#Albian fossil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

EXCEPTIONALLY RARE: Siphonia tulipa Fossil Sponge | Upper Albian Cretaceous Haldon Hills Devon UK | Genuine Specimen with COA

Discover an exceptionally rare and scientifically significant fossil—this beautifully preserved specimen of Siphonia tulipa, an extinct Cretaceous sponge from the Upper Albian stage of the Cretaceous period, collected from the Upper Greensand Formation of the Haldon Hills, Devon, UK. Sponges of this calibre and preservation are seldom found and highly sought after by collectors and researchers alike.

Fossil Type: Sponge (Porifera)

Species: Siphonia tulipa

Geological Period: Cretaceous (~113 to 100.5 million years ago)

Geological Stage: Upper Albian

Formation: Upper Greensand

Location: Haldon Hills, Devon, United Kingdom

Scale Rule: Squares/Cube = 1cm (Please refer to the photo for accurate sizing)

Specimen: The specimen shown in the photo is the exact one you will receive

Authenticity: All of our fossils are 100% genuine specimens and come with a Certificate of Authenticity

Geological and Paleontological Information

Siphonia tulipa is a genus of extinct siliceous sponge characterised by its elegant vase- or tulip-shaped body, often with a central osculum (opening) and stalked base for attachment to the seafloor. These sponges lived in shallow marine environments during the Upper Albian of the Cretaceous period, a time marked by significant marine diversification.

Phylum: Porifera

Class: Demospongiae

Order: Hadromerida

Family: Siphoniidae

Genus: Siphonia

Species: Siphonia tulipa

Geological Stage: Upper Albian (~105 million years ago)

Depositional Environment: Shallow, warm marine shelf with calcareous and glauconitic sandy sediments typical of the Upper Greensand; ideal for sponge colonization and fossilization

Morphological Features: Distinctive tulip or flask-shaped body with a central osculum; typically hollow with preserved internal canal structures; fine surface texture may show radial ridging or tubercles

Notable: Fossils of Siphonia tulipa from Haldon Hills are extremely rare and prized for their completeness and clarity of preservation

Biozone: Correlates with Upper Albian ammonite zones (e.g., Mortoniceras inflatum Zone), aiding regional stratigraphic dating

Identifier: First formally described in 19th-century British paleontological literature during the survey of the Upper Greensand faunas

Why This Fossil Is Special

This is not your average fossil sponge—Siphonia tulipa is exceptionally rare, especially in such a well-preserved state from the classic Upper Greensand of Devon. Its beautiful form, striking preservation, and scientific relevance make it a centrepiece for any fossil collection or educational exhibit.

Why Buy From Us?

100% genuine fossil with Certificate of Authenticity

Exact specimen shown is what you’ll receive

Carefully sourced from historic UK fossil sites

Ideal for collectors, researchers, and museums

Secure this remarkable example of ancient marine life—an exceptionally rare Siphonia tulipa fossil sponge from the Upper Albian Cretaceous of Haldon Hills, Devon, preserved for over 100 million years beneath England’s prehistoric seas.

#Siphonia tulipa#fossil sponge#rare fossil sponge#Upper Greensand fossil#Cretaceous sponge#Albian fossil#Haldon Hills fossil#Devon fossil#UK fossil#Siphoniidae fossil#Cretaceous invertebrate#fossil with certificate#genuine fossil#certified sponge fossil#natural history fossil#paleontology specimen#fossil collection#ancient marine life

0 notes

Text

Hypnovenator matsubaraetoheorum Kubota et al., 2024 (new genus and species)

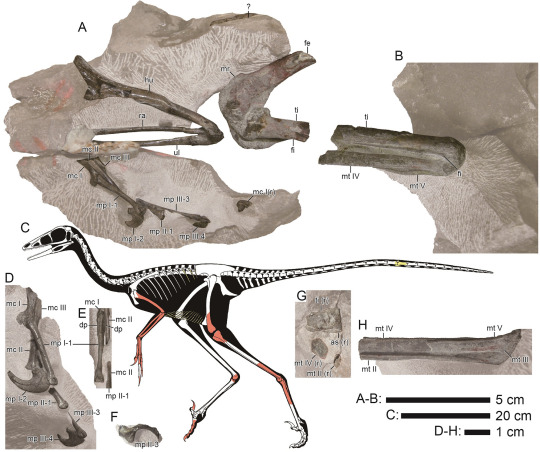

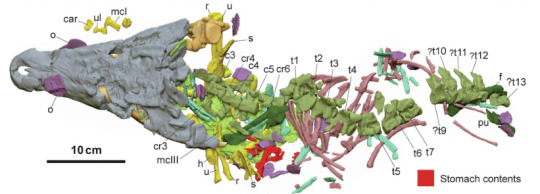

(Type specimen and schematic skeletal of Hypnovenator matsubaraetoheorum, with preserved bones in red and yellow, from Kubota et al., 2024)

Meaning of name: Hypnovenator = sleep [in Greek] hunter [in Latin]; matsubaraetoheorum = for Kaoru Matsubara and Takaharu Ohe [discoverers of part of the original fossil]

Age: Early Cretaceous (Albian), between 106.4–112.1 million years ago

Where found: Ohyamashimo Formation, Hyōgo, Japan

How much is known: Partial skeleton of one individual, including limb bones, gastralia (belly ribs), and two tail vertebrae.

Notes: Hypnovenator was a troodontid, a group of relatively small, bird-like theropods. It is the first troodontid to be named from Japan. Unlike other Early Cretaceous troodontids, but similar to many Late Cretaceous ones, Hypnovenator had feet in which the outermost metatarsal (long bone of the foot) was substantially wider at its base than the second innermost metatarsal. In troodontids, the outer two metatarsals supported the main weight-bearing toes on each foot, whereas the second innermost toe was typically held off the ground. The relatively more robust outer metatarsal in Hypnovenator and later troodontids may therefore be a specialization towards greater running ability.

Several other troodontids, namely Sinornithoides, Mei, and Sinovenator, are known from one or more specimens that appear to have been preserved while they were sitting down (perhaps even sleeping). The folded posture of the limbs in the type specimen of Hypnovenator suggests that it may have died in a similar pose as well.

Reference: Kubota, K., Y. Kobayashi, and T. Ikeda. 2024. Early Cretaceous troodontine troodontid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Ohyamashimo Formation of Japan reveals the early evolution of Troodontinae. Scientific Reports 14: 16392. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-66815-2

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPY-noh-SOAR-uss -- THE "SPINY LIZARD" OF PRESENT DAY NORTH AFRICA.

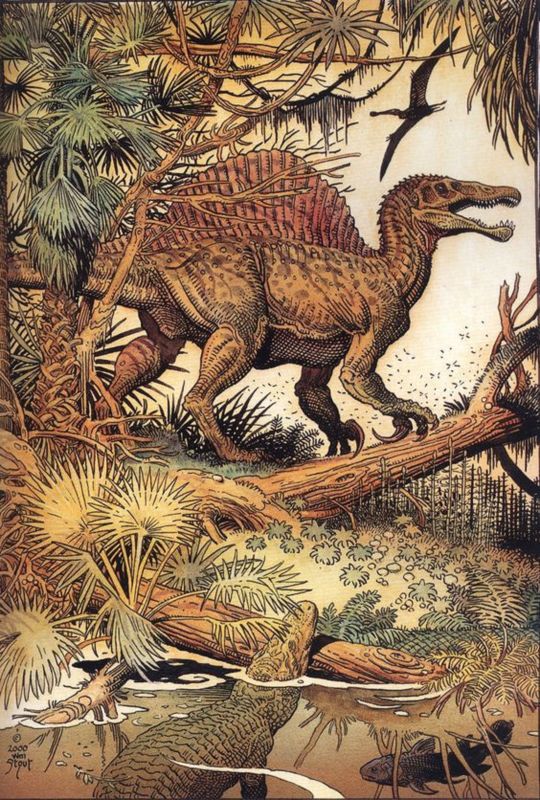

PIC INFO: Resolution at 1692x2508 -- Spotlight on Spinosaurus (meaning "spine lizard"), a genus of theropod dinosaur that lived in what now is North Africa during the upper Albian to upper Turonian stages of the Cretaceous period, about 112 to 93.5 million years ago.

The best known species is S. aegyptiacus from Egypt, although a potential second species, S. maroccanus, has been recovered from Morocco. Artwork by William Stout, c. 2000.

Name: Spinosaurus (Spine lizard)

Phonetic: Spine-oh-sore-us.

Named By: Ernst Stromer - 1915.

Synonyms: Sigilmassasaurus?

Classification: Chordata, Reptilia, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Theropoda, Megalosauroidea, Spinosauridae, Spinosaurinae.

Species: S. aegyptiacus (type), S. maroccanus is a possible second, although many consider this species as being the same as the type species.

Diet: Piscivore/Carnivore.

Size: Estimates highly variable amongst sources and range anywhere between 12.6 and 18 meters total body length. Skull length estimated between 1.5 and 1.75 meters long.

Known locations: North Africa, particularly Egypt - Bahariya Formation, and Morocco - Kem Kem Beds.

Time period: Albian to Cenomanian of the Cretaceous.

Fossil representation: To date at least six partial specimens of the skull, mandible, neural spines and other fragmentary post cranial remains. Teeth however are considerably more common.

Sources: www.prehistoric-wildlife.com/species/s/spinosaurus.html, www.mindat.org/taxon-4967112.html, & Pinterest.

#Spinosaurus#William Stout#Dino Art#Spinosaurus Aegyptiacus#S. aegyptiacus#Theropod#Dinosaurs#Late Cretaceous#William Stout Art#Paleoart#Dinosaur Art#Spinosaurus aegypticus#Spinosauridae#Prehistoric#Prehistory#Prehistoric Creatures#Prehistoric Animals#William Stout Artist#Palaeoart#Palaeo Art#Dinosaur#Illustration

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Geology Museums of Britain: Folkestone Museum, Kent

Jon Trevelyan (UK) Recently, I spent a few days on my own down at one of my favourite fossil hunting sites – Copt Point and East Wear Bay in Folkestone. As readers probably know, the Gault Clay at Folkestone is a marine sedimentary deposit from the Lower Cretaceous (Albian) period, consisting mainly of dark grey to blue-grey silty clay, with occasional layers of silt and sand (or put another…

0 notes

Text

Taylor & Francis publications 27th July 2023- 1st August 2023

There have been a lot of interesting documents released between 27th July-1st August on the Taylor & Francis website; i decided to include the released papers' doi here.

Feel free to read them if you are interested, i have marked the papers available free to read and the others that require payment. (open access = Blue, payment required = red)

Copy the doi link or title into your search engine and you should be brought to the document.

A new amphibamiform (Temnospondyli: Branchiosauridae) from the lower Permian of the Czech Boskovice Basin

doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2231994

A fossil viper (Serpentes: Viperidae) from the Early Pleistocene of the Crimean Peninsula

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241059

Unusual cystoporate? bryozoan from the Upper Ordovician of Siljan District, Dalarna, central Sweden

doi.org/10.1080/11035897.2023.2223579

Early Devonian Ostracoda from the Norton Gully Sandstone, southeastern Australia

doi.org/10.1080/03115518.2023.2223658

Eocene Araucariaceae in Europe: additional evidence from a new Baltic amber species of the genus Oxycraspedus Kuschel, 1955 (Coleoptera: Belidae)

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2237984

Skeletal taphonomy of the water frogs (Amphibia: Anura) from the Pit 7/8 of the Pliocene Camp dels Ninots site (Caldes de Malavella, NE Spain)

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2237998

Tapejarine pterosaur from the late Albian Paw Paw Formation of Texas, USA, with extensive feeding traces of multiple scavengers

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241044

The first American occurrence of Phoenicopteridae fossil egg and its palaeobiogeographical and palaeoenvironmental implications

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241050

Eocene (Ypresian-Lutetian) mammals from Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Gaiman, Chubut Province, Argentina)

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241054

Turtle tracks from the middle Jurassic Yaopo formation in Beijing, China

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241064

The earliest occurrence of Equus in South Asia

doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2227236

Early Cretaceous radiation of teleosts recorded by the otolith-based ichthyofauna from the Valanginian of Wąwał, central Poland

doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2232008

A stem therian mammal from the Lower Cretaceous of Germany

doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2224848

Vertebrate ichnology and palaeoenvironmental associations of Alaska’s largest known dinosaur tracksite in the Cretaceous Cantwell Formation (Maastrichtian) of Denali National Park and Preserve

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2221267

Biostratigraphical and paleoenvironmental studies of some Miocene‒Pliocene successions in Northwestern Nile Delta, Egypt

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2231978

Hyena and ‘false’ sabre-toothed cat coprolites from the late Middle Miocene of south-eastern Austria

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2237979

Source:

1 note

·

View note

Text

Round Four: Berthasaura vs Caihong

Berthasaura leopoldinae

Artwork by @i-draws-dinosaurs, written by @i-draws-dinosaurs

Name meaning: Bertha and Leopoldina’s reptile (in honour of naturalist and women’s rights activist Bertha Maria Júlia Lutz, and first Empress of Brazil and advocate for Brazilian independence Maria Leopoldina)

Time: Uncertain, likely ~121 to 75 million years ago (Aptian to Albian stages of the Early Creataceous) but may be younger

Location: Goio-Erê Formation, Brazil

Theropods are famously carnivorous dinosaurs, but many, many groups of theropods have decided “actually but what if I didn’t” and gone vegetarian, and yet it’s still wild when another one of those pops up every now and then. Even among them though, Berthasaura is special for being the only theropod that seems to have tried to just straight up turn itself into an ornithopod. The long spindly legs, the teeny little arms, and a big head with a toothless beak all come together to create an utterly bizarre little theropod that honestly nobody could have predicted.

Berthasaura is a noasaur, and those of you familiar will at this moment be saying “oh of course it’s a noasaur” because those guys were small ceratosaurs that were basically Theropod Wacky Experimental Phase 1.0. Within this group you’ve got wild sticky-outy teeth, a single weight-bearing toe on each foot in our fellow competitor Vespersaurus, and now multiple instances of beaks evolving independently. Theropods just love to evolve a beak, what can I say? Whatever the hell Berthasaura had going on, it must have been successful because as the basalmost noasaurid currently known its direct lineage has been surviving since at least the Late Jurassic!

Caihong juji

Artwork by @i-draws-dinosaurs, written by @i-draws-dinosaurs

Name meaning: Rainbow with big crest

Time: 161 million years old (Oxfordian stage of the Late Jurassic)

Location: Tiaojishan Formation, China

It’s always a special treat to hear the announcement of a dinosaur with known colours, because it gives the most direct impression of how truly stunning these animals would have been to witness in real life. And Caihong might just be the most spectacular of them all so far, described in 2018 from an immaculate full-body fossil that preserves detailed feathers! Caihong’s feathers are longer than some other floofy dinosaurs, and would have had the appearance of a luxurious mane along its neck. Not only that, the fossil preserves feather microstructures that in life would have made this dinosaur gloriously iridescent!

Now iridescent dinosaurs aren’t new, Microraptor has been decked out in fabulous starling-esque plumage for a while now, but Caihong absolutely takes it to the next level. Its whole body was covered in iridescent black, including the enormous tail, but the real star of the show are the platelet-like melanosomes found on the head, neck, and the base of the tail. Different from the usual iridescent melanosomes, the structure of these tiny organelles reflects brilliantly iridescent colours, like those on the heads of hummingbirds and particularly the bright purple feathers on the necks of the trumpeter family. Caihong would have put on an absolutely dazzling jewel-toned display in the treetops or on the forest floor of prehistoric China!

#dmm#dmm rising stars#dinosaur march madness#dinosaurs#birds#march madness#bracket#polls#palaeoblr#birblr#paleontology#round four#berthasaura#caihong

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Crocs of 2022

For what its worth, its been a great year for fossil Pseudosuchians, many of which didn't get a lot of attention because people always assume its just "another crocodile". We'll go through them by the order of appearance in the fossil record, or in other words oldest to youngest. Better grab some popcorn and the drink of your choice, cause this is going to be a long one.

Mambawakale

Starting off is Mambawakale ruhuhu (Ruhuhu Basin Crocodile Ancestor in Kiswahili) from the middle Triassic Manda Beds of Tanzania. The fossils for this guy had been known since at least the 1960s, after which it was named Pallisteria angustimentum, a name that was never officially published however. It was a large animal, its skull 75 centimeters long attached to what was likely an animal similar in build to what we think of for "rauisuchians", given that it sits at the base of Paracrocodylomorpha. The below life reconstructoin was done by the fantastic Gabriel Ugueto with Steve Irwin inserted in post by me, tho its not rigorously scaled it gives a general idea of the animal's size.

We can then skip over the Jurassic (no new crocs from that period) and straight into the Cretaceous, specifically the Albian some 100 million years ago.

Yanjisuchus

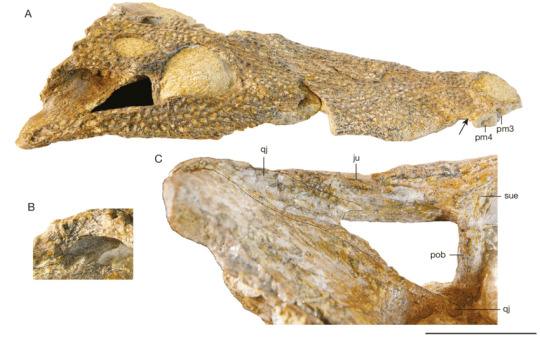

Yanjisuchus longshanensis (Yanji City Crocodile from the Longshan Hill) was a paralligatorid, a group of Neosuchians I fully admitt I'm not too well aquainted with. Its fossils, which include a partial skull, vertebrae osteoderms, ribs, parts of the shoulder girdle and front limbs, were discovered in the Longjing Formation in what is now north-eastern China.

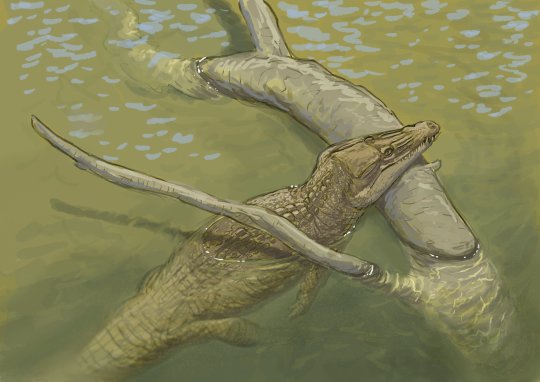

Confractosuchus

One I can decidedly talk more about is Confractosuchus sauroktonos (Lizard Eating Broken Crocodile) from the Australian Winton Formation, home to animals such as Isisfordia, Australovenator and Diamantinasaurus. The genus name refers to the fact that the skull is squashed to hell and back, but its the species name thats interesting. "Lizard eating" in this case refers to the fact that this 2.5 meter long basal Eusuchian was found with preserved stomach contents. Said stomach contents being the bones of a small ornithopod dinosaur as the press release art by Julius Csotonyi enthusiastically shows. The other image here not from the paper was drawn by Joschua Knüppe (@knuppitalism-with-ue ) showing a definitely more relaxed individual.

Eptalofosuchus

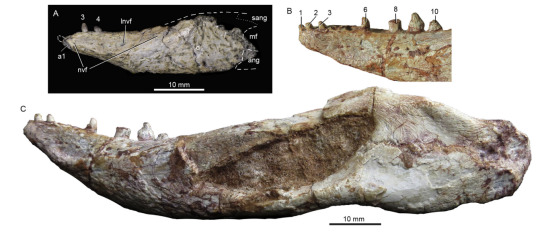

We did know about this guy for a bit longer as the pre-proof has been out since 2021, but lets include it anyways because I wasn't on Tumblr last year. Eptalofosuchus viridi (Green Seven Hills Crocodile) is not a crocodile in the strict sense but a Notosuchian, a cousin to the more typical Neosuchians. This animal is known from a single distinct lower jaw that belonged to a rather small creature. Among Notosuchians, Eptalofosuchus is most closely related to "advanced Notosuchians", specifically Sphagesauridae. We also know that it wasn't alone, as described alongside it are fossils of an unnamed baurusuchid (a large carnivore) and a peirosaurid, a more basal Notosuchian. Finally, both parts of the scientific name allude to the Uberaba Formation, specifically the nickname of Uberaba being “the city of the seven hills” and the green color of the sediments there. Life reconstruction of the little guy was done by the always incredible Júlia d'Oliveira.

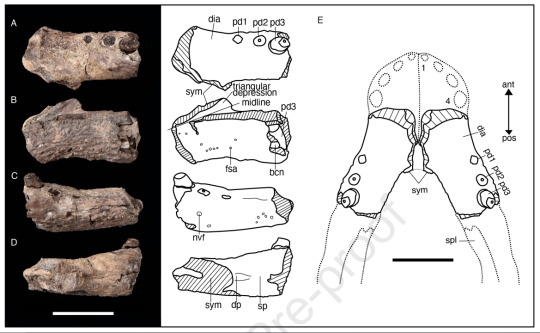

Titanochampsa

Sticking to South America we have Titanochampsa iorii (Ior's Titan Crocodile). A significant find no doubt tho with an estimated size between 2.98–5.88 m (sizable I admitt) based on very scant remains perhaps a little bit hasty. Alas we only have the skull table of this animal, so the precise size can still vary as you can see. But it is still a fascinating one due to the fact that its the ONLY non-Notosuchian from the Bauru Group. Cretaceous South America is almost synonymous with these mostly terrestrial crocodyliforms but surprisingly lacking a diverse semi-aquatic croc fauna. Being at the very least a Neosuchian, possibly Eusuchian, Titanochampsa seems to have filled this niche. Given that the big terrestrial Baurusuchids had relatively weak bites and reached a length of at most 4 meters, this presents an interesting contrast with the strong bite force of the potentially larger semi-aquatic Titanochampsa. And would you look at that, press release art by Júlia once again.

Eurycephalosuchus

One final croc for the Mesozoic, Eurycephalosuchus gannanensis is an animal I covered very recently so I'll keep things brief. Stemming from the Maastrichtian Hekou Formation in south eastern China, Eurycephalosuchus was a very small species of orientalosuchine. Orientalosuchina is recovered as a group of early alligatoroids in the paper, tho talking to Adam Yates (who's croc phylogeny is my go-to) there is a chance they might be closer to crocodiloids. Regardless, Eurycephalosuchus was a small animal with large teeth towards the front of the skull, blunt teeth in the back and an overall very short face (tho there is slight compression so its not 1:1 like the fossil). Over on twitter people started comparing it to DnD Kobolds, leading to the below artwork by Manusuchus (@ mmujicam2000; full body of course highly speculative lmao)

Qianshanosuchus

Following the cataclysm that was KPG, crocs held on and in China we next meet Qianshanosuchus youngi (Young's Qianshan Basin Crocodile). It's another tricky one. While important as being the first crocodyloid from Paleocene China, the material, as you could guess based on the tiny size, is that of a juvenile (I now realize this being kinda ironic given the small but adult croc above). So the phylogeny is hard to nail down and gave different results. Still it could hold significance in our understanding how crocodyloids spread around the world and entered Europe after KPG. Below a quick comparison of the material with my hand.

Coming up a duo of two new species but not new genera, I also didn't really go deep into their publication as with some of the others so I'll try to stay brief

Maomingosuchus acutirostris

Maomingosuchus acutirostris (Acute Snouted Maoming Crocodile) is a new species of the already established genus Maomingosuchus from China. This new species however, differentiated amongst other things by having a pointed, not rounded, premaxilla stems from the Eocene of northern Vietnam. The skull is about 55 cm long giving us a medium sized tomistomines. Like Qianshanosuchus, M. acutirostris could have implications for the dispersal of crocodilians, in this case the spread of tomistomines from Europe to Asia, which the authors suggest happened thrice. That being said it should be noted that, between the two main ideas of what tomistomines are, the paper goes with them being a sister group to crocs and unrelated to modern gharials as Lee and Yates suggest (the later idea like I said I am more drawn towards).

Diplocynodon kochi

Another new species in a familiar genus, Diplocynodon kochi (Koch's Double Dog Tooth) is the latest in a long list of Diplocynodon species, a genus of alligatoroid very prominent in the Paleogene of Europe. This newest species from Transylvania is known from some well preserved skull material and was recovered as being one of the most derived members of its genus. With a size of 1.76 meters it was a medium sized Diplocynodon species and small by our modern standards. What is interesting is that the fossilw as recovered from shallow marine sediments. This is unusual in so far that alligatoroids are not especially known for their salt tolerance. Tho there's exceptions like Deinosuchus, alligators usually don't venture into salt water unlike crocodiles. Still, given the shallow water and the ability of large adult Mississippie Alligators to tolerate brackish water, it might have occasionally entered coastal waters. It is noted that the skull is in such good condition that it couldn't have been transported for a very long time.

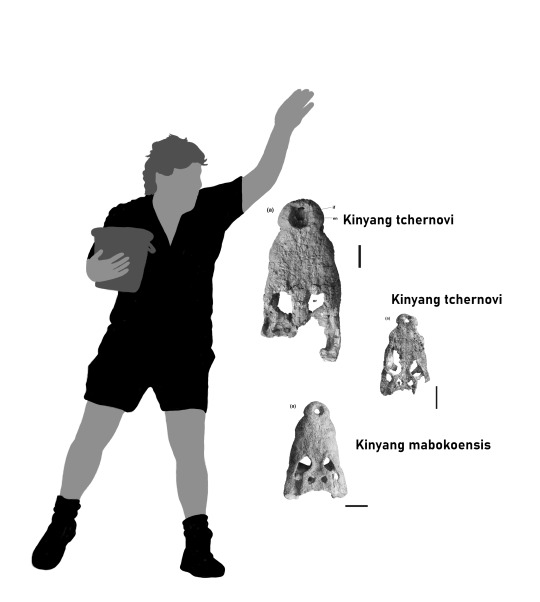

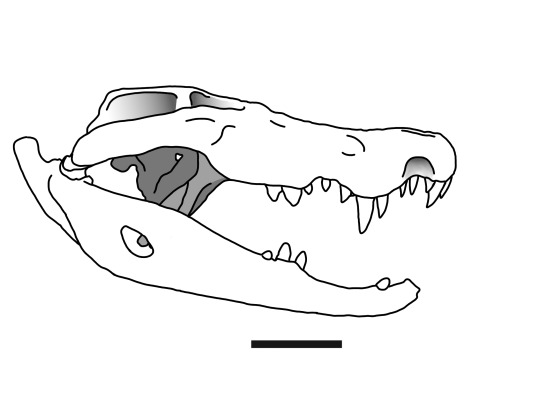

Kinyang

Back to new genera we got Kinyang (derived from various Nilotic terms for crocodile), a genus of "giant" dwarf crocodile from the Miocene of Kenya. Now this guy doesn't just introduce one new species but two: Kinyang mabokoensis (Maboko Island Crocodile) and Kinyang tchernovi (Tchernov's Crocodile). Occuring in western and northern Kenya, Kinyang was a prime example over the prominence osteolaemines (dwarf crocodiles) had in the early Cenozoic prior to the takeover of crocodylines. Kinyang was surprisingly large and had a robust, blunt skull with several traits clearly setting it apart from any modern species. Still there is some clues that could be taken. Given the robust nature and more widened skull rather than V-shaped, its likely that it went after prey as big or even bigger than itself. They appear to have inhabited the shores of lakes located in open forests and woodlands. Alas this might have been their doom too. Osteolaemines are known to build nests made of foliage and with Africa growing increasingly dryer around this point in earths history, both change in prey and environment could have been factors that drove the dwarf crocodiles into the rainforests they inhabit today while the more dry resistant Crocodylus took over their rolle in the grasslands. The first image shows all three known skulls, the second is a quick composite of the cranium and mandible of K. mabokoensis I put together before the third image was published (ironic) by Christopher Brochu.

Almost done, only two more to go.

Sacacosuchus

On the other side of the world, specifically the Sacaco locality of Peru's Pisco Formation (among others) we have Sacacosuchus cordovai (Córdova's Sacaco Crocodile). A medium sized and longirostrine "tomistomine" gharial, here is where we come in conflict between the crocodylid and gavialoid model of what these guys are. Earlier with Maomingosuchus you had the idea that tomistomines were related to crocodylids, well here we have tomistomines being a paraphyletic group leading up to derived gharials. There is some significance to Sacacosuchus for seemingly showing that gharials entered South America on two separate occassions, but imo that's not the coolest thing about it. No instead I prefer to talk about the fact that its not just a marine gharial, living in the coastal waters of the Pacific, but that it coexisted with a second gharial showing perfectly how they specialise in different things. While the contemporary Piscogavialis was notably larger (about 7 meters) it had a very narrow and long snout, better adapted at catching fish. Sacacosuchus meanwhile was only 4.3 meters long, but with much more robust jaws, showing that it was much more of a generalist than its relative. This is well shown in the reconstruction by Javier "Canelita" Herbozo, tho it doesn't show the immense size difference. The third iamge shows Rodolfo Salas-Gismondi with the material and the fourth illustration by Gabriel Ugueto does not feature Sacaco, but the much more gracile Piscogavialis.

Hanyusuchus

The final one, Hanyusuchus sinensis (Han Yu's Crocodile from China) is the youngest crocodile described this year. How young? Well the OLDEST records of the species date to the Chinese Bronze Age, 4.000 BC, while the most recent records indicate that it went extinct in the 15th century. Hanyusuchus is a large tomistomine with a length between 5.43–6.19 meters and, if historical reports are to be believed, a big appetite. Stories tell of large crocodiles in Southern China attacking livestock, deer, boats and even killing humans while other reports suggest that these animals were used to fill moats and fed with prisoners. Despite appearing relatively narrow snouted, people often underestimate just how dangerous such animals could be. Even the modern false gharial has reports of it attacking and eating humans. Unsurprisingly, in addition to spawning some unique folklore (like crocodiles turning into tigers during autumn), this lead to humans attacking and killing these animals in retaliation. Fossils from the Bronze Age bear the clear marks of human attacks with cut marks focused around the animals head and the neck. Given the age of this material humans likely used bronze axes to kill and decapitate Hanyusuchus, drying their heads afterwards. Things didn't get better later in history. Han Yu, poet and politician and namesake of the genus, once demanded that the crocodiles leave the Han River delta before threatening to kill them. Later in history soldiers were sent to kill them in masses to avenge the death of a child. Eventually all of this, coupled with habitat loss, lead to the extinction of Hanyusuchus a mere 600 years ago. The below reconstructions were done by Hikaru Amemiya and Joschua Knüppe respectively.

And that is basically every crocodile officially published in 2022 (I think). Personally, I think its been a fantastic year for Pseudosuchian taxa, with some unique and fascinating additions.

#crocodiles#palaeoblr#mambawakale#hanyusuchus#sacacosuchus#kinyang#qianshanosuchus#eurycephalosuchus#diplocynodon kochi#maomingosuchus acutirostris#titanochampsa#confractosuchus#eptalofosuchus#yanjisuchus#prehistory#paleontology#pseudosuchia#steve irwin for scale#2022

174 notes

·

View notes

Video

instagram

annscarlett 🐚🐙🌍⏳ A recently discovered Early Cretaceous (early late Albian) dinosaur tracksite at Parede beach (Cascais, Portugal) reveals evidence of dinoturbation and at least two sauropod trackways. One of these trackways can be classified as narrow-gauge, which represents unique evidence in the Albian of the Iberian Peninsula and provides for the improvement of knowledge of this kind of trackway and its probable trackmaker, in an age when the sauropod record is scarce. These dinosaur tracks are preserved on the upper surface of a marly limestone bed that belongs to the Galé Formation (Água Doce Member, middle to lower upper Albian). The study of thin-sections of the beds in the Parede section has revealed a microfacies composed of foraminifers, radiolarians, ostracods, corals, bivalves, gastropods, and echinoids in a mainly wackestone texture with biomicritic matrix. These assemblages match with the lithofacies, marine molluscs, echinids, and ichnofossils sampled from the section and indicate a shallow marine, inner shelf palaeoenvironment with a shallowing-upward trend. The biofacies and the sequence analysis are compatible with the early late Albian age attributed to the tracksite. These tracks and the moderate dinoturbation index indicate sauropod activity in this palaeoenvironment. Titanosaurs can be dismissed as possible trackmakers on the basis of the narrow-gauge trackway, and probably by the kidney-shaped manus morphology and the pes-dominated configuration of the trackway. Narrow-gauge sauropod trackways have been positively associated with coastal palaeoenvironments, and the Parede tracksite supports this interpretation. In addition, this tracksite adds new data about the presence of sauropod pes-dominated trackways in cohesive substrates. As the Portuguese Cretaceous sauropod osteological remains are very scarce, the Parede tracksite yields new and relevant evidence of these dinosaurs.

#Fossil#Portugal#Fossilfriday#Geology#Dinosaur#sauropod#Footprint#Limestone#Albian#cretaceous#research#shelf#The earth story#video#instagram

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Is a genus of dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaur with one described species, Deinonychus antirrhopus. This species, which could grow up to 3.4 meters (11 ft) long, lived during the early Cretaceous Period, about 115–108 million years ago (from the mid-Aptian to early Albian stages). Fossils have been recovered from the U.S. states of Montana, Utah, Wyoming, and Oklahoma, in rocks of the Cloverly Formation, Cedar Mountain Formation and Antlers Formation, though teeth that may belong to Deinonychus have been found much farther east in Maryland. Paleontologist John Ostrom's study of Deinonychus in the late 1960s revolutionized the way scientists thought about dinosaurs, leading to the "dinosaur renaissance" and igniting the debate on whether dinosaurs were warm-blooded or cold-blooded. Before this, the popular conception of dinosaurs had been one of plodding, reptilian giants. Ostrom noted the small body, sleek, horizontal posture, ratite-like spine, and especially the enlarged raptorial claws on the feet, which suggested an active, agile predator. "Terrible claw" refers to the unusually large, sickle-shaped talon on the second toe of each hind foot. The fossil YPM 5205 preserves a large, strongly curved ungual. In life, archosaurs have a horny sheath over this bone, which extends the length. Ostrom looked at crocodile and bird claws and reconstructed the claw for YPM 5205 as over 120 millimetres (4.7 in) long.[1] The species name antirrhopus means "counter balance", which refers to Ostrom's idea about the function of the tail. As in other dromaeosaurids, the tail vertebrae have a series of ossified tendons and super-elongated bone processes. These features seemed to make the tail into a stiff counterbalance, but a fossil of the very closely related Velociraptor mongoliensis (IGM 100/986) has an articulated tail skeleton that is curved laterally in a long S-shape. This suggests that, in life, the tail could bend to the sides with a high degree of flexibility. In both the Cloverly and Antlers formations, Deinonychus remains have been found closely associated with those of the ornithopod Tenontosaurus. Teeth discovered associated with Tenontosaurus specimens imply they were hunted, or at least scavenged upon, by Deinonychus.

Art (c) reneg661

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is there any evidence that can explain why the Stegosaurs began declining after the Jurassic & eventually became extinct by the mid/late-ish Cretaceous? Could competition from their Thyreophoran relatives, the Ankylosaurs, possibly have been a contributing factor? What was the last Stegosaur?

It has been observed that the decline of stegosaurs appears to have coincided with the decline of cycads, so it’s possible that the two were linked in some way, but teasing out the nature of long-term ecological interactions from the fossil record is pretty difficult. The youngest known uncontroversial stegosaur is probably Mongolostegus from the Aptian–Albian of Mongolia, though there are reportedly undescribed Coniacian stegosaur remains known from India and possible stegosaur-like tracks as young as the Maastrichtian.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dimorpholites Fossil Ammonite Cretaceous Folkestone UK | Gault Clay Middle Albian Genuine Specimen with Certificate

This listing features a genuine Dimorpholites ammonite fossil, collected from the classic Gault Clay Formation at Folkestone, Kent, United Kingdom. This fossil dates to the Middle Albian Stage of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 105 million years ago, when the region was part of a warm, shallow epicontinental sea rich in marine life.

The exact specimen shown in the photos is the item you will receive, carefully chosen for its quality and distinct morphology. This ammonite is ideal for fossil collectors, educators, and lovers of natural history.

Geological & Palaeontological Details:

Genus: Dimorpholites (species not specified)

Fossil Type: Ammonite

Family: Hoplitidae

Superfamily: Hoplitoidea

Order: Ammonitida

Geological Period: Cretaceous

Stage: Middle Albian (approx. 107–104 million years ago)

Formation: Gault Clay

Location: Folkestone, Kent, UK

Biozone: Commonly associated with the Euhoplites lautus Zone, and adjacent ammonite-bearing Middle Albian intervals

Depositional Environment: Low-energy offshore marine environment with clay-rich sediments, providing ideal conditions for the preservation of ammonite shells and fine morphological features

Morphology & Features:

Dimorpholites is known for exhibiting sexual dimorphism in its shell forms, with macroconchs (likely female) and microconchs (likely male) showing distinct size and ornamentation differences

Typically shows falcoid ribbing, compressed to subcircular whorl sections, and occasionally ventrolateral tubercles

Sutures and rib spacing may vary between dimorphs, making these ammonites particularly interesting for collectors and researchers alike

Notability: Dimorpholites is an important genus in Albian ammonite biostratigraphy, aiding in the identification and correlation of Middle Albian marine deposits. Specimens from the Gault Clay of Folkestone are especially valued due to their well-preserved detail and clear stratigraphic context.

Additional Details:

All our fossils are 100% genuine specimens

Includes a Certificate of Authenticity

The photo shows the exact fossil for sale

Scale cube = 1cm – see images for full sizing reference

This Dimorpholites ammonite is a fine representative of Cretaceous marine life from one of Britain’s most iconic fossil localities. A highly collectible and display-worthy specimen for any fossil enthusiast or palaeontology lover.

#Dimorpholites#fossil ammonite#Gault Clay#Middle Albian#Cretaceous ammonite#Folkestone fossil#Kent ammonite#UK fossils#British ammonite#genuine fossil#ammonite with certificate#ammonite display specimen#collector ammonite#ammonite cephalopod#Albian fossil#marine fossil#natural history fossil

0 notes

Text

Yuanyanglong bainian Hao et al., 2024 (new genus and species)

(Partial skeletons of Yuanyanglong bainian, from Hao et al., 2024)

Meaning of name: Yuanyanglong = mandarin duck [a symbol of lifelong monogamy, referring to the fact that two individuals were preserved together] dragon [in Chinese]; bainian = one hundred years [in Chinese, commemorating the fact that Oviraptor and Chirostenotes, two of the first oviraptorosaurs to be scientifically described, were named 100 years ago in 1924]

Age: Early Cretaceous (Aptian–Albian)

Where found: Miaogou Formation, Inner Mongolia, China

How much is known: Partial skeletons of two individuals, together including a partial skull, parts of the limbs, and some vertebrae.

Notes: Yuanyanglong was an oviraptorosaur, a group of bird-like theropods with short and often toothless skulls. It had relatively long legs (and especially shins) for its size. Although long legs are often an adaptation for fast running, the pelvis of Yuanyanglong does not have much space for the attachment of muscles that pull the hindlimbs back, leading its describers to suggest that it may have used its long legs for wading through water instead.

Both known specimens of Yuanyanglong were preserved with clusters of pebbles in their body cavity (though in one specimen, these pebbles were accidentally removed during fossil preparation), indicating that it probably used gizzard stones to grind up its food. Gizzard stones have also been found in the slightly older oviraptorosaur Caudipteryx.

Yuanyanglong is estimated to have weighed around 12 kg, making it larger than earlier oviraptorosaurs such as Caudipteryx, but smaller than many Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaurs.

Reference: Hao, M., Z. Li, Z. Wang, S. Wang, F. Ma, Qinggele, J.L. King, R. Pei, Q. Zhao, and X. Xu. 2024. A new oviraptorosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Miaogou Formation of western Inner Mongolia, China. Cretaceous Research advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2024.106023

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Mymaridae, commonly known as fairyflies or fairy wasps, are a family of chalcid wasps found in temperate and tropical regions throughout the world. The photos above are of the Mymar genus of fairyflies.

Fairyflies are very tiny insects. They generally range from 0.5 to 1.0 mm (0.020 to 0.039 in) long. This family includes include the world's smallest known insect, Dicopomorpha echmepterygis, with a body length of only 0.139 mm (smaller than certain species of Paramecium and amoeba, which are single-celled organisms)

The fossil record of fairyflies extends from at least the Albian age, about 100 million years ago, of the Early Cretaceous.

670 notes

·

View notes

Text

Acrocanthosaurus

Acrocanthosaurus atokensis [ak-ro-KAN-tho-SAWR-us] [AT-oh-KEN-zis]

“High-spined Lizard”

Acrocanthosaurus lived in what is now North America during the Aptian and Albian stages of the Early Cretaceous. It’s fossil remains are found mainly in Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming, although teeth have been found as far as Maryland.

Acrocanthosaurus was among the largest known theropods known to exist, being related to Carcharodontosaurus and Giganotosaurus. The largest known specimen estimated to have been 11.5 meters (38 feet) from nose to tail and weighed 5.7 to 6.2 metric tons.

Acrocanthosaurus was a theropod dinosaur or a bipedal apex predator. It is best known for its high neural spines on its vertebrae. This ridge most likely served as an anchor point for large muscles on its neck and back, although it is often represented as a narrow and colourful sail.

Acrocanthosaurus was the largest theropod in its ecosystem and preyed on sauropods, ornithopods, and ankylosaurids. It had a strong neck and moderately sized arms with three hooked claws on each. Its skull was 1.3 meters (4.3 feet) in length and was long and narrow like most allosauroids.

Acrocanthosaurus is one of my favourite dinosaurs, if not my most. I love this thing and wish it was more popular and well known. I personally prefer giving it a more defined and narrow sail as opposed to a smaller fatter hump, as I feel it makes it appear more distinct compared to a Giga or Charchar. I also, as I do with most of my theropods, give it a small vague amount of fluff or fur-like fuzz on its body, as you can see on its elbows, where it doesn’t really start or end. That’s not meant to imply its completely covered in fur, just that it has some fuff, and is covered in hide rather than scales.

Sole Source : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acrocanthosaurus

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

no no “and scene”

Sea turtles (superfamily Chelonioidea), sometimes called marine turtles,[3] are reptiles of the order Testudines and of the suborder Cryptodira. The seven existing species of sea turtles are the flatback, green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerhead, Kemp's ridley, and olive ridley sea turtles.[4] All six of the sea turtle species present in US waters (all of those listed above except the flatback) are listed as endangered and/or threatened under the Endangered Species Act.[5] The seventh sea turtle species is the flatback, which exists in the waters of Australia, Papua New Guinea and Indonesia.[5] Sea turtles can be separated into the categories of hard-shelled (cheloniid) and leathery-shelled (dermochelyid).[6] There is only one dermochelyid species which is the leatherback sea turtle.[6]

For each of the seven types of sea turtles, females and males are the same size; there is no sexual dimorphism.[7]

In general, sea turtles have a more fusiform body plan than their terrestrial or freshwater counterparts. This tapering at both ends reduces volume and means that sea turtles cannot retract their head and limbs into their shells for protection, unlike many other turtles and tortoises.[8] However, the streamlined body plan reduces friction and drag in the water and allows sea turtles to swim more easily and swiftly.

The leatherback sea turtle is the largest sea turtle, measuring 2–3 m (6–9 ft) in length, 1–1.5 m (3–5 ft) in width, and weighing up to 700 kg (1500 lb). Other sea turtle species are smaller, being mostly 60–120 cm (2–4 ft) long and proportionally narrower.[9]

The skulls of sea turtles have cheek regions that are enclosed in bone.[10][11] Although this condition appears to resemble that found in the earliest known fossil reptiles (anapsids), it is possible it is a more recently evolved trait in sea turtles, placing them outside the anapsids.

Sea turtles, along with other turtles and tortoises, are part of the order Testudines. All species except the leatherback sea turtle are in the family Cheloniidae. The superfamily name Chelonioidea and family name Cheloniidae are based on the Ancient Greek word for tortoise: χελώνη (khelone).[13] The leatherback sea turtle is the only extant member of the family Dermochelyidae.

Fossil evidence of marine turtles goes back to the Late Jurassic (150 million years ago) with genera such as Plesiochelys, from Europe. In Africa, the first marine turtle is Angolachelys, from the Turonian of Angola.[14] A lineage of unrelated marine testudines, the pleurodire (side-necked) bothremydids, also survived well into the Cenozoic. Other pleurodires are also thought to have lived at sea, such as Araripemys[15] and extinct pelomedusids.[16] Modern sea turtles are not descended from more than one of the groups of sea-going turtles that have existed in the past; they instead constitute a single radiation that became distinct from all other turtles at least 110 million years ago.[17][18][19] Their closest extant relatives are in fact the snapping turtles (Chelydridae), musk turtles (Kinosternidae), and hickatee (Dermatemyidae) of the Americas, which alongside the sea turtles constitute the clade Americhelydia.[20]

The oldest possible representative of the lineage (Panchelonioidea) leading to modern sea turtles was possibly Desmatochelys padillaifrom the Early Cretaceous. Desmatochelys was a protostegid, a lineage that would later give rise to some very large species but went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous. Presently thought to be outside the crown group that contains modern sea turtles (Chelonioidea), the exact relationships of protostegids to modern sea turtles are still debated due to their primitive morphology; they may be the sister group to the Chelonoidea, or an unrelated turtle lineage that convergently evolved similar adaptations.[21][22] The earliest "true" sea turtle that is known from fossils is Nichollsemys from the Early Cretaceous (Albian) of Canada. In 2022, the giant fossil species Leviathanochelys was described from Spain. This species inhabited the oceans covering Europe in the Late Cretaceous and rivaled the concurrent giant protostegids such as Archelon and Protostega as one of the largest turtles to ever exist. Unlike the protostegids, which have an uncertain relationship to modern sea turtles, Leviathanochelys is thought to be a true sea turtle of the superfamily Chelonioidea.[23]

Sea turtles' limbs and brains have evolved to adapt to their diets. Their limbs originally evolved for locomotion, but more recently evolved to aid them in feeding. They use their limbs to hold, swipe, and forage their food. This helps them eat more efficiently.[24][25]

PSA

avoid conforming to traditional gender norms by avoiding this common palette:

try using these palettes instead!!

190K notes

·

View notes

Text

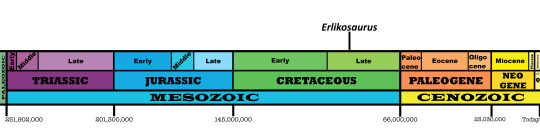

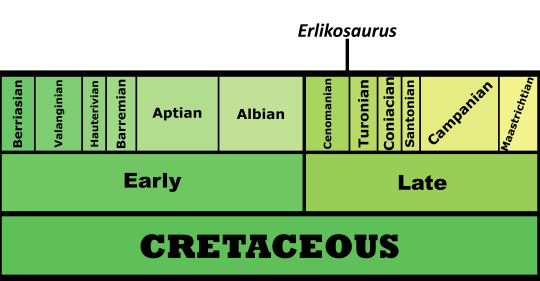

Erlikosaurus andrewsi

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Demon-King Reptile

First Described By: Perle, 1980

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Therizinosauria, THerizinosauridea, Therizinosauridae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: About 90 million years ago, in the Turonian of the Late Cretaceous

Erlikosaurus is found in the Bayan Shireh Formation in Dornogovi, Mongolia

Physical Description: Erlikosaurus was a kind of Therizinosaur, the very bulky feathered dinosaurs with long, pointed claws extending from their hands. They’re weird in other ways, too - they have backward-facing hip bones like those of birds and Ornithischians, and giant pot-bellies to let them digest large amounts of plant material. As such, they stood up almost as vertical as people do - rather than horizontally like… all other dinosaurs. Erlikosaurus had a long neck, a squat body, short legs and a short tail; while its arms were normal length, it also had very long curved claws, like other therizinosaurs. It had very large and long nostrils for a therizinosaur, and a very high number of teeth compared to its relatives. Interestingly enough, therizinosaurs like Erlikosaurus also had swollen, pneumatized braincases, which allowed them to be lighter weight and potentially cool off quicker. Erlikosaurus also, unlike other Therizinosaurs, ahd long and slender claws on its feet. It may have been around six meters long. Like other therizinosaurs, it would have been covered with feathers all over its body, and potentially had very primitive long feathers on its arms like wings.

Diet: Erlikosaurus, like other therizinosaurs, was an herbivore.

By Jack Wood

Behavior: Erlikosaurus is a fascinating dinosaur behavior-wise because we actually have a decent number of scans of its brain, which may teach us aspects of its behavior. Erlikosaurus had a very well developed sense of smell, hearing, and balanced, which means that it retained a lot of the traits of carnivorous theropods - and probably used them to its advantage as an herbivore. It also probably was able to sense oncoming predators well and have complex social behavior. The range of its mouth, however, was narrower than that of its close carnivorous relatives - indicating that herbivorous dinosaurs, much like herbivorous mammals, had smaller mouth gapes than carnivores. With complicated social behavior, long claws, and good senses, Erlikosaurus would have been incredibly paranoid - and dangerous - ready to fend off anyone that would have threatened their family groups with those long scythe claws. As a social dinosaur, Erlikosaurus would have probably taken care of its young, and been warm blooded. The scythe claws, when not used in defense, would have been helpful in gathering plants down from the trees, much like with sloths today.

Ecosystem: The Bayan Shireh Environment was one of many such ecosystems found in the mid to late Cretaceous, showcasing a wide variety of animals that were almost - but not quite - like their latest Cretaceous counterparts. Here was a braided river environment, going through season wet and dry seasons as the mud and sand interchanged from one another leading to a variety of rock types and depositional environments. There were many water plants and flowering plants lining the shores, giving it a lush and green feel for at least part of the year - and giving Erlikosaurus something to eat! There were also fish, molluscs, the mammal Tsagandelta, and turtles making frequent appearances in the environment. Unnamed crocodylian relatives and Azhdarchid pterosaurs were present, but most of the charismatic animals present were other dinosaurs. Erlikosaurus wasn’t the only Therizinosaur, and also lived with Segnosaurus and Enigmosaurus. The very large, weird, and lopsided sauropod Erketu graced the treetops, slowly foraging on food, while the much smaller Ornithomimosaur Garudimimus scurried about between them all. Ankylosaurs went absolutely wild here, represented by Talarurus, Maleevus, and Tsagantegia. There were two small bipedal Ceratopsians, Graciliceratops and Microceratus, and the early hadrosauroid Gobihadros. There was also a mystery dinosaur, Amtosaurus, which has no affinity beyond “Ornithischian” at this point in time. As for predators, there was the very large raptor Achillobator and the small tyrannosaur Alectrosaurus - both similar in size to one another, and both giant dangers to the roaming herds of Erlikosaurus!

By Scott Reid

Other: Erlikosaurus was a very advanced therizinosaur, similar to later members of the group like Therizinosaurus rather than Early Cretaceous varieties. As such, it shows that the more classic therizinosaur body shape was around by the “mid” Cretaceous. In addition, it may or may not be the same animal as the other therizinosaurs found in its home - more research is needed to determine as such.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Averianov, A. O. 2007. Theropod dinosaurs from Late Cretaceous deposits in the northeastern Aral Sea region, Kazakhstan. Cretaceous Research 28:532-544

Barsbold, R., and A. Perle. 1980. Segnosauria, a new infraorder of carnivorous dinosaurs. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 25(2):187-195

Barsbold, R. 1981. Bezzubyye khishchnyye dinozavry Mongolii [Toothless carnivorous dinosaurs of Mongolia]. Sovmestnaia Sovetsko-Mongol’skaia Paleontologicheskaia Ekspeditsiia Trudy 15:28-39

Barsbold, R. 1983. Khishchnye dinosavry mela Mongoliy [Carnivorous dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of Mongolia]. Transactions of the Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition 19:1-117

Barsbold, R. 1997. Mongolian dinosaurs. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 447-450

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Clark, J. M., T. Maryanska, and R. Barsbold. 2004. Therizinosauroidea. In D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, and H. Osmolska (eds.), The Dinosauria (second edition). University of California Press, Berkeley 151-164

Clark, J. M., M. A. Norell, L. M. Chiappe and A. Perle. 1995. The phylogenetic relationships of "segnosaurs" (Theropoda, Therizinosauridae). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15(3, supl.):24A

Clark, J. M., A. Perle, and M. A. Norell. 1993. The skull of the segnosaurian dinosaur Erlikosaurus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 13(3, suppl.):30A-31A

Clark, J. M., A. Perle, and M. A. Norell. 1994. The skull of Erlicosaurus andrewsi, a Late Cretaceous "segnosaur" (Theropoda: Therizinosauridae) from Mongolia. American Museum Novitates 3115:1-39

Currie, P. J. 1992. Saurischian dinosaurs of the Late Cretaceous of Asia and North America. In N. J. Mateer, P.-j. Chen (eds.), Aspects of Nonmarine Cretaceous Geology. China Ocean Press, Beijing 237-249

Currie, P. J., and D. A. Eberth. 1993. Palaeontology, sedimentology and palaeoecology of the Iren Dabasu Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Inner Mongolia, People's Republic of China. Cretaceous Research 14:127-144

Currie, P. J. 2000. Theropods from the Cretaceous of Mongolia. In M. J. Benton, M. A. Shishkin, D. M. Unwin, & E N. Kurichkin (eds.), The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia 434-455

Danilov, I. G. 1999. A new linholmemydid genus (Testudines: Lindholmemydidae) from the mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan. Russian Journal of Herpetology 6(1):63-71

Eberth, D. A., P. J. Currie, D. B. Brinkman, M. J. Ryan, D. R. Braman, J. D. Gardner, V. D. Lam, D. N. Spivak, and A. G. Neuman. 2001. Alberta's dinosaurs and other fossil vertebrates: Judith River and Edmonton groups (Campanian-Maastrichtian). In C. L. Hill (ed), Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, 61st Annual Meeting, Bozeman. Guidebook for the Field Trips: Mesozoic and Cenozoic Paleontology in the Western Plains and Rocky Mountains, Museum of the Rockies Occasional Paper 3:49-75

"Erlikosaurus." In: Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B. The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 142.

Gianechini, F. A., P. J. Makovicky, and S. Apesteguía. 2011. The teeth of the unenlagiine theropod Buitreraptor from the Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina, and the unusual dentition of the Gondwanan dromaeosaurids. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 56(2):279-290

Hendrickx, C., and O. Mateus. 2014. Abelisauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal and dentition-based phylogeny as a contribution for the indentification of isolated theropod teeth. Zootaxa 3759(1):1-74

Hicks, J.F., Brinkman, D.L., Nichols, D.J., and Watabe, M. (1999). "Paleomagnetic and palynological analyses of Albian to Santonian strata at Bayn Shireh, Burkhant, and Khuren Dukh, eastern Gobi Desert, Mongolia." Cretaceous Research, 20(6): 829-850.

Jerzykiewicz, T. and Russell, D.A. (1991). "Late Mesozoic stratigraphy and vertebrates of the Gobi Basin." Cretaceous Research, 12(4): 345-377.

Kirkland, J. I., D. K. Smith, and D. G. Wolfe. 2005. Holotype braincase of Nothronychus mckinleyi Kirkland and Wolfe 2001 (Theropoda; Therizinosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous (Turonian) of west-central New Mexico. In K. Carpenter (ed.), The Carnivorous Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 87-96

Lautenschlager, Stephan; Rayfield, Emily J.; Altangerel Perle; Zanno, Lindsay E.; Witmer, Lawrence M. (2012). "The Endocranial Anatomy of Therizinosauria and Its Implications for Sensory and Cognitive Function". PLoS ONE. 7 (12): e52289.

Lautenschlager, Stephan (November 4, 2015). "Estimating cranial musculoskeletal constraints in theropod dinosaurs". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (11): 150495.

Li, D., C. Peng, H. You, M. C. Lamanna, J. D. Harris, K. J. Lacovara, and J. Zhang. 2007. A large therizinosauroid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Early Cretaceous of northwestern China. Acta Geologica Sinica 81(4):539-549

Mader, B. J., and R. L. Bradley. 1989. A redescription and revised diagnosis of the syntypes of the Mongolian tyrannosaur Alectrosaurus olseni. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 9(1):41-55

Makovicky, P. J., and M. A. Norell. 1998. A partial ornithomimid braincase from Ukhaa Tolgod (Upper Cretaceous, Mongolia). American Museum Novitates 3247:1-16

Nessov, L. A. 1995. Dinozavri severnoi Yevrazii: Novye dannye o sostave kompleksov, ekologii i paleobiogeografii [Dinosaurs of northern Eurasia: new data about assemblages, ecology, and paleobiogeography]. Institute for Scientific Research on the Earth's Crust, St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg 1-156

Paul, G. S. 1984. The segnosaurian dinosaurs: relics of the prosauropod-ornithischian transition?. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 4(4):507-515

Perle, A. 1977. O pervoy nakhodke Alektrozavra (Tyrannosauridae, Theropoda) iz pozdnego Mela Mongolii [On the first discovery of Alectrosaurus (Tyrannosauridae, Theropoda) in the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia]. Shinzhlekh Ukhaany Akademi Geologiin Khureelen 3(3):104-113

Perle, A. 1981. Noviy segnozavrid iz verchnego mela Mongolii [A new segnosaurid from Mongolia]. Trudy - Sovmestnaya Sovetsko-Mongol'skaya Paleontologicheskaya Ekspeditsiya 15:50-59

Pu, H., Y. Kobayashi, J. Lu, Y. Wu, H. Chang, J. Zhang, and S. Jia. 2013. An unusual basal therizinosaur with an ornithischian dental arrangement from northeastern China. PLoS ONE 8(5):e63423

Qian, M.-p., Z.-y. Zhang, Y. Jiang, Y.-g. Jiang, Y.-j. Zhang, R. Chen, and G.-f. Xing. 2012. [Cretaceous therizinosaurs in Zhejiang of eastern China]. Journal of Geology 36(4):337-348

Rauhut, O. W. M. 2003. The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs. Special Papers in Palaeontology 69:1-213

Russell, D. A. 1997. Therizinosauria. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 729-730

Russell, D. A., and Z.-M. Dong. 1994. The affinities of a new theropod from the Alxa Desert, Inner Mongolia, People's Republic of China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 30(10-11):2107-2127

Senter, P., J. I. Kirkland, and D. D. DeBlieux. 2012. Martharaptor greenriverensis, a new theropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Utah. PLoS ONE 7(8):e43911:1-12

Sereno, P. C. 1998. A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with application to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 210(1):41-83

Sues, H.-D. 1997. On Chirostenotes, a Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from western North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 17(4):698-716

Sukhanov, V. B., and P. Narmandakh. 1975. Cherepakhi gruppy Basilemys (Chelonia, Dermatemydidae) v Asiy [New turtles from the Basilemys group (Chelonia, Dermatemydidae) in Asia]. In N. Kramarenko, B. Luwsandansan, Yu. Voronin, R. Barsbold, A. Rozhdestvensky (eds.), Iskopaemaya Fauna I Flora Mongolii [Fossil Flora and Fauna of Mongolia]. Sovmestnaya Sovetsko-Mongol'skaya Paleontologicheskaya Ekspeditsiya, Trudy [The Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition, Transactions] 2:94-101

Tsuihiji, T., M. Watabe, R. Barsbold and K. Tsogtbaatar. 2015. A gigantic caenagnathid oviraptorosaurian (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Gobi Desert, Mongolia. Cretaceous Research 56(1):60-65

Turner, A. H., S. H. Hwang, and M. A. Norell. 2007. A small derived theropod from Öösh, Early Cretaceous, Baykhangor Mongolia. American Museum Novitates 3557:1-27

Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp.

Xu, X., Z.-H. Zhang, P. C. Sereno, X.-J. Zhao, X.-W. Kuang, J. Han, and L. Tan. 2002. A new therizinosauroid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Iren Dabasu Formation of Nei Mongol. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 40(3):228-240

Varricchio, D. J. 1997. Troodontidae. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 749-754

Zanno, L. 2004. The pectoral girdle and forelimb of a primitive therizinosauroid (Theropoda: Maniraptora): new information on the phylogenetics and evolution of therizinosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24(3, suppl.):134A

Zanno, L. E. 2006. The pectoral girdle and forelimb of the primitive therizinosauroid Falcarius utahensis (Theropoda, Maniraptora): analyzing evolutionary trends within Therizinosauroidea. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26(3):636-650

Zanno, Lindsay E. (2010). "A taxonomic and phylogenetic re-evaluation of Therizinosauria (Dinosauria: Maniraptora)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (4): 503–543.

Zhang, X.-H., X. Xu, X.-J. Zhao, P. C. Sereno, X.-W. Kuang and L. Tan. 2001. A long-necked therizinosauroid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Iren Dabasu Formation of Nei Mongol, People's Republic of China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 39(4):282-290

#erlikosaurus#erlikosaurus andrewsi#dinosaur#therizinosaur#feathered dinosaurs#factfile#palaeoblr#feathered dinosaur#maniraptoran#Cretaceous#Eurasia#Herbivore#Theropod Thursday#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

324 notes

·

View notes