#11th century BCE

Text

Funerary figurines

* Shabti of Paankh with inscription on cursive script. Bakerd clay, New Kingdom, 19th dynasty (1292-1190 BCE)

* Two shabtis of Userhat, scribe of Amon. Faience, New Kingdom, 19th-20th dynasty (1292-1076 BCE)

* Turin Egyptian Museum

Turin, June 2023

#Egypt#figurine#ancient#funerary#art#faience#ancient colours#13th century BCE#12th century BCE#11th century BCE#Turin Egyptian Museum#my photo

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

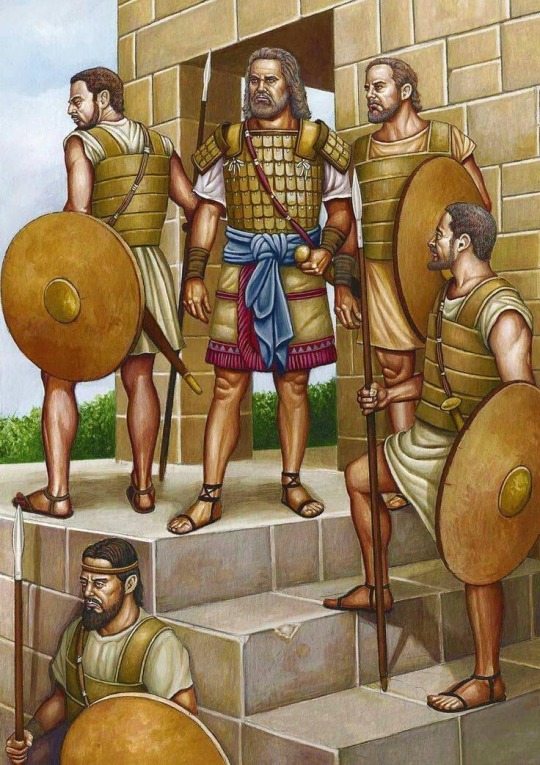

King David and his warriors 11 century BC.

#secular-jew#israel#jewish#judaism#israeli#jerusalem#diaspora#secular jew#secularjew#islam#indigenous#indigeneity#king David#bce#11th century bce#Hamas#never again#hamas is isis#10 7 23

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random thought brought on by seeing a veterinarian sign on the drive to Coffee Land, but I think Jesus would really appreciate people localizing his parable of the Good Samaritan.

Because, like, it's a good story, right? When the administrator-guy and the holy man wouldn't help the injured, the Samaritan went out of their way to make sure the injured man was able to get the help they needed, paid out of their own pocket. And that's good and all, but what even is a Samaritan? Do you know?

Well, they're a ethnoreligious group from northern Israel who follow Samaritanism, which split from Judaism sometime around the 11th century BCE. There's only about a thousand of them left. But around the time of Jesus, they were not very popular with your average Hebrew. Remember the Seleucid empire that was oppressing jews? There's a yearly celebration about it, involving a candle that lasted for 8 nights. Yeah. So at the time the Samaritans had taken the opportunity to point out they're not Jewish, they're Samaritans, so they wouldn't be persecuted. So they were seen as, like, selling out their brothers and sisters in the faith. Then by the time the Romans took over the whole area, the province of Judaea contained Samaria.

So basically the Jews and the seen-to-have-sold-them-out Samaritans were stuck in the same province, thanks to some Romans consolidating the areas they'd conquered. Tensions between the two groups were high, and I don't imagine either of them liked each other very much at all.

To a Jew of the first century CE, a Samaritan is basically the worst kind of person you could be, and that's exactly why Jesus used them in the parable of the Good Samaritan!

The parable isn't about Samaritans. It's about how the worst person you can imagine is a better person than the people you idolize and uplift, if that person takes care of their fellow man. It's about how you should love your neighbor as yourself, and who is your neighbor? Everyone. All people are your neighbors. Help them when they need help!

And that's why I say it should really be localized. You should tell this parable differently than it was told in AD 29 or whenever. Do you hate Samaritans? Probably not! You probably barely know who they are, even after I did some explaining up there. So why use them as your example? If Jesus was here, I don't think he would have done that.

So like, if you were giving a sermon on the good Samaritan in the 1960s to a white church, you should be like "so the policeman walked past, and the pastor walked past, but then a poor black guy saw the injured man, and got him help at the local hospital."

In the 80s, his rescuer is Soviet. In the 2000s, they're a Muslim, from Afghanistan or Iran.

Today? Maybe they're trans.

As an American, there's been many times that "Mexican" would have been the best choice. Maybe even today, especially if you specifically make them an undocumented migrant.

But yeah, the point is that you pick the group of people most hated by the audience you're talking to, and make the point that THEY ARE A BETTER PERSON THAN YOU and ALL THOSE YOU UPHOLD AS PILLARS OF THE COMMUNITY if they help their fellow man. If your worst enemy is lying injured in the street, you call the ambulance, you pay their doctor, you get them help. That's what Jesus says you should do. That's loving your neighbor, that's the Great Commandment.

And in the Roman province of Judea back in the first half of the first century, when talking to a Jewish audience, that meant the rescuer was a Samaritan helping a Jew. That was just the context for that one particular telling of the story. It shouldn't be told the same way today, or in the future. It should be an evolving parable, always changing, always adjusting the nationalities and situations and genders and everything. It's not a story about a specific event, it doesn't pretend to be history, it's a metaphorical lesson about what makes you a good person.

This parable is basically in the form of an "X, Y and Z walk into a bar" joke, and just like jokes, it should be updated over time. Those don't stay funny though the decades, as cultural attitudes shift. And this parable hasn't been updated in nearly two millenia, so it's long overdue.

#Biblical ranting#I'm not a Christian but I was raised as one so I still occasionally have Bible Thoughts

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Lotus Chalice

Egyptian, 13th-11th century BCE (New Kingdom-Third Intermediate Period)

Lotus chalices such as this one were probably used in both rituals and daily life. The vessel's shape imitates the blue lotus flower, which was a type of water lily.

163 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Historical Fiction of Mesopotamia

Historical fiction is frequently dated to works including the Iliad of Homer (8th century BCE) or The Tale of Genji (11th century CE) or, in English, to the 19th century, usually to the works of Sir Walter Scott, but the genre has more ancient origins dating back to the 2nd millennium BCE through Mesopotamian naru literature.

Continue reading...

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

I keep seeing a post going around saying that people should stop using the “colonized” names for cities in Israel/Palestine and should instead use the Arabic names.

I need you guys to be so for real right now, Hebrew is quite literally the indigenous language of the area. Like believe what you want about Israel, but Hebrew objectively and factually originated in that land. The earliest record of written Hebrew is the Khirbet Qeiyafa inscription, found near Beit Shemesh which dates back to the 11th-10th century BCE.

The first record of the name Jerusalem is in the Egyptian Execration Texts which date back to the 20th century BCE.

Arabic was introduced to the land in the 7th century CE. The first recorded use of “Al-Quds” was in the 9th century CE.

I could do this for every single ancient city in the land. Bethlehem, Hebron, Jericho, Jaffa, Beer Sheva, Acre, and Ashkelon all existed prior to the Arab conquests in the 7th century CE and the introduction of Arabic to the land.

The fact that we use the Hebrew names of these cities isn’t some conspiracy to make them sound “more Jewish”, the modern Hebrew names are direct descendants of the ancient Canaanite words for these places. Hebrew is the only surviving Canaanite language.

Believe what you want about Israel, but claiming that the Hebrew names for these cities are “colonial” names is a disgusting erasure of Jewish history in the land.

#israel#jews#jewish#hebrew#arabic#israel palestine conflict#palestine#I have a feeling I’m gonna get hate for this but honestly I had to say something#y’all are willingly spreading pan-Arabist propaganda

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

You have no idea how excited I am that after ages of no non-Joseon sageuks (and barely any sageuks at all), we have three and a half pre-Joseon ones coming that I know of:

Goryeo-Khitan War - coming in November, set in 11th century Goryeo, my most anticipated

Queen Woo - coming next year (is already filming), set in second century Goguryeo, that cast is SICK (and on a shallow note, any drama that gives me Ji Chang Wook, Kim Mu Yeol, and Lee Soo Kyuk in ancient gear with all that gorgeous hair doesn’t even need to go as hard as this one likely will.)

Won Kyung - coming next year, follows the life of Taejong’s queen so straddling the end of Goryeo start of Joseon in the 14th/15th century.

Moon in the Day - the half in my list. It’s going to air in October and follows two star-crossed reborn lovers with apparently a decent chunk of the story taking place in Silla, a kingdom that existed 1st century BCE - 10th century CE (no idea when in particular from that timeline the characters are from.)

Anyway, so so so excited!!!!

(There are also some sageuks that are coming where I don’t know what time period they are in - like Sejak - but with period kdramas until told otherwise, Joseon is always the safest bet.)

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

*in as faithful a translation as possible if translated at all, especially from a dead language you don't speak (e.g. not anne carson's sappho or a modern adaptation of the epic of gilgamesh)

*provided this is an odd way of grouping together date ranges that is partly eurocentric and partly just plain nonsensical since 12 options are the most one can add

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The Arabic name Medinet Habu (“City of Habu”) was thought to reflect the site's more ancient connection with Amenhotep, the son of Hapu, a respected sage of the 14th century BCE, later deified, whose memorial temple was immediately to the north. No trace of this association has come down from ancient times, however, as the site's formal name in Egyptian was either Djeme, “Males and Mothers”— originally with reference to the eight primeval deities, or Ogdoad, whom the ancients believed to be buried there — although the name continued to be used by the site's later Christian inhabitants.

Medinet Habu's most conspicuous standing monument is the great memorial temple of Ramesses III (reign 1198–1166 BCE). On the grounds of this complex, however, are numerous other structures, most notably the so-called small temple (built in stages, from the mid 18th Dynasty until the second century CE) and the memorial chapels of the divine votaresses of Amun (25th Dynasty and 26th).

Among other ancient buildings at the site, but less well preserved, is the memorial temple of King Horemheb (reign 1343–1315 BCE), usurped from his predecessor Ay (reign 1346–1343 BCE), which abuts Ramesses III's enclosure on its northern side. To its east are a number of tomb chapels made for high officials of the later New Kingdom.

Most abundantly on the enclosure wall of Ramesses III's temple are the remnants of later mud-brick houses — from the town that engulfed the site beginning in the 11th century BCE until the site was abandoned in the 9th century CE. Reuse of Ramesses III's temple was made especially apparent by the decorated doorways that were cut into its northern outer wall during early Christian times, when the Holy Church of Djeme occupied the building's second court.

The great temple of Ramesses III was called the Mansion of Millions of Years of King Usermare-Maiamun; ‘United with Eternity in the Estate of Amun on the West of Thebes.’ The precinct, 210m × 315m, was entered by two stone gates in the mud-brick enclosure wall, on the eastern and the western sides. The western gate — presumably the normal entrance for employees who lived outside the precinct — was destroyed when the temple was besieged in a civil war, during the reign of Ramesses XI (c. 1096 BCE). The eastern entrance, approached by a canal, terminated in a harbour, from which important visitors and statues could enter the temple.”

SOURCE: William J. Murnane, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt (2001)

#egypt#ancient egypt#egyptology#archaeology#historyedit#mine#my edit#medinet habu#20th dynasty#new kingdom#thebes#waset#luxor#ramesses iii

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

The FSYY Drinking Game

In case you actually want to read Investiture of the Gods, and need something to help you endure the monotony.

Take a sip whenever someone says it was all Fated to Happen/Heaven's Will.

Take a sip whenever King Zhou cannot control his simp behavior and goes after a woman he really shouldn't be courting.

Take a sip whenever his officials try to make him see reason with a lengthy, boring speech.

Take two sips if the official in question meets a gruesome end.

Take three sips if it's via Daji's suggestion.

Take a sip for every pre-battle speech where one side decries their opponents as unfilial/honorless traitor scum, and the other side responds with extensive justification about why their rebellion is totally righteous and not violating any anachronistic Neo-Confucian moral standards.

Take a sip for every description of cannonballs fired in fantasy 11th century BCE China.

Take a sip every time a character blames all the problems on those wicked, wicked women.

Take a sip whenever someone gets killed and is instantly resurrected via Daoist magic.

Take two sips if that "someone" is Jiang Ziya.

Take a sip whenever someone has to get through That One Pass, and is blocked by an enemy general.

Take a sip whenever someone goes against their masters' instructions, with disastrous results.

Take two sips if they suggest those results themselves, in the format of "If I do X, then let Horrible Thing Y be my rightful punishment!"

Take a sip whenever a new foe is here because of Shen Gongbao.

Take a sip for every formation built by Jie Sect Daoists, because this time it's gotta work, right?

Take a sip whenever a Jie Daoist shows up to avenge their friends/family/sectmates.

Take a sip whenever Yang Jian survives something that would've killed any other characters, because his Ninefold Mystics power is just that OP.

Take a sip every time Yang Jian acts as the Chan/Zhou faction's errand boy and goes to an immortal's abode to ask for their aid.

Take a sip every time Yang Jian's dog takes a bite out of someone.

Take a sip for every magical treasure/spell that sucks people and things in, literally.

Take a sip for every treasure/spell/ritual that rips someone's souls out of their body.

Take two sips if they try to use it on Nezha, and he's not affected by virtue of being made of plants.

Take a sip every time someone tries to destroy Xi Qi, the Zhou dynasty capital, via magical means.

Take a sip whenever someone is about to finish off a foe, only for a Western Sect guy to show up, say they were "destined for the West", and whisk them away like Pokemons.

Take a sip whenever the novel suggests that popular Buddhist deities are all just Daoist sages in trenchcoats.

Take a sip whenever a named character shows up, only to die and be deified seconds later.

Nope, don't take a sip for every soul sent into the Investiture. You'll quickly die of alcohol poisoning, and we already know there's 365 of them, which kinda defeats the whole point of a drinking game.

Do take a sip if the job they end up getting in the Celestial Bureaucracy is especially absurd or comedic——for example, King Zhou being deified as a minor star of romance.

(By the time you are done, your liver would probably look like King Zhou's Pool of Wine.)

(Please don't take this seriously, you don't get deified for drinking yourself to death IRL.)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cat and other animals

* Egypt

* period: New Kingdom (16th century BCE - 11th century BCE)

* Egyptian Museum, Turin

Turin, June 2023

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

When speaking about the Oracles of Apollo, we often just mention the most famous oracle of Delphi with its Pythia or the oracle of Phocis with the Mount Parnassus nearby. However, Apollonian cults across the Ancient Mediterranean had not one or two, but more oracles out of which some major ones are: Delphi, Didyma, Hierapolis, and more - they were scattered across Mainland Greece and Asia Minor.

The oracle of the Ancient Didyma is one of these major sites that has had just as interesting of a history of divinatory practices as any other one of Apollo’s oracles.

Oracle of Didyma, first properly mentioned in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, is a sanctuary located in the town Didim of Ancient Anatolia, Asia Minor (current Turkey), now formally known as Yenihisar. The name of the place is of unclear origin: some researchers suggested Greek origins, seeing that dydimos means “twin” and the association with Apollo and Artemis is obvious, but Artemis’ cult of Didyma had no connections nor mirroring of that of Apollo. Others suggested Zeus as the “partner” God of Apollo at the site - but we have so far found no evidence of there being a Zeus Didymos cult at any point of Ancient cultic activity. Fontenrose suggested that the name must be Carian (Anatolian language) and go along with other Anatolian place names: Sydima, Idyma, Loryma, Kibyma, and such.

The earliest archaeological finds so far discovered at the location site date the cult back to the 8th century BCE, possibly following the Ionian conquest over these Carian lands. The earliest dated pieces of pottery found in Didyma link us back to the 14th century BCE and the Mycenean civilization. Ancient writers, such as Pausanius, claim that the oracle has operated since the 11th century BCE, long before the Ionic invasion, but we are yet to find evidence to back up that claim.

As of current, the city-sanctuary is attested to the Ionian cult of Apollo and is located around 10 kilometers South from the city of Miletus.

While the structural identity of the temple is incredibly interesting and doubles the temple at Delphi in a lot, I will only mention some peculiarities that the Didyma temple of Apollo had: a temenos (a protective wall around a sacred place), a stoas (freestanding surrounding collonade), a circular altar, a naiskos (small inner altar with a pediment), a chresmographeion (office of the oracle), and a sacred well preceding the temple.

Interestingly enough, the temple of Apollo at Didyma, as many scholars agree, was likely built with the aim to create an underground adyton, or inner shrine. Archaeological research and astronomical events observed at the site show that the sanctuary, built slightly differently from other Apollonian oracles in terms of its stellar orientation, was probably meant to face the rising of the constellation of Lyra.

It is possible that the temple was unroofed in both Archaic and Hellenistic age, when the building went through major rebuilding. Interestingly enough, the site of Didyma had musical and drama contests held annually but lacked a theater or an odeion.

The oracle of Didyma, though at first one of the two most popular oracular sites in Asia Minor, has seemingly gone through a decline after the destruction of the temple by Persians in the 5th century BCE. It has been through an uprising in the Hellenistic era with a following decline as Christianity spread, rendering the temple and the oracle unused as late as 3rd century AD.

Unfortunately, the information on the divinatory practices at the site of Didyma is not as well preserved as the information at other sites, such as the oracle of Delphi. We do know that the temple had a priest or a priestess to deliver versed prophecies - the gender of the deliverer of prophecies, through, is unknown.

Generally, there are two main types of divination that have been attested as used at the Didyma temple: mantic trance and cleromancy

We do not know enough to state anything on the divinatory process involving mantic trance at the site during the Archaic age, as all evidence so far has been inconclusive. However, there are surviving inscriptions and writings that show the form of divinatory delivery as used at the site in the post-Archaic period, after the renown revival of the temple by Alexander the Great. The oracle, whether a man or a woman, delivered the prophecies likely directly in form of a dactylic hexameter. Some researches supposed that every Apollonian oracle worked this way, though we do know that some of them were specific about the gender of the oracle - not Didyma.

Perhaps the latter has something to do with the legendary hoi Branchidae, priests tending to the temple of Apollo at Didyma; said to root from Branchus, the God’s old lover.

The oracle of Delphi, a site that, according to geological investigations, likely did have a chasm under the bedrock that could indeed leak vapors into the room of the temple, is different from the oracle at Didyma as the Anatolian temple lacks same volcanic geology. It is thus unclear if the oracle of Didyma fell into mantic trance as it is at all or perhaps used different methods of entering it.

In fact, it is still unclear whether the very concept of a mantic trance was that prevailing over other divinatory types. The requests for the Pythia were, for example, so constant that other types of divinatory practices were constantly used at Delphi. As for Didyma, there is another divinatory method that researchers have so far found evidence of being used.

Astragali, the animal bone knucklebones, have been found across all divinatory centers of the Ancient world. Traditionally made out of bones of ugulates (pigs, sheep, goats, etc.) those lots had numerical significance as they were split into named groups and attested numbers each. It is unclear why specific animals only were used for making astragali, though there’s been stastical research that showed certain bones of certain animals, when shaped correctly, gives better, more equal results when thrown as dice.

As a divinatory tool, astragali possessed a degree of uncertainty to them as they could be modified to change the outcome of the draw; however, some researchers state it was believed that the seemingly random outcome of the draw ensured the diviner bears no influence on the outcome of said draw.

Astragali are sometimes believed to be secondary to oracular advice, and this assumption is based on a few factors. Seeking out oracular help included involving oneself into an expensive and time-consuming procedure that included sacrificing a whole sheep or goat, buying a honey cake for an offering, and going through an extensive consultation; that, combined with how rarely oracles of Delphi, Didyma, and other sites spoke added on to the subjective higher validity of the process, though there’s no proof one way of divination had an actual “better” effect on the results received than the other.

Ancient Anatolia has known divination by what later was called astragali from as long ago as the Copper Age (5,000 - 3,000 BCE) with prominence in the Anatolian city of Alisar, modern Turkey. Middle Bronze Age (2,100 - 1,550 BCE) and Late Bronze Age (1,550 - 1,200 BCE) dated finds of astrogali near Aphrodisias, Turkey, and Beycesultan neared the location of Didyma, pointing out the possible usage of the knucklebones at the site, too. Local Hittites have used astragali as oracular devices since the 14th century BCE, and the tradition seemed to continue on until it changed somewhere between Bronze and Iron age.

The Archaic finds in Ancient Anatolia point out that the usage of astragali has been quite consistent both in the temple to Apollo and the temple to Artemis in Ephesus alongside its use in different local sancturies. The knucklebones found were made out of wood, bones, and sometimes glass - inscribed, clear, and modified alike. Most of the astragali found at the site of Didyma were modified by lead, thus heavy, and had inscriptions on them that point out that the knucklebones bore messages to the inquirer.

One of the most fascinating parts about the history of divination at the site of Archaic Didyma is that the delivery of responses from the Deity was, apparently, direct - not a very common happening across the Greek Apollonian temples. Usually, the delivery would be done through a medium though inscriptions from Didyma use third (”the God said...) and first (”I said...”) person to describe messages given by, apparently, Apollo. Herodotus marks an event where the men of Kyme asked the oracle for advice and, after receiving a dissatisfactory reply, have continued to ask across other oracles of the region, eventually growing angry and disturbing the birds nesting in the walls of one of the temples. That, according to the historian, angered the God enough to speak to the intruders directly and request to never come back. Whether true or not, this does show that at Didyma, the belief persisted that Apollo could deliver messages personally and directly.

Another inscription found at Didyma also points out that the God spoke to the prophet directly; Delphic and Lebadeian oracles occasionally spoke spontaneous utterances directly to the oracles, too. However, the incident of a God speaking to a mortal directly is still a rarity in Ancient Greek worldview.

Sources and further reading: 🏺 🏺 🏺 🏺

#HISTORIA 📔#ancient anatolia#ancient greece#ancient history#ionian greece#cult of apollo#temple of apollo#oracle of apollo#apollo#divination

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Do you know why your father sprinkles the flax with water when it is laid out in the pit?"

“He hasn't told me. Surely it is to clean it?”

“Don't you know that in order to make it pure all that can rot in it must rot? That in order to make a durable thread one has to first destroy what otherwise might be corrupted. Of course, one must save the fibers at the right moment, and afterwards one trusts the Sun to burn away what is impure.”

“And then it becomes white?”

“Not yet; first it is broken and long threads are drawn; and these threads are watered again so that they must rot a little more. In this way everything that is corruptible in them is consumed; and of the purified flax are made those fine linen tissues.”

“But how can it become so fine after having been spoiled?”

“Nothing has been spoiled in it that was pure; but nothing can be reborn without having undergone the test of having everything corruptible destroyed.”

Isha Schwaller de Lubicz, Her-Bak: The Living Face of Ancient Egypt

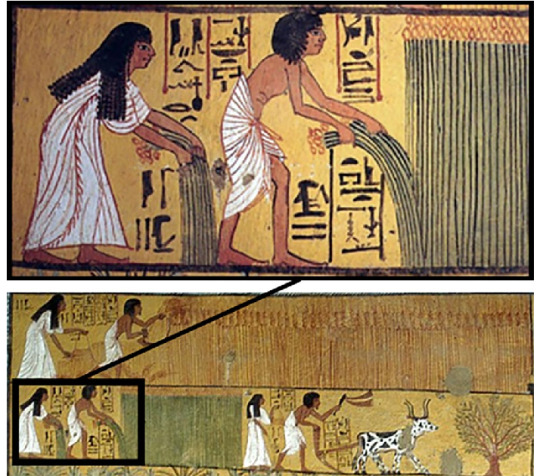

Image is a scene from the tomb of Sennedjem depicting the harvest of wheat and flax, Deir el-Medina, Egypt, Ramesside Period (13th to 11th centuries BCE)

#her-bak#kemetic#kemeticism#kemetism#spiritual growth#spiritual awakening#self transformation#death and rebirth#ancient kemet#ancient egypt#egyptian paganism#egyptian polytheism#kemetic polytheism#egyptian#egypt

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ear Pick in the Shape of an Alligator. 13th–11th century BCE. Credit line: Gift of Ernest Erickson Foundation, 1985 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45178

#aesthetic#art#abstract art#art museum#art history#The Metropolitan Museum of Art#museum#museum photography#museum aesthetic#dark academia

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

HAPPY Valentine's Day!

❤️ Photo 1: A marble statue of Amor and Psyche, the lovers from the late 2nd Century CE novel "The Golden Ass" by Lucius Apuleius (125 - 170 CE). Marble. Roman copy, around 150 CE. ©️ by Osama S.M. Amin.

❤️ Photo 2: Painted limestone statue of an unnamed man and his wife. Thebes, Egypt. 18th Dynasty, (1543–1292 BCE). ©️ by Osama S.M. Amin.

❤️ Photo 3: Detail of a painting from the limestone walls of the Tomb of the Diver. Paestum, Italy. c. 480-470 BCE. By Miguel Hermoso Cuesta.

❤️ Photo 4: Amorous couple from central India, Chandella Dynasty, 11th century CE. By Jan van der Crabben.

❤️ Photo 5: Joined Couple from Nayarit, Mexico. (100 BCE-250 CE). From James Blake Wiener.

❤️ Photo 6: The Arnolfini Wedding painting by the Netherlandish Renaissance artist Jan van Eyck (1434 CE).

❤️ Photo 7: General Horemheb & Wife. 18th Dynasty, c. 1327-1323 BCE. From the tomb of Horemheb at Saqqara, Egypt. ©️ by Osama S.M. Amin.

❤️ Photo 8: The painted terracotta Sarcophagus of the Married Couple from the Etruscan site of Cerveteri. c. 530-520 BCE. By Sailko.

❤️ Photo 9: Woman Spying on Male Lovers by an unknown artist, Qing Dynasty.

270 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Origins of Red Boy

I believe I have found the origins of Red Boy (Hong hai'er, 紅孩兒), his name, and his fire powers from Journey to the West (Xiyouji, 西遊記, 1592). I plan to write an article for my research blog, but it probably won't be until next year. Until then, I want to post my findings here for all to read.

Although the 1592 edition of Journey to the West casts Red Boy as the son of Princess Iron Fan (Tieshan gongzhu, 鐵扇公主), an early-Ming zaju play that predates the novel says his mother is the demon goddess Hārītī (Guizimu, 鬼子母).

A 1st-century BCE Gandharan statue of Hārītī.

Scene 12 of the zaju play sees the Buddha trap Red Boy under his alms bowl in order to force Hārītī to mend her evil ways and convert to Buddhism. This story comes directly from Buddhist canon. Various sources tell how the demoness ate the children of untold numbers of human women, who eventually sought out the Buddha. The Enlightened One knew that Hārītī herself was the mother of 500 (or more) demon children and also that the youngest of them, a boy named either "Pingala" or "Priyankara" (sources vary), was her favorite. One version of the story ends with the demoness converting to Buddhism in order to save her beloved child, who had been hidden under the Buddha's alms bowl. Therefore, Red Boy can confidently be traced to Pingala-Priyankara.

A sketch of the Buddha's alms bowl.

The name Red Boy has puzzled me for some time, but thanks to art sent to me by an expert on Hārītī, I was able to crack the case. Some art shows Hārītī's son wearing red clothing—i.e. a "Red Boy".

Detail from a 1440s temple mural depicting Hariti and her red-clad son.

The early-Ming zaju play doesn't associate Red Boy with fire. This appears to be a product of the 1592 edition. The novel calls his power "True Samādhi Fire" (Sanmei zhenhuo, 三昧眞火). It's so powerful that nothing short of Guanyin's holy dew can extinguish it. So where did his power come from?

A modern drawing of Red Boy's fire powers.

Journey to the West (1592) states that Guanyin gives Red Boy the religious name "Boy of Goodly Wealth" (Shancai tongzi, 善財童子) after he submits to Buddhism. This is the Chinese name of "Sudhana", a child cultivator famous for studying under 53 divine and mortal masters in the Gaṇḍavyūha Sūtra (c. 200-300).

An 11th or 12th-century print of Sudhana (left) and one of his teachers (right).

Sudhana's ninth teacher, Jayoṣmāyatana (Shengre poluomen, 勝熱婆羅門), likely influenced Red Boy's fire powers. The brahmin is said to wield a fearsome holy fire called the "Samādhi light of adamantine flame" (Jingang yan sanmei guangming, 金剛焰三昧光明). It's so powerful that it scares even the gods and demons, but it's true purpose is to incinerate the ego and enlighten the mind. Sudhana comes one step closer to enlightenment by jumping into the flames as instructed.

A Song or Ming-era Japanese painting of the fire brahmin and Sudhana.

The Gaṇḍavyūha Sūtra mentions that Jayoṣmāyatana practices extreme fire austerities on a flaming mountain. This is interesting because, despite Hārītī being Red Boy's mother in the early-Ming zaju play, Princess Iron Fan and the Flaming Mountain episode do appear later in scenes 18 to 20 of the production. Therefore, the author-compiler of Journey to the West (be it Wu Cheng'en or otherwise) could have combined the similar elements from each story, making Red Boy-Sudhana the son of Princess Iron Fan and giving him the brahmin's fire powers.

A 20th-century postcard depicting a battle between Princess Iron Fan and the Monkey King.

#Red Boy#Red Son#Journey to the West#JTTW#Princess Iron Fan#Hariti#Guizimu#fire powers#super powers#Samadhi#Lego Monkie Kid#Demon Bull King#Bull Demon King#research#Sun Wukong#Monkey King

112 notes

·

View notes