#Chimú art

Text

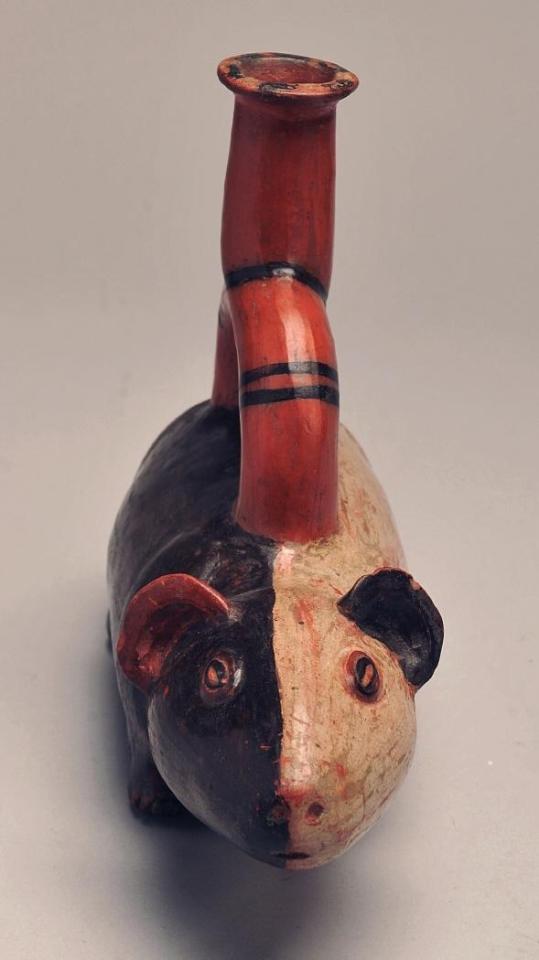

For #GuineaPigAppreciationDay, here are two Chimú polychrome effigy vessels in the form of guinea pigs, North Coast Peru, 1100-1400 CE, now in the Museo de América Madrid collection. Both feature split-color black and white faces so there are three views of each.

Inv. 10217 (3 views)

Inv. 10297 (3 views)

#Chimú art#Peruvian art#South American art#Indigenous art#animal holiday#Guinea Pig Appreciation Day#ceramics#effigy vessel#now in the Museo de América Madrid#polychrome#guinea pig#guinea pigs#cavy#cavies#animals in art#pre conquest art

428 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Feathered Crown

Date: 14th–15th century

Place of origin: Perú

Culture: Chimú

Medium: Feathers (Paradise Tanager, Macaw), cotton, skin, cane, copper

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jill Pflugheber, Microscopy Specialist, and Dr. Steven White, Lewis Professor of Hispanic Studies (retired)

Trichocereus

Trichocereus pachanoi

Feldman’s research on the ritual use of “Wachuma,” the San Pedro cactus, establishes that Trichocereus pachanoi is one of the plants of power that is best represented in pre-Incan iconography, appearing in the art of a variety of indigenous cultures such as that of Chavín, Nazca, Moche, Paracas, and Chimú. The traditional use of this cactus, which contains significant amounts of mescaline, extends to northern Chile, northwestern Argentina, Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador. Even so, he says, the pre-Hispanic uses of the cactus (as a sacrament that facilitated communing with the divine spirits of nature) are still particularly well-conserved in northern Peru in the mountains of Piura (Huancabamba and Ayabaca), where the Complex of Las Huaringas Lagoons (a UNESCO World Heritage Centre) with its “paramo” ecosystem is located. Feldman analyzes the social function of San Pedro as a means of diagnosing illness and healing as well as conflict resolution or achieving prosperity in diverse forms. It is also employed in rituals for predicting the weather, doing astronomical observation, and extracting the mamayacu, (the mother of the sacred waters of the lakes). Feldman believes that the traditional use of San Pedro “represents a factor of social cohesion and regional cultural identity, while at the same time preserving a centuries-old religious system.”

Henri Michaux, Mescaline Paintings. 1950s

“I first took mescaline,” Michaux has said, “to see if I was capable of having luminous and colorful visions. I considered myself a kind of cripple: all my dreams and inner mental images are in dull grey.” But after a few minutes under the drug he decided that the search for luminous images was secondary to the possibilities of the drug for exploring the mind itself. “What immediately interested me,” he says, “was the rapport between the image and the idea, between the wish to see something and what one sees. In mescaline one finds an independent consciousness with its own world of images. One learns what it is both to have and not have a will.’’

#mescaline#hallucinations#art#henri michaux#Jill Pflugheber#microscopy#i'll never do that again#geez

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Tunic with Felines

Date: 1450–1550

Geography: Peru

Culture: Chimú

Medium: Cotton, camelid hair

Dimensions: H. 25 x W. 70 in. (63.5 x 177.8 cm)

Classification: Textiles-Woven

Metropolitan Museum of Art

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Si is an androgenous moon god chosen as the leader of the major South American Chimú and Moche culture pantheon, bucking the trend in world mythology where the moon god is both feminine and inferior to a sun god. The Chimú / Moche cultures placed their Moon god above the Sun god but the Inca that followed them did not.

In 1975 French philosopher Hélène Cixous wrote the book Sorties, concerning our proclivity to employ oppositions to help us better understand the world and ourselves. One insight she had was that opposing pairs of terms often imply a power relationship between those terms. Indeed, the oppositions are often in an active vs. passive or masculine v feminine hierarchy of dominance and submission. To Cixous, dualism entailed hierarchy.

We see this, for example, in mythology with the pairing of the Sun and the Moon as opposites, with the Moon always seeming to be the feminine “lesser light” and the Sun the supreme nurturer of life.

Most of the famous moon deities in mythology are, in fact, female. Yet, it is interesting that the Sun/moon hierarchy was not universal, as the Moche and Chimú peoples of South America turned this schema on its head. The leader of their pantheon was the moon god. This overlord was, indeed, Si, who controlled the seasons, storms and, consequently, agricultural fecundity.

Weapons of the Stone Age - How Throwing Evolved in Ancient Man (Video)

In 1975 French philosopher Hélène Cixous wrote the book Sorties, concerning our proclivity to employ oppositions to help us better understand the world and ourselves. One insight she had was that opposing pairs of terms often imply a power relationship between those terms. Indeed, the oppositions are often in an active vs. passive or masculine v feminine hierarchy of dominance and submission. To Cixous, dualism entailed hierarchy.

We see this, for example, in mythology with the pairing of the Sun and the Moon as opposites, with the Moon always seeming to be the feminine “lesser light” and the Sun the supreme nurturer of life.

Most of the famous moon deities in mythology are, in fact, female. Yet, it is interesting that the Sun/moon hierarchy was not universal, as the Moche and Chimú peoples of South America turned this schema on its head. The leader of their pantheon was the moon god. This overlord was, indeed, Si, who controlled the seasons, storms and, consequently, agricultural fecundity.

Rare Pre-Hispanic Chimú Burial Discovered In Peru

The Mysterious Moche Icon of the Iguana, Companion to the Sky God Wrinkle Face

The Chimú culture at its most mature form only last about 600 years but in that time they worshipped the moon god above all others. This Chimú collar, twelfth-fourteenth century AD, is made of Spondylus beads, stone beads, and cotton, and is part of the NYC Metropolitan Museum of Art collection. (Metropolitan Museum of Art / CC0)

The Chimú culture at its most mature form only last about 600 years but in that time they worshipped the moon god above all others. This Chimú collar, twelfth-fourteenth century AD, is made of Spondylus beads, stone beads, and cotton, and is part of the NYC Metropolitan Museum of Art collection. (Metropolitan Museum of Art / CC0)

For The Chimú and Moche People The Moon God Was Number One!

You may never have heard of the Chimú people, but they hold a significant place in South American history. They had created the largest political system in Peru until they were swallowed up by the Inca.

Remnants of Chimú architecture show that they had a vast, centralized planning system that distributed necessary goods throughout their society to people of all ranks (from peasant to noble). The Chimú created a massive irrigation system, wide roads, and many cities.

When the Inca conquered the Chimú in the mid-to-late 1400s AD, they, basically, absorbed the greatest accomplishments of Chimú culture into their own.

The Moche predated the Chimú and were able to harness streams of water from the Andes into an irrigation system that was able to provide enough crops for the rise of their cities. Their political organization never developed into a centralized state, however, and the reasons for the disappearance of the Moche is still a mystery. Yet, aspects of their mythology were absorbed by the Chimú, including the belief that the Moon was much more significant than the Sun in the order of gods.

Why Did South American Cultures Value The Moon Over The Sun?

The capacity we possessed to use the moon to predict seasonal change gave this primary celestial body immense clout, as folks assumed that the moon was responsible for those changes. The Moon became a type of catalyst which changed the seasons, and which became responsible for the cycle of life and death on Earth.

The food supply of the Chimú was tied up with the workings of this god, and this god was part calendar and part benevolent creator. As Si, the Moon god was responsible for seasonal changes, and he/she (scholars are still not sure whether Si was male or female) was thus responsible for the fertility of the soil and the agricultural output of Chimú society.

In relation to fertility, there was also a noticeable connection between the menstrual cycle and the lunar cycle. The Moche and Chimú also became aware that the Moon had something to do with the rising and falling of the tides, so this moon god was intricately linked to water production and water movement.

Compare this with the workings of the Sun and one can see that the Moon seemed much more dynamic and involved in the processes of life that kept the Chimú people alive. The Sun would, in fact, disappear for many hours each day, forcing the benevolent Si to cast light at night to help protect both people and property.

Distribution of goods was essential to the social organization of the Chimú, and Si helped to ensure that thieves could not sneak into government reserves at night and plunder what was needed by the people. Furthermore, one could even notice Si during the day, wandering around, making sure all was well. Si knew how to hustle. Si was a mover and a shaker. Si the Chimú Moon god was much more hard working than the monolithic Sun!

Indeed, there seemed to be some bad blood between the two as the Moon was sometimes eclipsed and sometimes eclipsed the Sun. When Si eclipsed the Sun, the Chimú rejoiced. It was Si flexing his/her muscles, demonstrating who had the real power, who was really in charge.

Sumerian Hunter-gatherers Liked the Moon, Farmers the Sun

It could well be that the appreciation for the Moon as opposed to the Sun was a carry-over effect from the days of hunter-gatherers. The Moon was one giant and interactive calendar for hunter gatherers. The Moon allowed for the recording of time and made the seasons change and could be used by nomadic groups in their travels.

In Sumeria, Nanna the Moon god gave birth to Shamash, the sun god, almost as an after-thought. This is considered to definitely be a carry-over from the hunter-gatherers who transitioned into a sedentary way of life in the Fertile Crescent due to the overabundance of wild grains and domesticable animals there.

In other cultures, it is thought that the initial appreciation of the Moon was subsumed by an appreciation for the Sun as folks transitioned from hunting and gathering to farming. Basically, farmers did not need the Moon as much as hunter-gatherers did. And, over time, the life and warmth provided by the Sun began to supersede the old powers and prestige of the Moon gods.

Nanna, like other Moon gods around the world, became a god of wisdom as well as a protector of people. His visual representations often included the bull and crescent moons. Of course, the horns of the bull looked a great deal like the waxing and waning crescent moons at the beginning and end of the monthly lunar cycle.

The bull, thus, became equated to the Moon god, possessing crescent iconography on its head and the power of seasonal change and fertility in its very being.

The Moon God: Equated With The Dead And Plant Growth

As farmers began to value the Sun more than the Moon, the lunar cycle became equated to concepts akin to birth, death and rebirth and the belief that somehow the Moon had a great deal to do with fate.

Yet, agricultural societies kept the belief that the cyclical process of vegetative growth was feminine and controlled by the Moon. In various traditions, this feminine presence was forced to recognize its inferior position in its dualistic relationship with the sun, however.

For example, Coyolxauhqui, Aztec goddess of the Moon, was soundly defeated by her brother the Sun god Huitzilopochtli. This battle was ritualistically re-enacted often in conjunction with the Aztec sacred calendar, a reminder of the supremacy of the male sun over the female moon.

We Only Known A Little About the Fairly Short Chimú Culture

Not enough is known about Chimú culture to truly answer these questions about the Moon god and their overall mythology. What we know of the Chimú came to us through the Inca, and we, therefore, cannot consider everything we know about the Chimú to be accurate.

It is certainly true that the Chimú were an agricultural people who had established thorough irrigation systems and populated numerous cities. The initial myths from the hunter-gatherers must have been more powerful than the social and economic factors to abandon them.

Also, the Chimú culture only about 600 years from start to finish. It is possible that the Moon might have become more feminized and placed into a subservient position to the Sun after many more generations.

On the other hand, the respect for the Moon as evinced by the mythology of the Chimú might have survived indefinitely had the Incas not conquered these people, given the extent to which the story had such compelling elements and was so embedded in the life of this people.

#si#hexe#magick#witch community#witchcraft#baby witch#witch tips#beginner witch#pagan witch#chaos magick#witchblr#moon goddess#chimu#moche

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unraveling Centuries of History and Culture of the Andean Odyssey

A rich tapestry woven through millennia, the history of the Andean region of South America took place from the Preceramic period to the Spanish conquest in 1534. Archaeologists such as John H. Rowe and Edward Lanning have meticulously mapped the cultural development of Peruvian civilizations, dividing them into periods and horizons based on ceramic styles and radiocarbon dates.

The journey began in the Preceramic Period (before 9500 BC), pronounced by the earliest evidence of human occupation in Peru, and this period, marked by the absence of pottery, witnessed the gradual evolution of stone-based technologies among hunter-gatherers in the highlands and coastal regions. The transition to ceramic use began in subsequent periods, each characterized by unique cultural traditions and technological advancements.

In the Preceramic Periods I to VI, distinct cultural traditions, monumental architectural structures, population growth, and widespread textile production developed. The development of agriculture and domestication of plants during this time laid the foundation for more complex societies in the Andes. Notable sites such as Quebrada Jaguay, Chivateros, Lauricocha, and Caral Supe/Norte Chico exemplify the diversity and sophistication of Andean cultures in these preceramic phases. While the Quebrada Jaguay illustrates the use of marine and plant resources, the Chivateros showcases the use of stone tools. Lauricocha represents early agricultural activities in the region, whereas the Caral Supe/Norte Chico demonstrates social organization and urban planning.

Subsequent historical periods, from the Initial Period to the Late Horizon, further illustrate the dynamic evolution of Andean societies. The introduction of pottery in the Initial Period (1800-900 BCE) marks a turning point, leading to new settlements along coastal valleys. The Early Horizon saw the rise of Chavín de Huantar, a site in the northern highlands that influenced the spread of the Chavín culture and its artistic motifs. Some consider the Chavín culture the earliest complex culture with intricate art, iconography, and religious rituals.

As time progressed into the Early Intermediate Period (200 BCE-600 CE), more cultures such as the Moche, Gallinazo, Lima, and Nazca emerged, each contributing to the cultural mosaic of the Andean landscape. The Middle Horizon (600-1000 CE) witnessed environmental changes that shaped the region's cultural and political dynamics. Changes in temperature and precipitation patterns influenced agricultural practices, affecting crop yields and food production.

The Late Intermediate Period (1000-1476 CE) featured the fragmentation of political entities, with independent polities governing different areas. Notable cultures during this period included the Chimú society on the north coast and the Chachapoya culture in the highlands. The Chimú utilized the rich coastal resources for sustenance as skilled agriculturalists and fishermen. They developed an extensive irrigation system for agriculture, allowing them to support a large population. The Chachapoya cultivated coca plants, which held ritual and medicinal significance. The exchange of coca leaves with other regional societies contributed to cultural connections.

The Late Horizon (1476-1534 CE) witnessed the rise of the Inca Empire, with sites such as Cuzco, Machu Picchu, and Ollantaytambo becoming symbols of Incan power and influence. The arrival of the Spanish in 1532 brought a seismic shift to Andean history. The conquest led to the region's colonization, with the imposition of new social, religious, and economic systems. The once-mighty Inca Empire crumbled, and the intricate stone structures of pre-Inca and Inca sites became the foundations for new colonial constructions.

Finally, the post-conquest era saw the integration of indigenous elites into the colonial administration, the introduction of a racialized caste system, and the devastating impact of new diseases. The modern era witnessed the rise of movements such as Indigenismo, which sought to valorize indigenous peoples and celebrate the achievements of ancient Andean civilizations. The rediscovery of Machu Picchu in 1911 and the efforts of Andean intellectuals such as José Carlos Mariátegui contributed to a renewed appreciation for Andean culture.

0 notes

Text

Chimú feather art is a pre-Columbian art form originating from the Chimú culture, which flourished on the north coast of Peru between the 9th and 15th centuries AD. @edisonblog

This culture, also known as the Chimor civilization, was contemporary with the Inca civilization and was noted for its skill in various forms of art, including feather art.

Chimú feather art is a unique and exquisite artistic expression that used feathers from birds native to the region to create elaborate and colorful works of art. Chimú artisans developed specialized techniques for dyeing, cutting, and gluing the feathers, creating intricate geometric designs and symbolic representations of deities, animals, human figures, and everyday objects.

Pieces of Chimú feather art were used for ceremonial purposes, as symbols of status and power, and also as funerary offerings in tombs and mausoleums. These works of art were appreciated not only for their aesthetic beauty, but also for the cultural and spiritual value they represented for the Chimú civilization.

Chimú feather art reflects the deep connection that this ancient culture had with nature and the importance they gave to birds and their feathers in their worldview. In addition to their artistic use, feathers also had religious and symbolic significance in the Chimú culture.

Although much of the Chimú feather art creations have been lost over time, some of them have survived to the present day and can be seen in museums and art collections around the world. These pieces are testimony to the ingenuity and artistic skill of the Chimú culture and allow us to know and value their rich cultural heritage.

edisonmariotti by Alejandro A Mendoza

https://shre.ink/aFku

.br

A arte plumária de Chimú é uma forma de arte pré-colombiana originária da cultura Chimú, que floresceu na costa norte do Peru entre os séculos IX e XV dC.

Essa cultura, também conhecida como civilização Chimor, foi contemporânea da civilização Inca e se destacou por sua habilidade em várias formas de arte, incluindo a arte das penas.

A arte plumária de Chimú é uma expressão artística única e requintada que usou penas de pássaros nativos da região para criar obras de arte elaboradas e coloridas. Os artesãos de Chimú desenvolveram técnicas especializadas para tingir, cortar e colar as penas, criando complexos desenhos geométricos e representações simbólicas de divindades, animais, figuras humanas e objetos do cotidiano.

Peças da arte plumária Chimú foram usadas para fins cerimoniais, como símbolos de status e poder, e também como oferendas funerárias em túmulos e mausoléus. Estas obras de arte foram apreciadas não só pela sua beleza estética, mas também pelo valor cultural e espiritual que representavam para a civilização Chimú.

A arte plumária Chimú reflete a profunda ligação que essa cultura ancestral tinha com a natureza e a importância que davam aos pássaros e suas penas em sua visão de mundo. Além de seu uso artístico, as penas também tinham significado religioso e simbólico na cultura Chimú.

Embora grande parte das criações de penas de Chimú tenham se perdido ao longo do tempo, algumas delas sobreviveram até os dias atuais e podem ser vistas em museus e coleções de arte em todo o mundo. Estas peças testemunham o engenho e a mestria artística da cultura Chimú e permitem-nos conhecer e valorizar o seu rico património cultural. @edisonblog

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Tupu

Shawl fastening pin

unknown Chimor silversmith

silver, sometime between AD 1000 and AD 1476

Museo de Arte de Lima

28. X. 18 - my photo

#Fashion#Anonymous#Chimú Kingdom#14th century#Peru#pre Columbian#Museo de Arte de Lima#my photos#silversmithing#tupukuna#photographs

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Painted textile.

Date: A.D. 800–1200

Culture: Central Andes, Central or North Coast, Chancay or Chimú

Period: Middle Horizon to Late Intermediate Period

Medium: Cotton with paint

#ancient America#south America#peru#peruvian#peruano#painted textile#art#textile#chimú#chancay#painted#andes#middle horizon period#late Intermediate Period#9th century#13th century#history#archeology#museum

142 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cecilia Vicuña’s Disappeared Quipu features projected images of textiles that Vicuña chose from our ancient Andean collections, also on view alongside the installation. ⇨ Spanning more than 1400 years, these garments illustrate the great weaving traditions of the Nasca (100–600), Wari (600–1000), Chimú (1100–1400), and Inca (1400–1532) cultures. Like the quipus, these textiles are a way of recording and conveying information. These works complement Vicuña’s installation by connecting the past to the present and honoring an important indigenous artistic tradition. See them on through Nov 25.

Installation view, Cecilia Vicuña: Disappeared Quipu, Brooklyn Museum, May 18, 2018 through November 25, 2018. ⇨ Wari artist. Tunic, 600–800. Southern Highlands, Peru ⇨ Inca artist. Miniature Mantle, 1400–1532. Southern Peru or Northern Chile ⇨ Inca artist. Man’s Tunic, 1400–1532. Southern region, Peru ⇨ Inca artist. Miniature Belt, 1400–1532. Southern Peru or Northern Chile ⇨ Inca artist. Miniature Mantle, 1400–1532. Southern Peru or Northern Chile ⇨ Wari artist. Miniature Tunic, 500–800. Peru ⇨ Inca artist. Man’s Tunic, 1400–1532. Southern Highlands, Peru ⇨ Inca artist. Miniature Mantle, 1400–1532. Southern Peru or Northern Chile ⇨ Nasca artist. Panel Converted to a Poncho, 100–200. South Coast, Peru

#CeciliaVicuña#disappeared quipu#hhm#hispanic heritage month#quipu#textile#andean#nasca#wari#Chimú#inca#peru#latin america#art history

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

Backrest of a Litter

1185–1256

Central Andes, North Coast, Chimú people, Late Intermediate Period

(AD 900 - 1470)

Mixed media: wood, gold alloy, pigment, shell inlay

Cleveland Museum of Art

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

For #OwlishMonday here is a cute silver owl vessel (with two owlets!)

Title: Owl Vessel

Date: 14th–15th century

Geography: Peru

Culture: Chimú

Medium: Silver

Dimensions: H. 6 1/2 in. × W. 3 1/2 in. × D. 6 in. (16.5 × 8.9 × 15.2 cm)

[Metropolitan Museum of Art New York 1978.412.161]

#owl#owls#bird#birds#birds in art#metalwork#silver#Chimú#Peru#Peruvian art#South American art#Indigenous American art#Metropolitan Museum of Art New York#museum visit#Owilish Monday#animals in art

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jar Shaped like an Curling Insect with Single Spout in the Form of a Human Head, Chimú, 1200, Art Institute of Chicago: Arts of the Americas

Gift of Nathan Cummings

Size: 15.2 × 26.7 × 25.7 cm (6 × 10 1/2 × 10 1/8 in.)

Medium: Ceramic

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/6901/

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vessel, Chimú, c.1000–1476, Saint Louis Art Museum: Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas

https://www.slam.org/collection/objects/8914/

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

LOS HERALDOS NEGROS, CÉSAR VALLEJO

Qui potest capere capiat [Quien pueda entender que entienda]. Epígrafe bíblico que preludia a Los Heraldos Negros (LHN); poemario escrito entre 1915 y 1918, publicado en julio de 1919.

«Todos saben... Y no saben / que la Luz es tísica, / y la Sombra gorda... / Y no saben que el Misterio sintetiza... / que él es la joroba / musical y triste que a distancia denuncia / el paso meridiano de las lindes a las Lindes. // Yo nací un día / que Dios estuvo enfermo, / grave». Fragmento de «Espergesia» .

Sobre Cesar Vallejo hay tanto por decir, que puede resultar insulso el intentar hacerlo en una simple reseña, así que, con el fin de no incurrir en estrechez literaria, me limito a dejar un solo dictamen sobre él y su obra: Cesar Vallejo fue un hombre de profundos y dolorosas cavilaciones, de gran esperanza y de penas muy gruesas; su poesía fue y es, y en lo que concierne al mundo, seguirá siendo, una titánica y colosal obra del arte del mundo hispánico-andino, y sobre todo, del mundo entero (universal).

LHN, está compuesto por 69 poemas y dividido en seis secciones: Plafones ágiles, Buzos, De la tierra, Nostalgias imperiales, Truenos, y Canciones de hogar. Los poemas fueron escritos y publicados en fechas muy variadas, y finalmente compendiados en el mencionado poemario.

Sugiero —y es de suma importancia— que se lea la biografía de Vallejo, pues, enriquecerá en demasía la percepción sobre su poética. Cesar Abraham Vallejo Mendoza, nació el 16 de marzo de 1892, en Santiago de Chuco, sierra de La Libertad, departamento peruano. Último de once hijos.

Ciertamente, sería craso el elegir un poema entre todos los que se nos presentan en éste importante libro; en todo caso, me configuro en señalar los que he considerado de suma importancia:

LOS HERLADOS NEGROS, poema, es el pórtico a un mundo oscuro, dulce, triste y esperanzador, con Dios y sin Dios, mordaz, ágil, agresivo, calmado, de profundos llantos y de «nostalgias imperiales»; el primer poema del libro, que considero el de mayor trascendencia [sin desmerecer a los otros] de entre todos los incluidos. Poema decisivo en la evolución vallejiana; prueba inequívoca de lo que clamaba Orrego. Escapa del metro y de la rima.

«Hay golpes en la vida, tan fuertes… ¡Yo no sé! / Golpes como del odio de Dios».

LA ARAÑA, poema que marca a la dualidad inarmónica del hombre, metáfora simbólica animal, El hombre, como la araña, lleva la cabeza y el abdomen separados, la cabeza siempre pugna por ir hacia arriba y, en cambio, el vientre siempre hacia abajo.

NOSTALGIAS IMPERIALES I, poema referente a Trujillo y sus alrededores, con las nostalgias del Gran Chimú, cultura conquistada por los Incas; además, añora la unidad sociocultural del antiguo Imperio inca, que fue rota por la conquista.

ÁGAPE, EL PAN NUESTRO, y LA CENA MISERABLE; tres poemas en los que Vallejo va a confesar la culpa que le trajo su sola existencia, además, el deseo por ayudar al prójimo. Explorará en ellos su profunda sensibilidad frente a la muerte, el hambre de los pobres y los desvalidos, y, la injusticia que hay en la mesa del miserable.

«Todos mis huesos son ajenos; / yo talvez los robé! / Yo vine a darme lo que acaso estuvo / asignado para otro».

LOS PASOS LEJANOS, A MI HERMANO MIGUEL. La ausencia del hogar, la muerte de sus seres amados [su padre y su hermano], esa profunda angustia en el «nunca más», Además, la maduración artística en el vate.

«Mi padre duerme. Su semblante augusto / figura un apacible corazón; / está ahora tan dulce… / si hay algo en él de amargo, seré yo».

LOS DADOS ETERNOS y ESPERGESIA, [preferidos de quien reseña, del poemario entero]. Con estos dos poemas mayores, Vallejo pone en crisis las viejas bases religiosas y filosóficas. Ahonda en sus interiores, se desafía a sí propio, desafiando a la vez a su Dios. Y reclama por su «mala estrella», dejando en evidencia sus profundas angustias, frente a un mundo cruel y tormentoso.

«Dios mío, estoy llorando al ser que vivo; / me pesa haber tomádote tu pan». «Yo nací un día / que Dios estuvo enfermo».

La complejidad de la poesía de Vallejo, no es reducible a una clave que iluminará toda su obra. Toda obra literaria se puede interpretar bajo diversas perspectivas, la poética de Vallejo, con mayor razón debe estudiarse como una «polisemia expresiva». Umberto eco la denomina «obra abierta». Se deben observar todos los factores del texto poético: factor intra-textual, (fonología, métrica, visuales en cuanto a la exploración gráfica, morfológica, sintáctica, semántica, retórica); inter-textual (relación entre textos del autor, relación entre textos del autor y otros textos de la tradición cultural); y extra-textuales (biografía, medio ambiente, marco histórico, etc.).

La complejidad de la obra de Vallejo supone la continuidad de ciertas intuiciones fundamentales y temas obsesivos, mismos que fueron latentes en toda su obra. Pero también hubo una evolución, tanto ideológica, como en recursos expresivos. Podríamos decir que en Vallejo, la sensibilidad fue siempre la misma, pero su técnica estuvo en constante evolución, al igual que su sentido ideológico.

La poesía vallejiana tiene importantes niveles, tanto emotivo como intelectual. Autor de raíces andinas y americanas; además de un innegable aliento universal. No debemos encasillar a Vallejo en valores simples como los «regionalistas», ni tampoco quitarlo de ello solo por su poderosa universalidad. Vallejo se sumergía en lo cotidiano y concreto de su existencia, es por eso que es necesario conocer sus peripecias biográficas y el fondo anecdótico de sus poemas, el marco histórico-social en el que vivía y sus contradicciones metafísicas. Autor de tono maldito y satánico (blasfemo, agnóstico, irónico, pesimista, etc.), y utópico o apocalíptico (identificar lo eterno y lo divino con la realización del hombre en este mundo; casi «desdivinizando» a Dios, y «divinizando» al hombre.

Vallejo fue un autor original en dos sentidos: Primero, en tanto fue distinto, desacostumbrado, singular; segundo, en cuanto a que retrae la esencia del ser a su origen. Hubo quien dijo que Vallejo copiaba; ello sería un error en la medida de que, según Gonzáles Vigil, «[…] Vallejo nunca imita, sino asimila creadoramente» ¹.

El «vate», gran admirador de Dante, Quevedo, Whitman, Rubén Darío (poeta de la lengua española al que más admiró) Picasso, Chaplin, Einsten, y entre otros. Además, asimiló de manera extraordinaria las cuestiones filosóficas, religiosas e ideológicas provenientes del cristianismo, la filosofía griega, el evolucionismo, el positivismo, el marxismo, etc. También veneraba a figuras como Cristo, Buda, Sócrates, Platón, Nietzsche, Marx, Engels, Lenin.

No debemos encasillar a Vallejo en algún ismo, sino aproximarlo, y cuidadosamente: al romanticismo, al postmodernismo, al vanguardismo, etc.; y solamente si somos conscientes de su anti-dogmatismo, podemos vincular sus poemas con el cristianismo, el platonismo, el evolucionismo, el positivismo y el marxismo.

No debemos ver a Vallejo, solamente como el poeta del dolor y de la muerte (que sí es), sino también como el poeta de la vida y la esperanza, de acento profético, evangélico y apocalíptico que anuncia la liberación de la «voz del hombre».

Nuevamente, resulta substancial para comprender la obra del poeta, el conocer su vida, el saber que tuvo una infancia muy feliz en sus terruños santiaguinos, amando su paz bucólica, sus costumbres y sus fiestas andinas; teniendo de núcleo el hogar y el apego a sus hermanos, especialmente a María Agueda, Victoria Natividad y Miguel Ambrosio (más próximo en edad).

Roberto Paoli nos dice que, el mensaje humano de Vallejo tiene una profunda raíz en el alma india, mestiza y serrana, y que el indio se yergue como su modelo de hombre nuevo, en consonancia con el socialismo indigenista; pues, se percibe en su obra la dolorosa inserción a la cultura occidental que éste sufrió cuando se alejó del hogar provinciano. Se muestra nostálgico trabajando en una cultura ajena a él.

El vate universal tenía un fundamental componente de la cultura occidental: La religión cristiana (recordemos que sus dos abuelos varones eran sacerdotes españoles). Y, cuando Cesar se inserta en la vida urbícola, trata con hombres para nada cristianos de temas ateos y agnósticos (la Ilustración, Comte, Gonzales Prada, Nietzsche, Darwin). Su corazón añoraba a Dios, pero su cabeza concurría contra el mismo. Y he allí uno de sus grandes logros poéticos, la alianza entre su corazón andino-cristiano, y, su cerebro marxista: Los heraldos negros (LHN).

Temas importantes para su composición poética en LHN fueron: el descubrimiento de la injusticia social, la explotación de los trabajadores y la marginación cultural de los indígenas. Por ello, es de importante mención algunos hechos en la vida del autor: En 1910 pasó una temporada en el asiento minero de Quiruvilca, San Francisco, provincia de Pasco. En 1911 se desempeñó como preceptor de los hijos de un minero hacendado político, Domingo Sotil, en la hacienda «Acobamba» (valle costeño de Chicama, cerca de Trujillo). En 1912 trabajó como cajero en la hacienda azucarera «Roma», que contaba con más de cuatro mil peones (valle costeño de Chicama, cerca de Trujillo). Pasó una época de gran precariedad económica (fue alumno libre en secundaria y tuvo que interrumpir sus estudios universitarios en San Marcos, Lima; y en Trujillo, en la Universidad de La Libertad, costear sus estudios trabajando como profesor primario. No olvidemos que su piel era de tono cobrizo y tenía facciones marcadamente indígenas, suscitando con ello cierto desdén en la ciudad de Trujillo, hispánica y señorial.

Vallejo escribía desde la secundaria, era un autor incipiente y rezagado en lecturas del Siglo de Oro Español, lo cual lo había dejado perenne en los endecasílabos y los heptasílabos del Quijote y la poesía romántica. Fue Antenor Orrego el primero en detectar el genio creador del poeta, empujándolo a expresarse de modo más auténtico, aunque rompa con normas gramaticales y retóricas. Luego asimiló la nueva poesía del simbolismo francés y el modernismo hispanoamericano. Fue perfilando su tono persona ya patente en algunas composiciones. En otro plano, su sensibilidad social e inquietud ideológica fueron impactadas por la prédica americanista y anti-imperialista.

Todo este aprendizaje poético se vio en LHN, poemario de lenguaje propio, con resonancias del romanticismo, el simbolismo francés, el modernismo de Darío y el novomundismo de Chocano; a los que se agrega un tono post-modernista más personal. Así, Vallejo había asimilado mucho del modernismo y, en LHN lo superó, siendo el poemario hispanoamericano más representativo del post-modernismo.

Según Antenor, lo más notable en LHN, procede del propio Vallejo y va más allá de cualquier deuda con alguna corriente; pues, expresa la angustia que genera el modernismo al poner en duda las creencias tradicionales. Además, inicia la conquista de un lenguaje único, abriendo camino a Trilce; usando palabras «antipoéticas»; explorando la muerte, el dolor, el absurdo, el «yo no sé», el compromiso solidario, el hogar y la infancia, la apuesta por la realización del ser humano con un acento personalísimo y una intensidad incomparable en las lenguas castellanas. Asume rasgos de la sensibilidad indígena, que lo hacen una voz peruana del nuevo mundo americano. Añade un simbolismo numérico relacionado a la biblia, a la cábala, a Pitágoras y a Platón, a Dante y a Darío.

Vallejo le había pedido a Abraham Valdelomar el prólogo para su primer libro. Vallejo admiraba profundamente y sin tapujos a Valdelomar. Por su parte, Valdelomar se había percatado del genio creador de Vallejo y había escrito: «La génesis de un gran poeta. Cesar Vallejo, el poeta de la ternura» (Sudamérica, año I, núm 11, Lima, 2 de marzo 1918).

Un dato curioso: Sus amigos de la Bohemia de Trujillo, Antenor Orrego, José Eulogio Garrido, Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre, Macedonio de la Torre, Alcides Spelucín, Juan Espejo Asturrizaga, y otros, lo apodaban como «Korriscosso», personaje de un cuento de Eça de Queirós. El personaje es un griego exiliado en Inglaterra, Londres, reducido a mozo, incapaz de hacerse oír por una camarera rubia de quien se enamoró.

Como conclusión a la presente reseña, he de señalar y elogiar el gran trabajo que realizaron el antologador y vallejista, Ricardo Gonzáles Vigíl, y los también vallejistas, Max Silva Tuesta, Georgette Vallejo (esposa de Vallejo), Miguel Pachas Almeyda, Roberto Paoli, Juan Larrea, Xavier Abril, André Coyné, y entre otros. Sobre todo, he de resaltar la importancia y la suma substancial que tienen para mí persona, los escritos de Gonzáles Vigíl y de Pachas Almeyda.

Sobre el libro: He utilizado un recopilatorio general de la obra completa de Vallejo, pero solo he reseñado una parte, la cual abarca, solamente a LHN.

Título: Cesar Vallejo — Obra Completa

Idioma: Español

N° páginas: Obra completa, 908 – Los heraldos negros, 55-203 (148)

Editorial: DESA

Colección: Biblioteca Clásicos del Perú

Temática: PoesíaAño de edición: 1991

¹ Gonzales Vigil, R. (1991). Cesar Vallejo. Obras completas (pp. XIII). Edición Biblioteca Clásicos del Perú.

#cesar vallejo#libros#literatura hispanoamericana#literatura#leer#lectura#arte#gato#gatosiames#Cats#Los heraldos negros#literature#literatura peruana#poesía#poetic#acción poética#prosa poética#Poética#poemas#poema corto#reseña#Reseña literaria

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moche religion and art were initially influenced by the earlier Chavin culture (c. 900 - 200 BCE) and in the final stages by the Chimú culture. Knowledge of the Moche pantheon is sketchy, but we do know of Al Paec the creator or sky god (or his son) and Si the moon goddess. Al Paec, typically depicted in Moche art with ferocious fangs, a jaguar headdress, and snake earrings, was considered to dwell in the high mountains. Human sacrifices, especially of war prisoners but also Moche citizens, were offered to appease him, and their blood was offered in ritual goblets. Si was considered the supreme deity, as it was this goddess that controlled the seasons and storms that had such an influence on agriculture and daily life. In addition, the moon was considered even more powerful than the sun because Si could be seen both at night and during the day. It is also interesting that murals and such finds as the intact tomb of the priestess known as La Senora de Cao illustrate that women could play a prominent role in Moche religion and ceremony.

Another deity who frequently appears in Moche art is the half-man, half-jaguar Decapitator god, so-called because he is often represented holding a vicious looking sacrificial knife (tumi) in one hand and the severed head of a sacrificial victim in the other. The god may also be depicted as a gigantic spider figure ready to suck the life-blood from his victims. That such scenes mirror real life events is supported by archaeological finds, such as those at the foot of the Huaca de la Luna where skeletons of 40 men under 30 years of age show evidence that they were mutilated and thrown from the top of the pyramid. The bones of these skeletons display cut marks, limbs were ripped out of their sockets, and jaw bones are missing from severed skulls. Interestingly, the bodies lie above soft ground caused by heavy El Nino rains, which suggests the sacrifices may have been offered to the Moche gods in order to alleviate this environmental disaster. Ceremonial goblets have also been discovered which contain traces of human blood, and tombs have revealed costumed and be-jewelled individuals almost exactly like the religious figures depicted in Moche murals.

1 note

·

View note