#Bouvines

Text

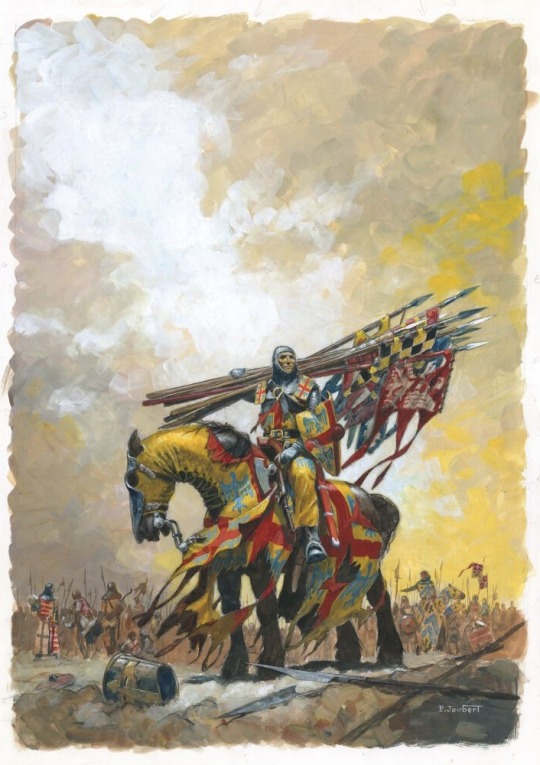

Chevalier de Montmorency by Pierre Joubert

#battle of bouvines#montmorency#knight#knights#medieval#middle ages#art#pierre joubert#history#france#europe#heraldry#banners#european#french#bouvines#matthieu ii de montmorency#matthew ii of montmorency#holy roman empire#flanders#angevin empire#battle#war

637 notes

·

View notes

Photo

27 juillet 1214 : bataille de Bouvines et victoire des Français sur l’empereur Otton IV allié des Anglais ➽ http://bit.ly/Bataille-de-Bouvines Opposant les troupes de Philippe Auguste à celles du Saint-Empire romain germanique, allié du roi d’Angleterre Jean sans Terre qui aspire à se venger de la perte de la Normandie, cette bataille, au cours de laquelle le roi de France est jeté à terre par des fantassins armés de crochets, marque le début du déclin de la féodalité

#CeJourLà#27Juillet#Bataille#Bouvines#Roi#France#Philippe#Auguste#Otton#SaintEmpire#Romain#Germanique#Angleterre#JeanSansTerre#Troupes#Armées#Normandie#histoire#france#history#passé#past#français#french#news#événement#newsfromthepast

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is one of my favorite Bad TLIW takes of all time just the sheer irrelevancy of it XD

#TLIW#the lion in winter#Newsflash if ur a successful and crafty adult politician it's impossible to get molested as a teen A+ logic#what does Bouvines have to do with any of this!!!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

mother likes taking pictures of me getting excited and pointing at things in museums

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

namedropped richard lionheart

#it was wrt otto since we're nearing bouvines time. i personally can't wait for bouvines time.#the great infidel

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippe Auguste

The Capetian monarchy was an institution, with traditions and restrictions. But the personal element in the medieval period always remained a significant factor. To what extent the government of any individual king was personal is not easy to determine. In general it is true that counsellors could advise, but could not normally decide policy. Others were there to obey the will of the monarch, perhaps to help form it, but not to take over from it. Philip's views were shaped by many influences: by observing his father's work, by his father's advice, by his own education, by the advice he received from counsellors, by the experience of governing, by the views of churchmen, theologians, popes and fellow rulers, but in the end they were his views and could be imposed to the extent of the power of the monarchy at the time. Philip's court and government reflected his own personality. Gerald of Wales pointed out its contrasts with the Plantagenet court, the French king's being more sober as we have seen, more quiet in tone, more proper, with swearing forbidden. Philip brought about significant changes: less reliance on the magnates, a lesser role for his family; a greater place for the selected dose counsellors and for relatively humble knights.

It has been suggested that Philip's intellectual gifts were 'modest', which, although direct evidence is not easily available, seems to conflict with what we know about the king's abilities. He was able to deal with the bright men around him, such as Peter the Chanter. He was able to supervise governmental development and the administration, which needed a considerable grasp of accounting as well as a degree of literacy. His ability to deal with the papacy reveals a clear understanding of legal argument and his rights, and a firm determination to protect them. He was rarely outmanoeuvred by even the cleverest of his opponents. Philip went to war as any leader of his period would, but he was more prepared than most to seek and make peace.

Rigord said that Philip's aim was 'to deliver the weak from the tyranny of the strong', and that 'his first triumph is to see peace re-established'. His tolerance and mild temper puzzled the aggressive Bertran de Born, who thought the French needed a leader and had not found one in Philip, who did not become angry. Bertran preferred the attitude of Richard the Lionheart, for whom 'peace and truce have never been noble'. For Bertran it was a sneer to suggest that Philip liked peace even more than the noted diplomat Archbishop Peter of Tarentais. Bertran had cause to regret his underestimation of Philip, when the king later used his authority to replace Bertran as lord of Hautefort. No doubt that act was executed on the advice of counsellors, and Bertran could further nurse his belief that Philip was 'badly advised and worse guided'.

Philip did in fact at times lose his temper, but usually with some point, as when he chopped down the elm on the Norman border, declaring by actions rather than words that he no longer accepted the Plantagenet stance on their rights to bring the king to the edge of their territories before they would hold discussions. Nor were his diplomatic activities always appreciated by his enemies. He could manoeuvre and manipulate with the best of them; he was the 'sower of discord' according to one English chronicler. To take just one example of his methods: in the conquest of Normandy he knew that Rouen was the key, which afterwards he would need to govern. Therefore he did not simply crush Rouen, and chose to discuss with the leading citizens what they would gain from surrender. If allowed in, he promised: 'I will prove a kind and just master to you.' In modern times he has been called 'a statesman of the first water', 'the first royal statesman in French history' ; it is a reputation which in this country we have somehow failed to recognize.

[..]

Philip was generally modest and unassuming, as we have seen in contrast to Richard the Lionheart both in Sicily and in the Holy Land. Bertran de Born thought the French king presented his deeds in tin-plate rather than in gilt. But Philip was aware of the need to present a regal figure, dignified if not flamboyant: a public face of modesty but a recognition of his own powers. The scene painted by Mouskes of Philip entering a church and praying: 'I am but a man, as you are, but I am king of France', has a deep truth to it. There is also a story of Peter the Chanter telling Philip what were the attributes of an ideal sovereign; Philip replied that he should be contented with the king that he had.

The efforts to show his connection back to Charlemagne demonstrate Philip's effort to bolster the Capetian position. His mother, Adela, and his first wife, Isabella of Hainault, both claimed descent from Charlemagne. His natural son was named Peter Charlot, after the great emperor. And the Carolingian claim seems to have become generally accepted. Innocent III declared: 'it is common knowledge that the king of France is descended from the lineage of Charlemagne'. No doubt there was some weakness in the argument, but William the Breton refers to him as 'the descendant of Charlemagne', and the Welshman Gerald believed that Philip aimed to restore the monarchy to 'the greatness which it had in the time of Charlemagne'.

Philip wished to present an imperial image of French monarchy, hence the use of an eagle on his seal, the label 'Augustus' applied by Rigord, his sister's marriage to two Byzantine emperors, and the raising to the Latin imperial throne of two of his brothers-in-law. The same point was being emphasized when the sword of Charlemagne had been brandished at Philip' s coronation ceremony. As one of the Parisian masters wrote in 1210: 'the king is emperor in his realm'. The royal family was being distanced from other families, however noble; royal power was being set above noble power. It was not just a question of wealth and lands, but of the nature of monarchy, its prestige, its religious and mystical significance. The claimed association with Charlemagne, by the twelfth century a powerful figure in legend as well as a great historical emperor, was an important part of this process.

Philip was a tough-minded individual, he would not otherwise have been such a great king. Those who had experience of dealings with Louis VII found Philip a much harder opponent with more steel in his character. He had tremendous determination, and strong views on basic policies. Before his father's death, while still a teenager, Philip was prepared to rule, issuing charters without his father's consent, reacting against some of his father's policies. Before long he threw off the shackles of his mother and her powerful family, and soon afterwards of the count of Flanders. The English chronicler Howden thought he did it because he 'despised and hated all whom he knew to be familiar friends of his father', which seems a distortion, but at least underlines the point that Philip was of independent mind from the first.

Philip preferred his close counsellors to be lesser men who accepted their subordinate role without question. We may be clear that his policy expressed his own views. There was an encounter at one of the conferences between Philip and King John which occurred between Boutavent and Gaillon, when the two kings were 'face to face for an hour, no one except themselves being within hearing', a brief comment but one which allows a sudden and vivid insight into the personal nature of thirteenth-century diplomacy.

Of course Philip took counsel, and made a point of doing so, but he was too independent a man to be dominated by another. And though inclined to prefer diplomatic solutions, he was a good enough warrior to win respect; as William the Breton said 'his arm was powerful in the use of weapons'. Bouvines was the most important battle of the age, and Philip was the victor. Where the loss of documentary evidence from the earlier period often makes it impossible to be certain that Philip was the innovator or the initiator, a knowledge of his character, his able leadership and his drive, make him far and away the likeliest candidate. One of Philip's major achievements was to shift the balances of an intricate system of government in France in favour of the Capetian monarchy, so that its views were more often heeded, and came to be heeded in areas where that had not previously been the case.

Jim Bradbury- Philip Augustus, King of France, 1180-1223xiii

#xii#xiii#jim bradbury#philip augustus king of france 1180-1223#philippe ii#philippe auguste#pierre le chantre#rigord#bertran de born#richard coeur de lion#adèle de champagne#isabelle de hainaut#agnès de france#jean sans terre#battle of bouvines

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

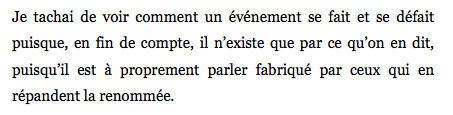

La dimanche de Bouvines: 27 juillet 1214 (1973), Georges Duby

"I was trying to see how an event is made and unmade, as ultimately it only exists via what one says about it, since it is properly speaking fabricated by those who spread its renown."

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

We might know how it ends, but like all good stories it bears repetition. So here it is again, the story of a battle.

Bernard Cornwell, Waterloo: The True Story of Four Days, Three Armies and Three Battles

So I've been getting lots of questions about the significance of the Battle of Waterloo for Britain, France, and indeed Europe.

Great claims have been made as to the legacy of the Battle of Waterloo; but it is not as clear cut as many may claim; for it certainly did not crush all French opposition in a single blow; it did not augur in a century of enduring peace and prosperity across Europe; nor can it claim to have permanently re-established the monarchical system in Europe. Therefore after all the glory, the death and suffering caused on that battlefield, what were its real long term legacies?

For the people living in the vicinity of Waterloo, the utter destruction of the land and of their homes was devastating to their lives, but time soon healed the wounds on the landscape and the abandoned equipment scattered across the battlefields became a virtual treasure trove for the locals as the field of Waterloo was soon at the top of every travellers ‘must see’ list during a sojourn in Belgium. Numbers lived for years selling relics of the battle or became guides to the battlefield as the bloody fields instantly became a top tourist attraction. Every poet and writer in Europe had to visit to witness the scenes of devastation before penning their impressions and publishing to an eager audience, hungry for every new edition.

When they are examined with the benefit of hindsight, battles are rarely accorded the significance given to them. Few become venerated among a nation’s lieux de mémoire, or contribute to the foundation myths of modern nations. Of the battles of the Napoleonic Wars, it is arguable that Leipzig [the 1813 battle lost to the Allies by French troops under Napoleon] has its place in the rise of German nationalism, even if its real importance was greatly exaggerated and mythologized by 19th-century cultural nationalists. In Pierre Nora’s magisterial study of France, only Bouvines, in 1214 [which ended the 1202–14 Anglo-French War], makes the cut. Waterloo, unsurprisingly, does not figure.

Yet at the time Waterloo was hailed in Britain as a battle different in scale and import from any other of the modern era. It had, it was claimed, ushered in a century of peace in continental Europe. It had brought to a close, in Britain’s favour, the centuries-old military rivalry with France. And it had ended France’s dream of building a great continental empire in Europe, while leaving Britain’s global ambitions intact. If the Victorian age could be claimed as ‘Britain’s century’, it was her victory over Napoleon that had ushered it in. Britain, it seemed, had every reason to celebrate, every reason to claim Waterloo as its own.

To some extent Britain’s response was justified; it was a victory that positioned the country favourably, bolstering its global ambitions and helping to create the conditions for the economic success that lay ahead in the Victorian era. Having laid the final, decisive blow on Napoleon, Britain could command a leading role in the peace negotiations that followed and thus shape a settlement that suited its interests. While other coalition states claimed back sections of Europe, the Vienna Treaty gave Britain control over a number of global territories, including South Africa, Tobago, Sri Lanka, Martinique and the Dutch East Indies, something that would become instrumental in the development of the British Empire’s vast colonial command. It is not surprising then that in other parts of Europe, Waterloo - though still widely acknowledged as decisive - is generally accorded less significance than the Battle of Leipzig.

If Waterloo was Britain’s greatest military triumph, as it is often feted, it surely does not owe that status to the battle itself. Military historians generally agree that the battle was not a great showcase of either Napoleon’s or Wellington’s strategic prowess. Indeed, Napoleon is commonly believed to have made several important blunders at Waterloo, ensuring that Wellington’s task of holding firm was less challenging than it might have been. The battle was a bloodbath on an epic scale but, as an example of two great military leaders locking horns, it leaves a lot to be desired.

The short term significance in the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo marked the end of Napoleon’s storied military career. He reportedly rode away from the battle in tears. Though he emerged victorious, the Duke of Wellington later reflected on the the horrific costs of that victory: “My heart is broken by the terrible loss I have sustained in my old friends and companions and my poor soldiers. Believe me, nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won.” Wellington went on to serve as British prime minister, while Blucher, in his 70s at the time of the Waterloo battle, died a few years later.

Waterloo’s long term significance must surely be the role it played in achieving lasting peace in Europe. Wellington, who did not share Napoleon’s relish for battle, is said to have told his men, “If you survive, if you just stand there and repel the French, I’ll guarantee you a generation of peace”. Perhaps the lesson of this historic battle the nations of Europe which fought as foes that day need to forget these old sores and celebrate together; recognising that it did force Europe to acknowledge that it must find a new path of reconciliation and accord. This road has been far from smooth, but each time it has failed, a greater understanding of the need for the European states to work more closely together has emerged from the ashes.

Ultimately this is the truly significant importance of Waterloo.

#cornwell#bernard cornwell#quote#waterloo#battle of waterloo#wellington#napoleon#britain#france#prussia#europe#germany#battle#war#napoleonic war#politics#peace#military history#history

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The kingdom of France after the battle of Bouvines, 13th century.

by @LegendesCarto

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Bataille de Bouvines by Horace Vernet (Galerie des Batailles, Palace of Versailles).

#battle of bouvines#bouvines#philip ii#philip augustus#france#flanders#flemish#holy roman empire#kingdom of france#knights#french#history#europe#european#medieval#art#middle ages#holy roman emperor#otto iv#versailles#horace vernet#holland#brabant#burgundy#england#lorraine#normandy#german#montmorency#limburg

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

27 juillet 1214 : bataille de Bouvines et victoire des Français sur l’empereur Otton IV allié des Anglais ➽ https://bit.ly/2JqOydp Opposant les troupes de Philippe Auguste à celles du Saint-Empire romain germanique, allié du roi d’Angleterre Jean sans Terre qui aspire à se venger de la perte de la Normandie, cette bataille, au cours de laquelle le roi de France est jeté à terre par des fantassins armés de crochets, marque le début du déclin de la féodalité

#CeJourLà#27Juillet#Bataille#Bouvines#Roi#France#Philippe#Auguste#Otton#SaintEmpire#Romain#Germanique#Angleterre#JeanSansTerre#Troupes#Armées#Normandie#histoire#france#history#passé#past#français#french#news#événement#newsfromthepast

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

After pausing to explain who Georges Pontmercy was, Hugo returns to the royalist salon (as if one chapter was not enough). It's torturous to read about it, let alone imagine what it was like being a part of it! And it goes on and on! The endless name-dropping. Sketches of peculiar royalist characters (some of them rather amusing). Though I quite enjoyed the part about the evolution of such salons: from ultras and doctrinarians. Surprisingly, some of the doctrinarians' reasoning is sound and even aligns with historiographic heterodoxy today: “Bouvines belongs to us as well as Marengo. The fleurs-de-lys are ours as well as the N’s. That is our patrimony. To what purpose shall we diminish it? We must not deny our country in the past any more than in the present. Why not accept the whole of history? Why not love the whole of France?”

Taking young Marius to the royalists’ salon is a crime against humanity! A grisly story from the Toulon galleys (Hugo spent a considerable time there collecting all kinds of stories, that’s why we have so many of them about the Toulon galleys) about the collecting of heads and bodies of guillotined individuals is enough to shock a child. Moreover, Marius had to spend hours in the company of “phantoms” or “mummies” from the previous century. “There were some young people, but they were rather dead” –there was a risk that Marius might become one of them. Just look at the result of their influence at the end of the chapter: “He was a Royalist, fanatical and severe,” and “a cold and ardent, noble, generous, proud, religious, enthusiastic lad” (“enthusiastic” as a synonym of “religiously fanatical” used by David Hume et al.) Luckily, we know that Marius still has a significant resource to learn and internalize new ideological doctrines.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is what I read in July !

I also read an essay that I didn't find really interesting called L'Accélération technocapitaliste du temps, essai sur les fondements d'une économie des communs by Renaud Vignes, not pictured here because I already donated the book !

I really recommend Le dimanche des Bouvines by Duby, it was the first time I read his work and I think he has a really interesting approach to history. The book is also very well written, so it makes for a really cool reading experience!

If you see my (not-so-frequent) posts, you can tell that I love Julien Gracq : La Presqu'île is no exception. It's a collection of three short stories, each being fascinating in their own ways.

#bookblr#books#book#book rec#book review#book blog#reading recap#reading journal#reading suggestions

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippe II:

Won the Battle of Bouvines. Overall a pretty cool dude.

Philippe IV:

le gars est tellement sexy que c'est son nom ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

(translation: the guy is so sexy it's in his name *shrug emoji*)

Dates indicated are dates of reign.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Président de l’Union de la jeunesse taurine française, l’éleveur nous explique le contexte politique :"Les animalistes parisiens, Aymeric Caron en tête, qui a emmené le groupe LFI dans le mur, ont échoué à l’automne dernier à faire voter l’abolition de la corrida à l’Assemblée nationale. Je regrette que le vote n’ait pas eu lieu, car finalement cela aurait clos le débat. Nous avions une grosse majorité de députés derrière nous, dont une dizaine de députés communistes. Ils s’attaquent désormais à la bouvine, mais en réalité ces urbains radicalisés mènent une attaque en règle contre notre mode de vie, contre ce que nous sommes. L’élevage, l’agriculture, la chasse, la gastronomie, les traditions taurines et toutes les activités en lien avec les animaux sont dans leur collimateur. S’ils gagnent sur les jeux taurins, ce sera bientôt la chasse, la pêche, et pourquoi pas les joutes sétoises." Au jour J, le 11 février, en fin de matinée, près de 500 gardians à cheval et 15000 manifestants (13000 selon la préfecture) ont pris place au pied du Corum, le palais des congrès de Montpellier, dans le centre-ville, pour défendre leur mode de vie et leur culture. Agriculteurs, éleveurs, pêcheurs, chasseurs, toreros, félibres, raseteurs, écarteurs, gardians, jouteurs, manadiers, directeurs d’arènes, aficionados… tous unis contre la "dictature verte" et les donneurs de leçons des plateaux télévisés ! Parmi les intervenants, Camille Hoteman, la reine d’Arles, s’est fait l’ambassadrice de la culture provençale :"Interdire la corrida, abolir la course camarguaise, radier la course landaise, bannir la ferrade, empêcher l’abrivade, censurer la roussatine, asphyxier la bouvine, c’est renier tout un pan de la culture française. C’est oublier son histoire, car toutes ces pratiques ne sont pas issues d’un mauvais folklore, elles défendent des métiers qui ont permis à nos aînés de vivre et de tirer bénéfice de nos terres." Ce rassemblement historique dans le centre de Montpellier devenu, grâce à la piétonisation, au tramway et aux politiques de "verdissement", une "citadelle imprenable" de bobos s’est terminé comme il se doit par l’hymne du Félibrige Coupo Santo repris en chœur par la foule. Ancien matador et président de l’Observatoire national des cultures taurines, André Viard se veut optimiste sur l’avenir des traditions tauromachiques :"Le cynisme des mouvements politiques qui prônent l’intolérance en opposant les citoyens entre eux provoquera leur perte quand, lassé par la globalisation libéro-libertaire que l’on veut lui imposer, le peuple trouvera refuge dans ses ancrages ancestraux dont on prétend le couper en le privant de mémoire pour mieux le manipuler."”

Pascal Eysseric, « La colère de la ruralité », in la revue éléments n°201, avril-mai 2022.

7 notes

·

View notes