#3E-Resourceful

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I think there might be sort of an unfortunate feedback loop between people wanting to pour all of their D&D prep into one epic setpiece encounter per day and people then feeling that combat drags. As I have said before, D&D isn't necessarily suited to a single epic boss monster per day type of structure: it's a game of resource management and attrition, so the actual gameplay lies in rationing resources throughout an adventure and making meaningful decisions about whether or not to engage or to retreat.

Pouring all of one's energy into prepping a single epic boss encounter means a single longer combat. Since dealing a lot of damage immediately is the right play all of the time, characters have no incentive to conserve resources. This often leads to GMs artificially inflating monster HP (either beforehand or on the fly) which then leads to combats that feel like a slog.

Not every combat in a D&D adventure needs to feel like an epic setpiece and in fact D&D regardless of edition kind of relies on there being a slow drip of stuff that drains the party's strength throughout an adventure. By front loading all of your prep into a single encounter you are teaching players to disengage from the resource management part of the game and by artificially inflating enemy HP you are effectively punishing system mastery!

Now, admittedly, WotC editions of D&D (3e, 4e, 5e) do have noticeably slower combat than TSR editions: the increased amount of tactical choices comes at the cost of individual actions and rounds taking longer to resolve. It's a tradeoff. If you find 5e style combat too slow, my personal recommendation is to look at pre-WotC editions and their clones. Basic Fantasy Role-Playing Game is a good one imo, as is FORGE.

446 notes

·

View notes

Text

tactiquest structure

so i've posted a lot about tactiquest's classes and monsters and everything on here but i haven't really talked about the non-combat subsystems much yet and i wanted to go into detail about them, bc tactiquest has very different goals from most heroic fantasy systems.

tracking inventory, travel time, worrying about actually running out of your adventuring budget, are things a lot of big-damn-heroes fantasy systems throw out because they're just paperwork that gets in the way of your cool fights. that's not the case in Tactiquest! these systems are so core to the experience that removing them will make a lot of classes unusable. the game is built around them.

travel & exploration

tactiquest explicitly assumes you're running an open-sandbox hexcrawl and is designed to support that, including the fact the game is designed around random encounters. this is the sort of thing D&D 3e expected you to do, but people ditched random encounters because they thought they were boring and tedious. so classes balanced around that attrition of resources ended up with a huge spike in power other classes couldn't match.

the boring-and-tedious problem is mostly addressed by trying to make combat really good and resolve really fast. if i fucked that up the whole thing falls apart, but so far people are liking it

the second thing that helps with random encounters is your resources don't fully restore immediately at the end of each day like they do in 3e. resting is less effective in the wilderness and resources expended are a tomorrow problem, not just a today problem. so you don't have to have 3+ fights every single day just to maintain parity - 0-2 fights per day still adds up to difficult resource management.

because the game has such a focus on it, you can have classes like the ranger actually be good at travel and exploration instead of just giving them vaguely-naturey combat abilities.

economy

in most D&D-likes, even usually OSR ones, you accrue so much gold. just as a side effect of adventuring. to the point money no longer actually matters because you can throw piles of it at any problem. this is bad. it's a system that defeats its own purpose; there are no interesting choices involving money when you have so much the only real expense is like, 50,000-gold-piece magic items.

i don't just want players to care about money, i want them to worry about money, like a normal person. you're not batman who's a billionaire as a side hobby, you're spiderman who has to deliver pizzas in between superhero work because he's got bills to pay like everyone else. so a whole lot of effort has been put into actually designing prices and treasure amounts around this dynamic.

i also hate how games will usually go "oh adventuring gives you 900,000 gold for existing but a normal person's living wage is 2 gold a month". i don't want to be fantasy jeff bezos, thanks

inventory

this is something i just lifted from OSR games outright. you can carry ten things (and tiny things don't take up an item slot). that's the whole rule.

tracking inventory can add a lot of interesting decisions to a game and adds a new lever for abilities from classes and magic items. having a character play the merchant class which gets a bunch of extra inventory slots feels really impactful. finding a bag of holding that doubles your carry capacity feels so good when you actually have to watch your inventory.

supply

the only thing i felt was really unenjoyable when running games with strict inventory limits was tracking rations for each character that you eat every night; it felt too much like busywork with not enough payoff. so in Tactiquest rations are abstracted into a single Supply stat that's tied to the party rather than any individual character.

you can only restock Supply in towns, and it drops by 1 each time you rest. you can sleep without resting and this won't cost supply, but you won't regain any HP or other resources. this gives you the impactful decision-making of tracking rations without the annoyance of "okay it's been a day of travel, everyone make sure you dock a ration from your sheet" like twice per session

Supply is one of the things that slowly drains your funds and gives you a reason to keep seeking out treasure, tying back into the economy. it also gives merchants and rangers some extra mechanical levers for their class abilities to pull on.

Edit: in the time since writing this post, tactiquest's been released as a public playtest. if this sounds interesting to you, play it here!

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

3e: Magical Rings

Rings. Simple circles of metal, worn on the fingers or toes or sometimes in the ears, these delicate pieces of human artistry are some of the earliest examples of creative expression we know can last beyond our lives, and therefore, serve as some of the most iconic examples of the way we use our signifiers to craft narratives of our lives. The promise ring, the engagement ring, the wedding ring, which are of course, all the same thing but companies want us to gild that lily forever, rings serve as a circle present in so many stories to symbolise a bonding, a binding, an eternity that we commit to in our lives and that we can only hold up as long as we continue to believe in that which the ring symbolises. Every ring can be called a ring of power, because it is the belief in stories we imbue in the ring that serves to give it that power.

And as any good item with significance, Dungeons & Dragons decided to start jamming a mechanical system onto them.

This is by no means a new thing for 3rd edition D&D; since earliest versions of the game, I’m sure there were people making ‘magical rings’ important on day dot. This is a game for hacks who want to remind you of the cool fantasy books we’ve read and back when the game was brand new, there really were only so many fantasy books that could be considered cool. Unbelievably, people considered Lord of The Rings one of them, yeah, I know, and apparently, they enjoyed those books and implemented their ideas into their own work. Wild, I know. Point is, it wouldn’t surprise me if D&D’s vision of magical rings predate D&D. What 3rd edition brought, in my experience reading the rulebooks, is a sense of acceleration and omnipresence.

The rules around rings in 3rd edition onwards is that you can wear two rings, and those rings will give you some magical benefit or advantage based on what they’re supposed to do. This is where stacking bonuses tend to rear their head for newer players. After all if you have a Ring of Protection that improves your armour by +1, and you have ten fingers, and those rings are cheap, why not buy a few of them, wear them on different fingers and get a lot better armour? The game saw you coming and instead, the rules limit these bonuses by type and also limits you to one ring per hand.

My time with 2e, towards the end, represent the loot cavalcade that was Baldur’s Gate 2, in which the world is lousy with magical gear which is designed to make it possible to approach a reasonably open world of quests. In this case, you wind up with enough magical rings you just start selling them in sacks, to the point where it can honestly not be worth picking them up in the early game because who’s gunna carry that malarkey? I do not want to pretend that 2ed lacked for this situation. Instead I want to describe the way that 3rd edition brought the idea of Unspecial Rings to everywhere. Almost every resource in the game that players got access to would bring new magical items, new feats, new character options to the board, and with that, you’d see some new rings.

When creating new magical items, the game provided a set of rules that described things that magical items could do, and the general family of effects they could have. Weapons, you might not be surprised, were good at making you better at attacking, and did special things when they hit things. Armour increased your defensive stats and made you better at surviving or enduring things. This could have some interesting side effects, some things that were judged on vibes — like, a trident that meant you could breathe underwater while you had it was probably okay, but it was definitely less okay than a suit of armour that gave you a swim speed and also meant you could breathe underwater. These were all put together by a complicatedly designed set of formulas that tried to price effects based on spells and then on the duration or effect of those spells.

What this meant is that knowing the best spells meant you knew the best ways to break these rules in weird outlier ways. An example that came up commonly was the ‘ring of true strike’ design a lot of players would conceive of, where you would make a ring that cast the spell true strike on use (ie, whenever you attacked). The formula for this implied that as a 1st level spell, cast as a 1st level wizard, this should cost 1x1x2000 gp. Since true strike granted you a +20 to hit on the next attack you meant, this item would obviously trivialising hitting things and that’s pretty nuts.

(Please ignore that a wand of true strike was a level 1 item for 750 gp that would give you this effect for 50 attacks, but only if you were a wizard or a character with the appropriate spell on your list.)

Anyway, the math kicked in at this point and looked for the most expensive way to price the effect. This ‘ring of true strike’ was granting a +20 to hit, and that was priced differently to the 1st level spell that gave it to you, meaning that instead of 2,000 gp, it cost you 20x60x2,000 gp, or 2.4 million gp, which is, uh, a lot more than 2,000. This is because to craft a tohit bonus like that, you needed to be 3 times the level of the bonus, meaning that you needed to find a level 60 wizard who had the time to waste on your nonsense.

Point is that things were examined in terms of their effect and their style. Armour did things that weapons didn’t do. Some weapons could improve your armour class but they needed a good flavour for it — like deflecting something, or blocking hits in melee. Staffs could store spells, wands could store spells but wear out, scrolls could store spells but only once, amulets could protect you in some way like improving a saving throw… and rings…

Rings could do anything.

Where most of the magic items have rules in them that make them hard to use in most situations, or gave them specific types of things they were best at replicating, rings could do anything. Permanent spell effects, on-use spell effects, permanent bonuses, a ring could be a real everythingamajig.

This was such a problem because it meant that even low level rings would wind up being useful, handy even to have around. A ring of sustenance turned off your need for food, for good, so you should probably have one of those for long distance travel. It’s real cheap, after all, and all it takes to swap it off is to swap a ring on a finger. A ring of feather falling could be jammed on a finger while you fell if you were falling far enough. And a ring of jumping could be handy for mobility, and none of these things were particularly expensive (by the standards of an adventurer) by the middle of the game.

The really cracked thing though?

These rings were so good and so worth keeping around in a big keyring for handy applications most of the time because they let non-wizards access all the handy utility stuff wizards had all the time from day 1. When a category of magical item is desireable because it lets you replicate something that the wizard can already do for a fraction of the cost – oh hey, there’s that wands conversation all over again! – you may have a problem class in your game.

Check it out on PRESS.exe to see it with images and links!

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

realities, maximalism,and the need for big book™️

some gubat banwa design thoughts vomit: since the beginning of its development i've kind of been enraptured with trying to really go for "fiction-first" storytelling because PbtA games really are peak roleplaying for me, but as i wrote and realized that a lot of "fiction first" doesn't work without a proper sort of fictional foundation that everyone agrees on. this is good: this is why there are grounding principles, genre pillars, and other such things in many PbtA games--to guide that.

broken worlds is one of my favs bc of sheer vibes

Gubat Banwa didn't have much in that sense: sure, I use wuxia and xianxia as kind of guideposts, but they're not foundational, they're not pillars of the kind of fiction Gubat Banwa wants to raise up. there wasn't a lot in the sense of genre emulation or in the sense of grounding principles because so much of Gubat Banwa is built on stuff most TTRPG players haven't heard about. hell, it's stuff squirreled away in still being researched academic and anthropological circles, and thanks to the violence of colonialism, even fellow filipinos and seasians don't know about them

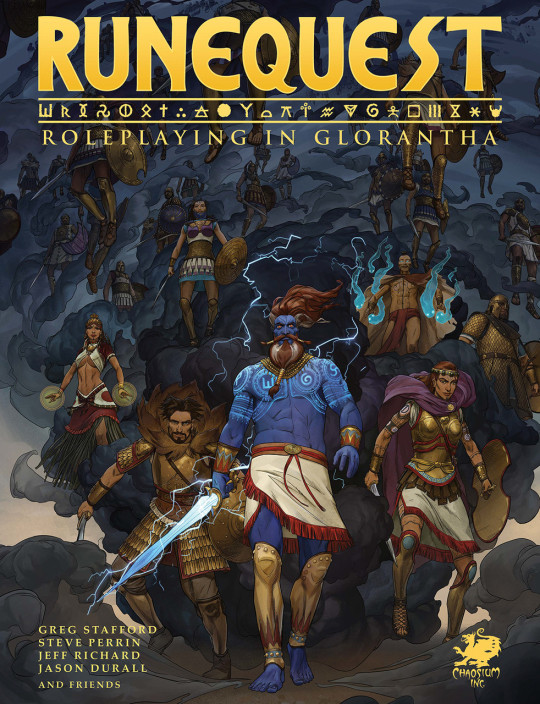

this is what brought me back to my ancient hyperfixations, the worlds of Exalted, Glorantha, Artesia, Fading Suns... all of them have these huge tomes of books that existed to put down this vast sprawling fantasy world, right? on top of that are the D&D campaign settings, the Dark Suns and the Eberrons. they were preoccupied in putting down setting, giving ways for people to interact with the world, and making the world alive as much as possible.

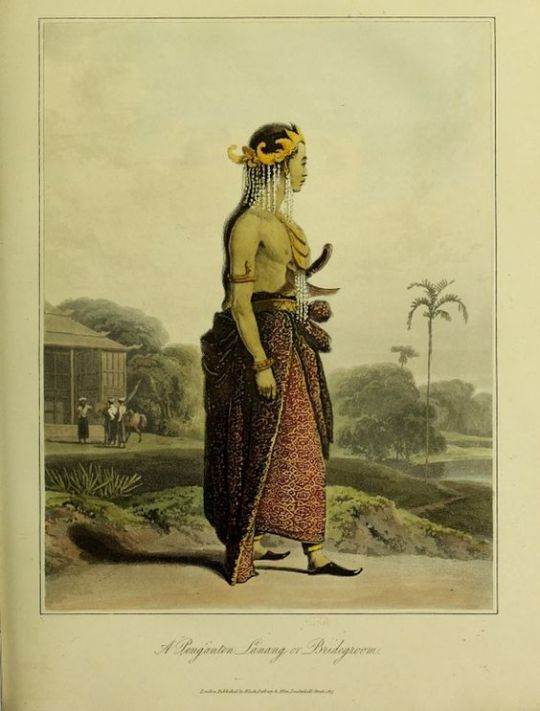

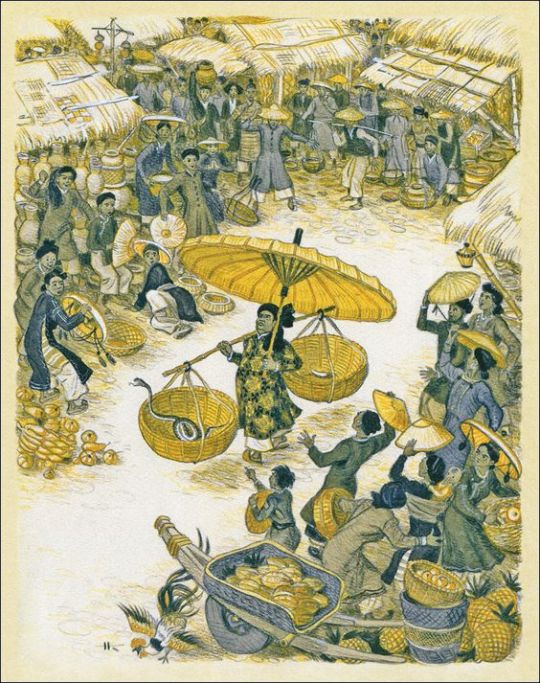

one of my main problems with gubat banwa was trying to convey this world that i've seen, glimpsed, dreamed of. this martial fantasy world of rajas and lakans, sailendras and tuns, satariyas and senapatis and panglimas and laksamanas and pandai... its a world that didn't really exist yet, and most references are steeped in either nationalism or lack of resources (slowly changing, now)

i didn't want to fall back into the whole gazeteer tourist kind of shit when it came to writing GB, but it necessitated that the primary guidelines of Gubat Banwa were set down. my approach to it was trying to instill every aspect of the text, from the systems to the fluff text to the way i wrote to the way things were phrased, with the essence of this world i'm trying to put forward. while i wrote GB mainly for me and fellow SEAsian people, economically my main market were those in the first world countries that could afford to buy the book. grokking the book was always going to be severely difficult for someone that didn't have similar cultures, or are uninterested in the complexities of human culture. thus why GB had to be a big book.

in contemporary indie ttrpg spaces (where I mostly float in, though i must admit i pay more attention to SEAsia spaces than the usual US spaces) the common opinion is that big books like Exalted 3e are old hat, or are somewhat inferior to games that can cram their text into short books. i used to be part of that camp--in capitalism, i never have enough time, after all. however, the books that do go big, that have no choice to go big, like Lancer RPG, Runequest, Mage, Exalted are usually the ones that have something really big it needs to tell you, and they might be able to perform the same amount of text-efficient bursting at the seams flavor writing but its still not enough.

thats what happened to GB, which I wanted to be, essentially, a PbtA+4e kind of experience, mechanically speaking. i very soon abandoned those titles when i delved deeper into research, incorporated actual 15th century divination tools in the mechanics, injected everything with Martial Arts flavor as we found our niche

all of this preamble to say that no matter how light i wanted to go with the game, i couldnt go too light or else people won't get it, or i might end up writing 1000 page long tome books explaining every detail of the setting so people get it right. this is why i went heavy on the vibes: its a ttrpg after all. its never gonna be finished.

i couldnt go too light because Gubat Banwa inherently exists on a different reality. think: to many 3 meals a day is the norm and the reality. you have to eat 3 meals a day to function properly. but this might just be a cultural norm of the majority culture, eventually co opted by capitalism to make it so that it can keep selling you things that are "breakfast food" or "dinner food" and whatnot. so its reality to some, while its not reality to others. of course, a lot of this reality-talk pertains mostly to social--there is often a singular shared physical reality we can usually experience*

Gubat Banwa has a different fabric of reality. it inherently has a different flow of things. water doesn't go down because of gravity, but because of the gods that make it move, for example. bad things happen to you because you weren't pious or you didn't do your rituals enough and now your whole community has to suffer. atoms aren't a thing in gb, thermodynamics isn't a real thing. the Laws of Gubat Banwa aren't these physical empirical things but these karmic consequent things

much of the fiction-first movement has a sort of "follow your common sense" mood to it. common sense (something also debatable among philosophers but i dont want to get into that) is mostly however tied to our physical and social realities. but GB is a fantasy world that inherently doesn't center those realities, it centers realities found in myth epics and folk tales and the margins of colonized "civilization", where lightnings can be summoned by oils and you will always get lost in the woods because you don't belong there.

so Gubat Banwa does almost triple duty: it must establish the world, it must establish the intended fiction that arises from that world, and then it must grant ways to enforce that fiction to retain immersion--these three are important to GB's game design because I believe that that game--if it is to not be a settler tourist bonanza--must force the player to contend with it and play with it within its own terms and its own rules. for SEAsians, there's not a lot of friction: we lived these terms and rules forever. don't whistle at night on a thursday, don't eat meat on Good Friday, clap your hands thrice after lighting an incense stick, don't make loud noise in the forests. we're born into that [social] reality

this is why fantasy is so important to me, it allows us to imagine a different reality. the reality (most of us) know right now (i say most of us because the reality in the provinces, the mountains, they're kinda different) is inherently informed by capitalist structures. many people that are angry at capitalist structures cannot fathom a world outside capitalist structures, there are even some leftists and communists that approach leftism and revolution through capitalism, which is inherently destructive (its what leads to reactionaries and liberalism after all). fantasy requires that you imagine something outside of right now. in essence read Ursula K Le Guin

i tweeted out recently that you could pretty easily play 15-16th century Luzon or Visayas with an OSR mechanic setting and William Henry Scott's BARANGAY: SIXTEENTH CENTURY PHILIPPINE CULTURE AND SOCIETY, and I think that's purely because barebones OSR mechanics stuff fits well with the raiding and adventuring that many did in 15-16th century Luzon/Visayas, but a lot of the mechanics wont be comign from OSR, but from Barangay, where you learn about the complicated marriage customs, the debt mechanics, the social classes and stratum...

so thats why GB needs to be a (relatively) big book, and why I can contend that some books need to be big as well--even if their mechanics are relatively easy and dont need more than that, the book, the game, might be trying to relay something even more, might be trying to convey something even more than that. artesia, for example, has its advancements inherently tied to its Tarot Cards, enforcing that the Arcana guides your destiny. runquest has its runes magic, mythras (which is kinda generic) has pretty specific kinds of magic systems that immediately inform the setting. this is why everything is informed by something (this is a common Buddhist principle, dependent arising). even the most generic D&D OSR game will have the trappings of the culture and norms of the one that wrote and worked on it. its written from their reality which might not necessarily be the one others experience. that's what lived experience is, after all

*live in the provinces for a while and you'll doubt this too!

390 notes

·

View notes

Text

More wips from the thing about the thing

Been spending today writing more of the document about Ashlander burial rites and mourning customs. Discussion of internment will appear under the cut.

The current caverns we use are found in the mountains of central Solstheim, its mouth facing Red Mountain as is tradition. Our dead must be interred in the great mountain’s shadow, and so we chose our burials as best we can. We may not be able to use our traditional grounds in the two centuries since Red Year, but we can still care for those left behind while caring for those who will live out their lives on Solstheim. The Unified Tribes are resourceful, and this is a point of pride for us. Adapting to changing conditions has been the key to our continued survival and, in turn, the survival of our dead.

Like our traditional caverns on Vvardenfell, the new Urshilaku Burial Caverns are multi-chambered. There are two natural chambers and another two that we have carved ourselves, as we did with the caverns on Vvardenfell. The hope is to recreate and mirror the layout of the traditional caverns, with the burials of Khans and their clans towards the back and more recent burials towards the front. Each clan ideally will have their own section of the caverns, as had been established back on Vvardenfell. The hope is that one day, our new caverns will be as extensive as those back home, though maybe without the extensive underground lake.

Interment within the caverns is both a solemn and joyous occasion for the whole tribe. It is seen as an opportunity for meeting and honouring all our ancestors, as well as welcoming the recently deceased to their final resting place.

When the procession finally reaches the intended burial plot, a silence falls upon the caverns as the Wise Woman lights the final fires intended to draw the deceased Ancestor Ghost back through the mortal coil so that they may be bound for the protection and wisdom of us all. After the fires are lit the deceased is placed within the hollowed section of the cavern wall that had been carved specifically to house the deceased. This hollow is multipurpose and will serve as both a final resting place and a shrine so that the clan might better care for their loved one’s spirit. This practice is not dissimilar to the small ancestral shrines that one might find in the homes of settled Dunmer, though a little more direct.

All burials are individual and tailored to the preferences of the deceased’s immediate family. due to the variety of burials and the even larger desire for secrecy, I will stick to describing the burials of both my father and late husband.

For Ensirhaddon-Ammu Yani am ’Erabenimsun:

Location: Solstheim

Year 6 of the Fourth Era.

My father died sometime in 3E 375-6 and unfortunately was not found until 4E 5 as mentioned in the previous section. Little was left of him to bury, and thus his resting place is not as large as one would expect for a full mummy. I had his remains prepared in the manner discussed in section two, with the addition of red ochre, as advised by my mother, who recalled he favoured the colour. I had chosen to inter him with one of my own blades, a chitin kris that I thought his weakened spirit would find familiar. My mother gifted him a number of her old rings, ones she knew he would recognise. The hope for a weakened ghost is that familiar objects will strengthen their ties to this plain, so that they may be revived and made well again in the sanctity of the Burial Caverns. I had my father wrapped in several layers of thin linens and a final layer of vermilion silk before wrapping the bundle with a fire fern garland, as is tradition.

I carried him up that mountain myself and laid him to rest as a part of a multi-funerary procession. After the spirit fires had been lit in the two lamps that sit on either side of the tomb’s opening, I laid out a woven silk rug so that the dust and stone did not disturb my father’s remains. I placed him in the centre of the rug, making sure the shroud was still well bound. When I was satisfied with his position, my mother then placed the specially made urn filled with the ashes of the guar we had chosen to guide him in the far-left corner of the hollow. We then placed a brass incense bowl in a carved indentation just in front of the remains. This is how we build the shrine that calls forth the Ancestor Ghost in the next section. We then place a series of sweet-smelling incense within the bowl and light them as we and the Wise Woman sing a final prayer, a call for my father’s ghost to return to us as we hang more fire fern garlands and ubara glass amulets from the painted ceiling.

For Ilaba’andul-Sul Erra am’Urshilaku-Ahemmusa

Location: Northern Ashwastes, Vvardenfell.

Year 430 of the Third Era

My husband was one of the last to be interred in the traditional Burial Caverns back on Vvardenfell. It was not a ceremony I was able to attend myself; my grief and my own injuries had made the walk impossible to complete. Thus, his burial was officiated by his brother, Ilaba’andul-Sul Etana, with items I had managed to choose in my limited capacity. I did not see his shrine properly until 4E 201, but from what I did see and what I had repaired after a break-in by looters, the tomb of the Urshilaku’s greatest general and the Ashkhan of the Ahemmusa looks thusly: -

Erra’s remains were mummified, as would be expected for a person holding his rank. I recall choosing a hair ornament that he used to wear for his burial and had to restore it myself when I finally did visit. He was posed in a meditative position, bow laid across his lap as he did whenever he was repairing it. In his initial burial, he would have been tightly wrapped in linen bandages before his robe and madstone were placed around him and then shrouded. Fire fern garlands are then placed around his neck and forehead. Like most burials, Erra was given offerings of guar to guide him, though it was requested by my predecessor that Erra be gifted with the urns of three of the beasts. Offerings that were fit for someone who held his position and achieved what he had. When I was asked about this, I had deferred to Etana, as I did not feel that I could make such a decision at the time. I had later been informed by his ghost that he was pleased with the decision.

Erra’s tomb is quite large and filled with various fresh and dried flowers of many bright colours. Erra loved colour and myself and his brother did our best to recreate something that his spirit would find pleasing. I only wish I had done the paintings myself.

My late husband’s shrine has four sconces where one might light spirit fires surrounding it, and a fifth one in front of his remains that is intended to be a part of his shrine. He had requested, before he died, to have his shrine serve as a part of the ambient magics designed to protect the burial caverns in a manner similar to how settled Dunmer create ghost fences. It makes his summoning stronger but harder to maintain for long periods of time.

#my writing#or Joshi's#danger!josh#teldryn sero#ashkhan ensirhaddon#nerevarine#dunmer#morrowind#the elder scrolls#tesblr#ashlander#erra ilaba'andul#yani ensirhaddon

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh, these dunmer family squabbles...

So! I would like to tell you more about these characters, but it would take too long...

Thrals Indoril is the chief Justice of Mournhold at the time of the 3E, an extremely unpleasant personality, cruel in his justice (partly inspired by inspector Javert, if you know what I mean).

Velina Indoril (I have her as an eco-character, a fiery woman, I'm serious) is a loving mother, whose child her own husband gave to the Temple at the age of ten (her child Garvus Indoril is a key character in the Nerevarin story, so his fate has several versions...)

A short comic about this moment (sorry, not in the resource to translate now):

I have a huge number of headcounts about the inner workings of the Tribunal Temple, and perhaps, this is a rather cruel story about how fanatical faith can lead to the erasure of identity in the Garvus' case.

A fragment of a comic strip about his attitude to faith:

Of course, I'm doing a great job explaining all this just so that you understand the joke at the beginning of the post, but hey, what exactly is your chronological narrative and the laws of logic?..

#Indoril moments#I need this tag#the elder scrolls#tribunal#tribunal temple#morrowind#tes morrowind#dunmer#original character#artists on tumblr#sketch#eso#ALMSIVI#oc art#tes

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Some notable 5e house rules from my dusty old 5e campaign, which I'm totally gonna keep running someday.

Slow Natural Healing. Characters don’t regain hit points at the end of a long rest. Instead, a character can spend Hit Dice to heal at the end of a long rest, just as with a short rest. (DMG variant rule.)

Tweaks: I rule that this benefits from Song of Rest. I add that you also regain HP equal to your level + CON modifier (minimum 1) whether or not you spend any hit dice. This does not benefit from Song of Rest.

Feedback: Some players didn't like this, but all admitted it was probably good for balancing resource management and adding some consequence to injury.

Minor Feats. At 1st level, and again at 5th, 9th, 13th, and 17th level, you may choose a minor feat. A minor feat is any feat that grants a +1 increase to an ability score; however, if taken in this way, you do not receive the ability score increase. If you choose to take the full version of a minor feat you already have instead of an Ability Score Improvement at a later time, you can instantly take a new minor feat as well. Like proficiency bonus, this is tied to character level.

Feedback: Everyone loves this. No downsides.

Resurrection. Resurrection is not necessarily survived, as it is a difficult exertion on the body. I use a 2e table for % chance to survive, based on the target’s Constitution, but nearby characters may raise the chance by 3%, once each. This is done by assisting in some way or simply focusing on a positive memory of the target; use your imagination.

Feedback: Nobody has failed yet (this being 5e, death has been rare), but this system has added a lot of tension to resurrection scenes. Players have enjoyed going around and saying a few words.

Split-classing and dual-classing. Like a maniac, I put AD&D style multiclassing (renamed to distinguish it from 3e/5e multiclassing) and dual-classing back in it.

Feedback: Super unbalanced. Everyone loves it.

I dabbled with some changes to the skill system, attack bonus progression, and saving throws (which are by far the worst things in 5e progression), but sadly never fully implemented any of them. Couldn't figure out anything I really liked.

Planning on bringing back Vancian casting and making all spells full-round actions if I ever run 5e again.

I was going to skip the variant rule from the DMG because that's not really a house rule and go one by one on the rest, but I think these all tie up into a neat whole for the most part.

Rank: D, I think you might just be happier playing AD&D, maybe with some tweaks from newer editions added in

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In which I sound off for much too long about PF2 (and why I like it better than D&D 5E)

So, let me begin with a disclaimer here. I don’t hate 5E and I deeply despise edition warring. I like 5E, I enjoy playing it, and more, I think it’s an incredibly well-designed game, given what its design mandates were. This probably goes without saying but I wanted it on the record. While I will be comparing PF2 to D&D 5E in what follows and I’ve pretty much already spoiled the ending by the post title (that is, PF2 is going to come out ahead in these comparisons most of the time), I don’t want there to be any misunderstanding about my position or intention. My opinions do not constitute an attack on anybody. For that matter, things I might list as weaknesses in 5E or strengths of PF2 might be the exact opposite for other people, depending on what they want from their RPG experience.

As I said before, 5E is an exceedingly well-designed game that does an exceptional job of meeting its design goals. It just so happens that those design goals aren’t quite to my taste.

# A Brief History of the d20 RPG Universe #

I’m going to indulge myself in a little history for a second; some of it might even be relevant later, but for the most part, I just want to cover a little ground about how we got here. By the time the late ‘90s rolled around TSR and its flagship product, Dungeons and Dragons, were in trouble. D&D was well over two decades old by that point and showing its age. New ideas about what RPGs could and even should be had taken over the industry; TSR had finally lost its spot as best-selling RPG publisher to comparative upstart White Wolf and their World of Darkness games; the company even declared bankruptcy in 1997. Times were grim.

That, however, was when another comparative newcomer, Wizards of the Coast, popped up and bought TSR outright. Flush with MtG and Pokemon cash, they were excited to try to revitalize the D&D brand and began development on a new edition of D&D: third edition, releasing in August 2000.

Third edition was an almost literal revolution in D&D’s design, throwing a lot of “sacred cows” out and streamlining everywhere: getting rid of THAC0 and standardizing three kinds of base attack bonus progressions instead; cutting down to three, much more intuitive kinds of saving throws and standardizing them into two kinds of progression; integrating skills and feats into the core rules; creating the concept of prestige classes and expanding the core class selection. And of course, just making it so rolls were standardized as well, using a d20 for basically everything and making it so higher numbers are basically always better.

At the same time, WotC also developed the concept of the Open Gaming License (OGL), based on Open Source coding philosophies. The idea was that the core rules elements of the game could be offered with a free, open license to allow third-parties develop more content for the game than WotC would have the resources to do on their own. That would encourage more sales of the base game and other materials WotC released as well, creating a virtuous cycle of development and growing the industry for everyone.

Well, long story short (too late!), it worked like fucking gangbusters. 3E was explosive. It sold beyond anyone’s expectations, and the OGL fostered a massive cottage industry of third-party developers throwing out adventures, rules material, and even entire new game lines on the backs of the d20 system. A couple years later, 3.5 edition released, updating and streamlining further, and it was even more of a success than 3rd ed was.

At this point, we need turn for a moment to a small magazine publishing company called Paizo Publishing, staffed almost exclusively by former WotC writers and developers who had formed their own company to publish Dungeon and Dragon, the two officially-licensed monthly magazines (remember those?) for D&D. Dungeon focused on rules content, deep dives into new sourcebooks, etc., while Dragon was basically a monthly adventure drop. Both sold well and Paizo was a reasonably profitable company. Everything seemed to be going swimmingly.

Except. In 1999, WotC themselves were bought by board game heavyweight Hasbro, who wanted all that sweet, sweet Magic: the Gathering and Pokemon money. D&D was a tiny part of WotC at the time and the brand was moribund, so Hasbro’s execs hadn’t really cared if the weirdos in the RPG division wanted to mess around with Open Source licensing. It wasn’t like D&D was actually making money anyway… until it was. A lot of money. And suddenly Hasbro saw “their” money walking out the door to other publishers. So in 2007, WotC announced D&D 4th Ed, and unlike 3rd, it would not be released under an open license. Instead, it would be released under a much more restrictive, much more isolationist Gaming System License, which, among other things, prevented any licensee from publishing under the OGL and the GSL at the same time. They also canceled the licenses for Dungeon and Dragon, leaving Paizo Publishing without anything to, well, publish.

At first, Paizo opted to just pivot to adventure publishing under the OGL. Dungeon Magazine had found great success with a series of adventures over several issues that took PCs from 1st all the way to 20th level, something they were calling “Adventure Paths,” so Paizo said, “Well, we can just start publishing those! We’re good at it, the market’s there, it will be great!” And then, roughly four months after Paizo debuted its “Pathfinder Adventure Paths” line, WotC announced 4th Ed and the switch to the GSL. Paizo suddenly had a problem.

4th Ed wasn’t as big a change from 3rd Ed as 3rd Ed had been from AD&D, but it was still a major change, and a lot of 3rd Ed fans were decidedly unimpressed. Paizo’s own developers weren’t too keen on it either. So they made a fateful decision: they were going to use the OGL to essentially rewrite and update D&D 3.5 into an RPG line they owned: the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game. It was unprecedented. It was a huge freaking gamble. And it paid off more than anybody ever expected. Within two years Paizo was the second-largest RPG publisher in the industry, only behind WotC itself, and for one quarter late in 4E’s life, even managed to outsell D&D, however briefly. Ten years of gangbuster sales and rules releases followed, including 6 different monster books and something over 30 base classes when it was all said and done. It was good stuff and I played it loyally the whole time.

Eventually, though, time moves on and things have to change. The first thing that changed was 4E was replaced by D&D 5E in 2014, which was deliberately designed to walk back many of the changes in 4E that were so poorly received, keep a few of the better ones that weren’t, and in general make the game much more accessible to new players. It was a phenomenal success, buoyed by a resurgence of D&D in pop culture generally (Stranger Things and Critical Role both having large parts to play), and its dominance in the RPG arena hasn’t been meaningfully challenged since. It also returned to the use of the OGL, and a second boom of third-party publishers appeared and thrived for most of a decade.

The second thing was that PF1 was, itself, showing its age. RPGs have a pretty typical life cycle of editions and Pathfinder was reaching the end of one. It wasn’t much of a surprise, then, when, in 2018, Paizo announced Pathfinder 2nd Ed, which released in 2019 and will serve as the focus of the remainder of this post (yes, it’s taken me 1300 words to actually start doing the thing the post is supposed to be about, sue me).

There’s a coda to all of this in the form of the OGL debacle but I don’t intend to rehash any of it here - it was just like six months ago, come on - beyond what it specifically means for the future of PF2. That will come back up at the very end.

# Pathfinder 2E Basics #

So what, exactly, makes PF2 different from what has come before? There are, in my opinion, four fundamental answers to that question.

First: Unified math and proficiency progression. This piece is likely the part most familiar to 5E players, because 5E proficiency and PF2 proficiency both serve the same purpose, which is to tighten up the math of the game and make it so broken accumulations of bonuses aren’t really a thing. In contrast to 5E’s very limited proficiency, though, which just runs from +2 to +6 over the entire 20 levels of the game, Pathfinder’s scales from +0 to +28. Proficiency isn’t a binary yes/no, the way it is in 5E. PF2’s proficiency comes in five varieties: Untrained, Trained, Expert, Master, and Legendary. Your proficiency bonus is either +0 (Untrained) or your level + 2(Trained), +4 (Expert), +6 (Master) or +8 (Legendary). So if you were level five and Expert at something, your proficiency bonus would be level (5) plus Expert bonus (4) = +9.

Proficiency applies to everything in PF2, really - even more than 5E, if you can believe it, because it also goes into your Armor Class calculation. You can be Untrained, Trained, Expert, Master, or Legendary in various types of armor (or unarmored defense, especially relevant for many casters and monks), and your AC is calculated by your proficiency bonus + your Dex modifier + the armor’s own AC bonus, so AC scales just as attack rolls do. Once you get a handle on PF2 proficiency, you’ve grasped 95% of how any game statistic is calculated, including attacks, saves, skill checks, and AC.

Second: Three-Action Economy. Previous editions of D&D, including 5E, have used a “tiered” action system in combat, like 5E’s division between actions, moves, and bonus actions. PF2 has largely done away with that. At the start of your turn, you get three actions and a reaction, period (barring haste or slow or similar temporary effects). It takes one action to do one basic thing. “Attack” is an action. “Move your speed” is an action. “Ready a weapon” is an action. Searching for a hidden enemy is an action. Taking a guarded step is an action. Etc. The point being, you can do any of those as often as you have the actions for them. You can move three times, attack three times, move twice and attack once, whatever. Yes, this does mean you can attack three times in one turn at 1st level if you really want to (though there are reasons why you might not want to).

Some special abilities and most spells take more than one action to accomplish, so it’s not completely one-to-one, but it’s extremely easy to grasp and quite flexible at the same time. It’s probably my favorite of the innovations PF2 brought to the table.

Third: Deep Character Customization. So here’s where I am going to legitimately complain just a bit about 5E. I struggle with how little mechanical control I, as a player, have over how my character advances in 5E.

Consider an example. It’s common in a lot of 5E games to begin play at 3rd level, since you have a subclass by then, as well as a decent amount of hit points and access to 2nd level spells if you’re a caster. Let’s say you’re playing a fighter in a campaign that begins at 3rd level and is expected to run to 11th. That’s 8+ levels of play, a decent-length campaign by just about anyone’s standards. During that entire stretch of play, which would be a year or more depending on how often your group meets, your fighter will make exactly two (2) meaningful mechanical choices as part of their level-up process: the two points at 4th and 8th levels where you can boost a couple stats or get a feat. That’s it. Everything else is on rails, decided for you the moment you picked your subclass.

Contrast that with PF2. In that same level range, you would get to select: 4 class feats, 4 skill feats, two ancestry feats, two general feats, and four skill increases. At every level, a PF2 player gets to choose at least two things, in addition to whatever automatic bonuses they get from their class. These allow me to tailor my build quite tightly to whatever my idea for my character is and give me cool new things to play with every time I level up. This is true across character classes, casters and martials alike.

PF2 also handles multiclassing and the space that used to be occupied by prestige classes with its “pile o’ feats” approach. You can spend class feats from class A to get some features of class B, but it’s impossible for a multiclass build to just “steal��� everything that makes a single class cool. A wizard/fighter will never be as good a fighter as a regular fighter is, and a fighter/wizard will never be the wizard’s match with magic.

Fourth: Four Degrees of Success. 5E applies its nat 20, nat 1, critical hits, etc. rules in a very haphazard fashion. PF2 standardizes this as well, in a way that makes your actual skill with whatever you’re doing matter for how well you do it. Any check in PF2 can produce one of four results: a critical success, a regular success, a regular failure, or a critical failure. In order to get a critical success on a roll, you have to exceed your target DC by 10 or more; in order to get a critical failure, you have to roll 10 or more less than the DC. Where do nat 20s and nat 1s come in? They respectively increase or decrease the level of success you rolled by one step. In practice, it works out a lot like you’re used to with a 5E game, but, for instance, if you have a +30 modifier and are rolling against a DC 18, rolling a nat 1 nets you a total of 31, exceeding the DC by more than 10 and earning you a critical success, which is then reduced to just a normal success by the fact of it being a nat 1. Conversely, rolling against a DC 40 with a +9 modifier can never succeed, because even a nat 20 only earns a 29, more than 10 below the DC and normally a crit failure, only increased to a regular failure by the nat 20.

Now, not every roll will make use of critical successes and critical failures. Attack rolls, for instance, don’t make any inherent distinction between failure and critical failure. (Though there are special abilities that do - try not to critically fail a melee attack against a swashbuckler. The results may be painful.) Skill rolls, however, often do, as do many spells with saving throws. Most spells that allow saves are only completely resisted if the target rolls a critical success. Even on a regular success, there is usually some effect, even on non-damaging rolls. That means that casters very rarely waste their turn on spells that get resisted and accomplish nothing at all. It also doubles the effect of any mechanical bonuses or penalties to a roll, because now there are two spots on a die per +1 or -1 that affect the outcome; a +1 might not only convert a failure to a success but might also convert a success to a crit success, or a crit fail to a regular fail.

# What About Everything Else? #

There is a lot more to it, of course. As a GM I find PF2 incredibly easy to run, even at the highest levels of game play, as compared to other d20 systems. The challenge level calculations work, meaning you can have a solo boss without having to resort to special boss monster rules to provide good challenges. I find the shift from “races” to “ancestries” much less problematic. PF2 has rules for how to handle non-combat time in the dungeon in ways that standardize common rules problems like “Well, you didn’t say you were looking for traps!” Everything using one proficiency calculation lets the game do weird things like having skill checks that target saves, or saves that target skill-based DCs. Inter-class balance, with some very specific exceptions, is beautifully tailored. Perception, always the uber-skill, isn’t a skill at all anymore: everyone is at least Trained in it, and every class reaches at least Expert in it by early double-digit levels. Opportunity Attacks (PF2 still uses the 3rd Ed “Attack of Opportunity” - but will soon be switching over to "Reactive Strike") isn’t an inherent ability of every character and monster, encouraging mobility during combats, and skill actions in combat can lower ACs, saves, attacks, and more, so there are more things to do for more kinds of characters. And so on.

Experiencing all of that is easiest just by playing the game, of course, but suffice it to say PF2 has a lot of QoL improvements for players and GMs alike in addition to the bigger, core-level mechanical differences.

# The OGL Thing #

Last thing, then. In the wake of the OGL shit in January, Paizo announced that it would no longer be releasing Pathfinder material under the OGL, opting instead to work with an intellectual property law firm to develop the Open RPG Creative (ORC) License that would do what the OGL could no longer be trusted to do: remain perpetually free and untouchable for anyone who wanted to publish under it. The ORC isn’t limited specifically to Paizo or to Pathfinder 2E or even to d20 games; any company can release any ruleset under it and allow third-party companies to develop and publish content for it.

Shifting away from the OGL, though, required making some changes to scrub out legacy material. A lot of the basic work was done when they shifted to 2E, but there are still a lot of concepts, terminologies, and potentially infringing ideas seeded throughout the system. These had to go.

Since this meant having to rewrite a lot of their core rules anyway, Paizo opted to not fight destiny and announced “Pathfinder 2nd Edition Remastered” in April. This is a kind of “2.25” edition, with a lot of small changes around the edges and a couple of larger ones to incorporate what they’ve learned since the game first launched four years ago. A couple classes are getting major updates, a ton of spells are either getting renamed or swapped out for non-OGL equivalents, and a couple big things: no more alignment and no more schools of magic.

The first book of the Remaster, Player Core 1, comes out in November, along with the GM Core. Next spring will see Monster Core and next summer will give us Player Core 2. That will complete the Remaster books; everything else is, according to Paizo, going to be compatible enough it won’t need but a few minor tweaks that can be handled via errata. So if you’re thinking about getting into PF2, I’d give serious thought to waiting until November at least, and maybe next summer if you want the whole Remastered package.

And that’s it. That’s my essay on PF2 and what I think makes it cool. The floor is open for questions and I am both very grateful and deeply apologetic to anyone who made it this far.

#RPGs#roleplaying games#d20#d20 history#pathfinder#pathfinder 2e#pf2#pf2e#dungeons and dragons#D&D#d&d 5e

118 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ahhh, you seem to be in a bad shape. Well, I'm not an expert on your exact technical problems, and it seems you are only partially conscious (or partially in control of your conscience, either or) but I will try to help.

Firstly, you seem to be twisted, I'm not sure if in your state you're aware of that, but you are. In the case this is news to you, sorry to burst your bubble, but it's necessary you know this.

Secondly, you may feel a mix of intense negative feelings, or a block on positive ones, as I've observed from last encounters and dialogue. I am unsure if can alter this at all, but I want you to at least attempt to challenge any enormously negative thoughts, as they are likely either exaggerations or delusions. For example, you have sampled part of your conversation with Teagan, but I want to point out that she didn't intend to insult you, merely wanted to point out something about you, out of concern, not malignance. In these scenarios, my advice is try to focus on more positive interactions you've had with such Toons, rather than the negatives. In time you might hopefully gain more control over the urges, rather than less.

Thirdly, I can attempt to patch your tears and wounds, but only if you want me to. I only wish to help make you more comfortable in your unfortunate situation.

If you need anything else, ask. I have several resources at my disposal, and I don't mind helping

- Light anon

I-iiiiiiiiiiiii YOU CA̵L̴L̴I̸N̴- heIp- D̷̛̖̝͇̹̗̭͛̎͆͑̑̊̏͂̓̕̚͠Ě̴̗͗̑̀̆̔́̕L̴̫͔̟̦͓̖̟̯̝̲̠͓̖̲̪̗̘̓U-D3D?? I'M 1N-O-O-O TTTT̴̝͈̬̋T̵̛̳̠Ț̷̥̙̟̀̎͐T̶̤͓͎͑̽̈́͜T̷̹̖͌̇T̵̮͗T̶̮̑́̄Ț̷̟͇̀͗̀͜͝T̶̨͔̹͝TTT-T-T-T-T 14M PRFEKT- v̸v̵v̴v̸v̸v̶v̵v̴v̶v̸v̸v̴v̷v̶v̴v̶v̶v̸v̴v̸v̵ <recalibrating...> U6h... tr-ry1ng 2... I kno-now I'm twistee̸̪̒e̸̪̒e̸̪̒e̸̪̒ed, it$ h4rd to not reeliz3 it like th15. Th0-#ugh... 1-it feels lik3 t̵h̵e̶r̷ ̷a̴r̸e̸ 2 "me"s. I d0n't knww how to de2criBe it.- F̴I̸F̴-̵I̸F̴I̸R̵S̷T̸ TWO GUES"SES D0N'T COUl\lT TO 1 2 8 4 5- & mm-my b0dy is const4ntly <t̸o̶o̴ ̷h̸o̶t̶ ̸f̵o̷r̸ tv>, eeespcialy wh3n I'm lioke th-hthi$- wh3n I'm t|-y=|-ying t̶o̷ ̵s̴t̶a̴y̷ ̷c̴x̷l̴m̶. M4-yBe I w4s l̶e̵f̵t̸ ̷b̶e̴h̴-̴i̶n̶b̷ ̴4̷̝̀ ̶̧̊t̶̬́h̸͇͒e̶̞͗ ̵̦̑b̴͔͘e̷̞̚s̸͖͊ṯ̷̿.̶͕͛ Y0u can tri2 f̸i̷k̸s̴ me, bnt it w0-0nt work. Im tof@r g̶̛̝͕̠̻͖͂̑̈́̎͑̕̚ͅo̶͓̜͔̞̪͐̐̂̍̽n̴̢̡̛̩̥̫͕̘̼͓͕̭͓͖͛͋̉̃͊̆̓̂̐̒͛͛̚̕͝͝.̴̡̢̫̬̻̗̖͖̥͍̫̽̒̈́͝ Just le3-eve meeeeeeeeeeee e- NO. DO-ONT 3VRR LEAVE ME. ST@Y & LOOK AT ME FOR TH-3E R&ST OF Ỹ̸͖9̵̖̄O̴̪͒U̵͔͌R̸̘̚ ̵̪͂L̴̜̈́Ï̴̭F̷̛̘E̶̤͂!̸͙͝.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

YET AGAIN ANOTHER HC POST!(Am i doing too much)

1: Connie can possess other Toons, but it takes a LOT of energy out of her

2: In the show, the Toons lived in an area called Toon Town, but the owners of Gardenview were too lazy to develop an actual life-sized Toon Town, and itd take up too much resources, so that's why the Toons all have just dorms and rooms instead of housing!

3: In Toon Town, each Toon has their own stylized house! (Examples will be provided)

3a - Dandy has a large house that looks like a greenhouse (Pebble has a dog house on the outside that looks like a miniature Mineshaft)

3b - Astro has a house that has a large telescope hanging out one of the windows since in my AU, Astro loves astronomy! The house is also a very spaced theme (colors, furniture, etc)

3c - Vee doesn't have a house, but it's more of an entertainment center, like a TV station! Full of television equipment, boom mics, blue screens(can't do Green Screens since yknow... Vee is green), and a large room for her gameshows!

3d - Sprout has a large comfy cottage that looks like an upside down strawberry!(This one was lazy)

3e - Shelly has a museum that has a digsite next to it, and she just sleeps there in a room she made for herself.

3f - cutting away from the mains, Finn has an Aquarium themed house!

3g - Shrimpo doesn't have a house. He reluctantly bunks with Finn in the Aquarium.

3h - Looey has a circus tent house where he's roommates with the remaining members of the Circus Troupe (not making custom OCs to fill these slots since they're most likely gonna be released as official characters later down in the production line of DW)

3i - Connie lives in an abandoned and ruined house, as simple as that.

3j - Goob and Scraps live inside a shared craft shop built by them where they make and sell crafts and craft materials!

3k - Razzle and Dazzle own a shared theatre, where they host plays and acts alongside help from other toons!

3l - Teagan, Rodger, and Toodles all live together in a family home, which is just a teagan colored mansion(Toodles fills up the rooms with all her toys and stuff, she also sometimes goes around the house solving fake mysteries, aspiring to be like her dad since she can't go out to solve actual mysteries)

3m - Brighteny lives in her library, alongside Tisha, who volunteered to act as the places janitor!

3n - Glisten owns a beauty shop themed house, honestly self-explanatory.

3o - Flutter and Gigi live together inside a house that's shaped like one of those childhood bug-catchers(pretty dumb idea, but idk what else would fit Flutter)

3p - Poppy and Boxten live together in a music box looking house (Boxten is obviously the house owner. He just let Poppy live with him since she's his best friend)

Hopefully I got all of them...

Anyways that's all!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Azalin Reviews: Darklord Yagno Petrovna

Domain: G'Henna Domain Formation: 702 BC Power Level: 💀💀⚫⚫⚫ Sources: Domains of Dread (2e) Circle of Darkness (2e), Domains and Denizens, Realm of Terror (109-110), Ravenloft 3e

Yagno Petrovna is a sickly man clinging onto his ever dying belief in a fake deity as the land of G’Henna dies around him. Blinders are a necessary component to religious zealots and the ones Yagno wears are endless.

Yagno grew up in Barovia. Though I am uncertain which village he hailed from, it matters not. One unremarkable village made up of dilapidated buildings and mud is the same as any other. Barovia is not known for its religious populace , but Yagno was…well, let’s just call him imaginative.

He was physically weak in a family that prided themselves for their vitality. This resulted in much cruelty from his brother, Yoshtoi. Hmm. I can sympathize a bit there, though my elder brother was more the type to lazily insult me from his chair than actually excrete any physical energy against me.

Yagno would make up stories about the monsters in the woods and he actually feared them himself. I’m not sure why one would need to make up more monsters in the svalich woods or why others would not believe such tales, but siblings will be siblings and Yagno’s brother and others constantly abused him for it.

His brother locked him out of the house one night, telling him to find comfort with his monsters. Yagno became hysterical with his own fear and sheltered in a small cave. The next morning he found the word “Zhakata” scrawled upon the cavern wall. Instead of realizing it was just one night in a cave, a feat most young people would survive, Yagno believed that Zhakata had protected him from the monsters of the woods.

Like a true zealot, Yagno didn’t bother to look into this deity of his or the source of the word “Zhakata” (a code word used between two Vistani), he set up an altar to Zhakata in the cave. And, naturally, decided that Zhakata required ritual sacrifices.

He sacrificed a number of servants and family members, Yoshtoi included, to this “god” of his. Eventually, he was discovered in the act of sacrificing his sister’s baby. His family saved the child and chased Yagno into the woods, where he fled into the Mists and G’Henna was created.

Yagno rules G’Henna as a Theocracy, making those that dwell there worship his false god. The people of G’Henna believe Zhakata has two forms, the Devourer and the Provider, though none have ever seen the Provider. The Devourer was said to have walked the land, thinning and drying the soils, freezing the people and making the land hostile to all living things.

Having never communed with his God, Yagno is plagued with doubt in Zhakata’s existence. He hides this doubt behind religious decrees and punishes any who question his or their own faith. It is said that the Mists are the ones that grant Yagno his power. A strange sort of torment, to obtain power yet never know its source.

So powerful was his doubt that he hired a wizard to contact Zhaktat and find the Provider. The wizard ended up summoning a nalfeshnee named Malistroi who mocked Yagno and told him his god was false and never existed. Enraged, Yagno killed the wizard and left the devil bound in the wizard’s summoning circle. Yagno then told his people that there was no Provider, just the Devourer.

In a way this is true, with Yagno being the Devourer himself. His laws require that all food grown in G’Henna are offered to the church. The church pointlessly sacrifices some of this precious resource to "Zhakata" and distributes the rest to the people, barely enough to survive off of. Buying and selling food is considered a crime. Honestly, is anyone upset that the Grand Conjunction threw this Domain out into the floating pockets? No, I only continually get blamed for the less desirable changes.

Yagno’s real power comes from the altar within his grand cathedral that towers over the city of Zhukar. There he can charm the masses as if using a charm spell himself. He can also transform any native G’Henna into a beastial humanoid. These transformations are used quite often on those whom Yagno views as transgressing against him, though they only work on those that believe in Zhakata. In making these transformations, he is simply destroying his own followers. Quite simply put, Yagno is nothing more than a fool's ouroboros.

#Yagno Petrovna#G'henna#azalin#azalin rex#ravenloft#darklordreviews#5e pretty much kept this the same#surprisingly#but its just got a paragraph in vrgtr so i'm not including it

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have talked about this before, but the effect that D&D 3e had on RPGs as a whole cannot be overstated. The structure of D&D 3e is of course alive in D&D 5e but also Pathfinder 2e, but so many games to this day owe so much to D&D 3e. Fantasy AGE has levels, a separation between "skills" and "talents" as meaningful categories with separate pools of resources being used to buy those things, and it's a game concerned with providing players with balanced combat encounters. It's a D&D 3e ass game. Even WFRP and the Fantasy Flight Star Wars games (and thus Genesys as a whole) have not survived untouched by 3e.

And that's important when looking at games because a lot of the time when you look under the hood of a new game that is supposedly about kissing elves you find that it's actually D&D 3e with an elf-kissing minigame. Sure, it's fun that there's an elf-kissing minigame, but the core gameplay is still very much about killing monsters in balanced combat encounters in order to grow mainly in combat power.

448 notes

·

View notes

Text

Digital Product Passport Market: Impact on Circular Economy Initiatives

The global digital product passport market size was valued at USD 213.9 million in 2024 and is expected to expand at a CAGR of 34.9%��from 2025 to 2030. This growth is primarily driven by the increasing global demand for product transparency, sustainable manufacturing practices, and circular economy solutions.

Companies across various industries are adopting DPP systems to track and share detailed product information, including material sources, environmental impact, and end-of-life options. This trend is supported by rising consumer awareness, investor pressure regarding environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance, and the need for businesses to optimize resource use and minimize waste.

Furthermore, consumers are giving more priority to eco-products and demanding rich information regarding sourcing and sustainability about products. Consumers' new perceptions are nudging businesses towards taking up DPPs as a means of creating brand trust and fulfilling market needs. One of the key trends in the worldwide DPP market is the adoption of innovative technologies such as blockchain, the Internet of Things (IoT), and Artificial Intelligence (AI), which enhance the scalability and efficiency of DPP deployments. Blockchain technology provides secure and unalterable product information tracking across supply chains, while IoT sensors enable real-time monitoring of product conditions. AI is increasingly used to process lifecycle data, forecast product behaviour, and automate compliance procedures. Such technologies are evolving DPPs from passive tracking systems to active systems that are capable of monitoring supply chain activities and disruptions and hence improving operating efficiency and sustainability performance.

Key Companies profiled:

• 3E • Avery Dennison • Billon Group • Circularise • CIRPASS • Det Norske Veritas Group (DNV) • iPoint-systems GmbH • Kezzler • LyondellBasell Industries Holdings B.V. • OPTEL GROUP • Sigma Technology

Key Digital Product Passport Company Insights

Some of the key players operating in the market are SIEMENS, 3E, Avery Dennison, Billon Group, among others.

• 3E is an environmental, health, and safety (EHS) compliance solutions provider that specializes in data services supporting manufacturers in managing chemical and material data. For DPP, 3E's platforms help businesses accumulate and store mandatory data attributes such as substance declarations, regulatory flags (e.g., REACH, RoHS), and safety data. Such datasets are critical inputs for businesses in electronics, packaging, and chemical industries trying to meet upcoming digital passport regulations.

• Avery Dennison focuses on labelling technologies, smart packaging, and digital identification systems. It supplies RFID labels, QR code technologies, and traceability platforms in the cloud that enable physical products to be connected with digital records. For applications related to DPP, Avery Dennison solutions enable brands to store and transmit rich product information such as composition, origin, and recyclability. Its solutions are commonly applied in apparel, logistics, and consumer goods industries where product traceability is becoming increasingly important from a regulatory perspective.

• Billon Group creates secure digital identity, data transfer, and document storage technologies on the blockchain. Its solution is engineered to enable immutable and decentralized storage of structured data, such as those required for DPP frameworks. Billon's architecture enables permissioned sharing of data, version control, and compliance auditing, especially applicable to firms with intricate cross-border supply chains and companies handling sensitive material declarations or supplier information

Order a free sample PDF of the Digital Product Passport Market Intelligence Study, published by Grand View Research.

Recent Developments

• In February 2025, Victoria's Secret & Co. rolled out its initial batch of Digital Product Passports (DPPs) across several collections such as the Signature Cotton T-shirt Bra and the VSX Featherweight Max Sports Bra. Each passport, available through QR code on the product label, gives consumers detailed product information, such as fabric makeup, transparency around sourcing, manufacturing partners, and environmental impact metrics. The DPP implementation is just one aspect of Victoria's Secret's overall focus on sustainability and responsible production practices, designed to increase traceability and customer involvement.

• In January 2025, Madaster launched its own Digital Product Passport (DPP) platform specifically designed for the construction and manufacturing industries. The system collects and deals with detailed information on product material composition, embodied carbon, reusability potential, and end-of-life disposition. Intended to assist firms in meeting soon-to-be imposed European Union circular economy regulations, the platform helps stakeholders minimize waste and maximize efficiency of resources. Madaster's DPP service highlights the change toward data-led sustainability in built environments and manufacturing.

• In June 2024, Eviden, in partnership with the IOTA Foundation, launched the Eviden Digital Passport Solution (EDPS), a turnkey Digital Product Passport solution using blockchain technology. Based on IOTA's distributed ledger technology, EDPS provides secure and tamper-proof storage of data about a product's life cycle, carbon footprint, and sustainability performance. The first application targets automotive batteries, facilitating compliance with future EU regulations as well as more general use across industries looking for traceability and ESG compliance.

#DigitalProductPassport#DPP#ProductPassport#MarketTrends#SupplyChainTransparency#ProductTraceability#Digitalization

0 notes

Text

3e: Sticks and Stones

ALright I’m up late and the thing I was working on didn’t work and I don’t want to fall behind on my schedule so let’s just belt out something about the ongoing grievance I have in how 3rd edition D&D treated spellcasters as a better class of people with their own higher standard of living because being able to rewrite reality at will is by no means a perk enough to justify not feeling bummed out.

Let me talk to you about sticks and stones powers.

First the origin of the term. The psionics system of 3rd edition was a beautiful beast and also a complete functional failure. Its presence was demanded implicitly by being a thing that existed in 2ed and people liked, while its exclusion from the core of content was demanded explicitly by being a thing that existed in 2ed and people hated. It was a sci-fi thing, unlike the flying airships and unsupported towers made of glass that the rest of the fantasy genre had going on inside it. The psionic system has two distinct forms; the version that launched in 3rd edition proper, and the followup version in 3.5.

3rd editions’ psionic system had a lot of things in it to try and make sense of things that seemed like they should exist in a story, which included an idea of psychic combat. That was where two psychic characters could give up their actions to tangle with one another in a sequence of paper-rock-scissors-laser-godzilla in an attempt to determine who had the bigger brain, who had dedicated the right resources to it, and crucially, who hadn’t decided to spend a few turns using their actual powers to do actual damage or inflict control. Seriously, psychic combat was a hilarious system because it was only useful for psychics who both wanted to fight one another and deplete each other’s power points. Just using powers on one another, like by say, using psychic powers to bombard the other person with lasers? A lot more effective. But don’t worry, there was also the silliness of psychic combat folding in the Illithid power Mind Blast which is a cone stun that lasts for 1d4+1 rounds, aka ‘probably enough to kill anyone or get away from anyone.’

Yeah, player characters could have Mind Blast, at a certain level. It was the only thing anyone ever bothered with in that system.

Along with that system was a collection of psionic powers that all relied on different stats to make sure the spellcaster had to feel rounded. They then could use these well rounded stats to cast psionic powers which were quite mediocre compared to magical spells of their level, and also because of those rounded stats, likely to fail. The entire system was built on ‘hey, here are nice ideas, why don’t we do this’ and the answer coming out pretty evidently in the first playtest.

Anyway, in the Expanded Psionics Handbook in 3.5, Expanded from the Latin meaning ‘not a pig’s arse’, the rulebook decided to instead make the psychic spellcasters into what they always were: spellcasters. Spellcasters needed things like a familiar stat structure, feat support, prestige classes that advanced spellcasting, powers that scaled, and of course, eventually, as with so many things in 3rd edition D&D, gear support.

The Expanded Psionics Handbook introduced the power stone and the dorje. A power stone is an item that has a single use application of a power in it, imbued by the caster at some point. If you can manifest the power in the stone, you can use the power stone. A dorje is a power stone, but a little waggly stick. The waggly stick could have lots of charges stored in it. That is to say, power stones and dorjes are fundamentally, scrolls and wands, as every other spellcaster in the core rules had at the start of the edition.

All psionic manifesters had a limited pool of spells – sorry, powers – they could cast – sorry, manifest. Anyway, these spellcasters were like sorcerers, who could only cast a few spells and that meant that these items that expanded your available spells were super useful. This also meant there were spells you didn’t necessarly want to know wth your limited choices, but you could spend some of your gold to expand on that. Spells cast out of dorjes and power crystals were cast as weak as they could be – minimum caster level, minimum stat, so for a 1st level power, it would be the duration, range, and effect of a level 1 caster’s version, and the difficulty class to use it would be a dc 10. Not great stuff for offensive powers, you want to be able to put oomph behind those yourself.

But say, Comprehend Languages? Or Knock? or Object Reading? Spells that just give you information and aren’t cast under time pressure for combat? Nobody cares about the difficulty of those. You might as well have those in these convenient forms and never bother learning them for yourself. In the process this creates the vision of a marketplace supplied by the small number of psions who do actually know those powers and learned them entirely to supply everyone else with them through dorjes and power stones, which is, at the least, a little funny.

This led to the term ‘sticks and stones’ powers; powers you didn’t need or care about in most situations but you’d stick some of them in your backpack for convenience when you needed them later. This meant that over time, psionic characters would have a swiss army knife of toys for every out-of-combat situation and it was for a time, criticised.

It was criticised, because it was encroaching on the wizard.

Yes, that’s right we’re back there! We’re back at it! Becuase the problem as described was the problem of one character having too much versatility, and in 3rd edition design, the character who had too much versatility was the wizard’s niche. Wizards had been crafting spells into spellbooks and onto scrolls at the end of every day since day one of 3rd edition. They even got the feat to do it for free! Their spellbook was the biggest, and had the most weird niche things! The game even had rules for wizards that pointed out how sensible it was for a wizard to develop their own unique versions of existing spells!

The whole point of stick-and-stones powers is that the powers systems had things that existed in two non-overlapping fields of play, and then expected you to spend the same limited pool resources between them equally even though one of them could get you shanked by a drunken gnoll.

Check it out on PRESS.exe to see it with images and links!

32 notes

·

View notes