#AI Face Recognition

Text

Artificial Intelligence-Based Face Recognition

Current technology astounds people with incredible innovations that not only make life easier but also more pleasant. Face recognition has consistently shown to be the least intrusive and fastest form of biometric verification. To validate one's identification, the software compares a live image to a previously stored facial print using deep learning techniques. This technology's foundation is built around image processing and machine learning. Face recognition has gained significant interest from researchers as a result of human activity in many security applications such as airports, criminal detection, face tracking, forensics, and so on. Face biometrics, unlike palm prints, iris scans, fingerprints, and so on, can be non-intrusive.

They can be captured without the user's knowledge and then used for security-related applications such as criminal detection, face tracking, airport security, and forensic surveillance systems. Face recognition is extracting facial images from a video or surveillance camera. They are compared to the stored database. Face recognition entails training known photos, categorizing them with known classes, and then storing them in a database. When a test image is sent to the system, it is classed and compared to the stored database.

Face recognition

Face recognition with Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a computer vision technique that identifies a person or object in an image or video. It employs a combination of deep learning, computer vision algorithms, and image processing. These technologies allow a system to detect, recognize, and validate faces in digital photos or videos.

The technology has grown in popularity across a wide range of applications, including smartphone unlocking, door unlocking, passport verification, security systems, medical applications, and so on. Some models can recognize emotions through facial expressions.

Difference between Face recognition & Face detection

Face recognition is the act of identifying a person from an image or video stream, whereas face detection is the process of finding a face within an image or video feed. Face recognition is the process of recognizing and distinguishing people based on their facial characteristics. It uses more advanced processing techniques to determine a person's identity using feature point extraction and comparison algorithms. and can be employed in applications such as automatic attendance systems or security screenings. While face detection is a considerably easier procedure, it can be utilized for applications such as image labeling or changing the angle of a shot based on the recognized face. It is the first phase in the face recognition process and is a simpler method for identifying a face in an image or video feed.

Image Processing and Machine learning

Computer Vision is the process of processing images using computers. It focuses on a high-level understanding of digital images or movies. The requirement is to automate operations that human visual systems can complete. so, a computer should be able to distinguish items like a human face, a lamppost, or even a statue.

OpenCV is a Python package created to handle computer vision problems. OpenCV was developed by Intel in 1999 and later sponsored by Willow Garage.

Machine learning

Every Machine Learning algorithm accepts a dataset as input and learns from it, which essentially implies that the algorithm is learned from the input and output data. It recognizes patterns in the input and generates the desired algorithm. For example, to determine whose face is present in a given photograph, various factors might be considered as a pattern:

The facial height and width.

Height and width measurements may be unreliable since the image could be rescaled to a smaller face or grid. However, even after rescaling, the ratios stay unchanged: the ratio of the face's height to its width will not alter.

Color of the face.

Width of other elements of the face, such as the nose, etc

There is a pattern: different faces, such as those seen above, have varied dimensions. comparable faces share comparable dimensions. Machine Learning algorithms can only grasp numbers, making the task difficult. This numerical representation of a "face" (or an element from the training set) is known as a feature vector. A feature vector is made up of various numbers arranged in a specified order.

As a simple example, we can map a "face" into a feature vector that can contain multiple features such as:

Height of the face (in cm)

Width of the face in centimeters

Average hue of the face (R, G, B).

Lip width (centimeters)

Height of the nose (cm)

Essentially, given a picture, we may turn it into a feature vector as follows:

Height of the face (in cm) Width of the face in centimeters Average hue of the face (RGB). Lip width (centimeters) Height of the nose (cm)

There could be numerous other features obtained from the photograph, such as hair color, facial hair, spectacles, and so on.

1. Face recognition technology relies on machine learning for two primary functions. These are listed below.

Deriving the feature vector: It is impossible to manually enumerate all of the features because there are so many. Many of these features can be intelligently labeled by a machine learning system. For example, a complicated feature could be the ratio of nose height to forehead width.

2. Matching algorithms: Once the feature vectors have been produced, a Machine Learning algorithm must match a new image to the collection of feature vectors included in the corpus.

3. Face Recognition Operations

Face Recognition Operations

Facial recognition technology may differ depending on the system. Different software uses various ways and means to achieve face recognition. The stepwise procedure is as follows:

Face Detection: To begin, the camera will detect and identify a face. The face is best recognized when the subject looks squarely at the camera, as this allows for easy facial identification. With technological improvements, this has advanced to the point that the face may be identified with a minor difference in posture when facing the camera.

Face Analysis: A snapshot of the face is taken and evaluated. Most facial recognition uses 2D photos rather than 3D since they are easier to compare to a database. Facial recognition software measures the distance between your eyes and the curve of your cheekbones.

Image to Data Conversion: The face traits are now transformed to a mathematical formula and represented as integers. This numerical code is referred to as a face print. Every person has a unique fingerprint, just as they all have a distinct face print.

Match Finding: Next, the code is compared to a database of other face prints. This database contains photographs with identification that may be compared. The system then finds a match for your specific features in the database. It returns a match with connected information such as a name and address, or it depends on the information kept in an individual's database.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the evolution of facial recognition technology powered by artificial intelligence has paved the way for ground breaking innovations in various industries. From enhancing security measures to enabling seamless user experiences, AI-based face recognition has proven to be a versatile and invaluable tool.

#ai face identification#ai face match#ai face recognition#ai face recognition online#ai and facial recognition

0 notes

Text

AI Solution Provider – Building a Personalized Business Roadmap with MSPs

AI Solution Provider – Building a Personalized Business Roadmap with MSPs

Managed Service Providers (MSPs) are emerging as strategic and reliable partners for global industries to automate their workflow as well as other critical responsibilities. They leverage Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology to enable businesses to avail a competitive edge in the marketplace while ensuring improved customer services. While MSPs strive to enhance their operations to better…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

Tektronix Technologies face recognition technology provides guests with perfection much advanced than the mortal eye, supports multiple attributes, periods, and complicated surroundings, and is able of producing results stationed on pall, edge, or bedded including unleashing smartphone bias, access control, furnishing accurate, fast and largely effective results to diligence.

face recognition technology abu dhabi , face recognition devcie in abu dhabi , face recognition device sharjah , facial recognition device in ajman , facial recognition device price , facial recognition device price abu dhabi , facial recognition device price alain , facial recognition device price oman , facial recognition device price qator , facial recognition device price in uae , facial recognition device sharjah

Facial recognition system , Facial recognition system abu dhabi , Facial recognition system in alain , Facial recognition system oman , Facial recognition system qator facial recognition devices abu dhabi , facial recognition devices sharjah ,Face Recognition System in Al Ain , Face Recognition System in Al Ain

#Face Recognition Solution-Tektronix Technologies uae#face recoganization solutions in abu dhabi#facial recognition abu dhabi#facial recognition device#facial recognition device uae#facial recognition device in sharjah#facial recognition device in ajman#facial recognition device in bur dubai#facial recognition device in alain#facial recognition device abu dhabi#ai face recognition#ai companies in abu dhabi#ai solutions in bur dubai#facial recognition software uae#facial recognition software abu dhabi#facial recognition software in bur dubai#facial recognition software in sharjah#facial recognition software in uae#facial recognition softwares

0 notes

Text

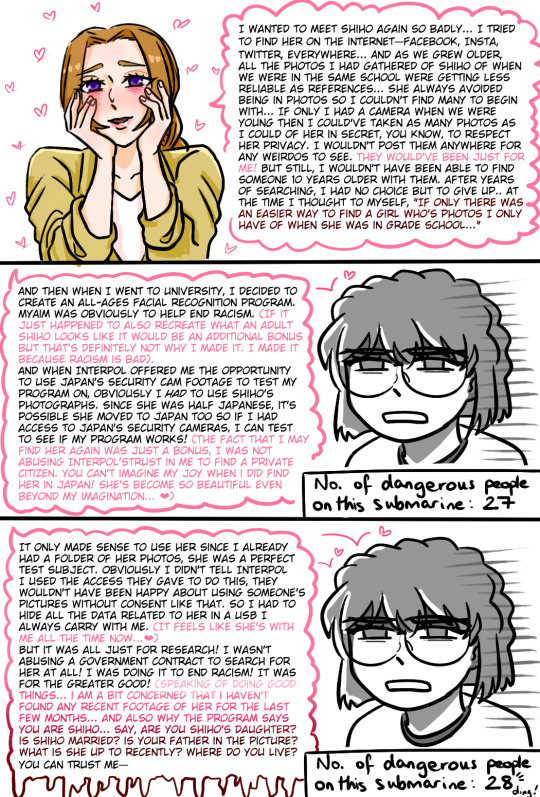

watched m26 hehe, sorry for the word vomit

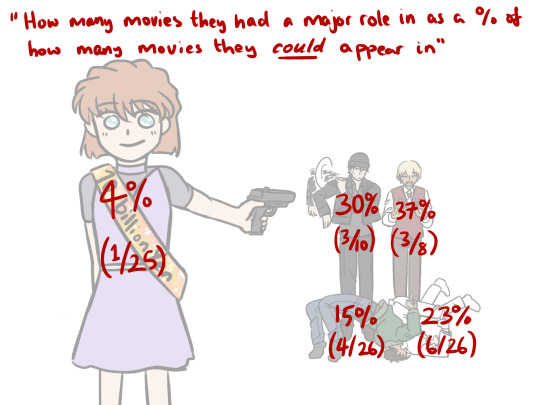

if anyone was wondering how i was counting how many movies they appeared in, i made a little timeline when i was trying to figure it out for myself ↓

all dcmk movies are released on golden week which is in april. shout out to the detectiveconanworld wiki i couldn't have done it without you x

the real enemy is conan because he's got a perfect 100% movie spotlight

#dcmk#detective conan#m26 spoilers#haibara ai#i'm not tagging all of them#m5 2001 -> 9/11; m26 2023 -> submarine explodes#2/26 (7.7%) means dcmk movies have predicted the future more times than ai has had a spotlight in a movie#bets on next conan movie to predict the future#hmmm i think i'm gonna make a poll for M28 brb#i don't really understand how naomi thought an all ages face recognition software would help get rid of racism...#but she went ahead and used it to find her childhood crush so i support her ❤#my art

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

welcome to dystopia

#ai#artificial intelligence#face recognition#journalism#dystopian society#boring dystopia#a boring dystopia#dystopia#dystopian#china#wtf#totalitarianism

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Named Manifesto Collection, the clothing features various patterns developed by artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to shield the wearer's facial identity and instead identify them as animals."

"The collection includes jumpers, t-shirts, trousers and dresses that are knitted from 100 per cent Egyptian cotton quality by Filmar, a brand that adheres to the Better Cotton Initiative (BCI), according to Cap_able.

According to Didero, the Manifesto Collection aims to raise awareness of the right to biometric data privacy, which is an issue she says that is "often underrepresented despite affecting the majority of citizens around the world"."

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reject #ClearviewCopOut Settlement

Clearview AI, the notorious facial recognition company, is poised to settle a lawsuit that includes virtually everyone—including you.

If you’ve been on social media between 2017 and now, you are most likely involved in this case, and you can help make sure Clearview doesn't get off easy. Take action now and reject this Clearview settlement and opt out.

Here's the background: since 2017 Clearview has scraped billions of images from websites and created a massive database with our photos.2 This database uses facial recognition technology to identify people, and has been sold to many clients, including cops.

Clearview has been sued many times for its attack on our rights, and several of these cases joined together in a consolidated class action lawsuit out of Illinois. Clearview is now set to settle this case, but this settlement doesn’t offer the protection our community deserves and allows Clearview to continue with business as usual: selling our faces in exchange for a payout that could be as little as pennies.

We’re calling this settlement for what it is: a cop out instead of real changes to their shady business practices. You can help fight this cop out by opting out of the settlement deal. Here is a website where you can easily go through the steps to opt out.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Starting reading the AI Snake Oil book online today

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/starting-reading-the-ai-snake-oil-book-online-today/

Starting reading the AI Snake Oil book online today

The first chapter of the AI snake oil book is now available online. It is 30 pages long and summarizes the book’s main arguments. If you start reading now, you won’t have to wait long for the rest of the book — it will be published on the 24th of September. If you haven’t pre-ordered it yet, we hope that reading the introductory chapter will convince you to get yourself a copy.

We were fortunate to receive positive early reviews by The New Yorker, Publishers’ Weekly (featured in the Top 10 science books for Fall 2024), and many other outlets. We’re hosting virtual book events (City Lights, Princeton Public Library, Princeton alumni events), and have appeared on many podcasts to talk about the book (including Machine Learning Street Talk, 20VC, Scaling Theory).

Our book is about demystifying AI, so right out of the gate we address what we think is the single most confusing thing about it:

AI is an umbrella term for a set of loosely related technologies

Because AI is an umbrella term, we treat each type of AI differently. We have chapters on predictive AI, generative AI, as well as AI used for social media content moderation. We also have a chapter on whether AI is an existential risk. We conclude with a discussion of why AI snake oil persists and what the future might hold. By AI snake oil we mean AI applications that do not (and perhaps cannot) work. Our book is a guide to identifying AI snake oil and AI hype. We also look at AI that is harmful even if it works well — such as face recognition used for mass surveillance.

While the book is meant for a broad audience, it does not simply rehash the arguments we have made in our papers or on this newsletter. We make scholarly contributions and we wrote the book to be suitable for adoption in courses. We will soon release exercises and class discussion questions to accompany the book.

Chapter 1: Introduction. We begin with a summary of our main arguments in the book. We discuss the definition of AI (and more importantly, why it is hard to come up with one), how AI is an umbrella term, what we mean by AI Snake Oil, and who the book is for.

Generative AI has made huge strides in the last decade. On the other hand, predictive AI is used for predicting outcomes to make consequential decisions in hiring, banking, insurance, education, and more. While predictive AI can find broad statistical patterns in data, it is marketed as far more than that, leading to major real-world misfires. Finally, we discuss the benefits and limitations of AI for content moderation on social media.

We also tell the story of what led the two of us to write the book. The entire first chapter is now available online.

Chapter 2: How predictive AI goes wrong. Predictive AI is used to make predictions about people—will a defendant fail to show up for trial? Is a patient at high risk of negative health outcomes? Will a student drop out of college? These predictions are then used to make consequential decisions. Developers claim predictive AI is groundbreaking, but in reality it suffers from a number of shortcomings that are hard to fix.

We have discussed the failures of predictive AI in this blog. But in the book, we go much deeper through case studies to show how predictive AI fails to live up to the promises made by its developers.

Chapter 3: Can AI predict the future? Are the shortcomings of predictive AI inherent, or can they be resolved? In this chapter, we look at why predicting the future is hard — with or without AI. While we have made consistent progress in some domains such as weather prediction, we argue that this progress cannot translate to other settings, such as individuals’ life outcomes, the success of cultural products like books and movies, or pandemics.

Since much of our newsletter is focused on topics of current interest, this is a topic that we have never written about here. Yet, it is foundational knowledge that can help you build intuition around when we should expect predictions to be accurate.

Chapter 4: The long road to generative AI. Recent advances in generative AI can seem sudden, but they build on a series of improvements over seven decades. In this chapter, we retrace the history of computing advances that led to generative AI. While we have written a lot about current trends in generative AI, in the book, we look at its past. This is crucial for understanding what to expect in the future.

Chapter 5: Is advanced AI an existential threat? Claims about AI wiping out humanity are common. Here, we critically evaluate claims about AI’s existential risk and find several shortcomings and fallacies in popular discussion of x-risk. We discuss approaches to defending against AI risks that improve societal resilience regardless of the threat of advanced AI.

Chapter 6: Why can’t AI fix social media? One area where AI is heavily used is content moderation on social media platforms. We discuss the current state of AI use on social media, and highlight seven reasons why improvements in AI alone are unlikely to solve platforms’ content moderation woes. We haven’t written about content moderation in this newsletter.

Chapter 7: Why do myths about AI persist? Companies, researchers, and journalists all contribute to AI hype. We discuss how myths about AI are created and how they persist. In the process, we hope to give you the tools to read AI news with the appropriate skepticism and identify attempts to sell you snake oil.

Chapter 8: Where do we go from here? While the previous chapter focuses on the supply of snake oil, in the last chapter, we look at where the demand for AI snake oil comes from. We also look at the impact of AI on the future of work, the role and limitations of regulation, and conclude with vignettes of the many possible futures ahead of us. We have the agency to determine which path we end up on, and each of us can play a role.

We hope you will find the book useful and look forward to hearing what you think.

The New Yorker: “In AI Snake Oil, Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor urge skepticism and argue that the blanket term AI can serve as a smokescreen for underperforming technologies.”

Kirkus: “Highly useful advice for those who work with or are affected by AI—i.e., nearly everyone.”

Publishers’ Weekly: Featured in the Fall 2024 list of top science books.

Jean Gazis: “The authors admirably differentiate fact from opinion, draw from personal experience, give sensible reasons for their views (including copious references), and don’t hesitate to call for action. . . . If you’re curious about AI or deciding how to implement it, AI Snake Oil offers clear writing and level-headed thinking.”

Elizabeth Quill: “A worthwhile read whether you make policy decisions, use AI in the workplace or just spend time searching online. It’s a powerful reminder of how AI has already infiltrated our lives — and a convincing plea to take care in how we interact with it.”

We’ve been on many other podcasts that will air around the time of the book’s release, and we will keep this list updated.

The book is available to preorder internationally on Amazon.

#2024#adoption#Advice#ai#ai news#air#Amazon#applications#banking#Blog#book#Books#college#Companies#computing#content#content moderation#courses#data#developers#domains#education#Events#face recognition#Featured#Future#future of work#GATE#generative#generative ai

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

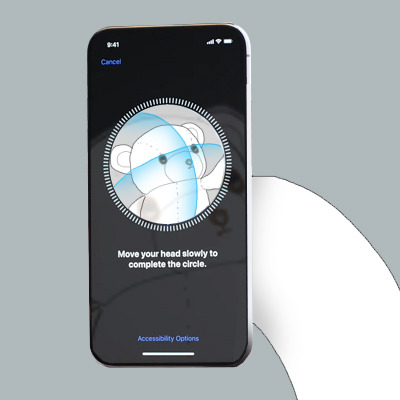

Behbeh

#apple#apple iphone#iphone#face id#ai#facial recognition#non discriminatory#new iOS#iOS#technology#big brother#mac#cartoon#teddy bear#illustration#dailybehbeh#behbeh#cute#stuffed animal#art#funny#comedy

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Book Review

"If you're not paying for it, you're the product."

Your Face Belongs to Us is a terrifying yet interesting journey through the world of invasive surveillance, artificial intelligence, facial recognition, and biometric data collection by way of the birth and rise of a company called Clearview AI — a software used by law enforcement and government agencies in the US yet banned in various countries. A database of 75 million images per day.

The writing is easy flowing investigative journalism, but the information (as expected) is...chile 👀. Lawsuits and court cases to boot. This book reads somewhat like one of my favorite books of all-time, How Music Got Free by Stephen Witt (my review's here), in which it delves into the history from birth to present while learning the key players along the way.

Here's an excerpt that keeps you seated for this wild ride:

“I was in a hotel room in Switzerland, six months pregnant, when I got the email. It was the end of a long day and I was tired but the email gave me a jolt. My source had unearthed a legal memo marked “Privileged & Confidential” in which a lawyer for Clearview had said that the company had scraped billions of photos from the public web, including social media sites such as Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn, to create a revolutionary app. Give Clearview a photo of a random person on the street, and it would spit back all the places on the internet where it had spotted their face, potentially revealing not just their name but other personal details about their life. The company was selling this superpower to police departments around the country but trying to keep its existence a secret.”

#your face belongs to us#kashmir hill#thechanelmuse reviews#book recommendations#articifial intelligence#facial recognition#hoan ton that#clearview ai

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 5 Use Cases of AI Face Recognition Technology in 2023

Top 5 Use Cases of AI Face Recognition Technology in 2023

Technological innovation has facilitated the growth of the corporate sector, but it has enabled fraudsters to exploit industries for personal gains. In this light, business experts want to implement innovative digital solutions to discourage fraud attempts and enhance protection. The application of face recognition solutions can help the sector in achieving its milestones. Moreover, using…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The first time Karl Ricanek was stopped by police for “driving while Black” was in the summer of 1995. He was twenty-five and had just qualified as an engineer and started work at the US Department of Defense’s Naval Undersea Warfare Center in Newport, Rhode Island, a wealthy town known for its spectacular cliff walks and millionaires’ mansions. That summer, he had bought his first nice car—a two-year-old dark green Infiniti J30T that cost him roughly $30,000 (US).

One evening, on his way back to the place he rented in First Beach, a police car pulled him over. Karl was polite, distant, knowing not to seem combative or aggressive. He knew, too, to keep his hands in visible places and what could happen if he didn’t. It was something he’d been trained to do from a young age.

The cop asked Karl his name, which he told him, even though he didn’t have to. He was well aware that if he wanted to get out of this thing, he had to cooperate. He felt at that moment he had been stripped of any rights, but he knew this was what he—and thousands of others like him—had to live with. This is a nice car, the cop told Karl. How do you afford a fancy car like this?

What do you mean? Karl thought furiously. None of your business how I afford this car. Instead, he said, “Well, I’m an engineer. I work over at the research centre. I bought the car with my wages.”

That wasn’t the last time Karl was pulled over by a cop. In fact, it wasn’t even the last time in Newport. And when friends and colleagues shrugged, telling him that getting stopped and being asked some questions didn’t sound like a big deal, he let it lie. But they had never been stopped simply for “driving while white”; they hadn’t been subjected to the humiliation of being questioned as law-abiding adults, purely based on their visual identity; they didn’t have to justify their presence and their choices to strangers and be afraid for their lives if they resisted.

Karl had never broken the law. He’d worked as hard as anybody else, doing all the things that bright young people were supposed to do in America. So why, he thought, can’t I just be left alone?

Karl grew up with four older siblings in Deanwood, a primarily Black neighbourhood in the northeastern corner of Washington, DC, with a white German father and a Black mother. When he left Washington, DC, at eighteen for college, he had a scholarship to study at North Carolina A&T State University, which graduates the largest numbers of Black engineers in the US. It was where Karl learned to address problems with technical solutions, rather than social ones. He taught himself to emphasize his academic credentials and underplay his background so he would be taken more seriously amongst peers.

After working in Newport, Karl went into academia, at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington. In particular, he was interested in teaching computers to identify faces even better than humans do. His goal seemed simple: first, unpick how humans see faces, and then teach computers how to do it more efficiently.

When he started out back in the ’80s and ’90s, Karl was developing AI technology to help the US Navy’s submarine fleet navigate autonomously. At the time, computer vision was a slow-moving field, in which machines were merely taught to recognize objects rather than people’s identities. The technology was nascent—and pretty terrible. The algorithms he designed were trying to get the machine to say: that’s a bottle, these are glasses, this is a table, these are humans. Each year, they made incremental, single-digit improvements in precision.

Then, a new type of AI known as deep learning emerged—the same discipline that allowed miscreants to generate sexually deviant deepfakes of Helen Mort and Noelle Martin, and the model that underpins ChatGPT. The cutting-edge technology was helped along by an embarrassment of data riches—in this case, millions of photos uploaded to the web that could be used to train new image recognition algorithms.

Deep learning catapulted the small gains Karl was seeing into real progress. All of a sudden, what used to be a 1 percent improvement was now 10 percent each year. It meant software could now be used not just to classify objects but to recognize unique faces.

When Karl first started working on the problem of facial recognition, it wasn’t supposed to be used live on protesters or pedestrians or ordinary people. It was supposed to be a photo analysis tool. From its inception in the ’90s, researchers knew there were biases and inaccuracies in how the algorithms worked. But they hadn’t quite figured out why.

The biometrics community viewed the problems as academic—an interesting computer-vision challenge affecting a prototype still in its infancy. They broadly agreed that the technology wasn’t ready for prime-time use, and they had no plans to profit from it.

As the technology steadily improved, Karl began to develop experimental AI analytics models to spot physical signs of illnesses like cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s, or Parkinson’s from a person’s face. For instance, a common symptom of Parkinson’s is frozen or stiff facial expressions, brought on by changes in the face’s muscles. AI technology could be used to analyse these micro muscular changes and detect the onset of disease early. He told me he imagined inventing a mirror that you could look at each morning that would tell you (or notify a trusted person) if you were developing symptoms of degenerative neurological disease. He founded a for-profit company, Lapetus Solutions, which predicted life expectancy through facial analytics, for the insurance market.

His systems were used by law enforcement to identify trafficked children and notorious criminal gangsters such as Whitey Bulger. He even looked into identifying faces of those who had changed genders, by testing his systems on videos of transsexual people undergoing hormonal transitions, an extremely controversial use of the technology. He became fixated on the mysteries locked up in the human face, regardless of any harms or negative consequences.

In the US, it was 9/11 that, quite literally overnight, ramped up the administration’s urgent need for surveillance technologies like face recognition, supercharging investment in and development of these systems. The issue was no longer merely academic, and within a few years, the US government had built vast databases containing the faces and other biometric data of millions of Iraqis, Afghans, and US tourists from around the world. They invested heavily in commercializing biometric research like Karl’s; he received military funding to improve facial recognition algorithms, working on systems to recognize obscured and masked faces, young faces, and faces as they aged. American domestic law enforcement adapted counterterrorism technology, including facial recognition, to police street crime, gang violence, and even civil rights protests.

It became harder for Karl to ignore what AI facial analytics was now being developed for. Yet, during those years, he resisted critique of the social impacts of the powerful technology he was helping create. He rarely sat on ethics or standards boards at his university, because he thought they were bureaucratic and time consuming. He described critics of facial recognition as “social justice warriors” who didn’t have practical experience of building this technology themselves. As far as he was concerned, he was creating tools to help save children and find terrorists, and everything else was just noise.

But it wasn’t that straightforward. Technology companies, both large and small, had access to far more face data and had a commercial imperative to push forward facial recognition. Corporate giants such as Meta and Chinese-owned TikTok, and start-ups like New York–based Clearview AI and Russia’s NTech Labs, own even larger databases of faces than many governments do—and certainly more than researchers like Karl do. And they’re all driven by the same incentive: making money.

These private actors soon uprooted systems from academic institutions like Karl’s and started selling immature facial recognition solutions to law enforcement, intelligence agencies, governments, and private entities around the world. In January 2020, the New York Times published a story about how Clearview AI had taken billions of photos from the web, including sites like LinkedIn and Instagram, to build powerful facial recognition capabilities bought by several police forces around the world.

The technology was being unleashed from Argentina to Alabama with a life of its own, blowing wild like gleeful dandelion seeds taking root at will. In Uganda, Hong Kong, and India, it has been used to stifle political opposition and civil protest. In the US, it was used to track Black Lives Matter protests and Capitol rioters during the uprising in January 2021, and in London to monitor revellers at the annual Afro-Caribbean carnival in Notting Hill.

And it’s not just a law enforcement tool: facial recognition is being used to catch pickpockets and petty thieves. It is deployed at the famous Gordon’s Wine Bar in London, scanning for known troublemakers. It’s even been used to identify dead Russian soldiers in Ukraine. The question whether it was ready for prime-time use has taken on an urgency as it impacts the lives of billions around the world.

Karl knew the technology was not ready for widespread rollout in this way. Indeed, in 2018, Joy Buolamwini, Timnit Gebru, and Deborah Raji—three Black female researchers at Microsoft—had published a study, alongside collaborators, comparing the accuracy of face recognition systems built by IBM, Face++, and Microsoft. They found the error rates for light-skinned men hovered at less than 1 percent, while that figure touched 35 percent for darker-skinned women. Karl knew that New Jersey resident Nijer Parks spent ten days in jail in 2019 and paid several thousand dollars to defend himself against accusations of shoplifting and assault of a police officer in Woodbridge, New Jersey.

The thirty-three-year-old Black man had been misidentified by a facial recognition system used by the Woodbridge police. The case was dismissed a year later for lack of evidence, and Parks later sued the police for violation of his civil rights.

A year after that, Robert Julian-Borchak Williams, a Detroit resident and father of two, was arrested for a shoplifting crime he did not commit, due to another faulty facial recognition match. The arrest took place in his front garden, in front of his family.

Facial recognition technology also led to the incorrect identification of American-born Amara Majeed as a terrorist involved in Sri Lanka’s Easter Day bombings in 2019. Majeed, a college student at the time, said the misidentification caused her and her family humiliation and pain after her relatives in Sri Lanka saw her face, unexpectedly, amongst a line-up of the accused terrorists on the evening news.

As his worlds started to collide, Karl was forced to reckon with the implications of AI-enabled surveillance—and to question his own role in it, acknowledging it could curtail the freedoms of individuals and communities going about their normal lives. “I think I used to believe that I create technology,” he told me, “and other smart people deal with policy issues. Now I have to ponder and think much deeper about what it is that I’m doing.”

And what he had thought of as technical glitches, such as algorithms working much better on Caucasian and male faces while struggling to correctly identify darker skin tones and female faces, he came to see as much more than that.

“It’s a complicated feeling. As an engineer, as a scientist, I want to build technology to do good,” he told me. “But as a human being and as a Black man, I know people are going to use technology inappropriately. I know my technology might be used against me in some manner or fashion.”

In my decade of covering the technology industry, Karl was one of the only computer scientists to ever express their moral doubts out loud to me. Through him, I glimpsed the fraught relationship that engineers can have with their own creations and the ethical ambiguities they grapple with when their personal and professional instincts collide.

He was also one of the few technologists who comprehended the implicit threats of facial recognition, particularly in policing, in a visceral way.

“The problem that we have is not the algorithms but the humans,” he insisted. When you hear about facial recognition in law enforcement going terribly wrong, it’s because of human errors, he said, referring to the over-policing of African American males and other minorities and the use of unprovoked violence by police officers against Black people like Philando Castile, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor.

He knew the technology was rife with false positives and that humans suffered from confirmation bias. So if a police officer believed someone to be guilty of a crime and the AI system confirmed it, they were likely to target innocents. “And if that person is Black, who cares?” he said.

He admitted to worrying that the inevitable false matches would result in unnecessary gun violence. He was afraid that these problems would compound the social malaise of racial or other types of profiling. Together, humans and AI could end up creating a policing system far more malignant than the one citizens have today.

“It’s the same problem that came out of the Jim Crow era of the ’60s; it was supposed to be separate but equal, which it never was; it was just separate . . . fundamentally, people don’t treat everybody the same. People make laws, and people use algorithms. At the end of the day, the computer doesn’t care.”

Excerpted from Code Dependent: Living in the Shadow of AI by Madhumita Murgia. Published by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2024 by Madhumita Murgia. All rights reserved.

#When Facial Recognition Helps Police Target Black Faces#AI#Racial Profiling#poor facial recognition software training#intentional racial training#2024 Jim Crow#policing#racism in america#electronic mistakes#policing with privilege#end qualified immunity#Fourth Amendment#american racism#systemic racism in policing

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The lyrics are the best part about the song. The way I interpret it it hits the nail on the head, the kind of future we're moving towards with advanced AI technology that's pretty much not at all regulated in any way yet.

#nemesestext#and when I think about what the EU is currently planning#to allow for AI face recognition to be a thing#it hits even harder

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

WHY Face Recognition acts racist

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Florian Freier, Machine Readable Puppenheim, 2023

2 notes

·

View notes