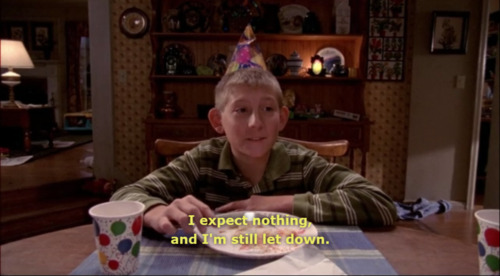

#After 1899 I am still SO bitter you have no idea

Text

Lockwood & Co. got cancelled

#Netflix cancelling shows left and right how about I cancel my subscription to follow this trend?#After 1899 I am still SO bitter you have no idea#Lockwood & Co.#Lockwood & co#🍐

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Came here through a mutual, and I'm intrigued by the fic you're writing. Any particular reason you picked Charlotte Balfour as your deuteragonist? Wonderful writing, by the way. :-)

Thank you for your kind words, and for this ask!! (Also apologizing in advance for how long this is lol, the short answer is I am so autistic about these characters /lh)

The first reason I started writing echoed fragments was because after replaying the epilogue for the second time I couldn’t stop thinking about the way Charles’ grief has so strongly changed him and is still impacting him 8 years later; I’m a Charthur truther to my core, but even in a platonic interpretation Arthur’s death (and the destruction of the gang, it wasn’t just about Arthur) was something that he hadn’t healed from all that time later.

To be someone as principled, skilled, and talented as Charles and to end up in the depths of Saint Denis, throwing street fights for money and being somewhat entangled with the mob? The way he throws himself into protecting John and Uncle when he had no real obligation to do so? That’s a man still reeling from the loss of the first community he’s let himself form a connection with since losing his family at a young age, and who possibly still feels guilty about leaving and not being there when the bitter end came, even though leaving when he did was inarguably the right thing to do.

Despite the fact that Charles cut ties and had the cleanest getaway of any of them, he *chose* to come back and faced the aftermath alone, carried Arthur across state lines to bury him, alone, and then what?? He spent the next 8 years alone? Why did he not return to the Wapiti, or if he did, why did he leave if his other option was being on his own, throwing street fights in Saint Denis, where he would have still been a wanted man??

Whatever happened to Charles between 1899 and 1907, if the end result was Uncle - of all people - hearing rumors about Charles from states away, and Uncle *of all people* deciding that Charles was in enough trouble that they needed to intervene… it couldn’t have been anything good. I wanted so badly for him to have a chance to properly grieve and actually heal, and to not be alone through that process, so I decided that if R* wasn’t going to do it then I would lol

At the same time, Charlotte is one of the characters that I absolutely love to talk about and roll around in my brain. The more I thought about Charlotte and her mission line, the more I started to realize just how much these two had in common, personality-wise and particularly in regard to their freshly acquired grief and how it left them utterly alone after their loss, since both live on the outskirts of society (albeit for very different reasons, but the end result is the same).

The difference for Charlotte is that when she was at her absolute lowest, someone stepped in and was able to pull her back onto her feet - it quite literally saved her, and she went on to live a very meaningful and fulfilling life thanks to the care and compassion that Arthur showed her.

Charles was a close friend of the man who saved her life (whom she can no longer do anything to help), PLUS that man is fresh off the type of grief she knows all too well and is still working through herself; I think that given the opportunity Charlotte would want to pay that compassion forward. In addition to being able to grieve their losses together and having someone to lean on who knows exactly what you’re going through, I also just think they would have gotten along very well if they had ever crossed paths, so I made sure they did :3

The writing itself is slow going, but I have a whole general outline for this AU that already extends past the RDR1 canon timeline - one of the core ideas I want to explore is how the ripple effects of Arthur’s actions at the end of his life (mostly following canon with some slight modifications) end up having lifelong impacts for those who survived, and Charlotte happens to be one of the early indicators of that ripple effect. By showing her how to hunt he taught her to survive, and by giving her his horse he facilitated a personal connection that Arthur himself could never have anticipated - but because of that, the impacts of Arthur’s choices continue to resonate throughout the years.

#cm answers#anon ask#i can talk about the echoedverse for hours i am thinking about it constantly#thank you again for sending this in!!#echoedverse

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! I really really like your blog and all the Dutch content, and I read your posts on Molly and Dutch and I just felt like sharing my thoughts :) If you don’t feel like it, just ignore this

I like Molly, even though I agree that she’s very much a snob and very paranoid at times.

It’s always felt very clear to me that Molly really, truly loves Dutch. And love makes you do stupid, desperate things (just look at Arthur).

Molly’s interaction with Abigail is about Dutch’s love for Molly, not the other way around. It’s Abigail saying that Dutch doesn’t love her and Molly lashing out (probably to protect herself from the truth).

This is brought up again in An Honest Mistake, when she talks to Arthur about Dutch, questioning how Dutch seems to him. When Molly says, “I really love him, you know,” Arthur averts his eyes and doesn’t look at her. I’ve always seen this as Arthur knowing Dutch doesn’t love her in the way Molly wants him to, if he loves her at all.

I’ve always seen Dutch as being kind of ahead of his time when it comes to certain progressive ideas (especially as it pertains to race), but when it comes to women, he’s very much a product of his his time. The way he talks about them and to/at them, whether it’s Molly or Abigail or Mary-Beth or Sadie, is often either dismissive or condescending.

While he doesn’t outright say it, the way he acts around the women at camp has always left me feeling like he prefers women (at least the ones he takes an actual interest in) to fit into the roles society has carved out for them; they have to be beautiful and docile and romantic-minded for him to take an interest.

You’ve said yourself, that Dutch deals with a lot of self doubt and that stems from wanting to be seen as a great and powerful man, who the people in camp can look up to, and women (especially young women) were (and to some degree stil is) seen as symbols of status. Molly is a beautiful woman from a wealthy family; she could have anyone she wanted, and she chose Dutch and ran away with him, leaving her old life behind – that’s the ultimate powermove on Dutch’s part.

I’ve always thought of Dutch as a romantic, the way he talks about love and how it’s the one thing worth living for, and I believe that he may have at some point actually loved Molly or at least convinced himself that he did, but the second he grows tired of her and realises that he doesn’t actually love her, he’s moving on to another, younger woman.

His inner romantic and his ego and need to be perceived as powerful are at odds with each other, and as the game progresses we see how his romantic and kind side wilt under the weight and pressure of his responsibilities as a leader and his need to be perceived as powerful and a great leader.

Those are my thoughts at least :)

Hello!

Thank you for the ask and the kind words! That really does mean a lot!! 💜💜💜

I am very grateful for your message, and no!!!! I don’t want to ignore it!! That wouldn’t be very fair of me, as I feel like you bring up some good points to discuss. Also, I appreciate the respect in your message and for taking the time to write so much out! I’d be happy to give you some of my time in return 🥰

(Warning: SPOILERS below)

I’m going to take your points one at a time here. So, starting with liking Molly, it’s totally fine! I don’t want to be too negative on my blog, and I don’t want people to feel like they have to think the same way I do. That wouldn’t be any fun, so it does make me happy that you can enjoy her character. I don’t want to take that away from you!! By all means, love her to your heart's content!!! ❤️

Furthermore, though I don’t personally like Molly, I don’t think she was a truly bad person. Just like every other character in the game, she had flaws and made mistakes. I primarily wish I could have gotten to know her better because she was presented during a very dark time in her life. I feel like this affected my perception of her, and I might have seen her differently, if I had gotten the chance to interact more with her character (especially outside of the RDR2 timeframe). Everybody deserves not only to love somebody, but everybody also deserves to have faith that the person they love can truthfully say the same back to them. I felt bad that Molly died such an unhappy, loveless death.

About the love Molly had for Dutch, I agree that she loved him. My point in bringing up infatuation was to primarily highlight the reason and the degree to which she honestly loved him. Did Molly love Dutch for the man he was, or for the idea of the man he was? Maybe, it was a mix? I am not sure there is enough information to give a conclusive answer to this (as I somewhat mentioned before).

To be fair, the same thing could (and should) be asked of Dutch. Did he truly love her, or did he just love the idea of having her at his side? Again, it would be fascinating to see the early part of their relationship. It would answer a LOT of questions. You mention that Dutch arguably saw Molly as a symbol of status, and I agree that it was very plausible. I think, to some degree, both Molly and Dutch saw each other as being favorable for what they represented, unfortunately.

In regard to the interaction between Molly and Abigail, I realize my response was unclear about this (that’s my bad). I'll try to write it better here, but this is really complicated to put into words! I'll do my best!!

What I said was that Molly got angry at people she “perceived” as challenging her love (this was subjective to her POV and not necessarily reflective of true reality). My original answer was not objective (nor was it meant to be - I was trying to write this part from her POV), and there are a few layers I want to analyze here. First of all, from an objective perspective, you are correct. The conversation between them was ultimately about Dutch not loving Molly the way she wanted to be loved. However, the first thing Molly did was state to Abigail that she loved Dutch. If she didn’t see this point as being in question, why did she feel the need to immediately justify it before saying anything else? To me, it seemed like she needed to actively prove that she loved him to others.

This was also seen with Karen and Arthur. The conversations with Karen were confusing because they didn’t have much context, but perhaps, that was the point - to show the extent of Molly’s paranoia (in other words, that there was no context and that she was imagining Karen to be against her out of insecurity). Molly continually complained that Karen said bad things about her, and she insisted that she not only loved Dutch, but that he loved her as well. Then, as you mention, Molly emphasized to Arthur that SHE loved Dutch (it was not directly about his love for her). Again, by constantly having to profess her feelings, it was as if she thought people were doubting her on some level.

But here is where the contradiction comes in - I believe that Molly was smart enough to know that this doubting wasn't entirely genuine. She knew it was never really her love that she should have been concerned about. Although, by focusing on herself, it was a way to deflect from her insecurity regarding Dutch and the fact that she knew, deep down, he didn’t truly love her (at least, not anymore). That’s why she got so upset when Abigail, for instance, brought this point up. As soon as the conversation shifted from Molly’s love to Dutch’s love, she lashed out and stormed away.

So, to try to summarize this all up, what I am trying to say is that Molly “perceived” challenges to her own state of emotions as a means of shifting away from her concerns about Dutch’s feelings. She knew her "perceptions" were really more like lies to herself. Molly wanted the conversation with Abigail to seem like it was about her because she felt she was more in control of that and could handle it better. From a neutral perspective, the conversation was definitely not about Molly - it was entirely about Dutch, which Molly knew (she just didn’t like Abigail directly pointing it). I hope my response makes more sense? Sorry, if I am still being confusing!

Now, as for Dutch and his progressive ideas, I think a lot of them were formed in his youth. Little information was given about his childhood, but he did seem pretty sensitive about the fact that he grew up fatherless. His dad died in the Civil War (a conflict primarily centered around the issue of slavery and states’ attitudes towards it), while fighting on the side of the Union. One reason Dutch was probably so progressive in regard to race was because of his anger over losing a parent to racially-motivated violence. Racism seemed like a waste of time and life, so he was bitter towards people who still harbored racist sentiments. He knew firsthand how destructive they could be.

Minimal insight was provided into Dutch’s relationship with his mother, other than the fact that it was quite strained and unhappy. He left home at a young age and essentially disowned her. He obviously didn’t keep in touch with her, judging that he didn’t even know she died until years after the fact. Could this have affected his attitude later in life (towards women)?

I suppose it’s possible. Maybe, Dutch would have looked better on women, had he been closer with his mother. I consider his attitude towards women as pretty average for the era. It’s not entirely fair to compare him to Arthur, who was very progressive for the time and definitely above normal standards. As you say, I think Dutch was a product of his time. In RDR2, he didn’t come across as physically abusive, nor did he overtly sexualize women. However, he did seem to expect women to act in a subordinate manner. It's not great (and I certainly do not agree with his attitude), but again, the contemporary standards in regard to gender roles did not exist in 1899.

Lastly, I COMPLETELY agree about Dutch being VERY romantic, sentimental, and idealistic. This wasn’t just limited to interpersonal relationships either - it also fit his entire perspective of America and the values he held dear. Just take a look at some of his quotes:

“The promise of this great nation - men created equal, liberal and justice for all - that might be nonsense, but it’s worth trying for. It’s worth believing in.”

And:

“If we keep on seeking, we will find freedom.”

In the beginning, he had such high hopes and strong faith that he could find a way to live free from social and legislative demands. Compare that to the end, where he started to say things like:

“You can’t fight nature. You can’t fight change.”

And:

“There ain’t no freedom for no one in this country no more.”

Dutch wanted to believe that there was a chance to live free from the threat of control, but as he started to lose people he loved and got closer to losing his own battle, he started to take on a much more cynical tone. He began to realize that his romantic notions and idealistic visions of life were not always obtainable - no matter how hard he tried to reach them - and it broke him. This change in his life outlook was kind of similar to his interpersonal relationships. When he realized they were a lot of work and not always happy/perfect, he seemed to grow frustrated. Love requires a lot of patience and energy. Despite full effort, love still does not always succeed.

Also, I just want to add that I think Dutch knew he had a problem with his pride, but he tried his best to maintain his tough, confident persona because he didn’t want to be perceived as weak. He definitely realized he messed up in putting his pride first in the end, but at that point, it was too late. Whatever was left of his idealistic aspirations in life died with Arthur up on that cliff.

Anyhow, I’ve said more than enough. I’d like to once again thank you for the ask!! I hope my response was worth the time to read and that it makes sense. Feel free to share any more thoughts you may have!!!

~ Faith 💜

#dutch van der linde#Molly o'shea#rdr2#red dead redemption 2#writing#original#Arthur morgan#Abigail marston#karen jones#civil war#quotes#rdr#red dead redemption#dutch apologist#ask#anon#anonymous#(in regard to those types of asks anyway)#htyhtiasmmsibijt#spoilers#unpopular opinion#hot take

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

fanfiction: and when he falls (chapter 3)

Fandom: Harry Potter | Fantastic Beasts

Pairing: Albus Dumbledore/Gellert Grindelwald

Characters: Albus Dumbledore, Gellert Grindelwald, Ariana Dumbledore

Rating: M

Summary: Third chapter of my Summer of 1899 Grindeldore fic.

Also available on my AO3 (see the link in my profile).

When Albus came back up the stairs, it was with a look of tired relief on his face. Ariana was trailing behind him, idly playing with what looked like a game of skill. She glanced at Gellert as she passed him on the way to her room, giving him a shy smile. Albus was beaming at him.

“Everything is alright,” he said as he closed the door behind Gellert and himself. “She just overturned her chair by accident when she got up from the table.”

“I’m glad,” Gellert replied. “It must be hard to be constantly on the lookout for your little sister ... I suppose we all remember how it was when we couldn’t control our own magic yet.”

At that, Albus gave him a very peculiar glance that made Gellert wonder if he, perhaps, couldn’t recall such a thing. Of course Mr Model Pupil would have been able to control his magic at a very early age... But when Albus spoke, it was still of his sister.

“I’m just worried Ariana might actually breach the Statute of Secrecy someday,” he confessed. “If she does, it will be my liability alone because I am the only adult in this house.” He sighed.

“But that wouldn’t be fair!” Gellert exclaimed. “It’s neither her fault nor yours she can’t control her abilities yet! You can’t always watch over her...”

“No, perhaps not,” Albus interrupted him firmly. “But I’m still the closest person to a parental figure left to her, and therefore both her well-being and her conduct are my responsibility.”

“I see your point,” Gellert admitted. “What I still don’t see is why the burden of secrecy needs to be thrust upon the parents and guardians of our kind in the first place.”

“You question the Statute of Secrecy?” Albus blinked.

“I do indeed question the Statute of Secrecy.” Gellert gazed at him levelly. Now, he thought. How Albus reacted now would decide if he could confide in him.

“But it is an ancient law of the wizarding society that was introduced for good reason!”

“For good reason at the time,”Gellert countered. “Witch-hunting is over, so the major reason why it was introduced has become void. Laws can be changed.”

“And you think you can change the Statue of Secrecy?” Albus gave him a calculating glance.

“I will abolish it,” Gellert said firmly. Albus raised both eyebrows.

“Oh, a revolutionary, are we?” he said completely unimpressed. “But how would you muster the courage to stand up against the law if you’re already afraid of a little flower?”

“I’m not afraid of a flower!” Gellert said passionately. “But I’m sick and tired of the name-calling and the derisive laughter whenever a man is thought to be in a relationship with another man. I’m sick and tired of hiding every single part of who I am in front of Muggles, whether it is this or the fact that I’m a wizard.” He lowered his voice for effect. “I want a world in which everyone is allowed to be who they are without fear of being humiliated or persecuted. A world where it is not an offence to live freely and without fear, but where it is an offence to restrain people from doing so.”

Albus didn’t respond to Gellert’s short speech at once. He only looked at him, expression unreadable. But Gellert had the impression that something in his gaze had shifted.

“That ... is quite an ambitious goal you’ve set for yourself,” Albus said at last. “I’m sure Bathilda told you that I was British Youth Representative to the Wizengamot. It’s a very ... traditional institution, I must say. The majority position there seems to be to stay out of Muggle affairs whenever possible, and of course all members are required to abide by all national and international laws of the wizarding society. I don’t see how it would be possible to convince them of your opinion, and those are only the witches and wizards of the British Isles.” He started to pace up and down in his room, lost in thought. “In fact, I’m fairly certain the Statute of Secrecy cannot be recalled unilaterally by only one party who signed it. However, I’d need to read up on that again since I never researched this specific question.”

“Oh, Albus, you’re so young and yet you already think like a politician.” Gellert smiled indulgently. “But didn’t you realise it already? I don’t want to wait and see if I can convince some old farts of something that will never have their support anyway because it’s too far out of their comfort zone.” He paused for effect, seeking Albus’s eyes. “What I want is a revolution.”

There seemed to be something about the things he said or about the way he said them that made Albus pause. Then Albus looked directly at him. There was something unsettling about Albus’s eyes; something that made Gellert’s heart skip a beat and then speed up. These bright blue eyes seemed to pierce into his very soul.

“How?”

“Beg your pardon?” Somehow Gellert’s brain seemed unable to catch up with the information from his ears.

“How?” repeated Albus. “How do you want to achieve this goal?” Almost as an afterthought, he added: “And how do you think the Hallows will help you achieve it?”

Gellert stared. Albus Dumbledore was amazing. He had realised at once that his quest for the Hallows and his aim to overthrow the Statute of Secrecy were interconnected.

Then again, he shouldn’t have expected anything less.

“Maybe it would help if you closed your mouth and then used it to utter some words,” Albus suggested dryly. “Unless, of course, this is a test whether I’m able to retrieve the answers to my questions from you via Legilimency.”

And he is a Legilimens too? Gellert felt a strange urge to get on his knees in front of Albus or do something similarly old-fashioned and ridiculous.

Finally, he thought. Finally I’ve found someone with whom I can talk, actually talk about my ideas.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I was just ... fascinated you made the connection so fast.”

“Why wouldn’t I?” Albus raised his eyebrows. “What I know about you is that you’re dedicated to find out as much about the Deathly Hallows as you can, and I also know you want to abolish the Statute of Secrecy though a revolutionary process. Assuming a link between the two seemed only logical.”

“If you put it that way...” Suddenly Gellert felt dumb in comparison to Albus’s quick wit, and he hated that feeling. He tried to make it up with an eventual reply to Albus’s questions.

“I will travel to all the countries that signed the Statute of Secrecy where I will convince as many witches and wizards of its negative effects as I can,” Gellert said in the same confident tone in which he had explained his reasons to repeal the statute. “I will show them all the evil Muggles will not only do to us but to each other if we fail to contain them.” Again, he made a short pause, lowering his tone. “It is only us who are able to ensure human co-existence without war. We are much more willing to see beyond the conflicts, territorial and otherwise, that modern Muggle states have with each other. Ultimately, the ability to do magic unites us well beyond the nationalist quarrels of Muggles.”

Albus acknowledged Gellert’s words with a curt nod, closing his eyes for a moment while he raised his eyebrows. Gellert waited for him to pass his judgment, heart pounding.

“Alright,” Albus said. “You still didn’t answer my question about the Hallows, but I’ve got another one: Showing them the evil Muggles will do?” He gave Gellert another piercing look out of bright blue eyes.

Gellert’s first impulse was to deflect that question; to talk about how anyone who had all but a cursory glance at Muggle newspapers on the Continent once in a while would know how eager they all were—the Germans, the French, the Austrians, the Russians—all so eager to measure their strength with each other. How it was only a question of time that they would finally clash; that there would certainly be a war nobody had seen before...

He realised it would not do. He wouldn’t be able to fool him. Not Albus.

“I Saw it,” he said simply. “I’ve been Seeing ... a war like none there has ever been before ... terrible things people do to each other ... ever since I was a kid.” His first impulse was to look away from Albus; to avoid the look of doubt that had always been a given after confessions like this; the calming tone: Surely you’ve just been dreaming. Horrible nightmares. Perhaps you shouldn’t read so much if it’s giving you bad dreams...

“That must have been terrible.”

Gellert stared at Albus wide-eyed. He only saw compassion in the way Albus gazed at him; no doubt, no incredulity. I bared my soul to you and you did not tear it apart, he thought. This was a first.

“I learned to deal with it,” Gellert said. “How to control the visions so they can’t overwhelm me at any minute. Just sometimes, when I’m agitated or asleep...” He broke off, giving Albus a small, bitter smile. “But yes, I had ... quite an interesting childhood before I learned how to control my magic.”

At that, Albus raised his arm as if to touch him; to return, perhaps, the hug Gellert had given him earlier. But he seemed to think better of it, focusing, instead, on a spot somewhere above Gellert’s head.

“Do you have a means to show your visions to other people?” Albus said eventually. “To the wider audience you want to reach?”

“I’m ... experimenting with something, though it’s not quite ready yet,” Gellert admitted. He wasn’t prepared to lay all his cards on the table all at once. “But you said you were a Legilimens?” He gave Albus an inquiring look.

“Some people say I’m quite good at Legilimency,” Albus admitted with a smile.

Gellert grinned. That, he supposed, translated to Not to boast, but I’m actually brilliant at it in Albus speech. He made an inviting gesture.

“Go ahead.”

“Right now?” Albus laughed incredulously. “Better sit ... I don’t know, on my bed? Having someone look at memories ... visions ... like these can get quite intense, I imagine.”

“That’s really not necessary.” Gellert tried to brush Albus’s concerns off. “But thank you nonetheless. I appreciate the opportunity to sit for a bit.” He flopped unceremoniously on Albus’s bed. “I just need a moment to sort my visions...” And lock my other thoughts, he thought to himself. There were many things on his mind that he didn’t want Albus to find out right now, from his expulsion and the reasons for it to his fascination with and admiration of Albus himself. He did plan to tell Albus eventually, but all in due time and certainly not by accident because he wasn’t good enough at Occlumency.

“Now,” he said, consciously thinking about the men in dirty trenches; the machines, cannonballs, explosions and, of course, that dreadful vapour.

“Legilimens,” he heard Albus whisper, and then the images became as clear as in his visions again; as if he was standing right beside those men who were wiped out in this cruel, faceless machinery of war where you rarely even saw the enemy that killed you.

“Gellert,” a deep voice said softly. “Gellert, it’s alright. You’re here, in my room. Open your eyes.”

Albus’s auburn hair was the first thing that swam into focus. His bright blue eyes followed, and then Gellert was seeing him clearly. It was only now that he realised he was shivering. Albus was holding him by the shoulders, steadying him.

“Sorry,” he whispered. “It ... I should have become used to it by now, but somehow...”

“I hope you’ll never become used to that,” Albus said. There was a raw sincerity to his tone that made Gellert want to lean in and have his hair petted, just like his mother did when he was little: Semmi baj, Gellért, minden rendben van... He straightened himself instead, gazing directly into Albus’s eyes.

“There will be men who won’t get that choice,” he said. “Not to become used to that, I mean. Unless we act.”

“I see that now,” Albus said, staring into the void as if it was him who was able to look into the future, not Gellert. “And this is coming from someone who always thought Divination was humbug.” He gave Gellert a lopsided smile and took his hands from his shoulders. The moment when Gellert could have leaned in was gone.

“Divination is a tricky subject if you don’t have any natural talent for it,” Gellert admitted. “In that case, the best you can do is foretell events with a certain plausibility.” He returned Albus’s crooked smile. “Your intuition is probably more accurate than the predictions of untalented people who try their hands at Divination.”

“I should hope so.” There it was, that tiny, confident smile, only noticeable for the twitching corners of Albus’s mouth. Gellert felt himself fall into those sparkling blue eyes, acutely aware of how physically close Albus was to him. This time, his racing heart had nothing to do with his visions.

Then Albus rose from the bed. Gellert already thought another precious moment lost, but Albus returned soon enough with the bowl of sweets from his desk. Sitting down next to Gellert, he pulled a wrapped chocolate frog from the bowl and offered it to Gellert.

“Do you like sweets?” Albus asked. “I’ve always found a little bit of chocolate quite comforting after emotionally troubling experiences.”

Gellert nodded gratefully and took the enchanted piece of chocolate. He was a little picky when it came to sweets, but he did like chocolate in any way, shape or form. Even if that form was moving and threatened to hop away if you didn’t catch it fast enough.

Gellert took no chances. He grabbed one of the frog’s legs as he was unwrapping it, putting it in his mouth as soon as he had freed it from the paper.

“Ah, a connoisseur!” Albus smirked, unwrapping his own chocolate frog in a similar way. “So which card did you get?” he asked, mouth full. Gellert chuckled. Normally, he didn’t like when people spoke with their mouth full, but if Albus did it, it was somehow endearing.

“Faris Spavin,” he said, holding the card up. It showed the very old, very wrinkled face of a wizard with thick reading glasses.

“Oh, the Minister of Magic himself,” Albus said. He had swallowed his frog in the meantime. “The longest-ever serving Minister and also the one with the most long-winding speeches. They call him Spout-Hole behind his back.” Albus chuckled. “Though I must admit it’s less funny if you sit in the Wizengamot and can’t leave because he won’t stop talking.” He pulled a face. “I started bringing books with me to have at least something to do while he kept babbling. Sometimes I wonder if I should thank him for acing all my N.E.W.T.s.” Gellert couldn’t help it; he burst out laughing.

“See?” Albus said with a satisfied smirk. “A bit of chocolate always cheers you up. Especially if it’s a chocolate frog.”

“Oh no,” Gellert replied, still grinning. “It’s you who cheered me up. And I appreciate it.” Toning down his obvious flirtation, he added: “But now I want to know which card you got!”

Albus gave him a melancholy smile. He held up his card so Gellert could see it as well. It showed another old man, much frailer than Faris Spavin. The wrinkled face was devoid of Faris Spavin’s impressive beard and moustache.

“Ah!” Gellert’s eyes widened in recognition. “That’s Nicholas Flamel, isn’t it? The famous alchemist?”

“None other.” Albus’s smile faded and he stared pensively at his card. “Do you want it? I’ve got several already.” Gellert ignored his question.

“What’s the matter?” he asked. “You look so sad.”

“Oh, it’s just...” Albus sighed. “Mr Flamel and me corresponded. He invited me to visit him in Paris during my tour on the Continent...”

“But since you couldn’t go, you can’t meet him now,” Gellert completed the sentence for him. “I’m sorry, Albus, but I’m sure you’re going to meet him eventually.”

“I hope so.” Albus tried another, more confident smile.

“You will.” Gellert took Albus’s free hand and gave it a reassuring squeeze.

“Thank you, Gellert.” Albus looked into his eyes. Gellert felt a sudden urge to lean forward and try to kiss him; try to kiss away the melancholy and the sadness in Albus’s life. But it would have been too early—they knew too little about one another—and there were several things Gellert wanted to tell Albus before he burdened him with his feelings.

The moment passed. Gellert withdrew his hand, passing his chocolate frog card from one hand into the other.

“Do you have that one already?” he said, holding Faris Spavin’s card up again. “If not, we could exchange our cards.”

“I do, actually.” Albus chuckled as if nothing had happened. Gellert suddenly realised that this was Albus’s way to deal with negative emotions: Laughing past the sadness. And perhaps, Gellert thought, he wasn’t all that different; filling his life at Durmstrang with pranks and capers that sometimes got out of hand.

“In that case...” Gellert held out his hand, smirking. “I’ll gladly accept your offer to gift me the Nicholas Flamel card. Let it be a token of our beginning friendship.” Now Albus actually laughed, handing him the card. Gellert took the pouch from his belt and put both cards inside, wiggling his eyebrows at Albus.

“Don’t think you can chicken out of my question about the Hallows just because you’ve declared the card a friendship token!” Albus said as soon as he had stopped laughing.

“Chicken out?” Gellert said, pretending to be affronted. “You wound me. I don’t chicken out of anything!”

“Well then.” Albus grinned at Gellert’s mock annoyance, but his posture had become more serious. “How will the Hallows help you achieve your goal?”

“Not all of the Hallows,” Gellert replied. “Wait.” He retrieved an old book from his pouch, realising belatedly that it still had a Durmstrang Library: Restricted stamp on its spine. Well. Albus didn’t know yet that he had been expelled. He also had no means of knowing that while Durmstrang pupils were allowed to read books from the Restricted Section of their library, they weren’t allowed to borrow them.

Placing the book between Albus and himself so both of them could read in it, he tipped on it with his wand, casting a wordless spell. Then he flicked to the page where it all started; the page he knew by heart at this point.

“Here.” He used the tip of his wand to point Albus to the relevant passage, knowing better by now than to use his finger. Albus’s eyes flicked over the passage with remarkable speed.

“Ah!” he said at last. “Godelot, the author of Magick Moste Evile, explains in his notebook that he wrote his famous reference book on Dark Arts with the help of his ‘moste wicked and subtle friend, with bodie of Ellhorn’!” Before Gellert could say anything, Albus placed his finger over the word “Ellhorn,” only to pull it back with a pained yelp.

“Ouch!” Albus frowned at the little drop of blood that came out of his index finger. “That stung!”

“Sorry,” Gellert said with a contrite smile. “I should have warned you.”

“You should.” Albus glowered at him, licking the drop of blood off his hand. Gellert suddenly found it uncomfortably warm in the room. He hurriedly looked away, staring at the open page.

“And you should wash your finger rather than lick it after touching an old book,” Gellert scolded, trying to divert Albus’s attention from the blush that had surely formed on his cheeks by now. “You never know which forms of mould and magical contamination the parchment could contain.”

“I doubt there is any real danger,” Albus said with a shrug. “You got stung, too, didn’t you? And you’re still alive as well.”

“But I didn’t lick my darn index finger!” Gellert glowered at him. By contrast, Albus’s gaze softened and he gave an amused chuckle.

“Your concern for my health is quite endearing, but I assure you it’s entirely uncalled-for,” he said with a smile. Then he bowed over the book again, and Gellert decided that maybe it wasn’t so bad that their heads were almost touching as they read in it.

“Well,” Albus said after his eyes had darted over the passage. “I’m afraid that’s not as helpful as it could be. Yes, it may serve as evidence that a particularly powerful wand made of elder actually exists, but all we know is that the early medieval wizard Godelot had a powerful wand made of elder that he used to help him write his collection of dangerous spells. We also know he was starved by his own son Hereward so he could gain ownership of that wand. What we don’t learn, sadly, is the exact amount of power Godelot’s wand had and what happened to the wand after Hereward gained possession of it.”

“That’s true,” Gellert admitted. “I—we?” He gave Albus a hopeful glance, but the other boy’s expression remained unreadable. “We,” he continued nonetheless, “need to find later evidence for the Elder Wand’s existence, and we need to learn if it is really as powerful as legend has it. But if it is...” He looked up, staring directly at Albus. “If it really is that powerful, and if you can really learn ancient spells from it that its former owners performed, it will be of great help to us because it cannot be easily overcome.”

“Very well.” Albus slid away from the book, resting his back against the wall. “Assuming that I decide to help you, and assuming that we actually manage to find the Elder Wand ... which one of us should have it?” His tone was not suspicious, not accusatory; merely curious. “You—or me?”

“I thought we could ... maybe ... share it?” Gellert glanced nervously at Albus.

“Share it?” Albus raised an eyebrow. “Wouldn’t you want it just for yourself?”

“I...” Gellert blushed. “I think that’s exactly the problem all the former owners of the Elder Wand had. They boasted with it, like the eldest of the three brothers in the tale, or they wanted it so much they killed their own family for it, like Hereward did with his father.” He thrummed his fingers nervously, stilling them as he realised that he was quite close to putting them on the stinging pages of the old book. “I admit the story of the Hallows fascinated me ever since I first heard of them, but I don’t want the Elder Wand just to possess it. I want it because I want to use it for my—our cause.” He paused, only to add in a low tone and in a very rushed manner: “I so want this to be our cause, not just mine.”

“Why?” Again, something in Albus’s gaze had shifted; something Gellert couldn’t quite read.

“Because you’re brilliant!” Gellert exclaimed. “And I don’t say that because Aunt Batty told me so; I say that because I’ve never been able to talk about any of my ideas the way I did today. I believe I’ve only got a glimpse into your magic so far, but what I saw—what you made me See ... That was amazing.” He looked at Albus, half expectant and half nervous of his reaction.

“Gellert,” Albus said. Gellert was still unable to read his tone and it was almost driving him up the pole. “What you said about the freedom to be who you are ... that we need to prevent the dreadful scenario you Saw ... your idea to use the Elder Wand to make sure you can overcome the forces opposed to the idea of change ... All of that sounds quite appealing to me.”

Gellert stared at him, full of hope and yet reluctant. Quite? What did Albus mean by quite?

“But I think you’ve focused too much on your ideas so far,” Albus continued. “What you need is a strategy. A method to convince people in a way that goes beyond showing them your visions.” Albus locked eyes with him. Gellert’s heart was beating faster. He had realised by now Albus tended to avoid looking directly into someone’s eyes unless he thought it necessary to get a point across.

“I can help you come up with a strategy,” Albus said. “Let’s make this our cause.”

Notes:

Semmi baj, Gellért, minden rendben van... is Hungarian for Nothing’s wrong, Gellert, everything is alright... Thank you to the lovely Ivett (isabellaofparma on tumblr) for helping me with the Hungarian! ❤️

Neither Faris Spavin nor Nicholas Flamel are mentioned as characters on chocolate frog cards by JKR, but I figured there would likely be cards at the end of the 19th century that aren’t printed at the end of the 20th century anymore. They’ve probably become expensive collectors’ items by now. (I do think it would be reasonable to assume Nicholas Flamel has his own chocolate frog card, though.)

The “quote from Godelot’s notebook” is taken from Albus Dumbledore’s commentary on “The Tale of the Three Brothers” in The Tales of Beedle the Bard. (As someone who’s interested in the history of the English language, I feel the need to point out that Godelot, as an early medieval figure, should have written in Old English rather than in this toned down mock Middle English. Then again, maybe Albus is quoting from a later source that didn’t retain the original Old English... ;) )

#grindeldore#albus dumbledore#gellert grindelwald#harry potter#fantastic beasts#fanfiction#my fanfiction#katemarley#grindellore

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

LAW # 7 : GET OTHERS TO DO THE WORK FOR YOU, BUT ALWAYS TAKE THE CREDIT

JUDGEMENT

Use the wisdom, knowledge, and legwork of other people to further your own cause. Not only will such assistance save you valuable time and energy, it will give you a godlike aura of efficiency and speed. In the end your helpers will be forgotten and you will be remembered. Never do yourself what others can do for you.

TRANSGRESSION AND OBSERVANCE OF THE LAW

In 1883 a young Serbian scientist named Nikola Tesla was working for the European division of the Continental Edison Company. He was a brilliant inventor, and Charles Batchelor, a plant manager and a personal friend of Thomas Edison, persuaded him he should seek his fortune in America, giving him a letter of introduction to Edison himself. So began a life of woe and tribulation that lasted until Tesla’s death.

THE TORTOISE, THE ELEPHANT AND THE HIPPOPOTAMUS

One day the tortoise met the elephant, who trumpeted, “Out of my way, you weakling—I might step on you!” The tortoise was not afraid and stayed where he was, so the elephant stepped on him, but could not crush him. “Do not boast, Mr. Elephant, I am as strong as you are!” said the tortoise, but the elephant just laughed. So the tortoise asked him to come to his hill the next morning. The next day, before sunrise, the tortoise ran down the hill to the river, where he met the hippopotamus, who was just on his way back into the water after his nocturnal feeding. “Mr Hippo! Shall we have a tug-of-war? I bet I’m as strong as you are!” said the tortoise. The hippopotamus laughed at this ridiculous idea, but agreed. The tortoise produced a long rope and told the hippo to hold it in his mouth until the tortoise shouted “Hey!” Then the tortoise ran back up the hill where he found the elephant, who was getting impatient. He gave the elephant the other end of the rope and said, “When I say ‘Hey!’ pull, and you’ll.see which of us is the strongest. ”Then he ran halfway back down the hill, to a place where he couldn’t be seen, and shouted, “Hey!” The elephant and the hippopotamus pulled and pulled, but neither could budge the other-they were of equal strength. They both agreed that the tortoise was as strong as they were. Never do what others can do for you. The tortoise let others do the work for him while he got the credit.

ZAIREAN FABLE

When Tesla met Edison in New York, the famous inventor hired him on the spot. Tesla worked eighteen-hour days, finding ways to improve the primitive Edison dynamos. Finally he offered to redesign them completely. To Edison this seemed a monumental task that could last years without paying off, but he told Tesla, “There’s fifty thousand dollars in it for you—if you can do it.” Tesla labored day and night on the project and after only a year he produced a greatly improved version of the dynamo, complete with automatic controls. He went to Edison to break the good news and receive his $50,000. Edison was pleased with the improvement, for which he and his company would take credit, but when it came to the issue of the money he told the young Serb, “Tesla, you don’t understand our American humor!,” and offered a small raise instead.

Tesla’s obsession was to create an alternating-current system (AC) of electricity. Edison believed in the direct-current system (DC), and not only refused to support Tesla’s research but later did all he could to sabotage him. Tesla turned to the great Pittsburgh magnate George Westinghouse, who had started his own electricity company. Westinghouse completely funded Tesla’s research and offered him a generous royalty agreement on future profits. The AC system Tesla developed is still the standard today—but after patents were filed in his name, other scientists came forward to take credit for the invention, claiming that they had laid the groundwork for him. His name was lost in the shuffle, and the public came to associate the invention with Westinghouse himself.

A year later, Westinghouse was caught in a takeover bid from J. Pierpont Morgan, who made him rescind the generous royalty contract he had signed with Tesla. Westinghouse explained to the scientist that his company would not survive if it had to pay him his full royalties; he persuaded Tesla to accept a buyout of his patents for $216,000—a large sum, no doubt, but far less than the $12 million they were worth at the time. The financiers had divested Tesla of the riches, the patents, and essentially the credit for the greatest invention of his career.

The name of Guglielmo Marconi is forever linked with the invention of radio. But few know that in producing his invention—he broadcast a signal across the English Channel in 1899—Marconi made use of a patent Tesla had filed in 1897, and that his work depended on Tesla’s research. Once again Tesla received no money and no credit. Tesla invented an induction motor as well as the AC power system, and he is the real “father of radio.” Yet none of these discoveries bear his name. As an old man, he lived in poverty.

In 1917, during his later impoverished years, Tesla was told he was to receive the Edison Medal of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. He turned the medal down. “You propose,” he said, “to honor me with a medal which I could pin upon my coat and strut for a vain hour before the members of your Institute. You would decorate my body and continue to let starve, for failure to supply recognition, my mind and its creative products, which have supplied the foundation upon which the major portion of your Institute exists.”

Interpretation

Many harbor the illusion that science, dealing with facts as it does, is beyond the petty rivalries that trouble the rest of the world. Nikola Tesla was one of those. He believed science had nothing to do with politics, and claimed not to care for fame and riches. As he grew older, though, this ruined his scientific work. Not associated with any particular discovery, he could attract no investors to his many ideas. While he pondered great inventions for the future, others stole the patents he had already developed and got the glory for themselves.

He wanted to do everything on his own, but merely exhausted and impoverished himself in the process.

Edison was Tesla’s polar opposite. He wasn’t actually much of a scientific thinker or inventor; he once said that he had no need to be a mathematician because he could always hire one. That was Edison’s main method. He was really a businessman and publicist, spotting the trends and the opportunities that were out there, then hiring the best in the field to do the work for him. If he had to he would steal from his competitors. Yet his name is much better known than Tesla’s, and is associated with more inventions.

To be sure, if the hunter relies on the security of the carriage, utilizes the legs of the six horses, and makes Wang Liang hold their reins, then he will not tire himself and will find it easy to overtake swift animals. Now supposing he discarded the advantage of the carriage, gave up the useful legs of the horses and the skill of Wang Liang, and alighted to run after the animals, then even though his legs were as quick as Lou Chi’s, he would not be in time to overtake the animals. In fact, if good horses and strong carriages are taken into use, then mere bond-men and bondwomen will be good enough to catch the animals.

HAN-FEI-TZU, CHINESE PHILOSOPHER, THIRD CENTURY B.C.

The lesson is twofold: First, the credit for an invention or creation is as important, if not more important, than the invention itself. You must secure the credit for yourself and keep others from stealing it away, or from piggy-backing on your hard work. To accomplish this you must always be vigilant and ruthless, keeping your creation quiet until you can be sure there are no vultures circling overhead. Second, learn to take advantage of other people’s work to further your own cause. Time is precious and life is short. If you try to do it all on your own, you run yourself ragged, waste energy, and burn yourself out. It is far better to conserve your forces, pounce on the work others have done, and find a way to make it your own.

Everybody steals in commerce and industry.

I’ve stolen a lot myself.

But I know how to steal.

Thomas Edison, 1847-1931

KEYS TO POWER

The world of power has the dynamics of the jungle: There are those who live by hunting and killing, and there are also vast numbers of creatures (hyenas, vultures) who live off the hunting of others. These latter, less imaginative types are often incapable of doing the work that is essential for the creation of power. They understand early on, though, that if they wait long enough, they can always find another animal to do the work for them. Do not be naive: At this very moment, while you are slaving away on some project, there are vultures circling above trying to figure out a way to survive and even thrive off your creativity. It is useless to complain about this, or to wear yourself ragged with bitterness, as Tesla did. Better to protect yourself and join the game. Once you have established a power base, become a vulture yourself, and save yourself a lot of time and energy.

A hen who had lost her sight, and was accustomed to scratching up the earth in search of food, although blind, still continued to scratch away most diligently. Of what use was it to the industrious fool? Another sharp-sighted hen who spared her tender feet never moved from her side, and enjoyed, without scratching, the fruit of the other’s labor. For as often as the blind hen scratched up a barley-corn, her watchful companion devoured it.

FABLES, GOITCHOLD LESSING, 1729-1781

Of the two poles of this game, one can be illustrated by the example of the explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa. Balboa had an obsession—the discovery of El Dorado, a legendary city of vast riches.

Early in the sixteenth century, after countless hardships and brushes with death, he found evidence of a great and wealthy empire to the south of Mexico, in present-day Peru. By conquering this empire, the Incan, and seizing its gold, he would make himself the next Cortés. The problem was that even as he made this discovery, word of it spread among hundreds of other conquistadors. He did not understand that half the game was keeping it quiet, and carefully watching those around him. A few years after he discovered the location of the Incan empire, a soldier in his own army, Francisco Pizarro, helped to get him beheaded for treason. Pizarro went on to take what Balboa had spent so many years trying to find.

The other pole is that of the artist Peter Paul Rubens, who, late in his career, found himself deluged with requests for paintings. He created a system: In his large studio he employed dozens of outstanding painters, one specializing in robes, another in backgrounds, and so on. He created a vast production line in which a large number of canvases would be worked on at the same time. When an important client visited the studio, Rubens would shoo his hired painters out for the day. While the client watched from a balcony, Rubens would work at an incredible pace, with unbelievable energy. The client would leave in awe of this prodigious man, who could paint so many masterpieces in so short a time.

This is the essence of the Law: Learn to get others to do the work for you while you take the credit, and you appear to be of godlike strength and power. If you think it important to do all the work yourself, you will never get far, and you will suffer the fate of the Balboas and Teslas of the world. Find people with the skills and creativity you lack. Either hire them, while putting your own name on top of theirs, or find a way to take their work and make it your own. Their creativity thus becomes yours, and you seem a genius to the world.

There is another application of this law that does not require the parasitic use of your contemporaries’ labor: Use the past, a vast storehouse of knowledge and wisdom. Isaac Newton called this “standing on the shoulders of giants.” He meant that in making his discoveries he had built on the achievements of others. A great part of his aura of genius, he knew, was attributable to his shrewd ability to make the most of the insights of ancient, medieval, and Renaissance scientists. Shakespeare borrowed plots, characterizations, and even dialogue from Plutarch, among other writers, for he knew that nobody surpassed Plutarch in the writing of subtle psychology and witty quotes. How many later writers have in their turn borrowed from—plagiarized—Shakespeare ?

We all know how few of today’s politicians write their own speeches. Their own words would not win them a single vote; their eloquence and wit, whatever there is of it, they owe to a speech writer. Other people do the work, they take the credit. The upside of this is that it is a kind of power that is available to everyone. Learn to use the knowledge of the past and you will look like a genius, even when you are really just a clever borrower.

Writers who have delved into human nature, ancient masters of strategy, historians of human stupidity and folly, kings and queens who have learned the hard way how to handle the burdens of power—their knowledge is gathering dust, waiting for you to come and stand on their shoulders. Their wit can be your wit, their skill can be your skill, and they will never come around to tell people how unoriginal you really are. You can slog through life, making endless mistakes, wasting time and energy trying to do things from your own experience. Or you can use the armies of the past. As Bismarck once said, “Fools say that they learn by experience. I prefer to profit by others’ experience.”

Image: The Vulture. Of all the creatures in

the jungle, he has it the easiest. The

hard work of others becomes his work;

their failure to survive becomes his

nourishment. Keep an eye on

the Vulture—while you are

hard at work, he is cir

cling above. Do not

fight him, join

him.

Authority: There is much to be known, life is short, and life is not life without knowledge. It is therefore an excellent device to acquire knowledge from everybody. Thus, by the sweat of another’s brow, you win the reputation of being an oracle. (Baltasar Gracián, 1601-1658)

REVERSAL

There are times when taking the credit for work that others have done is not the wise course: If your power is not firmly enough established, you will seem to be pushing people out of the limelight. To be a brilliant ex ploiter of talent your position must be unshakeable, or you will be accused of deception.

Be sure you know when letting other people share the credit serves your purpose. It is especially important to not be greedy when you have a master above you. President Richard Nixon’s historic visit to the People’s Republic of China was originally his idea, but it might never have come off but for the deft diplomacy of Henry Kissinger. Nor would it have been as successful without Kissinger’s skills. Still, when the time came to take credit, Kissinger adroitly let Nixon take the lion’s share. Knowing that the truth would come out later, he was careful not to jeopardize his standing in the short term by hogging the limelight. Kissinger played the game expertly: He took credit for the work of those below him while graciously giving credit for his own labors to those above. That is the way to play the game.

5 notes

·

View notes