#Herman Melville: A Biography

Text

Herman Melville on Napoleon’s love for Ossian

Context: Ossian is the narrator and purported author of a cycle of epic poems published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson, originally as Fingal (1761) and Temora (1763), and later combined under the title The Poems of Ossian.

“I am rejoiced to see Hazlitt speak for Ossian. There is nothing more contemptable in that contemptable man (tho' good poet, in his department) Wordsworth, than his contempt for Ossian. And nothing that more raises my idea of Napoleon than his great admiration for him.—The loneliness of the spirit of Ossian harmonized with the loneliness of the greatness of Napoleon.”

Melville wrote this around 1862 in the margins of his copy of Hazlitt’s Lectures on the English Comic Writers and Lectures on the English Poets

Source: Hershel Parker, Herman Melville: A Biography - Volume 2, p. 436

#Herman Melville#Melville#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Hershel Parker#Herman Melville biography#Herman Melville: A Biography#Hazlitt#Lectures on the English Comic Writers#Ossian#romanticism#napoleonic era#napoleonic#american literature#American lit#american renaissance#Wordsworth#the poems of Ossian#celtic mythology#fingal#temora#british literature#Scottish#scottish literature#Scotland

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

This has no right being as funny as it is

#the end is sad don’t look at that don’t look#Herman Melville#from herman melville: a biography by hershel parker vol 2

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"You see, John and I grew up like twins although he was a year and a half older than me. We grew up literally in the same bed because when we were on holiday, hitchhiking or whatever, we would share a bed. Or when we were writing songs as kids he'd be in my bedroom or I'd be in his. Or he'd be in my front parlour or I'd be in his, although his Aunt Mimi sometimes kicked us out into the vestibule!"

"I think Linda put her finger on it when she said me and John were like mirror images of each other. Even down to how we started writing together, facing each other, eyeball to eyeball, exactly like looking in the mirror."

twins, bari wood; moby dick, herman melville; the beatles: the biography, bob spitz; dead ringers, cronenberg

#someone needs to volunteer to euthanize me atp.#when the mclennon pseudo-incestual vibes hit#they wouldve loved being conjoined twins fr#beatles

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

the unofficial ultimate bungo stray dogs reading list

this is mainly for myself bc i rly do want to read most if not all of these and i'm sure it's already been done by someone somewhere. but, i thought why not post it lmao; most if not all of these can be found on anna's archive, z-library, or project gutenberg! (also, consider buying from your local bookstore!) for those that are a bit harder to find, i've included links, though some are from j-stor and would require login to access.

detective agency:

osamu dazai:

no longer human (novel)

the setting sun (novel)

nakajima atsushi:

the moon over the mountain: stories (short story collection)

light, wind and dreams (short story)

fukuzawa yukichi:

an encouragement of learning (17 volume collections of writings)

all the countries of the world, for children written in verse (textbook)

yosano akiko:

kimi shinitamou koto nakare (poem)

midaregami (poetry collection)

edogawa ranpo:

the boy detectives club (book series)

japanese tales of mystery and imagination (short story collection)

the early cases of akechi kogoro (novel)

kunikida doppo:

river mist and other stories (short story collection)

izumi kyouka:

demon lake (play)

spirits of another sort: the plays of izumi kyoka (play collection)

tanizaki junichirou:

the makioka sisters (novel)

the red roof and other stories (short story collection)

miyazawa kenji:

ame ni mo makezu; be not defeated by the rain (poem)

night on the galactic railroad (novel)

strong in the rain (poetry collection)

port mafia:

mori ougai:

vita sexualis (novel)

the dancing girl (novel)

nakahara chuuya:

poems of nakahara chuya (poetry collection)

akutagawa ryuunosuke:

rashoumon (short story)

the spider's thread (short story)

rashoumon and other stories (short story collection)

ozaki kyouyou:

the gold demon (novel)

higuchi ichiyou:

in the shade of spring leaves (biography and short stories)

hirotsu ryuurou:

falling camellia (novel)

tachihara michizou:

in mourning for the summer (poem)

midwinter momento (poem)

from the country of eight islands: an anthology of japanese poetry (poetry collection)

kajii motojirou:

lemon (short story)

yumeno kyuusaku:

dogra magra (novel)

oda sakunosuke:

flawless/immaculate (short story)

sakaguchi ango:

darakuron (essay)

the guild:

f. scott fitzgerald:

the great gatsby (novel)

the beautiful and the damned (novel)

edgar allen poe:

the raven (poem)

the black cat (short story)

the murders in the rue morgue (short story)

herman melville:

moby dick (novel)

h.p. lovecraft:

the call of cthulhu (short story)

the shadow out of time (novella)

john steinbeck:

the grapes of wrath (novel)

of mice and men (novel)

lucy maud montgomery:

anne of green gables (novel)

the blue castle (novel)

chronicles of avonlea (short story collection)

louisa may alcott:

little women (novel)

the brownie and the princess (short story collection)

margaret mitchell:

gone with the wind (novel)

mark twain:

the adventures of tom sawyer (novel)

adventures of huckleberry finn (novel)

nathaniel hawthorn:

the scarlet letter (novel)

rats in the house of the dead:

fyodor dostoevsky:

crime and punishment (novel)

the brothers karamozov (novel)

notes from the underground (short story collection)

alexander pushkin:

eugene onegin (novel)

a feast in time of plague (play)

ivan goncharov:

the precipice (novel)

oguri mushitarou:

the perfect crime (novel)

decay of the angel:

fukuchi ouchi:

the mirror lion, a spring diversion (kabuki play)

bram stoker:

dracula (novel)

dracula's guest and other weird stories (short story collection)

nikolai gogol:

the overcoat (short story)

dead souls (novel)

hunting dogs: (i must caveat here that the hunting dogs are named after much more comparatively obscure jpn writers/playwrights so i was unable to find a lot of the specific pieces actually mentioned; but i still wanted to include them on the list because well -- it wouldn't be a bsd list without them)

okura teruko:

gasp of the soul (short story; i wasn't able to find an english translation)

devil woman (short story)

jouno saigiku:

priceless tears (kabuki play; no translation but at least we have a summary)

suehiro tetchou:

setchuubai/a political novel: plum blossoms in snow (novel)

division for unusual powers:

taneda santouka:

the santoka: versions by scott watson (poetry collection)

tsujimura mizuki:

lonely castle in the mirror (novel)

yesterday's shadow tag (short story collection; i was unable to find a translation)

order of the clock tower:

agatha christie:

and then there were none (novel)

murder on the orient express (novel)

she is the best selling fiction writer of all time there's too much to list here

mimic:

andre gide:

strait is the gate (novel)

trascendents:

arthur rimbaud:

illuminations (poetry collection)

the drunken boat (poem)

a season in hell (prose poem)

johann von goethe:

faust

the sorrows of young werther

paul verlaine:

clair de lune (poem, yes it did inspire the debussy piece, yes)

poems under saturn (poetry collection)

victor hugo:

the hunchback of notre-dame (novel)

les miserables (novel)

william shakespeare:

romeo and juliet (play)

a midsummer nights' dream (play)

sonnets (poetry collection)

the seven traitors:

jules verne:

around the world in 80 days (novel)

journey to the center of the earth (novel)

twenty thousand leagues under the seas (novel)

other:

natsume souseki:

i am a cat (novel)

kokoro (novel)

botchan (novel)

h.g. wells:

the time machine (novella)

the invisible man (novel)

the war of the worlds (novel)

shibusawa tatsuhiko:

the travels of prince takaoka (novel; unable to find translation)

dr. mary wollstonecraft godwin shelley

frankenstein (novel)

#bungo stray dogs#bsd#literature#dark academia#reading list#academia#i'm sure there's people i've missed but i did my best LOL#this also really throws into a stark contrast how relatively un-worldly american literary curriculums really are#obviously; it makes vague sense to focus american literary schooling on the western 'canon' bc so much of the english language#is influenced by it and the 'culture' is more touched by it but HOLY SHIT does it just... astound me#how uneducated i am on even east asian literature (from wheremst i technically hail!!!)#i know like.... maybe 3?? 4??? chinese writers off cuff???#like the only reason i even know anything about jpn literature is i got my minor in jpn so i read some stuff but WOWWWWW there's a wORLD.#the fact that i knew not a SINGLE work by most of these jpn writers but as soon as we got to the guild members#i didn't even have to fucking google/wiki -- i just KNEW off the top of my head#kinda fucked up tbh;;;;#anyway this list is massive but i think at least dipping my foot into some of the poems/short stories will be fun

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

How we explain the evils of the world – and the darkest parts of ourselves – has preoccupied humans throughout history. A sweeping and comprehensive search for the origins of belief in a Satanic figure across the centuries, The Devil’s Best Trick is a keen investigation into the inescapable reality of evil and the myriad ways we attempt to understand it. Instructive, riveting, and unnerving, this is a profound rumination on crime, violence, and the darkness in all of us.

In The Devil’s Best Trick, Randall Sullivan travels to Catemaco, Mexico, to participate in the “Hour of the Witches” — an annual ceremony in which hundreds of people congregate in the jungle south of Vera Cruz to negotiate terms with El Diablo. He takes us through the most famous and best-documented exorcism in American history, which lasted four months. And, woven throughout, he delivers original reporting on the shocking story of a small town in Texas that, one summer in 1988, unraveled into paranoia and panic after a seventeen-year-old boy was found hanging from the branch of a horse apple tree and rumors about Satanic worship and cults spread throughout the wider community.

Sullivan also brilliantly melds historical, religious, and cultural conceptions of evil: from the Book of Job to the New Testament to the witch hunts in Europe in the 15th through 17th centuries to the history of the devil-worshipping “Black Mass” ceremony and its depictions in 19th-century French literature. He brings us through to the “Satanic Panic” of the 1980s and the story of one brutal serial killer, pondering the psychology of evil. He weaves in writings by John Milton, William Blake, Oscar Wilde, Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Mark Twain, and many more, among them Charles Baudelaire, from whose work Sullivan took the title of the book.

Nimble and expertly researched, The Devil’s Best Trick brilliantly melds cultural and historical commentary and a suspenseful true-crime narrative. Randall Sullivan, whose reportage and narrative skill has been called “extraordinary” and “enthralling” by Rolling Stone, takes on a bold task in this book that is both biography of the Devil and a look at how evil manifests in the world.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le père a perduré dans la mémoire du fils non comme un commerçant américain ou un employé. Dans le souvenir d'Herman, Allan Melville était un gentleman cosmopolite, et le sang du comte de Melville House et d'ancêtres plus lointains, comme celui d'une reine de Hongrie et de rois de Norvège, coulait dans ses veines. Aux yeux d'Herman, son père était un des plus grands voyageurs du monde [...], un être héroïque qui lui racontait des histoires d'impressionnantes aventures maritimes et terrestres. Et plus fascinant encore : quand un Français entrait dans son magasin, Allan Melville devenait un homme profondément mystérieux, car le « Pa » familier s'exprimait alors dans une langue aussi incompréhensible pour son fils que celle parlée par Dieu.

Hershel Parker - « Herman Melville : A Biography, Volume 1, 1819-1851 » - Ed : The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHALE WEEKLY: ABOUT THE AUTHOR!

Whale Weekly has started!

Moby Dick is a novel that features themes of revenge, sexuality, man vs nature, fate and free will, the limits of knowledge, among others!

An important part to understanding and analyzing literature is knowing the author and context in which it was written.

Herman Melville (August 1st, 1819 - September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet during the American Renaissance. He was born to a wealthy father, but his death (1832) left the family in dire straits. His mother would become more religious in an effort to cope with the grief. He worked as a clerk and school teacher as a young boy, eventually taking a job on a merchant vessel when he was 20. Between 1839-1844 Melville worked periodically on whaling ships and other vessels. He jumped one ship, and participated in a mutiny on another. He lived in Polynesia briefly before joining another whaling ship, which discharged him in Hawaii. After working odd jobs for a few months he joined the Navy and was discharged October 14th 1844.

His experiences at sea and living in Polynesia were used to write multiple novels. An endeavor which his family encouraged. Herman Melville married Elizabeth "Lizzie" Knapp Shaw married August 4th, 1847 and would have two children by the time he published Moby Dick.

In 1850 Melville met Nathaniel Hawthorne, who had written reviews on Melville's books before. They had a close friendship for a few years before becoming estranged. There is evidence that Melville had romantic feelings for the friend who was fifteen years his senior.

Moby Dick was a commercial failure at the time with mixed reviews.

So as you read the book remember that Herman was a man who went from living comfortably to dealing poverty with the death of his father and the debts he left behind. He lived through the economic crisis Panic of 1837. He worked during the height of the whaling.

Sources:

Herman Melville - Wikipedia

Herman Melville | Books, Facts, & Biography

#tumblr university#tumblr book club#whale weekly#whale weekly about the author#moby dick#herman melville#call me ishmael#original content

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In don’t know Herman Melville’s biography but marveling at how he didn’t bore himself to death while writing Moby-Dick I wouldn’t be the least surprised if he did die over the unfinished pages. Ugh…

0 notes

Note

I don't know about obsession, but if i may ask...

Do you like Moby Dick because it may be based in a true story or because it's written so well??

It's certainly inspired by the true story of the Essex, which was rammed by a sperm whale. Back in the old days it was considered kind of unseemly to write pure fiction. Novels needed to be a travelogue or a biography or a historical account or a religious morality tale - at least on the surface. Pure fiction was too much like a lie, and could get you a dark reputation.

So yes, most of Melville's books were "based" on real events, either others' accounts or stories from his own colourful youth and later travels. But once you read them, you see the narrative is just an excuse for explorations of social or philosophical themes and ideas. Though his first two books were more straightforward travelogues, he couldn't afterwards write anything straightforward to save his life. His readers at the time felt betrayed by this - they'd liked his funny, scary adventures in the South Seas! - but they didn't understand the rest and stopped buying his books. Melville eventually gave up his writing career, got a day job, and died in obscurity.

I mention all this because Herman Melville the man is a big reason why I like Herman Melville's writing. His life was fascinating, sad, and we know a lot about it. It's brilliant stuff to study. His writing, too, is fascinating and sad. I'll just stick to Moby-Dick here but I love all his work.

Moby-Dick was the first novel I ever read that felt like the author was speaking directly to me. I was in high school when I first came across it - I was going through a pirate phase and it was on my list - and it stopped me dead in my tracks. It's not just a novel; it's an anachronistic multimedia experiment. It mixes prose and script and poetry and quotes and dictionary entries with elegant language and salty sailor speak. It's eloquent and disgusting, elevated and deeply down in the dirt and foam. It is an explosion of contrast, a constant seesaw back and forth between the narrative reality of a captain obsessively hunting a whale, and a common sailor named Ishmael reflecting on what that hunt means, what whales mean, what the colour white means, what the sky means, what the universe means. In his ruminations, nothing is dismissed. He wasn't dusty Hawthorne obsessing over the Bible; instead he was a sailor with a wide but naive breadth of knowledge of "Eastern religions," Asian history, "South Seas cannibals," so you never know what he's going to bring up. His was the kind of eclectic thinking that you didn't often see expressed with such eloquence in the 1850s.

So yeah, I like it a lot because it's written really well :)

But also, it's very raw, and you feel the sloppy earnestness of Melville on every page. He's trying so hard to communicate with you and - knowing that so many of his contemporaries didn't understand him - it makes you feel kind of special and connected with him when you do understand what he's saying, and you agree. It's a novel that benefits in a very unique way from NOT murdering the author; from understanding who the author was, what he went through, how exuberant he was for so long and then how much the exigencies of publishing and finances beat him down.

We people who love Moby-Dick tend to really love Moby-Dick. I'm certain Melville himself is a big reason for this. We connect with his struggles. We celebrate the immortality of all artists by raising up his work and reaching back through the centuries to take his tarry hand.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just for fun I made a page on my blog with book suggestions for Black Sails fans, but I think it’s impossible to get there on mobile and I’d like some people to actually see it so I’m making a post for it too :) Here it is under the cut. Enjoy, and let me know if there’s anything you would add to the list!

Books directly referenced within the show:

- Meditations by Marcus Aurelius – self-explanatory.

- The Odyssey by Homer – I think the translation Flint is most likely to have read is Chapman and it’s worth skimming that for a sense of the language, but if you want something more readable for a modern audience, I recommend Emily Wilson (and even if you don’t read the whole thing, her introduction where she talks about the nature of translation is really interesting).

- Don Quixote and La Galatea by Miguel de Cervantes – I haven’t read La Galatea, but it’s the one Flint leaves for Miranda as an apology. Don Quixote of course is referenced by both the Hamiltons and Madi.

- The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan – I haven’t read this either, but it’s a very influential text (referenced in both Little Women and Vanity Fair, for example, to give an idea of its wide range) so it’s good to know at least a little about it, and this post by starbuck is really good meta as to why Flint might be reading it when he’s in the fort.

- Something (possibly The Changeling) by Thomas Middleton – Again, I haven’t read this, but interesting post here by flintsmintsplint about the significance of this book choice.

- A Cruising Voyage Round the World by Woodes Rogers – Heads up this is a fairly awful read, except when he tries to describe animals, at which points he’s unintentionally pretty funny.

- The Bible I guess, particularly Genesis (quoted by both Thomas and Flint), Song of Solomon (quoted by Miranda), and Revelation (just a vibe, plus it’s briefly referenced in Treasure Island)

Other books, in no particular order, which are relevant, or which I think could give you valuable perspective or additional things to think about, or which might appeal to people who like the show:

- Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson – Duh.

- Dreams of Exile by Ian Bell – A biography of RLS. Not the best bio in the world (a little boring at times, and Bell’s fixation on RLS’s mommy kink is grating) but there are interesting points especially on the ideas of duality, identity, and the power of a place, which are so central to his fiction.

- The Republic of Pirates: Being the True and Surprising Story of the Caribbean Pirates and the Man Who Brought Them Down by Colin Woodard – A good basic source about the real people and events in Black Sails. I’m pretty certain the writers of the show consulted this book.

- Shakespeare – The Tempest seems like an obvious start (I doubt Miranda’s name was an accident) and when you’re done with that you can check out Aimé Césaire’s postcolonial reimagining A Tempest.

- Jekyll and Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson – It is unbelievable to me that no one has written a J&H fic about Flint yet. Also this story contains one of the three funniest lines RLS ever wrote in my opinion.

- The Iliad by Homer, The Aeneid by Virgil, and The Metamorphoses by Ovid

- Paradise Lost by John Milton – Check out this post.

- Frankenstein by Mary Shelley – If Flint lived a hundred years later he would have been a Romantic, I feel this in my soul, and I want to read this book in particular to him SO BADLY. Same kind of logic as Paradise Lost, except I actually like this one.

- Moby Dick by Herman Melville – There’s homoeroticism and it’s set on a ship, what more do you want?

- Why Homer Matters by Adam Nicolson – I am constantly screaming about Flint and Silver as Odysseus.

- The poetry of Elizabeth Bishop – Her poem “The Weed” is eerily reminiscent of the final silverflint confrontation(s) but honestly the rest of the collection has nothing to do with BS, I’m just in love with her and wanted to give her a rec while I have your attention.

- She Would Be King by Wayétu Moore – Not technically magical realism, because that’s a culturally specific term, but it’s like magical realism. It’s a retelling of the creation of the country of Liberia, and it is so good. I’m putting it on this list because it’s an exploration of how marginalized and enslaved people can have their own power in the face of colonization.

- The Deep by Rivers Solomon – “One can only go for so long without asking who am I? Where do I come from? What does all this mean? What is being? What came before me, and what might come after? Without answers, there is only a hole, a hole where a history should be that takes the shape of an endless longing.” Interesting exploration of community and history and generational trauma and pain and identity and the scars of white supremacy.

- A Field Guide to Getting Lost and The Faraway Nearby by Rebecca Solnit – Just vibes I guess. The second one especially has a lot of focus on stories, and if I ever write the silverflint Eros/Psyche AU that lives in my heart I’ll definitely be thinking about her words.

- Meadowlands by Louise Glück – An Odyssey-inspired collection of poems. I don’t love the book as a whole, but there are a few gems, including that one poem I’m crazy about.

- On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong – You have seen passages from this book posted on tumblr. I know for a fact that at least two (the one about drowning before meeting the other person and the one about the word monster and lighthouses) have been used in (really beautiful) Black Sails edits. I think it’s important to read the whole context. It’s intense and deeply personal. His poetry book Night Sky with Exit Wounds is also powerful – “I write things / down. I build a life & tear it apart / & the sun keeps shining. Crescent / wave. Salt-spray. Tsunami. I have / enough ink to give you the sea / but not the ships, but it’s my book / & I’ll say anything just to stay inside / this skin.”

- The Lost Books of the Odyssey by Zachary Mason – A story is true a story is untrue etc.

- From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers by Marina Warner – Such an interesting book. Definitely check out what she has to say about gossip.

- Maurice by E.M. Forster – this parallel

- Les Miserables by Victor Hugo – Some of the themes might resonate, plus maybe you’ll be inspired to read my Silver=Grantaire fic lol

- Lighthousekeeping by Jeanette Winterson – Another one you’ve probably seen used in Black Sails edits, and for good reason. The main character’s name is Silver, there are direct references to RLS and Treasure Island, and it’s a story all about stories and inner darkness and that sort of thing. Kind of a weird book structurally, but some lovely language. Also worth reading some of Winterson’s other work, especially her memoir Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?

- When Captain Flint Was Still a Good Man by Nick Dybek – A fucked up little novel which, despite the title, has almost nothing at all to do with Treasure Island. Last few sentences pack a punch.

- Folklore and the Sea by Horace Beck – Feels even longer than it is, rambling and hard to get through, and also kind of outdated (sometimes verging on offensive) – but it does have some pretty interesting sections.

- The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea by Maggie Tokuda-Hall – queer love, a genderfluid protagonist, piracy and other evils as a response to imperialism and colonialism, mermaids…

- Pirate Women: The Princesses, Prostitutes, and Privateers Who Ruled the Seven Seas by Laura Sook Duncombe – Has some issues, especially a kind of annoying girlbossy tone, but is interesting.

- Flint and Silver: A Prequel to Treasure Island by John Drake – Unlike everything else on this list, this one is actively an anti-recommendation, in case you happen to come across the title somewhere and say “oh, a book called Flint and Silver, I have to read that!” Do not do it. It is so bad.

Edited later to add:

- A Clash of Steel by C.B. Lee – a total reimagining of Treasure Island as a queer romance about Chinese and Vietnamese girls and women. I loved this book! Two particular characters from the original were merged into one character which would never have occurred to me and it was SUCH a good reveal.

- The Last Smile in Sunder City by Luke Arnold – It’s by Luke Arnold.

- When Women Were Dragons by Kelly Barnhill – About women (especially queer and otherwise nonconforming women) in the 1950s refusing to be silenced and controlled. Because they’re dragons.

- The Arabian Nights – I recommend the new(ish) version translated by Yasmine Seale and annotated by Paolo Lemos Horta, which is enormous but really interesting. This is a really foundational text that has consciously or unconsciously influenced a lot of other stories, and I don’t think it’s a leap to guess that Treasure Island, Black Sails, and some of the other books on my list are among them. Plus, here’s a quote from the introduction that might give off some familiar vibes: “Every story in the global canon of fantastical literature is in some way a vessel shipwrecked on the rocks of its misinterpretation… Assessed in these terms, One Thousand and One Nights is perhaps the greatest and most sprawling ruin of them all.”

- Cinnamon and Gunpowder by Eli Brown – Some poor bastard finds himself stuck as the cook on a pirate ship, gets his leg amputated, and falls in love with the ruthless captain. Hmm.

- A Conspiracy of Truths and A Choir of Lies by Alexandra Rowland – Explores the roles of storytellers in society through the misadventures of really fascinating unreliable narrators.

- The Drowning Empire trilogy (beginning with The Bone Shard Daughter) by Andrea Steward – a very compelling fantasy series which I initially picked up primarily because the covers look kind of like the Black Sails intro sequence

- Silver Under Nightfall by Rin Chupeco, which yes! I did look at entirely because it had Silver in the title. It’s a vampire book and it has some weaknesses BUT it’s a polyamorous romance which counts for a lot.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It was the most complete case of infanticide we ever heard of, he literally strangled his own child.”

—this is next level hating. Insane how many insults towards Herman Melville are huddled within this single page. Starting off with juxtaposing his older brother’s success against him was enough for me and then it just kept getting worse.

#my math exam went horrifically thank you for asking. yes you#the prof didn’t put half of what was on the study list onto the exam and added random Qs instead#do you want to know how many hours I’ve spent these past couple days trying to understand stupid calc II mixture volume tank problems? no?#yeah probably not#to feel better I decided to read and then I get hit in the face with this#from herman melville: a biography by hershel parker vol 2#Herman Melville

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hi there! Do you have a meta on Sara's biography but more focused on her education background?

hi, anon!

yup, here and here.

the "cliff notes" version:

since hers is a mid-september birthday, sara likely either began attending kindergarten "early" at age four (around two weeks shy of her fifth birthday) OR late at a couple of weeks before her sixth birthday (as the typical california cutoff date for kindergarten admissions is september 1st). personally, i lean more toward the earlier option, as i think it's highly likely she was probably already reading and kindergarten-ready by that age.

at some point during her elementary, middle, and/or high school years, she seems to have skipped at least two grade levels, though we don't know when or under what circumstances she did so.

however, the fact that she managed to do so is very impressive not only for the usual reasons but also considering that as a foster child, she likely moved schools/districts fairly frequently.

we know she was an advanced reader at an early age, as she reports in episode 05x21 "committed" that she read moby dick by herman melville as a fifth grader.

in episode 02x04 "bully for you," she describes herself as having been a "science nerd" in high school.

per her old cbs character biographies, sara graduated from high school as the class valedictorian at age sixteen.

shortly thereafter, she became a legally emancipated minor and left the foster care system.

at this point, she was awarded a full-ride scholarship and early admission to harvard university in cambridge, massachusetts and moved cross-country from california to attend school there.

sara most likely started her undergraduate coursework at harvard in late august or early september '88, i.e., about two or three weeks before her seventeenth birthday.

based on comments she makes in episode 01x09 "unfriendly skies," she seems to have still been at harvard in '92, which indicates that she probably took ~5 years to complete her bs there, probably because even though she was on a full-ride scholarship, she still had to work to put herself through school and build up some savings due to her unique situation as an emancipated minor with no post-graduation financial safety net otherwise.

her bs was in theoretical physics.

in real life, there is no standalone master's degree program in physics at uc berkeley—only a phd program with an optional embedded master's degree track built in—however, per her old cbs biographies, she did earn a master's degree in physics from uc berkeley (emphasis unspecified).

if one wants to try to make sense of this incongruity between fact and fiction, then one could maybe infer that she was accepted to the physics doctoral program at berkeley and completed the ma requirements before leaving school short of completing her phd (possibly due to money issues or just losing interest and diverting into law enforcement instead).

while at berkeley, sara took part in a work-study program that placed her at the san francisco coroner's office, which is the route by which she eventually found her way into the field of criminalistics after grad school.

though we don't have exact dates for her graduations from either harvard or berkeley, she was likely still pretty young at the time when she earned her master's degree (approx. 23/24 years old).

thanks for the question! please feel welcome to send another any time!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read Like a Gilmore

All 339 Books Referenced In “Gilmore Girls”

Not my original list, but thought it’d be fun to go through and see which one’s I’ve actually read :P

If it’s in bold, I’ve got it, and if it’s struck through, I’ve read it. I’ve put a ‘read more’ because it ended up being an insanely long post, and I’m now very sad at how many of these I haven’t read. (I’ve spaced them into groups of ten to make it easier to read)

1. 1984 by George Orwell

2. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

3. Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

4. The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon

5. An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser

6. Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt

7. Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

8. The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

9. The Archidamian War by Donald Kagan

10. The Art of Fiction by Henry James

11. The Art of War by Sun Tzu

12. As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner

13. Atonement by Ian McEwan

14. Autobiography of a Face by Lucy Grealy

15. The Awakening by Kate Chopin

16. Babe by Dick King-Smith

17. Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women by Susan Faludi 18. Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress by Dai Sijie

19. Bel Canto by Ann Patchett

20. The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

21. Beloved by Toni Morrison

22. Beowulf: A New Verse Translation by Seamus Heaney

23. The Bhagava Gita

24. The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews by Peter Duffy

25. Bitch in Praise of Difficult Women by Elizabeth Wurtzel

26. A Bolt from the Blue and Other Essays by Mary McCarthy

27. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

28. Brick Lane by Monica Ali

29. Bridgadoon by Alan Jay Lerner

30. Candide by Voltaire

31. The Canterbury Tales by Chaucer

32. Carrie by Stephen King

33. Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

34. The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger

35. Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White

36. The Children’s Hour by Lillian Hellman

37. Christine by Stephen King

38. A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

39. A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess

40. The Code of the Woosters by P.G. Wodehouse

41. The Collected Stories by Eudora Welty

42. A Comedy of Errors by William Shakespeare

43. Complete Novels by Dawn Powell

44. The Complete Poems by Anne Sexton

45. Complete Stories by Dorothy Parker

46. A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

47. The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

48. Cousin Bette by Honore de Balzac

49. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky

50. The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber

51. The Crucible by Arthur Miller

52. Cujo by Stephen King

53. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon

54. Daughter of Fortune by Isabel Allende

55. David and Lisa by Dr Theodore Issac Rubin M.D

56. David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

57. The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown

58. Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol

59. Demons by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

60. Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller

61. Deenie by Judy Blume

62. The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America by Erik Larson

63. The Dirt: Confessions of the World’s Most Notorious Rock Band by Tommy Lee, Vince Neil, Mick Mars and Nikki Sixx

64. The Divine Comedy by Dante

65. The Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood by Rebecca Wells

66. Don Quixote by Cervantes

67. Driving Miss Daisy by Alfred Uhrv

68. Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson

69. Edgar Allan Poe: Complete Tales & Poems by Edgar Allan Poe

70. Eleanor Roosevelt by Blanche Wiesen Cook

71. The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by Tom Wolfe

72. Ella Minnow Pea: A Novel in Letters by Mark Dunn

73. Eloise by Kay Thompson

74. Emily the Strange by Roger Reger

75. Emma by Jane Austen

76. Empire Falls by Richard Russo

77. Encyclopedia Brown: Boy Detective by Donald J. Sobol

78. Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton

79. Ethics by Spinoza

80. Europe through the Back Door, 2003 by Rick Steves

81. Eva Luna by Isabel Allende

82. Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer

83. Extravagance by Gary Krist

84. Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

85. Fahrenheit 9/11 by Michael Moore

86. The Fall of the Athenian Empire by Donald Kagan

87. Fat Land: How Americans Became the Fattest People in the World by Greg Critser

88. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson

89. The Fellowship of the Ring by J. R. R. Tolkien

90. Fiddler on the Roof by Joseph Stein

91. The Five People You Meet in Heaven by Mitch Albom

92. Finnegan’s Wake by James Joyce

93. Fletch by Gregory McDonald

94. Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes

95. The Fortress of Solitude by Jonathan Lethem

96. The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand

97. Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

98. Franny and Zooey by J. D. Salinger

99. Freaky Friday by Mary Rodgers

100. Galapagos by Kurt Vonnegut

101. Gender Trouble by Judith Butler

102. George W. Bushism: The Slate Book of the Accidental Wit and Wisdom of our 43rd President by Jacob Weisberg

103. Gidget by Fredrick Kohner

104. Girl, Interrupted by Susanna Kaysen

105. The Gnostic Gospels by Elaine Pagels

106. The Godfather: Book 1 by Mario Puzo

107. The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy

108. Goldilocks and the Three Bears by Alvin Granowsky

109. Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

110. The Good Soldier by Ford Maddox Ford

111. The Gospel According to Judy Bloom

112. The Graduate by Charles Webb

113. The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

114. The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

115. Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

116. The Group by Mary McCarthy

117. Hamlet by William Shakespeare

118. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire by J. K. Rowling

119. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J. K. Rowling

120. A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius by Dave Eggers

121. Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

122. Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders by Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry

123. Henry IV, part I by William Shakespeare

124. Henry IV, part II by William Shakespeare

125. Henry V by William Shakespeare

126. High Fidelity by Nick Hornby

127. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon

128. Holidays on Ice: Stories by David Sedaris

129. The Holy Barbarians by Lawrence Lipton

130. House of Sand and Fog by Andre Dubus III

131. The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende

132. How to Breathe Underwater by Julie Orringer

133. How the Grinch Stole Christmas by Dr. Seuss

134. How the Light Gets In by M. J. Hyland

135. Howl by Allen Ginsberg

136. The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo

137. The Iliad by Homer

138. I’m With the Band by Pamela des Barres

139. In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

140. Inferno by Dante

141. Inherit the Wind by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee

142. Iron Weed by William J. Kennedy

143. It Takes a Village by Hillary Rodham Clinton

144. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

145. The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan

146. Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare

147. The Jumping Frog by Mark Twain

148. The Jungle by Upton Sinclair

149. Just a Couple of Days by Tony Vigorito

150. The Kitchen Boy: A Novel of the Last Tsar by Robert Alexander

151. Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly by Anthony Bourdain

152. The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

153. Lady Chatterleys’ Lover by D. H. Lawrence

154. The Last Empire: Essays 1992-2000 by Gore Vidal

155. Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman

156. The Legend of Bagger Vance by Steven Pressfield

157. Less Than Zero by Bret Easton Ellis

158. Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke

159. Lies and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them by Al Franken

160. Life of Pi by Yann Martel

161. Little Dorrit by Charles Dickens

162. The Little Locksmith by Katharine Butler Hathaway

163. The Little Match Girl by Hans Christian Andersen

164. Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

165. Living History by Hillary Rodham Clinton

166. Lord of the Flies by William Golding

167. The Lottery: And Other Stories by Shirley Jackson

168. The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold

169. The Love Story by Erich Segal

170. Macbeth by William Shakespeare

171. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

172. The Manticore by Robertson Davies

173. Marathon Man by William Goldman

174. The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

175. Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter by Simone de Beauvoir

176. Memoirs of General W. T. Sherman by William Tecumseh Sherman

177. Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris

178. The Meaning of Consuelo by Judith Ortiz Cofer

179. Mencken’s Chrestomathy by H. R. Mencken

180. The Merry Wives of Windsor by William Shakespeare

181. The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

182. Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides

183. The Miracle Worker by William Gibson

184. Moby Dick by Herman Melville

185. The Mojo Collection: The Ultimate Music Companion by Jim Irvin

186. Moliere: A Biography by Hobart Chatfield Taylor

187. A Monetary History of the United States by Milton Friedman

188. Monsieur Proust by Celeste Albaret

189. A Month Of Sundays: Searching For The Spirit And My Sister by Julie Mars 190. A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

191. Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

192. Mutiny on the Bounty by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall

193. My Lai 4: A Report on the Massacre and It’s Aftermath by Seymour M. Hersh

194. My Life as Author and Editor by H. R. Mencken

195. My Life in Orange: Growing Up with the Guru by Tim Guest

196. Myra Waldo’s Travel and Motoring Guide to Europe, 1978 by Myra Waldo 197. My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult

198. The Naked and the Dead by Norman Mailer

199. The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco

200. The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri

201. The Nanny Diaries by Emma McLaughlin

202. Nervous System: Or, Losing My Mind in Literature by Jan Lars Jensen

203. New Poems of Emily Dickinson by Emily Dickinson

204. The New Way Things Work by David Macaulay

205. Nickel and Dimed by Barbara Ehrenreich

206. Night by Elie Wiesel

207. Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

208. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism by William E. Cain, Laurie A. Finke, Barbara E. Johnson, John P. McGowan

209. Novels 1930-1942: Dance Night/Come Back to Sorrento, Turn, Magic Wheel/Angels on Toast/A Time to be Born by Dawn Powell

210. Notes of a Dirty Old Man by Charles Bukowski

211. Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck (will NEVER read again)

212. Old School by Tobias Wolff

213. On the Road by Jack Kerouac

214. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey

215. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

216. The Opposite of Fate: Memories of a Writing Life by Amy Tan

217. Oracle Night by Paul Auster

218. Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood

219. Othello by Shakespeare

220. Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens

221. The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War by Donald Kagan

222. Out of Africa by Isac Dineson

223. The Outsiders by S. E. Hinton

224. A Passage to India by E.M. Forster

225. The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition by Donald Kagan

226. The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky

227. Peyton Place by Grace Metalious

228. The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

229. Pigs at the Trough by Arianna Huffington

230. Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi

231. Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain

232. The Polysyllabic Spree by Nick Hornby

233. The Portable Dorothy Parker by Dorothy Parker

234. The Portable Nietzche by Fredrich Nietzche

235. The Price of Loyalty: George W. Bush, the White House, and the Education of Paul O’Neill by Ron Suskind

236. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

237. Property by Valerie Martin

238. Pushkin: A Biography by T. J. Binyon

239. Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw

240. Quattrocento by James Mckean

241. A Quiet Storm by Rachel Howzell Hall

242. Rapunzel by Grimm Brothers

243. The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe

244. The Razor’s Edge by W. Somerset Maugham

245. Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books by Azar Nafisi

246. Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

247. Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm by Kate Douglas Wiggin

248. The Red Tent by Anita Diamant

249. Rescuing Patty Hearst: Memories From a Decade Gone Mad by Virginia Holman

250. The Return of the King by J. R. R. Tolkien

251. R Is for Ricochet by Sue Grafton

252. Rita Hayworth by Stephen King

253. Robert’s Rules of Order by Henry Robert

254. Roman Holiday by Edith Wharton

255. Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

256. A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf

257. A Room with a View by E. M. Forster

258. Rosemary’s Baby by Ira Levin

259. The Rough Guide to Europe, 2003 Edition

260. Sacred Time by Ursula Hegi

261. Sanctuary by William Faulkner

262. Savage Beauty: The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay by Nancy Milford

263. Say Goodbye to Daisy Miller by Henry James

264. The Scarecrow of Oz by Frank L. Baum

265. The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne

266. Seabiscuit: An American Legend by Laura Hillenbrand

267. The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir

268. The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd

269. Secrets of the Flesh: A Life of Colette by Judith Thurman

270. Selected Hotels of Europe

271. Selected Letters of Dawn Powell: 1913-1965 by Dawn Powell

272. Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen

273. A Separate Peace by John Knowles

274. Several Biographies of Winston Churchill

275. Sexus by Henry Miller

276. The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafon

277. Shane by Jack Shaefer

278. The Shining by Stephen King

279. Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse

280. S Is for Silence by Sue Grafton

281. Slaughter-house Five by Kurt Vonnegut

282. Small Island by Andrea Levy

283. Snows of Kilimanjaro by Ernest Hemingway

284. Snow White and Rose Red by Grimm Brothers

285. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World by Barrington Moore

286. The Song of Names by Norman Lebrecht

287. Song of the Simple Truth: The Complete Poems of Julia de Burgos by Julia de Burgos

288. The Song Reader by Lisa Tucker

289. Songbook by Nick Hornby

290. The Sonnets by William Shakespeare

291. Sonnets from the Portuegese by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

292. Sophie’s Choice by William Styron

293. The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

294. Speak, Memory by Vladimir Nabokov

295. Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

296. The Story of My Life by Helen Keller

297. A Streetcar Named Desiree by Tennessee Williams

298. Stuart Little by E. B. White

299. Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

300. Swann’s Way by Marcel Proust

301. Swimming with Giants: My Encounters with Whales, Dolphins and Seals by Anne Collett

302. Sybil by Flora Rheta Schreiber

303. A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens

304. Tender Is The Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald

305. Term of Endearment by Larry McMurtry

306. Time and Again by Jack Finney

307. The Time Traveler’s Wife by Audrey Niffenegger

308. To Have and Have Not by Ernest Hemingway

309. To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

310. The Tragedy of Richard III by William Shakespeare

311. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith

312. The Trial by Franz Kafka

313. The True and Outstanding Adventures of the Hunt Sisters by Elisabeth Robinson

314. Truth & Beauty: A Friendship by Ann Patchett

315. Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom

316. Ulysses by James Joyce

317. The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath 1950-1962 by Sylvia Plath 318. Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

319. Unless by Carol Shields

320. Valley of the Dolls by Jacqueline Susann

321. The Vanishing Newspaper by Philip Meyers

322. Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray

323. Velvet Underground’s The Velvet Underground and Nico (Thirty Three and a Third series) by Joe Harvard

324. The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides

325. Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett

326. Walden by Henry David Thoreau

327. Walt Disney’s Bambi by Felix Salten

328. War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

329. We Owe You Nothing – Punk Planet: The Collected Interviews edited by Daniel Sinker

330. What Colour is Your Parachute? 2005 by Richard Nelson Bolles

331. What Happened to Baby Jane by Henry Farrell

332. When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka

333. Who Moved My Cheese? by Spencer Johnson

334. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf by Edward Albee

335. Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West by Gregory Maguire

336. The Wizard of Oz by Frank L. Baum

337. Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

338. The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

339. The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

99 notes

·

View notes

Link

Here is ep # 2 http://www.someveryfamouspeople.com/?p=467

Herman Melville was so ahead of his time.

#herman melville#biography#moby dick#bartleby#podcasts#literature#literary criticism#Books and Literature#literary history#history

1 note

·

View note

Text

[…] Le soir du 10 décembre 1831, Allan Melvill traverse à pied le fleuve Hudson gelé. Dans son nouveau livre, Rodrigo Fresán fait de cet événement la matrice de l’œuvre à venir d’Herman Melville, fils d’Allan. À la fois roman, biographie, essai, récit poétique, Melvill mobilise une inventivité littéraire pour explorer les ressorts de la création, le poids de l’insuccès et, plus encore, les mystères de la transmission, l’amour entre un père et son fils ainsi que la faille qui s’ouvre quand le premier disparaît…[…]

Rodrigo Fresán, Melvill. Trad. de l’espagnol (Argentine) par Isabelle Gugnon. Seuil, 352 p., 23 €

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

PROCESS, ONE: A READER’S JOURNEY

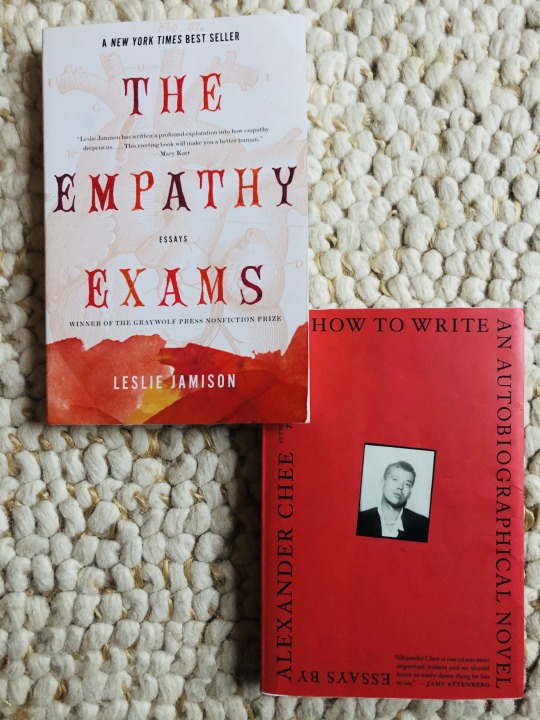

“The essays in this book were memoir until they couldn’t stand to be memoir anymore.” —Leslie Jamison

Had I read that quote even only six months ago (the book to which she refers is her much-lauded personal essay collection The Empathy Exams), I wouldn’t have known exactly what it meant.

How can a piece of writing evolve from memoir? In terms of simple, unvarnished truth-telling, I thought the memoir, as a genre of literature, was pretty much the vessel. Yet here a case is being made for something that sounds like the opposite: it seems one can go beyond even the once terminally-regarded memoir.

Let me think about this further, about my confusion. Maybe my framing is off. Maybe it’s not an issue of evolution or reduction. It’s not that the personal essay is somehow purer than the memoir, as far as autobiographical writing is concerned. The issue is not one of authenticity. It’s about application, or even misapplication, that the quest for truth for which one naturally uses the data of one’s own life could, depending on the circumstances, be more appropriately undertaken in a different genre. The two genres are merely looking at different subject matter. They’re examining completely different lifeforms on the slides, but they’re using the same authentic microscope, as it were.

I relate to the sense of frustration in the Jamison quote, that there’s a feeling that the mission she started out on—writing a memoir—became so inadequate for the real task at hand that it became unbearable, that the pressure of working under a false guise gave way to a different form of transmission.

The memoir became a personal essay collection. It had to. The questions she was exploring could not be undertaken by simply telling the story of one’s own life. Personal data was necessary for the full picture. But she needed other sources, the experiences of others, the realities of phenomena outside of her normal experience, even as they were phenomena that ultimately she ended up relating to in a deeply intimate manner. In her collection, she let us into those experiences, and then we were able to relate, by dint of her fearless storytelling and personal excavations.

Now I’m getting it: a personal essay is fixed on some question and that is what drives the exploration. Personal, say, autobiographical, details are needed for the exploration, and this can vary depending on the subject. But the focus is the external question. That is the different lifeform on the slide. It’s about the question being pursued.

I.

But first, a look at where I started on this journey, with the memoir itself.

The memoir as a work of literature was my singular focus while I was crafting my book proposal a couple of years ago. Simply put, it was what was on the table. Owing to my provenance as a musician and an actor, and my express interest in writing about my life, the genre of the memoir naturally became a thing for me.

So I dove into acquainting myself, not with examples of celebrity memoirs or memoirs by politicians—perhaps the two most popular varieties—but with examples of the finer possibilities in those genres which—big surprise—happen to be written for the most part by writers. I found myself falling in love with the exercise of memoir writing, as opposed to, say, the gratuitous voyeurism that is often offered by the popular variants of the genre.

For me, what became valuable was the quality of the writing; most of the time I was reading the life stories of people with whose work I had, outside of the memoir being read, little to no familiarity. These windows into life were captivating in their own right, these portals into raw experience, the possibilities of narration within the genre of nonfiction, the enlightened self-awareness made evident in sculpting large-scale timelines of one’s own life.

----------------------------------

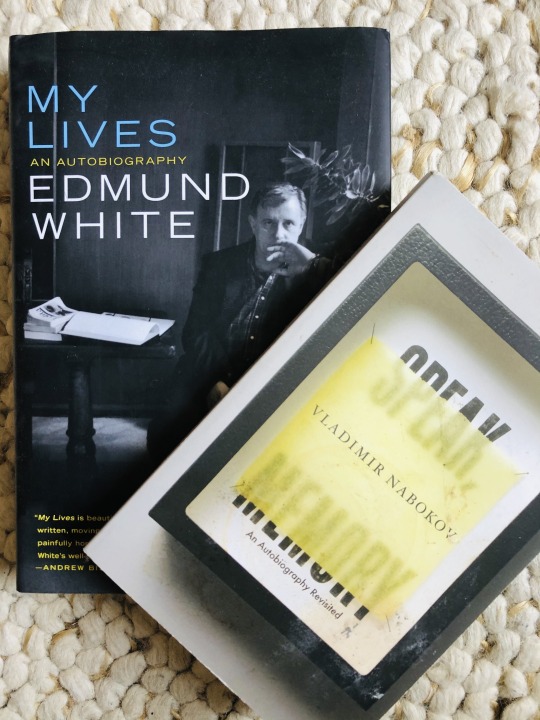

It’s difficult for me to overstate the degree to which these two books have influenced me thus far.

Nabokov’s memoir is well-known. It’s a work of literature in its own right. It is a great example of the possibilities of the memoir to accomplish something other than realism: the whole thing is a kind of Proustian meta-narrative of his childhood and abrupt departure from Russia after the revolution, like a dream of family life written down. Mary Karr, in The Art of Memoir, heads her chapter on this book, “Don’t Try This at Home: The Seductive, Narcissistic Count.” Indeed, the book reads somewhat Transylvanianly, a bold, exotic yarn full of strange characters unfurled for an audience unfamiliar with that way of life. It reads as alluring and dark, and, yes, quite vampiric. But it is also profound and gorgeous.

While it’s not really a memoir, more of an autobiography, and also not often regarded as exemplary of the form, My Lives, written by Edmund White is an incredible tour de force of portraiture of the most important people in his life, his therapists, his parents, his lovers, his friends, his subjects, they all get a chapter dedicated specifically to them. Imagine knowing a world-renowned painter who decides he wants to do a string of portraits of the most important people in his life and you are one of them. That’s what this is, in literary form. It’s less a story of him than of these people, but, by the end of the book, you, of course, end up knowing a lot about him. His ability to make you see the things that he is looking at, in a very concrete, physical way—the curves of a body, the angles of a face, the ambience of a train station—is unparalleled in my view.

Is there a difference between an (a) autobiography and a (b) memoir?

I think the difference is about scope. The autobiography is explicitly a functional genre that attempts to document a person’s entire life. It is a biography that is written by the person whose life is being written about. It does not usually try to invoke any literary devices and is intended to serve as an ancillary to consumption of the subject’s work outside of the autobiography. It is a kind of “reader” of the subject’s life. It’s main purpose is not to be written well (although if it isn’t it is a grave mistake), it is to convey the near entirety of the subject’s experience on earth.

By contrast, good writing is a bit more called-for in the memoir; otherwise the whole premise falls apart. The memoir, in carving out a specific “slice” of a person, either a period of time or some type of encounter or some activity that they always do, is explicitly intended to amplify and interrogate aspects of being. In this way, the memoir has more potential for inspiration and edification irrespective of the reader’s interest in the subject’s life outside of the memoir. This, to me, is the crucial difference.

For the most part, I am not explicitly a huge fan of the work of the writers below. But their memoirs have touched and inspired me. I don’t think I would have all that much interest in reading the autobiography of, say, Joan Didion. (I might, I can’t be sure, of course). But my point is that I’m not looking for her autobiography, whereas there’re a lot of Didion fans out there that would be waiting for said autobiography.

In this way, autobiography is a kind of fan service, whereas the memoir is a thing unto itself. It is a work of literature written for the purpose of refracting aspects of being alive. To appreciate that type of writing you need not be familiar with anything else that person has done on this planet, anymore than that it is necessary to be familiar with Herman Melville’s entire oeuvre in order to love and appreciate Moby Dick.

It was with the consciousness of the memoir’s self-sufficiency, the irony of its ability to communicate, in its more specific mode, even more broadly than the supposedly more capacious autobiography, that I continued my exploration of the genre and began taking notes for the writing of my own memoir (which is now a personal essay collection, but more on that later).

----------------------------------

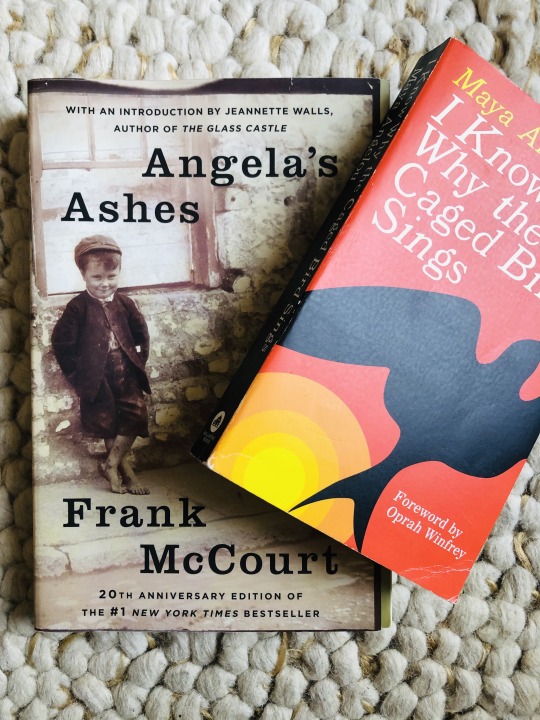

Two classics of the genre, here.

Many of us have read Maya Angelou’s book in high school. Both focus on the same thing: a period of time starting from birth and leading just up to late adolescence. Both are written like traditional first-person stories with beginnings, middles, and ends, and, were it not for our knowledge of their source material, might easily pass as romans a clef. I also think that both are examples of “misery lit,” although I think that that genre is overly hip and reductive for Angelou’s work, which is about so much more than just her misery. But they both focus on their childhood traumas in such a plain, unadorned, simple way, it is shocking and, for those of us struggling with these same issues, healing.

----------------------------------

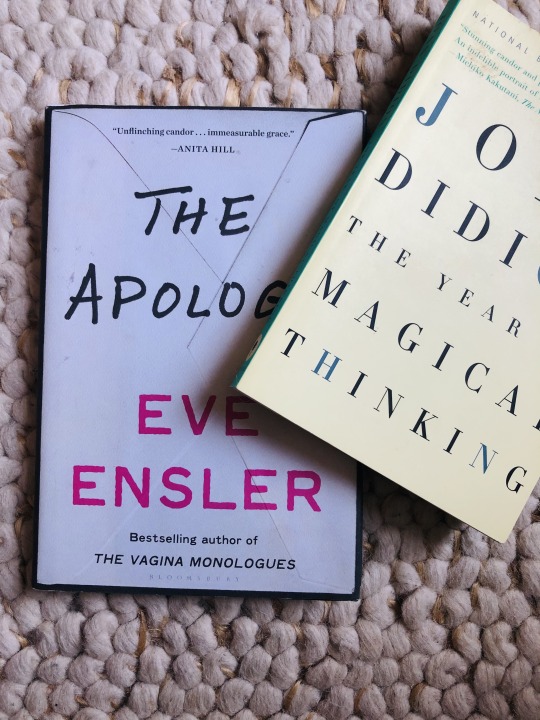

The Apology and The Year of Magical Thinking are examples of how the memoir can focus to a degree of incredible specificity. Both focus on pain but are concerned with different parts of experience. Didion writes only about one year of her life, while Ensler writes about almost the entirety of it, but with a focus on a single, prevailing experience. Both are harrowing in completely different ways and both are exquisite in the way they lift up their struggles to find meaning and truth, things that pertain to the reader’s own experiences and which he or she may also come into touch with in reading these books. They truly are gifts in that regard.

In a manner of speaking, these two books are like two, very long, book-length personal essays. They rigorously explore and interrogate their premises and do their best to extract whatever possible that is meaningful out of that exploration.

----------------------------------

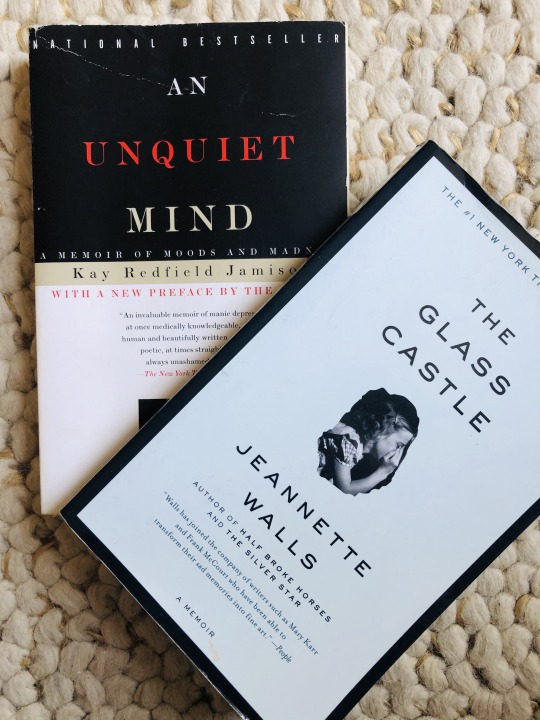

More “misery lit”! I actually don’t mean to be reductive in saying that. Both of these are fabulous stories concerning completely different encounters with mental illness and they are far beyond some hipster term of art. But there is a lot of memoir writing out there that explores the darker ways some of us were brought up and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with simply naming a certain type of writing that courageously explores how our childhoods might have been compromised.

In The Glass Castle it’s about her father’s mental illness and in An Unquiet Mind, it’s about the author’s own journey discovering and treating her bipolar disorder. Walls writes her story very much like it’s a novel, like Angelou’s memoir, and, also like Angelou, she writes it from the perspective of her child self and it is a compelling account as a result, full of tragic innocence and complicated encounters far beyond the reach of a child to properly grapple with.

Jamison’s book is very clinical, although she recounts her episodes frankly and shockingly and really brings you in to her subjective experience of insanity. These two books—not to mention Eve Ensler’s—have given me the courage to begin exploring my own encounters with mental illness and childhood trauma and to commit those experiences to writing.

----------------------------------

As I continued to research I started coming upon a very interesting type of memoir, the experimental memoir. That’s really interesting I thought. How does one write a memoir as a form of experimental art?

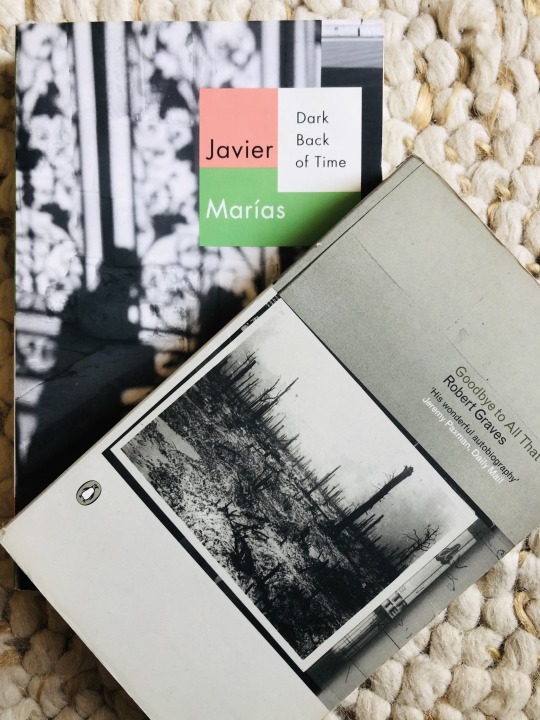

Not that this one is expressly experimental, but Robert Graves’ book is slightly off-putting in that fecund, experimental way: the bulk of it is dedicated to his experience in the trenches and it’s told with grit and harsh realism. But it starts with his schooldays and ends briefly, and curiously inconclusively, with scenes of fatherhood and tutelage. It’s a rather unique rendering of a life. Towards the end he admits that his original idea was to use the notes that he took on the frontlines for writing a novel but changed his mind after realizing that he would be desecrating his experiences and his memories and his sacrifices by layering a plot and storyline onto them. He then decided to write it simply as a factual account.

Dark Back of Time, however, is a full-on experiment in autobiography and it is always slipping in and out of reality, imagination and historicization. He spends a large amount of time writing about an old soldier who died accidentally on a hotel balcony in South America but he gets to this through talking about the reactions that his peers in Oxford had to one of his novels which they suspected made use of their lives. Truly an eye-opening experience to read autobiographical material refracted in this way.

----------------------------------

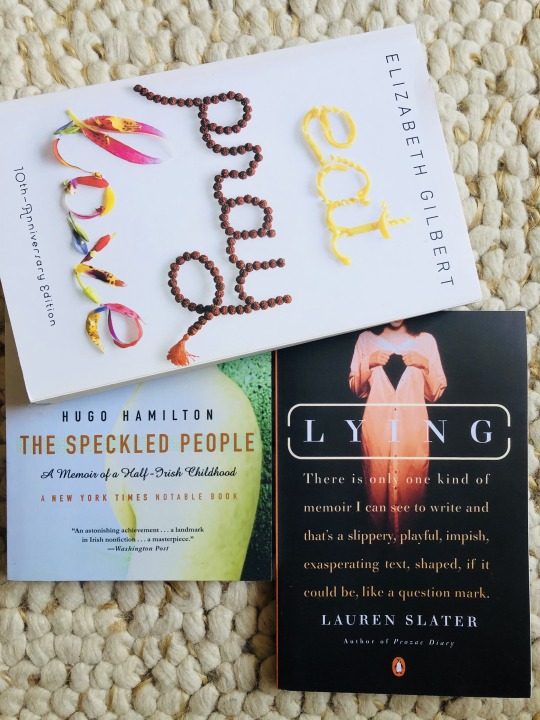

I haven’t read these three yet. They are “on deck,” as it were. Eat, Pray, Love needs little introduction, obviously. The Speckled People was highly recommended by a fellow writer and Lying came up in an online search as a prominent example of the experimental memoir.

At this point, it was already clear to me that I was writing a different kind of memoir than any of these examples. I realized that I was in effect writing personal essays without knowing it. I knew very early on that I wanted to eschew responsibility for an overarching narrative of any sort. I wanted to commit myself to specific topics that could be covered discretely in one chapter each. When I read the Graves’ passage regarding the desecration of his time on the battlefield, I thought of my own “war stories” and thought similarly that trying to give them a plot, while not exactly a “desecration,” would feel unnatural and inauthentic. What was feeling natural was to pick separate experiences in my life and devote a chapter to those I felt were strong enough for further elucidation. The time I got stuck on a mountain overnight with a friend. The shock of coming to NYU. The decision to leave the music industry. There were so many other parts of my life that seemed to deserve specific treatment in this way. I naturally started coming upon essay collections as a result.

II.

I took an online course by Alexander Chee called, “How to Write an Essay Collection” and afterwards it became much clearer what kind of book I wanted to write. I read about half of his reading list for the class and, along with the volumes I’d already dug into, I learned what a personal essay really was and what it wasn’t, and knowing this difference demonstrated to me quite clearly that the book I was writing wanted to be an essay collection in the truest sense of what an essay really is. The Leslie Jamison quote at the top of this blog post became true for me as well. My memoir could no longer stand being a memoir and had become a personal essay collection.

During the class, Alexander Chee recounted an irony regarding his own personal essay collection. He said that he found it curious when readers of his book would tell him that they found so much of him in it. “There’s actually not very much of me at all,” he said; and he mentioned this in order to illustrate what a personal essay collection is and what it isn’t. The reason why there’s not that much “of him” in his essay collection, nor, for that matter, why there isn’t much of any author’s life in any of their personal essay collections, is that a personal essay, despite being “personal,” is primarily geared towards externals not internals. “Pity the personal essayist,” the author Sloane Crosley writes in her New York Times review of Jamison’s latest essay collection, Make it Scream, Make it Burn, “fated to play with a reader’s tolerance for that most cursed of vowels. Too many “I”s and you’re self-absorbed; too few and: Where are you in this piece?”

Self-absorption as a liability in writing is understood enough, though, when it comes to autobiographies and memoirs, the liability becomes unavoidable and, if anything, necessary. We read those books exactly for the purpose of the big drop into an author’s psyche, willingly diving down the subjective abyss, basically swimming in “I”s (the best ones allow us to do this gleefully).

Not so in a personal essay, where the restriction on egoistic license holds. And yet: how do we include and implicate ourselves into the topic? without stepping on traps of self-absorption? This is what Chee was talking about when he said that there wasn’t much of him in his essays: not that he didn’t implicate himself in his narrations—he very much did—but that he skillfully observed this precarious balance.

That balance is undertaken quite differently depending on the author (and in my synopses of the collections I’ve read recently I’ll try to speak about how they’ve assigned “percentages of self” into their essays, what the “lean-to-fat" ratio is, for example, when “fat” could be understood as the strictly autobiographical portion of the essay). It can also vary according to the essay. In some cases it’ll be necessary to fully implicate oneself. In others, perhaps only a passing mention of the author’s impression of the events is needed. But there’s an essential aspect to what makes for a great personal essay, irrespective of ratios of personal to objective, that Charle’s D’Ambrosio captures beautifully in the introduction to his own essay collection:

My instinctive and entirely private ambition was to capture the conflicted mind in motion, or, to borrow a phrase from Cioran, to represent failure on the move, so leaving a certain wrongness on the page was OK by me. The inevitable errors and imperfections made the trouble I encountered tactile, bringing the texture of experience into the story in a way that being cautiously right never could.

This is kind of a Copernican revolution to me. I mean, it had never really occurred to me that you could be wrong and that would be a good thing. In writing I had always striven to make sure that I didn’t insult researchers, journalists, experts and scholars by misrepresenting the truth. Yet, here was basically a license to get it all wrong and admit it on the page and have that be a virtue of the writing.

What this tells me is that what remains key in the personal essay is not some authoritative stance, but the very uncertainty of the perspective, and how that might invite opportunities for a much more intimate relational structure with the topic matter on the part of the reader. This isn’t about ingestion (of data, of info, of ideas, etc.) but about contact. I see that as being very similar to the relationship between reader and author in a memoir, this premium on relation. The only difference—and for me, a very consequential one—is that the primary target of a personal essay’s sight is not the self qua self, but some implication with the content of reality on the part of the self. That intersection is what fascinates me more at this time than simple self-narration.

In this way, a personal essay can kind of be like a stop sign, a signal to halt the gyrating (mostly online) world, with its hyperlinks and ads and other pseudo-references. In fact, in his brilliant collection Proxies, Brian Blanchfield takes on this very task and turns the internet off when writing each of his essays in the collections. In order to take solace within the much more subjective account housed within the pages, an account at once open and tentative, based as it is in doubt, and hermetically sealed, shunning the greater world’s insistence on certification and realism, the essay becomes a prismatic utility for investigation, where perspective and subjectivity are king and certainty and objectivity are actually limiting.

The memoir offers something very direct to the reader: the author’s own struggle with, or journey through, some issue or period in life. The author is the chief protagonist in the drama, the star of, say, the cinematic adaptation of the book. The issues swirl around the protagonist but the camera stays trained on him or her. What I started to notice was that my mental gaze was always scudding away from the protagonist (me) and over to what else was in the frame. And so the personal essay as I began to learn about it became a much more appropriate vessel for these concerns, even as I knew that I would need to implicate myself in the action, keep myself in the frame. Striking that balance in a way that is both specific to me and my experiences and yet observant of the proper limits of the genre, so as not to veer away and “regress” back into memoir, has become my chief objective with each of the essays that I’ve been writing.

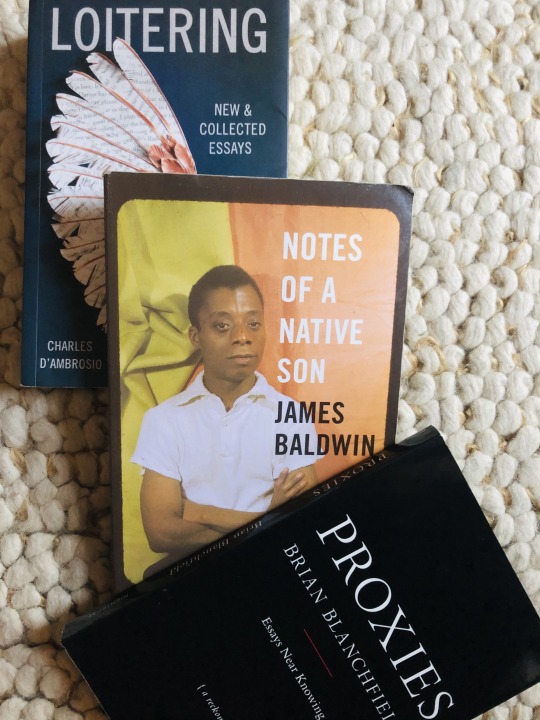

----------------------------------

These three collections might be my bible for this project. Each are very different in style and application, but each is similar in that joyous experience of reading a paragraph and being so stunned by the insight that one has to turn the face away from the page for a moment (or two) to let it sink in. Baldwin is, of course, the king of this sort of thing. There were times while reading his essays when I actually had to straight up close the book and put it down in order to absorb what was going on. The title essay which is about Harlem, his father, and his early awakening to the depth of his country’s racism, is perfection on both the level of content and form. It does what an essay does best: leave you with the unequivocal residue of human feeling twisting around the grander issues with which that essay is concerned.

Each essay, in all of these volumes, is like a discrete nugget, a piece of writing, contiguous, open and alive, that can be read and reread, like an oracle you visit throughout your life, which, using the same words, speaks to you anew each time.

Ambrosio’s essays are absolutely nimble and virtuosic; his language is muscular and sinewy; his sentences are lean and long and you can ride them effortlessly and when you finish them and their paragraphs, you are left with an image of a truth that was planted in your sight without you knowing. It’s an exhilarating experience.

Blanchfield’s essays are a revelation of subjectivity. This volume was part of Chee’s reading list and I can’t express enough gratitude for having been directed to it. Perhaps Blanchfield is the master of nesting the autobiography within the confines of an essay. When he toggles between the external and the internal, you don’t notice it. It’s effortless. His ability to tell a giant story in one paragraph is inspiring. The tone and delivery is somewhat sacral, he’s a poet, after all. But it is also delicate, graceful, poised and elegant. And deeply personal. How someone can title an essay “On Frottage” and turn the reader’s attention to the true significance of the topic—AIDS and the gay scene in the 80s and 90s—and all of the social significance intertwined in it, along with implicating himself in a nakedly autobiographical way, is beyond me, but I am happy to be in the audience for it.

----------------------------------

What I love about these two collections are their stealth and form. Their stealth comes from how they read, not so much as casually but as without artifice or adornment, and how this aspect lets the reader’s guard down, only to have some extremely penetrating conclusion arrive at the end of each essay, in a manner that the more plainspoken style did not necessarily anticipate. Chee’s prose particularly comes across as either supremely and dryly witty or as modest plainness, but when you finish one of his essays the takeaway is anything but those things; it is profound. Jamison as well. As for their form, they tend to do some adventurous things. One of Jamison’s essays uses a kind of diagram of storytelling which she learned in a writing class to “tell the story” of a traumatic episode involving a horrific episode of violence she experienced in South America. The essay is called “The Morphology of a Hit.” It’s a perfect example of something else that I really love about personal essays which is their ability to take leaps in form when that form enables a type of storytelling that otherwise isn’t possible. Chee does this very thing in a somewhat humorous essay, the titular one of this volume, which is just a long list of life hacks and writing tips. I’m really grateful for the insight that this man has given me into the writing process. My copy of his book is signed, as I first became aware of him at a reading of his with Edmund White at NYU which my good friend invited me to. So I’m very grateful to that friend as well! He also introduced me to Edmund White so it’s a double whammy!

----------------------------------

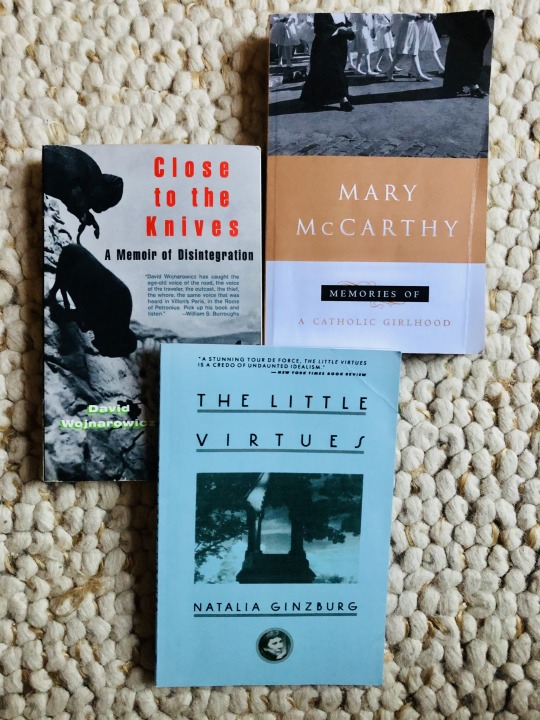

I would’ve never encountered these collections of my own volition without their inclusion on the reading list in Chee’s course, but I’m very happy that I read these. McCarthy’s essays are quite old, dating to the 50s and 60s, I believe, when they were originally published in The New Yorker. They’re all centered around her childhood years, either living with her grandparents or in an orphanage and they are remarkable portraits of intimacy and observation. The same with Ginzburg’s collection, although she writes in a much more enigmatic style. What inspired me most about her essays was how simultaneously aloof and vulnerable they are: she has a way of, say, writing about England, without ever even mentioning the name of the country, yet contriving a recognizable and incisive portrait of it, all from the vantage point of her own experience of the country during a certain time. Finally, there’s really nothing quite like Wojnarowicz’ book. It’s slightly Beat in tone, sometimes surreal and ecstatic, and then progressively more plainspoken and political. But it is all so very raw and pulsing with the heat of experience and desperation and anger. Wojnarowicz was an incredible artist, a sculptor and photographer and he lived in the East Village of the 80s and reports from the frontlines on the AIDS crisis. His work bears the stamp of a deeply tuned in artist confronting the hypocrisies and injustices of his time.

----------------------------------