#Death of Heinrich Himmler

Text

Death of Heinrich Himmler: Himmler's Missing Brain!

What happened to Himmler’s remains?

Dr. Mark Felton is a well-known British historian, the author of 22 non-fiction books, including bestsellers ‘Zero Night’ and ‘Castle of the Eagles’, both currently being developed into movies in Hollywood. In addition to writing, Mark also appears regularly in television documentaries around the world, including on The History Channel, Netflix, National…

youtube

View On WordPress

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gudrun Burwitz-The sins of the Father continued.

At first glance the picture appears to be quite innocent. A picture of a Bavarian family. However, when you look a bit close you will recognize Heinrich Himmler, in the middle his wife Margarete, and on the left their daughter Gudrun.

Gudrun Burwitz (1929–2018) was born on August 8, 1929, Gudrun was deeply attached to her father, whom she idolized throughout her life. Even after the collapse of…

View On WordPress

#Death of Gudrun Burwitz#Heinrich Himmler#Himmler&039;s Daughter#History#Holocaust#Neo Fascism#Neo Nazis#World War 2

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since it's my birthday, let me share some fun facts about events that have occurred on May 23!

It's World Turtle Day! Ironically, my first word was turtle

I share a birthday with at least two serial killers!

Bonnie and Clyde died on this day in 1934!

#sasha speaks#you know captain kidd and heinrich himmler? they also died on may 23 (different years though lol)#also the unabomber's birthday is the day before mine and jeffrey dahmer's is two days before mine#there have been at least three fatal planes crashes on may 23 as well#my birthday seems to be surrounded by death#but I'm just here to cause chaos and have fun lol

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU, Poland — Along a desolate stretch of road in southeastern Poland, a dozen miles from Auschwitz, there is a graveyard. Candles and fresh flowers cover nearly all the marble tombs. But in the corner stands a large black marble slab separated from the rest.

“Forty-two victims, women, men and children, prisoners from the Auschwitz concentration camp, who were murdered by the Nazis during the death march, and died on Jan. 18, 1945, in the village area of Miedzna were buried in a mass grave in this cemetery,” an inscription explains.

But there are only four names. Another 21 people are identified by their inmate numbers. And 17 have never been identified.

Seventy-five years ago on Jan. 27, Soviet forces swept across Poland from the east and liberated Auschwitz, the camp complex where 1.3 million were enslaved — and 1.1 million among them systematically murdered — during the war.

But before they could arrive, the Nazis force marched some 56,000 weakened prisoners out of the camp ahead of their advance, in the dead of winter, with an estimated 15,000 shot or dying of cold, hunger and illness along the way.

Similar marches were taking place all across the eastern front after the SS chief Heinrich Himmler ordered that all able-bodied prisoners be taken to the Reich.

Despite years of study and troves of testimony from witnesses, the chaos of that evacuation is one of the least understood periods of the Holocaust.

Himmler’s orders served several purposes, according to research by the United States Holocaust Museum. First, he wanted to eliminate evidence of German crimes and witnesses who could testify to those crimes. He also hoped to use inmates as slave labor to keep the German war going. And rather irrationally, he believed that the prisoners could be used as bargaining chips in any peace negotiations.

While death might not have been the goal of the marches, that was indeed the fate of many, as the scattered gravestones that remain along these roads today attest.

Zofia Posmysz still remembers her inmate number: 7566. Sitting in her neatly kept apartment in Warsaw, the 96-year-old survivor remembered the biting cold on the night the guards gathered thousands of women outside the gates of Birkenau, a death camp that was part of the Auschwitz complex.

“We didn’t know what it meant that we would leave the camp,” she said. “We didn’t know if we would have to undergo some sort of selection.

“We heard that those who could not walk would get to stay in the hospital, but we weren’t sure if they would be kept alive. We knew nothing and worried.”

But how could it be worse than the hell she had endured for three years? One memory came rushing back to her.

“One night, I woke up and heard someone singing outside. It was a man’s voice. I thought to myself that our guard wouldn’t probably notice if I sneaked out to have a look. I went outside and saw a man dressed in a black coat. He was singing and raising his arms in the air. Suddenly I felt someone grabbing my arm. It was a Jewish friend from the ward. She asked me: ‘Do you know what he’s singing?’”

“‘No,’ I replied. But it was hauntingly beautiful.”

“It’s a Hebrew song, a prayer for a good death,” her friend told her.

“When we woke up in the morning, there was no more singing; the square was completely empty. All we saw was the smoke coming from the crematory chimney.”

Ms. Posmysz was among those made to march. In her memory, after the first bitterly cold night, the days blend together, something Holocaust scholars say is common among those who survived.

Her next memory is arriving at the station in Wodzislaw Slaski for a train that would take her to another camp in Germany. She would be moved one more time before the end of the war. Once free, she walked for weeks until she finally made it back to her home in Krakow.

Until recently, it would have been possible to find people who lived in the towns and villages along the route who could recall seeing the columns of starving and abused prisoners flanked by Nazi soldiers walking past their homes.

Their numbers, like the survivors, grow fewer every year.

Maria Kopiasz, 93, still lives in the same house in the town of Brzeszcze that she did during the war, and the grim scene of the march has stayed with her.

“They marched in the middle of this road,” she said. “SS men on both sides. Every third of them or so with a German shepherd. I remember mainly women. We knew we couldn’t even show any sympathy as we would be taken with them. I could only watch quietly through the window.”

Jan Stolarz, a retired miner, has led a small group of people on a trek to retrace the path of one of the marches for nine years.

“I visited Auschwitz-Birkenau with my wife 10 years ago,” he explained. “I saw a handwritten note left by someone in one of the barracks. It read: We live as long as the memory of us is alive. This message resonated with me strongly.”

#history#military history#antisemitism#ww2#holocaust#germany#nazi germany#poland#concentration camps#auschwitz concentration camp#heinrich himmler#zofia posmysz#death marches

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

THURSDAY HERO: Albert Battel

Albert Battel was a Nazi officer who turned against the party after witnessing the liquidation of a Jewish ghetto in Poland, and atoned for past sins by saving 100 Jewish families.

Born in 1891 in Prussian Silesia, Albert served in the German Army in World War I. After the war, he attended law school and worked as an attorney in Breslau. In the early 1930’s, as Hitler rose to power in Germany, Albert heard the Nazi leader speak and was inspired by his message of German pride and unity after the humiliating defeat in the Great War. Albert joined the Nazi Party in 1933 and served as a Lieutenant in the Wehrmacht army reserves.

In 1942, Albert was called up from the reserves at age 51. He was sent to Prsemysl, Poland to help liquidate the Jewish ghetto there. Albert was horrified at the human misery he witnessed during the cruel liquidation. Families were being separated, beaten, arrested, and sent to their deaths. The streets were lined with corpses of Jews who died from starvation, disease, beatings or gunshot wounds.

Albert was sickened and enraged by what he saw. Participating in the ghetto liquidation was simply not an option for Albert. Together, he and local military commander Major Max Liedke – another German officer with a moral compass – took action. They ordered the bridge over the River San, the only way to reach the ghetto, to be completely blocked so the SS could not get through. When the Nazi troops tried to cross the bridge, Albert threatened to open fire and kill them all. The local Jewish inhabitants were amazed. Albert then commandeered Nazi trucks to evacuate and save 100 Jewish families. Those families were the only Jews from the entire town of Prsemysl who survived. The rest of Prsemysl’s 24,000 Jews were murdered, most of them at Belzec concentration camp.

The Nazi party immediately conducted a secret investigation of Albert and found a history of kindness to Jews. Before the war, he had been disciplined for lending a small amount of money to a Jewish colleague. Another time, he was publicly reprimanded for shaking the hand of a Jew. The internal investigation went all the way to Heinrich Himmler, head of the Gestapo, who ordered Albert expelled from the Nazi Party and arrested. Himmler postponed Albert’s punishment, however, until after the war to avoid embarrassment for the party.

When the war ended with Nazi defeat, Albert was captured by the Russians. After his release, he returned to Germany but found that his Nazi past made him ineligible to practice law. Because Himmler’s order to expel him had been postponed, Albert was still on the records as a Nazi Party member.

Albert Battel died in 1952 of heart disease. In 1981, Dr. Zeev Goshen, an Israeli lawyer and researcher, investigated and publicized Albert’s story. Due to Dr. Goshen’s efforts, in 1981 Albert Battel was honored as Righteous Among the Nations by Israeli Holocaust Memorial Yad Vashem.

For saving 100 families from certain death at high cost to himself, we honor Albert Battel as this week’s Thursday Hero.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albert Speer

These are some facts and curiosities about Albert Speer, the Fuhrer's architect:

He was born in March 19, 1905.

He spent his youth in the Schloss-Wolfsbrunnenweg, the luxurious family home in Heidelberg, and cultivated a wide range of interests, including skiing, mountain excursions, rugby and, above all, mathematics, a discipline towards which he had a fervent passion.

However, due to his father's opposition, Speer ultimately chose to follow in his uncle's footsteps and study to become an architect.

After studying at the University of Karlsruhe, he moved to Munich, where he studied at the Berlin Institute of Technology, under the guidance of the famous architect Heinrich Tessenow.

During his university years Speer never adhered to any specific faith or political opinion.

This substantial "apoliticality" ceased during his discipleship at Tessenow, when Albert was persuaded by some of his students to participate in a Nazi party demonstration

Speer came into contact with Hitler in 1933 through the intercession of Rudolf Hess, by whom the architect was commissioned to design the apparatus for the Nuremberg rally that year.

Despite some initial doubts, the project met with the sympathy of the Führer and, above all, of Joseph Goebbels, who asked him to renew the Ministry of Propaganda.

An immediate understanding was established between Speer and Hitler: the Führer, in fact, was looking for a young architect capable of giving life to his architectural ambitions for a new Germany and therefore immediately included Speer in his closest circles.

Upon Troost's death in 1934, Speer was chosen by Hitler to replace him as chief architect of the Party.

In 1942, after the death of Fritz Todt (which occurred in a mysterious plane crash), Hitler surprisingly appointed Speer, who had no experience in industrial production, "Minister for Armaments and War Production".

In 1945 Speer refused to carry out the "scorched earth" strategy (established by the Nero decree), which aimed to completely destroy everything in German territories that would fall into enemy hands.

He was a great friend of Karl Brandt (one of the major exponents of Aktion T4) and they acted to save each other's lives: in 1944 Brandt used his powers as General Commissioner of Medical Services and his friendships to save Speer , already ill, from the assassination attempt plotted by Himmler. In 1945 Speer saved Brandt from the death sentence for ''treason''.

Speer was arrested by Allied forces in Flensburg immediately after the end of the conflict, and tried in Nuremberg on charges of using slave labor to run the German war industry.

He was sentenced to twenty years' imprisonment, to be served in Spandau prison in West Berlin.

Prison and solitary confinement provided Speer with the opportunity to write his memoirs, which made him an international celebrity and a very wealthy man.

He died on September 1, 1981, in London.

Some documents discovered after Speer's death prove, without a shadow of a doubt, that as early as 1943 Speer was aware of what really happened in Auschwitz.

Sources:

Wikipedia: Albert Speer

The Nazi Doctors by Robert Jay Lifton ( for the part of Brandt )

Hitler and his loyalists by Paul Roland

I DON'T SUPPORT NAZISM, FASCISM OR ZIONISM IN ANY WAY, THIS IS AN EDUCATIONAL POST

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who knew that the Nazis persecuted the Polish Catholic Church because of antisemitism?

Rudolf Rosner was one of approximately 3000 Polish Catholic priests who were murdered by the Germans during the Second World War. Obviously this had nothing to do with antisemitism and everything to do with Nazi Germany's stated goal of destroying the Polish nation.

Long before signing the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and agreeing to carve up Poland with their Soviet allies, the Germans had already formulated a plan (Generalplan Ost) to turn all of Eastern Europe into the Lebensraum (living space) of Greater Germany. This plan explicitly required the complete destruction of Poland.

Prior to the outbreak of World War 2, thousands of Polish citizens of the Third Reich were arrested and killed. The Nazis also prepared a special list of 61000 of Poland's leading citizens who were to be eliminated following the German invasion (the so-called Intelligenzaktion). They had even drawn up detailed architectural plans to recreate Warsaw as a provincial German town (with a small Polish slave colony in the eastern Praga district).

In his Obersalzberg speech to Wehrmacht commanders on 22nd August 1939, Adolf Hitler explicitly announced that:

…."I have issued the command – and I'll have anybody who utters but one word of criticism executed by a firing squad – that our war aim does not consist in reaching certain lines, but in the physical destruction of the enemy. Accordingly, I have placed my death-head formation in readiness – for the present only in the east – with orders to send to death mercilessly and without compassion, men, women and children of Polish derivation and language. Only thus shall we gain the living space we need"….

Nazi Germany's genocidal intentions towards the Polish people were crystal clear, and although Western historiography on the subject of Poland in the Second World War is focused almost entirely on the holocaust, the Germans also committed some of the worst atrocities in all of human history against the Polish slavic population (mass murder, the destruction of hundreds of Polish villages, ethnic cleansing, deportation of millions of people to concentration and labour camps, the kidnapping of Polish children for forced Germanisation, the brutal suppression of the Warsaw Uprising etc).

They systematically persecuted the Polish Catholic Church as part of the Nazi campaign of cultural genocide in Poland. Thousands of churches and monasteries were closed, seized or destroyed, and eighty percent of Polish Catholic clergy were sent to German concentration camps, where at least 1800 lost their lives (more than 800 in Dachau alone).

The Auschwitz concentration camp was established on Heinrich Himmler's orders in April 1940 and was located in Polish territory that was incorporated directly into the Third Reich. Alongside Stutthof (opened in 1939) and Majdanek (opened in 1941), it was constructed initially to intern Polish slavic prisoners.

The Germans incarcerated approximately 450 priests, seminarians and monks in Auschwitz, as well as 35 nuns. Most of them perished there or in other German camps.

#auschwitz#auschwitz-birkenau#concentration camp#german concentration camp#history#second world war#world war 2#germany#poland#polska#bad history takes#bad history take

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reposting my Müller biography

THIS POST DOES NOT SUPPORT THE N*ZI IDEOLOGY, IT IS PURELY EDUCATIONAL

Heinrich Müller [28 April 1900 - Unknown date of death] was a high-ranking Schutzstaffel [SS] officer and police official of the N*zi Reich. Müller was born in Munich, Germany to a catholic household. During the last year of the First World War [1918], Müller provided himself as a pilot for an artillery spotting unit in the Luftstreitkräfte, and was accorded on multiple occasions for bravery, [The Iron Cross First and Second Class, Bavarian Pilots Badge, and Bavarian Military Merit Cross Second Class with Swords].

After the end of the First World War, Müller joined the Bavarian Police as an auxiliary worker in 1919, witnessing the suppression of the Communist and Red Army risings in Munich during the Bavarian Soviet Republic, and developing his enmity of Communism.

Throughout the years of the Weimar Republic, Müller rose quickly through the ranks and secured his place as head of the Munich Political Police Department.

While in his SS career, Müller was acquainted with many members of the N*zi Party [NSDAP], These members including Reinhard Heydrich and Heinrich Himmler. Müller was generally seen as a supporter of the Bavarian People's Party [The predominant party, ruling Bavaria at the time] during the Weimar period. On 9 March 1933, the N*zi putsch deposed the Bavarian government that Müller held the title Minister-President of. Müller commanded his superiors to perform force against the N*zi movement. These actions influenced Müller's rise and as a result, Müller was promoted to Polizeiobersekretär, in May 1933 and then Criminal Inspector, in November 1933.

Heinrich Müller joined the Schutzstaffel [SS] in 1934 and by 1936, Müller was its operations chief. Müller was then promoted to the Standartenführer [colonel] rank in 1937, following on to 1938 when Müller was made Inspector of the Security Police for the entirety of Austria. One of Müller's first major acts that stood out was on 9-10 November 1938, when Müller directed the arrest of 20,000-30,000 Jews. Müller was also tasked by Reinhard Heydrich during the summer of 1939 to construct a centrally organized authority to handle the eventual emigration of the Jews.

Although Müller was part of the N*zi movement, Müller had a preference for the Red Army, admiring the Soviet police and publicly comparing Stalin against H¡tler, claiming Stalin performed leadership more preferably. [This of course was very contrast to his previous enmity of Communism].

Müller was made chief of the RSHA [Amt IV], Office/Dept on September 1939. Müller gained the title 'Gestapo Muller' to differentiate him from another Schutzstaffel [SS] general with the name Heinrich Müller.

Müller continued to rise rapidly through the Schutzstaffel [SS] ranks, becoming an SS-Oberführer in October 1939, and then the rank Gruppenführer and Lieutenant General of the Police in November 1941.

Concluding with Müller's disappearance, Müller was last reported being seen in the Führerbunker, on the evening of 30 April 1945, the date of H¡tler's suicide. Müller's cause of death or the whereabouts of his remains have not been confirmed, but it is suggested that Müller was either killed by the Russians or had committed suicide during the fall of Berlin. If Müller's body has indeed been recovered, it was not identified.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

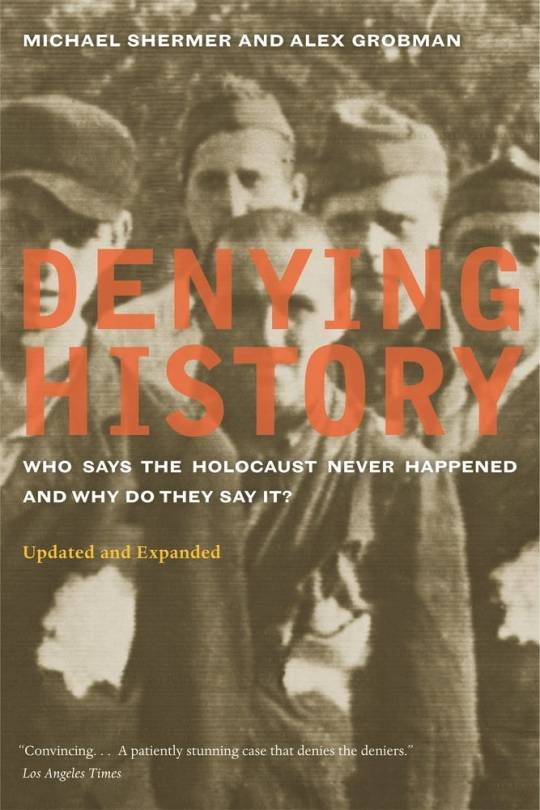

By: Michael Shermer

Published: Oct 13, 2023

As the horror of violence, rape, and murder of Jews in Israel by Hamas terrorists unfolded this past week I was astonished—and sickened—to hear the “whataboutism” and “bothsideism” response of many commentators and activists on the political Left that sounded eerily similar to the moral equivalency arguments I encountered when researching my book Denying History, on “who says the Holocaust never happened and why do they say it?” (co-authored with Alex Grobman). To be fair, some commentators on the political Right have used their platforms to blame Joe Biden for enabling or emboldening Iran to back Hamas terrorism—as Ted Cruz did on Megyn Kelly’s show—but at least the Right has the moral clarity to distinguish between genocide and complex political issues such as instituting a Two-State solution to the the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

By contrast, the progressive Left (a term I use to distinguish them from more mainstream center-left liberals and classical liberals) seems hopelessly adrift at sea without a moral compass. As I posted on X, what’s the difference between White supremacists at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia chanting "Jews will not replace us" and “You will not replace us” and Palestinian Supremacists at a rally in Sydney, Australia celebrating the Hamas murder of Jews chanting "Gas the Jews" and “Fuck the Jews”? If you go far enough to the Left you end up on the far end of the Right. (This is called the horseshoe theory, in which the far Left and the far Right are actually close in ideology at the two ends of the bent political spectrum.)

In another post on X I declared that it is not fair to compare Hamas to Nazis (which some on the Right are doing)—not fair to the Nazis I meant! Why? Because at least the Nazis knew that the orchestrated extermination of European Jewry was wrong and would be condemned by other nations. That’s why the Nazis murdered most of the Jews (and others) in secret, mostly in isolated death camps in Eastern Europe and Poland, such as Auschwitz, Majdanek, Treblinka, Sobibor, Chelmno, and Belzec. That’s why the paramilitary Schutzstaffel (SS) Einsatzgruppen death squads responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, was conducted far from the prying eyes of German citizens in Nazi occupied territories to the East. That’s why the Wannsee Protocol, like that of most Nazi documents in dealing with the “Jewish question,” is obfuscated by innocuous-sounding jargon, such as:

action, special action, large-scale action, reprisal action, pacification action, radical action, cleaning-up or cleansing action, cleared or cleared of Jews, freeing the area of Jews, Jewish problem solved, handled appropriately, handled according to orders, liquidated, over-hauling, rendered harmless, ruthless collection measures, severe measures, special treatment or special measures, executive tasks, elimination, evacuation, eradication, relocation, and, of course, Final Solution (Endlösung).

That’s why this letter from Heinrich Himmler to Ernst Kaltenbrunner, who succeeded Reinhard Heydrich as chief of security police and SD after Heydrich’s assassination, is declared to be “Top Secret!”:

Reichsfuhrer-SS Field HQ

April 9, 1943

Top Secret!

To the Chief of the Security Police and SD Berlin:

I have received the Inspector of Statistics’ report on the Final Solution of the Jewish Question. I consider this report well executed for purposes of camouflage and potentially useful for later times. For the moment, it can neither be published nor can anyone be allowed sight of it. The most important for me remains that whatever remains of Jews is shipped East. All I want to be told as of now by the Security Police, very briefly, is what has been shipped and what, at any points, is still left of Jews.

Hh

That’s why at war's end the Nazis covered over their crimes, burned documents, destroyed the crematoria and gas chambers, and denied any wrong doing after. And that’s why throughout the 1930s the Nazis went to great lengths to change German law to later justify their actions as legal, under the pretense that if they lost the war they could argue—which they did at the Nuremberg war-crime trials—that national sovereignty precludes one nation judging the actions of members of another nation whose laws differed at the time. That defense didn’t fly and the murderers were brought to justice.

By contrast, far from denying their crimes, for the past week Hamas has been bragging about murdering Jews, posting videos on social media and declaring "Allahu Akbar" (God is Great). Worse, many on the progressive Left in the United States have been condemning…Israel! At The Free Press Bari Weiss has compiled a list of examples that reveal, in her words, “the rot inside our universities”:

Over 30 student groups at Harvard said of the 1,200 Israelis who have been slaughtered that “The apartheid regime is the only one to blame.”

A joint statement from Columbia University’s Palestine Solidarity groups wrote “we remind Columbia students that the Palestinian struggle for freedom is rooted in international law, under which occupied peoples have the right to resist the occupation of their land.”

Northwestern University’s Middle Eastern and North African Student Association “grieves for the martyrs and the civilians lost in this time.”

A student group at California State University in Long Beach advertised its “Day of Resistance: Protest for Palestine” event on Tuesday with a poster that showed a crowd waving the Palestinian flag and a Hamas paraglider—a symbol of mass murder—in the top corner.

At Stanford, hand-painted signs appeared on buildings declaring: “The Israeli occupation is NOTHING BUT AN ILLUSION OF DUST.” (In The Stanford Review, Free Press intern Julia Steinberg wrote that, on Instagram, “my classmates posted infographics declaring that, ‘from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.’ ”)

Students for Justice in Palestine at the University of Virginia declared on Sunday that “The events that took place yesterday are a step towards a free Palestine.”

To be blunt, these people are genocide deniers, almost indistinguishable from the Holocaust deniers I encountered and debunked over twenty years ago. Here is what we wrote in Denying History about the moral equivalency argument and why it is not just wrong but morally obscene:

Ironically, after denying that the Nazis intended to exterminate the Jews, deniers argue that what the Nazis did to the Jews is really no different from what other nations do to their perceived enemies. David Irving, for example, points out that the U.S. government obliterated two Japanese cities and their civilian populations with atomic weapons—the only government in history to do so. Furthermore, Mark Weber notes, Americans concentrated Japanese Americans in camps, much as Germans did to their perceived internal enemy—the Jews. These examples and others, such as Irving’s citation of the mass bombing of Dresden, have a not-so-hidden agenda: to implicate America and Britain as equally guilty, along with Germany, in the mass destruction of the Second World War.

But what is missing in this comparison? First, there is a big difference between two nations fighting one another, both using trained soldiers, and the systematic, state-organized killing of unarmed, unsuspecting people—not in self-defense, not to gain territory or wealth (although these may accrue as a beneficial by-product), but because of anti-Semitism. Scholars and the general public debate the morality of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the internment of Japanese Americans in concentration camps, and the mass bombing of Dresden. But historians do not try to equate these actions with the Holocaust. If we take the mass bombing of Dresden, for instance—although it was admittedly one of the worst acts against the Axis powers by the Allies, it resulted in about 35,000 deaths, not the 250,000 first claimed by the Germans (Goebbles exaggerated the number for propaganda purposes), and nowhere near the 6 million of the Holocaust.

At his trial in Jerusalem Adolf Eichmann, SS-Obersturmbannfuhrer of the Reich Security Main Office and one of the chief planners and organizers of the Final solution, tried to make the moral equivalency argument. The judge, however, did not accept his rationalizations, as this sequence from the trial transcript shows (and let this serve as a refutation of today’s claim for the moral equivalency of Hamas and Israel):

Judge Benjamin Halevi to Eichmann: You have often compared the extermination of the Jews with the bombing raids on German cities and you compared the murder of Jewish women and children with the death of German women in aerial bombardments. Surely it must be clear to you that there is a basic distinction between these two things. On the one hand the bombing is used as an instrument of forcing the enemy to surrender. Just as the Germans tried to force the British to surrender by their bombing. In that case it is a war objective to bring an armed enemy to his knees. On the other hand, when you take unarmed Jewish men, women, and children from their homes, hand then over to the Gestapo, and then send the to Auschwitz for extermination it is an entirely different thing, is it not?

Eichmann: The difference is enormous. But at that time these crimes had been legalized by the state and the responsibility, therefore, belongs to those who issued the orders.

Judge Halevi: But you must know surely that there are internationally recognized Laws and Customs of War whereby the civilian population is protected from actions which are not essential for the prosecution of the war itself.

Eichmann: Yes, I am aware of that.

Judge Halevi: Did you never feel a conflict of loyalties between your duty and your conscience?

Eichmann: I suppose one could call it an internal split. It was a personal dilemma when one swayed from one extreme to the other.

Judge Halevi: One had to overlook and forget one’s conscience.

Eichmann: Yes, one could put it that way.

In assessing the initial response to the rape, torture, and murder of Jews in Israel by Hamas this week I can only conclude that the progressive Left denouncing Israel and celebrating Hamas have had to overlook and forget their moral conscience.

#Michael Shermer#Israel#palestine#hamas#moral equivalence#morality#moral confusion#antisemitism#ideology#decolonization#ethnic cleansing#religion is a mental illness#The Holocaust#Holocaust

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

WITCHCRAFT: EIGHT MYTHS AND MISCONCEPTIONS

1. Witches were burned at the stake

Not in English-speaking countries. Witchcraft was a felony in both England and its American colonies, and therefore witches were hanged, not burned. However, witches’ bodies were burned in Scotland, though they were strangled to death first.

2. Nine million witches died in the years of the witch persecutions

About 30,000–60,000 people were executed in the whole of the main era of witchcraft persecutions, from the 1427–36 witch-hunts in Savoy (in the western Alps) to the execution of Anna Goldi in the Swiss canton of Glarus in 1782. These figures include estimates for cases where no records exist.

3. Once accused, a witch had no chance of proving her innocence

Only 25 percent of those tried across the period in England were found guilty and executed.

4. Millions of innocent people were rounded up on suspicion of witchcraft

The total number of people tried for witchcraft in England throughout the period of persecution was no more than 2,000. Most judges and many jurymen were highly sceptical about the existence of magical powers, seeing the whole thing as a huge con trick by fraudsters. Many others knew that old women could be persecuted by their neighbours for no reason other than that they weren’t very attractive.

5. The Spanish Inquisition and the Catholic Church instigated the witch trials

All four of the major western Christian denominations (the Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist and Anglican churches) persecuted witches to some degree. Eastern Christian, or Orthodox, churches carried out almost no witch-hunting. In England, Scotland, Scandinavia and Geneva, witch trials were carried out by Protestant states. The Spanish Inquisition executed only two witches in total.

6. King James I was terrified of witches and was responsible for their hunting and execution

More accused witches were executed in the last decade of Elizabeth I’s reign (1558–1603) than under her successor, James I (1603–25).The first Witchcraft Act was passed under Henry VIII, in 1542, and made all pact witchcraft (in which a deal is made with the Devil) or summoning of spirits a capital crime. The 1604 Witchcraft Act under James could be described as a reversion to that status quo rather than an innovation.

In Scotland, where he had ruled as James VI since 1587, James had personally intervened in the 1590 trial of the North Berwick witches, who were accused of attempting to kill him. He wrote the treatise Daemonologie, published in 1597. However, when King of England, James spent some time exposing fraudulent cases of demonic possession, rather than finding and prosecuting witches.

7. Witch-hunting was really women-hunting, since most witches were women

In England the majority of those accused were women. In other countries, including some of the Scandinavian countries, men were in a slight majority. Even in England, the idea of a male witch was perfectly feasible. Across Europe, in the years of witch persecution around 6,000 men – 10 to 15 per cent of the total – were executed for witchcraft. In England, most of the accusers and those making written complaints against witches were women.

8. Witches were really goddess-worshipping herbalist midwives

Nobody was goddess-worshipping during the period of the witch-hunts, or if they were, they have left no trace in the historical records. Despite the beliefs of lawyers, historians and politicians (such as Karl Ernst Jarcke, Franz-Josef Mone, Jules Michelet, Margaret Murray and Heinrich Himmler among others), there was no ‘real’ pagan witchcraft. There was some residual paganism in a very few trials.

The idea that those accused of witchcraft were midwives or herbalists, and especially that they were midwives possessed of feminine expertise that threatened male authority, is a myth. Midwives were rarely accused. Instead, they were more likely to work side by side with the accusers to help them to identify witch marks. These were marks on the body believed to indicate that an individual was a witch (not to be confused with the marks scratched or carved on buildings to ward off witches).

- Diane Purkiss, Professor of English Literature at Keble College, University of Oxford

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

ADOLF HITLER

ADOLF HITLER

1889-1945

Adolf Hitler was born and raised in Austria and had an unhappy childhood. His father was brutal, but Hitler looked up to his mother. He was a frustrated teenager and his artistic pursuits were disappointing, even though he had artistic talent. He served as a soldier in the German army during World War I where he was wounded. After the war he was lonely, isolated, and frustrated and he fantasised about much greater things and got entwined in politics.

Germany was in an economic crisis and the German people were desperate for better days. In Munich, his party the National Socialist Party (NSDAP) attracted servicemen and disgruntled citizens. In 1924 Hitler was sentenced to five years in prison for staging the coup ‘Beer Hall Putsch’, he served only nine months and spent that time writing a book. Hitler’s book Mein Kampf (My Struggle) was published in 1925, the book was about his life and his political ideas. After his release he recruited Herman Goring, Heinrich Himmler and master propagandist Josef Goebbels.

In 1933, his party won the parliamentary elections, there started the Nazi party, Third Reich and Hitler was their Fuhrer. Hitler predicted they would be in power for a thousand years and those who initially believed that the Nazi party wouldn’t last, would regret that they didn’t do more when it was possible.

During his time in power he was known for his hatred towards Jews, Communists, Gypsies, political opponents and anybody else he disliked - he had them cruelty treated and killed. On 30 June 1934, was the Night of the Long Knives he destroyed any opponents, to get rid of Jews out of power and made sure he had total control. Hitler created the SS who were loyal only to Hitler and the secret police called the Gestapo. He had anybody he found undesirable sent to concentration camps, where millions died.

Hitler embarked on a military program on a massive scale to make Germany a mega power. He attempted to take power wherever he could, the capture of Austria, Czechoslovakia, and the Rhineland; he then invaded Poland in 1939, which led to war with France and Britain. Winston Churchill refused to be duped by Hitler and even though Hitler first aligned with Stalin, Stalin later turned to side with the allies. In 1941 Hitler invaded the Soviet Union; the Russians were able to drive the Germans back. He then seized Denmark and Norway and then took over France in a matter of weeks. Hitler then declared war on the United States. The Allied troops invaded Germany from the east and west and had Germany in ruins.

On 30 April 1945, Hitler and his wife Eva Braun commit suicide inside his Berlin bunker. The night before, around midnight, he married Braun. He wrote his will and declared Martin Bormann his deputy and expelled former right-hand man Hermann Goering and Heinrich Himmler for disloyalty. The two men had been concerned for Hitler’s mental state and doubted his ability to head the party in the last weeks of Hitler’s life when they would have known that the Third Reich was about to fall.

Hitler and his closest aides had moved into the bunker below the Reich Chancellery garden on 16 January 1945 as allied forces closed in. The bunker housed medical staff, aides, telephonist and his secretary’s. The bunker was decorated in furnishings and artwork.

On 22-23 April, those in the bunker had left but Hitler chose to remain until the end. On 30 April, Allied and Soviet troops moved into Berlin, prompting Hitler and Braun to end their lives. Braun swallowed a cyanide capsules and Hitler then shot himself. Afterwards Bormann doused their bodies with gasoline and set fire to them. That same day, Hitler’s minister Joseph Goebbels and his wife, killed their six children and then committed suicide. A week after Hitler’s death, Germany surrendered which ended World War II. The charred remains of Hitler remained in Russian custody, a skull fragment complete with a bullet hole and four teeth. Hitler and Braun were buried in unmarked grave in east Germany, their bodies along with those of the Goebbels family, were exhumed in 1970 on the orders of KGB boss Yuri Andropov, they were incinerated again, and the ashes poured into a river.

#adolfhitler #worldwarII

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RAuawJT7-Io

Tisha b’Av is coming up. The Ninth (day) of (the Hebrew month) Av is a day of . . . . well, of lamentations. The Book of Lamentations, Eicha, is read, and people fast and treat the day as a day of mourning. The mourning is for all of the death and persecution and massacre that has befallen the Jewish people over the course of history, of which there is quite a bit. There’s even quite a lot of verifiably dated crap that befell the Jews on or around Tisha b’Av, including expulsions from England (1209), France (1306), and Spain (1492), Heinrich Himmler receiving authorization for the Final Solution (1941), the first deportations from the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka (1942), the AMIA bombing in Buenos Aires (1994), and a few other events. So there’s a fair amount to mourn.

One of the things that happens during Tisha b’Av is the singing of various dirges called kinnot about the sad state in which the Jews find themselves. This is one of them, traditionally sung on the morning of Tisha b’Av. The composer is Boruch Schorr, a 19th-century hazzan from Lemberg, which we know today as the city of Lviv, a place that is itself no stranger to death and persecution and massacre.

Also, I should point out that we do have in our holiday cycle a whole day devoted exclusively to mourning the collective mountain of misfortune that the world has heaped upon the Jewish people, from antiquity to the present day . . . and yet, we also have an entirely separate day set aside for Holocaust remembrance. That should probably tell you something about the Holocaust, if even Tisha b’Av isn’t quite enough to contain that memory.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Politics of Homophobia: Examining the Intersection of Political Expediency and Nazi Ideology

This is the entirety of my first published piece of writing.

Abstract

Homosexual men in Nazi Germany experienced legal and social oppression that was rooted in both the cultural homophobia of Twentieth Century Germany and the existential homophobia of high-ranking Nazi officials. However, the Nazi Regime’s enforcement of homonegative policy was not unilateral, often ignoring the actions of members of Nazi-affiliated groups. This inconsistency often resulted in leniency for party insiders, and brutality for gay men in occupied territory, and Nazi-era policy, reinforced by cultural homophobia, left a lasting effect on the legal treatment of gay men in West Germany. By using public comments and private correspondence, this paper explores the existential homophobia of Himmler, his influence on Hitler and the Nazi carceral system, and the inconsistencies of the Regime’s criminal enforcement of homonegative policies. Furthermore, by utilizing the memoirs of gay men, this paper explores the impact of homonegative policy on homosexual men that lacked proximity to power. Lastly, this paper utilizes court records and firsthand accounts to explore the post-war treatment of gay men in West Germany. This paper seeks to not only explain the origins and outcomes of Nazi homonegative policy, but also to understand patterns of homonegative rhetoric in order to combat queerphobic policies in our own society.

Text

“Röhm, you are under arrest.” These words, uttered by Adolf Hitler in June 1934 during the Rӧhm Purge, changed the power dynamics of the Nazi Party. Hitler and Joseph Goebbels found Ernst Rӧhm and several other SA leaders with young SS officers, all in various states of undress, many caught having sex at the moment of their discovery. The Fuhrer, though, had greater concerns than Röhm’s sexual proclivities. He was there to oust a political rival. Röhm, sitting comfortably in a Bad Wiessee hotel room in a fashionable blue suit with a cigar in the corner of his mouth, responded with the simple words: “Heil, my Fuhrer.” Hitler shouted for his arrest a second time, and left Rӧhm’s hotel room. Rӧhm was escorted out of the Hotel Hanselbauer without a challenge, now a prisoner of the Nazi Regime, alongside dozens of SA men. On July 1st, 1934, Ernst Röhm was executed in his Munich cell. Despite the fact that Röhm was targeted as a threat to Hitler’s political power, the Nazi Regime made his homosexuality a key feature of the discussions surrounding his execution. On July 3rd, 1934, the Völkischer Beobachter, the official Nazi Party newspaper, ran articles discussing the Fuhrer’s swift squashing of a “second revolution,” as well as an article discussing how the German people were “saved from the serious danger” of homosexual subterfuge. Later, in August of 1934, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler excitedly told Gestapo officers that the execution of Ernst Rӧhm was necessary to avoid “the capture of the state by homosexuals.”

Prior to this attack on the SA’s leadership, now known as the Night of the Long Knives, Röhm’s homosexuality was not seen as much of an issue by Hitler and other members of Nazi leadership, so long as it was kept behind closed doors. The Nazi party tolerated homosexuality within its ranks, and Röhm’s Sturmabteilung (SA) cultivated an openly homosocial culture amongst its members. Other institutions within the Nazi Regime, like Heinrich Himmler’s Schutzstaffel (SS) and the Hitler Youth, cultivated a similar homosocial culture, and members of each organization were known to engage in homosexual acts. So why then was Röhm’s homsexuality manufactured as a crisis following his death?

In the wake of Röhm’s arrest and execution, the Nazi party increasingly targeted homosexual men. Scholars estimate that between 1933 and 1945, the Nazi Regime arrested more than 100,000 gay men for allegedly violating Reich Criminal Code Paragraph 175, which the regime revised in 1935 by broadening the definition of homosexuality and creating harsher penalties for those convicted of violating Paragraph 175. Further, the Nazis incarcerated as many as 15,000 gay men in concentration camps, and the testimonies of some concentration camp survivors suggest that gay men were among the most abused populations within the camps. How can we explain this change in legal and persecutorial practices?

While the Nazi Regime wielded accusations of homosexuality as a tool of political power, it is also the case that the Nazi persecution of gay men frankly represented the irreducible homophobia of leadership within the Nazi Regime. Despite the ideological homophobia of some Nazi leaders, the Nazi Regime was highly opportunistic in its implementation and enforcement of homonegative policy. This inconsistency often, though not always, resulted in leniency for Nazi Party insiders, and brutality for gay men in occupied territory, and solidified fear and isolation as key components of Germany’s Post-War queer culture. While homosexuality was conditionally tolerated in the early years of the Nazi regime, the conspiratorial beliefs of high-ranking Nazi officials, like Heinrich Himmler, coupled with the Nazi Party’s obsession with proliferation and purification of the Volkskörper, necessitated, within the framework of the Nazi ideology, the elimination, marginalization, or otherwise removal of homosexuality from German culture.

As the Nazi Party solidified its control of the German state, the pursuit of a pure Volkskörper, or racial body, came into focus. To this end, the regime marginalized those considered racially impure, or those incapable of producing offspring; the Nazis, therefore, viewed homosexual men, unable to reproduce, as a drain on the Volksgemeinschaft. But the regime’s focus on procreation and family policy does not necessarily explain its violent suppression of homosexuality, or the murder of thousands of gay men. While not socially or politically prioritized, there is no evidence to suggest that the Nazi Regime murdered infertile women, for example, en masse. But cultural homophobia placed gay men on the fringes of society, which made violence against them easy to justify. Furthermore, accusations of homosexuality against political opposition became a very convenient weapon wielded by the Nazi Party. The vehement bigotry against gay men expressed by Heinrich Himmler filtered down to local police officers, which likely further desensitized Germans to violence against gay men, and pushed for the excision of homosexuality from German culture. After all, the Reich would do anything to rid the Volkskörper of a “cancer” like homosexuality.

The history of homosexuality in Germany is colored in shades of gray. The Nazi Regime capitalized on cultural and religious homophobia, as well as a desensitization to violence powered by the Nazi propaganda apparatus, to commit atrocities against gay men. However, Germany in the late 19th Century was the home to the first proper homosexual movement. While Imperial Germany included Paragraph 175 in the legal code adopted in 1871, just after Germany unified, which criminalized homosexuality, there was also a robust movement for the destigmatization, decriminalization, and integration of homosexuality in mainstream German society as early as the 1890s. Early LGBT publications first began to appear in Germany during this period. And Magnus Hirschfeld founded the first gay rights organization, the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, in Berlin in 1897. Much of the gay rights activism happening in Imperial Germany, which included activism in support of gay men, lesbian women, bisexual folks, and transgender individuals, centered around the thesis of the innate nature of homosexuality, which posits that homosexuality, or any facet of queer identities, is naturally occurring and immutable.

Colloquial understandings of the Weimar period (1919-1933) frame this era of Germany as sexually liberated and nearly utopian. In fact, Nazi propaganda disparaged the Weimar Republic’s social progressivism as a source of hedonism and degeneracy. However, far from liberated, the Weimar policy towards queer communities was repressive and shrouded in secrecy. Despite pressure from the burgeoning metropolitan queer community, most notably in Berlin, and a general sense of tolerance, the Weimar legislature did not repeal Paragraph 175. However, Weimar Germany’s federal system allowed for different states to adopt a policy of non-enforcement towards the persecution of gay men. During this period, while queer communities—gay men in particular—faced oppression from both the state and society at large, in many instances, gay men experienced greater freedom from the punishments of Paragraph 175, so long as they did not disturb broader society. It is in this environment of simultaneous secrecy and tolerance that a robust, yet ultimately underground, queer culture emerged in the Weimar republic, allowing for a golden age for queer communities in Germany, and in Berlin especially. In this period, Berlin’s queer community produced magazines, fiction literature, and art specifically for queer Germans. Gay men also had enclaves of social interaction, music, and performance in Germany’s gay bars and clubs, like the famous Eldorado night club.

The Weimar period represented a golden age for queer art, activism, and progress. Weimar Germany’s queer movement prioritized the social tolerance of some gay men over others. As a part of its respectability politics, the queer movement in the Weimar Republic promoted the image of hypermasculine homosexuality, and in many cases, hypermasculinity as homosexuality. These hypermasculine men, often engaged in dangerous work like timberwork, factory work, and even military service, were the face of the homosexual movement in Weimar Germany, often appearing as the main characters in homosexual fiction and as the focus of queer magazines in Berlin. These men represented the pinnacle of German masculinity, which many saw as legitimizing their sexuality to a heteronormative society. This version of homosexuality grew out of the various inter-war men’s groups, which brought together communities of disenfranchised veterans of the Great War, and fostered a homosocial culture between its members. In some cases, these groups even permitted homosexual and homoromantic relationships. This culture, which fostered many anti-war sentiments, may itself have its roots in the Wandervogel movement, an anti-industrialist German youth movement that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Wandervogel faced a great deal of public backlash, in part because of its tolerance of homosexuality, which many Germans saw as a promotion of degeneracy. It is worth noting that, because of this focus on hypermasculine homosexuality, the queer movement in Germany often excluded effeminate or otherwise gender nonconforming gay men, out of fear that they may damage the movement’s respectability in broader culture.

This golden era of German queer politics came to an abrupt end when the Nazi Regime took power. In June 1935, the Nazi Regime amended Paragraph 175 of the Reich Criminal Code as a part of a broad reformation of the German legal code, broadening the government’s definition of homosexuality and reclassifying the offense as felonious in nature. In the two years immediately following Hitler’s rise to power, the Nazi Regime had to collaborate with far-right and conservative political blocs in the Reichstag. This 1935 legal reform was likely an effort to shore up support from the German right-wing. Under this amended version of Paragraph 175, which legally conflated homosexual sex between men with bestiality, men engaging in “lustful acts” with other men could be imprisoned for as little as three months or as many as ten years. The inclusion of the language of “lustful acts” greatly increased the Nazi Regime’s power over homosexual men. Prior to the implementation of Paragraph 175a, the threshold for conviction under 175 was quite high, as prosecutors had to prove anal penetration in a para-coital fashion. This meant that non-penetrative sexual acts between men, including mutual masturbation and oral sex were difficult to prosecute. This changed with the 1935 amendments to 175. The regime, perhaps deliberately, failed to define “lustful acts,” which allowed local officers to individually interpret 175a. In some cases, “lustful acts” were as benign as being in an emotionally deep relationship with another man, regardless of its sexual nature or lack thereof. Lustful acts, as interpreted by local officers, included small acts of affection, like holding hands and kissing, as well as explicitly sexual acts like mutual masturbation and penetrative sex. But it also included “suspicious cohabitation,” which could be interpreted as homoromantic.

The amendment, in its entirety, contains four subsections pertaining to male-male homosexual sex. Of these four, only one legislates consensual homosexual sex between adult men; the law made no mention of lesbianism or other homosexual acts between women. The other three sections dealth with male-male rape, sexual coercion, and male prostitution. Rape victimizing women was legislated through Paragraphs 176 and 177, the sexual coercion of women is legislated through Paragraph 179, and female prostitution is legislated through Paragraph 181. The Nazi regime separated rape, coercion, and prostitution as experienced by women in an effort to frame homosexual men as predatory and pedophilic. Furthermore, the statute includes language that highlights the criminality of relationships between men over the age of twenty-one and those under the age of twenty-one. Additionally, the statute includes provisions for men under twenty-one to receive a lighter sentence, or even face no criminal liability provided they engage in reform work. This reform work was often enrolled in anti-homosexual programs by the Hitler Youth.

Despite existing laws against homosexuality and the Nazi Party’s collaboration with the German conservative political bloc, Ernst Röhm, an openly gay man, was the commander of the SA, which was the Nazis’ paramilitary wing. As an early Nazi figure, he led the SA from its infancy in 1921 until his murder in 1934. In this role, he organized street fights, sabotages, and assassinations against socialists, communists, antifascists, and even random Germans in an attempt to cause chaos which could only be stopped by the Nazi Regime. The actions of the SA under Röhm were of great benefit to Hitler and the Nazi Party during its struggle for and rise to power, despite the fact that Röhm held great contempt for the bureaucracy of the Nazi Party. Despite the direction of the regime’s later actions, this does not appear to be a point of great contention within the early Nazi Party. In fact, there were many gay men in Röhm’s SA. This could be, in part, because the Nazi Party and the SA, much like the interwar men’s groups, fostered an informal homosocial environment. However, there were high-ranking Nazi officials who resented Röhm for his homosexuality, but ultimately allowed him to continue his work while it was useful. Additionally, Röhm was not above committing acts of violence and oppression against the queer community in Germany. Röhm’s SA commandeered the Eldorado, Berlin’s most famous gay bar, as the SA headquarters just ahead of the 1933 elections, and carried out raids on Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Research on May 6th, 1933, just months after Hitler’s rise to power.

Chief among these hesitantly permissive Nazis was Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer of the SS. During the Night of the Long Knives, Adolf Hitler ordered the arrest and execution of Röhm and many other Nazi Party members that he viewed as a threat to his control. As the result of intelligence meetings with Hermann Göring and Himmler, Hitler feared that Röhm was preparing to stage a coup. Additionally, Röhm’s SA was adamantly opposed to the continued involvement of traditional conservative elites, whom Hitler still required the support of, in the German government. Himmler was quick to share his satisfaction with Röhm’s death, telling SS officials that the regime had just narrowly avoided “capture of the state” by homosexuals. Himmler viewed homosexuality as an existential threat to the German state and his conspiratorial homophobia influenced Adolf Hitler’s homonegative actions. Later, in February 1937, just as the regime began incarcerating racial, religious, and social enemies of the state, Himmler referred to homosexual men as a “cancer” on the Volkskörper in a speech given at a conference of SS officers. During this speech, Himmler stressed that the eradication of homosexuality from German culture was critical to the Aryan race’s survival and future, stating “all things which take place in the sexual sphere are not the private affair of the individual, but signify the life and death of the nation.” As Reichsfuhrer SS and Chief of German Police since 1936, Himmler’s homophobia trickled down to many facets of the regime’s carceral system, with local police chiefs echoing Himmler’s existentialist fears and conspiratorial beliefs about the nature and consequences of gay men later in June of 1937. It is therefore likely that Himmler’s essentialist homophobia motivated the escalation and advancement of violence against gay men, and that his rhetoric desensitized the public to violence against an already maligned population.

This research is concerned with the intersection of political and legal justifications the Nazi Regime used to commit violence against gay men, and the cultural homophobia that facilitated this violence. It is therefore necessary to examine the individual experiences of gay men living in this intersection. To this end, this project will utilize memoirs and diaries written by gay men in Nazi Germany, like the writings of Gad Beck and Josef Kohout. This is done with a recognition that, particularly for memoirs written after the fact, the human memory is imperfect, fallible, and subject to its own biases. Additionally, this research will draw on Reich Criminal Code, Gestapo case files, and the transcriptions of speeches and remarks made by Nazi officials. This research is relying on translations of these documents, typically carried out by the US and British governments. Lastly, this research engages with the historiography of this topic by drawing from, supporting, or countering the work of historians who have previously written on this topic. This is of particular note because, through a combination of social stigmatization and the broad persistence of the criminalization of homosexuality in European and Euro-descendent countries, English-speaking scholars wrote relatively little on this subject prior to the new millennium.

Homophobic crimes committed by the Nazi Regime are often seen as purely ideological; that the Nazi Party as a whole was concerned with homosexuality as an ideological ill. However, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels’ early tolerance of Ernst Röhm, as well as the accepted homosocial circles in early Nazi groups, suggest that the Nazis’ homophobia was not rooted strictly in an ideological opposition to queerness. The nature of early actions against queer communities, like SA raids on Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Research, were likely the result of the Nazis’ desire to squash Weimar's social liberalism as a whole. Additionally, many queer folks were aligned with the Socialist and Communist parties, even as these parties held their own homophobic beliefs, making them political enemies early on. The very fact that Ernst Röhm was the head of the SA while being openly homosexual demonstrates that gay men that fell in line with the Nazi ideology could survive, provided their homosexuality remained a private affair. However, the Night of the Long Knives changed this.

Homosexuality was at once a great concern for the Nazi Regime as well as an easy and effective tool to oust political opposition. It was, at the same time, an existential threat to the German race, and a politically debilitating accusation to level against the opposition. While the enforcement of homonegative policies in Nazi Germany was inconsistent, they provide a clear window into the thought processes of high-ranking Nazi officials. Any suggestion that the Nazi persecution of gay men was done purely as a means of political expediency ignores how the Nazi Regime deliberately employed racialized language and weaponized the court systems to oppress gay men. Conversely, any argument that posits that the regime’s detestation of homosexuality is in any way comparable to the regime’s antisemitism ignores both the totality of exterminationist policies against Jewish people and the highly selective manner in which the Nazi Regime enforced homonegative policies. By focusing strictly on the legal mechanisms of Nazi homonegative policy, or only on the social and cultural homophobia that enabled these policies, the field has created a gap in research. There is a distinct intersection of political expediency and genuine homophobia that motivated Nazi homonegative violence. It is important to understand the intersection of political opportunism and essential homophobia when analyzing Nazi homonegative policy, as it is from that intersection that we see the greatest harm done to gay men.

As the old hegemony fades, we are only now beginning to understand the Nazis’ persecution of homosexual men. Many countries in the western world continued to criminalize homosexuality in the decades after World War II, and queerness remains socially and politically stigmatized the world over. Laws against sodomy, which have historically been used to criminalize homosexuality, remained in place in a majority of US states throughout the 20th century, only being federally decriminalized in 2003. The United Kingdom did not decriminalize homosexuality until twenty years after World War II. It is likely that a culture that codified homonegativity and homophobia into law would place a lesser significance on the crimes the Nazi Regime committed against gay men. It is therefore unsurprising that scholars have placed a lesser focus on understanding the social, legal, ideological, and political roots of the Nazi Party’s violent and suppressive crimes against gay men. Furthermore, homosexual men never constituted more than one percent of all concentration camp inmates. This, coupled with the fact that the Nazi Regime additionally identified many men sent to concentration camps for homosexuality as sexual or racial criminals, meaning that, although the treatment of homosexual men was abhorrent, they remained a small enough population in the broader victimology of Nazi crimes against humanity, allowing them to be easily overlooked. The issue remained dramatically under-researched for roughly fifty years after the fall of the Nazi Regime, gaining early interest in the 1990s, with research accelerating and broadening in the late 2000s and early 2010s.

A great deal of research into the Nazis’ persecution of queerness has been done in the past thirty years, with the bulk of such research occurring in just the past ten. In that time, the historical interrogations of the Nazi Party’s oppression of gay men broadly follow two trends. Firstly, historians have investigated the persecution of gay men through a legal and political lens, seeking to understand the criminal codes, judicial decisions, and political prescriptions that advanced homonegative action in Nazi Germany. These historians are generally concerned with the mechanics of Nazi oppression, or the “how.” Subsequently, they rely heavily on political and legal documentation that demonstrates the direction and execution of Nazi homonegative policy at a local, state, and federal level. However, other historians have chosen to focus on the ideological underpinnings of Nazi homophobia, or the “why.” These historians examine the social and political origins of the Nazis’ oppression of gay men, particularly as they relate to Nazi conceptions of masculinity and Nazi racial science. And to that end, these historians examine memoirs, interrogation records, propaganda, and Weimar-era queer politics to understand Nazi homophobia. These trends are not mutually exclusive, and can feature significant overlap. However, different adjacent fields clearly influence the respective foci of these historians, and their writings therefore diverge in meaningful ways.

Historians concerned with the political and legal underpinnings of the Nazi oppression of gay men, subsequently referred to as our legal historians, explore the Nazi Regime’s use of the legal system to persecute gay men. The work of historian Geoffrey Giles examines the methods that Nazi judges, Kripo officers, and Gestapo officers used to twist and weaponize the German legal code to justify the castration of homosexual men. Giles argues that Nazi police used “exceptional zeal in prosecuting actual or supposed homosexuals” and that “the lines of definition were blurred” pursuant to the ends of castrating homosexual men for the crime of homosexuality. Giles would later argue that the regime broadened the legal definition of homosexuality, in part, to tighten social control and shore up support from the conservative bloc. He additionally argues that the Nazi Regime weaponized the reactionary conservative courts in an effort to capitalize on cultural homophobia and build political consensus among the German right wing. In both of these works, Giles utilizes court records, Kripo files, and the Nazi legal code itself to build his case. In both his writing and his source work, Giles has deeply influenced subsequent scholarship, and his work represents the forefront of legal history regarding this subject.

Since the turn of the millennium, historians have continued to analyze the Nazi persecution of gay men through a variety of academic lenses, and many of these historians, who will be referred to as our social historians, have interrogated the sociopolitical underpinnings of Nazi homonegative policy and violence. Social history is a broad field, and scholars who utilize this style of inquiry employ many angles of analysis. The historians outlined here utilize gender as their primary lens of analysis, but categorizing their work as strictly “gender history” is not entirely accurate, as they also employ an interdisciplinary understanding of sexuality, power, and racialization to understand the Nazi persecution of gay men. Dr. Clayton Whisnant has written two extensive texts on queerness in Germany. The first of these texts, Queer Identities and Politics in Germany, 1880-1945, published in 2016, examines the political movements of the flourishing underground queer culture throughout the first half of the 20th century. Whisnant argues that the Nazi regime was particularly brutal in its legal and extralegal persecution of gay men, noting that many gay men died extra judiciously in concentration camps as a result “cruel and sadistic games” that targeted these men, who were seen as failing to live up to the hegemonic ideal of German masculinity. Subsequently, Dr. Jason Crouthamel expanded on this idea of the hegemonic ideal of German masculinity by using the interrogation records of homosexual World War I veterans to illustrate how these men reconciled their masculinity and gendered expectations with their sexuality. Using these men as examples, Crouthamel argues that the Nazi Regime targeted homosexuals, in part, because homosexual men asserting their “agency” and masculinity threatened Nazi images of masculinity as an inherently heterosexual trait. These historians employ a modern understanding of gender as performance, as well as memoirs, interviews, and Nazi political speeches to build their case, supplementing their arguments with the foundation of legal history built by scholars like Giles.

The Nazi persecution of queerness is a subject that is sadly under-researched, with the experiences of lesbian women and transgender folks constituting a significant gap in the historiography. However, Dr. Laurie Marhoefer has proven to be as influential in social history literature as Dr. Giles is for the legal history of the subject. Dr. Marhoefer published a robust microhistory on the persecution of lesbians and gender nonconforming folks in Nazi Germany. Marhoefer argues that the Nazi Regime had a broad definition of lesbianism, similar to their broad definition of homosexuality as it related to men, and that transgender, gender nonconforming individuals, and women engaged in same-sex relationships were at unseen and subtle social risk in Nazi Germany. Their work expands historical definitions of persecution, and considers “the concept of risk” as experienced by lesbians, transgender folks, and gender nonconforming folks. Dr. Marhoefer utilizes gender and queer theories that position gender as a social performance and sexuality as fluid, and explores the sexual liberalism of the Weimar period through these theories. They argue that the sexual tolerance of the Weimar Republic was conditionally ensured by the comfort of a heteronormative society, meaning that queerness needed to be kept behind closed doors or sectioned off from polite society, which had the knock on effect of denouncing gender nonconformity and platforming the image of hypermasculine performance as an expression of homosexuality. In the eyes of many movement leaders, gay men needed to conform to the ideal of German masculinity in order for their social and sexual identities to be tolerated, if not necessarily validated, by the broader culture. These factors, Marhoefer argues, all but guaranteed that Nazi Party’s reactionary fascism would easily dismantle the sexual liberalism of the Weimar Republic. The echoes of Dr. Marhoefer’s work can be seen in much of the history written in the past seven years, as historians like Whisnant and Crouthamel iterate on Marhoefer’s ideas of masculine performance and queer respectability politics in Nazi Germany.

Some historians have used the framework of social history to explore the homosocial environments of Nazi Regime institutions, like the Schutzstaffel, the Sturmabteilung, the Hitler Youth, and the German military. Giles explores the contradictions between Nazi political rhetoric and the observed reality of the SS. In doing so, he asserts that Himmler’s unwillingness to acknowledge the homosocial culture of the SS was likely a result of the Nazi Regime’s desire to maintain ideological consistency. The SS needed to maintain its image as a racially perfect institution. However, racialized language of degeneracy and cancer ascribed to homosexuals by the Nazi Regime, and especially by Heinrich Himmler himself, would have complicated that racially pure image should the SS be seen as a homosocial group. Giles, in this work and others, makes frequent references to Heinrich Himmler’s personal homophobia, and cites speeches wherein the Reichsführer of the SS refers to homosexuals as a disease of the Volkskörper.

The study of the Nazi persecution of homosexuality is a small field still in its relative infancy compared to other segments of Holocaust histories. This is likely due to the present but diminishing social stigma around queerness; as queerness continues to be destigmatized, a greater number of queer historians and historians interested in queer histories will no doubt enter the field and advance the historiography. These new historians will likely continue to analyze Nazi persecution through interdisciplinary lenses, building on the legal history of scholars like Geoffrey Giles, and continuing the work of social historians like Jason Crouthamel, Clayton Whisnant, and Laurie Marhoefer. Some historians, like Giles and Marhoefer, are academic trailblazers, carving a new niche in the field and exploring questions previously unanswered. Others will build theoretically rigorous and detailed works situated comfortably within those niches, such as Whisnant’s two-part book series on queer politics in Germany. It is therefore the goal of this work to navigate the intersections of the legal and social histories laid out by prior historians, and to understand ideological and political causes of the Nazi persecution of gay men.

To address this gap in historiography, and to understand the overlaps of political expediency and Nazi homophobia, it is important to draw from a wide variety of documents. The nature of researching the Nazi Regime’s crimes necessitates using a great deal of perpetrator documents, such as Gestapo case files, Nazi speeches, and governmental decrees. Additionally, the relative lack of interest in the Nazi persecution of gay men until the 1990s means that very few contemporary documents from ally governments pay close attention to the treatment of gay men in Nazi Germany. Much of what we know from the individual perspective comes from a combination of legal records and the very few memoirs of gay concentration camp survivors, who suffered a death rate as high as 60%. In order to get a clear picture of Nazi homonegative policy and its implementation, the memoirs of Josef Kohout and Gad Beck are of particular importance. These humanizing stories demonstrate both the resiliency of those targeted by Nazi oppression and the cruelty of the regime, and are therefore critical to understanding the human cost of Nazi homonegative politics.

A young German Jewish man, against all odds, deceived a Schutzstaffel officer tasked with overseeing the deportation of Jews from Berlin. By disguising himself as a member of the Hitler Youth, he was able to sneak into the processing area and save a young man just before hundreds of other Jewish folks were sent away on the rails. But he did not do this for himself. He was not trapped there. He did this for one chance to free his lover, Manfred Lewin. But, to the man’s shock, this would still be their last embrace. “I can’t go with you,” Lewin told his brave partner. “My family needs me. If I abandon them now, I could never be free.” And so, with a stoic look of resolve, Lewin turned and left his young lover, returning to his family bound for Nazi incarceration. In 1942, Manfred Lewin and his family died in Auschwitz. Gad Beck remembered the pain of losing his young partner until his death in 2012. Of that day, Beck said “In those seconds, watching him go, I grew up.” The pain that Beck experienced, and the pain he saw inflicted on those around him, pushed him to action. In 1942, shortly after Beck learned of Manfred Lewin’s death at the hands of the Nazis, Beck joined the Chug Chaluzi, a Jewish resistance group whose name translates to “Pioneer Circle,” which worked to help German Jews escape the Nazi reign of terror to Switzerland. Gad Beck passed away in 2012, just weeks before his 89th birthday. Though he saw himself as only a small part of antifascist resistance in Nazi Germany, he continues to be regarded as a hero.

Beck’s memoir, published in 2014, two years after his death, tells a familiar and heartbreaking story of a man’s life torn asunder by war, and how he was pushed into action by the pain and loss all around him in Austria. He dedicated his life at the time to helping Jews in German occupied territory escape to Switzerland, but he never escaped himself. He withstood arrests, beatings, shootouts, and air raids because of his antifascist work. Gad Beck’s memoir is dripping with pain; in every interaction, the words remembered by this man are colored by sadness and fear, but defiance and bravery above all else. Beck’s story is one of an antifascist organizer, who survived the Nazi Regime’s reign of terror through community action. Other survivors, like Josef Kohout, were regular civilians who survived by chance, and experienced brutal violence and vindictive experimentation in Nazi concentration camps.

The intersection of politics and bigotry is emblematic of many of the Nazi Regime’s greatest crimes. In his dictated memoir, originally published in 1972 by his friend Hans Neumann under the pseudonym Heinz Heger, Kohout outlines his experience as a gay man under Nazi rule. Kohout was in a relationship with the son of a Nazi official for about a year, from March 1938, until Kohout was arrested by the Gestapo in March 1939. It is of particular note that the son of the Nazi official was not arrested like Kohout. Despite the regime’s position on homosexuality, it was not uncommon for men, and young men in particular, with connections to party officials to avoid incarceration for homosexual activity. Many young men, especially those in the SS or with connections to the SS, had their sentences commuted. Josef Kohout was not so lucky, nor so well-connected.