#Irish historian

Text

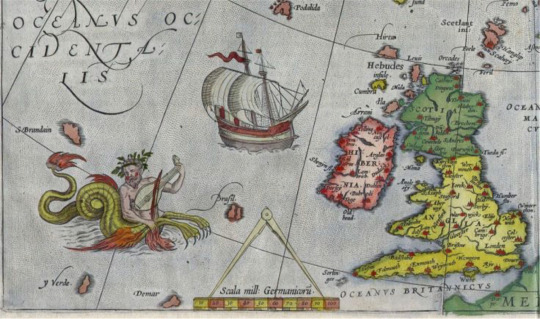

Hy Brasil | The Lost Legendary Island of Ireland

Hy-Brasil was an island which appeared on ancient maps as early as 1325 and into the 1800s. On most maps, it was located roughly 321km (200 miles) off the west coast of Ireland in the North Atlantic Ocean. Its name is derived from Old Irish hy, a variation of í, meaning ‘island’, and brasil, from the root word bres, meaning ‘beautiful/great/mighty’. It has also been explained as coming from Uí…

View On WordPress

#Angelino Dulcet#Hy-Brasil#Ireland#Irish historian#Irish language scholar#Island#John Nesbitt#John O’Donovon#Legendary#Lost#Morrough Ó Laoí#Ogygia#Promised Land#Ruairi O’Flaherty

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The arrival of Lugh to the court of the Tuatha Dé Danann 💫

(This is my November postcard! If you’d like to be sent one, you can sign up here)

#irish mythology#artists on tumblr#illustration#amylouioc art#celtic mythology#fantasy illustration#lugh#nuada#tuatha de danann#celtic polytheism#praying the fidchell historians don’t kill me#The Coming of Lugh

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

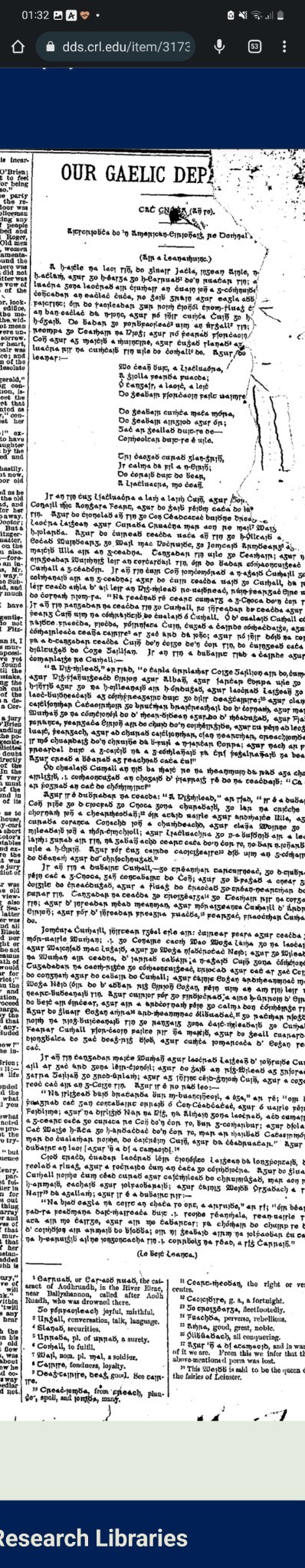

A Call to all Celticist, Historians , Academics, Hobbyists ECT for a Edition of Cath Cnocha

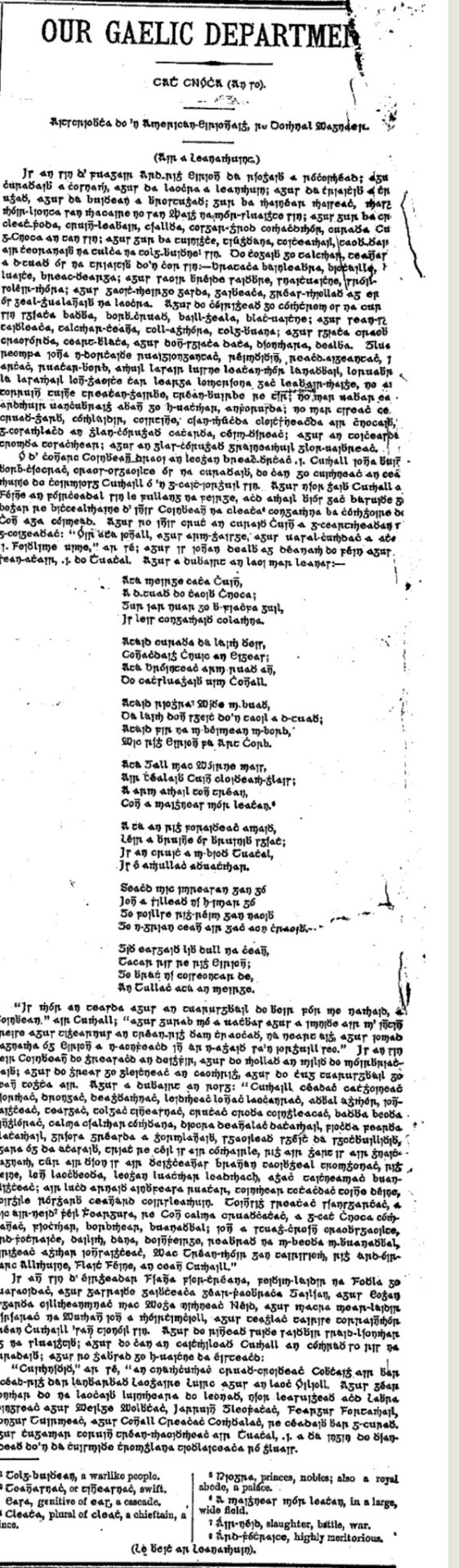

Attached to this post are screenshot of a transcript of a now lost manuscript of the literary version of the Cath Cnucha (Battle of knock) known more famously from its older cousin the Fotha catha Cnucha. This transcription is from the Irish-American newspaper issues October 1884 to January 1885.

The transcription seems to present a version of the story of the battle between Tadg mac Nuada and Cumhall mac Trenmoir with detail not found elsewhere as well as information on the conception of Fionn Mac Cumhaill

The literary version of Cath Cnucha remains critically unedited, and as far as I am aware outside of manuscripts, this transcription is the only treatment it has gotten despite folk versions being widely available in publication. It is, in my opinion, a tragedy that this Fenian cycle text remains unavailable for the reading of the modern public. This leads me to a threefold request for all who are willing to listen. These are three fold , firstly to all those in the US with access to libraries that may contain this newspaper and its issues please check if these issues are in better condition and avaliable please transcribe what is illegible or damaged in the scanned copies. The publication issues with damaged or inaccessible text are

4th October 1884

11 October 1884

18th October 1884

6th December 1884

20th December 1884

If the missing portions of the transcription can be recovered it is my hopes to make them freely avaliable online for the end goal of it being easier.

For those who understand early modern Irish orthography, I ask you to aid in the transliteration what is here to modern Irish orthography. The second would be for translation into modern Irish which from there we could translate to English.

The end goal is to make a freely avaliable none critical edition of the text to at least allow it to be studied or enjoyed by a broader audience. I, however, lack the skill to do it myself and am seeking the aid of others in this endeavour. I am no trained celticist. I am simply a folklorist and historian who recognises his limits. Please reblog to spread the word. I understand this is unusual but I am passionate about the fenian cycle enough to pursue this.

For those currently pursuing a masters or doctorate in celtic studies an edition of Cath Cnocha would be valuable to the field according to me

These screenshots are based on the scans from the central research library and are damaged or incomplete. Each can be found on

#irish mythology#folklore#mythology#medieval#manuscript#early modern#please help#gaelic mythology#celtic#celtic mythology#legend#myth#academics#history#historian

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

All right, time to talk about the Maines. I apologise that this is so delayed -- I've had terrible pain-related brain fog lately, but today I can at least think, even if I'm typing this from bed because sitting up at a desk is Bad.

A couple of weeks back, a friend sent me this AskHistorians question:

This is very much my area of expertise, but I don't use Reddit, so I said I'd answer it here, for the benefit of @llwhn (and anyone else who is interested).

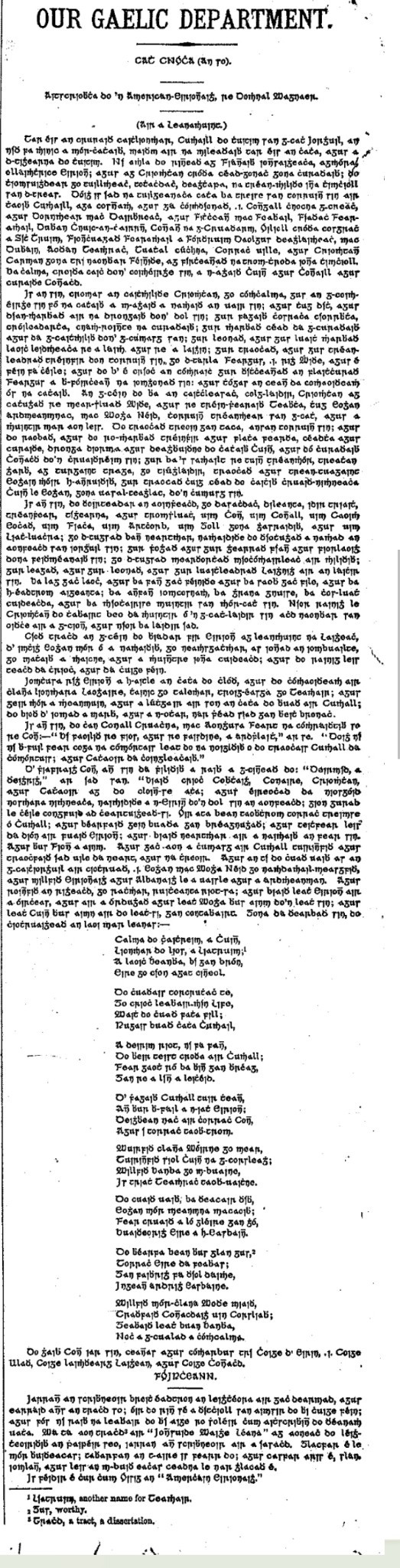

First of all, context: I published an article about the seven Maines in Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 83 last year, which is one of the only pieces of research published on the topic in recent years. Unfortunately, I can't share this article online due to the copyright restrictions of the journal, but it's my research there that I'm drawing on. The Maines are a complicated bunch -- although we're told there are seven of them, they actually number between six and eight in any given list, and their names vary noticeably.

To show how much they vary, let me show you the table I produced for my CMCS article:

As we can see here, there’s considerable variation in a) how many of them there are, b) what their names are, and c) what order the names are in. This last point might not seem important, but it’s going to come up later.

Now that we’ve had a chance to appreciate that the ‘seven’ Maines are a far more complicated bunch than they appear, let’s get down to the specifics of your question. You wanted to know whether Maine Cotagaib-Uile’s epithet is implying that he’s nonbinary (or perhaps intersex?), especially as it talks about inheriting traits from both parents. This is a really interesting question, and not one I’d thought about before – surprising, since I also work on queer readings of medieval Irish texts. Having thought about it for a while, I don’t think that’s what’s being suggested here, but let’s look at it in more depth.

‘Cotagaib-Uile’ is probably the epithet to have received the most attention of those in this list, although given how little has been published about the seven Maines, that isn’t saying too much. This is interesting, because as you can see, it’s not in all of the lists, and some of the omissions are significant.

Quick Maine backstory: in some traditions, we’re told that the Maines originally had different names, and were renamed because of a prophecy Medb was given that her son Maine would kill Conchobar. She had no sons called Maine, so she renamed all of them (and one of them ends up killing a Conchobar, but not the one she wanted dead). This story is found in Cath Boinde / Ferchuitred Medba, as well as in a couple of manuscript fragments by itself; the first four columns of the table above show the lists of names given there.

In fact, let’s have another table, this time showing the ‘original’ names of the Maines and the epithets they were given when renamed, according to these four manuscripts:

Yep. As we can see, these manuscripts can’t agree on anything, which is funny, since they’re all versions of the same text. It just goes to show what a complicated question the Maines’ epithets offer. The fact that Cotagaib-Uile isn’t in this list is interesting, though, because some scholars have attributed quite a lot of importance to this name.

Introducing: Sir John Rhys. John Rhys was the Jesus Professor of Celtic at Oxford in the 19th century, and yet despite this distinguished academic background, managed to write a lot of absolute nonsense. That’s the 19th century for you! Rhys has the dubious honour of at least being creative in his wildly unsupported arguments; I love the confidence with which he’ll assert “this undoubtedly means X” when there is definitely a great deal of doubt and in fact it almost definitely doesn’t mean X.

Rhys is, however, one of the only people apart from me to have spent much time looking at the names of the Maines, so I was forced to consider his arguments for a while when I was writing this article. As we’ve seen above, there are often more than seven Maines, and Rhys, who had a theory that the “secht Maine” represented the days of the week (“sechtmain”), was keen to understand why there might be eight of them. He said that the epithet ‘Condagaib-Uile’ should be read as suggesting that this Maine ‘contained or comprehended all the others’. In this way, he’s functioning as a ‘superlative eighth’ to the seven – all the others are contained within him, just as sometimes triads give three examples of something and then a fourth that’s better than all of them.

But that’s not what the explanation given in Táin Bó Cúailnge suggests it means, is it? Now, I’ll note that Faraday’s translation is pretty old, and I wouldn’t generally use it. However, I pulled out Cecile O’Rahilly’s translation of the same line, and it’s pretty similar:

‘Their names are Maine Máthramail, Maine Aithremail, Maine Mórgor, Maine Mingor, Maine Mo Epirt, who is also called Maine Milscothach, Maine Andóe and Maine Cotageib Uile—he it is who has inherited the appearance of his mother and his father and the dignity of them both’

Cóir Anmann, a treatise on names, gives an explanation that seems to encompass Rhys's interpretation while saying the same thing as TBC:

‘who includes them all’, ‘i.e. had the appearance of his mother and father. For he was like them both’ (trans. Sharon Arbuthnot)

It's clear that even when Cotagaib-Uile is referring to "them all", it's not quite in the manner that Rhys argued, so his interpretation isn't particularly convincing. (He also attributed a lot of important to Cotagaib-Uile being the last in the list, which we can see very clearly from the table above is not always or even mostly the case.)

Instead, it definitely seems to be the “appearance” of both mother and father that the text claims Maine has inherited. Let’s look closer at that, because we don’t want to be misled by translations. Faraday uses ‘form’ instead; the difference there is negligible, but it might be significant, if we’re trying to read into this regarding gender and bodies.

The Irish word in TBC is ‘cruth’ meaning form, shape, appearance; beauty of form, shapeliness. It does refer to physical appearance, but it doesn’t seem to be a particularly gendered term referring to physical traits. There is no evidence, for example, that this is implying an intersex body containing both male and female traits. The simplest way to read this is just “he looks like both his parents”, which is a normal thing to say about somebody.

Moreover, it’s worth considering this name in the context of two of the other Maines in the list:

Aithremail, ‘like his father’, ‘i.e. he was like his father, i.e. like Ailill son of Máta’

Máithremail, ‘like his mother’, ‘i.e. he was like his mother, i.e. like Medb daughter of Eochaid’ (again from Cóir Anmann, translated by Sharon Arbuthnot)

If one brother takes after their father, one takes after their mother, then suggesting that a third brother might take after both of them doesn’t seem like a particularly loaded statement.

Indeed, if it was a loaded statement, we would expect these Significantly Gendered Traits to show up somewhere else. After all, Maine Mingar and Maine Mórgar get a whole story in which the “duty” (gar) of their names is positioned as central – that’s Táin Bó Regamain. So we might think there was a story in which taking after Medb or Ailill was significant, but there’s certainly no surviving story in which that happens.

That doesn’t mean there never was a story in which that aspect of their epithets was emphasised, but although Maine Mathremail and Maine Athremail are present in every list (a rarity among the Maines), I’m not aware that they ever get to take a starring role in any text that survives today. Likewise, there isn't a story in which Cotagaib-Uile’s superlative or combinatory nature is foregrounded.

All of that is a very long winded way of saying that I don’t think they are implying anything about this Maine’s gender: I think they’re simply saying that he has inherited traits from both Medb and Ailill. Since Medb is notorious for behaving in an “unwomanly” manner by trying to lead armies into war and so on (something some medieval authors were not impressed by), this also probably isn’t suggesting any of those traits were especially feminine.

But. That doesn’t mean this epithet, and the textual explanation given for it, doesn’t create space for a nonbinary reading of Maine. I’m all in favour of exploring queer possibilities regardless of the authors’ intentions. I think it would be challenging to argue for a trans reading overall simply because Maine Cotagaib-Uile does nothing else in the text except be included in this list, and therefore has no personality or behaviours to draw on, but that doesn’t mean you couldn’t choose, in your own creative or exploratory works, to explore nonbinary possibilities.

Moreover, although I don’t think this Maine is being portrayed as ambiguously gendered on purpose, Táin Bó Cúailnge is not a text where gender binaries are neatly demarcated and always maintained. Crucially, Cú Chulainn himself is a deeply ambiguous figure whose masculinity is constantly questioned, undermined, and problematised by those around him, and his own behaviour challenges their assumptions and their definitions of 'man'.

As people who follow me here know, I have an article which will be available in the next month or two about the ambiguities of Cú Chulainn’s gender and what this says about TBC as a text. I tend towards a transmasculine reading, and suggest one in this article, but that’s certainly not the only possibility. The value of queer and gender theory is that once you start dismantling assumptions about gender in this story, you can have a lot of fun looking at how it’s actually being constructed, rather than just how we assume it’s being constructed.

So I definitely think there’s potential for exploring more facets of gender in TBC than the ones that have already been discussed (by me or by others). And perhaps looking at epithets like this and what they tell us about personalities, appearances, and gender would be a good place to start – because clearly, medieval authors didn’t think it remarkable that a son could inherit the appearance or nature of his mother, or neither Maine Mathremail nor Maine Cotagaib-Uile would have the epithets that they do.

tl;dr: This passage in Táin Bó Cúailnge is probably not implying that the character in question is nonbinary, but there is lots of space for queer readings of this text.

For further reading on the seven Maines and the meaning of their epithets, you might enjoy my CMCS article; there’s a link on my website, which is also where I will also upload the article about Cú Chulainn and gender as soon as it’s available.

I hope this has been useful/informative, and I’m sorry it took me so long to get to it!

#6-8 assorted maines#tain bo cuailnge#the tain#the seven maines#medieval irish#ulster cycle#ask historians

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Emma Donoghue

Gender: Female

Sexuality: Lesbian

DOB: 24 October 1969

Ethnicity: White - Irish

Occupation: Playwright, historian, writer, screenwriter

#Emma Donoghue#lesbianism#lgbt#lgbtq#wlw#female#lesbian#1969#white#irish#playwright#historian#writer#screenwriter

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recap of the Irish War of Independence

One cannot talk about or understand the Irish Civil War without understanding the Irish War of Independence. In fact, I’ve seen more and more historians argue that we can think of the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War as one big civil war, since the Royal Irish Constabulary, the IRA’s main enemy before the Black and Tans arrived, were Irish themselves and IRA intimidated, harassed, and executed Irish people who they considered “informers and traitors.” Additionally, many of the hopes, dreams, and aspirations initiated by the women’s liberation moment of 1912, the Lockout of 1913, and Easter Rising were further refined by the Irish War of Independence, and contributed to the violent schism in Irish Society following the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. These aspirations and goals would further be redefined by the Irish Civil War with participants of all sides feeling like they lost more than they gained from the entire affair.

Thus, why I feel it’s important to recap the major events of the Irish War of Independence

Leading Up to the Irish War of Independence

Ireland has always been a place of debate, uprisings, and desire for change, but in the early 1900s there were three movements that paved the way for the Irish War of Independence: the Suffragette Movement of 1912, the Gaelic Revival, the 1913 Lockout, the Home Rule Campaign and Easter Rising. I’ve discussed all four movements in great detail in the first season, but in summary, the Suffragette Movement, the Gaelic Revival, and the 1913 Lockout created an environment of mass organizing and brought together many activists and future revolutionaries. The Home Rule Campaign, combined with WWI, created the conditions for a violent uprising.

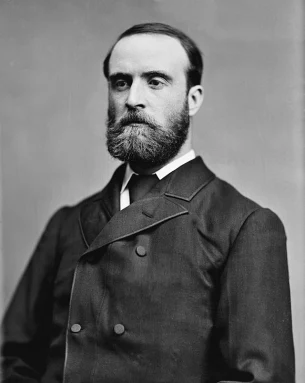

Charles Parnell

[Image description: A black and white photo of a white man with a high forehead and a thick, round beard. He is wearing a white button down and black tie and a grey double breast jacket.]

British Prime Minister Gladstone introduced the concept of Home Rule in 1880, with support from one of Ireland’s most famous statesmen: Charles Parnell. The entire purpose of Home Rule was to grant Ireland its own Parliament with seats available to both the Catholic majority and the Protestant minority and current power brokers). However, Parnell destroyed support for Home Rule by being involved in a messy and scandalous divorce and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), the precursor to the Irish Republican Army (IRA), scared the British government with their terrorist attacks. Home Role went through another failed iteration, but John Redmond was confident he would get the third iteration passed. This newest iteration was introduced to Parliament in 1914 and have created a bicameral Irish Parliament in Dublin, abolished Dublin Castle (the center of British power in Ireland), and continued to allow a portion of Irish MPs to sit in Parliament. It was supported by many nationalists in Ireland, barely tolerated by the Asquith Administration, and despised by the Unionists.

The Unionists believed they had a reason to worry. They had not forgotten the Protestants slaughtered during the 1798 Uprising nor the power they lost through the machinations of O’Connell and Parnell. Facing a massive change in their lives should Home Rule pass, the Unionists took a page out of the physical force book and created their own paramilitary organization: the Ulster Volunteers. The Asquith government knew of the Ulster Volunteers, their gun smuggling, and their drilling, but did nothing except delay Home Rule as long as possible.

Asquith’s delaying tactics and the creation of the Ulster Volunteers made Irish Nationalists nervous and they took matters into their own hand. Arthur Griffith, an Irish writer, politician, and the source of inspiration for many young rebels created the political party, Sinn Fein. Griffith argued for a dual monarchy approach, similar to the Austrian-Hungary model. He believed Ireland and England should be separate nations, united under a single monarchy. He also introduced the concept of parliamentary absenteeism i.e., Sinn Fein was a political party that would never sit in British Parliament, because the parliament was illegitimate.

Eoin MacNeill

[Image description: A black and white picture of a tall man in a courtyard. He has a high forehead, wire frame glasses, and a shortly trimmed beard. He is standing with his hands behind his back holding a hat. He is wearing a white button down, a tie, a vest, and a suit jacket and grey pants.]

In response to the Ulster Volunteers, Eoin McNeill and Bulmer Hobson created the Irish Volunteers. Both men believed that the Irish wouldn’t stand a chance in an uprising against the British government and their best bet was to trust Redmond to pass Home Rule. The Irish Volunteers were created in order to defend their community from Unionist attacks. Things were tense in Ireland, but it seemed that parliamentary politics could save the day and the extremists would be pushed to the sidelines.

Then World War I began.

The British used the war to pass Home Rule but delay it taking affect for another three years. To add insult to injury, John Redmond encouraged young Irishmen to enlist in the British Army and fight for the Empire. McNeill and Hobson tried to convince its members to continue to trust Redmond, although they were angry that he was recruiting for the war. Yet, there was a handful of Irish Volunteers, who were also members of the resurrected IRB believed England’s difficulty, Irish opportunity.

They were Tom Clarke, Sean MacDiarmada, Padraig Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh, Eamonn Ceannt, and Joseph Plunkett. These men, plus James Connolly of the Irish Citizen Army, would sign the Proclamation of the Irish Republic and it would serve as their death warrant.

They knew they would not be able to win without arms and support, so, keeping their plans to themselves, they sent Roger Casement to Germany to present their plans for a German invasion that would coincide with an Irish rising. The Germans rejected this plan (maybe remembering what happened in 1798, when the French made a similar landing, weeks after a massive Irish uprising), but promised to send arms.

The Irish Volunteers were often seen drilling and practicing for some vague rebellion, so it wasn’t suspicious to the authorities or to MacNeil and Hobson to see units marching around. When Pearse issued orders for parade practice on April 23rd, Easter Sunday, MacNeil and Hobson took it at face value while those in the know, knew what it really meant. This surreal arrangement would not last for long and the committee’s secrecy nearly destroyed the very rising it was trying to inspire.

The first bit of trouble was Roger Casement’s arrest. The Germans were less than supportive of the uprising, and Casement boarded the ship Aud to return to Ireland to either stop or postpone the rising. However, when he arrived in Ireland on either April 21st or 22nd, he was pick up by British police and placed in jail.

Pearse Surrenders

[Image description: A faded black and white photo of three men standing on a street in Dublin. There are two man on the left and they are wearing the khaki cap and uniform of the British army. On the right is a man wearing a wide brim hat and a long black jacket]

Then MacNeil and Hobson had their worst suspicions confirmed-Pearse and his comrades were secretly planning a rebellion without their support. MacNeill vowed to do everything (except going to the authorities) to prevent the Rising and sent out a counter-order, canceling the drills scheduled for Sunday. This counter-order took an already confused situation and turned it into a bewildering disaster. Units formed as ordered by Pearse and dispersed with great puzzlement and some anger and frustration. Pearse and his comrades met to discuss their next steps and decided the die had been cast. There was no other choice except to try again tomorrow, Monday, 24th, April 1916.

Easter Rising was concentrated in Dublin with a few units causing trouble on the city’s outskirts. The Irish rebels fought from Monday to Friday, surrendering Friday morning. The leaders of the rising were murdered, but many future IRA leaders such as Eamon DeValera, Michael Collins, Richard Mulcahy, Constance Markievicz, Liam Lynch, and others survived. They were sent to several different prisons, the most famous being Frongoch where Collins was held. The IRB turned it into a revolutionary academy and practiced their organizing and resistance skills while formalizing connections and relationships. When they were released starting in December 1916, they were ready to take those skills back to Ireland.

Creation of the IRA and the Dail

Their approach was two pronged: winning elections and rebuilding the Irish Volunteers/ Irish Republican Brotherhood.

When the prisoners were released, the Irish population went from hating them for launching a useless rebellion to cheering their return. The English helped flame the revolutionary spirit in Ireland by proclaiming Easter Rising a “Sinn Fein” rebellion and arresting many Sinn Fein members who had nothing to do with the Rising. This made it clear Sinn Fein was the revolutionary party while John Redmond’s party was out of touch.

Eamon de Valera

[Image description: A black and white photo of a white man with a sharp nose and large, circular glasses. He has black hair and is wearing a white button down shirt, a polka dotted tie, and a grey suit.]

Sinn Fein ran several candidates such as Eamon DeValera, Michael Collins, and Thomas Ashe. Ashe would be arrested while campaigning and charged with sedition. While in jail, he went on hunger strike and was killed during a force feeding. Following an Irish tradition, Sinn Fein and the IRB turned Ashe’s funeral into a political lightning rod. They organized the funeral procession, the three-volley salute, and Collins spoke over Ashe’s grave: “There will be no oration. Nothing remains to be said, for the volley which has been fired is the only speech it is proper to make above the grave of a dead Fenian.”

On October 26th, 1917, Sinn Fein would hold their first national convention. During the convention, Eamon DeValera replaced Arthur Griffith as president and Sinn Fein dedicated itself to Irish independence with the promise that after independence was achieved the Irish people could elect its own form of government. However, there was still tension between those who believed in passive non-violence and the militant Sixteeners. 1917-1918 was spent building a bridge between parliamentary politics and militant politics of the 1920s, with Sinn Fein’s large young membership pushing it in a more militant direction.

Constance Markievicz

[Image description: A sepia tone photo of a white woman looking to her right. She is leaning against a stool and holds a revolver. She wears a wide brim hat with black feathers and flowers. She has short hair. She is wear a military button down short and suspenders.]

Sinn Fein was also breaking social conventions, even though Cumann na mBan was still an auxiliary unit, Sinn Fein would allow four ladies on the Sinn Fein Executive and would run two women in the 1918 election-Constance Markievicz and Winifred Carney, with Markievicz becoming the first women to win a seat in parliament. Many of its supporters and campaigners were also women. In fact, many men would complain in 1917 and later that the women were more radical than the men. Cumann na mBan fully embraced the 1916 Proclamation and even had Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington deliver a message to President Wilson in 1918, asking him to recognize the Irish Republic. Cumann na mBan took the front line in the anti-recruitment campaign and the police boycott and the anti-conscription movement. Like the Volunteers, Cumann na mBan believed they were a military unit, although they never got arms for themselves and worked closely with Volunteer units and Sinn Fein clubs.

Irish Volunteers and IRB

While Sinn Fein was slowly rebuilding itself, the Irish Volunteers were also being resurrected from the ashes. It started with local initiatives led by men like Ernest Blythe, Eoin O’Duffy, and Sean Treacy. Units popped up in local communities, organized and armed by their local leaders and eventually contacting GHQ which consisted of men like Collins, Mulcahy, and Brugha. While local units were rebuilding themselves, Collins was using the IRB to form a strict corps of officers, a growing source of personal power as well as military power that men like Brugha and De Valera (who were IRB during Easter Rising, but renounced their membership after the rising failed) distrusted.

GHQ issued an order saying that units should only listen to orders coming from their own executive (in order to prevent the order-counter-order disaster that doomed Easter Rising) and swore the Volunteers would only be ordered into the field if commanders were confident of victory. No forlorn battles. Mulcahy, as Chief of Staff, worked hard to instill a military spirit and discipline into the Volunteers while understanding that their most effective unit at the moment was the company and local initiative. (The companies would expand into battalions and brigades as the war progressed, but the fighting and tactics would remain local and territorial) So, while trying to act like a regular army and expecting the Volunteers to respect their officers and GHQ, he also had to allow for local improvisation as well as trust the local executives to have control over their soldiers. It was a difficult balancing act he would struggle to maintain during the entire Anglo-Irish War and into the Irish Civil War and the formation of the Free Irish State.

The Irish Volunteers convention on October 26th, 1917, elected DeValera as president, Brugha as the chairman of the executive with Collins as director of organization and Mulcahy as director of training, Liam Lynch as Director of Communications, Staines, Director of Supply and Treasurer, O’Connor director of engineering.

All of this work could have been for nothing if the British hadn’t handed the IRA the greatest gift in the world: the 1918 conscription crisis.

Lightning Rod Issues

Food Shortage 1917-1918

Before conscription was the food shortages in the winter of 1917-1918. The shortage was created because of food being exported to Britain, invoking memories of the terrible famine. Sinn Fein could not stop all of the food being exported, but they did what they could to protest this newest version of starvation. For example, a member of Sinn Fein, Diarmund Lynch took thirty pigs meant to for exportation, killed them, and shared the food with hard hit families, earning him deportation to America, but becoming a local folk hero and increasing Sinn Fein’s prestige.

There were also agrarian tensions because grazers (those who used farmland for their cows to graze instead of growing crops) were given preference to available land so the Congested Districts Board could maximize profits. While this makes sense, it added to the great unease in the land, especially as the food shortage grew more acute.

The IPP grew out of the Land Wars of 1880s and Sinn Fein, ever aware of Irish history, decided it would be no different. It joined in the fight for land, arguing that all the ranch land should be broken up evenly. All over the country, Sinn Fein created commission to break up the land and figure out the pricing as well as organizing mass occupation of available land, but ranchers refused to acknowledge the prices Sinn Fein proposed.

1917 Electoral Victory March

[Image description: A black and white photo of several men and women marching together through a park with several tall green trees and a cobblestone wall. Leading the crowd are three men in long coats and wide brim hats playing bagpipes. Everyone else is wearing long coats, suit coats, or dresses and hats.]

The Irish Volunteers officially stayed out of the new land war, claiming it wasn’t military or political in nature, but local groups sometimes participated. This combined with Sinn Fein’s own land seizures could lead to painful confrontations with police and other anger Irish men, so it was a difficult job balancing non-violent and not starting a mass uprising.

Another tool Sinn Fein used was boycotting. Said to original in Ireland during the Land Wars and used to great affect by Charles Parnell, Sinn Fein boycotted the RIC. This was a serious threat to the British system, decreasing the pool of candidates it could recruit from for the RIC and training the people to view the RIC as “others,” the first step to making a population comfort with violent action.

Boycotting the RIC was an old idea, something Sinn Fein and the Irish Volunteers wanted to implement it as soon as they were released from prison. This became a strong tool of the Volunteers to ostracize those who were betraying the rebel cause by working for the British as well as prepare the citizens for a war mentality.

Conscription crisis

No one yet knew that World War I would be over by November 11th, 1918. British thought she was facing long years of further bitter sacrifices and they needed new blood. They looked at Ireland and its large set of unruly young men itching for a fight and introduced the Military Service bill, extending forced conscription to Ireland-giving the Volunteers a shot in the arm while also uniting the Irish political parties, for the first time ever.

The Sinn Fein, IPP, and the Catholic Church pledged to resist Britain’s efforts to conscript Irishmen. DeValera prepared a statement, meant for Woodrow Wilson, insisting that their resistance was a battle for self-determination and principles of civil liberty, similar to the American’s cause during America’s revolution. The Volunteers planned local actions as well, using the conscription crisis as a springboard for intensive recruiting and introducing the idea of militant resistance into the greater Irish consciousness. The boycott of the RIC increased tenfold during the anti-conscription movement, shocking the police and trapping them in their barracks in locations such as North Tipperary. Women were particularly effective implementers of the boycott. Eventually the boycott was expanded to include those who helped or associated with the police. The boycott didn’t force many police to resign, but it built a belligerent and hateful mindset against the police-allowing for later violence.

Anti-conscription Rally in Ballaghaderreen County

[Image description: A blur black and white photo of a large gathering of people. They are surrounding a wooden platform where as group of men stand. Above the platform there is a white banner that says: No conscription Stand United]

The Irish Volunteers were not as engaged with the conscription crisis as Sinn Fein, because they still didn’t have a doctrinal strategy in place. Instead, volunteers were told to avoid getting arrested and if the RIC tried to arrest them, to resist. The Volunteers held daily drills and parades and prepared for battle, should the order ever arrive. However, GHQ seemed more concerned with getting rifles and ammunition than ordering a massive uprising. Conscription allowed them to demand that the local area their units controlled give up their guns to the Irish Volunteers. Some Volunteers even bought rifles off RIC or local British soldiers. Lack of guns would be a problem that plagued the IRA through their war with the British. Conscription also saw a spike in people joining the Irish Volunteers. GHQ tried to manage this wave of volunteers by issuing orders regarding how men should be recruits and how they should be vouched for and accepted.

The Irish Volunteers allowed their own soldiers to elect their officers (how could this go wrong?) GHQ seemed to try and curb who could be elected like requiring that they be member of the IRB, but given the haphazard nature these units were created, but it was only somewhat successful, some units merging the Volunteers and IRB men seamlessly, while other companies were dominated by non-IRB men or vice versa.

They threatened mass slaughter should Britain try to enforce conscription and, apparently, there was a plan for Cathal Brugha to lead a group of men to assassin the British cabinet (relying on Collins and Mulcahy-who was now chief of staff-to recruit for this venture).

German Plot

The British back down on conscription in mid-May while also arresting 73 nationalist leaders from May 17-18 under the Defense of the Realm Act, including Eamon DeValera, Constance Markievicz, Arthur Griffith, and William Cosgrave. They claimed there was a German plot i.e., Sinn Fein was working with Germany-like the 1916 rebels did and the 1798 rebels with the French.

It quickly became clear how flimsy the excuse was, that there was scant information, and undermined the government’s credibility in Ireland. It successfully knocked Sinn Fein off its feet for a moment, especially since all nine of the twenty-one members of Sinn Fein’s Standing Committee were arrested, but the British failed to arrest some of the most dangerous rebels such as Collins, Brugha, Mulcahy, and Harry Boland. But in the long run, it boosted Sinn Fein’s cause and destroyed any chance IPP had of reclaiming the national narrative. As Constance Markievicz claimed, "sending you to jail is like pulling out all the loud stops on all the speeches you ever made…our arrests carry so much further than speeches.”

1918 Election

Sinn Fein had won a total of five elections between 1917 and 1918 (De Valera, Count Plunkett, Cosgrave, Patrick MacCartan, and Griffith) and lost two elections. 1918 was their first general election. The election was held on December 14th, 1918, and is considered one of the most important moments in modern Ireland’s history. It was the first election after the end of the First World War and, because of the Representation of the People Act, women over the age of 30 and working-class men over the age of 21 could vote, tripling the Irish electorate from 700,000 in 1910 to 1.93 million in 1918.

The IPP won only 6 seats, the Unionists took 26 seats, and Sinn Fein won 73 seats.

The Sinn Fein victory can be explained in three different ways:

The new electoral: women and working-class men: people who had been hardest hit by the war and the rising and the conscription crisis, as well as the good shortage in 1917.Not only was Sinn Fein and Irish Volunteers campaigning, but Cumann na mBan campaigned hard as well, possible driving people into the arms of Sinn Fein since Sinn Fein stood for a republic which was against everything as it currently was. iSinn Fein’s rivals: the IPP and Labour had been broken by WWI and needed to rebuild themselves and their reputations if they wanted to compete.

The clergy was on Sinn Fein’s side because of conscription. DeValera also went a long way to argue that anti-conscription was not anti-soldiers nor were they ignoring the sacrifice of the Irishmen who had fought in the war so far. But the crime was that Britain sacrificed the best Ireland had for a colonial war.

Curated candidates. Sinn Fein ran those it was confident would win and in seats that would not weaken its own position or risk schism with the Labor movement. Also, there was some election rigging and voter intimidation.

Instead of sitting in parliament, the Sinn Fein candidates would sit in a new parliament: the first Dail of Eireann.

The Dail

The First Dail was formed on January 21st, 1919. It held its first meeting in the Round Room of the Mansion house of Dublin and created a Declaration of Independence and the Dail Constitution. Only 27 minsters appeared because 34 were in jail or on secret missions. Sinn Fein invited the IPP and Unionists to participate but they refused. The declaration of independence ratified the Proclamation of the Republic of Easter Rising and outlined a socialist platform, but it was more of a propaganda message because there was only so much the Dail could realistically achieve while battling England.

Members of the First Dail

[Image description: A black and white photo of three rows of men. The first row of men are sitting down on chairs, the second and third rows of men are standing. Most men are wearing black suits with white button down shirts and ties. Others are wearing tan or grey jackets. Some men had beards and mustaches, but most are clean shaven. Behind the men is a metal staircase and a white building.]

The constitution was a provisional document and created a ministry of the Dail Eireann. The ministry consisted of a President and five secretaries. First ministers of the Dail were:

Chairperson of the Dail: Cathal Brugha (because DeValera was in jail and Collins and Harry Boland were planning how to break him out)

Minister for Finance: Eoin MacNeill

Minister for Home Affairs: Michael Collins

Minister for Foreign Affairs: Count Plunkett

Minister for National Defense: Richard Mulcahy

The Dail expanded the number of ministers in April. It now included nine ministers within the cabinet and four outside the cabinet as well as a mechanism to create substitute presidents and ministers in the realistic event someone was arrested or killed.

This second ministry members were:

President: DeValera

Secretary for Home Affairs: Arthur Griffith

Secretary for Defense: Cathal Brugha

Secretary for Foreign Affairs: Count Plunkett

Secretary for Labour: Constance Markievicz

Secretary for Industries: Eoin MacNeill

Secretary for Finance: Michael Collins

Secretary for Local Government: W. T. CosgraveAustin Stacks would become minster after his release from jail and then took over as secretary for home affairs after Griffith became deputy president.

Once the Dail was convened, the Irish Volunteers saw themselves as an army of an Irish Republic hence why they named themselves the Irish Republican Army. They were formally renamed the IRA on August 20th, 1919, and took an oath of allegiance to the republic and to serve as a standing army.

On June 18th, 1919, the Dail officially established the Dail courts which were meant to replace the British judiciary. They eventually created several series of courts including a parish-based arbitration courts, district courts, and a supreme court which the people trusted more than the British courts. On June 19th, the Dail approved the First Dail Loan to raise funds they couldn’t raise via taxes. Collins would also create a bond scheme which helped keep the Dail and the IRA financially afloat.

England declared the Dail illegal in September 1919, but it was too little too late to undermine Ireland’s shadow government. DeValera left Ireland to fundraise in the United States, leaving Griffith as his Deputy President. The conduct of the Dail fell to its ministers while the conduct of the war fell to Collins, Mulcahy, Brugha, and the field commanders.

BRIEF Summary of Guerrilla Warfare in Ireland

The IRA would be broken into General Headquarters (GHQ) and local commanders. GHQ was run by Chief of Staff Richard Mulcahy who answered to Cathal Brugha, the Minister of Defense. Mulcahy also worked closely with Michael Collins, Minister of Finance and Intelligence and this amorphous command structure created a lot of tension amongst the three men. While Mulcahy tried to install discipline and standardization from GHQ, he was only partially successful as conditions on the ground often trumped whatever master plan GHQ had cooked up.

Richard Mulcahy

[Image description: A sepia toned photo of a thin white man with a prominent nose. He is wearing the military cap and uniform of the Irish National Army.]

It's estimated that the IRA had 15,000 members but only 3,000 were active at one time. The members were broken into three groups: unreliable, reliable, and active. Unreliable meant they were members in name only, reliable meant they played a supporting role, and active meant they were full-time fighters. It’s believed at least 1/5 of the active members were assistants and clerks. Skilled workers dominated the recruitment while farmers and agricultural workers were a minority. About 88% percent of the IRA members were under thirty and a majority of them were Catholics. The most active units were in Dublin County and Munster County which includes the cities of Clare, Cork, Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary, and Waterford.

The local units were supposed to be organized along the lines of a battalion but it was up to the local commanders, who were originally elected by their men. Initially, GHQ tried to assign two to three brigades to a county, but it would take a while before those brigades solidified. For the first year, the IRA could only muster small units, which actually worked in their favor.

Local commanders adopted the “flying columns” method of attack and GHQ eventually gave it their blessing. Flying columns consisted of a permanent roster of soldiers who worked together in small groups in coordinated attacks. The flying columns performed two kinds of attacks: auxiliary and independent

In an auxiliary attack, the flying column was assigned to a battalion as extra support for a large local operation already taking place. In an independent attack, the flying column itself would strike the enemy and retreat. This type of attack included harassing small military camps and police stations, pillaging enemy stories, interrupting communications, and eventually ambushes. The flying columns would become an elite and coveted unit but its soldiers were always on the run and relied on local support to survive.

Michael Collins

[Image description: A black and white photo of a white man shouting to a large crowd. He is standing outside on a platform, in the middle of a city street. He has short hair and is clean shaven. He is wearing a white shirt and a black suit.]

The IRA would go through two different reorganizations. The first occurred in March 1921. It broke up the brigade structure into small columns, built from experienced men. The brigade staff existed to provide supplier of arms, ammunition, and equipment while battalions provided the men for the columns. During the same reorganization, GHQ broke Ireland up into four different war zones to encourage activity in quieter areas.

In late 1921, the IRA was organized a second time. This time, GHQ created divisions. Division commanders were responsible for large swaths of territory, similar to the war zones created earlier that year. The purpose of the divisional commanders was to increase the likelihood of brigade and battalion coordination, make the IRA feel like it was growing into a real army, but still allowed (and encouraged) independent command, and transplant some of the administrative burden from GHQ to the divisional commanders. This was especially important if something were to happen to GHQ.

You can listen to season 1 to learn about specific battles. For the purpose of this recap, all you really need to know is that the IRA went from singular ambushes lead by ambitious local commanders to coordinated ambushes, assassinations (the most famous being Bloody Sunday carried out by Collins’ personal assassins), prison riots, hunger strikes, and outright assaults on barracks in the rural areas of Ireland. In addition to these military developments, the Dail supported the war effort by retaining the people’s support and maintaining the functionality of the Dail Courts and the Dail Loans.

The British responded by implementing martial law, launching large scale searches and arrests, curfews, roadblocks, and interment on suspicion and by creating the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries. The Black and Tans arrived in Ireland on March 25th, 1920. They were meant to reinforce the RIC and recruited mostly British veterans. They were called black and tans because of their uniform (dark green which appeared black and khaki. They weren’t special forces, just normal reinforcements which may explain why they were known for their brutality and violence. The auxiliaries were founded in July 1920s as a paramilitary unit of the RICs. It consisted of British officers and were meant to serve as a mobile strike and raiding force. 2,300 men served during the war and they were deployed in the southern and western regions of Ireland – where fighting was the heaviest. They were absolute brutes, known for arson and cruelty.

The British wanted to subdue Ireland by the May 1921 election, so they sent over fifty-one battalions of infantry, however, confusion over the military’s role, the RIC’s role, an inability to coordinate amongst the army, RIC, Black and Tans, and Auxiliaries, and the implementation of martial law hurt British efforts.

The IRA were feeling the pressure. In early 1921, they suffered some of their most drastic defeats contributing to poor morale and disgruntlement with the Dail and GHQ. GHQ was losing control over local forces while also trying to maintain a guerrilla war on a shoestring budget. To make matters worse, DeValera returned from America in December 1920 and spent most of 1921 trying to reorganize the IRA and Dail according to his vision. His arrival exasperated already existing tensions amongst several ministers, including Collins, Mulcahy, and Brugha, and threatened to tear the IRA apart from the inside.

Cathal Brugha

[Image description: A sepia toned photo of a small and thin man in a military uniform and a white button down and stripped tie. He has short hair and is clean shaven. Behind him is a blank white wall.]

Despite all of this, by May 1921, the IRA had reached its peak and the crown forces suffered record losses. From the beginning of 1921 to July, the IRA killed 94 British soldiers and 223 police officers. This was nearly double the totals from the last six months of 1920. This was also when the IRA launched their most ambitious attacks such as their attack on the Shell factory which amounted to 88,000 pounds in damage and their assault on the Dublin Custom House destroying the inland revenue, stamp office, and stationery office records. In addition to these attacks, the IRA increased the number and sophistication of their attacks in what is now Northern Ireland. However, these attacks could be self-defeating as they only enraged the Ulster Volunteers and left the Catholic population at the mercy of angry Unionists. These attacks would convince the British that Ireland was already partitioned (even if Sinn Fein and the IRA refused to acknowledge the fact) and it was in their interest to protect Northern Ireland from IRA incursions. This meant another army and more money that could have been spent elsewhere.

It was clear that neither side could win this conflict through military efforts alone.

References:

The Republic: The Fight for Irish Independence by Charles Townshend, 2014, Penguin Group

Fatal Path: British Government and Irish Revolution 1910-1922by Ronan Fanning, 2013, Faber & Faber

Richard Mulcahy: From the Politics of War to the Politics of Peace, 1913-1924 by Padraig O Caoimh, 2018, Irish Academic Press

A Nation and Not a Rabble: the Irish Revolution 1913-1923by Diarmaid Ferriter, 2015, Profile Books

Eamon DeValera by Ronan Fanning, 2016, Harvard University Press

#Irish War of Independence#Irish History#Michael Collins#Richard Mulcahy#Irish Republican Army#IRA#Eamon Devalera#Cathal Brugha#Constance Markievcz#easter rising#history blog#queer historian#podcast episode#Spotify

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

any time someone asks me my research area I have an identity crisis

#i just like too many things#historian#history#theater history#irish history#public history#grad student#grad school#graduate student#graduate school

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The wording of the St Albans chronicles – ‘he [Richard II] also took with him boys of noble birth, the sons of the dukes of Gloucester and Hereford, whose relatives he especially feared’ – has been taken to suggest that Richard deliberately took to Ireland both Henry and Humphrey, son of the late duke of Gloucester (then aged about seventeen), as hostages for the good behaviour of their relatives. If true, the tactic did not work! These chronicle accounts were undoubtedly written with pro-Lancastrian hindsight. It was very common for noble boys to be taken on campaign, even if they were not old enough to indent in person or to bring their own retinue.

There had been plans to take Richard on campaign in 1377, at the age of ten. Opportunities to be blooded in actual warfare were few and far between. It would be extremely unlikely that the campaign to Ireland would not be used for this purpose for Henry and for other young men around his age. It does not require Richard to have a penchant for the prepubescent, or to have taken Henry with him deliberately as a way of keeping his father in check. Richard did not think that he needed to keep Bolingbroke in check, but assumed that the exile would continue for the prescribed time. Richard’s knighting of Henry, as described by Creton, can be interpreted as an act of honour towards the Lancastrian line, the invocation of the military reputation of his forebears, irrespective of current issues with Bolingbroke. If the account is to be believed, it took place just before an anticipated engagement with the Irish rebels, exactly the setting we would expect, and was accompanied by other dubbings of young men, including, it seems, Alan Buxhill, then aged eighteen.

Even according to the pro-Lancastrian sources, it was not until Richard had heard the news of Bolingbroke’s invasion and had decided to return to England that he imprisoned Henry as well as the son of Gloucester in Trim castle. Here Henry seems to have remained, thirty miles to the north-west of Dublin. The date of his return to England is uncertain. According to Adam Usk, ‘the duke sent to Ireland for his eldest son Henry and for Humphrey the son of the duke of Gloucester who had been imprisoned by King Richard in Trim castle; and they were sent back to him together with a large collection of the king’s treasure’. This passage comes immediately after the chronicler’s account of Bolingbroke’s presence in Chester (9–20 August) and his move to London with the captive king (with an estimated arrival date of 1 September), and is preceded by the linking phrase ‘in the meantime’. This wording suggests, therefore, that arrangements to bring the young Henry back were initiated before Bolingbroke left Chester. Usk adds that Henry came back safely, ‘bringing with him in shackles Sir William Bagot’, but that Humphrey, son of the duke of Gloucester, died in Anglesey on the way back, having being poisoned in Ireland by Lord Despenser. The alleged location of Humphrey’s death suggests that the boys were to be brought back via Chester. This is also implied in a warrant for issue of 5 March 1401 in favour of Henry Dryhurst of ‘West Chester’. Here Dryhurst was recompensed for the cost of wine which he had provided to Bolingbroke’s household whilst in Chester. It also paid Dryhurst 20 marks for the freightage of a ship from Chester to Dublin, and ‘for sailing from the same place and back again to conduct the Lord the Prince, the King’s son, from Ireland to England, together with the furniture of a chapel and its ornaments which formerly belonged to the late King Richard the Second, deceased’.

Anne Curry, "The Making of a Prince: The Finances of ‘the young lord Henry’, 1386–1400", Henry V: New Perspectives ed. Gwilym Dodd (York Medieval Press 2018)

#henry v#richard ii#humphrey of pleshley#the deposition of richard ii#henry v and his spiritual father#historian: anne curry#richard ii's irish campaigns

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

terrifying moment when i went to present my Irish history research this weekend and the guy chairing my panel whose name was Caoimhin shook my hand and spoke to me in a full Irish accent. like oh i hope none of this is surface level analysis bullshit

#he nominated my paper tho apparently! just learned from my prof#him and the other Irish historian. who was an American but also chairing my panel#the panel was not even on Irish history it was Queer History broadly

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

somewhat related to prev post but my white irish side are all men of orange protestants but in the weird way where they don't identify with scottishness at all and are only protestants because they were the church that took them in. my grandpa is very much a "proud irishman" and doesn't care about scotland at all, and i think that's bc he's from donegal rather than the other northern provinces (donegal is in the republic but it was historically part of the plantation of ulster) and he has native irish ancestry and also his first language wasn't english it was irish gaelic, which is the case for many in c. donegal where he was born and raised. that doesn't mean his politics aren't shit, they're terrible, but thankfully he's not as rabid an orangeman as you get in the north (or in the canadian prairies lol) but it's still so depressing. the indoctrination into the ideology is insane btw

#heard something recently where a historian was joking about how a united ireland would subject the rest of ireland#to the orangemen en masse and that the southern irish dont deserve that#so true fr#im very much pro-republic and support a united ireland and the preservation of gaeilge etc etc dont get it twisted

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1962 – Margaret Emmeline Conway Dobbs, Irish historian, language activist, and defender of Roger Casement, dies.

Margaret Dobbs was born in Dublin but spent much of her life in the Cushendall, Co Antrim. Along with Roger Casement and Francis Biggar she was one of the organisers of the Feis in Glenarrif in 1904, and was active on the Feis Committee until the end of her life. She was an Irish scholar and felt that ‘Ireland without Irish is quite meaningless’. She wrote plays, among which is She’s Going to…

View On WordPress

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me, a First Nations woman, already bracing myself for all the mean-spirited takes on the Queen’s passing and the amount of people who will expect me to agree with them just because I’m native.

#And the other half of me is Irish so people REALLY do me thinking I go around hating the monarchy.#Joke’s on you I’m a historian and the only royal I have a real opinion on is Ms M over there.#(The opinion is not favourable.)#text#chey.txt

1 note

·

View note

Text

Irish Soldiers: the Battle on Mons during the Great War of 1914 to 1918.

The Battle of Mons was the first major action of the British Expeditionary Force of the First World War. It was a subsidiary action of the Battle of the Frontiers, during which the allies fought the Germans on the French border.

I don’t know the source of this short film documentary and consequently I am unable to credit the film maker.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

We’re so used to the sexual reading of the entire book of Dracula, which takes the sensuality of the early chapters and jams everything that follows it into the same metaphor no matter how poorly it fits, but I feel the segment we’re approaching works much better with a lens of chronic illness and disease.

Vampire legends are inextricably intertwined with disease. Many of them are said to have been birthed by burying victims of disease too soon, who later seem to rise from the dead. But what’s more is that Stoker and his family have deep-seated trauma over disease: his mother had to flee her hometown at the age of 14 because of a horrific cholera epidemic, and Stoker himself was bedridden as a child from an illness that no one could identify.

Found this quote from Irish Historian Mary McGarry:

Bram as an adult asked his mother to write down her memories of the epidemic for him, and he supplemented this using his own historic research of Sligo’s epidemic. Scratching beneath the surface (of this essay), I found parallels with Dracula. [For instance,] Charlotte says cholera enters port towns having traveled by ship, and can travel overland as a mist—just like Dracula, who infects people with his unknown contagion.

I bring this up because a lot of academic analysis insists that Lucy sleepwalking is proof of her being the Slutty Woman archetype that needs to be punished. This suggested symbolism is hilarious when put next to the text saying she inherited it from her father, but I’d like to suggest a different angle from the lens of disease suggested earlier:

Lucy’s sleepwalking is a condition that predates Dracula but makes her an easy target for him to prey on. Through the lens of disease symbolism, she now is someone with chronic illness or disability who is especially vulnerable to infectious disease. This becomes a cross-section of Stoker’s trauma regarding disease: his own mystery illness and his mother fleeing a plague.

To wind down my rambles with a bit of a soapbox, I feel this adds a very poignant layer to the struggle to keep Lucy alive. The COVID pandemic showed a horrifying level of casual ableism vs disabled and immunodeficient individuals, shrugging off their vulnerability and even their deaths with “well COVID only kills them.” There’s something deeply gratifying at seeing the way everyone around Lucy fights to the bitter end to protect her and refuses to just give her up to Dracula, whether it’s Mina physically chasing him away or the suitor squad pouring their blood into her veins or Van Helsing desperately searching for cures. The vulnerable deserve no less than this. They’re not acceptable casualties.

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

some quick resources with vital information and context about or related to Palestine (compiled Oct. 15)

[Video] Why Israel Deliberately Targets Civilians

[Thread] Zachary Foster, a Ph.d historian of Palestine, posted about the real history of Hamas

[Video] Double Down News covering the myth of "self defense"

[Video] Mohammed El-Kurd on 75 years of violence and oppression

[Thread] Abby Martin debunks the "human shield" excuse used by Israel to bomb civilians

[Video] Mohammed El-Kurd on media literacy, "DO NOT BE COMPLICIT IN GENOCIDE"

[Article] "Israel’s genocidal assault on Gaza is quite explicit, open, and unashamed." - Raz Segal, associate professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Stockton University, in @JewishCurrents.

[Video] Mohammed El-Kurd on ABCNews

[Tweet] Reminder that just a few months ago Netanyahu brought a map to the UN of the “New Middle East” that effectively showed Israel annexing all of Palestine.

[Video] Michael Brooks breaking down how the situation with Palestine and Israel is "not complex"

[Video] Paul Murphy, Irish Parliment Member for People Before Profit, on Israel and Gaza

[Statistics] The Human Cost of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

[Video] Husam Zomlot: “It’s the Palestinians that are always expected to condemn themselves.”

[Map] An interactive map that details the history of "Conquer and divide", from 1967 onwards, via B'Tselem.

[Documentary] The Actions of Settlers in Hebron (Tel Rumeida)

[Video] Former CIA admit to lying about atrocities committed by Cubans. They admit they didn't know of a single atrocity done by the Cubans. "It was pure raw false propaganda to create an illusion of communists eating babies for breakfast."

[Documentary] Gaza Fights For Freedom (covers the IDF assassinating and maiming Palestinians in the peaceful March for Return in 2019)

[Video] Ghassan Kanafani’s famous interview

[Documentary] How Palestinians were expelled from their homes

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

What A Civil War Is And Is Not

The idea for this particular episode was inspired by what’s going on over here in the United States. As I’m sure everyone knows, we had a coup attempt in January and there was a lot of talk of a new civil war and a lot of the traitorous morons who took part in the Jan 6th insurrection claimed they’re looking forward to a civil war and all that crap. And it got me thinking that even though we’re talking about the next civil war, we’re not actually talking about civil wars. What does a civil war mean? What do modern civil wars look like? Etc.

I will warn my listeners that I was an international relations major before I was a historian, so we will be discussing political theory during this blog post, but I’ll try to keep it to brief. I want to quickly define what a civil war is, discuss why they happen and why they’re so violent, and then highlight unique characteristics of a civil war.

What We Mean When We Talk About Civil Wars?

First, what are we talking about when we talk about civil wars?

Like most terms in political science, there are several ways to define a civil war. James Fearon in his article Iraq’s Civil War said a civil war was “a violent conflict within a country fought by organized groups that aim to take power at the center or in a region, or to change government policies.” Stathis N Kalyvas in his book The Logic of Violence in Civil War further refines this definition as “an armed conflict within the boundaries of a recognized sovereign entity between parties subject to a common authority at the outset of the hostilities.” Some scholars such as Ann Hironaka in her book Neverending Wars: The International Community, Weak States, and the Perpetuation of Civil War, add that at least one actor in the war must be the state. Jeremy M. Weinstein complicates the definition further by cataloguing civil wars based on, to paraphrase, whether the actors involved in the war want to capture the center, are fighting over secession, or violence is used but the belligerents have no interest in achieving territorial control of any sort. Other scholars have tried to add a numerical definition i.e., it’s not a civil war less than 1,000 people have died in the conflict and less than 100 people died on average per each year of the conflict.

For the purpose of this episode, we can understand a civil war as an internal conflict in which various actors (one of whom has to be a stand in for the state) shared a common authority and are now in armed conflict over a question of political control. An even simpler, but less academic, definition of a civil war is when the state, society, or portions of society attempts to kill itself in hopes of a new political outcome. When a state responds to a civil threat, it’s attacking its own people, targeting its own territory, and harming its own ability to function economically, politically, and socially. When a non-state actor responds to a civil war, whether they be insurgencies, rebels, whatever we want to call them, they are attacking their own communities, challenging their own government, and coercing or enlisting the help of their own families, friends, or neighbors. It is a war upon the self; however, you want to define the self, and in some cases, can be understood as state or social suicide.

Why do they happen?

Given the extremity of a civil war, why do they happen at all? There are a several theories, but the two most famous are the greed theory, the grievance theory, and the opportunity theory.

The greed theory championed by Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler in their paper Greed and Grievance in Civil War basically argues that civil wars are caused by a combatant’s desire for self-enrichment and believe that war is the best way to gain control over goods and resources or increase one’s power within a given boundary. They argued that natural resources can contribute to the likelihood of conflict since natural resources, such as oil, can lower the startup costs of war or provide rebels with easy means to extend the war.

Confederate Soldiers Captured at Gettysburg

[Image Description: A black and white photo of three confederate soldiers resting against multiple, misshapen logs. They are all wearing slouch hats and great, mismatched uniforms along with rolled up blankets. behind them is the clear sky and the hills of Gettysburg]

The grievance theory argues that civil wars are caused by combatant’s sense of grievance against the state or the “other”. Opponents of the greed theory, such a David Keen, argue that greed and grievance are more intertwined than Collier and Hoeffler argue and that they can feed into one another. So really, we should think of it as the greed-grievance theory, where grievance can create opportunities for conflict which creates opportunities to enrich oneself which creates other grievances and so on. In his paper Incentives and disincentives for violence, Keen uses the conflict in Serbia to illustrate how the two feed into each other. Milosevic in Serbia used the media to create grievance amongst the Serbian population and create a common enemy. The elites around Milosevic encourage conditions that warranted international sanctions so they could create a black market where they controlled trade and could loot resources. Milosevic realized that if he ended the conflict, the sanctions would be taken away, and his black-market income would disintegrate. Thus, the stirring of grievances created an opportunity for elite enrichment that proved too precious to end.

The opportunity theory, championed by James Fearon and David Laitin, argues that civil wars likely if there are factors that make it easy for rebels to recruit soldiers and sustain insurgencies. They include poverty, political instability, rough terrain, and large populations as some factors that can increase the likelihood of civil war. Basically, if a state favors an insurgency there’s going to be a civil war.

I tend to agree with Keen that the greed model is too simplistic and even the greed-grievance model is narrow. Like Keen, I think they have to be incorporated into a theory that takes into account several other aspects of conflict generation such as some of the factors Fearon and Laitin identified as well as the perception of state control. All three theories seem to rely on this concept that if the combatants can benefit (whether that be economically, militarily, or politically) then they will risk civil war, but how can a non-state actor benefit if the state itself isn’t perceived as weak in some way? So, there must be a sense of state weakness combined with a sense of something not being gained or given on the part the belligerent actors, a something that was promised (whether as a normal function of the state or through an accepted social/state bias) that can only be gained through armed conflict.

Characteristics of a civil war

Now that we’ve gotten the theory out of the way, I want to spend the rest of the episode talking about common characteristics of civil wars.

Who are the combatants?

When talking about a civil war, the first tell-tale sign that it’s a civil war, are the combatants. Sometimes it can be easy to discern the combatants from each other like in the Irish Civil War, where it was the Free Irish State vs the anti-treaty IRA or the American Civil War where it was the Union versus the Confederates.

Sometimes it gets really complicated like during the Russian Civil War because, not only is it really a bunch of smaller civil wars rolled up into one, but because there isn’t a single point of state authority. You have the Red state versus the White state versus various separatist movements and insurgencies. That’s why I like Jonathan Smele’s book the “Russian” Civil Wars because in reality the only reason we call the civil war a Russian civil war is because all the peoples involved were once part of the Tsarist Empire.

Red Army in Moscow, 1918

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a crowd gathered together in a city square. Two members of the crowd are holding up a banner with Russian writing. They are standing on a brick road. Behind them are several stone buildings.]

If we look at Central Asia, we have Red and White forces battling each other, but we also have fragile semi-states who are also fighting each other whether it be the Tashkent Soviet, the Kokand Autonomy, or the Alash Autonomy or the two remaining emirates: Khiva and Bukhara, plus the Basmachi, a guerrilla movement that wanted to preserve what they deemed to be a proper Islamic society. Then to make matters even more confusing, once the Reds defeated the Whites, they rely on the local state actors to restore order, and with their help overthrow the emirs, but eventually turned on those same state actors, wiping out all they deemed as dangerous and replaced them with state actors of their own choosing. This cannibalization isn’t unusual to see in civil wars and more times than not it occurs amongst the non-state actors. For example, during the Tajik Civil War of 1994, after the Kulob militia were elected to power they turned on an array of rebel groups including the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan and the Pamirs from Gorno-Badakhshan, which then turned into a nasty bit of ethnic cleansing-which is also common in civil wars.

Identifying combatants can also be complicated because of external interference. We’ll get into this a little later in the episode, but a perfect example of this is the current Syrian Civil War: where Asad’s government is fighting against the various Syrian rebel groups, but the Syrian rebel groups also have to content with Hezbollah, Iranian forces, Russian Forces, and the Islamic State.

Type of Warfare

The type of warfare most commonly seen with civil wars is guerilla warfare or insurgent warfare. Basically, small groups of combatants use tactics such as ambushes, sabotages, raids, hit and run tactics, and petty warfare to attack conventional, less mobile forces. So, Nathaniel Bedford Forrest’s raids during the American Civil War or the Basmachi attacks during the Central Asian Civil Wars.

Often times the insurgents avoid standing battles because they will never win those battles. Instead, they use the terrain to launch hit and run attacks, ambushes, and raids, relying on their small, but highly mobile units to wear the conventional army down.

Negotiations between Soviet soldiers and the Basmachi

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a crowd of men sitting and standing around two long tables placed together. Some of the men wear turbans and skullcaps and long robes and long dress shirts while others are wearing the grey shirts and caps of the Bolsheviks. Two clothes are spread across the two tables with several plates of food. The men are sitting in a courtyard with a tree providing shade.]

They’ll also target governmental and military officials as well infrastructure such as supply lines, important governmental or symbolic buildings, and centers of commerce-meaning civilians are also targets. The Provisional IRA turned this into an art as they planted car bombs in large shopping areas. We’ll get into the tricky relationship between insurgents and the population a little later in the blog post, but it should be clear that both the state and the non-state combatants will target civilians when it suits their purposes.

Governments respond by using standard counter-insurgency tactics such as population control i.e., draining the swamp. Expanding zones of control, also known as oil spots, cordon and search operations, winning the hearts and minds of the people, scorch earth tactics, and intelligence operation which includes intelligence gathering, counterintelligence efforts, and assassinations. The Government can also call-in conventional units and tactics such as heavy bombardments, air power, and special forces. Basically, the government doesn’t care how it wins as long as it wins, so it will simultaneously implement conventional tactics and counter-insurgency tactics-sometimes to its own detriment. A good example of this might be the Soviet-Afghan War or the Vietnam War, although those are perfect examples of how extreme external meddling can drastically change the course and duration of your civil war.

I also want to acknowledge that in modern civil wars like in the current Syrian or Yemen Civil wars, governments are growing less and less concern about civilian casualties. While civilian loss is a staple of civil wars, in Syria we’ve seen Assad deploy chemical weapons, which are banned by international law and he has purposely targeted medics and medical infrastructures. Or the purposeful starvation of Yemeni people in their civil war. The accepted “standards” of law are being increasingly abandoned and states are using civil wars to do whatever the hell they want to civilians and rebels with the goal of terrorizing their own people as much as defeating the rebels. This has sort of always been an aspect of civil war, but I would argue that the concept that you need to defeat your own people-even the civilians who are not active-is a new 21st century twist.

Atrocities and violence

Which of course leads us to atrocities. Civil Wars are known for their atrocities and there are hundreds of papers and books studying why civil wars are so violent and bitter and is the violence random or does it follow a pattern, etc. Atrocities always occur in war, but during a conventional war, you’re hurting people who have nothing to do with you. It’s an other, an alien, someone from another country and culture, etc. But with a civil war, no matter how “othered” the enemy becomes, it’s still a neighbor or a family member and so there is this question: why do people get so violent during civil wars? And the disquieting answer is that: the monopoly of power is broken during a civil war. So, in a stable government whether you’re a democracy or a dictatorship, there’s an understanding between government and people: do these things or be these things and the chances of state violence against you will be low.

Now I’ll acknowledge that there is randomized terror, such as the Soviets perfected or any modern-day dictator, but even dictators, or the ones who want to survive, know that there is a balance between being a crazy maniac that people will risk everything to overthrow and the right amount of violence to maintain absolute control. As long as this agreement holds, the state has monopoly over violence. But something happens where this monopoly ends-or it’s perceived to end-and other non-state actors now have the ability to employ violence to maintain control of their areas. And so, violence becomes the new political, economic, or social currency. Kalyvas, in his book the Logic of Violence in Civil War argues that civil war violence isn’t random, it only occurs in disputed territories (where the monopoly of violence is most tenuous) and is driven, not by the conflict itself, but by old rivals and wounds in the population.