#1848 french revolution

Text

Some post June Rebellion Marius x Cosette HCs after Valjean dies

. After Valjean dies in early March 1833, Marius and Cosette moved to Marseille ( which is also Valjean's birthplace )

. Marius becomes an investigative journalist in LA Marseillaise ( a neutral news reporting company in Marseille ), while Cosette becomes an art teacher at a Catholic school

. They have 4 children together : Victoire II ( born in 1834 May ), twins Marcelin II and Michel II ( born in 1836 ), and Adelaide ( born in 1838 )

. Marius and Cosette basically juggle between their careers, raising their 4 children, all that

. They work to heal their traumas together, and they can't bear to tell their children the sheer horror details of what they been through in the June Rebellion

. I mean, their children heard some stuff about that at those points, yet still

. On the night before the 1848 French Revolution in Feb for 3 days, Victoire II told her father that she wants to join her friends to defend her school

. Marius told his oldest daughter that he is very sorry, yet she and her siblings shall be in the basement for a few days till the whole hoopla is over

. Victoire sighed and went to the basement with her siblings

. The next morning when Marius and Cosette woke up

. They are HORRIFIED TO DISCOVER THAT VICTOIRE HAS SNUCK OUT ALREADY?!?!?!

. Cue Marius and Cosette scrambling to ride on some rental horses and ask around directions

. Ofc they told the small sized staff in tow of that house to watch over Victoire II's sibs in the basement

. Eventually they managed to find Victoire II joining her friends to help defend her school

. Cue Marius and Cosette risked their lives to rush to save their oldest daughter

. Luckily, she survived

. Unluckily, Victoire II literally nearly died that day and has to be hospitalized for injuries for 2 months

. That event made the Pontmercys closer over shared shock and grief on that

. After the 1848 French Revolution, despite the celebratory cries of victory against the July Monarchy ringing all across France, there is still much work to be done to recover France

. Victoire II's parents visited Victoire II regularly in that hospital. Victoire II's sibs stayed in a health spa for 2 months due to intense PTSD from the 1848 French Revolution

. Ofc Marius and Cosette worked to help their kids and each other recover from the 1848 French Revolution

. After the 1848 French Revolution, Marius soon founded his own social newsletter called La Lumiere, and Cosette switched to be an art teacher at the Marseille Art Museum

. Because they are HAUNTED with how their oldest daughter nearly died in that event, and they are also haunted with how several of their Co workers ( and several of the students in that school Cosette worked in before ) didn't make it in the 1848 French Revolution for some time.... 🤯🤯🥺🥺🥺😭😭😭

. Also also Cosette becomes a lead illustrator for Marius' newsletter after the 1848 French Revolution

. Before that, she already at times helped with illustrations with Marius' journals during his La Marseillaise days

🤩🤩🤩🥺🥺🥺

Victoire II and Marcelin II are more like their father

While Michel II and Adelaide are more like their mother

🤯🤯🤯🥺🥺🥺

It was around after the 1848 French Revolution did those 4 eventually knew what their parents really been through in the June Rebellion

Their parents profusely apologized to them for not telling them sooner due to ' fear of breaking their hearts '

And those 4 understand and forgive them

🤯🤯🥺🥺🥺

A thing is

Marius and Cosette will still be Republican leaning in the 1840s French Revolution

Yet their No. 1 priority especially then is to ensure the securities of their household and their children, especially from the machinations of Royalist thugs

🤯🤯🤯🤯🤯🤯

Plus in my Les Mis fics Cosette soon came to use her art classes as a form of art therapy for her students who been through a lot in the June Rebellion and later the 1840s French Revolution

🤯🤯🤯🥺🥺🥺

She also uses her visual arts skills as a form of helping Marius and their children as a form of art therapy especially after all they been through and such

🤯🤯🤯🥺🥺🥺

During her post Valjean's death era, Whenever she isn't art teaching, Cosette basically juggles with raising her children, managing that household, getting involved with community related matters often, and sometimes likes to hang out at parks with Marius, their children and their friends

She also sometimes likes to visit art galleries, similarly as she has sometimes done during the June Rebellion era ( sometimes with Valjean, her post Convent Era friends and later on Marius )

In the Les Mis book, Cosette came to have a penchant for visual arts

It certainly becomes therapeutic to her especially after all she been through

I'd love to develop that aspect more in my Les Mis fics

🤩🤩🤩🥺🥺🥺🥺

Like post Convent School Era Cosette defo becomes a quirky, gentle, dreamy and brave soft goth girl who carries her art supplies in her bags wherever she went, often wearing flowers on her hats and coiffures, and basically shows Marius and her loved ones a different outlook of life

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I vaguely remembered that I’d woken up last night at 2am and scrambled desperately for my phone to Wikipedia-search something I just HAD to know, then immediately fell back to sleep.

But for the life of me, I could not remember what I had searched. Curious, I opened my phone’s browser to see this:

You know that feeling: it’s 2am and you really really need to immediately read the biography of Maximilien Robespierre. We’ve all been there.

#i do finally remember why but it’s boring: I wanted to know where he went to law school for some reason#it was at the Sorbonne ofc#i woke up an hour later from a dream about the French Revolution of 1848 so I should have guessed the nature of the Wikipedia search#very funny#stress dream unlocked: various french revolutions#shut up e#frev

502 notes

·

View notes

Text

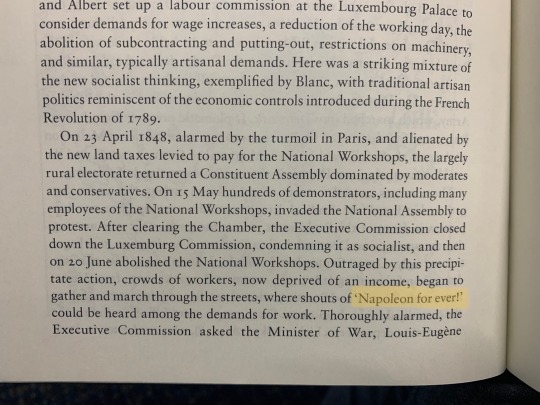

Napoleon as a rallying cry during the revolutions in France during the 19th century

July Revolution (French Revolution of 1830):

French Revolution of 1848:

Source: The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815-1914, Richard J. Evans

#The Pursuit of Power#Richard J. Evans#Evans#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Talleyrand#Charles X#Thiers#Marmont#Lafitte#Jacques Lafitte#Louis-Philippe#Lafayette#Revolution#french revolution#July Revolution#1848 revolutions#Revolution of 1848#1848#napoleonic era#Blanc#first french empire#napoleonic#history#french history#my pics#book#book quotes#revolution of 1830#France

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ideal Republic:

I don't know about you, but in France, there's increasingly justified complaints that the representative system is completely out of touch with its people. We need more democracy, better representation. A profound system change to address our problems.

I would like a Republic with a president refusing to live in the Presidential Palace but rather in his apartment like the majority of French people, as President Mujica did. He would be less disconnected from the reality of the people because he would live among the majority of them (similarly to how French revolutionaries worked at the Tuileries but didn't live there). The case of President Mujica should no longer be an exception but the rule.

The presidential palace should serve only as a workplace and to receive foreign dignitaries.

All government members, including deputies, should now live with a salary decrease similar to that of the majority of French people. We can't ask the people to make efforts if we don't practice them ourselves.

I would like a model based on the First Republic with a much more controlled executive, divided in the General Assembly as the Republicans proclaimed. I would like a new constitution as close as possible to that of 1793. Like the First Republic, I would like citizens who are not part of the government or the General Assembly to take the stand to voice their demands, difficulties, criticisms, absolutely everything.

Government members who are under investigation by justice should no longer receive any special treatment. We citizens don't benefit from it, so why should they?

After all, it is the government that should serve the people, not the other way around.

Referendums should be well conducted, well respected, ensuring that the fundamental rights acquired after many struggles remain respected as inviolable rights (abolition of the death penalty, right to abortion, marriage for all, etc.).

Social progress should continue even if it might displease some…

Only this Republic could be the one that meets our needs… But I don't think I'll see it one day… Anyway, I've always thought that the rights we've acquired have only come after years of struggle, that revolutions happen in different periods. The most recent example that comes to mind is the one where we almost had a revolution in May 1968. There will surely be another day, we will have a real program for the people again, then it will be fought and it will be a cycle… But every concession we wrestle is a victory, and that's not a reason to give up (for example: there were real social revolutions in 1792, in 1830, in 1848, and in 1870, for example, even if in the end there were always regressions or the fact that these revolutions were buried or failed, they managed to secure very significant concessions and always to rise again, without all these revolutionaries we might even have been at risk of losing all our rights, we wouldn't have had them at all).

#France#revolution#french revolution#the communards#1848#1830#Republic#Third Republic#Fifth Republic

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Uses of History, 14 – France, Revolution #4, 1870-1, Part 1

The Uses of History, 14 – France, Revolution #4, 1870-1, Part 1

(Photo credit – Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, 1849 – Wikimedia Commons)

Until 1871, no one in continental Europe or anywhere in the world with knowledgeable connections to Europe, as in North America or areas under European domination in other continents, questioned that the greatest European power after the United Kingdom was France. Britain, as unchallenged mistress of the world’s oceans and the…

View On WordPress

#Belgian Revolution#Congress of Vienna#Emperor Napoleon III#French Revolution 1870-71#Holy Alliance#Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte#Metternich#Polish Revolt 1831#Revolutions of 1848

1 note

·

View note

Text

Les Mis French History Timeline: all the context you need to know to understand Les Mis

Here is a simple timeline of French history as it relates to events in Les Miserables, and to the context of Les Mis's publication!

A post like this would’ve really helped me four years ago, when I knew very little about 1830s France or the goals of Les Amis, so I’m making it now that I have the information to share! ^_^

This post will be split into 4 sections: a quick overview of important terms, the history before the novel that’s important to the character's backstories, the history during the novel, and then the history relevant to the 1848-onward circumstances of Hugo’s life and the novel’s publication.

Part 1: Overview

The novel takes place in the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo, during a period called the Restoration.

The ancient monarchy was overthrown during the French Revolution. After a series of political struggles the revolutionary government was eventually replaced by an empire under Napoleon. Then Napoleon was defeated and sent into exile— but then he briefly came back and seized power for one hundred days—! and then he was defeated yet again for good at the battle of Waterloo in 1815.

After all that political turmoil, kings have been "restored" to the throne of France. The novel begins right as this Restoration begins.

The major political parties important to generally understanding Les Mis (Wildly Oversimplified) are Republicans, Liberals, Bonapartists, and Royalists. It’s worth noting that all these ‘party terms’ changed in meaning/goals over time depending on which type of government was in power. In general though, and just for the sake of reading Les Mis:

Republicans want a Republic, where people elect their leaders democratically— they’re the very left wing progressive ones, and are heavily outcast/censored/policed. Les Amis are Republicans.

Liberals are (iirc) actually the most powerful “leftist” group at the time; they generally want limits on monarchical power but don’t go as far as Republicans.

Bonapartists are followers of Napoleon Bonaparte I, who led the Empire. Many viewed the Emperor as more favorable or progressive to them than a king would be. Georges Pontmercy is a Bonapartist, as is Pere Fauchelevent.

Royalists believe in the divine right of Kings; they’re conservative. Someone who is extremely royalist to the point of wanting basically no limits on the king’s power at all are called “Ultraroyalists” or “ultra.” Marius’s conservative grandfather Gillenromand is an ultra royalist.

Hugo is also very concerned with criticizing the "Great Man of History," the view that history is pushed forward by the actions of a handful of special great men like kings and emperors. Les Mis aims to focus on the common masses of people who push history forward instead.

Part 2: Timeline of History involved in characters’ Backstories

1789– the March on the bastille/ the beginning of the original French Revolution. A young Myriel, who is then a shallow married aristocrat, flees the country. His family is badly hurt by the Revolution. His wife dies in exile.

1793– Louis XVI is found guilty of committing treason and sentenced to death. The Conventionist G—, the old revolutionary who Myriel talks to, votes against the death of the king.

1795: the Directory rules France. Throughout much of the revolution, including this period, the country is undergoing “dechristianization” policies. Fantine is born at this time. Because the church is not in power as a result of dechristianization, Fantine is unbaptized and has no record of a legal given name.

1795: The Revolutionary government becomes more conservative. Jean Valjean is arrested.

1804: Napoleon officially crowns himself Emperor of France. the Revolution’s dream of a Republic is dead for a bit. At this time, Myriel returns from his exile and settles down in the provinces of France to work as a humble priest. Then he visits Paris and makes a snarky comment to Napoleon, and Napoleon finds him so witty that he appoints him Bishop.

Part 3: the novel actually begins

1815: Napoleon is defeated at the Battle of Waterloo by the allied nations of Britain and Prussia. Read Hugo’s take on that in the Waterloo Digression! He gets a lot of facts wrong, but that’s Hugo for you.

Marius’s father, Baron Pontmercy, nearly dies on the battlefield. Thenardier steals his belongings.

After Napoleon is defeated, a king is restored to the throne— Louis XVIII, of the House of Bourbon, the ancient royal house that ruled France before the Revolution. In order to ensure that Louis XVIII stays on the throne, the nations of Britian, Prussia, and Russia, send soldiers occupy France. So France is, during the early events of the novel, being occupied by foreign soldiers. This is part of why there are so many references to soldiers on the streets and garrisons and barracks throughout the early portions of the novel. The occupation officially ended in 1818.

1815 (a few months later): Jean Valjean is released from prison and walks down the road to Digne, the very same road Napoleon charged down during his last attempt to seize power. Many of the inns he passes by are run by people advertising their connections to Napoleon. Symbolically Valjean is the poor man returning from exile into France, just as Napoleon was the Great Man briefly returning from exile during the 100 days, or King Louis XVIII is the Great King returning from exile to a restored throne.

1817: The Year 1817, which Hugo has a whole chapter-digression about. Louis XVIII of the House of Bourbon is on the throne. Fantine, “the nameless child of the Directory,” is abandoned by Tholomyes.

1821: Napoleon dies in exile.

1825: King Louis XVIII dies. Charles X takes the throne. While Louis XVIII was willing to compromise, Charles X is a far more conservative ultra-royalist. He attempts to bring back the Pre-Revolution style of monarchy.

Underground resistance groups, including Republican groups like Les Amis, plot against him.

1827-1828: Georges Pontmercy, bonapartist veteran of Waterloo, dies. Marius, who has been growing up with his abusive Ultra-royalist grandfather and mindlessly repeating his ultra-royalist politics, learns how much his father loved him. He becomes a democratic Bonapartist.

Marius is a little bit late to everything though. He shouts “long live the Emperor!” Even though Napoleon died in 1821 and insults his grandfather by telling him “down with that hog Louis XVIII” even though Louis XVIII has been dead since 1825. He’s a little confused but he’s got the spirit.

Marius leaves his grandfather to live on his own.

1830: “The July Revolution,” also known as the “Three Glorious Days” or “the Second French Revolution.” Rebels built barricades and successfully forced Charles X out of power.

Unfortunately, TL;DR moderate politicians prevented the creation of a Republic and instead installed another more politically progressive king — Louis-Philippe, of the house of Orleans.

Louis-Philippe was a relative of the royal family, had lived in poverty for a time, and described himself as “the citizen-king.” Hugo’s take on him is that he was a good man, but being a king is inherently evil; monarchy is a bad system even if a “good” dictator is on the throne.

The shadow of 1830 is important to Les Mis, and there’s even a whole digression about it in “A Few Pages of History,” a digression most people adapting the novel have clearly skipped. Les Amis would’ve probably been involved in it....though interestingly, only Gavroche and maybe Enjolras are explicitly confirmed to have been there, Gavroche telling Enjolras he participated “when we had that dispute with Charles X.”

Sadly we're following Marius (not Les Amis) in 1830. Hugo mentions that Marius is always too busy thinking to actually participate in political movements. He notes that Marius was pleased by 1830 because he thinks it is a sign of progress, but that he was too dreamy to be involved in it.

1831: in “A Few Pages of History” Hugo describes the various ways Republican groups were plotting what what would later become the June Rebellion– the way resistance groups had underground meetings, spread propaganda with pamphlets, smuggled in gunpowder, etc.

Spring of 1832: there is a massive pandemic of cholera in Paris that exacerbates existing tensions. Marius is described as too distracted by love to notice all the people dying of cholera.

June 1st, 1832: General Lamarque, a member of parliament often critical of the monarchy, dies of cholera.

June 5th and 6th, 1832: the June Rebellion of 1832:

Republicans, students, and workers attempt to overthrow the monarchy, and finally get a democratic Republic For Real This Time. The rebellion is violently crushed by the National Guard.

Enjolras was partially inspired by Charles Jeanne, who led the barricades at Saint-Merry.

Part 4: the context of Les Mis’s publication

February 1848: a successful revolution finally overthrows King Louis Philippe. A younger Victor Hugo, who was appointed a peer of France by Louis-Philippe, is then elected as a representative of Paris in the provisional revolutionary government.

June 1848: This is a lot, and it’s a thing even Hugo’s biographers often gloss over, because it’s a horrific moral failure/complexity of Hugo’s that is completely at odds with the sort of politics he later became known for. The short summary is that in June 1848 there was a working-class rebellion against new unjust labor laws/forced conscription, and Victor Hugo was on the “wrong side of the barricades” working with the government to violently suppress the rebels. To quote from this source:

Much to the disappointment of his supporters, in [Victor Hugo’s] first speech in the national assembly he went after the ateliers or national workshops, which had been a major demand of the workers. Two days later the workshops were closed, workers under twenty-five were conscripted and the rest sent to the countryside. It was a “political purge” and a declaration of war on the Parisian working class that set into motion the June Days, or the second revolution of 1848—an uprising lauded by Marx as one of the first workers’ revolutions. As the barricades went up in Paris, Hugo was tragically on the wrong side. On June 24 the national assembly declared a state of siege with Hugo’s support.

Hugo would then sink to a new political low. He was chosen as one of sixty representatives “to go and inform the insurgents that a state of siege existed and that Cavaignac [the officer who had led the suppression of the June revolt] was in control.” With an express mission “to stop the spilling of blood,” Hugo took up arms against the workers of Paris. Thus, Hugo, voice of the voiceless and hero of workers, helped to violently suppress a rebellion led by people whom he in many ways supported—and many of whom supported him. With twisted logic and an even more twisted conscience, Hugo fought and risked his life to crush the June insurrection.

There is an otherwise baffling chapter in Les Mis titled "The Charybdis of the Faubourg Saint Antoine and the Scylla of the Fauborg Du Temple," where Hugo goes on a digression about June of 1848. Hugo contrasts June of 1848 with other rebellions, and insists that the June 1848 Rebellion was Wrong and Different. It is a strangely anti-rebellion classist chapter that feels discordant with the rest of the book. This is because it is Hugo's effort to (indirectly) address criticisms people had of his own involvement in June 1848, and to justify why he believed crushing that rebellion with so much force was necessary. The chapter is often misused to say that Hugo was "anti-violent-rebellion all the time" (which he wasn't) or that "rebellion is bad” is the message of Les Mis (which it isn't) ........but in reality the chapter is about Hugo attempting to justify his own past actions to the reader and to himself, actions which many people on his side of the political spectrum considered a horrible betrayal. He couldn't really have written a novel about the politics of barricades without addressing his actions in June 1848, and he addressed them by attempting to justify them, and he attempted to justify them with a lot of deeply questionable rhetoric.

1848 is a lot, and I don't fully understand all the context yet-- but that general context is necessary to understand why the chapter is even in the novel.

Late 1848/1849:

Quoting from the earlier source again:

In the wake of the revolution, Hugo tried to make sense of the events of 1848. He tried to straddle the growing polarization between, on the one hand, “the party of order,” which coalesced around Napoleon’s nephew Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, who in December 1848 had been elected France’s president under a new constitution, and the “party of movement” (or radical Left) that, in the aftermath of 1848, had made considerable advances. In this climate, as Hugo increasingly spoke out, and faced opposition and repression himself, he was radicalized and turned to the Left for support against the tyranny and “barbarism” he saw in the government of Louis Napoleon.

The “point of no return” came in 1849. Hugo became one of the loudest and most prominent voices of opposition to Louis Napoleon. In his final and most famous insult to Napoleon, he asked: “Just because we had Napoleon le Grand [Napoleon the Great], do we have to have Napoleon le petit [Napoleon the small]?” Immune from punishment because of his role in the government, Bonaparte retaliated by shutting down Hugo’s newspaper and arresting both his sons.

Thenardier is likely meant to be Hugo’s caricature of Louis-Napoleon/Napoleon III. He is “Napoleon the small,” an opportunistic scumbag leeching off the legacy of Waterloo and Napoleon to give himself some respectability. He is a metaphorical ‘graverobber of Waterloo’ who has all of Napoleon’s dictatorial pettiness without any of his redeeming qualities.

It’s also worth noting that Marius is Victor “Marie” Hugo’s self-insert. Hugo’s politics changed wildly over time. Like Marius he was a royalist when was young. And like Marius, he looked up to Napoleon and to Napoleon III, before his views of them were shattered. This is reflected in the way Marius had complicated feelings of loyalty to his father (who’s very connected to the original Napoleon I) and to Thenardier (who’s arguably an analogue for Napoleon IiI.)

1851:

On December 2, 1851, Louis Napoleon launched his coup, suspending the republic’s constitution he had sworn to uphold. The National Assembly was occupied by troops. Hugo responded by trying to rally people to the barricades to defend Paris against Napoleon’s seizure of power. Protesters were met with brutal repression.

Under increasing threat to his own life, with both of his sons in jail and his death falsely announced, Hugo finally left Paris.

He ultimately ended up on the island of Guernsey where he spent much of the next eighteen years and where he would write the bulk of Les Misérables. It was from here that his most radical and political work was smuggled into France.

Hugo arguably did his most important political work after being exiled. In Guernsey, he aided with resistance against the regime of Napoleon III. Hugo’s popularity with the masses also meant that his exile was massive news, and a thing all readers of Les Miserables would’ve been deeply familiar with.

This is why there are so many bits of Les Mis where the narrator nostalgically reflects on how much they wish they were in Paris again —these parts are very political; readers would’ve picked up that this was Victor Hugo reflecting on he cruelty of his own exile.

1862-1863: Les Mis is published. It is a barely-veiled call to action against the government of Napoleon III, written about the June Rebellion instead of the current regime partially in order to dodge the censorship laws at the time.

Conservatives despise the book and call it the death of civilization and a dangerous rebellious evil godless text that encourages them to feel bad for the stupid evil criminal rebel poors and etc etc etc– (see @psalm22-6 ‘s excellent translations of the ancient conservative reviews)-- but the novel sells very well. Expressing approval or disapproval of the book is considered inherently political, but fortunately it remains unbanned.

…And that’s it! An ocean of basic historical context about Les Mis!

If anyone has any corrections or additions they would like to make, feel free to add them! I have researched to the best of my ability, but I don’t pretend to be perfect.

I also recommend listening to the Siecle podcast, which covers the events of the Bourbon Restoration starting at the Battle of Waterloo, if you're interested in learning more about the period!

#les mis#someone in a discord server asked about this a while back#so i put it together!#it’s basically what I told them in the discord server but as a tumblr post#and with some extra stuff I forgot to say#but yeAH maybe if more historical information gets spread#we’ll get more canon era fanfics >:3333#which are always fun

439 notes

·

View notes

Text

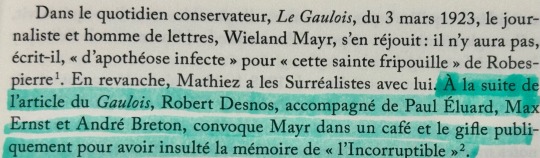

When you get publicly slapped by 4 surrealist poets because you insulted a guy's historical crush

(translation and context under the cut)

Gallantly Defending Robespierre’s Honour

In the conservative daily paper, Le Gaulois, on March 3, 1923, the journalist and man of letters, Wieland Mayr, expressed his pleasure: there would not be, he wrote, a "vile apotheosis" for "that holy scoundrel" Robespierre. On the other hand, Mathiez had the Surrealists with him. Following the article in Le Gaulois, Robert Desnos (1), accompanied by Paul Éluard (2), Max Ernst (3), and André Breton (4), summoned Mayr in a café and publicly slapped him for insulting the memory of "the Incorruptible."

Why did Mayr get Slapped?

In short: studying history in the 1920s was a messy business, especially when it came to the French Revolution….

To explain why Mayr ended up getting slapped, please allow me to briefly dive into the French Revolution's historiography during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Keep in mind, that this is a grossly oversimplified version.

Before 1848, it was pretty standard for French republicans to proudly see themselves as inheritors of Robespierre’s legacy. (If you’ve ever wondered why in Les Misérables, Enjolras’ character is very much channeling Robespierre and Saint-Just, here’s your answer!) However, things start to change with the Second Republic.

In 1847, Jules Michelet brought back the negative portrayal of Robespierre as a tyrannical "priest" and leader of a new cult. This narrative helped fuel an increasing dislike for Robespierre, with radicals like Auguste Blanqui arguing that the real revolutionaries were the atheistic Hébertists, not the Robespierrists.

Jump to the Third Republic, and the negative sentiment towards Robespierre was only getting stronger, driven by voices like Hippolyte Taine, who painted Robespierre as a mediocre figure, overwhelmed by his role. This trend was politically motivated, aiming to reshape the Revolution's legacy to align with the Third Republic's secular values. Obviously, Robespierre, the "fanatic pontiff" of the Supreme Being, didn’t quite fit this revised narrative and was made out to be the villain. Alphonse Aulard (a historian willing to stretch the truth to make his point) continued pushing Danton as the face of secular republicanism. Albert Mathiez, one of Aulard’s students, was not having any of it and strongly disagreed with his mentor’s approach.

The general disdain for Robespierre began to shift after World War I. One reason was that people could better appreciate the actions of the Revolutionary Government after experiencing the repression during the war themselves. Albert Mathiez and his colleagues were actively working to change Robespierre's tarnished image. With tensions high, it's no wonder Mayr ended up being publicly slapped by a bunch of poets who were defending the Incorruptible's honour!

Notes

Robert Desnos (1900-1945) was a French poet deeply associated with the Surrealist movement, known for his revolutionary contributions to both poetry and resistance during World War II.

Paul Éluard (1895-1952) was a French poet and one of the founding members of the Surrealist movement, celebrated for his lyrical and passionate writings on love and liberty.

Max Ernst (1891-1976) was a German painter, sculptor, graphic artist, and poet, a pioneering figure in the Dada and Surrealist movements known for his inventive use of collage and exploration of the unconscious.

André Breton (1896-1966) was a French writer, poet, and anti-fascist, best known as the principal founder and leading theorist of Surrealism, promoting the liberation of the human mind.

Source: The text in the picture comes from Robespierre and the Social Republic by Albert Mathiez

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey i’ve got an ap euro project so for data, which rébellion in france do you guys think les misérables took place during?

if you don’t know just guess based on the dates

(for reference the french revolution began in 1789)

pls let me know in the tags why you think it’s that time

321 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Revolts and revolutions in Italy under the Restoration

“Atlante storico”, Garzanti, 1966

by cartesdhistoire

The Congress of Vienna divided Italy into ten largely reactionary states, against which the secret society of Charbonnage, originating in the Kingdom of Naples in 1807, opposed itself. The "Carbonari," mainly from the middle classes, whose growth had been favored by French domination, claimed inspiration from the constitution of Cádiz promulgated by the Spanish parliament with Napoleon's agreement in 1812.

Revolutionary movements erupted first in Naples in the summer of 1820, followed by Palermo, which became the scene of a genuine civil war. The insurrection spread to Piedmont from March 1821; the insurgents were defeated in Novara on April 8, with Austrian assistance, leading to ruthless repression until October. Order on the peninsula was only fully restored in early 1822 by the Austrian army. Severe anti-liberal repression was felt in Modena, the Papal State, and Milan. At least 3,000 patriots went into exile between 1821 and 1823.

Echoing the Parisian revolution of 1830, which had a profound impact in Italy, an uprising erupted in early 1831 in Modena, Parma, and Bologna. On March 4, the Austrian army entered the Duchy of Modena, and on the 29th, the last remnants of the insurgent army capitulated. Fierce repression followed.

Patriots were divided into two models: revolutionary and democratic or liberal and moderate. The latter, itself subdivided into two currents, one advocating unification under the pope's auspices and the other under the leadership of the House of Savoy. The revolutionary model, predominant until 1848, found its embodiment in Giuseppe Mazzini, who envisioned a popular insurrection to overcome resistance from princes and local particularisms, leading to a republic. Mazzini's activism played a significant role in shaping the Italian people's national consciousness, but the utopian nature of the insurrectional path ultimately led to a deadlock.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

While the barricade is still holding on, Hugo decides that this is his last chance to write about other barricades which he ordered to be taken by siege in June 1848. To make sense of what is going on, I read a chapter about Hugo in Jonathan Beecher’s Writers and Revolution: Intellectuals and the French Revolution of 1848 (2021). “Victor Hugo never forgot what he saw and did between June 22–26. Unlike our other writers, he participated in the fighting, and he did so on the side of the government.” Sigh.

This is where his lengthy explanations about the differences between uprisings and insurrections from 4.10.2 become relevant. He genuinely believed that everything that was going on in February 1848, before the abdication of Louise Philippe was revolution (insurrection), and what followed in June was uprising against the Republic. It was “a revolt of the people against itself.”

The problem was: people had legitimate causes to rebel. “Once settled in the Assembly, Hugo was immediately confronted by the question of the National Workshops. Like many on both the right and the left, he believed the Workshops were a disaster. They produced nothing and were “an enormous waste of resources”… he urged that they be closed… He apparently believed that by voting to dissolve the National Workshops, he was not voting to shelve the question of unemployment. He was wrong.” Moreover, when workers erected the barricades and the confrontation began, “Hugo seems to have convinced himself that the best way to limit bloodshed was to defeat the insurrection rapidly. For the next three days he became a tiger, “haranguing insurgents, storming barricades, taking prisoners, and somehow remaining alive.”

According to an account from a member of the National Guard, Hugo was acting suicidally: “This man... was M. Victor Hugo, a representative for Paris. He was unarmed and nonetheless he led us; and while we took cover behind houses, he alone kept to the middle of the street. Twice I tugged at his sleeve, telling him: “You’ll get yourself killed!” “That is why I am here.”” But this was because he believed that he was acting under divine protection.

During these days, Hugo was not able to contact his wife and his mistress. He heard rumours that his house was burnt down, but finally found out that it was not true: “When he finally got back to the Place des Vôsges, he found fourteen bullet holes around carriage entrance, but everything in the house was intact: rugs, furniture, silverware, wall hangings, ancient swords and muskets, and above all his manuscripts. A leader of the insurgents, a school teacher and a reader of Hugo, had even led tours of the house for other insurgents.” The last detail is heartbreaking.

In this chapter, Hugo conveys his point of view on the events of June 1848, infusing them with symbolic images of two barricades: both quite eerie and ominous. He is exploiting his talent of horror writer again: “The Saint-Antoine barricade was the tumult of thunders; the barricade of the Temple was silence. The difference between these two redoubts was the difference between the formidable and the sinister. One seemed a maw; the other a mask.”

The sad thing is that after this chapter with its context in Hugo’s biography, it is hard to read his depiction of other barricades from other time without thinking of him as a hypocrite. This is Hugo — an embodiment of controversy.

Siege of the barricade during the June days of 1848:

#les mis letters#lm 5.1.1#les miserables#hugo's involvement in the june days of 1848#historical context

76 notes

·

View notes

Note

one person i know keeps dismissing revolutions because the french revolution eventually led to napoleon which like is obviously wrong but like i physically cannot articulate why

lenin discusses this (and similar) situations in state & revolution. basically, the french revolution (and the subsequent revolution of 1848) was a revolution in which the bourgeoisie and proletariat fought together against the feudal aristocracy. because, inevitably, the bourgeoisie betrayed the proletariat after they'd secured victory, the result of that revolution was not the abolition of the french feudal state and the creation of a new one but simply the transferral of that state into the hands of the french bourgeoisie, who promptly used it to crush the proletariat.

In France, Engels observed, the workers emerged with arms from every revolution: "therefore the disarming of the workers was the first commandment for the bourgeois, who were at the helm of the state. Hence, after every revolution won by the workers, a new struggle, ending with the defeat of the workers.

— Friedrich Engels, quoted by V.I. Lenin, The State & Revolution

a socialist revolution obvsies doesn't take this form! instead of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat both struggling against the feudal aristocracy, only for their fundamental class antagonisms to result in inevitable suppression of one by the other, a socialist revolution consists of the proletariat struggling against the bourgeoisie. the way to avoid the mistake of the french revolution is, as Engels and Lenin are v. clear, to prevent the disarming of the workers--that is, to ensure that the armed working class maintains itself into peacetime as a proletarian state.

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dobry wieczór. Since it’s International Women’s Day (albeit not strictly), tonight I would like to draw my followers’ attention to the female pianists and composers who were my contemporaries… Apologies for the lengthiness, evidently there is a lot to be covered.

Clara Schumann 1819-1896

youtube

A child prodigy, Clara was taught piano by her father and by thirteen he was taking her on concert tours.

She met Robert Schumann as a child when he came to Leipzig to study law at the university. He took piano lessons from Clara’s father, Friedrich Wieck. When she was 18, he proposed to her. They married in 1840.

The virtuoso went on tours with her husband and earn money by performing and teaching. She was also a gifted composer, however most of her time was spent looking after her family, editing Robert’s music and playing. Clara’s compositions include more than 20 piano works, a piano concerto, some chamber music and several songs.

Fanny Mendelssohn 1805–1847

youtube

Composer and pianist, Fanny grew up in Berlin, sharing the same musical education as her brother Felix, with whom she had a close relationship.

Her compositions include a piano trio, a piano quartet, an orchestral overture, four cantatas, more than 125 pieces for the piano and over 250 lieder, most of which were unpublished in her lifetime. Although lauded for her piano technique, she rarely gave public performances outside her family circle.

Owing to her family's reservations and to social conventions of the time about the roles of women, six of her songs were published under her brother's name in his Opus 8 and 9 collections.

Marie Moke 1811-1874

Marie Moke gave her first concert at the age of eight and by the age of fifteen, she was already known in Belgium, Austria, Germany and Russia as an accomplished virtuoso.

She married pianist and piano manufacturer, Camille Pleyel, but they later separated on account of her promiscuity. Heinrich Heine considered her among the greatest pianists “Thalberg is a king, Liszt a prophet, Chopin a poet, Herz an advocate, Kalkbrenner a minstrel, Mme Pleyel a sibyl, and Döhler a pianist.”

Later on, she created the piano school at the Royal Conservatory in Brussels where she taught from 1848 to 1872.

Louise Farrenc 1804-1875

youtube

A French composer, virtuoso pianist and teacher, she started playing young and had piano lessons with famous teachers such as Moscheles and Hummel. She studied composition privately with Anton Reicha at the Paris Conservatoire, unable to go to composition classes as a woman. By the 1820s she was touring France, giving concerts.

In 1842 she was made Professor of Piano at the Paris Conservatoire where she stayed for 30 years. For a decade she was paid less than the male teachers. Only after the triumphant premiere of her nonet did she demand and receive equal pay. She wrote a wide variety of piano music, but her chamber pieces are considered to be her best work.

Pauline Viardot 1821-1910

From a musical family (including her older sister, Maria Malibran) Pauline was trained by her father on the piano and in singing.

In her youth she took piano lessons with Franz Liszt and counterpoint and harmony classes with Anton Reicha. However, despite wanting to become a concert pianist, she was directed towards singing by her mother.

Pauline began composing when she was young, but it was never her intention to become a composer. Written mainly as private pieces for her students, her works were still of professional quality and Franz Liszt declared that, with Pauline Viardot, the world had finally found a woman composer of genius. Compositions include her chamber operas Le dernier sorcier and Cendrillon.

Arabella Goddard 1836–1922

Born in France to English parents, at age six Arabella was sent to Paris to study with Friedrich Kalkbrenner. Aged seven she played for myself and George much to our pleasure.

During the 1848 Revolution her family had to return to England; there, Arabella had further lessons with Lucy Anderson and Sigismond Thalberg. She was known for her ability to play recitals from memory.

Arabella was appointed a teacher at the Royal College of Music in 1883. This was the RCM’s first year of operation and Arabella was its first female professor. She composed a small number of piano pieces, including a suite of six waltzes.

Marcelina Czartoryska 1817-1894

Born into the aristocratic Polish family, the Radziwiłłs, Marcelina was taught piano by Carl Czerny in Vienna and by myself in Paris. She gave concerts across Europe, with Franz Liszt, Pauline Viardot and Henri Vieuxtemps.

From 1870 she lived in Kraków, where she gave mainly private concerts and, thanks to her artistic connections, contributed to founding Kraków’s Academy of Music in 1888.

Maria Kalergis 1822-1874

Raised in Saint Petersburg in the home of her paternal uncle, the Tsar's minister of foreign affairs, Maria received a thorough education where she evinced an early musical talent.

She was a student of mine and held salons in Paris whose guests included Liszt, Richard Wagner, de Musset, Gautier and Heine. Later, she became a hostess and a patron of the arts in Warsaw.

She was a co-founder of the Warsaw Musical Institute, now the Warsaw Conservatory and established the Warsaw Musical Society, now the Warsaw Philharmonic. Between 1857 and 1871 she made frequent appearances as a pianist.

On her death, Franz Liszt wrote his Elegy on Marie Kalergi.

#clara schumann#fanny mendelssohn#classical composers#romantic era#classical music#international women's day

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

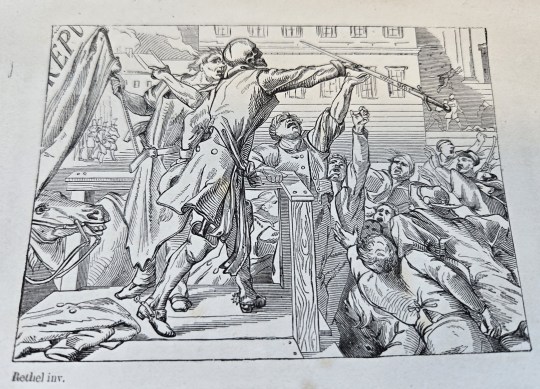

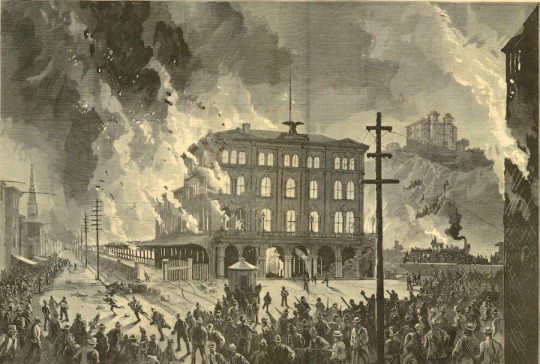

An image of the Third French Revolution in 1848. With an economic crisis, workers unhappy, and election reformers agitating for Universal Male Suffrage, it all came to a head when a meeting of the so-called Campagne Des Banquets, held to evade the prohibition on public assemblies, was prohibited. Workers and students took to the streets, set up barricades. They were met with police violence and the National Guard, and the army being called out. The National Guard sided with the revolutionaries and overthrew the monarchy.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Victor Hugo’s speech in support of Napoleon, and his support to lift the ban on the Bonaparte family

(Left: Victor Hugo, Right: Elderly Jérôme Bonaparte)

Excerpt from Jonathan Beecher, Writers and Revolution: Intellectuals and the French Revolution of 1848

—————-

Hugo was fascinated by the Praslin affair and wrote about it at length in his journals. But he was more deeply engaged by another issue brought to the Chamber of Peers in June, 1847 – the petition of Napoleon’s only surviving brother, Jérôme Bonaparte, who sought the repeal of the law exiling members of the Bonaparte family. “I declare without hesitation,” Hugo told the peers. “I am on the side of exiles and proscrits.”

Не obviously could not know that he himself was to spend almost two decades in exile. But one exile who mattered to Hugo in 1847 was the first Napoleon. In his speech to the Chamber of Peers Hugo contrasted the pettiness and corruption of the July Monarchy with the grandeur of Napoleon’s Empire:

As for me, in witnessing the collapse of conscience, the reign of money, the spread of corruption, the taking of the highest places by people with the lowest passions, (Prolonged reaction) in witnessing the woes of the present time, I dream of the great deeds of the past, and I am now and then tempted to say to the Chamber, to the press, to all of France: “Wait, let us talk a little of the Emperor. That will do us good!” (Intense and profound agreement).

After this speech, the elderly Jérôme Bonaparte personally thanked Hugo; and his daughter, the Princess Mathilde, invited him to dinner. Hugo was now regarded in some quarters as a Bonapartist.

—————-

[Italics in original]

“La Famille Bonaparte,” OC Politique, Laffont, 138-139.

#victor Hugo#Jerome Bonaparte#jerome#Napoleon’s brothers#Napoleon’s family#napoleon#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#napoleon bonaparte#french empire#19th century#france#history#bonapartism#bonapartist#1848 revolutions#1840s#1847#Hugo#writers and Napoleon

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

this week marks the 146-year anniversary of the St. Louis Commune of 1877 which powered the first general strike in us history and the first time workers had ever united and seized control of a US city.

German and French veterans of the 1848 revolutions and the 1871 Paris Commune, joined by members of the First International, led the revolt in my hometown. and rebellious, class-conscious workers rose up, embracing socialism as the solution to their exploitation.

the US isn't immune to Paris Commune–style eruptions of class consciousness. these types of historical events can provide valuable insights and motivation for an ongoing pursuit of a more just and equitable society, no matter how long ago they may seem to have taken place. in the grand scheme of things, our timeline is actually really quite small. America isn’t even 250 years old.

the St. Louis Commune of 1877 should be remembered by leftists today as a poignant reminder that the fight for workers’ rights and social justice can still transcend borders and can take root in unexpected places - even during a time that technology provided virtually no aid in these efforts - making the fight ever more important in locations today where workers desperately need representation.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spicy Napoleon Opinions

Because with Ridley Scott's film coming soon, now seems like a good time to put them out there.

Napoleon betrayed the French Revolution. Sure, there's a school of thought that says that it probably needed to end, but if Napoleon had used his time as First Consul to defend France, achieve peace with Britain and then transition into a democracy - basically any form of democracy - he'd rightly be regarded as a hero of liberty and the enlightenment. Instead, in declaring himself Emperor, he fundamentally betrayed everything it stood for.

Napoleon lost any right to be considered 'enlightened' when he brought back slavery and walked back women's rights. Instead it took until 1848 (ironically, under the rule of his nephew, Louis-Napoleon, soon to be Napoleon III) for France to finally abolish slavery, over a decade after Britain.

Despite this, Napoleon was not Hitler. That's a common bit of hyperbole. What Hitler did was almost unique in history, in that he planned and executed an industrialised genocide right down to the train timetables. Napoleon, for all his faults, wasn't generally genocidal.

At worst, the wars between Napoleon and the Coalitions were between morally equal parties. By the time Napoleon invaded Spain, he was morally the worst of the two. The war of 1805-07 can at least be said to have been forced on France by Britain, Austria and Russia. This can't be said for the invasion of Spain and later of Russia, which were acts of naked aggression whatever the geopolitical rationale.

Napoleon would wipe the floor with Washington. It wouldn't even be close. I have no idea what Deadliest Warrior was thinking. (Then I realise they tried to argue that gatling guns were superior to machine guns and I remember they probably just fixed it in favour of the Americans.)

The Napoleonic Wars were won and lost in Spain. Okay, this is a bit hyperbolic, but the 'Spanish Ulcer' was a quagmire that deprived Napoleon of valuable reinforcements at critical moments and influenced his decision-making process in 1812 (leading to the Russian disaster.)

And while we're on this period...

Andrew Jackson might be the most overrated general in American history. Congratulations, you defended a fortified position against an enemy advancing frontally across a marsh. Bravo. Anybody could have done it, and that the Battle of New Orleans propelled such an odious figure to national prominence is a crying shame.

36 notes

·

View notes