#Louisiana Voodoo

Text

So you want to learn about Louisiana Voodoo…

door in New Orleans by Jean-Marcel St. Jacques

For better or worse (almost always downright wrong) Louisiana Voodoo and Hoodoo are likely to come up in any depiction of the state of Louisiana. I’ve created a list of works on contemporary and historical Voodoo/Hoodoo for anyone who’d like to learn more about what this tradition is and is not (hint: it developed separately from Haitian Vodou which is its own thing) or would like to depict it in a non-stereotypical way. I’ve listed them in chronological order. Please keep a few things in mind. Almost all sources presented unfortunately have their biases. As ethnographies Hurston’s work no longer represent best practices in Anthropology and has been suspected of embellishment and sensationalism on this topic. Additionally the portrayal is of the religion as it was nearly 100 years ago- all traditions change over time. Likewise Teish is extremely valuable for providing an inside view into the practice but certain views, as on Ancient Egypt, may be offensive now. I have chosen to include the non-academic works by Alvarado and Filan for the research on historical Voodoo they did with regards to the Federal Writer’s Project that is not readily accessible, HOWEVER, this is NOT a guide to teach you to practice this closed tradition, and again some of the opinions are suspect- DO NOT use sage, which is part of Native practice and destroys local environments. I do not support every view expressed but think even when wrong these sources present something to be learned about the way we treat culture

*Start with Osbey, the shortest of the works. To compare Louisiana Voodoo with other traditions see the chapter on Haitian Vodou in Creole Religions of the Caribbean by Olmos and Paravinsi-Gebert. Additionally many songs and chants were originally in Louisiana Creole (different from the Louisiana French dialect), which is now severely endangered. You can study the language in Ti Liv Kreyol by Guillery-Chatman et. Al.

Le Petit Albert by Albertus Parvus Lucius (1706) grimoire widely circulated in France in the 18th century, brought to the colony & significantly impacted Hoodoo

Mules and Men by Zora Neale Hurston (1935)

Spirit World-Photographs & Journal: Pattern in the Expressive Folk Culture of Afro-American New Orleans by Michael P. Smith (1984)

Jambalaya: The Natural Woman's Book of Personal Charms and Practical Rituals by Luisah Teish (1985)

Eve’s Bayou (1997), film

Spiritual Merchants: Religion, Magic, and Commerce by Carolyn Morrow Long (2001)

A New Orleans Voodoo Priestess: The Legend and Reality of Marie Laveau by Carolyn Morrow Long (2006)

“Yoruba Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo” by Ina J. Fandrich (2007)

The New Orleans Voodoo Handbook by Kenaz Filan (2011)

“Why We Can’t Talk To You About Voodoo” by Brenda Marie Osbey (2011)

Mojo Workin': The Old African American Hoodoo System by Katrina Hazzard-Donald (2013)

The Tomb of Marie Laveau In St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 by Carolyn Morrow Long (2016)

Lemonade, visual album by Beyonce (2016)

How to Make Lemonade, book by Beyonce (2016)

“Work the Root: Black Feminism, Hoodoo Love Rituals, and Practices of Freedom” by Lyndsey Stewart (2017)

The Lemonade Reader edited by Kinitra D. Brooks and Kameelah L. Martin (2019)

The Magic of Marie Laveau by Denise Alvarado (2020)

In Our Mother’s Gardens (2021), documentary on Netflix, around 1 hour mark traditional offering to the ancestors by Dr. Zauditu-Selassie

“Playing the Bamboula” rhythm for honoring ancestors associated with historical Voodoo

Voodoo and Power: The Politics of Religion in New Orleans 1880-1940 by Kodi A. Roberts (2023)

The Marie Laveau Grimoire by Denise Alvarado (2024)

Voodoo: An African American Religion by Jeffrey E. Anderson (2024)

#I’ll continue to update as I find more sources#Please be respectful of other people’s religion#Louisiana Voodoo#Louisiana Hoodoo#In the case of authors behind a paywall or whom you do not wish to support I highly recommend your local library#I do not support every view but think even when wrong they present something to be learned about the way we treat culture#Voodoo#Hoodoo#conjure#rootwork#Books

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

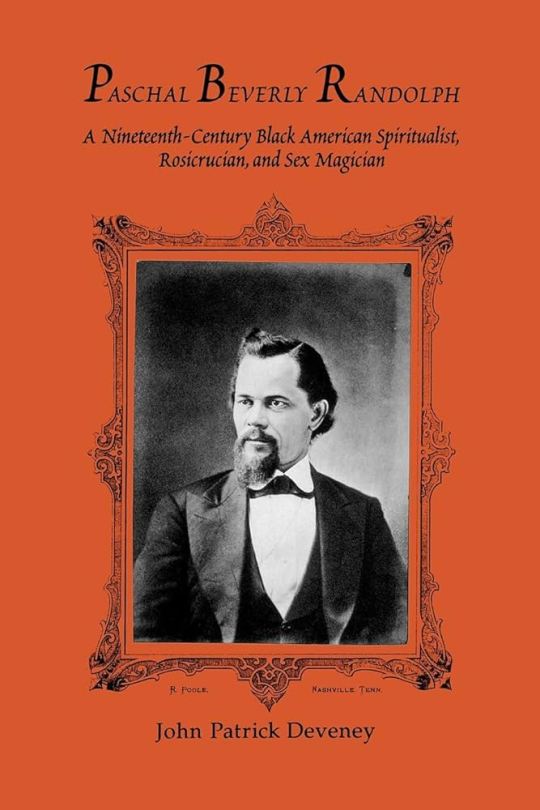

During the era of slavery, occultist Paschal Beverly Randolph began studying the occult and traveled and learned spiritual practices in Africa and Europe. Randolph was a mixed race free African man who wrote several books on the occult. In addition, Randolph was an abolitionist and spoke out against the practice of slavery in the South.

After the American Civil War, Randolph educated freedmen in schools for former slaves called Freedmen's Bureau Schools in New Orleans, Louisiana, where he studied Louisiana Voodoo and hoodoo in African American communities, documenting his findings in his book, Seership, The Magnetic Mirror. In 1874, Randolph organized a spiritual organization called Brotherhood of Eulis in Tennessee.

Through his travels, Randolph documented the continued African traditions in Hoodoo practiced by African Americans in the South. Randolph documented two African American men of Kongo origin that used Kongo conjure practices against each other. The two conjure men came from a slave ship that docked in Mobile Bay in 1860 or 1861.

#kongo#african american#mobile bay#randolph#paschal beverly randolph#sex magick#seership#magnetic mirror#tennessee#american civil war#louisiana voodoo#hoodoo#rootwork#conjure#ancestor veneration#witchblr#pagans of tumblr#afrakans#brownskin#africans#kemetic dreams#afrakan#african#brown skin#african culture#afrakan spirituality#africa#europe

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Representation of Haitian Voodoo in comics. Integrating its rich mythology and its deities.

Art by: vodou.renaissance

#witches#witchcraft#witch#baby witch#witch community#witches of tumblr#pop magick#pop culture magic#louisiana hoodoo#hoodoo witch#new orleans hoodoo#hoodoo#creole voodoo#new orleans voodoo#louisiana voodoo#voodoo#folk magic#folklore#african folk magick#pop culture witchcraft#pop culture witch#pop culture magick#pop culture#comic#comics#comic art

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Words To Live By

#conjuring#spiritual#like and/or reblog!#rootwork#voodoo#louisiana voodoo#Vodou quote#Quote of the day#Spiritual quote#follow my blog#southern magic#Magic quote

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

My adorable femboy oc Dizzy with his pet gator and rooster

#cajun#colored pencil#markers#louisiana voodoo#voodoo#femboy oc#femboii#rooster#alligator#louisiana#bristol paper

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some of my new voodoo dolls you can find at

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Orleans National Vodou Day: 2025

NONVD

https://www.vodouday.org/

#RespectTheVoodoo #LOVEmyNewOrleans

#OurSacredStories

@DivinePrinceTyEmmecca

@OurSacredStories

@LilithDorsey

#Benin #VodouDay #Ouidah

@nationalvodouday #NONVD #NONVDNOLA #NewOrleansNationalVodouDay #NationalVodouDay

#Haiti

⚜New Orleans, Louisiana, USA 🇺🇸✊🏿🇧🇯✊🏿🇭🇹

#NewOrleans #Louisiana

#lovemyneworleans#ancestorsseeall#hoodoo#spiritual court#damballah#haitian vodou#West African Vodou#Louisiana Voodoo#Conjure#orishas#ritualwork#ceremony#tourism#benin#Congo Square#New Orleans#Marie Laveau

1 note

·

View note

Text

Voodoo- Hamidou Banor by Baldovino Barani for FACTORY Fanzine XXXVI

#rufskin#sling#pose#sage#hamidou banor#hamidiu banor#baldovino barani#voodoo#vaudou#voodoo priest#factory fanzine#french quarter#louisiana#new orleans#beauty#muscle#magik#baron samedi

897 notes

·

View notes

Text

Angel : *enters the lounge fuming mad**throws a small doll dressed like Valentino at Alastor* I know you only deal in souls, but I fucking swear if you kill Valentino I'll give you whatever your twisted little heart wants, I can't deal with him anymore --

Alastor: *sneers at the Valentino doll, before flicking it off him with a claw* I don't //do// poppet magic, especially not for sinners who have nothing to offer me. Have you considered praying to St. Michael about it?

Angel : Well thanks for fucking nothing then, for fucks sake, who do I gotta blow to get a break in this... *processing that Alastor just told him to pray not just to a saint, but the correct saint in this situation, which can only mean...*... town. WAIT, you're fucking CATHOLIC!?!

Alastor : *slow blink* ... A lapsed one, obviously.

#Alastor grew up in a Louisiana that was majority Catholic#During Alastor's childhood one could theoretically be both a devout Catholic and a Voodoo practitioner#And “Voodoo” dolls have absolutely nothing to do with Voodoo#Trying to be funny AND educational here#hazbin hotel#alastor#hazbin alastor#alastor hazbin hotel#angel dust#hazbin angel dust

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

Francine Prose - Marie Laveau - Berkley - 1978

#witches#creoles#occult#vintage#marie laveau#berkley books#francine prose#voodoo#new orleans#nouvelle orleans#louisiana#1978

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 1-Black Penny

Summary: You grew up in the hustle and bustle of a city most of your life, so you packed your few belongings and headed straight to New Orleans. You hoped to live a simpler, quieter life on the Historic French Quarter. By day during the week, you helped manage Marie Laveau’s House of Voodoo Shop and by nightfall you tended bar at Black Penny on the weekends.

You were aware mutants existed, and believed them to be just as ordinary as you but only with extraordinary abilities. After living a few years in NOLA, you had a knack of picking them out in a crowd and treated them no differently than you’d treat anyone else. You had many run in’s with mutants on Bourbon Street, but none as impactful as the day you ran into Remy LeBeau.

A/N: Character Intro, She/Her Pronouns, GambitX!FemaleReader, GambitX!NonMutant, RemyLeBeauX!FemaleReader, Mutants, Post Deadpool and Wolverine, Post Void, New Orleans, Alcohol, Pining, Creole/French to English Translation

(c) - Creole

(f)- French

*I just want to disclose I am not a comic expert. Gambit/Remy LeBeau is very new to me and I’m doing my best to stay genuine to what I’ve researched online or from what I’ve seen in the D&W movie. I’m aware there was a HUGE controversy over his heavy accent/dialect and over his eye color in the movie, so I tried to incorporate both versions of each in my stories to satisfy everyone’s preferred Gambit/Remy style. (Personally, I loved Channing Tatum’s accent in the movie ☺️) I’m also cognizant that Gambit and Rogue are an item in the comics, but for sanity sake, Rogue will be a pastime only mentioned in passing if absolutely necessary so I don’t have to study in depth another character I’m unfamiliar with. (I need some brain space for real life stuff, too 😅) Anyway, I’m doing my maximum effort over here writing for Gambit/Remy, so when I do post my developing Gambit story, please, if you have comments or criticisms that don’t benefit anyone else’s appreciation of these fanfics, keep them to yourself and let the rest of us enjoy it. Thanks so much*

♠️♥️♣️♦️

It was a particularly busy night at Black Penny. As live bounce music and jazz blared from the stage, patrons dance and socialize carelessly with each other while you hotfoot from one end of the bar to the other serving up shots and beers.

You approach a man waiting patiently, his face downward hovering over a stack of playing cards.

“What can I getchya?” You ask him.

He began twirling an ace of spades between his fingers.

“(c) Kisa mwen ka jwenn pou ou?” You repeat.

The man lifted his gaze to meet yours with a mischievous grin stretching across his face. An eerie magenta glow softly radiated from his irises causing your jaw to drop. Your stunned reaction spurred him, causing his smile to widen and his eyes to glow brighter as the whites of his eyes began to blacken.

“….woah.” You say under your breath.

The man chuckled, “(c) Ou dwe padone Gambit, cheri (You must pardon Gambit). When his eyes see somethin’ so (f)dulcet (beautiful), it be hard to hide it.”

You shook your head to refocus, “No need to apologize. This is a safe space for everyone. Just caught me off guard is all.”

You flash him a smile and a wink as he returned one to you, the whites of his eyes returning to ‘human’ version of normal and his irises became a shade of icy green.

“Nobody be lookin’ at me like dat wit’out runnin’ off. You weren’t scared?”

“Of course not. Takes a lot more than a pair of flashy eyes on a handsome face to scare me away.” You state.

He laughed as he adjusted in his seat.

“Dats good, dats good.” He said as he leaned forward on the surface of the bar.

“What are you drinking, Gambit?” You ask again.

“Sazerac. (c) Mèsi, cheri. (Thank you, darling).”

You bring the gentleman a rocks glass fixed neat with the amber-red reserve bourbon. He gingerly raised the glass to his nose, inhaling the oak wood barrel scent with hints of cherry, caramel, apples, and tobacco.

He hummed with satisfaction, “(c) Manyifik (Magnificent).”

You nod, then turn to walk away.

“Remy.” You hear him call to you.

“Pardon?” You say as you turn back to him.

“The name’s Remy LaBeau.” He reiterated cooly after taking a sip from his glass.

He averted his eyes to you, awaiting your name. You grin back.

“Y/F/N.”

“(c) Kontan rankontre ou, Y/F/N (Pleased to meet you).”

You feel your face go red as you laugh nervously.

“Same.” You managed to say before scurrying to the other end of the bar to wait on other customers.

♠️♥️♣️♦️

Remy sat quietly in his spot at the bar the entire evening, only ever looking up from his deck of Mavericks to catch a glance of you as you pass him. The crowd started to thin out as last call was announced.

“One for the road, Remy?”

He beamed at you, “Oui, cheri. If you join me for one.”

You smile coyly, “I gotta close up, chief. How about this; I’ll bring you another Sazerac on the house, and I’ll take a rain check?”

You see the magenta glimmer in his eyes again.

“I like the soun’ of dat, cheri.”

You smile and nod then turn to the counter behind you to prepare his drink. You set it in front of him as he placed a $100 in front of you.

“You only had two. That’s too much.”

“(c) Pran li (Take it). For your generosity an’ da company.” Remy insisted.

You beam at him, “(c) Ou twò janti (You’re too kind).”

He stood up from his stool, and fixed his collar on his leather trench.

“Until next time, mon cher.” He said smiling while standing tall opposite you.

“Orevwa, Remy. I’ll see you around.” You reply sweetly as you feel your cheeks heat up again.

“(c) Mwen pwomèt ou pral (I promise you will).” He purred in his heavy honeyed Cajun accent.

He bowed, then turned on his heel to exit the bar. You released a deep exhale as if you hadn’t taken a breath since having met him that night.

♠️♥️♣️♦️

*I know this was a short one and I plan on a chapter 2. I’m just dipping my toe in the water here to see what feedback I get* 🥰

#marvel cinematic universe#marvel#gambit#remy lebeau#channing tatum#x men#cajun#ragin cajun#diablo#diablo blanco#deadpool and wolverine#nola#french quarter#bourbon street#black penny#voodoo#mardi gras#mutants#gambit x reader#gambit x you#gambit x y/n#remy lebeau x reader#remy lebeau x you#remy lebeau x y/n#louisiana creole#haitian creole#french#maximum effort#sazerac

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Film & TV I Think About A Lot » Eve's Bayou (1997) dir. Kasi Lemmons

"When I was your age, before I ever did the counseling, I could look at people, complete strangers, and see their whole lives so clear. But when I looked at each of my husbands, I never saw a thing. That's how it always is. Blind to my own life."

#eves bayou#eve's bayou#Kasi Lemmons#jurnee smollett#meagan good#lynn whitfield#diahann carroll#debbi morgan#film gifs#movie gifs#1997#film#black films#black women#louisiana#gifs#mygifs#cgedits#cftv#starting to get the hang of larger gifs#This film is gorgeous and has so many great lines#really influential on my storytelling style along with daughters of the dust#witches#widtcraft#voodoo#vodou#black

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Representation of Haitian Voodoo in comics. Integrating its rich mythology and its deities.

Art by: vodou.renaissance

#witches#witchcraft#witch#baby witch#witch community#magick#pop magick#pop culture magic#pop culture magick#louisiana hoodoo#hoodoo witch#new orleans hoodoo#hoodoo#folk magic#african folk magick#folklore#creole voodoo#new orleans voodoo#louisiana voodoo#voodoo#comics#comic#comic art#pop culture

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was watching In Our Mother’s Garden (2021) on Netflix last night and was surprised to see Dr. Zauditu-Selassie cook for and feed the ancestors at around the 1 hour mark in what fits Dr. Brenda Marie Osbey’s description of an authentic voodoo tradition. Dr. Zauditu-Selassie explains her family of creole descent was matrilineal and “believed in Hoodoo,” though she is now a priest of Obatala in the Lucumi tradition. I understand many of the African diasporic religions share commonalities, though distinct, such as feeding the ancestors, but this is probably the closest to an authentic and respectful depiction that exists out there.

I’ve linked a list of additional resources on Lousiana Voodoo and Hoodoo here.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gran Bwa. Vodou Spirit Of The Forest.

This lwa of one of my favorite I'm going to speak a little about him.

Gran Bwa is a big part of all forms of voodoo. He is the lwa of the forest, he's a healer who has power of the sacred forest. He is a powerful lwa. He may or may not be of Congolese origin originally, but some believe have originally been a Taino spirit incorporated into the Vodou pantheon.

What Nation Is Gran Bwa From? He is from the Rada Nation, Not Petro like the internet says. He is a patron of initiations. Gran Bwa is considered the Tree of Life that connects the celestial realms with those of the living and the dead. I won't say he is the ruler of the forest but it's protector and you can find him their or at any tree if needed.

Gran Bwa can help you make baths and washes,wanga bottles, packet etc. He is a great healer who can bring luck to you and he would come to your defence. He can break strong black magic and curses and cleanse negativity. He can help you connect to your ancestors and your spiritual home in Vodou.

Gran Bwa is the Shade tree, Giving tree, Medicine tree, and the Hanging tree all at the same time. Tell him what you require and he'll help you.

If you follow the Catholicism path he is synchronize with Saint Sebastian.

St. Sebastian photo.

In other African religion like Puerto Rican Sanse, he is St. Sebastian or St. Jude.

Even thou voodoo spirit aren't saints he knows who your truly speaking too when you call apon him.

ANIMALS: He protects all forest animals.

COLOURS: Green or Red.

DAY: Saturday.

ALTAR: You can hang offerings from a any tree branch or lay them at the foot of the tree. Your altar is fine also.

Where To Find Him: You can find him in any forest area. Are if you have a place with a large old tree or a sacred tree (Eggun Tree) you'll find him their.

OFFERINGS: He likes green leaves and herbs, even braches if it's picked from a forest. Tobacco, Rum.

#Gran Bwa#vodou lwa#Voodoo lwa#louisiana voodoo#haitian vodou#vodou deities#vodou loa#google search#like and/or reblog!#follow my blog#Healing spirit#african diasporic#african spirituality#Spirit energies#ask me a question#ask me anything#message me

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haitian Immigration : Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Many Haitians moved to Louisiana during and after the Haitian Revolution, which began in 1791 and lasted for 13 years:

The long, interwoven history of Haiti and the United States began on the last day of 1698, when French explorer Sieur d'Iberville set out from the island of Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti) to establish a settlement at Biloxi, on the Gulf Coast of France's Louisiana possession.

For most of the eighteenth century, however, only a few African migrants settled there. But between the 1790s and 1809, large numbers of Haitians of African descent migrated to Louisiana. By 1791 the Haitian Revolution was under way. It would continue for thirteen years, result in the independence of the first African republic in the Western Hemisphere, and reverberate throughout the Atlantic world. Its impact would be particularly felt in Louisiana, the destination of thousands of refugees from the island's turmoil. Their activism had profound repercussions on the politics, the culture, the religion, and the racial climate of the state.

From Saint Domingue to Louisiana

Louisiana and her Caribbean parent colony developed intimate links during the eighteenth century, centered on maritime trade, the exchange of capital and information, and the migration of colonists. From such beginnings, Haitians exerted a profound influence on Louisiana's politics, people, religion, and culture. The colony's officials, responding to anti-slavery plots and uprisings on the island, banned the entry of enslaved Saint Domingans in 1763. Their rebellious actions would continue to impact upon Louisiana's slave trade and immigration policies throughout the age of the American and French revolutions.

These two democratic struggles struck fear in the hearts of the Spaniards, who governed Louisiana from 1763 to 1800. They suppressed what they saw as seditious activities and banned subversive materials in a futile attempt to isolate their colony from the spread of democratic revolution. In May 1790 a royal decree prohibited the entry of blacks - enslaved and free - from the French West Indies. A year later, the Haitian Revolution started.

The revolution in Saint Domingue unleashed a massive multiracial exodus: the French fled with the bondspeople they managed to keep; so did numerous free people of color, some of whom were slaveholders themselves. In addition, in 1793, a catastrophic fire destroyed two-thirds of the principal city, Cap Français (present-day Cap Haïtien), and nearly ten thousand people left the island for good. In the ensuing decades of revolution, foreign invasion, and civil war, thousands more fled the turmoil. Many moved eastward to Santo Domingo (present-day Dominican Republic) or to nearby Caribbean islands. Large numbers of immigrants, black and white, found shelter in North America, notably in New York, Baltimore (fifty-three ships landed there in July 1793), Philadelphia, Norfolk, Charleston, and Savannah, as well as in Spanish Florida. Nowhere on the continent, however, did the refugee movement exert as profound an influence as in southern Louisiana.

Between 1791 and 1803, thirteen hundred refugees arrived in New Orleans. The authorities were concerned that some had come with "seditious" ideas. In the spring of 1795, Pointe Coupée was the scene of an attempted insurrection during which planters' homes were burned down. Following the incident, a free émigré from Saint Domingue, Louis Benoit, accused of being "very imbued with the revolutionary maxims which have devastated the said colony" was banished. The failed uprising caused planter Joseph Pontalba to take "heed of the dreadful calamities of Saint Domingue, and of the germ of revolt only too widespread among our slaves." Continued unrest in Pointe Coupée and on the German Coast contributed to a decision to shut down the entire slave trade in the spring of 1796.

In 1800 Louisiana officials debated reopening it, but they agreed that Saint Domingue blacks would be barred from entry. They also noted the presence of black and white insurgents from the French West Indies who were "propagating dangerous doctrines among our Negroes." Their slaves seemed more "insolent," "ungovernable," and "insubordinate" than they had just five years before.

That same year, Spain ceded Louisiana back to France, and planters continued to live in fear of revolts. After future emperor Napoleon Bonaparte sold the colony to the United States in 1803 because his disastrous expedition against Saint Domingue had stretched his finances and military too thin, events in the island loomed even larger in Louisiana.

The Black Republic and Louisiana

In January 1804, an event of enormous importance shook the world of the enslaved and their owners. The black revolutionaries, who had been fighting for a dozen years, crushed Napoleon's 60,000 men-army - which counted mercenaries from all over Europe - and proclaimed the nation of Haiti (the original Indian name of the island), the second independent nation in the Western Hemisphere and the world's first black-led republic. The impact of this victory of unarmed slaves against their oppressors was felt throughout the slave societies. In Louisiana, it sparked a confrontation at Bayou La Fourche. According to white residents, twelve Haitians from a passing vessel threatened them "with many insulting and menacing expressions" and "spoke of eating human flesh and in general demonstrated great Savageness of character, boasting of what they had seen and done in the horrors of St. Domingo [Saint Domingue]."

The slaveholders' anxieties increased and inspired a new series of statutes to isolate Louisiana from the spread of revolution. The ban on West Indian bondspeople continued and in June 1806 the territorial legislature barred the entry from the French Caribbean of free black males over the age of fourteen. A year later, the prohibition was extended: all free black adult males were excluded, regardless of their nationality. Severe punishments, including enslavement, accompanied the new laws.

However, American efforts to prevent the entry of Haitian immigrants proved even less successful than those of the French and the Spanish. Indeed, the number of immigrants skyrocketed between May 1809 and June 1810, when Spanish authorities expelled thousands of Haitians from Cuba, where they had taken refuge several years earlier. In the wake of this action, New Orleans' Creole whites overcame their chronic fears and clamored for the entry of the white refugees and their slaves. Their objective was to strengthen Louisiana's declining French-speaking community and offset Anglo-American influence. The white Creoles felt that the increasing American presence posed a greater threat to their interests than a potentially dangerous class of enslaved West Indians.

American officials bowed to their pressure and reluctantly allowed white émigrés to enter the city with their slaves. At the same time, however, they attempted to halt the migration of free black refugees. Louisiana's territorial governor, William C. C. Claiborne, firmly enforced the ban on free black males. He advised the American consul in Santiago de Cuba:

Males above the age of fifteen, have . . . been ordered to depart. - I must request you, Sir, to make known this circumstance and also to discourage free people of colour of every description from emigrating to the Territory of Orleans; We have already a much greater proportion of that population than comports with the general Interest.

Claiborne and other officials labored in vain; the population of Afro-Creoles grew larger and even more assertive after the entry of the Haitian émigrés from Cuba, nearly 90 percent of whom settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites, 3,102 free persons of African descent, and 3,226 enslaved refugees to the city, doubling its population. Sixty-three percent of Crescent City inhabitants were now black. Among the nation's major cities only Charleston, with a 53 percent black majority, was comparable.

The multiracial refugee population settled in the French Quarter and the neighboring Faubourg Marigny district, and revitalized Creole culture and institutions. New Orleans acquired a reputation as the nation's "Creole Capital."

The rapid growth of the city's population of free persons of color strengthened the "three-caste" society - white, mixed, black - that had developed during the years of French and Spanish rule. This was quite different from the racial order prevailing in the rest of the United States, where attempts were made to confine all persons of African descent to a separate and inferior racial caste - a situation brought about by political reality in the South that promoted white unity across class lines and the immersion of all blacks into a single and subservient social caste.

In Louisiana, as lawmakers moved to suppress manumission and undermine the free black presence, the refugees dealt a serious blow to their efforts. In 1810 the city's French-speaking Creoles of African descent, reinforced by thousands of Haitian refugees, formed the basis for the emergence of one of the most advanced black communities in North America.

Soldiers, Rebels, and Pirates

Many Haitian black males eluded immigration authorities by slipping into the territory through Barataria, a coastal settlement just west of the Mississippi River. Some became allies of the notorious pirates Jean and Pierre Lafitte, white refugees of the Haitian Revolution. Surrounded by marshland and a maze of waterways, Barataria was an effective staging area for attacks on Gulf shipping. The interracial band of adventurers dominated the settlement's thriving black-market economy.

But pirates and smugglers did not make up the whole of Barataria's fugitive residents. Some two hundred free black veterans of the Haitian Revolution, including Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Savary, a former French republican officer, were among them. In 1799 seven hundred soldiers, opposed to Toussaint L'Ouverture fled to Cuba and later migrated to Louisiana. By 1810 this movement of Haitian soldiers from Cuba had created a black military presence in Louisiana that seriously worried Governor Claiborne. He anxiously requested reinforcements. The number of free black men "in and near New Orleans, capable of carrying arms," he wrote, "cannot be less than eight hundred."

Colonel Savary and other republican veterans of the Haitian Revolution remained committed to the French revolution's ideals of liberté, egalité, fraternité (freedom, equality, fraternity.) They regrouped to aid insurgents attempting to establish independent republics in Latin America. In November 1813 Savary offered to send five hundred Haitian soldiers to fight with Mexican revolutionaries. When their effort to establish a Mexican government in Texas failed, Savary and his men returned to New Orleans. Within the year, however, the colonel and other Haitian veterans would be rallying against the forces of the British crown.

As British forces threatened to invade New Orleans in 1814, American authorities sought to win the loyalty of battle-hardened black soldiers like Colonel Savary. They were also well aware of the prominent role that free men had played in slave rebellions. With the English approaching, pacifying them would be strategically sound.

General Andrew Jackson arrived in New Orleans in December 1814 and immediately mustered 350 native-born black veterans of the Spanish militia into the United States Army. Colonel Savary raised a second black unit of 250 of Haiti's refugee soldiers. Jackson recognized Savary's considerable influence and knew of his reputation as "a man of great courage." On Jackson's orders, Savary became the first African-American soldier to achieve the rank of second major.

The Haitians in Barataria also fought in the battle of New Orleans. In September 1814 federal troops invaded their community and dispersed the Lafittes and their followers. Hundreds of refugees poured into the city. Andrew Jackson offered them pardons in return for their support in defending the city. After the victory, he commended the two battalions of six hundred African-American and Haitian soldiers whose presence in a force of three thousand men had proved decisive. He praised the "privateers and gentlemen" of Barataria who "through their loyalty and courage, redeemed [their] pledge . . . to defend the country."

Jackson observed that Captain Savary "continued to merit the highest praise." In the last significant skirmish of the battle, Savary and a detachment of his men volunteered to clear the field of a detail of British sharpshooters. Though Savary's force suffered heavy casualties, the mission was carried out successfully.

Within weeks of the victory, however, Jackson yielded to white pressure to remove the men from New Orleans to a remote site in the marshland east of the city to repair fortifications. Savary relayed a message to the general that his men "would always be willing to sacrifice their lives in defense of their country as had been demonstrated but preferred death to the performance of the work of laborers." Jackson, though not pleased, refrained from taking any action against the troops. In February, the general even lent his support to Savary's renewed efforts to rejoin republican insurgents in Mexico.

Afro-Creoles and Americans

In colonial Louisiana and in colonial Haiti, military service had functioned as a crucial means of advancement for both free and enslaved blacks. After the battle of New Orleans, however, support for the black militia declined among free people of color. The disrespect shown to the soldiers who fought so valiantly, along with their disappointment at not receiving some measure of political recognition, contributed to their disillusionment.

Afro-Creoles' anger mounted as Louisiana's white lawmakers embarked upon an unprecedented and sustained attack upon their rights by formulating one of the harshest slave codes in the American South. In 1830 the legislature reaffirmed the 1807 ban on the entry of "free negroes and mulattoes" and required slaveholders to ensure the removal of freed people within thirty days of their emancipation. In Louisiana, as elsewhere in the South, segregation, anti-miscegenation laws, and the legal ostracism of racially mixed children signified the imposition of a two-category pattern of racial classification that relegated all persons of African ancestry to a degraded status.

Reduced to a debased condition, deprived of citizenship, denied free movement, and threatened with violence, Afro-Creoles, both native-born and immigrant, developed an intensely antagonistic relationship with the new regime. Under the United States government, black Louisianians had anticipated an end to slavery and racial oppression and had looked for the fulfillment of the democratic ideals embodied in the founding principles of the new American republic. But contrary to their expectations, the process of Americanization negated the promise of the revolutionary era. Instead of moving toward freedom and equality, the new government promoted the evolution of an increasingly harsh system of chattel slavery.

From Revolution to Romanticism

Following the example of intellectuals in France and Haiti, Afro-Creole activists in Louisiana - led by Haitian émigrés, their children, and French-speaking native Louisianians - had been nurturing their republican heritage. As political expression was stifled, they poured their energies into a new vehicle of revolutionary ideas, the Romantic literary movement.

New Orleans' highly politicized black intelligentsia thereby tapped into the Atlantic world's ongoing current of political radicalism, protesting injustice in their literary work. Their principal forum was La Société des Artisans. Founded by free black artisans and veterans of the War of 1812, the organization provided local Creole writers the opportunity to exchange ideas and present their numerous artistic works in a friendly setting.

Among these young writers was Victor Séjour. His father, a Haitian émigré, was a veteran of the War of 1812 and a prosperous dry-goods merchant. The young Séjour had been educated at New Orleans' prestigious black school Académie Sainte-Barbe, under the tutelage of Michel Séligny, the most productive Afro-Creole short-story writer. Séjour's audience at La Société proclaimed him a prodigy, and his father, determined to see his son fulfill his artistic potential and anxious for Victor to escape the burden of racial prejudice in Louisiana, sent him to France to complete his education. In Paris, the youth quickly came under the influence of another writer of African-Haitian descent, renowned novelist Alexandre Dumas, author of The Three Musketeers (1844), The Count of Monte Cristo (1844-45), and many other celebrated works.

Séjour made a dramatic debut on the literary scene with the publication, in March 1837, of an impassioned attack on slavery, "Le Mulâtre" (The Mulatto), the first short story by an African-American writer to be published in France.

Following the publication of "Le Mulâtre," Séjour embarked on a remarkably productive artistic career. When he was only twenty-six years old, the famed Théâtre Français produced his first drama; it would be followed by two dozen more. In one season, French theaters produced three of his works simultaneously, and Emperor Napoleon III attended opening nights of two of them.

Ironically, Séjour's first story, though it may have circulated privately within the black community, was never published in New Orleans. It fell within the parameters of an 1830 Louisiana law prohibiting reading matter "having a tendency to produce discontent among the free coloured population . . . or to excite insubordination among the slaves." Violators faced either a penalty of three to twenty-one years at hard labor or death, at the judge's discretion.

Despite such restrictions, the city's free people of color managed to fashion a vibrant literary movement, dominated by Haitian refugees and their descendants. The influence of the French Romantic movement among New Orleans' black intellectuals became more evident in 1843 with the publication of a short-lived, interracial literary journal L'Album littéraire: Journal des jeunes gens, amateurs de littérature (The Literary Album: A Journal of Young Men, Lovers of Literature). Its most prominent black founder was Armand Lanusse, of Haitian ancestry and one of the city's leading Romantic artists. Lanusse and his fellow writers, both émigré and native-born, ignored the 1830 literary censorship law and, like their fellow Romantics in France and Haiti, used their literary skills to challenge existing social evils.

In a series of introductory essays,the anonymous contributors to L'Album deplored "the sad and awful condition of Louisiana society," where the spectacle of rampant greed, unrelieved poverty, and institutionalized injustice "grips our hearts with deep sorrow, showering grief over all our thoughts, filling the soul with terror and despair."

Within a year of its debut, L'Album disappeared from the literary scene after critics attacked the journal for advocating revolt. Lanusse then edited a collection of poems by Creoles of color in 1845; Les Cenelles: Choix de poésies indigènes was the first anthology of literature by African Americans in the United States. Les Cenelles was much more subdued in tone than its predecessor. Still, Lanusse in his preface emphasized the value of education as "a shield against the spiteful and calamitous arrows shot at us." He and his colleagues considered their art form a springboard to social and political reform.

The Haitian Influence on Religion

In 1847 Lanusse and his friends helped to assure the survival of a small Catholic religious order dedicated to charitable work among the city's enslaved people and free black indigents. The congregation of the Sisters of the Holy Family was founded in 1842 by Henriette Delille, yet another prominent Afro-Creole of Haitian ancestry. As Delille's sisterhood struggled to maintain their community during the 1840s, a coalition of Afro-Creole writers, artisans, and philanthropists obtained corporate status and funding for the religious society.

When Delille took her formal religious vows in 1852, she headed Louisiana's first Catholic religious order of black women and the nation's second African-American community of Catholic nuns. Bearing striking testimony to the enormous impact of the Haitian diaspora, the first Catholic community of African-American nuns, the Oblate Sisters of Providence, founded in 1829 in Baltimore, originated in the Haitian refugee movement.

In 1848, Armand Lanusse and other Romantic writers took concrete measures to promote reform by establishing La Société Catholique pour l'Instruction des Orphelins dans l'Indigence (Catholic Society for the Instruction of Indigent Orphans). Through their organization, black activists executed the terms of a bequest by Madame Justine Firmin Couvent, a native of Guinea and a former slave, to establish a school in the Faubourg Marigny for the district's destitute orphans of color. Appalled by the indigence and illiteracy of the children, Couvent donated land and several buildings for an educational facility of which Lanusse became the first principal.

While Lanusse pursued his reform agenda within the existing institutional framework, another contributor to the volume, Nelson Desbrosses, followed a nontraditional path to empowerment and change. He traveled to Haiti before the Civil War, studied with a leading practitioner of Vodou, and returned to New Orleans with a reputation as a successful healer and spirit medium. Desbrosses undoubtedly recognized Vodou's historical significance in Haiti's independence struggle. During the revolution, the religion served as a medium for political organization as well as an ideological force for change. On the battlefield, Vodou's spiritual power proved decisive in reinforcing the determination of revolutionaries in their struggle for freedom. In the North Province, houngans (Vodou priests) sustained the revolt by mobilizing as many as forty thousand enslaved people.

Vodou thrived in New Orleans until the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, when President Thomas Jefferson and other political leaders sought to undermine Creole predominance by Americanizing the culture of southern Louisiana. The post-1809 influx of Haitian refugees, however, slowed the Americanization process and assured the vitality of New Orleans' Creole culture for another twenty-five years. Immigrant believers in Vodou infused the religion's Louisiana variant with Afro-Caribbean elements of belief and ritual.

In the relatively tolerant religious milieu of antebellum New Orleans, Haitian immigrants joined with Creole slaves, free blacks, and even whites to assure the religion's ascendancy. Through Vodou, practiced in secrecy, Afro-Creoles preserved the memory of their African past and experienced psychological release by way of a religion that served as one of the few areas of totally autonomous black activity.

In transcending ethnic, class, and gender distinctions, Vodou helped to sustain a liberal Latin European religious ethic that recognized the spiritual equality of all persons. Vodou's interracial appeal and egalitarian spirit, reinvigorated by Haitian immigrants, offered a dramatic alternative to the Anglo-American racial order.

Beginning in the 1860s, Vodou assemblies were systematically suppressed, but the famed "Vodou Queen" Marie Laveau continued to exert great influence over her interracial following. In 1874 some twelve thousand spectators swarmed to the shores of Lake Pontchartrain to catch a glimpse of Laveau performing her legendary rites. By that time Laveau and other Afro-Creole Vodouists had fashioned some of the nation's most lasting folkloric traditions, as well as a religion of resistance that endures to the present moment.

The Civil War

Federal forces occupied New Orleans in 1862, and black Creoles volunteered their services to the Union army. The newspaper L'Union - whose chief founders, Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez and his brother, Jean-Baptiste, were of Haitian ancestry - announced its agenda in the premier issue. The editors condemned slavery, blasted the Confederacy, and expressed solidarity with Haiti's revolutionary republicans.

An 1862 editorial written by a newly enlisted Union officer, Afro-Creole Romantic writer Henry Louis Rey, urged free men of color to join the U.S. Army and take up "the cause of the rights of man." Rey invoked the names of Jean-Baptiste Chavannes and Vincent Ogé. Their ill-fated 1790 revolt had paved the way for the Haitian Revolution:

CHAVANNE [sic] and OGÉ did not wait to be aroused and to be made ashamed; they hurried unto death; they became martyrs here on earth and received on high the reward due to generous hearts...hasten all; our blood only is demanded; who will hesitate?

The editors of L'Union described Rey and the Afro-Creole troops as the "worthy grandsons of the noble [Col. Joseph] Savary." The paper insisted that military service entitled them to the political equality that had been denied their ancestors who fought valiantly in the American Revolution and the War of 1812. Furthermore, its editors warned, the men had resolved to "protest against all politics which would tend to expatriate them."

When federal officials undermined their suffrage campaign, Afro-Creole leaders took their case to the highest level. In 1864 L'Union cofounder Jean-Baptiste Roudanez and E. Arnold Bertonneau, a former officer in the Union army, met with President Abraham Lincoln; they urged him to extend voting rights to all Louisianians of African descent.

In L'Union, and its successor, La Tribune, the Roudanez brothers and their allies foresaw the complete assimilation of African Americans into the nation's political and social life. During Reconstruction they called on the federal government to divide confiscated plantations into ten-acre plots, to be distributed to displaced black families. They insisted that the formely enslaved were "entitled by a paramount right to the possession of the soil they have so long cultivated."

The aggressive stance and republican idealism of La Tribune prompted the authors of Louisiana's 1868 state constitution to envision a social and political revolution. The new charter required state officials to swear that they recognized the civil and political equality of all men. Alone among Reconstruction constitutions, Louisiana explicitly required equal access to public accommodations and forbade segregation in public schools.

The Consequences of the Haitian Migration

After Reconstruction collapsed in 1877, Creole activists fought the restoration of white rule. In 1890 Rodolphe L. Desdunes, a Creole New Orleanian of Haitian descent, joined with other prominent rights advocates to challenge state-imposed segregation. Their legal battle culminated in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision. Though the nation's highest tribunal upheld the "separate but equal" doctrine, the decision included a powerful dissent that would be used to rescue the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments in later Supreme Court decisions. The descendants of Haitian immigrants would play key roles in civil rights campaigns of the twentieth century.

Haitians exerted an enormous influence on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Louisiana. Their sustained resistance to Saint Domingue's regime of bondage forced repeated changes in French, Spanish, and American immigration policies as frightened white officials attempted to isolate Louisiana from the spread of black revolt.

The massive 1809 influx of Haitian refugees ensured the survival of a wealth of West African cultural transmissions, as well as a Latin European racial order that enhanced the social and economic mobility of both free and enslaved blacks. In early-nineteenth-century New Orleans, the immigrants and their descendants infused the city's music, cuisine, religious life, speech patterns, and architecture with their own cultural traditions. Reminders of their Creole influence abound in the French Quarter, the Faubourg Marigny, the Faubourg Tremé, and other city neighborhoods.

The refugee population also reinforced a brand of revolutionary republicanism that impacted American race relations for decades. With an unflagging commitment to the democratic ideals of the revolutionary era, Haitian immigrants and their descendants appeared at the head of virtually every New Orleans civil rights campaign. Their leadership role in the struggle for racial justice offers dramatic evidence of the scope of their influence on Louisiana's history. From Colonel Joseph Savary's militant republicanism to Rodolphe Desdunes's unrelenting attacks on state-enforced segregation, Haitian émigrés and their descendants demanded that the nation fulfill the promise of its founding principles.

In his 1911 book Our People and Our History, Rodolphe Desdunes described Armand Lanusse's anthology, Les Cenelles, as a "triumph of the human spirit over the forces of obscurantism in Louisiana that denied the education and intellectual advancement of the colored masses." African Americans in Louisiana triumphed over these forces in their distinguished history of military service, their embrace of artistic and scholarly pursuits, their campaign for humanitarian reforms, and their Civil War vision of a reconstructed nation of racial equality. Their Haitian heritage was central to those victories.

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#brown skin#afrakans#haitian#haiti#vodun#voodoo#voodou#afrakan spirituality#african culture#haitian heritage#louisiana#migration#migrant#migrants

16 notes

·

View notes