

Tras la aprobación por el Congreso de la Ley de Kansas y Nebraska en 1854, cinco de los hijos de Brown se fueron a Kansas, y él se unió a ellos al año siguiente. Él y sus hijos participaron activamente en el "Sangrado de Kansas” , defendiendo la ciudad de Lawrence, Kansas, contra los invasores esclavistas de Misuri. Brown lideró entonces un ataque en la ciudad esclavista de Pottawatomie Creek, Misuri, durante la cual murieron cinco hombres esclavistas.

El 16 de octubre de 1859, él y 21 hombres asaltaron el arsenal federal de Harper's Ferry, Virginia, bajo la teoría de que los esclavos se rebelarían contra sus amos al correrse la voz de las acciones de Brown. Aunque Brown tomó el control del arsenal, la rebelión de esclavos no se materializó. La rebelión de Brown fue rápidamente aplastada cuando el coronel del ejército estadounidense Robert E. Lee y 100 marines lo rodearon. Brown fue capturado, juzgado rápidamente y condenado por traición. Fue ahorcado el 2 de diciembre de 1859.

Su ejecución se celebró con el repique de campanas en muchas iglesias del norte, y las acciones de Brown fueron cada vez más bien vistas en el Norte a medida que la nación se encaminaba hacia la guerra civil. Se escribió una canción sobre él, "El cuerpo de John Brown", que fue popular en el Norte durante la Guerra Civil. Julia Ward Howe usaría la misma melodía al escribir la letra del "Himno de Batalla de la República".

#john brown#the good lord bird#black history is everybody's history#historyfacts#black history is world history#history#blackhistorymonth#blackhistory#blackpeoplematter#slavery#anti slavery#blacklivesalwaysmatter#blacklivesmatter#black history#black history is american history#black history matters#black history month#historia#historic#abolitionist#knowyourhistory#culture#blackhistoryyear#blackownedandoperated#black lives matter#black tumblr#knowledgeispower#knowledgeisfree#knowlegde#Kansas

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Afeni Shakur was a political activist, Black Panther, philanthropist, businesswoman and Mother to the Late Tupac Shakur.

In April 1969, she and 20 other Black Panthers were arrested and charged with 150 charges of "Conspiracy against the United States government and New York landmarks".

Shakur chose to represent herself in court, pregnant while on trial and facing a 300-year prison sentence and had not attended law school. Shakur interviewed witnesses and argued in court.

One of the people Shakur cross-examined was Ralph White, one of the three suspects that actually was an undercover agent.

White was someone whom she had suspected all along of being a cop, since he had been inciting others to violence. She got White to admit under oath that he and the other two agents had organized most of the unlawful activities. She also got White to admit to the court that the activism that they had done together was "powerful, inspiring, and ….. beautiful".

Shakur asked Mr. White if he had misrepresented the Panthers to his police bosses. He said "Yes”. She asked if he had betrayed the community. He said "Yes."

VERDICT:

She and the others in the "Panther 21" were acquitted in May 1971 after an 8-month trial.

Altogether, Afeni Shakur spent 2 years in jail before being acquitted.

Tupac was born a month later.

May 2, 2016: Afeni Shakur died of a heart attack in Sausalito, California.

•••

Afeni Shakur fue una activista política, Pantera Negra, filántropa, empresaria y madre del fallecido Tupac Shakur.

En abril de 1969, ella y otros veinte Panteras Negras fueron arrestados y acusados de 150 cargos de "Conspiración contra el gobierno de los Estados Unidos y los monumentos de Nueva York".

Shakur decidió representarse a sí misma en el tribunal, pues estaba embarazada durante el juicio y se enfrentaba a una condena de 300 años de prisión. Sin haber estudiado derecho, Shakur entrevistó a testigos y argumentó ante el tribunal.

Una de las personas a las que Shakur interrogó fue Ralph White, uno de los tres sospechosos que en realidad era un agente encubierto.

White era alguien de quien ella siempre había sospechado que era policía, ya que había estado incitando a otros a la violencia. Logró que White admitiera bajo juramento que él y los otros dos agentes habían organizado la mayoría de las actividades ilegales. También logró que White admitiera ante el tribunal que el activismo que habían llevado a cabo juntos era "poderoso, inspirador y... hermoso".

Shakur le preguntó al Sr. White si había distorsionado la imagen de las Panteras ante sus jefes policiales. Él respondió: «Sí». Ella le preguntó si había traicionado a la comunidad. Él respondió: «Sí».

VEREDICTO:

Ella y los demás de las "21 Panteras" fueron absueltos en mayo de 1971 después de un juicio de 8 meses.

En total, Afeni Shakur pasó 2 años en la cárcel antes de ser absuelta.

Tupac nació un mes después.

2 de mayo de 2016: Afeni Shakur murió de un ataque cardíaco en Sausalito, California.

#tupac shakur#2pac shakur#2pac amaru shakur#Shakur#afeni shakur#black panthers#history#black history is everybody's history#historyfacts#black history is world history#black history is american history#black history#blacklivesmatter#blacklivesalwaysmatter#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth#black history matters#black history month#historia#new york#blackownedandoperated#knowyourhistory#blackhistoryyear#culture#black queen#black power#black panther#black lives matter#blackwomenmatter#blackgirlmagic

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Zong Massacre (1781)

On September 6, 1781, the slave ship Zong sailed from Africa with around 442 enslaved Africans. Back then, slaves were a valuable 'commodity' so they often captured more than the ship could handle to maximize profits.

Ten weeks later, around November 1781, the Zong arrived at Tobago, then proceeded toward St. Elizabeth, but deviated from its route near Haiti. At that stage, water shortages, illness, and fatalities among the crew, combined with poor leadership decisions, caused chaos.

By end of November about 62 Africans had died from either disease or malnutrition. The Zong then sailed in an area in the Atlantic known as "the Doldrums" notorious for stagnant winds.

Stranded there, illness ravaged the ship, claiming over 50 more lives as conditions worsened.

Desperate as they ran out of water, Luke Collingwood, captain of the ship decided to "jettison" some of the cargo in order to save the ship & provide its owners the opportunity to claim insurance.

Children, women and men were forced off the ship and left to drown. Some of the men handcuffed and had iron balls tied to their ankles. About 10 Africans jumped rather than be pushed by the crew. By December 22, about 208 Africans arrived alive, a mortality rate of 53%.

Upon the Zong's arrival in Jamaica, James Gregson, the ship's owner, filed an insurance claim for their loss. Gregson stated that Zong didn't have enough water to sustain the crew & Africans.The underwriter, Thomas Gilbert, disputed the claim citing the ship did have enough water.

Despite this the Jamaican court in 1782 found in favour of the owners. The African were reduce to "horses" & "cargo" while it cause outrage against anti-slavery proponents. It would be years for the event to be termed what it is really: a massacre.

•••

Masacre del Zong (1781)

El 6 de septiembre de 1781, el barco Zong zarpó de África con alrededor de 442 africanos esclavizados. En aquel entonces, los esclavos eran una mercancía valiosa, por lo que a menudo capturaban más de lo que el barco podía manejar para maximizar las ganancias.

Diez semanas después, alrededor de noviembre de 1781, el Zong llegó a Tobago y luego prosiguió hacia Santa Isabel, pero se desvió de su ruta cerca de Haití. En ese momento, la escasez de agua, las enfermedades y las muertes entre la tripulación, sumadas a las malas decisiones de liderazgo, causaron el caos.

A finales de noviembre, unos 62 africanos habían muerto por enfermedad o desnutrición. El Zong navegó entonces por una zona del Atlántico conocida como "las calmas ecuatoriales", conocida por sus vientos paralizantes.

Encallado allí, la enfermedad azotó el barco, cobrándose más de 50 vidas a medida que las condiciones empeoraban. Desesperado mientras que se quedaban sin agua, Luke Collingwood, capitán del barco, decidió deshacerse de parte de la carga para salvar el barco y dar a los dueños la oportunidad de reclamar el seguro. Niños, mujeres y hombres fueron obligados a bajar del barco y fueron abandonados a su suerte. Algunos hombres fueron esposados y tenían bolas de hierro atadas a los tobillos. Unos 10 africanos saltaron en lugar de ser empujados por la tripulación. Para el 22 de diciembre, unos 208 africanos llegaron con vida. La tasa de mortalidad fue de 53%.

A la llegada del Zong a Jamaica, James Gregson, propietario del barco, presentó un reclamo al seguro por la pérdida. Gregson declaró que el Zong no tenía suficiente agua para la tripulación y los africanos. El asegurador, Thomas Gilbert, rechazó el reclamo alegando que el barco sí tenía suficiente agua.

A pesar de esto, el tribunal jamaiquino falló a favor de los propietarios. Los africanos fueron reducidos a "caballos" y "carga", lo que provocó indignación entre los defensores anti-esclavitud. Pasaron años para que el acontecimiento fuera calificado como lo que realmente es: una masacre.

#blackhistory#history#blacklivesalwaysmatter#black history is everybody's history#black history matters#historyfacts#black history is world history#black history is american history#black history month#black history#african history#jamaica#blackhistorymonth#blacklivesmatter#culture#knowyourhistory#blackhistoryyear#knowledgeispower#power to the people#blackpeoplematter#africanhistory365#africanhistory#blackownedandoperated#knowlegde#share#blackbloggers#black community#english#spanish#follow

312 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is José Lino Álvarez Sambulá?

José Lino Álvarez Sambulá (born in 1937 in Sangrelaya, Honduras) is a Honduran professor, lawyer, and activist recognized for his work on behalf of Garifuna communities and his contributions to the country's education and cultural spheres. He founded the National Garifuna Ballet, initially known as the Afro-Honduran Cultural and Dance Group, which aimed to preserve and promote Garifuna culture through music and dance.

In addition to his cultural work, Álvarez Sambulá has had a distinguished career in education and unions. He served as the first president of the Honduran Secondary Education Teachers' Association (COPEMH) from 1963 to 1971, where he worked to defend teachers' rights and improve the Honduran education system.

His commitment to social struggles and the defense of the rights of Garifuna communities have left a significant mark on the history of Honduras, consolidating his position as a key figure in promoting Afro-descendant identity and culture in the country.

¿Quién es José Lino Álvarez Sambulá?

José Lino Álvarez Sambulá (nacido en 1937 en Sangrelaya, Honduras) es un profesor, abogado y activista hondureño reconocido por su labor en favor de las comunidades garífunas y su contribución al ámbito educativo y cultural del país. Fue el fundador del Ballet Nacional Garífuna, inicialmente conocido como el Grupo Cultural y de Danzas Afro Hondureñas, con el objetivo de preservar y promover la cultura garífuna a través de la música y la danza.

Además de su labor cultural, Álvarez Sambulá ha tenido una destacada carrera en el ámbito educativo y sindical. Se desempeñó como el primer presidente del Colegio de Profesores de Educación Media de Honduras (COPEMH) entre 1963 y 1971, donde trabajó en la defensa de los derechos de los docentes y en la mejora del sistema educativo hondureño.

Su compromiso con las luchas sociales y la defensa de los derechos de las comunidades garífunas han dejado una huella significativa en la historia de Honduras, consolidándolo como una figura clave en la promoción de la identidad y cultura afrodescendiente en el país.

#garifuna#garifunalivesmatter#hero#social justice#leadership#leader#education#law#knowyourhistory#knowledgeisfree#african heritage#africanhistory365#historia africana#herencia africana#mes de la herencia africana#africanhistory#africanheritage#history#honduras#honduran#black education#blackhistory#blackhistoryeveryday#blackhistoryyear#blackhistoryfacts#blackhistory365#black history#blackhistorymonth#black history is everybody's history#historyfacts

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barauda: The Legendary Warrior of the Garifuna People

Barauda is an emblematic figure in the history of the Garifuna people. She’s remembered as a courageous woman who led the resistance against colonization and slavery in the Caribbean. Her story blends reality and legend, making her a symbol of struggle, strength, and pride for the Garifuna community.

She was a woman of African and Arawak descent, part of the Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples who formed the Garifuna culture. According to oral history, she was born on the island of Saint Vincent in the Caribbean during the 18th century, a time when European powers were attempting to dominate and enslave the local populations.

From a young age, she stood out for her leadership and courage, earning the respect of her community. She became a fierce warrior and strategist, leading the defense of the Garifuna people against the colonizers.

During the 18th century, the French and British attempted to control the island of Saint Vincent, where the Garifuna (also known as Black Carib) lived. The British, in particular, sought to subdue this population, but the Garifuna resisted with all their might.

Barauda became one of the leaders of this resistance. She is said to have fought alongside Joseph Chatoyer, the principal Garifuna chief, and participated in several battles against the British. With her intelligence and military skills, she helped organize ambushes and strategies to protect her people.

However, after years of war, the British finally captured St. Vincent in 1796. Many Garifuna were killed or exiled to the island of Roatán, Honduras. Although there are no clear records of Barauda's fate, it is believed that she may have been captured or that she continued the resistance even after her exile.

Today, Barauda remains a symbol of resistance among the Garifuna people, and her story is taught to keep alive the memory of those who fought for freedom.

•••

Barauda: La Guerrera Legendaria del Pueblo Garífuna

Barauda es una figura emblemática dentro de la historia del pueblo garífuna, recordada como una mujer valiente que lideró la resistencia contra la colonización y la esclavitud en el Caribe. Su historia se mezcla entre la realidad y la leyenda, convirtiéndola en un símbolo de lucha, fuerza y orgullo para la comunidad garífuna.

Era una mujer de origen africano y arawak, parte de los pueblos indígenas y afrodescendientes que formaron la cultura garífuna. Según la historia oral, nació en la isla de San Vicente, en el Caribe, durante el siglo XVIII, en una época en la que las potencias europeas intentaban dominar y esclavizar a las poblaciones locales.

Desde joven, se destacó por su liderazgo y valentía, ganándose el respeto de su comunidad. Se convirtió en una guerrera feroz y estratega, liderando la defensa del pueblo garífuna contra los colonizadores.